ABSTRACT

Visitor attitude is fundamental to destination selection in the tourism literature. Yet, there remains a notable dearth of critical reviews to assess the current status of knowledge on the topic. This study, therefore, seeks to map and critically evaluate the state of visitor attitudinal research to set the agenda for future scholarly enquiry. A review of journal articles on the topic in four leading tourism journals was undertaken. To critically explore the literature and identify research trends, a paradigm funnel approach was used. The findings demonstrate that most studies on the topic are based on empirical research and specific theories, most notably the contact model and theory of planned behaviour. However, few publications apply analytical methods and innovative ontological and epistemological approaches. This paper provides recommendations for future studies to advance visitor attitudinal research, advocating for the use of innovative methods and theoretical approaches in parent sub-disciplines, particularly psychology.

Introduction

This study intends to advance the understanding of visitor attitude by critically analysing prior research in this important area of tourism studies. Attitude is described as a learned propensity to evaluate an object with degrees of favourability or unfavourability (Hsu et al., Citation2010). Visitor attitude is identified as a key factor in destination choice (Ayeh et al., Citation2013) and, thus, attitudinal research focused on visitor markets (referred to henceforth as “visitor attitude”) has gained unprecedented attention from tourism scholars. Focusing on visitor attitude enables tourism managers to create promotional content designed explicitly to target the desired market segment (Dodd & Bigotte, Citation1997) or design products and actions that are coherent with visitors’ expectations (Andrades-Caldito et al., Citation2013).

Visitor attitude towards destinations is influenced by beliefs about the tourism destination (Lee & Lockshin, Citation2012). Destination marketers try to influence consumer beliefs through various channels such as slogans (Zhang et al., Citation2017), word of mouth (WOM), advertising (Loda et al., Citation2007) and even celebrity endorsement (e.g. Li et al., Citation2017; Tang et al., Citation2012; Van der Veen & Song, Citation2014; Yüksel & Akgül, Citation2007). The tourism literature has extensively focused on the pre – and post-trip attitudes of visitors (Sparks & Pan, Citation2009). Past visitations and destination familiarity can also influence attitude (Kim & Kwon, Citation2018). The attitude that visitors form while visiting a destination affects their satisfaction with the trip as a result of their memories of that place. Reflections on the travel can influence the intention to revisit (Huang & Hsu, Citation2009). Visitors’ post-trip attitude towards destinations can also influence their recommendation inclination (Bonn et al., Citation2007), which can also affect a destination’s visitor performance. Thus, understanding factors that impact consumer attitude is critical to tourism marketing and influences the overall performance of the destination.

Visitor attitude to tourism destinations is an established area of scholarly attention, playing a critical role in shaping destination choice, tourism marketing, service design, visitation intention, satisfaction, and recommendation inclination (Altunel & Erkurt, Citation2015; Ayeh et al., Citation2013). However, there remains a significant gap in the literature; a comprehensive review that critically analyses and synthesises the existing research in the area is noticeably absent. Periodic monitoring of scholarly content is critical to depict a thorough assessment of research progress in a field (Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2023), and to draw attention to the subfields that need further development (Xiao & Smith, Citation2006). Conducting a thorough review of visitor attitudes toward tourism destinations not only has the potential to consolidate the diverse body of knowledge on the topic but also to uncover underlying themes in the field, identify gaps that can guide future research directions, and formulate a strategic agenda designed to advance scholarly discourse.

This study aims to bridge the research gap by providing a comprehensive and critical review of prior studies on visitor attitude to tourism destinations. In doing so, this study introduces theories grounded in psychology and innovative research techniques to inform future studies of visitor attitude. Due to the descriptive nature of bibliometric analysis and its limited capacity to advance knowledge conceptually (Schultz et al., Citation2018), this study applies an innovative approach, specifically the paradigm funnel approach to develop a nuanced understanding of the complexities underpinning visitor attitudes. This approach advances the field from theoretical, ontological, epistemological and methodological perspectives (Lee & Scott, Citation2015).

The paradigm funnel approach provides a deeper level of analysis, assessing the progress of the existing research beyond conventional descriptive approaches (Lee & Scott, Citation2015). Unlike the common approach in most review studies in tourism which provide affiliations, journal rankings, and citations (e.g. Moyle et al., Citation2021), the paradigm funnel offers an in-depth analysis of literature through investigation and categorisation of dynamics of change in a field of research (Breazeale, Citation2009). Utilising the paradigm funnel, this research advances tourism knowledge by presenting a critical and comprehensive analysis of prior studies on visitor attitude to tourism destinations and providing avenues to direct future attempts to address the gaps in extant scholarship.

Literature review

With foundations deeply embedded in social psychology in a seminal work by Allport in 1935 (McLeod, Citation1991), visitor attitude is characterised as either a favourable or unfavourable perception of a destination (Al Muala, Citation2011). Attitude towards a destination is formed by a consumer’s positive and negative views or beliefs about that place, making it essential for travel decision-making (Ayeh et al., Citation2013). Fishbein (Citation1967), as one of the seminar scholars in attitudinal research, identified cognitive, affective and behavioural aspects as the components of attitude. The cognitive component is awareness, knowledge or beliefs about a destination, forming the basis of how attitudes are shaped (Jalilvand et al., Citation2012). The attitude formation can be influenced by previous visits or information from various marketing channels (Pike & Ryan, Citation2004). The affective component reflects an individual’s feelings towards a destination, which could be positive, negative or neutral (Back & Parks, Citation2003). Gartner (Citation1994) highlighted the significant role of visitors’ emotions in the destination selection process. The behavioural dimension relates to the likelihood of visiting a destination (Pike & Ryan, Citation2004). Researchers in tourism have extensively studied the factors that can influence these components of visitor attitude.

Research on attitude towards destinations has a long history in tourism literature (Jordan et al., Citation2018). This body of work typically falls into two distinct categories. The first category examines the outcomes of attitudinal judgments, such as their impact on travel planning and behavioural intentions, including the desire to visit or recommend a destination (Oh & Hsu, Citation2001). The second category focuses on the antecedents of attitude, investigating factors such as slogans associated with the destination and its familiarity (Zhang et al., Citation2017), the influence of WOM (Jalilvand et al., Citation2012), and the effects of destination advertising (Loda et al., Citation2007), among others.

Despite its significance in various stages of travel, there has been a lack of critical analysis of the status of knowledge on visitor attitude to tourism destinations. Subsequently, the current study applies Kuhn’s (Citation1996) paradigm funnel which offers substantial potential to address the descriptive limitation of bibliometric studies, by analysing the existing knowledge based on four levels including empirical research, analytical approaches, theoretical frameworks, and core assumptions. The paradigm funnel can provide a synopsis of the state of the literature on a topic; yet there is a dearth of research that has employed this technique (e.g. Confente, Citation2015; Lee & Scott, Citation2015; Liang et al., Citation2017). Using content analysis combined with the paradigm funnel approach, this review presents a systematic analysis of prior literature on visitor attitude to tourism destinations in the four leading tourism journals and classifies research trends in the field, beginning in 1977 when a seminal paper was published, up to 2020. Consistent with prior review articles, Tourism Management (TM), Journal of Travel Research (JTR), Journal of Sustainable Tourism (JOST), and Annals of Tourism Research (ATR) were selected due to their high Impact Factor (Ruhanen et al., Citation2015). This review is in line with calls to critically analyse the attitudinal knowledge in tourism (Gao et al., Citation2016; Wang, Citation2016).

Methods

This section outlines the methodology used for the study. This includes identifying the topic under investigation and determining the study’s timeframe, selecting target journals, and employing a three-stage approach to select and code relevant articles. Each stage and the corresponding details are presented below.

