ABSTRACT

This article presents a developmental ecological approach to the emergence and development of metaphor in children, based on the ecological psychology tradition following the work of J.J. Gibson, and its extension into developmental research and theory, as developed by E.J. Gibson and others. This framework suggests that a basic compatibility and meaningfulness exists between the knower and the known, based on the direct perception of affordances. To build an ecological understanding of metaphor we need to clarify how this metaphysical ground plays out in acts of knowing that involve metaphor. In this endeavor, it is important to understand the ontogenesis of novel insightful metaphors and the role of perception. Developmental ecological psychology has repeatedly shown that infants can perceive meta-modal invariants that specify persistence of qualities. Early metaphors are consequences of the process in which invariants over naturally occurring kinds are perceived. Thus, novel metaphor production is an act of situated and experience-dependent perceiving and acting in the ecological world of socially shared meanings. Examples from previous experimental and qualitative research are reviewed to substantiate theoretical claims.

Introduction: The 4 Es and the ecological “E”

Recent changes in cognitive science have come to be characterized as the “E-turn,” marked by the “4 Es,” which claim that cognition is embodied, embedded, enacted, and extended (see, e.g., Chemero, Citation2011; Gallagher, Citation2017; Menary, Citation2010; Newen, De Bruin, & Gallagher, Citation2018; Noë, Citation2009; Thompson, Citation2007). These terms refer to differing aspects of the the general idea that cognition is shaped and structured by dynamic interactions between the brain, body, and the physical and social environment. In fact, there is another important “E,” standing for ecological. Rietveld, Denys, and Van Westen (Citation2018) have also remarked the importance of the “ecological E”; they, however, treat it in an additive way, as a missing fifth E. Here I suggest that it is not a fifth, but rather, a more fundamental, overarching “E” that serves to ground the 4 Es.

“Ecological” may mean, however, different things to different people. In this article the term will be used in a mutualist sense, referring to the distinctive level of the organism as an organized whole, in relation to its environment (e.g., Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949; Gibson, Citation1979; Read & Szokolszky, Citation2018; Still & Good, Citation1992, Citation1998). Ecological theories (at least since von Bertalanffy, Citation1938) take integrated living wholes, functioning as dynamic open systems as the starting point of explanation. The existence of the organism is grounded in a ceaseless flow of matter and energy exchange with its surroundings, which grounds persistence of its identity as a whole.

Basic ecological terms are often used in a non-mutualist sense even in biology. In Neo-Darwinian theory, for example, “ecological niche” is treated in a non-mutualist way, as existing prior to the organism that “fills” it in (cf. Ingold, Citation1992). In psychology, “ecological” has often been used to emphasize the importance of naturalistic observation, or embeddedness in sociocultural context. In current mainstream developmental psychology, the ecological label is often associated with Urie Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological view of human development (e.g., Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006; Rosa & Tudge, Citation2013). This approach has done much to emphasize the importance of studying development in ecologically valid settings, defined as micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems. It has not articulated, however, an ecological stance on ontology and epistemology, and, therefore, is mute on perception, action, and cognition.

An ecological metatheory presumes a symbiotic relationship between the environment and an agent who is actively seeking out and realizing novel functional relations, and therefore is constantly changing the functional environment, as well as being changed by this environment (see Shaw, Turvey, & Mace, Citation1982, Mace, Citation2005; Turvey, Shaw, Reed, & Mace, Citation1981; Witherington & Heying, Citation2013). Instead of interactionism, mutualism refers to the principle of organism (animal or human) and environment being mutually defined relational aspects of one another. At the ecological level, the environment is not the physical environment that surrounds us but the effective environment that has functional significance for an active agent (cf. Gibson, Citation1979). Niches coemerge with organisms (Jablonka & Lamb, Citation2014; Kauffman, Citation2013). In the case of humans, the functional environment means an environment sculpted by sociocultural practices (Costall, Citation1999, Citation2004; Heft, Citation2001, Citation2013; Rietveld & Kiverstein, Citation2014). We are “at home,” fundamentally, in this world, right from the moment we exist, although we need to go through a lot of development and sophistication to become enculturated members of the human world.

“Ecological” in the above sense incorporates embodiment, embeddedness, enaction, and extended cognition. Acknowledging this, there is further room to articulate what an ecological–mutualist stance has to offer for the theory and research on metaphors.

Goals and structure of the article

The goal of this article is to present an ecological approach to metaphor as a developmental–perceptual process, rooted in the ecological psychology (EP) tradition following the work of J.J. Gibson (e.g., Citation1966, Citation1979), and its extension into developmental research and theory (DEP), as developed by E.J. Gibson and others (e.g., Gibson, Citation1969, Citation1966, Citation1997; Gibson & Pick, Citation2000). DEP is a well-established framework, which is, nevertheless, still seeking ways to pursue and apply the principles related to organism–environment mutuality existing over time and in all settings of development (cf. Read & Szokolszky, Citation2018; Szokolszky & Read, Citation2018).

A profoundly ecological metatheory must be based on ecological ontology and ecological epistemology. Whether being or knowing is the issue, there must be no gap between “knowing and the known,” to cite the title of Dewey’s and Bentley’s famous work published in Citation1949 .EP, along with its extension into development, is a well-articulated school of thought that offers an elaborate framework of ecological ontology and epistemology. This approach has became an early pioneering and influential alternative to Cartesian psychology. This theory has been an inspiration to radically embodied theories and research as well (Chemero, Citation2011; Marsh, Johnston, Richardson, & Schmidt, Citation2009; Michaels & Palatinus, Citation2014; Van Den Herik, Citation2018), but also to a distinct ecological developmental approach to metaphor (Dent, Citation1984, Citation1987, Citation1990; Dent-Read, Citation1997; Dent-Read, Klein, & Eggleston, Citation1994; Dent-Read & Szokolszky, Citation1993; Read & Szokolszky, Citation2016). In this article, I will advance the latter approach, using concepts and ideas from EP, DEP, and enactive-embodied cognitive science.

Conceptual metaphor theory was important in the development of the embodied mind because it presented an alternative to a view on cognition as mainly symbolic manipulations by demonstrating the role of embodiment in basic metaphors and their role in constituting abstract concepts. “Image schemas” (such as “path,” “container,” etc.) were shown to root in recurrent structures of real time bodily experiences (such as moving forward or backward, or being inside or outside). Although current metaphor theories are heterogenious (cf. Kövecses, Citation2011, Citation2013), today it is accepted that conceptual metaphors (such as TIME IS MOTION, or LOVE IS HEAT, cf. Kövecses, Citation2010) are not just linguistic tools but an essential part of the embodied conceptual system.

More recently, there has been a turn toward an enactive and socially constituted view of conceptual metaphors and the acknowledgment of a more general presence of metaphoricity in human interactions (Gallagher & Lindgren, Citation2015; Gibbs & Cameron, Citation2008; Jensen, Citation2016; Jensen & Cuffari, Citation2014; Müller & Tag, Citation2010). The developmental ecological view to metaphor has clear affinities and conceptual overlap with these approaches, but it also suggests distinct ideas related to metaphor development that will be elaborated in this article.

