?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This research article aims to analyze the effect of female empowerment on gender-based intimate partner violence against women in Ecuador, a country where levels of violence stand out in the region. We apply an instrumental variable regression model using official data from the 2019 National Survey on Family Relations and Gender Violence against Women. We found a negative association between women empowerment and intimate partner violence, that is, greater empowerment of women is associated with lower manifestations of intimate partner violence. We also find a positive reverse association between manifestations of intimate partner violence against women and empowerment. This means that a woman who has been a victim of intimate partner violence will be more willing to embrace ideals that empower women. From a public policy perspective, government engagement with promotion of female empowerment will reduce intimate partner violence against women and the costs associated with it.

Introduction

Goal five of the United Nations (UN) 2030 agenda seeks to achieve gender equality as well as empower women and girls by eliminating all forms of violence against women and girls UN (Citation2015). Gender-based violence is defined as any act of sexist violence that results in possible or actual physical, sexual or psychological harm in public or private life WHO (Citation2012). It encompasses acts such as child sexual abuse, stalking, sexual coercion, rape and intimate partner violence (IPV), the latter being the most widespread form of gender-based violence (L. Heise et al., Citation2002). How female empowerment influences IPV against women is the focus of this paper.

IPV against women is a pervasive and complex problem that has significant impacts on the lives of millions of women – and their families- worldwide. While numerous studies have examined the risk factors associated with IPV, such as poverty, alcohol and drug abuse, and mental health issues (Bucheli & Rossi, Citation2019; Yapp & Pickett, Citation2019), relatively few studies have explored the potential protective factors that may reduce the likelihood of IPV. One such protective factor that has received increasing attention in recent years is female empowerment (Eggers Del Campo & Steinert, Citation2022).

Female empowerment refers to the process by which women gain greater control over their lives, achieve greater autonomy, and acquire the skills and resources necessary to make meaningful choices about their futures. Empowerment can take many forms, including economic empowerment through access to education and employment, political empowerment through participation in decision-making processes, and social empowerment through improved access to healthcare, legal protection, and social support networks.

Empowerment can increase women’s ability to recognize and resist abusive behaviors, improve their economic and social status, and increase their access to resources and support services. However, the relationship between female empowerment and IPV is complex, and it could be the case that increased empowerment may actually increase the risk of IPV in certain contexts. In light of these complexities, it is important to examine the relationship between female empowerment and IPV empirically in greater detail.

Public policies focused on the eradication of gender-based violence against women are of vital importance as they promote, protect, guarantee, and respect women’s rights. Over the years, Ecuador has implemented norms and plans for the prevention and eradication of gender violence, including: the National Plan for the Eradication of Gender Violence against Children, Adolescents and Women, the Electoral and Political Organizations Law, the National Development Plan, Decree 371, which adopts the 2030 agenda for development, the Comprehensive Organic Law to Prevent and Eradicate Violence against Women and currently the National System for the Eradication of Gender Violence (Moreira Cedeño et al., Citation2020).

It is important to understand that female empowerment is a process that comes from the capacity obtained by women to make strategic decisions in different spheres of their lives (Kabeer, Citation1999); however, the behaviors that define empowerment in one society may be irrelevant in others (Gram et al., Citation2019; Malhotra & Schuler, Citation2002). For this reason, we focused on empowerment of women in Ecuador. Vara-Horna (Citation2020) establishes that the economic costs of gender-based intimate partner violence for the year 2019 are equivalent to 4.6 billion USD in this country, or 4.28% of GDP. 49.9% of these costs are assumed by women, their households, and micro-enterprises, while 38.8% by medium and large companies and, finally, 11.3% by the State (Vara-Horna, Citation2020). Women’s empowerment not only allows women to achieve strategic interests (Calvès, Citation2009), but it is also fundamental for development and peace UN (Citation1996).

Ecuador is a middle-income economy (The World Bank, Citation2020) that has presented significant levels of gender violence against women, being that by 2019, 65 out of every 100 women report to have experienced some type of violence and 43 out of every 100 report to have been victims of intimate partner violence INEC (Citation2019). In addition, Ecuador recorded 195 cases of feminicide in 2021, reaching a rate of two victims per 100 000 women, 72 of these cases were committed by the victim’s partner or ex-partner (Mundosur, Citation2022). For this investigation, data from the National Survey on Family Relations and Gender Violence against Women -ENVIGMU- conducted by the Ecuadorian Institute of Statistics and Census -INEC-, for the year 2019 have been used.

According to Arango and Rubiano-Matulevich (Citation2019), Ecuador has the second highest prevalence rate of physical and/or sexual IPV in Latin America, with a rate of 40.4%, just after Bolivia, which has a rate of 58.5%. The other Andean countries, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela, present rates of 33.3%, 31.2%, and 17.9%, respectively. In contrast, countries like Uruguay and Brazil have rates of 16.8% and 16.7%, respectively. Based on the above information, we attempt to empirically verify the existence of a relationship between female empowerment and intimate partner violence.

Literature review

Women’s empowerment

There are many definitions of female empowerment, we reference Calvès (Citation2009) who points out that women’s empowerment is comprised of three types of powers. First, the “power to” which is a creative power used to achieve objectives. Second, the “power with” defined as a collective political power present in social organizations. Finally, the “power from within” referring to self-confidence and the ability to undo the internalized effects of oppression. In a previous study, Batliwala (Citation1994) defines empowerment as the process of transforming power relations between individuals and social groups. This process can be accomplished by challenging the ideology that justifies inequity, changing how economic, natural and intellectual resources are accessed and controlled, and transforming the structures that reinforce and preserve existing power systems.

Female empowerment is not a sporadic phenomenon, but it is the result of a historical construction. In this line, Simon (Citation1994) points out that the notion of empowerment has as its source subjects such as feminism, Gandhism, Freudian psychology, theology and the U.S. Black Power movement. These subjects have guided the social interventions of marginalized populations throughout history. In that sense, Freiré (Citation1973) suggests that social uprisings arise from critical and reflexive consciousness-raising, with the aim of ensuring both individual and collective well-being through active participation in decision-making.

