Abstract

This article discusses the dominant metaphor of infodemic, the role of platforms and their policies. In understanding the spread of Covid-19 misinformation as an informational epidemic, we are led to construct the problem as one of viral spread. Virality, however, has been conceptualised as a key attribute of social media platforms. A tension therefore emerges between to encouraging good virality while limiting bad virality. To examine how platforms have dealt with this , the article analyses the policies of two platforms, Facebook and YouTube, alongside the EU Code of Practice which they have both signed. The analysis reveals that they focus on the circulation of mis/disinformation, developing an apparatus of security around it. This consists of a set of strategies, techno-material tools for the enforcement of the strategies, measures for disciplining users, and procedures for legitimating and re-adjusting the whole apparatus. However, this apparatus is not fit for the purpose of addressing mis/disinformation for two reasons: firstly, its primary objective is to sustain the platforms and not to resolve the problem of mis/disinformation; secondly it obscures the question of production of mis/disinformation. Ultimately, addressing mis/disinformation in a comprehensive manner requires a more thorough and critical social inquiry.

Introduction

The emergence of false, misleading, unsubstantiated information and rumours about Covid-19 was almost immediately discussed as an infodemic. The Director-General of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus referred to the infodemic as early as mid-February 2020, weeks before the formal declaration of a pandemic on 11 March 2020, and the UN Secretary General Antonio Gutierrez used the term in a much quoted tweet on 28 March 2020 (UN Citation2020). An infodemic is defined as an overabundance of information, with varying degrees of accuracy, which makes it difficult for citizens to identify trustworthy sources and reliable guidance (WHO Citation2020). Infodemics are directly linked to digital platforms and social media, which are at the epicentre of this whirlwind of misinformation, rumours and opinions. The decision of the WHO and the UN to approach this phenomenon as an infodemic highlighted the role of information and communication during and on the pandemic, while also, through a metaphor that alludes to the viral spread of information, it made a direct connection between the virus and (mis/dis)information. The politicisation and purposeful development of false information about the virus by actors who have political interests in this area is referred to as disinformation (Wardle Citation2018).

In her well-known work Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag (Citation1978) makes the point that illness is understood through certain metaphors, such as a secret invasion by an evil invincible predator, as is the case for imagining cancer. These metaphors, she argues, and more broadly the way we speak about disease informs the treatment of both the disease and the patient. Such metaphors, and narratives around them, link the disease with the character of the patient and more broadly with the moral character of the social body. Sontag (Citation1978, 41) refers to Thucydides description of the disorder and lawlessness following the plague of 430 BC in Athens, and Boccacio’s description of the Florentine plague of 1348 begins with references to the bad behaviour of citizens—moral corruption always accompanies physical deterioration of the social body and the connections are made in the language used to understand disease. While Sontag’s focus is on how metaphors obscure rather than elucidate the experience of illness, her work is instructive of the close links between illness and discourse, and the ways in which one is used to understand the other. From this point of view, understanding misinformation during a pandemic through the metaphor of infodemic, means that we are led to understand it as another form of global viral spread.

Thinking of information virality is not a new approach for apprehending communication on digital platforms. Indeed, not long ago, virality was seen as a desirable attribute and much effort was put into achieving it. Buzzfeed’s CEO, Jonah Peretti, popularised his views on viral communication by highlighting the importance of sharing contents for people as a means of connecting with others (Watts, Peretti, and Frumin Citation2007). Henry Jenkins and his collaborators made the argument that digital platforms are there for spreading contents—this “spreadability” (Jenkins, Ford, and Green Citation2013) or “scalability” of contents among networked publics (Boyd Citation2010) is seen as a fundamental attribute of social media. When it comes to misinformation, rumours and other forms of problematic information, however, this virality becomes a liability and platforms are pressured to act against it. Given, however, the ways in which digital platforms are conceived as spaces for connectivity (van Dijck Citation2013), there are questions regarding their capacity to effectively regulate against their own defining feature. As it will be shown, to address the tension between the need for shareability and the need to control some kinds of information, platforms have turned to controlling the circulation of contents justified on the bases of security and have developed an apparatus of control based on these.

The present article, therefore, poses the question of how platforms regulate misinformation and other elements of the infodemic and seeks to understand the ideological backdrop of their approach alongside the material apparatus they have designed. Since platforms operate within specific regulatory environments, national or supranational, such as the EU, it is also important to identify how specific regulatory environments approach the question of misinformation. Ultimately, the focus is on identifying how “bad viral information” is conceived and managed, and what the implications of this conception might be for publics in the pandemic and for the post-pandemic era. Moreover, given the closeness between discourse and illness, it is important to pay closer attention to the metaphors used to understand misinformation as a form of illness, which in itself as Sontag suggests reveals more about the social body than about the nature of the illness itself.

The article begins with a discussion of virality in digital communication (Jenkins, Ford, and Green Citation2013; Shifman Citation2014) and the links between virality and platforms (van Dijck Citation2013), followed by a discussion of misinformation and regulation. It then proceeds with a critical reading of the platform policies, focusing on the two largest platforms, Facebook and YouTube, along with a discussion of the EC Code of Practice on Disinformation. The analysis identifies the main perspective on mis/disinformation as a form of bad viral communication that needs to be removed from circulation before it “infects” more people, accompanied by a techno-material apparatus that is conceived in terms of product solutions such as informational labels with clickable links, algorithmic reordering of visibility, and the creation of informational centres. In approaching the issue in this manner, both platforms and regulations around misinformation preclude new ways of understanding and dealing with inaccurate information, rumours, and the information excess that accompanies the pandemic. This is because, echoing Sontag’s discussion, the dominant view is that misinformation “infections” are individual events and reflect the moral character of the “infected” person. Ultimately, we find that the medical metaphor makes a moral judgement addressing individual users and not the public as a whole, in contrast to an understanding of the phenomenon as affecting society and then reaching individuals as a form of dislocation. As I will try to show, the “infodemic” view reflects a neoliberal approach of responsibilisation and technical efficiency, intervening at the level of circulation of misinformation, at the expense of potential alternatives such as a focus on the social, political and cultural conditions under which misinformation gets produced and shared.