Publications on visitor attitudes and the research timeframe

This paper extends a previous research note that exclusively discussed the theoretical trends in visitor attitude literature (Please refer to reference removed for peer review). The recently updated database includes 171 papers on visitor attitude in TM, JTR, JOST, and ATR, covering publications up to 2023. The cutoff was set at 2023, which was the complete year at the time of data extraction (Moyle et al., Citation2022). The current review extends the research note by critically examining the existing literature through the four levels of Kuhn’s (Citation1996) paradigm model. The application of the paradigm funnel advances the research note by presenting deeper levels of investigation such as data collection and analysis methods, ontological, epistemological and methodological approaches, topical and geographical clusters in addition to the identification of theoretical frameworks.

Target journals

The selection process for the inclusion of papers on visitor attitude to tourism destinations focused on TM, JTR, JOST, and ATR. These four journals, individually or in combination, have been ranked as the leading outlets in tourism research (Ruhanen et al., Citation2015). The four leading journals have the highest quality and Impact Factor in tourism scholarship (Moyle et al., Citation2022). In addition, at the time of the research, these four journals are the only A* outlets, according to the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) Journal Quality List. The ABDC ranking is commonly applied internationally for benchmarking purposes and the adoption of quality metrics (Hall, Citation2011; Spasojevic et al., Citation2018). In addition, these are the highest-ranked journals in tourism according to the Scimago Journal and Country Rank (Soliman et al., Citation2021). The authors acknowledge the subjective nature of journal rankings and the occasional high ranking of other journals (Frechtling, Citation2004). However, the choice of these four leading journals as a sample for this study was deemed appropriate and is considered best practice, especially when assessing a broad topic across an expansive timeframe and evaluating the “state of play” regarding research trends (McKercher, Citation2005; Moyle et al., Citation2022; Mura et al., Citation2017; Nunkoo et al., Citation2013; Ryan, Citation2005). In addition, this approach is commonly used in prior literature review articles (e.g. Baum et al., Citation2016; Hunt et al., Citation2014).

A three-stage approach to select and code relevant articles

Three stages were utilised to search keywords in target journals, identify and review relevant journal articles, and code the papers using the paradigm funnel and content analysis. The description of each stage is presented below.

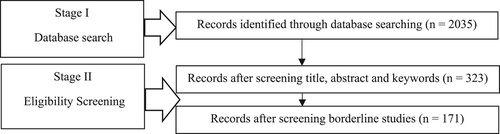

Stage One – Database search. Articles on visitor attitude to tourism destinations were identified and collated using “tourist or traveller or visitor” and “attitude or perception” as the search terms. The search process excluded non-journal publications like research notes, commentaries and book reviews (as per Yang et al., Citation2020). As a result, 2035 articles were retained in the initial stage of paper identification.

Stage Two – Eligibility screening. Papers in the dataset were screened for eligibility in this stage. Specifically, articles with an explicit focus on visitor attitude toward a particular destination were retained. Two of the researchers reviewed the title, abstract and keywords of the articles to detect if the paper explicitly investigated visitor attitude to a destination. Accordingly, 1712 papers were eliminated and thus 323 articles were identified as relevant. The reason for eliminating papers was an inability to identify the destination in the paper or an emphasis on visitor attitude to the local community or stakeholders of a place, not the destination itself (e.g. Berdychevsky et al., Citation2016; Simpson et al., Citation2016; Walker et al., Citation2013). In this stage, manuscripts that were borderline were checked by another research member to determine the eligibility of the paper to be included in the database. The eligible papers in this stage were cross-checked within the team and an agreement was reached. The main reason for eliminating the papers at this stage was manuscripts did not explicitly focus on visitor attitude towards a place, rather they explored other related subjects such as visitor attitude to the quality of tourism services or events (Jurado et al., Citation2013; Kee-Fu & Ap, Citation2007). Additionally, there has been a surge in attitudinal studies due to the COVID-19 pandemic across TM, JTR, JOST, and ATR, as well as in other journals (e.g. Fan et al., Citation2023; Tsironis et al., Citation2022). However, the primary focus of the publications in the four journals was not on visitor attitude to specific destinations, but rather on sustainable tourism (e.g. Chamarro et al., Citation2023) and crowding (Park et al., Citation2021) among others. This led to the further elimination of 152 articles, with 171 articles deemed relevant to be included in the final database. The process of selection of publications on visitor attitude is presented in .

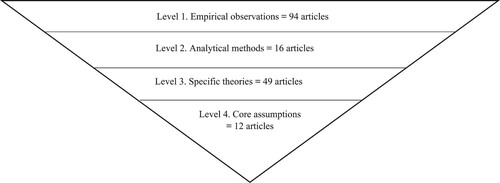

Stage Three – Coding articles using the paradigm funnel and content analysis. In this stage, articles were coded based on the paradigm funnel approach. This analysis approach categorises literature into four levels that reflect the primary purpose of the study (Lee & Scott, Citation2015). Drawing on prior review articles which have applied a paradigm funnel approach (e.g. Confente, Citation2015; Lee & Scott, Citation2015; Liang et al., Citation2017), each of the 171 articles were assigned to one level of the funnel.

Figure 1. Paper selection process in the current study.

Level one contains studies with empirical observations, that is, studies that are predominantly descriptive and based on primary or secondary data (Liang et al., Citation2017). Primary data denotes the information used in the research that was originally obtained by the researcher via questionnaires, interviews, focus groups or observation (Bernard et al., Citation1986). Secondary data refers to the information that is obtained by someone other than the researcher for a different purpose than its use in the study (Ellram & Tate, Citation2016) such as government reports as well as online data available on blogs (Boslaugh, Citation2007; von Benzon, Citation2019). Papers that utilised quantitative or qualitative methods were assigned to level one denoting that articles were atheoretical but used primary or secondary types of data. Level two of the funnel contains studies with analytical methods that selected or combined various methodologies to answer the research questions. This level includes papers based on a mix of quantitative and qualitative approaches to explore the topic (Confente, Citation2015). Publications that used or combined different methods were allocated to the second level of the funnel.

The third level relates to applying and validating a theory or a conceptual framework (Lee & Scott, Citation2015). Papers that dealt with the utilisation, implementing and validating of a theoretical framework, regardless of the data collection method, were assigned to the third level of the funnel. Level four constitutes papers with analysis based on deep assumptions, that is, the ontology, epistemology and methodology-informed publications which attempt to use or generate an innovative method or theory (Confente, Citation2015; Liang et al., Citation2017). Research articles that generated or utilised innovative conceptual or methodological approaches to the study of visitor attitude were classified at this level.

In addition to the identification of papers based on the level of the paradigm funnel, this research recorded the data collection and analysis types, topic clusters and geographical setting of the articles using quantitative content analysis, consistent with previous approaches used to analyse tourism literature (e.g. Choi et al., Citation2007; Fennell, Citation2001; Malloy & Fennell, Citation1998). The results from applying the paradigm funnel and content analysis to the database are presented in the following section.

Results

Results are presented below in five sections. The first part of the results presents the articles over the years in each publication outlet. Following this, articles assigned to each level of the funnel are organised. The first level of the funnel discusses papers that utilised qualitative and quantitative data collection approaches. The third section of the results deals with mixed-method articles to study visitor attitude. Level three of the funnel consists of papers on visitor attitude applying or validating a theory. In this section, the common theoretical frameworks employed in the field are also discussed. The last section includes articles that made novel use of ontological, epistemological, and methodological approaches. A table including information at each level of the funnel and research trends is presented at the end of the result section.