A developmental approach is not just another viewpoint but a source of a more profound genetic understanding of “where things come from” and how they develop. Currently, however, developmental thinking is weakly represented in theorization and research within the embodied research on metaphor. Developmental work on metaphor was quite abundant in the 1980s, phrased in the framework of the cognitive paradigm (e.g., Billow, Citation1975, p. 981; Gardner, Kirchner, Winner, & Perkins, Citation1975; Reynolds & Ortony, Citation1980; Vosniadou, Citation1987; Vosniadou, Ortony, Reynolds, & Wilson, Citation1984). Since then, interest in the developmental aspects of metaphor has significantly decreased. In the authoritative Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor (Gibbs, Citation2008), for example, no chapter deals with development. The situated ontogenesis of metaphors and metaphor abilities must be studied, in order to understand how metaphors are part and parcel of the highly flexible processes of human sense-making.

Another point regards the status of novel metaphors. Novel metaphors are defined in this article as involving fresh insight, based on the focused perception of some pattern that remains invariant across two kinds of things, where one kind of thing (traditionally called the topic term) is perceived in terms of another kind of thing (traditionally called the vehicle term). The shared invariant structure constitutes the metaphoric ground that is the basis of the topic–vehicle relationship (cf. Dent-Read & Szokolszky, Citation1993; Read & Szokolszky, Citation2016). When a 3-year-old child, for example, puts four remote controllers in a row, and says to her mother, “Look, a train!,” she communicates, and acts out a creative insight, based on perceiving a pattern shared by the row of controllers and trains, calling her mother’s attention to the “trainness” of the controllers. The child explores the multiplicity of meaning inherent in the objects by producing a novel metaphor.

In this article, the emphasis will be on the development of novel metaphors, from an ecological point of view. In the following discussion, I will briefly present the conceptual foundations of EP, and then introduce the ecological–developmental framework to metaphor. Empirical work done in this framework will be used to substantiate the major points, and differences between pretend play and children’s metaphors will be pointed out. The article’s overall conclusion is that the emergence of novel metaphors in ontogenetic development is a perception-based process, embedded in social context. Thus, to study novel metaphors from a developmental–ecological point of view is an important way of studying the embodied mind in action.

Ecological psychology: A mutualist embodied framework

Any epistemology (even a social constructivist one) must, at some point, assume some kind of direct contact with the world. The ingrained view is to believe that direct contact is based on sensations—that is, on elementary aspects of physical stimulation reaching our sensory organs. Concepts are then supposed to enrich and make the impoverished input meaningful. In this traditional framework perception is about mere appearances, and valid knowledge can only be achieved through cognitive processing (cf. Crane & French, Citation2017). Perception is about how things look, and conception is about how they really are.

In the early 1960s, Gibson’s revolutionary idea was that sensations are not the basis of our direct contact with the world, because direct contact must be at the level of primary meaningfulness. Once we buy into the idea of sensations made meaningful by attached representations or any other secondary processes, we buy into a dualism that segregates the organism from its environment and leaves no principled account of veridical knowing (also see, e.g., Still & Costall, Citation1992).

How is direct knowing, as an epistemic function, possible? To this end, Gibson proposed a new theory of perception and action, defined on the basis of the embodied organism, embedded in its ecological environment (Gibson, Citation1966, Citation1979). The core idea is that at the ecological scale the environment is a rich source of directly available meaning for the attuned organism, equipped with adaptive, sensitive perception–action systems. Mutuality is expressed by the coimplicative nature of the organism–environment (O-E) system and captured by the following ecological principles (cf. Richardson, Shockley, Fajen, Riley, & Turvey, Citation2009):

The “single system” perspective: organism and environment comprise one (O-E) system. Behavior is the reorganization of this system, not the interaction of O and E. Mental processes, as well, are aspects of the O-E system, not local processes of O.

The ecological scale principle: what is perceived, acted on, and known is defined at the ecological scale of the organism as a whole. People—and organisms in general—must be considered acting in their particular ecological niche in an embedded way. Ecological realities involve substances, surfaces, places, objects, people, and events at the scale where they have relevance for the organism.

Emergence and self-organization: novel behavior emerges due to complex nonlinear and nonlocal interactions among components of O-E systems, in a highly context-dependent manner. When an organism (animal or human) produces coordinated action, the coordinative pattern originates not in the individual components (such as muscles, joints, or neuromotor structures), but in the dense interactions of the components.

The conjoint nature of perception and action: perception and action cannot be separated. They both serve the aims of the organism in a reciprocal way: perception dynamically constrains action and action dynamically constrains perception. Perception and action do not “interact” but are mutually and continually unified aspects of the same event.

Information is specificational: the term information is reserved to refer to relations where perceivable dynamic patterns directly specify their source and thereby can be directly meaningful for the organism. For example, optic flow patterns generated by walking or driving specify one’s direction of heading.

Perception is of affordances: that is, E is perceived in terms of meaningful action possibilities relative to a given O with given bodily and cognitive capabilities, intentions, and experiential histories.

The word “affordance” was coined by J.J. Gibson in the 1960s in order to create a term “that refers to both the environment and the animal in a way that no existing term does” (Gibson, Citation1979, p. 129). This mutualist concept captures the codeterminate character of functional meaning in the O-E system. A given environment offers directly perceivable possibilities for action, and agents take advantage of these possibilities, which have intrinsic relational value, and therefore are directly meaningful, in a situated way. Recent work (Rietveld & Kiverstein, Citation2014) reminds us that Gibson (Citation1979) viewed affordances as embedded in “ways of life,” which include the whole “staggering” domain of social significance. On a social level the affordances an environment offers for humans are relative to the human way of life and sociocultural norms. The affordance field is a “rich landscape” (Rietveld & Kiverstein, Citation2014), and, in order to act, the actor must selectively differentiate and attend to relevant affordances. The “skilled intentionality” framework (Rietveld et al., Citation2018; van Dijk & Rietveld, Citation2017) emphasizes that selective engagement with affordances is situated and integrated with social coordination. Skilled intentionality is coordinating with multiple affordances simultaneously in a concrete situation. The actor must enact, that is, selectively “bring forth” relevant affordances (Van Den Herik, Citation2018).

The ecological concept of “information”

Organisms are actively oriented to perceive and to generate patterns that are informative—that have functional value and significance for action. EP has further elaborated the ontological and epistemological foundations of direct perception by the concept of specificational information. This concept is based on the idea of invariants (Gibson, Citation1979). In the natural ecology change is primary, and the unchanging, invariant aspects of the world become manifest over transformations. This can be, for example, the invariance of the same face over various emotional expressions or progress of age, or the invariance of smiling over various faces. Invariant patterns are all over in the arrays of energy (optical, acoustical, mechanical) surrounding the organism. Such are, for example, “optic flow patterns” that are produced as the agent moves about in the environment. Moving toward an object, for example, produces the optic flow pattern of expansion, whereas moving away produces the optic flow pattern of shrinking (Gibson, Citation1979).

