Abstract

This research examines who controls the international Internet using a multi-level network analysis. Internet provider (IP) address ownership data obtained from TeleGeography (http://www.telegeography.com/) are used to describe the structure of the international network of private companies and Internet service providers (ISPs). The results indicate that 16 companies, headquartered in seven countries, are at the center of the network, each accounting for more than 1% of international Internet connections. Level 3 Communications, based in the United States, is at the center of the network. The United States is the most central nation in the ownership network. American corporations account for almost 40% of the international links. A cluster analysis found a single group centered about the United States. The ownership network is consistent with other measures of the international Internet network. Its structure replicates and maintains the global hierarchy as suggested by world system and globalization theory. Policy implications are discussed.

The twenty–first century has seen a change in the dependence on networks for individuals and organizations (van Dijk Citation2006). The term network society has been used to describe the influence of new communication and information technologies on global society (Castells Citation1996, Citation2000, Citation2004). Through convergence, or the increased concentration of ownership, there has been an integration of telecommunications, data communications, and mass communication into a single medium (Chon et al. Citation2003). The information superhighway is one example where public and private networks of data, telecommunication, and mass communication converge to create multifunctional, high-speed networks. These networks provide a multitude of information channels that create a participatory and interactive global communication environment (Barnett Citation2001; Barnett & Park Citation2012). While these computer networks allow the public greater access to information and a growing voice in democratic decision-making, those who benefit the most from the expanding commercialization of the technology are those who control the information technologies (Sun & Barnett Citation1994).

The Internet – the network of all networks – has fueled the changes in information technology use and this shift has led to an evolution in the technology itself. The technology and human beings are continually adapting and mutually changing each other. Therefore, a better understanding of the technology, its use, and who controls it, can provide greater insight into how society, in line with communication technology structures, will change. The notion of Internet control has been described as having three dimensions: (1) access to the Internet, including means of access and control of the infrastructure; (2) functionality or quality of the connections and the technical protocols of Internet communications; and (3) Internet activity which includes filtering, surveillance, and attempts to shape social and political discourse (Eriksson & Giacomello Citation2009). Recent substantial changes in provider interconnection strategies have had significant impacts on Internet-scale application design, backbone engineering, and research (Labovitz et al. Citation2010). Current Internet policy primarily focuses on intellectual property and privacy issues in order to facilitate electronic commerce for economic development (Drake Citation2005; Marsden Citation2000). Internet traffic research has focused on the structure of Internet flows through the examination of traffic measures on an individual network (Fraleigh et al. Citation2003), international hyperlinks (Barnett, Chon, & Rosen Citation2001; Barnett & Park Citation2005, Citation2012), bilateral bandwidth (Barnett & Park Citation2005, Citation2012), specific website use by individual countries (Barnett & Park Citation2012), and provider network structures (Gorman & Malecki Citation2000).

This research examines the ownership of the international Internet connections using a multi-level network analysis. Specifically, it asks, what companies own the international Internet traffic backbone? From which countries do these companies operate? What are the social and policy implications of the Internet network ownership structure?

Society and the network

The increase in communication across international borders has ushered in the rapid global diffusion of values, opinions, ideas, and technologies. The world has become globally connected through economic, media, social, and technological networks. The idea of the state and the nature of economic interdependence are shifting due, in part, to these networks and the process of globalization.

Globalization, defined as: ‘the integration of states through increasing contact, communication, and trade to create a holistic, single global system in which the process of change increasingly binds people together in a common fate’ (Kegley & Wittkopf Citation2001, p.41) is an inherent part of modernization (Giddens Citation1990), where nations become networked across the globe. Although the process of globalization has been occurring for centuries, the advent of satellite networks, mobile telephones, and the Internet have set apart this era of globalization.

Critics highlight the underlying continuity of capitalism in globalization (Scholte Citation2005). Competition has intensified, affecting labor markets in the poorest areas, through the hasty integration of markets and the growing global interdependence created by multinational corporations (Kegley & Wittkopf Citation2001). World-system theory suggests that a single world economy has emerged where divisions take place between core (advanced capitalist states), periphery (developing states), and semi-periphery (countries moving up from the periphery and declining countries moving down from the core) nations (Chase-Dunn & Grimes Citation1995; Wallerstein Citation1974). Although there is debate regarding the classification of nations, a nation's membership in one of the categories tends to be stable over time (Smith & White Citation1992).

Media networks add a new dimension of inequality when considering physical access as well as digital skills and usage (van Dijk Citation2006). Specifically, van Dijk (Citation2006) describes the digital divide in terms of motivational access, material or physical access, skills access, and use access. The digital divide has also been described to refer to a global divide (Internet access between societies), a social divide which refers to information access within nations, and the democratic divide that concerns those who use and do not use the technology (Norris Citation2001). This research focuses on the digital divide of ownership not access, however ownership may affect access.

