Abstract

Quality deliberation is essential for societies to address the challenges presented by the coronavirus pandemic effectively and legitimately. Critics of deliberative and participatory democracy are highly skeptical that most citizens can engage with such complex issues in good circumstances and these are far from ideal circumstances. The need for rapid action and decision-making is a challenge for inclusivity and quality of deliberation. Additionally, policy responses to the virus need to be even more co-ordinated than usual, which intensifies their complexity. The digitalisation of the public sphere may be seen as a further challenge to deliberating. Furthermore, these are stressful and emotional times, making a considered judgement on these issues potentially challenging. We employ a modified version of the Discourse Quality Index to assess the deliberative quality in two facilitated synchronous digital platforms to consider aspects of data use in light of COVID 19. Our study is the first to perform a comprehensive, systematic and in-depth analysis of the deliberative capacity of citizens in a pandemic. Our evidence indicates that deliberation can be resilient in a crisis. The findings will have relevance to those interested in pandemic democracy, deliberative democracy in a crisis, data use and digital public spheres.

Introduction

Meaningful and high-quality deliberation is essential for governments and public administrations to address the extreme challenges presented by the coronavirus global pandemic in an effective and legitimate manner (Aitken et al. Citation2020; Lavazza and Farina Citation2020; Parry, Asenbaum, and Ercan Citation2020). Policies and legislation introduced by governments in response to the pandemic, in the UK and numerous other countries, with a few notable exceptions, e.g. The Netherlands (Mouter, Hernandez, and Itten Citation2021) have been based on assumptions about public opinion and what restrictions to their lives people are willing to comply with (Sibony Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased reliance on scientific and technical expertise in making policy decisions, which raises questions about political accountability in policy making (Lavazza and Farina Citation2020; Weible et al. Citation2020). While scientific and technical expertise, when respected, is useful to address these issues, ultimately, such expertise cannot resolve the moral and political aspects of policy making. This needs to be done through public deliberation (Brown Citation2014). However, critics of deliberative and participatory democracy are highly skeptical that most citizens can engage with complex issues in good circumstances (Brennan Citation2016) and would likely conclude prioritisation of technical expertise is imperative during the current pandemic. Indeed, COVID 19 has led to increased questioning of the value of democracy (Flinders Citation2020; Kavanagh and Singh Citation2020) and a contraction of opportunities for political participation (Parry, Asenbaum, and Ercan Citation2020), clearly demonstrating the “inadequacy of existing public sphere infrastructure” (Trenz et al. Citation2020, 6).

There are though, challenges for deliberation in a pandemic as there is need for rapid action and decision-making, and communication can be “more demanding” (Trenz et al. Citation2021, 12). Additionally, policy responses need to be even more coordinated than usual, which intensifies their complexity (Weible et al. Citation2020). The spread of COVID 19 and government responses to contain it have caused a great deal of anxiety, and fury amongst the public, making inclusive and rational deliberation on these issues potentially more challenging (Bandes Citation2009; Saam Citation2018). While the digitalisation of the public sphere brings challenges and opportunities for democracy (Russon-Gilman and Peixoto Citation2019), we do not yet know the consequences an enforced relocation of the public sphere to the digital realm will have for citizen deliberation. For example, deliberative practitioners have had to adapt their know-how to new digital forms of public engagement (Involve Citation2020).

The pandemic may also be generating new forms of “public sphere resilience” (Trenz et al. Citation2021) that enables experimentalism, innovation, adaptation and the relocation of deliberative communication to the digital sphere. Never before have governments and civil society organisations been pushed into upskilling and building capacity for digital public engagement at the current scale and speed. We expect an acceleration of online deliberative capacity, an era of both creative development and consolidation. This paper contributes to building the evidence base in that direction.

Given the central role that coronavirus will play for the immediate, and possibly long-term, future of democracy, we investigate how people discuss coronavirus-related issues online in synchronous forums and explore whether they engage in quality deliberation on this issue. Two online forums in the UK were organised during the summer of 2020. The existence of these cases is, in itself, evidence of public sphere resilience. We conducted a content analysis of their deliberations on how personal data should be used in relation to the COVID 19 emergency response and beyond. This is a pertinent issue to assess pandemic deliberation in the UK; as over recent years, a number of high-profile public controversies around data use and reuse have focussed attention on the need for greater public engagement and deliberation to establish and maintain a social licence for current and future practices (Aitken et al. Citation2020). In each case study, discussions were facilitated with the aim of promoting deliberative norms. It is, therefore, reasonable to assess the extent to which these norms were present. A sample of discussions from the two cases were transcribed and coded using an adapted version of the discourse quality index. Its application to these cases enabled us to quantitatively identify which aspects of deliberation were present in the online debates and to overall assess the extent of deliberative resilience.

The paper proceeds in five sections. First, we review the literature on democracy and crisis and online deliberation. Second, we provide the details of our two cases and justify our case selection. Third, we explain our approaches to sampling and coding of the discussions. Fourth, we present our key findings. We conclude with reflections on what our findings mean for pandemic democracy, the resilience of deliberative democracy in a crisis and digital public spheres.

Democracy in Crisis, Democracy in a Crisis and the Digital Public Sphere

The pandemic is testing the capacity of democratic governance to act effectively, fairly and legitimately (Afsahi et al. Citation2020). Although the current predicament is novel, these challenges to democracy are not new. A period of global democratic recession has been underway since the economic crisis of 2008 (Foa et al. Citation2020), characterised by upheaval and renewal for democratic systems around the world (Escobar and Elstub Citation2019). Given this ongoing crisis of democracy, what hope is there for democratic practice in a crisis?

