Abstract

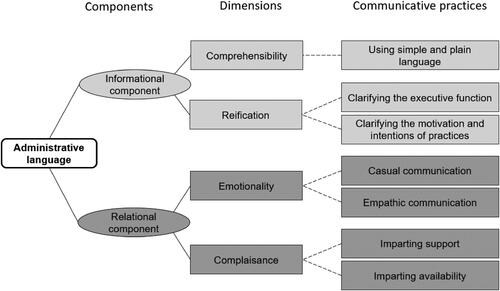

Face-to-face interactions between public officials and citizens are a key venue of state service delivery, but they are rarely studied empirically. To address this gap, we present a novel conceptual taxonomy of spoken administrative language. We combine theoretical insights from communication studies and an analysis of 64 exploratory expert interviews with frontline officials. In these interviews, we asked what officials perceive as those aspects of spoken administrative language that affect citizen (dis-)satisfaction with the encounter. The ensuing taxonomy consists of an informational component with two dimensions: comprehensibility (is the language comprehensible?) and reification (is the regulative context explained?); and a relational component with two dimensions: emotionality (does language convey personal commitment to client concerns?) and complaisance (does language impart support and helpfulness?). With its theoretical and empirical insights, the paper contributes a novel conceptualization of administrative language enabling measurement of spoken communication in public service encounters.

Introduction

Face-to-face interactions between bureaucrats and citizens—so called public service encounters—constitute a defining feature of public service provision. They are among the few instances when citizens and public officials interact in person. And services such as welfare benefits, public health, or education entail significant impact on citizens’ lives or their wellbeing. However, despite some recent advances, studies highlight that we still know relatively little about the dynamics of interpersonal citizen-state interactions (Raaphorst and Loyens Citation2020; Raaphorst, Groeneveld, and Van de Walle Citation2018; Bartels Citation2013). This pertains most notably to the communicative dimension of public service encounters. After all, as Hand and Catlaw (Citation2019, 128) remind us, “[t]he primary way in which encounters are accomplished is through talk, yet this element has been mostly missing in the public administration research.”

Pondering this black box, recent studies have shown that the course and form of spoken conversation is consequential for both how bureaucrats perceive citizens and in what way the subsequent public service is enacted (Bruhn and Ekström Citation2017; Raaphorst, Groeneveld, and Van de Walle Citation2018; Nielsen Citation2007). But there is to our knowledge no distinctive study that seeks to theorize or conceptualize what features of verbal administrative communication are relevant for the perceptions of citizens, such as their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the encounter. Assuming that the way how bureaucrats communicate has an independent effect on citizen perceptions, this study asks about the underlying features of administrative langue. More precisely, in order to develop a taxonomy of administrative language, this study asks what dimensions of bureaucratic communication in a service encounter affect whether citizens gain a positive or negative perception of the encounter.

To develop the taxonomy, we combine top-down theorizing with bottom-up exploratory research. First, we follow existing work in communication studies that distinguishes an informational and a relational component of spoken language (Watzlawick, Bavelas, and Jackson Citation2011 [1967]). These two components pertain to the comprehensibility of the language and the relational meta-message encoded in the choice of terms. Second, to refine these two components with concrete dimensions relevant for the specific context of frontline administrative communication, we conducted 64 exploratory interviews with street-level bureaucrats. In these interviews, we asked officials what aspects of their spoken communication they perceived as relevant for citizen perceptions, such as their (dis-)satisfaction. From the interview data, we then identified categories of broader dimensions and associated communicative practices. The interviews were conducted in the context of a case study on Germany, interviewees were selected to cover geographic regions and types of administrative service domains as comprehensive as possible.

The main finding is a novel taxonomy of administrative language with two components, four dimensions, and seven communicative practices. Accordingly, the informational component further splits into the dimension of comprehensibility (is the content of communication comprehensible?) and reification (does the official explain the regulative context well?). Regarding the relational component, we distinguish the dimension of emotionality (does the bureaucrat express personal engagement with the citizen’s concerns?) from the dimension of complaisance (does administrative language use convey individual citizen support?). For each dimension, the analysis identified concrete communicative practices that could be used to further operationalize and measure administrative language.

With these findings, we propose, as a conceptual contribution, a theoretically and empirically informed taxonomy of administrative language. This taxonomy fills an important gap in the literature as studies on spoken administrative communication are still rare. Our taxonomy enables measurement of communicative practices by the administration. Two specific applications come to mind: First, studies have shown that communication during encounters has an independent effect on service decisions (Nielsen Citation2007; Raaphorst, Groeneveld, and Van de Walle Citation2018; Raaphorst and Loyens Citation2020), but we do not yet know what linguistic elements trigger such dynamics. Second, we know that administrative action is often subject to (unconscious) biases (Keiser et al. Citation2002; Jilke and Tummers Citation2018; Naff and Capers Citation2014; Meier Citation1993), but we lack detailed insights how such biases play out in communication and how they systematically influence citizen perceptions of the encounter (de Boer, Citation2020; Nielsen, Nielsen, and Bisgaard Citation2021). Our study thus opens the door toward new insights on social equity in the distribution of public service (Blessett et al. Citation2019; Cepiku and Mastrodascio Citation2021).

The paper is structured as follows: A literature review serves to situate our work in public administration literature. Drawing on communication studies, we then derive the basic classification of informational and relational linguistic components. We next explain our empirical strategy to complement these two components of language with concrete insights from the field of public service encounters. Thereafter, we introduce the resulting taxonomy of administrative language and discuss the limitations of our empirical work. This is followed by a brief conclusion on implications of our work.

Pondering the black box of spoken language in public service encounters

The quality of modern democratic rule hinges substantially on actions and decisions taken at the “ground floor of government” where state and society directly meet (Hupe Citation2019:7) and officials create values for the people (Moore Citation1995). Here, administrative action performed by so-called street-level bureaucrats “could hardly be farther from the bureaucratic ideal” that perceives policy implementation mostly as a technocratic process (Lipsky Citation[1980] 2010:9). While frontline workers apply service policies “case by case and client by client”, they inevitably hold discretion to decide about whether and how services are granted to citizens (Maynard-Moody and Musheno Citation2000:338). By becoming personally familiar with the individual situation of their clients, frontline officials can make discretionary judgements in line with both sides of the “fairness equation” (Raaphorst Citation2021:10): Treating all citizens equally while simultaneously responding to individual concerns and hardship (Zacka Citation2019:454).

