ABSTRACT

“Plant-based beverages,” “plant-based milk” and “milk alternatives” are terms commonly used to refer to drinks made from plants, such as legumes, cereals, pseudocereals, and nuts. This study aimed to evaluate the perception and consumption of nut-based beverages by Brazilian consumers. An online questionnaire was prepared with socioeconomic and consumption questions and disseminated in digital media following established ethical standards. The almond beverage was the drink most consumed by the respondents and the Brazil nut beverage was the one that most aroused the most interest among the respondents. Nut beverages were elected as the healthiest, most sustainable, and nutritionally best beverages in comparison with soy beverages and cow’s milk. Fruits such as strawberries and bananas were cited as alternatives for flavoring these beverages. Consumers considered the possibility of fully and partially replacing cow’s milk and soy drinks with nut beverages. Interest in these along with plant-based milk was not restricted to the vegan segment, and these products were indicated as having strong potential for inclusion in the diets of omnivorous consumers. More studies on buying, purchase intention, acceptance, knowledge, and neophobia among Brazilian consumers are necessary for the development of these beverages, especially with more representative samples of society.

Introduction

“Plant-based beverages,” “plant-based milk,” and “non-milk beverages” or “milk alternatives” are terms commonly used to refer to beverages made from plants such as legumes (beans, soybeans, peanuts), cereals (oats, rice, sorghum), pseudocereals (quinoa, amaranth) and nuts (walnuts, Brazil nuts, almonds, hazelnuts, cashew nuts).[Citation1] Some of these nut-based products have great relevance for their specific sensory characteristics and nutritional profiles, which are different from other plant-based groups. For example, they are rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, proteins, and selenium.[Citation2]

The consumption of plant-based beverages in Brazil and the world is steadily rising.[Citation3–7] Although milk consumption is still strong among plant-based beverages, the market is promising, although some information barriers still need to be overcome for better insertion of these products. In Brazil, the consumption of milk and dairy products is still higher than the consumption of nuts and other oilseeds. Although the southern region of Brazil has stronger demand for nuts than the country’s other regions, the consumption there does not exceed 1.5% of total food consumption.[Citation8]

“Plant-based beverages” (PBBs) are sought, especially by vegan consumers as milk substitutes with functional potential and health benefits. Among the potentials of these beverages are their pre and probiotic viability.[Citation9,Citation10] Concerns for the environment, animal welfare, and world hunger are also relevant factors that drive the expansion of demand for these beverages.[Citation11] In this context, PBBs are often considered by consumers as superior drinks in terms of health, wellness, sustainability, and nutritional value. However, these advantages are still controversial and very inconsistent in the literature.[Citation12–14] Another relevant question is whether these beverages are microbiologically safe.[Citation15]

The tendency to replace animals with plants as sources of human food is global.[Citation16,Citation17] Despite being a subject of growing interest, both by industry and the academic community, some points are still not well elucidated in the literature. In addition, the population’s knowledge about these products and the factors that most impact their choices are matters that still need to be widely discussed. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the perception and consumption of beverages based on nuts by Brazilian consumers.

Methodology

Study location and research method

A questionnaire was prepared with socioeconomic and consumption questions. This was made available online for eight months, and disseminated via digital media under established ethical standards. The questionnaire was segmented as follows: Initial screening: Informed consent form; 1st section: questions related to socioeconomic status, subsequently classified according to the Brazilian criterion established by ABEP;[Citation18] 2nd section: “Word Association” containing possibilities for four words or expressions related to the question: “Write the expression, association, word, sensation, emotion or thought when saying: ‘nut beverages’”; 3rd section: questions about the consumption and knowledge of nut beverages; 4th section: buying intention and comparison among nut beverages, soy beverages, and cow’s milk.

Study population and technique

The “Word Association,” categorization and analysis were performed according to the proposal of Alcantara et al.[Citation19] and Guerrero et al.,[Citation20] where, the terms obtained in the word association test were grouped into categories and dimensions. The categorization process was carried out by two researchers with previous experience in the methodology, and the categorization was reviewed by an additional researcher. The final results were obtained by consensus. The frequency of mention of categories and dimensions was calculated by the number of consumers who mentioned the word in the test. Categories with under 5% mention were excluded. The Chi-square test was used to verify the difference between categories and dimensions according to consumer groups. After analyzing these results, we separated the respondents into two groups: “never tasted the drink” and “already tasted or consumed the drink.”

Ethical considerations

Before being released to the public, the questionnaire was submitted to the Ethics and Research Committee of the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro and was approved under CAAE protocol number 57,364,922.40000.5285. An informed consent form (TCLE) was made available to the participants, and where signatures were collected for permission to continue the study. All data considered sensitive were protected and respondents were told-communicated that only general data would be used for academic purposes.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated followed by ANOVA with the Tukey posttest. Significant values of p < .05 were considered in all analyses. To compare the frequency of socioeconomic data, the Chi-square test was performed.

Results

Socioeconomic data, dietary style, and consumption

The sample consisted of 300 individuals after excluding those who accessed the questionnaire but did not confirm their interest in participating. Most of them (57.3%) had never tasted a nut beverage (X2 = 6.45; p = .0111). However, most respondents (95%) expressed willingness to try these drinks. Women had tasted or regularly consumed nut beverages the most, differing significantly from men (X2 = 4.586; p = .0322) ().