Yet, democracy and crisis can be seen as inextricable, in the sense that democracy itself is an open-ended project constantly undergoing development and contestation and often punctuated by instability and crisis (Ercan and Gagnon Citation2014). It has been argued that democracies are better at recovering from crises than at preventing them in the first place (Runciman Citation2015). The short-term thinking wired into the electoral lifeblood of liberal representative democracies is often seen as their Achilles heel—as illustrated by the climate crisis, despite six decades of steady warnings (Fischer Citation2017).

Here is where different meanings and practices of democracy can be consequential (Elstub, Liu, and Luhiste Citation2020, 432). There is a spectrum from minimalist forms of democracy, anchored on regular elections and representative government, and maximalist forms, built for ongoing citizen participation and representative governance. It has been suggested that decentralised governance and digital democracy infrastructure have been important factors for public sphere resilience in addressing the pandemic in some countries (Gaskell and Stoker Citation2020; Nabben Citation2020; Mouter, Hernandez, and Itten Citation2021).

Democratic systems respond to emergencies differently and have different opportunities for resilience depending on where they sit on that minimalist-maximalist spectrum. At one end, the minimalist version tends to seek effectiveness and expediency through the concentration of power, communication and expertise, whereas on the maximalist side, democracy is seen as a system of distributed intelligence, deliberation and action (Landemore Citation2012). These are, of course, simplifications and no democratic system sits comfortably at either end, but the distinction between systems predicated on government by the few or the many remains a crucial vector in democratic theory and practice (Fischer Citation2012).

The pandemic has fleshed out these contrasting approaches across the world (Afsahi et al. Citation2020). On the one hand, some executives have concentrated power in the name of expediency while side-lining the role of legislatures and undermining transparency and accountability. On the other, some civil society networks have played a crucial role in public sphere resilience by mobilising support and services, while scrutinising government action (SURF Citation2020).

In this context, there are growing calls for public engagement in the governance of pandemic responses and recovery (Aitken et al. Citation2020; Parry, Asenbaum, and Ercan Citation2020). As Celermajer and Nassar (Citation2020) argue, the pandemic should be a time to strengthen rather than weaken public engagement in policy and political participation. A lack of representation of diverse experiences, voices and knowledge reduces the epistemic capacity of democracy for effective deliberation and collective action (Landemore Citation2012). Nevertheless, in the absence of a supportive governmental infrastructure the public sphere may show deliberative, participatory and democratic resilience through experimentation, innovation, adaptation and reinvention (Trenz et al. Citation2021).

Given the tragedies the pandemic has caused, discussions on issues relating directly to coronavirus response policy could be emotional, hindering deliberative resilience. In politics, emotions are sometimes simplistically characterised as “mere drivers of irrationality, demagoguery and dangerous mass arousal” (Escobar Citation2011, 110). However, some thinkers have argued that the exercise of public virtue depends on the harmonious and co-productive relationship between reason and emotion (Nussbaum Citation2001). Contemporary developments in neuroscience and cognitive psychology (Kahneman Citation2011) support this long-standing philosophical insight: reason and emotion are inextricable. Scholarship on deliberative democracy has recently begun to grapple with this insight (Morrell Citation2010) particularly in light of critiques that questioned narrow accounts of rationality in deliberation (Young Citation2000). Empirical evidence is mixed as Saam (Citation2018) finds that emotion exacerbates inequalities, while Bandes (Citation2009) finds emotion and rational deliberation to be entirely compatible.

Another challenge for public deliberation in the pandemic is that due to restrictions on movement and gatherings, opportunities for public participation have largely moved online (Trenz et al. Citation2021) and the evidence on the extent that the digital public sphere is a favourable environment to foster good deliberation is mixed. One study found that online deliberators expressed a greater variety of viewpoints (less conformity to a group’s most popular opinion), showed more equality of participation than face-to-face counterparts; but in person deliberation was of higher quality, more inclusive of personal experiences and more enjoyable (Davies and Chandler Citation2012, 144). Anonymous participation seems to encourage people to contribute, particularly those seldom heard, but can also lead to irresponsible behaviour and potentially diminish participant satisfaction due to emotional distance between participants (Baek, Wojcieszak, and Delli Carpini Citation2011, 367; Davies and Chandler Citation2012, 152).

The quality of online deliberation depends on the design of the process and the choices behind it (Wright and Street Citation2007; Kennedy et al. Citation2020). Digital designs vary along various dimensions, for example, between active and passive engagement; synchronous (same time; voice-mediated) or asynchronous (different time; text-mediated) interaction; anonymity or identification of participants; using existing or new platforms; online, multi-channel or blended with offline (Friess and Eilders Citation2015).

An experimental study found that online deliberation via a synchronous-anonymous text chat showed fewer expressions of disagreement, fewer bold disagreements and less sustained disagreement than in face-to-face groups, while personal attacks were avoided in both settings (Stromer-Galley, Bryant, and Bimber Citation2015). This crucial dimension remains underexplored, particularly in synchronous audio-visual online deliberation –the focus of our paper. Another study found that both online and offline settings are equally likely to generate anger, and while online deliberation seems to induce less anxiety it can also generate less enthusiasm (Baek, Wojcieszak, and Delli Carpini Citation2011).

