Abstract

Background

Work is an occupation of great concern for younger stroke survivors. Given the high rate of people not working after stroke, there is a need to explore work after stroke from a long-term perspective, including not just an initial return to work, but also the ability to retain employment and how this may affect everyday life after stroke. Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore experiences relating to work and to work incapacity among long-term stroke survivors.

Method

This study used thematic analysis on data gathered through individual semi-structured interviews with long-term stroke survivors.

Results

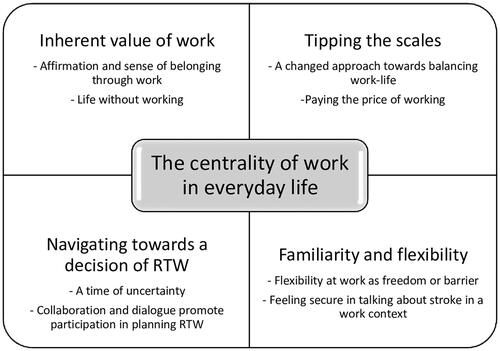

The analysis resulted in four themes that together comprised the main theme ‘The centrality of work in everyday life’, containing descriptions of how everyday life was affected by aspects of work both for those who did work and those who did not return to work after stroke.

Conclusion and significance

The results highlight the importance of addressing return to work not just as an isolated outcome but as part of everyday life after stroke. The results indicate a need for a more flexible approach to supporting return to work that continues past the initial return.

Introduction

Work is an occupation of great concern for younger stroke survivors [Citation1]. Being able to return to work (RTW) is described as an important milestone and sign of recovery for many stroke survivors [Citation2,Citation3], as it is related to a sense of regaining their former role, being the person they used to be and to living up to internal and external expectations [Citation3]. Qualitative studies show that younger stroke survivors use situations related to work to describe life after stroke [Citation4] and emphasise work and social life when describing situations of successful participation [Citation5].

To date, most studies on RTW after stroke focus on the rates of RTW or factors leading up to a successful RTW. However, the RTW process can encompass a broader perspective than initial return. According to Young et al. [Citation6], RTW is an evolving process including not just re-entry, but also retention and advancement. The process is described ‘as encompassing a series of events, transitions and phases and includes interactions with other individuals and the environment. The process begins at the onset of work disability and concludes when a satisfactory long-term outcome has been achieved’ (p. 559). The outcome of the process can be both returning to work and not returning [Citation7]. The perspective on RTW as re-entry or as an evolving process will affect how different studies report on outcome.

Few quantitative studies have examined different RTW outcomes in relation to time since stroke [Citation8], especially long-term [Citation2]. A recent systematic review of work-related factors and RTW after stroke found that a relatively low number of studies have explored whether RTW is sustainable or whether people who have returned to work after a period of time will go back on sick leave or for other reasons stop working [Citation9]. Those studies that have provided long-term rates for RTW after stroke give a varied picture with a rate of RTW ranging from 10% to around 85%. While some studies have found increasing rates of RTW over time [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11], others have reported a decline in the years following an initial return [Citation2,Citation12–14]. Thus, there is need to differentiate between initially returning to work and remaining in work, as people with stroke may return to work but be unable to retain employment over time. To date there are few studies addressing these differences in outcome, especially from a qualitative perspective.

Recent qualitative studies have reported that stroke survivors have to set priorities and make adjustments in order to retain employment. This includes work related factors such as changing workplace, reducing hours, adapting the workload and omitting work tasks [Citation15–17]. Stroke survivors have also been reported to set priorities about their social and leisure activities in relation to work [Citation5,Citation16,Citation17]. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that retaining work will affect not just their working lives but also their private lives.

Given the high rate of people not working after stroke, there is a need to further explore work after stroke from a long-term perspective, including not just re-entry into employment, but also aspects of sustainability within the context of everyday life. This can provide important information on aspects not necessarily addressed during the initial RTW process. Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore experiences relating to work and to work incapacity among long-term stroke survivors.

Materials and methods

This study is part of a larger project with the objective to explore the long-term performance and experiences of everyday life occupations among young and middle-aged stroke survivors and factors that may affect the ability to engage in these occupations. It is the second of two studies that used a qualitative design within this project. Both studies utilise the same interview data, coded into two separate datasets during the first two phases of thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke [Citation18].

