ABSTRACT

Background

The volume of literature about serious gaming in dental education has increased, however, none of the previous studies have developed a serious game for closing the gap between preclinical and clinical training.

Objective

Virtual Dental Clinic (VDC) is a serious game that was created to help develop clinical reasoning skills in dental students. This study aimed to evaluate VDC as an educational tool and its effectiveness on clinical skill and knowledge gain among clerkship dental students.

Methods

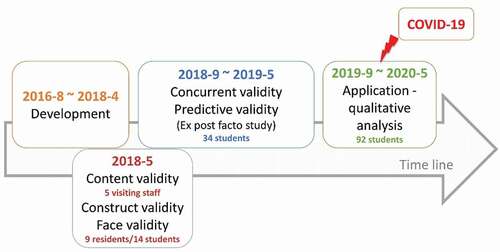

The following three stages of VDC design and testing were addressed from 2016 to 2020: development, validation, and application. The VDC was developed using Unity game engine. In the validation stage, the content validity was reviewed by five visiting staff; construct validity and face validity were examined by 9 postgraduate-year dentists and 14 clerkship dental students. Concurrent validity and predictive validity were examined by 34 fifth-year dental students during their clerkship from September, 2018 to May, 2019, the associations between VDC experiences, clerkship performance, and the score on a national qualification test were explored. In the application stage, the VDC was set up as a self-learning tool in the Family Dentistry Department from August, 2019, quantitative and qualitative analyses were conducted using the 92 clerkship students’ feedback.

Results

The VDC showed good validity and a high potential for education in practice. Students who have used VDC received significantly higher scores on qualification test (p = 0.029); the VDC experiences significantly predicted higher performance score on periodontics (p = 0.037) and endodontics (p = 0.040). After the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, significantly higher proportion of students confirmed the value of VDC as an assistant tool for learning clinical reasoning (p = 0.019).

Conclusions

The VDC as an educational tool, and the effectiveness on clinical reasoning skills and knowledge gain among clerkship dental students has been validated and confirmed in this study.

Introduction

Dental education is usually divided into two parts (preclinical and clinical). Preclinical students predominantly study basic science in lectures and practical work in the simulation laboratory courses. In the clinical part, students work with actual patients under the supervision of visiting staff [Citation1]. Transition points in dental education can be abrupt, stressful, and disorienting for learners. The first transition point for students, after dental school matriculation, is the move from the preclinical curriculum to clinical clerkships. Closing the gap between preclinical and clinical training is essential [Citation2]. Preclinical dentistry training is the preparatory phase that includes integrated basic science knowledge and skills in a decision-making context. This is expected to enable future clinicians to independently manage diverse clinical scenarios and deliver adequate high-quality care to patients [Citation3,Citation4]. Accordingly, training programmes should provide students a safe environment that is conducive for learning anywhere and anytime.

Serious games are technology-enhanced simulation games developed for a purpose other than entertainment, such as teaching a specific knowledge or skill [Citation5]. Unlike traditional approaches, they are often considered to provide a more interactive learning environment, a motivational approach to learning, and safe training for patients and students. They also allow students to reconsider their strategies following failure until they complete the game [Citation6,Citation7]. Positive attitude and learner satisfaction have been found in medical, health professional, and dental students using these games as a learning tool [Citation8,Citation9]. However, the application of serious games in dental education remains underutilised and under-researched [Citation9].

Previous studies related to simulation in dental education mainly focused on the simulated training on psychomotor skills [Citation10]. Serious game for improving the transition of declarative knowledge to procedural knowledge is a new attempt. Two studies [Citation11,Citation12] used randomised control trials to make comparisons between serious games (test group) and traditional learning style (control group) in dental education. Amer [Citation11] reported on using a serious game for teaching dentine bonding and basic knowledge for composite resin filling in operative dentistry. Hannig et al. [Citation12] assessed the effectiveness of Skills-O-Mat, a serious game for training in mixing alginate for dental impression, which is a mandatory skill for dental care. Overall, two key studies [Citation11,Citation12] in our knowledge, suggest that serious games are potentially effective learning tools for dental education, and the students were satisfied with the game-based learning approach. Both studies [Citation11,Citation12] were performed on first-year or second-year dental students to acquire basic science and skills. Games Research Applied to Public Health with Innovative Collaboration-II (GRAPHIC-II) [Citation13] is a serious game for dental public health where students can practice critical thinking and decision-making skills regarding health promotion in a safe environment.