These are all tentative findings, from studies of very different political contexts and online spaces, and despite recent developments, online deliberation research is still in its infancy (Towne and Herbsleb Citation2012). It must also be noted that many studies have been conducted in experimental settings, often involving convenience samples, rather than as in the cases in this paper, in “real life” contexts and with a cross-section of citizens directly affected by the issues under deliberation. There is also an important empirical gap, due to limited research on the communicative process itself, rather than the design, context and outcomes of online deliberation. A recent review of the online deliberation literature regarding institutional and experimental arenas (as opposed to everyday internet discussions) concludes that “we still have no idea as to whether deliberative-type discussion actually occurs within online deliberation events” (Strandberg and Grönlund Citation2018, 370). We agree with these authors about the “utmost importance” (Strandberg and Grönlund Citation2018, 371) of carrying out empirical research on these matters, especially now the public sphere has been increasingly digitalised in the COVID 19 pandemic. To do this, we analyse the quality of deliberation in two cases.

Case Studies of Online Deliberation

We adopted a case study approach to enable our study to move beyond covariation between variables and focus on “causes-of-effects” (Mahoney and Goertz Citation2006) due to the depth, and contextualised nature, of data that can be collected in case study research. Case studies are good for theory building (Toshkov Citation2016) which is appropriate for our needs given the lack of existing research on digital deliberation in a crisis. As a result, our case studies can be classified as “critical cases” (Yin Citation2014) and examples of experimental and adaptive modes of coping response to the coronavirus pandemic with the aim of preserving and relocating citizen deliberation. Although this project is not comparative, we wanted our cases to be of most similar design (Anckar Citation2008), and on a related issue, relevant to COVID 19, without systematically matching all control variables.

Many studies support the notion that unstructured online discussion does not foster deliberative quality – structure, clear purpose and human facilitation are required (Davies and Chandler Citation2012, 154; Friess and Eilders Citation2015, 326; Wright and Street Citation2007; Escobar Citation2019). Consequently, we wanted our cases to be facilitated with the aim of fostering quality deliberation.

One of the key platform features that affects online deliberation is whether it is synchronous or asynchronous (Davies and Chandler Citation2012; Friess and Eilders Citation2015). In order to ensure consistency, both our cases were synchronous. We also wanted our cases to be on the same issue, with a coronavirus focus, and data use seemed an ideal choice given the centrality of vast amounts of data in pandemic responses. Public controversies around data misuse or abuse have highlighted important delineations between legal mandate and social license (Carter, Laurie, and Dixon-Woods Citation2015; Shaw, Sethi, and Cassell Citation2020), typically leading to institutional commitments for greater public engagement to “restore” public trust.

Indeed, public health crises present a host of data governance issues necessitating public deliberation. Numerous data intensive technologies have been developed as part of pandemic response, each raising important questions around data sharing, collation, and use. Consider, for example, the privacy concerns sparked by contact tracing apps. There has been a lack of transparency and inclusion of public deliberation on questions of what types and how much data would be gathered, which organisations this would be shared with and on what basis and for how long. Research examining public attitudes and values in relation to health-related data practices consistently points to the value of public knowledge and the competence of public participants to meaningfully contribute to conversations in this field (Aitken et al. Citation2019; Jones et al. Citation2020).

The cases were organised by members of the research team, independently of each other and prior to the team forming. We do not seek to provide a systematic comparison of the cases. Rather, the inclusion of two cases from two nations provides us with more data to bolster the reliability of the findings, which was a key reason for having most similar cases. It enables us to provide evidence that our results are not idiosyncratic and peculiar to one case. An overview of both cases can be found in Table A in the Appendix.

Both case studies took place in May-July 2020 and were designed as public discussions on policies related to the pandemic. In England, Traverse, Ada Lovelace Institute, Involve and Bang the Table collaborated to deliberate COVID-19 exit strategies including the possible use of a contact tracing app. In Wales, online deliberative discussions were organised and facilitated by Population Data Science researchers at Swansea University in response to the rapid testing and proposed roll-out of a “track and trace” app amongst other COVID-related data collection and usage activities. By embracing digital platforms, both studies are examples of experimentation with citizen deliberation and participation in response to the crisis and therefore represent cases of public sphere resilience. Moreover, the organisers explicitly sought to respond to a lack of public involvement in policy development and implementation, aiming to demonstrate the potential for rapid engagement and influence policy through the public dissemination of findings. The cases are consequently collective endeavours to generate deliberative communication “that can be used to craft solutions to problems that the people involved did not know would occur” (Trenz et al. Citation2021, 3).

Both case studies recruited participants with the aim of achieving a cross-section of people who were unknown to each other. In England, participants were recruited through local community and mutual aid groups using adverts in local online group and message boards. Interested participants completed a short screening questionnaire that collected basic demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic group). The total sample across the two South East locations was broadly reflective of a cross-section of the English population in terms of ethnicity and socioeconomic groups, although slightly skewed towards female participants and the mid-age groups. To achieve this, the initial sample was stratified according to the population of England data via Office for National Statistics estimates. In total, 54 people expressed interest in participating across the two locations and 29 were selected to participate. All contributors were offered an honorarium for their time.

In Wales, participants were recruited from a May 2020 survey of the Welsh public (4500) that sought views on the proposed track and trace app (NHSX model). The sample was taken from the HealthWiseWales cohort (Hurt et al. Citation2019), oversampled for men and for ethnic minority identities as the cohort is majority white and female. Sixteen contributors were recruited from those (122) who had expressed interest following the anonymous survey. They were selected to ensure a mix of age, geographic location, ethnicity and gender as well as self-identified risk for COVID-19. All contributors were offered an honorarium for their time and the opportunity to co-author outputs and contribute to presentations.

Both cohorts were self-selecting in the sense that people actively expressed interest in deliberating issues related to COVID-19 policy. This means that participants were more likely to be comfortable deliberating in public online discussions with strangers than other members of the public, but there is no guarantee they would be more likely to exhibit the qualities that the Discourse Quality Index (DQI) measures (e.g. justification of demands or respecting demands). In each location, small discussion groups consisted of a mix of demographics and locations. Zoom was used because of its familiarity for the public and IT support was offered throughout.