Table 1. Main socioeconomic results of the respondents.

In terms of age, most respondents were 26–36 years old, followed by the 60 years or older group, and to a lesser extent, the 48–58-year-old group (X2 = 27.83; p < .0001). People aged 26–36 were the ones who consumed the most or had already consumed the drinks and were also the ones who had tasted them least, proportionally, followed by the elderly (X2 = 10.11; p = .0386). However, that group was one of those with the least contact with the drink. Most elderly respondents were willing to try the nut beverage; only one elderly person reported not having any interest in tasting it, corresponding to 1.6% of the group in question.

Regarding the economic level, the middle classes (B and C) were the most representative of the respondents and the lowest classes (D and E) and highest (A) were the least prevalent (X2 = 207.1; p < .0001). However, the economic level of the participants did not influence the opportunity to try the drink (X2 = 6.172; p = .2898) Individuals with a college degrees were the majority in the study (X2 = 141.7; p < .0001), but this factor also did not influence product experimentation (X2 = 1.265; p = .5313).

About the dietary style, respondents who declared themselves omnivores were in the great majority (91%), versus vegetarians/vegans (9%), differing significantly (X2 = 201.7 p < .0001). Of the declared omnivores (n = 273), 38 respondents (13.9%) reported not consuming milk under any circumstance; of these individuals, only 3 (7.9%) were not willing to try the nut beverage (X2 = 26.95; p < .0001). Of the total number of omnivores who consumed milk (n = 235), only 4 individuals (1.7%) were not willing to try the nut beverage. Statistically equal proportions of vegetarians/vegans consumed (62.9%) and did not consume milk (37.1%) (X2 = 1.815; p = .1779), while both groups of vegetarians (100%) were willing to try the nut beverages. The eating habit was associated with whether respondents had already tasted the drink. Vegetarians already had greater contact with the drink compared to omnivores (X2 = 14.95; p = .0001)

Purchase intention and comparison between nut beverages

Participants who had already tried a nut beverage were asked “Which nut beverages have you already tried?.” Almond (71.9%) and cashew nut drinks (61.7%) received the highest mentions, while pecan (2.3%) and baru nut beverages (0.8%) were mentioned the least. When asked about “Which nut beverages do you dislike the most and which attributes of these beverages do you most dislike?,” almond (27%) and cashew nut beverages (23.4%) were the most chosen, and the attributes flavor (57.8%) and texture (14.1%) were the most disliked. For all these questions, participants could choose more than one suggested option or even add one that had not been presented.

The respondents in the group who had never tasted a nut beverage were asked “Which nut beverage would you be willing to taste?” Brazil nut (90.1%), cashew nut (85%), and walnut (85%) received the most mentions, while baru nut (0.6%) and Portuguese chestnut (0.6%) were the least mentioned. Among the elderly, this trend continued with some minor changes; Brazil nut (95%) remained the most mentioned, followed by walnut (76%) and cashew nut (73.9%). For all these questions, participants could choose more than one suggested option or even add one that had not been presented.

The question “What health benefit do you believe is associated with this beverage?” was applied to all participants. The benefits most cited by both respondents (there was no difference between groups G1 and G2, p = .879) were “antioxidant action” “prevention of inflammation” and “cholesterol reduction,” and with fewer citations “prevention of neurological diseases.” Fewer than 3% responded that they did not know/believe in any benefit linked to the product. For all respondents (consumers and non-consumers of nut beverages), more than 68% said they would be willing to consume or buy the beverage if it had a proven nutritional or health benefit, and less than 5% would not buy it, although there was no significant difference between the groups (p = .659). In a spontaneous question (no options offered) about which fruit flavor would be attractive for a nut beverage, the flavors strawberry (12.9%), banana (6.4%), grape (3%), açaí (3%), cashew fruit (2.6%) and apple (1.3%) were the most cited.

The most relevant factors for all respondents, when asked “What matters most when buying a nut beverage?” were “taste/flavor,” “price” and “health benefits,” and to a lesser extent “lactose-free,” “vegan” and “brand” ().

Table 2. Summary of pairwise comparisons for factor (Tukey, HSD) about relevant attributes for purchase intention of all respondents.

Nut beverages were chosen by both groups as the healthiest, most sustainable, and nutritionally best drinks compared to soy drinks and cow’s milk. However, these other beverages did not differ significantly, indicating that both cow’s milk and soy beverages were less healthy, less nutritious, and not as sustainable (), with scores averaging below 3 on the scale. When questioned about the possibility of substituting the soy beverage for the nut beverage, more than 50% of both groups (G1 and G2) said they were willing to completely substitute this beverage, and only 12.5% (G1) and 1.14% (G2) said they were not, showing that people who never tasted it did not reject the idea of replacing their customary beverages. There was no significant difference between the groups regarding the replacement of soy beverages with a NB (p = .06). The same question was asked regarding cow’s milk, and G1 had the highest percentages distributed between the partial (36.7%) and total (35.2%) replacement options, demonstrating that people who had already tried NBs would be willing to replace them in some way. In turn, in G2 there was a greater distribution of percentages between those who would replace partially (40.1%) and totally (20.3%) and those who were in doubt (maybe/I don’t know) (28.5%), demonstrating that the people who had not tried a NB would be less willing to substitute their existing beverage preference (but not saying they wouldn’t). In this question, there was a significant difference between the groups in the statements “would totally replace” (p < .01) and “maybe/I don’t know” (p < .05), indicating that although the G2 respondents were willing to try NBs, partial replacement would be a greater possibility than the total in G1, because it was associated with insecurity/doubt regarding the drink due to the fact they had never tried it, but it did not preclude the possibility of including it in the diet of this group.