In Taiwan, treatment planning is one of the most important nonoperational skills for dental students [Citation14]. However, to the best of our knowledge, previous studies have not examined the effectiveness of a serious game in helping students with treatment planning and familiarising them with the procedures of various treatments. Virtual Dental Clinic (VDC) is a serious game developed for training clinical reasoning in dentistry. Clinical reasoning is a vital competency that enables students to apply the theory they learned to actual clinical situations. This study aimed to evaluate the validity and effectiveness of VDC as an educational tool for clinical skills and knowledge gain among clerkship dental students.

Materials and methods

The following three stages of VDC design and testing were addressed. The sequence involved development, validation, and application (). In the development stage, from August 2016 to April 2018, the prototype of a dental simulation clinic software was prepared, designed, and developed. In the validation stage, during May 2018, 5 visiting staff were recruited to examine the content validity of each theme, 9 residents and 14 students were recruited to examine the responses of the experts and novices (construct validity and face validity); from September 2018 to May 2019, a quasi-experimental ex post facto study was conducted on a convenience sample of 34 fifth-year students during their clerkship training, the concurrent validity and predictive validity were obtained by analysing their academic achievements. Finally, in the application stage, the VDC was introduced to the new batch of fifth-year students as a self-learning tool during their clerkship training, from September 2019 to May 2020, and a qualitative analysis was conducted. The study design followed the suggested framework for game development [Citation15] and criteria for the validation process [Citation16–18].

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (Letter No. KMUHIRB-SV(II)-20170009 and KMUHIRB-SV(II)-20210020). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Description of the serious game and its development

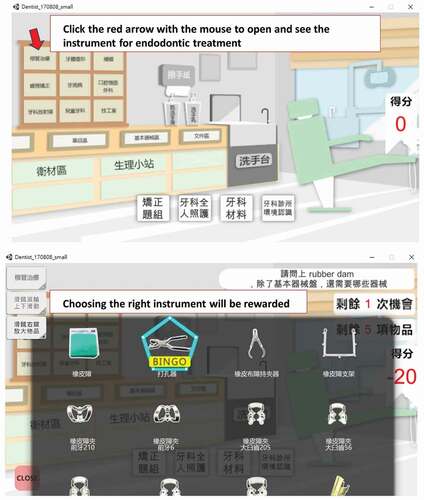

The concept of this dental simulation clinic software was originally designed by Ju-Hui Wu (one of the authors of this paper). This gaming software is developed using the Unity game engine and built on a stand-alone game running on the Windows platform. The learning objective is to improve the cognitive knowledge of dental clerks regarding various treatment procedures, such as tooth composite resin filling, root canal therapy, and cement mixing methods, and also enhance the understanding of materials and equipment in the clinic, to know the timing of their use and operation methods. The game scene is a virtual dental clinic, including the dental equipment, materials, documents, and medicines built in the game software (). The player is required to click the red arrow with the mouse to open and see the instrument for endodontic treatment. Choosing the right instrument is rewarded. The task is divided into six themes: introduction of dental clinic environment, interpretation of X-ray images, dental materials, orthodontics instrument, patient care in operative dentistry, and endodontic treatment. Each theme is subdivided into 2–12 items, with 42 items in total. During the game, a failure message appears when the answer is wrong, and an applause when the answer is correct. The game provides immediate feedback to the player and using a formative assessment method. The player has two chances to answer a question.

Validation of the serious game

Content validity

Five visiting staff with at least three years of experience in general dentistry were invited to review the items of each theme. The appropriateness of each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = not relevant to 5 = highly relevant). Next, for each item, the item-level content validity index (I-CVI) was calculated based on the number of experts who rated it as either 4 or 5 (thus, dichotomising the ordinal scale into relevant and not relevant) divided by the total number of experts. An item that was rated as relevant by four out of the five experts would have an I-CVI of 0.80 [Citation19,Citation20]. They suggested that six items needed modification. After the modification, all items showed an acceptable item-level content validity index (I-CVI ranged from 0.8 to 1) (see Appendix).