Digital Communication, Platforms and Virality

“If it doesn’t spread, it’s dead,” is the fundamental message of Jenkins, Ford and Green’s book Spreadable Media (Citation2013). For Jenkins et al., the spreadability of the contents on social media reflects, on the one hand, the affordances of the platforms and on the other the agency of users who decide whether to share something or not. Spreadable media builds upon the arguments on memes and viral communication that spread through contagion (Shifman Citation2014) but takes them further by highlighting the agency of users in the process. Digital platforms are not incidental in this process but underpinned by a specific business model that relies on creating connections between people through which content is created and circulates (van Dijck Citation2013). While these authors discuss somewhat different but overlapping constructs, such as virality, spreadability, memes and connectivity, they all have in common an understanding of these as defining characteristics of platforms. In considering these arguments in more detail, this section identifies the inextricable relationship between content creation, shareability and spreading and platform affordances and political economy. In short, I argue here that platforms cannot operate without user contents circulating more or less freely.

The virality metaphor is mostly found in writing on digital marketing and it follows closely the epidemiological model of viral spread. The key idea behind content virality is that it begins with a small “seed,” or a person or group of people who begin sharing contents with their friends. They would be the “patient zero” in this analogy, or the source of the “infection.” In the simplest case,

transmission occurs with some constant probability β. If each person spreads the word to z others, on average, then the expected number of new converts generated by each existing one is R = βz, which is called the “reproduction rate” in simple epidemiological models. (Watts, Peretti, and Frumin Citation2007, 3)

What makes people share? Here, Jenkins et al.’s (Citation2013) idea of spreadability is instructive. Jenkins et al argue that spreadability involves the decision to share and as such, it is not merely contagion. This decision reflects the agency of sharers while this agency is also reflected in the message that gets shared. For Jenkins et al. the metaphor of virality implies a kind of automatic replicability that is not what is happening on platforms. Viral communication as conceived by thinkers such as Douglas Rushkoff (Citation1996) tends to focus on the “stickiness” of the message, which then people feel compelled to share with others. For Rushkoff, the “media virus” enters people’s minds in a surreptitious manner because it is encoded in a form they cannot resist. As such, it infects them in much the same way as a pathogen. In contrast, Jenkins et al. propose the term spreadability and spreadable media in order to emphasise the activity of users themselves not only in distributing contents but also in shaping these contents and their circulation. Users can do this through repurposing and occasionally transforming contents, adding or removing elements, and in so doing they add value and allow the contents to spread further by localising them for diverse contexts (Jenkins, Ford, and Green Citation2013). It is not the purity of the message therefore but its adaptability that makes it spreadable because it allows users to exercise their agency and therefore enables them to meaningfully engage in culture creation.

This adaptability, in turn, is a crucial attribute of memes that constitute one of the principal forms of social media communication. The term famously comes from Richard Dawkins ([Citation1976] Citation2014), who used it to refer a unit of cultural information that propagates through imitation. In Dawkins’ original formulation, memes carry information, are replicated and transmitted through people using them, and they can also evolve, transform and mutate, in ways analogous to those of biological genes. In her analysis of internet memes, Shifman (Citation2014) discusses the underlying model of communication as transmission found in much of the research on viral contents compared with the implied model of communication as ritual found in analyses of memes. Both models of communication, she argues, are important if we are to understand what moves people to share contents and what moves them to engage creatively with them. Shifman’s analysis echoes that of Jenkins and his collaborators on the positive and participatory potential of engagement through memes and other forms of “spreadable” communication. In a positive evaluation of memes, Shifman views them as agents for political change, moving people who may have been alienated by formal political communication to participate in the political sphere through the playful form of memes. Memes, she argues, can represent a form of “user-generated globalization,” as they are adapted to different localities and cultures, translated in different languages, and distributed globally by users (Shifman Citation2104, 155).

While Jenkins et al. and Shifman focus on the agency of users and their active involvement in both the creation of meaning and its transmission and distribution, van Dijck (Citation2013) writing at the same period contextualised user practices in terms of the structures that shape them, focusing on technological affordances and the political economy of platforms. In particular, van Dijck referred to connectivity as a key socio-technical affordance of digital platofrms; connectivity is the attribute of platforms that links content to user activities and user activities to advertisers (van Dijck Citation2013; van Dijck and Poell Citation2013). User agency, according to van Dijck, is only part of the picture: this also includes platforms, and the political economy of platforms. Since the main revenue source for platforms is advertising in the form of directly targeting user-consumers on the basis of their interests and preferences, platforms have a strong incentive to encourage users to like, share, comment, and post information. Their whole design revolves around this. For example, Gerlitz and Helmond (Citation2013) identified the ways in which Facebook created the so-called social buttons such as like and share as a means by which to translate user activity, both inside and outside the platform, into metrics that can measure, track, multiply and trade activity turned into data.