Participants

Participants were recruited from a subsample of the Sahlgrenska Academy Study on Ischaemic Stroke (SAHLSIS) at the University of Gothenburg, described in detail by Jood et al. [Citation19]. They all had an ischaemic stroke and were treated in hospital between 2000 and 2003. Inclusion criteria for this study were: previously participating in SAHLSIS with data from baseline and 7-year follow-up, 18–60 years of age at time of index stroke and verbal ability in Swedish. Persons with severe language or cognitive dysfunctions were excluded only if it affected the ability to understand oral and written information about the study. The participation of persons with concurrent acute illness during the recruitment phase was discussed with a physician, and such persons were excluded if this was considered to affect interview topics. The number of eligible participants was 18.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg, Dnr: 1100-17 (interviews) and Dnr: 413-04 (data relevant to prior participation in SAHLSIS). All participants gave verbal and written informed consent prior to the interviews.

Data collection

Demographic data and information about stroke severity were collected from the SAHLSIS database and by a brief questionnaire at the time of the interview. Data were collected by interviewing long-term stroke survivors. The interviews were individual and conducted face-to-face by the first author (CW) using a semi-structured interview guide. The interview guide covered four main areas: Returning to everyday life after stroke, Occupational engagement over time, Occupational engagement within a context, Development and application of strategies in everyday life. All participants were interviewed twice, with the second interview focussed on elaborating what had been discussed during the previous interview. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim by the first author (CW).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using thematic analysis following the guidelines for analysis provided by Braun and Clarke [Citation18]. The analysis includes the following six phases; Familiarising yourself with your data; Generating initial codes; Searching for themes; Reviewing themes; Defining and naming themes; Producing the report. Phase one of gaining familiarity with the data began with the transcription of recorded interviews, and for each set of interviews, also involved the preparation for the second interview. When all interviews had been completed and transcribed, two authors (CW and GC) were active in all phases of the analysis. Further, two authors (CB and LC) read the transcripts, coding schemes and descriptions of themes. During the analysis regular meetings were held to facilitate the developing of themes. In the final phases a fifth author (KJ) was involved to provide input for finalising the themes, and analysis continued until consensus was reached on the definitions and names for all themes and subthemes. During the analysis the data program NVIVO 12 pro was used to sort and move between different levels of data. In the phases of reviewing, defining and naming themes, mind-maps served as a way of visualising potential themes and merging them into a structure of main themes and subthemes. Examples illustrating the analytic process can be found in Supporting Information.

Aimed at understanding the subjective experiences of participants and recognising the interpretative work for the latent level of the analysis, this study aligns with interpretivism and more specifically constructivism. Interpretivism and constructivism embrace subjectivity and are context sensitive [Citation20,Citation21]. Thus, the interpretative approach aims at grasping the diversity of experiences [Citation22].

Results

Through convenience sampling 9 participants were included. The median time between interviews was 7 days. Reasons for non-participation were as follows: ongoing illness (2), declined (3), not able to be reached (3) and unable to understand verbal information due to cognitive dysfunction (1). Interviews were carried out between February and August 2019. The locations of the interviews were at home (n = 7), at a clinic (n = 1) and in the home of a significant other (n = 1). Two of the participants chose to have a significant other present during the interviews. For one, this was due to responsibility for a significant other who was unwell. This person did not participate in the interview but was present in the room. For the other participant, this was due to communication difficulties caused by the stroke. The significant other did participate in the interview, but only when the person being interviewed asked for clarifications. At the time of stroke onset 6 participants had been working full-time, 2 had been working part-time and 1 had been on full-time sick-leave. After their stroke 6 participants had experience of returning to the workplace. Further characteristics of included participants are presented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of participants, n = 9.

The analysis resulted in the themes Inherent value of work, Tipping the scales, Navigating towards a decision of RTW and Familiarity and flexibility. Together these four themes comprise the main theme ‘The centrality of work in everyday life’ and contain descriptions of how everyday life was affected by aspects of work both for those who did work and those who did not return to work after stroke. Overview of themes and subthemes are shown in .

Inherent value of work

Working provided a sense of being valued and of belonging to a social and societal context. If a person was no longer able to work, this left a void to be filled by other occupations and opportunities for belonging.

