ABSTRACT

Standing on the west bank of the Ping river in northern Thailand, Baan Fai Rim Ping displayed a fluid profile of multiple perspective points. Such an eccentric appearance, however, belied the senses of place and historical continuity, along with the feeling of belonging provided by this waterfront residence. Apart from occupying a prime estate near a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Kamphaeng Phet province, apposite utilisations of materials, coupled with sensational spatial organisation and formal composition, were the major contributing factors to the said characteristics. Informed by a conceptual framework of genius loci, this research presented multidimensional inquiries on the haptic design of Baan Fai Rim Ping for generating a phenomenon of place through the sensory receptions of its dwellers. Containing three thematic foci, the studies firstly examined the contextual background leading to the creation of the building. Second, the investigations concentrated on how the design parameters and elements of the house were developed and implemented. Third, the aforementioned modes of problematisation lent a basis to argue that the quality of placeness was not confined exclusively to traditional or vernacular structures, but could be found in the unorthodox aesthetics of Baan Fai Rim Ping as well.

1. Introduction

The creations of residential structures had strived for – as much as had been conditioned by – a task of delivering the quality of being at home for their inhabitants, of which major concerns were illustrated by the following critical reflections. In what methods could abodes be suitably constructed and profoundly appreciated? In what manners should individual and social identities be meaningfully cultivated and effectively conveyed through architectural designs? As the 21st century had increasingly been exposed to uncertainties in multiple dimensions, such problems had become pressing, whereas lessons from the past – including traditional forms and conventional spatial organisations – did not seem to adequately meet the challenges posed by the current way of living. Hence, the principal question had now concentrated on how to dwell in a culture without becoming overly nostalgic or anxious, yet at the same time remained perceptive and prosperous?

Apparently, one possibility to approach an answer was to look into notable individuals’ lifestyle in association with the worldviews that fashioned their self-images, further projected onto the built environment they created. In this respect, the commission of Baan Fai Rim Ping in Thailand () delineated the ways in which the residents of this waterfront habitation addressed the problem of who they were and how they should build. By illustrating how the dwellers came to be at home with their living environment, the house essentially served as a medium par excellent to articulate their identities, thoughts, and heritages, therefore personifying their existence to the immediate world and beyond.

On that basis, the forthcoming inquiries examined the manners in which the creators of Baan Fai Rim Ping celebrated the cultural roots of the inhabitants, while instantaneously asserting their modern self-identity through consumptions of material culture in a deeply conservative place like Thailand. In contrast to a large number of residential structures located in a vicinity of UNESCO World Heritage Sites throughout the country, Baan Fai Rim Ping did not allow such proximity to be a constraint that stringently regulated or dictated aesthetic expressions, but instead employed it as a mode of problematisation to cultivate the feeling of being at home through haptic senses, from which the design of the house dialectically evolved (Heritage by ASEAN Research Community (HARC) Citation2017).

Although it was generally agreed that human beings experienced the built environment with all sensory awareness (Rasmussen Citation1964; Pallasmaa Citation2005a, Citation2005b; Campbell Citation2007), Herssens and Heylighen (Citation2012: p. 1) aptly pointed out that few architects resorted to the haptic senses in mind while designing. This was, perhaps, the most valuable contributions of Baan Fai Rim Ping to architectural scholarship, since its design incorporated multisensory experience of the architectural environment beyond visual recognitions in generating the phenomenon of place, as demonstrated by the upcoming discussions.

Framed by the concept of genius loci (Norberg-schulz Citation1980, 5–6, 17–18), this research examined the design of Baan Fai Rim Ping that resulted in a phenomenon of place in three thematic foci. First, the studies undertook multidimensional inquiries on the contextual background that led to the commission of the building. Second, the investigations looked into its underlying principles of haptic design, which were manifested through the spatiality and materiality of the house in terms of architectural parameters and elements. Third, altogether, the aforementioned analyses supplied a ground to corroborate that the quality of placeness could also be discerned from Baan Fai Rim Ping–of which design was neither conventional nor stereotypical, but unorthodox and innovative ().

2. A brief overview on baan fai rim ping

After living in row houses for decades, the owners of Baan Fai Rim Ping – Kriangkrai and Pornrawee Chananitithum – envisioned the new residence as a material embodiment of their personalities. Widely recognised by the local community for being civic-minded citizens, not only did the couple treasure their cultural heritages but also seek to preserve and integrate them with the 21st century-way of life.

Situated on the west bank of the Ping river in Kamphaeng Phet province, Baan Fai Rim Ping stood across Kamphaeng Phet Historical Park that constituted a tripartite UNESCO World Heritage Site (). Positioning north of Nakhorn Chum – a once a vibrant lumbering town in the lower northern region of Thailand – the location of the house indicated that the history of urban settlements within and around the city of Kamphaeng Phet played a crucial role in the acquisition of property by the Chananitithum in 2010. Apart from a panoramic view of the river, the sizable estate (approximately two hectares) also allowed the family, particularly the three children, consisting of two daughters and a son, to enjoy outdoor activities together.

Bordering the site was a main thoroughfare running along the bank of the Ping, giving a convenient access to other parts of Kamphaeng Phet city (about 15 minute-drive from the city centre). Nevertheless, at the same time, the location was remote enough to secure privacy and tranquillity for the Chananitithum family. With the scenic vista of the Ping to the east, the property was surrounded by a rural landscape – characterised by patches of farmland, rice fields, orchards, and scattered residential structures – whereas a mountain range formed a backdrop to the west ().

Under the supervision of architect Surasak Kangkhao, the construction of the house began in 2013, encompassing six bedrooms and nine baths in combination with a ten-car garage, spacious outdoor terrace, and swimming pool. Being a relatively large residential structure (4,300 sq.m.), the building was completed in late-2016 with a total cost of three million US. Dollars. In addition to the five members of the Chananitithum family, the house contained accommodations for Kriangkrai and Pornrawee’s parents , as well as visiting guests().

Since the completion of Baan Fai Rim Ping, the Chananitithum had hosted communal gatherings at their riverside abode, which were sometimes presided by the provincial governor. The couple had also graciously agreed to turn their house into a learning centre for architectural students – Thai and foreign alike – on several occasions. Recent international guests included graduate students from the Royal College of Art, UK, and Ball State University, USA, in 2018, as well as trainees from 10 nations who attended a workshop organised by the International Association for the Exchange of Students for Technical Experience (IAESTE) in 2019.

Conceptually, the term “home” contributing to the phenomenon of genius loci at Baan Fai Rim Ping referred to a definition coined by David Benjamin (Citation1995) that:

“The home is that spatially localised, temporally defined, significant and autonomous physical frame and conceptual system for the ordering, transformation and interpretation of the physical and abstract aspects of domestic daily life at several simultaneous spatio-temporal scales, normally activated by the connection to a person or community such as a nuclear family” (p. 158).

Serving as a keyword in translating the intrinsic association between anthropic environment and nature, “home” then provided a ground for employing the surroundings as an essential device in generating a scene of domestic intimacy and event while welcoming the phenomenon of spatial configurations that naturally took place in accordance with its perennial cycle. In effect, Baan Fai Rim Ping exemplified a well-balanced built form that meaningfully provided the quality of being at home for the Chananitithum family. On the one hand, its design roots and tools deeply immersed in the local tradition of a riverine settlement when the Ping remained a major mode of transportation, as evident from several references to both historic and vernacular structures in the area, including the uses of: (1) river-oriented spatial planning; (2) central courtyard occupied by a large tree; (3) elevated floors to counter annual flooding; (4) terraces as a transitional zone between outdoor and indoor space; (5) teakwood floors and furniture; (6) laterite bricks for masonry walls and walkways in the garden; and (7) indigenous fragrant flowering plants. On the other hand, the house was conceived in modern lines that transferred it into a deeper level of comfort by creating a fundamental relationship of human shelter and nature () that led to a harmonious coexistence between architecture and the landscape of Kamphaeng Phet.