Invariant structures become information when sensitive agents become attuned to them, detect and extract them, and dynamically couple their perception and action to them. An object looming toward a stationary perceiver is also specified by optical expansion; however, in the case of the moving observer the whole array transforms, whereas in the case of the stationary observer only the pattern produced by the moving object is transformed. Because these patterns are unique and invariant under the same conditions they provide specificational information for the control of self-motion (cf. Gibson, Citation1986; for a recent summary see Warren & Wertheim, Citation2014). Affordances and specificational information are complementary concepts. To put it differently: a rich landscape of affordances is, by necessity, a rich landscape of specificational information.

Epistemic contact with the world is a perennial metaphysical issue that is relevant for current ecological–enactive views. Whereas many embodied–enactive approaches ground cognition in sensorimotor dynamics and representations, EP grounds epistemic contact in specificational information, direct perception, and affordance-based action, at the ecological organism–environment system level. Radical embodiment requires that we anchor embodiment in ecological mutualism (cf. Marsh et al., Citation2009).

One argument against enactive science is that it can account for low-level abilities but much less for high-level abilities (cf. Stewart, Stewart, Gapenne, & Di Paolo, Citation2010). The assumption behind this critique is that low-level (sensorimotor) functions and high-level (cognitive, representational) functions are dichotomous. The ecological approach questions this dichotomy by placing the fundamental part of the “epistemic burden” on meaningful perception and action that are high-level functions to begin with. Perception, action, cognition, and language are inseparable, intertwined processes of knowing, that proceed not from low level to high level, but from an undifferentiated manifold to a differentiated and integrated manifold.

All this metaphysics has relevance, if we want to “take metaphor out of our heads” (cf. Gibbs, Citation1999, 146), and consider metaphor and metaphoricity to be a regular epistemic–communicative function. Let’s see next how EP can be extended to understand development at large, and specifically, the development of metaphor.

Children’s novel metaphors, from a developmental ecological point of view

Naturalistic studies (e.g. Dent-Read, Citation1997; Szokolszky, Citation2004; Winner, Citation1979) showed that children do spontaneously produce metaphors early on. A paradigmatic example is when a 2.6-year-old points at a cabbage on the kitchen desk and says, “This is a cannon ball.” This is a well-formed novel metaphor that involves seeing and understanding one thing in terms of another different kind of thing, in a way that is not provided culturally.

How do we account for the emergence of early metaphors in the ecological conceptual framework? There are two layers to account for: (a) The broader developmental process that establishes the basic abilities of the child to successfully deal with the world and (b) the situated emergence of metaphoric expression including its context of individual experiential history leading up to the specific metaphor and the changed understanding of the world that extends beyond the situation.

The developmental ecological view of the broader developmental process

Traditional views of psychological development focus on the infant/child as the unit of analysis and parse developmental causes into separate biological and environmental sources and their interaction. In this view, no complex behavior is possible without complex mental representations, which are considered to be the essential link between the inside mind and the outside world. Mental representations constitute an independent level that validates ambiguous and partial perceptual data. As famously promoted by Piaget and lnhelder (Citation1969) and Vygotsky (Citation1981), and endorsed by later cognitive views of development, with development there is less and less reliance on perception and more and more reliance on symbolic thought.

In contrast, DEP starts out by assuming an initial close fit and coupling between organism and environment. The infant is engaged in the world from the very beginning in a meaningful way, through cycles of action and perception. Development is defined over the changing organism–environment system and is marked by the progressive emergence of new relational structures in this system, along with an increasingly differentiated knowledge of the world. In this theory perception never stops being important in primary ways. In fact, cognitive development only advances through more and more sophisticated perception and action (Adolph & Kretch, Citation2015; Gibson & Pick, Citation2000; Read & Szokolszky, Citation2018).

Developmental Ecological Psychology emphasizes exploration as a central developmental process (Gibson & Pick, Citation2000), aimed at detecting information in the service of action. For the infant, information is defined as functionally significant invariant patterns, such as patterns specifying affordances of suck-on-ability, step-on-ability, or graspability of objects (e.g., Gibson, Citation1988; Gibson & Pick, Citation2000; Gibson & Walker, Citation1984). Ecological research has shown that infants functionally control their bodies early on to gain exposure to structured information and, in general, they engage in extensive visual, oral, haptic exploratory activities while learning about affordances (Gibson & Pick, Citation2000).

Importantly, for the development of metaphoric abilities, ecological research has shown that meta-modal perception, that is, information across the traditional “senses” such as sight and sound, is fundamental to development. An example is when 5-month-olds can identify a rigid object moving after sucking on the rigid object, or when separately presented auditory and visual information on an event are perceived as being one and the same event (for this and other research examples, see, e.g., Bahrick & Hollich, Citation2008; Gibson & Pick, Citation2000). This early sensitivity to higher-order information across perceptual modalities is essential because it shows that infants are attuned to perceptual information specifying higher-order patterns.

Infants discover naturally occurring kinds: invariants that specify distinguishable entities as though they are equivalent, such as different types of dogs all being dogs, particular smiles as all being smiles, and so on (cf. Millikan, Citation1984; Pick, Citation1997). Categorization is a highly flexible, dynamic, and context-dependent process from the beginning. Developmental research on categorization shows that young children have no difficulty in grouping objects in multiple ways, according to opportunities regarding task and contexts (Pick, Citation1997). Flexible categorization shows that cognitive agents are ever ready to attune their attention into available novel invariant information.

The role of language in development

Language development enhances this process. In the ecological approach language development is based on the idea that perceptual systems function to detect language–world relationships and the perception of affordances underlies linguistic meaning (Dent, Citation1990; Rączaszek-Leonardi, Citation2010; de Villiers Rader & Zukow-Goldring, Citation2012). Language development is viewed as properly grounded in ongoing perception–action cycles that tune perceptual systems to the role of affordances for action. Language use emerges from the interactive matrix of individuals who continuously educate each other’s attention to perceived structures in the world. As a precursor to language, prelinguistic infants already participate in interactions that involve turn-taking behaviors under the guidance of a caregiver (Rączaszek-Leonardi, Citation2016). Caregivers educate infants’ attention (cf. Gibson, Citation1966) by synchronizing the saying of a word with a dynamic gesture displaying the referent, and children detect amodal invariants across gesture and speech (Zukow-Goldring & de Villiers Rader, Citation2013; Zukow-Goldring & Rader, Citation2001). Signs used for communication start out as physical events and become recruited for communication because of their particular history of exerting control within organism–organism and organism–environment relations (Rączaszek-Leonardi, Nomikou, Rohlfing, & Deacon, Citation2018).