Affirmation and sense of belonging through work

For many, work was something highly valued both through confirming a role in society and by providing a social context. Having worked since a young age, participants described how they viewed their work role as an integral part of who they are. Returning to work after stroke was experienced as a clear sign of improvement and for some a central part around which they built the rest of their life.

- How important was it for you to be able to return to work and be able….

- Everything!!

- Everything

- It was. If I had to choose between winning a million and going back to work, I would have chosen work. That was entirely,…. work was your life when you came back.

Gradually able to return to work, participants described how they had felt pleased with themselves in returning and how work brought joy. Though not able to work as much or do exactly the same as before, being back at work confirmed that they had abilities and were back on track. Through being able to share responsibilities and decisions with others they felt competent and able to contribute. For some, work had also been a way to divert thoughts and focus on the positive.

Work fulfilled a social need and provided a sense of belonging. Having early contact with co-workers prior to a return was valued, and when employers or co-workers initiated the contact, it made participants feel that they meant something to others. Returning to work meant being surrounded by other people again, and appreciation from others was an important aspect of work. When describing their situation upon having returned to work, some participants described the positive feelings of being part of a team.

Life without working

Not being able to work for many participants meant significant changes in their everyday life. Work had been a significant and valued part of life prior to stroke and giving it up left a void to be filled. Looking back at the time since leaving work, some spoke of the positive sides such as having more time to spend with family and friends and on other valued occupations. Some initially focussed their energy on rehabilitation. This was later also replaced by other new leisure activities. Others found new occupations that matched their work experience and enabled them to make use of their work skills and to feel appreciated and capable. Although able to function in work-like situations, the occupations engaged in after leaving work differed from gainful work in that participants were able to choose when and to what extent they wanted to take on responsibilities.

There were, however, also negative aspects of not working, and participants spoke of how they missed working. Some had found it difficult to maintain the structure but also the sense of meaning that they previously had obtained from work. Not working was then described as a barrier for engaging also in other occupations, and some participants were unable to replace work with new occupations.

I was used to going to work every day. For 18 years I worked there. And I was always busy with things and then all of the sudden…felt a bit meaningless after that.

Tipping the scales

The onset of stroke led participants to re-assess their work-life balance. For some, reaching and maintaining a balance was an ongoing struggle where working had adverse consequences affecting other areas of life.

A changed approach towards balancing work-life

Participants described how they had enjoyed working and felt responsibility in their position at work prior to stroke. Although taking pride in their work, some participants also described how the perceived responsibility had contributed to high levels of work-related stress prior to stroke. The feeling that stress, especially that of a stressful work situation, was a strong contributing factor for having had a stroke was shared by several participants. Some felt anger towards the workplace after their stroke, feeling that too high a workload or decreasing personnel resources had been a contributing factor. One participant described how she perceived struggling to maintain a high level of service in her work as related to the onset of stroke.

I was there, always. With joy. But then, sometimes I could not manage when the levels of stress got so high and I was there alone. So, you know, I snapped sometimes and (said) can’t you see for yourselves that this doesn’t work. But I did not understand that it would end up as badly as this.

Others attributed stress to factors beyond the actual workplace. For some, intensive work had been a way of life, a lifestyle that they had chosen and shared with family. For others, working overtime and taking on leisure projects had been a way of dealing with grief. Regardless of whether they felt that the responsibility for a stressful situation lay within the workplace or was related to other factors in life, the onset of stroke had increased awareness of risk factors. Participants described that after their stroke they did not want to go back to the same work-life situation as before. They became more cautious of stressful situations, which in turn affected their approach towards returning to work after stroke.

Paying the price of working

Work was an occupation that for most also had adverse consequences. For some, the consequences were felt mainly in the early phase of returning to their workplace. For others, more severe consequences surfaced as they continued to push themselves over longer periods of time.

For some, it was not until when they returned to their workplace that they began to notice less visible consequences of stroke, such as headache, fatigue and sensitivity to stress. Participants described feeling more tired when returning to work compared to when on sick leave and how every task at work was more difficult and required more energy to perform than before stroke. Attempting to return to their workplace, some experienced immediate physical consequences, such as diarrhoea or difficulty sleeping, and work became a source of worry.