As shown by the following discussions, it became apparent that beyond creating thoughtful connections between spaces of dissimilar physical identity, the design of Baan Fai Rim Ping reaffirmed the importance of formal composition and spatial configuration, in conjunction with materiality and symbolism, in engaging a deeper state of being. Akin to the works of humanist architects such as Villa Mairea by Alvar Aalto, the environment of this riverside dwelling was characterised by continuous transformations of space and forms, which were devised to serve specific purposes yet flexible enough to host various kinds of occupants and activities.

3. Philosophical framework and methodological approach

As a consequence of close collaborations between the owners and architects, Baan Fai Rim Ping – in its capacity as a home for the Chananitithum family – exemplified the innate intertwining between nature, shelter, community landmark, and inner discovery. The design of the house incorporated a combination of these theoretical foundations.

3.1. Phenomenology

The notion of being at home owed its philosophical origin from contemplating on the question of what it meant to “be-in-the-world.” On that basis, Heidegger (Citation1971: pp. 150–51) wrote that our trouble with dwelling today did not lie merely in a lack of houses, but instead in the fact that we must learn to dwell by searching for the nature of dwelling. The process was a quest to comprehend the essential significance of being-in-the-world. Dwelling, therefore, signified the act of remaining in a place and being situated in a certain relationship with existence – a relationship that was typified by nurturing – enabling one to understand the world around him/her as it evolved.

In other words, as suggested by Mugerauer (Citation1994, 73), Heidegger’s remarks implied that humankind must continue to explore how architecture and urban space elicited a sense of belonging, which in return generated a sense of place that contributed to our existential significances. In built things and forms, we belonged to a disclosed reality, and in this reality, we were able to realise our own mortal nature, together with our proper relationship to the earth, its water, heavens, and seasons, and even to the hidden divinity. The “built” thus became a “place,” which created “space” for an ontological event for us to experience via our corporeal senses.

In a nutshell, not only did Heidegger’s statements call for the architectural profession to address human sensibilities beyond visual aesthetics in creating and understanding the built environment but cause a major paradigmatic shift in architectural design and education as well. His theoretical premise was epitomised by the design of Baan Fai Rim Ping that allowed its dwellers – members of the Chananitithum family – to became at home with their living environment.

3.2. Genius loci and senses of place

The notion of being at home employed by Baan Fai Rim Ping was closely identified with a belief in the spirit of place – or genius loci – revealing an intimate connection among the idea of human “being-in-the-world” and spatiality, locality, and embodiment. Such a philosophical link could also be seen from in the works of Heidegger (Citation1971) and Merleau-Ponty (Citation1978) that reappeared in the work of other phonological thinkers – especially the concept of genius loci by Norberg-schulz (Citation1980) – indicating the total and intertwined man–place relationships.

Developed from historical examinations of place making and the basic properties or characteristics that produced the “spirit” or “genius” of a place (locality), Norberg-Schulz proposed that the role of architecture was to provide a means to visualise the genius loci, whereas and the task of architects was to create meaningful places that facilitated human beings to dwell. In this regard, the term “dwelling” referred to something more than shelter, but signified the spaces where life occurred (Norberg-schulz Citation1980, 5). Likewise, “place” denoted “the concrete manifestation of man’s dwelling,” which was constituted by material substance, shape, texture and colour, all of which bestowed “character” or “atmosphere” (Norberg-schulz Citation1980, 6). Via explorations of all these factors – along with their meanings, which were gathered by a place, a true understanding of genius loci could be attained in terms of a total phenomenon. On the contrary, when a focus on the identity or genius of a place became absent or was forgotten, “loss of place” or “placelessness” was often an outcome (Norberg-schulz Citation1980, 190).

Although Norberg-Schulz had frequently been criticised as being strongly nostalgic for his perception of place and vision for its (urban) revitalisation in bringing about a deeper symbolic understanding of places (Jivén and Larkham Citation2003, 70), he always emphasised that “to respect the genius loci did not require a copy of old models” (Jivén and Larkham Citation2003, 182). Overall, Norberg-Schulz’s repudiation of imitations of traditional forms of towns and buildings lent a basis for Baan Fai Rim Ping to express a sense of place and belonging, as well as to act as a material embodiment for the feeling of being at home of the occupants, notwithstanding its eccentric formal composition and unconventional spatial configuration ().

3.3. The haptic way of living and designing

Since the 1980s, architectural scholarship had increasingly recognised bodily movements through space as a versatile methodological approach to architectural design and studies while criticising that architects mostly knew, thought, and designed visually (Herssens and Heylighen Citation2012). At the same time, several studies had argued that because modern civilization was dominated by visual recognition (Cousins and Whitmore Citation1998, 2; Pallasmaa Citation2005a, Citation2005b; Herssens and Heylighen Citation2007; Ryhl Citation2009; Passe Citation2009), vision was often quoted as the spatial sense par excellence (Foulke Citation1983).

Correspondingly, a number of methods to effectively scrutinise the phenomenon of “place” via the haptic senses had been established, particularly in terms of design and research tools. For instance, Lyndon and Moore (Citation1994: p. xiii), argued that physical activities, bodily movements, and intimate contacts with both built forms and natural landscape gave opportunities to formulate knowledge about places that could not otherwise be achieved, if one were to rely exclusively on his/her visual means. Moreover, in his reviews on the methodological approaches for architectural pedagogy, O’ O’Neill (Citation2001, 3) discovered that many broader inquiries using the concept of haptic senses had engaged in new and exciting knowledge about the place experience in the present culturally complicated and socially interconnected world.

In conjunction with the abovementioned theoretical propositions, the creation of Baan Fai Rim Ping was inspired by Schütz (Citation1979, 35), who advocated the idea of going beyond everyday assumptions of our natural attitude to search for essential meanings and foundations of taken-for-granted life experiences (also see: Husserl Citation1958). Hence, by adopting Schütz’s principle as the modus operandi, the design process of this waterfront residential structure encompassed: (1) the exploration and appreciation of architecture and natural landscape via the corporeal senses; (2) the acts of defining, analysing, and interpreting the phenomenon of places; and (3) the synthesis and reconstruction of haptic experiences that did not restrict to quantifiable information in making sense out of the world, but admitted on equal terms, non-sensory data like relations and values, as long as they presented themselves intuitively.

As noted by Stefanovic (Citation1998, 33), the design (or problem-solving) process by means of haptic senses for Baan Fai Rim Ping was primarily intended to discover and describe the world spontaneously and pre-reflectively, rather than validating hypotheses, analysing causal relations, or synthesising conjectural theories of existence. In a corollary view, by alluding to Bachelard (Citation1969: p. xxiii), another statement could be put forward that by promoting a haptic way of living, the design of the house derived from subconscious psychological level of the inhabitants through the exercises of their corporeal senses in terms of interplays between: (1) the perceptions that could be consciously reflected upon; and (2) the impressions that arose spontaneously within the activity of the transcendental imagination.