Apart from this, the way how public service encounters proceed has a strong impact on the long-term relationship between the state and its citizens. These face-to-face interactions pertain to the seldom occasions where citizens personally meet “public officials of flesh and blood” (Jansson and Erlingsson Citation2014:294). Hence, it is not surprising at all that contact with agencies on an aggregated level effectively shapes confidence in public institutions since these are the most vital and direct experiences one can make with governing authorities (Hansen Citation2021; Kampen, Van De Walle, and Bouckaert Citation2006; Rothstein Citation2009; Yackee and Lowery Citation2005). Moreover, literature on trust and social capital highlights the importance of citizen-state encounters for creating and maintaining social cohesion among fellow citizens (Andreotti, Mingione, and Polizzi Citation2012; Purcell Citation2006; Rothstein and Stolle Citation2008; Kumlin and Rothstein Citation2005).

Spoken communication is a key feature of service encounters.Footnote1 Ethnomethodological studies and narrative insights illustrate how the final results of service delivery materialize through and during interpersonal citizen-state interactions (Bartels Citation2013, Citation2015; Bruhn and Ekström Citation2017; Hand and Catlaw Citation2019; Picciotto Citation2007; Raaphorst and Loyens Citation2020). Here, authors contend that the meaning and the application of laws and bureaucratic rules are incrementally “invoked and negotiated through interactional practices” between frontline officials and their clients (Bruhn and Ekström Citation2017:211). Following-up on these insights, Nielsen (Citation2007) and Raaphorst and colleagues (Citation2018) found that the more consensual and direct the communication is, the more favorable the administrative outcome for citizens.

Despite such findings, the literature has not yet sought to explore in more detail the linguistic features of spoken administrative language. Focusing mostly on the consequences of communication for bureaucratic judgements and decisions, extant studies have been less concerned about the distinct communication styles frontline bureaucrats rely on and how they are perceived by citizens. We thus know little about those aspects of bureaucratic communication reflecting a citizen orientation of the administration that is appropriate for the democratic state. This assumes that there are certain communicative practices that are consequential for citizen perceptions, in particular for citizen satisfaction or dissatisfaction with public services, and that influence trust in public institutions.

The informational and relational component of spoken (administrative) language

The goal of this article is to develop a taxonomy of administrative language that is relevant for citizen perceptions. In this context, the term administrative language does not only capture a specific syntax or semantics. Instead, we understand it as the specific practices of verbal interpersonal communication bureaucrats rely on when they speak with citizens. Accordingly, administrative language may exhibit and vary along certain patterns of wording or structure. Beyond that, our definition includes also the specific content of speech acts, the way how public servants respond to the communicative input of citizens (giving them space to tell their story or not) and how they verbally relate to the individual circumstances of their clients.

With citizen perceptions we mean the extent to which administrative language is positively or negatively perceived by citizens and thus contributes to their overall satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the encounter. Similar to a teacher who explains a complex issue with simple terms and vivid examples, treats students in a respectful manner, and is thus more positively evaluated than her colleagues, we expect that there are certain styles of administrative communication that lead to a more positive citizen evaluation—independent from the content and outcome of service delivery.

As a first step toward identifying communicative practices associated to administrative language, we follow established work by Watzlawick, Bavelas, and Jackson (Citation2018 [1967]), who distinguish an informational an a relational component of communication. Already in the 1960s, they showed that human language varies in terms of the information it conveys (such as comprehensibility) and the relational message it encodes (such as hierarchy between sender and recipient). They further stressed that the relational aspect classifies, i.e., subsumes, the informational level: “[E]very communication has a content aspect and a relationship aspect such that the latter classifies the former and is therefore metacommunication” (54). Human communication thus contains a content message and a relational component that influences how the conveyed content is interpreted in terms of relational elements such as hierarchy and power (81). Such meta-communication may emerge through direct verbal statements, but also through indirect nonverbal communication and the contextual setting.

The informational component of communication is clearly relevant to encounters between public officials and citizens. Citizens’ initial and primary reason to encounter the state is oftentimes demand for information: They are in need of a state service and require information on the service process and decision, such as what forms and supportive documents they need to submit to clarify their eligibility. Since these processes usually occur rarely in one’s life, citizens are generally bureaucratically illiterate. It is, therefore, one of the responsibilities of the public service administrators to provide sufficient and transparent information to help citizens to navigate the process to access a public service. Thereby, communication scholars have emphasized the importance of vagueness and ambiguity in terminology (Goss Citation1972; Ravin and Leacock Citation2000). As a starting point for developing a taxonomy of administrative language, we thus note as a first component the importance of information provision through comprehensible and precise language.

The relational component too appears highly relevant in the context of service encounters. One communicative feature studies frequently mention is the expression of hierarchy (Burgoon and Hale Citation1984, Citation1987). Indeed, public servants do not only have the full decision-making competence, i.e., to determine whether a service is granted or not, but they additionally represent the governing state authority. In their verbal communication, they may either emphasize or downplay this hierarchical relationship. This is also in line with Dillard, Solomon, and Palmer (Citation1999) framing theory that distinguishes inter alia between the dominance-submission dimension. Scholars have also argued that communication can differ in terms of the formality and task-orientation of the verbal speech act: For instance, “highly formal demeanour in an otherwise informal setting can be a very powerful message, as can insistence on sticking to the task at hand in response to social overtures” (Burgoon and Hale Citation1984:211). In public encounters, a mismatch between the context of the encounter and the formality of the communication may prevail, such as a highly formal communication style while a client faces existential hardship.

As can be seen, both these components of communication are highly relevant for administrative communication. But they require further specification and detail to fit the context of public service encounters. We therefore outline next an empirical strategy to specify such a taxonomy of administrative language by taking into consideration the perspectives of practitioners. More precisely, we report how we proceeded to perform a bottom-up, inductive conceptualization of each of the two components of communication introduced above. It is important to emphasize that we focus exclusively on verbal communication. Although we explicitly acknowledge the possibility that non-verbal communication may also be relevant, this is beyond the scope of this study.

