ABSTRACT

Contractor’s consummate performance behavior (CPB) is the key to achieve consummate performance. However, the mechanism of reasonable contract risk allocation incentives for Contractor’s CPB is unknown. The objective of this study is to reveal the effective ways to encourage contractor’s CPB by contract risk allocation based on the contract reference point theory and selecting the contractor’s trust perception and fair perception as mediating variables. Through an empirical analysis of the valid questionnaires collected, the results are as follows: (1) Although the economic benefits generated by reasonable contract risk allocation can induce contractor’s fair perception, fair perception has no mediating effect in the relationship between contract risk allocation and contractor’s CPB; (2) The cooperative value generated by reasonable contract risk allocation can induce contractor’s trust perception, and trust perception plays a part mediating role between contract risk allocation and contractor’s CPB. The findings also provide insights into how risk allocation facilitates contractor’s CPB in the construction industry.

1. Introduction

As one of the most important subjects of construction project implementation, the contractor’s performance behavior is very important to the realization of project performance (Memon et al. Citation2021; Li, Yin, and Zhang Citation2020; Skitmore et al. Citation2020). The contract reference point theory proposed by Hart and Moore divides project performance into perfunctory performance (PP) and consummate performance (CP) and points out that CP is the basis of project benefit sharing (Hart and Moore Citation2008). On this basis, scholars such as Liu et al. (Liu et al. Citation2019) and Yan et al. (Ling, Zhixiu, and Jiaojiao Citation2018) further divide the performance behaviors into perfunctory performance behavior, consummate performance behavior (CPB), and opportunistic behavior according to the different performance efficiency of contractor, and point out that CPB plays a key role in the smooth implementation of project and even the improvement of project performance, which is the core concern of client. CPB exists objectively, but it is difficult to be confirmed by a third party (Hart and Moore Citation2008), which cannot be enforced by law, and must be based on the voluntary provision of partners (Williamson Citation1975). Yan et al. reveal the driving factors and formation mechanism of contractor’s CPB from the perspectives of behavior attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control (Ling, Liang, and Yan Citation2020), and establish the theoretical framework of contractor’s CPB from the perspective of contractor’s internal behavior (Yan and Guo Citation2020). However, there is no research on how to induce contractors to perform CPB from the perspective of clients.

In construction projects, a lot of scholars believe that a reasonable contract risk allocation scheme is the main incentive mechanism to induce contractor’s cooperative behavior and improve project performance (Memon et al. Citation2021; Zhang et al. Citation2016; Nguyen, Rameezdeen, and Chileshe et al. Citation2021; Peckiene, Komarovska, and Ustinovicius Citation2013). However, some studies have shown that reasonable risk allocation does not necessarily bring positive behaviors of contractors. On the contrary, reasonable risk allocation clauses designed in contract may be used by contractors, resulting in a large number of opportunistic behaviors and reducing project performance (Lu et al. Citation2015; Zhichao et al. Citation2018). It can be seen that a reasonable risk allocation scheme designed by the client in the contract does not necessarily motivate the contractor to perform CPB, but also needs to consider the intermediary conditions that can trigger contractor’s CPB. Some studies have shown that behaviors of contracting parties are not entirely interest-oriented but also influenced by social preference (Zhou et al. Citation2012). The signals of trust and fairness conveyed by the reasonable risk allocation mechanism itself will stimulate the social preference of contractor, and thus induce contractor’s positive behaviors (Kraft, Valdés, and Zheng Citation2017).

In summary, there is no clear theoretical model to reveal the relationship between risk allocation and CPB. To fill this gap, this study aims to explore the mechanism that risk allocation triggers contractor’s CPB, based on a formal theoretical linkage model and a statistical empirical investigation. To further explore how and when this mechanism occurs, trust and fair perception are introduced as mediating variables, which is helpful to better understand the potential mechanism of risk allocation inducing contractor’s CPB. The study collected a total of 164 valid questionnaires by issuing questionnaires. The reliability and validity of the collected data have been tested by SPSS Statistics21.0, and then the hypotheses were tested by Smart PLS3.0 of SEM-PLS. The research results will provide new insights for the contract reference point theory and provide theoretical basis for designing contract clauses that effectively encourage contractor’s CPB.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the literature review. Section 3 presents the conceptual framework and hypothesis development. Section 4 presents the method. Section 5 reports the results and discussion. It ends up with implications for theory and practice as well as concluding remarks. The overall scope and procedure of this study is shown in .

2. Literature review

2.1. Contract risk allocation

Risk allocation is the key issue of construction project contract governance, and it is also a hot research topic in academic and practical circles (Zhichao et al. Citation2018; Tsai and Yang Citation2009; Cha and Shin Citation2011; Zhang et al. Citation2021). Reasonable risk allocation refers to the allocation of risks to the party who voluntarily undertakes and has the ability to control at an appropriate time and getting certain economic compensation for risk-bearing (Barnes Citation1983; Koh, Ahmed, and Kayis et al. Citation2007). Based on incomplete contract theory, Yin et al. construct a risk allocation framework for the contracting stage of construction projects, suggesting that the measurement dimensions of initial risk allocation include completeness, enforceability, and incentive (Yilin, Dong, and Yao Citation2015). According to the sources, Zhang et al. put the project risks divide into environmental risks and behavioral risks. The reasonable risks allocation should be that the behavior risks are borne by the subject of the behavior, and the environmental risks are shared by both contracting parties (Zhang et al. Citation2016). Based on the contract reference point theory, Yan et al. have confirmed that the contract risk allocation mechanism can be further subdivided into two dimensions: risk liability and risk compensation (Yan Ling, Liu Liu, Zeng Cheng Citation2019). The core of risk liability lies in clarifying the situation or result of the risk undertaken by both parties; Risk compensation emphasizes that the contract price signed by both parties is fair compared with the risk that contractor should bear.

