Abstract

This article reviews our shared experience as two minoritized graduate students, encapsulating what the barriers we encountered were, and identifies the impacts of a personal disinterest by geoscientists and institutional disinvestment in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) issues in the geosciences. Specifically, in this article we advance the concept of disinvestment in the academy, and how disinvestment and disinterest reveal themselves in the ways the geosciences as a field interact with service and outreach to impact the abilities of minoritized geoscientists to create and sustain diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. Through evaluating the case of our creation of a geosciences camp for problems with disinvestment and disinterest by the academy, we identify barriers we faced and solutions created to address them through the framework of navigating a road, and typologizing them as roadblocks, detours, and alternate routes. The multiple barriers we experienced cumulatively amount to considerable time and effort lost, resulting in harm against us and our careers. We find the disinterest and disinvestment we experienced disincentivizes service and outreach work that is pivotal in improving DEI in geosciences. Our current systems and expectations need modification so we can move away from disinvestment and create engaged support structures.

Introduction

How does disinterest and disinvestment reveal itself in the ways the geosciences interact with service and outreach? In this article, we advance the concept of “disinvestment” as proposed by Jones (Citation2021) in the geosciences regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Here, disinvestment is defined as a lack of interest from the university environment and is situated within complex dimensions regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion that is characterized below. First, it results in historically marginalized scholars taking on the brunt of service and outreach work (Gewin, Citation2020), all while balancing their research and career progression in their field. The time they commit to DEI efforts results in time lost to learn and improve academic skills, conduct research, analyze data, and write and publish papers. Still, unlike their white, majoritized peers, this kind of service is crucial to the safety and progression of minoritized scholars. In high-ranking institutions, minoritized scholars are more likely to face disincentives (Ali & Prasad, Citation2021), which include their tokenization, lack of mentorship, lack of belonging, isolation, and undervaluing of their thoughts, ideas and contributions (Levine et al., Citation2021). As noted by Faria et al., Citation2019, structural racisms create unsafe environments including those that silence, dismiss, deny, and exclude minoritized geoscientists. To survive within these unsafe spaces, minoritized geoscientists must perform the extra and significant labor to fit in so they will not be ostracized (Faria et al., Citation2019). Creating safe spaces in their respective fields through conducting service and outreach with the goal of diversifying the geosciences thus becomes a mechanism of personal survival. Since there is no incentive or metrics to evaluate and value service and outreach in geosciences (Armani et al., Citation2021), white majoritized scholars who do not face the same disincentives have no reason to pursue these efforts because their personal disinterest is incentivized when they use that extra time and effort to pursue actions that are valued toward their career progression.

This article reviews our shared experience as two minoritized graduate students who pursued the building of a geosciences camp to expand and broaden participation in geosciences. We encapsulate the barriers we encountered and identify the impacts of a disinvestment within the geosciences regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion issues. We show how institutional disinvestment enables unsupported and under-resourced environments for minoritized scholars, especially when they pursue diversity, equity, and inclusion work. This article then explains the effects these impacts have on the field and provides recommendations for moving forward to help address the institutional disinvestment of service and outreach by those universities who subscribe to participating in the whiteness project of the geosciences.

Literature review

Diversity and inclusion in the geosciences

Recent research on the demographics of the geosciences shows that this discipline, which has long been historically white and dominated by cisgendered men, remains the least diverse of all the sciences (Bernard & Cooperdock, Citation2018; Huntoon & Lane, Citation2007). This lack of diversity is not from a complete lack of effort – a number of recommendations, strategies, potential solutions, and discussions already exist to address race and ethnicity issues, yet change has been slow to nonexistent in occurrence (Faria et al., Citation2019). Many reasons have been proposed for this lack of changes, most fervently being the “leaky pipeline” and an examination and dissection of its many parts and potential loci of leaks (Dutt et al., Citation2016; Hallar et al., Citation2010; Holmes, Citation2015; Huntoon & Lane, Citation2007; Levine et al., Citation2007; McEntee, Citation2019; Williams et al., Citation2007). When examining the research, there is also a clearer, longer focus on men/women gender parity, failing to use an intersectional approach regarding race and ethnicity and LGBTQIA + identities. When there is more diversity in a department, besides being a more accurate representation of the diverse population, departments are found to be more open, accepting, and supportive of a variety of groups, including racial and ethnic groups, and those who are LGTBQIA+, and perhaps those who have disabilities (Dutt, Citation2019; Yoder & Mattheis, Citation2016). While this is a common argument to increase diversity and inclusion in the geosciences, after decades of the same reasons being discussed time and time again, there begs the question: Why hasn’t this ample research about the importance of diversity and inclusion in the geosciences led to action? As academics we need to understand and evaluate our privilege to discuss issues at length before taking action. However, action is required with immediacy regarding racism and social justice in the geosciences. Without action, research in the geosciences will continue to suffer in quality and many people deserving of a place in the geosciences and academia at-large will continue to be lost.

It’s important to note that the pipeline did not spring, leaks and all, from nowhere. These are underrepresented and minoritized groups because of purposeful exclusionary practices. The practices are wide-ranging, from outright racist and sexist policies excluding minoritized groups, to the “old boys” club that prevents the dominant group from recruiting and mentoring future geoscientists of underrepresented backgrounds, and more (Dutt, Citation2010; Dutt et al., Citation2016; Holmes, Citation2015; Kaplan & Mapes, Citation2016; Núñez et al., Citation2020). So, the pipeline itself may be poorly constructed, but the connecting structures deserve examination as well. A review of this literature includes identifying the problem, solutions and strategies.

There are several models for analyzing the geosciences pipelines and their “leaks” (Estaville et al., Citation2006a; Levine et al., Citation2007). The stages of the pipeline broadly include recruitment, retention, and placement, and each has their areas of failures.

