Abstract

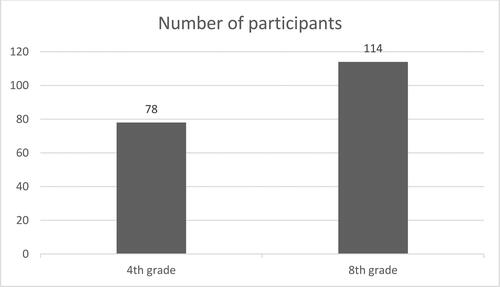

In modern school, students become active subjects in their education. The aim of this research was to determine the status of the school subject of Visual Arts in the eyes of students, therefore we studied student opinion, perception and experience related to Visual Arts classes. A total of 192 students participated in the research, including 78 fourth-grade students (40.6%) and 114 eighth-grade students (59.4%). The research was conducted in several Croatian villages and smaller towns in Split-Dalmatia County and Šibenik-Knin County. We used a survey questionnaire containing six hypotheses and research questions: results processing was done by the use of percentages, arithmetic mean, and standard deviation, as well as a t-test for independent samples. The research results show that more than half of the surveyed students would like to have the weekly number of lessons of Visual Arts increased. Although they love to participate in classes, unfortunately as many as 70% of them never visit museums and exhibitions to communicate with the contents of Visual Arts, and when they do go to cultural institutions, they are mostly taken there by their parents. The research proved that fourth-grade students of primary school perceive the subject better than eighth-grade students and assess different aspects of Visual Arts classes with higher grades. No gender differences were observed in the perception of the subject of Visual Arts. Finally, we notice that most students consider Visual Arts an important and useful subject in their education, and most students are happy to attend Visual Arts classes as this makes them feel relaxed.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, visual information is more powerful than verbal information, and understanding visual information is gained through education. Understanding visual forms and the complex world of the image requires more than innate abilities. It asks for comprehension, cognition and knowledge of visual and fine art forms acquired through education. Given that modern civilization, as stated by Briski Uzelac (1995), can be called the civilization of the image, our century can be called the century of visual communication. Looking, seeing, and knowing are all intertwined, Jenks (Citation2002) argues, and seeing accompanied with knowledge constitutes the world in which we live. Duncum defines ‘visual culture as a transdisciplinary field’ (Duncum, 2002, p. 14), which would mean that social reality is imbued with images today, especially because of visual technology without which we can no longer imagine the modern world. Mitchell (Citation2007) believes that visual culture encompasses many areas of life, from the areas of unconscious cognition acquired by everyday looking to complex observation techniques that include optical devices, aids, virtual technologies, and various theories of visuality. Therefore, at the beginning of the 21st century, we see a strong momentum of visual culture in which electronic media dominate social reality and with their strong visual imagery shape social consciousness, thus becoming a very important medium in creating identity and spreading knowledge. ‘Communication through images today is a multiplied and networked world of visuality’ (Paić & Purgar, Citation2009, p. 7).

It is indisputable, therefore, that visual culture due to its importance is included in various education programs and especially in compulsory education for all students. Visual and fine arts education should be a component of all modern curricula of today's school. (Anderson, Citation2003) points out that visual culture teaching programs are found in study programs of culture, art history, graphic design, and various communication studies. Likewise, visual culture can be associated with popular culture, television, cinema, and digital technology. This indicates that the contents of the visual culture are part of students' everyday life. Through educational contents in Visual Arts classes, children and the young gradually master the understanding of visual messages and get acquainted with the contents of visual culture. This helps them establish a dialogue with the period in which they are growing up and participate in their social environment, thus getting the access to cultural trends of their time. The subject Visual Arts introduces students to the vast world of fine arts and visual culture, but also develops intellectual and emotional abilities, which contributes to the overall development of students.

In education, science and art are often opposed due to the prejudice that science addresses reason and art addresses emotions. This difference is especially seen in the different approaches to science- and art-related subjects in compulsory education. There is often a prejudice in society that the sole purpose of art-related subjects is leisure, creativity and aesthetics, while the purpose of science-related subjects is learning, knowledge and the development of logical thinking (Mišurac & Kuščević, 2016).