2.2. Contractor’s Consummate Performance Behavior (CPB)

Previous studies on contractor’s behavior mainly focus on two aspects. One is based on transaction cost theory, focusing on restraining opportunistic behavior and promoting cooperative behavior of contractors (Lu et al. Citation2015; Ahimbisibwe Citation2014). In this perspective, researchers pay more attention to contractor’s in-role behavior but are less concerned about the extra-role behavior that cannot be written in the contract and has a positive effect on construction project (Memon et al. Citation2021; Li et al. Citation2019). The second perspective focuses on the organizational citizenship behavior of contractors based on organizational behavior theory. Contractor’s organizational citizenship behavior has a positive effect on construction projects (Lim and Loosemore Citation2017; Wang et al. Citation2018), but belonging to individual level, not organizational level.

Different from the two aspects above, based on the contract reference point theory, the initial contract concluded by the construction project participants provides a reference point for the parties’ trading relationship through the feelings of entitlement. Parties might choose corresponding performance behavior based on their sense of entitlement (Hart and Moore Citation2008; Fehr, Hart, and Zehnder Citation2011). The choice of contractor’s behavior strategy is affected by the contract reference point. That is, when the contractor feels that he has obtained the rights and interests stipulated in the contract, he will perform CPB. Otherwise, contractors are only willing to implement contracts according to the minimum standards, or even retaliatory opportunism (Ling, Liang, and Yan Citation2020). With reference to the definition of extra-role behavior and organizational citizenship behavior, this study defines contractor’s CPB as the inter-organizational performance behavior (Wang et al. Citation2018) that contractor is willing to make extra efforts to implement the project in the spirit of contract, which is characterized by voluntary, initiative, and altruism (Yan and Guo Citation2020).

2.3. Trust perception

Trust refers to an individual’s willingness to believe that the other party will be mutually beneficial in certain risk activities. Trust originates from communication and is an embodiment of interpersonal relationships (Qin, Hua, and Tang Citation2010). It is also an effective tool for managing organizational relationships (Wu et al. Citation2020). Trust has reciprocity, which is a kind of interactive relationship. It is the motivated altruistic behavior that people take the initiative to others based on the expectation of reciprocal positive reciprocal behavior of others. In other words, the expectation of trusting others is the positive reciprocal behavior of winning others’ subsequent repayment (Chan and Au Citation2008). In this study, trust perception refers to contractor’s perception of the trust and goodwill signal transmitted by client’s reasonable risk allocation. Some studies have proved that reasonable risk allocation is a necessary condition for contractors to generate trust perception (Pei, Guo-jie, and Yin-li Citation2015).

2.4. Fair perception

Fairness means that ”a decision, outcome, or procedure is both balanced and correct” (Pan et al. Citation2017). As an academic term, fair perception focuses on the fair feelings of individuals with fair preference for giving and feedback (Liu et al. Citation2012). The formation of contractor’s fair preference depends on the comparison between the results obtained and its contract reference points (Yan Ling, Liu Liu, Zeng Cheng Citation2019). The academic research on fair perception mainly focuses on supply chain, income distribution, and other fields and their measures from three dimensions: distribution fairness, procedural fairness, and interactive fairness (Luo Citation2007; Baird, Su, and Nuhu Citation2021). Based on the characteristics of construction projects, Du et al. divide contractor’s fair perception into two dimensions: distribution fairness and procedural fairness (Yaling, Huiling, and Hong Citation2016).

3. Conceptual framework and hypotheses development

3.1. Contract risk allocation and contractor’s CPB

Risk allocation mechanism is the most important mechanism in contract governance. A reasonable risk allocation mechanism should not only emphasize reasonable risk liability, that is, too many risks can not be transferred to contractor, but also pay attention to the rationality of risk compensation, that is, contractor can get matching compensation for the risks he bears (Yan Ling, Liu Liu, Zeng Cheng Citation2019). In fact, the two dimensions of risk allocation not only reflect client’s economic incentives to contractor but also reflect client’s consideration of interests of contractor and his friendly tendency to contractor (Meng Citation2012). There is no doubt that risk allocation is closely related to contractor’s income. Risk allocation reflecting efficiency and fairness can induce contractors to respond positively to the expectation of client, taking reciprocal CPB (Yilin, Dong, and Yao Citation2015; Klotz and Bolino Citation2013). Branconi points out that a reasonable risk allocation mechanism can coordinate the relevant relations among all parties involved in a project and guides them to make decisions in good faith (Von Branconi and Loch Citation2004). On the contrary, if a client adopts an unreasonable risk allocation, the risks faced by the contractor will exceed his scope of commitment, so that the contractor may choose opportunistic behaviors, such as lowering the quality of the project or claiming for a higher price (Pang et al. Citation2015). Thus the following are hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Risk allocation is positively related to contractor’s CPB.

Hypothesis 1a (H1a): The more reasonable the risk liability, the more likely contractor will engage in CPB.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b): The more reasonable the risk compensation, the more likely contractor will engage in CPB.

3.2. The mediating role of contractor’s trust perception

Contractor’s trust perception is a kind of expectation or evaluation of client’s ability to provide beneficial behaviors based on client’s positive intentions and wishes under the uncertainty and risks (Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman Citation1995). If one party takes the risk, the other party will regard behaviors as a kind of trust and make a positive return (Lester and Brower Citation2003). Reasonable risk allocation is the result of modification and re-modification of risk allocation strategy formed by client on the basis of mutual benefit and win–win consideration (Lau and Lam Citation2008), which conveys the signal and willingness of client to trust contractor and actively cooperate (Zhichao et al. Citation2018). Reasonable risk liability and compensation clauses in the contract grant the contractor more control over the project and stimulate his trust perception in the client (Seibert, Silver, and Randolph Citation2004). Furthermore, contractors will have a sense of respect, deeply awaken his awareness of trust in clients, and devote more energy and capital to maintain the cooperative relationship with client (Pierce and Gardner Citation2004). Thus, the following are hypothesized:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Reasonable risk allocation can enhance contractor’s trust perception

Hypothesis 2a (H2a): The more reasonable the risk liability, the stronger contractor’s trust perception.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b): The more reasonable the risk compensation, the stronger contractor’s trust perception.