In England, the final output of the deliberation was a set of principles that the participants think should shape the conditions under which a contact tracing app is introduced. These principles were identified through the analysis of the discussions by the project researchers and presented back to participants in the final session for agreement and discussion.

In Wales, participants received materials on Wales’ and UK responses to COVID-19 before Session 1 and further in written, audio and video form for Sessions 2 and 3. The online sessions ran with one facilitator for each small group plus technical support. Between discussions, participants reflected on the deliberation using a medium of their choosing. Adaptations were made during the process in response to participant feedback. Optional Zoom socials were hosted between Sessions 1 and 3 in order to provide an opportunity for unstructured interaction and support group cohesion. The initial output was a set of recommendations regarding the uses of COVID-19 during and beyond the crisis, created by participants throughout the process and refined by them in a final facilitated session.

In England, Traverse and Ada Lovelace Institute hosted webinars for policymakers and engagement practitioners to reflect on findings of the deliberation as well as the role of public deliberation in COVID-19 policymaking. In Wales, outputs include recommendations to Public Health Wales and Welsh Government, public-facing presentations and reporting to the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage Databank (SAIL) consumer panel.

Assessing Deliberative Quality

To assess deliberative quality, we used the DQI. This is a theoretically grounded instrument that enables researchers to quantitatively code the extent discussions meet deliberative criteria such as inclusion, reason-giving, focus on the common good, and respect. Each of these principles relates to a series of coding categories.

It originated from Habermasian discourse ethics and was initially applied to parliamentary debates (Jaramillo and Steiner Citation2019). While there are criticisms of the DQI method with respect to how well it can be applied to all contexts and the restricted notion of deliberation it adopts (Mendonça Citation2015; Jaramillo and Steiner Citation2019), we maintain that these can be overcome by adapting the coding framework. We agree with the original DQI creators that “wherever there is deliberation of some sort and there is a record, the DQI can be applied” (Steenbergen et al. Citation2003, 44). It is therefore a versatile method with general applicability and has been applied to a variety of contexts and consequently evolved in the process (Pedrini Citation2014; Davidson et al. Citation2017; Himmelroos Citation2017; Elstub and Pomatto Citation2018). Its application to the discussions from our two case studies enable us to assess the extent that deliberation occurred and to assess which deliberative norms were more and less prevalent.

To contextualise the coding framework to our cases, and research questions, we adopt developments in the coding framework made by other researchers. In the original DQI (Steenbergen et al. Citation2003), there was a distinction between “qualified” and “sophisticated” justifications of demands, depending on the number of reasons given for a demand. However, following other studies (Davidson et al. Citation2017; Marien, Goovaerts, and Elstub Citation2020), we accept that from a deliberative perspective, it is not necessarily superior to have more reasons for a demand, providing a reason is offered. Furthermore, we take the distinction between respect for “persons” and “demands” from Marien, Goovaerts, and Elstub (Citation2020), along with the coding of speech acts without demands with “non-justification” related codes. This means that each contribution, or speech act, from each participant in the discussion is coded, except for those from the facilitator. This is important, as we need to know whether other deliberative norms, such as pertinence and respect, are present even when a demand is not made.

From Bobbio (Citation2013), we adopt codes for pertinence and storytelling. The latter now widely acknowledged to be an important element of deliberation, not included in the original DQI, as it can help make discussions more inclusive of those with different communication styles (Young Citation2020). Yet we do expand the storytelling code to distinguish between pandemic related, and non-related, stories. Given that previous studies have found limited use in the original “participation” code (Davidson et al. Citation2017), where interruptions needed to be acknowledged by the speaker, we do not include this code. In our initial attempts at employing the DQI, we found the original “constructive politics” code unhelpful. This code was used to assess whether participants move away from their starting position on the issue and offer mediating proposals. However, in our cases, the participants did not enter the discussions with set positions to defend as politicians might in parliamentary debate but rather they developed their opinions through the discussion.

Given the focus of our study, we have also included a code for the presence of emotion and the extent this relates to the pandemic. While acknowledging that a fuller analysis of emotion would require visual and oral analysis of the discussions (Mendonça, Ercan, and Hans Citation2020), we found that coding of the transcripts in this way still provided useful and reliable data, noting that coders had been present during deliberations. This is the first attempt to expand the DQI to include emotion and to respond to critiques that the method relies on an overly formal conception of deliberation (Mendonça Citation2015).

Beyond these changes, we utilise the original DQI codes (Steenbergen et al. Citation2003). The full codebook can be found in Table B in the Appendix. The codebook is designed so that a higher score generally means more deliberative. As is common practice in DQI analysis, we treat each code separately rather than aggregating them into an overall score of deliberative quality. This is because not all deliberative norms carry equal credence (Davidson et al. Citation2017).

In both case studies, participants were divided into three small discussion groups. We coded transcripts of one small group discussion, for the entire process, from each case. This gave us a total sample of 260 speech acts. 144 from the Welsh case and 116 from the English case. There were three coders used and the application of codes was agreed in a collective and iterative process. In order to test for intercoder reliability 20% (59) of speech acts were triple coded to control for inter-coder agreement by chance. We calculated pairwise percentage agreement and Cohen’s kappa between coders. We also calculated the combined percentage agreement and Fleiss’s kappa to test for correlation amongst all three coders, the results of which are displayed in Tables C and D in the appendix. All scores are above the common thresholds for satisfactory reliability, with the majority fair to good or excellent levels of agreement.

The Qualities of Pandemic Digital Deliberation

In this section, we present our key findings and employ them to help address our research questions about the quality and resilience of pandemic digital deliberation. The descriptive statistics for each code, from our two cases, are displayed in .