Overall, many described being more susceptible to stress and how the workplace was a place where they were more likely to feel stressed. They described difficulties in handling conflicts, and how they had been unable to think clearly under pressure. However, for some, returning to their workplace to some extent also reduced stress. Having a strong sense of duty in their work role, feeling obligated towards others and not being able to fulfil those obligations when on sick leave was experienced as more stressful than working.

Many years after stroke, the impact still fluctuated and was highly dependent on the situation. Participants described how it was not the hours worked as much as situational factors, such as number of people present or level of perceived pressure, that affected their ability to perform at work and how they experienced stroke related consequences.

And there were many times when I just left work and went home. Despite not working full-time. Because it was not about the amount of time I worked, it was about the situation.

Investing time and effort into performing at work also had consequences for their personal life. Although able to perform at work, some had felt the consequences of fatigue to a greater extent in their private life and expressed this as the price of working. For many, work was described as one of the main social arenas. However, participants also experienced that work had impacted on other social contacts, as they lacked the energy to pursue social activities after work.

Having worked sometimes twice the amount of time they were supposed to and pushing themselves hard at work, some described how it had been difficult to separate private life and work life. One participant described how work gradually resulted in negative effects on her health until she eventually felt completely drained of energy. High pressure at work had affected not only health, but also personal relationships.

I hit the wall. Really, I did, bang on. And, and if I had not quit (work) I think it would have ended in divorce.

Navigating towards a decision of RTW

For many, reaching a decision on RTW was a long process that involved dealing with uncertainty. The process of RTW was affected by the dialogue and collaboration between different people involved.

A time of uncertainty

The time leading up to a decision on RTW was described as a time of uncertainty. Whether eventually returning or not, many described how they had initially expected to return to their previous workplace, but how the timeframe and level of recovery were difficult to grasp.

They gave me a doctor’s certificate of sick leave for three months. And I, there was no…mathematical possibility, I thought that I would need sick leave for that long. But it became three months many times over before I got well. More or less. And then I began working. One step at a time.

Trusting that they eventually would return was for some enough to handle the time of uncertainty. Although RTW could take much longer than initially expected, they adjusted to the process of RTW and focussed on recovery. Others described how with time they had to come to terms with the fact that RTW was not possible, as they gradually came to understand that fatigue and cognitive disabilities were too great a barrier to overcome. Physical impairments were easier to accept as a hindrance and led to accepting sickness compensation without attempting RTW.

After stroke many were restricted from driving for a period of time. Although driving restrictions impacted negatively on RTW, these were not necessarily addressed by stakeholders in the RTW process, which contributed to feelings of uncertainty. For those attempting early RTW, driving restrictions became a barrier. Many lived in suburban or rural areas with limited access to public transport, which affected ability to work by increasing the time and energy spent on the commute.

Being a family provider as well as financial commitments at work was an initial source of worry when facing a more uncertain future. The national sickness compensation and private insurance systems were perceived to offer limited opportunities for a flexible RTW. Some participants experienced a choice between economy and health. Financial resources were sometimes described as a prerequisite for support and served to reduce the stress of financial uncertainty. Some participants described how they had had the foresight to save up for the future, which enabled both them and spouses to have time from work to focus on the process of recovery. Being financially independent was expressed as making it easier to accept that it would not be possible to return to work.

Collaboration and dialogue promote participation in planning RTW

For many, the RTW process involved a number of different persons and views, such as those of significant others, the employer, the Social Insurance Agency and health care professionals. The opportunities for and clarity of communication in these collaborations had an impact on how participants viewed their own role in the RTW process. If participants returned to work within a short period of time, the potential need for support and collaboration was not necessarily addressed. Wanting to return as soon as possible, some participants described choosing to return when the doctor’s certificate for sick leave expired after 3–4 months without further communication. Although pleased at being able to return so soon, they did in hindsight acknowledge that support from health care professionals could have been useful upon returning. Sometimes the only communication with public authorities was over the phone or by post. One participant described how he had wanted a long-term plan and collaboration but felt that this was hindered through lack of physical meetings.

- Send over all the paperwork and you can have, it wasn’t early retirement, it was called something else. It was like, getting it done with and moving on to the next one. That’s how it seemed to me.

