ABSTRACT

This article explores the institutionalization of trilogues in the Council. What kind of practices have emerged in the Council to underpin this body’s participation in trilogues, and how do these shape the decision-making culture in the Council? We conceptualize the institutionalization of trilogues in the Council using delegation theory, and particularly through the lens of two ideal-types of delegation focusing on sanctions and selection, respectively. We explore these ideal-types by drawing on extensive elite interviews. Following the distinction between mandating, monitoring, and sanctioning common to delegation relationships, we find the greatest changes in the mandating and monitoring of the Presidency, and few changes in the sanctioning processes. This shows that the sanctions model is on the rise. We find that trilogues have changed the Council as a legislative institution.

Introduction

The institutionalization of trilogues in the Council of the EU remains a blind spot in the literature. Two separate but complementary debates frame our investigation. The first debate is about how trilogues are compatible with the development of genuine democracy at the EU level. The trilogue scholarship has grown a lot in the last two decades; however, it has not provided a simple or consensual answer to this question (Brandsma, Citation2019; Dionigi & Koop, Citation2017; Farrell & Héritier, Citation2004; Héritier & Reh, Citation2012; Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, Citation2015, Citation2017; Shackleton & Raunio, Citation2003). Some regard trilogues as an impediment to democratic decision-making measured against standards of open and public political processes, while others see them as an emerging institution of legislative conflict resolution, not unlike the institutions and practices existing in bicameral political systems at the national level. Regardless of the differences between the two positions, both assume that the Council is a main source of opacity in the EU’s legislative process due to its diplomatic culture of decision-making. Exactly this assumption, however, has been the object of the second debate in a separate strand of the scholarship.

The second debate concerns the culture of decision-making in the Council. An influential body of literature views it as a club-like institution permeated by norms of consensus, mutual responsibility, diplomatic discretion, and diffuse reciprocity (Hayes-Renshaw & Wallace, Citation2006; Lewis, Citation2000, Citation2015). In the last decade, however, new research has challenged the importance of socialization effects in the Council and pointed to growing internal contestation (Hagemann et al., Citation2019; Naurin, Citation2015; Novak, Citation2013).

Though complementary, the two debates have largely developed in isolation from each other. A notable exception is the careful analysis of the effects of codecision in the Council by Häge and Naurin (Citation2013). This work suggests that trilogues cancel out the positive effects of codecision – a greater degree of politicization via ministerial involvement – by contributing to the growing informal character of the EU legislative process (Häge & Naurin, Citation2013). While insightful, this analysis is now dated as it is based on the 2003–2009 period, which is not representative of current trilogue practice (Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, Citation2015, Citation2017). More recently, several authors have argued that trilogues have contributed to making the Council decision-making process less transparent, under the umbrella of the ‘space to think’ and in the name of ‘efficiency’ (Hillebrandt & Novak, Citation2016; Novak & Hillebrandt, Citation2020).

In this article, we contribute to this strand of scholarship by asking what kind of practices have emerged in the Council to underpin its participation in trilogues, and how these practices shape the decision-making culture in the Council. We proceed in four steps. First, we explain how intra-institutional practices may have inter-institutional effects, which in turn spurs intra-institutional change. In doing so, we problematize the widespread assumption of institutional isomorphism according to which trilogues are made in the image of the Council’s culture, which implies that virtually no adaptation to trilogues inside the Council has taken place. Second, taking our cue from the debate on the evolving culture of Council decision-making, we flesh out two ideal-types of institutionalization of trilogues in the Council, emphasizing logics of selection and sanction, respectively. Third, we provide a brief discussion of our analytical approach and methodology. The last part is devoted to the analysis of the institutionalization of trilogues in the Council, from mandating to monitoring the presidency and sanctioning, and identifying the implications thereof. We conclude by summing up our findings and discussing their implications for the relevant scholarships outlined above.

Trilogues in the image of the Council?

A key argument in the literature of EU institutional change is that inter-institutional dynamics have intra-institutional effects and hence spur intra-institutional change (cf. Farrell & Héritier, Citation2004; Héritier & Reh, Citation2012; Naurin & Rasmussen, Citation2011). Despite the great interest paid to trilogues in this literature, most studies have focused on institutional change in the EP and not in the Council (cf. Häge & Naurin, Citation2013 for a notable exception). A possible reason for this lacuna could be that trilogues are widely perceived to reflect the Council’s existing culture (e.g., Huber & Shackleton, Citation2013), which implies that virtually no change inside the Council can be expected. In this section, we present and challenge this thesis of institutional isomorphism, calling for an examination of changes in the institutionalization of trilogues within the Council.

Institutional isomorphism posits that widely different organizations operating in the same environment tend to converge (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). It attributes this to a mix of coercive and normative factors including peer pressure, material dependency, and the emergence of professional norms and ‘rationalized myths’ (Clegg, Citation2010). Depending on the specific pattern of conformity-inducing factors, it may take the form of coercive isomorphism (prevalence of material mechanisms), mimetic isomorphism (prevalence of uncertainty), and normative isomorphism (prevalence of professionalization).

