ABSTRACT

This article posits an expanded conceptualisation of disaster communities. It extends previous research on disaster and media ecology by reflecting broader understandings of disaster but articulates a new analytical framework that recognises both their global dimensions and local contexts. When theorising disaster communities, we present a framework that unpacks the social, institutional and mediated points of connection that are characteristic of these communities and their communicative dynamics. These ties, we argue, are not defined solely by a shared geography but instead expand beyond this through the emergence of spontaneous connections that often emerge in response to disasters and their drivers. Moreover, these connections may also demonstrate a greater degree of permanency, provide boundary definitions and strengthen identity for these communities. Importantly, we recognise how media and journalism can create both new interrelations and consolidate existing points of connection for disaster communities and elaborate on the dynamics and composition of these mediated ties. The article closes by presenting avenues for future research to explore points of connection for disaster communities, in particular those established and consolidated by media, and the contribution of community approaches within the context of the globalised nature of disaster and their drivers.

It is widely recognised that disasters are becoming more frequent, having greater and longer-lasting impacts, and are increasingly affecting those most vulnerable (Watson et al. Citation2015). In parallel, there has been a shift toward defining and understanding disasters in broader terms, as dynamic processes encompassing the breadth of hazards and vulnerabilities that contribute to human insecurity. Some argue, therefore, that disasters are more accurately conceptualised as complex, systemic failures (Cottle Citation2014; Helbing Citation2013). Recent research in media has generally followed this theoretical direction, evaluating the processes of mediation at a national and international level that circulate around disaster and their drivers (see Cottle Citation2014; Pantti, Wahl-Jorgensen, and Cottle Citation2012).

This paper offers a complementary approach. It extends the concept of disaster communities,Footnote1 which has previously centred on group formation processes and responses to disaster (Tekin and Drury Citation2021; Wright et al. Citation1990), by outlining the social, institutional and mediated points of connection for these communities in the context of the globalised nature of disaster and their drivers. In doing so, we argue that a disaster community is not defined solely by a shared geography, and the vulnerabilities and risks that this may present for such a community, but may expand beyond this through the extension of existing ties and emergence of spontaneous connections that develop in response to disasters and their drivers.

The discussion explores how the dynamics and composition of disaster communities are shaped not only by social and institutional ties but also by the epistemology of mediated interrelations. We therefore consider the potential for media and journalism to create new and sustain existing points of connection. This is within the context of the global flows of information and communication (macro level), ties that emerge and are sustained by organisations, such as national and local news media (meso level), but also derived from interpersonal interactions facilitated by digital media (micro level). We elaborate on the role of media and journalism produced by and for disaster communities. How local media or grassroot initiatives, for example, can enhance community identity, increase awareness of disaster vulnerabilities, and contribute to rebuilding community ties and social relations post-disaster (Kanayama Citation2007; Matthews Citation2017; Sreedharan, Thorsen and Sharma Citation2019; Usher Citation2009). In this way, local news providers and other forms of community media are integral to risk reduction, shared memory and recovery processes for disaster communities and can often challenge the spontaneous and transient attention from outsider media. We also recognise how social media can foster direct connections between those directly affected by disaster and distant others, expanding the boundaries and geographic reach of a disaster community.

We posit that these social, institutional and mediated ties characteristic of disaster communities, have a greater degree of permanency, and provide boundary definitions and identity for such networks. This is because these ties are often consolidating pre-existing connections and emerge from a shared experience or purpose (Drury et al. Citation2019; Wright et al. Citation1990).

The paper begins by exploring contemporary theorisations of disasters to illustrate the need to reflect a broader understanding of disaster, with disasters attributed to a range of complex hazards, risks and vulnerabilities, and understood as a process that unfolds and develops over time. In the disaster management literature, this is typically described as a cycle with defined phases (e.g., mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery). In reality, as is often recognised, it is a multifaceted process with overlapping and interlocking drivers. In light of this complexity, we critique the concept of disaster communities, before outlining an expanded theoretical framework that considers their composition and communicative dynamics, in particular reflecting on the potential for media and journalism to create and sustain points of connection for these communities. Finally, it closes by outlining avenues for future research to explore the characteristics and points of connection for disaster communities, recognising their intersection with different media forms and the contribution of community approaches in mitigating disaster vulnerabilities.

Disasters and their drivers

Disasters are very rarely solely the result of sudden-onset events. Instead, their causes are complex, deep-seated and intersect with other vulnerabilities that create insecurity (Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction Citation2015). Many, therefore, describe disasters as a process, which progress through different phases (Albris Citation2022). While there is a diversity of research across different disciplines, academic enquiry has tended to focus on disaster events and their acute impacts. Studies of media and journalism have generally followed this pattern, with greater scholarly attention paid to media treatment and communication processes that follow significant disruptive events (Ploughman Citation1995; Veil Citation2012). A much smaller body of research has examined their role in enabling communities to identify and address the antecedent conditions that lead to disaster and their contribution to recovery processes.

It is the emphasis on ‘extreme events’ that result in significant loss of life and then become known and made visible through international media coverage (Cottle Citation2014), which has limited the scope of disaster research. Some scholars, therefore, identify a need for greater theoretical diversity in this body of research and for disaster studies to link to the related fields of sociology of risk and environmental sociology as well as to consider the key sociological concerns of inequality, diversity and social change (Tierney Citation2007).

As indicated, a consensus has emerged in recent years that the frequency, impact and scale of disasters are increasing. The climate crisis is fuelling more powerful storms and prolonging periods of drought. Environmental degradation and the destruction of ecosystems, such as floodplains and forests, remove natural barriers that protect communities. Urbanisation is increasing the number of people exposed to natural hazards (Global Facility for Disaster Risk Reduction Citation2016). Such hazards in the context of other conditions and vulnerabilities that create or contribute to human insecurity, the most significant drivers being persistent poverty, food insecurity, forced migration, conflict and violations or political and human rights, have reconfigured understandings of disaster, their causes and impacts. This has been reflected in both policy and practice, with a subtle shift from disaster management toward risk reduction and a recognition of the need to address the intrinsic and dynamic processes that contribute to disaster. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (Citation2015, 10), specifically calls for action to address ‘underlying disaster risk drivers’, and highlights the impacts of persistent poverty and inequality, climate change, urbanisation, alongside the ‘compounding factors’ of demographic change, weak institutional arrangements, declining ecosystems and pandemic risks.