There are two methods to calculate the scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) – using the universal agreement calculation methods (S-CVI/UA) and estimating by averaging calculation methods (S-CVI/Ave) [Citation19,Citation20]. In this study, both ways of calculating the S-CVI were found to be acceptable (S-CVI/UA = 0.81, S-CVI/Ave = 0.96) (see Appendix). The S-CVI/Ave of each theme is reported according to the recommendations of Polit et al. [Citation20].

Construct validity and face validity

A total of 9 postgraduate-year (PGY) dentists and 14 clerkship dental students who were training in Family Dentistry Department at that time were invited to play the VDC, and their answers in the first round for each item of all themes were recorded. We then compared the rates of correct answers between experts and novices.

After finishing the game, they were asked to fill a questionnaire, which included their impressions and attitudes toward VDC’s educational values and game quality. The content of the questionnaire was modified from Wang et al. [Citation21], including eight items for educational values and seven items for game quality, measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.908 for educational value and 0.905 for game quality showed good internal consistency.

Concurrent validity and predictive validity

A quasi-experimental ex post facto study was conducted. A total of 34 fifth-year dental students volunteered to participate in this study before they began the clerkship from September 2018 to May 2019. The participants were given the VDC software, and informed that they have the right decide if they wished to use the VDC as a self-learning tool during their clerkship or not. Those who had used VDC were categorised as experimental group and those who had not were categorised as the control group. Information pertaining to their video game-playing habits and learning strategies were collected.

In their clerkship training, they were required to complete 84 sessions, involving 336 hours of training in the department of dentistry at a medical centre. Before they finished the training, all the fifth-year dental students were required to attend a national qualification test hosted by the Association for Dental Sciences of the Republic of China (ADS-ROC). This test which was divided into two parts – the operational test and the computer-based test for non-operational skills – aimed to evaluate each student’s preparedness to be an intern. The participants’ computer-based test scores were used to evaluate the VDC’s concurrent validity. The computer-based test comprised four clinical cases and aimed to exam the abilities related to clinical reasoning, treatment planning, and instrument selection. After finishing the clerkship training, the participants’ academic achievements were evaluated by the tutors of each specialty. We used the performance scores to evaluate the predictive validity of VDC ().

Practical application

From August, 2019, the Family Dentistry Department set up the self-learning tools including the textbooks, simulation model, and VDC for students to create a self-learning environment. There were 92 fifth-year dental students who volunteered to use these self-learning tools from September, 2019 to May, 2020 during their clerkship training. Although COVID-19 occurred during this period, Taiwan implemented an effective epidemic control policy, so students’ clerkship training was unaffected. Thus, the practical application of VDC was also unaffected and could be analysed in this study. In fact, due to COVID-19, self-learning, and hence, effective self-learning tools, have become essential for teaching-learning processes. Once the clinical training course finished, the students were required to complete some homework regarding their training at the Family Dentistry Department. This homework was included in the qualitative analysis.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 20.0. For all statistical tests, a significance level of p < 0.05 was used. Regarding the validation process, details pertaining to the content validity are provided in the Appendix. To compare the difference between the responses of experts and novices to each item, the Likert scale was changed to agree (4 ≥) and disagree (≤ 3) for the Fisher’s exact test, to compare the differences between rates of correct scores of experts and novices for each theme, the impressions of VDC, and their evaluation of game quality and usability for education (construct validity and face validity). We used independent sample t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to analyse the influence of game-playing habit, learning strategies, and VDC experiences on qualification test and performance scores of each department (concurrent validity and predictive validity). Regarding the application stage, we again used Fisher’s exact test to compare the extents of self-learning and VDC recommendation of clerkship students before and after COVID-19 epidemic. A qualitative analysis was conducted to summarise the recommendations of the students.

Results

Content validity of the themes

The original S-CVI/Ave of themes ranged from 0.73 to 1.0. After modifying six items, the S-CVI/Ave of all the themes improved, as shown in .