From a gender perspective, female empowerment is the result of a series of struggles by and for women; however, it was not until the 1960s that feminism became a social movement (Gamba, Citation2008; Pinto, Citation2003). The core of this movement is based on the slogan “the personal is political” which states that social change in economic structures is based on the evolution of gender relations (Gamba, Citation2008). During the so-called “First Wave of Feminism,” three main lines emerged: radical, socialist and liberal, which institutionalized the movement in governments and international organizations (Pinto, Citation2003).

Radical feminism is totally independent of political parties and trade unions, as a result it relies on the creation of nonhierarchical, solidarity-based, and horizontal organizations. It aims to regain women’s sexual and reproductive control, as well as economic, social, and cultural power. Socialist feminism and liberal feminism propose a different type of power, since they pronounce themselves for equality, however, this notion acquires different meanings for each case. Socialist feminism, although it coincides with some contributions derived from radical feminism, it proposes that feminism is a way to confront capitalism, associating class struggle with women’s struggle. On the other hand, liberal feminism considers capitalism as a source of possibilities toward gender equality, and claims that oppression is rooted in traditional culture (Gamba, Citation2008).

The radical line of feminism led to the formal term of “empowerment” and its inclusion in development discourses. This emerges as a challenge to the idea that economic independence and the fulfillment of basic needs are enough to reinforce women’s power (O’neil et al., Citation2014). Based on this analysis, the concept of empowerment emerges as a tool to achieve women’s strategic interests, starting from a radical transformation of the economic, legal and social structures that continue to perpetuate the dominance of gender, race and class, hindering the creation of equal relations in society (Calvès, Citation2009).

During the boom of feminist movements, the United Nations convened the Fourth World Conference on Women: Action for Equality, Development and Peace in Beijing in 1995, which marked the beginning of the agenda for women’s empowerment and it is considered the key global policy document on gender equality (UN WOMEN, Citationn.d.). The conference unanimously approved the “Platform for Action,” whose objective was to eliminate the obstacles that obstruct or prevent the active participation of women in every life sphere (economic, social, cultural, and political). This conference emphasized that equality between men and women is a matter of human rights and a necessary condition for social justice, as well as being a basic requirement for development and peace UN (Citation1996).

Empowerment as a process and multidimensional concept

During the 1990s, the discourse on empowerment, gender and development gained strength, particularly in Latin America and Southeast Asia (Calvès, Citation2009). Along these lines, Batliwala (Citation1993) points out that empowerment has two main attributes: the control over resources (personal, physical, human, intellectual and financial), and control over ideology (beliefs, values, and attitudes). Thus, she concludes that, if power means control, then empowerment is the process of acquiring control. Kabeer (Citation1999) also conceptualizes empowerment as a process, pointing out that it is based on women’s ability to make strategic decisions about their lives through three interrelated elements: the access to resources, the way they use these resources to define their objectives, and the achievements resulting from these actions.

Kabeer (Citation1999) emphasizes the multifaceted nature of empowerment as a process. Considering this, O’neil et al. (Citation2014) concludes that empowerment should be treated and understood as a multidimensional process made up of four dimensions (see ).

In this sense, each of the dimensions of empowerment can be understood as follows:

Psychological empowerment: when women believe in their ability to make or influence decisions. This type of empowerment is about confidence and self-esteem.

Social empowerment: when women acquire the ability to make or influence decisions about their social interactions, reproduction, health, and education.

Economic empowerment: when women acquire the ability to act, make or influence decisions about their participation in the labor market, in unpaid work and about the allocation and use of their household assets.

Political empowerment: when women acquire the ability to influence the norms or rules that govern society, as well as resource distribution decisions. It can be exercised through public or private organizations, about formal or informal rules, and can occur at the household, community, sub-national and national levels.

Measuring empowerment: Indicators and context

In the light of empowerment as a very wide concept, it is difficult to build indicators for its measurement (Gram et al., Citation2019). Casique (Citation2010) asserts that this is due to the fact that the multidimensional nature of this process leaves room for the possibility for a woman with a high level of empowerment in one or several dimensions, and at the same time a low level in another or others (for example, a woman with high freedom of mobility, but low decision-making power), consequently faces the difficulty of sorting the dimensions and their elements, since the importance of these dimensions differs between individuals and their environment. In fact, the behaviors that define empowerment in one society may be irrelevant in others (Gram et al., Citation2019; Malhotra & Schuler, Citation2002). In order to highlight this situation, Malhotra and Schuler (Citation2002) contrast how in rural Bangladesh the ability of a woman to attend a health center without requesting permission from a male member of the household can be translated as empowerment, although this is not the case in the urban area of Peru, which is why they assert that the context allows us to identify whether the individual or household level of empowerment is really a determining factor for development.

Due to the fact that the notion of empowerment varies according to context, several researchers have found the development of indicators a challenging process (Kabeer, Citation1999; Malhotra & Schuler, Citation2002; Richardson, Citation2018). The difficulty in measuring empowerment, boils down in what weights should be assigned to each dimension and what valuation each element should have within it, since as Kabeer (Citation1999) points out, not all societies will give the same importance to the same achievement.

Starting from a more general approach, Kabeer (Citation1999) agrees that a possible solution to the measurement problem is to study certain universally validated functions, that is, those functions that are based on the satisfaction of basic welfare and survival needs; however, these functions alone are not enough, since they leave aside the focus of this study, and they contradict the previously established conceptualization of empowerment.

Since a general approach is not enough, García (Citation2003) and Gram et al. (Citation2019) claim that it is possible to carry out social research on empowerment starting from it manifestations in different spheres of life. These manifestations can be studied by surveys, as they capture reality better. Researches that have applied indicators in their studies have allowed international and inter-regional comparisons in terms of empowerment, however, it is here where the argument that an indicator that has been developed in one context may not be appropriate for another arises (Malhotra & Schuler, Citation2002).