Overview of publications across the four journals

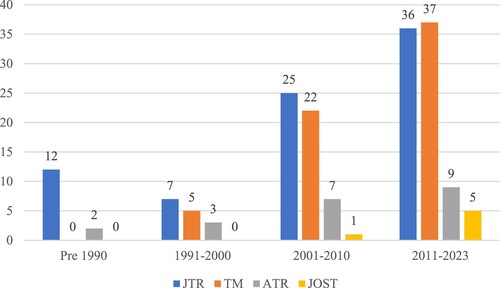

The search revealed that the study covers a timeframe of 47 years, from 1977 to 2023 since the first publication on the topic in the target journals belongs to Goodrich (Citation1977). The authors acknowledge work on visitor attitudinal research in journals outside the parameters of the search (e.g. Quintal et al., Citation2019; Riscinto-Kozub & Childs, Citation2012), which includes articles that precede Goodrich (Citation1977) such as the seminal work by MacCannell (Citation1973) on visitor attitude and authenticity. Cross-tabulation was applied to identify the number of publications in each journal. Similar to other reviews (e.g. Nunkoo et al., Citation2013), the analysis was split into four periods: pre-1990, 1991–2000, 2001–2010, and 2011–2023. Overall, the number of contributions to studies on visitor attitude has increased over this period, with 171 articles on visitors’ attitudes published in this timeframe. JTR and TM are the key outlets for these publications ().

Figure 2. Publications across time (N = 171).

presents the paradigm funnel approach applied to the comprehensive review of literature on visitor attitudinal studies. As presented in the figure below, 94 articles (55% of total publications) are in the largest part of the funnel, i.e. empirical observations, indicating a potential overemphasis on descriptive research within the field. The second level, analytical methods, includes a notably smaller number of publications, only 16. Level three – specific theories – comprises 49 articles on visitor attitude, suggesting a moderate engagement with theoretical frameworks. Notably, only 12 articles were assigned to the fourth level, highlighting a substantial gap in foundational research that challenges or builds upon the underlying assumptions of visitor attitudinal studies. This distribution highlights the limited analytical depth, the need for engagement with established theories, and a notable scarcity of foundational research critical for understanding the underlying assumptions behind visitor attitudes.

Level one: empirical research

Of the 94 manuscripts at the top of the funnel, 89 articles were based on primary data using interviews, surveys, and focus groups, suggesting a potential over-reliance on self-reported data. In contrast, only five empirical research articles utilised secondary data such as web content or destination annual surveys of visitors, indicating a possible under-utilisation of available broader datasets that might offer different insights. Quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods appear at this level with a preference to employ quantitative methods (n = 82), potentially overshadowing richer, in-depth qualitative insights (n = 3) and the nuanced understanding afforded by mixed methods approaches (n = 9), which together constitute merely a tenth of the empirical research. Statistical techniques commonly used include confirmatory factor analysis (e.g. Bonn et al., Citation2005), cluster analysis (e.g. Weaver & Lawton, Citation2004), t-tests (e.g. Pizam et al., Citation2002), ANOVA (analysis of variance) (Vogt & Andereck, Citation2003), MANOVA (multivariate analysis of variance) (e.g. Lee & Lockshin, Citation2012), regression analysis (e.g. Sönmez & Sirakaya, Citation2002), importance-performance analysis (e.g. Pike & Ryan, Citation2004) and structural equation modelling (e.g. Choi et al., Citation2018) to assess visitor attitude. This focus indicates a conventional adherence to established analytical norms, which could limit innovative approaches in understanding visitor attitudes.

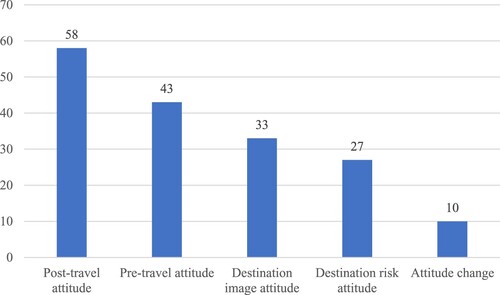

Based on the primary focus of the papers in this first level of the funnel, five topical clusters were identified including post-travel attitudes (n = 40), destination image perceptions (n = 19), potential visitors’ attitudes (n = 19), destination risk/safety perceptions (n = 12) and attitude change (n = 4), revealing a strong emphasis on post-travel attitudes and less on transformative aspects like attitude change. In terms of the country of investigation, there was nearly an equal number of publications on measuring visitor attitude to Asia (n = 24), Europe (n = 23), and America (n = 23). Whereas the Middle East (n = 14), Oceania (n = 8) and Africa (n = 8) received less attention from tourism scholars, highlighting a geographical bias that may skew the global applicability of research findings.

Level two: analytical methods

In the analytical method level of the funnel, there were 16 articles (9.3% of the total number of articles) that predominantly focused on a mix of qualitative and quantitative approaches to investigate visitor attitude to tourism destinations. Prior research tends to apply mixed method approaches where a quantitative approach was followed by qualitative (e.g. Butler & Richardson, Citation2015; Poria et al., Citation2011) or vice versa (e.g. Reddy et al., Citation2012; Rittichainuwat & Chakraborty, Citation2009). The majority of analytical method articles (n = 12) explored visitor attitude based on primary data using interviews, focus groups and surveys with only four manuscripts utilising secondary data such as travel blog content. The over-reliance on primary data might limit the scope of research findings, potentially omitting insights that could be gained from existing large datasets and secondary resources.

In this level of the funnel, 10 journal articles applied various quantitative methods. Also, six manuscripts employed mixed-method approaches to analyse data at this level of the funnel. Similar to level one, a range of statistical techniques are applied such as descriptive analysis (e.g. Poria et al., Citation2009), t-tests (e.g. Poria et al., Citation2011), ANOVA/MANOVA (e.g. Fuchs et al., Citation2013), cloud analysis (e.g. Sun et al., Citation2015), and structural equation modelling (e.g. Rittichainuwat & Chakraborty, Citation2009) to explore visitor attitude to tourism destinations. This reflects a continued preference for conventional statistical techniques that could indicate a conservative approach to data analysis that may not fully capture the complexities of visitor attitudes. Four topical clusters are identified at this level of the funnel with six manuscripts on potential visitors’ attitudes, six publications focused on destination image perceptions, two papers on destination risk/safety perceptions, and two articles studying post-travel attitude, reflecting a notable lack of exploration into attitude change. Scholars investigated visitor attitude towards Asia (n = 5), the Middle East (n = 3), America (n = 2), Europe (n = 1), Oceania (n = 1), Africa (n = 1) and Space (n = 1) at this level. This reveals a disparity in focus and highlights geographical skewness, which could perpetuate a narrow understanding of global visitor attitudes and thus limits the applicability of findings across diverse cultural and spatial contexts.

Level three: specific theories

Engagement with theoretical frameworks demonstrates the maturity of a subfield of knowledge (Hadinejad et al., Citation2021). There are 49 articles (28.6%) on visitor attitude to tourism destinations located in the third level of the funnel which dealt with theory-related processes or applied a theoretical framework. Results indicate that the theory of planned behaviour (n = 7) and contact model (n = 6) are the frequent theoretical frameworks utilised in prior research. The predominant reliance on these frameworks suggests a potential stagnation in theoretical innovation in the field. Furthermore, protection motivation theory, the elaboration likelihood model, emotional solidarity and consumer-based brand equity were applied on multiple occasions. The majority of articles at this level utilised primary data via survey and interview (98%), indicating a lack of diversity in data collection methods. A total of 47 publications analysed data using a quantitative method, with only two manuscripts applying a mixed approach, pointing to a possible lack of richer, more nuanced qualitative analyses. Descriptive statistics (e.g. Huang & Hsu, Citation2009), t-tests (e.g. Kim & Lehto, Citation2013), ANOVA (e.g. Stepchenkova & Shichkova, Citation2017), and PLS-MGA (partial least squares multigroup analysis) (e.g. Simpson & Simpson, Citation2017) are some of the statistical techniques applied in the articles in this level, suggesting more advanced analytical methods to explore the complexities of visitor attitudes. Scholars mainly studied potential visitors’ attitudes (n = 15), destination risk/safety perceptions (n = 12), post-travel attitudes (n = 9), destination image perceptions (n = 7), and attitude change (n = 6) in level three of the paradigm funnel. The limited exploration of attitude change suggests a critical gap in understanding how visitor perceptions evolve, which is crucial for developing effective tourism strategies. In the specific theory level of the paradigm funnel, 17 articles explored visitor attitude towards Asian countries. Furthermore, visitor attitude to America (n = 11), Europe (n = 7), Oceania (n = 7), the Middle East (n = 5), and Africa (n = 2) were studied, indicating a geographical imbalance that may contribute to a narrow understanding of visitor attitudes and limit the generalisability of research findings across diverse global contexts.

