ABSTRACT

To better understand the relationship between second-language (L2) listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness, we examined the moderating effects of listening tests and learner samples while focusing on aspects of metacognitive awareness. Students of English-as-a-foreign-language at a Japanese university (n = 75; the 2019 cohort) took the Test of English as a Foreign Language Institutional Testing Program (TOEFL ITP®) test, a paper-based TOEFL; the TOEFL Internet-based test (TOEFL iBT®); and the Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ). Another group of students (n = 107; the 2020 cohort) took the TOEFL ITP and MALQ. Random forest analysis was applied to the results of the 2019 cohort, showing that, in order of importance, person knowledge, mental translation, and directed attention were related to listening comprehension in both listening tests. Problem solving was not related in either listening test. Further, planning and evaluation strategies were related to listening comprehension only in the TOEFL ITP. Comparison between the TOEFL ITP results of the 2019 and 2020 cohorts showed that only person knowledge was related to listening comprehension across the two cohorts, indicating a strong generalizability of person knowledge and weak generalizability of the remaining metacognitive strategies across learners. Implications and future directions are discussed.

Introduction

Successful second-language (L2) listening comprehension requires complex cognitive processes that involve various variables (e.g., Buck, Citation1991; Vandergrift & Goh, Citation2012). Consequently, research has been conducted on how listening is directly related to these variables (see a meta-analysis by In’nami et al., 2021; Karalık & Merç, Citation2019) and how such relationships are moderated (Wallace, Citation2020). The present study adds to this corpus of research by focusing on aspects of metacognitive awareness and by assessing the moderating effects of listening comprehension tests (which have different task types; task demands; and paper-based vs. computer-based formats) and samples of learners (2019 and 2020 cohorts) on the relationship between metacognitive awareness and listening comprehension. Researchers have found a positive relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness as a whole. However, it has not been clear whether and how such a relationship changes according to aspects of metacognitive awareness. Although a variety of listening tests exist, it is not clear how they impact the relationship between listening and metacognitive awareness. While a comparison of results across learners supports generalizability of the findings, research on this area remains sparse. Investigating these issues would further enhance our understanding of how L2 aural information is comprehended.

Literature Review

The relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness

The role of metacognitive awareness or “thinking about one’s thinking or the human ability to be conscious of one’s mental processes” (Vandergrift et al., Citation2006, pp. 432–433) has been examined in relation to L2 listening comprehension (e.g., Ghorbani Nejad & Farvardin, Citation2019; Goh & Hu, Citation2014; Vafaee & Suzuki, Citation2020; Wallace, Citation2020). According to Goh (Citation2008), metacognitive awareness related to listening includes person knowledge (e.g., one’s beliefs about listening), task knowledge (e.g., one’s understanding of the cognitive demands involved in listening), and strategy knowledge (e.g., one’s understanding of useful strategies depending on task types). These three aspects were based on Goh (Citation1997), who assessed the diaries of 40 learners of English, including information about what they did to enhance their understanding of listening in English. Content analysis of the diaries suggested that learners were conscious of the differences between these three aspects and the importance of using corresponding strategies. Further, using structural equation modeling, Vafaee and Suzuki (Citation2020) examined the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and vocabulary knowledge, syntactic knowledge, anxiety, working memory, and metacognitive awareness. It was found that the relationship between listening and all the variables was statistically significant. These results were consistent with Karalık and Merç (Citation2019) who conducted a meta-analysis that showed a moderate relationship between listening and metacognitive awareness (number of studies = 7, synthesized correlation = .54, p < .01, 95% confidence interval [CI]: .29 and .72). This was partially supported by another meta-analysis conducted by In’nami et al. (2021) which showed a weak relationship between the said factors (number of correlations = 24, synthesized correlation = .275, p < .01, 95% CI: .194 and .353). In contrast, Wallace’s (Citation2020) structural equation models examined the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and working memory, topical knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, and metacognitive awareness. It was found that instead of directly affecting listening, metacognitive awareness was related to listening through topical knowledge, suggesting that those with high conceptual knowledge about the topics highlighted in the listening passages tended to use more metacognitive strategies than the others, and thus that learners used top-down strategies to compensate for their failure to understand the passage. Altogether, researchers have found a positive relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness, although topical knowledge might affect this relationship.

Frequently, metacognitive awareness has been measured using the Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ; Vandergrift et al., Citation2006), which aims to measure “the extent to which language learners are aware of and can regulate the process of L2 listening comprehension” (Vandergrift et al., Citation2006, p. 432). Thus, while the questionnaire’s name only refers to awareness, it is designed to also measure one’s beliefs about listening and the ability to activate and control the mental processes involved in understanding L2 aural information. In the questionnaire, metacognitive awareness is operationalized by dividing it into: planning and evaluation (preparing for listening and assessing one’s understanding of the passage); directed attention (how to focus on and maintain one’s attention toward the task); person knowledge (one’s beliefs about listening relative to other skills such as reading); mental translation (translating [key] words as one listens); and problem solving (inferring the meaning of words; monitoring one’s understanding while listening). Vandergrift et al. (Citation2006) conducted a validation study of the MALQ and reported it as an appropriate indicator of metacognitive awareness of L2 listening (see also Goh, Citation2018). In’nami et al.'s (2021) meta-analytical study also showed a weak, positive relationship between metacognitive awareness measured by the MALQ and L2 listening (number of correlations = 6, synthesized correlation = 226, p < .01, 95% CI: .068 and .373).Footnote1

So far, research has found a positive relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness. However, the focus has largely been on metacognitive awareness as a whole. In contrast, research on the relationship between every aspect of metacognitive awareness in the MALQ and L2 listening comprehension has yielded mixed results (see ). For example, Goh and Hu (Citation2014) found that (a) person knowledge and (b) problem solving were significant predictors of listening comprehension in multiple regression. Vafaee and Suzuki (Citation2020) found that mental translation and problem solving did not load significantly on the metacognitive awareness factor and were removed from the model. The three metacognitive aspects retained in the model, that is, (a) person knowledge, (c) planning and evaluation, and (d) directed attention, significantly predicted listening comprehension. Aryadoust (Citation2015a) found that (b) problem solving and (c) planning and evaluation strategies were significant predictors of listening comprehension in the evolutionary algorithm-based symbolic regression. Aryadoust (Citation2015b) found that all strategies were significant predictors of listening comprehension in an artificial neural network analysis. Vandergrift and Baker (Citation2015) reported that (a) person knowledge was the only significant factor affecting listening when the three learner groups (2008, 2009 and 2010 cohorts) were analyzed together, whereas (b) problem solving or (d) directed attention was a significant factor affecting listening when the data of one of the three cohorts was analyzed separately. suggests that the relationship between L2 listening and metacognitive awareness varies across contexts and that some moderator variables affect this relationship. We focused on the moderating effects of the two variables of listening tests and learner samples.