Research design and methodology

To further specify the taxonomy of administrative language we realized an exploratory single-case study with a focus on local public service delivery in Germany (Gerring Citation2004; Welch et al. Citation2011). We chose Germany for practical reasons as researchers based at German academic institutions. But the German administrative system also shows comparatively high levels of citizen-orientation at the frontline (Grohs Citation2021; Huxley et al. Citation2016; Kuhlmann and Wollmann Citation2019), which implies that we are looking at a case where professional training and reflection regarding communication with citizens may be more pronounced than elsewhere.Footnote2 Meanwhile, the focus on only one country requires critical reflections on the applicability of our findings to other national administrative traditions which we discuss in more detail below.

Building on the two theoretically identified components of administrative language, the aim of the case study was to identify dimensions of administrative language that are influential when it comes to the perceptions of citizen clients, in particular their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the encounter. Instead of citizens, however, we collect empirical data among frontline workers. Indeed, citizens need to deal with public authorities in various life situations so that many have extensive experiences in communicating with public servants. Yet, these experiences are inevitably episodic and remain limited to their personal situation, while (street-level) bureaucrats encounter a wide range of citizens on a daily basis. For our exploratory purpose, data collection among frontline workers therefore appeared more promising to indirectly gain profound insights into the daily reality of bureaucrat-client communication (Bogner, Littig, and Menz Citation2018; Bogner and Menz Citation2009; Meuser and Nagel Citation2009).

To identify common themes while avoid falling for idiosyncrasies linked to the individual respondent (experience, training, attitudes) or a particular service domain, data was collected from multiple interviewees. Study participants were recruited by sending out email requests to local administrations in a broad variety of service domains, policy contexts and regions all across Germany (see Appendix 2 for a detailed overview on the distribution).Footnote3 The final sample included officials from local social service offices (Sozialämter), jobcentres (Jobcenter), migration offices (Ausländerbehörden/Integrationsbüros), citizen offices (Bürgerämter/Bürgerbüros),Footnote4 environment offices (Bau- und Umweltbehörden) and staff units dealing with internal and external communication (usually equal opportunity and diversity management offices as well as unites charged with processing citizen complaints). Requests were sent out in several waves until the authors established that a point of saturation (Saunders et al. Citation2018) had been reached where additional interviews did not bring novel insights. Overall, the final simple includes 64 interviews (see Appendix 1 for a full list of interviews).Footnote5

Interviews followed a semi-structured interview questionnaire that was designed “to facilitate the telling of the story” along a predefined structure (Brinkmann Citation2018:1002; see also, Bogner and Menz Citation2009; Honer Citation1994). The main objective was to identify those aspects of frontline communication that officials had experienced to cause positive or negative reactions among citizens. However, to obtain authentic insights, we did not ask directly about these cues, but rather encouraged respondents to report in their own words on experiences on communicative practices. In the course of the data collection procedure, later interviews included more specific and validating questions (for the interview guideline, see Appendix 3).Footnote6 All interviews were performed one-on-one by two interviewers, both of them coauthors of this article, between May and December 2020. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic at the time, interviews were carried out over the phone or via video call, each of them ranging between 30 and 90 minutes. Most interviews were transcribed; for some of the later ones we only took notes.

The data obtained from our exploratory interviews describes the social reality of communicative practices as perceived by frontline workers in German local public administrations. These rich narrative accounts differed in detail and wording and the objective was to identify stable and recurring patterns. Thereby, the starting point of the analysis was deductive as we treated the informational and the relational components of language as given (but note that we never mentioned those in the interviews). However, identifying concrete communicative practices took place inductively. For the coding, each interviewer identified and labeled relevant communicative practices from each interview after it was conducted. These aspects were then subsumed to either component of language and grouped into dimensions. The dimensions and practices were further validated and refined by carefully confronting subsequent interview participants with previous insights. All of these steps implied consistent exchange and discussions among the authors to finally arrive at a common interpretation that would appropriately reflect all the data that were collected.

Findings: A taxonomy of administrative language

illustrates the resulting taxonomy of administrative language. At the most abstract level, the taxonomy consists of the informational and relational component identified from the literature on communication. Building on the interview data, we further subsume two dimensions under the informational component, namely comprehensibility and reification. Likewise, we distinguish emotionality and complaisance as part of the relational component. These four dimensions offer a comprehensive understanding of how we found frontline communication to vary in a way that officials think is relevant for citizen satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Within the four dimensions, we further identify seven communicative practices. These are linguistic elements of communication at the level of terminology or choice of words that indicate the presence of a dimension.

In the following, we present the four dimensions of the taxonomy in detail. Thereby, we report exemplifying passages and direct quotes from the interviewees to reveal how our interpretation links with the interview data.Footnote7 Doing so, we sought to establish direct linkages between frontline communication and citizen perceptions as far as the experiences reported by the interviewed bureaucrats allow us to do so. Where available, we report “smoking-gun” instances (Collier Citation2011:825) as illustrative examples.

The informational component of administrative language

Comprehensibility

Effective communication is subject to many pitfalls. Misunderstandings occur if interactions do not convey the intended message of the sender to the recipient. A lack of clarity may result in particularly far-reaching consequences. Thus, communication between two individuals is by its character a process that requires precision (Grant Citation1996). Whereas public servants deal with bureaucratic procedures on a daily basis and are trained to interpret official (legal) language, regular citizens generally face a double disadvantage: they neither know the relevant laws nor can they interpret them. To balance out such “expert-layperson communication” (Lewalter, Geyer, and Neubauer Citation2014:161) in public service encounters, bureaucrats need to make interactions as understandable as possible, which means paraphrasing and translating complicated matters into comprehensible information.

According to the interviewees, the best way to establish comprehensibility and depict bureaucratic manners in a penetrable fashion is by using plain and clear language. This refers not only to using very simple sentence structures and few adjectives (ID: 47), but also to avoiding technical and legal terms, essentially acknowledging the fact that the abbreviations, the paragraphs […] are incomprehensible for the ordinary citizen (ID: 62). One social service office employee emphasized:

The simpler you keep the language and the clearer or more explicit you tell them, the easier it is for people to understand. We have almost completely moved away from the earlier officialese” (ID: 41).