Several claims in the literature provide prima facie evidence of trilogues having been shaped in the image of the Council through normative and coercive isomorphism. At the core of this interpretation is the traditional view of the Council as an organization underpinned by a deeply ingrained set of norms. Although different positions on interaction patterns in the Council have always existed (e.g., Beyers & Dierickx, Citation1998; Warntjen, Citation2010), from a cultural point of view scholars emphasized the pivotal role of a consensual decision-making logic where explicit voting seldom takes place (Hayes-Renshaw & Wallace, Citation2006; Novak, Citation2013). Consensus-seeking behavior is supported by a set of norms which constitute collective expectations for appropriate behavior: trust, mutual responsiveness, diffuse reciprocity, a culture of confidentiality and compromise, and not wanting to be in a minority position (Lewis, Citation2000, Citation2005; Novak, Citation2013). Trust is established by being able to keep one’s promises, deliver, and help others. Mutual responsiveness requires diplomats to explain and justify their positions to make it easier for others to understand and account for them. Diffuse reciprocity involves self-restraining behavior where diplomats do not push their position too hard on one dossier if it will harm their reputation in the long run (Howorth, Citation2011). The culture of compromise concerns the tendency to accommodate divergent interests to reach a compromise, even if it requires spending extra time to get everyone on board.

These norms permeate Council behavior, from the working parties to the ministerial level. At the ministerial level, with a few exceptions (e.g., agriculture), the presidency attempts to get all member states on board rather than push for a vote, which is considered inappropriate (Lewis, Citation2010). The levels below the ministerial Council consist of the working groups and two Committees of Permanent Representatives (Coreper 1 and 2). They represent the backbone of the Council’s organization. Together, working groups and Coreper are at the center of networks ‘with club-like stakeholder dynamics among policy specialists [national officials/diplomats]’ (Lewis, Citation2015, p. 223), who meet in camera over long time-horizons.

Based on this interpretation of the Council as a consensus-based organization, the literature provides several indications that the Council has shaped trilogues by exporting its own method and norms. It played a key role in the ‘invention’ of trilogues as a negotiating device at the turn of the 2000s (Rittberger & Goetz, Citation2018; Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, Citation2015; Shackleton, Citation2000): they emerged in response to the Council’s early experience of codecision as an unwieldy and unpredictable legislative process. From the Council’s perspective, trilogues reduced these uncertainties and reintroduced a degree of control.

One strand of the literature on trilogues goes further by pinpointing how the process of trilogue negotiation itself institutionalizes Council norms through the emergence of the myth of the ‘responsible’ legislator (Ripoll Servent, Citation2015, Citation2018). This myth is epitomized in the so-called ‘realist vision’ of codecision, which ties the organizational-political constraints of implementation (by the member states) to self-restraint (by the members of the EP) in the legislative process (Jacqué, Citation2009). Trilogues institutionalize self-restraint through urging MEPs to moderate their demands and through limiting public scrutiny into the legislative process. In turn, this deprives the EP from one of its strongest sources of legitimacy and therefore political significance (Curtin & Leino, Citation2017), and some research provides evidence that MEPs have indeed moderated their claims (Brandsma & Hoppe, Citation2020; Burns & Carter, Citation2010). The density of Council-EP interaction in and around trilogues has allegedly provided many opportunities for the Council to socialize MEPs into this myth and disseminate professional norms attuned to the Council’s culture (Burns & Carter, Citation2010). Likewise, the very organizational format of trilogues, with its emphasis on seclusion and confidentiality, seems to confirm the thesis of institutional isomorphism. Indeed, these features seem foreign to the parliamentary logic of decision-making that the EP has increasingly identified itself with (Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, Citation2017), with its emphasis on accessible and documented deliberations, institutional oversight, public participation, transparency, and procedural rules (Reh, Citation2014, pp. 825–827). Finally, the fact that the single most significant rebuttal of the trilogue process to date, the CJEU’s De Capitani ruling (General Court of the European Union, Citation2018, Case T540/15), originated within the EP’s own ranks, from a civil servant’s critique of what he saw as a capitulation of the EP leadership to Council norms, seems to be a powerful indication that one logic, that of the Council, prevails in trilogues.

While this would seem to provide prima facie support for the institutional isomorphism thesis, and hence, no reason to investigate changes within the Council as a result of trilogues, a number of developments shed a different light on the Council’s relation to these. For some time now, the literature on the institutionalization of trilogues has evidenced a strengthening of organizational pluralism and diversity. These include the formalization of the method by which the EP team is formed and mandated in trilogues, as well as the emergence and formalization of strong pluralistic EP-centered networks, spawned to monitor the trilogue negotiations and enforce the EP position throughout the trilogue process (Greenwood & Roederer-Rynning, Citation2019; Héritier & Reh, Citation2012; Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, Citation2015, Citation2017). These networks ensure a permanent flow of information between institutional and non-institutional actors, which erodes the confidentiality of the trilogue process: trilogues have become permeable institutions (Greenwood & Roederer-Rynning, Citation2020). This has happened to some extent under the pressure of the EP and organized interests, but it would be mistaken to assume that the EP has spearheaded these changes exclusively. Member states, too, have been agents of change in making trilogues permeable (e.g., Brandsma & Hoppe, Citation2020), paradoxically undermining the norm of confidentiality that is cardinal for the Council working method. Hence, in view of these organizational and normative changes in the Council’s institutional environment we should take seriously the possibility that the Council has adapted its internal workings to these inter-institutional changes (cf. Héritier & Reh, Citation2012; Naurin & Rasmussen, Citation2011).