TABLE 1. Previous studies on the relationships between MALQ metacognitive awareness and L2 listening comprehension

Effects of listening tests on the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness

It is important to investigate the effects of listening tests on the relationship between listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness. While listening tests differ in many respects, we review three that are related to the current study. First, constructs measured and task types may lead to different task demands and elicit different listening and test-taking strategies and processes, eventually affecting the relationship between metacognitive awareness and listening. Previous studies have examined learners’ test-taking processes or strategies in the context of listening tests that target different aspects of listening ability and include different tasks. For example, Wu (Citation1998) used a verbal protocol method to elicit the cognitive processes involved in answering paper-based, multiple-choice test items measuring literal and inferential understanding of passages, and found that when learners failed to understand the passage, they used non-linguistic general knowledge to compensate for their lack of understanding. Taguchi (Citation2001) used a questionnaire to measure strategies employed during a listening test that seemed to assess the literal understanding of passages. It was found that all the strategies – repair, affective, compensatory, and linguistic – were used by learners who attempted a paper-based listening test containing questions with two option (yes-no). Carrell (Citation2007) investigated how notetaking strategies affected the scores in a computer-based, multiple-choice L2 listening test, assessing literal and inferential understanding of passages. The results showed a moderate relationship between notetaking strategies and listening scores, wherein the number of words that directly corresponded with the answers and content words strongly correlated with the listening scores (r = .63 for answers; r = .49 for content words). Further, using eye-tracking and cued retrospective reporting, Suvorov (Citation2018) examined the aspects of visual information that examinees paid attention to in a video-mediated, multiple-choice L2 listening test, assessing literal and inferential understanding of passages. The results showed that learners focused on speaker-related (e.g., speaker’s body movements) and lecture-related (e.g., visual aids) information that helped them understand the passage. However, the information was also distracting if it was not explicitly related to the point the speaker was trying to make. These previous studies focused on listening strategies or processes involved in answering multiple-choice questions, but previous studies have also suggested that open-ended questions elicit different processes (Buck, Citation1991). In the context of the relationship between metacognitive awareness and L2 listening, shows that previous studies used either multiple-choice questions (Vandergrift & Baker, Citation2015) or a combination of multiple-choice and short-answer questions (the other studies in ).

Second, in addition to constructs measured and task types, another factor that could impact the relationship between metacognitive awareness and L2 listening is the availability of question preview opportunities. For example, IELTS allows examinees to preview questions before listening to a passage and answering the questions (British Council, Citation2021). Existing literature has documented that such a listening preview positively affects the results (Sherman, Citation1997). shows that Goh and Hu (Citation2014), Aryadoust (Citation2015a, Citation2015b), Vafaee and Suzuki (Citation2020), and Ghorbani Nejad and Farvardin (Citation2019) used tests that offered the learners an opportunity to preview questions. The positive and strong mediation of previewing on the relationship between L2 listening and metacognitive awareness may be attributed to the fact that it helps learners to understand the test and prepare for corresponding problem-solving activities (also see Field, Citation2019).

Finally, the third factor is the delivery mode of tests. With the advancement of Information and Communication Technology, it has become conventional to deliver tests on computers (e.g., Douglas & Hegelheimer, Citation2007). Coniam (Citation2006) compared the score of the two modes (i.e., computer-based and paper-based) of an L2 listening test and reported that learners performed better on computer-based tests than paper-based tests overall. shows that all previous studies have used paper-based tests. While the differences in test-taking processes have been examined across reading and writing test formats (e.g., Brunfaut et al., Citation2018; Sawaki, Citation2001), few studies have investigated listening. It can be assumed that listening scores and processes may not change as long as learners are comfortable using a computer, although this is something that it would be useful to examine in future studies.

We have reviewed the three factors that may be involved in understanding the relationship between metacognitive awareness and L2 listening. They are (a) constructs measured and task types, (b) the availability of question preview opportunities, and (c) the delivery mode of tests. The current study expands previous studies by investigating these three factors in two formats of TOEFL ITP and iBT tests.

Test of English as a Foreign Language Institutional Testing Program (TOEFL ITP®) test and TOEFL Internet-based Test (TOEFL iBT®)

The two formats of TOEFL tests share similarities and differences. First, regarding test constructs and task types, both use multiple-choice task types and play the listening passages only once. However, for the construct measured, the TOEFL ITP focuses on “the ability to understand spoken English … used in colleges and universities” (Educational Testing Service, Citation2021c). While the TOEFL iBT also measures this construct, it includes broader but more precisely defined constructs: “listening for: basic comprehension” and “pragmatic understanding (speaker’s attitude and degree of certainty) and connecting and synthesizing information” (Educational Testing Service, Citation2021d). Although both tests share the same target language use domain (i.e., listening comprehension of the English language used in tertiary education), the authenticity and demand of tasks in the TOEFL iBT are higher so as to better represent the construct and academic domain more lucidly. As summarized in , the TOEFL iBT administers fewer questions in a longer period of time, whereas the TOEFL ITP administers a larger number of questions in a shorter period of time. It can be assumed that using longer passages and fewer items may reflect the need to measure pragmatic, connecting, and synthesizing abilities.

