Abstract

Media policy analysts of (neo)liberal persuasion have long seen China as an anomaly. This is, however, a narrow perspective, whose explanatory power pales facing the challenge of recent events. Drawing upon International Relations (IR) theories, this article reflects on the contradicting ideas of (neo)liberalism and (neo)realism in digital media policy, while examining US–China tech war and China’s state-directed platform capitalism. It argues that more attention should be paid to neorealist frameworks, especially Mearsheimer’s offensive realism, which sees the world as consisting of billiard balls bumping into each other, pursuing hegemony. How is offensive realism useful in helping understand recent events about China? How is it also limited? Are we returning to an era of billiard balls? What are the implications for digital media policy to transcend platform capitalism and approach platform socialism?

Introduction

When the People’s Republic of China (PRC) joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, few could have foreseen that two decades later China would become arguably the worst foe of the neoliberal global media order. There are of course other authoritarian regimes such as Russia and Iran. Democracies are meanwhile increasingly flawed from the inside, e.g. by right-wing populism in Brazil and India. China, however, is a different kind of challenge due to the size of its digital industries, its tech prowess in artificial intelligence (AI), the centralised nomenklatura of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and its unique institutional legacies from the Maoist period of 1949–1978 to Xi Jinping’s New Era since 2013 (Zhao and Wu Citation2020; Qiu Citation2022).

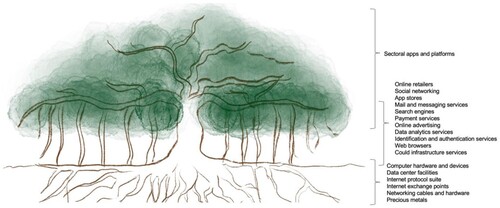

Understanding China requires a paradigmatic shift away from models of (neo)liberal thinking. “Models of communication are,” wrote James Carey, “not merely representations of communication but representations for communication: templates that guide, unavailing or not, concrete processes of human interaction” (1989, 32, original emphasis). The goal of this article is to discuss the challenges posed by the case of China to digital media policy, through two recent developments: the US–China tech war and Beijing’s measures in directing Chinese digital industries. Following van Dijck (Citation2021), it construes digital industries in China as a holistic ecosystem of platforms, apps, hardware, and infrastructures, all interacting with each other to form “platform trees” in a “forest.” But unlike the American “giant sequoia” (van Dijck Citation2021, 2806) or the European “platform tree” (van Dijck Citation2021, 2815), the mental image for China is probably less a “bamboo” (van Dijck Citation2021, 2815) than a banyan tree with its extended root systems both underground—that is, the world’s largest industrial system for digital hardware manufacture—and above ground, i.e. the aerial roots representing the abundance of data and data-driven businesses, resulting arguably from the world’s most invasive national surveillance systems. A gigantic banyan tree can grow to cover acres of land with its aerial roots reaching to the ground becoming prop roots that support the expanded tree crown. As such, the Chinese digital industries banyan tree forms a forest in itself, whereas in southern China the banyan tree symbolises close-knit community and interconnected communal life, if not oppressive communitarianism ().

Building on insights from International Relations (IR), this article argues that, in Chinese contexts, (neo)liberal conceptions of digital media policy have become obsolete. What, then, are the alternatives? How do the alternatives, particularly the offensive realism model (Mearsheimer Citation2014), have their own limits? How can the limitations be transcended for the envisioning and realisation of public interest through a non-capitalist, even socialist, path? The challenge of China is often simplified into binaries: China versus the US, communism versus capitalism, censorship versus freedom. Especially important for internet policy is the contradiction between multistakeholderism and multilateralism (Raymond and DeNardis Citation2015), the former represented by US-dominated ICANN (International Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers), the latter by the supposedly China-dominated ITU (International Telecommunications Union). Such dichotomous understandings are essentialist and imprecise. This article offers a critique to dislodge the binaries while reflecting on China’s digital media policy, its past trajectories and future prospects.

Liberalism, Realism, and Constructivism

In studies of global media and communication, liberalism is often the unstated presumption. The rise of the internet and digital communication in the 1990s coincided with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the peaking of American power. The 1996 Telecommunications Act of the United States accelerated the neoliberal turn that began in the 1980s but now through more drastic measures of privatisation, deregulation, and globalisation around the turn of century (Freedman Citation2008). Since then, although US dominance has faced contention from Europe and the BRICS countries, especially China and Russia (Nordenstreng and Thussu Citation2015), the global order for digital media from news to entertainment has remained neoliberal. This pattern is most pronounced for AI-powered digital platforms: Alibaba, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), Tencent (WeChat), Uber—all listed companies responding to investor’s profit maximisation demand or that of venture capitalists as in the case of privately-held unicorns such as ByteDance (owner of TikTok and Douyin). While competing, these platform companies work together in weaving a global web of commerce for hardware, software, content, and/or distribution channels; a web of financial flows, corporate ownership, collaboration, and managerial personnel networks; a web of private companies now becoming “cloud empires” (Lehdonvirta Citation2022) whose tremendous wealth, intellectual property, and political clout dwarf nation-states. This is, through the perspective of IR, quite akin to a typical scenario that (neo)liberalism reifies and contends for.

A common analogy among IR scholars is to compare (neo)liberalism with a “cobweb” (Burton Citation1972), whose functioning—in trapping an insect, for instance—depends on the strength of the entire interconnected system rather than particular nodes. The cobweb in IR is based on international division of labour, cooperation, and market exchange among companies, individuals, and interest groups of all kinds including but not limited to governments. Transactions through the cobweb lead to the emergence of complex interdependence relationships (Keohane and Nye Citation1977), which gives rise to durable patterns of commerce and trust as in trade networks and supranational organisations such as ICANN (Koppell Citation2005).

Theoretically, multistakeholderism is based on the liberal notion of a cobweb, in which state and non-state actors, corporations and civil society organisations, collaborate on issues of digital media policy (Raymond and DeNardis Citation2015). But as Freedman (Citation2008) discovered in the GATS/WTO audio-visual trade negotiations, the policy shifts of liberalisation and deregulation tend to be driven by corporate actors exerting influence through government officials. Little is influenced by civil society groups despite admirable attempts such as NETmundial (West Citation2018). Multistakeholderism in practice is often a camouflage for corporate takeover through “transnationalism” by which leading liberalist James Rosenau understands as “the processes whereby international relations conducted by governments have been supplemented by relations among private individuals, groups, and societies that can and do have important consequences for the course of events” (Citation1980, 1). In digital media policy, such transnationalism in the twenty-first century has led to two pivotal shifts, one being “a shift away from formal government regulation toward informal and often highly corporatised governance mechanisms,” the other “a shift away from state-based governance towards transnational governance institutions, such as the ICANN, which are more directly responsive to the asserted needs of private entities, often corporations that are those institutions’ most powerful ‘stakeholders’” (Couldry et al. Citation2017, 178).

In the age of AI-powered platforms, the problem of corporate control using multistakeholderism as one of its vehicles has become more acute through secretive algorithms and informal boardroom decision-making, designed to meet the private interests of the company, its investors and associated vest interests, even at the expense of public interests. As such, the root problem of the cobweb is (neo)liberal capitalism, dominated by Davos Men (Flew Citation2020) and the likes of Google and Alibaba, regardless of the country of origin—be they American or Chinese.

