ABSTRACT

The teaching of medical humanities is increasingly being integrated into medical school curricula. We developed a podcast called Le Serment d’Augusta (Augusta’s Oath), consisting of six episodes tackling hot topics in the modern world of healthcare related to the patient-doctor relationship, professionalism, and ethics. This podcast aimed to provide scientific content in an entertaining way, while promoting debate among medical students. The Le Serment d’Augusta podcast was proposed as one of the various optional modules included in the second- to fifth-year curriculum at the School of Medicine of Sorbonne University (Paris). We asked students to report their lived experience of listening to the podcast. We then used a text-mining approach focusing on two main aspects: i) students’ perspective of the use of this educational podcast to learn about medical humanities; ii) self-reported change in their perception of and knowledge about core elements of healthcare after listening to the podcast. 478 students were included. Students were grateful for the opportunity to participate in this teaching module. They greatly enjoyed this kind of learning tool and reported that it gave them autonomy in learning. They appreciated the content as well as the format, highlighting that the topics were related to the very essence of medical practice and that the numerous testimonies were of great added value. Listening to the podcast resulted in knowledge acquisition and significant change of perspective. These findings further support the use of podcasts in medical education, especially to teach medical humanities, and their implementation in the curriculum.

Introduction

Recent societal factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, an increased awareness of economic and climatic issues, and the #MeToo movement have contributed to a change in our perception of the outside world, our bodies, and what we expect from a healthcare relationship. In this context, patients and professional healthcare communities alike are showing a growing interest in open discussion about these burning issues [Citation1,Citation2]. Additionally, the combination of scientific evidence and experiential knowledge is highly valued by patients and their families, and there is an increasing awareness of the perceived lack of communication and emotional barriers created by some doctors [Citation3–5] Indeed, developing an effective and empathetic relationship with the patient is at the heart of medical professions, and is known to improve quality of care and patient outcomes [Citation6,Citation7]. This refers to the medical humanities, which is a growing interdisciplinary field that explores the engagement and exchange between human experience and the world of medicine [Citation8–10]. ‘Difficulty in supporting the humanities in medicine depends on perspectives of learning’ [Citation11].

To address these topics, attractive teaching aids that encourage discussion and reflection among students, and that fit in with their lifestyle, could be of great interest [Citation12]. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the relationship between learning and mobility has changed in health education [Citation13]. Students seem to want more autonomy and control over their learning, and some of them believe that there are ways of learning other than face-to-face, in line with their perception of the working world. Among alternative forms of media outlets and digital forms that can serve this purpose, podcasts are popular educational tools [Citation14–16]. Because of their accessibility, flexibility and entertaining format [Citation14,Citation17–19], they are particularly adapted to our post COVID-19 world [Citation13,Citation18,Citation20]. They are also easy to share via messaging, or on social media, which increases impact, and can suit everyone’s learning pace [Citation19,Citation21]. Learning through podcast may be seen as a ‘passive’ way of learning [Citation19], but a more active component can be added (e.g., post-listening individual written comments or group debate sessions), to optimize information retention [Citation22,Citation23]. Finally, learning through podcasts intrinsically increases students’ control and autonomy, which are well known determinants of motivation to learn according to the dynamic model of motivation [Citation24]. Medical education podcasts have been increasingly used in the past decade [Citation25–28], although their effectiveness and optimal use is still poorly known [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14]. A scoping review of podcast use in medical education found that 55–90% of listeners reported changing their practice after listening to a podcast [Citation29]. One such podcast entitled ‘Not Otherwise Specified’ hosted by Dr. Lisa Rosenbaum [Citation30], covers medical humanities, the acquisition of which is critical for the practice of medicine [Citation31].

In this context, we developed a podcast about medical humanities called Le Serment d’Augusta (Augusta’s Oath) in partnership with Binge Audio (an independent French podcast production company). The title refers to Augusta Klumpke who was the first woman to obtain a residency in Paris; she went on to become a researcher and a pioneer in the field of neurology, especially in neurorehabilitation therapy [Citation32].

The aim of this study was to analyze the participating students’ lived and subjective experience of listening to the podcast using a text-mining approach [Citation33], focusing on two aspects: i) the students’ perspective about the use of this podcast as a tool to learn medical humanities; and ii) how listening to our podcast could change their perception and knowledge of core elements of healthcare in our modern world.

Methods

Study approval and consent

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Sorbonne University. The work was carried out in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. All acquired data were anonymized and written consent was obtained from the participants.

