ABSTRACT

Community leadership in Arctic environmental research is increasingly recognized to contribute to Indigenous self-determination and sustainable development in the Arctic. While experienced Inuit harvesters, hunters, trappers, and other recognized environmental knowledge experts are largely included in research, similar opportunities for Inuit youth remain limited. Our study explored pathways for community-based engagement in environmental research to serve as a form of experiential learning for Inuit youth and enhance capacity in Arctic communities. For that, we examined, through interviews and workshops, the perspectives of 41 northerners from Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik), Nunavut, including 19 Inuit youth aged between 18 and 35 years old. We found that mentor-mentee relationships between researchers and Inuit youth may enhance scientific literacy and complement traditional learning pathways and observational learning. On the other side, by engaging Inuit youth, researchers may benefit from the experiences and knowledge of this new generation of northern Indigenous peoples uniquely positioned to value multiple worldviews in designing studies that address local priorities.

Introduction

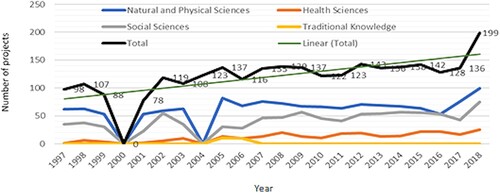

Each year, an increasing number of scientific research projects are conducted across the Nunavut Territory in northern Canada (). While researchers from southern Canada lead much of this research (Aurora Research Institute, Citation2017; Nunavut Research Institute, Citation2017; Nunavut Research Institute, Citation2018), greater involvement of Inuit in all aspects of research has been well documented (Bocking, Citation2007; Brunet et al., Citation2014a; Johnson et al., Citation2015; Nunavut Research Institute, Citation2018). This phenomenon has been associated with a strong push by Inuit organisations and research agencies, funders and southern-based researchers themselves to be more inclusive of northern Indigenous peoples in knowledge creation activities (Ferrazzi et al., Citation2018; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami & Nunavut Research Institute, Citation2007; Provencher et al., Citation2013).

Figure 1. Number of research permits issued under Nunavut’s Scientists Act by the Nunavut In-novation and Research Institute (NIRI) in Nunavut, Canada, by discipline per year for the 1997–2018 period. Data was obtained only from research compendia available from the NIRI. Data from 2000 were not available. Data may not be inclusive of wildlife and archaeological research.

Such an increase in local engagement can notably be attributed to the hiring of experienced Inuit harvesters, as they possess the resources and knowledge necessary to partake in environmental research (Brunet et al., Citation2014b; Thompson et al., Citation2020). However, opportunities for Inuit youth (young Inuit adults aged between 15 and 30 years old; more details in supplementary materials) to engage in similar research relationships remain limited (Henri, Brunet, et al., Citation2020; Provencher et al., Citation2013). One study conducted by Henri, Brunet, et al. (Citation2020) suggested that Inuit youth do not have the same opportunities to spend time on the land through research and interact with Inuit knowledge-holders from whom they would acquire land-based knowledge and skills relevant to research engagement. Henri, Brunet, et al. (Citation2020) further suggested that southern-based researchers may be able to facilitate opportunities for youth to make such connections. It has been found that, in general, youth are significantly less likely than older adults to be engaged in participatory research or become research partners (Jacquez et al., Citation2013; Nilsson et al., Citation2019). As 59% of the population of Nunavut is under the age of 30 (Statistics Canada, Citation2017a, Citation2017b), Nunavut youth could represent a significant portion of future researchers, conservation officers, and environmental managers who would benefit from research training. In addition, there is evidence that the formalized education system in Nunavut has impeded the transmission of traditional knowledge to Inuit youth, which is a valuable component of northern research (Lewthwaite & McMillan, Citation2007; McGregor, Citation2012; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Citation2015a). At the same time, many Inuit youth may still not be attaining the educational level expected to conduct independent environmental research. The systematic exclusion of Inuit youth from the research process results in missed opportunities to engage in knowledge transfer activities that could enhance community capacity for sustainable development in the Arctic.

The National Inuit Strategy on Research

The National Inuit Strategy on Research, released in 2018 by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, an organization that represents Inuit across the Canadian Arctic, identified capacity development as one of five priority areas for research conducted in Inuit Nunangat (Inuit homelands in Canada, including Nunatsiavut, Nunavik, Nunavut, and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region) (see supplementary materials for a broader definition of Inuit Nunangat). The Strategy highlights ways for research conducted in Inuit Nunangat to underpin Inuit self-determination. Further, it represents an important step toward ensuring that Inuit are included in research, that research and other knowledge-transfer activities align with Inuit priorities, and that benefits from research in Inuit Nunangat are maximized for Inuit communities and individuals. The long-term capacity needed for enhanced local decision-making and leadership may be found, at least in part, through collaborative participatory research (Danielsen et al., Citation2010; Snook et al., Citation2018; Wong et al., Citation2020), including Inuit youth engagement as a building block (Wilson et al., Citation2020). Greater Inuit participation in research is intended to extend greater control over the research process to Inuit communities, and is increasingly expected of researchers (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami & Nunavut Research Institute, Citation2007; Wilson et al., Citation2020). Additionally, effecting broad-scale changes to environmental policy, which may heavily impact local communities, has been found to occur mostly through ‘scientist executed monitoring’ (Danielsen et al., Citation2010). As such, there is a clear need to promote long-lasting, self-determined community development through participatory environmental research that engages Inuit youth.

Participatory research

Participatory research has been employed around the world as an important tool in applied development studies and resource management (Kouril et al., Citation2016), particularly in underrepresented communities and in the Global South. Although there is no singular definition of ‘participatory research’, it is generally agreed that, by its nature, participatory research necessitates that researchers partner with local stakeholders with the shared purpose of mobilizing locally-held and co-produced knowledge that is relevant for all groups involved, and which can serve to improve local capacity and livelihoods (Ashby, Citation2003; Openjuru et al., Citation2015). Participatory research is widely used because it enables local actors to voice their opinions and share their experiences with the expectation that it will ultimately contribute to programs that are meaningful to resource users and local communities (Ashby, Citation2003; Openjuru et al., Citation2015). Visiting researchers may choose to explore a community-based participatory approach as an avenue for engagement because it works to redistribute power in the research process (Flicker et al., Citation2008; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Citation2018; Jacquez et al., Citation2013).