Several authors, in their pursuit to measure the concrete manifestations of independence, control over one’s life and acting according to one’s own interests, happened to concur with each other on several dimensions (García, Citation2003). Hashemi et al. (Citation1996) develop eight indicators that can partially capture empowerment, these are: i) mobility, ii) economic security, iii) ability to make small purchases, iv) ability to make large purchases, v) inclusion in household decisions, vi) relative freedom from family domination, vii) political and legal awareness, and viii) participation in political campaigns and protests. Malhotra and Schuler (Citation2002) through a compilation of empirical studies on indicators of individual and household empowerment, grouped the indicators in two: i) most frequently used indicators: household-level decision-making (finances, resource allocation, expenditures, social and domestic issues, and parenting issues), access to control over resources (access to and control over cash, income, assets, unearned income, welfare vouchers, household budget, and participation in paid employment), and freedom of mobility, ii) less frequently used indicators: economic contribution to the household, time spent on household chores, freedom from violence, administration and knowledge (farm management, accounting and loan knowledge), public space (political participation, confidence in community actions and development of social and economic collectives), marriage/relatives/social support (support networks, social status of the family of origin, assets brought into marriage and control over choice of spouse), couple interactions (communication and negotiation about sexual relations) sense of appreciation in the household and sense of self-worth. García (Citation2003) summarizes direct women’s empowerment indicators in six matters. i) women’s decision-making participation in household aspects such as education, health, marriage, shopping, spending and control over their reproductive behavior; ii) free mobility which considers demographic characteristics, given that female seclusion is a crucial aspect of gender differentiation in the Asian region, however it is still a relevant element for the case of Mexico (Casique, Citation2010; García & de Oliviera, Citation2000); iii) access and control of economic resources; iv) being free from domestic violence, which is one of the least clear dimension since it is not mentioned as much; it includes freedom from threats and fear from their partner; v) pro-gender equity positions (here the subjective aspects of the perception of gender inequality are considered); and, vi) couple and household structure, which includes being able to choose the spouse and whether to cohabitate with the in-laws.

Empowerment indicators cannot accurately measure how much a woman’s capacity to make decisions changes. Although there is consensus on common elements, empowerment has an internal characteristic that can only be understood by the individual due to environment in which women are located (Kabeer, Citation1999). For this reason, the selection of indicators to be used relies on the researcher´s purposes, which should be based on the socio-cultural context and the availability of information resources (Gram et al., Citation2019).

Empowerment and gender-based violence

Gender-based violence is defined as “Any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life.” WHO (Citation2012). Such definition is an international consensus that covers child sexual abuse, stalking, sexual coercion, rape, and intimate partner violence (Russo & Pirlott, Citation2006). In addition, intimate partner violence against women is the most widespread form of gender-based violence (L. Heise et al., Citation2002), and can manifest itself in emotional, psychological, physical, sexual or economic forms (Casique, Citation2010). This type of gender-based violence is a complex phenomenon, which is influenced by factors of the woman, her partner, and the community. In other words, it is a result of both situational and socio-cultural factors (Angelucci & Heath, Citation2020; L. Heise et al., Citation2002).

Gender-based violence against women should be viewed as those acts that have been shaped through gender roles and gender status in a society (Russo & Pirlott, Citation2006). Social structures themselves often legitimize violence against women by reflecting unequal gender relations, which reinforce patriarchy by normalizing women’s subordination and leading to the misconception that it should be both natural and expected ((Rudman, Citation1998). It has been shown that gender-based violence against women is more common in places in which the concept of masculinity is linked to honor or dominance, with dominance being understood as “power over” (L. L. Heise, Citation1998; L. Heise et al., Citation2002). Isolation and lack of social support (which would configure a low level of social and political empowerment) together with behaviors that legitimize sexism, have resulted in higher levels of violence (L. Heise et al., Citation2002; Koenig et al., Citation1999). These behaviors, which are based on cultural norms such as physical punishment for women, condone violence and promote the perception that men “own” them (L. L. Heise, Citation1998; Levinson, Citation1989). Several investigations have concentrated their efforts into conceptualizing and studying gender-based violence, observing how some of these acts, especially sexual violence such as rape, can be translated as a form of power and control over women (Brownmiller, Citation2005; Dobash & Dobash, Citation1979; Medea & Thompson, Citation1974; Russell, Citation1975). It is in this approach of “ownership” or “power over” that gender-based violence against women opposes the previously established fundamentals of empowerment. Furthermore, both concepts vary according to the context, and they coincide to establish dimensions (psychological, economic, sexual and political) that are interrelated.

Given the complexity of the concepts, defining a relationship is more than it seems, as the direction of this relationship can vary according to the context. In microfinances, sometimes empowering women economically can increase the risk of violence (Angelucci & Heath, Citation2020) as these situations may not fit with the established social prescriptions and some men may perceive this as a threat to their status quo or as a disruption to their authority and power (Casique, Citation2010); however, evidence also suggests that this risk may decrease as women become more familiar with economic empowerment (Ahmed, Citation2005). Similarly, the literature also shows that economic empowerment can be seen as a protective mechanism for women against violence (Hashemi et al., Citation1996; Kabeer, Citation1998). In the case of Ecuador, Vara-Horna (Citation2013) concludes that in order to reduce violence against women, economic empowerment is not enough, as it must be backed up with financial training, networks or partnerships among women, and informative materials on gender-based violence.

Sexual violence and obstetric-gynecological violence can lead to women’s inability to make decisions about their reproductive lives, L. Heise et al. (Citation2002); Russo and Denious (Citation2001) argue that this is because violent partners are more likely to refuse to use condoms. The inability to decide about their reproductive life can potentially translate into an unwanted pregnancy, which has a direct impact on women’s ability to make present and future decisions in other spheres of their lives (employment, childbearing practices, childcare, and household dynamics) (Samari, Citation2017).

An unintended pregnancy can increase a woman’s dependence on her partner, Kalmuss and Straus (Citation1982) associate this increase with a greater likelihood of experiencing physical abuse, however, in some cases a woman’s fertility can also positively influence her empowerment as she gains power in other ways, such as her inclusion in society, and decision-making in parenting (Hindin, Citation2000). However, women’s empowerment can also be negatively affected as the welfare of children can become a way to exert a greater degree of threat on women (as cited in Russo & Pirlott, Citation2006).