TABLE 1 Percentage and median of DQI codes per category per country

Our first research question was whether members of the public would deliberate effectively online during the pandemic on a complex coronavirus-related issue such as data use. The results suggest that the quality of deliberation that took place in both of the forums is good in many respects, providing evidence of citizen communicative resilience in the pandemic. This suggests that the context of the pandemic provoked a participatory and deliberative response by the forum organisers and participants as they experimented with digital platforms and new forms of communication.

Firstly, we found that the vast majority of participant contributions were pertinent (81–96%), meaning they had direct relevance to the topic at hand. Secondly, we see high levels of respect amongst the participants to each other’s demands with less than 4% of demands being disrespected. In our cases, there were many instances (Case 1, 29% and Case 2, 13%) of explicit respect to demands. In this example, the second speaker explicitly respects the previous speaker’s demand and justification for a mandated contact tracing app, as public trust is too low for it to be used widely enough to be effective otherwise. Caused in part by the actions of the UK Prime Minister’s chief advisor Dominic Cummings, at the time (Bland Citation2020):

… we’re talking about an app that is voluntary. Unless it’s mandated by sanctions, such as denied access to certain locations or services, then I don’t see enough people using it. There is such a lack of trust that has been exacerbated in the last couple of days, the viability of the app has gone down because no one trusts the government. So the app won’t be effective. (Quote from Case 1, England)

That’s an extremely important point. That is what we’ve been missing, an integrated approach. Right now the government’s approach has been disconnected from the GP and existing systems. A really important point. At the very least, GPs know their patients. (Quote from Case 1, England, respects the demand of previous speaker and implicit demand for integrated approach)

I think B makes a good point, one of the problems we have with COVID is that we need to balance the nature of this disease and the nature of our response to it, with the need to continue as a society, to continue economically and so on. (Quote from Case 2, Wales, respects the previous speaker)

people will put up with a lot if it's fair and it feels like we’re all doing it together. That’s why the Cummings’ thing has had such an impact. TfL [Transport for London] have said it’s a good idea to wear masks on public transport and now 50% of people are doing so, but lots aren’t—how do you enforce it? An app can’t really be mandated so it can only be part of the solution. (Quote from Case 1, England)

I would only download it if I could get a test and feed in reliable information. Without proper testing we all run the risk of staying at home. We need a whole system approach and I have no confidence that this gov has a whole system approach in place. (Quote from Case 1, England, an explicit justification for demand for a systematic approach)

But I think we do need to find ways to behave as a society, coping with the parameters of this disease, if it’s going to be around for a while, it may need a big change in our behaviour but we need to achieve that whilst maintaining our ability to interact with people and our ability to conduct our life. (Quote from Case 2, Wales, focus on the common good)

I think the second thing is that we tend to think of our society … politicians tend to think our society is all the same, there’s a mainstream you can aim at and that’s it and our society’s incredibly diverse and we don’t actually consult. I think the classic case was the announcement was in Leicester, the day before Eid at 9 o'clock in the evening, sent out by Twitter. I mean how … disrespectful, inconsiderate was that? You know, people just switch off when they have those kind of things done to them. (Quote from Case 2, Wales, pandemic related story)

For each of these codes “Case 1 England” had a higher score for pertinence, respect towards demands, and storytelling. Whereas “Case 2 Wales” had a higher score for respect towards the person. There are many factors that could account for differing scores such as the differences in participant recruitment and facilitation styles, but it is beyond the remit of this paper to explore this. Crucial for our focus is that the differences are not so great as to negate the pattern outlined above. Neither are the differences significant in relation to the level of justification, level of generality of argument or pandemic emotion. Overall, there is no particular pattern to the differences that would undermine our evidence of deliberative experimentation, innovation and resilience.

The extent that the presence of pandemic emotion in the forums would inhibit deliberative quality was our final research question. The results, included in , demonstrate that there was, overall, infrequent emotional content in the deliberation with 94-95% of speech acts not displaying explicit emotion. When emotion was displayed it was most likely to be pandemic related. For example: “And that’s not surprising because I was out yesterday, people were coming up to me within a metre and talking to me, which was terrifying. I shan’t be going out again!” (Quote from Case 2, Wales, pandemic emotion).

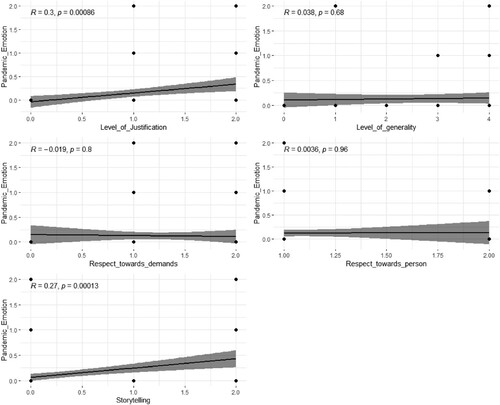

Fisher’s exact test and Cramer’s V were used to test for association and strength of association between pandemic emotion and the other deliberation codes indicated in Table F in the appendix. The results, and those in , suggest that the level of justification and storytelling were associated with pandemic emotion, implying the greater the presence of pandemic emotion, the more prevalent these deliberative norms and the higher the quality of deliberation.

