ABSTRACT

Since the Lisbon Treaty National Parliaments (NPs) can play a formal role in the Ordinary Legislative Procedure (OLP). One of the complexities of this legislative process is that the formal decisions are pre-negotiated in informal trilogues between the Council, the European Parliament (EP) and the European Commission. NPs have no role to play in trilogues, and have difficulties accessing information discussed in trilogue meetings, hindering MPs to hold their national government to account for decisions made in the Council. This article explores whether NPs monitor trilogue negotiations, and, if so, how and why do they do this. The empirical material is collected through semi-structured interviews with actors from several NPs and a content analysis of debates in two Member States. The results show that NPs operate in a formal and informal institutional context, both at the EU and national level. These institutional arrangements are used by MPs to lower costs of collecting information on trilogue negotiations in order to be able to hold the government to account and to steer the negotiation position of the government in the direction of their own policy positions. However, the increased attention for trilogue negotiations by NPs cannot alleviate the phenomenon of domestic de-parliamentarization.

Introduction

The role of parliaments in the European Union (EU) has been transformed substantially in the last decades. For the European Parliament (EP), the Maastricht and Amsterdam treaties can be seen as ‘watershed’ moments because of the introduction of the co-decision procedure, turning the EP into one of the main actors in EU decision-making (Ripoll Servent, Citation2018). Subsequently, the adoption of an act in first reading became the ‘way to go’ for nearly all legislative files (De Ruiter & Neuhold, Citation2012), a development spurred by the Lisbon Treaty extending co-decision to 85 Treaty articles. These early adoptions are preceded by informal trilogues between the Commission, the EP and the Council (Brandsma, Citation2015, p. 300). For National Parliaments (NPs) it was not until the Lisbon Treaty that their role has been formally recognized in EU affairs. This Treaty provided NPs with new tools, for example through the Early Warning System (EWS), which turned them into ‘watchdogs’ of subsidiarity, involving them directly in the agenda-setting phase of the EU legislative process.

At the same time, NPs have raised concerns on the extent to which they are able to hold their national government to account for decisions made in the Council on legislative proposals, especially in light of the exponential growth of early agreements through informal trilogues (COSAC, Citation2009, p. 9). The European Ombudsman took this up in an own initiative inquiry on trilogues, stressing that ‘NPs must be empowered to exercise democratic scrutiny of the positions their governments take in the course of the EU legislative process’ (European Ombudsman, Citation2015, p. 5). Clearly, insight into trilogue negotiations is seen as a necessary condition for NPs to hold the government to account for decisions made in the Council.

More generally, the need to involve NPs in the European integration process stems from the idea that parliamentarization at the EU level – through the establishment of the EP – does not suffice to legitimize European integration. It should be accompanied by strong NPs holding the national executive branch to account when taking decisions at the EU level (see for example Bellamy & Kröger, Citation2014). The low turnout in EP elections and the – by and large – stable and high turnout in elections for NPs indeed show that a vast majority of the public in EU member states considers NPs to be the main representative bodies in Europe. NPs can be considered to provide a link between secluded high-level bargaining and domestic audiences (Lindseth, Citation2010). At the same time, because national governments represent their countries in EU negotiations informational asymmetries arise between the executive branch and the legislature. As a result, NPs were often labelled as ‘victims’ or ‘latecomers’ to the European integration process (Auel & Benz, Citation2005; O'Brennan & Raunio, Citation2007; Raunio, Citation2011). The discrepancy between the need for parliamentary control at the national level and the inability of NPs to control the national executive branch in the complex EU legislative process seriously undermines the legitimacy of the representative democratic system in Europe, with de-parliamentarization as a result (Maurer & Wessels, Citation2001; but see Karlsson & Persson, Citation2018).

While academics have shed light on the extent of de-parliamentarization in the EU in general terms, we know very little about whether the potential lack of engagement by NPs with trilogues aggravates this ‘de-parliamentarization’. We contribute to this debate by asking the following, mainly, explorative research questions: First, do NPs try to shed light on what goes on in trilogues at all? Secondly, if so, how do they do this; can we discern certain strategies that NPs adhere to? Thirdly, can we explain why certain strategies are adopted by NPs to hold their respective government to account? This then leads us to answering the question driving this research: to what extent these endeavours by these representative bodies at the national level contribute to alleviating the (alleged) phenomenon of ‘de-parliamentarization’?

The set-up of this article is as follows: we first provide a brief insight into the transformation of the roles of NPs within EU affairs and the changing nature of trilogues. In a second step, we review the literature on the role of trilogues in the EU legislative process and the engagement of NPs with EU affairs. This enables us to identify three distinct points of departure for our empirical enquiry, i.e., (i) the criticism voiced by scholars on the secluded nature of trilogues, (ii) the difference between NPs of EU member states how progress of EU legislative processes is monitored in general, and (iii) the experience with the Lisbon tools and its possible impact on how NPs deal with negotiations in trilogues. We then present our empirical findings obtained through semi-structured interviews and content analysis of parliaments documents. We conclude by explaining different patterns of parliamentary behaviour and discussing the normative implications of our findings.