A number of barriers to recruitment exist, but especially for minoritized groups, they have been identified as a lack of understanding, knowledge, and interest in the geosciences from these groups, leading to low enrollment at the college level. With recruitment, numerous programs show that outreach throughout the precollege levels generates interest amongst students for pursuing the geosciences (Estaville et al., Citation2006a; Huntoon & Lane, Citation2007; Oludurotimi et al., Citation2012; Stokes et al., Citation2007; Velasco & De Velasco, Citation2010; Wechsler et al., Citation2005). Parents of these groups are concerned that the field is not viable for successful careers, students are interested in sciences they know can allow them to perform service back to the community, and teachers and schools in K–12 lack knowledge, coursework, and relevant technology to expose students to the geosciences in the first place (Bednarz, Citation2016; Estaville et al., Citation2006a; Levine et al., Citation2007; Marín-Spiotta et al., Citation2020; O’Connell & Holmes, Citation2011; Sherman-Morris et al., Citation2013). Successful programs offer activities, speakers, and displays to share with students, parents, and educators the value of the geosciences, foster interest, and answer questions to the viability of the geosciences as a career. Further, they draw on the interest for careers that serve altruistic goals, which students of all backgrounds rate highly on importance (Carter et al., Citation2021).When working to raise the profile of geosciences amongst educators and society generally, geosciences outreach with educators is crucial (Bednarz, Citation2016; Estaville et al., Citation2006a; Citation2006b; Huntoon & Lane, Citation2007; Sherman-Morris et al., Citation2013; Stokes et al., Citation2007; Wechsler et al., Citation2005). Providing mentors, financial assistance, and dedicated programs for minoritized groups successfully assists in recruitment and retention (Bernard & Cooperdock, Citation2018; Hernandez et al., Citation2018; Holmes & O’Connell, Citation2015; Kaplan & Mapes, Citation2016; Lozier & Clem, Citation2015; Williams et al., Citation2007). Building these programs through intentional institutional partnerships increases the potential for sustainable change (Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021).

Retention faces issues as a result of the lack of sense of belonging amongst students, mentors in the department, financial and educational support, and the department climate (Estaville et al., Citation2006b; King et al., Citation2018; Levine et al., Citation2007; Vila-Concejo et al., Citation2018). For undergraduate and graduate student retention, multiple programs have found that identifying students who are either in a geosciences major already, or have identified interests in certain hobbies related to the geosciences is a place to start with retaining students in the field (Baber et al., Citation2010; Hallar et al., Citation2010; Levine et al., Citation2007; O’Connell & Holmes, Citation2011). Still, much of the issues of retention stems from the lack of mentors and fellow students of minoritized identities, which can lead to feelings of isolation and lack of belonging in the department. Lacking these individuals also can contribute to a less welcoming/open department climate overall, and further “push out” minoritized individuals (Hernandez et al., Citation2018; Núñez et al., Citation2020; Vila-Concejo et al., Citation2018; Yoder & Mattheis, Citation2016). The lack of belonging does not just come from a matter of difference, but also personal disinterest by mentors (Faria et al., Citation2019) and the institutions failing to provide concrete support for students from minoritized backgrounds. This disinvestment spirals as minoritized students eventually leave top-tier research environments because of the disinvestment and continue to stay away from similar institutions. This creates a pattern of ongoing disinvestment by these institutions that continues to undermine efforts of anti-racist social justice in the geosciences (Ali & Prasad, Citation2021).

Issues of placement are one of the clearest places where minoritized geoscientists are lost. Especially at the postdoctoral phase, minoritized groups are found to struggle to find placement in positions of prestige (Dutt, Citation2010; Holmes, Citation2015; Vila-Concejo et al., Citation2018). Between the PhD and seeking a faculty position, a multitude of push and pull factors can also lead to not placing at all in a position, while others may find a position but fail to achieve tenure or full professor status (Dutt et al., Citation2016; Holmes, Citation2015). Improving placement is more difficult because of the job evaluation process, but suggestions include actively advocating for more women (and other groups) in higher roles, promoting those who are high-achieving, creating awareness of bias, and having conversations about these biases and structures that support them. The barriers are wide-ranging, but many exist within job opportunities and evaluation, representation, and from the academy’s demands of institutional civility. A lack of mentorship, investment via poor recommendation, and exclusion in presentation opportunities, leads to a “chilly climate” (King et al., Citation2018; Ratliff, Citation2012) for people from minoritized backgrounds and a stagnation of their careers (Ali & Prasad, Citation2021; Dutt, Citation2019; Dutt et al., Citation2016; King et al., Citation2018). Lamont-Doherty found specific success from the creation of an Office of Academic Affairs and Diversity from 2008 to 2021, incorporating a diversity officer who was on all hiring committees, and transparency in their hiring processes to the department and larger scientific community (Barbier, Citation2003; Dutt, Citation2019; Estaville et al., Citation2006c; Holmes & O’Connell, Citation2015; Williams et al., Citation2007). Nevertheless, the same institution has yet to hire a Black or Indigenous faculty member of any gender (Acosta et al., Citation2022) and these reported successes overwhelmingly positively impacted white women.

Perhaps the pipeline model itself is part of the issue, with a focus on increasing the numbers of minoritized academics with little change in the structure of the academy. However, the pipeline model is not the only approach for addressing the lack of diversity in the geosciences. More recent work has pushed other models and frameworks. Holmes and O’Connell (Citation2015) spend multiple chapters of their book Women in the Geosciences: Practical, Positive Practices Toward Parity encouraging readers to address bias, encourage activities that address unconscious bias, increase transparency in evaluation, and change the models of our research and structures of our departments, conferences, and funding. The braided river model envisions a framework rooted in what a successful modern STEM career can be when diversity is welcomed and valued. This model allows for multiple points of entry and the incorporation of the surrounding environments’ contributions to the health of the river, or a more inclusive STEM workforce (Batchelor et al., Citation2021). Núñez et al. (Citation2020) advocate for a specific lens of intersectionality that stops trying to simply fill the pipeline, but instead considers the myriad experiences that individuals may have and bring with them as informed by their various identities. This allows for a more complete understanding of the barriers they face, and what needs to change in their environment.