Figure 1. Results of comparisons between beverages when asked about nutritional superiority, the healthiest, and the most sustainable.

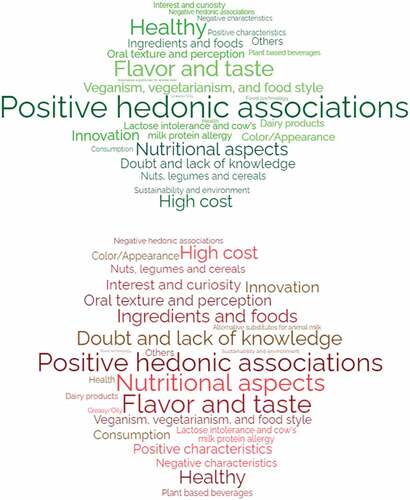

In all, the word association (WA) terms were classified into 26 categories, and these into 10 dimensions (). G2 had the highest citation frequency compared to G1 for the categories consumption, health, negative characteristics, fatty/oily, positive characteristics, color/appearance, doubt, and lack of knowledge, while G1 had a higher citation of sustainability and environment and positive hedonic associations, thus showing some divergences between these groups.

Table 3. Percentage of respondents for each of the dimensions and categories identified in the word association test.

G2 had significant results in the description of WA for many different categories. While talking about consumption and positive health characteristics of nut drinks, the respondents often mentioned the negative sensory characteristics of the drinks; showing that people who have never tried the product did not have a convergent opinion about it, and also did not have a more uniform opinion about it. This was confirmed since the category doubt/lack of knowledge was most cited by G2.

G1, composed of consumers who had had the experience of tasting one of these drinks, more often mentioned positive hedonic associations, demonstrating the acceptance of this product by this group; also citing sustainability and environmental factors as points that influence the purchase of this product. This same group demonstrated their opinion on this point when they listed the nut drink over the soy and milk drinks, regardless of which was nutritionally better.

Concerning the word cloud, which illustrates the results of the table with the most substantial categories cited in highlight, among the most cited by G2 was the category positive hedonic perception, despite being significantly smaller than G1. It is important to point out that nut drinks generated positive acceptance from these consumers who never had sensorial contact from experimentation. The G2 word cloud also corroborates what is reported in , with greater emphasis on more categories, without as much uniformity of citations as in the G1 cloud. The respondents that had never tried a NB seemed not to have a general point of view about the product ().

Discussion

It is noteworthy that nut beverages, despite their increasing acceptance, are still very new and not widely consumed by the Brazilian public in general. This study revealed that the majority of the respondents had not tried NBs yet (), due to several factors, such as high price, rejection of new products, unavailability, and culture. However, a significant number of respondents (even the omnivores) stated they would be willing to try this beverage, demonstrating it is not limited to the vegan/vegetarian niche. Indeed, the vegetarian/vegan respondents reported having more contact with this type of drink. In this regard, Cardello et al.[Citation21] also observed the possibility of acceptance of plant-based beverages by both groups.

Neophobia can be considered an impediment to the acceptance of products such as PBBs. However, in general, Brazilians have demonstrated a greater willingness to experiment and accept new plant-based products.[Citation22] Although experimentation with the drink was lower in our study, attributes such as “curiosity” and “innovation” were mentioned by this public, also reinforcing possible interest in this drink (). According to Mancini and Antonioli,[Citation23] institutional, technological, and cultural barriers still need to be overcome for the inclusion of plant-based products in the Italian market.

Although some works have associated the difficulty of access to these drinks due to high prices,[Citation3,Citation24,Citation25] our study indicated that the most diverse social classes present in Brazil have already had contact with this drink (). However, according to , high cost was mentioned mainly by those who had already consumed the drink, as also indicated in , where price is identified as one of the most relevant factors for the purchase of these products, corroborating the results of other studies. Thus, we cannot deny that high prices can be a factor keeping these beverages from becoming more popular among consumers in general. Devising strategies that make these products cheaper and more accessible is hence necessary.

Another factor that can be considered influential in addition to the price is the social and rational issues for the consumption of these drinks, whereby the lack of knowledge about the products and even the influence of the niche in which individuals are inserted can increase their chances of accepting PBBs in general.[Citation26] Clegg et al.[Citation3] noted that all PBBs were more expensive than similar dairy products. In this same regard, Malek and Umberger[Citation25] pointed out that more than half of the interviewed consumers had never bought plant-based products, especially due to a lack of interest in new beverages in general, sensory characteristics, lack of familiarity, and price.