In sum, under a theoretical framework of phenomenology, Baan Fai Rim Ping could be: (1) experienced through the Aristotelian senses of ophthalmoception (sight), audioception (hearing), olfacoception (smell), and tactioception (touch) or even gustaoception (taste); and (2) at the same time by other stimuli beyond those governed by the traditional awareness, such as thermoception (temperature), proprioception (positional awareness), equilibrioception (balance), ophthalmoception (depth of field), kinesthesioception (movement), nociception (pain), and chronoception (time) (see: Sorabji Citation1971, 55).

3.4. architectural design as a participatory process

Since his formative years in professional practice, architect Surasak Kangkhao had been an advocator of participatory design in architecture. Deriving from an amalgamation between action research and sociotechnical design, this methodological approach – abbreviately called PD – was originally developed by trade and labour unions in Scandinavian countries during the 1960s and 1970s, emphasising on a political dimension of user-empowerment and democratization of decision-making process (see: Computer Professionals for Social Responsibilities, 2005; Bannon and Ehn Citation2013).

Incorporating the principle of co-operative design – or what had simply been known as co-design nowadays (see: Sanders Citation2008) – the term PD signified a modus operandi seeking to actively engage all stakeholders, both current and future ones, involved in collaboration efforts on architectural design (Van der Velden and Mörtberg Citation2015, 41). Concentrating chiefly on procedures, PD strived to generate a built environment that was more responsive and appropriate to the cultural, emotional, spiritual and practical needs of its users (see: Sanders Citation2008;Sanders and Stappers Citation2014).

Informed by Newman and Thomas (Citation2008), Baan Fai Rim Ping employed a PD process in terms of: (1) a visualising tool to help all stakeholders express their creative, tacit, and critical thoughts, together with reflections upon the design of the dwelling; and (2) a placemaking discourse for members of the Chananitithum family – especially Kriangkrai and Pornrawee – to construct a shared definition of “being at home” based on their worldviews, ways of life, haptic experiences with the location, in conjunction with perceptions and utilisations of space.

In order to achieve better consequences and/or more predictable outcomes from utilising the PD approach, Surasak convinced all stakeholders to embrace a ground rule to facilitate and regulate the design of Baan Fai Rim Ping. Accordingly, the universally recognised International Organization for Standardization (ISO) series 9241–210 was adopted (see: ISO 9241–210, 2010). Despite being replaced by a newer version since 2019, its core content could be summarised as the followings (also see: Mahabadi, Hossein, and Hamid Citation2014, 17).

Conceptualisation stemmed from an explicit understanding of users, tasks, and environments.

Users were involved throughout the design and development processes.

Creation was driven and refined by user-centred appraisals.

Such evaluations were iterative.

Not only did the design address but also cultivate the whole user experiences.

Design team consisted of multidisciplinary skills and diverse perspectives, yet able to collaborate in unison through a PD process.

As demonstrated by the below explanations, these sextuple criteria constituted the underlying PD mechanism for Baan Fai Rim Ping, which unfolded in four different but related fashions. First, as stated earlier, the key stakeholders – namely, the owners – were involved in most if not all phases of the design process, ranging from initial identification of problems to be explored, to data collecting, documentation, and analysis, as well as implementations of final design solutions. Since PD was carried out “with” users rather than “on” them, the Chananitithum family became equal partners of the architects who largely assumed the roles of facilitators and advisors.

Second, as noted by Baldwin (Citation2012, 478), PD was not just an informative, but indeed transformative process, of which the main purpose was to solve real-world problems. At Baan Fai Rim Ping, the use of PD accommodated multifaceted architectural requirements at the same time, while the design of the dwelling continued to evolve, leading to an environmental change of a vacant property to a place of living for the Chananitithum family.

Third, PD was frequently carried out in cycles (Reason and Bradbury Citation2008, 1). For instance, in preparations for obtaining a construction permit from a responsible administrative agency, other stakeholders – including neighbours and local sages along with state officials and community leaders, such as the district chief village head persons – were also invited to partake in a series of design charrettes for Baan Fai Rim Ping at various stages. The aforementioned hands-on workshops normally happened in a sequential manner of observation, reflection, action, evaluation, and adjustment, as each cycle brought new insights and/or improvements. Acting like quasi-public hearings, these informal gatherings aimed to ensure that the proposed riverfront residence would: (1) be compliant with the governing laws and regulations; (2) not be physically or psychologically offensive to anyone; and (3) appositely represent a common identity shared by the people of Kamphaeng Phet.

Fourth, regarding the issue of user-empowerment, PD bequeathed more power to stakeholders by increasing their knowledge, skills, confidence, and agency (For detailed discussions, see: Cousins and Whitmore Citation1998). To cite some obvious examples, PD lent opportunities for the Chananitithum children to acquire first-hand knowledge on architectural, landscape, and interior designs coupled with structural engineering from interactions with the professionals, which would benefit their future academic pursuits in these fields of studies at the post-secondary level. Likewise, the design charrettes enabled Kriangkrai and Pornrawee to obtain a better understanding of how their community operated and perceived itself, which was later applied in a civic setting when the couple hosted meetings for members of the local administrative body and business community at their new riverside abode.

3.5. Ethnography

Participatory design (PD) in conjunction with haptic way of living and designing for Baan Fai Rim Ping lent both intellectual and practical grounds for this research to appropriate a methodological premise of ethnographic study from the discipline of anthropology. By examining the interactions of users/stakeholders in a specific environment, this qualitative method offered an in-depth insight into their views and actions, coupled with experiences from the phenomenon they encountered. Being a study of people in their own environment, ethnography resorted to various means of data collections and analyses, such as participant observations as well as face-to-face conversations and interviews. In a nutshell, as suggested by Sidky (Citation2004, 9), ethnography “documented cultural similarities and differences through empirical fieldwork and could help with scientific generalisations about human behaviour and the operation of social and cultural systems.”

Because anthropology looked at the past, present and future of users/stakeholders in a given community across time and space, ethnography concentrated on obtaining a comprehensive understanding on the circumstances of the people being studied (US United States of America, National Park Service Citation2021). Correspondingly, this research investigated and recorded the ways in which the Chananitithum’s worldview, way of life, and self-images–as seen by other stakeholders and the authors–were conveyed by the design of Baan Fai rim Ping (also see: Pavlides and Cranz Citation2012, 1–2).

Throughout the design and construction processes of the house that lasted from early-2013 to late-2016, the authors carried out the fieldworks by: (1) embedding themselves with Surasak and his team of architectural professionals in organising the design charrettes; and (2) interacting with the users/stakeholders, especially members of the Chananitithum, in their real-life conditions and environment. Moreover, in mid-2017, 6 months after the family had moved into the house, a post-occupancy interview was conducted, followed by another one six months later.

In executing the fieldworks, the authors relied on two ethnographic points of views called an emic (folk or inside) and etic (analytic or outside) (see: Askland et al. Citation2014: pp. 285–287). On the one hand, since both Baan Fai Rim Ping and its setting existed outside of the socio-cultural and geographical origins of the authors – the dwelling was examined via an inside-out viewpoint (emic), as it was socially perceived, customarily conceived, physically utilised, and psychologically experienced, from which architectural meanings were generated by cultural practices, perceptions, and interpretations (see: Lefebvre Citation1991: pp. 163–167).