TABLE 2. TOEFL ITP and iBT listening sections

Second, in terms of question preview, in the paper-based TOEFL ITP, multiple-choice options are presented in the test book before, while, and after the passage is played, while the questions are aurally presented (and not written in the test book) after the passage is played. While examinees can consider the options beforehand, comprehending them before and/or while the passage is played is not an easy task because of the limited time and cognitive resources. In contrast, multiple-choice options and questions are presented on the screen after the passage is played in the TOEFL iBT. To minimize the risk of losing track of the passage, examinees can strategically take notes to structure the content of the passage.

Third, the availability of the TOEFL iBT in a digital format compared to the paper-based TOEFL ITP may increase task demands unless learners are familiar with using computers.

Consequently, all these characteristics could make the TOEFL iBT more challenging than the TOEFL ITP. As little research has been conducted, it is not clear what aspects of metacognitive awareness of listening, as measured in the MALQ, are related to comprehension in each test.

Effects of learner samples on the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness

Another factor that affects the relationship between metacognitive awareness and L2 listening comprehension is learner samples. This is important as it ascertains generalizability or “the extent to which research results can justifiably be applied to a situation beyond the research setting” (Chalhoub-Deville, Citation2006, p. 3). As reviewed above, findings across studies have suggested that metacognitive awareness is positively related to listening comprehension. However, how each aspect of metacognitive awareness measured by MALQ affects this relationship has not been conclusive. Consequently, while existing literature suggests a strong generalizability of the relationship between L2 listening and metacognitive awareness, it suggests a weak generalizability of the relationship between L2 listening and each aspect of metacognitive awareness.

Previous studies have differed in many respects. As seen in , participants’ proficiency levels and learning settings were different. For example, Goh and Hu (Citation2014) and Vafaee and Suzuki (Citation2020) used IELTS listening test in EFL contexts, but their participants’ L1s (Chinese and Persian, respectively) and proficiency levels (slightly higher but less varied, as reported in Goh & Hu, Citation2014 [M = 24.58 out of 40; SD = 5.47], than Vafaee & Suzuki, Citation2020 [M = 19.86 out of 40; SD = 8.93]) differed. Therefore, it is challenging to identify the factor that is responsible for producing mixed results across studies regarding the importance of each aspect of metacognitive awareness.

This can be addressed by examining two groups of similar learners. Ercikan (Citation2009) argued that participants, construct definitions, measurements, and settings affect the generalizability of study findings. Consequently, if these conditions are similar, similar results are likely to be obtained. However, Vandergrift and Baker (Citation2015) assessed three cohorts with the same characteristics and reported different results. For one cohort, directed attention of metacognitive awareness was significantly related to listening, whereas for another cohort, problem solving was significant. When all the cohorts were combined, person knowledge emerged as significant. This suggests the effects of learner samples on the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness. The current study further examines this issue by assessing two cohorts and their responses to the same research instruments (i.e., the same definitions and measures of listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness) at the same university (i.e., the same settings). The results would provide further evidence of the stability of the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness.

Random forests

To examine the research questions as reported below, we used random forests. According to Strobl, Malley et al. (Citation2009), the random forest approach is an example of a recursive partitioning method for examining the relationships among variables. Variables can be categorical or continuous, and normal or nonnormal. Linear and nonlinear relationships among variables can be modeled. To obtain precise and stable results, the random forest uses bootstrapping. This means that a sample of data is drawn randomly and is used to examine the relationships between variables. This process is repeated and the results are averaged across runs to refine those results.

For example, in the current study (see below for details), we examined how five metacognitive strategies were related to L2 listening comprehension. It could be possible, for instance, that Strategy A was related to comprehension in Data 1, Strategies B and C related in Data 2, and Strategy D in Data 3. The results were tallied and averaged across runs to obtain accurate and stable findings.

Compared to the random forest method, multiple regression, which is often used in L2 studies (Plonsky & Ghanbar, Citation2018), typically examines a linear relationship among normally distributed, categorical or continuous variables by analyzing the whole data once (without bootstrapping). Thus, random forests allow researchers to take a more flexible approach to analyzing data while still being able to obtain precise and stable results across samples of simulated data sets.

Further, unlike regression, the order in which variables are entered into the model does not matter in random forests. We believe this is important because the way independent variables entered into the regression affects the results (see, for example, Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2014) but is not always reported. The issue is more serious when researchers have a large number of independent variable to model. It is not always easy to decide which variable to enter into the equation first. In random forests, all variables enter into the analysis simultaneously, and their importance can be interpreted more easily than regression. Collectively, these features of the random forest method make it an appealing approach to modeling relationships among variables, including those in the current study.

Research questions

Our review has shown two primary gaps in previous studies. First, researchers have found a positive relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness as a whole. However, it has not been clear whether and how such a relationship changes according to aspects of metacognitive awareness. Second, it remains to be examined whether and how listening tests and learners moderate the relationship. To fill these gaps, the current study examines the relationship between L2 listening and metacognitive awareness while focusing on aspects of metacognitive awareness and considering the moderating effects of listening tests (TOEFL ITP vs. iBT) and learner samples (two cohorts), neither of which have been rigorously compared in previous studies. The following two research questions were addressed:

1. How is the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness affected by different listening tests?

How Is the Relationship Affected by Different Samples of Learners?

The study is outlined in , with further information described in the Method section.

TABLE 3. Structure of the research

Method

Participants

Two groups of learners participated in the current study. The first group (the 2019 cohort) consisted of 75 English-as-a-foreign-language students at a Japanese private university majoring in medicine. They were 1st-year undergraduate students (aged 18 or above) enrolled in a preparation course for the TOEFL test. Their listening proficiency ranged from A2 to C1 (B1 on average), of the Common European Framework of Reference based on their TOEFL scores (see ) and Educational Testing Service (Citation2021a, Citation2021b). They had learned English for at least six years in secondary school before enrolling in the university. According to their instructors, the students routinely used computers inside and outside the classroom so their computer skills would not affect their performance on the computer-based tests. The students had had little experience taking computer-based tests.