FIGURE 1 Scatter plot and regression line for correlation between deliberative codes and pandemic emotion

For example, there were instances where emotion and justification were combined in the same speech act, such as this emotional, yet reasoned, demand for an immediate lockdown earlier in the pandemic:

I remember actually screaming, “Why don’t we lock down? Why don’t we close borders?”, I’m not moving and I haven’t moved since 12th March and I think a lot of people were feeling like that … so it was at that point I think we should have said to people, “this is coming, what do we want to gather?”, I think we’ve missed the boat – and the bus – and the train. (Quote from Case 2, Wales, pandemic emotion and qualified justification)

Conclusion

In times of crisis opportunities for meaningful citizen participation and deliberation are more important than ever. However, the UK Government’s approach to public policy in pandemic times seems based on the assumption that the public are there to be led rather than to be part of the deliberation about evidence, policy options and collective action. Political leaders in highly mediatised environments tend to pay more attention to the realm of public opinion than the realm of public reasoning. Whereas public opinion may be shaped by top-down communication, public reasoning must be enabled through deliberative public engagement. These are fundamentally different approaches to democratic governance, with substantial implications for addressing this and future crises (Fischer Citation2017). Our paper, which focused on online synchronous deliberation on data use and Coronavirus in two cases, demonstrates that despite the potentially more demanding conditions a pandemic presents for citizen deliberation, experimentation and innovation can occur. In our cases, deliberation was relocated online and was of a good quality indicating that organisers, facilitators and the public all developed new skills and capabilities and thereby “bouncing forward” in important ways.

For example, while the discussions in our cases were not particularly emotional, when participants did express emotion, this enhanced other deliberative norms. Emotions thus play a wide range of complex but crucial roles in public deliberation (Morrell Citation2010). For example, they underpin the empathy, care and solidarity that motivate people to be resilient and deliberate in the first place and offer other-regarding arguments along the process; they are essential in determining what is worthy of normative evaluation; and they play multiple communicative functions during deliberation while providing the motivation to act in its aftermath (Neblo Citation2020, 924–926). Emotions are therefore indispensable enablers of both reasoning and decision-making (Kahneman Citation2011).

We, therefore, conclude that governments should create more opportunities for public participation and deliberation as it continues to respond to COVID-19. In order to increase democratic legitimacy and the quality of policy these participatory and deliberative forums should feed into the pandemic policy process. Expediency is not a reasonable excuse for untrammelled executive powers because Covid-19 is not a strategic actor, such as a wartime foe, and thus there is no justification to forego transparency, engagement and accountability (Afsahi et al. Citation2020, ix). Moreover, as the case of Taiwan suggests, expediency and effectiveness can be aided by digital public engagement (Nabben Citation2020). Nevertheless, when such opportunities are not enabled by the government, the public sphere can generate opportunities for deliberative resilience.

Further research in this area is required to build on our findings. Other contextual variables are crucial to online deliberative quality, for example, the political system and the origin and type of digital platform (Santini and Carvalho Citation2019, 433). Where possible, a more holistic approach to assessing deliberative quality could be adopted that utilised visual and oral research methods (Mendonça, Ercan, and Hans Citation2020). Despite these limitations, our study is the first one to perform a comprehensive, systematic, and in-depth analysis of the deliberative capacity of ordinary citizens in a pandemic. The findings are relevant for other types of crises too. When they occur in the future, the public should not be marginalised from public policy but used to play a pivotal role in public reasoning. Deliberation can be resilient in the public sphere in times of crisis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable time and contributions of the online deliberation participants and subject experts in both case studies. Escobar’s contribution to this paper was supported by the Edinburgh Futures Institute.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2021.1969616.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stephen Elstub

Stephen Elstub (corresponding editor) is a Reader in British Politics in the Department of Politics at Newcastle University. Email: [email protected]

Rachel Thompson

Rachel Thompson is a Bioethics and Public Involvement Researcher in the Information Governance and Public Engagement (IG&PE) group, Population Data Science at Swansea University.

Oliver Escobar

Oliver Escobar is Senior Lecturer in Public Policy at the University of Edinburgh and Academic Lead on Democratic Innovation at the Edinburgh Futures Institute, Edinburgh University.

Joe Hollinghurst

Joe Hollinghurst is a Research Fellow at Swansea University.

Duncan Grimes

Duncan Grimes is a Senior Consultant at Traverse Ltd.

Mhairi Aitken

Mhairi Aitken is an Ethics Research Fellow in the Public Policy Programme of the Turing Institute, and Visiting Fellow at the Australian Centre for Health Engagement Evidence and Values (ACHEEV) at the University of Wollongong, Australia.

Anna McKeon

Anna Mckeon is Head of Engagement at Traverse Ltd.

Kerina H. Jones

Kerina Jones is Professor of Population Data Science at Swansea University.

Alexa Waud

Alexa Waud is a Researcher and Organiser based in London and director of Fuel Poverty Action, a grassroots campaign focused on energy, housing and social justice.

Nayha Sethi

Nayha Sethi is Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Edinburgh and Deputy Director of the Mason Institute for Life Sciences, Medicine and the Law, The Usher Institute, Edinburgh University.

REFERENCES

- Afsahi, Afsoun, Emily Beausoleil, Rikki Dean, Selen A. Ercan, and Jean-Paul Gagnon. 2020. “Democracy in a Global Emergency.” Democratic Theory 7: 5–19.

- Aitken, Mhairi, Sarah Cunningham-Burley, Amy Darlington, Stephen Elstub, Oliver Escobar, Kerina H. Jones, Naya Sethi, and Rachel Thompson. 2020. “Why the Public Need a Say in How Patient Data are Used for Covid-19 Responses.” International Journal of Population Data Science 5: 2.

- Aitken, Mhairi, Mary P. Tully, Carol Porteous, Simon Denegri, Sarah Cunningham-Burley, Natalie Banner, Corri Black et al. 2019. “Consensus Statement on Public Involvement and Engagement with Data-Intensive Health Research.” International Journal of Population Data Science 4 (1), https://doi.org/10.23889/ijpds.v4i1.586.