Thus, language development leads to detecting new relationships. Perceiving provides knowledge that is progressively more subtle, differentiated, and higher order as perceptual skills allow a more differentiated examination of the world. Language serves as a medium for focusing perception and knowledge of the world for communicating and coordinating actions with others. We do find specificity between language and the world, if, instead of isolated words and sentences, we look for situated, social, and embodied “languaging” activity (Dent, Citation1990; Thibault, Citation2011; Zukow-Goldring, Citation2012). This is compatible with reconceptualizing language as a mode of social coordination, action that functions as enabling constraints on cognitive and interactive dynamics (Van Den Herik, Citation2018).

Development takes place in a sociocultural ecology wherein infants and caretakers engage in the mutual regulation of one another’s attention and feelings in intricate, rhythmic patterns. Children’s attention is directed, and their actions are guided by adults along culturally accepted norms and intentions. Children are introduced to the culturally preferred ways of using objects (so-called canonical affordances; cf. Costall, Citation2012; Costall & Richards, Citation2013), but the dynamic field of available affordances always offers a multiplicity of meaning and ample room for creative action and perception.

In sum, DEP has established that infants and children are able and oriented actors and perceivers, sensitive to information specifying the rich, dynamic landscape of affordances. The above account of the broader developmental process presents a background that accomodates metaphoric ability as a natural outgrowth of the active, embodied interest and engagement of the infant with the world, where multiplicity of meaning is ever present.

Studying metaphors from a developmental ecological perspective

Eliciting metaphors: Experimental studies

The ecological approach suggests that novel metaphors are perceptually guided adaptive actions. Thus, at the heart of metaphor is the direct resonance to cross-kind invariant patterns available in the field of direct perceptual experience (Dent-Read & Szokolszky, Citation1993; Read & Szokolszky, Citation2016). Because the extraction of informational invariants is the assumed basis of acting, perceiving, and knowing, it is expected that detecting metaphoric resemblance is a natural activity even for young children, given proper information and attunement. This assumption has been studied experimentally, as well as in naturalistic settings.

The ecologically motivated study of early metaphors was launched in the 1980s, when metaphoric competencies were thought to require sophisticated representational skills and the violation of category boundaries (cf. Vosniadou, Citation1987; Vosniadou & Ortony, Citation1983). In those studies, children typically had to paraphrase metaphoric sentences out of situational or narrative context or perform other verbal tasks related to metaphor comprehension. On the grounds of the ecological approach, however, Dent (Citation1984) found that films of natural and naturalistic events and objects could be used to elicit novel metaphors from children as young as five years old in answer to specific questions, and that event similarity (cross-kind invariants across two moving objects; e.g., a ballerina spinning and a top spinning) was particularly powerful in this regard. Dent and Rosenberg (Citation1990) investigated developmental changes in children’s abilities to comprehend visual metaphors (e.g., a wrinkled apple with added eyes and mouth forming a face; as measured by their use of verbal metaphor, and found that from ages five to seven children improve in their ability to understand visual metaphors.

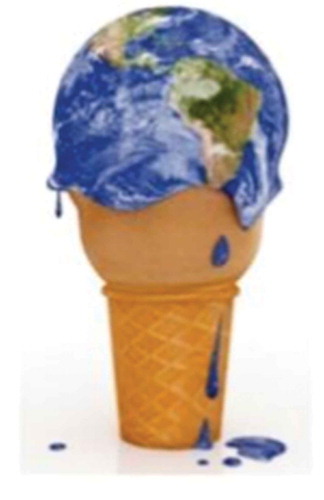

In an another experimental study (Read & Szokolszky, Citation2016) perceptual information was provided for children at four, six, eight, and 10 years of age and adults to support metaphor production. Participants were invited to talk about the pairs of photographs that depicted objects and events from verbal metaphors earlier produced by other children. For example, “The fireworks are flowers” metaphor was instantiated by a photo of a large, spherical burst of fireworks in the night sky and a separate photo of a flower, with its petals shooting out from the center (see .) The experiment tested if children in the given age ranges could pick up the invariants across the pictures (such as the outward radiance of the firework and of the flower), and if they would verbalize those in metaphoric utterances in the conversational context. This study showed that metaphor use could be elicited by static photographs even at the youngest age, but a developmental pattern of increasing metaphor use was also demonstrated.

Figure 1. Sample picture of metaphoric pairs: fireworks and flowers, from Read & Szokolszky, Citation2016 .

From the perspective of the developmental ecological view of metaphor, these experimental studies supported the proposition that by manipulating the available perceptual information and discourse context, metaphor production can be elicited in all age ranges in controlled perceptual and conversational situations, and children and adults alike respond to aspects of such perceptual information. Even though these abilities begin at early ages, they continue to develop in facility and frequency to adulthood.

Spontaneous use of metaphor by children: Diary studies

Children’s spontaneous metaphor use at early ages was also investigated in longitudinal diary studies in naturalistic settings conducted in parallel in Hungary and the United States (Dent-Read, Citation1997; Szokolszky, Citation2004, Citation2006). Two English-speaking and two Hungarian-speaking children and their mothers participated in the study. Caretakers made narrative diary entries on their children for an extended time (2 years in the case of the Hungarian families and 4 years in the case of the American families). Mothers took regular notes on occurrences when their children intentionally enacted a meaning different from the standard meaning of objects or events. Children’s metaphors and pretend play were differentiated (see next section). The diary study with the American families (Dent-Read, Citation1997) documented metaphoric use of single words at least one year earlier (at 18 months) than any previous study, showing that the perceiving and noticing that underlies metaphor in language is available to children at the beginning of language development.

The diary studies found evidence for the increasing elaboration of metaphoric statements. Examples of children’s metaphor production showed up as acts of attentional actions addressed to the caretaker in which the child pointed out some relevant novel aspect of what s/he recognized in her/his immediate environment. A paradigmatic example from the Hungarian study (Szokolszky, Citation2004) is the situation in which the child calls out to his father: “Look, the sea is sneezing!” upon watching a whale splashing into the water, when sitting in his father’s lap and watching a nature film. There is an aspect in the perceptual field shared by two familiar, different kinds of naturally occurring events (splashing and sneezing) that the child is responding to, in a creative way. In the metaphor conventional category boundaries are crossed, but also preserved, since the child invites the adult to see the splashing event in terms of a sneezing event. The ground of the metaphor is not a simple likeness but a dynamic informational invariant. The child has experience with both splashing and sneezing, but suddenly he notices the invariant across the two different, familiar kinds of things in a novel way.

The utterance of the metaphor is, at the same time, an affective whole-body exclamation communicating the excitement of new knowledge to the father. The father approves by smiling and saying “Yes, indeed!” There is no need for clarification. The utterance is interesting because it is clear that the child is not mistaking referents but sharing a novel observation. In education of attention it is usually the adult who guides the action; in this situation, however, it is the child who guides the attention of the adult. Both the child and the father easily perceive the multiplicity of meaning involved in the event.

