ABSTRACT

Since the early 2010s, budgetary policy-making in EU member states has been subject to tighter European constraints. While recent research shows the relevance of intergovernmental negotiations for setting European policy priorities, little is known about how much political alternation in government still matters for national budgetary agendas. This paper investigates this question in Germany, one of Europe’s most powerful and financially stable countries. Drawing on original data, the paper first shows how political alternation in German cabinets changes governments’ budgetary agendas. Secondly, it shows how this alternation also influences the formulation and adoption of European policy recommendations. Based on these findings, the paper argues that governments in financially stable countries can pursue alternative policy agendas, but that these need to find consensus at both the national and European level. The range of alternatives is therefore inevitably contingent upon the national institutional framework and country’s relative strength within the EU.

Introduction

The reform of European Economic Governance (EEG) that was agreed between 2009 and 2013 brought substantial changes to the ways in which national political decisions are taken, particularly in the sphere of socio-economic policies (Laffan, Citation2014; Maatsch & Cooper, Citation2017). More than before, EU member states are now subject to tighter fiscal rules (Doray-Demers & Foucault, Citation2017), and through the process of the European Semester they must also increasingly coordinate their policies with European institutions (Verdun & Zeitlin, Citation2018). The reform of EEG inevitably altered the traditional democratic feedback loop of socio-economic policy-making, particularly for the drafting of governments’ yearly budgets (Crum, Citation2018). While in the traditional scheme national budgetary policy was primarily an affair between national governments and parliaments – with international and European rules serving merely as benchmarks that could be violated (e.g., Karremans & Damhuis, Citation2018) – today finance ministers must increasingly negotiate the direction of their policies at the European level (Maricut & Puetter, Citation2018). This raises new questions about the current locus of political decision-making, and about the extent to which the political preferences of democratically elected governments are still relevant for the direction of socio-economic policies (Crum, Citation2018; Maatsch & Cooper, Citation2017; Mair, Citation2013).

One argument that gained prominence in the early 2010s is that the new EEG is reducing room for national political alternatives, imposing across the Eurozone a policy of fiscal discipline and rendering socio-economic policy-making merely a technocratic exercise of meeting EU thresholds (Scharpf, Citation2015; Schäfer & Streeck, Citation2013). Recent empirical research, however, highlights how the reform of EEG was largely the result of intergovernmental negotiations, wherein one coalition of member states asserted its political preferences for economic governance (Wasserfallen et al., Citation2019). In addition, there is increasing evidence showing that the European Semester does not only promote sound public finances, but also provides tailor-made recommendations for countries to improve their social security provisions (D'Erman et al., Citation2019; Zeitlin & Vanhercke, Citation2018). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, intergovernmental negotiations – particularly among finance ministers – play a dominant role in the definition of the Semester’s policy priorities (Maricut & Puetter, Citation2018).

This prominent role of intergovernmental negotiations entails that governments’ political preferences are indeed relevant for the policies agreed at the European level. Consequently, the relevance of governments’ preferences for EEG obliges EU scholars to bring into the picture the alternation in government between different political forces, and to raise (again) the question of whether and how the alternation in government between different parties generates different political alternatives for socio-economic policy-making. Answering this question is not only relevant for a better understanding of the inner workings of EEG, but also for the assessment of the quality of national democracies under the newly reformed EEG (Crum, Citation2018; Maatsch & Cooper, Citation2017).

The quality of democracy under EEG has been assessed as relatively poor in Southern European debtor countries. These are member states featuring high levels of debt and deficits and where, consequently, the need to meet European budgetary targets has resulted at times in ‘democracy without choice’ (Matthijs, Citation2017; Ruiz-Rufino & Alonso, Citation2018). Yet, the severity of the national budgetary crises in countries like Italy and Greece does not allow for more general inferences about the extent to which EEG restricts political alternatives when public finances are stable. This paper therefore investigates this question for the case of Germany, one of Europe’s most financially stable countries, as well as a leading actor in the EU’s intergovernmental decision-making process (Schild, Citation2013; Schoeller, Citation2017; Wasserfallen et al., Citation2019). The question is addressed by studying whether alternation between different parties in consecutive German governments generates policy alternatives in the face of EEG.

Drawing on original data collection from finance ministers’ national budget speeches, the paper shows how the political and policy content of German budgetary discourse between 2009 and 2019 changed under cabinets of different political composition. This change, however, also runs parallel to the ‘socialisation of the European Semester’, as recent country-specific recommendations (CSRs) have called upon German governments to make use of the state’s fiscal surplus and to increase domestic expenditure (D'Erman et al., Citation2019; Zeitlin & Vanhercke, Citation2018). Consequently, the paper explores the origins of the government’s most recent expansive policy proposals, showing that these were domestic political initiatives that were subsequently incorporated in the EU’s CSRs. The paper therefore presents new empirical insights into the democratic feedback loop of EEG, showing evidence for two-way political influences between the national and European levels.

The paper proceeds as follows. First it contextualises the question of political alternatives and institutional constraints for the case of Germany. It then discusses the empirical contribution from the comparative study of budget speeches and presents the methodology. Section 4 presents the empirical findings, showing a substantial shift from a fiscal consolidation discourse to a considerably more socially-oriented discourse, referring to both national and European policies. Subsequently, Section 5 explores the feedback loop between European CSRs and domestic budgetary policy-making. Based on the evidence collected, Section 6 concludes by arguing that, despite the strengthening of EEG, in countries that are not in financial difficulty the rotation in national governments between political parties still generates different policy alternatives, but these are contingent upon both the country’s domestic institutional framework as well as the country’s relative power in the European institutional framework. For German governments, the latter has so far turned out to be less constraining than the former.