The economic side of globalization is integrating financial markets through a combination of centralization, free trade agreements, and the Internet, which is generating new and unprecedented levels of wealth for the established elite while simultaneously producing greater inequalities (Warf Citation2003). The advantage is seen as naturally given to elites who profit and monopolize the industry, and therefore, providing little, if any, gain for new and smaller competitors. This is in line with Manuel Castells (Citation2011) identification of power in networked society. He identifies four different forms of power: (1) networking power: the power of the organizations that constitute the core of the global network society; (2) network power: the power that results from the imposition of the rules of inclusion in the network; (3) networked power: the power of social actors in the network over other social actors; and (4) network-making power: the power to program specific networks in line with the interests and values of the actors in those networks, and the power to exchange different networks following the strategic alliances between dominant actors of various networks. Castells (Citation2011) establishes owners of global multimedia corporate networks as power holders and information gatekeepers.

The global network

Telephones and computer networks provide a multitude of channels for national and international interaction (Barnett Citation2001; Barnett & Park Citation2012). These two-way communication media also allow for a unification of different communication channels into various electronic communication networks, connecting all levels of information flow that are essential for global interaction. Some nations have Internet exchange points operated by a state provider, but are more often operated by private companies (Seo & Thorson Citation2012). These exchange points connect the national network infrastructure to global flows of information.

A longitudinal analysis of the international telecommunications network found that the network has become denser, more centralized, and very integrated (Barnett Citation2001, Citation2012). A recent snapshot of the international telecommunications network showed an increase in network connectivity within peripheral nations and a decentralized, more highly clustered structure (Lee et al. Citation2007). An examination of the international Internet bandwidth shows a correlation with Internet traffic (Barnett & Park Citation2005, Citation2012), and Park, Barnett, & Chung (Citation2011) report exponential growth of the international hyperlink network.

Using network analysis to examine and identify the structure of the Internet, specifically connections among countries, allows for a multi-level analysis. Barnett and Park (Citation2005) found that most countries have a direct Internet connection with the USA through inter-domain hyperlinks and Internet bandwidth. An analysis of the structure of international Internet traffic found the international Internet structure significantly related to international telephone, trade, and science flows (Barnett et al. Citation2001). A relationship between national culture and the international Internet structure of linkages has also been established (Barnett & Sung Citation2005). A map of the USA Internet backbone shows a rapidly changing telecommunications infrastructure (Gorman & Malecki Citation2000). An assessment of the spatial organization of the commercial Internet backbone displays an increasingly competitive privatized market for service conditions where some locations have better access and connectivity than others (O'Kelly & Grubesic Citation2002).

Internet service providers (ISP's), which vary in size and function, are the networks that comprise the Internet. A functional classification of ISP's yields four types: (1) transit backbone ISP's; (2) downstream ISP's; (3) online service providers; and (4) website hosting firms (Cukier Citation1998). All of these types of ISP's rely, to a large extent, on transit backbone ISP's. These backbone providers, in network terms, are called autonomous systems (ASs). Each AS independently sets its own policies and determines its own network structure and they only become interconnected when forming the Internet (Gorman & Malecki Citation2000).

Because networks do not follow geographical or national boundaries, the amount of bandwidth between two locations determines Internet performance and efficiency rather than physical distance between locations. The cost of infrastructure, connections, and regulations also affects Internet routing. This study analyzes Internet ownership networks at the company and nation-state levels, in line with the strong historical foundations of telecommunications at the national level. Although the Internet and telecommunications have different origins and evolutionary histories, they are related and comparable in their function of providing methods of electronic network communication (Barnett et al. Citation2001; Simpson Citation2010).

Most Internet policy has focused on creating the conditions for the growth of e-commerce, protecting copyrights, and safeguarding consumers’ privacy (Marsden Citation2000; Stewart, Gil-Egui, & Pileggi Citation2004). As a result, international agencies involved with Internet development deal mainly with technical and economic aspects. Organizations such as Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), and World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) work toward increasing commodification and commercialization of Internet structure and activities (Drake Citation2005; Stewart et al. Citation2004). While this has helped further diversity of participation and content it has also advanced problems arising from varying levels of global penetration and infrastructure development that hinge on the governmental and economic policy agendas of various nations.

Without governing oversight on ownership to access and differing national policy agendas, greater access to resources is not managed or equally distributed. Power is a function of dependence on others in a network. As such, greater power is associated with location in the network to the extent if offers greater access to valuable information and resources (Monge & Contractor Citation2003). Several studies have equated network centrality with different sources of power: (1) closeness, the extent to which organizations can reach all others through minimum intermediaries or access of resources (Brass Citation1984; Sabidussi Citation1966); and (2) betweenness, the extent to which an organization lies between those not connected or control of resources (Freeman Citation1977, Citation1979). ‘Power relationships are the foundation of society, as institutions and norms are constructed to fulfill the interests and values of those in power’ (Castells Citation2011, p.773). Based on patterns of ownership connections between countries we can gain insights about what international policies need to be developed in order to ensure privacy, the free flow of information and an equitable distribution of control.