Structural change is required to create significant systemic change, especially in an academic system that was constructed to prevent success of people who are not cisgender, straight, white men. Changing graduate programs to value service and teaching alongside research allows for more fluid and innovative research methods and direct attainment of larger university and department goals (Bernard & Cooperdock, Citation2018; Sherman-Morris et al., Citation2013). Incorporating Indigenous knowledge and research methods supports and values the perspectives and abilities of Indigenous scholars in the geosciences (Daniel, Citation2019, Lopez & Cesspooch, Citation2019). As geosciences departments grapple with dwindling enrollment, we have to consider growing our enrollment through targeted recruitment of students who are more concerned with helping people and the environment (Carter et al., Citation2021).

Outreach efforts

Outreach in STEM and the geosciences is a necessary method for recruiting students from minoritized backgrounds, especially Black and Indigenous students, into the geosciences. Some of the work in this realm have provided cases of successful program creation, whether they be camps, mentorship programs, or teacher outreach (Estaville et al., Citation2006a). Other works speak generally to the underpinning qualities of departments that successfully recruit from diverse student populations (Baber et al., Citation2010). All of these programs push a framework rooted in outreach, education, and research.

Outreach is the direct interaction with the general community, usually including the students, teachers, and their parents, with the intention of connecting with them. Education involves the sharing of knowledge with the communities interested in the work of the geosciences, and basic principles. Research in these programs is usually conducted through surveys of the participants in the outreach programs, identifying successes and failures in the program for achieving the program goals and improving upon them.

Successful programs have provided scholarships, promotional materials that help to build a lasting connection to the institution hosting the students, and other materials and interventions to increase the accessibility of these programs (Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021; Hallar et al., Citation2010; Stokes et al., Citation2007). Mentorship is also crucial for outreach programs, with peer mentor and academic mentors providing support, advice, and representation to increase student comfort and follow-up on interests (Baber et al., Citation2010; Frye et al., Citation2018; McEntee, Citation2019; Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021). Outreach can be difficult and time-consuming to conduct, requiring the development of strong relationships and ties with community members to make these programs sustainable and effective (Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021). Further, this work can be extra taxing for academics of color, who often find themselves expected to do this work on top of their academic work, without recognition or tangible support structures (Gewin, Citation2020).

It is common to not receive academic recognition for outreach, often deemed service in academic departments, which makes conducting outreach of less interest to those focused on individual development and promotion in academia. Quantitatively evaluating the importance of outreach and its value to an academic portfolio is difficult due to poorly defined definitions and metrics (Armani et al., Citation2021). For these reasons, it is understandable why individual scholars are less inclined to undertake outreach programs, and instead outreach is deemed a “passion project” and disregarded by researchers and departments prioritizing high publication rates and research metrics. Instead, Ali and Prasad (Citation2021) suggest that for high level research institutions to demonstrate best practices in their research, education and social responsibility, their performance in DEI efforts must be evaluated as part of their ranking. Changing the perception and value of outreach as a tool to improve the landscape and performance of DEI efforts in geoscience requires a shift in academic expectations such that service is an additional, supported, and weighted metric for career progression (Armani et al., Citation2021). In this article, we display a case of a successful iteration of outreach, which is acknowledged as an effective method for addressing the lack of diversity in the geosciences, and show the places where disinvestment occurred. This disinvestment is then shown to create a loss of time and ultimately harm the minoritized scholars doing this work.

Typology of barriers with contextualized examples

This article identifies and reviews our experiences as geoscientists from minoritized backgrounds in our efforts for increasing diversity in the geosciences within our local context. To do so, we reviewed our research journal notes, camp documentation, videos, photos, and text messages for corroboration of our experiences from this time. Our notes included self-reflection documents via emails, text messages, and summaries of meetings, which detail our experiences, reactions, and feelings as we progressed in building and conducting a geoscience camp. Through evaluation of these documents, we present our experiences in the context of the barriers we faced, presented through a journey schematic. We refer to this journey as a winding road, where we experienced multiple barriers and had to work on the fly to overcome them. In the following section, we present our winding road journey and join our personal reflections to offer a glimpse into the experiences of two minoritized students consistently met with disinterest of DEI in geosciences and the impacts that disinvestment had on us and our ability to be successful in creating and sustaining a geoscience camp (Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021).

We identified three different barrier types in our journey toward running the camp, each of which cost time and effort on our behalf. In this section we suggest a typology of barriers, discuss the details of each barrier type, highlight key responses we experienced as we tried to overcome the barrier, and quantify the time and effort cost to the journey as a whole. We then give contextualized barrier examples and show how barrier types interact with each other, for example how an alternative route gave us a solution to the initial roadblock. We also explain our perspectives as we navigated each experience and overcame each barrier. Finally, we argue that the time and effort cost, and the failure of the camp reiteration (Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021), resulted in harm toward us and our careers.

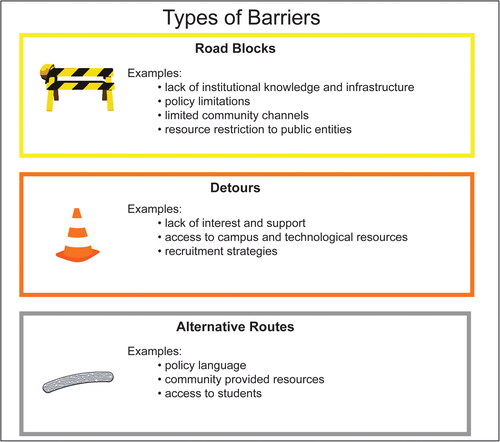

The barriers we experienced are separated into three major categories. These categories are presented in and a brief description as follows: roadblocks are unpassable institutional barriers, representing moments in our journey where the route we were taking was no longer possible, and we had to overcome the barrier by creating a new route. Detours are passable institutional barriers defined as moments along the journey that took considerable time and effort, but through our resilience we were able to trudge through this type of barrier. Alternative routes are the pathways we took when we could no longer follow the route we expected to pursue and these newly defined pathways were made possible by supportive systems outside of the institution.

Figure 1. The suggested typology of barriers. Examples of barrier types with the coinciding barrier icon including roadblocks, detours, and alternative routes.