Political alternation and institutional constraints in Germany during the 2010s

During the last decade, the partisan composition of German governments shifted from strongly leaning towards the centre-right between 2009 and 2013, to featuring from 2013 onwards a grand coalition between the Christian-democratic parties (CDU-CSU) and the Social Democrats (SPD). Both the CDU and SPD campaigned on pro-welfare positions during the 2013 and 2017 elections (Bremer, Citation2019; Rixen, Citation2019). The SPD’s entry into the cabinet constitutes a potential source of change in the policy course of German governments, creating the political conditions for moving from a conservative to a potentially more expansive policy approach. Even though Germany’s domestic institutional framework considerably restricts the potential political influence of individual political parties due to its multiparty system favouring the formation of coalition governments (Lijphart, Citation2012; Schmidt, Citation1995), recent research has shown how between 1989 and 2009 the partisan composition of governments had substantial effects on their policy agendas (Hübscher, Citation2019).

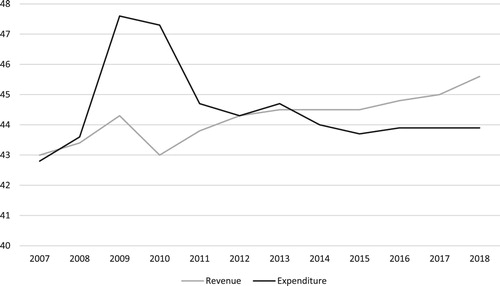

Since 2010, however, like most other EU member states, German governments have been subject to an additional layer of fiscal stringency rules (Doray-Demers & Foucault, Citation2017). In late 2009, Germany adopted the Schuldenbremse (debt-brake), a constitutional law that obliges public administrations to achieve balanced budgets, not allowing deficit spending. In 2013 this approach to public spending was strengthened even further, with the introduction of a law establishing that the government’s structural deficit should not be higher than 0.5 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) (European Commission, Citation2019a). The introduction of these legal obligations strongly influenced Germany’s fiscal output during the 2010s (Rixen, Citation2019). After having risen quickly in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, German public spending was brought below the revenues level within the course of one legislature, marking the beginning of several years of fiscal surpluses. shows the yearly levels of government revenues and spending between 2007 and 2018, measured as a percentage of GDP.

Figure 1. Public spending and revenues in Germany as % of GDP (2007–2018). Source: Eurostat (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database).

The conservative fiscal approach was most strongly pursued during the years of the centre-right second Merkel government (2009–2013), with the CDU’s finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble being a strong advocate of fiscal consolidation and the junior coalition partner Free Democrats (FDP) being strongly against public overspending (Rixen, Citation2019). Despite the SPD replacing the FDP in government after the 2013 elections, the prudent fiscal policy-approach continued under the third Merkel government (2013–2017). Besides a few social policy initiatives (Voigt, Citation2019), the government’s overall fiscal policy remained largely influenced by the conservative finance minister Schäuble, who was strongly committed to avoiding any new debts and deficits (Rixen, Citation2019, p. 405).

At the 2017 elections, both the CDU-CSU and SPD lost a considerable share of their votes but due to the failing coalition talks between Christian-democrats, FDP and the Greens, they once again formed a grand coalition, despite widespread reluctance among the SPD base. In subsequent regional and European elections, the vote shares of the governing parties kept falling, particularly for the SPD. Among left-oriented voters, the biggest disappointment of the government experience was the perceived reluctance to prioritise expansive social and environmental policies over the zero-deficit rule and the debt-brake law (Barber, Citation2019), a dilemma that is increasingly common to most social-democratic parties in Europe (Hertner, Citation2018; Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2019).

In the fourth Merkel government (2018-), the finance ministry has been led by the Social Democrat Olaf Scholz. The minister’s social-democratic affiliation entailed strong electoral pressures on the finance ministry to break away from the previous austerity paradigm (Engelen, Citation2018). Scholz’s first public statements as finance minister largely disappointed these hopes, as they underlined the continuation of the commitment to the debt-brake law (Streeck, Citation2019). In recent public statements, however, Scholz loosened this policy stance, and announced that in the near future the government might decide not to stick to the zero-deficit rule (Spiegel Online, Citation2019). In the budgetary plans for 2020, the government committed to substantial social and environmental investments (Bundesregierung, Citation2019).

The German context thus features an alternation in the government coalition between the FDP and the SDP, and subsequently an alternation between a Christian-democratic and a social-democratic finance minister. Through this alternation, in recent years the finance minister has been subject to strong electoral pressures to increase social expenditure, while at the same time inheriting the institutional constraints related to the constitutional debt-brake. These factors allow exploring the extent to which in a financially stable country like Germany, alternation in government generates alternative socio-economic policy agendas despite institutional constraints and binding fiscal stringency rules. To this end, this paper analyses the budget speeches delivered by German finance ministers between January 2010 and September 2019, with the aim of grasping whether there are substantial differences in the budgetary policy-proposals and justifications of Olaf Scholz and those of Wolfgang Schäuble.

Analysis of finance ministers’ budget speeches

The study of budget speeches relies on the assumption that in institutional contexts, politicians are expected to consistently link their proposals with actions or facts (Green-Pedersen & Walgrave, Citation2014; Veen, Citation2011, p. 31). Compared to the more frequently studied discourse of electoral campaigns, speeches given in institutional contexts bring us further down the implementation chain (John et al., Citation2013, p. 196). In Germany, the yearly budget speeches are generally delivered every second Tuesday in September. When the country holds elections – which also generally take place in September – the speech and debate are postponed until the following winter or spring. Speeches mark the beginning of a week of parliamentary debates about the government’s finances and socio-economic policies for the following year. They contain an assessment of the current budgetary situation, outline the actions the government has taken in the past year, and present the government’s budgetary proposals for the coming year.