Table 1. The S-CVI of VDC

Correct answer rate comparison between experts and novices

shows the comparison of correct answer rates when playing VDC between PGY dentists and clerkship dental students. The PGY dentists achieved 100.0% correct rate on all themes. The easiest theme for clerkship students was ‘X-ray arrangement’ (100.0% correctness), followed by ‘dental clinic environment’ (78.6%). The themes regarding ‘whole-person care’ and ‘orthodontics’ were difficult for them. The comparison revealed significant differences between experts and novices.

Table 2. The proportions of full score between expert and novice

Impressions of VDC

The clerkship students reported that the most positive impression of VDC was ‘effective in education’ (92.9%), followed by ‘teach dental knowledge’ (85.7%); the PGY dentists reported that the most positive impression was ‘teach clinical skills’ (100.0%). Overall, the clerkship students and PGY dentists had a positive attitude toward VDC’s educational values and showed no significant differences for any item ().

Table 3. The impressions of VDC

Game quality and usability for education

shows the game quality and usability as evaluated by clerkship students and PGY dentists. The most positive evaluation was for ‘the test design is good for learning’ from the clerkship (85.7%) and ‘it’s good for preview’ (88.9%) from the PGY dentists. Overall, the clerkship students and PGY dentists had a positive attitude toward VDC’s game quality and usability. There were no significant differences between the responses of the two groups for any item.

Table 4. Game quality and usability of VDC

Qualification and academic achievements

Of the 34 (21 [61.8%] men; 13 [38.2%] women) dental students who participated in this study 22 (64.9%) reported that they often played video games. Regarding their learning strategies, ‘self-learning’ was rated as the most important strategy (n = 24, 70.6%), followed by ‘practice’ (n = 23, 67.6%), ‘reading’ (n = 20, 58.8%), ‘video’ (n = 19, 55.9%), ‘problem-based learning’ (n = 13, 38.2%), and ‘lectures’ (n = 11, 32.4%). When the aforementioned variables were compared to their qualification test scores and academic achievements in different specialties, there were no significant differences, except in the specialty of Oral Pathology & Maxillo-Facial Radiology for which men received higher average scores (Data not shown).

Regarding the VDC experience, 13 (38.2%) reported that they never used VDC as a self-learning tool during their clerkship, 9 (26.5%) reported that they used VDC once, 11 (32.4%) reported using VDC twice, and 1 (2.9%) using it thrice. shows the associations between self-learning experience of VDC, the score on the qualification test, and academic achievements in different specialties. The results showed that the students who used VDC gained significantly higher scores on the qualification test. The VDC experiences may, thus, significantly predict higher scores on periodontics and endodontics.

Table 5. VDC experiences and student performances

Practical application during the COVID-19 pandemic

There were 52 students who completed clerkship training in the Family Dentistry Department before the cautionary restrictions due to the pandemic from the Taiwan government, which began on 21 January 2020. Another 40 students finished their training during the pandemic itself. The number of patients reduced during this period and the students had more time to utilise the self-learning tools. In their homework, 18 (34.6%) students mentioned self-learning tools and only one mentioned VDC before the pandemic. After the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, 17 (42.5%) students reported the utilisation of self-learning tools (p = 0.440). However, a significantly higher proportion of students (n = 7, 17.5%) confirmed the value of VDC as an assistive tool for learning clinical reasoning (p = 0.019). The comments from students are summarised in . The students viewed the VDC as a self-directed learning tool which provided them with opportunities to practice treatment procedures and familiarise themselves with clinical operations, while simultaneously having fun.

Table 6. Summary of VDC mentioned in the students’ homework

Discussion

This study describes the successful establishment of a simulated serious game for learning clinical reasoning in a dental clinic. The VDC showed good validity and a high potential for education in practice.

Using serious games can provide a safe and effective practice environment, but the development of these games must blend subject matter content, instructional design, learning objectives, and engaging game design to encourage learners to practice and develop their skills. The main goal of this study was to test VDC as an educational tool and to determine its effect on student knowledge and clinical reasoning; it may help close the gap between preclinical and clinical training. According to Bloom’s Taxonomy classification [Citation22,Citation23], there are six progressive levels of learning; from the foundation to the pinnacle, these are: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. In this study, we assumed that the learner should be able to apply a concept, solve a problem by using or examining gained knowledge and understanding in some manner; hence, the game is targeted at the intermediate level in the Taxonomy. In the VDC game described above, the learner (player) must apply their knowledge of dental treatment procedures to answer questions, such as identifying the various instruments based on a given dental procedure. The game, hence, improves their clinical reasoning and learning outcome.