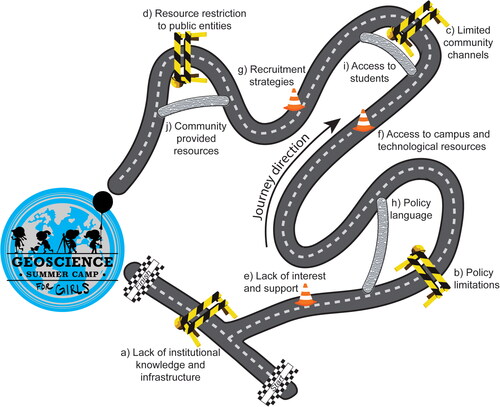

As we pursued our journey of creating the camp, we often experienced a sequence of events where we would run into a roadblock, scramble to find an alternative route and continue the now modified journey, or we would run into a detour and spend a lot of unexpected effort to continue through our journey. These barriers were not confined to any stage during the process of creating and running the camp. Instead, they were scattered along the journey, hidden in the dark corners of our institution, and waiting to completely upend our hard work and efforts. Each barrier influenced us in different ways, mostly manifesting in different types of self-esteem stressors, taking hits at our perceived ability, lowering our confidence, and disrupting the motivation we had built to make this camp successful. We argue that these hits, borne out of institutional disinvestment and individual disinterest, resulted in harms to ourselves and our professional progress as each harm took time for us to build our confidence and to come out of each barrier successfully. Further, these harms also serve as an example of how common barriers that are often considered part and parcel of bureaucratic and administrative realities of the university not only negatively impact professional development amongst minoritized members of the academy, but also impede DEI efforts when the university does not consider them part of the core goals the university is focused on investing in. We present this journey as a schematic in and discuss individual moments by including real examples of our journey, our reactions, and how we resolved certain barriers while putting the examples in the context of our barrier types.

Figure 2. A schematic detailing the journey of building the geoscience camp for middle school girls. In this schematic the barriers are shown as their respective type detailed in , and the relationships and interactions of barriers are depicted for roadblocks (a-d), detours (e-g), and alternative routes (h-j). The anticipated start and finish of the journey are shown by checkered flags, and the direction of the final, winding road journey is shown by the arrow “journey direction.”

Roadblocks

The first barrier we experienced when creating the camp was a roadblock. The roadblock occurred at the conception of the camp as an event because of a lack of institutional knowledge and infrastructure (). This roadblock was set in place, with the lack of institutional knowledge being cited, at the administrative level where graduate students lacked access. Because the administration did not have the institutional knowledge or infrastructure in place to implement the idea of the event (the camp), it was determined that the necessary pieces to make the event occur would not be possible (such as: logistics, funding, and recruitment of minors). This resulted in the bureaucracy of the institution blocking off access to its institution-based resources to be redirected to the creation of the event (the camp). Thus, we as graduate students had to continue on a completely alternate route, with none of the resources of the institution. This alternate route thus had a grassroots approach. This first roadblock exemplifies how bureaucratic institutions such as universities and colleges lack the institutional knowledge and infrastructure to engage with innovative ideas, which are often required to address long standing issues of systemic racism and bias (Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021).

The next set of roadblocks encountered occurred early in the planning phase of the event. This specific roadblock could be described as the legal issues surrounding bringing minors into a college campus setting, specifically policy limitations (). Specifics such as university-required plans for minor protections and recruitment and background checks were difficult to complete because graduate students are new members of the university setting, and lack the knowledge for starting these processes successfully or using the appropriate language for legal documents. Again, because new or ostracized members of institutions (such as those who are minoritized because of systemic racism and bias) are not advanced enough in the university, they lack the knowledge or power to complete institutionally-required processes efficiently. This lack of personal investment from insiders of the institution (such as administrative members of the university) thus can block out the ability of an outsider who is also part of the university to bring innovation to the institution.

Innovative events in any university will require establishing new connections and drawing on other parts of community networks, and the creation of the camp was no different. However, in the planning process, another roadblock was clear – limited community channels () between the university and broader area. A connection with the local schools was ultimately required to access the community of students we wanted to serve. There were no community channels from the university to the school we intended to work with for the camp’s formation. Particularly, there were no connections with STEM teachers who taught grade levels 6–8. The community channels accessible to university members were limited to other university entities, and thus resulted in a roadblock hindering our connection to local STEM teachers and curriculum builders. Thus, forging new channels in the community was done by reaching out to local school STEM organizers.

The final roadblock experienced was related to a specific resource restriction to public entities imposed by the university – an inability to provide transportation () to ensure students could come to the campus. Again, this camp was an explicit initiative in diversity, equity, and inclusion. Thus, equitable solutions to supporting students from minoritized backgrounds attending the camp were key. The students were facing issues attending the camp, with reasons spanning working and unavailable parents, confusion or fear regarding visiting campus, and a lack of transportation. The initial potential to address this barrier was limited from the university side, displaying a disconnect between what campers needed and what could be offered to them in terms of access to our university.

Detours

The development of the camp required certain resources that then resulted in detours en route to receiving those resources. These detours are listed and outlined below ().

One significant hurdle that led to a detour was a lack of interest and support () from the majority of peers and mentors at the university for developing the camp and advancing the project. However, as graduate students with limited experience in this arena, we still needed guidance and support for this initiative to be successful. Our detour here led us to finding outside support and guidance in the form of STEAM instructional coordinators at our partner middle school. After the majority of logistics and planning of the camp was complete, recruiting support from peer graduate students and office administrator support was easier because of clearer needs on time and effort for camp organization tasks. These included tasks such as serving as camp counselor volunteers or organizing purchases.

Another detour was uneven access to campus and technological resources (). For example, we encountered that we could not, as two individual students, reserve a specific space on campus. Most of our planned activities for the camp were located in spaces that we knew we could access as graduate student members of our university designated building, for example the building common space and teaching and computer labs. When we began searching how to reserve a university level space, in this case the main university quad, we found that we could not reserve this space as graduate students. Through several rounds of communication with those administrators or grounds management, it became clear that the space we were interested in would not be available to us. This required strategic maneuvering to access an area that would provide the resources necessary for key camp events.