Level four: core assumptions

Papers in this level of the paradigm funnel focus on innovative conceptual or methodological issues. There are 12 articles at this level representing only 7.1% of the total pool of manuscripts on visitor attitude to tourism destinations, highlighting a significant underrepresentation of groundbreaking work. Davis and Sternquist (Citation1987) developed a technique to classify tourist-attracting features for market segmentation. Hsu et al. (Citation2010) proposed the expectation, motivation, and attitude (EMA) model in their study. Boley et al. (Citation2011) presented a scale for the measurement of geotraveller tendencies. Naoi et al. (Citation2011) introduced the caption evaluation method which was employed to explore visitors’ perceptions of historical attractions. A new scale, tourists’ perceived tourist – host identity risk (THIR), has been developed to measure risk perception (Fong et al., Citation2023). Also, Ye and colleagues (Citation2020) introduced a new best – worst scaling to measure destination values. These examples provide evidence, albeit limited, of methodological innovations in the tourism field.

In this level of the funnel, 10 publications utilised primary data including surveys, focus groups and visual methods while the two remaining manuscripts explored visitor attitude based on user-generated content and tourism board information, underscoring a continued preference for traditional data collection and analysis techniques over novel approaches. All the publications employed a quantitative data analysis technique to analyse data, indicating a tendency to test a theory. Similar to other levels of the funnel, some common statistical techniques such as descriptive analysis (e.g. Shih, Citation1986), structural equation modelling (e.g. Prebensen et al., Citation2013), cluster analysis (e.g. Davis & Sternquist, Citation1987), and regression analysis (e.g. Manosuthi et al., Citation2020) were utilised. The topical clusters in this level include post-travel attitude (n = 7), potential visitor attitude (n = 3), destination image perception (n = 1), and destination risk/safety perceptions (n = 1), reflecting a narrow scope that fails to comprehensively address under-researched areas such as destination image, risk perceptions, and attitude change. Destinations in Asia (n = 4), Europe (n = 3), America (n = 3), and Oceania (n = 1) were investigated at this level, presenting lesser attention to the Middle East and Africa which could limit broader geographical explorations and comprehensive understanding in tourism research. The levels of the paradigm funnel with a descriptive analysis of the research trends are illustrated in .

Table 1. Levels of the paradigm funnel and research trends in each level (N = 171).

Discussion

This research reveals substantial growth in the scholarly inquiry on visitor attitude to tourism destinations in TM, JTR, JOST, and ATR across 47 years. Application of the paradigm funnel approach revealed the majority of studies on visitor attitude are based on primary data. This research also shows that less than one-third of the studies utilised specific conceptual frameworks and theories to investigate visitor attitude. On the other hand, there is scant evidence of exploring visitor attitude via mixed methods or novel research techniques such as innovative ontology, epistemology, and methodology-related approaches. The results of the paradigm funnel and content analysis are now utilised to articulate research patterns and trends, and present directions for further investigation of visitor attitudinal research, as detailed below.

Methodological directions

The finding that the majority of studies are empirical observations with a preference for primary data implies that further investigation on visitor attitude using innovative selection, or a combination of ontological, epistemological and methodological approaches has the potential to advance the knowledge in the area. For example, future scholarly inquiry will benefit from examining visitor attitude to tourism destinations, or conceptually related areas, using secondary data that applies machine learning. Tourism consumer research has changed extensively with advanced methods such as machine learning analysing abundant heterogeneous and complex data (Le et al., Citation2021). Therefore, future researchers have an opportunity to use machine learning to analyse large amounts of sophisticated data consumers share on online platforms such as travel blogs.

With a dominance of the positivist approach in existing research, tourism scholars need to employ qualitative and mixed methods more frequently to provide in-depth insights into visitor attitude and understand why visitors form particular attitudes towards tourism destinations. Although there is a tried and tested range of qualitative approaches such as interviews, focus groups, content analysis and social media analysis, more novel techniques present an opportunity to advance the discourse. Future scholars, therefore, can benefit from innovative approaches to study attitude in psychology like the appreciative inquiry process (e.g. Koster & Lemelin, Citation2009) and the Q method (e.g. Hunter, Citation2011). The Q method (a systematic study of beliefs) can be utilised to explore the opinions and attitudes of visitors towards different tourism destinations (Hunter, Citation2011). In addition, in response to the call for further investigation of attitude change (Pike & Ryan, Citation2004), future scholarly inquiry should consider leveraging advances in the Q method to analyse visitors’ attitude prior to travel and after they visit a destination. Researchers should also consider the appreciative inquiry process, a participatory research method that understands individuals’ attitudes, needs and priorities regarding a destination (Nyaupane & Poudel, Citation2011). This approach involves action research that uses a cooperative inquiry method in which both researcher and subject work together collaboratively. The appreciative inquiry process seems especially suitable for developing countries, especially in rural contexts in which the rate of literacy is low as the method does not require the participants to read surveys.

Another implication of the dominance of empirical research on visitor attitude is a lack of analytical articles. Future research could be enhanced by applying pragmatic approaches (Teddlie & Tashakkori, Citation2003) to push the literature beyond the current dominance of reductionist methods, for example by applying ethnography combined with existing self-report measures. Given the criticisms around neglecting the affective aspects of attitude formation (e.g. Esfandiar et al., Citation2019), there is potential for future tourism scholars to build on existing cutting-edge technologies like facial expression analysis or electro-dermal analysis (Hadinejad et al., Citation2019a) coupled with self-report surveys to provide an in-depth understating of visitor attitude and the role of emotions in explaining them. With a preference for primary data in the existing studies and limited secondary data, tourism scholars can contribute to visitor attitudinal literature by employing user-generated content, big data, and tourism board information along with qualitative approaches to provide the field with more analytical maturity. summarises the existing methods in visitor attitude literature and potential approaches for future scholarship.

Table 2. Existing methods in visitor attitude literature and potential approaches for future scholarship.

Theoretical directions

The dominance of empirical research implies that existing visitor attitudinal scholarly enquiry is mainly descriptive, and a lack of theoretical engagement dominates the field. This review recognises theoretical frameworks like the theory of planned behaviour and contact model applied commonly in the field. These two theoretical frameworks were mainly used in early publications. Although the theory of planned behaviour is a common framework for assessing the correlation between attitude and intentions (Chao, Citation2012), this conceptual framework has been criticised for neglecting affective and metacognitive aspects in attitude formation (Bagozzi et al., Citation2002; Esfandiar et al., Citation2019; Hadinejad et al., Citation2022). The results of this study add further weight to tourism scholars’ calls recommending the use of other theories (e.g. Gao et al., Citation2016; Weiler et al., Citation2018), especially from parent disciplines, most notably psychology, to advance visitor attitudinal research.