These broader, multi-layered approaches to defining disaster and their drivers have led to contemporary theorisations moving away from low probability yet high-impact processes to acknowledge the accumulation and intersection of hazards, risks and vulnerabilities.

The concept of cascading disasters considers the interactions between compounding vulnerabilities and different events (Pescaroli et al. Citation2018). Disasters that cascade are initiated by a trigger event, either natural or anthropogenic, that intersects with other hazards to amplify their impacts or create new or aggravate existing vulnerabilities (Pescaroli and Alexander Citation2015). Many of these susceptibilities arise from the increasing interdependence between systems, such as the interactions between climatic, food and energy systems for example (Helbing Citation2013). It is increasing complexity, therefore, and these interconnecting processes that result in adverse outcomes for communities.

Significantly, Pescaroli and Alexander (Citation2015) explain that a cascading disaster is not simply a causative sequence of events but can be more accurately defined as a non-linear process that is context-dependent. By way of an example, a flood itself may result in loss of life, but the impacts of flooding on a community that relies on subsistence farming and with weak infrastructure would be magnified due to a lack of economic and structural resilience. This amplification can then lead to further adverse consequences, such as triggering population movements or exacerbating intergroup tensions.

In a similar vein, Quarantelli (Citation2006, 9) describes newly emerging disasters that ‘cut across social systems’ as trans-social-system ruptures. These ruptures are a consequence of globalisation processes and their effects are geographically dispersed. They are the major global crises that have widespread repercussions and require transnational solutions. Cottle suggests (Citation2014, 4) that these types of disaster are not ‘territorially defined’ and are ‘endemic to, deeply enmeshed within and potentially encompassing in today’s world disorder’.

Other theorisations emphasise a more expansive paradigm, suggesting that crises, as the ‘exogenous and endogenous factors’ that create disruption, are a more appropriate focus for research enquiry (Boin Citation2005, 165). This perspective presents a broader typology of disaster drivers to encourage interdisciplinary and multilevel approaches to analyse the causes of complex crises. It also recognises that adverse outcomes may return or create further unintended consequences even when a crisis has supposedly been resolved.

Despite these evolving understandings and the characteristics they share, both disasters and crises are social constructions. What is defined or labelled as such reflects values, interests and encourages specific forms of intervention. Many disasters that have adverse impacts on communities fail to register in international media coverage. News values, the proximity and relevance of emergencies to audiences and their potential to dislocate the interests of elite nations render some ‘disasters’ and emerging crises invisible (Galtung and Ruge Citation1965; Joye Citation2010). Social construction processes are also shaped by media treatment of events and how risks and vulnerabilities are communicated. Tierney (Citation2007, 62) notes that when covering disasters media ‘both reflect and reinforce broader societal and cultural trends, socially constructed metanarratives, and hegemonic discourse practices that support the status quo and the interests of elites’. This, she argues, was evident in the way US media constructed post-Katrina New Orleans as lawless and violent, which drew upon stereotypical portrayals of America’s impoverished communities and reflected longstanding political discourses and policy positions that sought a greater role for the military in disaster management.

Even if we accept a more limited definition of disaster as the sudden disruptive events, by adopting this term to also describe chronic vulnerabilities and the drivers for disaster calls attention to problems that may not be recognised or sufficiently understood. Consequently, identifying a hazard risk or vulnerability, or their potential to emerge, and their intersection with others as disasters, may encourage greater awareness, response and forms of actions that seek to alleviate these drivers of adverse impacts for communities.

Our theorisation of disaster communities acknowledges that disasters should be understood as processes and redefined to reflect the accumulation and intersection of hazards, risks and vulnerabilities that lead to adverse outcomes. Within the context of the ‘globalising forces’ that shape these threats (Cottle Citation2014, 10), our approach to disaster communities seeks to offer a complementary, bottom-up perspective, by orienting our focus toward and from the communities affected by disaster and exploring the points of connection that emerge in response to disaster and their drivers. For research in media and communication, it therefore aims to provide a bridge between macro and micro-level analyses by considering media produced by and for these disaster communities within the global flows of exchange and communication (Heilbron, Boncourt, and Sorá Citation2018).

Importantly, as we elaborate on further below, our framework seeks to emphasise community perspectives toward disaster. Ultimately, the definition of disaster, their drivers and adverse impacts, ontologically, are located in the different notions of community and how these communities may view, experience and understand disaster and their effects. It is to these features that the discussion now turns, to elucidate our theorisation of disaster communities, before outlining their dynamics and different points of connection.

Critiquing disaster communities

Community is a broad concept that is used to describe groups of people with social connections and /or shared commonality. These networks, for example, are often premised on shared identity, religion and customs or values, and which may correspond with a defined geographical locality and sense of belonging. Geographic specificity contributes to the boundary definition of communities, through shared places such as towns and neighbourhoods, though community can also be used in connection with the expression of national or international identities. As such, communities vary significantly in scale - both in terms of their population and their physical distribution.

Globalisation has contributed to a shift in how we view communities, away from the need for physical colocation to establish ties amongst those that are geographically dispersed, such as the formation of diasporic, digital and online communities (Rheingold Citation2000). Physicality is also not necessarily fixed, with nomadic communities exercising mobility as part of their core identity. Refugees or migrant communities, for example, may express a sense of belonging to both their place of origin and each other. Affiliation and connectedness to others can form through groups on social media and in other online spaces (Lingel and Naaman Citation2012).