On the other hand, prior to embarking on each of the fieldworks in Kamphaeng Phet province, the authors performed library and other archival research to learn some of what was already known about the place and people they were interested in so as not to enter the “field” unprepared. Afterward, from an outside-in perspective (etic), they undertook critical and analytical readings on this waterfront residence and its connections to the surrounding environment, which were descriptive and interpretive in nature. In comprehending how the building affected user experiences, psyches, and perceptions, the authors focused on observing, noticing, recoding, and investigating the relationships among people (notably the Chananitithum), places, social practices, cultural heritages, and built forms (see: Suri Citation2011).

In any case, a couple of cautions must be heeded. Since close interactions between researchers and people being studied were quintessential for ethnographic inquiries, the border between the two sometimes became difficult to discern. Apart from calling into question about researchers’ ideas or preconceptions, such ambiguity could obscure the line between people who provided new information and those who might profit or be harmed by it as well. As a result, the authors exercised the best efforts to refrain from manipulations and misrepresentations of findings from the fieldworks in composing what Geertz (Citation1973) referred to as “culture writing.”

Yet at the same time, because absolute neutrality and objectivity did not exist in social situations, the authors also recognised that information was socially constructed, culturally contextualised, and politically disseminated, whereas knowledge reflected the biases, priorities, or worries of people who generated it in an ethnographic endeavour. As a matter of fact, certain kinds of knowledge could potentially promote undesirable social behaviours – like stereotypification and discrimination – as people who control how knowledge was created or interpreted could wield influence over those who were not involved in its development. Therefore, the upcoming discussions on Baan Fai Rim Ping were far from being unprejudiced and exhaustive, but were selective and being influenced by ethnographic experiences during the fieldworks.

4. The phenomenon of genius loci at baan fai rim ping

Similar to Norberg-schulz (Citation1980), Surasak believed that architecture performed as a means to cultivate the genius loci, whereas the principal task of architects was to create meaningful places that helped human beings to dwell. He also recognised that “home” had always possessed a symbolic function, since people lived not only in the material world of their own physical requirements, but in the environments where societies expressed their collective histories, believes, identities, aspirations, as well as exhibitions of power and identity. Accordingly, the architect began conceiving Baan Fai Rim Ping from a historical dimension of the locale.

Be that as it may, in spite of the fact that the owners and architect recognised the importance of historical connections in devising Baan Fai Rim Ping, they did not intend to emulate built forms from the past but aimed to reinterpret architectural precedents in a manner that cultivated an expression of the zeitgeist (or spirits of the age) (Magee Citation2010, 262), while at the same time interacting with its setting. As a consequence, even though being a private residence, the house held a civic significance not only in terms of a reflection on a common identity shared by the people of Kamphaeng Phet but also a projection of an image in which the Chananitithum family–who were prominent members in this provincial community – aspired to assume.

In this respect, Kriangkrai once mentioned to one of the authors that not only was the creation of Baan Fai Rim Ping: (1) a self-reward to himself and his family after decades of backbreaking works in agroindustry; but also (2) an exemplar in built form to inspire the local populace that self-made fortune along with a well-balanced lifestyle could be achieved in Kamphaeng Phet, thus negating a need for migrations to seek them elsewhere (Chananitithum Citation2017a).

As a matter of fact, after its completion, Baan Fai Rim Ping had received substantial interests from architectural community in Thailand, as exhibited by an increasing number of publications–both printed and online–on this riverside dwelling in popular magazines since 2018. Some of these articles contained excerpts from interviews with Kriangkrai and Pornrawee as well, presenting inside-out (emic) reflections on how their family background, way of life, haptic experiences with the location, as well as perceptions and utilisations of space brought the design of the abode to final configuration.

For instance, Kriangkrai stated that he envisioned the site plan of Baan Fai Rim Ping to be an analogy of the spatial arrangements of the historic town of Kamphaeng Phet, a strategic garrison from the 13th to 18th centuries where city walls and fortifications marked the boundary of rectangular urban area. Accordingly, ditches were excavated around the property with bulwark-like fences standing behind them. While both defensive elements metaphorically alluded to the moats and ramparts surrounding the old Kamphaeng Phet city – of which name literally meant “wall of diamonds” – they acted as flood prevention devices for the entire estate as well (see: Pikulsri Citation2018).

As for the civic implication of the house, the owners explained that they did not foresee their dwelling to officially serve as a community centre, but to become a place of gathering in an informal setting for those who possessed similar interests and passions with them in learning and preserving the cultural heritages of Kamphaeng Phet. In conjunction with the architectural references to historic and vernacular structures – i.e., central courtyard, terraces, elevated floors, teakwood, and laterite – representations of a common identity shared by the native s people in the design of Baan ai Rim Ping were strengthened by the fact that the couple hired several local labours, contractors, craftsmen especially carpenters, artists, and designers, not to mention the architect, to collaborate on this waterfront residence. So, a feeling of collective pride in bringing the building into existence ran high among them. The Chananitithum further stipulated that indigenous resources must be used as much as possible, resulting in approximately 90% of the house was made from structural and decorative materials originating within 100 km.-radius from the construction site (Ibid.).

In addition, a post-occupancy interview in late-2017 revealed that Kriangkrai and Pornrawee had subsequently purchased adjacent plots of land, of which ownership would be transferred to their son and daughters when they grew up. Notice a chronic problem of landless farmers in Kamphaeng Phet province, the civic-minded couple allowed those suffered from such predicament to grow and cultivate crops on their newly acquired properties on a yearly basis for free of charge under a strict condition that the fertility of the soil must be maintained. In consequence, the area around Baan Fai Rim Ping had become into a makeshift farmers market during a harvest season, which not only helped the local populace sustain their living but also turned the dwelling into a kind of quasi-agricultural cooperative (Chananitithum Citation2017b).

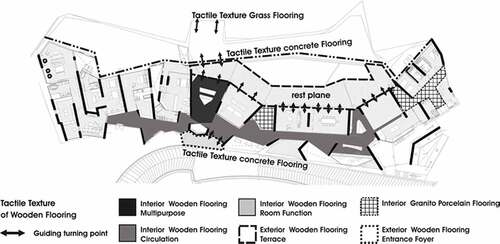

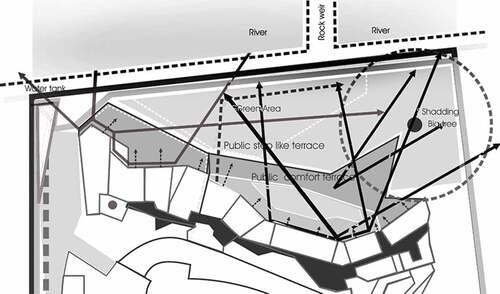

With the aforementioned contextual backgrounds taken into consideration, the forthcoming investigations demonstrated how the phenomenon of genius loci was manifested through the design parameters and elements of Baan Fai Rim Ping, of which procedures were portrayed by .

4.1. Spatial planning

It was evident that an amalgamation of positional awareness (proprioception), movements (kinesthesioception), and memories of previous moments (chronoception) played a crucial role for the layout of the house (). By having a courtyard occupying a focal point of the property, the house was oriented toward the river. Turning its length on the north–south axis, Baan Fai Rim Ping exposed the short side toward the sun and thus minimising accumulation of heat on the exterior surfaces of the building ().

Figure 5. Overall illustration on the south and east façades of the house. Source: Courtesy of Kriangkrai and Pornrawee Chananitithum.