An interesting result of our study was the fact that although the elderly were a small group in this study, most of them expressed willingness to try an NB. As in many other countries, the elderly are a large and increasing portion of the Brazilian population, so products aimed at them have good potential.[Citation8,Citation27–29] In that respect, Moss et al.[Citation30] emphasized the need for better identification and characterization of the diverse segments of consumers in society, so that in future studies researchers can develop and improve PBBs to meet the needs and expectations of the various consumers and their peculiar preferences.

The NB made with almonds was the most consumed and tried, although considered both the most pleasant and least pleasant drink in our study. This is because this nut has the greatest appeal and use for the manufacture of these drinks in several countries, including Brazil.[Citation3,Citation11,Citation31–33] This result should be observed with more attention by the food industry since the use of regional nuts could gain greater prominence by making the product cheaper and promoting local agriculture. Reinforcing this information, Brazil nuts and cashews had the most mentions by respondents who had never tasted an NB but said they would be willing to try one, demonstrating these are two nuts with strong potential for the development of NBs in Brazil.

Taste/flavor was a very important attribute both for purchase () and for acceptance of the drink. Undoubtedly, this factor is extremely relevant and is constantly attributed to the weaknesses of PBBs.[Citation26] One of the possible explanations for flavor issues is that consumers often expect NBs to taste similar to milk, but this mimicry is not possible due to the unique characteristics of each nut in comparison with milk.[Citation21,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35] Another noteworthy point is that NBs also differ sensorially from some PBBs, with a thicker texture, saltier flavor, and more umami notes.[Citation5]

Despite being an important factor, “taste/flavor” does not seem to be an impossible obstacle to overcome by the product. For example, in a study carried out in different regions of Europe, the individuals interviewed indicated they wanted smaller sensory modifications for the alternative categories of PBBs, milk, and yogurt than for cheese and meat substitutes, where these modifications were greater and more significant.[Citation36] In this sense, technologies can be applied to improve the taste and palatability of NBs.[Citation11,Citation30,Citation33,Citation37] Heat treatment, for example, can be used to improve the flavor profile of NBs. In this regard, Vaikma et al.[Citation5] found that after treatment, hazelnut beverages had a higher content than almonds of pyrazines and benzaldehydes, important compounds for flavor nuances, thus improving their acceptance.

Another point suggested to improve this sensory aspect is the flavoring and aromatization of these NBs, as observed in studies by Acquah et al.[Citation24] and Moss et al.,[Citation30] who reported that flavored PBBs were more accepted. In this sense, the respondents in the present study mentioned strawberry, banana, grape, açaí, cashew fruit, and apple as being flavorings for NB blends, indicating good prospects for flavoring these drinks and consequently improving their public acceptance. Texture has also been mentioned in surveys as an unpleasant factor of NBs. This attribute is also a challenge to the marketing of PBBs.[Citation2,Citation30]

The respondents were overwhelmingly more likely to buy NBs if they have proven health benefits. This was the opinion both of those who already consumed them and those who had not. The concern and association between consumption and health are common in this sense, even if consumers do not know how to identify exactly which benefit is associated with this product. Our results also corroborate the findings of Acquah et al.,[Citation24] who observed that consumers expressed a willingness to purchase the concept drink, citing innovation, taste, and health benefits as key drivers for purchasing a drink made with tiger nuts.

Despite our initial expectation that the respondents in G1 would be more likely to have functional knowledge of the product than the members of G2, both mentioned the same associations of health benefits and nutritional quality (), healthiness () and sustainability (). The correct understanding by laypeople about these beverages is still somewhat debatable, and the absence of understandable didactic information can confuse the interpretation and knowledge of PBBs in comparison with milk.[Citation7] Thus, the lack of specific regulations on plant-based products to inform consumers and strengthen the productive sector also needs to be overcome.[Citation38]

The knowledge and perception of the composition of milk and its technological processes can be correlated and directly impact the opinion of consumers about its healthiness. When consumers are unaware of some simple processes such as pasteurization, filtration, and homogenization, this can lead them to believe that a product can be harmful to health.[Citation39] Hence, these individuals often misunderstand their perception of the benefits of PBBs, since they are unaware that these methods can also be applied to them.

Consumers are increasingly interested in functional products with greater added nutritional value and health benefits.[Citation24,Citation40] We also noted this in our study, as indicated in , which points to “health benefits” as one of the main factors for purchasing these products. As seen in , this attribute was mentioned by both groups concerning NBs.

Regarding the nutritional aspect, the discussion about the superiority of PBBs to cow’s milk is still controversial.[Citation2] Silva and Smetana[Citation13] reported the lack of micronutrient data for the comparison of PBBs with animal milk. In general, studies point to PBBs as being nutritionally inferior to milk.[Citation3,Citation31,Citation32] Another question is related to the antinutritional factors found in these drinks, especially soy beverages.[Citation6] Clegg et al.[Citation3] reported that cow’s milk has more energy, saturated fat, carbohydrates, protein, vitamin B2, vitamin B12, and iodine, and less fiber and free sugars than plant-based alternatives (P < .05). However, since nuts are excellent sources of fat, protein, and micronutrients like selenium,[Citation41–43] this statement is not valid for all PBBs, so NBs can be a differentiator in this segment.