The purpose of community is often seen as a way of uniting groups of people, and that such unity reduces suffering through solidarity, collective endeavour and shared purpose. Members of communities strive for shared emotional wellbeing (Davidson and Cotler Citation1989; MacMillan and Chavis Citation1986). Yet, disasters pose a threat to or disrupt the fabric of communities, regardless of their size, and necessitate a response from its members to protect, address vulnerabilities and restore normalcy of its existence. Irrespective of their causes, disasters, Bruhn (Citation2011, 112) argues, ‘have common effects – they produce trauma that changes the social and emotional lives of the individuals, the resiliency of families, and the cultural fabric of families’. In so doing, this may serve to extend or strengthen community ties or lead to the formation of new communities. For instance, groups that may form around specific interest concerns, as survivors, the displaced or those that organise and contribute to disaster response and recovery efforts. Kaniasty and Norris (Citation2004, 202) describe these mobilisations as altruistic communities, where victims and survivors come together as previous barriers ‘temporarily fade away’.

While we would always emphasise that communities that are directly at risk from or affected by disaster should remain our principal concern, due to their acute effects often being experienced by communities bound by a shared geography and environment. Limiting disaster communities to a place-bound definition, areas that are vulnerable to disaster drivers, physically damaged or disrupted by disaster and their impacts, fails to acknowledge how those affected by and at risk expand beyond this. A refugee community, for example, is nationally and culturally diverse, but in facing hardship and the trauma of fleeing conflict and persecution individuals will have common needs and experiences (Jack Citation2020). As a displaced community, refugees obtain temporary shelter but may continue to move, often across borders, to seek security and stability, until they reach a destination of some permanency.

There will also be communities that experience adverse impacts, yet in different ways and extents. This may include family or friends that live in other locations, those that may be indirectly affected but experience increased anxiety as a consequence of perceived risk or others that have fostered connections to those directly at risk from or affected by disaster. Here, we concur with previous work that asserts that a disaster community has ‘a specific geographic disaster epicentre but is perceived and experienced through a complex web of social networks’ (Kirschenbaum Citation2004, 98). Moreover, that ‘the foundation of a disaster community depends on a core of social networks connecting those directly or indirectly affected by a disaster’ (Kirschenbaum Citation2004). Thinking of disaster communities in this way acknowledges that there are a number of ‘social networks operating simultaneously from the epicentre of a potential (or actual) disaster area’ (Kirschenbaum Citation2004, 100). Components of a disaster community according to Kirschenbaum can include family network, micro-neighbourhood network and macro-community network. Whilst these provide focal points for understanding levels of preparedness, they do not consider institutional ties, professional networks beyond emergency services or those facilitated by organisational membership, nor the role of mediated connections. This is where our theorisation departs from previous understandings of disaster community. Local or community media, for example, are integral to developing community identity that raises awareness of disaster drivers and are also able to contribute to the rebuilding of community ties and social relations post-disaster. Digital media facilitates connections amongst dispersed others, without the need for physical colocation. Therefore, we argue for a more expansive definition of disaster communities to recognise these communicative dynamics and that the composition of disaster communities cannot be understood in isolation from the epistemology of mediated interrelations.

In our theorisation of disaster communities, we place particular emphasis on local media and journalism, which as part of the social and civic fabric of their communities can provide information that raises awareness of disaster drivers and support communities to mitigate risks (Blanchard-Boehm Citation1998). When critical infrastructures are destroyed or disrupted, as may follow a significant natural hazard event, local media may be better positioned to meet communities’ information needs, by providing access to vital emergency information (Kanayama Citation2007). While local and community media may also be directly impacted during a disaster or ill prepared to report on the complexities of disaster, evidence shows that following a loss of power and without access to digital networks, community radio, for example, can be a valuable conduit for critical information (Reilly and Atanasova Citation2016), in particular to provide health-related information, advice and psychosocial support to communities (Hugelius, Adams, and Romo-Murphy Citation2019). Later, beyond the immediate impacts of disaster, local media and journalism may be able to support communities as they seek to adapt to and recover from their effects, advocating on behalf of communities and promoting wider awareness of the continuing challenges and issues of post-disaster recovery (Matthews 2017; Usher Citation2009). This is reflected in the close working relationships humanitarian agencies and charities seek to develop with local media, where there is a recognition of the importance of capacity-building to support local media in communities at risk or recovering from disaster.

It is also necessary to recognise how the contemporary digital media environment enhances the breadth of information, media and journalism available to disaster communities and facilitates their participation in community-based risk reduction and disaster response. Online citizen journalism projects, for example, provide a platform to raise concerns and engage in civic activities (Thorsen, Jackson and Luce Citation2015). The aggregation of social media data is now integral to disaster management, used to warn people about hazards and support emergency response (Crowe Citation2012). It has also transformed the way organisations communicate during and in response to disaster, with social media, for example, providing channels that enable organisational and inter-organisational communication for agencies responding to disaster (Liu, Xu, and John Citation2021). Digital media can also provide eyewitness perspectives, enable the dissemination of critical information, enhance situational awareness and facilitate communication and collaboration, overcoming limitations that may exist within existing top-down models of disaster communication (Tim et al. Citation2017). Online and social platforms also enable forms of hyperlocal journalism, which may initially cater for a small defined community but can bypass traditional gatekeepers and raise awareness of disaster drivers that may have not yet come to the attention of mainstream media. Prior to the devastating fire at Grenfell Tower, West London, in 2017, a residents’ action group made known their concerns about the refurbishment work and fire safety in the tower block through their own blog, warnings that it has been argued were missed by other news outlets (Barling Citation2020). After the earthquake that destroyed the Italian city of L’Aquila in Italy in 2009, a group of citizen journalists from the city felt compelled to record their experiences and share it with their community to highlight the situation and to be able to ‘reconnect their social ties’ (Farinosi and Treré Citation2014, 85). Digital media are also altering the dynamics of humanitarian communications, allowing direct connections between affected communities and humanitarian agencies and facilitating the emergence of networks of digital volunteers that are able to support emergency response and assist in rescue and relief efforts (Chernobrov Citation2018).

Therefore, by defining disaster communities in a more expansive way and recognising the different points of connection that are created and sustained by such communities, it seeks to provide greater analytical precision to the social and communicative dynamics that emerge across the different phases of disaster. Our theorisation specifically draws attention to an often neglected area of research - the role of media, specifically the connections created and sustained by local and community media in the context of the globalised nature of disasters and their drivers. This serves as a bridge between media research that has largely considered the processes of mediation at a national and international level, sociological research that has focused more on social ties than those attributed to mediation, and disaster management research that has emphasised risk reduction, information provision and organisational communication channels in response to emergencies.