Setting the context: gender-based violence against women in Ecuador

Due to the situational nature of both empowerment and violence, a delimitation of the study is of utmost importance. Ecuador is a country located on the northwestern coast of South America, its territorial extension is 283,560 and it has approximately 18 million inhabitants by the year 2022. It is divided into four geographic regions (Coast, Highlands, East, and Galapagos) and has 24 political-administrative divisions called provinces. In the Ecuadorian case, Ley Orgánica Integral Para Prevenir y Erradicar La Violencia Contra Las Mujeres (Citation2018) defines gender-based violence as any action or behavior that is committed against women, simply by the fact that they are women, that causes them death, harm and/or physical, sexual, psychological, economic, gynecological- obstetric suffering, in the public or private sphere. The forms of violence recognized in this law are:

Physical violence: Any action (or lack of action) that causes (or is likely to cause) physical harm, pain, suffering or death. Any form of physical abuse or punishment, whether it results in obvious internal or external injury.

Psychological violence: Any action (or lack of action) that causes (or is likely to cause) emotional harm, diminish self-esteem, affect honor, bring discredit, degrade the person.

Sexual violence: Any action that violates the right to sexual integrity and the right to free decision and consent over one’s own sexual and reproductive life. It attacks the dignity and integrity of the victim and often also coerces the victim through threats, blackmail, imposition, even within marriage.

Economic and property violence: Any action (or lack of action) that results in the reduction or weakening of a woman’s economic resources or property, including within the marital partnership in marriage or property partnership in common-law marriage.

Symbolic violence: All actions that, through the production or reproduction of messages, symbols, signs, or political, economic, social, cultural, or religious impositions, transmit, replicate, and strengthen women’s inequality, exclusion, and subordination.

Political violence: Any action that a person or collective exercises against a woman candidate or elected woman, leader, human rights defender, member of a feminist organization, declared feminist, etc., to prevent her from continuing with her work, limiting her functions and opportunities, forcing her in any way to do something that she does not want to do and that goes against her functions.

Obstetric and gynecological violence: Any action (or lack thereof) that prevents or limits in any way the free decision of women about their sexual and reproductive lives. It includes the limitation or absence of gynecological-obstetric health care for pregnant or non-pregnant women; imposition of medical practices, forced sterilization, absence, or abuse of medication, among others.

According to the National Survey on Family Relationships and Gender Violence against Women conducted by the Ecuadorian Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), by 2019 in Ecuador 65 out of every 100 women have suffered some type of violence in their lifetime, 57 out of every 100 have suffered psychological violence, 36 out of every 100 physical violence, 33 out of every 100 sexual violence and 17 out of every 100 economic and property violence.

In 2011, 48 out of every 100 Ecuadorian women have suffered some type of intimate partner violence, the percentage of women by province is 63.7% in Morona Santiago, the highest in the country, followed by 60.3% in Tungurahua, while Manabi is the province with the lowest percentage with 36.1% INEC (Citation2011), 2019b, (Citation2019). Regarding the year 2019, a decrease is evident, 43 out of every 100 Ecuadorian women have suffered some type of violence by their partner, the percentage of women by province is 60.6% in Morona Santiago, which remains the highest in the country, followed by 58.8% in Napo, and the province with the lowest percentage is Bolivar with 33.1% INEC (Citation2011), 2019b, (Citation2019). According to the marital status, the percentage of women who have experienced some type of intimate partner violence is 48.5% in 2011 and 46.7% in 2019 in married women, 69.2% in 2011 and 65.7% in 2019 in separated women, and 30.6% in 2011 and 17% in 2019 in single women INEC (Citation2011), 2019b, (Citation2019).

Gender-based violence against women includes a wide variety of acts, some of which can lead to murder WHO (Citation2012). Ecuadorian law defines femicide as the result of power dynamics manifested in any type of violence that kills a woman just because she is a woman or because of her gender condition. According to La Fiscalía General del Estado (Citation2021) from August 10, 2014 to January 03, 2021 a total of 450 victims of femicide were registered in Ecuador. As for the relationship with the victim, the spouse accounted for 17.8% of the cases, the partner for 13.1%, the ex-spouse or ex-partner for 4.9%, the cohabitantFootnote1 for 34.22% and other for 14.89% FGE (Citation2021).

In a wider approach, the Latin American Map of Femicides (Mundosur, Citation2022) reports that in 2021, eight Latin American countries registered a total of 1,422 cases of femicides, 195 of them corresponding to Ecuador, which is equivalent to a rateFootnote2 of two victims of femicide per 100,000 women. Of these cases, in 72 of them, there was a partner or ex-partner relationship between the victim and her aggressor.

Data and methodology

Data

According to García (Citation2003) and Gram et al. (Citation2019), analyzing empowerment through surveys allows capturing its manifestations in different spheres of life, so for this study we used data obtained from the ENVIGMU 2019 INEC (Citation2019), since it focuses on measuring the facts that investigate violence within the framework of both national and international regulations.

ENVIGMU 2019, is a survey conducted through probability sampling in three selection steps: selection of clusters by stratum, selection of 8 households per cluster, and selection of one woman per household (Hidalgo et al., Citation2018). Its target population includes women aged 15 years and older who are habitual residents of rural and urban areas of Ecuador. The data were obtained through a direct survey conducted between July and August 2019, with a total of 2,606 clusters 20,848 households and an effective sample of 17,211 women INEC (Citation2019).

Considering that the purpose of this study is to analyze the existing relation between intimate partner violence and female empowerment, we proceeded to select those women married or in union between 15 and 65 years of age resulting in a final population of 9,515 women.

Methodology

The literature review shows that there is a relationship between intimate partner violence and female empowerment. What is not clear is the direction of association in this relationship: is female empowerment a factor that decreases a woman’s likelihood of experiencing intimate partner violence, or does an empowered woman, by opposing unequal gender relations, ¿have an increased likelihood of experiencing intimate partner violence?

In order to answer these questions it is necessary to consider a possible endogeneity problem. Gujarati and Porter (Citation2011) point out that this problem can be solved by means of an instrumental variables model. For which, the following equation has been established:

Where:

, index that captures violence manifestations that the i woman has experienced by her current partner.