At the same time, recent Council scholarship calls into question several features of the culture of consensus, which challenges the continuing relevance of the institutional isomorphism thesis and hence increases the likelihood that the Council has in fact changed its internal handling of trilogues in recent years. While more than 90 per cent of Council decisions were adopted without votes against in 2009, this figure had dropped by 20 percentage points down to slightly more than 70 per cent in 2018 (Reh & Wallace, Citationforthcoming). This indicates a rise in contested decision-making. Under-the-radar forms of contestation, such as abstentions and statements, show an even steeper rise (Reh & Wallace, Citationforthcoming). So, while implicit forms of contestation continue to be the preferred recourse of member states, there has been an unmistakable rise in different forms of contestation over the last decade. It seems to vary across issues and member states, but a pattern of growing responsiveness of member states to domestic politics seems to underpin these differences (Hagemann et al., Citation2019; Hobolt & Wratil, Citation2020; Mühlbock & Tosun, Citation2018). These developments point to a weakening of the consensual culture in Council – although some scholars have more fundamentally questioned whether such a culture ever characterized Council decision-making (e.g., Naurin, Citation2015). Thus, we must beware of treating the Council as a static institution regulated by immutable norms of trust, diffuse reciprocity, and consensual decision-making.

In sum, while there is a widespread assumption that trilogues reflect the normative and coercive dominance of the Council in the EU’s legislative process, we claim that this assumption is based on two outdated understandings. First, it neglects the institutionalization of trilogues and their growing permeability to a plurality of actors, and second, it neglects the possibility that the culture within the Council may be subject to change. In line with existing theories of institutional change (cf. Héritier & Reh, Citation2012; Naurin & Rasmussen, Citation2011), we explore to what degree these inter-institutional changes have had repercussions for the Council’s internal handling of trilogues, in the context of an eroding culture of consensus within the Council.

Two ideal-types of Council trilogue institutionalization

We now proceed to our theoretical framework, which seeks to capture the institutionalization of trilogues within the Council. The Council’s rotating Presidency is the key actor in this. In contrast to the European Parliament (EP), which has a negotiation team in trilogues representing all the political groups, the Council relies on the Presidency to represent its 27 member states. The role of the Presidency has been depicted as involving a mixture of norms. It is supposed to be neutral: it represents the institution externally, it administers it internally, and it acts as a mediator between conflicting member state interests and helps to ensure progress. Simultaneously, being in the driver’s seat also creates opportunities to advance the Presidency’s own member state interest (Kaniok, Citation2016; Niemann & Mak, Citation2010; Tallberg, Citation2003). As in other situations where the Presidency represents the member states, trilogues add an extra arena where these two sets of norms may clash. The big difference between trilogues and many other negotiations, however, is that the trilogue negotiations take place in camera and the member states do not have direct access to the negotiations.

Trilogues provide opportunities for hidden action to the Presidency, which for the member states in the Council results in a moral hazard problem. In an earlier study of codecision between 2003 and 2009, Häge and Naurin (Citation2013) conclude that although trilogues impede transparency and accountability of its participants, it does not de facto give the Presidency a more privileged position. But since 2009, several things have changed that may call for a new assessment. The number of early agreements involving trilogues has increased dramatically over the last decade (Brandsma, Citation2015; Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, Citation2015), increasing the sheer number of opportunities for the Presidency to pursue its own interest. The increased contestation inside the Council (cf. above) suggests that member states shy away less and less from explicitly pursuing their own interests, and that the Presidency increasingly accepts not having all member states on board. This combination of developments lowers the bar for opportunistic behavior and spurs a demand for more stringent control over the Presidency.

The representative relationship between the Council and its Presidency in view of trilogues is central to our analysis. In this section, we outline two possible ideal-types of how this representative relationship, including the role of control therein, may be understood. Drawing on the literature on delegation and representation, we flesh out two ideal-typical models of representation in trilogues with varying emphasis on control and trust: the sanctions model and the selection model (cf. Mansbridge, Citation2005, Citation2009, p. 303, Citation2011).

The shared starting point of these two ideal-types is that representation of the Council in trilogues entails delegation to the Presidency. In delegation relationships, there are four main control mechanisms by which principals (i.e., the member states in the Council) try to ensure that their agent (i.e., the Presidency) remains loyal (cf. Blom-Hansen, Citation2005; Delreux & Adriaensen, Citation2017). This entails a careful selection of the agent, contract design, monitoring of the agent’s behavior, and sanctions for drifting away from the original contract. But in the Council, the principals are not completely free to craft any of these four elements completely to their liking. The main caveat is that member states in the Council (unlike MEPs in the EP) have no influence on the choice of their representative in trilogue negotiations. By center-staging the rotating presidency, the member states cannot select which member state represents them in trilogues. Similarly, they cannot dismiss the Presidency as the ‘nuclear option’ among sanctions. This leaves the member states with contract design, monitoring, and ‘softer’ sanctions such as reputational loss (e.g., Huber & Shackleton, Citation2013; Lewis, Citation2015, p. 225; Ripoll Servent, Citation2015) as the main available control instruments. These three elements are, therefore, central to our empirical analysis: (1) the procedures mandating the presidency, (2) the feedback provided by the presidency after trilogue meetings, and (3) the sanctions available to the Council. So, how do these three elements of control over the Presidency relate to the decision-making culture inside the Council?

This is where the two ideal-types part ways. The sanctions model follows standard principal-agent theory: it assumes that representatives often have goals antithetical to those they represent and are likely to act against the latter’s interests. After selecting an agent and formulating a strict mandate, the emphasis of this model is on monitoring and exercising control. To induce responsiveness and prevent shirking, representatives must be kept on a tight leash to avoid deviation from the original contract (Blom-Hansen, Citation2005; Rehfeld, Citation2009, Citation2011). As an ideal type, this model fits a culture of distrust and thin socialization between principals and their agent. Its strong emphasis on control seeks to prevent opportunistic behavior on the side of the agent.