TABLE 4. Descriptive statistics for the 2019 (n = 75) and 2020 Cohorts (n = 107)

The other learner group (the 2020 cohort) included 107 students from the same Japanese private university with the same major (medicine). They enrolled in the school in April 2020, a year after the 2019 cohort. The two cohorts differed only in the timing of their enrollment. According to the instructors who taught both cohorts, they had much in common in terms of academic achievement and did not demonstrate any noticeable differences. Further, there were no major changes in the educational policy in Japan implemented around this time. Thus, both cohorts were considered very similar, with three minor exceptions. First, the 2019 cohort took the TOEFL ITP and iBT, whereas the 2020 cohort only took the TOEFL ITP. Second, all courses, including the TOEFL preparation course, were delivered online due to the coronavirus outbreak for the 2020 cohort, whereas the 2019 cohort studied in the classroom. Third, the 2019 cohort took the TOEFL ITP twice an academic year–once in April and once in December. Their scores from December were analyzed. The 2020 cohort took the TOEFL ITP once–in September. They were not able to take it in April as it was in the midst of the pandemic. Their scores from September were analyzed. These three differences between the two cohorts arose due to logistical constraints that were beyond the researchers’ control.

Instruments and procedures

One or two measures of listening proficiency and one measure of metacognitive awareness were administered. For the former, the 2019 cohort took the paper-based TOEFL ITP Level 1 and the TOEFL iBT. Both tests were conducted annually as part of the quality assurance effort of the university. The TOEFL ITP was administered in December 2019. As for the TOEFL iBT, participants were required to take it between September and December 2019 and submit their scores to the department in December 2019. More than 95% of them submitted their scores from the November slot. Thus, the impact of the timing of taking the test was considered minimal. The 2020 cohort attempted the TOEFL ITP Level 1 in September 2020. As the current study focused on listening, participants’ listening section scores were used.

Metacognitive awareness of L2 listening was measured using the MALQ (Vandergrift et al., Citation2006). Although the original version by Vandergrift et al. was written in English, we used the Japanese version developed by Wallace (Citation2018) after revising it slightly and cross-checking and piloting it so as to facilitate the understanding of participants. The MALQ consisted of 21 six-point-scale items (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree) to measure person knowledge (3 items [including 2 negatively-worded items]), mental translation (3 items [including 3 negatively-worded items]), directed attention (4 items [including 1 negatively-worded item]), problem solving (6 items), and planning and evaluation (5 items). Some examples are presented below (first item of the five aspects of metacognitive awareness each):

No. 1 (Planning and evaluation): Before I start to listen, I have a plan in my head for how I am going to listen.

No. 2 (Directed attention): I focus harder on the text when I have trouble understanding.

No. 3 (Person knowledge): I find that listening in French is more difficult than reading, speaking, or writing in French. (negatively worded)

No. 4 (Mental translation): I translate in my head as I listen. (negatively worded)

No. 5 (Problem-solving): I use the words I understand to guess the meaning of the words I don’t understand.

Following the MALQ Scoring and Interpretation Guide (n.d.), Goh (Citation2008), and Wallace (Citation2020), negatively-worded items (i.e., item numbers 3, 4, 8, 11, 16, and 18) were reverse coded so that a high value indicated a favorable response corresponding with the remaining items. Items were presented as they appeared in Vandergrift et al. (Citation2006). The MALQ was administered online between December 2019 and January 2020 for the 2019 cohort and in July 2020 for the 2020 cohort.

Analyses

The data comprised TOEFL ITP listening section scores, TOEFL iBT listening section scores, and MALQ section scores grouped according to the aspects (i.e., subcomponents) of metacognitive awareness. MALQ section scores were the sums of the responses for the items measuring a particular aspect of metacognitive awareness. For example, person knowledge was measured using three items. The responses for these items were summed, and a maximum score of 18 was obtained (6 points × 3 items).

Descriptive statistics were obtained using the psych package (Revelle, Citation2020) in R. The data were then analyzed using random forests in the party package (Hothorn et al., Citation2021) in R, following the recommendation of Strobl, Hothorn et al. (Citation2009). The random forests’ results were interpreted using variable importance values (which show the relative importance of independent variables in relation to a dependent variable) and partial dependence plots (which show the pattern of such a relationship). Partial dependence plots were drawn using the pdp package (Greenwell, Citation2018) in R.

Based on Strobl, Hothorn et al. (Citation2009), we selected the party package for two reasons. First, it can address the bias that arises due to the differences in the number of items for each variable, ranging from person knowledge (6 points x 3 items = 18 points) to problem solving (6 points x 6 items = 36 points). Otherwise, variance importance values are overestimated favoring predictor variables with higher full marks; in other words, problem solving might have a larger variance importance value than person knowledge simply because it had more items. Second, the party package can adjust the bias toward variable importance values when a predictor variable is not correlated with an outcome variable by itself and is correlated only through another predictor variable. Further, we confirmed that the order of the importance of variables stayed the same when different random seed values were used.Footnote2 Supplementary material is available at https://osf.io/hnvr8/.

Results

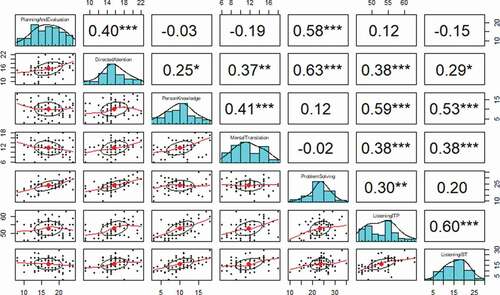

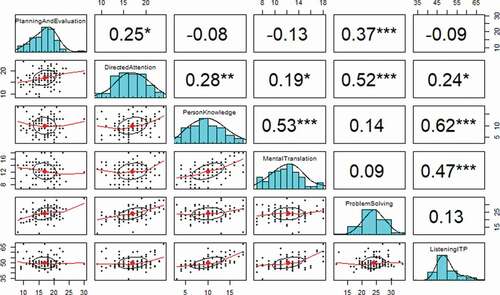

The descriptive statistics are presented in . All instruments (and their subsections) displayed a wide range of values, suggesting a broad distribution of scores. The reliability estimates for the MALQ were acceptable (.756 and .793 for the 2019 and 2020 cohorts, respectively), whereas those for its subsections varied (from .530 for the 2020 planning and evaluation section to .812 for the 2019 person knowledge section). As show, person knowledge strongly correlated with the two listening tests (r = .59 and .53 for the 2019 cohort; .62 for the 2020 cohort). Patterns of correlations between the variables of metacognitive awareness were similar to Vandergrift et al. (Citation2006). For example, there was a moderate relationship between directed attention and problem solving (r = .63 for the 2019 cohort; r = .52 for the 2020 cohort; and .57 in Vandergrift et al., Citation2006, p. 446). While were presented for comparison with previous studies, the current study focuses on the results of random forests for interpretation due to the advantages it offers (see the Random Forests section above).