The speeches analysed in this paper are those of the last three Merkel governments, starting from the first budget speech of the Merkel II government in January 2010 and ending with the budget speech of the Merkel IV government in September 2019. Eight of these speeches (2010–2016) were given by the CDU’s Wolfgang Schäuble, of which the first four were in coalition with the FDP and the second four in coalition with the SDP. The last three speeches (2018–2019) were instead given by the social-democrat Olaf Scholz (for a detailed list, please see Online Appendix, Table A1).

The analysis entails collecting the statements with which finance ministers justify the actions of the government, and coding both the policy-type that is being discussed, as well as the argument that is used for justification. The analysis of the eleven speeches produced a total of 1454 units of observation, or policy justification statements, which corresponds to an average of 130 observations per speech. The following excerpt from the speech by Wolfgang Schäuble from September 2012 features a most typical example of justification statement:

We will continue to systematically reduce the new indebtedness in the 2014 budget, whose benchmarks we will adopt and introduce in the spring of next year. This is an essential contribution of the Federal Republic of Germany in order to fulfil to the general obligations of the European Stability and Growth Pact and of the Fiscal Treaty.

(Wolfgang Schäuble, 11 September 2012)

The passage features a reference to a policy (‘reduce indebtedness’), and a justification: clarifying that the policy is needed to fulfil to ‘the general obligations of the European Stability and Growth Pact’. The categories used for coding the policy references and justifications are based on existing studies of governments’ budgetary discourse (Green-Pedersen & Walgrave, Citation2014; Karremans & Damhuis, Citation2018). A detailed description of the main coding categories is presented in the Online Appendix (Table A2).

The justification categories highlight a distinction between partisan and governmental reasoning behind policy-making. The ‘social’ and ‘market’ categories contain arguments typical of respectively social-democratic and (neo)liberal ideologies, with the former presenting budgetary policy as a means of pursuing social justice, and the latter instead conceiving of budgets as something that should promote free markets with limited interference in private property rights and private entrepreneurship. The justification categories ‘financial’ and ‘international commitments’, instead, contain arguments featuring a more governmental vision of budgetary policy, with the former highlighting the importance of maintaining well-balanced public accounts, and the latter highlighting the commitments the government has internationally, including EU agreements such as the Stability and Growth Pact. Finally, the ‘macro-economic’ category features arguments about how budgetary policy fits in or contributes to the country’s economic performance. Justifications that would not fit any of these categories have been coded as ‘other’.Footnote1

The list of policy categories mainly serves to distinguish between increases and decreases in taxation and spending. When the justifications refer to the general budget or policy packages, these are coded respectively with the ‘general’ and ‘package’ categories. The policy packages are classified into ‘Keynesian’, ‘neoliberal’ and ‘fiscal consolidation’ according to different mixes of increases and decreases of taxation and spending. Keynesian policy packages feature increases of both taxation and expenditure, while neoliberal packages feature decreases of both. Fiscal consolidation policy packages, in turn, feature increases of taxation and decreases of expenditure, as well as explicit references to reducing debts and deficits, like in the example reported above. Finally, some of the budget speeches also feature justifications referring to actions taken at the European level, coded as ‘European policy’. These are different to the justifications coded as ‘international commitments’, wherein national policies are justified with arguments about international treaties or agreements. Arguments referring to ‘European policies’ instead justify the policies actively pursued by the government at the European level, like for instance the promotion of the EU Fiscal Compact under the second Merkel government.

This coding scheme allows for highlighting distinctions between on the one hand budget speeches presenting fiscal consolidation policies justified with arguments about financial responsibility, and on the other budget speeches presenting expansive policies justified with arguments about social justice. If the political composition of the government matters, we should observe a predominance of the former in budget speeches of the second Merkel government, and at least a partial increase of the latter in the subsequent governments.

German budgetary policies and their justifications

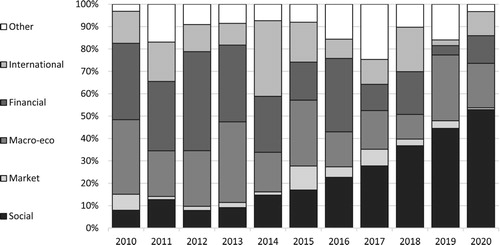

This section presents the findings from the analysis of finance ministers’ budgetary speeches between January 2010 and September 2019. The three largest justification categories featured in the eleven speeches are the social, macro-economic and financial justification categories, jointly gathering more than 70 per cent of total observations (see Online Appendix, Table A3). Justifications referring to ‘international commitments’ also feature prominently, representing more than 13 per cent of total observations. Arguments presenting policies as market-oriented are instead relatively few, amounting only to 4 per cent of the overall discourse. Finally, around 11 per cent of the justifications have been coded as ‘other’, around half of which feature arguments about how financial resources are distributed among the sub-national governments.