METHODS

Network analysis

Network analysis is a set of research procedures for identifying structures in systems (Rogers & Kincaid Citation1981; Wasserman & Faust Citation1994). The focus in network analysis is on the relationship among its components rather than on individual attributes, which allows researchers to focus on the way in which relations are organized (Emirbayer Citation1997; Emirbayer & Goodwin Citation1994; van Poucke Citation1979). In addition to taking into account both present and absent ties, network analysis also considers the variation in intensity and strengths of the relations (Knoke & Yang Citation2008). It has been employed to examine an extensive variety of flows and structures, but relevant to this study, network analysis has investigated the structure of the World Wide Web (Barnett & Park Citation2012; Park & Thelwall Citation2006), international telecommunications (Barnett & Choi Citation1995; Barnett Citation2001, Citation2012; Lee et al. Citation2007), the patterns of communication among nation-states (Barnett & Lee Citation2001; Kim & Barnett Citation2007), the structure of the international hyperlink network (Barnett et al. Citation2001; Barnett & Park Citation2005, Citation2012) and bilateral bandwidth (Barnett & Park Citation2005, Citation2012).

The basic network data set is an n × n matrix S, where n equals the number of nodes in the analysis, where sij is the measured relationship between nodes i and j. A node is the unit of analysis, an individual or higher-level component, in this case, the set of nation-states that comprises the international Internet. There are a number of indicators of a node's position in the network. The Gini coefficient measures the inequality among values of a frequency distribution where a zero score expresses perfect equality and a score of one expresses maximum inequality among values. Connectedness or degree is a node's number of links or the sum of the strength of a node's ties to the other nodes. Degree centrality refers to the number of non-directional ties associated with a node. The share is a node's proportion of ties in the network and indicates the amount of the market accounted for by a specific node.

Centrality is an indicator of the importance, prominence, or power in a network (Knoke, & Yang Citation2008; Monge & Contractor Citation2003). Degree, one indicator of centrality, is the mean number of links or the sum of link strengths required to reach all other nodes in a group such that the lower the value the more central the node. As noted before, network centrality has been equated with different sources of power. Betweenness measures the control of resources because it illustrates the degree to which a node is directly connected to others that are not directly connected to each other (Freeman Citation1977, Citation1979). It is defined as the proportions of all paths linking nodes j and k that pass through i. The betweenness of i is the sum of all paths where i, j, and k are distinct. Betweenness measures the number of times a node occurs on a path (Freeman Citation1979). Nations with higher betweenness centrality are in a better position to create new exchange links with others.

Another measure, Eigenvector centrality measures the overall influence or power of a node in the network (Bonacich Citation1987). It is defined as follows. Given a non-directional sociomatrix A, the centrality of node i (denoted as ci) is given by , where α is a parameter. The centrality of each node is therefore determined by the centrality of the nodes to which it is linked. The centralities will be the elements of the corresponding eigenvector. It assigns relative scores to all nodes in the network such that great weight is placed on ties to more central nodes. Companies and/or nations with higher eigenvector centrality scores have the ability to align themselves with other central (powerful) players in the network.

Density refers to how extensive or complete the network's relations are and is a measure of a group's cohesion (Wasserman & Faust Citation1994). Sparse networks have few links, while dense networks are highly connected. Density is defined as the actual number of links divided by the number of possible links [n(n – 1)/2]. Cluster analysis may be used to identify groups or clusters of nodes. Hierarchical cluster analysis groups members into subsets where the members are relatively similar or structurally equivalent. This analysis employed the average distance method of hierarchical clustering.

The procedures described above each indicate the state of the international Internet backbone at one point in time. UCINET (Borgatti, Everett, & Freeman Citation2002) was used to calculate network measures and diagrams were graphically represented using UCINET's component program NetDraw (Borgatti Citation2002). Visual representations are important to facilitate the understanding of networks and help illustrate the results of the analysis. Multiple measures were employed to provide varied descriptions of the network's structure and to prevent bias interpretations based on the use of a single measure.

Data description

The Internet is composed of many kinds of AS. Each AS administers a set of routers (Stewart Citation1999) with different routing protocols (Serbedzija Citation2013). The AS are identified through 16-bit numbers or autonomous system numbers (ASNs; Feamster & Balakrishnan Citation2003). An ASN's number of connections is the most straightforward metric as the number of connections identifies the number of unique ASNs to which an ASN is directly paired. ISP provide access to the Internet for a fee. Upstream ISPs are usually large, Tier 1, providers to smaller ISPs, or downstream providers (Chen & Stewart Citation1999). Upstream providers are the ‘wholesalers’ of connection access (Huston Citation1998).