The selection model, by contrast, assumes that representatives are driven by an intrinsic motivation to perform well rather than by extrinsic threats (Mansbridge, Citation2005, Citation2009, p. 393, Citation2011). The agency relationship is based on mutual trust and common goals. Control focuses on reason-giving by the agent, explanations, and justifications for his or her actions rather than on policing and sanctioning deviations from the original contract. This ideal type fits norms of mutual responsiveness, thick socialization and a culture of compromise. It has the best conditions when ‘the principal, even if unhappy with the results, can see that the intrinsic motivation underlying the aligned objectives remains unchanged’ (Mansbridge, Citation2009, p. 384). Any change in approach or policy is more acceptable to the principal if it is based on new facts and circumstances rather than divergent objectives between the principals and the representative. Monitoring focuses on the representative’s rationale, serving to ensure that principals can follow their representatives’ behavior and know their basis of decision-making. The selection model has been used before to analyze the representative relationship between the EP and its trilogue negotiators (see Reh, Citation2014).

In the following, and in line with delegation theory that lies at the heart of the two ideal-types, we focus on (1) the procedures mandating the presidency, (2) the feedback provided by the presidency after trilogue meetings, and (3) the sanctions used to hold the Council presidency to account. We use the two ideal types to interpret our findings and link them to our assessment of the decision-making culture in the Council.

A focused-structured analysis

The Council does not have any written down rules or documents outlining the procedure to be followed regarding how the presidency is mandated to start trilogue negotiations and is required to report back. The Council’s rules of procedure do not mention trilogue meetings. Instead, a number of well-established and known practices exist, which are passed on from one presidency to another through extensive training provided to incoming presidencies by the Council’s secretariat and through close cooperation within trio (incoming, present, and outgoing)-presidencies (Dionigi & Koop, Citation2017). These practices are suited to the existing hierarchic levels within the Council, including over 150 specialized working parties who examine files in detail, 10 Council configurations at ministerial level who formally decide and discuss politically sensitive issues, and Coreper 1 and 2 in between which consists of the member states’ permanent EU representatives. They prepare the ministers’ agenda, and oversee the work of the working parties. The distinction between Coreper 1 and 2 lies in the issues that they deal with: most of the Single Market is in the realm of Coreper 1, leaving foreign affairs, justice, home affairs and economic and financial affairs to Coreper 2.

In what follows, we distinguish between how presidencies are mandated to commence trilogue negotiations, their monitoring during negotiations, and the sanctions available to member states if presidencies diverge from their mandate. gives an overview of the practices governing trilogues in the Council, which we further elaborate below.

Table 1. Council trilogue practices.

Our analysis draws on insights from 39 in-depth interviews with Council representatives, making particular reference to 20 respondents who are cited directly.Footnote1 The interviews took place in Brussels in person between April 2017 and February 2019 and the interviewees were promised anonymity to allow them to speak more freely. Out of the 39 interviews, 28 interviews were conducted in 24 member-state Permanent Representations in Brussels, allowing us to achieve a good coverage of different types of member states. Some countries recently held the Council presidency, which gave valuable insights into differences between presidencies. Besides these 28 interviews with officials from the permanent representations, we interviewed 11 civil servants in the Council’s General Secretariat. As a service at the disposal of the presidency, the secretariat shed light on not only their own role, but also the Council’s internal trilogue procedures and practices, and the differences across presidencies and Council configurations. We wrote up reports so as to extract the most significant points, and convergences, drawing upon 27 codes in total so as to identify classification categories, and from there to produce more detailed interview reports. This enabled us to filter interview material across analytic dimensions, and to reconfigure individual case reconstructions. We have reproduced here quotes under different coding dimensions.

Disrupting the Council’s diplomatic culture?

Mandating the presidency

Mandates have two distinct components. A first, explicit component consists of the Commission’s proposal, which includes all amendments that the Council would like to see adopted. It is this explicit part that feeds into the four-column-document that the EU institutions use to keep track of trilogue negotiations. A second, implicit component concerns the room for maneuver for the presidency, determined by the specific priorities of the presidency, its requests for flexibility, red lines of individual member states and the fallback options (R9, 88, 92, 99).

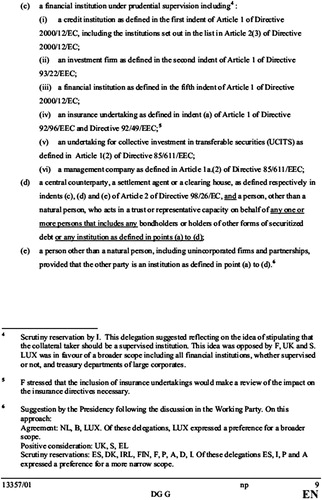

We distinguish from here between processes of preparing and of adopting a mandate for trilogue negotiations. The bulk of the effort of mandate preparation takes place at the working party level. Particularly in technical fields, working parties traditionally kept track of the member states’ positions by inserting footnotes into their working documents. These footnotes recorded instantaneously and sometimes in great detail the position of the national delegations (see ). In other words, they showed the policy space in which the Presidency sought its negotiation mandate, for all member states to see. This ‘footnote system’ was meant for internal use only: to inform national delegations about each other’s positions and facilitate the process of consensus-building in the Council. Besides facilitating vote-counting, the footnote system also reduced the risk of manipulation through control of the information, and made it easy to keep track of the positions of national governments (Ramsay, Citation2019).

Figure 1. An example of the footnote system. Source: Council of the European Union (Citation2001).