According to the ecological model, what develops in metaphor use is a threefold process: (a) An ever-increasing differentiation and integration of experiencing naturally occurring real kinds present in the world; (b) Experiencing insights into metaphoric relations across real kinds, and (c) The increasing skill of using metaphoric language to express those insights to a listener in conversation (Read & Szokolszky, Citation2016).

Metaphor in dialog: Naturalistic observation

Novel metaphors can also emerge at the interpersonal level, in dialogs. According to the synergy model (Fusaroli, Rączaszek-Leonardi, & Tylén, Citation2014), dialogs are self-organizing, interpersonal cognitive systems, played out in whole-body communication. A good dialog affords complementary dynamics, constrained by contextual sensitivity and functional specificity.

Looking jointly at a picture book with a parent is an important situation in the developmental history of a child, in which dialogs emerge. The parent and the child have each other’s exclusive attention and a focus on the pictures. The pictures constrain the conversation but also afford an open-ended exchange of ideas and emotions. There is, usually, a high level of coordination and togetherness in such situations.

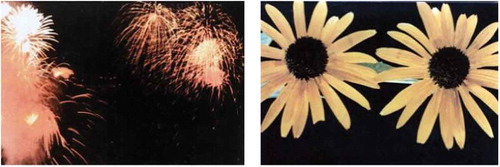

In an ongoing study with five Hungarian families (Szokolszky & Szalkai, in progress) mother–child pairs are given a booklet with eight metaphoric and eight non-metaphoric pictures, selected from the Internet, to look at in their homes. The parent is asked to sit down with the child and look at the pictures, as they would do when they are browsing through a new picture book; no further instructions are given. Video recording is done with only the parent and the child present in the room. As a follow-up, in two or three days the research assistant sits down with the child again, to look at the picture book to see how discussing the same pictures evolves, given the previous conversation with the mother. A sample dialog is presented below, taken from the recorded conversations, about a metaphoric picture that portrays the Earth as if it were a scoop of melting ice cream in a cone (see ). The mother and the child (M.M., 5yr 3mo) are sitting next to each other and looking at the picture showing the Earth as ice cream):

Turns the page to the “Earth is a melting ice cream” picture.

Ice cream!

And … what does this ice cream portray? Points at the upper part of the picture.

The Earth!

Yes, indeed! And what does the Earth do? Makes a downward gesture.

Down, down…. It is melting.

Yes, the Earth is melting! And what do we have to do with the Earth? The child looks at the mother.

We have to take care of it, right? Turns the page.

In the above conversation the child promptly says he sees an ice cream. The mother accepts but presses further (What does it portray?) and directs the child’s attention to the unattended aspect of the picture (the Earth). As a response, the child names the Earth without making connection between ice cream and earth. Then, the mother points out another unattended aspect of the picture (dripping) and again presses further by a question, personalizing the Earth (What does the Earth do?). The child says “down” and “melting,” probably making a literal referent of the ice cream melting. The mother approves and moves on by saying we have to protect the Earth. The child does not respond verbally, and it is unclear what this statement (as a matter of fact, the whole conversation) meant for him.

Two days later, in a the follow-up dialog, the research assistant (Adult) sat down with the child in his home, to look at the same picture book. The dialog regarding the same picture is as follows:

Turns the page to the “Earth as melting ice cream” picture.

Ice cream! Ice cream globe! We have to take care of it! Because it is melting.

Take care of it? Oh, yeah, it could melt…. Is there anything else?

Looks like a man with a hat on his head…

Yes! A Hat!

And this is dripping… Points at dripping… Tears…

Tears… Looks like a crying man...

In this session, the child surprised the adult by a spurt of utterances (Ice cream! Ice cream globe! We have to take care of the ice cream globe! Because it is melting!). At this point, the child formulates the metaphoric expression “ice cream globe,” which shows that he has perceived the metaphoric relationship between the ice cream and the Earth, as portrayed in the picture. The child then goes on spontaneously to produce two other metaphors in a row: the ice cream is a man with a hat on his head (probably referring to a bike helmet), and melting is crying. At this point the child eventually takes the lead in meaning-making, and the adult approves his insights.

We can take these two sessions as one evolving event, extended in time from the child’s point of view, revolving around the experience of the particular picture being looked at with his mother, and later with another adult. In this example we see how multiple meanings emerge across speakers and utterances within a situation, and how it extends across situations in time. The child makes a metaphoric expression in the second session, but this wouldn’t have happened without the previous conversation with the mother. Even though the mother did not use metaphor in the first session, and was not even her intention to elicit a metaphor from the child, her questions were effective in directing the child’s attention to aspects of the picture that were later instrumental in his reaction to the picture. The meaning expressed often contains ambiguities, but this does not harm the conversation. The child and the adult understand each other and create new knowledge together.

Differentiating metaphor and pretend play

In pretend play the child uses an object as if it were another object (e.g., picks up a banana and uses it as a phone). Previous work claimed that such actions and accompanying uttererances involve metaphors (e.g. Winner, Citation1979). Current authors have also taken the position that the child acts out a metaphor when she picks up a banana and uses it as a phone (Gallagher & Lindgren, Citation2015). Others have argued that pretend play actions and children’s metaphors should be distinguished as different types of events (Dent-Read, Citation1997; Marjanovic-Shane, Citation1989; Vosniadou, Citation1987).

Dent-Read (Citation1997) argues that metaphor involves perceiving one kind of thing (the topic term) in terms of another kind of thing (the vehicle term), based on a structural or dynamic invariant across kinds, which results in a transformed understanding of the vehicle term. In pretend play, on the other hand, the focus is “to let x stand for y.” Elanor J. Gibson introduced the distinction of performatory and explanatory perceptual activities (E.J. Gibson, Citation1988). Performatory activity has a specific purpose, and perception supports action in order to reach that purpose. Exploratory activity has exploration itself in its focus, with an emphasis on observing and noticing. Dent-Read (Citation1997) suggests that metaphor involves exploratory activity, while pretend play involves performatory activity.

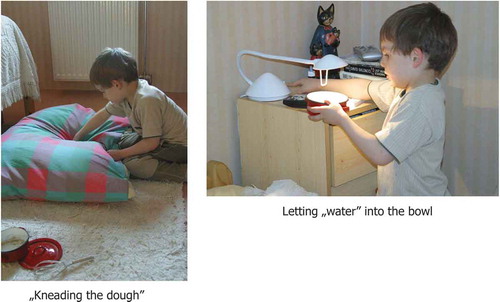

The diary studies made it possible to study contextualized, natural occurrences of pretense and metaphor. Take the example when the child pretends to bake bread in the bedroom, using the pillow as “dough” and light coming from a lamp as faucet to get “water,” next day, when he was baking bread with his mother (Szokolszky, Citation2006, see . for the photographic documentation of this episode). In this situation, the child’s actions and perceptions are guided by his intention to “bake bread.” He grabs an object at hand, which is a good-enough substitute for the real thing, and acts as if it were the object he needed. The substitute is a prop that is used to act out a culturally mediated, structured, and sequenced action in a compressed fashion. In the bedroom he spots the pillow as a kneadable object, takes it from the bed, puts it on the floor and starts to knead it. Looking around for water, he runs to the lamp with the pot in his hand, turns the light on, and holds the pot under the light, as if the light rays were water coming from a faucet. The action sequence is seamlessly organized by the knowledge of how to bake bread, by the intention to “bake bread” and by perceiving affordances available at hand.