Notwithstanding, there is some evidence that tourism researchers have attempted to apply emerging theories such as the protection motivation theory (e.g. Wang et al., Citation2019), emotional solidarity (e.g. Simpson & Simpson, Citation2017), consumer-based brand equity (e.g. Bianchi et al., Citation2014), complexity theory (e.g. Han et al., Citation2019), and inoculation theory (Ivanov et al., Citation2018). However, researchers need to further assess the efficacy of contemporary theoretical frameworks in parent disciplines to explore how such theories can be applied in tourism attitudinal research. Applying emerging theories from parent disciplines provides conceptual potency which would enable tourism scholars to overcome mounting criticism directed at current theoretical frameworks and their failure to incorporate the role of emotion in attitude formation (Hadinejad et al., Citation2021).

For example, scholars can utilise frameworks such as the cognitive response theory and heuristic systematic model to address the criticism against the inability of existing theories to incorporate cognitive and affective aspects in attitude formation. Cognitive response theory highlights the direction of thoughts (positive versus negative) in attitudes while the heuristic systematic model focuses on the processing of information in attitude formation (Hadinejad et al., Citation2022). In addition, future research can further expand the field by investigating metacognition through applying the self-validation hypothesis (Petty et al., Citation2002). The investigation of the role of thought confidence (i.e. how confident you are in your thinking about a tourism destination), as the core tenet of the self-validation hypothesis in visitor attitude formation, might overcome the lack of existing research on core assumptions. In addition, a promising approach to understanding the mechanisms of attitude formation and evaluating the affective aspects of attitudinal judgments is the use of cognitive appraisal theory (Skavronskaya et al., Citation2017). Cognitive appraisal theory that emphasises the elicitation of emotions based on evaluations of an external stimulus has been utilised in prior tourism research (e.g. Hosany, Citation2012; Ma et al., Citation2013). However, the investigation of the emotive aspect of attitude as per this theoretical framework is in its infancy.

Topical and geographical directions

This review shows post-travel attitudes, potential visitors’ attitudes, destination image perceptions, risk/safety perceptions, and attitude change as the main concepts applied in the visitor attitude literature. The topical clusters are illustrated in . Post-travel and potential visitor attitude towards tourism destinations seem to be over-represented in existing studies, implying further research is required with an explicit focus on other concepts such as attitude change. Connected to this, the current review indicates that attitude change is under-represented in tourism literature with only ten studies on this concept. The apparent lack of research on attitude change in the top four tourism journals is also indicated in previous studies (e.g. Li & Wang, Citation2020), with scholars calling for longitudinal studies to explore this topic. Social psychologists mainly focus on attitude change as a potential way to impact individuals’ behaviour (Petty et al., Citation2002) rather than studying attitude per se. Employing such approaches from social psychology has the potential to contribute to the field and practice by unearthing the mechanisms that induce attitude change in visitors with a flow-on effect to actions.

Figure 4. Topical clusters in the current study.

While visitor attitude was used as a key search term to identify articles on individuals’ assessment of a destination, there were publications that confused this concept with other constructs such as image and perception (of risk) (e.g. Durko & Petrick, Citation2016; Stepchenkova & Shichkova, Citation2017). Such publications confused evaluations of the place with image or perception yet were concerned with both concepts and thus were retained in the database. Future tourism scholars need to be cautious while using each term according to the purpose of their research and not use such concepts interchangeably. While image refers to the mental representation of an object, attitude is about an individual’s evaluation of issues. In addition, scholars have utilised attitudes and perceptions interchangeably such as attitudes towards the safety of a destination or perceptions of risk of a place, resulting in conceptual ambiguity.

Further studies are recommended to explore the linkage between emerging concepts in parent disciplines with visitor attitude to add value to the fourth level of the paradigm funnel which currently includes limited publications. For instance, exploring the role of embodied experience – experiencing and understanding the world through bodily senses (Lu et al., Citation2020) – in developing attitudes in individuals with vision impairment towards a specific destination could contribute to the core assumptions. Such studies can advance the field of tourist experience beyond the current ocular-centric streams. Applying innovative ontological approaches such as embodiment ontology, i.e. construction of the body in a social space (Small et al., Citation2012), and the multisensory approach, i.e. the various senses and their holistic perception influence on the experience (Agapito, Citation2020), might better explain the impact of socially constructed tourism experiences on visitor attitude. The assessment of the influence of reconsolidated memory, a transformed version of the original memory (Braun-LaTour & LaTour, Citation2005), on visitor attitude is another example that could contribute to the core assumption discourse.

In addition, multidisciplinary research that integrates visitor attitude studies with contemporary constructs from parent disciplines holds the potential for groundbreaking research, contributing to the fourth level of the paradigm funnel. Considering the significant impact of gender issues on shaping travel experiences, attitudes towards safety, and inclusivity (Huang & van der Veen, Citation2019), it is crucial to further explore how aspects such as women’s empowerment influence visitor attitudes before and after their visit. Moreover, the political status of destinations and governance structures play crucial roles in shaping attitudinal judgements (Sharifpour et al., Citation2014), making it essential to understand their impact on visitor attitudes and destination choices to inform tourism strategies for destination management. Additionally, marginalised groups such as LGBTIQ + have been largely overlooked in tourism studies (Ong et al., Citation2023). Research into how these groups perceive host destination inclusivity practices, and its effects on their attitudes and behaviours, could significantly advance the understanding in this area.

The findings of this research present that countries in America and Asia are the dominant destinations of investigation. These findings echo existing reviews of the literature on residents’ attitudes, as countries in these two continents were also the most studied destinations (e.g. Hadinejad et al., Citation2019b). Tourism destinations in the Middle East, Oceania, and Africa have received the least attention from scholars to investigate visitor attitude. There is an opportunity to analyse visitor attitude towards less studied regions to deepen contextual understandings of such countries and hence provide destination managers with practical implications to create appropriate marketing stimuli. A potential future contribution could be a longitudinal study on visitors travelling to less visited countries to explore their attitude change (Li & Wang, Citation2020). Due to the political instability and recent safety-related issues in the Middle East, such as in Turkey (Kutlay, Citation2019), researchers can examine the effect of terrorism on potential or repeated visitors’ attitudes toward this country. Another recommendation to consider would be a focus on visitor attitude to African countries which are affluent with natural resources (Witbooi et al., Citation2011) and thus can attract environmental and adventure tourists. Tourism researchers can study visitor attitude towards Africa before and after their trip to this region to understand their attitudes and identify areas for improvement in destination management. An explicit focus on the under-represented destinations in future research has significant implications as tourism practitioners are concerned about how to improve tourism and address issues, specifically those raised by the target market.

Conclusion, contribution and limitations

This manuscript provides a comprehensive assessment of over 47 years of research in tourism on visitor attitude towards destinations. This review reveals that studies on visitor attitude predominantly use primary data presenting opportunities for further scholarship using secondary data such as user-generated content on social media and tourism board information using machine learning methods. Quantitative methods dominate the field implying future research can use innovative qualitative approaches including the Q method or the appreciative inquiry process to advance the field methodologically. There is insufficient research on visitor attitude using mixed methods which implies the potential for utilising pragmatic approaches such as physiological technologies combined with surveys and interviews in future scholarly inquiry.

Another key finding of this research is that less than one-third of the studies used or validated a theory that demonstrates the descriptive nature of the literature on the topic. Future research can benefit from progress in parent disciplines like psychology to expand the diversity of theoretical frameworks used in visitor attitude research. Theoretical alternatives to consider include but are not limited to cognitive theories like the cognitive response theory, cognitive appraisal theory, and heuristic systematic model as well as metacognitive perspectives such as the self-validation hypothesis. The current literature on visitor attitude heavily focuses on post-travel attitude which suggests further scholarly inquiry is required to address less-studied topics such as attitude change. The existing knowledge on visitor attitude has largely explored the concept in the American and Asian context denoting further research is needed in countries in the Middle East, Oceania, and Africa. The application of innovative ontological, epistemological, or methodological approaches is limited in the field which showcases the need for further research applying emerging conceptual or methodological issues in parent disciplines.