- And you would have liked to…

- Well, I would have liked to meet a person, eye to eye, as we are sitting here

Wanting to return to work, but experiencing the collaborations aimed at RTW as insufficient, some turned to family and health care professionals for support and were able to begin the process of RTW. Others described how they early on felt pressured to return to work or increase working hours although not feeling ready. Sometimes the pressure came from the workplace. Other times it was a result of rules and regulations that inform the system for financial compensation following illness. Balancing financial impact with health, one participant described how he felt pressured to work full-time or not at all. However, clear communication with both health care professionals and the Social Insurance Agency enabled him to make the decision of accepting full-time sickness compensation.

Although most participants initially visualised a return to their previous workplace, there were situations during the RTW process where the conversation had turned towards the option of returning to work in a new workplace. In these cases, participants had found it difficult to consider a new and unknown workplace, especially if the benefits were not made clear and if the consequences of stroke were not taken into consideration. In these conversations participants were sometimes reliant on others, such as a physician speaking on their part, to help clarify their ability to work after stroke.

Familiarity and flexibility

Flexibility, not just in the RTW process, but also when having returned was important for well-being and to retain employment. Flexibility was described as opportunities for adjusting work in accordance with abilities and was supported through returning to a familiar workplace and being able to communicate about stroke. For some, adjustments led to feelings of frustration and decreased sense of belonging at the workplace.

Flexibility at work as freedom or barrier

For those participants who attempted to RTW, this was a process that involved a gradual increase in number of working hours and/or days and for some also adjustment of the working environment and tasks. While a gradual increase in the number of working hours was often decided upon as part of the RTW process, participants also described a flexibility in work time that was more reliant on having a familiar and allowing work context. An example of this was the employer allowing time off on short notice for the participant to stay at home for a day when feeling too stressed. Others, however, found it difficult to limit the time spent on working. If this meant continuously working more than the agreed upon hours, flexibility could instead become a barrier for maintaining employment.

Flexibility also referred to adjusting work tasks. Being gradually entrusted with greater responsibility and having opportunities to influence their own work situation enabled participants to increase their effort at work over time. Some participants experienced that their abilities at work fluctuated. This required flexibility and adjustment during the workday. Examples of this were being able to take short breaks when tired or taking a step back in stressful situations, feeling certain that someone else took over.

There were also examples of when changes in the situation at work became a barrier to keep on working. Changes in flexibility or workload were sometimes deal breakers between staying at work or having to quit. One participant who had been working for many years after her stroke described how a changed work climate resulted in early retirement. When no longer able to influence her work situation, the only way she felt able to influence her well-being was by leaving work.

For others, a gradually increasing workload was a source of frustration. When working fewer hours was the only adjustment made, one participant described how she felt that working part-time was much more than half the work, as she still had the same work tasks and spent as much time getting ready for work and on the commute. Some felt that working part-time decreased the sense of belonging at the workplace. Working fewer days made it difficult to be part of what went on at the workplace. Missing out on information meant having to spend more time catching up and figuring out what to do.

Yes, you feel a bit left out. When you can’t be at work. It kind of is that way, more easily, that someone just working part-time, they become (left out). I’m thinking in terms of information.

Feeling secure in talking about stroke in a work context

Knowing and having good relations with employers and co-workers were of great importance when returning to the workplace. In order to receive understanding and support at work participants were dependent on their ability and will to communicate as well as the willingness of others to listen and try to understand. Some had no problems in telling their co-workers about stroke early on, often before returning to work. Being open about their consequences of stroke, participants felt that they often received sufficient support to keep on working. This involved talking about how they had to adjust when at work and how others can help. Others chose not to mention stroke within a work context. Having a high position at work or being dependent on customer relations, some felt that it was risky to talk about stroke as others might consider it a weakness. Further, some felt that it was difficult to tell their employer when being pushed to work too hard. Rather than communicating this to employers or co-workers, they instead considered the option of sick leave.

Discussion

Our findings confirm the difficulties in returning to and retaining employment that have been reported in quantitative studies [Citation2,Citation12] and suggest the need for a discussion of what a satisfactory long-term outcome is. We found that work was a central part of participants’ lives, both before and after a stroke. In a long-term perspective, work involved many aspects beyond an initial return. The experiences shared by the participants contribute to the understanding of how work can have diverse consequences that affect everyday life after stroke.