Figure 3. Photographed documentation of the insightful use of objects in a pretend play episode; diary study in a Hungarian family (Szokolszky, Citation2004). The child (F.B., 3.2 years old) was baking bread with the mother the previous day; the next day he pretended to bake bread in the bedroom, using the pillow as “dough” and light coming from a lamp as faucet to get “water.”

Traditionally, such acts are called symbolic play, and they are taken as proof of sophisticated representation-based cognition because the child seems to disregard perceptual features, violate conceptual boundaries, and represent one object as if it were something else (e.g., Leslie, Citation1987; Lillard, Citation1993). The pretend act of using a block as a horse was self-evidently described as a process in which “one employs one’s own mental representation of the block and applies that representation to the horse” (Lillard, Citation1993, p. 373). The ecological view on pretend object play suggests, however, that pretend acts involve not the increasing symbolic capacity to treat objects representationally, but creative affordance perception, during which the child re-contextualizes, not de-contextualizes, the act (Szokolszky, Citation1996, Citation2006). The enactive approach to pretend play (Rucinska, Citation2014, Citation2016; Rucinska & Reijmers, Citation2015) likewise suggests that pretense need not invoke mental representations; instead, it focuses on interaction and the role of affordances in shaping pretend play.

Compare the above example to the event, when the child grabs a bunch of keys, shakes them for a while, looking at them and then says: “Look, mom, they are dancing.” The mother looks at the keys in motion and says, approvingly, “Oh, really!” The child’s utterance is not produced in the context of a play episode. It stands out as noticing a novel aspect of the world at hand, a discovery produced by the child himself, and is addressed to the adult as an observation. There are similarities, as well as differences, between the play event of bread-baking and the shaking of the keys and sharing the related discovery. In both events the child enacts a meaning that is different from the standard meaning of the objects involved. In both cases the child enacts metaphoricity, broadly defined, since s/he brings a novel meaning into existence through perceiving and enacting affordances in creative ways, across kinds.

Using E.J. Gibson’s (Citation1988) terminology, bouncing the keys, and discovering that there is a higher-order invariance shared by dancing, is more of an exploratory than a performatory activity. At the same time, using the props in the sequence of “baking bread” is more of a performatory than an exploratory activity. In the bread-baking episode the child is actively looking for a substitute object with a purpose in mind, and, in using the object s/he reexperiences an event s/he has aready encountered. In the key-shaking episode, a novel experience, a discovery, is the focus. Not acknowledging these differences between these situations would conflate two differently tuned cognitive acts, which have different relevance in the developmental process. Differentiating pretense and metaphor does not, however, create a dichotomy. Inasmuch as perception and action are inseparable, epistemic and pragmatic functions are also inseparable in perceiving and acting. Both pretense and metaphor are acts of creative meaning-making in which epistemic and pragmatic functions are intertwined. They come naturally for the child in the course of ongoing action and perception because multiplicity of meaning is the rule, not the exception, in human ecology.

Conclusion

In this article I presented an ecological approach to metaphor as a developmental–perceptual process, rooted in the EP tradition following the work of J.J. Gibson and its extension into DEP, as developed by E.J. Gibson and others. I argued that an ecological metatheory, based on mutualist ontology and epistemology of the organism–environment system, is necessary for embodied approaches to metaphor. This framework has much in common with enactive approaches, but grounds contact with the world in the direct perception of affordances and specificational information.

I argued that EP offers an elaborate framework of ontological–epistemological foundations, and that DEP provides an account of development that naturally integrates metaphoricity and novel metaphor production and comprehension in development.

Finding that children’s metaphoric competencies are part of early development is an important piece of evidence. The world affords metaphor perception for humans, including conceptual metaphors and novel metaphors alike, as much as it affords perception and action in general. Metaphors are nothing strange or alien: they are part of the epistemic process that helps people find their way and coordinate their living actions with the structures and processes of the real world.

Acknowledgments

The developmental ecological approach to metaphor presented in this article has been pioneered by Catherine Read, who was my PhD advisor at the Department of Psychology, University of Connecticut, in the early 1990s. I thank Catherine Read for the fruitful collaboration throughout the past years, and also for suggestions to improve this article. I also thank Thomas Wiben Jensen for extensive and helpful comments on the previous version of this article. Publications referenced in this article by Dent, C.H., Read, C., and Dent Read, C. are all by Catherine Read.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Adolph, E., & Kretch, K.S. (2015). Gibson's theory of perceptual learning. In J.D. Wright (ed-in-Chief). International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Amsterdam, ND: Elsevier, 10, 127–134.

- Bahrick, L. E., & Hollich, G. (2008). Intermodal perception. Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development, 2, 164–176.

- Billow, R. M. (1975). A cognitive developmental study of metaphor comprehension. Developmental Psychology, 11, 415–423. doi:10.1037/h0076668

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In N. Eisenberg, R. A. Fabes, & T. L. Spinrad (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 795–827). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

- Chemero, A. (2011). Radical embodied cognitive science. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

- Costall, A. (1999). An iconoclast’s triptych: Edward reed’s ecological philosophy. Theory & Psychology, 9, 411–416. doi:10.1177/0959354399093011

- Costall, A. (2004). From direct perception to the primacy of action: A closer look at James Gibson’s ecological approach to psychology. In G. Bremner & A. Slater (Eds.), Theories of infant development (pp. 70–89). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Costall, A. (2012). Canonical affordances in context. Avant, 3(2), 85–93.

- Costall, A., & Richards, A. (2013). Canonical affordances: The psychology of everyday things. In P. Graves-Brown, R. Harrison, & A. Piccini (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the archaeology of the contemporary world (pp. 82–93). Oxford, UK.

- Crane, T., & French, C. (2017). The problem of perception. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Spring 2017 Edition). Retrived from. <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/perception-problem/>

- de Villiers Rader, N., & Zukow-Goldring, P. (2012). Caregivers' gestures direct infant attention during early word learning: The importance of dynamic synchrony. Language Sciences, 34(5), 559–568.

- Dent, C. H. (1984). The developmental importance of motion information in perceiving and describing metaphoric similarity. Child Development, 55(4), 1607–1613.