In this study, serious gaming successfully provided an alternate option for self-learning, and offered a similar experience and outcome to the other methods concerning dental education. The exploratory analysis showed that students who used VDC gained significantly higher scores on the qualification test and the VDC experiences significantly predicted better performances on periodontics and conservative dentistry. However, in the performance score of periodontics, the students who play VDC twice or more did not show a significant improvement. Periodontics requires more training in communication skills than conservative dentistry, to improve patients’ oral hygiene better. The VDC themes did not include scenes of virtual patients, which might be the cause of contradiction. In this study, at least the better knowledge gains and clinical reasoning skills in conservative dentistry can be attributed to playing VDC. In conservative dentistry, students learn to preserve teeth by treating caries and pulpitis. Students playing VDC showed an increase in their knowledge about treatment of caries and pulpitis. The results are similar to those of a previous study [Citation24] in which students had a free choice on using a serious game in addition to formal teaching. Regardless of the type of study design, students using serious games appear to display at least similar, and sometimes even better, levels of knowledge and retention, skills development, and satisfaction than those not using these games [Citation9,Citation25,Citation26].

Overall, the students and residents evaluated VDC as highly usable for preview and learning. Students’ and residents’ impression of VDC was positive. They had a higher positive impression of VDC in teaching clinical skills, effectiveness in education, and having fun. Playing with VDC was fun for the students, since they mentioned that they wanted to play again. This is an important precursor for motivated learning. Learners were motivated and reinforced to learn through fun and competition of serious games [Citation27]. Although only 65.2% of the participants agreed that VDC is necessary for learning at the validation stage, it indicates a potential for application when real patients are not available during clinical practice.

Dental visits are a high-risk activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. After the COVID-19 outbreak, there was a reduction in the non-urgent dental care cases and dental emergency utilisation [Citation28]. The impact of the pandemic has a certain influence on clinical skill training in clerkship which is the important infrastructure of dental education [Citation1]. Based on the students’ feedback in this study, positive attitudes toward VDC use increased after the COVID-19 outbreak. It indicates that VDC provides an alternative way of learning for students during an extraordinary period when inflow of actual patients reduced. This further exhibits the usability of such games in teaching. On the other hand, serious games or virtual patients cannot replace the actual clinical training course because not all students may be interested in this learning style. Nevertheless, in the post-COVID-19 era, the model of dental education can be made more innovative to suit different situations and novel intelligent technology should be applied for future dental education [Citation1].

Limitations

This study had some limitations. Firstly, the case scenarios were limited to tooth caries and tooth pulpitis, and the procedural knowledge was assessed concerning only these clinical conditions. Thus, future studies should include a wider range of clinical cases. Secondly, the game quality of VDC was acceptable but not optimal; its user friendliness should be enhanced. Thirdly, the data could not be collected using the logging system of the game; this included when and how long each student logged into the game, how many times each student submitted their answers, and what answers they submitted. The future VDC should rectify these limitations to achieve a better serious game.

Finally, in this study, students’ game-playing habit and learning strategies were not found to have a significant influence on their academic performance; however, there may be other variables that confound the results. For example, academic performance before clerkship was not considered in this study. Considering the relearning feature of game design and the lack of a function for data collection, convenience sampling and quasi-experimental ex post facto design were adopted in this study’s validation process. Therefore, it is suggested that further research use rigorous randomised control trials to confirm/support this study’s findings.

Conclusions

The VDC as an educational tool and its effectiveness on clinical reasoning skill and knowledge gain among clerkship dental students have been validated and confirmed in this study. Students using VDC gain significantly higher scores on performance and qualification test. In addition, the VDC shows a high potential as an assistive self-learning tool in clinical training environment, especially relevant and pertinent after the COVID-19 outbreak.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chang TY, Hong G, Paganelli C, et al. Innovation of dental education during COVID-19 pandemic. J Dent Sci. 2021;16(1):15–11.

- Ryan MS, Feldman M, Bodamer C, et al. Closing the gap between preclinical and clinical training: impact of a transition-to-clerkship course on medical students’ clerkship performance. Acad Med. 2020;95(2):221–225.