The economic incentive of risk allocation will bring better performance from those who are motivated, which is widely accepted in economic reasoning. However, the difference in understanding of reasonable risk allocation between client and contractor often leads to partial failure of the incentive function for reasonable risk allocation. Therefore, if a client wants to motivate contractor’s CPB, it needs to promote contractor’s recognition of a reasonable risk allocation scheme and perceive the positive signal sent by the client (Abednego and Ogunlana Citation2006). Contracts will change contractor’s cognitive style, and contractor’s behavior according to the terms in contract may be a comprehensive response to risk liability and compensation. For contractors, reasonable risk allocation bears a positive signal that clients trust contractors (Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman Citation1995). A large number of construction practices show that when client chooses a reasonable contract risk allocation scheme, contractor feels the goodwill and trust signal of client, thinks that active performance can get due reward and compensation, and actively performs obligations under trust perception (Zhichao et al. Citation2018), and even adopts organizational citizenship behavior that is more beneficial to client (Serva, Fuller, and Mayer Citation2010). It can be inferred that the trust interaction between contractor and client is probably the key mediating variable between risk allocation of client and contractor’s CPB. According to this, combining with hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2, the following hypothesises are proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Contractor’s trust perception plays a mediating role between risk allocation and contractor’s CPB.

Hypothesis a (H3a): Contractor’s trust perception plays a mediating role between risk liability and contractor’s CPB.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b): Contractor’s trust perception plays a mediating role between risk compensation and contractor’s CPB.

3.3. The mediating role of contractor’s fair perception

Franke et al. find that income distribution will affect participants’ fair perception (Franke, Keinz, and Klausberger Citation2013). Risk allocation is the most important income distribution measure in construction projects (Peckiene, Komarovska, and Ustinovicius Citation2013). Reasonable division of risk liability is the basis of cooperation between the contracting parties. The essence of contracting and performance process of construction contract is the game process between the contracting parties. It is usually close to the optimal state to establish a division interval of risk liability that both parties can bear (Yilin, Dong, and Yao Citation2015). Contractors have an expectation of their own risk liability scope in advance and set an acceptable range. If the income generated from the risk allocation of the contract is in this expected range, contractor will feel that it is fair; once this interval is exceeded, contractor will feel that he has exceeded his acceptance threshold, and the sense of unfairness will be significantly increased. Compensation symbolizes a kind of reciprocity of benefits and responsibilities and is contractor’s psychological expectation of risks and benefits. Reasonable risk compensation implies the existence of fairness (Yan Ling, Liu Liu, Zeng Cheng Citation2019). For example, Lehtiranta points out the impact of risk liability clauses in contract on contractor’s fair perception (Lehtiranta Citation2014). Aibinu’s study focuses on the impact of contract risk compensation clauses on contractor’s fair perception in the process of claim processing (Aibinu, Ling, and Ofori Citation2011). Therefore, the following are hypothesized:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Reasonable risk allocation can enhance contractor’s fair perception.

Hypothesis 4a (H4a): The more reasonable the risk liability, the stronger contractor’s fair perception.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b): The more reasonable the risk compensation, the stronger contractor’s fair perception.

Fair perception is an important behavioral inducement variable, which is an individual’s subjective judgment of whether his effort is consistent with his reward (Ling, Yi-fan, and Yu-wei Citation2018). In construction projects, a reasonable compensation mechanism can effectively enhance contractor’s fair perception and induce his CPB (Yan Ling, Liu Liu, Zeng Cheng Citation2019). In the research of fair perception inducing the behavior of all parties in a transaction, Liu et al. (Liu et al. Citation2012) have proven that fair perception is the key factor to enhance the cooperation effect from the construction project organization composed of multiple participants and that fair perception can also strengthen the positive influence of trust and communication on cooperation. At the same time, fair perception can inhibit opportunistic behavior and reduce management costs (Baird, Su, and Nuhu Citation2021). In construction project, if a contractor thinks that the transaction is fair, he may take active extra-role actions, such as actively improving the level of efforts, optimizing the design, and making up for contract loopholes (Ling, Liang, and Yan Citation2020). Through interviews and questionnaires with 41 experienced contractors in Singapore, Aibinu et al. find that fair perception will affect contractor’s work attitude and behavior in the process of processing engineering claims (Aibinu, Ling, and Ofori Citation2011). If a contractor feels a strong sense of unfairness, he will likely engage in opportunistic behavior, leading to contract disputes between client and contractor, resulting in a decrease in the efficiency of contract performance afterwards (Yan Ling, Liu Liu, Zeng Cheng Citation2019). Obviously, fair perception becomes the key factor to induce the project participants to actively perform their duties. Improving contractor’s fair perception can effectively reduce disputes and promote cooperation.

Therefore, in combination with hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 4, this study put forward the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Fair perception plays a mediating role between risk allocation and contractor’s CPB.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a): Fair perception plays a mediating role between risk liability and contractor’s CPB.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b): Fair perception plays a mediating role between risk compensation and contractor’s CPB.

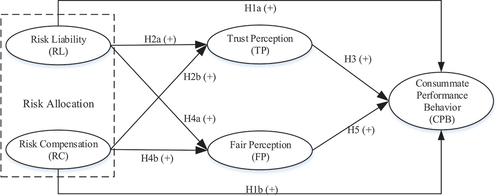

The above-mentioned series of hypotheses development discuss the relationship between risk allocation as an independent variable and contractor’s CPB as a dependent variable and choose trust and fair perception as mediating variables to study the direct and indirect paths of risk allocation affecting contractor’s CPB. The conceptual framework of this study is shown in .

4. Methods

4.1. Sampling and procedure

The respondents were drawn from clients’ and contractors’ project managers or contract managers, from different construction projects in Beijing, Tianjin, Anhui, Guangxi, Jiangsu, Guangdong, Shandong, and other regions. The questionnaires were collected by mail and on-site interviews. A total of 212 questionnaires were distributed from March to June 2020, and 164 valid questionnaires were received, with an effective response rate of 77.36%. See for the characteristics of interviewees and their items.

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents.