A theoretical framework for disaster communities

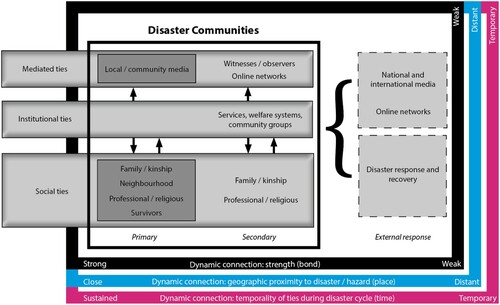

In we set out our theoretical framework for disaster communities, illustrating their different points of connection, their dynamics and communication flows. We separate these into primary and secondary social ties, institutional ties, and primary and secondary mediated ties, with examples offered for each. The framework also indicates the strength of these ties and the intervening variables of (geographic) proximity and temporality.

The strongest ties for disaster communities are those that sit in the lower-left hand corner of the figure. These are primary social ties, connections that are formed between those that share a proximity to a hazard or disaster, and are sustained, ties that have formed prior to and continue beyond the disaster cycle. Weaker ties are those reflected in the top-right of the figure. These are secondary ties, connections that form amongst those that are distant from a hazard or disaster, and may only be brief or temporary, for example forming and existing during particular phases of the disaster cycle.

Social ties

In our framework, social ties are the interpersonal connections that people form through their interactions and shared experiences with others. It recognises, as with previous work, that for disaster communities place shapes social relations but also their vulnerability to disaster and their impacts (Drury et al. Citation2019). Therefore, we include neighbourhood as a primary social tie since locality facilitates interactions between community members but also the distribution of risks and impacts of disaster shared by individuals. Proximity heightens the risks from natural hazards, for example, and the extent and magnitude of their impacts. Our framework departs from other approaches by showing family and kinship ties as both primary and secondary ties for a disaster community since family groups that live near a hazard or risk will be more likely to experience their direct effects and consequently form stronger ties to those that remain distant.

We also recognise how place-bound connections can expand, contract and shift dynamically across domains and thus create new social ties for disaster communities. This geographic mobility is most clearly illustrated by humanitarian crises, where people have fled from violence, conflict and persecution. As a disaster community, forcibly displaced people will move from one location to another and transit through others as they seek safety and security. Through their journey, shared experiences and hardships they often face, individuals can form new bonds and connections. While these may be fragile and transient interconnections for some (secondary ties), which fade over time as they reach their destinations, others may build stronger and enduring connections (primary ties). Equally, new social ties may be established through temporary settlement or later as refugees integrate into ‘destination communities’ (Morales Citation2018). This is just one example of the overlapping or multiple networks that are illustrative of disaster communities.

In a similar way we acknowledge that survivors of disaster, through their shared trauma and experience, may establish new connections with others, and as such are also examples of primary ties within a disaster community. Collective trauma creates new bonds and connections as people seek to recover (Wright et al. Citation1990). A report that considers the impacts on the health and wellbeing of those affected by the Grenfell fire identified, for example, how people established new connections through activities that took place after the disaster (Strelitz et al. Citation2018). Moreover, shared grief and the ongoing processes of memorialisation can also bring survivors together, fostering strong and enduring connections. For disaster communities these collective emotional experiences nurture resilience and contribute to community-led recovery (McEwen et al. Citation2017; Montelli, Barclay, and Hicks Citation2020). This is illustrated by the dual trauma that local journalists may face in disaster situations, where they must deal with the personal impacts of a disaster, as survivors, but also the secondary trauma that may follow from their professional work and the need to report on the impacts and suffering caused by disaster (Sreedharan and Thorsen Citation2020).

We also acknowledge how professional and religious networks can serve as both primary and secondary ties for disaster communities. While professional networks may form first as interest-based groups, stronger primary ties can also emerge over time. As for the other social ties described above, the colocation of organisations and workplaces mean that proximity to disaster vulnerabilities and their impacts, for example, if a workplace and employees are directly impacted by a disaster, can facilitate or strengthen connections amongst those at risk from or affected by disaster.

Institutional ties

Institutional ties are shaped by the breadth of institutions and organisations embedded within communities. While informal institutions, the conventions and customs that govern how people interact, are significant in determining how communities organise and respond to disaster, for example, the types of behaviours that may emerge post-disaster (Rodríguez, Trainor, and Quarantelli Citation2006), the emphasis for our framework is upon formal institutions and organisations. Since organised social activity promotes and maintains social capital (Bourdieu Citation1986; Putnam Citation2000), these institutions we posit will correlate with the strength of ties for disaster communities. Strong institutions can foster social networks and create connections for communities. Employment, voluntary and civic organisations establish formal relationships, and similarly to the professional or interest-based networks introduced above, over time can foster closer primary social ties. In addition, as others argue, following disaster, social capital can promote disaster recovery by enabling communities to mobilise and coordinate relief efforts (Aldrich Citation2012).

The strength, governance and capacity of institutions can also assist communities to reduce disaster risk and respond to adverse outcomes. For communities that face complex hazards, risks and vulnerabilities, an absence of institutions, for instance, weak governance, poor health and welfare infrastructures, will perpetuate inequalities that can lead to adverse outcomes (Ahrens and Rudolph Citation2006).

The interactions within and between institutions and organisations will also evolve in response to disaster and their drivers. Inter-organisational networks will form to mitigate risks, respond to and in the recovery from disaster. This may include collaboration between national and local government agencies and non-profit organisations to address disasters and perceived risks. As an example, the UK has a decentralised approach to disaster management. The first stage involves local agency response but with significant disasters they are coordinated by central government, through its civil contingencies committee or COBR as it is commonly known. This involves representatives from government department(s), institutions such as the police and organisations with relevant scientific and technical expertise (Kapucu Citation2009). These interactions, in particular those that engage local stakeholders or require a wider response, involve coordination and closer working between relevant organisations and institutions.