Ownership data on the upstream providers of all downstreams was gathered from TeleGeography – Global Internet Geography (Citation2011). Upstream providers were based on the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), routing tables that are used to direct traffic across networks that are identified by ASNs. The data collection resulted in a two-mode bipartite matrix (country [191] by company [113], where each cell aij was the number of ASNs for country i owned by company j), for the bandwidth capacity countries and companies share. The matrix was premultiplied by its transpose to create a symmetrical country (191) by country matrix in which each cell indicates the total number of companies shared by a pair of countries and a company (113) by company matrix, where each cell indicates the total number of countries two companies share. The data were aggregated to a country total for the companies that are based in a country.

RESULTS

Company-level

The links in the network are concentrated in a few companies. Of the 113 companies that operate as upstream providers, 74 (65.5%) have no international links, and only 16 provide greater than 1% of connections between two countries. The Gini-coefficient for the distribution of IP addresses per company is .919. The density of the network is .059. This is a very sparse network, where very few companies control the international Internet network.

presents the 113 companies’ centralities and the number of countries for which each company provides Internet access. At the center of the network of ownership are ten companies: Level 3 (USA), Century Link (USA), Telia Sonera (Sweden), AT&T (USA), Cogent Communications (USA), Verizon Business (USA), XO Communications (USA), Hurricane Electric (USA), Tata Communications (India), and NTT Communications (Japan). The most central company is Level 3, with a 22.3% share of the network, followed by Century Link 8.7%, Telia Sonera 8.5%, AT&T 7.8%, and Cogent with 6.7% of the network. The top five companies hold 54% of the network share, the top ten share 77.1% of the network, and the top 18 companies share 92.8% of the network. The shares of companies were distributed by an exponential decay function (R2 = .674, p < .000) moving to zero faster than a power curve.

Table 1 – Company Centralities.

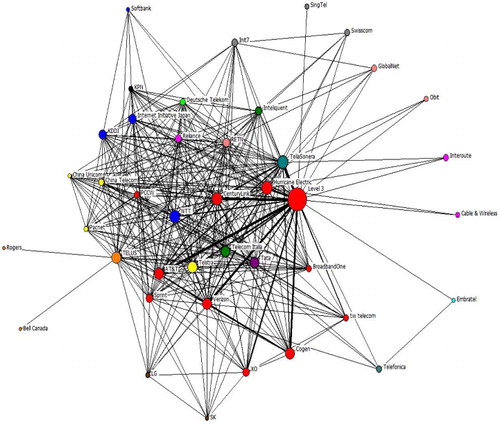

The most central companies (greater than two standard deviations greater than the mean) in terms of eigenvector centrality are Level 3, Century Link, Telia Sonera, and AT&T, three of which are US based companies. In terms of betweenness centrality, Level 3 is again the most central, followed by two other US based companies, Cogent and Hurricane Electric. Other companies that are greater than two standard deviations greater than the mean in betweenness are Tel Italia (Italy), Telia Sonera (Sweden), NTT (Japan), and RETN (Russia). graphically displays the international Internet ownership network, showing the prominent companies, their connections and the country where they are based.

Note: The size of the nodes is its total bandwidth. Link strength is line thickness. Color represents country, USA red, China yellow, Sweden teal, India purple, Japan blue, Korea brown, UK magenta, Germany light green, Canada orange, Italy dark green, Brazil light blue, and Russia pink.

National level

The companies were aggregated to the country level creating a new network of the countries of the ISPs by the countries in which these companies base operations. presents the measures of centralities for the countries. The centrality of the countries can be explained by the number of companies with a high level of share that operate and/or are headquartered in that country. The results indicate that the USA is the most central nation, with 39% share of the ownership network. Following the USA are Sweden with a 16% share, China 10%, Japan 10%, and Italy and India with 7% each. Internet network ownership at the national level is very concentrated (Gini = .94). Eigenvector centrality results are similar. For betweenness centrality, the most central countries are the USA, Italy, Sweden, and Russia. Most international Internet traffic flows through carriers based from these countries.

Table 2 – Country Centralities.

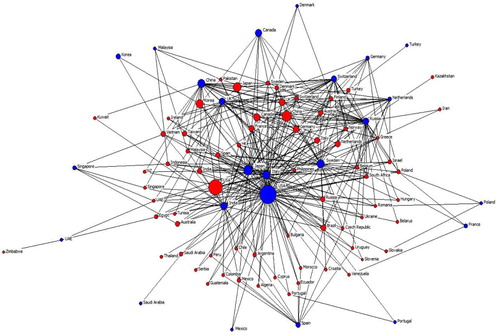

presents a 2-mode network with the companies aggregated to the national level and the countries to which they provide service. The USA is most central in the network. Also, the figure shows that 124 countries own no international Internet providers and only 18 countries have at least 1% domestic ownership of the international Internet network.