If someone seems educated to me, I express myself differently […]. We also have a lot of people with migration backgrounds here that sometimes do not speak German very well. Then, I try to speak in such a way that they understand me” (ID: 41).

Overall, interviewees consistently emphasized comprehensibility in administrative language as a basic prerequisite for successful communication in public service encounters, measured against a general understanding that comprehensibility improves citizen perceptions. Comprehensibility, in the sense of simple and plain language, therefore, makes up the first dimension of the taxonomy.

Reification

Building on the first dimension, the second dimension of reification further emphasizes a specific informational need of citizens in public service encounters. Besides using simple and plain language to make oneself comprehensible, officials consistently emphasized the importance of establishing transparency regarding the decision-making processes and service procedures. This is also a general finding in research on the acceptance of authoritative decisions, where studies report increased acceptance as transparency about the decision process and criteria increase (Weisberg et al. Citation2018; Einsiedel Citation2000). Based on our own findings from the interviews, we postulate that merely announcing a final outcome should lead to a decrease in citizens’ acceptance. As one migration office employee said, it gets you into hell’s kitchen (ID: 62) if as an official you do not clarify why a decision was made in a particular situation. According to her, explaining is the crux of the matter (ID: 62).

Based thereupon, we identify two more concrete communicative practices that many officials reported upon: The first communicative practice is to clarify the executive function. This acknowledges that front-line officials represent the state and, thus, personify the legal norms. Intuitively, citizens equate employees with the decision-making procedures, i.e., citizens do not perceive public officials as executing actors who enact legal procedures or the law, but perceive them as individuals who make their own (arbitrary) decisions. When this occurs, externalizing responsibility appears as a suitable coping mechanism. One jobcentre employee provides a vivid example for this as he noted the following:

[The citizens get upset] because they see me as a person, because I am the one who decided that they get less money. But that’s not me. I am just the one who has to implement it because all the conditions have been met for these sanctions. And then I tell them, I am sorry, this is the legal rule and I have to do this now (ID: 52).

Overall, these examples show that from the perspective of public officials, citizens feature higher acceptance rates in public service encounters when the street-level bureaucrat clarifies not only her or his executive function but also the motivation and intention of the executed rule or legal practice. In combination with the use of comprehensible language, citizens obtain the information needed to develop their own understanding of why and how a decision comes to be.

The relational component of administrative language

Emotionality

A third consistently mentioned narrative across interviews is about establishing a sense of emotional commitment to the concern of the citizen client. With that, we do not mean the actual emotional reaction by frontline workers, but a conscious cognitive reaction to the situation at hand and how it manifests in communicative terms. From the perception of interviewees, establishing such an emotional response was associated with more successful and appreciative interactions. The relevance of emotionality is also emphasized in a range of studies on emotional labor in public administration. Hochschild (Citation1983) early on argued that some occupational groups are required to actively manage their emotional expressions as part of the job. In public administration, such emotional labor seems to be relevant particularly when it comes to service encounters (Guy, Newman, and Mastracci Citation2014). In these encounters, emotional language may generate behavioral and attributional responses, and thus influence the conversational content as well as its perception (Metts and Planalp Citation2003).

From the interviews, we identify casual communication as a first communicative practice associated to emotionality. Frontline workers consistently reported that they consciously seek to endow citizen conversations with a personal touch to create a relaxed atmosphere or to moderate conflict, e.g., in a tense situation when a service is of existential relevance for the citizen. Accordingly, citizens seem to perceive personal and less formal behavior as a public servants’ commitment to their individual case and that the official’s engagement goes beyond her duties. Including elements of small talk in the conversations is, therefore, unanimously reported as helpful:

The best way of communication is […] to chit chat a little bit. You ask for the family. You ask general things. You talk about the weather for a moment” (ID: 30).

The second emotional communicative practice is empathic communication. Most frontline workers reported that expressing empathy is vital to demonstrate understanding for the distinct situation of their clients. How broadly or how narrowly this characteristic is defined varies: Some officials try to be empathetic by encouraging citizens to pour their whole heart out (ID: 5). The public servants note that their clients often do not have anyone to talk to, making the frontline worker walk between telephone counselling and crisis service, in one person (ID: 37). Although, it may be difficult to always communicate empathetically, when being responsible for more than 100 or 200 clients, some employees view empathy as a basic requirement to help their clients, as one job center employee remarks:

If you seriously want to meet someone empathetically, you need to listen to the concerns and needs of your clients. I do not think you can make any progress otherwise. Clients then also feel misunderstood and will not say anything again the next time. Usually there is a deep-seated problem and I rather go deeper into the conversation and let the client talk about this topic extensively than skip it (ID: 37).

I can understand that a citizen is […] angry, when another citizen wastes more heat and has high expenses for his water consumption, and this is paid by our office. Then I can understand the citizens. And then it is reasonable to show them that you understand their situation” (ID: 34).

Complaisance

In addition to emotionality, another relational dimension induced from the interviews was about signaling support and availability to citizen clients, what we sought to capture with the term complaisance.Footnote8 This is also an issue we find mentioned in the literature on street-level bureaucracy. Citizens often have difficulties anticipating whether public servants will be sympathetic and benevolent, or whether they will enact penalties (Boer Citation2020; Kumlin and Rothstein Citation2005; Rothstein and Stolle Citation2008; Jensen Citation2018). Therefore, as for instance de Boer (Citation2020) states, without personally encountering bureaucrats, citizens assess officials based on stereotypical images where they match them to one of these two action orientations. To convey complaisance at a communicative level, we identified two practices from the interviews: One is to actively impart the supportive nature of state action in dissociation from its restrictive side; the other to impart availability toward their clients.

