Abstract

Background

Support from significant others is important for participation in everyday life for persons with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Meanwhile, significant others also experience limitations.

Aims

To explore how support is expressed by persons with RA and significant others, and how support relates to participation in everyday life of persons with RA.

Material and methods

Sixteen persons with RA and their significant others participated in individual semi-structured interviews. The material was analyzed using dyadic analysis.

Results

Persons with RA and significant others reported that RA and support had become natural parts of everyday life, especially emotional support. The reciprocal dynamics of support were also expressed as imperative. Also, support from people outside of the dyads and well-functioning communication facilitated everyday life.

Conclusions

Significant others and the support they give are prominent factors and facilitators in everyday life of persons with RA. Concurrently, the support persons with RA provide is important, along with support from outside of the dyads.

Significance

The results indicate that the interaction between persons with RA and the social environment is central to gain insight into how support should be provided for optimal participation in everyday life. Significant others can preferably be more involved in the rehabilitation process.

Introduction

The dyadic relationship of a person with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and a significant other can be put to the test by the disease. This chronic inflammatory disease can force identities to change and maintaining social roles can be problematic [Citation1], especially during the early phases of RA [Citation2]. Current routines with early diagnosis and early instituted disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are effective and related to reduced disease activity and fewer impairments [Citation3]. However, people still experience disabilities [Citation4] and report symptoms associated with RA to be constantly present on a daily basis [Citation5]. Also, symptoms of stiffness, pain and fatigue can impact everyday life negatively both psychologically and socially [Citation1], and both the persons with RA and their significant others might need to make adaptations and changes in their everyday life [Citation6]. In addition, RA is often an unpredictable disease with fluctuating symptoms that are not visible to others [Citation7]. Therefore, the difficulty for others to comprehend disabilities can lead to strained relationships [Citation8]. Yet, even when the person considers a partner to be understanding, the dyadic relationship can still be negatively affected, in terms of intimacy and inclusion in family events [Citation9]. However, significant others as part of the person’s social environment, influence choice, performance and satisfaction in occupations [Citation10]. They are valued in terms of the support they provide [Citation8] and can be essential in helping to manage symptoms like pain [Citation7, Citation11]. Furthermore, participation in everyday life, which refers to the concepts of involvement in and sharing occupations in general, is highly influenced by the social environment [Citation12].

There are different types of support: emotional, instrumental, and informational support [Citation13]. Within the dyads of persons with RA and significant others, the latter have been reported to provide both emotional and instrumental support [Citation14]. Support from significant others is also wanted from persons with rheumatic diseases, but at the same time, it should not impact the person’s autonomy, which can be a challenging balance [Citation15]. Informational support is also expected from the healthcare system to cope with the disease [Citation16].

Furthermore, a gap between support wanted and support provided has been identified, as persons with inflammatory arthritis report to be asked or provided to only half the extent they want [Citation17]. At the same time, there is a connection between support from significant others and enhanced participation in everyday life of persons with RA [Citation18]. This emphasizes the importance of further studies regarding the possible influence of support from significant others. In addition, despite today’s effective medication and considerable reduction of disease activity, disabilities are still evident [Citation4]. This suggests that more focus should be put on other types of interventions, such as the ones in the social environment.

Most existing literature regarding support and interactions between persons with RA and their significant others focuses on the persons with RA and their experiences. However, it is important to let both parties share their views, as one perspective otherwise can be overlooked [Citation11]. By using a dyadic approach, both perspectives are seen, and another aspect can be added that gives a more overall picture of the issues [Citation19]. Therefore, the aim of this study is twofold: (1) to explore how support is expressed in the dyadic relationships between persons with RA and their significant others, and (2) how this support can influence participation in everyday life of persons with RA.

Materials and methods

Design

In this qualitative interview study, we explore experiences and perceptions of persons with RA and their significant others. Dyadic analysis, which is used in this study, is useful when studying shared experiences and when focussing on the relationships within the dyads [Citation19].

Participants

This study is part of the multicentre project TIRA-2 (Early Interventions in Rheumatoid Arthritis) [Citation20]. Persons with RA were consecutively included in the project between 2006 and 2009 (criteria described elsewhere) [Citation6] and have been monitored through regular clinical follow-ups.