Figure 1. Correlations Among the Variables for the 2019 Cohort

Figure 2. Correlations Among the Variables for the 2020 Cohort

Variable importance scores are presented in and . Higher positive values indicate the increasing importance of variables. Values close to or less than zero signify the nonimportance of variables, reflecting random fluctuation (Strobl, Malley et al., Citation2009). From the 2019 TOEFL ITP listening scores, person knowledge had the highest positive importance score (5.83), suggesting that it was the strongest correlate of the listening score. This was followed by mental translation (0.27), directed attention (0.13), and planning and evaluation (0.04). Problem solving had a negative importance value (−0.01), suggesting that it was not associated with the listening score. From the 2019 TOEFL iBT listening scores, person knowledge (7.45), mental translation (2.15), and directed attention (0.35) had positive importance scores. In contrast, planning and evaluation (−0.25) and problem solving (−0.13) had negative importance scores. From the 2020 TOEFL ITP listening scores, person knowledge (14.02) was the only variable whose importance value was located outside the other negative values, that is, the importance values of directed attention (0.17) and mental translation (0.19) were positive but less than 0.25, the absolute value of −0.25 in problem solving. This suggests that directed attention and mental translation were not associated with the listening score.

TABLE 5. Variable importance score for the five aspects of metacognitive awareness of L2 listening

Figure 3. Variable Importance Scores for the Five Aspects of Metacognitive Awareness of L2 Listening

To better understand the nature of the relationship between the aspects of metacognitive awareness and listening test scores, depicts partial dependence plots. (top panel) shows that from the 2019 listening ITP scores, planning and evaluation, directed attention, person knowledge, and mental translation – the four major correlates in – were linearly related to the listening scores. According to (middle panel), such a linear relationship was also found for the 2019 listening iBT scores. The uses of directed attention, person knowledge, and mental translation – the three major correlates in – were directly proportional to the listening scores. Finally, the bottom panel of (bottom panel) shows that for the 2020 listening ITP score, person knowledge – the only major correlate in – demonstrated a linear relationship with the listening score.

Figure 4. Partial Dependence Plots for the Five Aspects of Metacognitive Awareness of L2 Listening

Discussion

Research Question 1: Relationships across listening tests

To better understand how different listening tests affect the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness, a group of students took a listening test in two formats (TOEFL ITP vs. iBT). As summarized in , results showed that, in order of importance, person knowledge, mental translation, and directed attention were related to listening comprehension in both formats. Planning and evaluation strategies were related to listening comprehension only in the TOEFL ITP.

TABLE 6. Summary of results: Metacognitive awareness of L2 listening in order of importance of affecting L2 listening comprehension

In both formats, person knowledge, that is, one’s beliefs about listening, was most strongly related to listening comprehension. Higher, positive values of person knowledge after reverse coding indicate that learners find listening in English easier than reading, speaking, or writing in English. Such learners tend to feel that English listening comprehension is not as challenging for them and not to feel nervous while attempting listening tests. These strategies reflect learners’ higher self-perceived listening ability and greater confidence in listening. As shown in , the mean scores of the current learners were neither high nor low (56.06% and 55.67%). The consistent relationship between person knowledge and listening across the listening tests seem to suggest that learners’ positive beliefs or greater confidence in their listening ability are related to listening comprehension, a finding which corroborates previous studies.

More specifically, Taguchi (Citation2001) and Wu (Citation1998) found that students who are less confident in listening faced great difficulty in processing aural information. For example, if they lost track, then it was difficult for them to catch up due to the fast speed rate of the text. Goh (Citation1997) reported that successful listeners had positive attitudes toward listening and understood the importance of using appropriate strategies. Our results show that, just like in paper-based tests, person knowledge emerged as an important factor in computer-based test that assesses broader but more precisely defined constructs of listening. As reported in , previous studies have also found a constant relationship between person knowledge and listening. However, unlike other studies, Aryadoust (Citation2015a) used an evolutionary algorithm-based symbolic regression that does not assume linearity between variables and found that a constant relationship did not occur between person knowledge and listening. Different methods of examining relationships and other possible factors should be considered in further explorations.

Further, after person knowledge, mental translation was the second most strong aspect related to listening comprehension. Higher positive values of mental translation after reverse coding indicate that listeners did not mentally translate keywords or other words as they listened. This strategy reflects the avoidance of mental translation and presence of automatic recognition and processing of auditory information leading to a quick comprehension of the listening passage. This corresponds with previous studies that have reported on the debilitating effect of mental translation on comprehension and observed this strategy among low-proficient learners. (e.g., Goh & Hu, Citation2014). The role of automatic recognition and processing of auditory information could be even more prominent for computer-based tests, such as TOEFL iBT, where cognitive demands of listening tasks (e.g., multiple-choice options and questions are presented on the screen after the passage is played; connecting and synthesizing abilities are tested using long passages) are heavier than those in paper-based tests. In fact, mental translation had a higher importance value in the TOEFL iBT than TOEFL ITP (0.27 for the TOEFL ITP; 2.15 for the TOEFL iBT; see ), suggesting that the avoidance of mental translation plays a more important role in computer-based tests with higher cognitive demands than in paper-based tests with less heavy demands.

Directed attention was related to listening comprehension in both tests, albeit to a lesser degree. It refers to strategies such as paying more attention to the text when it is difficult to understand; in other words, working harder to regain concentration. These strategies signify the importance of focusing on the aural input and regulating attention even under difficult circumstances. This importance was observed in both TOEFL iBT and TOEFL ITP.