Similarly, Lawrence (Citation2006) states that one of the main outcomes of participatory environmental research is that power can be shifted by those who make use of the findings. Environmental research tends to have limited influence on community-level decision-making when it is exclusionary of community-level participation (Danielsen et al., Citation2010). For these reasons, participatory research practices such as community-based monitoring (CBM), a common approach in Arctic environmental research, are particularly relevant to Inuit and to youth. In the context of Arctic research, the term ‘community-based monitoring’ is used to describe the participatory practices encouraged by communities, government agencies, monitoring networks, and academic institutions (Johnson et al., Citation2013). It is relevant for Inuit youth to be engaged in the research process as decisions made today about environmental resources, conservation, and science will affect them for many years to come (Nilsson et al., Citation2019). Inuit youth may not be aware of engagement opportunities and process if they are also not exposed to such things, even if they hold an interest in research partnerships and programs (Sadowsky et al., Citation2021).

Limited opportunities for Inuit youth

Despite increased attention paid to community engagement in participatory research, Jacquez et al. (Citation2013) report that youth are significantly less likely to be involved in these processes than older age groups, and are less likely to be targeted for results dissemination. In a review of 385 journal articles with youth community-based participatory research (CBPR) classifications, Jacquez et al. (Citation2013) found that a mere 15% represented research in which youth constituted the community research partners (which largely related to health and wellness). By contrast, Johnson et al. (Citation2016) found that greater youth representation in monitoring projects would enhance diversity in community-level research, and foster skills development and intergenerational transmission of Inuit knowledge. While youth do not often act as research partners, studies have shown that they can play an important role in project design (Jacquez et al., Citation2013; Reich et al., Citation2017), data collection (Wolfe et al., Citation2007), analyses (Ford et al., Citation2012), and results dissemination (Ford et al., Citation2012; Reich et al., Citation2017). Importantly, there may be a number of factors preventing Inuit youth from engaging in research, including a lack of interest in collaboration on the part of researchers or Inuit youth, a lack of mentorship and personal support for Inuit youth, linguistic and cultural barriers, and the precarious nature of research work, among others (Sadowsky et al., Citation2021).

Objectives

Our study explores pathways for community-based engagement in environmental research to serve as a form of experiential learning for Inuit youth and enhance capacity in Nunavut communities. This exploration is derived from a study conducted by the authors, which took place between 2018 and 2019 in Pond Inlet, Nunavut, examining the role of Inuit youth engagement in scientific research (Sadowsky, Citation2019). This new study links research findings and supporting literature to different ways that enhancing scientific literacy among Inuit youth through research engagement can contribute to human capital and community capacity as core components of sustainable development and Inuit self-determination in Nunavut, Canada.

Materials and methods

Between 2018 and 2019, we conducted a study in Pond Inlet, Nunavut, on the role of Inuit youth engagement in scientific research (Sadowsky, Citation2019; Sadowsky et al., Citation2021). The Hamlet of Pond Inlet has a population of approximately 1,600 people and is located at the north end of Baffin Island. According to the Hamlet’s census profile, 93% of residents identify as Inuit and approximately 63% of the population is under the age of 30 (Statistics Canada, Citation2017a). By contrast, population estimates show that only 35% of the population of Canada is under 30 years old (Statistics Canada, Citation2017b). The goal of this study was to advance pathways for Inuit youth to enhance their scientific literacy and engage in scientific literacy activities through environmental research. We worked directly with four community-based research assistants from Pond Inlet (co-authors Alexandra Anaviapik and Abraham Kublu; as well as Cara Killiktee and Jonathan Pitseolak), three of whom were youth, and all of whom provided ideas and reflections from their own personal, educational, and professional experiences in research (). We connected with the research assistants through Ikaarvik Barriers to Bridges (Ikaarvik). Ikaarvik is an Inuit youth research group that was founded in Pond Inlet, Nunavut, and is a laureate of the Arctic Inspiration Prize.

Figure 2. Pond Inlet youth, Lynn Angnatsiak and Cara Killiktee, discuss their research interest during a land-based workshop in 2018. Both agreed to have their photo included in this paper.

Our larger study had three objectives: (1) to uncover community perspectives of barriers to Inuit youth engagement and innovative engagement strategies that may be or are currently being undertaken by environmental researchers in Pond Inlet, Nunavut (see Sadowsky et al., Citation2021); (2) to develop an understanding of the process and outcomes of Inuit youth engagement in environmental research (see Sadowsky et al., Citation2021); and (3) to explore the role of environmental researchers in enhancing environmental scientific literacy among Inuit youth in Pond Inlet, Nunavut (this paper). In this paper, we focus on findings relating to the third objective as we reflect upon the lessons learned while engaging more generally in this project and spending time in the community, and ground those findings in relevant literature.

A total of 41 people (hereafter referred to as ‘contributors’) participated in the research, nearly half (46%) of whom were between the ages of 18 and 35. A total of 28 semi-structured, individual interviews were completed. Two workshops, Part One and Part Two, were also completed with a group of 16 contributors. The workshops were held on two different days with the same people, allowing for contributors to more fully develop ideas and to revisit the group’s discussion to ensure accuracy of findings (personal communication, Program Lead, Ikaarvik Barriers to Bridges, 26 March 2018). Interviews and workshops used prompting questions to discuss contributors’ experiences in environmental research being conducted in the community or nearby. Interview and workshop discussion themes associated with the third objective were focused on contributors’ experiences in research or with southern-based researchers, what they contributed to the process and what they gained from it, contributors’ overall learning outcomes, contributors’ satisfaction with their experiences, and what contributors thought the roles of southern-based researchers should be when working with Inuit youth. Community research assistants identified an initial group of contributors based on contributors’ familiarity with different areas of interest and expertise, and highlighted significant themes emerging within the research.