While the (neo)liberal common sense has dominated digital media policy from the 1990s, (neo)realism as an opposite school of thinking has even longer tradition in IR theory. It sees sovereign states as the main actors of world affairs, who are self-contained and autonomous, pursuing national interests in alliance and/or competition with other governments. The forms of interaction can be political, diplomatic, economic, cultural, but the most decisive is military. Arnold Wolfers first compared such a conception to a “billiard ball world” (Citation1951, 40):

All the units of the (multistate) system behave essentially in the same manner; their goal is to enhance if not to maximize their power. This means that each of them must be acting with a single mind and single will; in this respect they resemble the Princes of the Renaissance about whom Machiavelli wrote. Like them, too, they are completely separate from each other, with no affinities or bonds of community interfering with their egotistical pursuit of power. They are competitors for power, engaged in a continuous and inescapable struggle for survival. This makes them all potential if not actual enemies; there can be no amity between them, unless it be an alignment against a common foe.

Two main branches of neorealist thought have developed in recent decades: defensive and offensive realism, the latter being particularly relevant for the analysis of recent events involving China. The former—defensive realism a la Kenneth Waltz—assumes that the primary goal of nation-states is to survive in a global system characterised by anarchy. Hence, states tend to fear each other. They are therefore often “defensive,” i.e. conservative and attempting to avoid the high risks of war. They strive for “balance of power,” e.g. through military blocs or security pacts, while preserving status quo (Waltz Citation1979).

Offensive realism shares some structural presumptions with defensive realism but it maintains that

the ultimate goal of every great power is to maximise its share of world power and eventually dominate the system. In practical terms, this means that the most powerful states seek to establish hegemony in their region of the world while also ensuring that no rival great power dominates another area. (Mearsheimer Citation2014, 447)

Compared to (neo)liberalism and defensive realism, Mearsheimer’s offensive realism fits better with recent events of US–China tech war since 2018 when both countries have engaged in belligerent behaviours—albeit to different degree—without trying to preserve the bilateral and multilateral status quo, as will be explained in the next section. Beijing’s policy towards Chinese tech giants, as shall be discussed later in this article, can also be seen as efforts to discipline the private sector in order to form a unified and insulated “billiard ball” in anticipation of US offense as well as possible offensive moves by China itself. The comparative advantage of offensive realism being conceptually apparent, there are however several gaps when applying the billiard ball model to digital media policy.

First, critics of realism in the post-Cold War context contended that both branches of neorealism can hardly explain international politics under American unipolar hegemony (Pashakhanlou Citation2014). This critique can be countered by the argument that the contemporary world has entered a “new Cold War” when US hegemony is no longer unequivocal; that certain nation-states, China and Russia for instance, have exited from the US-corporate-led cobweb to enter the system of billiard balls. Another critique is that, like Huntington’s “clash of civilizations,” Mearsheimer’s offensive realism may become a “self-fulfilling prophecy” (Bottici and Challand Citation2006), producing a vicious cycle of interstate suspicion and armed conflicts, one feeding into the other. Although Mearsheimer stresses that offensive realism is value-neutral, he cannot prevent it from being interpreted and used as a teleological justification for war mongering.

Researchers of media policy may wonder how the neorealist emphasis on military capacity and geopolitical strategy can be translated into the policies and policy discourses of digital media (Hong and Chen Citation2022). Are digital media systems becoming “billiard balls” themselves, clashing with each other? Or, are they subsumed into the statist systems, e.g. through the deployment of misinformation or cyberwar offence against other states? Perhaps both may happen? Also possible is that neoliberalism and neorealism can co-exist: the cobweb of economic transactions and personnel networks serving as the “pool table,” on which the billiard balls of China, US, and other national digital media systems collide. This scenario used to be more plausible before Russia was cut off from the SWIFT financial transactions system following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. But its likelihood has declined since. In the event of an all-out military conflict between China and the US, the billiard ball model will probably prevail, tearing apart the cobweb of market transactions.

Be it the cobweb or the billiard balls, a key issue has to do with the unit of analysis given the long traditions of examining community media (Rennie Citation2006) and social movement media (Downing Citation2000) in media policy studies. These communities and social movements are often subnational systems, whose goals and logics are distinct from those of the state, especially the military-industrial-media apparatuses carrying out the core “billiard ball” functions. Stressing the communal level means that the choice of digital media policy does not have to be constrained within the false dichotomy of liberalism vs. realism, or multistakeholderism vs. multilateralism. The real challenge of digital media policy is about how to transcend the binary while retaining the authenticity of grassroots participation and shared imagination among grassroots communities. In other words, what are the substances that constitute the billiard balls? Answer to this question is probably more crucial than the size, weight, and speed of the billiards themselves.

Communities can be online and/or offline; transnational, local, and/or translocal. Defined not just by state sovereignty (e.g. passports) or market transactions (e.g. through Alibaba or Amazon), communities of media practice and policy emerge more fundamentally through shared identities, meanings, and values. This is the essence of constructivism, which according to Wendt (Citation1992) is a more basic approach that underlies liberalism and realism, whereas it allows for agency despite the structures—commercial or military—and social and political change therein. Central to constructivism are intersubjective knowledge and discourse, which prepares the ground for interstate alliances and transnational markets. Meanwhile, the intersubjective sharing of animosity, prejudice, and “digital cold war” (Hong and Chen Citation2022) can lead to a culture of fear among the local/national/transnational communities.

Such sharing processes are also integral to social movement mobilisation and alternative media operations. Most important, community-level constructivist analysis can shed light on the (lack of) democratic decision-making in media policy processes dominated by either corporate giants or state bureaucracies. In other words, it offers a broader horizon for the pursuit of public interest and democratic control over the cobweb as well as the billiard balls, both being elitist and fundamentally capitalist: the cobweb stands for neoliberal business as usual; the billiard balls model the belligerent form of intercapitalist imperial competition. This broader horizon includes but is not limited to possibilities that are socialist, feminist, de-colonial, ecological, and communist—based on the sovereignty of the people (Dean Citation2012). It can be founded on the “data sovereignty” (Daly, Mann, and Kate Devitt Citation2019) of diverse Indigenous communities for instance, mustering power from the bottom up, through the prop (aerial) roots of the digital-media banyan tree, rather than national and transnational capitalist elites imposing control from the top down through algorithms and media policy.

The US–China Tech War

The US–China tech war broke out in June 2018, a few months after Trump initiated the trade war in January 2018. The two “wars” are related but with distinct objectives. Both utilise “national security” as justification. Whereas the stated goal for the trade war is to reduce US trade deficits by selling more products (e.g. agricultural) to China, the tech war aims at preventing China from surpassing the US in its high-tech capacities, especially those for military use, regardless of the implications to US exports. Washington explicitly targeted the “Made in China 2025 (MIC2025)” program which, according to Beijing’s plan, would upgrade Chinese industries in strategic sectors such as AI and semiconductor to global leadership. Exports of key components and machineries to China have been restricted with the ironic effect of increasing US trade deficits. Since January 2021, the Biden administration has implemented tactical adjustments to Trump-era policies while maintaining the overall offensive strategy towards China. As a result, while the trade war has reached relative stagnancy at the time of writing, the tech war has continued to escalate under the Biden administration, which has been more aggressive on the tech front, acting more precisely and in a more unbending manner, especially on the microchip sector where a new “semiconductor warfare” has emerged (Cheong Citation2022). Bygone is the time of “Chimerica” discourse for US–China integration (Zhao Citation2014) that has collapsed into hostilities (see ).