Study design and population

The study was based on an online survey and was conducted from October 2022 to June 2023 at the Medical School of Sorbonne University, Paris, France. Second- to fifth-year medical students were invited to voluntarily participate in the medical education program Le Serment d’Augusta, proposed as one of the various optional modules included in the curriculum https://www.binge.audio/actualites/le-serment-daugusta. This pilot learning experience consisted of listening to six podcast episodes over the 9-month period of the academic year. To validate having completed the module, the students had to: i) give their written opinion about the topics before listening to the episodes; ii) write a comment for each episode (Questions 1 to 6 – Q1 to Q6) explaining whether and how listening to the podcast changed their mind or not; and iii) give their general opinion about the podcast as a teaching medium (Question 7 – Q7). The students were asked to produce at least 100 words per question and not to use any idioms, acronyms, or implicit references. They were informed in advance that the content of their comments would not influence validation of the test. Additional data about the participants were collected: age, sex, presence of healthcare professionals among close relatives (yes/no), and perceived level of material comfort (very bad, bad, medium, good, very good). After anonymization of the data, responses to the questions (Q1-Q7) were analyzed for research purposes.

Intervention

The podcast Le Serment d’Augusta aims to teach medical humanities and doctor/patient relationships to medical students. The ‘Serment’ evokes the Hippocratic Oath, suggesting that medical students can reinvent their future commitment as medical doctors. The goal was to provide reliable, scientific content using an innovative format while promoting debate among medical trainees. In addition, it was designed to allow many people to express and share different opinions on sensitive subjects. It is a free resource, available to all students and to the general public, and free from advertising. It comprises one prologue and six episodes, each lasting around 50 minutes. Episode 1 (‘I will think of bodies outside the norm’) uses the paradigm of ‘fatphobia’ to discuss representation biases among healthcare professionals, which often result in discrimination. Episode 2 (‘I will cultivate a benevolent and inclusive solidarity’) narrates experiences of solidarity among healthcare professionals (especially during the COVID-19 pandemic) to decipher the systemic and cultural factors likely to influence solidarity and have consequences on quality of care. Episode 3 (‘I will seek consent actively and at each instant’) uses the paradigm of gynecological violence to explore the various aspects of consent to care in clinical practice. Episode 4 (‘I will take care of myself to take care of others’) focuses on mental health issues in healthcare professionals, especially the consequences on quality of care and the difficulties that may prevent healthcare professionals from asking for help. Episode 5 (‘I will look a little further for the truth’) questions the concept of scientific truth with examples from the COVID-19 pandemic. Episode 6 (‘I will look after those I cannot see’) focuses on healthcare for prisoners, emphasizing that this population is disadvantaged in terms of health and requires an active effort from healthcare professionals to compensate for disparity.

Data preprocessing and analyses

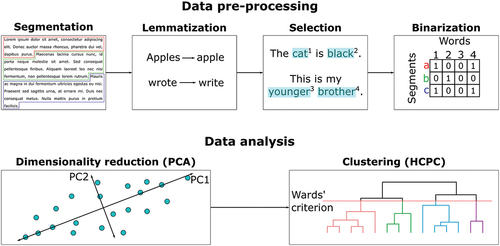

The analysis of the podcast as a whole (Q7) and of each episode (Q1-Q6) required the following steps (see ):

Figure 1. Data analysis pipeline. The data were first preprocessed (i.e., segmentation, lemmatization, word selection, binarization) and then analyzed (i.e., PCA, HCPC).

Step 1: each student commentary was decomposed into smaller units called ‘segments’ of approximately 40 words by respecting, when possible, sentences and punctuation;

Step 2: each segment was lemmatized, which means that each word was transformed into its most basic form (no conjugation, no agreement)

Step 3: words were selected based on the following criteria: they had to be composed of at least three letters, used by at least 5% of the participants, and be part of the following groups: adjectives, adpositions, adverbs, interjections, nouns, proper nouns, verbs (as tagged by the spacyr package [Citation18]; https://spacy.io/) Punctuation, numbers, symbols or ‘stop words’ (i.e., words of very high frequency and nonspecific meaning, e.g., ‘the’, ‘this’, ‘it’ etc.) were not selected.

Step 4: a binary matrix was built for each corpus (i.e., all segments extracted for one specific question), which included all text segments as rows and all selected words as columns. The number ‘1’ was used when a word was used in a segment, while ‘0’ was used when a word was missing in a segment.

Step 5: we applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the raw binary matrices to reduce the data complexity to only keep the most important information (i.e., the first five dimensions).

Step 6: finally, we applied a Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (HCPC). The optimal number of clusters was determined using the Ward’s criterion (i.e., threshold based on the selection of the option which leads to the highest relative loss of inertia)

To describe the clusters, we used a combination of v.test on the words (i.e., identify if a given word was more likely to be found in a specific cluster in comparison with the whole corpus) and a specificity test on the segments (described in Appendix 1). The 10 segments of each cluster with the lowest score were considered the most specific and they were used to interpret the meaning of the cluster. Lastly, we computed the proportion of each cluster found in the comments of each participant to investigate any statistical associations with socio-demographic variables using Anova or linear regression models, respectively, for categorical and numerical variables. The threshold for significance was set at p ≤ 0.05 following the Bonferroni correction.