This project was reviewed by the Research Ethics Board, REB #18-06-018, for compliance with federal guidelines for research involving human participants. This project was also reviewed by the Nunavut Research Institute for research in the area of social sciences and traditional knowledge, Scientific Research License #02 066 18N-M. All contributors gave informed consent prior to participating in this study. For further details regarding our study, including methodology, information on the Hamlet of Pond Inlet, and findings for objectives (1) and (2), see Sadowsky et al. (Citation2021).

We described the term ‘scientific literacy’ to contributors as teaching and learning about science, scientific concepts, and the scientific process. Turner (Citation2008) describes scientific literacy as an ‘individual’s factual understanding of scientific information and principles’ (p. 57). In the context of our study, scientific literacy further represented a set of skills and knowledge that could complement Inuit processes of personal development and contribute to leadership in environmental research.

Results and discussion

Role of environmental researchers in enhancing scientific literacy among Inuit youth

Contributors unanimously agreed that southern-based researchers do have a role to play in enhancing scientific literacy among Inuit youth in Pond Inlet, despite concerns of supporting colonial processes. Many felt that southern-based researchers have the capacity and should exercise their capabilities to share knowledge with Inuit youth specifically about their research, as well as environmental science more generally. Similarly, a study conducted by Lewthwaite and McMillan (Citation2007) found that Nunavut communities have a strong interest in young people engaging with science, and for Inuit knowledge to be presented equally. Pearce et al. (Citation2011) highlighted that knowledge and skills transmission to Inuit youth are largely dependent on having access to a knowledgeable teacher-figure, usually a family member. While Inuit traditionally learned about the environment through land-based learning (see definition in supplementary materials) and experiences (Karetak et al., Citation2017; Pearce et al., Citation2011), in-town learning through opportunities to interview elders can also allow youth to acquire traditional knowledge (Wolfe et al., Citation2007). Wilson et al.’s (Citation2020) work with Sikumiut, based out of Pond Inlet, Nunavut, revealed that Elders in Pond Inlet identified a shortfall in opportunities for Inuit youth to learn from other community members through land-based experiences. In response, Sikumiut endeavored to create opportunities for Inuit youth to partner in sea-ice research with both Elders and researchers through a mapping project (Wilson et al., Citation2020). Similarly, through environmental research project in the Slave River Delta of the Northwest Territories, Wolfe et al. (Citation2007) illustrated that, in leveraging the involvement of community elders, youth gained time with knowledge-holders and acquired culturally and locally relevant environmental knowledge. Cruikshank (Citation2012) further explained that the recounting of information ‘provide[s] the conceptual ability to recreate, through language, situations for someone who has not experienced them directly’ (p. 247). While land-based learning holds educational and cultural significance for Inuit youth, contributors to our study remarked that making use of additional resources and modes of knowledge transmission, such as those offered through participatory environmental research, is of equal importance.

There is evidence to suggest that, given the opportunity to do so, youth find value in being involved in all aspects of the research process, including project design, data collection and analysis, as well as results dissemination (Ballard et al., Citation2017; Barab & Hay, Citation2001; Ford et al., Citation2012). Inclusion enhances the sense of value in one’s work by having meaningfully contributed to real-world projects (Ballard et al., Citation2017; Barab & Hay, Citation2001). As such, researchers may find that Inuit youth become increasingly interested in science as they broaden their knowledge base and skill sets, while making authentic contributions to projects. Contributors highlighted that partnerships with southern-based researchers were critical to supporting Inuit youth capacity building initiatives.

I’m sure there’s young people like that who I know are very willing, but if there’s nobody to teach them that like the researcher. Like you say, if you’re willing – maybe something they love doing – with their guidance, they could get more ideas or even the practical experience – that help from a professor or doctor like yourselves. Yeah. If you’re – as long as you’re willing to do, share that knowledge, it’s very helpful. (George Koonoo, Pond Inlet)

Outcomes of Inuit youth engagement in environmental research

First, contributors highlighted that engagement in university and government-led research programs could motivate Inuit youth to focus on particular subjects at school, typically relevant to careers in science. They explained that southern-based researchers could help Inuit youth find areas of study that were meaningful to them and that could be integrated into their school projects and activities, thus motivating students to stay in school longer.

Cause they could connect that with what they learned in school and what they’re doing hands on. That would be like a science experiment. (Amy Killiktee, Pond Inlet)

Second, contributors suggested that southern-based researchers could offer advice and insights regarding educational trajectories for Inuit youth who want to pursue more advanced studies on certain aspects of the environment and wildlife. One respondent highlighted the importance of education for Inuit youth, stating:

Nowadays it’s all about education. When you don’t have education, you don’t have a say […] Like, if you don’t have a good job, whatever you say is not going to be heard. But if you have a good job, and you say it, you are most definitely heard. (Research contributor, Pond Inlet)

Well, I try and keep young people in the loop within my research ‘cause I would like for them to know what I’m doing. And, there might be that one youth that is really keen and would be involved and I would be able to train him on how my operation works, and if I moved on then that youth can take over whatever I’m doing, essentially. (Andrew Arreak, Pond Inlet)

I think it’s very important because it would be a huge part of their future and they’re being trained [by southern-based researchers] on how to operate stuff, or with instruments that they use to collect data. And, yeah. It’s a really important role for youth to have those kinds of experiences because they can choose what they want to do in life. (Cara Killiktee, Pond Inlet)