With its length running in parallel to the waterway, the building sat further away from the road, resulting in a buffer zone that could effectively mitigate noise from passing by vehicles while maintaining a comfortable distance from the traffic to create privacy for the inhabitants. Apart from serving as a lawn to absorb rainwater, this open space could be used for organising outdoor activities as well (). The landscape and the courtyard were designed to appear organic and inherent to the site. As the trees grew and the house aged, the built and unbuilt would become more indistinguishable and graceful.

Moreover, dwelling on the northern side, the main living quarter was separated into two wings. The guest area – which could be separately closed down when not in use or converted to a relaxing area for the family members during the day – was on the southern side of the house. After entering through the main entrance, the volume of the building unfolded dynamically along the riverbank, resulting in a large area of intermediation between outdoor and indoor space (). Aside from facilitating a passive ventilation through the building, the transitional space enabled a large number of possibilities of utilisations to accommodate a mixture of scenarios provided by the surroundings (also see: Heritage by ASEAN Research Community, 2017).

As every living space received the value of a diverse landscape panorama, the building was light-filled and wrapped in glass with a panoramic view of the river. Terraces (or shan ruen in Thai) extended the interior space, providing an abundance of outdoor living area with varying exposures and sights. A screened porch furnished with an additional forum to experience the riverside scenery together with the sound of cascading water, overlooking a swimming pool situated on a series of large stepped terraces (). In a comparable fashion to traditional Thai residential structures, the terraces or shan ruen functioned as a kind of transitional space between the exterior and interior of the building. In this regard, Baan Fai Rim Ping Both employed terraces as a cultural element to welcome visitors in terms of a semi-public zone, where informal activities and gathering occurred. The aforementioned historical reference to shan ruen then acted as an integral part of the cultural dimension for the design strategy to promote a sense of place and feeling of belonging by means of bodily movements through space.

Similar to the typical Thai houses (), Baan Fai Rim Ping consisted of a group of separated functions that worked as a whole. One was tied to another by a sequence of transitional spaces–like terraces and decks – creating continuous flows of spatial movements from outside-in as well as inside-out, enabling people to appreciate the phenomenon of genius loci, which were framed by the incarnations of their bodily experiences via cultural practices and memories of shan ruen.

Figure 7. Analytical illustration on the transitional spaces at traditional Thai house and Baan Fai Rim Ping. Source: The authors.

Before proceeding further, it must be noted that the angular layout of the house stemmed from a desire to preserve a couple of existing large trees near the edge of the river. While providing shades and shadows, they were incorporated into the spatial arrangement of the courtyard in a traditional manner where a central patio was formed by surrounding shan ruens occupied by a standing tree in the middle ().

4.2. Topographic settings

The design of Baan Fai Rim Ping was commensurate with another aspect of traditional Thai houses: elevated floors. By constructing the entire building on stilts, historic Thai dwellings could prevent flood water from entering the living areas, whereas the space underneath them could be utilised for storage and resting during the hot daytime. This open space under the main bodies of those structures permitted movements of air to circulate through the houses in both vertical and horizontal directions ().

Figure 8. Analysis illustration on the space under traditional Thai house and Baan Fai Rim Ping. Source: The authors.

Informed by those architectural precedents, Baan Fai Rim Ping raised its primary living area three meters from the ground level to counter flooding from the nearby Ping river that happened almost every year. The architect also decided to install most of the building systems on the lower floor, which offered a more effective solution for their performance and maintenance. For instance, the access from the ground level made it easier to service the mechanical area without interfering with other spaces that were being used. Due to the fact that all services were routed to just one area without having to follow the architectural layout, a more pleasant living atmosphere could be attained, since there would be no building service inside the house.

In effect, the elevated floor of Baan Fai Rim Ping worked hand in hand with the terraces in cultivating the phenomenon of place. As the borderline of living space became critical to the question of separation, stepped terraces were introduced to create a borderline in order to distinguish the indoor living areas from the outdoor environment (). In this respect, an observation could be made that the terraces exemplified a landscape reaction in differentiating the constructed lines of the buildings from the natural boundaries to the surrounding ground. At the same time, they assumed the role of a flooding protection structure as well.

By alluding to a theoretical foundation established by Straus (Citation1966, 11), it could be argued that the haptic experiences at this riverside abode stemmed from unselfconscious knowledge by moving into and across space. Via their haptic cognisance of positional awareness, movements, memories of previous moments, touch, the dwellers developed a conception about the identity of the house – which essentially was a reflection of their self-image – through their sensory receptions and memories. Strengthened by their emotional connections with architecture and surrounding, the outcome was a cyclical relationship among sensation, perception, feeling, thought, and action (Metheny Citation1975, 96).

4.3. functional arrangements, spatial configurations, and formal compositions

As illustrated by (), exercising haptic senses was quintessential to experience the phenomenon of genius loci from the design of Baan Fai Rim Ping.

Figure 9. Analytical illustration on multiple vantage points of scenery toward the river. Source: The authors.

The said criterion constituted the underlying principle in devising the spatial organisations of the house, resulting in a sweeping and fluid profile of multiple perspective points as exhibited by its zigzagging roof and non-perpendicular walls ().

In addition to a figurative allusion to the mountain range behind the house in materialising a sense of place, the unusual look of the roof served a pragmatic aim as well. As a matter of fact, the zigzagging shape was intended to dissipate rain water, preventing it from accumulating on a certain spot, which might cause a leaking problem into the building ().

Taken as a whole, the fragmented formal composition of Baan Fai Rim Ping () sheltered a wide range of utilitarian requirements, each of which enabled the phenomenon of genius loci to unfold simultaneously – via a combination of the sensory receptions of ophthalmoception, audioception, chronoception, thermoception, kinesthesioception, and proprioception – as explained below.

First – via the awareness on sight and hearing – the living area took a full advantage of the panoramic view and sounds of the Ping, naturally generating a homely atmosphere as an interpretation of Thai culture unique to the needs and characteristics of the Chananitithum family. Located at the centre of the house with a height of four meters, it served both as the main circulation and transitional space between the outdoor and indoor environment of the house.

Second, by arranging bedrooms into an L-shaped form and placing them north of the living areas, the haptic senses of the dwellers – namely, the ophthalmoception and audioception – were enhanced through a 270degree field of visual and audible ranges. This, in return, advances the reception and internalisation of the phenomenon of place for the Chananitithum family in a similar manner to the living area. The bedrooms also benefitted from the thermoception awareness provided by natural cross-ventilation from the living area, reminiscent of local residences along the Ping river.

Third, with an easy access to the pool and terrace, the family room and dining area could host a multitude of activities, including a private party, formal dinner, or informal meeting for a small number of guests in the evening. A mixture of mouth-watering food and entertaining space – which became more memorable by means of bodily movements on a large terrace down to the river – was complementary to the phenomenon of genius loci, strengthened by the olfacoception (smell), gustaoception (taste), and tactioception (touch) cognisance from savouring a home-made cuisine.

Fourth, similar to the bedrooms, the guest quarter and sauna were laid out in terms of an L-shaped plan, allowing more than 180 degree-field of visual and audible ranges for the visitors to enjoy the haptic sense of sight and hearing of the overflowing water in the river. Occupying the south end of the house, these rooms were separated from the family area, thus striking a balance between generating the feeling of placeness and belonging versus maintaining security and privacy for the Chananitithum family.