TABLE 1 A Timeline of US-China trade war and tech war

First thing to note is that the US initiated the downward spiral of bilateral relations, showing that America remains the dominant player exercising hegemony through “de-coupling,” i.e. driving China out of the US-controlled global digital media ecology. Actions against Chinese tech firms such as Huawei dated back to 2003 (Tang Citation2020, 4564), which accelerated during the ZTE export ban of 2017–2018 (Pettypiece and Mayeda Citation2017). In August 2017, the Trump administration launched Section 301 investigation into China’s practices related to forced technology transfer and intellectual property policies, which set a precedent since China joined the WTO (Tian Citation2008). In March 2018, the US filed charges against China’s intellectual property theft through the WTO. After the WTO ruled in favour of China in September 2020, Washington nonetheless continued its “de-coupling” actions. Beijing has, for the most part, played defence in this tech war. It tries to mitigate the consequences on its exports and high-tech build-up through continued but increasingly limited interactions with US players, while being forced to use its “internal and external circulations” as remedies: external meaning China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) involving mostly developing countries as well as geostrategic allies such as Russia.

In line with predictions of offensive realism, Washington adopted a multi-pronged and multi-faceted strategy against China during the tech war in order “to be the hegemon—that is, the only great power in the system” (Mearsheimer Citation2014, 22). Trump first increased tariffs for Chinese high-tech exports to the US in 2018, followed by export controls and the restriction of key components and machinery to China since 2019, which “marks a shift from more defensive measures to more offensive tools” (Barkin Citation2020, 2). More than a unilateral move, the US convinced its allies from West Europe to East Asia to cease exporting “sensitive technologies” in sectors such as AI and microprocessor manufacture. Such an alliance led by Washington was “a new source of transatlantic tension” (Barkin Citation2020, 2) by the end of Trump’s presidency. But since Biden assumed power in January 2021, especially since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the US-led camp has apparently become more coherent as if, based on their trade cobweb as well as security pacts, this alliance has appeared to start behaving like a single super-sized billiard ball.

Besides tariffs and export controls, the Biden administration further strengthened its offensive measures through restricting the flow of American capital to China as well as personnel exchange with China. In June 2021, Biden signed an executive order to address “threat posed by the military-industrial complex” of China, forbidding investments in 59 Chinese companies including Huawei and SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation), the latter being China’s largest microchip manufacturer. Since October 2022, the ban has been extended to include “all American persons,” i.e. US citizens, residents, and companies, who are prohibited to work for semiconductor producers in the PRC (Sheehan Citation2022).

A consistent strategy from Trump to Biden is to target Chinese high-tech companies such as Huawei and ZTE, which the FCC (Federal Communication Commission) designated as “national security threats” in June 2020. Earlier in August 2018, the Trump administration first penalised ZTE with a hefty fine of $1 billion (Davis, Strumpf, and Wei Citation2018). Since then, the bilateral crossfire had concentrated on Huawei and TikTok until Biden adjusted Trump’s tactics in 2021. The arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou in December 2018 marked a turning point. Meng was released after conceding in June 2021 that Huawei violated US sanctions against Iran (Viswanatha et al. Citation2021). In August 2020, Trump ordered Beijing-based tech giant ByteDance to spin off or sell its TikTok business in the US to an American company (Gray, Citation2021). In the following month, a US court blocked Trump’s executive order. In June 2021, Biden revoked Trump’s order on TikTok (Rogers and Kang Citation2021).

However, this does not mean Biden softened US aggression towards China tech. He has fine-tuned Trump’s hit list by removing certain Chinese companies, e.g. Xiaomi (smartphone and IoT maker) while adding others, e.g. DJI (drone maker). Most importantly, by signing the CHIPS and Science Act in August 2022, the Biden administration has focused more on the semiconductor sector to ensure that American “advanced tech” companies will increase their global supremacy through the allocation of $280 billion federal funds while suppressing their Chinese counterparts by barring technology transfers. CHIPS stands for “Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors” (Luo Citation2022).

China did retaliate during the trade war, albeit with limited effect due to its lopsided export surplus that made itself more vulnerable to US tariff hikes. Retaliation is even less feasible for the tech war in that, while many Chinese tech firms have long-standing reliance on the US in terms of intellectual property, capital, personnel, and components, the reverse is not true for Silicon Valley. Subsequently, when the US took aim at Chinese tech industries, Beijing faced more constraints in policy options for the tech war compared to the trade war because the US is even more hegemonic in this high-tech theatre of intercapitalist struggle. Hence, it is unsurprising that the tech war has significantly derailed MIC2025.

Is the US following a multistakeholder approach, whereas China a multilateral one during the tech war? Not really. There is little evidence that decision-making in the White House is based on consultation with corporate America, let alone civil society. During the trade war, Trump faced criticism when he argued that it was China, not American companies or consumers, who paid the additional tariffs (Jacobson Citation2019). This was likely among the reasons why Biden adjusted US strategies and refocused away from the trade war based on policy inputs from his administration, not from other stakeholders in the public or private sectors. Declaring that its goal of the tech war is to safeguard American “technology leadership” and weaken China’s “industrial-military complex,” the Biden administration has mobilised its allies from the UK, Europe, and Canada to Australia, Japan, and India. The formation is more akin to US unilateralism commanding the multilateralism of the allies, which in turn influences multiple stakeholders including especially IT companies in each country. Rather than what is expected of multistakeholderism (Raymond and DeNardis Citation2015), this is a single dominant billiard ball (the US) leading numerous billiard balls (US allies) that set policies for the neoliberal cobweb. The core of America’s tech war approach is rather “big government” and interventionist, instead of the neoliberal “small government” and corporate-led model.

So far China’s options seem to be mostly defensive. Facing the aggressive moves by the US, it can try to bypass export controls through smuggling key components and machineries. Chinese tech companies can set up branch offices in Singapore or South Korea to retain American executive and R&D talents who are now prohibited to work in China. Most important, China can nurture collaborations with Germany, Japan, and the Netherlands, where industry leaders may not see eye to eye with their American counterparts and can be used to create more “balance of power” to China’s favour. In February 2022, Beijing reportedly planed on starting its “cross-border semiconductor work committee” (Tabeta Citation2022), which was likely a main target for Biden’s CHIPS and Science Act.

Can China play offence? In theory, the PRC may attempt to use its multilateral approach to counter US aggression by identifying certain pressure points and breaking through them to gain strategic advantage. One possible front is supranational organisations such as ITU, whose Secretary General has been Zhao Houlin since January 2015. Zhao was a former engineer in China’s Post and Telecommunication Design Institute. Between 1999 and 2006, he directed ITU’s Telecommunication Standardisation Bureau. Western media often portray Zhao and his Chinese colleagues as Beijing’s instrument. This is refuted by Negro who discovers that “Chinese agents in the global debate on internet governance support a multi-stakeholder perspective” (Citation2020, 104). Another study by Nanni on the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force) confirms that “the Chinese government does not have full control of its domestic private actors, among which there is both collaboration and conflict” and that “Chinese stakeholders have increasingly accepted the existing functioning of IETF standard-making as they grew influential within it” (Citation2022). The multilateral sovereign-state-based approach takes long time to work in actuality and, at the end, it often has no teeth in countering the US. If Washington could simply ignore the rulings from WTO in September 2020, would it pay heed to supranational organisations such as the ITU?