The design of platforms is therefore an important parameter in shaping the messages that circulate, the form they take, and their reach. As van Dijck (Citation2013) points out, technological design features such as reaction buttons provide a feedback loop, which reinforces certain kinds of user behaviour while discouraging others. For instance, liked videos on YouTube rank higher in searches, a much favourited tweet may be trending, a much followed person on Instagram is more likely to be recommended to users and so on. These are means by which platform design steers user behaviour in specific ways. Sociality in the context of digital platforms is therefore engineered in ways that maximise the currency that platforms require: user data.

Viral, memetic and spreadable communication therefore is not only a result of the resonance of contents or user agency but a complex interaction between political economic factors, technological affordances designed by the platforms, content features and user agency. This type of communication can be used by marketing campaigns, but ultimately relies on users and their willingness to contribute to spreading messages. This however does not occur in a level playing field or neutral domain, but on platforms whose design revolves around encouraging users to engage in content creation and sharing. When most of these works were published the general zeitgeist was overall positive regarding social media and their role in processes of political mobilisation and democratic communication. However, the climate changed drastically around 2016, when information manipulation and “fake news” rose to prominence.

Virality, Misinformation and Regulation

While misinformation was always present (cf. James and Aspray Citation2019), global discussion on it exploded in 2016 after two key political developments: the Brexit referendum in the UK and the electoral campaign of Donald Trump. The identification of clearly false stories circulating unchecked on platforms combined with microtargeting political marketing tactics led to calls for more regulation of social media contents (Dommett Citation2019). The Cambridge Analytica scandal reveal the possibility of manipulation through accessing personal data and information on users, therefore mobilising targeted misinformation (Cadwalladr and Emma Graham-Harrison Citation2018). As a result, both misinformation, as the spread of factually wrong and misleading information, and disinformation, or the purposeful spread of false and misleading information for economic, political or ideological gain, were placed at the centre of public discussions (Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017). In their work, Culloty and Suiter (Citation2021) propose a framework that includes actors, platforms, audiences and countermeasures, as a means by which to understand disinformation comprehensively. Their discussion incorporates a wide range of factors, including cognitive, social, technological and political, arguing that all these combine to create a fertile ground for disinformation to flourish. Going through each of these levels, it becomes evident that they can be seen as the negative counterpart to the earlier discussions on virality.

Thus, bad actors and their political, economic and ideological motivations are the negative form of the civically motivated or altruistic content creators of the early, pre-2016 phase, for example during the Arab Spring. There, organised communicators or hubs were seen as emerging from the bottom up as coordinators of political action representing a new form of politics for networked publics, along with new kinds of political contents, revolving around affect, personal experiences, and connecting to others (Gerbaudo Citation2012; Bennett and Segerberg Citation2013; Papacharissi Citation2015). The affective contents that circulated widely in various events, from Tahrir to Gezi Park, moved people to political action because they found themselves identifying with them or being part of the story, as Papacharissi (Citation2015) put it. The response of state authorities to the various uprisings in the early 2010s was swift: Egypt now has one of the strictest regulations of social media platforms with users regularly prosecuted for contents seen as “fake news” (Siapera and Mohty Citation2020) while in Turkey, censorship and self censorship are widely used to silence dissent in social media (Çarkoğlu and Simge Andı Citation2021). In liberal democracies where misinformation is seen to represent a threat to democracy (Schia and Gjesvik Citation2020), regulation of contents has been much more light touch.

In particular, platforms have notoriously been offered a safe harbour approach to regulation whereby they are not seen as content creators or editors and are therefore not responsible for the contents they host (Gillespie Citation2018). This is the case both in the US and the European Union, whose platform regulation is primarily undertaken through the E-Commerce Directive of 2000, which is currently being replaced by the Digital Services Package. In this Directive, the internet was still under development, and it was perceived that heavy regulation might hinder its growth. To avoid this, the Directive included three exceptions for liability for sites that are “mere conduits,” hosting or caching contents. In this manner, platforms were exempted from any liability for contents they host. While platforms eventually developed their own self regulatory mechanisms to deal with problematic contents, including misinformation, they are not subjected to any regulation in the same manner as other media, print, broadcast or digital news sites.

Users, on their side, are often discussed in dichotomous terms, either as passive recipients vulnerable to manipulation or as active citizens willing and able to navigate complex media terrains (Siapera, Niamh Kirk, and Doyle Citation2019). Discussions of cognitive biases and susceptibilities to misinformation have turned the focus on user’s psychological and cognitive make up and located corrective measures at this level (Lewandowsky et al. Citation2012). Such corrective measures include the process of inoculation, which Lewandowski and van der Linden (Citation2021) understand as a form of pre-emptive refutation of anticipated misleading arguments. As with the vaccination process against pathogens, inoculation against misinformation works by exposing users to small quantities of misinformation, which allow them to develop the necessary cognitive skills to resist future attempts to misinform. This process operates at the cognitive level and is meant to be content agnostic: it focuses on creating a resistance to persuasive messages and not on addressing either the contents or the process that gave rise to these contents in the first place. The provision of fact checks by news outlets operate on a similar premise: upon seeing the corrections, people will act as rational information processors and correct their mistakes.

In other user or audience studies, the social environment of users, the communities they belong to and the ways in which they domesticate and use technologies and media have been seen as crucial factors for the reception and interpretation of media messages (Silverstone Citation2017; Siapera, Niamh Kirk, and Doyle Citation2019). Regulation must therefore reflect the embeddedness of individuals in communities but this does not seem to be the case in existing regulatory approaches. Current regulation on users/audiences in the European Union is undertaken primarily through the various iterations of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (European Commission Citation2019) which oscillate between vulnerable audiences in need of protection, especially in terms of advertising and misleading contents in the media; and empowered audiences, in charge of their own informational needs, who are expected to be responsible media users. The tension between these positions is resolved through a shift to media literacy. Media literacy is defined as “skills, knowledge and understanding that allow citizens to use media effectively and safely” and the Directive expects that platforms “promote the development of media literacy in all sections of society” (European Commission Citation2019, unpaginated).