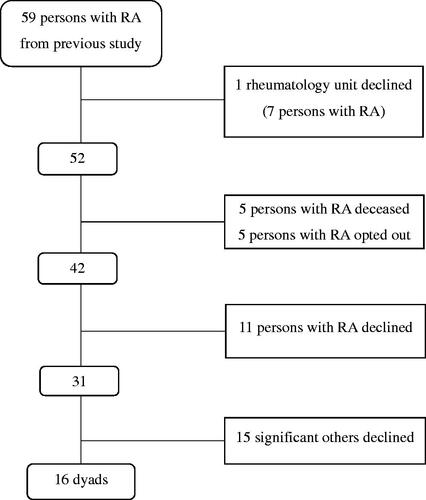

During 2009–2010, 59 persons from five rheumatology units involved in the TIRA project participated in an interview study. The inclusion criteria were having three years of experience of RA and being of working age (<64 years of age) [Citation6]. Contact was made again with the involved units by first author (M. Be.) during 2018, approximately a decade after diagnosis, in order to invite the same 59 persons to the present interview study. One unit declined participation, 5 persons were deceased and 5 had terminated their part in the TIRA project, leaving 42 persons. These persons were invited by letter in which the aims of the study were described, and they were informed that participation was voluntarily, they could withdraw at any time without a specific reason, and that participation in the study would not affect their medical treatment. Together with the person’s invitation letter, a letter to a significant other was attached. The persons with RA were asked to give this letter to someone they themselves identified as a significant other, in order to invite them to this interview study. Inclusion criteria for the present study were that both the person with RA and a significant other accepted participation. Reasons for declining varied widely, such as comorbidities, having a too busy schedule, that no significant other lived nearby or that they had participated in several research projects earlier. In total, 16 persons with RA and their significant others accepted (). In this study, the participants are referred to as ‘persons with RA’, and ‘significant others’, and together as ‘dyads’. The participants consisted of 12 persons with RA–partner dyads, three parent–child dyads and a person with RA–friend dyad (), these different formations are later discussed in the Methodological considerations section. The sample of persons with RA had a mean age of 62 years and consisted of 50% women. The significant others had a mean age of 59 years and 69% were women.

Table 1. Demographic data of persons with RA.

Data collection

Individual semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions were conducted. An interview guide based on the previous guide from the data collection of 2009–2010 was developed (available on request) and included the larger topics of ‘participation’ and ‘support’, with follow-up questions on each topic. The questions were adapted depending on whether the respondent was the person with RA or the significant other.

Prior to the interviews, the questions were pilot-tested on one person with RA and a significant other. Discussions between the interviewer (M. Be.) and the two respondents were held directly after the interviews, and some minor changes regarding wording and order of questions were made. The pilot interviews are not included in the analysis. The participants chose the location of the interview: their workplace, home, a public library, at the hospital, or at the university. The interviews were conducted by two of the authors (M. Be., Å. L. R.) and one research assistant. None of the interviewers was involved in the rehabilitation of the participants with RA, and two people within the same dyad were never interviewed by the same researcher. One goal was to complete the interviews with each dyad pair within as small timeframe as possible. In three cases, it was even possible to conduct the interviews simultaneously. At most, six weeks passed between the two interviews within the same dyad. All the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews with the participants with RA lasted between 18 and 71 min and the interviews with the significant others between 17 and 55 min. All data were collected between October 2018 and November 2019.

Data analysis

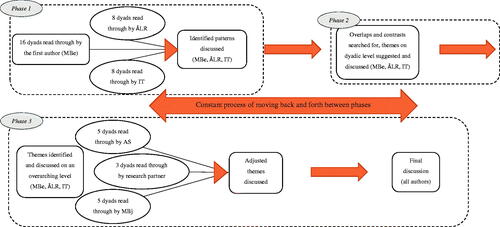

Descriptions on dyadic analysis are lacking, therefore the dyadic analysis was conducted using the procedure of Eisikovits and Koren [Citation19], and with inspiration from several other studies that based their analyses on the same strategy [Citation21–23]. The first phase involves performing individual analysis on each interview, identifying quotes that provide understanding of the person’s experiences and allowing themes to emerge from the material [Citation24]. The second phase is to perform an analysis within each dyad, consisting of persons with RA and their significant others. In doing so, contrasts and overlaps between the different versions were assessed and new themes thus emerged on a dyadic level. Our third phase consisted of performing an overarching analysis across the dyads. All authors and one research partner were part of performing the analysis in the different phases.

During the first phase, all of the material (32 interviews, 16 dyads) was read through by the first author (M. Be.) to make sense of the material as a whole. Notes were written in the margins and important patterns identified in search for themes. As a validation, authors Å. L. R. and I. T. simultaneously identified patterns and quotes from 16 interviews each (8 dyads each). In conducting the second phase, overlaps and contrasts were searched for between the different individuals within the dyads. At this stage, the three authors had individually performed phase one and two as described above. The patterns and possible themes on a dyadic level were discussed among the three authors in respect to the aims of the study until consensus was reached. Thereafter, in the third phase, the first author (M. Be.) organized the quotes by coding and identifying overarching themes across the dyads. Suggested themes were discussed and validated by authors Å. L. R. and I. T., and thereafter adjusted accordingly. The adjusted overarching themes were then discussed and validated by authors A. S. and M. Bj., who had read 10 interviews each (5 dyads), as well as a research partner who had read six interviews (3 dyads). Thereafter, all authors participated in a discussion about the results until consensus was reached ().