, is a vector of control variables, made up of socio-demographic characteristics, history of violence and indicators of women’s resources.

a concept that is approximated by the gender role ideology index of the i woman.

, is the model error term.

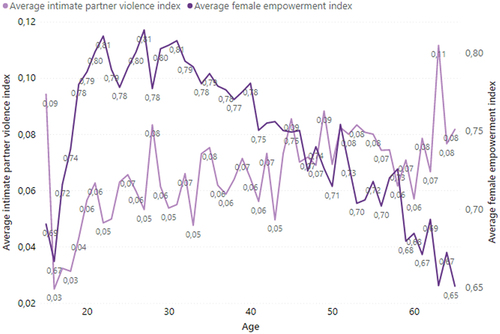

The intimate partner violence index obtained using a method of aggregation based on 23 questions from section 7A of the survey. A value of one has been assigned to those answers confirming violence (sexual, physical, psychological and/or patrimonial) by a partner and 0 otherwise (see annex 1 of the supplementary material). Female empowerment (exogenous variable of interest) reflected through the gender role ideology index has also been built through an aggregation method based on 14 questions corresponding to section 9 of the survey, where a value of one has been assigned to those opinions that disapprove of unequal gender relations and 0 otherwise (see annex 2 of the supplementary material). shows how these indexes behave according to age. Women at 15 and 63 years of age have a higher average intimate partner violence index with 0.09 and 0.11, correspondingly. Women at 22, 27 and 31 years of age are those who show a higher average female empowerment index with 0.81.

Figure 2. Average intimate partner violence index and average female empowerment index behavior according to women’s age.

Bearing in mind that the endogeneity problem can occur due to the absence of relevant variables, a series of controls have been included. These control variables include area of residence (urban or rural), level of education re-categorizedFootnote3 taking into account the SITEAL report (Citation2019),Footnote4 ethnicity,Footnote5 age, age squared, employment status (consider a woman as working if she has ever worked during her life), number of children, number of unions or marriages, age at first sexual intercourse, childhood violence background (of both the woman and her partner), and indicators of women’s resources.

Another possible cause of endogeneity is the reverse association between intimate partner violence and female empowerment. To address this problem, we will use the power of decision making instrument. This instrument shows a high correlation with female empowerment, as Casique (Citation2010) states that it measures women’s intervention in household decision-making. To build this indicator, the author has assigned a higher value to decisions made solely by the woman compared to those made by the couple and joint decisions.

Our instrument, the power of decision-making index, reflects the ability of the to make decisions in different spheres of her life (education, work, mobility, personal finances, community participation, child rearing, sexual relations, reproduction, household and personal purchases, and personal care). It should be mentioned that unlike what Casique (Citation2010) did, this indicator guarantees a higher value for women’s decisions regarding their lives, but also for those made jointly with their partners, in this way it follows the empowerment definition and doesn’t reflect any type of “power over” exercised by the woman, which guarantees a low correlation with the intimate partner violence index. It has been built from an aggregation method based on 15 questions from section 7D of the survey, assigning a value of one to each response that reflects women’s power of decision making and 0 otherwise (see annex 5 of the supplementary material), detail the descriptive statistics of the variables used in this study.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of quantitative variables.

Table 2. Frequencies of qualitative variables.

A positive relationship between empowerment and power of decision making can be interpreted as an environment in which it can be practiced, while a negative relationship can be understood as a palpable reflection of the existing power asymmetry and the oppression experienced by women. This instrument meets the conditions of exogeneity and relevance, which allows us to obtain consistent and unbiased estimators (Wooldridge, Citation2015).

Results

First, we present the basic results of our model, those obtained from the ordinary least squares estimation (see ) to identify associations among variables. These results indicate that intimate partner violence and female empowerment have a negative relation. The estimated coefficients are significant at 5% and 10%. The coefficient resulting from the estimation in column (1) indicates that a one percentage unit increase in a woman’s intimate partner violence index is associated with a decrease (−.0228) in female empowerment index. The relationship and significance at 10% persist after including the violence background (column (2)). When the resource indicators are included, the relationship is maintained; however, it is possible that the significance has been affected by the endogeneity problem (column (3)).

Table 3. OLS results.

The estimation using the instrumental variables method is presented in ; column (1) shows the first stage. The power of decision making instrument has a positive and statistically significant effect on female empowerment.

Table 4. IV results.

For model validation, we performed the under-identification, weak identification, over-identification and endogeneity tests. The Kleibergen-Paap rk LM test, in which the null hypothesis states that the equation is under-identified, verifies whether the excluded instruments are relevant, meaning that they are correlated with the endogenous regressors. Since the p-value is 0.0000 there is statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

The Cragg Donald test, whose null hypothesis states that the equation is weakly identified. This test analyzes the suitability of the instruments used in the model in defining the endogenous variable. A statistic with a value of 154.935 has been obtained, which exceeds the critical stock-yogo values, so there is statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

The Hansen J statistic is a test regarding the over-identification of the constraints, it cannot be used in an exactly identified equation as in our case.

The endogeneity test, whose null hypothesis states that the specified endogenous regressors can be treated as exogenous. With a p-value of 0.000, there is statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis, which confirms the relationship between female empowerment and intimate partner violence and therefore validates our model.

The instrumental variable regression indicates that the effect of female empowerment on intimate partner violence is also negative and statistically significant at 1% (see column (2)). Specifically, it establishes that the increase of one percent in female empowerment is associated with a decrease of (−.283) in the rate of violence against women by their partners.

Considering the over-identification test, we can conclude that the reverse association problem has been solved. Given that the parameter (−.283) is greater than that obtained by least squares (−.014), this difference can be interpreted as an indicator that the reverse association between intimate partner violence and female empowerment is positive. That is, a woman who has suffered greater manifestations of intimate partner violence will be more willing to embrace empowerment ideals. This is in line with the definition that empowerment is a process of transforming existing power structures.