The problem of the position of art-related subjects in education lies in many prejudices that affect these subjects in general education systems. Teachers, parents, students, and the wider community talk about the division of school subjects into major and minor, into very important subjects and those that are not, or those that do not have special use in the future preparation of students for life. However, since all school subjects equally try to develop students' knowledge and abilities and thus contribute to their development, such division does not make sense. These are the problems that educational sciences need to explore.

2. Exploring the opinions and perception of the school subject Visual Arts in Croatia

Gentry, Gable and Rizza point out the long-time interest of researchers in the ways in which subjects think about the activities in which they are involved (Gentry et al., 2002).

In Split-Dalmatia County and Šibenik-Knin County, there is not much research on what students as participants in the teaching process think about Visual Arts classes. A research on student assessment as well as the realization and evaluation of educational objectives of Visual Arts was done by Brajčić and Arnautović in 2002. A total of 193 eight graders participated in the research. It was concluded that students like drawing the most, followed by painting and modeling. According to the results, the respondents expressed readiness (96%) to get involved in the improvement of the teaching process in the subject of Visual Arts, which shows that students want to be active subjects in creating the teaching process (Brajčić & Arnautović, Citation2002).

The above authors continued their research in 2007. In the new research involving 432 eighth graders, they explored evaluation regarding the school subject of Visual Arts. The students in the final grades of primary school self-assessed the level of their practically acquired knowledge in the field of visual arts. It was found that students prefer drawing to painting and modeling, and that they are motivated and willing to participate in the program changes. Students expressed their willingness to participate in the search for more appropriate teaching methods in the school subject of Visual Arts (Brajčić & Arnautović, Citation2007).

The opinions of fourth graders on the subject of Visual Arts and their understanding of grading in Visual Arts classes were published in a study involving a total of 300 primary school students conducted in 2010 by Dobrota, Kuščević and Burazer. The results have shown that there is no difference in attitudes between the students attending schools from the two counties and that boys and girls like Visual Arts lessons very much. Students consider Visual Arts to be a subject of medium importance in their education, and they would like to have both a numerical and a descriptive assessment of their achievements. A large percentage of students were graded excellent in this subject. Moreover, the students state that they like it when they evaluate the works together with the teacher and talk and exchange experiences (Dobrota et al., Citation2010).

On a sample of 303 respondents, Kuščević et al. (Citation2009) explored the attitudes of eighth graders about the subject of Visual Arts. More than half state that they like this subject or like it very much, and 45.5% of respondents express dissatisfaction with the schedule of art classes (one hour per week). Most students believe that this should be increased by at least an additional hour per week. The research showed that more than half of the students, 57.8%, do not have the habit of visiting museums and galleries or art exhibitions. Visual Arts classes did not influence (54.1%) the formation of personal art taste, according to almost half of the students, while 38% of students believe that they learned to use art techniques and materials during class activities. There was no statistically significant difference in the evaluation of the subject in eighth-grade students with regard to school success and gender.

Matijević, Drljača and Topolovčan explored students' evaluation of their experiences in Visual Arts classes. The research involved 255 students attending the final grades of a nine-year compulsory primary school and a grammar school in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The analysis of the results shows positive student evaluation of Visual Arts classes and no difference in the evaluation of Visual Arts classes with regard to student gender, type of school and final school success. Hence, irrespective of the student gender, type of school (primary school or grammar school) and school success, they equally positively assess Visual Arts classes. There is a difference in the assessment of Visual Arts classes with regard to the grade, i.e., eight graders or younger students have more positive assessments than students in the ninth grade of primary school and second grade of high school (Matijević et al., Citation2016).

Relying on the above research, we conducted a study in which we wanted to explore the experiences and attitudes of fourth- and eighth-grade primary school students towards the subject of Visual Arts.

3. Research object, aim and hypotheses

The aim of the research was to explore the perception, experiences and opinions of fourth- and eighth-grade primary school students related to the subject Visual Arts.

In accordance with the formulated aim, the following research problems were defined:

to examine whether primary school students perceive Visual Arts as an important or unimportant subject in their education.

to examine the reflections of primary school students on whether they consider Visual Arts a useful subject in their education.

to examine whether Visual Arts classes relax students or makes them feel burdened.

to examine whether students think it is necessary to increase the weekly number of lessons of this subject.

to examine whether students visit art institutions and with whom.

to examine students' experiences in Visual Arts classes.