The goal of our camp was to bring local students who are underrepresented in geosciences to our campus, but we had no clear recruitment strategies () to connect to these students. When we prompted university leaders, a few options came up including putting the camp on a university outreach website or sharing info via emails to several university entities. None of these options reached the audience we were hoping to connect with directly, local middle school students who are underrepresented in the geosciences. Instead, these methods relied on the students and their families to seek out and know where to look for such opportunities. The lack of a recruitment strategy that accounted for ways to reach a diverse and minoritized audience meant that we had to create our own recruitment strategies that would reach the populations we were most interested in contacting. When we realized we needed to create our own recruitment strategy to access student campers (), we began to build one that relied on our previous experience conducting outreach at schools. We began reaching out to students through visiting their classes and participating in after-school activities, to share our careers and hand out recruitment materials for the camp (flyers, sign-up sheets, information). We spent a lot of time and effort during this early recruitment strategy and we received a few (less than 10) student sign ups.

Alternative routes

This section details the alternative routes that were created in the face of barriers that could not be detoured, but required a new path entirely ().

As we began seeking community collaborations with a local middle school, we detailed the legal barriers we had been experiencing surrounding the policy language we required for the camp given the interaction with minors, and to our delight, they offered us copies of legal documents they had prepared for similar opportunities, creating an alternative route (). We also, through this motivated conversation, found that both of us (Julia and Aída), through serving as official mentors through the local community program partnership with school districts, had passed background checks for the school district and could thus interact with middle school students allowing for recruitment. This again meant that instead of having to go through traditional and time consuming processes to secure legal compliance, we were able to learn of existing ways to accomplish compliance effectively and efficiently.

An alternative route occurred during the late stage of our recruitment strategies through an unexpected and direct line of access to students () made possible through a local middle school administrator. While our newly created recruitment strategy to reach historically excluded students from a local middle school resulted in 10 successful enrollments, we were hoping to recruit at least 30 girls. Through our ongoing, reciprocal relationship with the school, we participated in many after-school events. At such an event, we asked the middle school principal if she had any recommendations, hoping that our sustained involvement would signal our real interest in offering concrete opportunities for her students. To our delight, she immediately said, “I can send an email to our families!”, which resulted in an influx of sign ups and we filled the camp to capacity within two hours, and had at least 40 students on the waitlist. Our initial detour did attract some students, but it was not the most effective or efficient method for achieving our goals. Working with our community partner produced an alternative route that netted the most favorable outcome.

Finally, an alternative route we experienced was to overcome the transportation roadblock was possible through community-provided resources (). When we mentioned the lack of transportation opportunities to the community collaborators we gained at the local middle school, it was a known fact and the conversation immediately switched to brainstorming how to solve the problem. Within 30 minutes of our discussion with community members, we identified a solution: the school would provide transportation to and from their school campus. In this example, while something as simple as transportation could be a huge barrier for many campers, which we deemed a roadblock, we identified an alternative route by offering campers an opportunity of accessible transportation that they and their families felt safe and comfortable accessing.

Reflection

We understand that this disinterest and disinvestment is not necessarily borne out of harsh negativity or hatred, but it is instead a product of the white academic system. Balancing interest in outreach opportunities and the lack of value for service in academia is not only difficult but it is harmful to one’s career under the current system. Therefore, if one has little to personally gain from outreach or service aimed at improving DEI in geosciences, how can they justify an interest let alone support institutional investment in these ventures? Minoritized scholars often do not see these outreach and service opportunities as agenda items to freely be interested or uninterested in but often see them as connected to their personal survival in the academy (Gay, Citation2004). Why do minoritized scholars, like ourselves, care so much about DEI and outreach? Because we are personally interested in these efforts to make it safe for us to work in these fields. We feel this is the biggest disconnect between how we navigate academia and how our white scholar counterparts do. We risk our safety if we do not create these spaces for ourselves whereas white, majoritized scholars are personally disinterested because it would require them to change and do things that are not valued toward their academic progression, and thus they may view outreach and service work as outside the scope of their work or “extra.” Instead, for us it is crucial to our safety and persistence in this field.

In a lot of ways, our experiences are no different than our peer, minoritized scholars. It is well-documented that minoritized members’ thoughts, ideas, and contributions are ignored or undervalued (Levine et al., Citation2021). These experiences resulted in harm on our behalf, often taking hits at our perceived ability and self-esteem but also resulting in large amounts of time lost to recuperate, rebuild, and reenvision.

The extra time lost after we experienced harm is depicted by the winding road (), which amounted to 680 hours per author for a total time investment of 1360 hours of labor (see Supplemental Materials). We understand roadblocks, detours and alternative routes are commonplace in many journeys, but we believe the extent and magnitude of each barrier was exaggerated through the disinterest and disinvestment we experienced. This time lost represents time we could have spent advancing our careers by gaining and improving academic skills, conducting our research, analyzing data, and writing and publishing papers – all of which were vital to our success as PhD candidates. We believe these harms result in the reasons minoritized members leave academia, which leads to the lack of diversity we are all trying to solve in the geosciences. To address this, let us look within ourselves and our departments. Through a reflection on our own experiences as white Latina geoscientists, we show how a simple lack of personal interest compiles into institutional disinvestment which can be detrimental to the success of minoritized scholars. As we move forward, we must consider how we may work together to honor and value the work of outreach and service in academia in a way that addresses the root cause of disinterest and disinvestment. Actions beyond reading groups and discussion, such as self-reflection on scholarly networks, mentorship practices, pursuing accountability and justice, and supporting others through the power we wield enables us to address issues of injustice and harm rooted in white supremacy and structural racism (Keisling et al., Citation2020).

Recommendations

This section identifies recommendations for universities and the geosciences at-large to invest in diversity, equity, and inclusion and long-term structural change both as opportunities arise and as part of the work and effort of these institutions.