Mediated ties

In our expanded conceptualisation of disaster communities, we also introduce primary and secondary mediated ties. Primary mediated ties, as outlined above and demonstrated through the existing scholarship, are fostered by community media due to their position, interactions with and relevance to their audiences (Reader Citation2012). Such media are nominally accountable to the community (Stamm and Weis Citation1986) and contribute to the development of social capital. A vibrant local and community media, which spans legacy and digital media, therefore, can serve as conduits for establishing and consolidating primary ties for communities that are vulnerable to disaster and their drivers.

Local and community media may help to cultivate ties through the direct interactions between those that produce media content and their audiences. Journalists that work for a local newspaper, for example, are often connected to and interact with the community that they cover. This interactivity, whether it is in the course of their news work or through informal interactions, facilitates exchange amongst community members and belonging to the community (Ball-Rokeach, Kim, and Matei Citation2001; Wenzel, Ford, and Nechushtai Citation2020). This suggests, as recent research on the impacts of COVID-19 on journalism in Sierra Leone shows (Sreedharan et al. Citation2021), when communities face disaster, these journalists can experience personal trauma and difficulties as they attempt to fulfil their professional roles (Matthews Citation2017 Sreedharan and Thorsen Citation2020). Citizen-led, hyperlocal media initiatives, which can provide a platform for communication and interaction, are also able to foster direct connections and build communities through these online spaces (Speakman Citation2019).

Mediated ties recognise that media outlets that cater for a distinct community can foster ties and a sense of community for their audience. They may, through the news and information that they provide, enable people to recognise commonalities with others, stay informed about their community and facilitate interaction (Rothenbuhler Citation1991; Speakman Citation2019). For disaster communities, and their shared vulnerabilities and experiences, local and community media can facilitate the development of ties that may increase awareness of disaster risks, efforts to mitigate their impacts and contribute to the rebuilding of community post-disaster. They can also act as a conduit to provide contextual information by relaying local and community perspectives to national or international media, either by acting as stringers or due to their presence and access to the site of disaster vulnerabilities and their impacts. It is also necessary to recognise that the resilience of local and community media, due to their smaller operations and lack of disaster preparedness, can limit their ability to respond, as recent studies from Nepal and Sierra Leone show.

As with the other ties, proximity and temporality serve as intervening variables, which influence the strength of these mediated ties. By way of an example, in contrast to a regional or metropolitan news outlets, a community radio station or newspaper can create and sustain closer primary ties due to the overlapping social and institutional ties that coexist for those living in a smaller geographic area and the shared vulnerabilities that may be reflected through their output. This is illustrated by the role that community radio played in supporting social mobilisation efforts in Sierra Leone for communities affected by the 2014–16 Ebola outbreak (Bedson et al. Citation2020). A rapid expansion of these mediated ties that emerge across and between networks in the acute phase of disaster, such as in responding to a public health emergency, will often be followed by a similarly brisk retraction and realignment of these network relations as the immediate risks fade over time.

In response to disaster and their drivers, organisations will have a key role in communicating and disseminating information. It is also necessary, therefore, to recognise how mediated ties are reflected in organisational communication networks, with social media enabling interactions at both the micro and meso level. This is reflected in the way community members provide information to organisations, through social media, but also facilitate interpersonal interactions (Spialek, Houston, and Worley Citation2019). Digital and social media can also ease the flow of information within organisations, which can be of vital importance during critical phases of disaster mitigation and response and for emergency management practice (Haupt Citation2021). These are further examples of mediated ties that can emerge within specific institutional or organisational contexts.

Secondary mediated ties are weaker and reflect those connections that form and extend in online spaces and through digital media, where a community may be geographically distant from disaster vulnerabilities and their impacts. These mediated ties may result from initiatives to engage diasporic or transnational communities in advocacy or action to support risk reduction or relief efforts (Esnard and Sapat Citation2016). Mediated ties that enable a disaster community to reach beyond those directly affected also recognise the breadth of content that can be provided for interest groups, such as curating information about reconstruction after disaster for particular linguistic groups and seeking to reach global audiences.

Further secondary mediated ties are those that emerge as people observe or witness disaster yet are distant from their direct risks and impacts. The mediation of large-scale acute disasters shapes how these events are experienced by individuals. Some suggest that the processes of mediation, when audiences bear witness to the suffering caused by disaster and their drivers, can lead to forms of collective response and action (Chouliaraki Citation2008; Zelizer and Tenenboim-Weinblatt Citation2014). As ‘mediated witnesses’, experiencing a disaster indirectly yet through the media creates connections with victims and affected others; for example, as people try to make sense of events and through the wider social commentary that may follow (Peelo Citation2006). These are of course weaker and temporary connections, facilitated by media representations of significant events. Such events are often acute disruptions that attract widespread attention from the media but may also include persistent and chronic vulnerabilities when they reach the emergency thresholds that generate media coverage. The representational processes enacted when reporting on famine, humanitarian crisis and persistent conflicts, for example, can lead to affective responses amongst audiences as they bear witness to those experiencing suffering and hardship. The ties that they create or sustain can also be reignited through the memorialisation of past events or the collective trauma of disaster.

External response

When proposing a framework to theorise disaster communities, it is also necessary to recognise how the external response to disaster and their drivers can help to solidify the sense of community and its boundaries. It also acknowledges how other types of spontaneous connections may arise in response to disasters, for example, through the activities of NGO, IGOs and through the coverage by national and international news media. These can also create new ties for disaster communities and strengthen existing points of connection.

The dynamics of external response, and its influence on disaster communities and these connections, shift as a disaster moves through the disaster cycle, from mitigation, preparedness, response and then into the recovery phase. To address the drivers of disaster outlined above, NGOs will implement programmes that require external expertise, capacity and resources. While local-capacity building and partnerships are necessary to ensure long-term sustainability and resilience for communities, some aid workers are transient, moving to a locality to support risk reduction or disaster response efforts. They may, therefore, become part of this community for only a short period of time or during specific phases of the disaster cycle. This illustrates how the variables of temporality and proximity can intersect with the external response to disaster, influencing the composition of a disaster community. During critical periods of disaster risks and their impacts, when disaster relief and crisis interventions are enacted by external agencies, these actors may create strong primary ties as they become part of the locality that face these challenges. At other phases of the disaster cycle, where the needs may no longer be acute, such actors will move away, and respectively ties will weaken and retract. In contrast, chronic vulnerabilities that persist may lead to different degrees of permanency, with longer-lasting interventions necessitating that such actors become integrated into disaster communities.