The dichotomous thinking around platforms and misinformation reveals tensions between perceptions of good and bad platforms, which either promote democracy as in the Arab Spring discussions or undermine democracy as in the Brexit-Trump-Cambridge Analytica discussions. Similarly, users-audiences are understood as either passive or active cognitive information processors, and measures to support them take the form of providing extra skills at the individual level. The inoculation metaphor is instructive here: although it rests on the early work of McGuire (Citation1970) it constructs misinformation as a case where “herd immunity” is built by vaccinating individuals until the transmission of the pathogen is no longer possible. As Lewandowsky and van der Linden put it, “[i]f enough individuals in a population are vaccinated, the informational virus has no opportunity to take hold and spread” (Citation2021: non-paginated). Despite therefore the recognition by van Dijk (Citation2013) and many others, including Lewandowski and his colleagues (Citation2020), that platforms create an environment that is not only conducive but actively pushes users towards sharing misinformation and virality, the preferred approach is still to allow platforms to mainly self regulate. The question that arises concerns the form that self regulation takes given the central tension we identified here: the co-existence of platforms’ defining characteristic of shareability with the requirement to control and limit this shareability. The next section discusses in more detail the self-regulatory policies of platforms and how the two largest platforms, Facebook (2.85 billion users) and YouTube (2.29 billion users),Footnote1 have addressed this tension.

Platform Self Regulation and Governance of Misinformation

How and why do platforms self regulate? Gillespie (Citation2018) argued that platforms are not expected to regulate because of “safe harbour” provisions that protect them from liability. They are however moved to self regulate because the environment they create for their users is part of what they “sell” to them. In other words, they are moved to curate their environments in ways that maximise the likelihood of attracting and keeping users engaged in the platform. These attempts to self regulate and moderate contents that appear on platforms emerged through a trial and error dynamic process, responding to developments on the ground. Early attempts to moderate contents for example show a focus on user safety and the emergence of reporting mechanisms for users to flag inappropriate contents (Cartes 2016 quoted in Viejo-Otero Citation2021). Given the rise of problematic contents, including mis/disinformation and hate speech, platforms developed more elaborate and comprehensive approaches. These are captured in the “Community Guidelines” for YouTube and “Community Standards” for Facebook. Based on a critical reading of these materials, alongside other publicly available information on these platforms’ mis/disinformation policy, as well as a critical reading of the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation, this section argues that platform interventions are primarily focused on the circulation of contents. These interventions are understood as part of an increasingly sophisticated apparatus of security, which is developed and deployed in order to govern platforms and the contents that circulate therein. For pandemic-related mis/disinformation this means that it is turned into a question of security, mainly concerned with the technical problem of removal or management of its circulation. The medical metaphor of infodemic and misinformation as virus is here turned into a security question of harm, risk, and discipline. This focus of platform self regulation on the process of circulation and individual discipline precludes any focus on the process of production of misinformation as reflecting a broader social pathology.

Misinformation Policies and Covid-19 on Facebook and YouTube

Both Facebook and YouTube have clear and elaborate policies on misinformation on Covid-19 and the vaccination programme. Both platforms justify their policies on the basis of safety, and integrity/authenticity. Facebook offers more details and justification for its policies, and in particular articulates a clear set of values behind them. “Voice” is the absolute value for Facebook, which has developed its Community Standards in order “to create a place for expression and give people a voice. The Facebook company wants people to be able to talk openly about the issues that matter to them, even if some may disagree or find them objectionable.Footnote2” Any limits placed on “voice” therefore are justified on the basis of four other values: authenticity, safety, privacy and dignity. Facebook nests its general misinformation policies under “Integrity and Authenticity,” and refers to the category as “false news,” as shown in the screenshot below ():

Figure 1. Facebook community standards, integrity and authenticity. Source: https://transparency.fb.com/policies/community-standards/

Facebook addresses misinformation specifically under the category Features (see ) and it is applying its three pronged policy on harmful or objectionable contents: remove, reduce, inform. In particular, Facebook removes false information that can cause physical harm, entirely removing certain false claims on Covid-19 and vaccines, along with information that interferes with voting and manipulated false content, for example deep fakes. Facebook has published a list of Covid-19 related claims that it removes from its platform, based on two factors: that the claims are false and that they are likely to cause violence or physical harm according to public authorities.Footnote3 When it comes to reduction, Facebook reduces the distribution of certain contents and does not show them on people’s newsfeeds. The contents that are demoted in this way are those which are not part of the list of prohibited claims on Covid-19, but which are found to contain false information by fact checkers that collaborate with Facebook. Finally, Facebook applies labels, notifications and educational pop-ups on content related to Covid-19, with the objective to connect people to reliable information (Clegg Citation2020) as shown on .

FIGURE 2. Facebook’s remove, reduce, inform policies. Source: https://transparency.fb.com/features/approach-to-misinformation/

In addition to notifications, Facebook has set up a Covid-19 information centreFootnote4 that presents users with reliable sources of information globally and nationally, for example, the WHO, the NHS in the UK, the CDC in the US, HSE in Ireland and so on. The information centre offers up to date statistics and posts from official sources on Covid-19 related developments, while it also offers tips and resources on emotional health and domestic abuse. Finally, while any user can report content that violates Facebook’s policies on misinformation, and this is then examined by human content moderators, it has also automated these processes and uses them at scale by deploying AI systems, such as SimSearchNet++, which identify and remove, demote and label posts (Facebook Citation2020).