The first communicative practice, imparting support, captures the practice of directly responding to citizens who are anxious and insecure about encountering a state institution by offering support. Especially when it comes to groups with less societal power, as officials said, citizens often hesitate and say Oh, I do not dare go there (ID: 51). A social service office bureaucrat expressed a similar observation:

I have noticed that some citizens are quite resigned. […]. They are afraid to call somewhere for fear of not getting a satisfactory answer. I think that citizens still have a strong fear of contact with the authorities. They say, ‘Oh, that will not do any good anyway’ or ‘That takes too long for me.’ Particularly, the elderly often forgo contact because they say they cannot get their way there, because they are worried, they will not be treated well (ID: 41).

The second communicative practice signaling complaisance—imparting availability—captures that some officials sought to aspire accessibility in contrast to not being visible for their client, like an ‘open door policy’. They argued that accessible public officials are usually perceived as less authoritative by the citizen. As one social service office employee puts it, it seems important for citizens to have a direct contact person who is tangible […] and available (ID: 34). Another social service office employee told us that instead of responding in a formal way when he receives an email with a request or a complaint, she often suggests a personal meeting or phone call to to clear the situation (ID: 33). By doing this the citizen has the possibility to explain herself and gets the feeling (s)he is being listened to (ID: 33). Another public servant reported a similar dynamic from her experience:

I am surprised time and again that when I get an angry e-mail or an angry letter or an angry entry in our online portal, that when I directly contact that person, whether I call them or offer an appointment, a totally different personality appears in front of me (ID: 12).

Discussion of results

Despite our best efforts to develop a taxonomy that is valid for a broad range of encounters and across geographic areas and policy fields, there are some limitations linked to the research design and analysis that may limit generalization. To begin with, we collected data only from the case of Germany, which highlights the need for further external validation in other countries and cultures. As discussed above, German administration exhibit comparatively high levels of citizen-orientation which raises the question how well our framework applies to states with other administrative traditions. In the same vein, the normative baseline of public value and citizen orientation in public administration arguably limits the applicability of the taxonomy to democratic countries where the public service aspires to serve the people (rather than the ruler).

Further, the taxonomy does not systematically account for differences in public service domains. Although we collected interview data from as many service areas as feasible, it might still be that further consideration of idiosyncrasies of different service domains or agencies could lead to a more nuanced or refined taxonomy. First instance, communication may differ according to an agency’s core task which can be either oriented toward service or regulative functions, such as welfare services versus policing tasks (Jensen Citation2018). Moreover, the significance of the service for citizens may make a difference. For example, the provision of unemployment benefits or accommodation allowances might call for personal and emotional communication, whereas in case of less existential services (such as passport or residence registration matters), citizens might especially value understandable and plain language to keep the encounter as simple and fast as possible. Last, varying degrees of bureaucratic discretion may also play a role for the communication style, as a recent study in a related context suggests (Thunman, Ekström, and Bruhn Citation2020).

We aimed to develop a taxonomy that captures variation in communicative practices reported by frontline officials. However, some of them also seem to have resource implications, such as time requirements of the public servant. For example, reification could imply lengthier elaborations. And complaisance implies the idea of an open door and signaling of further assistance, which of course is only possible if public officials have associated time resources. Such resource implications may consequently pose restrictions in the extent to which officials can actually choose to communicate along the full range of the taxonomy.

As another limitation, we noted from our interviews that there is no one-size-fits-all approach in communicative encounters. In this vein, the employee of an environment office quite aptly concluded that “you need to touch upon the language of the people” which is” by all means diverse” (ID: 14). As an example, frontline workers seem to sense that “administrative language is a generational issue” (ID: 9) implying that they have experienced that older clients prefer a more formal communication style, whereas younger clients prefer more informal choice of words. Likewise, some interviewees had gained the impression form their daily encounters that highly educated clients might prefer more precise language whereas clients with language deficits require or prefer that public servants “explain a bit more” (ID: 23). This implies that communicative encounters may entail even more variation within each dimension of the taxonomy, such as different terminology to achieve casual or empathic communication.

Another point is that the analysis does not explicitly address the relationship of the taxonomy elements to each other. However, in the everyday reality of public service encounters the four dimensions are not necessarily independent from one another. For instance, it is implausible to assume that an official imparting support and availability in his or her communication is not also empathic. Apart from this, the broader informational and relational elements might also relate to each other. As an example, a speech act that a citizen does not well understand, i.e. that exhibits low values on the informational dimensions, is also not well suited to deemphasize the hierarchical relationship between the bureaucrat and his client which means it will have low values in terms of relational elements as well. Since we were primarily interested in exploring the various dimensions and communicative practices of administrative language, further empirical research is needed to detect how the dimensions interact in practice.

Lastly, it is worthwhile stressing again that the empirical insights sustaining our findings so far rely exclusively on the perspective of public servants. While this is a valid and valuable perspective on its own right, since it tells what officials think is relevant to their communication, we still need to cross reference the taxonomy with an original citizen perspective. For example, interviews with citizens could serve to validate the dimensions of the taxonomy, and communication data from encounters or laboratory experiments could be used scrutinize the consequentiality of the taxonomy for citizen perceptions.

Conclusion and implications

In this article, we aimed to develop a taxonomy of administrative language. This endeavor was inspired by the objective to identify dimensions of administrative language that affect citizen perceptions, irrespective of the actual service decision. In other words, we sought to identify those dimensions of administrative language that should have an independent causal impact on citizen perceptions. To get there, we first drew on communication studies to identify two linguistic components of language; an informational component and a relational meta-level. To identify how each component manifests in the reality of verbal communication during service encounters, we second conducted and analyzed 64 expert interviews. From these we identified four dimensions and seven associated communicative practices that—as seen by our interview partners—should influence how positively or negatively citizens perceive the encounter.

Despite some limitations as discussed above, which partially highlight trajectories for future research, our findings make a relevant contribution to research on public administration and street-level bureaucracy. Although studies recognize the black box of service encounters between citizens and public officials, in particular regarding their communicative dimension, only few studies offer empirical insights (Bartels Citation2015; Bruhn and Ekström Citation2017; Hand and Catlaw Citation2019; Raaphorst and Loyens Citation2020). We contribute to this literature with the development of a taxonomy of administrative language. This taxonomy captures linguistic elements of administrative communication that influence citizen perceptions (satisfaction/dissatisfaction) independent of the actual service context and decision. Based on the instructions for operationalization that come with our taxonomy, it is possible to scrutinize this expectation as a valuable next step.