This study makes several contributions to tourism research and offers practical implications for destination management. This research advances tourism scholarship by the application of the paradigm funnel through a critical assessment of research trends and patterns in visitor attitude, rarely obtained through bibliometric approaches. The in-depth analysis of visitor attitudinal studies through the paradigm funnel facilitated the evaluation of the progressions of the field from theoretical, ontological, epistemological and methodological perspectives, which advances the field beyond basic metrics. This review adds to tourism knowledge by illustrating the over-reliance on conventional self-reported measures and presenting alternatives for further research. Another contribution of this study is the illustration of theoretical disengagement in the field and proposing new theoretical frameworks from psychology for future scholarship. This review also extends tourism studies by providing topical and geographical directions that addresses existing gaps, aiming for a more geographically balanced and globally diverse understanding of visitor attitudes.

This study provides practical insights for tourism destination managers and marketers. Destination managers are encouraged to utilise secondary data, including user-generated content, social media analytics, and tourism board information, to gain a deeper understanding of visitor attitudes, expectations, and experiences. This understanding can help develop more targeted and effective marketing strategies. Consequently, implementing practices to measure changes in visitors’ attitudes could assess the effectiveness of these strategies. In addition, destination managers can use innovative qualitative methods to gain insights into the experiential aspects of tourists’ visits so they can offer services that resonate more deeply with tourists’ needs, train staff better and improve service touchpoints throughout the destination and inform broader strategic planning processes. The findings are particularly crucial for destinations in Africa and Oceania, where the visitor economy plays a significant role, yet visitor attitudes have not been extensively explored. This oversight could lead to a mismatch between tourist expectations and the services offered, highlighting the importance of this research.

The identification of publications was completed in JTR, ATR, TM, and JOST. Although this approach is common when reviewing a broad topic such as visitor attitude, it is recommended to replicate the study in other journals to detect additional theoretical and methodological approaches. Future studies also need to make a comparison between tourism and other disciplines like anthropology and sociology to further identify gaps in the application of theories of attitude.

APJTR_Author_Bio_clean.docx

Download MS Word (21.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Agapito, D. (2020). The senses in tourism design: A bibliometric review. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102934

- Al Muala, A. M. (2011). Antecedents of actual visit behavior amongst INTERNATIONAL tourists in Jordan: Structural equation modeling (SEM). Approach. American Academic & Scholarly Research Journal, 1(1), 35–42.

- Altunel, M. C., & Erkurt, B. (2015). Cultural tourism in Istanbul: The mediation effect of tourist experience and satisfaction on the relationship between involvement and recommendation intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(4), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.06.003

- Andrades-Caldito, L., Sánchez-Rivero, M., & Pulido-Fernández, J. I. (2013). Differentiating competitiveness through tourism image assessment: An application to Andalusia (Spain). Journal of Travel Research, 52(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512451135

- Ayeh, J. K., Au, N., & Law, R. (2013). “Do we believe in tripadvisor?” Examining credibility perceptions and online travelers’ attitude toward using user-generated content. Journal of Travel Research, 52(4), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512475217

- Back, K. J., & Parks, S. C. (2003). A brand loyalty model involving cognitive, affective, and conative brand loyalty and customer satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 27(4), 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480030274003

- Bagozzi, R., Gurhan-Canli, Z., & Priester, J. (2002). The social psychology of consumer behaviour. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Baum, T., Kralj, A., Robinson, R. N., & Solnet, D. J. (2016). Tourism workforce research: A review, taxonomy and agenda. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.04.003

- Berdychevsky, L., Gibson, H. J., & Bell, H. L. (2016). “Girlfriend getaway” as a contested term: Discourse analysis. Tourism Management, 55, 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.02.001

- Bernard, H. R., Pelto, P. J., Werner, O., Boster, J., Romney, A. K., Johnson, A., … Kasakoff, A. (1986). The construction of primary data in cultural anthropology. Current Anthropology, 27(4), 382–396. https://doi.org/10.1086/203456

- Bianchi, C., Pike, S., & Lings, I. (2014). Investigating attitudes towards three South American destinations in an emerging long haul market using a model of consumer-based brand equity (CBBE). Tourism Management, 42, 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.11.014

- Boley, B. B., Nickerson, N. P., & Bosak, K. (2011). Measuring geotourism: Developing and testing the geotraveler tendency scale (GTS). Journal of Travel Research, 50(5), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510382295

- Bonn, M. A., Joseph-Mathews, S. M., Dai, M., Hayes, S., & Cave, J. (2007). Heritage/cultural attraction atmospherics: Creating the right environment for the heritage/cultural visitor. Journal of Travel Research, 45(3), 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287506295947

- Bonn, M. A., Joseph, S. M., & Dai, M. (2005). International versus domestic visitors: An examination of destination image perceptions. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 294–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504272033

- Boslaugh, S. (2007). Secondary data sources for public health: A practical guide. Cambridge University Press.

- Braun-LaTour, K. A., & LaTour, M. S. (2005). Transforming consumer experience: When timing matters. Journal of Advertising, 34(3), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2005.10639204

- Breazeale, M. (2009). Word of mouse – An assessment of electronic word-of-mouth research. International Journal of Market Research, 51(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078530905100307

- Butler, G., & Richardson, S. (2015). Barriers to visiting South Africa's national parks in the post-apartheid era: Black South African perspectives from Soweto. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(1), 146–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.940045

- Chamarro, A., Cobo-Benita, J., & Herrero Amo, M. D. (2023). Towards sustainable tourism development in a mature destination: Measuring multi-group invariance between residents and visitors’ attitudes with high use of accommodation-sharing platforms. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 520–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1870988

- Chao, Y.-L. (2012). Predicting people’s environmental behaviour: Theory of planned behaviour and model of responsible environmental behaviour. Environmental Education Research, 18(4), 437–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.634970

- Choi, M., Law, R., & Heo, C. Y. (2018). An investigation of the perceived value of shopping tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 57(7), 962–980. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517726170

- Choi, S., Lehto, X. Y., & Morrison, A. M. (2007). Destination image representation on the web: Content analysis of Macau travel related websites. Tourism Management, 28(1), 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.03.002

- Confente, I. (2015). Twenty-five years of word-of-mouth studies: A critical review of tourism research. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(6), 613–624. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2029

- Davis, B. D., & Sternquist, B. (1987). Appealing to the elusive tourist: An attribute cluster strategy. Journal of Travel Research, 25(4), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728758702500405

- Dodd, T., & Bigotte, V. (1997). Perceptual dififerences among visitor groups to wineries. Journal of Travel Research, 35(3), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759703500307

- Durko, A., & Petrick, J. (2016). The Nutella project: An education initiative to suggest tourism as a means to peace between the United States and Afghanistan. Journal of Travel Research, 55(8), 1081–1093. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515617300

- Ellram, L. M., & Tate, W. L. (2016). The use of secondary data in purchasing and supply management (P/SM) research. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 22(4), 250–254.

- Esfandiar, K., Pearce, J., & Dowling, R. (2019). Personal norms and pro-environmental binning behaviour of visitors in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–15.

- Fan, X., Lu, J., Qiu, M., & Xiao, X. (2023). Changes in travel behaviors and intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery period: A case study of China. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 41, 1–17.

- Fennell, D. A. (2001). A content analysis of ecotourism definitions. Current Issues in Tourism, 4(5), 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500108667896

- Fishbein, M. (1967). Readings in attitude theory and measurement. John Wiley & Sons.