While YouTube does not elaborate much on its key values, it is evident that its policies on misinformation are guided by the principle of safety and harm prevention:

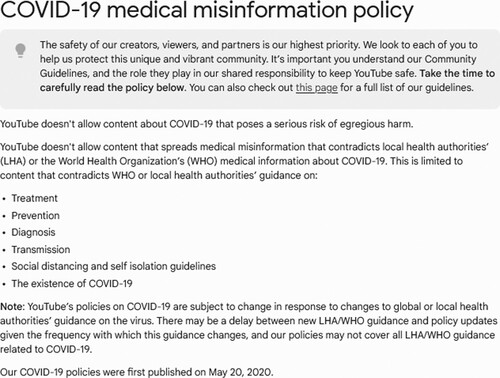

Certain types of misleading or deceptive content with serious risk of egregious harm are not allowed on YouTube. This includes certain types of misinformation that can cause real-world harm, like promoting harmful remedies or treatments, certain types of technically manipulated content, or content interfering with democratic processes.Footnote5

FIGURE 4. YouTube's Covid-19 misinformation policies, available at: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/9891785?hl=en

YouTube publishes a long list of contents it prohibits, offering detailed examples and making clear which types are to be removed. Borderline content, defined as content that “brushes up against our policies, but doesn’t quite cross the line,” gets demoted, as it does not appear in the video recommendations selected by YouTube’s algorithm. Conversely, the algorithms raises content that belongs to authoritative sources through their recommendation algorithm. YouTube also raises authoritative voices by offering informational resources through the “information panel” labelling system (see ) which appears next to content relevant to Covid-19.

Additionally, both platforms have formulated penalties for those in breach of the rules. Facebook operates a “strike” system, where violations are ranked on the basis of severity and then count as strikes. Penalties range from a simple warning to restricting access to altogether disabling accounts.Footnote8 YouTube uses a very similar system with strikes, but applies more severe penalties quicker, since 3 strikes in 90 days will get a channel terminated.Footnote9

The policies employed by these platforms are very similar as they derive from their voluntary participation in the EC Code of Practice for Disinformation.Footnote10 The Code is signed by online platforms, social networks, advertisers and the advertising industry, and all signatories have agreed to follow certain self regulatory standards. These include measures to limit and remove mis and disinformation; promote authoritative sources of information; enhance collaborations with fact checkers and journalists; and support and fund media literacy initiatives. The Code further requires systematic monitoring of these efforts and amendments when necessary. The monitoring consists of self assessments by platforms, mostly offering various metrics on how many pieces of contents were removed, on user engagement with authoritative information sources, and on how much was invested in fact checking, media literacy initiatives and related actions.Footnote11

The Code and its signatories adopt the definition of disinformation proposed by the High Level Expert Group on disinformation, which refers to it as “verifiably false or misleading information” which “may cause harm” (European Commission Citation2018, 2). The Code is then exclusively concerned with identifying the various actions that the platforms and other signatories commit to undertake in order to address the challenges of disinformation. Any measures must be proportional, taking into account the rights of citizens as expressed in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the European Convention of Human Rights.

For both the European Commission and platforms therefore the problem of mis/disinformation is a technical problem, firstly of identifying this kind of information and then removing it or diluting its visibility, thereby preventing its spread and diminishing its potential to cause harm. In parallel, the Code seeks to empower users “with tools enabling a customized and interactive online experience” (European Commission Citation2018, 3) and platforms oblige through clickable labelling systems, information hubs, and reporting buttons.

Controlling Circulation: An Apparatus of Security

This alignment between the Commission and the platforms revolves around widely accepted ideas on mis/disinformation as harmful to society and which therefore must be removed or neutralised. The emphasis is then placed on measures to be taken to remove it. Here we see that measures on platforms fall under three types: (i) measures focusing on the circulation of contents; (ii) measures focusing on users and (iii) measures focusing on building relationships with third parties, such as fact checkers, journalists and researchers, or in other words, with professionals/experts.

The focus on circulation of contents and on placing certain controls over it in the form of either removals or limitations alludes to the operation of an apparatus of security: an apparatus of rules and procedures that govern circulation. Foucault’s analysis of circulation is instructive here: in his analysis, Foucault (Citation2007) has shown that circulation necessarily involves the development of rules of inclusion, exclusion and management of how goods, information and bodies move across different territories. In particular, Foucault discussed the views of the Physiocrats, whose views on the economy were very influential in France of the late eighteenth century: they argued that the wealth of a nation consists in allowing the free circulation of goods and flows of income from one economic sector to the other. Any regulation therefore should be oriented towards removing obstructions from this free circulation. Foucault uses this analysis to argue that circulation of bodies, goods, money and information became the chief focus and justification for the emergence of a governmental apparatus of security. As we observe above with the platforms, a key issue concerning circulation is how to organise it, how to eliminate negative and dangerous aspects and how to make “a division between good and bad circulation and maximising the good circulation by diminishing the bad” (Foucault Citation2007, 18). Circulation is therefore the terrain of ordering movements and interactions, and security developed around it.

By security, Foucault means a particular kind of governing power that emerges at the intersection of punishment, discipline and knowledge under conditions of liberalism. Because liberalism revolves around freedom of circulation, governing power can no longer rely on punishment and discipline. Rather, it needs to develop the kind of knowledge that will allow the optimisation of good circulation, the minimisation of bad circulation and reflexive knowledge on the extent to which it is successful in accomplishing this. Platforms’ control of circulation follows similar principles of developing an apparatus for recognising and controlling “bad circulation,” i.e. circulation of mis/disinformation and then removing it or limiting its reach. The monitoring efforts and the metrics generated in terms of the numbers of posts taken down or demoted are then used to predict future occurrences, instances and types, and gauge the efficiency of the measures taken. The use of metrics and statistics for the purpose of regulating circulation is the knowledge to which Foucault referred to as an integral aspect of an apparatus of security.