All the data preprocessing and analyses of the raw textual data (i.e., in French; translation into English was only done to report results) were performed using the free software R [Citation34].

Results

Main characteristics of the medical students

Among a potential population of 1807 students (70.7% women [n = 1277]), mean age 22.2 years (SD = 2.6), 478 students were included in the study. The mean age of the participants was 21.5 years (SD = 1.9), with an over-representation of women (80.9% [n = 365]). Most participants claimed to live in good or very good conditions (very good: 35.4% [n = 158], good: 46.6% [n = 208], medium: 15.2% [n = 68], bad: 2.2% [n = 10], very bad: 0.4% [n = 2]). Most participants did not have healthcare professionals among their close relatives (no: 69.6% [n = 312].

There was no significant association between response patterns and the students’ characteristics.

General opinion about the podcast

Our analysis showed that the podcasts were appreciated both for their content because the topics touch on the essence of medicine and a doctor’s values, and for their format because of the use of audio files and testimonials. The students described the podcast as being an ‘interesting’, ‘playful’, and ‘easy’ teaching tool. They were grateful to have had access to the podcast and emphasized that this type of medium allows autonomy of learning (e.g., pausing; double-tasking). With regard to the module validation method, they reported that they enjoyed making comments because it encouraged them to reflect on the topic covered by the episode and to see how their thinking evolved. Some students provided recommendations for a better mode of validation.

Episodes 1–6

Students gained awareness about representation bias and the normative body in medicine, and about the role of psychological factors in obesity in Episode 1 (‘Representation bias and discrimination in healthcare’). They became aware of the extent of fatphobia and prejudice against overweight people in the healthcare field, and of the negative consequences this has on the quality of care. They learned how to tackle this issue by creating a trusting, empathetic and inclusive relationship, and how to better address the issue of weight during a consultation.

In Episode 2 (‘Solidarity among healthcare professionals’), most of the students appreciated that the traditional culture of French medical schools was about to change by eliminating the discriminatory component – in particular sexist stereotypes – to become more respectful and inclusive. They realized the importance of solidarity and team spirit among healthcare professionals to ensure good quality of care.

Students learned what consent to healthcare was, how important it was, and how to obtain consent in clinical practice in Episode 3 (‘Consent to healthcare)’. The focus was on the fact that consent should be ‘explicit’ and that obtaining consent to healthcare is an active, ongoing process that depends essentially on a relationship of trust between patient and doctor. The students realized that progress needed to be made on the issue of consent, especially in the context of gynecological examinations.

In Episode 4 (‘Mental health of healthcare professionals‘), they also realized that mental health issues were very common among medical students and healthcare professionals, due to healthcare professionals’ particular vulnerability to psychological difficulties and the pressure they face to keep working. They stated they would pay special attention to the difficulties their colleagues might encounter. They became aware that caring for themselves was crucial and that they should not be ashamed to ask for help. Some students mentioned that they felt less lonely/isolated about their psychological problems after listening to the episode.

After listening to Episode 5 (‘Scientific truth’), students learned that scientific truth is by nature ephemeral and fragile, and realized the critical influence of social networks on the transmission and dissemination of scientific information, with the risk of reading ‘fake news’ and/or being trapped in a filter bubble. They became more eager to stay well-informed throughout their careers from primary-sourced information on reputable websites, so as to provide optimal care to their patients and respond to their questions appropriately.

Finally, they gained a new perspective on the issue of people excluded from the healthcare system in Episode 6 (‘Populations with loss of healthcare opportunities’). They learned about the need to make special efforts to provide appropriate care for disadvantaged or marginalized persons, particularly with regard to the quality of human interaction. More specifically they became aware of the fact that prisoners can be deprived of healthcare, especially in the context of psychiatric disorders and chronic illnesses, and that imprisonment itself is a significant ‘cause’ of morbidity and mortality.

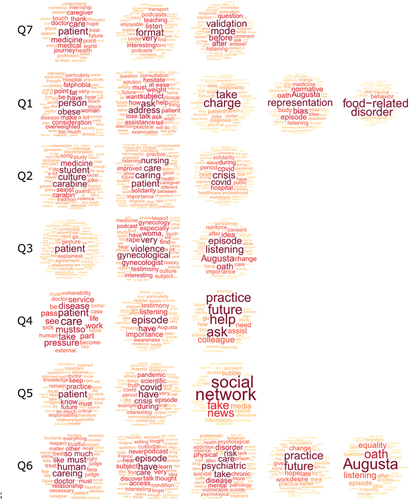

The main points related to opinions about each episode (1 to 6; Question 1 to 6) are summarized in and Boxes 1–7 whereas detailed analysis is provided as a supplementary result (Appendix 2).

Figure 2. Word clouds displaying significant words obtained for each cluster of questions Q1-Q7. Only words with a significant positive v.Test are shown (i.e., indicating over-representation within the cluster compared with other clusters). The size, color, and location of the words depend on their importance (i.e., a higher v.Test score is represented by a larger word, in red and centered).