Successful RTW has been reported as an important sign of recovery [Citation2,Citation3,Citation17], which was confirmed by participants in our study. For those able to return, work can evoke positive feelings of affirmation and belonging. The appreciation received from others shows that, when given the right circumstances, stroke survivors can still feel able to make significant contributions at a workplace despite residual impairments. This study included those who did not return to work and those who received sickness compensation after initial attempts. We found that although some were able to focus on positive aspects of not working, others struggled to fill a void left by not working. For those unable to retain employment, a loss of identity and depression have previously been reported [Citation16]. Considering the large group of people not working after stroke and based on the results of this study, there is likely a proportion of these people that would benefit from interventions aimed at promoting new occupations that provide the meaning and structure previously gained from work.

In line with previous studies [Citation5,Citation17,Citation23], participants experienced persistent consequences of stroke that affected their ability to work, as well as their ability to pursue social and leisure activities. In similarity to the findings of Turner at al. [Citation16], many re-evaluated their work-life balance and, being more aware of risk factors, re-organised their priorities in attempts to reduce stress. In setting these priorities, stroke survivors have been reported to appraise value in relation to consequences [Citation24,Citation25]. In our study participants ascribed a high value to work and for those returning to work this was an occupation that was often prioritised over other occupations. Prioritising a valued activity can lead to a decrease in another [Citation4] and may provide some explanation for the decrease in social and leisure activities reported both here and in other long-term studies [Citation5,Citation16,Citation17]. Being at work was by some described as increasing symptoms, leading to other negative health events and affecting private life. This was expressed as paying the price of working and indicates that finding and maintaining a balance can be difficult. Some acknowledged a conscious choice of prioritising work, feeling that the price at the time was worth paying, while others in hindsight questioned the price. The adverse consequences for health and everyday life raise questions about what a reasonable price of working might be and whether some of the adverse consequences can be avoided with access to preventive support.

Return to work has been reported as a complex process involving multiple stakeholders [Citation26]. In line with a study by Medin et al. [Citation3], collaboration in the RTW process was described as important but sometimes lacking. Our findings show that the RTW process is experienced differently depending on the level of dialogue and collaboration between those involved and thus highlight the need for individualised support. In similarity to other studies [Citation17,Citation27], participants in our study described a period of uncertainty relating to work ability, timeframe of recovery and how this can impact their life situation. Although no specific timeframes can be given early after stroke, our findings indicate that the level of uncertainty might be reduced and managed through open and clear communication. It is also worth noting that at an early stage after stroke, a person may not yet be aware of the extent of their changed abilities [Citation26]. In our study participants described how it was not until when they were back in a work context that they became aware of some of the less visible consequences of stroke such as fatigue and sensitivity to stress. These are consequences that have previously been reported as key barriers to RTW after stroke [Citation26]. Thus, a longer period of continued collaboration and follow-up could be beneficial during a gradual RTW. This could allow a greater sense of control and participation but also access to support when consequences of and for work become manifest.

In our study participants who were able to return to work went back to their previous workplace. They stressed the importance of returning to a familiar workplace, which they in turn felt allowed for adjustments. The workplace is important for the ability to retain employment, and studies have shown familiar people enhance reengagement and that a stable work environment where stroke survivors feel safe and secure promotes RTW [Citation3,Citation17,Citation28]. Upon returning to work, many were dependent on flexibility at the workplace. As shown in other studies, a common adjustment that enabled participants to work was a graded RTW, both in terms of hours, but also responsibilities and tasks while at work [Citation3,Citation5,Citation17,Citation26–28]. For some, flexibility was not just a matter of a gradual increase, but of continuously having the opportunity to adjust to fluctuating abilities. In our study participants described returning to work at a time in society when they felt that there was still room for flexibility, but that this had become more difficult with time as the pressure at many workplaces had increased. Sarre et al. [Citation27] have previously reported that legislative infrastructure can negatively impact RTW. The flexibility and familiarity stated as highly important by stroke survivors for retaining employment may be challenged by less flexible legislation.