A second possible beachhead of Chinese offence is to build up alliance and a high-tech “united front,” particularly among those who have estranged the US or are side-lined by the Washington-led bloc. Teaming up with the likes of Russia and Iran upsets the White House. However, it is doubtful if such multilateralism will have sufficient sway on the global tech giants, as compared to policy interventions imposed by the US and its allies. Chinese tech companies also fear the consequences of being associated with Iran (as Huawei learned the hard way). Since February 2022, Chinese firms such as DJI have limited their exports to Russia for fear of US sanctions (Whalen, Citation2022). Openly forming a pact with Moscow or Tehran will add little to balancing out American aggressions, while further jeopardising the global ambitions and even survival of Chinese tech firms. Comparatively speaking, mustering support from other Global South countries may attract less western counterattack (less does not mean negligible). But the effectiveness of such offensives—collaborating with Ethiopia or Venezuela for instance—will be doubtful given their peripheral role in global digital media policy.

China seems to have few choices except being forced to break away from the US-dominated global system. This may end up in a few years making Chinese tech banyan tree more of an autonomous ecosystem standing on its own as was the case during the Maoist period (Qiu and Wang Citation2021). But until then, it may also reduce China into a less formidable tech force, especially if it cannot perform effective balancing acts with regional IT leaders in Europe (e.g. Germany) or East Asia (e.g. Japan). Regardless of the result, so far there is little evidence to characterise China’s approach during the tech war as multilateral, whereas it remains to be seen if American aggressions can really hurt the taproot of Chinese state-directed platform capitalism, as will be discussed in the next section.

Among the few fronts that China may apply offensive realism in the tech war are (a) fostering capacities away from domains of US sanctions, e.g. quantum computing, although Washington is likely to expand the scope of tech bans; and (b) co-opting or invading Taiwan, whose TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacture Co. Ltd.) is the world’s most valuable semiconductor producer, who enjoys 92 per cent of global market share for the manufacture of advanced microchip wafers that measure 10 nanometres or less (Jiang Citation2022). Beijing has attempted to co-opt Taiwanese tech giants but with little success. Alerts have been issued in China as well as the US about impending military conquest of Taiwan. This author cannot predict if and when China’s “re-unification by force” will occur, which will depend on numerous factors beyond media policy. At least from the perspective of semiconductor manufacture capacity it is unlikely that Beijing will take such an offensive move. As Morris Chang, the founder and CEO of TSMC, explained, producing semiconductor entails a truly global network of suppliers and collaborators. Even if the PLA (People’s Liberation Army) occupies Taiwan, the manufacture facilities of TSMC in Taiwan will not suffice to keep global leadership without being in constant interactions with other key players in the US and its ally countries such as Japan and South Korea. Meanwhile, even without military conquest, the PRC may utilise gaps in Taiwan’s regulatory system to bypass US sanctions (Jiang Citation2022), meaning that maintaining the status quo across the Taiwan Strait would benefit China’s tech sector more than the scenario of military conquest.

Contrary to popular discourse, it remains immature to tell if the US’s offensive realism moves will decimate China’s digital banyan tree. The measures taken by the US on technology transfer, exports control, the movement of capital and personnel, and so on, appear formidable. But they are far from watertight. In addition to materialised institutional constraints, the US strategy also combines “blackmail and war” (Mearsheimer Citation2014, 35) supplementing neorealism with constructivism, attempting to achieve coercion through bluffing. Another constructivist-realist strategy is for US intelligence agencies to deliberately overestimate Chinese capacities, to foster “red scare” that serves as both budgetary justifications and illusions of a formidable foe. For Washington, an imagined foe unites the public and the allies. For Beijing, it’ll be essential to avoid the folly of believing in these constructed overestimations because they are part of the disinformation campaign designed for offensive realism goals. In other words, the great banyan can be more easily toppled by the gravity of its own hubris, now magnified through AI-facilitated decision-making (Farrell, Newman, and Wallace Citation2022). Although China’s surveillance systems probably churn out more data than any other authoritarian country, they have not been successful in stemming out large-scale protests, for example, the so-called “white paper revolution” against China’s zero COVID policy in November 2022 or pensioners’ demonstrations concerning medical reforms in Wuhan and Dalian in February 2023 (Chen Citation2023).

Under dual pressure from the Washington and from Beijing, the Chinese digital-media banyan tree is being subject to a forceful trimming with its canopy (i.e. data services such as fintech) and root systems (e.g. semiconductor manufacturing) being cut out. So far it looks more like a pruning than truncation of the great banyan whose future is hanging in balance. Yet, it is key to bear in mind that the great sequoia of US tech and the European platform tree are being affected, too. The whole forest, not just any specific member of the international community, can be endangered, if the states sleepwalk into another full-scale conflict similar to World War I (Clark Citation2012).

China is forced into a corner. It will be a strenuous up-hill battle if it hopes to emerge from the tech war through a conventional, capitalist path that the US knows all too well. The lot of China’s digital banyan tree depends on the extent to which Beijing can amounts a truly unexpected “offence,” rather than emulating the US in pursuing imperialist global media hegemony. In doing so, will China stumble back into a genuinely alternative, socialist road towards digital technologies by the people, for the people, and serving the people, as once envisioned by Dallas Smythe (Zhao Citation2007)?

State-Directed Platform Capitalism

Shortly after the outbreak of US–China tech war, liberal commentators in and outside China were dismayed to witness an unprecedented “crackdown” by Beijing on Chinese tech companies (Yuan Citation2022). In October 2020, officials vetoed the $313-billion IPO of Ant Group, the financial services spin-off of China’s e-commerce giant Alibaba (Zhong Citation2020). Two weeks before China’s leading ride-hailing platform, Didi, went public on NYSE in June 2021, the State Administration for Market Regulation began antitrust investigation against Didi. In the following month, the Cyberspace Authority of China ordered the removal of Didi apps from Chinese app stores, a ban remaining upheld at the time of writing (personal interview). September 2021 saw the People’s Bank of China prohibiting all cryptocurrency transactions in the country. Administrative interventions aside, party-state control over Chinese data-driven industries escalated through the Data Security Law of September 2021 and the Personal Information Protection Law of November 2021, extending the legislative logic of China’s 2017 Cybersecurity Law (Lee Citation2018). The new laws further restrict data collection and processing of personal information while barring cross-border data transfers probably for fear of “data trafficking” from China especially through payment apps (Kokas Citation2023). These bureaucratic and legal-institutional measures supposedly would devastate China’s digital media “banyan tree,” affecting its root systems, data-processing branches, drive for innovation, and commercial viability (Yuan Citation2022). Why did China harm itself as if the tech war was not destructive enough?

Offensive realism predicts that nation-states must unify their resources within the sovereign surface of the billiard balls before bumping into each other. What is seen as Beijing’s counter-intuitive moves from a neoliberal perspective may turn out to be a necessary step to prepare for offensive-realist clashes. Otherwise, centrifugal forces within the country may corrode state endeavours or cause implosion. To make full sense of China’s recent strategies in the domestic realm of digital media policy, we need a more holistic understanding about China's development trajectory long before the tech war.