Discussion

This text-mining analysis of students’ lived experience of listening to the six-episode teaching podcast Le Serment d’Augusta, shows that they were grateful to have had the opportunity to participate in the teaching module. They greatly appreciated the podcast format as a learning tool and explained that it gave them better control of their learning with the possibility of double-tasking (such as listening during commute times) and self-pace learning. As well as the format, they also enjoyed the content emphasizing that the topics were related to the very essence of medical practice and that the multiple testimonies were of great added value. Listening to the podcasts resulted in increased awareness about topics related to medical humanities and changed their perspective. These findings further support the use of podcasts in medical education, especially to teach medical humanities and their implementation in the curriculum.

A podcast to teach medical humanities

To the best of our knowledge, Le Serment d’Augusta is the first podcast about medical humanities that has been formally included in a medical student curriculum. Listening to our podcast was optional at the time of the study but has since become part of the curriculum for all students after this positive pilot experience.

Among the medical podcasts currently available, only a small proportion are produced by universities or professional societies, and advertising (not present in our podcast) is common [Citation35]. Although rare, a few podcasts summarizing or presenting medical and scientific data have been produced and selectively target medical students. For example, two podcasts, containing key points from lectures and morning reports, have been developed for internal medicine residents in the USA [Citation36,Citation37]. Listeners found that it was an effective educational supplement that strengthened the links between the faculty and residents [Citation36,Citation37]. Interestingly, the Mayo Clinic has made podcasting part of their academic portfolios [Citation38]. Other types of podcasts discussing equity in care and structural racism with a focus on medicine are available on the Internet but are not included in a curriculum [Citation17]. These podcasts are designed to increase the listener’s awareness, and start important conversations on social media [Citation17], which is a first step towards changing practices. The availability of Le Serment d’Augusta to all health professionals and the general public aims to encourage open debate and develop a sense of community. We think that integrating such a podcast into the curriculum is a critical step to prioritize topics related to the patient-doctor relationship, and underlines the importance of medical humanities. Our study showed that the topics covered in Le Serment d’Augusta were highly relevant to the students. With these podcasts we aimed to fill a gap in the current clinical learning curriculum in France by encouraging students to reflect on and debate topics that are not often discussed in conventional training [Citation12]. The teaching of medical humanities is an increasingly important subject in the medical school curriculum [Citation11,Citation39,Citation40] in an overall context of heightened societal awareness of the importance of diversity and inclusion which is especially relevant in the quality of the healthcare professional/patient relationship. Such teaching can improve medical professionalism, critical thinking, clinical judgement, empathy, communication, and the appreciation that patients’ problems go beyond the biology and consequently impact healthcare outcomes. It can also help prepare students for their future career and their adaptation to work-related stress [Citation41,Citation42]. While students value the existence of dedicated teaching of the humanities as a complement to biomedical teaching [Citation43,Citation44], efforts to widely integrate this teaching into the curriculum remain limited in France, partly due to time constraints and work overload. To achieve greater inclusion in the curriculum, medical humanities should ideally be incorporated into the curriculum through the lens of biomedical science and clinical practice [Citation45,Citation46]. A podcast thus represents a well-suited option considering the potential limitations and characteristics of the optimal learning content. Other educational strategies could be relevant to teach medical humanities such as (but not limited to) problem-based learning, team-based learning, standardized patients exercise, special interest groups, and interactions with a patient-as-a teacher [Citation2,Citation47–49]. These approaches would likely require more curricular time and space but may also foster student engagement.

Teaching levers and episode duration

Podcasting allows the communication of information for medical students alongside entertainments program [Citation21]. The positive perception of students and the quality of learning achievement after listening to our podcast could be related to the specific pedagogical levers we applied to ensure effectiveness and student involvement/satisfaction: i) we used powerful storytelling techniques sustained by a narrative structure and strong testimonies, along with immersive soundscape and music. Storytelling is an effective tool to teach medical topics [Citation50] and can also help medical students cope with the challenges of healthcare relationships during their first field experiences [Citation51]. ii) we approached topics from a transdisciplinary perspective so that students can listen to interviews and/or quotes of academics from both medical and social sciences. This transdisciplinary perspective can offer unique opportunities for meaningful connections to be made between the humanities and clinical experience [Citation52]; iii) we included patient experiential knowledge to foster empathy towards patients [Citation53,Citation54]; iv) we integrated testimonies from medical students and young physicians, helping the audience to identify with their stories [Citation55,Citation56]. To make full use of these teaching levers, we chose a format of around 50 minutes per episode. This duration is unusually long compared to most medical education podcasts which are usually of a recommended duration of 15-20mn [Citation14,Citation57]. When podcasts are used to help memorize lectures, medical students have been found to report that even a duration as short as 3–5 minutes could be optimal [Citation58]. However, our students did not comment negatively about the duration of the episodes. Finally, it is worth noting that we met the suggested consensus quality criteria for podcasts used in medical education comprising easy access, citing references and disclosing conflicts of interest, clearly identifying authors, and making a clear distinction between facts and opinions [Citation22]. Overall, our approach aims to develop personal responsibility for learning: the students were expected to listen to each episode, and we hoped the podcast would stimulate reflection after presenting a variety of viewpoints and food for thought. However, we cannot be certain that they actually wrote their comments themselves and did not use generative artificial intelligence [Citation59]. A reasonable option to partially address this issue would be to supplement podcast listening and written comments with group debates.