Build a culture of retaining institutional knowledge

To adjust rapidly to outreach opportunities, university members require a mechanism to retain institutional knowledge of outreach activities. For example, the lack of institutional knowledge or support led us to our first fork in our journey toward creating the camp. In , this new route is a longer and more winding road compared to the straight-forward route that we initially pursued. This route is longer because we gained and created institutional knowledge along the way. With the failure of the camp continuation (Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021), the institutional knowledge that we gained during this process was lost again to the university as we have left and taken that knowledge with them. When the diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are not a primary commitment of the institution, then time and space to these related initiatives are not dedicated and preserved. This results in unnecessary time and effort being lost to creating back-up plans after roadblocks are encountered and alternative routes created, which is ultimately a waste of resources, and generates uncertainty in the investment of the institution in these initiatives.

Encourage and uplift differing perspectives

When creating an outreach event for local community members, it is important to make sure that all perspectives – but especially those that are most minoritized – are uplifted. In the case of our camp, the lack of transportation opportunities was a common concern for most of our camp participants. Listening to the camp participants highlighted a clear barrier that students might experience that could hinder camp participation. For us as camp planners, we knew the obvious fix would be to offer transportation from the school, because all girls were able to get to their school via various commuting options as they did every day for school. In science camps with similar goals of broadening participation, transportation was also identified as an issue for camp participants and solutions included offering free transportation for students and identifying a centralized pickup and dropoff location (Frye et al., Citation2018). When we mentioned this need to our university, to rent a bus that could transport the girls to and from their school to our campus, it was initially heard but there were no solutions put forth. It was difficult for university leaders to understand how transportation would be needed by local community members because their interactions with the university were daily. This daily interaction could not compare to the experiences of those who had no connection to the university, despite living in the same town as the university. The alternative route we followed was possible through the support of local community members who understood our participants’ perspective and had already created solutions to the barriers they faced. By encouraging various voices to share their experiences and listen to the solutions that have been successful, our institutions will be better suited to provide the proper resources and support so that participation is not hindered by barriers invisible to us through our privileged experience.

Build and support institutional partnerships

Without purposeful and focused partnerships, our institutions may fall into the habit of only receiving participation from those who know that opportunities exist and where to find them, which limits our pool of participants and lowers the likelihood that those who have been historically excluded will access the opportunities we provide. Building and sustaining these partnerships allows our institutions to continue to support our goals of broadening participation through continuing access to the communities we want to bring into our university. Through supporting these partnerships via action and offering real resources and opportunities, we signal to these communities that we are deserving of their participation. When sustained partnerships occur and clear lines of communication are met, our institutions may identify more opportunities to engage with the historically excluded groups we want to bring into our field and both institutions in the partnership experience long term benefits (Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021). In the case of developing recruitment strategies for the camp, the time and effort to build a relationship with the local school resulted in a small number of participants enrolling. When we were successful in building a more deliberate partnership, a new strategy that relied on more direct connections and access to students through school administrators resulted in enrollment that far exceeded our initial efforts. This is an example of how when these partnerships are secured and maintained, the alternative route initially created between them becomes the new and efficient pathway, leading to faster and more productive results in reaching shared goals between both institutions (Guhlincozzi & Cisneros, Citation2021).

All of these recommendations thus rely on a focused and deliberate investment toward outreach and service efforts to improve DEI in the geosciences. We echo the calls of Jones (Citation2021), Ali and Prasad (Citation2021), and Armani et al. (Citation2021) to incorporate mechanisms that build and financially support the importance and value of service and outreach efforts into our current evaluation and metrics that define the performance of geoscience institutions and scholars.

Conclusion

The barriers we experienced in pursuing efforts to improve DEI in geosciences were built through the accumulation of several disinvestments by the institution (Ali & Prasad, Citation2021). These disinvestments were enabled by the current structure of academia, which is reliant on preventing interest in pursuing anti-racist justice (Faria et al., Citation2019). The way this prevention manifests is through the undervaluation of service and outreach work (Armani et al., Citation2021). This manifestation leads to personal disinterest and cumulative university disinvestment (Ali & Prasad, Citation2021; Faria et al., Citation2019), which results in harm when a minoritized university member pursues service and outreach work related to DEI. Further, this university disinvestment is reflective of the broader society’s disinvestment in minoritized communities, and a participating factor of systemic and structural racism. To address this harmful mechanism of racism within the university could lead to actual anti-racism efforts that engender real social change. Geoscientists have a duty to support the creation of a “sustainable global society” (Armani et al., Citation2021), which requires our commitment to ensuring a safe and empowered pursuit of a geosciences education for all people.

Our ability as minoritized geoscientists to build resilience as we overcame each barrier is not something to be proud of. Instead, we hope the presentation of our experiences and the resultant harms, via time and effort lost, will offer motivation to consider how to improve the ways we navigate seeking anti-racist justice in academia. We must ask whether our current expectations and systems can be modified to minimize harms in academia.

Our discussion of disinvestment by the institution relies on reviewing our personal experiences through notes and other saved materials from this time and linking to similar experiences minoritized scholars have detailed in the literature (Faria et al., Citation2019; Levine et al., Citation2021), and is thus limited to our own partial knowledge and understandings of these situations (Jackson & Neely, Citation2015). However, these notes, content, and reflections provide an ethnography of our experiences as white Latina geoscientists in an academic, R1 institution that mirror the experiences of other minoritized scholars in the geosciences (Ali & Prasad, Citation2021; Dutt, Citation2010; Dutt et al., Citation2016; Holmes, Citation2015; Kaplan & Mapes, Citation2016; Núñez et al., Citation2020).