In China studies, “shou-fang cycle” is an essential notion about the alteration between increasing control or shou (literal meaning: “pulling back”) and reducing control or fang (literal meaning: “letting go”). According to Baum (Citation1996, 5), CCP chief propagandist Deng Liqun observed in the 1980s that in odd-number years (e.g. 1981, 1983, 1987, 1989) the pendulum moved toward shou with more political centralisation and ideological restrictions; whereas in even-number years (e.g. 1982, 1984, 1986, 1988) the opposite tendencies of fang led to more liberalisation and privatisation away from party-state control. Although perhaps an anecdotal observation, the shou-fang cycle demonstrates the internal contradictions within the CCP, which struggles to balance between two policy goals: (a) joining the capitalist world system while fostering domestic private-sector businesses including in media, communication, and technology; and (b) continuing Chinese-style socialism with the party-state maintaining autonomy from the “cobweb” that consists of external and internal forces of neoliberalisation. The cyclical pattern was pronounced during the final decades of the twentieth century. Does it still apply since the 2010s?

American AI-powered media giants are referred to as GAFA: Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Amazon. Their equivalents in China are BATJ: ByteDance, Alibaba, Tencent, and JD.com. Of the Chinese Big Four, Alibaba and JD specialise in e-commerce; Tencent leads in social media and gaming; ByteDance is the world’s largest unicorn company that owns TikTok and Douyin (short-video entertainment platforms) as well as Toutiao (news platform). For the most part of the 2010s, BATJ had gone through a prolonged period of fang when Chinese authorities chose to stay on the side lines until 2020 when the pendulum swung towards shou. This was a golden decade for China’s platform capitalism which, like its American counterparts, enjoyed the windfall of quantitative easing and declining investment returns in traditional economic sectors that made AI and tech the favoured destination of hot money. The Chinese experience was, however, also unique in the incredibly malicious tactics of cutting-throat intercapitalist competition as shown most notoriously in the high-profile “3Q warfare (3Q dazhan)” that earned China the title of “Wild Wild East” for platform capitalism.

“3Q” stands for two competitors in China’s software market: “3” being the “360 Safeguard” program developed by the internet security company Qihoo; “Q” stands for “QQ,” Tencent’s popular social media program. In 2007, Tencent released its own antivirus software QQ Doctor, which since early 2010 started to identify and target 360 Safeguard as a computer virus. This prompted Qihoo’s counter-attack in September 2010 through which 360 programs prevented QQ from “stealing user data.” Two months later, Tencent made QQ incompatible with computers that had 360 software installed in them, forcing millions to choose between QQ and 360. Both sides used disinformation and abused their market positions against each other, holding ordinary internet users hostage. Both formed alliance with other software companies that led to two camps of software companies, whose products became incompatible with those of the other camp. The Ministry of Industry and Informationalisation (MII) and the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) intervened so that both sides discontinued their acts of belligerence imposed through technical incompatibilities. Yet, the legal battle mounted by Qihoo proceeded until October 2014, when China’s Supreme Court ruled in favour of Tencent.

Qihoo 360 vs. Tencent QQ is a landmark case for internet antitrust in China (Jiang Citation2014). It signals a decisively neoliberal turn for platform capitalism with Chinese characteristics: dominant tech giants could abuse their market hegemony with impunity; the authorities would only intervene at a minimal level to protect public interest, and ultimately they would end up supporting the company with the largest monopoly and the strongest network effects. Such was the brutal logic of the strong eat the weak, as the neoliberal law of the jungle received official endorsement.

Besides “3Q warfare,” Chinese platform companies during the 2010s were also guided by some of the world’s most obnoxious venture capitalists, especially Masayoshi Son, the founder and CEO of SoftBank Group in Japan who was an early investor in Alibaba. Son and his disciples—several of whom count among the richest men of China (all men indeed!)—had championed the strategies of “blitzscaling” in Asian contexts (Lin, Chen, and Xie Citation2020). Son’s ambition through his Softbank Vision Funds, the world’s largest tech investment funds that worth more than $154 billion in March 2021, is to build a global cobweb among its portfolio companies, of which Alibaba is by far the largest (Lin et al. Citation2020). Such a dreamland of neoliberal platform capitalism has, however, started to fall apart since 2020 especially in China, where a decade of prolonged fang finally came to an end, yielding to a new era of shou.

Under policies of increasing control since 2020, Chinese neoliberal platform capitalism is being transformed into state-led platform capitalism, a form of embedded capitalism that is contained within the billiard ball of the PRC, where non-capitalist and socialist formations are also taking place. A case in point is China’s social credit system (SCS) that is often portrayed as “an Orwellian nightmare” of state surveillance (Creemers Citation2018, 2). Yet, based on webscrapping data from four SCS pilot cities (Hangzhou, Fuzhou, Zhuhai, and Hefei), Jee (Citation2022) discovered that the surveillance-based blacklists mostly target misbehaving firms, not citizens, and the main goal is to prevent the firms from repeating past offenses such as tax evasion, non-compliance with court orders, labour law infractions, and public safety and environmental violations. These are state-led initiatives in that the blacklist entries come from local government offices such as low-level courts and regulatory agencies. But they are not “state-owned” because they do not rely so much on top-down bureaucratic control. “State-led” means that the leadership of party-state agencies co-exist with, sometimes having to rely on, non-state actors—not only tech companies, their management and algorithms but also their employees, communities of users, and grassroots stakeholders. The latter include micro influencers and crypto enthusiasts despite the People’s Bank of China banning all cryptocurrency transactions in the country (Shin Citation2022). In other words, while surveillance-based oppression and data abuses remain a legitimate, albeit exaggerated, concern, the movement towards offensive realism in the world’s largest “actually existing socialism” country does not necessarily lead to a single panoptic future as popular media coverage too often tries to portray. It is key to recognise that this movement also creates possibilities for genuine transformation of digital industries beyond the neoliberal as well as the neorealist, and the current stage of state-led platform capitalism may become a transition period when community-level and meso-organisational constructivism can exert considerable influence on macro structures. That is, at least, a working hypothesis worth contemplating.

Media commentators tend to pay exclusive attention to Beijing’s national security concerns in controlling, for instance, China’s semiconductor industry now being targeted by US tech war offences. They often lament that Xi Jinping has departed from Deng Xiaoping’s low-key diplomatic policy of taoguang yanghui, a form of defensive realism designed to promote China’s “peaceful rising” without attracting unwanted attention or building what Waltz calls “excessive strength” in order to maintain status quo balance of power. Yet, as Mearsheimer wrote, “Like liberalism in the United States, Confucianism makes it easy for Chinese leaders to speak like idealists and act like realists” (Citation2014, 497). What, then, are the kinds of “Confucian” policy discourse now being constructed in the PRC?