Strengths and limitations

The study was innovative in that we used a text-mining approach to analyze the students’ opinions of their teaching program through free written expression i) with no a priori, ii) with the emphasis on ‘natural language’ data to evaluate the students lived experience, and iii) analyzing a large volume of textual data reflecting the experience of 478 students. Data mining is a qualitative or hybrid approach [Citation60] since i) it is based on qualitative data, ii) it often requires having a deep knowledge of the corpus, and iii) it was found to produce results mostly comparable to those obtained with manual approaches [Citation61]. Data mining is relevant for many different objectives including summarizing texts, extracting terminology, identifying important topics, assessing the emotional tone of a text, or reviewing the literature [Citation62]. Our team already used data mining to identify the daily-living experience of teenagers suffering from Tourette syndrome [Citation63]. In education [Citation33,Citation64,Citation65], data mining can be useful for student evaluation [Citation66], or for determining student satisfaction with a teaching module [Citation67,Citation68]. Text-mining has also been used to provide a better understanding of curricula offered by many higher education institutions thereby helping students decide which one they want to join [Citation69]. This kind of approach has already been used to identify and correct aspects which make learning difficult [Citation70], use sentiment analysis to enhance pedagogy [Citation71], determine factors that increase student satisfaction [Citation72], and to explore the impact of socialization on the formation of students professional identity [Citation73]. In our study, it enabled us to identify any difficulties or disagreement about the form or content of the podcasts.

Some limitations deserve to be mentioned. First, generalizability of our results might be compromised because all the participants were from the same medical school in Paris and may not be representative of a general population of medical students in France. In addition, participation was optional, and we suspect that students with a keen interest in podcasts would have been more likely to participate in the teaching program, thereby introducing a potential recruitment bias. Second, the students’ responses might have been influenced by a social desirability bias or by the fear that their content could interfere with the validation process in spite of us making it clear from the beginning that the content of the response would not influence the validation process.

Although our questions were open-ended and the students could answer whether they had not changed their minds or not after listening to a podcast, the way we formulated the question may have skewed the results by inappropriately encouraging them to mention a change of mind. The absence of a control group and randomization prevented us from mitigating the selection and measurement biases.

Conclusion

Our findings support the incorporation of podcasts in the medical curriculum to teach medical humanities. It is, however, important to keep in mind that most studies have assessed the educational value of podcasts based on subjective criteria and not on the consequences on patient care [Citation14,Citation29,Citation74]. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of such a learning approach on the quality of care. In some cases, podcasting is a way for physicians to start a dialogue with patients [Citation21,Citation41]. A podcast – such as Le Serment d’Augusta - as part of the medical curriculum but also being freely available to the general public online, could foster an ongoing conversation between patients and physicians within the society.

Box 1: Opinions about learning with the podcast Le Serment d’Augusta. For topics corresponding to each cluster, this box shows a selection of representative segments chosen among the ten with the lowest (best) Specificity score of each cluster.

Box 2: Students” change of mind after listening to episode 1 (Representation biases and discrimination in healthcare). For topics corresponding to each cluster, this box shows a selection of representative segments chosen among the ten with the lowest (best) Specificity score of each cluster.

Box 3: Students’ change of mind after listening to episode 2 (Solidarity among healthcare professionals). For topics corresponding to each cluster, this box shows a selection of representative segments chosen among the ten with the lowest (best) Specificity score of each.

Box 4: Students’ change of mind after listening to episode 3 (Consent to healthcare). For topics corresponding to each cluster, this box shows a selection of representative segments chosen among the ten with the lowest (best) Specificity score of each.

Box 5: Students’ change of mind after listening to episode 4 (Mental health of healthcare professionals). For topics corresponding to each cluster, this box shows a selection of representative segments chosen among the ten with the lowest (best) Specificity score of each.

Box 6: Students’ change of mind after listening to episode 5 (Scientific truth). For topics corresponding to each cluster, this box shows a selection of representative segments chosen among the ten with the lowest (best) Specificity score of each.

Box 7: Students’ change of mind after listening to episode 6 (Populations with loss of healthcare opportunities). For topics corresponding to each cluster, this box shows a selection of representative segments chosen among the ten with the lowest (best) Specificity score of each.