In terms of policies, around a third of justifications refer to the overall budget. Among policy packages the most frequently mentioned policies relate to fiscal consolidation. Among the more specific policies, most justification arguments refer to expenditure increases. The speeches also feature a surprisingly high number of justifications for policies pursued at the European level, around 15 per cent of total observations. Finally, around 6 per cent of policies have been coded as ‘other’, featuring domestic policies that do not involve taxation or spending measures.

shows the share of justifications for the individual yearly budgets. The budget speeches of the second Merkel government are strongly characterised by justifications emphasising financial responsibility and international commitments. From 2014 onwards, there is a progressive increase of socially-oriented justifications, which in the most recent speeches grow to characterise almost half of the discourse. In parallel, the ‘financial’ and ‘international commitments’ justifications are much less prominent in the speeches of Olaf Scholz than in the speeches delivered by Wolfgang Schäuble.

Figure 2. The yearly distribution of justification-categories. The order of the categories corresponds to the order of the legend (i.e., from bottom to top: ‘social’, ‘market’, ‘macro-economic’, ‘financial’, ‘international commitments’, ‘other’). Years refer to the budget years (see also Online Appendix, Table A1). Source: author's data extracted from German Finance Ministers’ budgetary speeches for budget years 2010–2020.

The change over time in the contents of budgetary discourse is also reflected in the policy-types that the justifications refer to (see Online Appendix, Table A4). When looking at specific policies and policy-packages, the picture practically reverses from the second to the fourth Merkel government. While in the speeches delivered under the second Merkel government less than 6 per cent of the discourse refers to expenditure increases, for the fourth Merkel government the share is almost 29 per cent. In parallel, expenditure reduction and fiscal consolidation packages constitute respectively 7 per cent and 8 per cent of the second Merkel government discourse, while references to these policies are practically absent in the discourse of the fourth Merkel government. The Third Merkel government, in turn, results to be a middle-ground case. On the one hand, the relative growth of socially-oriented justifications for the budgets presented between 2014 and 2017 corresponds to the social policy initiatives identified by Voigt (Citation2019). On the other hand, the persistent high share of financial justifications and references to fiscal consolidation resonate with Rixen’s (Citation2019) assessment of the overall fiscal policy approach being largely conservative.

The progression from a discourse of fiscal consolidation to an increasingly higher proportion of discourse about social justice becomes even clearer when looking more deeply into the content of the speeches. The following passage is a typical example of budgetary discourse under the second Merkel government:

We will continue our consolidation policy to reduce new borrowing in the years to come in the financial programming period. This not only allows us to comply with the requirements of the debt brake in the Basic Law, we will exceed these requirements by far. Even in this legislative period, i.e., next year, and thus three years earlier than required by the Basic Law's debt brake, the federal government can still comply with the upper limit for the federal structural deficit of 0.35 percent of gross domestic product, which will actually apply from 2016, and in subsequent years clearly lower. This means that in the coming year we will be around 24 billion euros below the deficit allowed by the Basic Law. We reduce new debt by strictly limiting expenditure growth.

(Wolfgang Schäuble, 11 September 2012)

The finance minister not only emphasises the commitment to fulfil to the requirements of the debt brake law, but also underlines the government’s intention to reduce deficits even further than what is strictly required. The policy of fiscal consolidation is therefore not only justified passively as an institutional duty, but also as an active political choice.

This discourse partially changes under the third Merkel government, featuring relatively more social justifications referring to expansive policies. This change is contemporaneous to a more favourable fiscal context (), but is also driven by the refugee crisis (see also Voigt, Citation2019). A substantial part of the socially-oriented discourse is in fact about offering assistance to asylum seekers. As this effort is distributed across different regional governments, the budget speeches also feature justifications about how resources are distributed across the subnational level, which also explains the relatively high share of justifications that were coded as ‘other’ in the speeches for the 2016 and 2017 budgets. Overall, however, commitment to national and European budgetary rules remains one of the main recurrent themes, constituting more than 20 per cent of the overall discourse of the third Merkel government.

In the speeches of the fourth Merkel government, delivered by the Social Democrat Olaf Scholz, the emphasis on social objectives becomes dominant, featuring for example the following passage about the importance of extending the German childcare benefit ‘Gute-KiTa-Gesetz’:

One of the things we need to get underway, which we have prepared in the Federal Government, which is now up for decision and for which we have made provision in this budget, is that we want to do something for the children who are growing up in this country. The Gute-KiTa-Gesetz is not only a good quality law that we will discuss, but it is also something that we can finance and that we will finance. We must make sure that the conditions for the children growing up in this country are as good as possible, and we must help ensure that their parents have good childcare conditions for their children. Therefore, the Gute-KiTa-Gesetz is an important milestone, an impetus from the federal government to improve together with states and communities, the situation of children in Germany.

(Olaf Scholz, 11 September 2018)

Besides emphasising its social policy priorities, the social-oriented discourse of Olaf Scholz commits the government to substantial expenditure increases, particularly in the speech presenting the 2020 budget. The following passage, for instance, presents the government’s plan to provide €40 billion for social housing:

We have ensured that social housing, which is so important in Germany, does not end next year; we have changed the Basic Law so that social housing can also take place in the 2020s. I say here: we will support social housing with many billions from the federal budget in the next few years.

(Olaf Scholz, 10 September 2019)

Compared to the previous two cabinets, the budget speeches delivered under the fourth Merkel government feature concrete intentions to increase social expenditure. These proposals, in turn, are justified with active political arguments emphasising the cabinet’s will to improve social standards. Considering the similarities with the previous government in terms of the partisan composition of the coalition and the financial context, the increase in socially-oriented discourse seems to be driven by the change of partisanship in the finance ministry.