Based on the defined research aim and problems, the following hypotheses were set:

H1: Visual Arts is an important and useful subject in student education.

H2: Students believe that it is necessary to increase the weekly number of lessons of this subject.

H3: Students often visit museums and art exhibitions.

H4: Fourth-grade students, compared to eighth-grade students, have better experiences in Visual Arts classes.

H5: Fourth-grade students, compared to eighth-grade students, list Visual Arts among their favorite subjects.

H6: Female students like Visual Arts classes more compared to male students.

3.1. Research methodology

3.1.1. Sample and data collection procedure

A total of 192 students participated in the research, including 78 fourth-grade students (40.6%) and 114 eighth-grade students (59.4%) (). The research was conducted in several Croatian villages and smaller towns, including Baška Voda (Bariša Granića Meštra Primary School), Brela (Dr. Franjo Tuđman Primary School), Šestanovac (Dr. Fra Karlo Balić Primary School), Hrvace (Dinko Šimunović Primary School), Trilj (Trilj Primary School) and Šibenik (Faust Vrančić Primary School). With regard to the place of residence, (39.1%) of the students attended schools in rural areas, while (60.9%) of them attended school in urban areas. The distribution of study participants by gender was as follows: (45.3%) respondents were male and (54.7%) female. The survey was conducted in schools with the help of a survey questionnaire distributed to students. It took 10 minutes for the students to complete the questionnaire.

3.1.2. Instrument

For the purposes of this research, a two-part questionnaire was designed. The first part of the questionnaire contained questions related to socio-demographic features of students (gender and age) and opinions related to the subject of Visual Arts and students' tendencies to visit cultural institutions (museums and galleries).

The second part of the questionnaire contained questions that examined students' experiences in Visual Arts classes (how much the learning material was clearly explained to them, how much creativity and originality were encouraged in teaching, whether their opinions were respected in classroom, and whether they gladly attend art classes). The aim was also to determine if they find the subject interesting, if during the classes their activity and independence were encouraged, if the classes were connected with other school subjects, if they came to know various artworks belonging to different nations and cultures. In this part of the questionnaire, we explored also whether students in art classes got familiar with various art techniques and materials and we analyzed the way in which the artworks were evaluated and graded. Moreover, the questionnaire tested if the students have adopted applicable knowledge to be used in their future life and education.

A multipoint Likert-type scale was used in the questionnaire. The task of the respondents was to express how much they agree with each statement by choosing one of the following options: 1—I completely disagree, 2—I disagree, 3—I do not agree or disagree, 4—I agree, 5—I completely agree.

The particles used were chosen due to the fact that they represent statements with the help of which it is possible to best answer research questions and record student self-assessments related to the subject.

At the end of the questionnaire, this school subject was ranked in relation to other subjects included in the school curriculum. The participants were earlier explained the purpose of conducting the research, guaranteed anonymity, and asked to answer questions honestly and accurately. The starting point were the six hypotheses and research questions: the results were processed in terms of percentages, arithmetic mean and standard deviation, and a t-test for independent samples.

4. Results and discussion

In order to obtain data on students' opinions, perceptions and experiences related to Visual Arts classes, we formulated questions and statements that we considered important for this subject. Since the students of the fourth and eighth grade of primary school were asked the same questions in the statements related to their class experiences, we will show a comparison of the answers of both groups of respondents.

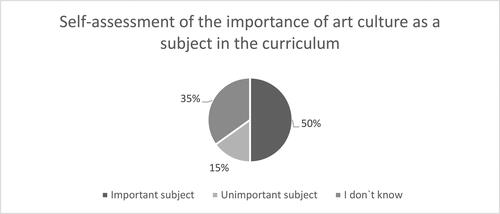

In the first question, we wanted to explore how primary school students perceive Visual Arts, either as an important subject or unimportant subject in their education, starting from the hypothesis H1: Visual Arts is an important and useful subject in student education.

Most of the surveyed students consider Visual Arts an important subject (50%), while only a smaller portion of students believe that it is an unimportant subject (15%) included in the curriculum of compulsory education. More than a third of respondents do not know whether to describe Visual Arts as important or unimportant school subject (35%) ().

Figure 2. Presentation of the participants' answers to the question about the importance of Visual Arts.

Source: Authors.