The second set of measures, which concern the users, operates as disciplinary procedures in a dual sense: firstly through the penalties involved in putting into circulation mis/disinformation, which operate as negative reinforcement, and secondly through the positive reinforcement of “empowerment tools” as the Code of Practice put it, of clickable labels, information centres, buttons to flag or report contents as misinformation, and algorithmic recommendations. Taken together, they constitute what, following Viejo Otero (Citation2021) we may term discipline of the user: drawing from Foucault’s (Citation1995, Citation2007) analysis of discipline and punishment, the user is conditioned to “correct” their behaviour, through learning and internalising not only what is permitted and what is prohibited but also the norms behind these prohibitions. Unlike the measure on circulation which seek to control the actions of all users, this disciplinary set of measures are deployed on users as individuals. In this manner, there is no recognition of the public as a collective body but of aggregate individual users whose behaviour can and should be conditioned.

The third set of measures on building relationships with fact checkers and other experts operates as a legitimating mechanism, because it helps introduce a fourth source of truth claims, that is distant from platforms, from state/EU political power and from users. Through the introduction of this distance, platforms can convincingly argue that their decisions are independent and do not serve any private interests, and that they are therefore credible and legitimate. Platforms therefore claim of acting in the public interest. In aligning their policies with those of expert fact checkers and journalists, and through collaborations with researchers that study misinformation, platforms’ self regulation employs a rational-bureaucratic model of governance (Weber Citation1947). This centring of rationality in self regulation is important since platforms’ rules cannot derive any legitimacy from political processes (for example through elections) but have to be justified: external expertise plays this role.

In addition, platforms employ a set of practices designed to monitor and calculate the efficiency and effectiveness of these measures. The monitoring efforts and metrics generated in terms of the number of posts taken down or demoted, channels or accounts/pages were penalised, restricted or removed, estimates of how many users were exposed to labelling and its potential impact, are used with two goals: firstly, to gauge the efficiency of the measures taken and make any necessary adjustments, and secondly to generate transparency and self assessment reports that are used to justify their misinformation policies both to the European Commission and to users. These metrics and transparency reports are crucial in showing the success of self regulation (or co-regulation according to European Commission) and sustaining this regulatory model.

The above discussion therefore identifies the platforms’ apparatus of security with respect to misinformation as including: (i) the strategies or Remove, Reduce, Inform (Facebook) and the four Rs of Responsibility (YouTube); (ii) the techno-material apparatus developed to enforce these strategies, which includes the user reports, the content removal processes, the calibration of algorithms that demote some and uplift other contents, the labelling systems and the creation of information resources; (iii) the disciplinary mechanisms of strike systems, restricting and removing accounts, but also of allowing users to correct their behaviours through accessing authoritative information and (iv) the development of relationships with external experts, monitoring reports, self assessment reports and transparency reports, to justify, legitimate and adjust the policies pursued.

This apparatus of security manages the flows of mis/disinformation on Facebook and YouTube as well as users’ behaviours around these contents. In doing so, these platforms essentially construct pandemic misinformation as a problem that occurs at the level of circulation: misinformation must be controlled and secured when it circulates. Efforts are then invested on developing and perfecting the tools by which misinformation is detected and removed, and on the means by which users can be better trained, conditioned or inoculated against believing and sharing this type of information. Returning to the issue of virality and shareability discussed earlier, good from bad virality is differentiated and controlled through the apparatus of security developed by platforms. The tension between relying on and encouraging shareable contents and controlling them has been resolved through focusing on the process of circulation and developing a set of rules and policies around this, along with a techno-material set of measures to enforce these rules and policies and reflexive measures with the aim of producing knowledge and feedback for the overall apparatus and leading to adjustments.

The construction of the problem of misinformation as one of freedom and control of its circulation, and therefore of security, replicates the logic of the infodemic metaphor and its construction of misinformation as a pathogen to be controlled and/or its harm reduced; this requires the formation of disciplinary technologies to control individual instances and security apparatuses to control it at the level of effects on the population. In fact, as Foucault (Citation1995) argued, security first developed around the management of infectious diseases: while controlling leprosy involved the relatively straightforward process of exclusion from the social body, the management of the plague required more sophisticated techniques to discipline the social body and the space it occupied. These techniques sought to keep track, measure and control individuals and their movements, “to set up useful communications, to interrupt others, to be able at each moment to supervise the conduct of each individual” (Foucault Citation1995, 143). Another epidemic, that of smallpox, introduced, according to Foucault (Citation2007) a more sophisticated technique: that of producing knowledge and measurements of the disease and its effects on the population as a whole. This led to the development of an apparatus of security that included and combined the previous models of punishment and discipline and added the element of knowledge constructed through statistical models.

But does this apparatus of security deal with the problem of misinformation? There are two reasons that suggest that this is not the case. The first is that the apparatus of security developed by the platforms appears to be self serving; and the second is that the focus on circulation obscures the process of production of misinformation and the role of the public as a social body whose agency and actions need to be properly understood rather than merely controlled. As Gillespie (Citation2018) has argued, platforms’ policies around content moderation are part of their brand: they are curating the space they offer to users in specific ways. Following this line of thought, the apparatus of security that regulates the circulation of contents on platforms is in the first instance serving their interests and aims to sustain or grow the platform, keeping users engaged and not put off by extreme, offensive, or otherwise problematic contents. The goal of this apparatus is not to eradicate misinformation, or hate speech (Viejo Otero Citation2021; Siapera and Viejo-Otero Citation2021) but to manage it in ways that do not alienate users and advertisers. Ultimately, platforms moderate in order to sustain themselves and not in order to deal with social problems.