The transformation of NPs and trilogues in the EU

NPs after Lisbon

Article 12 of the Lisbon Treaty formally recognizes that NPs ‘contribute actively to the good functioning’ of the Union. As such, the Treaty has been coined as the ‘Treaty of parliaments’ (Lammert, Citation2009), as it not only extends the co-legislative role of the EP further (Ripoll Servent, Citation2018) but also foresees a number of provisions by way of which NPs can become active collectively. Here the most notable example is the Early Warning System, which turns national legislatures into ‘watchdogs’ of the subsidiarity and proportionality principle (see for details: e.g., Cooper, Citation2006). Another example of collective parliamentary activity within the EU arena is inter-parliamentary co-operation (IPC) (Kreilinger, Citation2013).

The Lisbon tools for NPs supplement existing systems of parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs at the national level. While the control of the national executive branch is still seen as key (COSAC, Citation2013, p. 15), scrutiny provisions at the domestic level are far from uniform. NPs all have set up one or more European Affairs Committees (EAC), but differences still prevail when it comes to the involvement of sectoral committees in EU affairs (Hefftler et al., Citation2015). One also finds variation with regard to the scrutiny approach. Although the ‘addressee’ of the scrutiny procedure is, in the end, always the government, systems are different with regard to whether parliament scrutinize EU documents or the governmental negotiating position in the Council (or both). Moreover, in some cases, the government is under a legal obligation to follow the position of their parliaments in EU negotiations. In many cases, however, parliaments can only give their opinion or provide instructions without this having a binding effect on the government. Furthermore, a number of parliaments have established so-called ‘scrutiny reserves’ which is to ensure that no decision is taken at the EU level without parliamentary involvement at the national level (Auel & Neuhold, Citation2017a, p. 14).

Trilogues: informal fora in transformation

Trilogues have become part and parcel of the EU legislative process over the last two decades, enabling the passing of EU legislation at early stages of the OLP (Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, Citation2015, p. 1152). As opposed to the role of NPs in EU affairs, trilogue meetings have no basis in the treaties, take place behind closed doors, and involve only a sub-set of actors from the EP (i.e., the rapporteur and shadow rapporteurs), the European Commission, and the Council (i.e., the member state in the rotating presidency of the Council). The EP’s rules of procedure stipulate that EP negotiators are required to report back to the EP Committee after each trilogue meeting, but in practice this hardly ever takes place (Brandsma, Citation2019).

State of the art: NPs and trilogues

We aim to explore answers to three inter-linked questions. First, do NPs try to shed light on what goes on in trilogues at all? Secondly, if so, how do they do this; can we discern certain patterns? Thirdly, why do NPs pay attention to trilogues, and why do they pay attention in a certain way? Although our research has primarily an inductive character, there are several insights from the scholarly literature on NPs and the literature on trilogues which can function as a point of departure for our empirical inquiry. As such we can identify three categories of general themes. A first theme concerns the criticism voiced when it comes to the secluded nature of political trilogues and its negative consequences for transparency, quality of the adopted legislation and democratic legitimacy (see for example Rasmussen & Reh, Citation2013; Ripoll Servent & Pannning, Citation2019). When one accepts that ‘the availability of information is an important element of meaningful democratic accountability’ (Bovens, 2007; quoted in Brandsma, Citation2019), trilogues are often perceived as opaque fora empowering an elite of decision-makers. Information is ‘the currency of power in Brussels’, often has to be obtained via informal sources – i.e., through one’s own network of contacts – and it is difficult to keep track of during trilogue negotiations, particularly towards the end of a file (Greenwood & Roederer-Rynning, Citation2019, p. 321). Hence, trilogues can, due to limited information on how decisions are made, deprive the general public of the opportunity to scrutinize their representatives in the EP (Brandsma, Citation2019).

Scholars working on NPs in an EU context share the criticism on trilogues as secluded arenas. De Ruiter (Citation2013) shows that when it comes to information collection on decisions made in trilogues, there are high costs involved for NPs, due to the opaque nature of trilogues and limited capacity of NPs (De Ruiter, Citation2013). At the same time, MPs are unlikely to perceive the benefits to be high – in terms of influencing policy, gaining votes or holding on to office – of holding governments to account for decisions made in trilogues (Curtin & Leino, Citation2017; De Ruiter, Citation2013; Jensen & Sindbjerg Martinsen, Citation2015). However, it does not become clear from the literature whether NPs still do not engage with trilogues because of a negative cost–benefit balance, now that it has become the ‘standard’ way for reaching agreement between the Council and the EP.

A second general theme we can derive from the scholarly literature and that can function as a starting point for our empirical enquiry is the difference between NPs of EU member states in how these representative bodies monitor the progress in EU legislative processes (Karlsson & Persson, Citation2018; Raunio & Hix, Citation2000; Winzen, Citation2012). First, the scope of information rights varies greatly between parliaments, with some having only weak, informal or incomplete access to EU documents, parliaments receiving all legislative proposals that fall within their remit of responsibility, and other parliaments with rights to hold hearings and access additional background material (Winzen, Citation2012). Second, parliaments devote their resources to the processing of information differently, e.g., by the institutionalization of specialized European Affairs Committees, the involvement of the expertise of sectoral committees, or through a scrutiny reserve. Third, parliaments vary on the use of mandating or resolution rights to impose parliamentary positions on government. In some cases, resolutions have no formal effect on government, or governments may deviate but only with justification, or resolutions are binding or quasi-binding (Hoerner, Citation2017; Winzen, Citation2012).