There have been claims that the footnote system is falling into disuse and a shift towards bilateral forms of mandating was taking place in the Council (Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, Citation2015, p. 1159), which de facto loosens a constraint on the Presidency when preparing a mandate. Ramsay (Citation2019) has recently evidenced this shift for the period 2007–2015 in the area of single market policy. He traced a change in practices to 2014 when for the first time in this area, the Council entered political trilogue negotiations on the basis of an untraceable mandate. Ramsay (Citation2019, p. 62) attributed this shift to a CJEU ruling and its implications that ‘individual positions of Delegations cannot be subject to exclusion from access to documents. The result is no mentions of footnotes on this proposal’.

In our interviews, Council officials with a long institutional memory confirmed that, at least in the area of single market and better regulation, the working parties do not follow the footnote system anymore. Instead the Presidency, with support from the Council’s secretariat, still sends draft proposals to national delegations, but feedback takes place bilaterally and is not necessarily shared with all delegations. Still, it is at the discretion of the presidency to decide which method is used and whether or not the same method is used consistently in all meetings: one respondent underscored how valuable the footnote system was to his recent presidency (R91), while others added that footnotes were used unevenly across areas (R3, 4).

Reasons given for abandoning the footnote system are twofold: (1) inefficiency as ‘they [the footnotes] delayed negotiations because some delegations fell in love with their footnote, and all will fight for their footnote as they otherwise might have to face their boss’ (R98) and (2) legitimacy issues, since delegations fear being publicly isolated, which is a risk with the footnote system in case the documents get leaked to outsiders (R5; 98; 99) – or disclosed under a less restrictive interpretation of the ‘access to documents’ directives, following the De Capitani ruling. A former head of unit at the Council secretariat put it in similar terms: ‘The footnote model has not been used very much in Council in the last many years. Partly because it has become unmanageable, with footnotes from 25 and later 27/28 delegations; partly because the new communication principle of making virtually all our documents eligible for publications made the delegations uncomfortable about the idea of having their positions officially recorded’ (personal communication, 26 November 2019).

The adoption of a mandate takes place above working party level. The overarching constraint is to find support from at least a qualified majority in Coreper or among ministers, in which case a mandate takes the form of a general approach (R88). In Coreper 1, the understanding is that a qualified majority suffices for the opening of negotiations, while Coreper 2 has more of a consensus tradition (R88, 99). Neither vote (R91). Particularly in Coreper 1, some presidencies are instructed vigorously from their capitals, reducing their flexibility (R94). But ministerial involvement appears quite common: in the 2014–2019 EP term, for 249 files a trilogue procedure has been started (Brandsma & Meijer, Citation2020), and the Council’s document register shows that for 89 of these a general approach was adopted prior to negotiations, which is 36 per cent.

Ultimately, whether or not to go with a general approach is the presidency’s choice (R89, 92, 94, 95). Our interviewees provide different reasons: general approaches are commonly viewed as sending a strong signal to the EP that there is political backing for the mandate at the ministerial level, but they are also useful when there is a substantial minority in the Council, as a way to manage internal dissent (R94, 99). By contrast, a Coreper mandate is perceived to be faster and more flexible than a general approach (R92, 93, 97). Critically, once trilogue negotiations are underway, any revised mandates based on a general approach are adopted by Coreper and not by the ministers (R1, 91, 92). Exceptionally, the shuttle between the ministerial level and Coreper may generate conflicting mandates. One interviewee mentioned a file where Coreper decided not to support the ministers’ general approach – which the EP favored (R98).

The preparation of the Presidency’s mandate, thus, increasingly becomes a bilateral affair between the presidency and the member states. A converging set of evidence highlights the growing informalization of the mandating process in the Council. We find this trend significant, given the advantages of the footnote system in terms of internal and external accountability. Additionally, we find that general approaches are instrumentalized as a way to manage internal dissent, and that for particularly Coreper 1 a qualified majority suffices for opening negotiations. This goes against ingrained consensual norms. Some collective deliberation before authorization of the presidency, thus, is sacrificed to the benefit of decision-making efficiency.

Monitoring the presidency

The presidency decides who represents it during trilogue negotiations. Although the EP insists on high-level representation (R92, 93), negotiations are typically done by an ambassador or the chair of a working group, depending on whether the trilogues are of a more technical or political nature. Only rarely do ministers negotiate themselves (R92, 94, 95); usually this happens when an inter-institutional compromise is looming.

Information on negotiation proceedings is shared with the member states in the Council in two ways. Firstly, the presidency reports back formally on the progress made in trilogues to the rest of the Council through distribution of the updated four-column document, and orally at the following working group and Coreper meeting. Second, if national delegations want an account of the progress made in trilogue meetings before the official reporting back, they seek live updates through informal contact with the presidency and the Council secretariat, and other trilogue negotiators, such as MEPs.

However, the degree to which presidencies report back to the Council depends on the nature and type of inter-institutional trilogue fora. Negotiations do not only take place in trilogues (i.e., at the political level), but also at technical level including members of the EP secretariat and/or assistants of rapporteurs and shadows, or in more informal meetings with a few key figures only. From the presidency’s perspective, there is evidence of managing the confines of a mandate. When referring to their own experiences in the presidency, one member state reported how ‘we didn’t always declare that we had a meeting with a rapporteur’ (R93). Incoming presidencies are trained to reach out to key figures in the EP at a very early stage, which has significant benefits for the negotiation process. In the words of one respondent, ‘the more you can pre-cook with the rapporteur, the easier it is to get an outcome and a smoother deal’ (R93). It is partly because of the secluded nature of such meetings that the behavior of the presidency is regarded with suspicion by minorities in the Council (R12).