We offer this reflection and perspective in demand of more accomplices in anti-racist social justice (Jones, Citation2021). We (including those of us with both white privilege and a minoritized experience) cannot continue to let predominantly white institutions and white academics continue to marginalize minoritized scholars, especially Black and Indigenous scientists. Our experiences as geoscientists did not put us in mortal danger, but for others, that is exactly what can happen when a Black geoscientist is surrounded by white colleagues who do not recognize or invest in the goals of anti-racist social justice (Adams, Citation2021; Anadu et al., Citation2020). Our colleagues’ environments and knowledge and livelihoods are at risk when we ignore and participate in systems that disadvantage or dispossess them of their land and personal freedoms (Cartier, Citation2019; Curley & Smith, Citation2020; Daniel, Citation2019; Ishiyama, Citation2003; Lee et al., Citation2020, Farrell et al., Citation2021). White geoscientists cannot continue to enable these harmful structures if they wish to see their institutions diversify and support anti-racist social justice. White geoscientists cannot continue to be personally disinterested in the pursuit of anti-racist social justice in their daily lives and institutions. The cost is too high, and the need too great.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the GSA 2020 Pardee Symposium: The Next Generation of Geoscience Leaders: Strategies for Excellence in Diversity and Inclusion for being the arena where the initial idea of this article was conceived and presented as in this manuscript. We also thank Dr. Jorge San Juan for his support during the creation of the camp by making the geoscience camp logo that is seen surrounded by blue in .

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acosta, K., Keisling, B., & Winckler, G. (2022). Past as prologue: Lessons from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Task Force. Journal of Geoscience Education, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2022.2106090

- Adams, L. (2021, July 28) SC father organizing 3rd search for son who disappeared in Arizona desert. WIS News, 10, 1–9. https://www.wistv.com/2021/07/28/sc-father-organizing-3rd-search-son-who-disappeared-arizona-desert/

- Ali, H. N., & Prasad, M. (2021). On ranking and representation in the geosciences. AGU Advances, 2(4), e2021AV000474. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021AV000474

- Anadu, J., Ali, H., & Jackson, C. (2020). Ten steps to protect BIPOC scholars in the field. Eos, 101. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO150525

- Armani, A. M., Jackson, C., Searles, T. A., & Wade, J. (2021). The need to recognize and reward academic service. Nature Reviews Materials, 6(11), 960–962. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-021-00383-z

- Baber, L. D., Pifer, M. J., Colbeck, C., & Furman, T. (2010). Increasing diversity in the geosciences: Recruitment programs and student self-efficacy. Journal of Geoscience Education, 58(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.5408/1.3544292

- Barbier, E. (2003). Righting the balance: Gender Diversity in the Geosciences. Eos, 84(31).

- Batchelor, R. L., Ali, H., Gardner-Vandy, K. G., Gold, A. U., MacKinnon, J. A., & Asher, P. M. (2021). Reimagining STEM workforce development as a braided river. Eos, 102. Published on 19 April 2021. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO157277

- Bednarz, S. W. (2016). Placing advanced placement ® human geography: Its role in U.S. Geography Education. Journal of Geography, 115(3), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2015.1083043

- Bernard, R. E., & Cooperdock, E. H. G. (2018). No progress on diversity in 40 years. Nature Geoscience, 11(5), 292–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0116-6

- Carter, S. C., Griffith, E. M., Jorgensen, T. A., Coifman, K. G., & Griffith, W. A. (2021). Highlighting altruism in geoscience careers aligns with diverse US student ideals better than emphasizing working outdoors. Communications Earth & Environment, 2(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00287-4

- Cartier, K. M. S. (2019). Keeping indigenous science knowledge out of a colonial mold centering research in values. Eos, 100. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO137505

- Curley, A., & Smith, S. (2020). Against colonial grounds: Geography on Indigenous lands. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(1), 37–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820619898900

- Daniel, R. (2019). Understanding our environment requires an indigenous worldview. Eos, 100. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO137482

- Dutt, K. (2010). Junior and senior geoscientists discuss issues facing women in a male-dominated field: A networking luncheon for women scientists; Palisades, New York, 30 April 2010. Eos, 91(39), 347–347. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010EO390006

- Dutt, K. (2019). Promoting racial diversity in geoscience through transparency. Eos, 100, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO136977

- Dutt, K., Pfaff, D. L., Bernstein, A. F., Dillard, J. S., & Block, C. J. (2016). Gender differences in recommendation letters for postdoctoral fellowships in geoscience. Nature Geoscience, 9(11), 805–808. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2819

- Estaville, L. E., Brown, B. J., & Caldwell, S. (2006a). Geography undergraduate program essentials: Recruitment. Journal of Geography, 105(3), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340608978670

- Estaville, L. E., Brown, B. J., & Caldwell, S. (2006b). Geography undergraduate program essentials: Retention. Journal of Geography, 105(2), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340608978660

- Estaville, L. E., Brown, B. J., & Caldwell, S. (2006c). Geography undergraduate program assessment: Placement. Journal of Geography, 105(6), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340608978693

- Faria, C., Falola, B., Henderson, J., & Maria Torres, R. (2019). A long way to go: Collective paths to racial justice in Geography. The Professional Geographer, 71(2), 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2018.1547977

- Farrell, J., Burow, P. B., McConnell, K., Bayham, J., Whyte, K., & Koss, G. (2021). Effects of land dispossession and forced migration on Indigenous peoples in North America. Science, 374(6567), 578. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe4943

- Frye, M., Wang, C., Nair, S. C., & Burns, Y. C. (2018, April) miniGEMS STEAM and programming camp for middle school girls. In 2018 CoNECD-the Collaborative Network for Engineering and Computing Diversity Conference.

- Gay, G. (2004). Navigating marginality en route to the professoriate: Graduate students of color learning and living in academia. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 17(2), 265–288.

- Gewin, V. (2020). The time tax put on scientists of colour. Nature, 583(7816), 479–481. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01920-6

- Guhlincozzi, A., & Cisneros, J. (2021). A framework for addressing the lack of diversity in the Geosciences through evaluating the current structure of institutional efforts. GeoJournal, 87(S2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10418-1

- Hallar, A. G., McCubbin, I. B., Hallar, B., Levine, R., Stockwell, W. R., Lopez, J. P., & Wright, J. M. (2010). Science in the mountains: A unique research experience to enhance diversity in the geosciences. Journal of Geoscience Education, 58(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.5408/1.3534851

- Hernandez, P. R., Bloodhart, B., Adams, A. S., Barnes, R. T., Burt, M., Clinton, S. M., Du, W., Godfrey, E., Henderson, H., Pollack, I. B., & Fischer, E. V. (2018). Role modeling is a viable retention strategy for undergraduate women in the geosciences. Geosphere, 14(6), 2585–2593. https://doi.org/10.1130/GES01659.1

- Holmes, M. A. (2015). Who receives a geoscience degree? In M. A. Holmes, S. Oconnell, & K. Dutt (Eds.), Women in the Geosciences: Practical, Positive Practices Toward Parity (pp. 13–16). Wiley.