Most importantly, our work opens the door toward new insights on social equity in the distribution of public service (Blessett et al. Citation2019; Cepiku and Mastrodascio Citation2021). Similar to incomprehensible application forms or complex procedures, spoken administrative language can constitute a barrier for some citizens to access public services (see the work on administrative burden, cf. Herd and Moynihan [Citation2019]). One resulting question thus is whether officials apply a customized language depending on the client’s background or whether they use the same language in all public service encounters. On the one hand, equal treatment of citizens would imply to use a standardized language to provide equal resources to all citizens. On the other hand, an equity perspective implies a distribution of resources according to needs, that is, tailoring communication to the individual situation of the citizen.

Responding to the situation at hand implies that officials adjust their communication to the background and needs of the citizen. Indeed, street-level bureaucracy literature suggests that many officials most deeply adapt to the individual cases of citizens by basing “their decisions on their judgment of the worth of the individual citizen client” (Maynard-Moody and Musheno Citation2000:329). And also, in our own research, we found that officials seem to intuitively tailor their language use to specific citizen needs to provide equal access. One may conclude from some of the interviewees’ explanations, for instance, that an older, educated woman may be likely to assign a lot of value on formal communication appropriate to her level of education, but may not have a similarly strong need for empathic communication. A single father whose livelihood depends on a particular service may, however, appreciate empathy, whereas his need for formal language may be less pronounced.

In the welfare state, public service delivery is typically designed in a way that mitigates the impact of skewed income distributions, by making essential goods, such as education or public infrastructure, available for the poor or socially weak who could otherwise not afford them. It would be highly problematic, if bureaucratic stereotypes and other forms of implicit biases lead to an ill-suited tailoring of bureaucratic communication, potential repelling clients rather than improving access. Our taxonomy now offers a way to study such tailoring empirically, to explore whether such a ‘language of the people’ exists and how it differs for specific clients or depending on the match between demographic characteristics of both officials and clients which is what representative bureaucracy theory would suggest (Kingsley Citation1944; Meier Citation1993).

Our findings may also contribute to two other strands of research in public administration. On the one hand, several recent studies began assessing citizen perceptions of public service encounters (de Boer Citation2020; Nielsen, Nielsen, and Bisgaard Citation2021; Hansen Citation2021). On the other hand, studies have also begun scrutinizing how variation in communication during service encounters leads to different service decisions (Nielsen Citation2007; Raaphorst, Groeneveld, and Van de Walle Citation2018; Raaphorst and Loyens Citation2020). With our taxonomy, we pave the way for conducting more precise empirical research on variation in communication during these encounters, and how communicative practices are thus associated with discrimination, stereotyping and unequal citizen treatment (Jilke and Tummers Citation2018; Keiser et al. Citation2002; Naff and Capers Citation2014).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (210.9 KB)Notes

1 The same goes for written communication, which has been of interest to the field of public administration for some time already (Fluck Citation2010; Fisch and Margies Citation2014; Sarangi and Slembrouck Citation2014).

2 In light of this, one might label Germany as “outcome case” with high values on the dependent variable recommended to rely on in exploratory inquiries (Gerring and Cojocaru Citation2016, p. 398).

3 Due to the specifics of the German federalism the organization of public services and the underlying bureaucratic structures in local administrations noticeably vary all over Germany (Dose Citation2019; Behnke and Kropp Citation2021). In case service provision is based on federal legislation the states and the local administrations are usually provided with extensive leeway during the implementation to align service delivery with regional characteristics. Furthermore, local administrations also provide services on their own which may be highly idiosyncratic. Apart from this, in rural areas, local administrations are usually two-tier consisting of counties (Landkreise) and small cities (kreisangehörige Gemeinden). Whereas, in urban areas, only county-free cities (kreisfreie Städte) constitute the local level. The states thereby have the authority to determine how the local administrations are structured within their jurisdiction which is why local administrative structures further vary systematically with regard to the state where they are located.

4 These local agencies are one-stop shops for the services most frequently deployed by all citizens such as passport and registration matters (Kuhlmann and Bogumil Citation2021).

5 Interviews were anonymized to avoid bias in the interview data due to interviewees feeling intimidated when speaking ‘on the record’.

6 The predefinition of the interview guideline was collaborative work all authors were engaged in.

7 The quotes were translated by the authors. Every quote will be marked with the concerning ID of an interviewee. The IDs are equally indicated in the interview list in Appendix 1 so that the quotes can be linked with the occupation and location of the interviewee. Furthermore, Appendix 4 includes direct quotes as additional examples from the interviews.

8 Complaisance is understood as a “deference to the wishes of others” https://www.collinsdictionary.com/de/worterbuch/englisch/complaisance.

References

- Andreotti, A., E. Mingione, and E. Polizzi. 2012. “Local Welfare Systems: A Challenge for Social Cohesion.” Urban Studies 49(9):1925–40. doi: 10.1177/0042098012444884.

- Bartels, K. P. 2013. “Public Encounters: The History and Future of Face-to-Face Contact between Public Professionals and Citizens.” Public Administration 91(2):469–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2012.02101.x.

- Bartels, K. P. 2015. Communicative Capacity: Public Encounters in Participatory Theory and Practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Behnke, N, and S. Kropp. 2021. “Administrative Federalism.” Pp. 35–51 in Public Administration in Germany, edited by S. Kuhlmann, I. Proeller, D. Schimanke, & J. Ziekow. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Blessett, B., J. Dodge, B. Edmond, H. T. Goerdel, S. T. Gooden, A. M. Headley, … B. N. Williams. 2019. “Social Equity in Public Administration: A Call to Action.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 2(4):283–99.

- Boer, Noortje. 2020. “How Do Citizens Assess Street‐Level Bureaucrats Warmth and Competence? A Typology and Test.” Public Administration Review 80(4):532–42. doi: 10.1111/puar.13217.

- Bogner, A. B. Littig, and W. Menz. 2018. “Generating Qualitative Data with Experts and Elites.” Pp. 652–67 in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection, edited by U. Flick. London: SAGE Publications.