This brings us to the third theme we identify in the literature: the burgeoning scholarly debate on the role of NPs after the Lisbon Treaty. The Treaty provisions on the EWS and IPC are seen to steer NPs away from exercising key legislative functions at the domestic political level, such as controlling the government and connecting to citizens (Bellamy & Kröger, Citation2014; De Wilde, Citation2012), and turn NPs into gatekeepers, networkers, and unitary scrutinizers (Auel & Neuhold, Citation2017b; Sprungk, Citation2013, p. 548). It is in the very nature of the Lisbon provisions on NPs that a certain degree of coordination between NPs is needed, for example, to raise subsidiarity concerns. A network of liaison officers – unelected officials of NPs that are delegated to Brussels for several years – is seen as the most routine channel of communication between parliaments (Neuhold & Högenauer, Citation2016, p. 251). NPs have engaged with the Lisbon tools in the past decade, and have come to realize their limits (Auel & Neuhold, Citation2017a). However, questions around the use of the Lisbon tools and effectiveness are still at the forefront of discussions, both among scholars, as well as among MPs and parliamentary staff.

Data and methods

The empirical material needed to answer the three research questions is obtained through 17 semi-structured interviews with representatives of a large number of NPs, i.e., liaison officers, MPs and EU advisors of NPs. We used the themes we identified in the literature as starting points for our empirical enquiry to structure the interviews. The interview protocol is included in the online appendix. Moreover, we do not want to treat NPs as monolithic actors and, hence, also aim to shed light on whether something happens – and if so what happens within NPs. We conducted a content analysis of more than 200 parliamentary documents from the Austrian and Dutch parliament (including minutes of plenary debates, oral and written questions, resolutions, motions, and minutes of committee meetings).

We coded all parliamentary documents with a reference by MPs to trilogues or synonyms in the Upper and Lower Houses for the period 1997–2018.Footnote1 For each reference the name of the MP and the party were recorded, as well as the topic of the intervention (Winzen et al., Citation2018), and the extent to which MPs give the government a ‘hard time’ by (i) communicating a position, (ii) asking a question, (iii) presenting an alternative position to the position of the government, or (iv) providing explicit negotiating instructions to the government (Smeets & De Ruiter, Citation2019). The Austrian and Dutch parliaments were selected because they are, respectively, examples of parliaments with and without a mandating system. This difference in how the NPs of the member states deal with EU affairs can possibly shed light on how differences in scrutiny and oversight instruments play a role in monitoring and influencing trilogue negotiations, i.e., the second general theme identified as point of departure for our empirical enquiry. Beyond the difference between mandating and non-mandating systems, both parliaments also differ when it comes to their scrutiny practices of EU affairs. Whereas the Dutch parliament selects about 80 ‘priority dossiers’ on an annual basis, the Austrian parliament has an administrative unit that conducts a ‘pre-check’ for subsidiarity concerns. Moreover, whereas the Dutch parliament drives on great involvement of – and decentralization to – sectoral committees (Högenauer & Neuhold, Citation2015), in the Austrian parliament, the European Affairs Committee (EAC) plays a central role (Miklin, Citation2015).

Results

As explained in the introduction, the main aim of this article is to explore the (possibly) varying engagement of NPs with trilogues and as such we have broken this down into three questions. With regard to the first question of whether NPs try to shed light on what goes on in trilogues, our empirical results show that NPs have difficulty finding out what is discussed and decided in trilogues, mirroring the criticism voiced by scholars on the secluded nature of trilogues (see section 3). One of the interviewees stated that ‘trilogues are an even blacker box than the meetings of working groups of the Council’ (I7). Several interviewees indicated that the dates when trilogues are taking place are often not known among the liaison officers of NPs in Brussels (I1;3;4;I7;I9). NPs have to trace the development of the negotiations themselves, often through keeping elaborate time-lines. Several interviewees indicated how difficult this is, especially because all NPs focus on moments before and after Council meetings to hold the government to account, and not before or after trilogue meetings. The timing of the Council meetings and trilogue meetings are not in sync and therefore trilogues are often ‘off the radar’ of MPs. Some MPs even do not want to receive information on trilogue negotiations because it interrupts the flow of information and the focus of MPs on holding the government to account before and after Council meetings (I10; I5; I15).

Several of our interviewees linked the lack of transparency surrounding trilogues to the observation that the EP does not view it in its interest to open up the trilogues for NPs (I7; I2), and that contacts between MEPs and MPs from the same party or member state are hardly used to share information on trilogue negotiations (I17). Some interviewees perceived this as a deliberate attempt by MEPs to keep NPs out of the trilogues (I7; I2). Others disagreed with this interpretation by stating that simply the timing of the debates in NPs and the EP is often not in sync (I6; I17).