Although the respondents in G2 were willing to try NBs, partial replacement would be a greater possibility than total replacement in G1. The reason was associated with security/doubts regarding the beverages due to the fact the respondents had never tried them, but it did not preclude the possibility of including NBs in the diets of the members of this group. These results can be explained because consumers who drink milk often do so out of habit or because they like the taste, not just based on perceived health benefits or nutritional content.[Citation44]

Some further considerations on the nutritional issue are important since we observed that the general group would be willing to replace both soy drinks and cow’s milk with NBs. Replacing milk with PBBs is a good option because they are practical, but not from a nutritional point of view. Nevertheless, they are healthy products with good nutritional characteristics, despite not meeting all the energy and nutritional needs of an individual.[Citation3,Citation11,Citation31] The fortification of these beverages with minerals and vitamins, such as vitamin D, is a possible alternative to enhance competition with cow’s milk.[Citation37,Citation45]

Sustainability also was a relevant factor in this study. Similar to the results found by Schiano et al.[Citation46] in the comparison of PBBs with milk. The respondents in both groups stated that NBs are the most sustainable. This perception was greater in G1 (), indicating this is an important attribute for this group. This may be related to the lifestyle of people who already consume this type of drink. McCarthy et al,[Citation44] in a study in New Zealand, suggested that for those drinking only nondairy alternatives for sustainability reasons, milk from grass-fed cows can be attractive due to the lower carbon footprint, as long as the taste is appealing. However, in general, replacing animal products with plant-based products is seen as being a way to reduce the impact of eating habits on the environment.[Citation16] Environmental impacts and animal welfare undoubtedly drive consumer demand for plant-based foods[Citation4,Citation47]

Measuring sustainability is not easy, so knowing whether consumers understand the points that are taken into account for this characterization is extremely important.[Citation44,Citation46] Moss et al.[Citation30] reported the need to include this theme in sensory tests and examined what factors contribute to or characterize sustainability, similar to what we did in this study. The way the public is informed about this topic directly influences people’s perception of the product, along with the type of packaging/labeling and organic status.[Citation46] This demonstrates that didactic and clear labeling can improve the perception of the product.[Citation44]

The conclusion that NBs and PBBs are more sustainable than animal milk is still controversial. Most data on environmental impacts are related to soy and almond-based beverages, and the most common impact quantified has been greenhouse gas emissions.[Citation32] In this sense, it is impossible to make a complete comparison between the drinks in terms of environmental impact. Silva and Smetana[Citation13] stated that overall, the environmental impact of PBBs is lower than that of milk, with exceptions in some categories. However, the animal handling method (confined cattle produce less polluting gases) and the type of forage cultivation (with or without the use of fertilizers) can variably impact sustainability and make this modality more or even less sustainable.[Citation48] An argument also in favor of the sustainability of NBs is that the byproducts of this category have good potential for other uses in the food industry, which can mitigate their environmental impact.[Citation49] Another hypothesis raised is that harvesting of some nuts (Brazil nuts and cashew nuts, for example) is part of local sustainable extractivism,[Citation41,Citation50] leading to lower consumption of water and fertilizers (in comparison with soybeans) and less emission of greenhouse gases (in comparison with cattle), which is a positive point regarding the environmental impact of these products.

The greasy/oily category was more relevant for G2 (). This can be explained by the fact they had never tasted NBs and because nuts are oleaginous fruits, the expectation is that this drink will be very fatty. Despite being rich in fat, tree nuts are rich in polyunsaturated fats and omega 3 (especially walnuts), making them beneficial for health.[Citation42,Citation43,Citation51] Concerns about the allergenic potential and “lactose-free” were prevalent in both groups (), although they were not important factors for purchasing the product (). In general, despite concerns about microbial contamination, NBs are safe for health,[Citation15,Citation31] and “lactose-free” is a great advantage and attraction of these products, especially for vegans and lactose-intolerant individuals.[Citation10,Citation52]

Conclusion

The consumption of beverages based on nuts and PBBs was not restricted to the vegan/vegetarian segment of this study. These, therefore, these products had a strong potential for consumption by omnivorous consumers as a possible alternative to milk and soy-based beverages. Completely replacing milk with nut drinks and PBBs from a nutritional standpoint is still a hurdle, but fortification of these drinks can partially overcome this drawback hurdle by establishing nutritional equivalence. More studies with an emphasis on neophobia, product acceptability and methods to improve the sensory acceptance of PBBs and NBs need to be performed and scaled up. It is also important to develop products aimed at age groups, such as the elderly. However, the most important factors are to reduce the cost of these drinks and publicize their health benefits and make them more accessible, which are necessary and fundamental given their healthiness and adaptation in the market. It was also possible to observe the absence of exclusive and scarce studies concerning vegetable beverages by category (soy, oilseeds, cereals, and mainly nuts), to better understand the nutritional peculiarity of each product. Another aspect is the lack of studies among Brazilian consumers. In this respect, in the sense of new research, more work is needed with larger samples of this population, as this was a challenge and a limitation encountered by this study. Despite the country’s large population, economic potential, and global relevance, most studies were carried out in Europe, Asia, and North America and do not reflect the reality and characteristics of other, more diverse nations in the world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Silva, A. R. A.; Silva, M. M. N.; Ribeiro, B. D. Chapter 12 - Plant-Based Milk Products. In Future Foods; Bhat, R., Ed.; Academic Press, 2022; pp. 233–249. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-91001-9.00025-6.