In addition to knowledge transfer and mentorship, engagement in participatory research has resulted in other benefits for Inuit youth. For example, Brunet et al. (Citation2017) noted that while financial gains appear in the short term, longer-lasting gains in social and human capital often result from highly effective research partnerships. Though long-term partnerships may be compromised by the short-term and fragmented nature of academic and research funding and researcher turnover, long-lasting research engagement is relevant to the long-term wellbeing and sustainability of communities. It has also been suggested that knowledge mobilization (putting knowledge into use) may result from increased research capacity derived from the involvement of youth in environmental monitoring projects (Henri, Carter, et al., Citation2020; Jacquez et al., Citation2013; Johnson et al., Citation2013; Reis et al., Citation2015). Ballard et al.’s (Citation2017) study of two community and citizen science (CCS) programs with youth reported that those who spend more time working on projects may benefit more than those who had participated in short-term research programming. Students who ‘take up science and conservation knowledge, skills, roles, and actions’ are those with the longest and most in-depth experiences (Ballard et al., Citation2017., p. 74). This same study determined that many students foresaw a role for their future selves in conservation because of their level of involvement in research projects, further supporting the case for long-term, sustained engagement. Participatory environmental research grounded in land-based, locally acquired experiences has a high potential to motivate Inuit youth to partake in research and other resource management activities that are relevant to local priorities and interests.

School as barrier and opportunity for meaningful capacity enhancement

In our study, we found that researchers can play an important role in enhancing scientific literacy for Inuit youth. Importantly, though, southern-based researchers cannot replace existing learning resources, such as family members, Elders, and school personnel. Rather, we found that the research relationships with southern-based researchers may serve to complement existing knowledge transfer pathways for Inuit youth (see Sadowsky et al., Citation2021). While the Arctic Human Development Report (AHDR) notes that ‘[a]ll Arctic states are classified as developed countries’, the circumpolar North broadly experiences underdevelopment as described through several development indicators, notably education (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Citation2018; Larson & Fondahl, Citation2014, p. 54). Attainment gaps in formalized education are present in Nunavut when compared to educational attainment in southern Canada (Wong et al., Citation2020), indicating that many Inuit youth may be ill-prepared to carry out scientific research tasks without additional training. As academic and professional research typically requires higher levels of education and training, Inuit youth who cannot reach or access post-secondary instruction may have limited occasion to partake in research that addresses their priorities and interests.

Challenges in formalized education observed today across Inuit Nunangat have been tied back to the time of residential schools (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Citation2005). In Canada, residential schools operated between the early 1830s and late 1990s, and were established to acculturate Indigenous peoples across Canada and brought about the removal of Indigenous children from their homes and families (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Citation2015a; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Citation2015b). The socio-psychological impacts of residential schools have been carried forward intergenerationally (Qikiqtani Inuit Association, Citation2013). In addition, many Inuit did not fully learn their traditional skills and values due to this separation (McGregor, Citation2012), and there is evidence that traditional knowledge is not being passed on to Inuit youth today in its entirety. The formalized education system is also misaligned with traditional practices in the transmission of knowledge, which require being able to spend time on the land and interact with knowledgeable family and community members (Qikiqtani Inuit Association, Citation2013). There is ongoing concern that the formal education system both perpetuates colonial processes and practices and also fails to adapt sufficiently to meet Inuit’s needs (Kral et al., Citation2014; Lewthwaite & Renaud, Citation2009). As such, Inuit youth who are interested in research opportunities may not be equiped to conduct research without additional training and education. Our study revealed that Inuit youth may consequently be hesitant to actively pursue academic and research opportunities. Underlying reasons may include that academia and research can seem daunting, out of reach, or may conflict with traditional knowledge and traditional knowledge acquisition processes.

It’s just finding that commitment that you finish this in the long-run you’ve got something permanent for the next 30 years if you work – if you’re a young man – 30 years down the line. And you can be that person […] For some it’s really easy, and for some it’s really hard. Like I said, you’d better be committed. (Joshua Idlout, Pond Inlet)

Unlike western educational approaches, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) is acquired naturally over time and through observation, training, and experience in Inuit culture (Karetak et al., Citation2017; Pearce et al., Citation2011). IQ refers to Inuit traditional knowledge or ‘that which Inuit have always known to be true’ (Tagalik, Citation2009, p. 1), reflecting holistic Inuit worldviews and traditional culture (Lewthwaite & McMillan, Citation2007). Environmental education (education related to subsistence activities, as well as values and beliefs surrounding human-environment relationships), within this context, has traditionally been taught to children and young adults by older family members (Karetak et al., Citation2017; Pearce et al., Citation2011). While this process of knowledge transfer still exists, the implementation of formal schools has meant that environmental education has become dominated by science curricula (Reis et al., Citation2015). Lewthwaite and Renaud (Citation2009) assert that the colonial process has actively suppressed Inuit knowledge and the development of a meaningful education curriculum. However, reciprocal collaboration between Inuit youth and southern-based researchers may serve to supplement or complement certain education areas, such as physical science and environmental studies, through land-based research opportunities.

Inuit youth, land-based learning and human capital development

The differing views on the functionality and adequacy of western and traditional education beg the question of how Inuit youth involvement in environmental research might complement current environmental learning pathways. There is consensus that culturally relevant education is needed (Lewthwaite & McMillan, Citation2007; McGregor, Citation2012; Oskineegish, Citation2015), and evidence suggests that place-based learning can reinforce educational content for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students alike (Ballard et al., Citation2017; Reis et al., Citation2015). Ballard et al.’s (Citation2017) study of youth engaged in CCS revealed that they were more likely to feel connected to their science programs if they already had a connection to the physical environment where their science programs were taking place. Furthermore, youth who participated in scientific projects that were grounded in their own environmental context were more likely to be drawn to long-term stewardship (Ballard et al., Citation2017). Our study findings echo this sentiment with contributors reporting that Inuit youth would be more heavily invested than southern-based researchers in local long-term, high-quality research as Inuit youth have a vested interest in their own surrounding environment.