Most noteworthy in the latest shou period are two narratives: one is the overall discourse about “common prosperity (gongtong fuyu)”; the other deals with digital technology more specifically, i.e. “virtual economy serving substantive economy (xuni jingji fuwu shiti jingji).” “Common prosperity” has long been a goal of Chinese socialism, whose priority in policy discourse has surged since 2019 due to the CCP’s poverty elimination campaign and its efforts to reduce income gap by redistributing wealth from the super-rich. Big Tech stood out because the likes of Jack Ma (co-founder of Alibaba), Pony Ma (co-founder of Tencent), Zhang Yiming (founder of ByteDance), and Richard Liu (founder of JD.com) have dominated China’s top billionaire lists since 2010. Meanwhile, the tech industry is notorious for producing precarious low-income jobs, where entry-level employees are called “code-peasants (manong)” (Sun Citation2017) and “ant tribes (yizu)” (He and Mai Citation2015), not to mention assembly-line workers being subjected to slave-like conditions in hardware manufacturing (Qiu Citation2016). The digital economy in China, like elsewhere, produces a few winner-take-all champions, while large numbers of small traders and ordinary folks lose out. It is hence unsurprising that, among all economic sectors, the Chinese state selected tech as one of the first industries to test out its formal and informal measures of wealth redistribution.

The policy discourse of “virtual economy serving substantive economy” resulted from the phenomenal platform-economy bubble of the 2010s that occurred globally due to quantitative easing, super-low interest rates, and popular belief about the growth potentials of tech companies and their stock prices. In China, the bubble further inflated because the official line was to increase domestic consumption as part of the effort to resolve the problem of overproduction, while the “Internet+” policy—designed to use digital tools to assist and transform traditional sectors such as agriculture, manufacture, transportation, and banking—turned out to divest resources to exchange-value capital accumulation (e.g. cryptocurrency) away from traditional sectors, i.e. the “substantive economy” that meets use-value market demands. The Chinese authorities faced multiple crises, especially in internet finance, which in reality led to not only economic waste but also risks of social unrest (Tan and Hassan Citation2019). Beijing subsequently pulled the plug for Bitcoin and other tech bubbles, while stressing that digital platforms must serve traditional sectors to form synergies of sustainable growth, rather than the expansion of “virtual economy” at the expense of the “substantive.”

It was on the basis of these two narratives that numerous regulatory and legal measures emerged in recent years, from antitrust investigations since 2020 to the new data security and personal information laws of 2021. The billiard-ball model of offensive realism may help explain some of Beijing’s decisions such as disallowing Chinese tech companies to go public on NYSE and the nurturing of China’s own independent semiconductor industry. But it is ultimately the endogenous dynamics of the Chinese society and the Chinese digital industries, the internal crises of social inequality exacerbated by “virtual economy” bubbles, which ultimately determine the trajectory of state-led platform capitalism.

Where is China’s state-led platform capitalism heading for? Is it an effort to save Chinese capitalism, or a transitional phase, led by the CCP, to transcend digital capitalism? Will the narratives of “common prosperity” and “substantive economy” acquire “the power of words” such as “democracy, socialism, equality, liberty, &c.” during the French Revolution (Le Bon Citation1895/2009, 53)? Or perhaps this will become an instance of “growing out of plan” (Naughton Citation1995), when an initial endeavour to save Chinese-style digital capitalism unintentionally leads to digital socialism, balancing state control on the one hand and the empowerment of social groups on the other? It is too early to tell. Yet a few recent developments should be noted, and they are not limited to the western approaches to restructure Big Tech “cloud empires” through antitrust regulation or European-style “bourgeois revolution” (Lehdonvirta Citation2022). Neither are they a simple return to nationalise tech giants, known derogatorily among Chinese (neo)liberal circles as “the state marching forward and the retreat of private businesses.” Contrary to the binary thinking that one must choose between (neo)liberalism and (neo)realism, the following policy praxis—practices and discourses growing in tandem—creates room for the imagination of digital socialism at national as well as subnational and communal levels:

State-directed high-tech funding initiatives: Similar to government-sponsored venture capital funds (GVFs) in the US (Weiss Citation2014, 51–53, 67–74), China’s MII started in 2014 to supply government-directed funds that support the R&D and growth of tech enterprises. Until 2021, 1,988 government-directed funds have materialised into 6.16 trillion yuan ($870 billion) capital formation that consists of investments from state agencies at the national, provincial, and local levels as well as private investments (PEdaily.cn Citation2022). As a result, not only did China’s digital companies receive ample capital to help them grow into tech giants, the party-state including local state governments has become a main investor and stakeholder in the digital economy.

State-coordinated digital products: During COVID-19, Chinese citizens have been required to use “health code (jiankang ma)” provided by major platform companies such as Tencent and Alibaba (Liang Citation2020). Such products require data sharing across platforms along with digital assets from e-government datasets, as was the case in earlier Smart City experiments before the pandemic, which was however much limited in scale. The COVID-19 health code systems cover much larger geographical territories with more fine-grained information about people’s health status and physical movement. Although not without problems, they present new prototypes for state-coordinated digital products when private platforms and public authorities share data to meet a goal of public service.

Firm-level ownership reforms: Critical political economy analysis often starts with ownership. This can lead to a bifurcated examination in China regarding hardware manufacture and big data utilities service. China is home to the world’s largest electronics manufacture industrial system; whose assembly lines remain labour intensive. It is common that some industry leaders such as Huawei were founded, not as private firms, but as collectively-owned cooperatives or township and village enterprises (TVEs) under the purview of local states. A key reform occurred in February 2022, when the smartphone manufacturer VIVO, whose parent company BBG Electronics also owns the OPPO brand, restructured so that its employees and their union now possess 64.29 per cent of the company (Liu Citation2022). This recent instance of hybrid ownership in the hardware sector combined employee ownership and coop ownership away from the usual private ownership arrangements.

Parallel movement happens regarding big data. Among others, Zhao Yanjing of Xiamen University proposed that the big data components of platform companies should be split from the tech giants and regulated as public utilities in order for them to provide better public goods (Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Instead of full-scale nationalisation, the Chinese authorities have since October 2022 started mixed-ownership experiments by pairing up state-owned telcos with platforms, e.g. China Unicom Innovation Start-up Investment Co. plus Tencent Industrial Innovation Investment Ltd (Zhou Citation2022). After the merger, the state-owned telco Unicom has 48 per cent of the joint venture; the private company Tencent has 42 per cent; the employees have 10 per cent. Similar joint ventures are under way between China Telecom and Alibaba, and between China Mobile Shanghai and JD.com, both focusing on smart city services, e-government, and cloud computing.

It is clear that the Chinese authorities are capable of holding China’s homegrown tech giants accountable in part because of the political structure centred on the CCP, in part because Chinese government agencies at different administrative levels have formed various kinds of alliances with tech companies, their employees, and the communities involved in the hardware, software, and data-driven industries. This happened at a time when Zuckerberg argued that breaking up Facebook would benefit Chinese big tech and weaken the US (Tiku Citation2019). Intriguingly, Beijing’s approach is much more nuanced. Rather than simply breaking up the tech giants or nationalise them, China has started experimenting with ownership restructuring in a typical manner of post-Mao reform known as “crossing the river by groping the stones.” Numerous small-scale test runs have begun. Most of them may fail due to either business and market failures or the excessive strengthen of state authoritarianism based on invasive data surveillance. Of the few that succeed in the future—if there are successful ones at all—chances are that the victorious ones should be judged by the extent to which the entrepreneurs, the working people, and their employee/user communities can also hold the authorities accountable. Only then can we say China’s state-led platform capitalism has prepared the ground for a form of digital socialism that is genuinely democratic. Only then can we put the nightmare of intercapitalist warfare among the billiard balls behind us, for good.