- Nawaz, M. A.; Buckow, R.; Katopo, L.; Stockmann, R. Chapter 6 - Plant-Based Beverages. In Engineering Plant-Based Food Systems; Prakash, S., Bhandari, B. R. Gaiani, C., Eds.; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 99–129. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-89842-3.00015-4.

- Clegg, M. E.; Tarrado Ribes, A.; Reynolds, R.; Kliem, K.; Stergiadis, S. A Comparative Assessment of the Nutritional Composition of Dairy and Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives Available for Sale in the UK and the Implications for consumers’ Dietary Intakes. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110586. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110586.

- Sun, J.; Ortega, D. L.; Lin, W. Food Values Drive Chinese consumers’ Demand for Meat and Milk Substitutes. Appetite. 2023, 181, 106392. DOI: 10.1016/j.appet.2022.106392.

- Vaikma, H.; Kaleda, A.; Rosend, J.; Rosenvald, S. Market Mapping of Plant-Based Milk Alternatives by Using Sensory (RATA) and GC Analysis. Fut. Foods. 2021, 4, 100049. DOI: 10.1016/j.fufo.2021.100049.

- Vallath, A.; Shanmugam, A.; Rawson, A. Prospects of Future Pulse Milk Variants from Other Healthier Pulses - as an Alternative to Soy Milk. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 51–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.tifs.2022.03.028.

- Zeltzer, P.; Moyer, D.; Philibeck, T. Graduate Student Literature Review: Labeling Challenges of Plant-Based Dairy-Like Products for Consumers and Dairy Manufacturers. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105(12), 9488–9495. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2022-21924.

- IBGE - Censo. 2021. IBGE - Censo 2021 https://censo2021.ibge.gov.br/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/29505-expectativa-de-vida-dos-brasileiros-aumenta-3-meses-e-chega-a-76-6-anos-em-2019.html.

- Huang, W.; Dong, A.; Pham, H. T.; Zhou, C.; Huo, Z.; Wätjen, A. P.; Prakash, S.; Bang-Berthelsen, C. H.; Turner, M. S. Evaluation of the Fermentation Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Herbs, Fruits and Vegetables as Starter Cultures in Nut-Based Milk Alternatives. Food Microbiol. 2023, 112, 104243. DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2023.104243.

- Torres, A.; Camillo, G. H.; Lemos Bicas, J.; Maróstica Junior, M. R. Chapter 11 - Nutritional Benefits of Fruit and Vegetable Beverages Obtained by Lactic Acid Fermentation. In Value-Addition in Beverages Through Enzyme Technology; Kuddus, M. Hossain, M., Eds.; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 177–198. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-85683-6.00002-8.

- Jonas da Rocha Esperança, V.; Corrêa de Souza Coelho, C.; Tonon, R.; Torrezan, R.; Freitas-Silva, O. A Review on Plant-Based Tree Nuts Beverages: Technological, Sensory, Nutritional, Health and Microbiological Aspects. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25(1), 2396–2408. DOI: 10.1080/10942912.2022.2134417.

- Scherer, L.; Rueda, O.; Smetana, S. Chapter 14 - Environmental Impacts of Meat and Meat Replacements. In Meat and Meat Replacements; Meiselman, H. L. Manuel Lorenzo, J., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2023; pp. 365–397. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-85838-0.00012-2.

- Silva, B. Q.; Smetana, S. Review on Milk Substitutes from an Environmental and Nutritional Point of View. Appl. Food. Res. 2022, 2(1), 100105. DOI: 10.1016/j.afres.2022.100105.

- Tomar, G. S.; Gundogan, R.; Can Karaca, A.; Nickerson, M. Valorization of Wastes and By-Products of Nuts, Seeds, Cereals and Legumes Processing. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, Academic Press, 2023; DOI: 10.1016/bs.afnr.2023.03.004.

- Schasteen, C. S. Safety of Food and Beverages: Oilseeds, Legumes and Derived Products. In Reference Module in Food Science, Elsevier, 2023; DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-822521-9.00159-3.

- Drigon, V.; Nicolle, L.; Guyomarc’h, F.; Gagnaire, V.; Arvisenet, G. Attitudes and Beliefs of French Consumers Towards Innovative Food Products That Mix Dairy and Plant-Based Components. Int. J. Gastronomy Food Sci. 2023, 32, 100725. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2023.100725.

- Mintel (Org.). (s.d.). Global Food and Drink Trends. 2023.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE EMPRESAS DE PESQUISA; ABEP: São Paulo, 2022. Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil.