The aim during the analysis process was to have as many dyad reports read by as many researchers as possible, to increase credibility [Citation25]. Therefore, the division of dyads was deliberately selected by M. Be. All dyads were read through by two researchers, and most of the dyad reports were read by three.

In the search for contrasts and overlaps between individuals within the dyads, only common conceptual patterns fit into the analysis; meaning that if something was only mentioned by one of the two parties, it was not a part of the analysis. Presented in the Results section are therefore themes built around the overarching themes across the dyads. To illustrate the importance of central conceptual patterns, these have been emphasized using italics throughout the Results section.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by The Regional Ethics Committee at Linköping University, Dnr 2018/158-31 2019-00733. All participants gave their written consent to take part in this interview study.

Results

From the analysis, it was apparent that RA had over time become a natural part of the dyads’ everyday life. Furthermore, the dynamics of support played an important role, and emotional support was expressed as the most prominent type of supportive dynamic. It was also important to have functioning relationships and support from people surrounding the dyads. Finally, communication and information-sharing were substantial aspects of everyday life. All these conceptual patterns were intertwined and constitute the overarching themes across the dyads.

Time is a friend

The analysis revealed a multifaceted view on the everyday lives of persons with RA and their significant others. One major aspect was the fact that the dyads had been a part of each other’s lives for a long time, up to 54 years, and RA and everything that came with it had over time become a natural part of their everyday lives together: they had ‘grown together’. The adaptations made and the new routines had become such a natural part of life that neither the person with RA nor the significant other gave it much thought. It had not interfered with their roles within the dyad, nor the relationship. Adapting the performance of activities had become natural, as well as planning and arranging activities in other ways compared to before RA. ‘To learn to live with it’ was a common way of expressing this experience.

It…becomes natural I guess so that I might not think about it much…but… It is like that. You avoid heavy stuff and too strenuous things. #2, man with RA

…then of course you feel that you have to take [RA] into consideration of course when you decide activities or whatever it is. But it’s so marginally and it’s not a problem. But it kind of just happens. Partner of #2

As time had passed, both parties within the dyads also expressed that they had become better at adapting activities. Often the person with RA could be perceived as stubborn – both from his/her own perspective, as well as the significant others’ – but this had sometimes been toned down over the years. This fact added a positive note to the aspect of RA existing as a natural part of the dyad’s everyday life.

…I refuse to realise some things, but reality catches up on you. #3, man with RA

And to ask for help, that certain things you can manage. He manages it but then he gets hurt and then it’s better to ask for that help and he has gotten better at that. And that I’m glad for. Partner of #3

However, in some cases, the stubbornness still remained, which could cause tension within the dyad, when the person with RA did not want to accept assistance with activities, even though the significant other considered it to be necessary.

But otherwise I live as usual, I, I don’t want any other people [telling me] that no you can’t, you’re ill, you can’t, I don’t want that. #4, woman with RA

Well, it’s a little hard to help mummy because she’s very proud so she prefers to manage herself. Daughter of #4

The dynamics of support

Within the dyads, there was often a mutual understanding concerning support. However, support was found to be very complex and touching different aspects of everyday life. Different amounts and types of support were reported by both parties during different periods of time. All the dyads had long-lasting relationships and they were familiar with the fact that RA interfered with everyday life to different degrees. Often both parties mentioned the same symptoms – fatigue, pain and grip weakness – as something that could interfere with everyday life, forcing them to adapt or withdraw from activities. Mostly it was the persons with RA who expressed a need for support when being recently diagnosed with RA. During that initial time period, they were forced to go through changes and adapt to new routines which could require support. Examples include activities like getting dressed, as well as smaller disruptions, such as problems with opening cans and packages. Emotional support was however more pronounced. This could, for example, be illustrated by the significant other restricting the person with RA from performing certain activities, such as heavier tasks they both knew could cause pain to the person with RA later. It could also be in the form of talking, listening and sharing opinions. As the persons with RA and their significant others knew each other very well, emotional support was often exchanged without much thought given to it. Both parties expressed that the support in itself had become a routine and a part of everyday life and was something that existed naturally.