Problem solving was not related to listening comprehension in either of the tests. It signifies strategies to infer the meaning of words from context and monitor whether one’s understanding of the passage is correct compared to one’s background knowledge or experience. While these should have appeared as significant in both tests, the reason for their absence was not clear. One reason could be that participants who used problem solving were occupied with this activity and missed essential incoming information related to the answers (Ridgway, Citation2000).

Planning and evaluation strategies were related to listening comprehension only in the TOEFL ITP. Planning signifies that a listener prepares themselves to listen beforehand – planning takes place before and during listening. Evaluation signifies whether one’s understanding of the passage is satisfactory and how one might improve one’s listening skills – evaluation takes place during and after listening. The absence of these factors in the TOEFL iBT could be explained by students’ inexperience in attempting computer-based tests. As they take more tests, they might use planning and evaluation strategies in computer-based tests as well as in paper-based tests. As this process continues, their strategy use may gradually relate to listening comprehension in computer-based tests as well.

However, the presence of question preview may alter the relationship between planning and evaluation and problem solving strategies in computer-based tests because the opportunity to preview questions allows learners to prepare their cognitive resources and use them more efficiently. Question preview may facilitate a learner’s discerning the meaning of unfamiliar words by referring to information extracted from their topical knowledge that is activated before listening commences (i.e., effective use of problem solving). Further, such learners may plan ahead and set a clear goal before listening, and handle listening tasks better. As mentioned above, the TOEFL iBT does not provide question preview and the TOEFL ITP does not allot additional time to read the questions; therefore, it is unlikely that this strategy was employed by the learners. In , of the five studies that allowed question preview (Aryadoust, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Ghorbani Nejad & Farvardin, Citation2019; Goh & Hu, Citation2014; Vafaee & Suzuki, Citation2020), three (Aryadoust, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Goh & Hu, Citation2014) reported a relationship between problem solving and listening, while three (Aryadoust, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Vafaee & Suzuki, Citation2020) reported a relationship between planning and evaluation strategies and listening, whereas studies without a listening preview did not find such relationships. Further research may be needed in terms of how question preview affects the relationship between planning and evaluation strategies and listening. Finally, the three differences observed in the introductory section sufficiently explain the subtle differences in the results of the current study and previous studies.

Research Question 2: Relationships across cohorts

As for Research Question 2 regarding how the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness was affected by different samples of students, two cohorts (2019 and 2020 cohorts) took the same listening test. In , the results from the 2019 cohort showed that, in order of importance, metacognitive strategies of person knowledge, mental translation, directed attention, and planning and evaluation were related to listening. Results from the 2020 cohort showed that only person knowledge was related to listening comprehension. Problem solving was not related in either of the samples.

Observing the relationship between listening comprehension and person knowledge across the two cohorts suggests the generalizability of such a relationship beyond the study’s setting. Among the five aspects of metacognitive awareness of listening, person knowledge was stably related to listening comprehension across groups of students. However, this does not corroborate Vandergrift and Baker (Citation2015), who observed different strategies as being significant across cohorts and when they were analyzed together. The combined results from the current and previous studies seem to suggest that the relationship between listening comprehension and person knowledge is robust in some contexts.

Strategies other than person knowledge were not related to listening comprehension for the 2020 cohort (planning and evaluation, directed attention, and mental translation) and problem solving was not significant for either of the cohorts. This could be explained by two reasons. First, the 2020 cohort took the test for the first time and could not afford to relate metacognitive strategies with listening, as their mental resources were focused on answering the questions. Their instructors commented that although most students took the listening tests for university entrance examinations, they tended to feel perplexed with the TOEFL ITP, in which the audio was played only once, in contrast to Japanese university entrance exams where the audio was typically played twice (i.e., the National Center Test for University Admissions; see Yanagawa, Citation2012).

Second, the timing of the administration of the MALQ may have influenced the results related to strategies other than person knowledge. The 2019 cohort completed the MALQ in the second semester (December–January) and the 2020 cohort completed it in the first semester (in July). According to their instructors, students tended to take lessons less seriously in the second semester, as they got used to the university lifestyle. This suggests that the 2019 cohort’s responses to the MALQ might not fully reflect their perception of metacognitive awareness.

In sum, consistently observing the relationship between listening comprehension and person knowledge across two cohorts suggests the robustness of such a relationship, indicating its strong generalizability across learners. In contrast, different results of planning and evaluation, directed attention, and mental translation, despite many aspects shared by the two cohorts (with minor differences across the groups), suggest weak generalizability of the relationship between these strategies and listening comprehension.

Conclusion

Research has shown that metacognitive awareness is positively related to L2 listening comprehension, wherein successful listeners employ various strategies to address the cognitive demands of the incoming aural information (e.g., Goh & Hu, Citation2014; Vandergrift et al., Citation2006). The current study extended this line of research by focusing on aspects of metacognitive awareness and by examining how this relationship is moderated by (a) listening comprehension tests (e.g., eliciting broadly defined constructs, using more demanding listening situations and a computer-based method) and (b) samples of learners. As for the effects of listening tests, three aspects of metacognitive awareness (i.e., person knowledge, [the avoidance of] mental translation, and directed attention) were related to listening comprehension in both tests. Problem solving was not related in either test. Regarding the effects of learner samples, person knowledge was consistently related to listening comprehension, suggesting a strong generalizability of the findings across learners. In contrast, other aspects of metacognitive awareness were inconsistently related to listening comprehension. This suggested their weak generalizability. Consequently, the relationship between L2 listening comprehension and metacognitive awareness is moderately and highly affected by (a) listening comprehension tests and (b) learner samples, respectively.