In the policy areas overseen by Coreper 2, feedback on trilogues only takes place at working party level (R92, 97, 98). This is the same for Coreper 1 (R88, 98), which however additionally has 5-minute debriefings on every single trilogue in Coreper 1. After preparation by the Mertens-attaché, the deputy permanent representative from the country holding the presidency reads out a report on the meeting and gives a general impression of the trilogue and whether there were any surprises. It is rare that other member states take the floor to ask any questions (R88, 91, 95, 98). The practice is seen as very uneventful and time consuming, as multiple trilogues are discussed during the same Coreper meeting in 5 min each. Although some member states have tried to abolish the practice – preferring to deal with it at the level of Mertens or Antici councilors (R88) – it is now seen as a standard operating procedure since the Finnish presidency introduced it in 2006 (R98).

The short feedback given by the presidency to the Council’s working groups and Coreper after each trilogue meeting and the lack of subsequent questions and discussion is mostly perfunctory. It does not constitute a communicative relationship where the presidency thoroughly explains, justifies, and gives reasons for its actions. However, the formal feedback channel is far from the only or most important way of monitoring the presidency. One respondent admitted that ‘you can use the debriefing a bit for policy-making to move the member states into a certain direction. But as a presidency you are not the only source of information for the member states’ (R93).

This brings us to the informal information channel for monitoring the presidency. Member states found that it is hard for the presidency to diverge significantly from the mandate in practice because other delegations would quickly find out through informal contacts with other people present in the room. Presidencies are also acutely aware of not overstepping their mandate as they have a strong interest to be seen as a trustworthy and successful presidency. At the same time, some member states did not completely trust the presidency to give them the full picture, as the presidency is also motivated by closing a deal (R90). The interviews evidenced a cleavage between large and small member states. In the words of a representative from a medium-sized member state, ‘larger member states have broader access to information, so they can get the presidency coming to them more than smaller member states’ (R5). Another representative noted that ‘the presidency can play with the votes – if you get the support of the big member states you don’t need the small ones’ (R9).

The agency dilemma of hidden information and action is, however, not as severe as anticipated by the sanctioning model. Information on trilogue proceedings is scattered over a wide range of actors and is easily shared. Respondents mentioned rapporteurs, shadow rapporteurs, and their staff as useful sources (R7), as well as Politico and social media (R87, 91, 95). Particularly for larger member states it is relatively easy to obtain information from the EP (R4, 5). Germany was also mentioned as a source, due to their obligation to exchange debriefs to the Bundestag, from which ‘it goes everywhere’ (R95). This wide availability of information restricts the presidencies’ ability to control information flows and use this as a tactic (R93).

Many respondents agreed that member states, when in a minority in the Council, would lobby the EP directly. This in turn incentivizes the Council presidency to talk both to member states and to the EP negotiators outside formal meetings, making trilogues and Coreper something of a rehearsed play (R93, 94, 99). Non-disclosure of such pre-discussions are a matter of trust (R93).

Sanctioning the presidency

If presidencies overstep their mandate, sanctioning takes subtle forms. It is not possible to remove presidencies from office, but the inability to close a deal causes reputational damage, and is the most obvious type of sanction that can apply to presidencies. All compromises agreed in trilogues need to be adopted by Coreper and the Ministers, so the ultimate sanction for a presidency is lack of Council support for an inter-institutional compromise.

That said, it is remarkably difficult to find cases of the above. When red lines need to be crossed for finding political agreement, the default options are either to ‘put things in the fridge’ (R98), or to simply accept the outcome for the sake of having an agreement (R94). Yet, our respondents do remember a few examples of sanctions issued on the presidency.

One respondent recalls finding ‘guidance for discussion’ on a Coreper agenda, accompanied by legislative texts in the attachment. During the meeting the presidency admitted it actually sought a change of mandate, which was not accepted by the member states (R89). Another respondent recounted a situation where (s)he ‘had an obsolete mandate of 2 years ago, and decided to propose something to the EP which was completely out of my mandate, as I was under the impression that it would be acceptable to the Council: [2 member states] would say no but I thought that it would work, and the Commission as well. But then the Green MEP started tweeting and an uproar started on social media, and the rapporteur decided to stop the trilogue’ (R91). But in most cases where respondents recall a presidency going beyond its mandate, the deal still passed, which indicates that a qualified majority still supported the presidency’s negotiated compromise.

Mandates consist of a strong implicit component, including the red lines of the member states (R99). Therefore, whether or not a presidency oversteps its mandate is a matter of perception (R89), and it is up to the presidency to judge whether it can push the boundaries (R99). Still, even when boundaries are pushed, ‘the outcome is not really surprising’ (R94). Some respondents refer in the same wording to ‘risk-taking’ (R92, 93): ‘if something unexpected is put on the table by the EP or the Commission, the presidency needs to decide whether to accept it without consulting the member states first, but that entails risking it to be rejected’ (R92); and ‘you can have creative solutions in the final trilogue for the sake of an agreement – it might be something that was not on the table nor part of the mandate, but you take a risk that it will go through’ (R93).

With the trust of the other member states at stake, presidencies do not want trouble and it is in their interest to consult member states before closing off a deal (R89, 92). The presidency at times calls specific member states even during a trilogue (R92). Still, it needs discretion to reach agreement with the EP (R88, 94). This mechanism works somewhat differently when a minister negotiates on behalf of the presidency. This ‘signals political importance’, and ‘it helps to have someone sitting there who can call other ministers if needed’ (R92). Yet, another respondent observed that ministers are more ‘keen to announce a result’ (R94), which makes them more willing to move back on their own red lines, although the outcome still is not surprising.