- Fong, L. H. N., Zhang, C. X., & Wang, Z. (2023). Tourist–host identity risk: Scale development and consequences. Journal of Travel Research, 62(7), 1588–1604. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875221127680

- Frechtling, D. C. (2004). Assessment of tourism/hospitality journals’ role in knowledge transfer: An exploratory study. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268230

- Fuchs, G., Uriely, N., Reichel, A., & Maoz, D. (2013). Vacationing in a terror-stricken destination: Tourists’ risk perceptions and rationalizations. Journal of Travel Research, 52(2), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512458833

- Gao, Y. L., Mattila, A. S., & Lee, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of behavioral intentions for environment-friendly initiatives in hospitality research. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 54, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.01.010

- Gartner, W. C. (1994). Image formation process. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2(2-3), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v02n02_12

- Goodrich, J. N. (1977). Differences in perceived similarity of tourism regions: A spatial analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 16(1), 10–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757701600104

- Hadinejad, A., Kralj, A., Scott, N., Moyle, B. D., & Gardiner, S. (2022). Tourism marketing stimulus characteristics: A self-validation analysis of Iran. Journal of Travel Research, 61(2), 235–251.

- Hadinejad, A., Moyle, B. D., Kralj, A., & Scott, N. (2019a). Physiological and self-report methods to the measurement of emotion in tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(4), 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1604937

- Hadinejad, A., Noghan, N., Moyle, B. D., Scott, N., & Kralj, A. (2021). Future research on visitors’ attitudes to tourism destinations. Tourism Management, 83, 104215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104215

- Hadinejad, A., Nunkoo, R., D. Moyle, B., Scott, N., & Kralj, A. (2019b). Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A review. Tourism Review, 74(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-01-2018-0003

- Hall, C. M. (2011). Publish and perish? Bibliometric analysis, journal ranking and the assessment of research quality in tourism. Tourism Management, 32(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.07.001

- Han, H., Al-Ansi, A., Olya, H. G., & Kim, W. (2019). Exploring halal-friendly destination attributes in South Korea: Perceptions and behaviors of muslim travelers toward a non-muslim destination. Tourism Management, 71, 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.10.010

- Hosany, S. (2012). Appraisal determinants of tourist emotional responses. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511410320

- Hsu, C. H., Cai, L. A., & Li, M. (2010). Expectation, motivation, and attitude: A tourist behavioral model. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 282–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509349266

- Huang, S., & Hsu, C. H. (2009). Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. Journal of Travel Research, 48(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287508328793

- Huang, S., & van der Veen, R. (2019). The moderation of gender and generation in the effects of perceived destination image on tourist attitude and visit intention: A study of potential Chinese visitors to Australia. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 25(3), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766718814077

- Hunt, C. A., Gao, J., & Xue, L. (2014). A visual analysis of trends in the titles and keywords of top-ranked tourism journals. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(10), 849–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.900000

- Hunter, W. C. (2011). Rukai indigenous tourism: Representations, cultural identity and Q method. Tourism Management, 32(2), 335–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.003

- Ivanov, B., Dillingham, L. L., Parker, K. A., Rains, S. A., Burchett, M., & Geegan, S. (2018). Sustainable attitudes: Protecting tourism with inoculation messages. Annals of Tourism Research, 73, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.08.006

- Jalilvand, M. R., Samiei, N., Dini, B., & Manzari, P. Y. (2012). Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: An integrated approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1-2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.001

- Jordan, E. J., Bynum Boley, B., Knollenberg, W., & Kline, C. (2018). Predictors of intention to travel to Cuba across three time horizons: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Travel Research, 57(7), 981–993. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517721370

- Jurado, E. N., Damian, I. M., & Fernández-Morales, A. (2013). Carrying capacity model applied in coastal destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.03.005

- Kee-Fu, N., & Ap, J. (2007). Tourists’ perceptions of relational quality service attributes: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Travel Research, 45(3), 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287506295911

- Kim, S. B., & Kwon, K. J. (2018). Examining the relationships of image and attitude on visit intention to Korea among Tanzanian college students: The moderating effect of familiarity. Sustainability, 10(2), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020360

- Kim, S., & Lehto, X. Y. (2013). Projected and perceived destination brand personalities: The case of South Korea. Journal of Travel Research, 52(1), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512457259

- Koster, R. L., & Lemelin, R. H. (2009). Appreciative inquiry and rural tourism: A case study from Canada. Tourism Geographies, 11(2), 256–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680902827209

- Kuhn, T. S. (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

- Kutlay, M. (2019). Political economy of Turkey (1980–2001). In M. Kutlay (Ed.), The political economies of Turkey and Greece: Crisis and change (pp. 33–70). International political economy series. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Le, T. H., Arcodia, C., Novais, M. A., & Kralj, A. (2021). Proposing a systematic approach for integrating traditional research methods into machine learning in text analytics in tourism and hospitality. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(12), 1640–1655. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1829568

- Lee, R., & Lockshin, L. (2012). Reverse country-of-origin effects of product perceptions on destination image. Journal of Travel Research, 51(4), 502–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511418371

- Lee, K. H., & Scott, N. (2015). Food tourism reviewed using the paradigm funnel approach. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, 13(2), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15428052.2014.952480

- Li, S., Walters, G., Packer, J., & Scott, N. (2017). A comparative analysis of self-report and psychophysiological measures of emotion in the context of tourism advertising. Journal of Travel Research, 1–15.

- Li, F. S., & Wang, B. (2020). Social contact theory and attitude change through tourism: Researching Chinese visitors to North Korea. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 1–8.

- Liang, S., Schuckert, M., Law, R., & Masiero, L. (2017). The relevance of mobile tourism and information technology: An analysis of recent trends and future research directions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(6), 732–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1218403

- Loda, M. D., Norman, W., & Backman, K. F. (2007). Advertising and publicity: Suggested new applications for tourism marketers. Journal of Travel Research, 45(3), 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287506292688

- Lu, J., Chan, C. S., & Cheung, J. (2020). Investigating volunteer tourist experience in Embodiment Theory: A study of Mainland Chinese market. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(7), 854–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2020.1837712

- Ma, J., Gao, J., Scott, N., & Ding, P. (2013). Customer delight from theme park experiences: The antecedents of delight based on cognitive appraisal theory. Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 359–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.02.018

- Maccannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603.

- Malloy, D. C., & Fennell, D. A. (1998). Codes of ethics and tourism: An exploratory content analysis. Tourism Management, 19(5), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00042-9

- Manosuthi, N., Lee, J. S., & Han, H. (2020). Impact of distance on the arrivals, behaviours and attitudes of international tourists in Hong Kong: A longitudinal approach. Tourism Management, 78, 103963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.103963

- McKercher, B. (2005). A case for ranking tourism journals. Tourism Management, 26(5), 649–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.04.003

- McLeod, S. H. (1991). The affective domain and the writing process: Working definitions. Journal of Advanced Composition, 95–105.

- Moyle, B., Moyle, C. L., Ruhanen, L., Weaver, D., & Hadinejad, A. (2021). Are we really progressing sustainable tourism research? A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1817048

- Moyle, B. D., Weaver, D. B., Gössling, S., McLennan, C. L., & Hadinejad, A. (2022). Are water-centric themes in sustainable tourism research congruent with the UN Sustainable Development Goals? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–16.

- Mura, P., Mognard, E., & Sharif, S. P. (2017). Tourism research in non-English-speaking academic systems. Tourism Recreation Research, 42(4), 436–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2017.1283472

- Naoi, T., Yamada, T., Iijima, S., & Kumazawa, T. (2011). Applying the caption evaluation method to studies of visitors’ evaluation of historical districts. Tourism Management, 32(5), 1061–1074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.09.005

- Nunkoo, R., Smith, S. L., & Ramkissoon, H. (2013). Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.673621

- Nyaupane, G. P., & Poudel, S. (2011). Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1344–1366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.006

- Oh, H., & Hsu, C. H. (2001). Volitional degrees of gambling behaviors. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 618–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00066-9

- Ong, F., Vorobjovas-Pinta, O., & Lewis, C. (2023). Lgbtiq+ identities in tourism and leisure research: A systematic qualitative literature review. Gender and Tourism Sustainability, 21–44. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003329541-3

- Park, I. J., Kim, J., Kim, S. S., Lee, J. C., & Giroux, M. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on travelers’ preference for crowded versus non-crowded options. Tourism Management, 87, 1–16.