Appendix 2_R2_Clean.docx

Download MS Word (19.5 KB)Disclosure statement

Barabara Soumet-Leman received money from Binge Audio for her work on the podcast ‘Le Serment d’Augusta’. Other authors have no potential conflict of interest to report.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2024.2367823

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zhou Y, Ma Y, Yang WFZ, et al. Doctor-patient relationship improved during COVID-19 pandemic, but weakness remains. BMC Fam Pract. 2021 Dec;22(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01600-y

- Chung EK, Rhee JA, Baik YH, et al. The effect of team-based learning in medical ethics education. Med Teach. 2009 Jan;31(11):1013–13. doi: 10.3109/01421590802590553

- Perera HJM. Effective communication skills for medical practice. J Postgrad Inst Med. 2015 Nov 27;2:20. doi: 10.4038/jpgim.8082

- So M, Carlson K. “We want to be heard”: perspectives on mental health care among patients at a federally qualified health center. Behav psycho mental illness [Internet]. Am Acad Family Phys. 2022 cited 2023 Aug 25:3167. Available from: http://www.annfammed.org/lookup/doi/10.1370/afm.20.s1.3167

- Wofford MM, Wofford JL, Bothra J, et al. Patient complaints about physician behaviors: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2004 Feb;79(2):134–138. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00008

- Chipidza FE, Wallwork RS, Stern TA. Impact of the doctor-patient relationship. Prim care companion CNS disord [internet]. 2015 Oct 22 cited 2023 Aug 20. Available from: http://www.psychiatrist.com/PCC/article/Pages/2015/v17n05/15f01840.aspx

- Wang F, Song Z, Zhang W, et al. Medical humanities play an important role in improving the doctor-patient relationship. BST. 2017;11(2):134–137. doi: 10.5582/bst.2017.01087

- Hurwitz B. Medicine, the arts and humanities. Clin Med. 2003 Nov;3(6):497–498. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.3-6-497

- Evans M, Greaves D. Exploring the medical humanities. BMJ. 1999 Nov 6;319(7219):1216–1216. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7219.1216

- Macnaughton J. Medical humanities’ challenge to medicine. Evaluation Clin Pract. 2011 Oct;17(5):927–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01728.x

- Gull SE. Embedding the humanities into medical education. Med Educ. 2005 Feb;39(2):235–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01974.x

- Sherbino J, Arora VM, Van Melle E, et al. Criteria for social media-based scholarship in health professions education. Postgrad Med J. 2015 Oct 1;91(1080):551–555. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133300

- Jeffries PR, Bushardt RL, DuBose-Morris R, et al. The role of technology in health professions education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Med. 2022 Mar;97(3S):S104–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004523

- Cho D, Cosimini M, Espinoza J. Podcasting in medical education: a review of the literature. Korean J Med Educ. 2017 Dec 1;29(4):229–239. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2017.69

- Purdy E, Thoma B, Bednarczyk J, et al. The use of free online educational resources by Canadian emergency medicine residents and program directors. CJEM. 2015 Mar;17(2):101–106. doi: 10.1017/cem.2014.73

- Miesner AR, Lyons W, McLoughlin A. Educating medical residents through podcasts developed by PharmD students. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017 Jul;9(4):683–688. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.03.003

- Kamal S, Trivedi SP, Essien UR, et al. Podcasting: a medium for amplifying racial justice discourse, reflection, and representation within graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2021 Feb 1;13(1):29–32. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-20-00990.1

- Okonski R, Toy S, Wolpaw J. Podcasting as a learning tool in medical education: prior to and during the pandemic period. Balkan Med J. 2022 Sep 9;39(5):334–339. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.galenos.2022.2022-7-81

- Zanussi L, Paget M, Tworek J, et al. Podcasting in medical education: can we turn this toy into an effective learning tool? Adv In Health Sci Educ. 2012 Oct;17(4):597–600. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9300-9

- Newman J, Liew A, Bowles J, et al. Podcasts for the delivery of medical education and remote learning. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Aug 27;23(8):e29168. doi: 10.2196/29168

- Hurst EJ. Podcasting in medical education and health care. J Hosp Librarianship. 2019 Jul 3;19(3):214–226. doi: 10.1080/15323269.2019.1628564

- Raupach T, Grefe C, Brown J, et al. Moving knowledge acquisition from the lecture hall to the student home: a prospective intervention study. J Med Internet Res. 2015 Sep 28;17(9):e223. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3814

- Estes M, Gopal P, Siegelman J, et al. Individualized interactive instruction: a guide to best practices from the council of emergency medicine residency directors. WestJEM. 2019 Feb 28;20(2):363–368. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2018.12.40059

- Pelaccia T, Viau R. Motivation in medical education. Med Teach. 2017 Feb 1;39(2):136–140. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1248924

- Reid Burks A, Nicklas D, Owens J, et al. Urinary tract infections: pediatric primary care curriculum podcast. MedEdPORTAL. 2016 Aug 5;10434. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10434