Conclusion

In this article, we asked how potentially problematic features of trilogues for the Council affect the underpinning of the Presidency’s participation in trilogues, i.e., the representative relationship between the Presidency and the other member states. Growing tensions associated with the asymmetric role of the presidency, rising societal demands for trilogue transparency, and developing contestation in the Council – to name but a few potential causes – have created an environment in which member states increasingly depart from traditional Council norms of trust, mutual responsiveness, diffuse reciprocity, and a culture of compromise, and focus on stricter monitoring of the Presidency. At the same time, in response to transparency pressures partly over trilogues, practices within the Council have become less transparent. We have argued that the increased public questioning of trilogues has led to some degree of informalization of them, most notably through the disappearance of the footnote system and the resurgent bilateralism. We have fleshed out various expectations using the principal-agent model of sanctioning that emphasizes strict control, and Mansbridge’s alternative selection model where the representative relationship is based on mutual trust and common goals, and the desire by the Presidency to perform well. We found that the two models help us identify how the Council’s working methods regarding trilogues are changing.

We found evidence of a mixed pattern of control and trust that does not neatly correspond to either of our ideal types. We find the greatest changes in the mandating and monitoring processes underpinning Council participation in trilogues, and very few changes in the sanctioning processes. Although overall the selection model captures the Council’s workings best in the realm of sanctioning, we also find that the monitoring of the presidency relates more strongly to the sanctions model, and increasingly so. Most notably, this is through regular reporting requirements and through alternative information channels to keep tabs on the Presidency.

The irony is that this trend weakens the presidency’s role as a relais actor. This is directly associated with the trilogues and is fueled by all Council members. The member states make extensive use of their own information channels to monitor the behavior of the presidency in trilogues, and do thus not exclusively rely on the presidency’s self-reports. This practice corresponds to the sanctions model, and is at odds with the high trust levels that characterize the selection model. In sum, the working methods of the Council have come under pressure as a result of trilogues. The mandating and particularly the monitoring of the Presidency during the negotiations with the EP show evidence of it increasingly being seen as a potentially deviating player in its own right rather than as a first amongst equals.

Rather than adding one extra player to the Council’s game, trilogues thus make the member states interact with a much larger set of actors than only their fellows in the Council, and also with different purposes. Whilst the traditional image of Council negotiations is bargaining, deliberation, or some mixture thereof between working party attachés or the ambassadors in Coreper (Kaniok, Citation2016; Warntjen, Citation2010), we now also see strong evidence of lobbying members of the EP after a loss in the Council (e.g., Brandsma & Hoppe, Citation2020), as well as using the same contacts to monitor the Presidency and contain any agency losses.

Our findings have significant repercussions for views on democracy in European Union politics. Although the debate on the democratic quality of trilogues centers on the secluded nature of trilogue meetings and issues of transparency, trilogues are in fact much more permeable than their image suggests – at least insofar as EU institutional players are concerned. For the member states in the Council, this is both an asset as well as a challenge to existing Council norms. The picture of trilogues as being shaped in the image of the Council is outdated, and neglects the reverse process, namely that inter-institutional practices have had an effect on the Council’s internal workings. As trilogues have become an institutionalized practice in their own right, they are bringing their own challenges to both the Presidency and the member states, and weaken the role of the Presidency as a relais actor for the Council.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Gijs Jan Brandsma is Associate Professor in Public Administration at Radboud University Nijmegen, as well as Visiting Professor in EU Governance at the University of Konstanz.

Maja K. Dionigi is Senior Researcher at Think Tank Europa.

Justin Greenwood is Emeritus Professor of European Public Policy at the Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, UK, and a Visiting Professor at the College of Europe.

Christilla Roederer-Rynning is a Professor with special responsibilities in Comparative European Politics at the Department of Political Science and Public Management, University of Southern Denmark.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The interviews were part of a larger set for which reason the numbering of the interviews does not run neatly from 1 through 39.

References

- Beyers, J., & Dierickx, G. (1998). The working groups of the Council of the European Union: Supranational or intergovernmental negotiations? Journal of Common Market Studies, 36(3), 289–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00112

- Blom-Hansen, J. (2005). Principals, agents and the implementation of EU cohesion policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(4), 624–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500160136

- Brandsma, G. J. (2015). Co-decision after Lisbon: The politics of informal trilogues in European Union lawmaking. European Union Politics, 16(2), 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116515584497

- Brandsma, G. J. (2019). Transparency of EU informal trilogues through public feedback in the European Parliament: Promise unfulfilled. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(10), 1464–1483. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1528295

- Brandsma, G. J., & Hoppe, A. (2020). He who controls the process controls the outcome? A reappraisal of the relais actor thesis. Journal of European Integration, forthcoming.

- Brandsma, G. J., & Meijer, A. (2020). Transparency and the efficiency of multi-actor decision-making processes: An empirical analysis of 244 decisions in the European Union. International Review of the Administrative Sciences, forthcoming.

- Burns, C., & Carter, N. (2010). Is co-decision good for the environment? An analysis of the European Parliament’s Green credentials. Political Studies, 58(1), 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00782.x

- Clegg, S. (2010). The state, power and agency: Missing in action in institutional theory? Journal of Management Inquiry, 19(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492609347562

- Council of the European Union. (2001). Text of the Presidency to the Working Party on Financial Services (collateral) on ‘Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on financial collateral arrangements’. 6 November 2001. Interinstitutional file 2001/0086.

- Curtin, D. M., & Leino, P. (2017). In search of transparency for EU law-making: Trilogues on the cusp of dawn. Common Market Law Review, 54(6), 1673–1712.