Methodological considerations

A strength of this study is that we included also those who did not return to work or had to terminate their employment after an initial return, thereby providing a wider range of experiences relating to work. The transferability of results is affected by the selective sample. With a timeframe of up to 18 years after stroke onset the selection is naturally skewed towards those with milder stroke at onset and transferability to people with more severe stroke is therefore limited. The youngest participant in this study was over 45 years at stroke onset, and an upper age limit was set at 60 years at stroke onset. Therefore, the results may not be representative for younger stroke survivors or those closer to retirement at time of stroke. There is also a risk of recall bias as the interviews took place 15–18 years after stroke and at an age when most participants had retired. Transferability to the current work context is limited due to the long timeframe, as considerable changes in work climate and legislation guiding RTW have occurred since. However, the findings from this study also provide knowledge that can inspire future interventions, as they are not just bound to context but address key factors for a sustainable employment that are applicable in current work contexts.

We used a model presented by Malterud et al. [Citation29] to guide sample size based on information power. Although the final sample came to include all available participants, the a priori estimated number of 8–10 participants was reached. When all nine available participants had been interviewed, the model by Malterud et al. was reviewed again. The two dimensions affecting information power that we could not control for beforehand were specificity and dialogue. Despite the use of convenience sampling, specificity within the sample was judged to be sufficient, and the dialogue was generally strong. Thus, the consensus among the researchers was that no further recruitment was necessary to increase information power. The inclusion also of individuals with expressive communicative difficulties in interviews is considered a strength, as this is common in stroke survivors but still often considered to be an exclusion criterion.

To establish trustworthiness a number of steps were taken. These will be addressed here using the criteria presented by Lincoln and Guba [Citation30] and recently addressed in an article by Nowell at al. [Citation31] on how to meet criteria for trustworthiness in thematic analysis. Regardless of the analytical procedure used, credibility is enhanced if the data are analysed by more than one researcher [Citation31]. Here, two researchers were active in all phases of analysis, and initial coding was done individually and then together. Credibility was further enhanced by tape recording and transcribing all interviews making them available for two more of the co-authors. This allowed for regular discussion to challenge the progression of the analysis and to ensure that interpretations and findings remained grounded in the data, thereby also enhancing confirmability. The use of repeat interviews contributed to the credibility of the findings by allowing clarifications to be made. However, credibility might have been further enhanced if transcripts and findings had been checked by participants. Dependability and confirmability were strengthened by the use of documentation in accordance with the COREQ guidelines [Citation32]. Along with this documentation, supporting notes were made concerning thoughts, discussions and decisions made throughout the entire process from designing the studies to completing the analysis. A limitation was that a more structured form of audit trail was not documented.

The first author has a PhD and more than 10 years of clinical experience working as an occupational therapist in the area of stroke rehabilitation. The co-authors all have more than 20 years of research experience along with extensive clinical experience within various areas of stroke rehabilitation and medicine. Reflexivity was enhanced through regular discussions within the research group, where the different backgrounds allowed for the pre-understanding of authors to be challenged.

Conclusion and implications

In summary this study shows that work will affect various aspects of everyday life after stroke for both those who return and those who do not. Our findings highlight the need to not only address RTW as a onetime isolated outcome but as part of everyday life after stroke. Focussed on the long-term perspective, including but also going beyond an initial RTW, the findings indicate a need for addressing the consequences of work in relation to other aspect of everyday life. The fact that some participants were dependent on support and adjustments to retain employment and that this was an ongoing challenge throughout their work life indicate a need for a more flexible approach to supporting RTW that continues past the initial return and focus on the individual in their context. Occupational therapists with their expertise in occupational engagement and how this can be used to enable individuals to retain meaningful occupations and engage in new occupations can play an important role in the RTW process. Ideally, a flexible approach to RTW support should provide access to support when circumstances change and should focus on sustainability. Future research that concern the content of such support and how to make it available is required.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express a warm thank you to the participants in this study for sharing your experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The most relevant data and quotes are within the paper. Complete interview data cannot be made publicly available for ethical and legal reasons. Such information is subject to legal restrictions according to national legislation. Specifically, in Sweden confidentiality regarding personal information in studies is regulated in the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act (SFS 2009:400).

The interviews contain potentially sensitive personal information that cannot be completely de-identified. The minimal data underlying the results of this study might be made available upon request, after an assessment of confidentiality. A formal request by named researchers, with a stated reason for requesting data, will be taken under careful consideration by Lisbeth Claesson, associate professor at Department of Health and Rehabilitation, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, The Sahlgrenska Academy at Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kuluski K, Dow C, Locock L, et al. Life interrupted and life regained? Coping with stroke at a young age. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2014;9:10.