- Serrano CM, Botelho MG, Wesselink PR, et al. Challenges in the transition to clinical training in dentistry: an ADEE special interest group initial report. Eur J Dent Educ. 2018;22(3):e451–e457.

- Manogue M, McLoughlin J, Christersson C, et al. Curriculum structure, content, learning and assessment in European undergraduate dental education - update 2010. Eur J Dent Educ. 2011;15(3):133–141.

- Cook DA, Hatala R, Brydges R, et al. Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306(9):978–988.

- Ke F, Xie K, Xie Y. Game-based learning engagement: a theory- and data-driven exploration. Br J Educ Technol. 2016;47(6):1183–1201.

- Jabbar AIA, Felicia P. Gameplay engagement and learning in game-based learning: a systematic review. Rev Educ Res. 2015;85(4):740–779.

- Kron FW, Gjerde CL, Sen A, et al. Medical student attitudes toward video games and related new media technologies in medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):50.

- Sipiyaruk K, Gallagher JE, Hatzipanagos S, et al. A rapid review of serious games: from healthcare education to dental education. Eur J Dent Educ. 2018;22(4):243–257.

- Perry S, Bridges SM, Burrow MF. A review of the use of simulation in dental education. Simul Health. 2015;10(1):31–37.

- Amer RS. Development and evaluation of an interactive dental video game to teach dentin bonding. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(6):823–831.

- Hannig A, Lemos M, Spreckelsen C, et al. Skills-O-Mat: computer supported interactive motion- and game-based training in mixing alginate in dental education. J Educ Comp Res. 2013;48(3):315–343.

- Sipiyaruk K, Gallagher JE, Hatzipanagos S, et al. Acquiring critical thinking and decision-making skills: an evaluation of a serious game used by undergraduate dental students. DPH Technol Knowledge Learn. 2017;22(2):209–218.

- Hsu T-C, Tsai SSL, Chang JZC, et al. Core clinical competencies for dental graduates in Taiwan: considering local and cultural issues. J Dent Sci. 2015;10(2):161–166.

- Olszewski AE, Wolbrink TA. Serious gaming in medical education: a proposed structured framework for game development. Simul Healthcare. 2017;12(4):240–253.

- Graafland M, Schraagen JM, Schijven MP. Systematic review of serious games for medical education and surgical skills training. Br J Surg. 2012;99(10):1322–1330.

- Schijven MP, Jakimowicz JJ. Validation of virtual reality simulators: key to the successful integration of a novel teaching technology into minimal access surgery. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2005;14(4):244–246.

- Gallagher AG, Ritter EM, Satava RM. Fundamental principles of validation, and reliability: rigorous science for the assessment of surgical education and training. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(10):1525–1529.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):489–497.

- Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(4):459–467.

- Wang SY, Chen CH, Tsai TC. Learning clinical reasoning with virtual patients. Med Educ. 2020;54(5):481.

- Bloom BS, Englehart, MD, and Furst, EJ et al. Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals, Bloom BS, ed . In: Handbook 1; Cognitive Domain. New York (NY): David McKay Co. Inc; 1956. p. 7–8.

- Buchanan L, Wolanczyk F, Zinghini F. Blending Bloom’s taxonomy and serious game design. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Security and Management (SAM); Athens. Athens: The Steering Committee of The World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering and Applied Computing (WorldComp); 2011. p. 1–6.

- Chon SH, Timmermann F, Dratsch T, et al. Serious games in surgical medical education: a virtual emergency department as a tool for teaching clinical reasoning to medical students. JMIR Serious Games. 2019;7(1):e13028.

- Gentry SV, Gauthier A, Ehrstrom BL, et al. Serious gaming and gamification education in health professions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e12994.

- Sharifzadeh N, Kharrazi H, Nazari E, et al. Health education serious games targeting health care providers, patients, and public health users: scoping review. JMIR Serious Games. 2020;8(1):e13459.

- Blakely G, Skirton H, Cooper S, et al. Educational gaming in the health sciences: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(2):259–269.

- Wu JH, Lee MK, Lee CY, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the utilization of dental services and attitudes of dental residents at the emergency department of a medical center in Taiwan. J Dent Sci. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2020.12.012.