With regards to the socio-demographic characteristics of women, the results indicate that a married or unmarried woman with a secondary, superior and postgraduate level of education is more likely to suffer intimate partner violence compared to an illiterate woman. Likewise, a married or unmarried woman who works is more likely to suffer intimate partner violence than a woman who does not work. As mentioned by Vacacela Márquez et al. (Citation2022), these results can be interpreted as a consequence of the challenge to the patriarchal system, which expects women to focus on caregiving tasks. They may also mean that, in Ecuador, women’s empowerment is not supported by men (Rahman et al., Citation2011).

Given that ethnic self-identification was not significant, it can be concluded that ethnicity is not a determining factor for intimate partner violence against women. In other words, this form of violence against women does not distinguish between ethnic groups.

The age of women is also a determinant of intimate partner violence against women. A younger woman is more prone to this form of violence (Peterman et al., Citation2015; Rennison, Citation2001; Speizer & Pearson, Citation2010; Wado et al., Citation2021). Additionally, a quadratic relation between age and intimate partner violence against women is confirmed, that is, as the woman gets older, the probability of suffering IPV increases until a certain age in which the probability decreases over time.

A negative and statistically significant relationship between age at first sexual intercourse and intimate partner violence against women is evident. Early sexual initiation in women increases the likelihood of intimate partner violence (Yoshihama & Horrocks, Citation2010). It is worth noting that 2.29% of the sample is composed of young girls from one to twelve years old (see Annex 8), a range that corresponds to infants (Moreno, Citation2007), which could be an indication of child sexual abuse, as it is defined by the distortion of any possible freely consented relationship (Echeburúa & de Corral, Citation2006).

The antecedents of violence indicate that a woman who has suffered or witnessed violence during childhood by her family of origin is more likely to be a victim of violence by her partner by 2.3% and 1.8% respectively. Likewise, a woman whose partner has suffered or witnessed violence during childhood from (the) his family of origin is more likely to suffer manifestations of violence from him by 2.5% and 2.9% respectively. This matches the concept of intergenerational transmission of violence. This concept can be seen in the study by Ehrensaft and Langhinrichsen-Rohling (Citation2022), which shows how infants who have grown up in an environment where they have been exposed to violence between parents or caregivers are more likely to become perpetrators or victims of intimate partner violence as adults.

A woman who has no money for personal expenses is 2.5% more likely to experience greater manifestations of intimate partner violence. Kilburn et al. (Citation2018), explain how having these types of resources, resembles a prevention mechanism for intimate partner violence.

Discussion

In this research, the effects of empowerment have been analyzed with respect to the manifestations of gender violence against women by intimate partners. We have used information collected from the ENVIGMU for the year 2019 in Ecuador, a developing economy that has presented worrisome figures regarding gender violence against women, as well as a high rate of femicides in the region. An instrumental variable model has been employed in order to control possible endogeneity issues, through which it has been confirmed that greater empowerment of women is associated with lower manifestations of intimate partner violence, However, it is worth mentioning that once violence has manifested itself, women’s empowerment can be seen as a challenge to the patriarchal system, which is why the results reported that a married or unmarried woman with a secondary, superior and postgraduate level of education is more likely to suffer greater manifestations of intimate partner violence compared to an illiterate woman. Likewise, a married or unmarried woman who works is more likely to suffer intimate partner violence than a woman who does not work.

Our results also point to a positive reverse association between manifestations of intimate partner violence against women and empowerment. This means that a woman who has been victim of intimate partner violence will be more willing to embrace ideals that empower women. Intimate partner violence against women has multiple economic and social impacts. However, it is estimated that these impacts may be greater than those caused by other types of violence, including war, terrorism, and common crime (Vara-Horna, Citation2020).

With a focus on the economic sector, the study “The country costs of violence against women in Ecuador” estimates the costs caused by gender-based intimate partner violence against women in Ecuador. By 2019, these costs are equivalent to $4.6 billion dollars, or 4.28% of GDP. Vara-Horna (Citation2020) states that this estimate reflects only the lower limit, as it does not consider all possible associated costs. This total cost has been separated into four levels: at the individual, household, community, and state levels (see Annex 9 of the supplementary material). Of the total country cost of intimate partner violence against women, it is concluded that 49.9% will be borne by women, their households, and micro-enterprises, 38.8% by medium and large companies, and 11.3% by the State.

In light of our research findings, it is evident that Ecuador’s commitment to addressing intimate partner violence is reflected in the provision of comprehensive services, such as the “Service of Integral Protection” offered by the Secretariat of Human Rights (Subsecretaría Prevención y Erradicación de la Violencia contra la Mujer, Citationn.d.). Our study underscores the importance of such initiatives, as we have found a negative association between female empowerment and intimate partner violence, signifying that empowering women can contribute to reducing manifestations of violence. Moreover, our results suggest a positive reverse association, wherein individuals who have been victims of intimate partner violence may become more inclined to embrace empowerment ideals. These findings not only align with the intergenerational, intercultural, and gender-sensitive approach of the “Service of Integral Protection” but also emphasize the need for continued support and resources for programs aimed at promoting gender equity and reducing violence in Ecuador. From a policy perspective, our research underscores the potential impact of government engagement in empowering women, which can lead to a decrease in intimate partner violence against women and the associated social costs.

Given that this study analyzes intimate partner violence among women who are married, cohabitating, or living together, one limitation is that it does not consider intimate partner violence in dating situations. Also, given that it captures the total violence that women have suffered at the hands of their partners, it is limited in that it does not differentiate violence by type (physical, psychological, patrimonial, and sexual) nor does it establish possible risk factors for each type of violence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Cohabitant: The definition of cohabitant differs from the pre-established definitions as it is given by the woman herself, it is understood as the person with whom the woman maintains a relationship but also lives with her.

2 Ecuador’s women population in 2020: 8 819 233 (World Bank, Citation2020).

3 A detailed recategorization is shown in Annex 3 of the supplementary material.

4 UNESCO’s system of information of tendencies in education in Latin America.

5 Recategorized variable, details are shown in Annex 4 of the supplementary material.

References

- Ahmed, S. M. (2005). Intimate partner violence against women: Experiences from a woman-focused development programme in Matlab, Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 23(1), 95–101.