The period of both the third and fourth Merkel governments coincides with a context of increasing fiscal surplus (), which may have facilitated the progressive growth of socially-oriented discourse shown in . However, the increase between the two governments seems to outweigh the confounding effect of the surplus. reports estimated associations between the shift from Third to Fourth Markel government and the share of socially-oriented justifications in budgetary discourse based on OLS regression models. Model 1 indicates that under the fourth Merkel government, the estimated share of socially-oriented discourse is 22 percentage points higher compared to the third Merkel government. Model 2 shows that the estimated increase also remains substantial at 14 percentage points after controlling for the size of fiscal surplus in the year preceding each budget year. The estimates are statistically significant at the 95 per cent level. The findings indicate that even though the availability of more financial resources facilitated more socially-oriented discourse, only a small part of the observed increase in the speeches of Olaf Scholz can be explained by the size of fiscal surplus.

Table 1. OLS models estimating association between shift in Finance Ministry and the share of socially-oriented justifications

It should also be noted that some of the observed increase in social justifications might stem from increased attention to climate-related concerns in the public debates over recent years. In fact, in a few cases socially-oriented discourse is narrowly related to (international) environmental concerns (see also footnote 1). The models have therefore been replicated with the exclusion of climate-related justifications from the ‘social’ category. The estimates are largely similar, confirming the budget discourse of Olaf Scholz to be more sensitive to domestic social concerns than that of his predecessor.

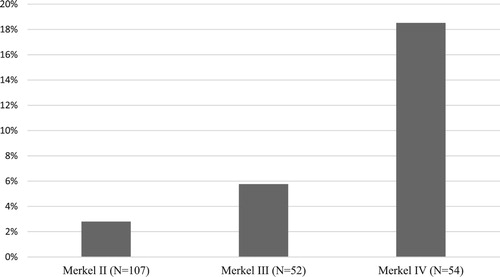

From a domestic perspective, the increase of socially-oriented discourse under the fourth Merkel government seems to be largely driven by the partisan change in the finance ministry. However, from a European point of view, an important external factor to be taken into consideration are the Semester’s CSRs, which from 2014 onwards have urged German governments to increase domestic expenditure (D'Erman et al., Citation2019; Zeitlin & Vanhercke, Citation2018). As anticipated in the Introduction, the contents of CSRs are to a great extent the result of negotiations between finance ministers (Maricut & Puetter, Citation2018). Therefore, before proceeding with the investigation of the interaction between European pressures and national budgetary discourse, it is important to highlight that the discourse of Olaf Scholz also strongly differs from that of Wolfgang Schäuble with regards to justifications for the government’s policy at the EU level. shows the percentage of social-oriented justifications referring to ‘European policy’ for each government. Compared to the preceding two cabinets, the discourse of the fourth Merkel government stands out, as its social commitments are also expressed in relation to European policies.

Figure 3. Share of socially-oriented justifications for ‘European policies’, by government. Source: author's data extracted from German Finance Ministers’ budgetary speeches for budget years 2010–2020.

As the early 2010s was a particularly intense period in terms of European governance reforms, the second Merkel government features 107 of the total 213 justifications referring to ‘European Policy’ over the eleven budget speeches, while the other 106 are split between the third (52) and fourth (54) Merkel governments (see also Online Appendix, Table A3). As a result, almost 18 per cent of the budgetary discourse of the second Merkel government is about actions taken at the European level. For the third and fourth Merkel governments, the percentages are respectively 11 per cent and 14 per cent (Online Appendix, Table A4). The references to European policies in the speeches of the second Merkel government confirm the commitment to promote fiscal discipline at both the national and the European level (see also Schoeller, Citation2017; Wasserfallen & Lehner, Citation2017). Ensuring ‘solid public finances’ both domestically and in other EU member states is presented as functional to both Germany’s economic growth and the stabilisation of the Eurozone. Under the third Merkel government, the arguments referring to actions taken at the European level are less frequent, but are still characterised by the theme of fiscal discipline.

Under the fourth Merkel government, the share of discourse about European policies increases again, but features different political objectives. When Olaf Scholz presents the government’s action at the European level, the discourse is much more focused on achieving social goals. In contrast to Schäuble’s speeches, in which European policy is mostly referred to in relation to the need of promoting fiscal discipline, Scholz’s speeches refer to European policy largely in relation to the importance of international collaboration for tackling international tax avoidance and meeting popular demand for social and environmental standards. In German budget speeches, EEG is thus not always portrayed as an external constraint. On the contrary, the speeches of the second and fourth Merkel governments strongly suggest that the European level is also an arena in which domestic partisan political preferences can be asserted.

National budgets and European recommendations

An important novelty of the new EEG is the intensified feedback loop between the national and European levels in the preparation of governments’ budgets (Verdun & Zeitlin, Citation2018). Through the European Semester, national governments prepare a national reform plan that is evaluated by European institutions. On the basis of a series of reports, in turn these institutions develop the CSRs that national governments need to take into consideration when preparing the upcoming budget (Maatsch & Cooper, Citation2017). In the Semester’s process, national budgets receive a European input from the CSRs, and the CSRs receive a national input from the national reform plans. This circularity entails that political decisions about the budgetary policy approach can originate both from the national and the European level. In addition, the process of formulating CSRs is strongly influenced by ECOFIN, among which the German finance minister is one of the most powerful actors (Engelen, Citation2018; Maricut & Puetter, Citation2018; Streeck, Citation2019; Wasserfallen et al., Citation2019).