4.2. Questionnaire design

In the conceptual framework, the independent variable is the measurement of two dimensions of risk allocation, and the mediating variables are the measurement of contractor’s trust perception and fair perception. The dependent variable is the measurement of contractor’s CPB. The details are as follows: (1) Risk distribution and risk compensation were integrated the studies of Zhang (Zhang et al. Citation2016), (Yan Ling, Liu Liu, Zeng Cheng Citation2019), (Yilin and Hua Citation2013), etc.; (2) The definition of contractor’s CPB is closer to the concept of extra-role behavior and organizational citizenship behavior, therefore, this study referred to the relevant literatures and maturity scales, and made adaptive modification to form measurement items; (3) Contractor’s trust perception emphasizes contractor’s psychological perception of client’s risk allocation scheme based on mutual benefit preference. Since the study backgrounds of Xu (Zhichao et al. Citation2018), Zhang (Shui-bo, Jun-ying, and Zhen-yu Citation2015), Yin (Yin et al. Citation2020), Wang (Xueqing Citation2017), etc. are both about construction projects, the mature scale developed by them will be adopted in this study; (4) Contractor’s fair perception is adopted the measurement scale of contractor’s fair perception developed by Du et al. (Yaling, Huiling, and Hong Citation2016), and references the items developed by Zhang (Zhang et al. Citation2016), Luo (Luo Citation2007), Hatam (Hatam and Rezaei Citation2021), etc.

All questionnaire items were measured on a 5-point Likert-type. After the questionnaire was pretested, the focus group was used to invite relevant experts to discuss and provide feedback, and finally a questionnaire suitable for this study was formed, as shown in .

Table 2. Items of measurement and reliability and validity analysis.

Theoretically, in order to prevent a party involved in a project from having homologous deviation in risk allocation and CPB, the responses of clients, contractors, and the others (consultation, etc.) were collected to complement each other. Questionnaires were all distributed to project managers, department managers, or contract management professionals of project participants. Among them, client (35.37%), contractor (50.00%), and others (14.63%). After variance analysis, the results showed that there was no significant difference in their answer data at 95% confidence level.

4.3. Reliability and validity analysis

PLS-SEM was used to perform the conceptual framework test. It can be seen from that the loading of each item is greater than 0.8 (Hulland Citation2015). This indicates acceptable indicator reliability. The values of Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) are over 0.70 (see ). This indicates that each variable has good construct reliability (Hair, Ringle, and Sarstedt Citation2011). Results in indicate that the average variance extraction (AVE) values are in the range of 0.721–0.814, exceeding the satisfactory level of 0.50 (Hair et al. Citation2016), which prove that the scale has good convergence validity. As shown in , the AVE of each variable is higher than its squared correlation with any other variable, and each measurement item has the highest loading on the corresponding factor (see ), indicating acceptable discriminant validity.

Table 3. Correlation matrix and the square root of AVE of factors.

Table 4. Cross loadings for individual measurement items.

4.4. Test of the structural model and hypotheses

The SmartPLS 3.0 software was used to calculate the path coefficients and test their significance. The results of hypotheses testing are shown in and .

Table 5. Path coefficient and inspection results.

(1) The main effect test and data analysis

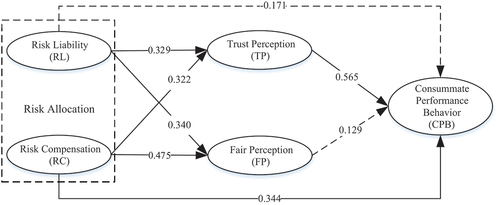

As seen in and , the path coefficient for the hypothesis test of risk liability and contractor’s CPB was −0.171, but its P value = 0.173 > 0.05, so it is assumed that H1a did not pass the test. This illustrates that risk liability does not have a significant inducing effect on contractor’s CPB. However, the path coefficient of the hypothesis test for risk compensation and contractor’s CPB was 0.344, and the p value was 0.022 < 0.05, so it is assumed that H1b passed the test. Obviously, risk compensation has a significant inducing effect on contractor’s CPB.

(2) Mediating effect test and data analysis

Firstly, from the results shown in and , the main effect test of risk liability and trust perception was 0.329, P = 0.009 < 0.05; the main effect test of risk compensation and trust perception was 0.322, P = 0.009 < 0.05. Therefore, hypotheses H2a and H2b passed the test. The test of the main effect of trust perception on contractor’s CPB was 0.565, P = 0.016 < 0.05. Based on the above numerical analysis and the test standard of Bootstrap Method of mediating effect, H3a and H3b passed the hypothesis test, it could be seen that trust perception plays a part in mediating between risk allocation and contractor’s CPB.

Secondly, the main effect test of risk liability and fair perception was 0.340, P = 0.004 < 0.05; the main effect test of risk compensation and fair perception was 0.475, P = 0.000 < 0.05. So hypothesis H4a and hypothesis H4b passed the test, and risk allocation had a positive effect on the contractor’s perception of fairness. However, the contractor’s perception of fairness had no significant impact on his performance. The hypothesis test of the effect of fair perception on CPB was 0.129, P = 0.226 > 0.05. Therefore, hypothesis H5a and H5b did not pass the test. This illustrated that fair perception has no mediating effect between contract risk allocation and contractor’s CPB.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Contract risk allocation’s impact on contractor’s CPB

The results showed that reasonable risk compensation can promote contractor’s CPB (H1b), which is in line with prior studies of Yan et al. (Yan Ling, Liu Liu, Zeng Cheng Citation2019; Ling et al. Citation2017), who have proved by situational experiments that reasonable risk compensation can guarantee contractor to get corresponding compensation for the risks he bears and encourage the contractor to continuously improve the level of efforts and achieve good performance. This study obtained a similar conclusion by developing a formal and explicit model and empirically tested and generally confirmed. Reasonable risk compensation emphasizes that the contract price signed by both parties is reasonable compared with the risk borne by the contractor. It also means that when a contractor bears risks other than those preset in the contract due to changes in the external environment, the contract should be provided with corresponding adjustment measures, so that the contractor can get corresponding reasonable profits and opportunity benefits.

The results showed that contract risk liability has no impact on contractor’s CPB (H1a). This is inconsistent with Zhang et al. (Zhang, Zhang, Ying et al. Citation2016), who find that it will induce contractor’s CPB when the risk liability meets contractor’s expectation. The reasonable risk liability mechanism reflects the fairness of the transaction and shows the goodwill of the client to the contractor and the determination to cooperate. From the contract reference point theory, the efficiency of ex-post execution of the initial contract injected with reasonable risk liability depends on contractor’s sense of entitlement. Specifically, if the ex-post result is consistent with the expectation of the contract reference point, contract risk liability can stimulate contractor’s CPB. On the contrary, contractors will only implement the minimum standards and adopt perfunctory performance behavior, and may even cause the performance of the project to be impaired.