You don’t think about it. It’s an everyday routine. We live together like two siblings, one could compare it to. We have known each other since… since we were kids. So… No, it’s nothing, it’s working well. #11, man with RA

Well, if something were to happen to me he would fill in for me, I know that. Close friend of #11

The emotional type of support was also something that had remained for the whole disease course, even when the practical support was no longer needed. One important aspect of support was the fact that it was reciprocal within the dyads. Both parties expressed how they felt deeply supported by the other person, and there was a common perception of always being there for each other.

It’s in every aspect really. It…it happens all the time without you really thinking about it. But there is always something or someone who…well, you can turn to so to speak. #5, man with RA

You are there for each other, of course, if it’s needed. Without getting protective, but you are there for each other and… well, really are there when it’s needed. Wife of #5

It’s my mom and I can always trust her no matter what. Yes, she would do anything for me. Of course I know that. #9, woman with RA

Well but when we talk, it’s like I know she’s there and supports me if I need it. The feeling of knowing that there is someone. Mother of #9

Although, within some dyads, there was an imbalance when it came to emotional support, such as the person with RA needing more support than the significant other offered. However, in some cases, the significant other wanted to give more support than the person with RA was willing to receive. Both parties speculate that this could be due to a sort of stubbornness where the person with RA would not discontinue performing certain activities due to, for example, pain. Insisting that persons with RA should accept certain limitations could also generate changes in their self-esteem and roles. Disappointment was also apparent, for instance when a person with RA needed physical support with dressing and did not feel that he could live up to the expectations of him in the role of a man, partner and father. In this case, emotional support continuously occurred within the dyad. Regarding the dyads’ perceptions of tenacity, this had usually been less of a problem during recent years as mentioned earlier, in conjunction with the fact that the dyads had learned to live with the circumstances.

Well, I think I did get quite a lot of support in the beginning even though I didn’t want it, I didn’t realise my limitations really. #3, man with RA

He has kind of understood that he needs to back away sometimes and ask for help. Partner of #3

In cases of both parties agreeing on the amount and exchange of support, the person with RA was not necessarily the one in need of most support. The dynamics of support had also changed in some cases over the years. Sometimes the significant other had been the one in need of most support, in which cases the person with RA had offered it. The dynamics of support had also changed regarding the aspect of time. For example, within the dyads where the significant other was a child or parent, the circumstances had been different when they lived together earlier.

When I talk to my sister about what it has become she says “Oh, it sounds just like you have become a mum”, that we have switched roles, so it’s things like that I have heard that others think about me. Daughter of #4

I think that we have always had a great relationship and been supportive in different ways and different ages of course, when I was younger the support of course looked different, naturally when I lived at home or when I moved away and that makes relationships change, but we have always had a very close relationship. Daughter of #6

Also, in some cases, the significant other had undergone a sickness that demanded more immediate attention than RA. In these cases, it was indisputable for the person with RA to help and support the significant other, further emphasizing the reciprocal dynamics of support.

He supports me greatly. Without him I couldn’t manage. So now the roles have changed. I used to be there a lot for [husband] but now I have become like this, so now it’s him who supports me a lot. Wife of #14

We need support from others

For the exchange of support to function well within the dyads, sometimes extended support was needed from outside of the dyad. For instance, the daughter of a person with RA expressed a need for emotional support from her partner to be able to give support to her mother. This was a way of facilitating this particular dyad’s relationship and their everyday lives. Another example was support from the healthcare system, often in the form of information. Both parties within the dyads speculated that lack of knowledge was sometimes a potential reason for miscommunication. Significant others requested more information about RA from the healthcare system to be able to give more appropriate support. This was partly fulfilled during the very early course of RA, but later the significant others did not sustain information or interventions in their favour. Specific suggestions to fulfil their needs were different types of networks for significant others and people close to persons with rheumatic diseases. Even the persons with RA could express a wish for more interactions with peers.

…I wish that there was something else for movement, to be able to move so to speak, in different situations. I feel that’s missing, to be able to come to a group of peers where you can get support and get started. #10, man with RA

Maybe more information about…I haven’t thought about it until now that if there is any information about the disease then maybe you would want that, what it really is, what kind of assisting devices he could get? Wife of #10

Both inside and outside of the dyads, activities had evolved in certain directions and had been divided between the ones involved in a manner that facilitated the activity performance of the person with RA. This means that people outside of the dyads, such as other family members also made adaptations of activities in favour of the person with RA. These adaptations had been made without anyone really communicating it, they had just become a part of everyday life. Examples of adaptations were letting the person with RA handle lighter activities. As mentioned before, the aspect of time also played an important part in this matter, where people outside of the dyads had been a part of the dyads’ lives for a long time, and adaptations had been made gradually and naturally. As within the dyads, to be there for each other was also pronounced within the family or circle of friends.