Secondly, by placing the focus on circulation, there is little consideration for the moment of production of mis/disinformation. Yet, as Aradau and Blanke (Citation2010) have argued, circulation is fuelled by production. Management of circulation and flows of mis/disinformation ignore the dynamics of production. What are the conditions of production of mis/disinformation? What systems, practices, labour processes are making possible and realising the production of misinformation? The work of Ong and Cabañes (Citation2019) has opened up an avenue of inquiry into the culture of production of disinformation, looking into the social conditions that allow and even push creative industry workers into this kind of work. This, they argue, enables a more holistic social critique and more targeted local level interventions. Similarly, looking at misinformation requires a more comprehensive inquiry and consideration of the conditions of possibility under which misinformation gets produced. This necessitates a sociologically informed analysis of publics, or social groups that produce and engage with information under specific socio-political, economic and cultural conditions. Through focusing on circulation, the problem of mis/disinformation becomes a problem of the platforms, or limited to the platforms, and which has to be addressed by the platforms, and not a social problem that society has to address.

Ultimately, understanding misinformation as the pathogen rather than an indication of a deeply rooted pathology of which it is only one manifestation, assumes that by limiting its circulation the social body will be healthy once more. But overlooking the contexts of its production, the social functions and needs it caters to, and attributing it to “bad actors” or uncritical individuals, obscures the social basis of mis/disinformation and its circulation, which indicates a profound disequilibrium not between the individual and society as Sontag (Citation1978) identified in her discussion of cancer, but in the ways the effects of the pandemic are distributed, experienced, and acquire meaning among different publics, social groups and communities.

Conclusion

The article began with a discussion of the metaphor of the infodemic as linked to an understanding of the phenomenon in a way analogous to a virus, and argued that this is revealing of dominant social values and ideas. We proceeded with a discussion of virality in digital platforms which has gone through two phases: an early positive phase where virality was seen as the principle means of connection, communication and bottom up agency; and the post-2016 phase following Brexit, Trump and Cambridge Analytica, where virality and shareability were seen as toxic and potentially harmful. This created a tension or dilemma that platforms sought to address through developing content moderation policies and practices. How do platforms resolve this tension when it comes to mis/disinformation on Covid-19? To address this question, the article analysed the policies and practices of the two largest platforms, Facebook and YouTube, and the voluntary Code of Practice on Disinformation co-developed by the platforms and the European Commission.

The key finding of this analysis are that platforms’ policies and practices constitute what Foucault called an apparatus of security: a form of governance which focuses on circulation with the objective to regulate the flows of contents in ways that sustain the platforms. This apparatus includes a set of strategies; a set of techno-material tools for the enforcement of the strategies; a set of practices for disciplining users; and a set of practices for monitoring, legitimating and adjusting the apparatus and acquiring more knowledge about mis/disinformation and the effectiveness of their various policies. We argued that the development of this security apparatus is unlikely to deal with the problem of misinformation because it overlooks the question of production.

The apparatus of security as the form of governance of misinformation on platforms is the result of focusing on the process of circulation which alludes to the virality/shareability of contents. In prioritising this attribute and circulation over production, this form of governance intervenes only in one moment, removing/demoting contents and disciplining individual users thereby locating the problem at the level of certain identifiable contents and certain users who are dealt with in an appropriate manner. This limited and ultimately moralistic approach to good and bad information and behaviour constructs misinformation as a problem that begins and ends with these users and these contents. The pathology is limited to these and by restricting them, society can be protected. This however precludes a more in depth understanding of the issue of misinformation as involving a more widely spread pathology which then manifests itself in these individuals and these contents. Paying attention to production may help identify this wider and more deeply embedded pathology that then reaches individuals as a form of dislocation: it is society that has the problem which then manifests itself in certain individuals or communities. Removing, restricting or responsibilising individuals cannot under these conditions heal society or produce a healthy social body. The EU and platform approach to this kind of regulation, beholden to liberalism and individualism, may be able to rise up to the challenge posed by a society whose many ills are evident in the type of information that circulates on platforms and beyond. For this, we need an altogether different approach and to imagine different metaphors. While these will hopefully emerge through social labour, the present analysis sought to elucidate the way in which the problem is obscured and the suffering social body, or public, reduced to individual actions cut off from their social context.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eugenia Siapera

Eugenia Siapera (corresponding author) is Professor of Information and Communication Studies and head of the ICS School at University College Dublin. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 User statistics found in Statista: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

3 The full list of false claims is here: https://www.facebook.com/help/230764881494641/ . The list is dynamic and gets updated when new information becomes available.

4 Found here: https://www.facebook.com/coronavirus_info/

7 Full information is found here: https://blog.youtube/inside-youtube/the-four-rs-of-responsibility-remove/

8 The strike system is described here: https://transparency.fb.com/enforcement/taking-action/counting-strikes/

9 YouTube’s strike system is described here: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2802032

10 The Code is available here: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/code-practice-disinformation

11 The reports are found here: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/reports-may-actions-fighting-covid-19-disinformation-monitoring-programme

REFERENCES

- Aradau, Claudia, and Tobias Blanke. 2010. “Governing Circulation: A Critique of the Biopolitics of Security.” In Security and Global Governmentality, edited by Miguel de Larrinaga and Marc G. Doucet, 56–70. London: Routledge.