5.2. Mediating effect of trust perception

Hypotheses H2a and H2b passed the test, which proved that contract risk allocation has a positive impact on contractor’s trust perception. For the consideration of efficiency and fairness, a client should bear the risks within his own control scope and give the contractor reasonable risk compensation at the same time, which can reduce the risk management cost of the contractor and improve the project performance. In construction projects, the contracting parties have established a sharing relationship based on the economic incentives of the contract. However, the contracting parties are generally faced with an asymmetric trading situation, and the client setting up a reasonable risk allocation mechanism is to send a good faith signal to the contractor. At the same time, due compensation is given to the contractor for the state changes in the contract execution process, which shows the dynamic changes in the generation and maintenance of trust between the two parties.

Hypotheses H3a and H3b passed the test, which showed that trust perception has a positive effect on contractor’s CPB. Trust perception provides motive support for the mutual benefit and win–win relationship between the parties. In a relationship of strong trust, contractor changes from short-sighted pursuit of unilateral interests to pursuit of project value-added. The establishment of trust relationship reduces the anxiety of the contracting parties to the possible losses of the other party, makes the distribution of rights, responsibilities, and interests more reasonable, and promotes the positive cooperative behavior of both parties. In the process of project implementation, contractors should deepen the consideration of the overall benefits of the project, activate the power source of self-improvement, increase the investment in improving the project performance, and actively take actions beyond the contract.

Although risk liability has no direct effect on contractor’s CPB, it indirectly promotes contractor’s CPB after trust perception is added as a mediating variable. This proves that trust perception plays a part-mediating role between risk allocation and contractor’s CPB, that is, the establishment of trust plays a promoting role in the process of risk allocation affecting contractor’s CPB. As a manifestation of reciprocal preference, trust perception eliminates contractors from taking opportunistic measures and increases additional motivation for CPB. Reasonable risk allocation scheme provides compensation for contract constraint and contract state change, so client and contractor can receive corresponding compensation. It has also got rid of strict contract constraints and strong organizational control, providing a broad space for contractors to create value-added contract agreements. The expected accumulation of long-term income leads to the formation of contractor’s CPB, which explains why trust perception becomes a mediating variable between risk allocation and contractor’s CPB. Reasonable risk allocation strategy arouses the trust of contractor, and enhances contractor’s CPB.

5.3. Mediating effect of fair perception

The results show that hypotheses H4a and H4b passed the test, risk liability and risk compensation have positive effects on contractor’s fair perception. Risk liability should be reasonable, too many risks cannot be transferred to contractor (Zhichao et al. Citation2018). If the contractor bears too many risks in the project implementation process, even if his quotation includes certain risk compensation fees, the contractor will still suffer from serious unfairness due to taking too many risks (Zhang, Zhang, Ying et al. Citation2016). Yin et al. (Yin et al. Citation2020) reveal the impact path of reasonable risk allocation on project income from the perspective of social capital, believing that reasonable risk allocation clauses can enhance the fair perception of contractors and promote cooperation between the two parties.

However, hypotheses H5a and H5b did not pass the test, it showed that contractor’s fair perception has no significant impact on his CPB. The reason lies in two aspects: (1) contractor’s fair perception mainly comes from the comparison between the return and the payment generated by the risk allocation and from the economic incentive of the contract risk allocation to contractor. From the perspective of psychological perception, people are more likely to accept upward adjustments than downward adjustments, that is, contractors are more sensitive to unreasonable risk allocation. The contractor will preset an anchor value for risk allocation at the initial stage, which can be accepted. If a client formulates a more stringent risk allocation scheme, resulting in a deviation between the allocation of rights and responsibilities in the contract and contractor’s expectation, the part lower than the expectation will be regarded as individual loss, thus the contractor will feel a strong sense of unfairness and take opportunistic actions to punish the client. (2) The contract reference point theory proposed by Hart and Moore points out that the consummate performance achieved by CPB is the basis of value-added benefit sharing (Hart and Moore Citation2008). The CPB is an altruistic act based on self-interest and also an altruistic act outside the role, including actively controlling risks and making up the contract loopholes. The whole life cycle of the project and the complexity of the situation determine the diversity of contractor’s motivation for performing the contract. Only contractor’s fair perception can usually not motivate contractor’s CPB.

6. Conclusions and implications

Based on the contract reference point theory, this study constructs a conceptual framework among risk allocation, trust perception, fair perception, and contractor’s CPB. The empirical analysis through the data collected by questionnaire reveals the mechanism that contract risk allocation triggers contractor’s CPB. The study results enrich the contract reference point theory and provide the basis for client to design contract clauses that effectively encourage contractor’s CPB.

6.1. Theoretical implications

Compared with previous studies, the theoretical implications of this study are the following two aspects:

First, a lot of the existing literatures believe that risk allocation scheme in contract will significantly affect contractor’s fair perception, the more reasonable the contract risk allocation scheme is, the better the fair perception of contractor will be. However, the conclusion of this study finds that only relying on contractor’s fair perception cannot induce contractor’s CPB. Attention should be paid to, but the role of fair perception of contractors should not be exaggerated.

Second, previous studies on the incentive effect of contract risk allocation have mostly focused on how to inhibit opportunistic behavior, without considering whether contract risk allocation can encourage contractors to choose a higher level of performance behavior. This study reveals that construction project contract risk allocation scheme needs to trigger contractor’s trust perception, so as to more effectively induce contractor to engage in CPB and truly play the incentive effect of contract risk allocation.

6.2. Managerial implications

According to the conclusions of this study, combined with the specific situation of construction projects, the following suggestions are put forward for contract design guided by contractor’s CPB:

6.2.1. Improve contract risk allocation scheme so as to provide health incentives for contractor’s CPB

At the present stage of Chinese construction market, due to the dominant position, client often distributes most of the risks to contractor to reduce his own costs, resulting in unreasonable transfer of risks. This study has confirmed the incentive effect of reasonable risk allocation on contractor, so it is necessary for client to further improve the rationality of the risk allocation scheme in contract and to motivate contractor’s CPB.