In the research (Kuščević et al., Citation2009), we can see how students (26.1%) like and as many as (60.9%) very much like Visual Arts classes, yet they consider the subject to be of medium importance in their education (65.2%). Our research marks progress in the perception of this subject in students' opinion.

The value and importance of a school subject derives from educational goals defined in the school curriculum. Regarding the purpose and description of the subject Visual Arts, it is written that ‘the purpose of the subject Visual Arts (VA) is to shape the personal and social identity of students; ennoble and enrich the image of themselves and the world in which they live; develop the ability to think and act creatively; adopt artistic and visual literacy (understanding art strategies and concepts, understanding the complex visual environment and its critical judgment, evaluation and active design) and practical application of techniques, tools and media’ (Curriculum of the subject Visual Arts for primary schools and the subject Fine Arts for grammar schools, NN//2019, 1). The very description of the purpose of this subject contains many important goals for life in the modern world. Given that the twentieth century had been recognized as a new time of visual culture and visual media, teaching Visual Arts certainly contributes to easier understanding and navigation through the visuality of our time, which in its visual messages often appears to be chaotic, banal and confusing, this making a 21st-century person a superficial absorber of visual impressions. Hence, the aesthetic sensitivity of today's human cannot be nurtured casually, but consciously, and art education plays an important role here (Damjanov, Citation1991). Students of this age, of course, are not aware of what is written in the curriculum, but subconsciously participate in the time in which they live and understand the importance of the image, the importance of the visual in the 21st century. Therefore, 50% of them assess Visual Arts as an important subject in their education.

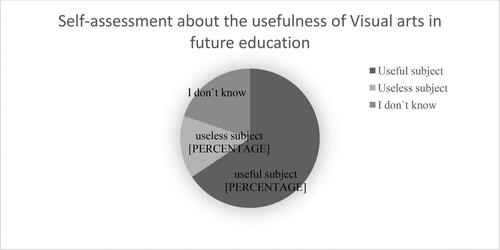

In the second question, we wanted to analyze the opinions of primary school students on whether they consider Visual Arts a useful subject in their education ().

Figure 3. Presentation of the participants' answers to the question about the usefulness of Visual Arts.

Source: Authors.

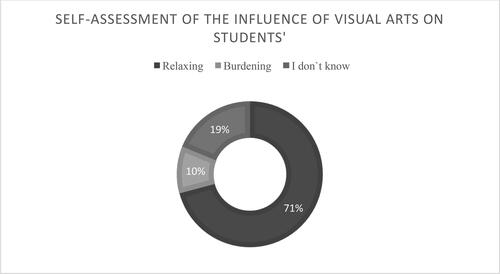

The results clearly show that more than half of the surveyed students (66%) consider Visual Arts a useful subject, (14%) of them consider it a useless subject, and (20%) do not know whether it is useful or useless in their education. As the curriculum points out, Visual Arts classes fully develop students in various spheres of their development: ‘Teaching through fine arts and teaching fine arts greatly contributes to the overall development of students and the young by nurturing and encouraging the three basic areas of human personality and activity—psychomotor (active), affective (emotional) and cognitive (intellectual)’ (Curriculum of the subject Visual Arts for primary schools and Fine Arts for grammar school, NN//2019, 1). We thus believe this subject is indisputably useful in the future education of students, which is also noticed by students. Furthermore, we wanted to examine student self-assessments regarding the influence of Visual Arts on their mood in the classroom ().

Figure 4. Presentation of the participants' answers regarding the influence of Visual Arts on them.

Source: Authors.

As we can see from , most students (as much as 71%) think that art classes relax them, (10%) of them are burdened by these classes, and (19%) do not know how to answer this question. However, a large number of students perceive art activity as relaxing. ‘Fine arts fill with positive energy, relax, give a sense of fulfillment and, importantly, raise self-confidence and create a sense of community with other participants who share the same interests’ (https://www.profil-klett.hr/kreativnost-na-kraju-skolske-godine).

In the fourth research question, we examined whether students think that it is necessary to increase the number of Visual Arts lessons. In the second hypothesis H2 we assumed that the students believe it is necessary to increase the weekly number of Visual Arts lessons.