Previous literature shows how the European endorsements of fiscal consolidation at the beginning of the 2010s were largely driven by Germany’s policy advocacy (Schoeller, Citation2017; Wasserfallen et al., Citation2019). During the first years of the European Semester – which coincided largely with the height of the Eurozone crisis – the German government’s political preferences have driven both the domestic policy course as well as the content of the European policy-pressures. The analysis of budget speeches and CSRs presented here reveals that during the years of the second Merkel government (2010–2013), the CSRs are not only in line with policy proposals presented in national budget speeches, but they explicitly endorse Schäuble’s policy of fiscal consolidation aimed at reducing Germany’s debt levels. The CSR of 2012 praised the government’s initiatives in this regard by stating, for instance, the following:

Continue with sound fiscal policies (…), implement the budgetary strategy as envisaged, ensuring compliance with the expenditure benchmark as well as sufficient progress towards compliance with the debt reduction benchmark (Council of the European Union, Citation2012).

During the years of the third Merkel government, the content of CSRs changes substantially. The CSRs of 2014 are the last ones explicitly endorsing the continuation of the fiscal consolidation policy, and are at the same time the first that explicitly urge the government to ‘use the available scope for increased and more efficient public investment in infrastructure, education and research’ (Council of the European Union, Citation2014). This urge became the priority in the CSRs of the following years. Following these pressures for more expenditure, a certain switch in the national budgetary discourse can be observed, with for example an increasing share of justifications referring to expenditure increases (Online Appendix, Table A4). In the parliamentary speech presenting the 2016 budget, for instance, the finance minister emphasises that the funds for research and education are to be increased by €1.1 billion (Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundestag, 8 September 2015). The following year, the finance minister asserts that no other country in Europe invests as much in research and development as Germany (Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundestag, 6 September 2016). Despite these announcements, Germany’s expenditures continued not to make full use of the fiscal space available (Rixen, Citation2019). The prudent policy course is legitimised by Wolfgang Schäuble with the claim that ‘the soundness of our fiscal policy has contributed significantly to the return of trust after the great crisis’ (Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundestag, 6 September 2016). Differently than during the years of the second Merkel government, the European recommendations in the years of the third Merkel government are not endorsements for policies that have already been undertaken, but are instead encouragements to change the prudent budgetary policy course.

The 2018 CSRs continue to encourage the government to ‘use fiscal and structural policies to achieve a sustained upward trend in public and private investment, and in particular on education, research and innovation at all levels of government, in particular at regional and municipal levels’ (Council of the European Union, Citation2018). In the subsequent budget speech of September 2018, Olaf Scholz emphasises the government’s intentions to increase expenditure. Among the ‘macroeconomic’ justification statements, for instance, the finance minister particularly underlines the investments made in the development of digital infrastructure (Olaf Scholz, Bundestag, 11 September 2018). The 2019 European recommendations restate the need to invest in education, research and infrastructure for innovation. In addition, in contrast to previous CSRs, they also specifically urge the government to provide funds for ensuring the provision of affordable housing (Council of the European Union, Citation2019). In the following budget speech of September 2019, Olaf Scholz presents the funding plan for social housing.

Apart from being one of the most important measures introduced in the 2020 budget (Bundesregierung, Citation2019), the funding plan for social housing is also one of the policies which Olaf Scholz has flagged to discontented parts of the party base, presenting it as a social-democratic success (ARD, Citation2019). Yet the presence of the proposal in the 2019 CSRs seems to suggest that the shift to a more expansive policy agenda in the fourth Merkel government’s budget speeches is not driven by partisan change within the cabinet, but rather by the feedback-loop between European CSRs and domestic budgetary policy. It is therefore important to trace whether the proposal originated from the European side of the Semester’s feedback loop, or from domestic political initiatives.

Among the European documents of the Semester’s feedback loop, Germany’s social housing shortage is discussed for the first time in the country report of 27 February 2019, in which the Commission’s staff discusses the country’s ongoing progress with regards to structural reform and the correction of macroeconomic imbalances. In the section discussing social policy, the following assessment is made:

Housing costs in large cities put older and poorer people at greater risk of poverty. (…) The Federal Government’s financial initiative to make 100,000 additional units of social housing available thus appears very timely (European Commission, Citation2019b, p. 43).

The federal government intends to start a housing offensive. The goal is that 1.5 million apartments and homes in this legislative period will be built with public funding (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, Citation2018).

The German experience during the first decade of the European Semester underlines the relevance of the finance ministry’s political preferences for the extent to which CSRs are pursued. The European CSRs and the policy proposals presented in national budget speeches were largely in line during the years of the second and fourth Merkel governments, and to some extent divergent during the years of the third Merkel government. In the case of the Second Merkel government, the parallels between domestic discourse and European CSRs are at least partially the result of the German leadership role in reforming EEG during the Eurozone crisis (Schoeller, Citation2017; Wasserfallen et al., Citation2019). The subsequent ‘socialisation of the European Semester’ (Zeitlin & Vanhercke, Citation2018) ran against the preferences of the Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble who, also during the years of the Merkel III government (2013–2017), kept reminding the German parliament of the importance of fiscal prudency. When the Social Democrat Olaf Scholz took leadership of the finance ministry, not only did the socially-oriented CSRs find more domestic endorsement, but domestic social policy initiatives were incorporated in the CSRs.

Political alternatives under European economic governance

The empirical evidence presented in this paper shows how European policy pressures and domestic politics are simultaneously at work in national budgetary policy-making. Through the European Semester, European institutions oversee that governments do not overspend when there are relatively high levels of deficits or debts, and that they reinject public resources in the domestic economy once the government starts running surpluses (Verdun & Zeitlin, Citation2018). At the same time, the rotation of political forces in government impacts upon the strength with which European policy recommendations are pursued, and upon the more specific destinations of expenditures or retrenchments. In addition, the domestic political forces – particularly those leading the finance ministry – can also influence the policy content of the European recommendations. This can be done, for example, by strongly advocating at the European level for a specific policy course, or through policy initiatives that are subsequently endorsed by the CSRs. These findings confirm the powerful role of finance ministers in the governance of the European Semester (Maricut & Puetter, Citation2018). They also confirm the idea that national governments ‘cherry-pick’ European policy pressures according to their political preferences (Eihmanis, Citation2018).