- Sen A, Bisquera A, Wang Y, et al. Factors, trends, and long-term outcomes for stroke patients returning to work: the South London Stroke Register. Int J Stroke. 2019;14:696–705.

- Medin J, Barajas J, Ekberg K. Stroke patients’ experiences of return to work. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:1051–1060.

- Wassenius C, Claesson L, Blomstrand C, et al. Integrating consequences of stroke into everyday life – experiences from a long-term perspective. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;29:1–13.

- Törnbom K, Lundälv J, Sunnerhagen KS, et al. Long-term participation 7–8 years after stroke: experiences of people in working-age. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213447.

- Young A, Roessler R, Wasiak R, et al. A developmental conceptualization of return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:557–568.

- Öst Nilsson A. ReWork-Stroke: content and experiences of a person-centred rehabilitation programme for return to work after stroke. Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet, Dept of Neuroscience; 2019.

- Edwards JD, Kapoor A, Linkewich E, et al. Return to work after young stroke: a systematic review. Int J Stroke. 2018;13:243–256.

- Jood K, Fransson E. Faktorer i arbetslivet och återgång till arbete efter stroke eller risk för ny stroke: en kunskapsöversikt. Allmänmedicin: Avdelningen för samhällsmedicin och folkhälsa; 2021.

- Palstam A, Westerlind E, Persson HC, et al. Work-related predictors for return to work after stroke. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019;139:382–388.

- Westerlind E, Persson HC, Eriksson M, et al. Return to work after stroke: a Swedish nationwide registry-based study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020;141:56–64.

- Aarnio K, Rodríguez-Pardo J, Siegerink B, et al. Return to work after ischemic stroke in young adults: a registry-based follow-up study. Neurology. 2018;91:e1909–e1917.

- Endo M, Haruyama Y, Muto G, et al. Employment sustainability after return to work among Japanese stroke survivors. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2018;91:717–724.

- Garland A, Jeon S-HP, Rotermann MMA, et al. Effects of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health events on work and earnings: a population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2019;191:E3–E10.

- Vestling M, Ramel E, Iwarsson S. Thoughts and experiences from returning to work after stroke. Work. 2013;45:201–211.

- Turner GM, McMullan C, Atkins L, et al. TIA and minor stroke: a qualitative study of long-term impact and experiences of follow-up care. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20:176.

- Palstam A, Törnbom M, Sunnerhagen KS. Experiences of returning to work and maintaining work 7 to 8 years after a stroke: a qualitative interview study in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021182.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

- Jood K, Ladenvall C, Rosengren A, et al. Family history in ischemic stroke before 70 years of age: the sahlgrenska academy study on ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:1383–1387.

- Patton MQ. Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: a personal, experiential perspective. Qual Soc Work. 2002;1:261–283.

- Carcary M. The research audit trial – enhancing trustworthiness in qualitative inquiry. Electronic J Busin Res Methods. 2009;7:11–24.

- Kvale S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 1996.

- Balasooriya-Smeekens C, Bateman A, Mant J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to staying in work after stroke: insight from an online forum. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009974.

- Woodman P, Riazi A, Pereira C, et al. Social participation post stroke: a meta-ethnographic review of the experiences and views of community-dwelling stroke survivors. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:2031–2043.

- Norlander A, Iwarsson S, Jönsson A-C, et al. Living and ageing with stroke: an exploration of conditions influencing participation in social and leisure activities over 15 years. Brain Inj. 2018;32:858–866.

- Schwarz B, Claros-Salinas D, Streibelt M. Meta-synthesis of qualitative research on facilitators and barriers of return to work after stroke. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28:28–44.

- Sarre S, Redlich C, Tinker A, et al. A systematic review of qualitative studies on adjusting after stroke: lessons for the study of resilience. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:716–726.

- Jellema S, van Der Sande R, van Hees S, et al. Role of environmental factors on resuming valued activities poststroke: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative findings. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:991–1002.e1.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample Size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26:1753–1760.

- Lincoln YG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE; 1985.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis: striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:e021182.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357.