4.4. Construction materials and structural system

Although the choice of construction materials and structural system was born out of tectonic and practical concerns, it became another crucial element in fostering the phenomenon of genius loci. In fact, the use of reinforced concrete largely stemmed from the architect’s long practice and advocation of appropriate technology, which: (1) existed locally; (2) emphasised on human progress rather than tectonic advancement; (3) minimised damage to the environment; (4) drew people’s collaboration; and (5) contributed to community development (Lee and Na Citation2019, 43–44).

Unlike traditional Thai houses, Baan Fai Rim Ping did not resort to a post-and-lintel system to carry the load of the elevated building, but employed a series of load-bearing walls made of reinforced concrete as its main structural components. While contributing less flexibility to spatial arrangements, it was generally acknowledged that a building constructed with load-bearing walls–which was substantially stiffer than those using post-and-lintel or framed structures–would suffer less lateral displacement when subjected to the same ground motion intensity (Ching and Adams Citation2001, 2.20–2.21, 5.18–5.19). By carrying their own weight, the reinforced concrete load-bearing walls at Baan Fai Rim Ping were utilised both as interior partitions and exterior enclosures. Without any member of the structural elements protruding on their surface, the walls were carefully casted on site – using removable steel forms – and became aesthetically pleasing in their own right ().

The utilisation of those load-bearing walls was made possible by reinforced concrete, which was not limited to vertical load-bearing elements like walls and columns, but included other vital components, namely floor and roof as well. Separated into several small areas and furnished with corrugated metal sheets to shed heavy rain more efficiently, the complicated roof of Baan Fai Rim Ping provided additional strength and durability to the entire structure. Equipped with large overhangs for optimal shading, the zigzagging shape of the roof thus united the dwelling with the undulating nature of the topography ().

Overall, not only did the use of reinforced concrete as structural material bestow a uniformed appearance of the house but also result in its atmospheric comfort by acting as a thermal insulation to shield the heat from tropical sunlight from entering the building. The cool, grey concrete for walls and ceilings generated an intense homogeneity in the architecture of Baan Fai Rim Ping. In contrast to well-known Brutalist architecture of the 20thcentury–where concrete surfaces: (1) were bush-hammered as demonstrated by the Everson Museum by Ieoh Ming Pei; or (2) featured stippled effects of shotcrete or corduroy surfaces as evident from the works of Paul Rudolph such as the Art and Architecture Building at Yale University–the smooth surfaces of Baan Fai Rim Ping produced a distinctive sheen that encompassed subtle reflections of light.

Furthermore, the unfurnished surfaces of the walls, floors, and ceilings revealed that the architect invested the concrete with a shininess that implied lightness rather than weight, giving an impression of gently shimmering as if it was wet. Consequently, concrete did not solely determine the atmosphere in the spatiality of Baan Fai Rim Ping, but referred to another element: light.

As exhibited by the interior of the house, the walls became abstract, approaching an ultimate limit of space, whereas large windows or slits were quietly reflected through enclosures. Located between walls and ceiling, the elegant slits created a poetic rhythm of light during the course of the day. Chiefly restrained as a channel for diffuse daylight, the gaps disrupted the concrete surfaces and separated vertical from horizontal, intensifying the spatial depth. While a moment of crescendo was short but intense, it emerged when the rays of sunlight ran very close along the walls and presented a layer of striking shadows. Thanks to these phenomena, the building had achieved its stylistic independence from both ethos of: (1) Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus in promulgating bright white cubes that were synonymous with modern architecture; and (2) Frank Gehry in perceiving architecture as visual objects that resulted in the so-called “Bilbao effects” of curvilinear forms.

In essence, the said interplays of concrete and light were an integral part of the overall mechanism to construct what Seamon (Citation1980: pp. 157–58) called a “strong sense of place” together with its meanings for the Chananitithum family. Via their bodily movements through the exterior and interior spaces of the house, the walls, floors, and ceilings collectively formed the physical boundaries whereby the acts of dwelling took place and were immortalised by their memories when those events occurred. This process happened in two folds.

First, by alluding to the haptic cognisance of time (chronoception)–thus indicating the amount and types of light–the corporeal encounters of the inhabitants were linked with their psychological recognition in terms of space–time relations.

Second, by connecting the positions of the psyches with the physiques of the occupants, the perception of space at Baan Fai Rim Ping therefore incorporated a series of complex bodily experiences beyond the Aristotelian senses, but involved others, such as positional awareness (proprioception), balance (equilibrioception), movements (kinesthesioception), depth of field (ophthalmoception), and memories of previous moments (chronoception).

In brief, the abovementioned haptic receptions of interactions were characterised by the relationships between wall apertures and enclosures in the design of Baan Fai Rim Ping, operating through binaries of light versus darkness, transparency versus opacity, and solids versus voids. Consisting of tempered glass and aluminium frames in combination with wooden mullions and louvers, triangular shapes in window openings geometrically echoed the zigzagging roofline and serpentiform spatial organisation of the house ().

4.5. Finishing materials

Due to a long historical link with the timber trade of Kamphaeng Phet, teak played a significant role in the psychological recognition of the local people on their self-identity. Hence, it was unsurprising to discover that the popularity for teakwood had endured in the area in spite of the fact that the forest industry had largely disappeared from the entire northern region of Thailand in the present day (Gajaseni and Jordan Citation1990, 114).

In addition to the spatial arrangements of Baan Fai Rim Ping, the use of teakwood for the floors and furniture inside the building was another obvious attribute in its design of that reflected the life and ways of living of the inhabitants. Despite being recognised as one of the leading entrepreneurs in agroindustry in Kamphaeng Phet province nowadays, Kriangkrai was a descendant of Chinese immigrants, who once owned a lumber business in the nearby community of Nakhorn Chum. For that reason, hardwoods – teak in particular – had a long association with the background and identity of the Chananitithum family. So, it is unsurprising to see that Kriangkrai was the person who selected teak planks from suppliers, and then assigned the location for each piece to be utilised in the house.

On that account, the phenomenon of genius loci at Baan Fai Rim Ping was cultivated by the intimated employment of teakwood for the floors of the living areas and family living quarters (), coupled with the furniture in those rooms, which occurred through a materialistic reinterpretation of traditional Thai architecture. As the residents and visitors alike removed their shoes – walking barefoot, as well as sitting, lounging, and laying down on the floors, chairs, and benches, as customarily practiced in many Asian cultures – they explored the teak texture with their bodies. Such a hands-on experience provided a genuine chance to exercise the olfacoception and thermoception, or even nociception (pain), cognisance simultaneously, owing to different chemical odours evaporating from the finishing materials – e.g., wax, lacquer, oil, and varnish – together with the thermodynamic quality of teakwood itself.

4.6. Proximity to the UNESCO Site and its implications

Due to proximity to the UNESCO World Heritage Site (), many references to the cultural heritages of Kamphaeng Phet were made in the design of Baan Fai Rim Ping. Operating in unison, these allusions supplied an interpretive discourse to express a sense of historical continuity that generated the quality of placeness, constituting a fil rouge in manifesting the concept of genius loci.

Aside from the teakwood floors and furniture in the living areas and family living quarters, laterite presented another example of thoughtful applications for materiality that could be noticed from this waterfront residence. Widely abundant in Southeast Asia, laterite – a clayey soil formed by the decomposition of the underlying rocks that became hardened when dry – was cut into brick-like shapes to erect temples and shrines, long before the Khmers constructed Angkor Wat in the 12th century. Likewise, historic buildings in Kamphaeng Phet historical park commonly utilised laterite as one of the principal structural materials. Because of their high iron oxide content, nearly all types of laterites were of rusty-red coloration, resulting in a distinctive reddish appearance (Helgren and Butzer Citation1977, 431).