- Anckar, Carsten. 2008. “On the Applicability of the Most Similar Systems Design and the Most Different Systems Design in Comparative Research.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 11 (5): 389–401.

- Baek, Young Min, Magdalena Wojcieszak, and Michael X Delli Carpini. 2011. “Online Versus Face-to-Face Deliberation: Who? Why? What? With What Effects?” New Media and Society 14: 363–383.

- Bandes, Susan A. 2009. “Repellent Crimes and Rational Deliberation: Emotion and the Death Penalty.” Vermont Law Review 33 (3): 489–518.

- Bland, Archie. 2020. “The Cummings Effect: Study Finds Public Faith Was Lost after Aide's Trip. The Guardian, August 6, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/aug/06/the-cummings-effect-study-finds-public-faith-was-lost-after-aides-trip.

- Bobbio, Luigi. 2013. The Quality of the Deliberation. Rome: Carroci Editore.

- Brennan, Jason. 2016. Against Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Brown, Mark. 2014. “Expertise and Deliberative Democracy.” In Deliberative Democracy: Issues and Cases, edited by S. Elstub, and P. Mclaverty, 50–68. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Carter, Pam, Graeme T. Laurie, and Mary Dixon-Woods. 2015. “The Social Licence for Research: Why Care Data Ran Into Trouble.” Journal of Medical Ethics 41: 404–409.

- Celermajer, Danielle, and Dalia Nassar. 2020. “COVID and the Era of Emergencies.” Democratic Theory 7: 12–24.

- Davidson, Stewart, Stephen Elstub, Robert Johns, and Alastair Stark. 2017. “Rating the Debates: The 2010 UK Party Leaders Debates and the Deliberative System.” British Politics 12 (2): 183–208.

- Davies, Todd, and Reid Chandler. 2012. “Online Deliberation Design: Choices, Criteria and Evidence.” In Democracy in Motion: Evaluating the Practice and Impact of Deliberative Civic Engagement, edited by T. Nabatchi, J. Gastril, G. M. Weiksner, and M. Leighninger, 103–131. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Elstub, Stephen, Sarah Liu, and Maarja Luhiste. 2020. “Coronavirus and Representative Democracy.” Representation 56 (4): 431–434.

- Elstub, Stephen, and Gianfranco Pomatto. 2018. “Mini-Publics and Deliberative Constitutionalism.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Deliberative Constitutionalism, edited by J. King, H. Kong, and R. Levy, 295–310. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ercan, Selen A., and Jean-Paul Gagnon. 2014. “The Crisis of Democracy.” Democratic Theory 1: 1–10.

- Escobar, Oliver. 2011. “Suspending Disbelief: Obama and the Role of Emotions in Political Communication.” In Politics and Emotions: The Obama Phenomenon, edited by M. Engelken-Jorge, P. Ibarra Güell, and C. Moreno Del Río, 109–128. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

- Escobar, Oliver. 2019. “Facilitators: The Micropolitics of Public Participation and Deliberation.” In The Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by S. Elstub, and O. Escobar, 178–195. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Escobar, Oliver, and Stephen Elstub. 2019. “The Field of Democratic Innovation.” In The Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by S. Elstub, and O. Escobar, 1–9. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Fischer, Frank. 2012. “Participatory Governance: From Theory to Practice.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance, edited by D. Levi-Faur, 457–471. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fischer, Frank. 2017. Climate Crisis and the Democratic Prospect. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Flinders, Matthew. 2020. “Democracy and the Politics of Coronavirus: Trust, Blame and Understanding.” Parliamentary Affairs 74: 483–502. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsaa013.

- Foa, Roberto Stefan, Andrew Klassen, Michael Slade, Alex Rand, and Rosie Williams. 2020. Global Satisfaction with Democracy. Cambridge: Bennett Institute for Public Policy, University of Cambridge.

- Friess, Dennis, and Christiane Eilders. 2015. “A Systematic Review of Online Deliberation Research.” Policy and Internet 7: 319–339.

- Gaskell, Jennifer, and Gerry Stoker. 2020. “Centralized or Decentralized.” Democratic Theory 7: 33–40.

- Himmelroos, Staffan. 2017. “Discourse Quality in Deliberative Citizen Forums: A Comparison of Four Deliberative Mini-Publics.” Journal of Public Deliberation 13 (1): 1–28.

- Hurt, Lisa, Pauline Ashfield-Watt, Julia Townson, Luke Heslop, Lauren Copeland, Mark D. Atkinson, Jeffrey Horton, and Shantini Paranjothy. 2019. “Cohort Profile: HealthWise Wales. A Research Register and Population Health Data Platform with Linkage to National Health Service Data Sets in Wales.” BMJ Open 9: e031705. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031705.

- Involve. 2020. Deliberative Democracy in the Age of COVID-19: Practitioners Online Workshop – Summary Report of Key Themes. London: Involve.

- Jaramillo, Maria Clara, and Jürg Steiner. 2019. “From Discourse Quality Index to Deliberative Transformative Moments.” In The Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by S. Elstub, and O. Escobar, 527–539. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Jones, Kerina, Helen Daniels, Sharon M. Heys, Arron S. Lacey, and David V. Ford. 2020. “Towards a Risk-Utility Data Governance Framework for Research Using Genomic and Phenotypic Data in Safe Havens: Multifaceted Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (5): e16346. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/16346.

- Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking Fast and Slow. London: Penguin.