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. 2013. The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boyd, Danah. 2010. “Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics, and Implications.” In Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites, edited by Zizi Papacharissi, 39–58. London: Routledge.

- Cadwalladr, Carol, and E. Emma Graham-Harrison. 2018. “Revealed: 50 Million Facebook Profiles Harvested for Cambridge Analytica in Major Data Breach.” The Guardian 17: 22.

- Clegg, Nick. 2020, March 25. “Combating COVID-19 Misinformation Across Our Apps.” Facebook Newsroom. https://about.fb.com/news/2020/03/combating-covid-19-misinformation/.

- Culloty, Eileen, and Jane Suiter. 2021. Disinformation and Manipulation in Digital Media: Information Pathologies. London: Routledge.

- Çarkoğlu, Ali, and S. Simge Andı. 2021. “Support for Censorship of Online and Offline Media: The Partisan Divide in Turkey.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 26 (3): 568–586.

- Dawkins, Richard. (1976) 2014. “The Selfish Gene.” In Essays and Reviews, edited by Bernard Williams, 140–142. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Dommett, Katherine. 2019. “Data-Driven Political Campaigns in Practice: Understanding and Regulating Diverse Data-Driven Campaigns.” Internet Policy Review 8 (4): 1–18.

- European Commission. 2018. Code of Conduct on Disinformation. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/code-practice-disinformation.

- European Commission. 2019. AudioVisual Media Services Directive. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/1808/oj.

- Facebook. 2020, November 19. “Here’s How We’re Using AI to Help Detect Misinformation.” Facebook AI. https://ai.facebook.com/blog/heres-how-were-using-ai-to-help-detect-misinformation/.

- Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and Punish. London: Vintage.

- Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-78. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Gerbaudo, P. 2012. Tweets and the Streets: Social media and Contemporary Activism. London: Pluto Press.

- Gerlitz, Carolin, and Anne Helmond. 2013. “The Like Economy: Social Buttons and the Data-Intensive Web.” New Media & Society 15 (8): 1348–1365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812472322.

- Gillespie, Tarleton. 2018. Custodians of the Internet. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- James W. Cortada, and William Aspray. 2019. Fake News Nation: The Long History of Lies and Misinterpretations in America. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Jenkins, Henry, Steven Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media. New York: New York University Press.

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Ullrich KH Ecker, Colleen M. Seifert, Norbert Schwarz, and John Cook. 2012. “Misinformation and its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 13 (3): 106–131.

- Lewandowsky, Stephen, and S. Sander Van Der Linden. 2021. “Countering Misinformation and Fake News Through Inoculation and Prebunking.” European Review of Social Psychology 32 (2): 348–384.

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Laura Smillie, David Garcia, Ralph Hertwig, Jim Weatherall, Stefanie Egidy, Ronald E. Robertson, et al. 2020. “Technology and Democracy: Understanding the Influence of Online Technologies on Political Behaviour and Decision-Making.” Publications Office of the European Union. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/49b629ee-1805-11eb-b57e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

- McGuire, William J. 1970. “Vaccine for Brainwash.” Psychology Today 3 (9): 36–64.

- Ong, Jonathan Corpus, and Jace Cabañes. 2019. “When Disinformation Studies Meets Production Studies: Social identities and Moral Justifications in the Political Trolling Industry.” International Journal of Communication 13: 5771–5790.

- Papacharissi, Zizi. 2015. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rushkoff, Daniel. 1996. Media Virus!: Hidden Agendas in Popular Culture. New York: Random House Digital.

- Schia, Niels Nagelhus, and Lars Gjesvik. 2020. “Hacking Democracy: Managing Influence Campaigns and Disinformation in the Digital Age.” Journal of Cyber Policy 5 (3): 413–428.

- Shifman, Limor. 2014. Memes in Digital Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

- Siapera, Eugenia, and May Alaa Abdel Mohty. 2020. “Disaffection Anger and Sarcasm: Exploring the Postrevolutionary Digital Public Sphere in Egypt.” International Journal of Communication 14: 491–513.

- Siapera, Eugenia, N. Niamh Kirk, and Kevin Doyle. 2019. Netflix and Binge? Exploring New Cultures of Media Consumption. Dublin: Broadcasting Authority of Ireland.

- Siapera, Eugenia, and Paloma Viejo-Otero. 2021. “Governing Hate: Facebook and Digital Racism.” Television & New Media 22 (2): 112–130.

- Silverstone, Roger. 2017. Media, Technology and Everyday Life in Europe: From Information to Communication. London: Routledge.

- Sontag, Susan. 1978. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- UN. 2020. “Tackling the Infodemic.” https://www.un.org/en/un-coronavirus-communications-team/un-tackling-%E2%80%98infodemic%E2%80%99-misinformation-and-cybercrime-covid-19.

- van Dijck, Jose. 2013. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- van Dijck, Jose, and Thomas Poell. 2013. “Understanding Social Media Logic.” Media and Communication 1 (1): 2–14.

- Viejo Otero, Paloma. 2021. Governing Hate: Facebook and Hate Speech, Unpublished PhD thesis, Dublin City University.

- Wardle, Claire. 2018. Information Disorder: The Essential Glossary. Harvard, MA: Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School.

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. “Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making.” Council of Europe 27: 1–109.

- Watts, Duncan J., Jonah Peretti, and Michael Frumin. 2007. Viral Marketing for the Real World. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Pub.

- Weber, Max. 1947. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- WHO. 2020. “First Infodemiology Conference.” https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2020/06/30/default-calendar/1st-who-infodemiology-conference.