As is evident from the façades of Baan Fai Rim Ping, both the exterior and some interior walls were painted in rusty-red colour (), suggesting a connection to the monumental structures in Kamphaeng Phet historical park. To manifest this materialistic association, the house was furnished with a reddish water tower situated on a laterite plinth standing at the north-eastern corner of the property. With its piercing silhouette, the tower acted as a community landmark exhibiting the location of the house in relation to those of other historic structures in Kamphaeng Phet city. Employing laterite as a prominent construction material, they were built when the city of Kamphaeng Phet served as a strategic military outpost for Sukhothai Kingdom (1238–1438) ().

Such material allusions could be noticed from landscape design as well. In the yard, laterite bricks were employed in a more tectonically sound manner to create masonry walls and pavements for walkways, of which rugged surfaces could be experienced through the haptic senses of tactioception and nociception (). They were accompanied by the awareness of sight and smell from a number of fragrant flowering plants – many of which were narrated by local folktales and legends – such as night-blooming jasmine, frangipani, bullet wood, and white champak. As a consequence, on the one hand, the haptic cognisance of ophthalmoception, olfacoception, and tactioception of the inhabitants could be indulged simultaneously during a leisurely stroll around the property in the morning and afternoon. On the other hand, when the flowers blossomed, a seasonal breeze would gently carry their pleasant aromas into the house, especially in the evening.

5. Conclusion

In the course of proposing a view on the architectural profession, Gans (Citation1977), insightfully wrote that:

“A major distinguishing characteristic of high-culture architecture has been its self-conscious attempt to make philosophical and symbolic statements, but often this is overdone … Architects are generally not accomplished philosophers in the first place; the statements they want to make are often half-baked or clichéd even when the architecture itself is good” (p. 27).

Although Gan’s critical reading might hold true for several renowned architects and their seminal works, the preceding analytical discussions revealed that the design of Baan Fai Rim Ping along with its philosophical foundations and theoretical framework were intellectually interwoven, therefore becoming complementary to and uniting with each other.

In any case, it was necessary to point out that within the field of architectural theory, one of the important debates was the fate of phenomenology in architecture. Regardless of their disagreements, many critics concurred that part of the trouble with architectural phenomenology was that it “still voices a metaphysics of presence by assuming the world is constituted by observing subjects and architectural objects” (Norwood Citation2011, 7). However, for some, the said problem should not account for the ground that led to a dismissal of phenomenology. In their opinions, what was preferable was “careful, critical self-reflection on phenomenology as an architectural method” (Norwood Citation2011, 7).

On that basis, Baan Fai Rim Ping encapsulated an emerging design approach, which explored explicitly in reference to the messy and complicated existence of dwellings and dwellers in the complex dynamism of the 21st-century Thailand. Notwithstanding its highly expressive forms–notably for the zigzagging reinforced concrete roof together with spatial configuration by means of non-perpendicular walls – the building embodied the senses of tranquillity and historical continuity, as well as a feeling of placeness and belonging ().

In other words, the phenomenon of genius loci could be witnessed from Baan Fai Rim Ping, of which design was neither conventional nor stereotypical, but unorthodox and innovative. As demonstrated by , by neutering the haptic receptions of the inhabitants – buttressed by their emotional connections with architectural precedents, the surrounding landscape, and Kamphaeng Phet historical park () – the quality of placeness was developed and implemented via the design parameters of Baan Fai Rim Ping. As illustrated by , they were brought into being by the spatiality and materiality of the house in terms of its architectural elements, operating through a triad of associations.

Table 1. Types of haptic senses employed in each design parameters of Baan Fai Rim Ping in cultivating genius loci. Source: The authors.

In a final analysis, although the creation of Ban Fai Rim Ping seemed to be in a similar vein as those of the so-called critical regionalism architecture whereby traditional elements and principles were amalgamated with vocabularies of modernism without losing a profound respect for local sites and contexts as epitomised by works of Tadao Ando – a meaningful understanding on this riverside residence went far beyond a stylistic classification. Rather, the building should be perceived as a focus of great care, involvement, and constructive relationship with the domestic, social, and cultural contexts of the Chananitithum family.

For that reason, it became obvious that Ban Fai Rim Ping represented a material embodiment for the Chananitithum’s mode of dwelling, centring on their way of being at home that was fundamental for the phenomenon of genius loci. The sequence of transitional spaces at the stepped terrace–plus the cool, grey, shining, and homogeneous reinforced concrete surfaces–in conjunction with the polished teak floor and furniture–engendered powerful simplicity and tranquillity via the haptic awareness of the occupants, despite the overall complex and fragmented geometry of the building. The aforementioned observations drew to a conclusion that the house exemplified how one could be at home in a complex dynamism of postmodern life, being able to retain the core values of his/her cultural heritages while engaging with the constantly evolving world.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our collective gratitude to Kriangkrai and Pornrawee Chananitithum, the owners of Baan Fai Rim Ping, for their gracious supports and permissions to publish both textual and illustrative materials on the house. Our sincere appreciations also went to the architect of the riverfront residence, Surasak Kangkhao, and his assistant, Kowit Kwansrisut, for their generous helps and accommodations that greatly benefited this research in various stages, particularly during the fieldworks in Kamphaeng Phet province. In addition, many constructive criticisms and perceptive comments on the manuscript were kindly provided by anonymous reviewers from Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering. While the insights were theirs, any error remained our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Koompong Noobanjong

Koompong Noobanjong currently serves as a professor of architecture. With an academic background in architectural history, theories, and criticism, he has published several research articles and books on the politics of representations in architecture and urban space, as well as on critical studies of the built environment. His scholarly interests have recently expanded to architectural and design education

Chaturong Louhapensang

Chaturong Louhapensang is an associate professor in industrial design, teaching at the undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral levels. His scholarly interests cover a wide range of research topics, varying from instructional design, educational technology, creative economy, architecture, arts and crafts, to sustainable development, urban geography, as well as ethnographical, pedagogical, and cultural studies.

References

- Askland, H., R. Awad, J. Chambers, and M. Chapman. 2014. “Anthropological Quests in Architecture: Pursuing the Human Subject.” International Journal of Architectural Research 8 (3): 284–295.

- Bachelard, G. 1969. The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Baldwin, M. 2012. “Participatory Action Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Work, edited by M. Grey, J. Midgley, and S. A. Webb. London: Sage Publications. pp. 467–481.

- Bannon, L. J., and P. Ehn. 2013. “Design: Design Matters in Participatory Design.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design, edited by J. Simonsen and T. Robertson. London: Routledge. pp. 37–63.

- Benjamin, D. 1995. “Afterword.” In The Home: Words, Interpretations, Meanings and Environments. Ethnoscapes: Current Challenges in the Environmental Social Sciences, edited by D. Benjamin, D. Stea, and E. Arén. Avebury: Aldershot. pp. 293–307.

- Campbell, R. 2007. “Experiencing Architecture with Seven Senses, Not One.” Architectural Record 195 (11): 65–66.

- Chananitithum, K. 2017a. “Personal Interview by C.” Louhapensang, 6 July 2017.

- Chananitithum, K. 2017b. “Personal Interview by C.” Louhapensang, 19 December 2017.