Note: Blue indicates the companies aggregated to the national level, red the countries they serve. The size of the nodes is its total bandwidth. The shown links are all equal to or greater than the mean link strength. The companies of a country, shown here, connect at least two countries.

DISCUSSION

The results of this research indicate that a limited number of companies dominate international Internet flows. The most central companies with the largest share of the network are Level 3, Century Link, TeliaSonera, AT&T, and Cogent.Footnote1 Six of the top ten companies are headquartered in the USA. Further, on all indicators, the USA is the most central nation in the ownership network with almost 40% of the share. Following the USA in ownership are Sweden, China, and Japan. The vast majority, 124 countries do not have any international Internet providers based in the country, and only 18 have at least 1% domestic ownership of the international Internet network.

The structure of the international Internet ownership network is consistent with previous findings on the structure of the international Internet (Barnett & Park Citation2012), indicating the validity of the reported findings. The Internet ownership network correlates with bilateral bandwidth between countries (2011; r2 = .40, p < .001), telephone calls (2010; r2 = .28, p < .001), and the proportion of a country's 100 most used websites shared with other countries (r2 = .67, p < .001) (Barnett & Park Citation2012).

The reasons for the dominance of the USA are unclear. One reason may be historical, that is, the Internet developed in the USA for communicating military information to its forces around the world. Thus, USA carriers would operate the international bandwidth connections. Another reason may be economic. These results are in line with world system theory, indicating vertical interaction between center and periphery nations with periphery-to-periphery interaction missing. Also, the structure has remained relatively stable with only China and India moving from the periphery toward the core. A shift can be seen as an aspect of globalization with production modes changing from industrial to informational.

Policy implications of the Internet's structure and development have been previously discussed from a world cities perspective (Brunn & Dodge Citation2001; Malecki Citation2002; Moss & Townsend Citation2000). At the nation-state level, these results indicate that companies from core countries are the most central in the network and that they dominate the international Internet network. This suggests concentrated ownership of the international Internet network, which can have serious implications for privacy and the free-flow of information through the Internet. While the USA has not monitored the competitive aspects of the Internet backbone interconnection relationships, on 27 January 2011, Egypt effectively shut down four major ISPs (Singel Citation2011). This is an example of the increased preoccupation, by some governments of nation-states, to control international computer networking in the name of state and national security (Franda Citation2001). It is also an indicator of sovereignty issues that may arise between backbone owners and the nation-state governments from which they operate from.

Since there is no legal authority or governing body that determines Internet connections, access, or control, the international Internet network is self-regulated by the network owners in their perceived best interests. As the core of the global Internet infrastructure, not only ethereal ‘cyberspace’ alone but also the physical infrastructure or backbone, is based in the USA, infrastructure expansion in developing countries can be limited based on the economic and/or political interests of the backbone owners. A developing country, as shown by this analysis, is not likely to have its own backbone network making basic interconnections more difficult. Connections, in a case like this, will require extensive backhauling of traffic from interconnection points located in developed countries who possess the infrastructure and capital for its expansion (Roycroft & Anantho Citation2003). For this reason, Europe is an attractive upstream destination for Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. It offers geographic proximity, low IP transit prices, and access to large carriers and major Internet exchanges (Telegeography Citation2013).

Telecommunications is operating in a privatized and liberalized global market where there is no formal forum or organization to regulate principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures (Drake Citation2000). Critics challenge the idea that the Web serves as an alternative democratic medium, pointing instead to the Web's growing commercialism, concentrated control of ISPs, and the increased presence of traditional media providers on the Web (Baker Citation2007; Blevins Citation2002; Consalvo Citation2003; Cooper Citation2003; Patelis Citation2000; Samoriski Citation2000). Also, at this time, there is no international agency that regulates patterns of Internet ownership, similar to that of the role played by the USA's Federal Communication Commission (FCC). For example, large owners can dictate pricing for and access by smaller owners. Similarly, in light of the recent National Security Agency revelations, proposals for a transnational legal framework to address security, access, and ownership of the backbone become more pressing. Also, Internet policy's focus on intellectual property and privacy issues in order to assist electronic commerce for economic development, rather than on ownership of the pathways, can amass to significant political power as ‘space of flows’ replaces ‘control of territory’ in terms of importance and influence (Deibert Citation2002). Beyond issues of privacy, information flows, and access there is the issue of the digital divide. Unequal access reinforces existing inequalities (van Dijk Citation2006). This inequality has been described as ‘corporate domination of both the media system and the policy-making process’ (McChesney Citation2004, p.7).

The current debate regarding the proposed cable merger of Time Warner and Comcast – which also happen to be two of the largest broadband ISPs – illustrates the role of the FCC in determining if this consolidation is detrimental to American society. Similar potential problems involving broadband ownership do not have an international regulatory agency akin to the FCC that can assess the impact of ownership concentration on user accessibility and service. ICANN or the International Telecommunication Union could serve as a regulating agency, however, as Muller (Citation2010) explains, the roles and needs of the various stakeholders makes it difficult to come to an agreement about ownership governance.