Conclusion

While the tech war forces Beijing into a corner with undetermined consequences, China’s state-led platform capitalism is in an inchoate phase that may or may not lead to digital socialism with truly democratic control over the platforms and, more crucially, over the state bureaucracy as well. No matter how the future unfolds, the neoliberal conception of a globally connected cobweb has become obsolete. A neorealist view, especially offensive realism, has more explanatory power to account for the tech war and domestic dynamics within China. The billiard balls are back. Yet, what are the billiard balls made of? Where are they heading for? The neorealist model is limited because it ignores the internal diversity within the nation-state and multiple struggles inside the party-state; because it is still fundamentally conservative in training its focus on intercapitalist competition and imperialist conflict and conquest. It blinds us from seeing the entirety of China’s digital-media banyan tree, within which a socialist path—among other possibilities—may emerge that leads not merely the tree, but the forest as well, toward post-capitalism.

The eminent Japanese-American scholar Masao Miyoshi once wrote a provocative essay titled “Japan Is Not Interesting” (Citation2010). In it he reproached Japanese intellectuals for their conservativism in seeing everything through the mental category of Japan as a singular nation, which precludes progressive change in other collective units at the subnational and communal levels, inter alia. Borrowing from Miyoshi, shall we say “China is still interesting”? For it appears that Beijing is rejecting the terms of neoliberal structural reform dictated from Washington; that numerous experiments have been under way to transform China’s digital industries, starting from funding schemes, products coordination, and various mixed ownership reforms including from the bottom up—based on the policy discourse of “common prosperity” and “virtual economy serving substantive economy.” The true test for China in the years to come will have less to do with holding the platforms accountable than holding the party-state accountable. Democratic management of the state is a universal hurdle to move beyond neoliberal capitalism toward genuine digital socialism. If this challenge is not met collectively, the barbarism of the billiard balls model will haunt the world without end.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article was produced within the framework of the Jean Monnet Network on the European Media and Platforms Policy (EuromediApp), supported by the Erasmus+ Program ofthe European Union (2021-23). The author also acknowledges the support from the Shaw Foundation Endowment at Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2023.2200695)

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jack Linchuan Qiu

Jack Linchuan Qiu is Shaw Foundation Professor in Media Technology at the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

REFERENCES

- Barkin, Noah. 2020, March 18. “Export Controls and the US-China Tech War.” Merics. https://merics.org/en/report/export-controls-and-us-china-tech-war.

- Bottici, Chiara, and Benoît Challand. 2006. “Rethinking Political Myth.” European Journal of Social Theory 9 (3): 315--336. doi:10.1177/1368431006065

- Burton, John. 1972. World Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chen, Laurie. 2023, February 16. “What We Know About China’s Medical Reform Protests.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/what-we-know-about-chinas-medical-reform-protests-2023-02-16/.

- Cheong, Danson. 2022, October 20. “US Draws Beijing’s Ire with New Rules to Choke Off China’s Access to Chips.” The Straits Time. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/china-says-us-abusing-trade-measures-with-chip-export-controls.

- Clark, Christopher. 2012. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. New York: Harper.

- Couldry, Nick, Clemencia Rodriguez, Goran Bolin, and Julie Cohen. 2017. “Media, Communication and the Struggle for Social Progress.” Global Media and Communication 14 (2): 173–191. doi:10.1177/1742766518776679

- Creemers, Rogier. 2018. “China’s Social Credit System: An Evolving Practice of Control.” SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3175792.

- Daly, Angela, Monique Mann, and S. Kate Devitt. 2019. Good Data. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures.

- Davis, Bob, Dan Strumpf, and Lingling Wei. 2018, June 7. “China’s ZTE to Pay $1 Billion Fine in Settlement with US.” The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/zte-pays-1-billion-fine-after-allegedly-violating-u-s-sanctions-1528374558.

- Dean, Jodi. 2012. The Communist Horizon. London: Verso.

- Downing, John D. 2000. Radical Media: Rebellious Communication and Social Movements. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Farrell, Henry, Abraham Newman, and Jeremy Wallace. 2022. “Spirals of Delusion.” Foreign Affairs 101 (5): 168–181.

- Flew, Terry. 2020. “Globalization, Neo-Globalization and Post-Globalization.” Global Media and Communication 16 (1): 19--39. doi:10.1177/1742766519900329

- Freedman, Des. 2008. The Politics of Media Policy. Cambridge: Polity.

- Gray, Joanne. 2021. “The Geopolitics of ‘Platforms’.” Internet Policy Review 10 (2): 1--26. doi:10.14763/2021.2.1557

- He, Yu, and Yinhua Mai. 2015. “Higher Education Expansion in China and the ‘Ant Tribe’ Problem.” Higher Education Policy 28 (3): 333–352. doi:10.1057/hep.2014.14

- Hong, Yu, and Shuai Chen. 2022. ““Digital Cold War” Reconsidered: From Internet Geopolitics to the Discourse of Geopolitics.” Journalism and Communication Research 10: 47–63. (in Chinese). doi:10.12677/JC.2022.102009

- Jacobson, Louis. 2019, May 14. “Who Pays for US Tariffs on Chinese Goods? You Do.” Politifact. https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2019/may/14/donald-trump/does-china-mostly-pay-us-tariffs-rather-us-consume/.

- Jee, Haemin. 2022. “Credit for Compliance: How Institutional Layering Ensures Compliance in China.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Stanford University.

- Jiang, Tiancheng. 2014. “The Qihoo/Tencent Dispute in the Instant Messaging Market: The First Milestone in the Chinese Competition Law Enforcement?” World Competition 37 (3): 369–389. doi:10.54648/WOCO2014033

- Jiang, Wenyan. 2022, October 18. “Why Taiwan’s Semiconductor Industry is a Key Battleground? The Challenge of Taiwan in Global Tech War.” The Initium. https://theinitium.com/article/20221018-opinion-taiwan-us-china-chips/ (in Chinese).

- Keohane, Robert, and Joseph Nye. 1977. Power and Interdependence. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

- Koppell, Jonathan. 2005. “Pathologies of Accountability: ICANN and the Challenge of ‘Multiple Accountabilities Disorder’.” Public Administration Review 65 (1): 94--108. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00434.x

- Kokas, Aynne. 2023. Trafficking Data: How China is Winning the Battle for Digital Sovereignty. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Le Bon, Gustave. [1895] 2009. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. Digireads.com Publishing.

- Lee, Jyh-An. 2018. “Hacking Into China’s Cybersecurity Law.” Wake Forest L. Rev. 53: 57–104. http://wakeforestlawreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/w05_Lee-crop.pdf

- Lehdonvirta, Vili. 2022. Cloud Empires: How Digital Platforms Are Overtaking the State and How We Can Regain Control. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Liang, Fan. 2020. “COVID-19 and Health Code: How Digital Platforms Tackle the Pandemic in China.” Social Media + Society 6: 3. doi:10.1177/2056305120947657.