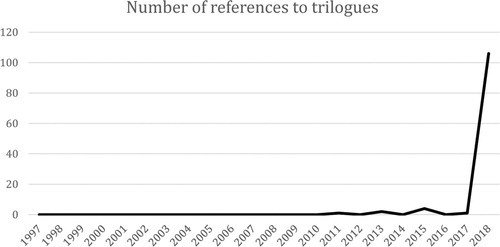

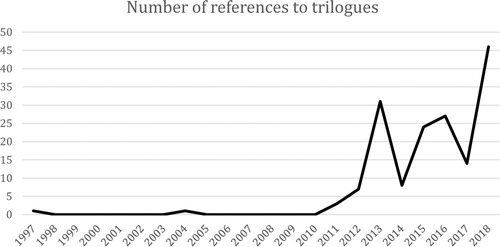

Despite the barriers for NPs to find out what is discussed in the trilogues, we do find in the Austrian and Dutch cases that trilogues receive attention. This is apparent from the minutes of plenary and committee meetings and from oral and written questions. As can be seen in and , the number of references to trilogues in debates increased after 2011 and stabilized thereafter, both for the Austrian (125 references in total to trilogues) and the Dutch parliament (162 references in total to trilogues).

Figure 1. References by MPs to trilogues, Austria. Source: https://www.parlament.gv.at/SUCH/index.shtml?advanced=true&simple=false&mode=pdadvanced.

Figure 2. References by MPs to trilogues, the Netherlands. Source: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/uitgebreidzoeken/parlementair.

The peak in references in the Austrian parliament can be explained by the over 100 written questions – with identical phrasing for all questions – during the period the Austrian government was at the helm of the Council by one MP from the SPÖ on the status of negotiations in trilogues on a range of legislative files. One caveat is in order here: because the committee meetings in the Austrian parliament are available – which is exceptional for mandating systems – but only in summary form (Parlaments korrespondenz) and not ad verbatim like in the Netherlands, this could have influenced the results. However, Austrian respondents indicated in interviews that in the committee meetings of the Nationalrat and the Bundesrat, trilogues were not discussed in depth. In contrast, Dutch respondents could come up with several examples in which trilogues were referred to by different MPs in committee meetings throughout the entire time period studied. This can account for the higher number of committee meetings in the case of the Netherlands in which a reference was made to trilogues (86 committee meetings) when compared to the Austrian parliament (3 committee meetings). Moreover, even the references to trilogues in a comparable sub-arena of both parliaments are higher in the case of the Netherlands compared to Austrian debates, i.e., there are 5 plenary debates in Austria vs. 17 plenary debates in the Netherlands with a reference to trilogues. A similarity between the two cases is that the Lower Houses of both Austria and the Netherlands are more active than the Upper Houses in these respective member states. Both the Austrian Bundesrat (7 references to trilogues of the 125 references to trilogues in total) as well as the Dutch Eerste Kamer (5 references to trilogues of the 162 references to trilogues in total) primarily raised concerns on the lack of transparency of the trilogues, but did not go into detail with regard to what was discussed substantively in specific trilogues.

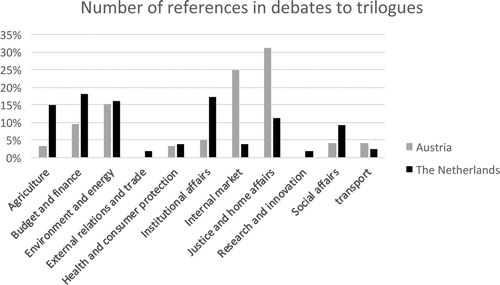

One of the respondents stated that MPs ask more questions to the government, especially when the particular issue is considered a national priority (I17). There is only limited supporting evidence for this claim in the parliamentary documents with references to trilogues in the Dutch and Austrian parliaments. When we look at the references across policy fields, we see a rather diffuse picture with some remarkable peaks in references to certain policy fields and trilogues (see ). One such peak for the Netherlands can be seen in the references to fisheries policy (24 references, as part of the broader agricultural category) and policies related with budget and finance (29 references) and the environment and energy (26 references) (see ). The high score for institutional affairs can be explained by attention paid in 2018 in the Dutch Tweede Kamer to a report by a national rapporteur on increasing the transparency of trilogues. These peaks are less present for the Austrian parliament, especially for the agricultural policy field. This is probably not related with a disinterest in agricultural affairs by Austrian MPs, but more with the fact that there are a relatively high number of trilogues in the sub-field of fisheries compared to other agricultural sub-fields and the lack of interest of the Austrian parliament in fisheries policy. One of the peaks in references to trilogues in the Austrian policy which is remarkable is the attention to justice and home affairs (39 references), especially related with migration and data protection.

Figure 3. References by MPs to trilogues, by policy domain here. Source: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/uitgebreidzoeken/parlementair https://www.parlament.gv.at/SUCH/index.shtml?advanced=true&simple=false&mode=pdadvanced.

The second research question we explore is on how NPs try to shed light on what goes on in trilogues and whether we can discern certain patterns. A key insight we obtained from our interviews is that all NPs make use of the network set up as a response to the institutionalization of the ‘Lisbon tools’ in order to shed light on what happens in trilogue negotiations. This network consists mainly of EU liaison officers and is apparently not only used for coordinating yellow cards between NPs as part of the EWS in the agenda-setting phase (Neuhold & Högenauer, Citation2016). As one liaison officer puts it: ‘you have to knit a network like a sweater, you have to work on that every day. A successful network is that network that is only a ‘phone-call away when you need it’ (I9). NPs do not have structural access to the four-column documents, which provides an insight in the (evolving) positions of each EU institution involved in the trilogue negotiations. However, the German Bundesrat has privileged access to this information because its members need to be represented in Council Working groups when Laender competences are affected by the proposed EU legislation. The Bundesrat also has extensive information rights vis-à-vis the German federal government. This information is often shared in the network of liaison officers.