This study affirms Simmons' (Citation2010) proposal for the construction of a critical theory of the Internet. Critical and cultural theories of the Internet could help define the role of the Internet in society, while political economy theory could explain how the Internet functions in a democratic society (Fuchs Citation2009). This would allow researchers to assess the power relations innate in media production, distribution, and consumption (Mosco Citation1996). Critical theorists argue that corporate media firms act as purveyors of American culture across the globe which serve to reaffirm the interests and values of these multinational firms (McChesney Citation2001). Some political economy theory posits that media content advances the political and economical interests of those that produce and distribute content (Skinner, Compton, & Gasher Citation2005). Ownership of the international Internet network has economic and political implications that may further widen current disparities.

Multilateral telecommunications rules may be determined by trade institutions such as the WTO and private sector-led bodies due to the lack of a global regulatory organization. While the authors have not inferred malevolent intent, the restricted flow of information and the use of the Internet for national political gain, such as spying on industrial or political ‘competitors’, could occur as backbone owners comply with nation-state telecom agreements in order to maintain their licensing (Singel Citation2011). With most of the infrastructure of the Internet owned and run by the private sector, can we rely on them to consider the public good? Without international regulation, it is possible that those with the largest stake in the market will be the ones to regulate access and growth creating the real possibility of an Internet backbone monopoly.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jeanette B. Ruiz

Jeanette B. Ruiz (MA, California State University, Sacramento) is a Doctoral Student in the Department of Communication with a concentration in communication/social network analysis at the University of California, Davis. Her work examines the international Internet and the impact of social networks on public health communication.

George A. Barnett

George A. Barnett (PhD, Michigan State University, 1976) is Professor and Chair of Communication at the University of California, Davis. He has written extensively on organizational, mass, international, intercultural and political communication, as well as the diffusion of innovations. His current research focuses on international information flows and their role on socioeconomic and cultural change, and the process of globalization.

Notes

1. After the completion of this analysis, Level 3 acquired tw telecom (an additional 2.3% of the share for a new total of 24.6% share). This is an example of growing concentration in the ownership network (Telegeography Citation2014).

REFERENCES

- Baker, C.E. (2007) Media concentration and democracy: Why ownership matters, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Barnett, G.A. (2001) ‘A longitudinal analysis of the international telecommunications network: 1978–1996’, American Behavioral Scientist, 44(10), pp.1638–55.

- Barnett, G.A. (2012) ‘Recent developments in the global telecommunication network’, Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, pp.4435–44.

- Barnett, G.A. & Choi, Y. (1995) ‘Physical distance and language as determinants of the international telecommunications network’, International Political Science Review, 16, pp.249–65.

- Barnett, G.A., Chon, B., & Rosen, D. (2001) ‘The structure of the Internet flows in cyberspace’, Networks and Communication Studies, 15(1–2), pp.61–80.

- Barnett, G.A. & Lee, M. (2001) ‘Issues in intercultural research’, in W.B. Gudykunst & B. Moody (eds) Handbook of international and intercultural communication, 2nd ed. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp.275–90.

- Barnett, G.A. & Park, H.W. (2005) ‘The structure of international Internet hyperlinks and bilateral bandwidth’, The Annales des Telecommunications, 60, pp.1115–32.

- Barnett, G.A. & Park, H.W. (2012) ‘Examining the international Internet using multiple measures: New methods for measuring the communication base of globalized cyberspace’, Quality and Quantity, 48, pp.563–7510.1007/s11135-012-9787-z.

- Barnett, G.A. & Sung, E. (2005) ‘Culture and the structure of the international hyperlink network’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(1), pp.217–3810.1111/j.1083–6101.2006.tb00311.x.

- Blevins, J.L. (2002) ‘Source diversity after the telecommunications act of 1996: Media oligarchs begin to colonize cyberspace’, Television & New Media, 3(1), pp.95–112.

- Bonacich, P. (1987) ‘Power and centrality: A family of measures’, American Journal of Sociology, 92, pp.1170–1182.

- Borgatti, S.P. (2002) NetDraw Network Visualization, Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

- Borgatti, S.P., Everett, M.G., & Freeman, L.C. (2002) UCINET for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis, Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

- Brass, D.J. (1984) ‘Being in the right place: A structural analysis of individual influence in an organization’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 29(4), pp.518–39.

- Brunn, S. & Dodge, M. (2001) ‘Mapping the “worlds” of the World Wide Web’, American Behavioral Scientist, 44, pp. 1717–39.

- Castells, M. (1996) The Rise of the Network Society, New York: Blackwell.

- Castells, M. (2000) ‘Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society’, British Journal of Sociology, 51(1), pp.5–24.