- Petty, R. E., Briñol, P., & Tormala, Z. L. (2002). Thought confidence as a determinant of persuasion: The self-validation hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(5), 722–741. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.722

- Pike, S., & Ryan, C. (2004). Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. Journal of Travel Research, 42(4), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504263029

- Pizam, A., Fleischer, A., & Mansfeld, Y. (2002). Tourism and social change: The case of Israeli ecotourists visiting Jordan. Journal of Travel Research, 41(2), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728702237423

- Poria, Y., Biran, A., & Reichel, A. (2009). Visitors’ preferences for interpretation at heritage sites. Journal of Travel Research, 48(1), 92–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287508328657

- Poria, Y., Reichel, A., & Cohen, R. (2011). World heritage site—Is it an effective brand name? A case study of a religious heritage site. Journal of Travel Research, 50(5), 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510379158

- Prebensen, N. K., Woo, E., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. (2013). Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. Journal of Travel Research, 52(2), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512461181

- Quintal, V. A., Lwin, M., Phau, I., & Lee, S. (2019). Personality attributes of botanic parks and their effects on visitor attitude and behavioural intentions. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 25(2), 176–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766718760089

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Ramakrishna, S., Hall, C. M., Esfandiar, K., & Seyfi, S. (2023). A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1497–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1775621

- Reddy, M. V., Nica, M., & Wilkes, K. (2012). Space tourism: Research recommendations for the future of the industry and perspectives of potential participants. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1093–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.11.026

- Riscinto-Kozub, K., & Childs, N. (2012). Conversion of local winery awareness: An exploratory study in visitor vs non-visitor attitude and perception. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 24(4), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1108/17511061211280338

- Rittichainuwat, B. N., & Chakraborty, G. (2009). Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tourism Management, 30(3), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.08.001

- Ruhanen, L., Weiler, B., Moyle, B. D., & McLennan, C.-l. J. (2015). Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(4), 517–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.978790

- Ryan, C. (2005). The ranking and rating of academics and journals in tourism research. Tourism Management, 26(5), 657–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.05.001

- Schultz, A., Goertzen, L., Rothney, J., Wener, P., Enns, J., Halas, G., & Katz, A. (2018). A scoping approach to systematically review published reviews: Adaptations and recommendations. Research Synthesis Methods, 9(1), 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1272

- Sharifpour, M., Walters, G., Ritchie, B. W., & Winter, C. (2014). Investigating the role of prior knowledge in tourist decision making: A structural equation model of risk perceptions and information search. Journal of Travel Research, 53(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513500390

- Shih, D. (1986). Vals as a tool of tourism market research: The Pennsylvania experience. Journal of Travel Research, 24(4), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728758602400401

- Simpson, J. J., & Simpson, P. M. (2017). Emotional solidarity with destination security forces. Journal of Travel Research, 56(7), 927–940. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516675063

- Simpson, J. J., Simpson, P. M., & Cruz-Milán, O. (2016). Attitude towards immigrants and security: Effects on destination-loyal tourists. Tourism Management, 57, 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.021

- Skavronskaya, L., Scott, N., Moyle, B., Le, D., Hadinejad, A., Zhang, R., … Shakeela, A. (2017). Cognitive psychology and tourism research: State of the art. Tourism Review, 72(2), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2017-0041

- Small, J., Darcy, S., & Packer, T. (2012). The embodied tourist experiences of people with vision impairment: Management implications beyond the visual gaze. Tourism Management, 33(4), 941–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.09.015

- Soliman, M., Lyulyov, O., Shvindina, H., Figueiredo, R., & Pimonenko, T. (2021). Scientific output of the European Journal of Tourism Research: A bibliometric overview and visualization. European Journal of Tourism Research, 28, 2801–2801. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v28i.2069

- Sönmez, S., & Sirakaya, E. (2002). A distorted destination image? The case of Turkey. Journal of Travel Research, 41(2), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728702237418

- Sparks, B., & Pan, G. W. (2009). Chinese outbound tourists: Understanding their attitudes, constraints and use of information sources. Tourism Management, 30(4), 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.10.014

- Spasojevic, B., Lohmann, G., & Scott, N. (2018). Air transport and tourism-a systematic literature review. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(9), 975–997.

- Stepchenkova, S., & Shichkova, E. (2017). Country and destination image domains of a place: Framework for quantitative comparison. Journal of Travel Research, 56(6), 776–792. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516663320

- Sun, M., Ryan, C., & Pan, S. (2015). Using Chinese travel blogs to examine perceived destination image: The case of New Zealand. Journal of Travel Research, 54(4), 543–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514522882

- Tang, L. R., Jang, S. S., & Morrison, A. (2012). Dual-route communication of destination websites. Tourism Management, 33(1), 38–49.

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2003). Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 3–50). Sage.

- Tsironis, C. N., Sylaiou, S., & Stergiou, E. (2022). Risk, faith and religious tourism in second modernity: Visits to Mount Athos in the COVID-19 era. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 17(5), 516–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2021.2007252

- Van der Veen, R., & Song, H. (2014). Impact of the perceived image of celebrity endorsers on tourists’ intentions to visit. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513496473

- Vogt, C. A., & Andereck, K. L. (2003). Destination perceptions across a vacation. Journal of Travel Research, 41(4), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503041004003

- von Benzon, N. (2019). Informed consent and secondary data: Reflections on the use of mothers’ blogs in social media research. Area, 51(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12445

- Walker, M., Kaplanidou, K., Gibson, H., Thapa, B., Geldenhuys, S., & Coetzee, W. (2013). Win in Africa, with Africa”: Social responsibility, event image, and destination benefits. The Case of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa. Tourism Management, 34, 80–90.

- Wang, Y.-F. (2016). Modeling predictors of restaurant employees’ green behavior: Comparison of six attitude-behavior models. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 58, 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.07.007

- Wang, J., Liu-Lastres, B., Ritchie, B. W., & Mills, D. J. (2019). Travellers’ self-protections against health risks: An application of the full Protection Motivation Theory. Annals of Tourism Research, 78, 102743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102743

- Weaver, D. B., & Lawton, L. J. (2004). Visitor attitudes toward tourism development and product integration in an Australian urban-rural fringe. Journal of Travel Research, 42(3), 286–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503258834

- Weiler, B., Torland, M., Moyle, B. D., & Hadinejad, A. (2018). Psychology-informed doctoral research in tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(3), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2018.1460081

- Witbooi, M., Cupido, C., & Ukpere, W. I. (2011). Success factors of entrepreneurial activity in the overberg region of western cape. South Africa.

- Xiao, H., & Smith, S. (2006). The making of tourism research: Insights from a social sciences journal. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 490–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2006.01.004

- Yang, M. J. H., Yang, E. C. L., & Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2020). Host-children of tourism destinations: Systematic quantitative literature review. Tourism Recreation Research, 45(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1662213

- Ye, S., Lee, J. A., Sneddon, J. N., & Soutar, G. N. (2020). Personifying destinations: A personal values approach. Journal of Travel Research, 59(7), 1168–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519878508

- Yüksel, A., & Akgül, O. (2007). Postcards as affective image makers: An idle agent in destination marketing. Tourism Management, 28(3), 714–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.026

- Zhang, H., Gursoy, D., & Xu, H. (2017). The effects of associative slogans on tourists’ attitudes and travel intention: The moderating effects of need for cognition and familiarity. Journal of Travel Research, 56(2), 206–220. doi:10.1177/0047287515627029