- Angelucci, M., & Heath, R. (2020). Women empowerment programs and intimate partner violence. AEA Papers & Proceedings, 110, 610–614. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20201047

- Arango, D. J., & Rubiano-Matulevich, E. (2019). Intimate partner violence in Latin America and the Caribbean needs urgent attention. https://blogs.worldbank.org/es/latinamerica/la-violencia-de-la-pareja-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe-requiere-atencion-urgente

- Batliwala, S. (1993). Empowerment of women in South Asia: Concepts and practices. In Asian-South Pacific Bureau of Adult Education; FAO’s Freedom from Hunger Campaign - Action for Development (pp. 88).

- Batliwala, S. (1994). The meaning of Women’s empowerment: New concepts from action | eldis. Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Empowerment and Rights, 17. https://www.eldis.org/document/A53502

- Brownmiller, S. (2005). Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (1975). https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-20005-001

- Bucheli, M., & Rossi, M. (2019). Attitudes toward intimate partner violence against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean. SAGE Open, 9(3), 215824401987106. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019871061

- Calvès, A.-E. (2009). « empowerment »: Généalogie d’un concept clé du discours contemporain sur le développement. Revue Tiers Monde, 200(4), 735–749. https://doi.org/10.3917/rtm.200.0735

- Casique, I. (2010). Factores de empoderamiento y protección de las mujeres contra la violencia / Factors of Women’s Empowerment and Protection from Violence. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 72(1), 37–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25677031

- Dobash, R., & Dobash, R. E. (1979). Violence against wives: A case against the patriarchy.

- Echeburúa, E., & de Corral, P. (2006). Secuelas emocionales en víctimas de abuso sexual en la infancia. Cuadernos de Medicina Forense, 43–44(43–44), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.4321/S1135-76062006000100006

- Eggers Del Campo, I., & Steinert, J. I. (2022). The effect of female economic empowerment interventions on the risk of intimate partner violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 23(3), 810–826. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020976088

- Ehrensaft, M. K., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2022). Intergenerational transmission of intimate partner violence: Summary and Current research on processes of transmission. Handbook of Interpersonal Violence and Abuse Across the Lifespan, 2485–2509. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89999-2_152

- FGE. (2021). Ecuador: Las Cifras del Femicidio. https://www.fiscalia.gob.ec/estadisticas-fge/

- Freiré, P. (1973). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Bloomsbury publishing. https://books.google.es/bookshl=es&lr=&id=OrVLDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR3&dq=The+Pedagogy+of+the+Oppressed&ots=JBjId72L0W&sig=FDKqyRFSxebnHG57wWxXZcV6sOk#v=onepage&q=ThePedagogyoftheOppressed&f=false

- Gamba, S. (2008). Feminismo: historia y corrientes. Diccionario de Estudios de Género y Feminismos, 3, 1–8. https://do i.org/http://www.mujeresenred.net/spip.php?article1397

- García, B. (2003). Empoderamiento y autonomía de las mujeres en la investigación sociodemográfica actual. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 18(2), 221–253. https://doi.org/10.24201/edu.v18i2.1162

- García, B., & de Oliviera, O. (2000). La dinámica familiar en la Ciudad de México y Monterrey. https://biblio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/catalog/resGet.php?resId=21181

- Gram, L., Morrison, J., & Skordis-Worrall, J. (2019). Organising concepts of ‘Women’s empowerment’ for measurement: A typology. Social Indicators Research, 143(3), 1349–1376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2012-2

- Gujarati, D., & Porter, D. (2011). In P. A. AMGH (Ed.), Econometría Básica. McGraw Hill.

- Hashemi, S. M., Schuler, S. R., & Riley, A. P. (1996). Rural credit programs and women’s empowerment in Bangladesh. World Development, 24(4), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00159-A

- Heise, L. L. (1998). Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Woman, 4(3), 262–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801298004003002

- Heise, L., Ellsberg, M., & Gottmoeller, M. (2002). A global overview of gender-based violence. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 78(S1), S5–S14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00038-3

- Hidalgo, N., Aguirre, C., Luna, I. M., Suasnavas, A., & Albán, A. (2018). Encuesta nacional sobre relaciones familiares y violencia de género contra las mujeres (envigmu) metodología. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Estadisticas_Sociales/Violencia_de_genero_2019/Principales%20resultados%20ENVIGMU%202019.pdf

- Hindin, M. J. (2000). Women’s autonomy, women’s status and fertility-related behavior in Zimbabwe. Population Research and Policy Review, 19(3), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026590717779

- INEC. (2011). Encuesta Nacional de Relaciones Familiares y Violencia de Género Contra las Mujeres. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec//documentos/web-inec/Estadisticas_Sociales/sitio_violencia/presentacion.pdf

- INEC. (2019). Encuesta Nacional Sobre Relaciones Familiares Y Violencia De Género Contra Las Mujeres (Envigmu) Boletín. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Estadisticas_Sociales/Violencia_de_genero_2019/Boletin_Tecnico_ENVIGMU.pdf

- INEC, N. I. of S. and C. (2019). Encuesta Nacional sobre Relaciones Familiares y Violencia de Género contra las Mujeres-ENVIGMU.

- Kabeer, N. (1998). Money Can’t Buy Me Love? Re-Evaluating Gender, Credit and Empowerment in Rural Bangladesh. Institute of Development Studies. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/13879

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125

- Kalmuss, D. S., & Straus, M. A. (1982). Wife’s marital dependency and wife abuse. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44(2), 277. https://doi.org/10.2307/351538

- Kilburn, K. N., Pettifor, A., Edwards, J. K., Selin, A., Twine, R., MacPhail, C., Wagner, R., Hughes, J. P., Wang, J., & Kahn, K. (2018). Conditional cash transfers and the reduction in partner violence for young women: An investigation of causal pathways using evidence from a randomized experiment in South Africa (HPTN 068). Journal of the International AIDS Society, 21(S1), e25043. https://doi.org/10.1002/JIA2.25043

- Koenig, M., Ahmed, S., & Haaga, J. (1999). Individual and Community-Level Determinants of Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh. https://dspace-prod.mse.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/969

- Levinson, D. (1989). Family Violence in Cross-Cultural Perspective. SAGE Publications Inc. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1989-97364-000

- Ley No 175 Ley Orgánica Integral para Prevenir y Erradicar la Violencia Contra las Mujeres. (2018). https://www.igualdad.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2018/05/ley_prevenir_y_erradicar_violencia_mujeres.pdf

- Malhotra, A., & Schuler, S. R. (2002). Measuring Women’s empowerment as a variable in international development.