Other ways to obtain information about trilogues is through activating other nodes in the network, such as asking the national permanent representation of the respective member state of the MP, to get access to the Council delegate portal with limité documents of the Council working groups, or informally obtain information via legal translators present at the trilogues or via Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) (I2; I14; I15; I17). This information is subsequently shared with the European Affairs Committee of the NP (I2). However, EU advisors of NPs point out that information that is leaked and not obtained via the official channels is not very useful because the source cannot be disclosed to MPs and, hence, MPs are reluctant to resort to such information (I14; I15). Interviewees stress that it is much easier to have access to information on trilogue negotiations if the EP rapporteur is from the same member state as the liaison officer (I1;I2;I3;I4;I5;I6;I7). EU liaison officers again play a vital role because also have a network of contacts within the other EU institutions. Also here, it is often persons within EU institutions with the same nationality as the liaison officer who are seen as the most useful sources of information. Moreover, staff of NPs focusing on EU affairs often worked in Brussels previously and have a network of contacts in Brussels, both within the EU institutions as well as with the rotating presidency of the Council and with CSOs (I14;I17).

The interviews also shed light on the second part of our second research question, i.e., with regard to the patterns between NPs on how they shed light on what goes on in trilogues. We found that parliaments with a mandating system such as Latvia or Lithuania – that build inter alia on the Danish mandating system of scrutiny – focus their scrutiny efforts on the position of their government in Council negotiations. One of our interviewees stated:

We engage through the Council. The EP is a different beast. They work in a different way and our NP does not follow up much what happens in the EP or in trilogues. When there are negotiations in the Council, the minister needs to ask for an update of the NP. This results in a national position. (I2)

In general, our interviewees reported on a lack of parliamentary attention for trilogue negotiations by NPs with a mandating system. The main reason provided by respondents for this is the strong focus in mandating systems on Council decision making and controlling the activities of the national government in this institution instead of on the opaque meetings between the EP, Council and Commission representatives.

Another pattern with regard to how NPs follow what goes on in trilogues is that parliaments without a mandating system, have the tendency to take the information provided by the government on the trilogue negotiations less for granted. However, all NPs are to a considerable extent drawing upon information provided by the national government on trilogues. As one of our interviewees states:

Before each Council meeting there is a meeting of our EAC. After the meeting of the Council, the minister needs to report back to the EAC about what the results are of the negotiations and why the result is what it is. (I6)

However, there is some anecdotal evidence indicating that MPs in NPs without a mandating system try to obtain information not ‘filtered’ by their national government. For example, in the Dutch parliament national rapporteurs are appointed for specific highly salient EU dossiers prioritized by sectoral parliamentary committees. The MPs with such a rapporteur role have then the task to closely monitor developments in the EU legislative process, attempting to shed light on what happens in trilogue negotiations and travel to European capitals and Brussels to communicate the Dutch parliamentary position on the specific EU dossier.

In a similar vein, the Italian Senate organizes hearings with the EP rapporteur and/or shadow rapporteurs present in trilogues. These hearings take place via video conferencing or through visits to Brussels of Italian senators. Other parliaments also try to signal to these actors what their position is on EU dossiers in negotiation at the EU level. The Romanian parliament sends all its opinions on specific legislative dossiers to the respective EP rapporteurs and also actively put forward their position to their own permanent representation. In Portugal, Portuguese MEPs can be invited to parliament (I3;I4;I9). In exceptional circumstances, this ‘signalling’ can be rather effective, as shown by the Dutch rapporteur system and the UK parliament in the case of the Port’s Services Directive. The Dutch rapporteur system can only be effective in communicating positions on EU policy dossiers when the whole House is behind the position of the MP rapporteur and a united front can be presented against (elements) of an EU legislative proposal (I15). Similarly, in the UK House of Commons there was a united front against the proposal by the European Commission on Port’s Services and how it was subsequently dealt with by the Council and the EP (I1).

This anecdotal evidence on non-mandating parliaments relying less on unfiltered information by their governments does not mean that mandating parliaments do not attempt to collect unfiltered information. The fact that respondents from mandating parliament did not come up with examples on how they collect unfiltered information can also mean that efforts take place behind closed doors in committee meetings in which the negotiation mandate is formulated.