- Dent, C. H. (1987). Developmental studies of perception and metaphor: The Twain shall meet. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity, 2, 53–57. doi:10.1207/s15327868ms0201_4

- Dent, C. H. (1990). An ecological approach to language development: An alternative functionalism. Developmental Psychobiology, 23(7), 679–703. doi:10.1002/dev.420230710

- Dent-Read, C. H. (1997). A naturalistic study of metaphor development: Seeing and seeing as. In C. E. Dent-Read & P. E. Zukow-Goldring (Eds.), Evolving explanations of development: Ecological approaches to organism–Environment systems (pp. 255–296). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Dent-Read, C. H., Klein, G., & Eggleston, R. (1994). Metaphor in visual displays designed to guide action. Metaphor and Symbol, 9(3), 211–232. doi:10.1207/s15327868ms0903_4

- Dent-Read, C. H., & Szokolszky, A. (1993). Where do metaphors come from? Metaphor and Symbol, 8(3), 227–242. doi:10.1207/s15327868ms0803_8

- Dewey, J., & Bentley, A. (1949). Knowing and the known. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Fusaroli, R., Rączaszek-Leonardi, J., & Tylén, K. (2014). Dialog as interpersonal synergy. New Ideas in Psychology, 32, 147–157. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2013.03.005

- Gallagher, S. (2017). Enactivist interventions: Rethinking the mind. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Gallagher, S., & Lindgren, R. (2015). Enactive metaphors: Learning through full-body engagement. Educational Psychology Review, 27(3), 391–404. doi:10.1007/s10648-015-9327-1

- Gardner, H., Kirchner, M., Winner, E., & Perkins, D. (1975). Children’s metaphoric productions and preferences. Journal of Child Language, 2, 125–141. doi:10.1017/S0305000900000921

- Gibbs, R. W., Jr. (1999). Taking metaphor out of our heads and putting it into the cultural world. Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Sciences Series, 4, 145–166.

- Gibbs, R. W., Jr. (2008). Metaphor The state of the art. In R. W. Gibbs Jr (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of metaphor and thought (pp. 3–16). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gibbs, R. W., Jr., & Cameron, L. (2008). The social-cognitive dynamics of metaphor performance. Cognitive Systems Research, 9(1), 64–75. doi:10.1016/j.cogsys.2007.06.008

- Gibson, E. J. (1969). Principles of perceptual learning and development. New York, NY: AppletonCentury Crofts.

- Gibson, E. J. (1988). Exploratory behavior in the development of perceiving, acting, and the acquiring of knowledge. Annual Review of Psychology, 39(1), 1–42. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.000245

- Gibson, E. J. (1997). An ecological psychologist’s prolegomena for perceptual development: A functional approach. In C. Dent-Read & P. Zukow-Goldring (Eds.), Evolving explanations of development: Ecological approaches to organism-environment systems (pp. 23–45). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Gibson, E. J., & Pick, A. D. (2000). An ecological approach to perceptual learning and development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Gibson, E. J., & Walker, A. S. (1984). Development of knowledge of visual-tactual affordances of substance. Child Development, 55, 453–460. doi:10.2307/1129956

- Gibson, J. J. (1966). The senses considered as perceptual systems. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. Co.

- Gibson, J. J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Heft, H. (2001). Ecological psychology in context: James Gibson, Roger Barker, and the legacy of William James’s radical empiricism. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Heft, H. (2013). An ecological approach to psychology. Review of General Psychology, 17(2), 162–167. doi:10.1037/a0032928

- Ingold, T. (1992). Culture and the perception of the environment. In E. Croll & D. Parkion (Eds.), Bush base: Forest farm. Culture, environment and development (pp. 39–56). London, UK: Routledge.

- Jablonka, E., & Lamb, M. J. (2014). Evolution in four dimensions, revised edition: Genetic, epigenetic, behavioral, and symbolic variation in the history of life. Boston, MA: MIT press.

- Jensen, T. W. (2016). Doing metaphor. In B. Hampe (ed.). Metaphor: From embodied cognition to discourse. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Jensen, T. W., & Cuffari, E. (2014). Doubleness in experience: Toward a distributed enactive approach to metaphoricity. Metaphor and Symbol, 29(4), 278–297. doi:10.1080/10926488.2014.948798

- Kauffman, S. (2013). Evolution beyond Newton, Darwin and entailing law. In B. G. Henning & A. C. Scarfe (Eds.), Beyond mechanism: Putting life back into biology (pp. 1–24). Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books.

- Kövecses, Z. (2010). Metaphor: A practical introduction. Oxford. UK: Oxford University Press.

- Kövecses, Z. (2011). Recent developments in metaphor theory: Are the new views rival ones? Review of cognitive linguistics. Published under the Auspices of the Spanish Cognitive Linguistics Association, 9(1), 11–25.

- Kövecses, Z. (2013). The metaphor - metonymy relationship: Correlation metaphors are based on metonymy. Metaphor and Symbol, 28(2), 75–88.

- Leslie, A. M. (1987). Pretense and representation: The origins of “theory of mind”. Psychological Review, 94, 412–426. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.94.4.412

- Lillard, A. S. (1993). Young children’s conceptualization of pretense: Action or mental representational state? Child Development, 64, 372–386. doi:10.2307/1131256

- Mace, W. M. (2005). James J. Gibson’s ecological approach: Perceiving what exists. Ethics & the Environment, 10(2), 195–216. doi:10.2979/ETE.2005.10.2.195

- Marjanovic-Shane, A. (1989). "You are a pig". For Real or Just Pretend? Different Orientations in Play and Metaphor. Play and Culture, 2(3), 225–234.

- Marsh, K. L., Johnston, L., Richardson, M. J., & Schmidt, R. C. (2009). Toward a radically embodied, embedded social psychology. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(7), 1217–1225. doi:10.1002/ejsp.v39:7

- Menary, R. (2010). Introduction to the special issue on 4E cognition. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 9(4), 459–463. doi:10.1007/s11097-010-9187-6

- Michaels, C. F., & Palatinus, Z. (2014). A ten commandments for ecological psychology. In L. Shapiro (Ed.), Routledge handbook of embodied cognition (pp. 19–28). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

- Millikan, R. G. (1984). Language, thought, and other biological categories: New foundations for realism. Boston, MA: MIT press.

- Müller, C., & Tag, S. (2010). The dynamics of metaphor: Foregrounding and activationg metaphoricity in conversational interaction. Cognitive Semiotics, 10(6), 85–120. doi:10.3726/81610_85

- Newen, A., DeBruin, L., Gallagher, S. (Eds.). (2018). The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Noë, A. (2009). Out of our heads: Why you are not your brain, and other lessons from the biology of consciousness. London, UK: Macmillan.

- Piaget, J, & Inhelder, B. (1969). The psychology of the child. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Pick, A. D. (1997). Perceptual learning, categorizing and cognitive development. In C. Dent-Read & P. Zukow-Goldring (Eds.), Evolving explanations of development: Ecological approaches to organism–Environment systems (pp. 335–370). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Raczaszek-Leonardi, J. (2016). How does a word become a message? An illustration on a developmental time-scale. New Ideas in Psychology, 42, 46–55.