- Medea, A., & Thompson, K. (1974). Against Rape. https://books.google.com.ec/books/about/Against_Rape.html?id=N_oDAQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y

- Moreira Cedeño, G. E., Salazar Ponce, E., & Loor Moreira, B. V. (2020). Políticas públicas en el ecuador: ¿tienen un impacto real en la violencia de género? UNESUM-Ciencias: Revista Científica Multidisciplinaria, ISSN 2602-8166 4(4), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.47230/UNESUM-CIENCIAS.V4.N4.2020.336

- Moreno, A. (2007). La primera infancia y la adolescencia (Vol. 8). UOC. http://openaccess.uoc.edu/webapps/o2/bitstream/10609/110987/7/LaadolescenciaCAST.pdf

- Mundosur. (2022). Mapa Latinoamericano de Feminicidios 2.0 | Tableau Public. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/mundosur/viz/MapaLatinoamericanodeFeminicidios2_0_16560990451280/Dashboard1

- O’neil, T., Domingo, P., & Valters, C. (2014). Progress on women’s Empowerment from Technical Fixes to Political Action. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9282.pdf

- Peterman, A., Bleck, J., & Palermo, T. (2015). Age and intimate partner violence: An analysis of global trends among women experiencing victimization in 30 developing countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(6), 624–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JADOHEALTH.2015.08.008

- Pinto, W. A. (2003). Historia del feminismo. Revista de La Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, (225), 30–45. https://www.revistauniversitaria.uady.mx/pdf/225/ru2254.pdf

- Rahman, M., Hoque, M. A., & Makinoda, S. (2011). Intimate partner violence against women: Is women empowerment a reducing factor? A study from a national Bangladeshi sample. Journal of Family Violence, 26(5), 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10896-011-9375-3

- Rennison, C. M. (2001). Intimate partner violence and Age of Victim, 1993-99. http://policeprostitutionandpolitics.com/pdfs_all/GOVERNMENTREPORTSUSJusticeDeptstatsSEEALSOTRAFFICKINGALL/RapeandSexualAbuseAdultsIncludingRapesinPrison/intimatepartnerviolencethrough1999.pdf

- Richardson, R. A. (2018). Measuring Women’s empowerment: A critical review of Current practices and recommendations for researchers. Social Indicators Research, 137(2), 539–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1622-4

- Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.629

- Russell, D. E. H. (1975). Politics of Rape: The Victim’s Perspective. Stein and Day. https://www.ojp.gov/library/abstracts/politics-rape-victims-perspective-0

- Russo, N. F., & Denious, J. E. (2001). Violence in the lives of women having abortions: Implications for practice and public policy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.32.2.142

- Russo, N. F., & Pirlott, A. (2006). Gender-Based Violence: Concepts, Methods, and Findings. https://do i.org/psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-00377-014

- Samari, G. (2017). First birth and the trajectory of women’s empowerment in Egypt. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1494-2

- Simon, B. L. (1994). The Empowerment Tradition in American Social Work: A History. Columbia University Press. http://cup.columbia.edu/book/the-empowerment-tradition-in-american-social-work/9780231074452

- SITEAL. (2019). Ecuador. https://siteal.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/sit_informe_pdfs/dpe_ecuador-_25_09_19.pdf

- Speizer, I. S., & Pearson, E. (2010). Association between early marriage and intimate partner violence in India: A focus on youth from Bihar and Rajasthan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(10), 1963–1981. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510372947

- Subsecretaría Prevención y Erradicación de la Violencia contra la Mujer. (n.d.) Servicio de Protección Integral.

- UN. (1996). United Nations report of the fourth world conference on women Beijing. September 4-15, 1995.

- UN. (2015). Objetivos y metas de desarrollo sostenible - Desarrollo Sostenible. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/objetivos-de-desarrollo-sostenible/

- UN WOMEN. (n.d.) World Conferences on Women.

- Vacacela Márquez, S., Mideros Mora, A., Vacacela Márquez, S., & Mideros Mora, A. (2022). Identificación de los factores de riesgo de violencia de género en el Ecuador como base para una propuesta preventiva. Desarrollo y Sociedad, 2022(91), 111–142. https://doi.org/10.13043/DYS.91.3

- Vara-Horna, A. (2013). Los costos invisibles de la violencia contra las mujeres para las microempresas ecuatorianas. 29. http://www.administracion.usmp.edu.pe/investigacion/files/Costos-empresariales-Ecuador-1.pdf?subid1=20230317-0251-0358-9b12-ecbf28b1b1ac

- Vara-Horna, A. (2020). The country costs of violence against women in Ecuador. https://www.facebook.com/MujeressinV/

- Wado, Y. D., Mutua, M. K., Mohiddin, A., Ijadunola, M. Y., Faye, C., Coll, C. V. N., Barros, A. J. D., & Kabiru, C. W. (2021). Intimate partner violence against adolescents and young women in sub-saharan Africa: Who is most vulnerable? Reproductive Health, 18(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01077-z

- WHO. (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women.

- Wooldridge, J. (2015). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. Cengage learning.

- World Bank. (2020). Población, mujeres - Ecuador | Data. https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.FE.IN?locations=EC

- The World Bank. (2020). World Development Indicators | The World Bank.

- Yapp, E., & Pickett, K. E. (2019). Greater income inequality is associated with higher rates of intimate partner violence in Latin America. Public Health, 175, 87–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PUHE.2019.07.004

- Yoshihama, M., & Horrocks, J. (2010). Risk of intimate partner violence: Role of childhood sexual abuse and sexual initiation in women in Japan. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2009.06.013