- Castells, M. (2004) ‘Informationalism, networks, and the network society: A theoretical blueprint’, in M. Castells (ed) The network society: A cross-cultural perspective, Edward Elgar, Northampton, MA, pp.3–48.

- Castells, M. (2011) The Rise of the Network Society: The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture, Vol. 1, Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Chase-Dunn, C. & Grimes, P. (1995) ‘World systems analysis’, Annual Review of Sociology, 21, pp.387–417.

- Chen, E. & Stewart, J. (1999) ‘A framework for inter-domain route aggregation’, Work in Progress, 8, http://www.hjp.at/doc/rfc/rfc2519.html, accessed 27 August 2014.

- Chon, B.S., Choi, J.H., Barnett, G.A., Danowski, J.A., & Joo, S.J. (2003) ‘A structural analysis of media convergence: Cross-industry mergers and acquisitions in the information industries’, Journal of Media Economics, 16(3), pp.141–57.

- Consalvo, M. (2003) ‘Cyber-slaying media fans: Code, digital poaching, and corporate control of the Internet’, Journal of Communication Inquiry, 27(1), pp.67–86.

- Cooper, M. (2003) Media Ownership and Democracy in the Digital Information Age, Stanford, CA: Center for Internet & Society, Stanford Law School.

- Cukier, K.N. (1998) The Global Internet: A Primer. Telegeography 1999, Washington, DC: Telegeography, pp.112–145.

- Deibert, R. (2002) ‘Circuits of power: Security in the Internet environment’, in J.P. Singh & J. Rosenau (eds) Information, power, and globalization, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY, pp.115–42.

- van Dijk, J. (2006) The Network Society, 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Drake, W.J. (2000) ‘The rise and decline of the international telecommunications regime’, in C.T. Marsden (ed) Regulating the global information society, Routledge, New York, pp.124–77.

- Drake, W.J. (2005) Reforming Internet Governance: Perspectives from the Working Group on Intent Governance (WGIG), New York: United Nations.

- Emirbayer, M. (1997) ‘Manifesto for a relational sociology’, American Journal of Sociology, 102, pp.281–317.

- Emirbayer, M. & Goodwin, J. (1994) ‘Network analysis, culture, and the problem of agency’, American Journal of Sociology, 99, pp.1411–54.

- Eriksson, J. & Giacomello, G. (2009) ‘Who controls the Internet? Beyond the obstinacy or obsolescence of the State’, International Studies Review, 11, pp.205–230.

- Feamster, N. & Balakrishnan, H. (2003) ‘Towards a logic for wide-area Internet routing’, ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, 33(4), pp.289–300.

- Fraleigh, C., Moon, S., Lyles, B., Cotton, C., Khan, M., Moll, D., Rockell, R., Seely, T., & Diot, C. (2003) ‘Packet-level traffic measurements from the Sprint IP backbone’, IEEE Network, 17(6), pp.6–16.

- Franda, M.F. (2001) Governing the Internet: The emergence of an international regime. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner Publishers.

- Freeman, L.C. (1977) ‘A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness’, Sociometry, 40(1), pp.35–41.

- Freeman, L.C. (1979) ‘Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification’, Social Networks, 1(3), pp.215–39.

- Fuchs, C. (2009) ‘Information and communication technologies and society: A contribution to the critique of the political economy of the Internet’, European Journal of Communication, 24(1), pp.69–87.

- Giddens, A. (1990) The Consequences of Modernity, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gorman, S.P. & Malecki, E.J. (2000) ‘The networks of the Internet: An analysis of provider networks in the USA’, Telecommunications Policy, 24, pp.113–34.

- Huston, G. (1998) ISP Survivial Guide: Strategies for Running a Competitive ISP, New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Kegley, C.W. & Wittkopf, E.R. (2001) World Politics: Trends and Transformation, 8th ed. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's.

- Kim, J.H. & Barnett, G.A. (2007) ‘A structural analysis of international conflict: From a communication perspective’, International Interactions, 33, pp.135–65.

- Knoke, D. & Yang, S. (2008) Social Network Analysis, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Labovitz, C., Iekel-Johnson, S., McPherson, D., Oberheide, J., & Jahanian, F. (2010) ‘Internet inter-domain traffic’, ACM SIGCOM Computer Communication Review, 40(4), pp.75–86.

- Lee, S., Monge, P., Bar, F., & Matei, S.A. (2007) ‘The emergence of clusters in global telecommunications network’, Journal of Communication, 57, pp.415–34.

- Malecki, E. (2002) ‘The economic geography of the Internet's infrastructure’, Economic Geography, 78, pp.399–424.

- Marsden, C.T. (2000) Regulating the Global Information Society, New York: Routledge.

- McChesney, R.W. (2001) ‘Global media, neoliberalism, and imperialism’, Monthly Review New York, 52(10), pp.1–19.