I think young people being involved in environmental research is very important because this is where they grew up and this is where they’ll become Elders. Not everybody will leave the community to further […] their education – not a lot of people has gone and done that, but to kind of move and, I mean, in a smaller community that’s the majority of the people stay in the community. So, I think they should have that knowledge too of environmental research. It’s their community, and it’s what they know. Get them involved, and I think it’s very important that it is taught in the community. (Rebecca Killiktee, Pond Inlet)

Additionally, participation in traditional activities is also seen as a contributor to developing human capital at both individual and community levels. In particular, links have been found between human capital, community resilience, and positive community development outcomes (Larson & Fondahl, Citation2014). Human capital is understood to be the knowledge base of an individual or community that can contribute to economic gain or has economic value (Lévesque & Duhaime, Citation2016). As defined in the AHDR, human capital is composed of ‘general skills (literacy), specific skills (related to particulate technologies and operations), and technical and scientific knowledge (mastery of specific bodies of knowledge at advanced levels)’ (Larson & Fondahl, Citation2014, p. 366). While it is understood that formal education contributes significantly to an individual’s ability to earn a high income (Lévesque & Duhaime, Citation2016), definitions of human capital recognize that what is deemed to be ‘informal’ knowledge and skills can be equally important contributors to livelihoods, particularly in subsistence communities and cultures. Within this broad definition of human capital, there is room to re-evaluate educational goals to be more inclusive of culturally relevant knowledge (Larson & Fondahl, Citation2014), for example, that which is increasingly found in CBM and collaborative research. This is of particular relevance in Arctic regions where formalized educational systems are thought to be less robust and where there is a higher value placed on land-based skills and traditional knowledge (Larson & Fondahl, Citation2014). The AHDR further adds that there is ‘difficulty of quantifying the value’ of knowledge and skills acquired through informal learning, though these aspects of human capital should not be undervalued (Larson & Fondahl, Citation2014, p. 366). In Nunavut, increased applications of participatory research with Inuit youth may facilitate the building of human capital through greater scientific literacy, and the advancement of self-determined, sustainable local development initiatives supported by both scientific and traditional knowledge.

Opportunities for knowledge co-creation with Inuit youth

Inuit possess a wealth of knowledge and experience in monitoring Arctic ecosystems, and have voiced strong interests in scientific studies that are conducted within Inuit Nunangat (Johnson et al., Citation2015). However, Indigenous academics such as Shawn Wilson (Citation2008), Michael Hart (Citation2010), and Pitseolak Pfeifer (Citation2018) have found that adequate representations of Indigenous perspectives and voices have largely been absent from research conducted in Indigenous communities in general, and that Eurocentric biases are persistent. It has been asserted that researchers do not yet universally grasp the value of traditional knowledge, putting participatory processes at risk (Pfeifer, Citation2018; Tengo et al., Citation2017; Wong et al., Citation2020). While Inuit forms of research (i.e. environmental monitoring and observing) may not inherently conform with the scientific process, Inuit have long monitored their environment as part of harvesting, subsistence, and safety practices (Johnson et al., Citation2013). IQ represents an extensive body of knowledge that Inuit have developed about the environment they have lived in and are a part of (Johnson et al., Citation2013; Kouril et al., Citation2016). Johnson et al. (Citation2013) point out that these practices are themselves forms of data collection, despite ongoing push back from the scientific community where environmental observations made by Indigenous peoples are still seen by some researchers as anecdotal.

In a step toward valuing multiple ways of knowing and knowledge co-production, Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall coined the term ‘two-eyed seeing’, describing the involvement of Indigenous peoples, including youth, in research as facilitators in the interweaving of Indigenous knowledge and Western science (Bartlett et al., Citation2012). Similarly, Ikaarvik developed a concept of ‘ScIQ’, which is described as a ‘functional middle ground between science and IQ’ (Pedersen et al., Citation2020). Relationships in research create opportunities for collaboration and encourage researchers to invest in processes and practices that will result in knowledge co-production, resource co-management, and benefit-sharing (Johnson et al., Citation2016). One of these benefits may be to create opportunities for Inuit youth to form learning relationships with both southern researchers and other knowledgeable community members. It is thought that opportunities for Inuit youth in Arctic environmental research will encourage young people to take on greater roles in environmental studies and research (Provencher et al., Citation2013). An enhanced space for Inuit youth in research could, in turn, contribute to Inuit environmental leadership and self-determination as supporting aspects of local development. As with other Indigenous youth, Inuit sit at the pinnacle of two-eyed seeing and ScIQ, and are uniquely positioned to employ IQ and western scientific knowledge to advance environmental research and community development that is meaningful in Nunavut. In addition, increased Inuit youth engagement would fortify the potential to continue generating research paradigms that may minimize concerns over the validity of traditional monitoring and conservation practices while still meeting academic criteria. Inuit youth engagement in environmental studies may point to new research landscapes where Inuit increasingly take on or create research that reflects local science and development priorities, and may influence broader changes in the way that research is approached overall in the Arctic. In a position paper by Ikaarvik on ScIQ, Aaluk et al. (Citation2019) state:

Capacity-building in northern Indigenous communities is, after all, more than simply training locals to assist with research that was developed, designed and planned in the South. Building capacity in Indigenous communities in this context should lead to, among other things, improved self-determination, access to information required to effectively respond to development and climate change pressures, and the skills, knowledge and confidence to work as true partners with the broader research community to address local research priorities. (p. 1)

Conclusion

Arctic science can, under the right circumstances, enhance Inuit youth capacity to participate in, design and lead a made in the North research agenda while simultaneously facilitating local development. Strong research partnerships can contribute to forging the knowledge, experiences, and relationships that Inuit youth need to play leading roles in the sustainability of Arctic communities. Specifically, mentor-mentee relationships between researchers and Inuit youth may prove to have significant impacts on scientific literacy, an important contributor to human capital development. Such collaborative relationships involving Inuit youth may also enhance partnered research by ensuring greater focus on community research priorities and knowledge transfer objectives, among other procedural elements. By engaging Inuit youth, researchers can benefit from the experiences and knowledge of this new generation of northern Indigenous peoples uniquely positioned to value multiple worldviews in designing studies that address local priorities.