However, the current study has certain limitations. First, we only used a questionnaire to assess metacognitive awareness. According to Vandergrift and Baker (Citation2015), questionnaires only assess learners’ perceptions and not their actions; therefore, questionnaire data may not completely reflect their behaviors. Future research must employ other measures, such as eye-tracking techniques. This technique can be used to examine a listener’s gaze behavior, as it indicates how metacognitive strategy unfolds. Low and Aryadoust (Citation2021) found that listeners’ gaze behavior was moderately related to their responses to the questionnaire and recommended researchers use gaze behavior rather than questionnaires. As the results of both methods differ (e.g., see Bax, Citation2013), it would be better to use them complementarily to measure listeners’ metacognitive awareness. Second, even with multiple measures, it might be challenging to assess metacognitive awareness because its use may depend on the task that learners are engaging with. This is an interactionalist perspective (Bachman, Citation2006) of understanding metacognitive awareness, whereas the MALQ measures metacognitive awareness without any reference to particular tasks. This is a trait perspective (Bachman, Citation2006). Metacognitive awareness could be better assessed by specifying contextual factors and using other methods such as verbal protocol along with questionnaires. Moreover, other variables should be examined that are not only directly associated with listening but also moderate the relationship between metacognitive strategies and listening (see Wallace, Citation2020).

For pedagogical implications, our findings could help teachers better understand the relationship between L2 listening and metacognitive awareness across listening tests and learner groups. Following Vandergrift et al.’s (2006) instructional advice, teachers could focus on teaching metacognitive strategies that are more strongly related to listening (e.g., person knowledge). Doing so could help learners identify their strengths, weaknesses, goals, and actions in relation to listening comprehension.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) Grant No. 20K00781 and the Juntendo University General Education Joint Research Grant.

Disclosure Statement

The authors reported no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The In’nami et al.'s meta-analysis used correlations that had been collected before the current study was conducted. Thus, the meta-analysis did not include the current study. In case readers are interested in what the correlations looked like between metacognitive awareness and L2 listening comprehension in the current study, the correlations between the TOEFL ITP listening (paper) and the MALQ were r = .54 (2019 data) and .42 (2020 data). The correlation between the TOEFL iBT listening (computer) and the MALQ was r = .37 (2019 data). All correlations were statistically significant, p < .01.

2. Following a reviewer’s suggestion, we conducted factor analysis separately on the 2019 and 2020 data to examine whether the five-factor structure of the MALQ (supported in Vandergrift et al., Citation2006) was supported as well in the current study. The results for the 2019 data showed that the matrix was not positive definite. This seemed to be due to the model-implied correlation matrix of the latent variables: The (standardized) correlation between directed attention and problem solving was 1.047. To address the not positive definite matrix, the ridge option in the lavaan package was used (Rosseel, Citation2012). However, the matrix was still not positive definite. Thus, we were not able to examine the factor structure of the MALQ for the 2019 data. In case readers are interested, the results–which were questionable and should not be interpreted–showed that the model fit the data poorly (comparative fit index [CFI] = .736, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.084 [90% confidence interval = 0.065, 0.103], standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = .108). As for the 2020 data, the results showed that the model fit the data poorly (CFI = .661, RMSEA = 0.089 [0.074, 0.104], SRMR = .108). In sum, the factor structure of the MALQ could not be tested in the 2019 data; it was not supported in the 2020 data. Thus, the findings from the study may need to be interpreted with caution. It is also worth noting that it was not clear whether these results–not confirming the five-factor structure–were specific to the current data sets. This was particularly because, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, little research has been conducted on the factor structure of the MALQ since it was developed in Vandergrift et al. (Citation2006). One exception is Wallace (Citation2020), which reported on the removal of the mental translation items from his model as they loaded weakly on the metacognitive strategy factor. This suggests that mental translation strategy is not explained by a common ability that underlies planning and evaluation, directed attention, person knowledge, and problem solving. This further suggests the need to examine to what extent Vandergrift’s et al. five-factor model holds across studies.

References

- Aryadoust, V. (2015a). Application of evolutionary algorithm-based symbolic regression to language assessment: Toward nonlinear modeling. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 57(3), 301–337.

- Aryadoust, V. (2015b). Fitting a mixture Rasch model to English as a Foreign language listening tests: The role of cognitive and background variables in explaining latent differential item functioning. International Journal of Listening, 15(3), 216–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15305058.2015.1004409

- Bachman, L. F. (2006). Generalizability: A journey into the nature of empirical research in applied linguistics. In M. Chalhoub-Deville, C. A. Chapelle, & P. Duff (Eds.), Inference and generalizability in applied linguistics: Multiple perspectives (pp. 165–207). John Benjamins.

- Bax, S. (2013). The cognitive processing of candidates during reading tests: Evidence from eye-tracking. Language Testing, 30(4), 441–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532212473244

- British Council. (2021). IELTSTM: Listening practice tests. https://takeielts.britishcouncil.org/take-ielts/prepare/free-ielts-practice-tests/listening

- Brunfaut, T., Harding, L., & Batty, A.-O. (2018). Going online: The effect of mode of delivery on performances and perceptions on an English L2 writing test suite. Assessing Writing, 36, 3–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2018.02.003

- Buck, G. (1991). The testing of listening comprehension: An introspective study. Language Testing, 8(1), 67–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/026553229100800105

- Carrell, P. (2007). Notetaking strategies and their relationship to performance on listening comprehension and communicative assessment tasks (ETS Research Report No. RR-07-01, TOEFL Monograph No. MS-35). Educational Testing Service. https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/RR-07-01.pdf

- Chalhoub-Deville, M. (2006). Drawing the line: The generalizability and limitations of research in applied linguistics. In M. Chalhoub-Deville, C. A. Chapelle, & P. Duff (Eds.), Inference and generalizability in applied linguistics: Multiple perspectives (pp. 1–5). John Benjamins.

- Coniam, D. (2006). Evaluating computer-based and paper-based versions of an English-language listening test. ReCALL, 18(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344006000425

- Douglas, D., & Hegelheimer, V. (2007). Assessing language using computer technology. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 115–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190508070062

- Educational Testing Service. (2017). TOEFL ITP test taker handbook. https://www.ets.org/s/toefl_itp/pdf/toefl_itp_test_taker_handbook.pdf

- Educational Testing Service. (2019). TOEFL iBT free practice test. https://www.ets.org/s/toefl/free-practice/start.html

- Educational Testing Service. (2021a). Comparing scores. https://www.ets.org/toefl/score-users/scores-admissions/compare/

- Educational Testing Service. (2021b). Research. https://www.ets.org/toefl_itp/research/

- Educational Testing Service. (2021c). Test content. https://www.ets.org/toefl_itp/content

- Educational Testing Service. (2021d). TOEFL iBT® Listening section. https://www.ets.org/toefl/test-takers/ibt/about/content/listening

- Educational Testing Service. (2021e). TOEFL iBT® test content. https://www.ets.org/toefl/test-takers/ibt/about/content

- Ercikan, K. (2009). Limitations in sample-to-population generalizing. In K. Ercikan & W.-M. Roth (Eds.), Generalizing from educational research: Beyond qualitative and quantitative polarization (pp. 211–234). Routledge.