- McChesney, R.W. (2004) The Problem of the Media: US Communication Politics in the Twenty-First Century, New York: NYU Press.

- Monge, P.R. & Contractor, N.S. (2003) Theories of Communication Networks, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mosco, V. (1996) The Political Economy of Communication: Rethinking and Renewal, Vol. 13, London: SAGE.

- Moss, M.L. & Townsend, A. (2000) ‘The Internet backbone and the American metropolis’, The Information Society, 16, pp.35–47.

- Muller, M. (2010) Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Norris, P. (2001) Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- O'Kelly, M.E. & Grubesic, T.H. (2002) ‘Backbone topology, access, an the commercial Internet, 1997-2000’, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 29(4), pp.533–52.

- Park, H.W., Barnett, G.A., & Chung, C.J. (2011) ‘Structural changes in the 2003–2009 global hyperlink network’, Global Networks, 11(4), pp.522–42.

- Park, H.W. & Thelwall, M. (2006) ‘Hyperlink analyses of the World Wide Web: A review’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 8(4), pp.522–44.

- Patelis, K. (2000) ‘The political economy of the Internet’, in J. Curran (ed) Media organizations in society, Hoder Arnold, London, pp.84–106.

- van Poucke, W. (1979) ‘Network constraints on social action: Preliminaries for a network theory’, Social Networks, 2, pp.181–90.

- Rogers, E.M. & Kincaid, D.L. (1981) Communication Networks: Toward a New Paradigm for Research, New York: The Free Press.

- Roycroft, T.R. & Anantho, S. (2003) ‘Internet subscription in Africa: Policy for a dual digital divide’, Telecommunications Policy, 27(1), pp.61–74.

- Sabidussi, G. (1966) ‘The centrality index of a graph’, Psychometrika, 31(4), pp.581–603.

- Samoriski, J.H. (2000) ‘Private spaces and public interests: Internet navigation, commercialism, and the fleecing of democracy’, Communication Law and Policy, 5, pp.93–113.

- Scholte, J.A. (2005) Globalization: A critical introduction, 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Seo, H. & Thorson, S.J. (2012) ‘Networks of networks: Changing patterns in country bandwidth and centrality in global information infrastructure, 2002-2010’, Journal of Communication, 62(6), pp.345–58.

- Serbedzija, N.B. (2013) ‘Service components and ensembles: Building blocks for Autonomous Systems’, International Conference on Autonomic and Autonomous Systems (ICAS), Lisbon, Portugal.

- Simmons, C. (2010) ‘Weaving a web within the Web: Corporate consolidation of the Web, 199–2008’, The Communication Review, 13, pp.105–19.

- Simpson, S. (2010) ‘Evolving global communications policy agendas and “North-South” relations: The Internet and telecommunications’, Communications, (Sankt Augustin), 37(2), pp.195–214.

- Singel, R. (2011, January 28) ‘Egypt shuts down its net with a series of phone calls’, Wired.com, http://wired.com/threatlevel/2011/01/egytp-isp-shutdown, accessed 16 September 2013.

- Skinner, D., Compton, J.R., & Gasher, M. (2005) ‘Mapping the threads’, in D. Skinner, J.R. Compton, & M. Gasher (eds) Converging media, diverging politics: A political economy of news media in the United States and Canada, Rowman & Littlefield, Lantham, MD, pp.7–23.

- Smith, D.A. & White, D.R. (1992) ‘Structure and dynamics of the global economy: Network analysis of international trade, 1965-1980’, Social Forces, 70(4), pp.857–93.

- Stewart, C., Gil-Egui, G., & Pileggi, M. (2004) ‘The city park as a public good reference for Internet policy-making’, Information, Communication, and Society, 7(3), pp.337–67.

- Stewart, J. (1999) BGP4: Inter-domain Routing in the Internet, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Sun, S.L. & Barnett, G.A. (1994) ‘The international telephone network and democratization’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 45(6), pp.411–21.

- Telegeography. (2014) ‘Level 3 to acquire tw telecom for USD7.3bn’, Telegeography News Feed, http://www.telegeography.com/products/commsupdate/articles/2014/06/17/level-3-to-acquire-tw-telecom-for-usd7-3bn/, accessed 19 June 19 2014.

- Telegeography. (2013) ‘Europe emerges as global Internet Hub’, Telegeography News Feed, http://www.telegeography.com/press/marketing-emails/2013/09/18/europe-emerges-as-global-internet-hub/index.html, accessed 18 September 2013.

- Telegeography. (2011) Global Internet Geography, www.telegeography.com.

- Wallerstein, I. (1974) The Modern World System, New York: Academic Press.

- Warf, B. (2003) ‘Mergers and acquisitions in the telecommunications industry’, Growth and Change, 34(4), pp.321–44.

- Wasserman, S. & Faust, K. (1994) Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications, New York: Cambridge University Press.