Our study suggests that researchers can play a role in meaningful youth knowledge transfer activities in Arctic communities by complementing traditional learning pathways and observational learning. Knowing the extent and the specific circumstances leading community-based environmental research to beneficial impacts on Inuit youth capacity are still unclear however, pointing to future research needs. In particular, measuring human capital development or changes within an individuals’ diverse knowledge, skills, and experiences has been found to be highly complex in our own work and the broader literature in the field.

It is also important to consider that investment in youth science literacy as part of a community-engaged research process holds some risks. For instance, non-Indigenous researchers need to be conscious of the role they could potentially play in furthering colonial processes by acting as educators in Inuit communities, a role they were not typically trained for. Further, western conceptualizations of sustainable development may also be at odds with Indigenous worldviews regarding relationships with the land and responsibilities to future generations, as well as the more directly relevant and stated goal of Indigenous self-determination. A certain degree of caution must therefore be applied when drawing lessons at the intersection of research practice, Indigenous youth capacity development, and sustainable development.

Acknowledgements

The authors owe many thanks to the Hamlet of Pond Inlet, the Mittimatalik Hunters and Trappers Organization, the Nunavut Arctic College, Ikaarvik Barriers to Bridges (Shelly Elverum in particular), and all the individuals who gave their time and energy to this research on the ground. We would especially like to thank the people listed below, as well as those who wish to remain anonymous, who informed this research through their participation, mentorship, partnership, and many insightful conversations: James Akpaleepik, Jayko Alooloo, Lynn Angnatsiak, Tyson Angnatsiak, Andrew Arreak, Jonas Arreak, Kenneth Arreak, Trevor Bell, Carey Elverum, Shelly, Elverum, Joshua, Idlout, Mary Ipeelie, Andrew Jaworenko, Josh Jones, Gary Kalluk, Rhoda Katsyak, Amy Killiktee, Rebecca Killiktee, George Koonoo, James Kunuk, Shawn Marriot, Chris Merkosak, Ernest Merkosak, Jeanie Mills, Karen Nutarak, Christine Ootova, Elijah Panipakoocho, Noni J. Pewatouluk, Eleanor Pitseolak, Jonathan Pitseolak, Lousi-Philip Pothier, Terry Quarak, Evan Richardson, James Simonee, Sheati Tagak, Katherine Wilson. Thank you to Laura-Maria Martinez-Levasseur for technical support and manuscript formatting. We are grateful to Evan Richardson and the Pond Inlet research station team for project support. We thank Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) for allowing our team to stay and work at the ECCC Pond Inlet research station over the course of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaluk, T., Anaviapik, A., Koonoo, I., & Tiriraniaq, B. (2019). Ikaarvik position paper on meaningful engagement of northern Indigenous communities in research. Submitted for the National Dialogue on Strengthening Indigenous Research Capacity February, 12, 2019.

- Almers, E. (2013). Pathways to action competence for sustainability—six themes. The Journal of Environmental Education, 44(2), 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2012.719939

- Ashby, J. A. (2003). Introduction: Uniting science and participation in the process of innovation – research for development. In B. Pound, S. S. Snapp, C. McDougall & A. R. Braun (eds.), Managing natural resources for sustainable livelihoods: Uniting science and participation (pp. 1–19). Earthscan.

- Aurora Research Institute. (2017). Compendium of research in the Northwest Territories. https://nwtresearch.com/research/publications-and-reports/compendia-research

- Ballard, H. L., Dixon, C. G. H., & Harris, E. M. (2017). Youth-focused citizen science: Examining the role of environmental science learning and agency for conservation. Biological Conservation, 208, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.024

- Barab, S. A., & Hay, K. E. (2001). Doing science at the elbows of experts: Issues related to the science apprenticeship camp. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(1), 70–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2736(200101)38:1<70::AID-TEA5>3.0.CO;2-L

- Barron, B. (2006). Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective. Human Development, 49(4), 193–224. https://doi.org/10.1159/000094368

- Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., & Marshall, A. (2012). Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

- Bocking, S. (2007, October 4). Science and spaces in the northern environment. Environmental History, 12, 867–894. https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/12.4.867

- Brunet, N. D., Hickey, G. M., & Humphries, M. M. (2014a). The evolution of local participation and the mode of knowledge production in Arctic research. Ecology and Society, 19(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06641-190269

- Brunet, N. D., Hickey, G. M., & Humphries, M. M. (2014b). Understanding community-researcher partnerships in the natural sciences: A case study from the Arctic. Journal of Rural Studies, 36, 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.09.001

- Brunet, N. D., Hickey, G. M., & Humphries, M. M. (2017). How can research partnerships better support local development? Stakeholder perceptions on an approach to understanding research partnership outcomes in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Record, 53(5), 479–488. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247417000407

- Burgin, S. R., McConnell, W. J., & Flowers, A. M. (2015). ‘I actually contributed to their research’: The influence of an abbreviated summer apprenticeship program in science and engineering for diverse high-school learners. International Journal of Science Education, 37(3), 411–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2014.989292

- Cruikshank, J. (2012). Are glaciers ‘good to think with’? Recognising Indigenous environmental knowledge. Anthropological Forum, 22(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2012.707972

- Danielsen, F., Burgess, N. D., Jensen, P. M., & Pirhofer-Walzl, K. (2010). Environmental monitoring: The scale and speed of implementation varies according to the degree of peoples involvement. Journal of Applied Ecology, 47(6), 1166–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01874.x

- Doering, A., & Henrickson, J. (2014). Designing for learning engagement in remote communities: Narratives from north of sixty/Concevoir pour favoriser la participation active à l’apprentissage dans les communautés éloignées : récits d’Au nord du soixantième parallèle. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology / La Revue Canadienne de l’apprentissage et de La Technologie, 40(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.21432/T2WC7H