- Bogner, A, and W. Menz. 2009. “The Theory-Generating Expert Interview: epistemological Interest, Forms of Knowledge, Interaction.” Pp. 43–80 in Interviewing Experts, edited by A. Bogner, B. Littig, & W. Menon. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brinkmann, S. 2018. “The Interview.” Pp. 576–99 in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln. London: Sage Publications.

- Bruhn, A., and M. Ekström. 2017. “Towards a Multi‐Level Approach on Frontline Interactions in the Public Sector: Institutional Transformations and the Dynamics of Real‐Time Interactions.” Social Policy & Administration 51(1):195–215. doi: 10.1111/spol.12193.

- Burgoon, J. K., and J. L. Hale. 1984. “The Fundamental Topoi of Relational Communication.” Communication Monographs 51(3):193–214. doi: 10.1080/03637758409390195.

- Burgoon, J. K., and J. L. Hale. 1987. “Validation and Measurement of the Fundamental Themes of Relational Communication.” Communication Monographs 54(1):19–41. doi: 10.1080/03637758709390214.

- Cepiku, D., and M. Mastrodascio. 2021. “Equity in Public Services: A Systematic Literature Review.” Public Administration Review 81(6):1019–32. doi: 10.1111/puar.13402.

- Collier, D. 2011. “Understanding Process Tracing.” PS: Political Science & Politics 44(4):823–30. doi: 10.1017/S1049096511001429.

- Dillard, J. P., D. H. Solomon, and M. T. Palmer. 1999. “Structuring the Concept of Relational Communication.” Communication Monographs 66(1):49–65. doi: 10.1080/03637759909376462.

- Dose, N. 2019. “Cooperative Administration in Multilevel Governance Analysis: Incorporating Governance Mechanisms into the Concept.” Pp. 79–96 in Configurations, Dynamics and Mechanisms of Multilevel Governance, edited by N. Behnke, J. Broschek, & J. Sonnicksen. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Einsiedel, E. F. 2000. “Understanding ‘Publics’ in the Public Understanding of Science.” Pp. 205–16 in Between Understanding and Trust: The Public, Science and Technology, edited by Dierkes Grote. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- Fisch, R, and B. Margies. 2014. “Einfluss Der Verwaltungskultur Auf Die Sprache Der Legalistischen Verwaltung.” Pp. 67–79 in Grundmuster Der Verwaltungskultur: Interdisziplinäre Diskurse Über Kulturelle Grundformen Der Öffentlichen Verwaltung, edited by K. König, S. Kropp, S. Kuhlmann, C. Reichard, K.-P. Sommermann, & J. Ziekow. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Fluck, H.-R. 2010. Amtsdeutsch a. D.? Europäische Wege zu Einer Modernen Verwaltungssprache. Tübingen: Stauffenburg-Verlag.

- Gerring, J. 2004. “What is a Case Study and What is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98(2):341–54. doi: 10.1017/S0003055404001182.

- Gerring, J., and L. Cojocaru. 2016. “Selecting Cases for Intensive Analysis: A Diversity of Goals and Methods.” Sociological Methods & Research 45(3):392–423. doi: 10.1177/0049124116631692.

- Goss, B. 1972. “The Effect of Sentence Context on Associations to Ambiguous, Vague, and Clear Nouns.” Speech Monographs 39(4):286–9. doi: 10.1080/03637757209375767.

- Grant, R. M. 1996. “Prospering in Dynamically-Competitive Environments: Organizational Capability as Knowledge Integration.” Organization Science 7(4):375–87. doi: 10.1287/orsc.7.4.375.

- Grohs, S. 2021. “Participatory Administration and Co-Production.”Pp. 311–27 in Public Administration in Germany, edited by S. Kuhlmann, I. Proeller, D. Schimanke, & J. Ziekow. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Guy, M. E. M. A. Newman, and S. H. Mastracci. 2014. Emotional Labor: Putting the Service in Public Service. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hand, L. C., and T. J. Catlaw. 2019. “Accomplishing the Public Encounter: A Case for Ethnomethodology in Public Administration Research.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 2(2):125–37. doi: 10.1093/ppmgov/gvz004.

- Hansen, F. G. 2021. “How Impressions of Public Employees’ Warmth and Competence Influence Trust in Government.” International Public Management Journal 1–23. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2021.1963361.

- Herd, P, and D. P. Moynihan. 2019. Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Hochschild, A. R. 1983. The Managed Heart: commercialization of Human Feeling (2. print. ed.). Berkeley, California: University of California Pr.

- Honer, A. 1994. “Das Explorative Interview: zur Rekonstruktion Der Relevanzen Von Expertinnen Und Anderen Leuten.” Schweizerische Zeitschrift Für Soziologie 20(3):623–40.

- Hupe, P. 2019. “Contextualizing Government-in-Action.” Pp. 2–14 in Research Handbook on Street-Level Bureaucracy, edited by P. Hupe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Huxley, K., R. Andrews, J. Downe, and V. Guarneros-Meza. 2016. “Administrative Traditions and Citizen Participation in Public Policy: A Comparative Study of France, Germany, the UK and Norway.” Policy & Politics 44(3):383–402. doi: 10.1332/030557315X14298700857974.

- Jansson, G., and G. Ó. Erlingsson. 2014. “More e-Government, Less Street-Level Bureaucracy? On Legitimacy and the Human Side of Public Administration.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 11(3):291–308. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2014.908155.

- Jensen, D. C. 2018. “Does Core Task Matter for Decision-Making? A Comparative Case Study on Whether Differences in Job Characteristics Affect Discretionary Street-Level Decision-Making.” Administration & Society 50(8):1125–47. doi: 10.1177/0095399715609383.

- Jilke, S., and L. Tummers. 2018. “Which Clients Are Deserving of Help? A Theoretical Model and Experimental Test.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 28(2):226–38. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muy002.

- Kampen, J. K., S. Van De Walle, and G. Bouckaert. 2006. “Assessing the Relation between Satisfaction with Public Service Delivery and Trust in Government: The Impact of the Predisposition of Citizens toward Government on Evaluations of Its Performance.” Public Performance & Management Review 29(4):387–404. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20447604.