In a similar way, national and international media, may also represent another external influence upon these communities, with journalists from outside and without the local knowledge parachuted in to report on events. This is a common feature of mainstream news coverage of disaster, which may contribute to a distorted picture of affected communities by lacking context and failing to integrate local perspectives.

Since media facilitate the distribution and exchange of communication then how national and international media construct issues and events also has the potential to reflect back on and have consequences for disaster communities. Disasters can become focusing events that precipitate shifts in political agendas and policy (Birkland Citation1997). Issues raised by national or international media about the efficacy of disaster planning to reduce disaster risks, for example, can influence forms of advocacy or action within a disaster community.

Future research questions and conclusions

To expand our theoretical framework of disaster communities we encourage further research, both empirical and theoretical, to explore the characteristics, points of connection for disaster communities, and their intersection with different media forms.

While this article has evaluated the existing scholarship, it is necessary to extend our understanding of the breadth of media and journalism that is produced by and for communities at risk from, affected by and recovering from disaster. To this end we suggest there is a need for research to reflect the diversity of local, grassroots and community media which exist in the contemporary global media landscape and to understand their relationships with different disaster communities. As elaborated on above there exists a body of work that has established the significance of traditional media, specifically radio and newspapers, to disaster communities. Yet, more research is needed to understand how digital media, which enable individuals or interest groups to produce and distribute their own content, create and enhance participation in alternative forms of media and journalism that cater for disaster communities. This includes recognising the increasing importance of hyperlocal media that exists online or across social networks and how they can provide information and facilitate connections for a disaster community. It is also necessary to look beyond significant disruptive events, and for empirical research to recognise the accumulation of vulnerabilities that represent disaster processes. This will encompass perspectives from those communities that experience ongoing or recurrent disasters, those that are a consequence of persistent conflict, structural economic and social inequality, environmental degradation or forced migration and displacement for example.

Another key question that follows, and is central to our theorisation of disaster communities, is the extent to which the different forms of media reflect and extend our understanding of community that emerge in disaster contexts. It is necessary to consider further, for example, how media foster, enrich and reflect the mediated ties that are outlined in our framework. Yet, to also recognise those that may consolidate or create ties, which may be geographically dispersed and distant from the drivers of disaster and their effects, but still significant to those that form this community. To further understand the strength and interaction between the different social, institutional and mediated points of connections for disaster communities, we are calling for more empirically based research and analysis. It is also important to consider where local and community media may have played a more limited role and to understand the opportunities to enhance their role in risk reduction and disaster response. This may mean mapping the dynamics of recent disasters to our framework to identify opportunities to enhance capacity-building, provide training and improve journalism resilience, for example.

Our knowledge about how different media are received and acted upon by disaster communities is also limited, often focusing on disasters and their drivers that reflect a Western bias in their impacts. This is illustrated by the significant body of work that explored how European audiences responded to the South Asian tsunami of 2004 (See Kivikuru Citation2006), which was a consequence of the number of European tourists that were affected by this disaster. Moreover, we also know more about how information is disseminated and used during disaster, in particular during the immediate response phase, and to a lesser extent the effectiveness of different messages and tools in risk reduction and disaster management. However, less is known, about how communities may interpret, deconstruct and act upon messages across the lifecycle of disaster and in particular during the recovery phase.

If we accept the view that disaster communities emphasise a definition of community that is broader than those approaches premised on a distinct geography, then these different communities and their points of connection that coexist in these contexts may ascribe different meanings and interpretations to media and the messages they convey. For example, communities that are dependent on radio for critical safety and lifeline information after disaster will have a different relationship and needs to a transient community of aid workers that are supporting disaster relief efforts.

Arguably, the most important consideration for further research is the extent to which a community-oriented approach, alongside the complex and globalised dynamics of contemporary disasters, may help to identify and address the breadth of hazards, risks and drivers of disaster vulnerabilities. Identifying different communities, their points of connection and responsibilities are, for example, necessary to enable effective disaster communication to mitigate, prevent and reduce the impacts of disaster.

In this article, we have argued that by defining disaster communities in a more expansive way and recognising the different points of connections for communities, it provides greater analytical precision to both the social interconnections and communicative dynamics that emerge across the different phases of disaster. In doing so we have attempted to outline the utility of disaster communities as a theoretical framework for future research and to encourage further studies to elaborate on their key features presented in this article. Crucially, while we view our approach as complementary to the significant body of work on media and disaster, we seek to encourage future research to step beyond national and international news media and to recognise the valuable contribution, and their present limitations, of media produced by and for disaster communities within the context of the globalised nature of disaster processes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jamie Matthews

Jamie Matthews is Principal Academic in Communication and Media at Bournemouth University, United Kingdom. His research interests lie at the intersection of international communication, journalism studies and risk perception.

Einar Thorsen

Einar Thorsen is Professor of Journalism and Communication and Executive Dean of the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University, United Kingdom. His research covers journalism and social change, citizens’ voices, news reporting of crisis and politics.

Notes

1 This article builds on a concept we originally developed in Media, Journalism and Disaster Communities (Matthews and Thorsen Citation2020).

References

- Ahrens, J., and P. M. Rudolph. 2006. “The Importance of Governance in Risk Reduction and Disaster Management.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 14 (4): 207–220.

- Albris, K. 2022. “Disaster Anthropology: Vulnerability, Processes and Meaning.” In Defining Disaster, edited by M. Aronsson-Storrier and R. Dahlberg, 30–44. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Aldrich, D. P. 2012. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Barling, K. 2020. “Is Local Journalism Failing? Local Voices in the Aftermath of the Grenfell and Lakanal fire disasters.” In Media, Journalism and Disaster Communities, edited by J. Matthews and E. Thorsen, 165–177. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ball-Rokeach, S. J., Y. C. Kim, and S. Matei. 2001. “Storytelling Neighbourhood: Paths to Belonging in Diverse Urban Environments.” Communication Research 28 (4): 392–428.