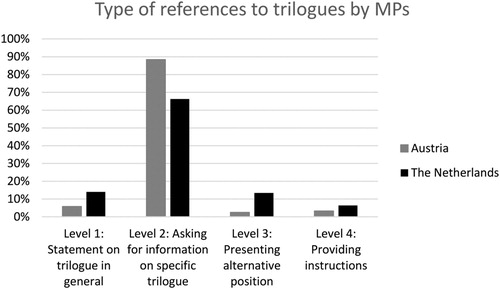

The third research question we aim to answer is why NPs pay attention to trilogues, and why they do pay attention in a certain way? The results of the comparative case study between Austria and The Netherlands show that MPs monitor what goes on in trilogues in order to have sufficient information to be able to hold their government to account for policy decisions. The data included in seems to hint at that Dutch MPs hold the government slightly more to account for decisions made in trilogues than Austrian MPs. The four levels included here are part of a scrutiny ladder, where with every step higher on the ladder the possibility for the government to not respond to parliament is reduced (Smeets & De Ruiter, Citation2019). Dutch MPs try more often (21 references, 13 per cent of total references) than Austrian MPs (3 references, 2.5 per cent of total references) to ask for a reaction of the government to an alternative position to the government position in trilogues. Moreover, Dutch MPs (10 references, 6 per cent of total references) also try more often than Austrian MPs (4 references, 3 per cent of total references) to get a resolution accepted during plenary debates to bind the government to a certain policy position in trilogue negotiations. Most of the resolutions and written questions were tabled by MPs, both in the Dutch and Austrian parliament, when their own country was in the rotating presidency of the Council. MPs seem to know when the policy effect of a resolution or a written question is likely to be greatest; the government of the country holding the rotating presidency of the Council is as the sole representative of the Council always present in trilogue meetings because negotiates on behalf of the Council. Although the president of the Council cannot diverge from the Council mandate, MPs do try to raise attention for their position with some more force when their national government is negotiating in trilogues as Council president.

Figure 4. Type of references to trilogues. Source: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/uitgebreidzoeken/parlementair https://www.parlament.gv.at/SUCH/index.shtml?advanced=true&simple=false&mode=pdadvanced.

It seems that some MPs are interested in monitoring decision-making in trilogues and act upon information on these decision-making processes when their goal is to affect policy. In other words, MPs seem to be policy-seeking actors (Strøm, Citation1990) who aim to steer the negotiation position of the government during trilogue meetings in the direction of their own convictions. A mixed picture arises in the collected data for vote-seeking motivations to engage with trilogues. First, the policy dossiers on which trilogues are held are rather specialized and technical, leaving little room for MPs using these dossiers to gain votes in upcoming elections. Second, another indicator for a vote-seeking strategy could be the difference between government and opposition parties in how they refer to trilogue negotiations. However, there are no discernable differences in attention for trilogues between government and opposition parties in the Netherlands. Both like to be up to speed with regard to the main developments in trilogues on policy fields with many trilogues at the EU level. A caveat is in order here. One needs to take into account that the same Austrian MP from an opposition party asked the exact same informative question for many different policy fields. Without these 100 references to trilogues, the remaining references are equally distributed over opposition and government parties in Austria. In the Netherlands different MPs – both from opposition parties and government parties – asked for information on negotiations in trilogues on a range of policy fields.

Third, the attention by MPs for trilogues manifests itself mainly in parliamentary committees or through written questions, two arenas which are less visible for the electorate at large. Eurosceptic parties are rarely present in committee meetings, and do not submit written questions and, hence, do not ask for information on what is discussed in trilogues in order to signal to the electorate – as part of a vote-seeking strategy – that they are critical on what is decided at the EU level (I17).

Discussion

The analysis of the practical engagement of NPs in trilogues, provide several building blocks for explaining patterns with regard to how NPs shed light on what goes on in trilogues. The findings show that NPs operate in a formal and informal institutional context, both at the EU level and at the national level. These institutional arrangements are used by MPs to lower transaction costs of collecting information on trilogue negotiations in order to be able to hold the government to account and steer the negotiation position of the government in the direction of their own policy positions.

With regard the institutionalist elements of our interpretation of the findings, we found that MPs make use of the informal network set up as a result of the Lisbon tools in order to lower the transaction costs of collecting information on what decisions were taken during trilogues (De Ruiter, Citation2013). MPs that have an interest in the specific issue at stake (Jensen & Sindbjerg Martinsen, Citation2015) resort to the respective network of liaison officers in Brussels (Neuhold & Högenauer, Citation2016) that they have developed for another purpose, to shed light on the ‘black box’ of trilogues (Brandsma, Citation2019; Greenwood & Roederer-Rynning, Citation2019, p. 321). Clearly, NPs put the ‘non-standard’ role of ‘networkers’ to use, beyond the agenda-setting phase to monitor certain decisions in trilogue negotiations by linking up with other parliaments, but also with other EU institutions, in particular, the Council and the EP. We expect this engagement not to be uniform across the board, i.e., not to prevail across all policy issues, as parliaments have limited resources to control their government but to be directed towards specific issues where the respective MPs have an interest at stake (Jensen & Sindbjerg Martinsen, Citation2015).

A second set of insights that can explain patterns with regard to how NPs shed light on what goes on in trilogues, is related to the formal institutional differences between NPs of EU member states in dealing with EU affairs. The difference between mandating and non-mandating parliaments seems to have an impact on the way NPs engage with trilogues. In the case of a mandating system in NPs, it is likely that MPs will focus their attention at the domestic level and use their resources for issuing or updating the negotiating mandate of the national government. An NP without such a mandating system will also try to influence or monitor the negotiations in trilogues, given that they do not have the obligation to issue a negotiation mandate to the national government and can use their organizational capacity to monitor trilogues. We found that these parliaments resort more to informal channels to obtain information on decisions made in trilogues than the mandating parliaments. To put it in a nutshell, NPs with a mandating system concentrate on controlling ‘their’ minister in the Council. MPs in a mandating system often have more opportunities (often behind closed doors) in committee meetings to influence the negotiation position of their government before negotiations take place at the EU level than non-mandating NPs. Hence, parliaments without a mandating system are more likely to develop informal mechanisms to monitor or even influence decision-making in trilogues, given that they do not receive as much information on trilogue negotiations as mandating parliaments.