Nonetheless, this study found that the economic incentive generated by relying solely on risk allocation can induce contractor’s fair perception, but it cannot necessarily stimulate his CPB. However, contractor’s trust perception induced by the cooperative value generated by contract risk allocation is part of the intermediary path to stimulate contractor’s CPB. Therefore, when formulating a risk allocation strategy, the client should consider setting up an incentive mechanism that matches the contractor’s trust perception, so as to better induce contractor’s CPB.

6.2.2. Establish a project management mode of “mutual trust and cooperation” between client and contractor to provide continuous incentives for contractor’s CPB

The current idea of construction contract designing still aims at the realization of perfunctory performance, which is obviously not conducive to the realization of the goal of engineering procurement construction aiming at inspiring contractor’s CPB and the value-added of the project. This study proved that client’s designing of contract should not only pay attention to giving reasonable economic compensation to contractors, but also pay attention to improving contractor’s reputation through contract execution, commending and establishing friendly cooperative relations, strengthening its trust perception, and promoting contractor’s choice of CPB.

6.3. Limitations and future research

There are still deficiencies in this research. Firstly, based on the contract reference point theory, this study reveals the formation mechanism of contractor’s CPB, but it is not enough to fully reveal the concrete representation and formation of the CPB. Therefore, in the future study of this study, more and deeper behavioral inducing factors should be considered to promote the realization of contractor’s CPB. Secondly, due to the consideration of the length of this paper, the hypotheses of risk allocation and contractor’s CPB in this study are not differentiated according to different project types, but are considered as a whole. However, according to actual experience, different types of projects adopt different risk allocation strategies. Therefore, the following study can make further distinction, so as to obtain more reasonable results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request ([email protected]).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Qing Lin

Qing Lin, doctor in management, senior consulting engineer, Zonleon Construction Consulting Co., Ltd, Guangzhou 510640, China. Email: [email protected].

Ling Yan

Ling Yan, doctor in management, professor in Dept. of Construction Management, School of Management, Tianjin University of Technology, Tianjin 300384, China. Email: [email protected].

Yilin Yin

Yi-lin Yin, professor, School of Management, Tianjin University of Technology, Tianjin 300384, China. Email: [email protected] Yin, professor, School of Management, Tianjin University of Technology, Tianjin 300384, China. Email: [email protected].

References

- Abednego, M. P., and S. O. Ogunlana. 2006. “Good Project Governance for Proper Risk Allocation in public-private Partnerships in Indonesia [J].” International Journal of Project Management 24 (7): 622–634. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2006.07.010.

- Ahimbisibwe, A. 2014. “The Influence of Contractual Governance Mechanisms, Buyer–Supplier Trust, and Supplier Opportunistic Behavior on Supplier Performance [J].” Journal of African Business 15 (1–3): 85–99. doi:10.1080/15228916.2014.920610.

- Ahmed, A., B. Kayis, and S. Amornsawadwatana. 2007. “A Review of Techniques for Risk Management in Projects [J].” Benchmarking An International Journal 14 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1108/14635770710730919.

- Aibinu, A. A., F. Y. Y. Ling, and G. Ofori. 2011. “Structural Equation Modelling of Organizational Justice and Cooperative Behaviour in the Construction Project Claims Process: Contractors” Perspectives [J].” Construction Management and Economics 29 (5): 463–481. doi:10.1080/01446193.2011.564195.

- Anvuur, A. M., M. M. Kumaraswamy, and M. Asce. 2012. “Measurement and Antecedents of Cooperation in Construction [J].” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 138 (7): 797–810. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000498.

- Attila, A., and E. Matt. 2021. “Investments in Social Ties, Risk Sharing, and inequality[J].” The Review of Economic Studies 88 (4): 1624–1664. doi:10.1093/RESTUD/RDAA073.

- Baird, K., S. X. Su, and N. Nuhu. 2021. “The Mediating Role of Fairness on the Effectiveness of Strategic Performance Measurement Systems [J].” Personnel Review ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print) doi:10.1108/PR-07-2020-0573

- Barnes, M. 1983. “How to Allocate Risks in Construction Contracts [J].” International Journal of Project Management 1 (1): 24–28. doi:10.1016/0263-7863(83)90034-0.

- Chan, E. H., and M. C. Au. 2008. “Relationship between Organizational Sizes and Contractors’ Risk Pricing Behaviors for Weather Risk under Different Project Values and Durations [J].” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 134 (134): 673–680. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2008)134:9(673).

- Cha, H. S., and K. Y. Shin. 2011. “Predicting Project Cost Performance Level by Assessing Risk Factors of Building Construction in South Korea [J].” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 10 (2): 437–444. doi:10.3130/jaabe.10.437.

- Du, Y., H. Li, and H. Ke. 2016. “Development and Verification of the Scales for Perceived Justice of Contractors in Construction Project in China Context [J].” Journal of Systems & Management 25 (1): 165–174. doi:10.05.2542.2016/01.0165-10.

- Fehr, E., O. Hart, and C. Zehnder. 2011. “Contracts as Reference Points–Experimental Evidence [J].” American Economic Review 101 (2): 493–525. doi:10.1257/aer.

- Franke, N., P. Keinz, and K. Klausberger. 2013. ““Does This Sound like a Fair Deal?”: Antecedents and Consequences of Fairness Expectations in the Individual’s Decision to Participate in Firm Innovation [J].” Organization Science 24 (5): 1495–1516. doi:10.1287/orsc.1120.0794.

- Hair, J. F., Jr, G. T. M. Hult, C. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2016. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). ousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications.

- Hair, J. F., C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2011. “PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet[J].” Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice 19 (2): 139–152. doi:10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202.

- Hart, O., and J. Moore. 2008. “Contracts as Reference Points [J].” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123 (1): 1–48. doi:10.1162/qjec.2008.123.1.1.

- Hatam, A., and S. Rezaei “Investigating of the Relationship between Mentoring and Job Satisfaction with Regard to the Mediating Role of Organizational Justice and Commitment in Nurses.” 2021.