- Bedson, J., M. F. Jalloh, D. Pedi, S. Bah, K. Owen, A. Oniba, M. Sangarie, et al. 2020. “Community Engagement in Outbreak Response: Lessons from the 2014–2016 Ebola Outbreak in Sierra Leone.” BMJ Global Health 5 (8): e002145.

- Birkland, T. A. 1997. After Disaster: Agenda Setting, Public Policy, and Focusing Events. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Blanchard-Boehm, D. R. 1998. “Understanding Public Response to Increased Risk from Natural Hazards: Application of the Hazards Risk Communication Framework.” International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 16 (3): 247–278.

- Boin, A. 2005. “From Crisis to Disaster: Towards an Integrative Perspective.” In What is a Disaster? New Answers to Old Questions, edited by R. W. Perry and E. L. Quarantelli, 153–172. New York, NY: International Research Committee on Disasters.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” Cultural Theory: An Anthology 2011 (1): 81–93.

- Bruhn, J. G. 2011. The Sociology of Community Connections. London: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Chernobrov, D. 2018. “Digital Volunteer Networks and Humanitarian Crisis Reporting.” Digital Journalism 6 (7): 928–944.

- Chouliaraki, L. 2008. “The Mediation of Suffering and the Vision of a Cosmopolitan Public.” Television & new Media 9 (5): 371–391.

- Cottle, S. 2014. “Rethinking Media and Disasters in a Global Age: What’s Changed and Why It Matters.” Media, War & Conflict 7 (1): 3–22.

- Crowe, A. 2012. Disasters 2.0: The Application of Social Media Systems for Modern Emergency Management. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press.

- Davidson, W. B., and P. R. Cotler. 1989. “Sense of Community and Political Participation.” Journal of Community Psychology 17 (2): 119–125.

- Drury, J., H. Carter, C. Cocking, E. Ntontis, S. Tekin Guven, and R. Amlôt. 2019. “Facilitating Collective Psychosocial Resilience in the Public in Emergencies: Twelve Recommendations Based on the Social Identity Approach.” Frontiers in Public Health 7: 141.

- Esnard, A. M., and A. Sapat. 2016. “Transnationality and Diaspora Advocacy: Lessons from Disaster.” Journal of Civil Society 12 (1): 1–16.

- Farinosi, M., and E. Treré. 2014. “Challenging Mainstream Media, Documenting Real Life and Sharing with the Community: An Analysis of the Motivations for Producing Citizen Journalism in a Post-Disaster City.” Global Media and Communication 10 (1): 73–92.

- Galtung, J., and M. H. Ruge. 1965. “The Structure of Foreign News.” Journal of Peace Research 2 (1): 64–90.

- Global Facility for Disaster Risk Reduction. 2016. The Making of a Riskier Future: How Our Decisions Are Shaping Future Disaster Risk. Accessed 23 February 2022. https://www.gfdrr.org/sites/default/files/publication/Riskier%20Future.pdf.

- Haupt, B. 2021. “The Use of Crisis Communication Strategies in Emergency Management.” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 18 (2): 125–150.

- Heilbron, J., T. Boncourt, and G. Sorá. 2018. “Introduction: The Social and Human Sciences in Global Power Relations.” In The Social and Human Sciences in Global Power Relations, edited by J. Heilbron, T. Boncourt and G. Sorá, 1–25. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Helbing, D. 2013. “Globally Networked Risks and how to Respond.” Nature 497: 51–59.

- Hugelius, K., M. Adams, and E. Romo-Murphy. 2019. “The Power of Radio to Promote Health and Resilience in Natural Disasters: A Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (14): 2526.

- Jack, V. 2020. “Informing Refugee Communities in Greece: What Is Possible Within the Parameters of the Humanitarian Structure?” In Media, Journalism and Disaster Communities, edited by J. Matthews and E. Thorsen, 201–213. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Joye, S. 2010. “News Discourses on Distant Suffering: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the 2003 SARS Outbreak.” Discourse & Society 21 (5): 586–601.

- Kanayama, T. 2007. “Community Ties and Revitalization: The Role of Community Radio in Japan.” Keio Communication Review 29 (3): 5–24.

- Kaniasty, K., and F. H. Norris. 2004. “Social Support in the Aftermath of Disasters, Catastrophes, and Acts of Terrorism: Altruistic, Overwhelmed, Uncertain, Antagonistic, and Patriotic Communities.” In Bioterrorism: Psychological and Public Health Interventions, edited by R. J. Ursano, A. E. Norwood, and C. S. Fullerton, 200–229. Cambridge University Press.

- Kapucu, N. 2009. “Emergency and Crisis Management in the United Kingdom: Disasters Experienced, Lessons Learned, and Recommendations For The Future.” Accessed 23 June 2022. http://www.training.fema.gov/emiweb/edu/Comparative%20EM%20Book.

- Kirschenbaum, A. 2004. “Generic Sources of Disaster Communities: A Social Network Approach.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 24 (10/11): 94–129.

- Kivikuru, U. 2006. “Tsunami Communication in Finland: Revealing Tensions in the Sender-Receiver Relationship.” European Journal of Communication 21 (4): 499–520.

- Lingel, J., and M. Naaman. 2012. “You Should Have Been There, Man: Live Music, DIY Content and Online Communities.” New Media & Society 14 (2): 332–349.

- Liu, W., W. Xu, and B. John. 2021. “Organizational Disaster Communication Ecology: Examining Interagency Coordination on Social Media During the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” American Behavioral Scientist 65 (7): 914–933.

- Matthews, J. 2017. “The role of a local newspaper after disaster: an intrinsic case study of Ishinomaki, Japan.” Asian Journal of Communication 27 (5): 464–479.

- MacMillan, D. W., and D. M. Chavis. 1986. “Sense of Community: A Definition and Theory.” Journal of Community Psychology 14 (1): 6–23.

- Matthews, J., and E. Thorsen. 2020. “Introduction: Media, Journalism and Disaster Communities.” In Media, Journalism and Disaster Communities, edited by J. Matthews and E. Thorsen, 1–6. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McEwen, L., J. Garde-Hansen, A. Holmes, O. Jones, and F. Krause. 2017. “Sustainable Flood Memories, Lay Knowledges and the Development of Community Resilience to Future Flood Risk.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (1): 14–28.