- Holmes, M. A., & O’Connell, S. (2015). Hiring a diverse faculty. In M. A. Holmes, S. Oconnell, & K. Dutt (Eds.), Women in the Geosciences: Practical, Positive Practices Toward Parity (pp. 95–107). Wiley.

- Huntoon, J. E., & Lane, M. J. (2007). Diversity in the geosciences and successful strategies for increasing diversity. Journal of Geoscience Education, 55(6), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.5408/1089-9995-55.6.447

- Ishiyama, N. (2003). Environmental justice and American Indian tribal sovereignty: Case study of a land-use conflict in Skull Valley, Utah. Antipode, 35(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00305

- Jackson, P., & Neely, A. H. (2015). Triangulating health: Toward a practice of a political ecology of health. Progress in Human Geography, 39(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513518832

- Jones, J. C. (2021). We need accomplices, not allies in the fight for an equitable geoscience. AGU Advances, 2(3), e2021AV000482. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021AV000482

- Kaplan, D. H., & Mapes, J. E. (2016). Where Are the Women? Accounting for discrepancies in female doctorates in U.S. Geography. The Professional Geographer, 68(3), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2015.1102030

- Keisling, B., Bryant, R., Golden, N., Stevens, L., & Alexander, E. (2020). Does our vision of diversity reduce harm and promote justice? GSA Today, 30(10), 64–65. https://doi.org/10.1130/GSATG429GW.1

- King, L., MacKenzie, L., Tadaki, M., Cannon, S., McFarlane, K., Reid, D., & Koppes, M. (2018). Diversity in geoscience: Participation, behaviour, and the division of scientific labour at a Canadian geoscience conference. FACETS, 3(1), 415–440. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2017-0111

- Lee, R., Ahtone, T., Pearce, M. (2020). Land-Grab Universities. High Country News. https://www.landgrabu.org/#credits

- Levine, R., González, R., Cole, S., Fuhrman, M., & Le Floch, K. C. (2007). The geoscience pipeline: A conceptual framework. Journal of Geoscience Education, 55(6), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.5408/1089-9995-55.6.458

- Levine, S. S., Reypens, C., & Stark, D. (2021). Racial attention deficit. Science Advances, 7(38), eabg9508. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abg9508

- Lopez, R. D., & Cesspooch, A. (2019). Laying proper foundations for diversity in the geosciences. Eos, 1, 2017–2019.

- Lozier, S., & Clem, S. (2015). Mentoring Physical Oceanography Women to Increase Retention. M. A. Holmes, S. Oconnell, & K. Dutt (Eds.), Women in the Geosciences: Practical, Positive Practices Toward Parity (pp. 124–134). Wiley.

- Marín-Spiotta, E., Barnes, R. T., Berhe, A. A., Hastings, M. G., Mattheis, A., Schneider, B., & Williams, B. M. (2020). Hostile climates are barriers to diversifying the geosciences. Advances in Geosciences, 53, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-53-117-2020

- McEntee, C. (2019, December). AGU’s bridge program creates opportunities for underrepresented students. Eos, 100. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO137314

- Núñez, A. M., Rivera, J., & Hallmark, T. (2020). Applying an intersectionality lens to expand equity in the geosciences. Journal of Geoscience Education, 68(2), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2019.1675131

- O’Connell, S., & Holmes, M. A. (2011). Obstacles to the recruitment of minorities into the geosciences: A call to action. GSA Today, 21(6), 52–54. https://doi.org/10.1130/G105GW.1

- Oludurotimi, O. A., Ba, J.-C M., Ghebreab, W., Joseph, J. F., Mayer, L. P., & Levine, R. (2012). Geosciences Awareness Program: A Program for Broadening Participation of Students in Geosciences. Journal of Geoscience Education, 60(3), 234–240. https://doi.org/10.5408/10-208.1

- Ratliff, J. M. (2012). A chilly conference climate: The influence of sexist conference climate perceptions on women’s academic career intentions [Ph.D. thesis] (p. 110). University of Kansas.

- Sherman-Morris, K., Brown, M. E., Dyer, J. L., Mcneal, K. S., & Rodgers, J. C. (2013). Teachers’ geoscience career knowledge and implications for enhancing diversity in the geosciences. Journal of Geoscience Education, 61(3), 326–333.

- Stokes, P. J., Baker, G. S., Briner, J. P., & Dorsey, D. J. (2007). A multifaceted outreach model for enhancing diversity in the geosciences in Buffalo. Journal of Geoscience Education, 55(6), 581–588. https://doi.org/10.5408/1089-9995-55.6.581

- Velasco, A. A., & De Velasco, E. J. (2010). Striving to diversify the geosciences workforce. Eos, 91(33), 289–290. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010EO330001

- Vila-Concejo, A., Gallop, S. L., Hamylton, S. M., Esteves, L. S., Bryan, K. R., Delgado-Fernandez, I., Guisado-Pintado, E., Joshi, S., da Silva, G. M., Ruiz de Alegria-Arzaburu, A., Power, H. E., Senechal, N., & Splinter, K. (2018). Steps to improve gender diversity in coastal geoscience and engineering. Palgrave Communications, 4(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0154-0

- Wechsler, S. P., Whitney, D. J., Ambos, E. L., Rodrigue, C. M., Lee, C. T., Behl, R. J., Larson, D. O., Francis, R. D., & Holk, G. (2005). Enhancing diversity in the geosciences. Journal of Geography, 104(4), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340508978630

- Williams, Q. L., Morris, V., & Furman, T. (2007). A real-world plan to increase diversity in the geosciences. Physics Today, 60(11), 54–55. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2812124

- Yoder, J. B., & Mattheis, A. (2016). Queer in STEM: Workplace Experiences Reported in a National Survey of LGBTQA individuals in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1078632