Well they [the children] have…they help instantly. So that… My daughter knows what it’s like so she says, this morning it was two bags of hay, then she said, well you take the small one and I will take this one. So they have gotten used to it. #13, woman with RA

Yes, really it’s our son and daughter who are helping out a lot. Husband of #13

What we share with each other

The fact that the dyads had long-lasting relationships seemed to facilitate their everyday lives. Often they communicated through silence and could read each other well, meaning that the support needs in both directions could be fulfilled without any specific requests being asked out loud. In many cases, both parties within the dyads could ‘read between the lines’ when it came to the other person and offered support or assistance. Still, persons with RA might not want to emphasize their need for assistance.

But the ones closest can sometimes, not too often but sometimes, well, now I see that you are in pain. Yes I am. And then there’s nothing more to it. #6, woman with RA

…more than that I…see that she’s swollen and have ongoing flare-ups and I can say that it must be hard but then there’s nothing more to it. Daughter of #6

Within some dyads, however, the needs had to be expressed or were not fulfilled. In these cases, the significant others could indicate that the person with RA chose to be silent and not share feelings or updates from a clinical visit. This could lead to uncertainty from the significant others’ point of view, such as not having enough information to give the best support. From the point of view of the persons with RA on the other hand, a lack of interest from the significant others was also revealed.

I think it’s very hard for those who don’t have an autoimmune disease to know how it can affect, kind of, both mind and soul, body, everything. And it’s really hard to explain, you can’t do that. #1, woman with RA

I still don’t know what kind of problems she has and so on. The only thing I know really is that she is in pain. Aching sometimes. That she gets so called relapses, that it kind of gets worse for a while and the better. I don’t know much more. Partner of #1

Even in cases when the significant other showed interest and the person with RA tried to share medical updates, the communication could still be complicated within dyads. The persons with RA expressed that significant others could understand the symptom of pain, but not how much pain. At the same time, the significant others might then perceive the information about pain as tiresome when nothing could be done for relief. Although, there were also examples of dyads where the person with RA did not necessarily share their status but it did not cause communicative or emotional issues, such as:

It’s been a long time since I had proper pain but sometimes…I get pain in my hands sometimes and then, I fumble and then he can notice that I can’t hold things if we do something. But otherwise I rarely say that gosh that hurts, I can’t do that, that I never do. #16, woman with RA

She’s got a really high pain threshold, with what she feels, and she’s probably in more pain than I can imagine many times. She doesn’t really share with me then but she handles it herself. Partner of #16

Due to differences in what information was shared, and also the sometimes-invisible nature of RA symptoms, views within dyads could differ regarding the impact of RA on everyday life. For example, the person with RA could express that it limits activities to some extent, but his/her significant other could express that RA was hardly noticeable on a daily basis. Again, an uncertainty could be indicated. In the following quotes, a woman with RA mentions consequences, whereas from the significant other’s point of view, she might as well not have RA at all.

Because it’s not only what’s visible, and the pain. The pain I can handle. On the other hand, the fatigue, I don’t know if I’m going to accept that ever. And that, they don’t understand. Or they do and I don’t believe it, I don’t know. #1, woman with RA

To be perfectly honest I don’t notice a huge difference really. Partner of #1

Both parties within the dyads talked about the importance of openness and honesty with communication. The dyads who reported having well-functioning communication with openness and honesty, also reported well-functioning everyday life.

Discussion

Our results showed different aspects of the multifaceted everyday life of persons with RA and their significant others. RA had, over time, become a natural part of everyday life and they had learned to live with it; which facilitated participation in everyday life. The dynamics of support were both apparent and expressed as very important for the relationship; the exchange of emotional support was particularly evident. Also, the sources of support from outside of the dyads were important in relation to support, as well as well-functioning communication and the sharing of information. All these aspects – the aspects of time, open and honest communication, and the constant exchange of support both inside and outside of the dyads – were things that facilitated the dyads’ participation in everyday life.

The reciprocal dynamic of support was often expressed as the secure sense of ‘always being there for each other’, which prominently shows the emotional support. Emotional support has previously been connected to less depressive feelings in persons with RA [Citation26] and better physical function and general health in persons with other autoimmune diseases [Citation27]. It is, however, important to mention that an imbalance sometimes existed between the emotional support received and the emotional support needed within our dyads. Swift et al. [Citation28] found that significant others who mean well can create tension in the relationship, something that could be avoided through more knowledge. This reappears in our results and motivates the question of a joint approach to the disease and rehabilitation process, including both the person with RA and the significant other.