- Montelli, C., J. Barclay, and A. Hicks. 2020. “Remembering, Forgetting, and Absencing Disasters in the Post-Disaster Recovery Process.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 11: 287–299.

- Morales, J. S. 2018. “The Impact of Internal Displacement on Destination Communities: Evidence from the Colombian Conflict.” Journal of Development Economics 131: 132–150.

- Pantti, M., K. Wahl-Jorgensen, and S. Cottle. 2012. Disasters and the Media. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Peelo, M. 2006. “Framing Homicide Narratives in Newspapers: Mediated Witness and the Construction of Virtual Victimhood.” Crime, Media, Culture 2 (2): 159–175.

- Pescaroli, G., and D. Alexander. 2015. “A Definition of Cascading Disasters and Cascading Effects: Going Beyond the “Toppling Dominos” Metaphor.” Planet @ Risk, Global Forum Davos 3 (1): 58–67.

- Pescaroli, G., M. Nones, L. Galbusera, and D. Alexander. 2018. “Understanding and Mitigating Cascading Crises in the Global Interconnected System.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 30 (B): 159–163.

- Ploughman, P. 1995. “The American Print News Media ‘Construction’ of Five Natural Disasters.” Disasters 19 (4): 308–326.

- Putnam, R. D. 2000. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. In Culture and Politics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Quarantelli, E. L. 2006. “The Disasters of the 21st Century: A Mixture of New, Old, and Mixed Types.” Disaster Research Centre Preliminary Papers 353.

- Reader, B. 2012. “Community Journalism: A Concept of Connectedness.” In Foundations of Community Journalism, edited by B. Reader and J. A. Hatcher, 3–20. London: Sage.

- Reilly, P., and D. Atanasova. 2016. “A Report on the Role of the Media in the Information Flows That Emerge During Crisis Situations.” CascEff Project Report 20: 1–41.

- Rheingold, H. 2000. The Virtual Community, Revised Edition: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Rodríguez, H., J. Trainor, and E. L. Quarantelli. 2006. “Rising to the Challenges of a Catastrophe: The Emergent and Prosocial Behavior Following Hurricane Katrina.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 604 (1): 82–101.

- Rothenbuhler, E.W. 1991. “The Process of Community Involvement.” Communications Monographs 58: 63–78.

- Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. 2015. Geneva: UNISDR. Accessed 23 June 2022. https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030

- Speakman, B. 2019. “Influencing Interaction: Does Technology Increase Public Participation on Community Journalism Websites?” Newspaper Research Journal 40 (1): 38–50.

- Spialek, M. L., J. B. Houston, and K. C. Worley. 2019. “Disaster Communication, Posttraumatic Stress, and Posttraumatic Growth Following Hurricane Matthew.” Journal of Health Communication 24 (1): 65–74.

- Stamm, K., and R. Weis. 1986. “The Newspaper and Community Integration: A Study of Ties to a Local Church Community.” Communication Research 13 (1): 125–137.

- Strelitz, J., C. Lawrence, C. Lyons-Amos, and T. Macey. 2018. A Journey of Recovery Supporting Health & Wellbeing for the Communities Impacted by the Grenfell Tower Fire Disaster. London: The Bi-Borough Public Health Department.

- Sreedharan, C., E. Thorsen, and N. Sharma. 2019. Disaster Journalism: Building Media Resilience in Nepal. Kathmandu: UNESCO Kathmandu.

- Sreedharan, C., and E. Thorsen. 2020. “Reporting from the ‘Inner Circle’: Afno Manche and Commitment to Community in Post-earthquake Nepal.” In Media, Journalism and Disaster Communities, edited by J. Matthews and E. Thorsen, 35–52. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sreedharan, C., E. Thorsen, L. Miles, J. Matthews, M. Sunderland and C. Baker-Beall. 2021. “Impact of Covid-19 on Journalism in Sierra Leone.” National survey report 2021. Freetown: Sierra Leone Association of Journalists. https://slaj.sl/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Sierra-Leone-National-Survey-Report-English-with-APPENDIX.pdf (Accessed 23, June 2022).

- Tekin, S., and J. Drury. 2021. “Silent Walk as a Street Mobilization: Campaigning Following the Grenfell Tower Fire.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 31 (4): 425–437.

- Thorsen, E., D. Jackson, and A. Luce. 2015. “I Wouldn’t be a Victim When it Comes to Being Heard.” In Citizen Journalism and Civic Inclusion. Media, Margins and Civic Agency, edited by H. Savigny, E. Thorsen, D. Jackson and J. Alexander, 43–61. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tierney, K. J. 2007. “From the Margins to the Mainstream? Disaster Research at the Crossroads.” Annual Review of Sociology 33: 503–525.

- Tim, Y., S. L. Pan, P. Ractham, and L. Kaewkitipong. 2017. “Digitally Enabled Disaster Response: The Emergence of Social Media as Boundary Objects in a Flooding Disaster.” Info Systems Journal 27 (2): 197–232.

- Usher, N. 2009. “Recovery from Disaster: How Journalists at the New Orleans Times-Picayune Understand the Role of a Post-Katrina Newspaper.” Journalism Practice 3 (2): 216–232.

- Veil, S. R. 2012. “Clearing the air: Journalists and Emergency Managers Discuss Disaster Response.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 40 (3): 289–306.

- Watson, C., A. Caravani, T. Mitchel, J. Kellet, and K. Peter. 2015. Financing for Reducing Disaster Risk: 10 Things to Know. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Wenzel, A. D., S. Ford, and E. Nechushtai. 2020. “Report for America, Report About Communities: Local News Capacity and Community Trust.” Journalism Studies 21 (3): 287–305.

- Wright, K. M., R. J. Ursano, P. T. Bartone, and L. H. Ingraham. 1990. “The Shared Experience of Catastrophe: An Expanded Classification of the Disaster Community.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 60 (1): 35–42.

- Zelizer, B., and K. Tenenboim-Weinblatt. 2014. Memory and Journalism. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.