- McCarthy J, Porada K. Serving up peds soup: podcast‐based paediatric resident education. Med Educ. 2020 May;54(5):456–457. doi: 10.1111/medu.14113

- Little A, Hampton Z, Gronowski T, et al. Podcasting in medicine: a review of the current content by specialty. Cureus [internet]. 2020 Jan 21 cited 2023 Aug 20. Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/26840-podcasting-in-medicine-a-review-of-the-current-content-by-specialty

- Rodman A, Trivedi S. Podcasting: a roadmap to the future of medical education. Semin Nephrol. 2020 May;40(3):279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2020.04.006

- Kelly JM, Perseghin A, Dow AW, et al. Learning through listening: a scoping review of podcast use in medical education. Acad Med. 2022 Jul;97(7):1079–1085. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004565

- Not Otherwise Specified [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://not-otherwise-specified-podcast.nejm.org

- Iorio S, Cilione M, Martini M, et al. Soft skills are hard skills—a historical perspective. Medicina (B Aires). 2022 Aug 3;58(8):1044. doi: 10.3390/medicina58081044

- Balakrishnan VAD-K. Augusta dejerine-klumpke. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Nov;17(11):936. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30141-8

- Romero C, Ventura S. Educational data mining and learning analytics: an updated survey. WIREs Data Min Knowl. 2020 May;10(3):e1355. doi: 10.1002/widm.1355

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing [internet]. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/

- Zhang E, Trad N, Corty R, et al. How podcasts teach: a comprehensive analysis of the didactic methods of the top hundred medical podcasts. Med Teach. 2022 Oct 3;44(10):1146–1150. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2071691

- Childers RE, Dattalo M, Christmas C. Podcast pearls in residency training. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Jan 7;160(1):70–71. doi: 10.7326/L14-5000-2

- Qian ET, Leverenz DL, Ja M, et al. An internal medicine residency podcast: impact on the educational experience and care practices of medical residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2021 May;36(5):1457–1459. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05939-3

- Cabrera D, Vartabedian BS, Spinner RJ, et al. More than likes and tweets: creating social media portfolios for academic promotion and tenure. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Aug 1;9(4):421–425. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00171.1

- Reid S. The ‘medical humanities’ in health sciences education in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2014 Feb;104(2):109–110. doi: 10.7196/samj.7928

- Erwin CJ. Development of a medical humanities and ethics certificate program in texas. J Med Humanit. 2014 Dec;35(4):389–403. doi: 10.1007/s10912-014-9306-4

- Dolev N, Naamati-Schneider L, Meirovich A. Making soft skills a part of the curriculum of healthcare studies, In: Firstenberg M S, Stawicki S P. editors. Medical Education for the 21st Century [Internet]. IntechOpen; 2022 cited 2023 Sep 18. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/77395

- Howick J, Zhao L, McKaig B, et al. Do medical schools teach medical humanities? Review of curricula in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom. Evaluation Clin Pract. 2022 Feb;28(1):86–92. doi: 10.1111/jep.13589

- Grant VJ. Making room for medical humanities. Med Humanities. 2002 Jun 1;28(1):45–48. doi: 10.1136/mh.28.1.45

- Agarwal A, Wong S, Sarfaty S, et al. Elective courses for medical students during the preclinical curriculum: a systematic review and evaluation. Med Educ Online. 2015 Jan;20(1):26615. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.26615

- Assing Hvidt E, Ulsø A, Thorngreen CV, et al. Weak inclusion of the medical humanities in medical education: a qualitative study among Danish medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2022 Sep 5;22(1):660. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03723-x

- Hoff G, Hirsch NJ, Means JJ, et al. A call to include medical humanities in the curriculum of colleges of osteopathic medicine and in applicant selection. J Osteopathic Med. 2014 Oct 1;114(10):798–804. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2014.154

- Chen L, Zhang J, Zhu Y, et al. Exploration and practice of humanistic education for medical students based on volunteerism. Med Educ Online. 2023 Dec 31;28(1):2182691. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2023.2182691

- Guraya SS, Guraya SY, Doubell FR, et al. Understanding medical professionalism using express team-based learning; a qualitative case-based study. Med Educ Online. 2023 Dec 31;28(1):2235793. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2023.2235793

- Andersson H, Svensson A, Frank C, et al. Ethics education to support ethical competence learning in healthcare: an integrative systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2022 Dec;23(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12910-022-00766-z

- Paton A, Kotzee B. The fundamental role of storytelling and practical wisdom in facilitating the ethics education of junior doctors. Health (London). 2021 Jul;25(4):417–433. doi: 10.1177/1363459319889102

- Hensel WA, Rasco TL. Storytelling as a method for teaching values and attitudes. Acad Med. 1992 Aug;67(8):500–504. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199208000-00003

- Thacker N, Wallis J, Winning J. ‘Capable of being in uncertainties’: applied medical humanities in undergraduate medical education. Med Humanities. 2022 Sep;48(3):325–334. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2020-012127