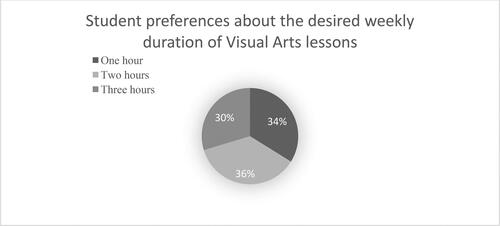

According to the results, most students believe that Visual Arts lessons should last more than one school hour, thus 36.5% of students would like classes to last two school hours, and 29.7% of students would like classes to last as many as three school hours per week (). Thus, 66.2% of students would like to significantly increase the weekly number of Visual Arts lessons.

Figure 5. Presentation of the participants' answers to the question about the desired weekly duration of Visual Arts lessons.

Source: Authors.

Similar results have been found in previous studies. In a research (Kuščević et al., Citation2009) on 303 respondents in the eighth grade of primary school, it was found that as many as 45.5% of students believe that the number of Visual Arts lessons should be increased, thus 36.3% of them would like to increase classes to two hours per week, and 9.2% to even more than two school hours per week. A similar study was conducted with teachers, and they also confirm the insufficient number of Visual Arts lessons. In another research (Pivac & Kuščević, Citation2004) involving 202 teachers from thirty-four schools from the Split-Dalmatia County in Croatia, it was found that (89%) of the surveyed teachers confirm the insufficient number of Visual Arts lessons, and even (70%) of the surveyed teachers hold more lessons on their own initiative. In the above research, (93%) of the teachers, regardless of their work experience, believe that it is necessary to increase the number of Visual Arts lessons in the curriculum for additional two hours per week. Therefore, the opinions of both students and teachers should be respected when creating the curriculum, especially if we take into account that Croatian schools, compared to other countries in Europe, offer a very small number of Visual Arts lessons. This problem could be overcome if students were offered elective courses in order to develop all the potential in terms of their motivation. One school hour of Visual Arts in general education specified in the curriculum testifies to the social prejudices that still underrate the importance of the field of arts compared to the field of science in compulsory education.

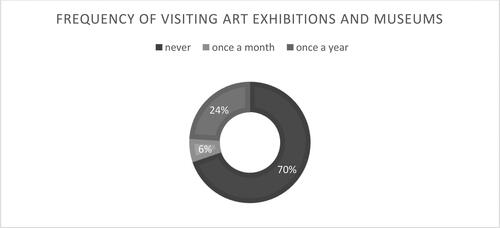

In the fifth research question, we determined whether students visit art institutions and who with. We set the third hypothesis accordingly: H3: Students often visit museums and art exhibitions. The results () showed the following: unfortunately, 70% of participants never visit museums and exhibitions. Only 24.0% of students visit museums and exhibitions once a year, and only 6.3% visit them once a month ().

Figure 6. Presentation of the answers to the question of how often students visit museums and art exhibitions.

Source: Authors.

Those students (30%) who visit museums and art exhibitions once a month or once a year do that mostly with their parents (21.2%), with their class (7.1%), and some students go with their grandparents (1.0%).

In the already mentioned research (Kuščević et al., Citation2009), it was found that students do not visit museums and galleries. In this research, cultural institutions were often visited by only (5.6%) students, sometimes by (36.6%) students while (57.8%) students never went to a museum or an art gallery or art exhibitions. This shows that today even fewer students visit museums and art exhibitions than ten years ago, which is not satisfactory if we want to develop students' aesthetic sensitivity to both fine arts and the overall visual environment. In the same research (Kuščević et al., Citation2009), the students were asked what they think who has a crucial role in encouraging their inclination towards fine arts, and the results showed that students (59%) think that school is a key factor in presenting art activities to students. When asked who they go to museums and art exhibitions with, we notice that only (7.1%) students go to cultural institutions with their class. Art education certainly involves communicating with art forms, which presupposes going to museums and art galleries, and according to these results teachers do not have the habit of visiting cultural institutions with students, although art curriculum foresees such teacher activities.

H4: Fourth grade-students, compared to eighth-grade students, have better experiences in Visual Arts classes.

In order to test the fourth hypothesis and to check whether there is a difference in student experiences in Visual Arts classes, we compared the responses of fourth- and eighth-grade primary school students (). We used a statistical test called the t-test for independent samples to compare the average differences between the two groups.

Table 1. Comparison of answers of fourth- and eighth-grade students of primary school to questions about experiences in Visual Arts classes.