- Hulland, J. 2015. “Use of Partial Least Squares (PLS) in Strategic Management Research: A Review of Four Recent Studies [J].” Strategic Management Journal 20 (2): 195–204. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195::.

- Hwang, B. G., X. Zhao, and M. Gay. 2013. “Public Private Partnership Projects in Singapore: Factors, Critical Risks and Preferred Risk Allocation from the Perspective of contractors[J].” International Journal of Project Management 31 (3): 424–433. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.08.003.

- Klotz, A. C., and M. C. Bolino. 2013. “Citizenship and Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Moral Licensing View [J].” Academy of Management Review 38 (2): 292–306. doi:10.5465/amr.2011.0109.

- Kraft, T., L. Valdés, and Y. Zheng. 2017. “Supply Chain Visibility and Social Responsibility: Investigating Consumers’ Behaviors and Motives [J].” Manufacturing & Service Operations Management. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2518627.

- Lau, C. D., and L. W. Lam. 2008. “Effects of Trust and Being Trusted on Team Citizenship Behavior in Chain Stores [J].” Asian Journal of Social Psychology 11 (2): 141–149. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2008.00251.x.

- Lehtiranta, L. 2014. “Risk Perceptions and Approaches in multi-organizations: A Research Review 2000-2012 [J].” International Journal of Project Management 32 (4): 640–653. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.09.002.

- Lester, S. W., and H. H. Brower. 2003. “In the Eyes of the Beholder: The Relationship between Subordinates’ Felt Trustworthiness and Their Work Attitudes and Behaviors [J].” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 10 (2): 17–33. doi:10.1177/107179190301000203.

- Li, Y., Y. Lu, and Q. Cui. 2019. “Organizational Behavior in Megaprojects: Integrative Review and Directions for Future Research [J].” Journal of Management in Engineering 35 (4): 4. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000691.

- Lim, B. T., and M. Loosemore. 2017. “The Effect of inter-organizational Justice Perceptions on Organizational Citizenship Behaviors in Construction Projects [J].” International Journal of Project Management 35 (2): 95–106. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.10.016.

- Ling, Y., G. Liang, and N. Yan. 2020. “Understanding Construction Contractors’ Intention to Undertake Consummate Performance Behaviors in Construction Projects [J].” Advances in Civil Engineering. doi:10.1155/2020/3935843.

- Ling, Y., H. Yi-fan, and C. Yu-wei. 2018. “Reference Point Relative Value of Construction Contract, Perception of Fairness and Contractor’ Performance Behavior [J].” Industrial Engineering and Management 23 (4): 68–75,84. doi:10.19495/j.cnki.1007-5429.2018.02.010.

- Ling, Y., W. Zhixiu, and D. Jiaojiao. 2018. “Research on Structural Dimensions and Measurement of Contractors’ Performance [J].” China Civil Engineering Jounal, no. 8: 105–117. doi:10.15951/j.tmgcxb.2018.08.012.

- Ling, Y. A. N., Z. H. A. N. G. Zhudong, Y. A. N. Min, and D. E. N. G. Jiaojiao. 2017. “Research on Fairness Concerns of Contractor in Construction Projects Based on Contractual Reference Point Effect—The Case Study of Metro Projects [J].” Chinese Journal of Management 14 (10): 1561–1569. doi:10.3969/j.ssn.1672-884x.2017.10.018.

- Liu, Y., Y. Huang, and Y. Luo. 2012. “How Does Justice Matter in Achieving Buyer–Supplier Relationship Performance? [J].” Journal of Operations Management 30 (5): 355–367. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2012.03.003.

- Liu, J., Z. Wang, and M. Skitmore. 2019. “How Contractor Behavior Affects Engineering Project Value-Added Performance [J].” Journal of Management in Engineering 35 (4). doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000695.

- Li, X., Y. Yin, and R. Zhang. 2020. “Examining the Impact of relationship-related and process-related Factors on Project Success: The Paradigm of Stimulus-Organism-Response [J].” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 1–17. doi:10.1080/13467581.2020.1828090.

- Lu, P., S. Guo, and L. Qian. 2015. “The Effectiveness of Contractual and Relational Governances in Construction Projects in China [J].” International Journal of Project Management 33 (1): 212–222. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.03.004.

- Luo, Y. 2007. “The Independent and Interactive Roles of Procedural, Distributive, and Interactional Justice in Strategic Alliances [J].” The Academy of Management Journal 50 (3): 644–664. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2005.04.001.

- Mayer, R. C., J. H. Davis, and F. D. Schoorman. 1995. “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust [J].” Academy of Management Review 20 (3): 709–734. doi:10.2307/258792.

- Memon, S. A., S. Rowlinson, R. Y. Sunindijo, and H. Zahoor. 2021. “Collaborative Behavior in Relational Contracting Projects in Hong Kong—A Contractor’s Perspective [J].” Sustainability 13 (10): 5375. doi:10.3390/su13105375.

- Meng, X. 2012. “The Effect of Relationship Management on Project Performance in Construction [J].” International Journal of Project Management 30 (2): 188–198. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.04.002.

- Nguyen, D. T., R. Rameezdeen, and N. Chileshe. 2021. Effect of Customer Cooperative Behavior on Reverse Logistics Outsourcing Performance in the Construction Industry -A Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling approach[J].” . Engineering Construction & Architectural Management 1–18. doi:10.1108/ECAM-11-2020-0967.

- Pan, X., M. Chen, and Z. Hao. 2017. “The Effects of Organizational Justice on Positive Organizational Behavior: Evidence from a Large-Sample Survey and a Situational Experiment [J].” Frontiers in Psychology, no. 8: 2315–2331. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02315.

- Pang, H. Y., S. O. Cheung, and C. C. Mei. 2015. “Opportunism in Construction Contracting: Minefield and manifestation[J].” International Journal of Project Organisation & Management 7 (1): 31–55. doi:10.1504/IJPOM.2015.068004.

- Peckiene, A., A. Komarovska, and L. Ustinovicius. 2013. “Overview of Risk Allocation between Construction Parties [J].” Procedia Engineering 57: 889–894. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2013.04.113.

- Pei, Z., Z. Guo-jie, and Y. Yin-li. 2015. “Impact of Trust Convergence and Trust Perception Difference on Risk Allocation–Exploration of Inter-organizational Trust in Project [J].” Soft Science 189 (9): 127–129. doi:10.13956/j.ss.1001-8409.2015.09.27.