The relevance of the political preferences of the governing parties entails that, in a financially stable country like Germany, under the new EEG governments of different partisan composition can pursue alternative policies. Despite the long shadow of the domestic debt-brake law and the zero-deficit rule, the alternation in the finance ministry between the CDU and the SPD produced a change in the strength and modalities with which the European pressures for increasing domestic expenditure have been pursued and implemented. The fact that under the third and fourth Merkel governments fiscal output continued to be relatively prudent () is not attributable to European constraints, but rather to the domestic rules severely constraining the extent to which domestic expenditure can be increased. In addition, for various years the importance of these rules has been strengthened by the political beliefs of both Christian – and social-democratic elites (Bremer, Citation2019; Rixen, Citation2019). Even Olaf Scholz was originally an advocate of fiscal prudency and the debt-brake law (Streeck, Citation2019). The grass-roots discontents from within the SPD, however, increasingly pressured the party’s elites to loosen their fiscal prudency beliefs, which resulted in Olaf Scholz recently announcing that the zero-deficit rule might be broken in the upcoming years (Spiegel Online, Citation2019). In the meantime, the government has committed itself to a consistent package of new expenditures (Bundesregierung, Citation2019).

The sequence of events shows that domestic political dynamics can have a significant impact upon the country’s domestic socio-economic policies, as well as on the policy stances advocated by the government at the European level. The extent to which governments of different partisan composition can pursue alternative socio-economic policies, however, is also contingent upon the country’s relative strength within the European institutional framework. In Germany, the latter has turned out to be less constraining than domestic budgetary rules. Despite the most recent expenditure commitments, the zero-deficit rule is still preventing German governments from increasing public spending beyond the revenue level. At the same time, the findings presented in this paper suggest that further alternation in the government’s composition can lead to greater shifts in its budgetary policy.

Finally, the findings of this paper also scale back the dominant role that is often ascribed to austerity in relation to current socio-economic policy in Europe (Schäfer & Streeck, Citation2013). Rather than an inescapable policy paradigm, the austerity of the early 2010s seems rather to be a political initiative that is confined to the timeframe of the Eurozone crisis and its immediate aftermath. The findings therefore strongly suggest that the preferences of the political parties entering national governments and the leverage these governments have in the European decision-making process are bound to be determinant factors for the extent to which austerity or another policy approach will dominate socio-economic policy-making in the next decade.

Statistical replication materials and data

Supporting data and materials for this article can be accessed at: https://www.uni-salzburg.at/index.php?id=212556. Replication materials:.dta file containing originally collected data from German budget speeches 2009–2019;.do file containing syntax for and the Tables in the Online Appendix. The webpage also provides information on the related research project.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (20.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the colleagues at the Political Science Department of the University of Salzburg for hosting the project ‘A Comparative Study of Budgetary Discourse in the Eurozone’, funded by the Austria Science Fund. Special thanks to Professor Zoe Lefkofridi for her mentorship, and to the student assistants Arabella Karetta and Klaudia Koxha. The author would like to thank also Troy Broderstad for commenting on an earlier draft presented at the 2019 ECPR General Conference and the journal’s two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions. Any mistakes remain the author’s own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johannes Karremans

Johannes Karremans is a post-doctoral researcher at the Political Science Department of the University of Salzburg, Austria.

Notes

1 N.B. The author’s original coding also featured distinct categories for environmental concerns and security (i.e. military). As these statements constituted respectively 1.4% and 1.8% of the total observations, for illustrative purposes in this paper the former have been merged with the ‘social justifications’, and the latter with the category ‘other’. Various checks have shown that this paper’s main findings are not affected by the categorisation of these sets of observations (see e.g. ).

References

- ARD. (2019). Die Notregierung - Ungeliebte Koalition. ARD Mediathek.

- Barber, T. (2019). SPD result heralds the end of Germany’s ‘grand coalition’. Financial Times, 1 December.

- Bremer, B. (2019). The political economy of the SPD reconsidered: Evidence from the great recession. German Politics, 0(0), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2018.1555817

- Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie. (2018). Nationales Reformprogramm, April 2018.

- Bundesregierung. (2019). Sozialer Zusammenhalt und Rekordinvestitionen. Available at: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/bundeshaushalt-2020-1669496 (accessed 7 January 2020).

- CDU/CSU. (2017). Für ein Deutschland,in dem wir gutund gerne leben. Regierungsprogramm 2017–2021.

- Council of the European Union. (2012). Recommendation for a Council Recommendation on the 2012 National Reform Programme of Germany and delivering a Council opinion on the 2012 Stability Programme of Germany, 10 July 2012.

- Council of the European Union. (2014). Recommendation for a Council Recommendation on the 2014 National Reform Programme of Germany and delivering a Council opinion on the 2012 Stability Programme of Germany, 8 July 2014.

- Council of the European Union. (2018). Recommendation for a Council Recommendation on the 2018 National Reform Programme of Germany and delivering a Council opinion on the 2018 Stability Programme of Germany, 15 June 2018.