As a result of early diagnosis and early instituted medical treatment, persons with RA show less activity limitations [Citation4], lower disease activity [Citation20], and work disability has declined [Citation29,Citation30]. Despite these improvements, RA still affects valued activities in everyday life [Citation31]. People in our study all had access to biological DMARDs from time for diagnosis, but RA could still cause a need for adaptations. Therefore, we need to keep developing rehabilitation strategies for persons with RA and, considering our results, further investigate how the positive influence of significant others and their support can be included.

People with chronic illnesses can experience problems with managing symptoms and keeping control over social roles and identities [Citation32]. Within our dyads, it was often expressed that roles and relationships had been kept more or less intact, which corresponds to previously reported results [Citation6,Citation33]. Although when a chronic disease is followed by limitations in activities and everyday life, one’s occupational identity can be forced to alter. To re-establish this, the person often must undergo a process of change while becoming familiar with new roles and can create an identity separate from the disease [Citation34], which can be related to our dyads expressing a change in roles over time. This change in roles also referred to both the consequences of children growing up, and partners falling ill. Re-establishing occupational identity also involves feeling supported and understood [Citation34]. This highlights our results emphasizing the exchange of support between the persons with RA and their significant others, and in particular the emotional type of support. Thereby, this emotional support is essential when re-establishing occupational identity.

Significant others and support as part of the environmental factors are important facilitators for participation in everyday life [Citation35]. Participation as a prevalent concept within rehabilitation also involves dimensions such as supporting others, and engaging in reciprocal relationships [Citation36], which in our results was expressed as valuable, and constitutes a good foundation for participation. Ahlstrand et al. [Citation18] found that lack of understanding from significant others can restrict participation for persons with RA and, correspondingly, that support from significant others generates participation. In our results, the importance of significant others is clear, and the social environment is an important part of a person’s life. Therefore, we should further investigate how this can be used in rehabilitation and further facilitate participation in everyday life of persons with RA.

Our dyads had often, as they phrased it, ‘grown together’, and the mutual support had been a natural part of everyday life. The concept of facing a disease such as RA as a team has previously been paid attention [Citation15] and could establish a basis for rehabilitation interventions. The recent study by Brignon et al. [Citation33] suggests a joint approach for coping with inflammatory arthritis, something our results contribute to in emphasizing the constant support within the dyads. Our dyads also expressed a need for support from others, such as information from the health care system, which is when health care professionals can play an important part in actively involving significant others in the rehabilitation process.

Patient education in different forms exists, but whether there is an established method that is particularly successful is debateable. Accessible information for family members has previously been emphasized [Citation28], and the involvement of significant others has been highlighted as part of patient-centred care [Citation37]. Untas et al. [Citation15] report a strong will from persons with RA for their significant others to gain more knowledge about the disease, and a mutual wish for more information was expressed from our dyads. Again, this relates to a joint approach that can be undertaken in the rehabilitation process, where significant others participate, for example, in clinical visits, information meetings, and discussions with peers. Today we also have the possibility of considering digital interventions. For example, online communities have been reported to be a resource for expressing needs and feeling acknowledged [Citation38]. The suggested joint approach could also be considered in a digital form, where both the persons with RA and significant others have the possibility to easily access meetings and discussions with peers as well as health care professionals. In addition, it has been suggested that occupational therapists should take an active part in strategies such as attaining participation in individual and shared activities and, identifying imbalances in household activities [Citation39]. Therefore, significant others could be seen as an asset whose potential could be used to a larger extent in the rehabilitation of persons with RA.

The complexity of support can preferably be considered when developing rehabilitation strategies, but to make it more solid, further and larger studies should be undertaken. For example, quantitative studies collecting opinions and needs for support in larger samples could be another step towards using support in the rehabilitation process.

Clinical implications

Despite current routines with early diagnosis and early instituted effective medication, RA is associated with disabilities [Citation4,Citation20]. Thereby, it is a need for forthcoming multidisciplinary interventions. The importance of significant others and their support in everyday life is expressed by persons with RA, which suggests a need for more active involvement of significant others in the rehabilitation process after the diagnosis of RA. The multidisciplinary team could further invite significant others to accompany persons with RA to clinical visits, patient education sessions and information meetings, to increase their knowledge and understanding regarding the disease process and consequences in everyday life. This might facilitate both the dyadic relationship as well as participation in everyday life of persons with RA and their significant others.