- Ferrazzi, P., Christie, P., Jalovcic, D., & Tagalik, S. (2018). Reciprocal Inuit and western research training: Facilitating research capacity and community agency in Arctic research partnerships. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 77(00), 1425581. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2018.1425581

- Flicker, S., Savan, B., McMcgrath, M., Kolenda, B., & Mildenberger, M. (2008). ‘If you could change one thing … ’ What community-based researchers wish they could have done differently. Community Development Journal, 43(2), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsm009

- Ford, T., Rasmus, S., & Allen, J. (2012). Being useful: Achieving indigenous youth involvement in a community-based participatory research project in Alaska. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 71(1), 18413–18417. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18413

- Garakani, T. (2014). The study of youth resilience across cultures: Lessons from a pilot study of measurement development. Research in Human Development, 5(1), 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427600802274019

- Hart, M. A. (2010). Indigenous worldviews, knowledge, and research: The development of an Indigenous research paradigm. Journal of Indigenous Voices in Social Work, 1(1), 1–16. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/15117

- Hecht, M., Knutson, K., & Crowley, K. (2019). Becoming a naturalist: Interest development across the learning ecology. Science Education, 103(3), 691–713. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21503

- Henri, D. A., Brunet, N. D., Dort, H., Hambly Odame, H., Shirley, J., & Gilchrist, H. G. (2020). What is effective research communication? Towards cooperative inquiry with Inuit Nunangat communities. Arctic, 73(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic70000.

- Henri, D. A., Carter, N. A., Nipisar, S., Emiktaut, L., Irkok, A., Saviakjuk, B., Salliq Project Management Committee, Arviat Project Management Committee, Ljubicic, G. J., Smith, P. A., & Johnston, V. (2020). Qanuq ukua kanguit sunialiqpitigu?(what should we do with all of these geese?) collaborative research to support wildlife co-management and Inuit self-determination. Arctic Science, 6(3), 173–207. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2019-0015

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2005). State of Inuit learning in Canada. Ottawa.

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2018). National Inuit strategy on research. Ottawa. 44p. https://www.itk.ca/national-strategy-on-research-launched/

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, & Nunavut Research Institute. (2007). Negotiating research relationships with Inuit communities: A guide for researchers (S. Nickels, J. Shirley, & G. J. Laidler, Eds.). Inuit Tapirit Kanatami and Nunavut Research Institute. 38 p. https://www.itk.ca/negotiating-research-relationships-guide/

- Jacquez, F., Vaughn, L. M., & Wagner, E. (2013). Youth as partners, participants or passive recipients: A review of children and adolescents in community-based participatory research (CBPR). American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1–2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9533-7

- Johnson, N., Alessa, L., Behe, C., Danielsen, F., Gearheard, S., Gofman-Wallingford, V., Kliskey, A., Krümmel, E.-M., Lynch, A., Mustonen, T., Pulsifer, P., & Svoboda, M. (2015). The contributions of community-based monitoring and traditional knowledge to Arctic observing networks: Reflections on the state of the field. Arctic, 68(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4447

- Johnson, N., Alessa, L., Gearheard, S., Gofman, V., Kliskey, A., Pulsifer, P., & Svodoba, M. (2013). Strengthening community-based monitoring in the Arctic: Key challenges and opportunities. http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/10.1139/er-2015-0041.

- Johnson, N., Behe, C., Danielsen, F., Krümmel, E. M., Nickels, S., & Pulsifer, P. (2016). Community-based monitoring and indigenous knowledge in a changing Arctic: A review for the sustaining Arctic observing networks, 1(1), 62. http://iccalaska.org/wp-icc/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Community-Based-Monitoring-and-Indigenous-Knowledge-in-a-Changing-Arctic_web.pdf%0Ahttp://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/community-based-monitoring.html

- Karetak, J., Tester, F., & Tagalik, S. (Eds.). (2017). Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: what Inuit have always known to be true. Fernwood Publishing.

- Kouril, D., Furgal, C., & Whillans, T. (2016). Trends and key elements in community-based monitoring: A systematic review of the literature with an emphasis on Arctic and Subarctic regions. Environmental Reviews, 24(2), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2015-0041

- Kral, M. J., Salusky, I., Inuksuk, P., Angitimarik, L., & Tulugardjuk, N. (2014). Tunngajuq: Stress and resilience among Inuit youth in Nunavut, Canada. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(5), 673–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461514533001

- Larson, J. N., & Fondahl, G. (Eds.). (2014). Arctic human development report: Regional processes and global linkages. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- sLawrence, A. (2006). ‘No personal motive?’ volunteers, biodiversity, and the false dichotomies of participation. Ethics, Place & Environment, 9(3), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668790600893319

- Lévesque, S., & Duhaime, G. (2016). Inequality and social processes in Inuit Nunangat. The Polar Journal, 6(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2016.1173795

- Lewthwaite, B., & McMillan, B. (2007). Combining the views of both worlds: Perceived constraints and contributors to achieving aspirations for science education in qikiqtani. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 7(4), 355–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/14926150709556740

- Lewthwaite, B., & Renaud, R. (2009). Pilimmaksarniq: Working together for the common good in science curriculum development and delivery in Nunavut. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 9(3), 154–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/14926150903118334

- McGregor, H. E. (2012). Inuit education and schools in the Eastern Arctic. UBC Press.