Fourth graders, on average, felt more that the learning material of the subject of Visual Arts was clearly explained to them (). Also, they felt more that their creativity was encouraged in classes. Compared to eighth graders, they more easily connected the contents of Visual Arts with other subjects. The only answer which showed no difference between the fourth- and eighth-grade students related to the part saying that contents of Visual Arts could be better connected with other teaching contents. Furthermore, fourth graders emphasized that their activity and independence were encouraged in class, and they more gladly attended the lessons compared to eighth graders. In addition, the contents of the subject Visual Arts are more interesting for fourth-grade students than for eighth-grade students. The fourth graders also felt that the skills they learned in class would practically help them in their future lives, and that they learned a lot of new and different art techniques. Finally, fourth graders felt that their grades were clearly explained and that they often analyzed them with the teacher and other students.

Due to different experiences in teaching related to different contents of Visual Arts, fourth-grade students have a better perception of the subject than eighth-grade students.

H5: Fourth-grade students, compared to eighth-grade students, list Visual Arts among their favorite subjects.

Visual Arts is second favorite subject for fourth graders (), preceded by Physical Education. Eighth graders stated that the subject of Visual Arts is only their fourth favorite subject. There is also a difference in student duties. Fourth-grade students have only seven compulsory subjects, while eighth grade-students have as many as 12 subjects. Physical Education was the favorite subject in both groups. While the Croatian language is the least popular among fourth graders, eighth graders' least favorite subjects relate to natural and technical sciences: Chemistry, Physics and Technical Culture ().

Table 2. Average ranks on the attractiveness of individual school subjects for fourth graders.

Table 3. Average ranks related to the attractiveness of individual school subjects for eighth graders.

H6: Female students like Visual Arts classes more compared to male students.

In the last hypothesis, we wanted to determine () student attitudes with regard to gender. The initial hypothesis predicted that girls would like Visual Arts classes more than boys.

Table 4. A comparison of the answers of boys and girls in first and eight grade of primary school to the questions about their experiences in Visual Arts classes.

A comparison of student attitudes with regard to gender reveals equal results. Despite the initial hypothesis that girls would better perceive Visual Arts classes, the results show that there is no difference in attitudes towards Visual Arts between male and female students. The only exception is that boys felt more that their creativity and individuality were encouraged in class.

5. Conclusion

A holistic approach to education presupposes both art- and science-related subjects in the education of children and the young. In the modern world of fast visual information, an aware and critical view is important, therefore the modern education recognizes the usefulness and importance of visual and fine arts education.

This research led us to the following conclusions:

The first hypothesis H1 was confirmed: Visual Arts is an important and useful subject in education. Primary school students are aware that contemporary culture is becoming increasingly visual and thus dominant in relation to the written word. Visual Arts classes help students relax.

Having noticed the importance of Visual Arts classes, the students (even 66.2% of them) stated they would like to have weekly number of lessons of Visual Arts increased. This result confirms the second research hypothesis.

In the third hypothesis, we assumed that students often visit museums and art exhibitions, however, this hypothesis was not confirmed. The results show that students (70%) do not have a habit of visiting cultural institutions. Most students do not attend art exhibitions, which is certainly not satisfactory if we want quality contact of students with works of fine arts, which is especially important for the development of aesthetic sensitivity of students. Moreover, the school should encourage going to cultural institutions as this would systematically influence the art education of students.

In the fourth hypothesis, we assumed that fourth-grade students of primary school, compared to eighth-grade students, have better experiences in Visual Arts classes. On average, fourth graders felt that the learning material was clearly explained to them and that their creativity, activity and independence were encouraged in class. They also felt that they found it easier to connect the contents of Visual Arts with other subjects. Fourth graders found the contents of Visual Arts more interesting than eighth graders, and they attend classes more gladly. In Visual Arts classes, fourth-grade students learned a lot of new and different art techniques and believe that the skills they learned in class will be useful in their future lives. Furthermore, fourth-grade students are satisfied with grading methods in Visual Arts classes. The fourth hypothesis was thus confirmed.

In the fifth hypothesis, we assumed that fourth graders would list Visual Arts among their favorite subjects compared to eighth graders. This hypothesis was also confirmed. The results show that for fourth grade-students, Visual Arts is the second favorite subject, preceded by Physical Education. This is probably due to the fact that in class the students play, learn, relax, and acquire knowledge that can be useful for life in the 21st century.