- de Alcantara, M.; Ares, G.; de Castro, I. P. L.; Deliza, R. Gain Vs. Loss-Framing for Reducing Sugar Consumption: Insights from a Choice Experiment with Six Product Categories. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109458. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109458.

- Guerrero, L.; Claret, A.; Verbeke, W.; Enderli, G.; Zakowska-Biemans, S.; Vanhonacker, F.; Issanchou, S.; Sajdakowska, M.; Granli, B. S.; Scalvedi, L., et al. Perception of Traditional Food Products in Six European Regions Using Free Word Association. Food Qual. Preference. 2010, 21(2), 225–233.

- Cardello, A. V.; Llobell, F.; Giacalone, D.; Roigard, C. M.; Jaeger, S. R. Plant-Based Alternatives Vs Dairy Milk: Consumer Segments and Their Sensory, Emotional, Cognitive and Situational Use Responses to Tasted Products. Food Qual. Preference. 2022, 100, 104599. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104599.

- Curti, C. A., Lotufo-Haddad A. M., Vinderola G, Ramon A. N., Goldner M. C., Antunes A. E. Satiety and consumers’ Perceptions: What Opinions Do Argentinian and Brazilian People Have About Yogurt Fortified with Dairy and Legume Proteins? J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 8782–8791. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2021-21734.

- Mancini, M. C.; Antonioli, F. Italian Consumers Standing at the Crossroads of Alternative Protein Sources: Cultivated Meat, Insect-Based and Novel Plant-Based Foods. Meat Sci. 2022, 193, 108942. DOI: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2022.108942.

- Acquah, J. B.; Amissah, J. G. N.; Affrifah, N. S.; Wooster, T. J.; Danquah, A. O. Consumer Perceptions of Plant Based Beverages: The Ghanaian Consumer’s Perspective. Fut. Foods. 2023, 7, 100229. DOI: 10.1016/j.fufo.2023.100229.

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W. J. Protein Source Matters: Understanding Consumer Segments with Distinct Preferences for Alternative Proteins. Fut. Foods. 2023, 7, 100220. DOI: 10.1016/j.fufo.2023.100220.

- Collier, E. S.; Harris, K. L.; Bendtsen, M.; Norman, C.; Niimi, J. Just a Matter of Taste? Understanding Rationalizations for Dairy Consumption and Their Associations with Sensory Expectations of Plant-Based Milk Alternatives. Food Qual. Preference. 2023, 104, 104745. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104745.

- de Freitas, Á. C. C., da Costa M. V. G., da Leite M. M., de Oliveira Silva A., Funghetto S. S., Mota M. R., de Lima L. R., Stival M. M. Fatores associados aos hábitos alimentares e ao sedentarismo em idosos com obesidade. Estud. Interdiscip. Envelhec. 2019, 24(3), 81–100. DOI: 10.22456/2316-2171.84300.

- Fisberg, R. M.; Marchioni, D. M. L.; Castro, M. A. D.; Verly Junior, E.; Araújo, M. C.; Bezerra, I. N.; Pereira, R. A.; Sichieri, R. Ingestão inadequada de nutrientes na população de idosos do Brasil: Inquérito Nacional de Alimentação 2008-2009. Rev. Saúde Pública. 2013, 47(suppl 1), 222s–230s. DOI: 10.1590/S0034-89102013000700008.

- Pereira, I. F. D. S.; Vale, D.; Bezerra, M. S.; Lima, K. C. D.; Roncalli, A. G.; Lyra, C. D. O. Padrões alimentares de idosos no Brasil: Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde, 2013. Ciênc. saúde coletiva. 2020, 25(3), 1091–1102. DOI: 10.1590/1413-81232020253.01202018.

- Moss, R.; Barker, S.; Falkeisen, A.; Gorman, M.; Knowles, S.; McSweeney, M. B. An Investigation into Consumer Perception and Attitudes Towards Plant-Based Alternatives to Milk. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111648. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111648.

- Astolfi, M. L.; Marconi, E.; Protano, C.; Canepari, S. Comparative Elemental Analysis of Dairy Milk and Plant-Based Milk Alternatives. Food Control. 2020, 116, 107327. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107327.

- Berardy, A. J.; Rubín-García, M.; Sabaté, J. A Scoping Review of the Environmental Impacts and Nutrient Composition of Plant-Based Milks. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13(6), 2559–2572. DOI: 10.1093/advances/nmac098.

- Moss, R.; LeBlanc, J.; Gorman, M.; Ritchie, C.; Duizer, L.; McSweeney, M. B. A Prospective Review of the Sensory Properties of Plant-Based Dairy and Meat Alternatives with a Focus on Texture. Foods. 2023, 12(8), 1709. DOI: 10.3390/foods12081709.

- Diarra, K.; Nong, Z. G.; Jie, C. Peanut Milk and Peanut Milk Based Products Production: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 45(5), 405–423. DOI: 10.1080/10408390590967685.

- Oduro, A. F.; Saalia, F. K.; Adjei, M. Y. B. Using Relative Preference Mapping (RPM) to Identify Innovative Flavours for 3-Blend Plant-Based Milk Alternatives in Different Test Locations. Food Qual. Preference. 2021, 93, 104271. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104271.