- Nilsson, A. E., Casron, M., Cost, D. S., Forbes, B. C., Haavisto, R., Karlsdottir, A., Nymand Larsen, J., Paasche, Ø, Sarkki, S., Vammen Larsen, S., & Pelyasov, A. (2019). Towards improved participatory scenario methodologies in the Arctic. Polar Geography, 44(2), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1648583

- Nunavut Research Institute. (2017). 2017 compendium of Nunavut research 2017 ᓄᐊᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᓂᑦ ᓄᓇᕗᒻᒥᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᕈᑎᕕᓂᖕᓂᑦ. https://www.nri.nu.ca/research-compendiums

- Nunavut Research Institute. (2018). 2018 Compendium of Nunavut research 2018 ᓄᐊᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᓂᑦ ᓄᓇᕗᒻᒥᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᕈᑎᕕᓂᖕᓂᑦ. https://www.nri.nu.ca/research-compendiums

- Openjuru, G., Jaitli, N., Tandon, R., & Hall, B. (2015). Despite knowledge democracy and community-based participatory action research: Voices from the global south and excluded north still missing. Action Research, 13(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750315583316

- Oskineegish, M. (2015). Are you providing an education that is worth caring about? Advice to non-native teachers in northern first nations communities. Canadian Journal of Education, 38(3), 1–15. https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/1770

- Pearce, T., Wright, H., Notaina, R., Kudlak, A., Smit, B., Ford, J., & Furgal, C. (2011). Transmission of environmental knowledge and land skills among Inuit men in Ulukhaktok, Northwest Territories, Canada. Human Ecology, 39(3), 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-011-9403-1

- Pedersen, C., Otokiak, M., Koonoo, I., Milton, J., Maktar, E., Anaviapik, A., Milton, M., Porter, G., Scott, A., Newman, C., Porter, C., Aaluk, T., Tiriraniaq, B., Pedersen, A., Riffi, M., Solomon, E., & Elverum, S. (2020). ScIQ: An invitation and recommendations to combine science and Inuit qaujimajatuqangit for meaningful engagement of Inuit communities in research. Arctic Science, 6(3), 326–339. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/full/10.1139/as-2019-0021. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2020-0015

- Pfeifer, P. (2018). An Inuit critique of Canadian Arctic research. Northern Public Affairs. https://www.arcticfocus.org/stories/inuit-critique-canadian-arctic-research/.

- Provencher, J. F., McEwan, M., Mallory, M. L., Braune, B. M., Carpenter, J., Harms, J. N., Savard G., & Gilchrist, H. G. (2013). How wildlife research can be used to promote wider community participation in the north. Arctic, 66(2), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4302

- Qikiqtani Inuit Association. (2013). Qikiqtani truth commission thematic reports and special studies 1950-1975: Illinniarniq Schooling in Qikiqtaaluk.

- Reich, J., Liebenberg, L., Denny, M., Battiste, H., Bernard, A., Christmas, K., Dennis, R., Denny, D., Knockwood, I., Nicholas, R., & Paul, H. (2017). In this together: Relational accountability and meaningful research and dissemination with youth. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917717345.

- Reis, G., Ng-A-Fook, N., & Glithero, L. (2015). Ecojustice, citizen science and youth activism beyond the school curriculum (chapter 4). In M. Mueller & D. Tippins (eds.), Environmental discourses in science education (vol. 1, pp. 39–61). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11608-2.

- Sadowsky, H. (2019). Understanding the role of Inuit youth engagement in scientific research in Nunavut [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Guelph. https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/handle/10214/17611.

- Sadowsky, H., Henri, D. A., Anaviapik, A., Kublu, A., Killiktee, C., & Brunet, N. D. (2021). Inuit youth and environmental research: Exploring engagement barriers, strategies, and impacts. FACETS, 7(1), 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0035.

- Snook, J., Cunsolo, A., & Dale, A. (2018, July). Co-management led research and sharing space on the pathway to Inuit self-determination in research. Northern Public Affairs, 52–56.

- Statistics Canada. (2017a). Census profile, 2016 census: Pond Inlet, HAM [Census subdivision], Nunavut and Nunavut [Territory] (table). Census Profile. 2016 [online]. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released November 29, 2017. Government of Canada. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?B1=All&Code1=6204020&Code2=62&Data=Count&Geo1=CSD&Geo2=PR&Lang=E&SearchPR=01&SearchText=Pond+Inlet&SearchType=Begins&TABID=1

- Statistics Canada. (2017b). Nunavut [Territory] and Canada [Country] (table). Census Profile. 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Released November 29, 2017. Government of Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=62&Geo2=&Code2=&SearchText=Nunavut&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=62&type=0

- Tagalik, S. (2009). Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: The role of Indigenous knowledge in supporting wellness in Inuit communities in Nunavut, 1–8. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/health/FS-InuitQaujimajatuqangitWellnessNunavut-Tagalik-EN.pdf

- Tengo, M., Hill, R., Malmer, P., Raymond, C. M., Spierenburg, M., Danielsen, F., Elmqvist, T., & Folke, C. (2017). Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond—lessons learned for sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26-27, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.005

- Thompson, K.-L., Lantz, T. C., & Ban, N. C. (2020). A review of Indigenous knowledge and participation in environmental monitoring. Ecology and Society, 25(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11503-250210

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015a). Canada’s residential schools: Reconciliation. In The final report of the truth and reconciliation commission of Canada (Vol. 6). www.trc.ca

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015b). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. www.trc.ca

- Turner, S. (2008). School science and its controversies; Or, whatever happened to scientific literacy? Public Understanding of Science, 17(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662507075649

- Wilson, K., Bell, T., Arreak, A., Koonoo, B., Angnatsiak, D., & Ljubicic, G. J. (2020). Changing the role of non-Indigenous research partners in practice to support Inuit self-determination in research. Arctic Science, 6(3), 127–153. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2019-0021

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing. 144p.

- Wolfe, B. B., Armitage, D., Wesche, S., Brock, B. E., Sokal, M. A., Clogg-Wright, K. P., Mongeon, C. L., Adam, M. E., Hall, R. I., & Edwards, T. W. D. (2007). From isotopes to TK interviews: Towards interdisciplinary research in fort resolution and the Slave rover Delta Northwest territories. Arctic, 60(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic267.

- Wong, C., Ballegooyen, K., Ignace, L., Johnson, M. J. (G.), & Swanson, H. (2020). Towards reconciliation: 10 calls to action to natural scientists working in Canada. FACETS, 5(1), 769–783. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2020-0005