- Pierce, J. L., and D. G. Gardner. 2004. “Self-Esteem, within the Work and Organizational Context: A Review of the Organization-Based Self-Esteem Literature [J].” Journal of Management 30 (5): 591–622. doi:10.1016/j.jm.2003.10.001.

- Qin, Z., F. Hua, and H. Tang. 2010. “Stability Analysis of Cooperation between Owners and Contractors in the Construction Market [J].” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 9 (2): 409–414. doi:10.3130/jaabe.9.409.

- Richardson, H. A., S. G. Taylor, D. H. Kluemper, and T. Little. 2021. “and Too Much Authority?haring: Differential Relationships with Psychological Empowerment and In-role and Extra-role Performance [J].” Journal of Organizational Behavior 42 (8): 1099–1119. doi:10.1002/job.2548.

- Seibert, S. E., S. R. Silver, and W. A. Randolph. 2004. “Taking Empowerment to the Next Level: A Multiple-Level Model of Empowerment, Performance, and Satisfaction [J].” The Academy of Management Journal 47 (3): 332–349. doi:10.2307/20159585.

- Serva, M. A., M. A. Fuller, and R. C. Mayer. 2010. “The Reciprocal Nature of Trust: A Longitudinal Study of Interacting Teams [J].” Journal of Organizational Behavior 26 (6): 625–648. doi:10.1002/job.331.

- Shui-bo, Z. H. A. N. G., C. H. E. N. Jun-ying, and H. U. Zhen-yu. 2015. “Effect of Contract on Contractor’s Cooperative Behavior in Construction Project: Trust as a Mediator [J].” Journal of Engineering Management, no. 4: 6–11. doi:10.13991/j.cnki.jem.2015.04.002.

- Skitmore, M., B. Xiong, and B. Xia. 2020. “Relationship between Contractor Satisfaction and Project Management performance[J].” Construction Economics and Building 20 (4): 1–24. doi:10.5130/AJCEB.v20i4.7366.

- Tallaki, M., and E. Bracci. 2021. “Risk Allocation, Transfer and Management in public–private Partnership and Private Finance Initiatives: A Systematic Literature review[J].” International Journal of Public Sector Management 34 (7): 709–731. doi:10.1108/IJPSM-06-2020-0161/full/html.

- Tsai, T.-C., and M.-L. Yang. 2009. “Risk Management in the Construction Phase of Building Projects in Taiwan [J].” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 8 (1): 143–150. doi:10.3130/jaabe.8.143.

- Von Branconi, C., and C. H. Loch. 2004. “Contracting for Major Projects: Eight Business Levers for Top Management [J].” International Journal of Project Management 22 (2): 119–130. doi:10.1016/S0263-7863(03)00014-0.

- Wang, G., Q. He, and B. Xia. 2018. “Impact of Institutional Pressures on Organizational Citizenship Behaviors for the Environment: Evidence from Megaprojects[J].” Journal of Management in Engineering 34 (5). doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000628.

- Williamson, O. E. 1975. “Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications: A Study in the Economics of Internal Organization [J].” Accounting Review 86 (343): 619. doi:10.2307/2230812.

- Wu, G., H. Li, and C. Wu. 2020. “How Different Strengths of Ties Impact Project Performance in Megaprojects: The Mediating Role of trust[J].” International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 13 (4): 889–912. doi:10.1108/IJMPB-09-2019-0220.

- Xueqing, W. 2017. “Xu Shusheng and Xu Zhichao, Employer’s Risk Allocation and Contractor’s Behavior in Project Organization: Parallel Mediating Effect of Contractor’s Feeling Trusted and Contractor’s Trust [J].” Management Review 29 (5): 131–142. doi:10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2017.05.012.

- Yan, L, and L. Guo. 2020. “Research on Influencing Factors of Consummate Performance Behaviors: A Configurational Approach [J].” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 19 (6): 559–573. doi:10.1080/13467581.2020.1761817.

- Yan Ling, Liu Liu, Zeng Cheng. 2019. “The Influence of Contract Risk Sharing Clause on the Contractors’ Fairness Perception—An Experimental Study under the Theory of Multiple Reference Points [J].” Journal of Beijing Institute of Technology (Social Sciences Edition) 21 (2): 67–77. doi:10.15918/j.jbitss1009-3370.2019.1319.

- Yilin, Y., Y. Dong, and W. Yao. 2015. “Study on Impact of Trust on Risk Allocation in Construction Project: A Semi-structured Interview Based on Grounded Theory [J].” China Civil Engineering Journal, no. 9: 117–128. doi:10.15951/j.tmgcxb.2015.09.014.

- Yilin, Y., and Z. H. A. O. Hua. 2013. “A Study of Risk Allocation Measurement of Construction Project: Model Construction, Development of Scale and Validity Test [J].” Forecasting 32 (4): 8–14.

- Yin, Y., Q. Lin, W. Xiao, and H. Yin. 2020. “Impacts of Risk Allocation on Contractors’ Opportunistic Behavior: The Moderating Effect of Trust and Control [J].” Sustainability 12 (22): 9604. doi:10.3390/su12229604.

- Zhang, S., J. Li, and Y. Li. 2021. “Revenue Risk Allocation Mechanism in Public-Private Partnership Projects: Swing Option Approach [J].” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 147 (1): 1. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001952.

- Zhang, S., S. Zhang, and G. Ying. 2016. “Contractual Governance: Effects of Risk Allocation on Contractors’ Cooperative Behavior in Construction Projects [J].” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 142 (6): 6. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001111.

- Zhichao, X., Y. Yilin, L. Dahui, and J. B. Glenn. 2018. “Owner’s Risk Allocation and Contractor’s Role Behavior in A Project: A Parallel-mediation Model [J].” Engineering Management Journal 30 (1): 14–23. doi:10.1080/10429247.2017.1408388.

- Zhou, Y., C. Zuo, and Y. Chen. 2012. “An Experimental Study on Risk Aversion of Individuals with Social Preference [J].” Management World 225 (6): 86–95. doi:10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2012.06.008.