- Council of the European Union. (2019). Recommendation for a Council Recommendation on the 2019 National Reform Programme of Germany and delivering a Council opinion on the 2019 Stability Programme of Germany, 2 July 2019.

- Crum, B. (2018). Parliamentary accountability in multilevel governance: What role for parliaments in post-crisis EU economic governance? Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363270

- D'Erman, V., Haas, J., Schulz, D. F., & Verdun, A. (2019). Measuring economic reform recommendations under the European semester: ‘One size fits all’ or tailoring to member states? Journal of Contemporary European Research, 15(2), 194–211. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v15i2.999

- Doray-Demers, P., & Foucault, M. (2017). The politics of fiscal rules within the European Union: A dynamic analysis of fiscal rules stringency. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(6), 852–870. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1296883

- Eihmanis, E. (2018). Cherry-picking external constraints: Latvia and EU economic governance, 2008–2014. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363267

- Engelen, K. C. (2018). The dismantling of Angela Merkel. The International Economy, 32(1), 46–51.

- European Commission. (2019a). Numerical fiscal rules in EU member countries. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/indicators-statistics/economic-databases/fiscal-governance-eu-member-states/numerical-fiscal-rules-eu-member-countries_en (accessed 6 January 2020).

- European Commission. (2019b). Country Report Germany 2019, Commission Staff Working Document, 27 February 2019.Financial Times. 2019. ‘SPD Result Heralds the End of Germany’s “Grand Coalition”’. 1 December 2019.

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Walgrave, S. (2014). Agenda setting, policies, and political systems: A comparative approach. University of Chicago Press.

- Hertner, I. (2018). Centre-left parties and the European Union. Manchester University Press.

- Hübscher, E. (2019). The impact of coalition parties on policy output – evidence from Germany. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 25(1), 88–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2019.1570599

- Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (eds.). (2019). European party politics in times of crisis. Cambridge University Press.

- John, P., Bertelli, A., Jennings, W., & Bevan, S. (2013). Policy agendas in British politics. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Karremans, J., & Damhuis, K. (2018). The changing face of responsibility: A cross-time comparison of French social democratic governments. Party Politics, Online First, 135406881876119. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818761197

- Laffan, B. (2014). Testing times: The growing primacy of responsibility in the Euro Area. West European Politics, 37(2), 270–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887875

- Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of democracy. Yale University Press.

- Maatsch, A., & Cooper, I. (2017). Governance without democracy? Analysing the role of parliaments in European economic governance after the crisis: Introduction to the special issue. Parliamentary Affairs, 70(4), 645–654. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsx018

- Mair, P. (2013). Bini Smaghi vs. The parties: Representative government and institutional constraints. In A. Schäfer & W. Streeck (Eds.), Politics in the Age of Austerity (pp. 143–168). Polity Press.

- Maricut, A., & Puetter, U. (2018). Deciding on the European Semester: The European Council, the council and the enduring asymmetry between economic and social policy issues. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363271

- Matthijs, M. (2017). Integration at what Price? The erosion of national democracy in the Euro Periphery. Government and Opposition, 52(2), 266–294. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2016.50

- Rixen, T. (2019). Administering the surplus: The grand coalition’s fiscal policy, 2013–17. German Politics, 28(3), 392–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2018.1488245

- Ruiz-Rufino, R., & Alonso, S. (2018). Democracy without choice: Citizens’ perceptions of government’s autonomy during the Eurozone crisis. In W. Merkel, & S. Kneip (Eds.), Democracy and Crisis: Challenges in Turbulent Times (pp. 197–226). Springer International Publishing.

- Schäfer, A., & Streeck, W. (2013). Politics in the age of Austerity. Polity Press.

- Scharpf, F. W. (2015). Political legitimacy in a non-optimal currency area. In O. Crammer, & S. Hobolt (Eds.), Democratic Politics in a European Union Under Stress (pp. 19–47). Oxford University Press.

- Schild, J. (2013). Leadership in hard times: Germany, France, and the Management of the Eurozone crisis. German Politics and Society, 31(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.3167/gps.2013.310103

- Schmidt, M. G. (1995). The parties-do-matter hypothesis and the case of the federal republic of Germany. German Politics, 4(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644009508404411

- Schoeller, M. G. (2017). Providing political leadership? Three case studies on Germany’s ambiguous role in the eurozone crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1146325.

- SPD. (2017). Zeit für mehr Gerechtigkeit. Unser Regierungsprogramm für Deutschland.

- Spiegel Online. (2019). Finanzminister: Scholz kann sich Abkehr von schwarzer Null vorstellen. 11 December.

- Streeck, W. (2019). Europe under Merkel IV: Balance of Impotence. American Affairs, 2(2), 162–192.

- Veen, A. v. d. (2011). Ideas, Interests and Foreign Aid. Cambridge University Press.

- Verdun, A., & Zeitlin, J. (2018). Introduction: The European Semester as a new architecture of EU socioeconomic governance in theory and practice. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363807

- Voigt, L. (2019). Get the party Started: The social policy of the grand coalition 2013–2017. German Politics, 28(3), 426–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2019.1585810

- Wasserfallen, F., & Lehner, T. (2017). Mapping Contestation on Economic and Fiscal Integration: Evidence from New Data. EMU Choices working paper (University of Salzburg): 23.

- Wasserfallen, F., Leuffen, D., Kudrna, Z., & Degner, H. (2019). Analysing European Union decision-making during the Eurozone crisis with new data. European Union Politics, 20(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518814954

- Zeitlin, J., & Vanhercke, B. (2018). Socializing the European Semester: EU social and economic policy co-ordination in crisis and beyond. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363269