- Field, J. (2019). Rethinking the second language listening test: From theory to practice. (British Council Monographs Vol. 2). Equinox Publishing.

- Ghorbani Nejad, S., & Farvardin, M. T. (2019). Roles of general language proficiency, aural vocabulary knowledge, and metacognitive awareness in L2 learners' listening comprehension. International Journal of Listening Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2019.1572510

- Goh, C. (1997). Metacognitive awareness and second language listeners. ELT Journal, 51(4), 361–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/51.4.361

- Goh, C. C. M. (2008). Metacognitive instruction for second language listening development: Theory, practice and research implications. RELC Journal, 39 (2), 188–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688208092184

- Goh, C. C. M. (2018). Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ). In D. Worthington & G. D. Bodie (Eds.) The sourcebook of listening research: Methodology and measures (pp. 430–437). Wiley Blackwell.

- Goh, C. C. M., & Hu, G. W. (2014). Exploring the relationship between metacognitive awareness and listening performance with questionnaire data. Language Awareness, 23 (3), 255–274. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2013.769558

- Greenwell, B. M. (2018). pdp: Partial Dependence Plots (Version 0.7.0) [Software]. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pdp/pdp.pdf

- Hothorn, T., Hornik, K., Strobl, C., & Zeileis, A. (2021). party (Version 1.3-6) [Software]. Retrieved from. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/party/party.pdf

- In’nami, Y., Koizumi, R., Jeon, E.-H., & Arai, Y. (manuscript in preparation). L2 listening and its correlates: A meta-analysis. In E.-H. Jeon & Y. In'nami (Eds.), Understanding L2 proficiency: Theoretical and meta-analytic investigations, John Benjamins

- Jin, Y. (2010). College English education in China: From testing to assessment. In Y.-I. Moon & B. Spolsky (Eds.), Language assessment in Asia: Local, regional or global? (pp. 1–27). Asia TEFL. http://www.asiatefl.org/main/main.php?main=3

- Karalık, T., & Merç, A.(2019). Correlates of listening comprehension in L1 and L2: A meta-analysis. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(3), 353–383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.32601/ejal.651387

- Low, A. R. L., & Aryadoust, V. (2021). Investigating test-taking strategies in listening assessment: A comparative study of eye-tracking and self-report questionnaires. International Journal of Listening. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2021.1883433

- Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ) Scoring and Interpretation Guide. (n.d.). [ Unpublished manuscript].

- Plonsky, L., & Ghanbar, H. (2018). Multiple regression in L2 research: A methodological synthesis and guide to interpreting R2 values. Modern Language Journal, 102(4), 713–731. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12509

- Revelle, W. (2020). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research (Version 2.0.12) [Software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

- Ridgway, T. (2000). Listening strategies—I beg your pardon? ELT Journal, 54(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/54.2.179

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Sawaki, Y. (2001). Comparability of conventional and computerized tests of reading in a second language. Language Learning and Technology, 5(2), 38–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.125/25127

- Sherman, J. (1997). The effect of question preview in listening comprehension tests. Language Testing, 14(2), 185–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/026553229701400204

- Strobl, C., Hothorn, T., & Zeileis, A. (2009). Party on! A new, conditional variable importance measure for random forests available in the party package. The R Journal, 1(2), 14–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2009-013

- Strobl, C., Malley, J., & Tutz, G. (2009). An introduction to recursive partitioning: Rationale, application, and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging, and random forests. Psychological Methods, 14(4), 323–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016973

- Suvorov, R. (2018). Test takers’ use of visual information in an L2 video-mediate listening test. In G. J. Ockey & E. Wagner (Eds.), Assessing L2 listening: Moving towards authenticity (pp. 145–160). John Benjamins.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2014). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Taguchi, N. (2001). L2 learners’ strategic mental processes during a listening test. JALT Journal, 23(2), 176–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTJJ23.2-1

- Vafaee, P., & Suzuki, Y. (2020). The relative significance of syntactic knowledge and vocabulary knowledge in second language listening ability. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(2), 383–410. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263119000676

- Vandergrift, L., & Baker, S. (2015). Learner variables in second language listening comprehension: An exploratory path analysis. Language Learning, 65(2), 390–416. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12105

- Vandergrift, L., & Goh, C. C. M. (2012). Teaching and learning second language listening: Metacognition in action. Routledge.

- Vandergrift, L., Goh, C. C. M., Mareschal, C., & Tafaghodtari, M. H. (2006). The metacognitive awareness listening questionnaire (MALQ): Development and validation. Language Learning, 56(3), 431–462. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2006.00373.x

- Wallace, M. P. (2018). Second language listening comprehension: Relationships among vocabulary knowledge, topical knowledge, metacognition, and working memory [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University. http://hdl.handle.net/10497/20331

- Wallace, M. P. (2020). Individual differences in second language listening: Examining the role of knowledge, metacognitive awareness, memory, and attention. Language Learning. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12424.

- Wang, Y., & Treffers-Daller, J. (2017). Explaining listening comprehension among L2 learners of English: The contribution of general language proficiency, vocabulary knowledge and metacognitive awareness. System, 65, 139–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.12.013

- Wu, Y. (1998). What do tests of listening comprehension test?―A retrospection study of EFL test-takers performing a multiple-choice task. Language Testing, 15(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/026553229801500102

- Yanagawa, K. (2012). A partial validation of the contextual validity of the Centre listening test in Japan [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Bedfordshire. http://hdl.handle.net/10547/267493