- Keiser, L. R., V. Wilkins, K. J. Meier, and C. Holland. 2002. “Lipstick and Logarithms: Gender, Identity, and Representative Bureaucracy.” American Political Science Review 96(3):553–65. doi: 10.1017/S0003055402000321.

- Kingsley, J. D. 1944. Representative Bureaucracy: An Interpretation of the British Civil Service. Yellow Springs, O. Brentwood, California: The Antioch Press.

- Kuhlmann, S, and J. Bogumil. 2021. “The Digitalisation of Local Public Services. Evidence from the German Case.” Pp. 101–13 in The Future of Local Self-Government. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Kuhlmann, S, and H. Wollmann. 2019. Introduction to Comparative Public Administration: Administrative Systems and Reforms in Europe. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kumlin, S., and B. Rothstein. 2005. “Making and Breaking Social Capital: The Impact of Welfare-State Institutions.” Comparative Political Studies 38(4):339–65. doi: 10.1177/0010414004273203.

- Lewalter, D., C. Geyer, and K. Neubauer. 2014. “Comparing the Effectiveness of Two Communication Formats on Visitors’ Understanding of Nanotechnology.” Visitor Studies 17(2):159–76. doi: 10.1080/10645578.2014.945345.

- Lipsky, M. [1980] 2010. (Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Maynard-Moody, S., and M. Musheno. 2000. “State Agent or Citizen Agent: Two Narratives of Discretion.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10(2):329–58. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024272.

- Meier, K. J. 1993. Politics and the Bureaucracy: Policy-Making in the Fourth Branch of Government. 3rd ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Metts, S, and S. Planalp. 2003. “Emotional Communication.” Pp. 339–74 in Handbook of Interpersonal Communication, edited by M. L. Knapp & Daly J. A. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Meuser, M, and U. Nagel. 2009. “The Expert Interview and Changes in Knowledge Production.” Pp. 17–42 in Interviewing Experts, edited by A. Bogner, B. Littig, & W. Menon. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moore, M. H. 1995. Creating Public Value: strategic Management in Government. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Naff, K. C., and K. J. Capers. 2014. “The Complexity of Descriptive Representation and Bureaucracy: The Case of South Africa.” International Public Management Journal 17(4):515–39. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2014.958804.

- Nielsen, V. L. 2007. “Differential Treatment and Communicative Interactions: Why the Character of Social Interaction is Important.” Law & Policy 29(2):257–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9930.2007.00255.x.

- Nielsen, V. L., H. Ø. Nielsen, and M. Bisgaard. 2021. “Citizen Reactions to Bureaucratic Encounters: Different Ways of Coping with Public Authorities.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 31(2):381–98. doi: 10.1111/puar.13402.

- Picciotto, S. 2007. “Constructing Compliance: Game Playing, Tax Law, and the Regulatory State.” Law & Policy 29(1):11–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9930.2007.00243.x.

- Purcell, M. 2006. “Urban Democracy and the Local Trap.” Urban Studies 43(11):1921–41. doi: 10.1080/00420980600897826.

- Raaphorst, N. 2021. “Administrative Justice in Street-Level Decision Making: equal Treatment and Responsiveness.” in The Oxford Handbook of Administrative Justice, edited by J. Tomlinson, R. Thomas, M. Hertogh, & R. Kirkham. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Raaphorst, N., S. Groeneveld, and S. Van de Walle. 2018. “Do Tax Officials Use Double Standards in Evaluating Citizen-Clients? A Policy-Capturing Study among Dutch Frontline Tax Officials.” Public Administration 96(1):134–53. doi: 10.1111/padm.12374.

- Raaphorst, N., and K. Loyens. 2020. “From Poker Games to Kitchen Tables: How Social Dynamics Affect Frontline Decision Making.” Administration & Society 52(1):31–56. doi: 10.1177/0095399718761651.

- Ravin, Y, and C. Leacock. 2000. “Polysemy: An Overview.” Pp. 1–29 in Polysemy: Theoretical and Computational Approaches, edited by Y. Ravin & C. Leacock. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rothstein, B. 2009. “Creating Political Legitimacy:Electoral Democracy versus Quality of Government.” American Behavioral Scientist 53(3):311–30. doi: 10.1177/0002764209338795.

- Rothstein, B., and D. Stolle. 2008. “The State and Social Capital: An Institutional Theory of Generalized Trust.” Comparative Politics 40(4):441–59. doi: 10.5129/001041508X12911362383354.

- Sarangi, S, and S. Slembrouck. 2014. Language, Bureaucracy and Social Control. London: Routledge.

- Saunders, Benjamin., Julius. Sim, Tom. Kingstone, Shula. Baker, Jackie. Waterfield, Bernadette. Bartlam, Heather. Burroughs, and Clare. Jinks. 2018. “Saturation in Qualitative Research: exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization.” Quality & Quantity 52(4):1893–907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8.

- Thunman, E., M. Ekström, and A. Bruhn. 2020. “Dealing with Questions of Responsiveness in a Low-Discretion Context: Offers of Assistance in Standardized Public Service Encounters.” Administration & Society 52(9):1333–61. doi: 10.1177/0095399720907807.

- Watzlawick, P. J. B. Bavelas, and D. D. Jackson. 2011 [1967]. Pragmatics of Human Communication: A Study of Interactional Patterns, Pathologies and Paradoxes. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Weisberg, D. S., A. R. Landrum, S. E. Metz, and M. Weisberg. 2018. “No Missing Link: Knowledge Predicts Acceptance of Evolution in the United States.” BioScience 68(3):212–22. doi: 10.1093/biosci/bix161.

- Welch, C., R. Piekkari, E. Plakoyiannaki, and E. Paavilainen-Mäntymäki. 2011. “Theorising from Case Studies: Towards a Pluralist Future for International Business Research.” Journal of International Business Studies 42(5):740–62. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2010.55.

- Yackee, S. W., and D. Lowery. 2005. “Understanding Public Support for the US Federal Bureaucracy.” Public Management Review 7(4):515–36. doi: 10.1080/14719030500362389.

- Zacka, B. 2019. “Street-Level Bureaucracy and Democratic Theory.”Pp. 448–61 in Research Handbook on Street-Level Bureaucracy, edited by P. Hupe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.