Methodological considerations

Our material consisted of several combinations of dyads, mostly couples, but also close friends and parent–children combinations. This gives a broad overview of the relationships between the persons with RA and their significant others. The different combinations of dyads enriched our material as well as added to the complexity of the matter. In addition, one essential part of this project was that the persons with RA themselves chose the person they considered a significant other. This is to keep in line with definitions such as those from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare [Citation40], and Webster’s dictionary [Citation41], which derives from the person’s own subjective perceptions. Also, in today’s society, families and relationships might look less traditional, and therefore we cannot assume that a spouse undeniably is the one closest to the person. Still, all persons with RA in our study who were in a spousal relationship chose this person as their significant other. If we, however, were to have included only spouses or only children, different concerns might have been identified.

When using a purposeful sampling procedure, it is always important to consider what impact this might have on the results. We are not aware of all the reasons for declining, and one can speculate that the relationships in these cases were problematic. The dyads participating expressed good relationships for the most part, which might have influenced the results. It would have been interesting to also get the stories from dyads with more problematic relationships. Specific experiences and needs can be further investigated in studies focussing solely on such dyads.

There is a variation considering the location of the interviews. This might have influenced the answers and thereby our results. Nonetheless, the choice of location was always left to the participants, ensuring that they could choose the location most convenient and where they could feel safe to express their thoughts. When conducting the interviews away from the participant’s home, it was always in a closed and private space, which should be considered to enhance the feeling of safety for the participants.

A strength in this study is that several researchers and a research partner were involved in the analysis of the material, as a way of triangulation. Although the research partner was not involved in other phases of the study, verifying the views of persons with RA during the analysis is considered a strength. In most cases, dyad reports were read through by three researchers, which made the decisions during the analysis process more reliable [Citation25]. However, in some cases, several weeks passed between the two interviews within the same dyad, which is a limitation. Furthermore, interviews were conducted by three different researchers. In most cases, however, one researcher (M. Be.) interviewed the persons with RA, and another (research assistant) interviewed the significant others. This means that the participants might have received questions in slightly different manners, even though all researchers followed the interview guide. Nonetheless, no participants within the same dyad were interviewed by the same researcher, a decision made early in the planning due to an ethical discussion. In addition, data collection before dyadic analysis can take different shapes, interviewing the dyad in pairs or separately depending on the aim of the interviews [Citation19]. In this case, we were not after a visible interaction between the two parties, but rather to have each individual speak as freely as possible around the topics. If the same researcher had interviewed both persons within the same dyad, we could have asked more specific questions based on the information gained from the first interview. The choice to have different interviewers for the persons with RA and the significant others is based on that the interviewer then had no preunderstanding of the dyad’s situation and therefore could conduct the interview in a more objective and unbiased manner.

Conclusions

Different aspect and dynamics of support occur in everyday life of persons with RA and their significant others. Both parties expressed that this reciprocal support had become a natural part of everyday life over time, especially emotional support. They also described that well-functioning communication facilitated participation in everyday life, and also that people outside of the dyads were important sources of support. This study indicates a need for further research to identify which type of support can facilitate and optimize participation in everyday life, and how this can be used in a joint rehabilitation process.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants of this study for generously sharing their stories, as well as Eva Valtersson, research assistant, and Birgitta Stenström, research partner, for their valuable contributions.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Parenti G, Tomaino SCM, Cipolletta S. The experience of living with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative metasynthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:3922–3936.

- Kristiansen TM, Primdahl J, Antoft R, et al. It means everything: continuing normality of everyday life for people with rheumatoid arthritis in early remission. Musculoskelet Care. 2012;10:162–170.

- Shadick NA, Gerlanc NM, Frits ML, et al. The longitudinal effect of biologic use on patient outcomes (disease activity, function, and disease severity) within a rheumatoid arthritis registry. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3081–3092.

- Ahlstrand I, Thyberg I, Falkmer T, et al. Pain and activity limitations in women and men with contemporary treated early RA compared to 10 years ago: the Swedish TIRA project. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44:259–264.

- Flurey CA, Morris M, Richards P, et al. It's like a juggling act: rheumatoid arthritis patient perspectives on daily life and flare while on current treatment regimes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:696–703.

- Bergström M, Sverker A, Larsson Ranada Å, et al. Significant others' influence on participation in everyday life – the perspectives of persons with early diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42:385–393.

- Bergström M, Ahlstrand I, Thyberg I, et al. 'Like the worst toothache you've had' – How people with rheumatoid arthritis describe and manage pain. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24:468–476.

- Dures E, Fraser I, Almeida C, et al. Patients' perspectives on the psychological impact of inflammatory arthritis and meeting the associated support needs: pen-ended responses in a multi-centre survey. Musculoskelet Care. 2017;15:175–185.

- Alten R, van de Laar M, De Leonardis F, et al. Physical and emotional burden of rheumatoid arthritis: data from RA matters, a web-based survey of patients and healthcare professionals. Rheumatol Ther. 2019;6:587–597.

- Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling occupation II: advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being, & justice through occupation. 2nd ed. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 2013.

- Pow J, Stephenson E, Hagedoorn M, et al. Spousal support for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: getting the wrong kind is a pain. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1760.

- Law M. Participation in the occupations of everyday life. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56:640–649.

- Helgeson VS. Social support and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(1suppl):25–31.

- Fallatah F, Edge DS. Social support needs of families: the context of rheumatoid arthritis. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;28:180–185.

- Untas A, Vioulac C, Boujut E, et al. What is relatives' role in arthritis management? A qualitative study of the perceptions of patient-relative dyads. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:45–53.

- Poh LW, He HG, Lee CS, et al. An integrative review of experiences of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:231–247.

- Dures E, Almeida C, Caesley J, et al. Patient preferences for psychological support in inflammatory arthritis: a multicentre survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:142–147.

- Ahlstrand I, Björk M, Thyberg I, et al. Pain and daily activities in rheumatoid arthritis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1245–1253.

- Eisikovits Z, Koren C. Approaches to and outcomes of dyadic interview analysis. Qual Health Res. 2010;20:1642–1655.

- Thyberg I, Dahlström Ö, Björk M, et al. Hand pains in women and men in early rheumatoid arthritis, a one year follow-up after diagnosis. The Swedish TIRA project. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:291–300.

- Hochman Y, Segev E, Levinger M. Five phases of dyadic analysis: stretching the boundaries of understanding of family relationships. Fam Process. 2020;59:681–694.

- Van Parys H, Provoost V, De Sutter P, et al. Multi family member interview studies: a focus on data analysis. J Fam Ther. 2017;39:386–401.

- Hudson N, Law C, Culley L, et al. Conducting dyadic, relational research about endometriosis: a reflexive account of methods, ethics and data analysis. Health (London). 2020;24:79–93.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th ed. London (UK): SAGE Publications, Inc; 2015.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research – generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Benka J, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, et al. Social support as a moderator of functional disability's effect on depressive feelings in early rheumatoid arthritis: a four-year prospective study. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59:19–26.

- Georgopoulou S, Efraimidou S, MacLennan SJ, et al. The relationship between social support and health-related quality of life in patients with antiphospholipid (Hughes) syndrome. Mod Rheumatol. 2018;28:147–155.

- Swift CM, Reed K, Hocking C. A new perspective on family involvement in chronic pain management programmes. Musculoskelet Care. 2014;12:47–55.

- Hallert E, Björk M, Dahlström Ö, et al. Disease activity and disability in women and men with early rheumatoid arthritis (RA): an 8-year followup of a Swedish early RA project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1101–1107.

- Rantalaiho VM, Kautiainen H, Järvenpää S, et al. Decline in work disability caused by early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a nationwide Finnish register, 2000–8. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:672–677.

- Östlund G, Thyberg I, Valtersson E, et al. The use of avoidance, adjustment, interaction and acceptance strategies to handle participation restrictions among Swedish men with early rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskelet Care. 2016;14:206–218.

- Townsend A, Wyke S, Hunt K. Self-managing and managing self: practical and moral dilemmas in accounts of living with chronic illness. Chronic Illn. 2006;2:185–194.

- Brignon M, Vioulac C, Boujut E, et al. Patients and relatives coping with inflammatory arthritis: care teamwork. Health Expect. 2020;23:137–147.

- Walder K, Molineux M. Occupational adaptation and identity reconstruction: a grounded theory synthesis of qualitative studies exploring adults’ experiences of adjustment to chronic disease, major illness or injury. J Occup Sci. 2017;24:225–243.

- Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, et al. Environmental barriers and supports to everyday participation: a qualitative insider perspective from people with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:578–588.

- Hammell KRW. Belonging, occupation, and human well-being: an exploration. Can J Occup Ther. 2014;81:39–50.

- Voshaar MJ, Nota I, van de Laar MA, et al. Patient-centred care in established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29:643–663.

- Cipolletta S, Tomaino SCM, Lo Magno E, et al. Illness experiences and attitudes towards medication online communities for people with fibromyalgia. IJERPH. 2020;17:8683.

- Swift C, Hocking C, Dickinson A, et al. Facilitating open family communication when a parent has chronic pain: a scoping review. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26:103–120.

- National Board of Health and Welfare [Internet]. Stockholm (Sweden): National Board of Health and Welfare; [cited 2020 Nov 14]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/.

- Merriam-Webster [Internet]. Springfield (MA): Merriam-Webster Inc; [cited 2020 Nov 14]. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/