- Rączaszek-Leonardi, J. (2010). Multiple time-scales of language dynamics: An example from psycholinguistics. Ecological Psychology, 22(4), 269–285. doi:10.1080/10407413.2010.517111

- Rączaszek-Leonardi, J., Nomikou, I., Rohlfing, K. J., & Deacon, T. W. (2018). Language development from an ecological perspective: Ecologically valid ways to abstract symbols. Ecological Psychology, 30(1), 39–73. doi:10.1080/10407413.2017.1410387

- Read, C., & Szokolszky, A. (2016). A developmental, ecological study of novel metaphoric language use. Language Sciences, 53, 86–98. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2015.07.003

- Read, C., & Szokolszky, A. (2018). An emerging developmental ecological psychology: Future directions and potentials. Ecological Psychology, Special Issue Part II, 30(2), 174–194. doi:10.1080/10407413.2018.1439141

- Reynolds, R. E., & Ortony, A. (1980). Some issues in the measurement of children’s comprehension of metaphorical language. Child Development, 51, 1110–1119. doi:10.2307/1129551

- Richardson, M. J., Shockley, K., Fajen, B. R., Riley, M. A., & Turvey, M. T. (2009). Ecological psychology: Six principles for an embodied–Embedded approach to behavior. In A. G. Calvo (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive science: An embodied approach (pp. 159–187). Amsterdam, ND: Elsevier.

- Rietveld, E., Denys, D., & Van Westen, M. (2018). Ecological-enactive cognition as engaging with a field of relevant affordances: The skilled intentionality framework (SIF). In A. Newen, L. DeBruin, & S. Gallagher (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of 4E cognition (pp.41-70), Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

- Rietveld, E., & Kiverstein, J. (2014). A rich landscape of affordances. Ecological Psychology, 26(4), 325–352. doi:10.1080/10407413.2014.958035

- Rosa, E. M., & Tudge, J. (2013). Urie Bronfenbrenner’s theory of human development: Its evolution from ecology to bioecology. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5(4), 243–258. doi:10.1111/jftr.12022

- Rosenberg, Dent, C. (1990). Visual and verbal metaphors: developmental interactions. Child Development, 61(4), 983-994.

- Rucinska, Z. (2014). Basic pretending as sensorimotor engagement?. In J. M. Bishop & A. O. Martin (Eds.), Contemporary sensorimotor theory: A brief introduction (pp. 175–187). Switzerland, Springer International Publisher.

- Rucinska, Z. (2016). What guides pretence? Towards the interactive and the narrative approaches. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 117–133. doi:10.1007/s11097-014-9381-z

- Rucinska, Z., & Reijmers, E. (2015). Enactive account of pretend play and its application to therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 175. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00175

- Shaw, R., Turvey, M. T., & Mace, W. (1982). Ecological psychology: The consequence of a commitment to realism. Cognition and the Symbolic Processes, 2, 159–226.

- Stewart, J., Stewart, J. R., Gapenne, O., & Di Paolo, E. A. (2010). Enaction: Toward a new paradigm for cognitive science. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

- Still, A., & Costall, A. (Eds.). (1992). Against cognitivism. Birmingham, UK: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Still, A., & Good, J. (1998). The ontology of mutualism. Ecological Psychology, 10(1), 39–63. doi:10.1207/s15326969eco1001_3

- Still, A., & Good, J. M. (1992). Mutualism in the human sciences: Towards the implementation of a theory. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 22(2), 105–128. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5914.1992.tb00212.x

- Szokolszky, A. (1996). Using an object as if it were another: The perception and use of affordances in pretend object play. CT, USA: University of Connecticut. UNI order number: AAM9605501 Dissertation Abstract International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Szokolszky, A. (2004). A tárgy mint cselekvési lehetőség./The object as possibility for action. In Á. Kapitány & G. Kapitány (Eds.), Termékszemantika (pp. 78–87). Budapest, Hungary: Magyar Iparművészeti Egyetem.

- Szokolszky, A. (2006). Object use in pretend play: Symbolic or functional? In A. Costall & O. Dreier (Eds.), Doing things with things: The design and use of everyday objects (pp. 67–86). London, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

- Szokolszky, A., & Read, C. (2018). Developmental ecological psychology and a coalition of ecological–relational developmental approaches. Ecological Psychology, 30(1), 6–38. doi:10.1080/10407413.2018.1410409

- Szokolszky, A., & Szalkai, A. (in progress). A dialogue study of metaphor use by children.

- Thibault, P. J. (2011). First-order languaging dynamics and second-order language: The distributed language view. Ecological Psychology, 23(3), 210–245. doi:10.1080/10407413.2011.591274

- Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Turvey, M. T., Shaw, R. E., Reed, E. S., & Mace, W. M. (1981). Ecological laws of perceiving and acting: In reply to Fodor and Pylyshyn (1981). Cognition, 9(3), 237–304.

- Van Den Herik, J. C. (2018). Attentional actions–An ecological-enactive account of utterances of concrete words. Psychology of Language and Communication, 22(1), 90–123. doi:10.2478/plc-2018-0005

- van Dijk, L., & Rietveld, E. (2017). Foregrounding sociomaterial practice in our understanding of affordances: The skilled intentionality framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1969. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01969

- von Bertalanffy, L. (1938). A quantitative theory of organic growth (inquiries on growth laws. II). Human Biology, 10(2), 181–213.

- Vosniadou, S. (1987). Children and metaphors. Child Development, 58, 870–885. doi:10.2307/1130223

- Vosniadou, S., & Ortony, A. (1983). The emergence of the literal-metaphorical-anomalous distinction in young children. Child Development, 54(4), 154–161.

- Vosniadou, S., Ortony, A., Reynolds, R. E., & Wilson, P. T. (1984). Sources of difficulty in the young child’s understanding of metaphorical language. In Child Development 55(4), 1588–1606.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1981). The genesis of higher mental functions.In: J.V. Wetsch (ed). The concept of activity in Soviet psychology (pp.144-188). Minnesota: M.E. Sharpe.

- Warren, R., & Wertheim, A. H. (2014). Perception and control of self-motion. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Winner, E. (1979). New names for old things: The emergence of metaphoric language. Journal of Child Language, 6(3), 469–491.

- Witherington, D. C., & Heying, S. (2013). Embodiment and agency: Toward a holistic synthesis for developmental science. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 44, 161–192.

- Zukow-Goldring, P. (2012). Assisted imitation: First steps in the seed model of language development. Language Sciences, 34(5), 569–582.

- Zukow-Goldring, P., & de Villiers Rader, N. (2013). Seed framework of early language development. The Dynamic Coupling of Infant-caregiver Perceiving and Acting Forms a Continuous Loop during Interaction. IEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Development, 5(3), 249–257.

- Zukow-Goldring, P., & Rader, N.D. (2001). Perceiving referring actions. Developmental Science, 4(1), 28–30.