In the last hypothesis, we assumed that girls would show better attitudes to Visual Arts classes than boys. Yet, this hypothesis was not confirmed. In general, there is no difference in attitudes towards Visual Arts in terms of student gender.

We limited this research to our hypotheses and research questions. We did not go into deeper analyses and reasons for student perceptions of Visual Arts classes. We believe a limitation of this research is a smaller number of research questions posed in the statements. Thus, future research could have a larger number of research particles. Moreover, future research could offer a deeper analysis of student experiences and perceptions enabling students to express their opinions related to Visual Arts classes. Any new research based on the determinants of this research contributes to the general assessment of Visual Arts classes because, as already pointed out, student opinions on the activities in which they are involved certainly contribute to the quality of Visual Arts classes.

References

- Anderson, T. (2003). Roots, reasons, and structure: framing visual culture art education. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 1(3), 5–26.

- Brajčić, M., & Arnautović, D. (2002). Učenik aktivni subjekt u realizaciji i vrednovanju odgojno-obrazovnih ciljeva predmeta likovna kultura u osnovnoj školi. Školski Vjesnik, 51(1–2), 19–25.

- Brajčić, M., & Arnautović, D. (2007). Učenička evaluacija unutar predmeta likovne kulture. Napredak, 148(2), 258–266.

- Briski Uzelac, S. (1995). Duhovna kartografija vizualnosti. Prema atektonici vizualnog. In A. Flaker & J. Užarević (Eds.), Vizualnost. Zagrebački pojmovnik kulture 20. stoljeća (pp. 27–44). Filozofski fakultet, Naklada Slap.

- Damjanov, J. (1991). Vizualni jezik i likovna umjetnost. Školska knjiga.

- Dobrota, S., Kuščević, D., & Burazer, M. (2010). Stavovi učenika četvrtih razreda osnovne škole o likovnoj kulturi i ocjenjivanju u nastavnom predmetu likovna kultura. Godišnjak Titus, 3(3), 215–227.

- Duncum, P. (2002). Visual culture art education: Why, what and how. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 21(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5949.00292

- Gentry, M., Gable, R. K., & Rizza, M. G. (2002). Students' perceptions of classroom activities: Are there grade-level and gender differences? Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 539–544. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.3.539

- Jenks, C. (2002). Središnja uloga oka u zapadnoj kulturi. In C. Jenks (Ed.), Vizualna kultura (pp. 11–46). Naklada Jesenski i Turk.

- Kurikulum nastavnog predmeta likovna kultura za osnovne škole i likovna umjetnost za gimnazije, Retrieved January 25, 2021, from https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2019_01_7_162.html

- Kuščević, D., Brajčić, M., & Mišurac, Z. I. (2009). Statovi učenika osmih razreda osnovne škole o nastavnom predmetu Likovna kultura. Školski Vjesnik, 58(2), 189–198.

- Matijević, M., Drljača, M., & Topolovčan, T. (2016). Učenička evaluacija nastave likovne kulture. Život i Škola, LXII (1), 179–192. https://hrcak.srce.hr/165130

- Mišurac, I., & Kuščević, D. (2016). Između znanosti i umjetnosti-stavovi učitelja razredne nastave o predmetima Matematika i Likovna kultura. In R. Jukić, K. Bogatić, S. Gazibara, S. Pejaković, S. Simel, & A. Nagy Varga, (Eds.), Zbornik znanstvenih radova s Međunarodne znanstvene konferencije Globalne i lokalne perspektive pedagogije (pp. 168–178). Filozofski fakultet Osijek.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. (2007). Interdisciplinarnost i vizualna kultura. Tvrđa, 1(2), 19–24.

- Paić, Ž., & Purgar, K. (2009). Predgovor, Vizualna konstrukcija kulture. Antibarbarus; Hrvatsko društvo pisaca.

- Pivac, D., & Kuščević, D. (2004). Mjesto i uloga likovne kulture u nastavnom planu nižih razreda osnovne škole. Napredak – Časopis za Pedagogijsku Teoriju i Praksu, 145(4), 462–475.

- Razvoj kreativnosti i likovnog izražavanja. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://www.profil-klett.hr/kreativnost-na-kraju-skolske-godine