- Waehrens, S. S., Faber, I., Gunn, L., Buldo, P., Bom Frøst, M., Perez-Cueto, F. J. Consumers’ Sensory-Based Cognitions of Currently Available and Ideal Plant-Based Food Alternatives: A Survey in Western, Central and Northern Europe. Food Qual. Preference. 2023, 108, 104875. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2023.104875.

- Silva, A. R. A.; Silva, M. M. N.; Ribeiro, B. D. Health Issues and Technological Aspects of Plant-Based Alternative Milk. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 108972. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108972.

- Lima, D. C.; Noguera, N. H.; Rezende-de-Souza, J. H.; Júnior, S. B. P. What are Brazilian Plant-Based Meat Products Delivering to Consumers? A Look at the Ingredients, Allergens, Label Claims and Nutritional Value. J. Food Compost. Anal. 2023, 121, 105406. DOI: 10.1016/j.jfca.2023.105406.

- Schiano, A. N.; Drake, M. A. Consumer Understanding of Fluid Milk and Cheese Processing and Composition. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104(8), 8644–8660. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2020-20057.

- Bocker, R.; Silva, E. K. Innovative Technologies for Manufacturing Plant-Based Non-Dairy Alternative Milk and Their Impact on Nutritional, Sensory and Safety Aspects. Fut. Foods. 2022, 5, 100098. DOI: 10.1016/j.fufo.2021.100098.

- Cardoso, B. R.; Duarte, G. B. S.; Reis, B. Z.; Cozzolino, S. M. F. Brazil Nuts: Nutritional Composition, Health Benefits and Safety Aspects. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 9–18. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.08.036.

- Jacobs, B. S.; DeJong, T. M. Tree Fruits and Nuts. In Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 303–314. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52512-3.00145-5.

- Rusu, M. E., Simedrea R, Gheldiu A. M, Mocan A, Vlase L, Popa D. S., Ferreira I. C. Benefits of Tree Nut Consumption on Aging and Age-Related Diseases: Mechanisms of Actions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 104–120. DOI: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.03.006.

- McCarthy, K. S.; Parker, M.; Ameerally, A.; Drake, S. L.; Drake, M. A. Drivers of Choice for Fluid Milk versus Plant-Based Alternatives: What are Consumer Perceptions of Fluid Milk? J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100(8), 6125–6138. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2016-12519.

- Calvo, M. S.; Whiting, S. J. Perspective: School Meal Programs Require Higher Vitamin D Fortification Levels in Milk Products and Plant-Based Alternatives—Evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES 2001–2018). Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13(5), 1440–1449. DOI: 10.1093/advances/nmac068.

- Schiano, A. N.; Harwood, W. S.; Gerard, P. D.; Drake, M. A. Consumer Perception of the Sustainability of Dairy Products and Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103(12), 11228–11243. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2020-18406.

- Penha, C. B.; Santos, V. D. P.; Speranza, P.; Kurozawa, L. E. Plant-Based Beverages: Ecofriendly Technologies in the Production Process. Innovative Food Sci. Emerging Technol. 2021, 72, 102760. DOI: 10.1016/j.ifset.2021.102760.

- Barros, M. V.; Salvador, R.; Maciel, A. M.; Ferreira, M. B.; Paula, V. R. D.; de Francisco, A. C.; Rocha, C. H. B.; Piekarski, C. M. An Analysis of Brazilian Raw Cow Milk Production Systems and Environmental Product Declarations of Whole Milk. J. Cleaner Prod. 2022, 367, 133067. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133067.

- Lorente, D.; Duarte Serna, S.; Betoret, E.; Betoret, N. 2 - Opportunities for the Valorization of Waste Generated by the Plant-Based Milk Substitutes Industry. In Advanced Technologies in Wastewater Treatment; Eds. Basile, A., Cassano, A. Conidi, C.; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 25–66. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-88510-2.00004-X.

- Silva Junior, E. C.; Wadt, L. H. O.; Silva, K. E.; Lima, R. M. B.; Batista, K. D.; Guedes, M. C.; Carvalho, G. S.; Carvalho, T. S.; Reis, A. R.; Lopes, G., et al. Natural Variation of Selenium in Brazil Nuts and Soils from the Amazon Region. Chemosphere. 2017, 188, 650–658. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.08.158.

- Baldoni, A. B.; Ribeiro Teodoro, L. P.; Eduardo Teodoro, P.; Tonini, H.; Dessaune Tardin, F.; Alves Botin, A.; Hoogerheide, E. S. S.; de Carvalho Campos Botelho, S.; Lulu, J.; de Farias Neto, A. L., et al. Genetic Diversity of Brazil Nut Tree (Bertholletia Excelsa Bonpl.) in Southern Brazilian Amazon. For. Ecol. Manage. 2020, 458, 117795. DOI: 10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117795.

- Fadimu, G. J.; Olatunde, O. O.; Bandara, N.; Truong, T. Chapter 4 - Reducing Allergenicity in Plant-Based Proteins. In Engineering Plant-Based Food Systems; Prakash, S., Bhandari, B. R. Gaiani, C., Eds.; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 61–77. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-89842-3.00012-9.