- Ching, F. D. K., and C. Adams. 2001. Building Construction Illustrated. New York: Wiley.

- Computer Professionals for Social Responsibilities (CPSR). (2005). “Participatory Design.” Issues. http://cpsr.org/issues/pd/

- Cousins, B. J., and E. Whitmore. 1998. “Framing Participatory Evaluation.” New Directions for Evaluation 80 (80): 5–23. doi:10.1002/ev.1114.

- Donlyn, L., and C. W. Moore. 1994. Chambers for a Memory Palace. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Foulke, E. 1983. “Spatial Ability and the Limitations of Perceptual Systems.” In Spatial Orientation: Theory, Research and Application, edited by H. L. Pick and L. Acredolo. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 125–141.

- Gajaseni, J., and C. F. Jordan. 1990. “Decline of Teak Yield in Northern Thailand: Effects of Selective Logging on Forest Structure.” Biotropica 22 (2): 114–118. doi:10.2307/2388402.

- Gans, H. J. 1977. “Toward A Human Architecture: A Sociologist’s View of the Profession.” Journal of Architectural Education 31 (2): 26–31. doi:10.1080/10464883.1977.10758597.

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books.

- Heidegger, M. 1971. Poetry, Language, Thought. New York: Harper Colophon Books.

- Helgren, D. M., and K. W. Butzer. 1977. “Paleosols of the Southern Cape Coast, South Africa: Implications for Laterite Definition, Genesis, and Age.” Geographical Review 67 (4): 430–445. doi:10.2307/213626.

- Heritage by ASEAN Research Community (HARC). (2017). “Ban Fai Rim Ping.” Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n7zAqE7A1Ps&app=desktop#

- Herssens, J., and A. Heylighen (2007). “Haptic Architecture Becomes Architectural Hap.” Paper presented at the Annual Congress of the Nordic Ergonomic Society (NES). Lÿsekil, Sweden.

- Herssens, J., and A. Heylighen (2012). “Haptic Design Research: A Blind Sense of Space.” Paper presented at the ARCC/EAAE 2010 International Conference on Architectural Research. Washington D.C., U.S.A.

- Husserl, E. 1958. Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. New York: Macmillan.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). (2010). “ISO 9241-210: 2010 Ergonomics of Human-system Interaction–part 210: Human-centred Design for Interactive Systems.” Standard catalogue: 13.180 ERGONOMICS. Retrieved from https://www.iso.org/standard/52075.html

- Jivén, G., and P. J. Larkham. 2003. “Sense of Place, Authenticity and Character: A Commentary.” Journal of Urban Design 8 (1): 67–81. doi:10.1080/1357480032000064773.

- Lee, B., and I. S. Na. 2019. “A Case Study of A Community Center Project Based on Appropriate Technology as A Community Capacity Building of Underdeveloped Country.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 18 (2): 43–48. doi:10.1080/13467581.2019.1595628.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Magee, G. A. 2010. The Hegel Dictionary. London: A & C Black.

- Mahabadi, S. M., Z. Hossein, and M. Hamid. 2014. “Participatory Design; A New Approach to Regenerate the Public Space.” International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development 4 (4): 15–22. Retrieved from: https://ijaud.srbiau.ac.ir/article_8339_47703dce2ed5f9ebcac51ce275b56d74.pdf

- Merleau-Ponty, M. 1978. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Metheny, E. 1975. Moving and Knowing in Sport, Dance, Physical Education: A Collection of Speeches by Eleanor Metheny. Los Angeles: Peek Publications.

- Mugerauer, R. 1994. Interpretations on Behalf of Places: Environmental Displacements and Alternative Responses. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Newman, M., and P. Thomas. 2008. “Student Participation in School Design: One School’s Approach to Student Engagement in the BSF Process.” CoDesign 4 (4): 237–251. doi:10.1080/15710880802524938.

- Norberg-schulz, C. 1980. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. New York: Rizzoli.

- Norwood, B. E. 2011. “Architecture’s Historical Turn: Phenomenology and the Rise of the Postmodern by Jorge Otero-Pailos.” Harvard Design Magazine 33: 1–7.

- O’Neill, M. E. 2001. “Corporeal Experience: A Haptic Way of Knowing.” Journal of Architectural Education 55 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1162/104648801753168765.

- Pallasmaa, J. 2005a. “Architecture and the Human Condition.” In Another Eyesight, Multisensory Design in Context, edited by J. Ionides and P. Howell. Ludlow: Dog Rose Trust. p. 411.

- Pallasmaa, J. 2005b. Encounters, Ed. P. MacKeith. Helsinki: Rakennustieto Oy.

- Passe, U. 2009. “Designing Sensual Spaces.” Design Principles and Practices 3 (5): 31–46. doi:10.18848/1833-1874/CGP/v03i05/37756.

- Pavlides, E., and C. Cranz. 2012. “Ethnographic Methods in Support of Architectural Practice.” In Enhancing Building and Environmental Performance, edited by S. Mallory-Hill, W. Preiser, and C. Watson. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 299–311.

- Pikulsri, B. (2018). “Modern Thai Loft on a Two-hectare Estate (In Thai).” Homedeedee, 27 May 2018. Retrieved from h ttps:// homedeedee.c om/thai-modern-loft-บ้านไทย-สไตล์โมเดิร์น

- Rasmussen, S. E. 1964. Experiencing Architecture. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury, Eds. 2008. The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ryhl, C. 2009. “Architecture for the Senses.” In Inclusive Buildings, Products and Services, edited by T. Vavik. Trondheim: Tapir Academic Press. pp. 104–127.

- Sanders, L. 2008. “An Evolving Map of Design Practice and Design Research.” ACM Interactions Magazine XV (6): 1–7. doi:10.1145/1409040.1409043.

- Sanders, L., and P. J. Stappers. 2014. “From Designing to Co-designing to Collective Dreaming.” Interactions 21 (6): 24–33. doi:10.1145/2670616.

- Schütz, A. 1979. Fenomenologia E Relações Sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar.

- Seamon, D. 1980. “Body-subject, Time-space Routines, and Place Ballets.” In The Human Experience of Space and Place, edited by A. Buttimer and D. Seamon. London: Croom Helm. pp. 148–165.

- Sidky, H. 2004. Perspectives on Culture: A Critical Introduction to Theory in Cultural Anthropology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Sorabji, R. 1971. “Aristotle on Demarcating the Five Senses.” The Philosophical Review 80 (1): 55–79. doi:10.2307/2184311.

- Stefanovic, I. L. 1998. “Phenomenological Encounters with Place: Cavtat to Square One.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 18 (1): 31–44. doi:10.1006/jevp.1998.0062.

- Straus, E. W. 1966.“The Forms of Spatiality”.Selected Papers of Erwin W. Straus: Phenomenological Psychology,edited byE. Eng,Trans. New York:Basic Books. pp. 3–37.

- Suri, J. F. 2011. “Poetic Observation: What Designers Make of What They.” In Design Anthropology. Object Culture in the 21st Century, edited by A. J. Clarke. Vienna & New York: Springer, pp. 16–32.

- United States of America, National Park Service. (2021). What is ethnographic research? Park ethnography program. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/ethnography/aah/aaheritage/ercb.htm

- Van der Velden, M., and C. Mörtberg. 2015. “Participatory Design and Design for Values.” In Handbook of Ethics, Values, and Technological Design, edited by J. van den Hoven, P. P. Vermaas, and I. van de Poel. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 41–66.doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6970-0_33.