Our institutionalist interpretation of the empirical material also has a ‘rational choice’ component, which answers the question of why NPs pay attention to trilogues. We found that MPs monitor what goes on in trilogues in order to obtain sufficient information to be able to hold their government to account for policy decisions. The information collection costs are low, as MPs resort to the network of EU liaison officers. In doing so, MPs do not have the intention to gain votes or build a reputation to be considered for office, but see the main benefit of monitoring trilogue negotiations to influence policy. In other words, MPs are policy-seeking actors who aim to steer the negotiation position of the government during trilogue meetings in the direction of their own policy positions and wait for an opportunity when this strategy has the highest chance of success.

Conclusion

We have tried to shed light on the degree to which national legislatures engage with trilogues to monitor negotiations and as such trying to hold the national government to account for its decisions. We come to a somewhat mixed response when it comes to the phenomenon of de-parliamentarization (Karlsson & Persson, Citation2018; Lindseth, Citation2010, p. 10; Maurer & Wessels, Citation2001), with the ‘glass’ being half empty, rather than ‘half full’. This brings us to some starting points for future research. First, we find in all NPs we researched that through the institutionalization of the Lisbon tools, both mandating as well as non-mandating NPs have increasingly become networkers, forging more closer links with other NPs through the EU liaison network (Neuhold & Högenauer, Citation2016). All NPs we examined in this study use the network to obtain information on the progress of the EU legislative process. Some NPs use the network specifically to obtain information on what was discussed in trilogues for highly salient dossiers, which were prioritized by parliamentary committees at the domestic level (Jensen & Sindbjerg Martinsen, Citation2015). Hence, the network helps to obtain information on trilogue negotiations, making it slightly less of a black box for NPs, and enabling NPs to exert policy influence or hold the government to account for decisions in trilogue negotiations.

A second point which warrants further exploration is the transformed role of legislatures after the Lisbon Treaty at the EU level. This transformation is possibly impacting the behaviour of both NPs and the EP in trilogues. On the one hand, the possibility to come to an agreement in first reading through trilogues between the EP, Council and Commission and the extension of the co-decision procedure to more policy fields, led the EP to actively push for trilogues and, hence, asserts itself as a ‘normal’ parliament. The rise in the number of trilogues in the last decade, and according to some, the successful attempt to keep these meetings secluded, was instrumental here (Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, Citation2017, p. 744). This led to a situation in which the EP could insulate itself from actors at other government levels, is holding on to its central role in those trilogues, which reinforces de-parliamentarization at the domestic level.

On the other hand, because NPs have since Lisbon more tools to monitor and potentially influence the agenda-setting phase of the EU legislative process, and learned over the last decade how ineffective these tools can be, the NPs we researched increasingly focus on other phases in the decision-making process than the agenda-setting phase. The findings we present in this explorative study indicate that the parliamentary system of scrutiny at the national level shapes the way NPs deal with this new situation (Auel & Neuhold, Citation2017a). NPs with a mandating scrutiny system turned to their core task, i.e., providing the national government with a mandate to negotiate in the Council. They try to hold their respective executive to account for decisions made at the EU level and have some insights into trilogue negotiations. NPs without a mandating system also looked beyond the Lisbon tools and the agenda-setting phase, but focused more directly on monitoring decision making in trilogues. These NPs found creative, but rather ‘soft’ ways outside of their own internal formal rules to monitor the opaque decision making in trilogues. This resulted in more visible attention for trilogues in parliamentary debates in NPs without a mandating system as opposed to NPs with such a system.

Although the latter tentative finding can be interpreted as an indication of ‘re-parliamentarization’ at the domestic level, our general impression from the detailed study of the Dutch and Austrian parliaments is that there are not many (perceived) possibilities to influence trilogues in the practical political process. This is independent from the differences in system of parliamentary scrutiny. In other words, all the NPs in our sample have difficulty to gain access to the ‘kennel of trilogues’. It is already difficult enough for them to obtain information on when these meetings take place and on the substance of these negotiations (Curtin & Leino, Citation2017; De Ruiter, Citation2013; Jensen & Sindbjerg Martinsen, Citation2015). MPs are often just not aware when they should ‘bark’ to their own government.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

References

- Auel, K., & Benz, A. (2005). The politics of adaptation: The Europeanisation of national parliamentary systems. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 11(3), 372–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330500273570

- Auel, K., & Neuhold, C. (2017a). Europeanisation of NPs in European Union Member States: Experiences and best-practices (Report for European Parliament). Greens/EFA Group.