- Lin, Runhui, Jean J. Chen, and Li Xie. 2020. “Alibaba Group—The Evolution of Transnational Governance.” In Corporate Governance of Chinese Multinational Corporations, edited by Ruihui Lin, Jean J. Chen, and Li Xie, 5–44. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Liu, Zhiying. 2022, February 21. “Registered Capital of VIVO Holdings Increased by 64.29% to 1.15 Billion Yuan.” Tencent News. https://new.qq.com/omn/20220221/20220221A017Y200.html (in Chinese).

- Luo, Jianxi. 2022. “Close the Gap in the US CHIPS and Science Law.” Nature 610: 34. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03122-8

- Mearsheimer, John. 2014. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. 2nd edition. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Miyoshi, Masao. 2010. Trespasses: Selected Writings. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Nanni, Riccardo. 2022. “Digital Sovereignty and Internet Standards.” Information, Communication & Society 25 (16): 2342--2362. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2022.2129270

- Naughton, Barry. 1995. Growing Out of the Plan: Chinese Economic Reform, 1978–1993. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Negro, Gianluigi. 2020. “A History of Chinese Global Internet Governance and Its Relations with ITU and ICANN.” Chinese Journal of Communication 13 (1): 104–121. doi:10.1080/17544750.2019.1650789

- Nordenstreng, Kaarle, and Daya Thussu, eds. 2015. Mapping BRICS Media. London: Routledge.

- Pashakhanlou, Arash. 2014. “Waltz, Mearsheimer and the Post-Cold War World.” International Politics 51: 295--315. doi:10.1057/ip.2014.16

- PEdaily.cn. 2022, March 16. “Data Summary of Government-Directed Funds in 2021.” https://news.pedaily.cn/202203/488457.shtml (in Chinese).

- Pettypiece, Shannon, and Andrew Mayeda. 2017, March 7. “China’s ZTE Pleads Guilty in US on Iran Sanctions Settlement.” Bloomberg.

- Qiu, Jack L. 2016. Goodbye iSlave. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Qiu, Jack L. 2022. “Data Power and Counter-Power with Chinese Characteristics.” In New Perspectives in Critical Data Studies, edited by Andreas Hepp, Juliane Jarke, and Leif Kramp, 27–46. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Qiu, Jack L., and Hongzhe Wang. 2021. “Radical Praxis of Computing in the PRC: Forgotten Stories From the Maoist to Post-Mao Era.” Internet Histories 5 (3-4): 214–229. doi:10.1080/24701475.2021.1949817

- Rennie, Ellie. 2006. Community Media: A Global Introduction. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Raymond, Mark, and Laura DeNardis. 2015. “Multistakeholderism: Anatomy of An Inchoate Global Institution.” International Theory 7 (3): 572--616. doi:10.1017/S1752971915000081

- Rogers, Katie, and Cecilia Kang. 2021, June 9. “Biden Revokes and Replaces Trump Order That Banned TikTok.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/09/us/politics/biden-tiktok-ban-trump.html.

- Rosenau, James. 1980. The Study of Global Interdependence: Essays on Transnationalisation of World Affairs. Asbury: Nichols Publishing Co.

- Sheehan, Matt. 2022, October 27. “Biden’s Unprecedented Semiconductor Bet.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/10/27/biden-s-unprecedented-semiconductor-bet-pub-88270.

- Shin, Francis. 2022, Jan 31. “What’s Behind China’s Cryptocurrency Ban?” World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/01/what-s-behind-china-s-cryptocurrency-ban/.

- Sun, Ping. 2017. “Programming Practices of Chinese Code Farmers.” China Perspectives 4: 19–27. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.7463

- Tabeta, Shunsuke. 2022, February 2. “China to Launch Chipmaking Platform As It Targets Intel and AMD.” Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Electronics/China-to-launch-chipmaking-platform-as-it-targets-Intel-and-AMD.

- Tan, Zhongkai, and Ahmed F.S. Hassan. 2019. “Internet Finance and Its Potential Risks: The Case of China.” International Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business 4 (20): 45–51. http://www.ijafb.com/PDF/IJAFB-2019-20-06-04.pdf

- Tang, Min. 2020. “Huawei Versus the United States.” International Journal of Communication 14: 4556--4578. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/12624/3204.

- Tian, Dexin. 2008. “The USTR Special 301 Reports: An Analysis of the US Hegemonic Pressure Upon the Organizational Change in China’s IPR Regime.” Chinese Journal of Communication 1 (2): 224–241. doi:10.1080/17544750802288032

- Tiku, Nitasha. 2019, May 23. “Big Tech: Breaking Us Up Will Only Help China.” Wired Magazine. https://www.wired.com/story/big-tech-breaking-will-only-help-china/.

- Van Dijck, José. 2021. “Seeing the Forest for the Trees: Visualizing Platformization and Its Governance.” New Media & Society 23 (9): 2801–2819. doi:10.1177/1461444820940293

- Viswanatha, Aruna, Dan Strumpf, Jacquie McNish, and James Adreddy. 2021, September 27. “Huawei Executive’s Return to China.” The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/huawei-executives-return-to-china-how-the-deal-came-off-11632784295?mod=article_inline.

- Waltz, Kenneth. 1979. Theory of International Politics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Weiss, Linda. 2014. America Inc.? Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Wendt, Alexander. 1992. “Anarchy Is What States Make of It.” International Organization 46 (2): 391–425. doi:10.1017/S0020818300027764

- West, Sarah. 2018. “Searching for the Public in Internet Governance.” Policy & Internet 10 (1): 22–42. doi:10.1002/poi3.143

- Whalen, Jeanne. 2022, May 17. “China Cut Tech Exports to Russia after US-led Sanctions Hit.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/05/17/china-russia-tech-exports/..

- Wolfers, Arnold. 1951. “The Pole of Power and the Pole of Indifference.” World Affairs 4 (1): 39–63. doi:10.2307/2008900

- Yuan, Li. 2022, June 10. “A Chinese Entrepreneur Who Says What Others Only Think.” The New York Times. https://nyti.ms/3QfvJvm.

- Zhao, Yuezhi. 2007. “After Mobile Phones, What? Re-Embedding the Social in China’s Digital Revolution.” International Journal of Communication 1: 92–120. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5/20

- Zhao, Yuezhi. 2014. “The Life and Times of ‘Chimerica’: Global Press Discourses on US–China Economic Integration, Financial Crisis, and Power Shifts.” International Journal of Communication 8: 419–444. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/download/2503/1073

- Zhao, Yanjing. 2021a. “Platform Economy and Socialism: On the Essence of the Ant Group Incident.” Journal of Political Economy 20: 3–12. (in Chinese).

- Zhao, Yanjing. 2021b. “Platform Economy: In Search for Optimized Property Boundaries.” Exploration and Debate 376: 16–19. (In Chinese.)

- Zhao, Yuezhi, and Jing Wu. 2020. “Understanding China’s Developmental Path: Towards Socialist Rejuvenation?” Javnost – The Public 27 (2): 97–111. doi:10.1080/13183222.2020.1727274

- Zhong, Raymond. 2020, November 6. “In Halting Ant’s IPO, China Sends a Warning to Business.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/03/technology/ant-ipo-jack-ma-summoned.html.

- Zhou, Xiaobai. 2022, November 2. “Tencent VP Now Serves on the Board of China Unicom.” Techweb. http://www.techweb.com.cn/it/2022-11-02/2909731.shtml (in Chinese).