- Kagawa Y, Ishikawa H, Son D, et al. Using patient storytelling to improve medical students’ empathy in Japan: a pre-post study. BMC Med Educ. 2023 Jan 27;23(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04054-1

- Kanagasabai P, Ormandy J, Filoche S, et al. Can storytelling of women’s lived experience enhance empathy in medical students? A pilot intervention study. Med Teach. 2023 Aug 4:1–6. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2023.2243023

- Igartua JJ, Vega Casanova J. Identification with characters, elaboration, and counterarguing in entertainment-education interventions through audiovisual fiction. J Health Commun. 2016 Mar 3;21(3):293–300. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1064494

- Moyer-Gusé E, Nabi RL. Comparing the effects of entertainment and educational television programming on risky sexual behavior. Health Commun. 2011 Jul;26(5):416–426. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.552481

- Cosimini MJ, Cho D, Liley F, et al. Podcasting in medical education: how long should an educational podcast be? J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Jun 1;9(3):388–389. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00015.1

- Prakash SS, Muthuraman N, Anand R. Short-duration podcasts as a supplementary learning tool: perceptions of medical students and impact on assessment performance. BMC Med Educ. 2017 Dec;17(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1001-5

- Boscardin CK, Gin B, Golde PB, et al. ChatGPT and generative artificial intelligence for medical education: potential impact and opportunity. Acad Med. 2024 Jan;99(1):22–27. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005439

- Fahmi U, Wibowo CP, Yudanto F. Hybrid method in revealing facts behind texts: a combination of text mining and qualitative approach. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Conference of Asian Association for Public Administration: ‘Reinventing Public Administration in a Globalized World: a Non-Western Perspective’ (AAPA 2018) [Internet]; Yogyakarta (Indonesia): Atlantis Press; 2018 cited 2024 May 19. Available from: http://www.atlantis-press.com/php/paper-details.php?id=25896109

- Marcolin CB, Diniz EH, Becker JL, et al. Who knows it better? Reassessing human qualitative analysis with text mining. QROM. 2023 Jun 19;18(2):181–198. doi: 10.1108/QROM-07-2021-2173

- O’Mara-Eves A, Thomas J, McNaught J, et al. Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Syst Rev. 2015 Dec;4(1):5. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-5

- Atkinson-Clement C, Duflot M, Lastennet E, et al. How does Tourette syndrome impact adolescents’ daily living? A text mining study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. cited 2022 Dec 2 cited 2022 Dec 2;32(12):2623–2635. doi: 10.1007/s00787-022-02116-1

- Ferreira‐Mello R, André M, Pinheiro A, et al. Text mining in education. WIREs Data Min Knowl. 2019 Nov;9(6):e1332. doi: 10.1002/widm.1332

- Koedinger KR, D’Mello S, Ea M, et al. Data mining and education. WIREs Cogn Sci. 2015 Jul;6(4):333–353. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1350

- Lebowitz A, Kotani K, Matsuyama Y, et al. Using text mining to analyze reflective essays from Japanese medical students after rural community placement. BMC Med Educ. 2020 Dec;20(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-1951-x

- Liu W, Zhang Y, Wang T. Research on students’ satisfaction of intelligent learning based on text mining technology. Computational intelligence and neuroscience. 2022 Jun 22;2022:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2022/4024263.

- Bringula R, Ulfa S, Miranda JPP, et al. Text mining analysis on students’ expectations and anxieties towards data analytics course. Cogent Eng. 2022 Dec 31;9(1):2127469. doi: 10.1080/23311916.2022.2127469

- Föll P, Thiesse F. Exploring information systems curricula: a text mining approach. Bus Inf Syst Eng. 2021 Dec;63(6):711–732. doi: 10.1007/s12599-021-00702-2

- Araujo L, Lopez-Ostenero F, Martinez-Romo J, et al. Deep-learning approach to educational text mining and application to the analysis of topics’ difficulty. IEEE Access. 2020;8:218002–218014. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3042099

- Shaik T, Tao X, Dann C, et al. Sentiment analysis and opinion mining on educational data: a survey. Nat Language Processing J. 2023 Mar;2:100003. doi: 10.1016/j.nlp.2022.100003

- Chen B, Liu Y, Zheng J. Using data mining approach for student satisfaction with teaching quality in high vocation education. Frontiers In Psychology. 2022 Jan 20;12:746558. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746558

- Shikama Y, Chiba Y, Yasuda M, et al. The use of text mining to detect key shifts in Japanese first-year medical student professional identity formation through early exposure to non-healthcare hospital staff. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Dec;21(1):389. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02818-1

- Quitadamo P, Urbonas V, Papadopoulou A, et al. Do pediatricians apply the 2009 NASPGHAN–ESPGHAN guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux after being trained? J Pediatric Gastroenterol & Nutr. 2014 Sep;59(3):356–359. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000408