- Auel, K., & Neuhold, C. (2017b). Multi-arena players in the making? Conceptualizing the role of NPs since the Lisbon Treaty. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(10), 1547–1561. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1228694

- Bellamy, R., & Kröger, S. (2014). Domesticating the democratic deficit? The role of NPs and parties in the EU’s system of governance. Parliamentary Affairs, 67(2), 437–457. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gss045

- Brandsma, G. J. (2015). Co-decision after Lisbon: The politics of informal trilogues in European Union lawmaking. European Union Politics, 16(2), 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116515584497

- Brandsma, G. J. (2019). Transparency of EU informal trilogues through public feedback in the European Parliament: Promise unfulfilled. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(10), 1464–1483. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1528295

- Cooper, I. (2006). The watchdogs of subsidiarity: National parliaments and the logic of arguing in the EU. Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(2), 281–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00623.x

- COSAC. (2009). 12th Bi-annual Report. https://cosac.eu/documents/bi-annual-reports-of-cosac

- COSAC. (2013). 19th Bi-annual Report. http://cosac.eu/documents/bi-annual-reports-of-cosac

- Curtin, D., & Leino, P. (2017). In search of transparency for EU law-making: Trilogues on the cusp of dawn. Common Market Law Review, 54(6), 1673–1712.

- De Ruiter, R. (2013). Under the radar? NPs and the ordinary legislative procedure in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(8), 1196–1212. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.760328

- De Ruiter, R., & Neuhold, C. (2012). Why is fast track the way to go? Justifications for early agreement in the co-decision procedure and their effects. European Law Journal, 18(4), 536–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2012.00617.x

- De Wilde, P. (2012). Why the early warning mechanism does not alleviate the democratic deficit. OPAL Online Paper, 6.

- European Ombudsman. (2015). Decision of the European Ombudsman setting out proposals following her strategic inquiry OI/8/2015/JAS concerning the transparency of Trilogues. https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/fr/decision/en/69206

- Greenwood, J., & Roederer-Rynning, C. (2019). In the shadow of public opinion: The European Parliament, civil society organizations, and the politicization of trilogues. Politics and Governance, 7(3), 316–326. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i3.2175

- Hefftler, C., Neuhold, C., Rozenberg, O., & Smith, J. (Eds). (2015). The Palgrave handbook of NPs. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hoerner, J. M. (2017). Real scrutiny or smoke and mirrors: The determinants and role of resolutions of national parliaments in European Union affairs. European Union Politics, 18(2), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116516688803

- Högenauer, A. L., & Neuhold, C. (2015). NPs after Lisbon: Administrations on the rise? West European Politics, 38(2), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.990698

- Jensen, M. D., & Sindbjerg Martinsen, D. (2015). Out of time? – NPs and early decision making in the European Union. Government and Opposition, 50(2), 240–270. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.20

- Karlsson, C., & Persson, T. (2018). The alleged opposition deficit in European Union politics: Myth or reality? Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(4), 888–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12688

- Kreilinger, V. (2013). The new inter-parliamentary conference for economic and financial governance. Notre Europe Policy Paper, 100.

- Lammert, N. (2009, 1 December). Europa der Bürger – Parlamentarische Perspektiven der Union nach dem Lissabon-Vertrag. Speech at the Humboldt University.

- Lindseth, P. (2010). Power and legitimacy: Reconciling Europe and the Nation State. Oxford University Press.

- Maurer, A., & Wessels, W. (2001). National Parliaments after Amsterdam: Losers or latecomers? Nomos.

- Miklin, E. (2015). The Austrian parliament and EU affairs: Gradually living up to its legal potential. In C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg, & J. Smith (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union (pp. 389–406). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Neuhold, C., & Högenauer, A. L. (2016). An information network of officials? Dissecting the role and nature of the network of parliamentary representatives in the European parliament. Journal of Legislative Studies, 22(2), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2016.1163884

- O'Brennan, J., & Raunio, T. (2007). National parliaments within the enlarged European Union from victims of integration to competitive actors? Routledge.

- Rasmussen, A., & Reh, C. (2013). The consequences of concluding codecision early: Trilogues and intra-institutional bargaining success. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(7), 1006–1024. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.795391

- Raunio, T. (2011). The gatekeepers of European integration? The functions of national parliaments in the EU political system. Journal of European Integration, 33(3), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2010.546848

- Raunio, T., & Hix, S. (2000). Backbenchers learn to fight back: European integration and parliamentary government. West European Politics, 23(4), 142–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380008425404

- Ripoll Servent, A. (2018). The European Parliament. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ripoll Servent, A., & Pannning, L. (2019). Preparatory bodies as mediators of political conflict in trilogues: The European parliament’s shadows meetings. Politics and Governance, 7(3), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i3.2197

- Roederer-Rynning, C., & Greenwood, J. (2015). The culture of trilogues. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(8), 1148–1165. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.992934

- Roederer-Rynning, C., & Greenwood, J. (2017). The European parliament as a developing legislature: coming of age in trilogues? Journal of European Public Policy, 24(5), 735–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1184297

- Smeets, S., & De Ruiter, R. (2019). Scrutiny by means of debate. The Dutch parliamentary debate about the Banking Union. Acta Politica, 54(4), 564–583. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0091-3

- Sprungk, C. (2013). A new type of representative democracy? Reconsidering the role of NPs in the European Union. Journal of European Integration, 35(5), 547–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.799944

- Strøm, K. (1990). A behavioral theory of competitive political parties. American Journal of Political Science, 34(2), 565–598. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111461

- Winzen, T. (2012). National parliamentary control of European Union affairs: A cross-national and longitudinal comparison. West European Politics, 35(3), 657–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665745

- Winzen, T., De Ruiter, R., & Rocabert, J. (2018). Is parliamentary attention to the EU strongest when it is needed the most? National parliaments and the selective debate of EU policies. European Union Politics, 19(3), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518763281