- Kavanagh, Matthew M., and Renu Singh. 2020. “Democracy, Capacity, and Coercion in Pandemic Response. COVID 19 in Comparative Political Perspective.” Journal Health Politics.” Policy and Law 45 (6): 8641530. https://doi-org.libproxy.ncl.ac.uk/10.1215/03616878-8641530.

- Kennedy, Ryan, Anand E. Sokhey, Claire Abernathy, Kevin M. Esterling, David M. Lazer, Amy Lee, William Minozzi, and Michael A. Neblo. 2020. “Demographics and (Equal?) Voice: Assessing Participation in Online Deliberative Sessions.” Political Studies, doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719890805.

- Landemore, Hélène. 2012. Democratic Reason: Politics, Collective Intelligence, and the Rule of the Many. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lavazza, Andrea, and Mirko Farina. 2020. “The Role of Experts in the Covid-19 Pandemic and the Limits of Their Epistemic Authority in Democracy.” Frontiers in Public Health 8: 356. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00356.

- Mahoney, James, and Gary Goertz. 2006. “A Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research.” Political Analysis 14: 227–249.

- Marien, Sofie, Ine Goovaerts, and Stephen Elstub. 2020. “Deliberative Qualities in Televised Election Debates: the Influence of the Electoral System and Populism.” West European Politics 43 (6): 1262–1284.

- Mendonça, Ricardo F. 2015. “Assessing Some Measures of Online Deliberation.” Brazilian Political Science Review 9 (3): 88–115.

- Mendonça, Ricardo F., Selen A. Ercan, and Asenbaum, H. Hans. 2020. “More Than Words: A Multidimensional Approach to Deliberative Democracy.” Political Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720950561.

- Morrell, Michael E. 2010. Empathy and Democracy: Feeling, Thinking, and Deliberation. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Mouter, Niek, Jose Ignacio Hernandez, and Anatol Valerian Itten. 2021. “Public Participation in Crisis Policymaking.” PloS One 16 (5): e0250614.

- Nabben, Kelsie. 2020. “Hacking the Pandemic: How Taiwans Digital Democracy Holds COVID-19 at Bay.” The Conversation, 11 September.

- Neblo, Michael A. 2020. “Impassioned Democracy: The Roles of Emotion in Deliberative Theory.” American Political Science Review 114 (3): 1–5.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2001. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Parry, Lucy J., Hans Asenbaum, and Selen A. Ercan. 2020. “Democracy in Flux: A Systemic View on the Impact of COVID-19.” Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 15 (2): 197–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-09-2020-0269.

- Pedrini, Seraina. 2014. “Deliberative Capacity in the Political and Civic Ssphere.” Swiss Political Science Review 20 (2): 263–286.

- Runciman, David. 2015. The Confidence Trap: A History of Democracy in Crisis from World War I to the Present. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Russon-Gilman, Hollie, and Tiago Peixoto. 2019. “Digital Participation.” In The Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by S. Elstub, and O. Escobar, 105–118. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar.

- Saam, Nicole J. 2018. “Recognizing the Emotion Work in Deliberation. Why Emotions Do Not Make Deliberative Democracy More Democratic.” Political Psychology 39 (4): 755–774.

- Santini, Rose M., and Hanna Carvalho. 2019. “The Rise of Participatory Despotism: A Systematic Review of Online Platforms for Political Engagement.” Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society 17: 422–437.

- Shaw, James, Nayha Sethi, and Christine Cassell. 2020. “Social Licence for the Use of Big Data in the COVID-19 Era.” npj Digital Medicine 3: 128.

- Sibony, Anne-Lise. 2020. “The UK COVID-19 Response: A Behavioural Irony?” European Journal of Risk Regulation 11 (2): 350–357.

- Steenbergen, Marco R., André M. Bächtiger, Markus Sporndli, and Jürg Steiner. 2003. “Measuring Political Deliberation: A Discourse Quality Index.” Comparative European Politics 1 (1): 21–48.

- Strandberg, Kim, and Kimmo Grönlund. 2018. “Online Deliberation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, edited by A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, and M. E. Warren, 1st ed., 365–377. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stromer-Galley, Jennifer, Lauren Bryant, and Bruce Bimber. 2015. “Context and Medium Matter: Expressing Disagreements Online and Face-to-Face in Political Deliberations.” Journal of Public Deliberation 11: 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.218.

- SURF. 2020. Covid 19: Lessons from the Frontline. Glasgow: Scottish Urban Regeneration Forum.

- Toshkov, Dimiter. 2016. Research Design in Political Science. London: Palgrave.

- Towne, W. Ben, and James D. Herbsleb. 2012. “Design Considerations for Online Deliberation Systems.” Journal of Information Technology and Politics 9: 97–115.

- Trenz, Hans-Jörg, Annett Heft, Michael Vaughan, and Barbara Pfetsch. 2020. “Resilience of Public Spheres in a Global Health Crisis.” Weizembaum Series 11: 1–29. Berlin: Weizenbaum Institute for the Network Society.

- Trenz, Hans-Jörg, Annett Heft, Michael Vaughan, and Barbara Pfetsch. 2021. “Resilience of Public Spheres in a Global Health Crisis.” Javnost – The Public 11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2021.1919385.

- Weible, Christopher M., Daniel Nohrstedt, Paul Cairney, David P. Carter, Deserai A. Crow, Anna P. Durnová, Tanya Heikkila, Karin Ingold, Allan McConnell, and Diane Stone. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Policy Sciences: Initial Reactions and Perspectives.” Policy Sciences 53 (2): 225–241.

- Wright, Scott, and John Street. 2007. “Democracy, Deliberation and Design: The Case of Online Discussion Forums.” New Media and Society 9: 849–869.

- Yin, Robert K. 2014. Case Study Research Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Young, Iris Marion. 2000. Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.