- Delreux, T., & Adriaensen, J. (2017). The Principal-Agent Model and the European Union. Palgrave MacMillan.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. (1983). The Iron Cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Dionigi, M. K., & Koop, C. (2017). ‘Investigation of informal trilogue negotiations since the Lisbon Treaty: Added value, lack of transparency, and possible democratic deficit’. Report for the European Economic and Social Committee. CES/CSS/13/2016 23284.

- Farrell, H., & Héritier, A. (2004). Interorganizational negotiation and intraorganizational power in shared decision making: Early agreements under codecision and their impact on the European Parliament and Council. Comparative Political Studies, 37(10), 1184–1212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414004269833

- General Court of the European Union. (2018). Ruling of 22 March (Seventh Chamber). Emiliano De Capitani v European Parliament. Case T540/15, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A62015TJ0540 accessed on 22 August 2019.

- Greenwood, J., & Roederer-Rynning, C. (2019). In the shadow of public opinion: The European Parliament, Civil Society Organisations and the politicisation of trilogues. Politics and Governance, 7(3), 316–326. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i3.2175

- Greenwood, J., & Roederer-Rynning, C. (2020). Power at the expense of diffuse interests? The European Parliament as a legitimacy-seeking institution. European Politics and Society, 21(1), 118–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2019.1613879

- Hagemann, S., Bailer, S., & Herzog, A. (2019). Signals to their parliaments? Governments’ use of votes and policy statements in the EU Council. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(3), 634–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12844

- Hayes-Renshaw, F., & Wallace, H. (2006). The Council of Ministers (2nd ed.). Palgrave.

- Häge, F., & Naurin, D. (2013). The effect of codecision on Council decision-making: Informalization, politicization and power. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(7), 953–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.795372

- Héritier, A., & Reh, C. (2012). Codecision and its discontents: Intra-organisational politics and institutional reform in the European Parliament. West European Politics, 35(5), 1134–1157. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.706414

- Hillebrandt, M. Z., & Novak, S. (2016). ‘Integration without transparency’? Reliance on the space to think in the European Council and Council. Journal of European Integration, 38(5), 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1178249

- Hobolt, S., & Wratil, C. (2020). Contestation and responsiveness in EU Council deliberations. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 362–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1712454

- Howorth, J. (2011). The Political and Security Committee: A case study in ‘ Supranational Intergovernmentalism. In R. Dehousse (Ed.), The ‘community method’: Obstinate or obsolete? (pp. 91–117). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huber, K., & Shackleton, M. (2013). Codecision: A practitioner's view from inside the Parliament. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(7), 1040–1055. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.795396

- Jacqué, J. P. (2009). Une vision réaliste de la procedure de codécision [A realistic viewpoint of the co-decision procedure]. In A. De Walsche & L. Levi (Eds.), Mélanges en hommage à Georges Vandersanden [Essays in honour of Georges Vandersanden] (pp. 183–202). Bruylant.

- Kaniok, P. (2016). In the shadow of consensus: Communication within Council working groups. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 12(4), 881–897.

- Lewis, J. (2000). The methods of Community in EU decision-making and administrative rivalry in the Council’s infrastructure. Journal of European Public Policy, 7(2), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/135017600343197

- Lewis, J. (2005). The Janus face of Brussels: Socialization and everyday decision making in the European Union. International Organization, 59(4), 937–971. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818305050320

- Lewis, J. (2010). How institutional environments facilitate co-operative negotiation styles in EU decision-making. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(5), 648–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501761003748591

- Lewis, J. (2015). The Council of the European Union and the European Council. In J. M. Magone (Ed.), Routledge Handbook of European of European Politics (pp. 219–234). Routledge.

- Mansbridge, J. (2005). The fallacy of tightening the reins. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 34(3), 233–248.

- Mansbridge, J. (2009). A “selection model” of political representation. Journal of Political Philosophy, 17(4), 369–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00337.x

- Mansbridge, J. (2011). Clarifying the concept of representation. American Political Science Review, 105(3), 621–630. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055411000189

- Mühlbock, M., & Tosun, J. (2018). Responsiveness to different national interests: Voting behaviour on genetically modified organisms in the Council of the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(2), 385–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12609

- Naurin, D. (2015). Generosity in intergovernmental negotiations: The impact of state power, pooling and socialisation in the Council of the European Union. European Journal of Political Research, 54(4), 726–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12104

- Naurin, D., & Rasmussen, A. (2011). New external rules, new internal games: How the EU institutions respond when inter-institutional rules change. West European Politics, 34(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.523540

- Niemann, A., & Mak, J. (2010). (How) Do norms guide presidency behaviour in EU negotiations? Journal of European Public Policy, 17(5), 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501761003748732

- Novak, S. (2013). The silence of ministers: Consensus and blame avoidance in the Council of the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 51(6), 1091–1107. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12063

- Novak, S., & Hillebrandt, M. Z. (2020). Analysing the trade-off between transparency and efficiency in the Council of the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(1), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1578814

- Ramsay, R. (2019). Red lines and red tapes: Chains of delegation in inter-institutional and intra-Council negotiations under the ordinary legislative procedure of the European Union. (Master’s thesis), University of Southern Denmark: Department of Political Science and Public Management.

- Reh, C. (2014). Is informal politics undemocratic? Trilogues, early agreement and the selection model of representation. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(6), 822–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.910247

- Reh, C., & Wallace, H. (forthcoming). An institutional anatomy and five policy modes’. In H. Wallace, M. A. Pollack, C. Roederer-Rynning, & A. R. Young (Eds.), Policy-making in the European Union (pp. 68-104). Oxford University Press.

- Rehfeld, A. (2009). Representation rethought: On trustees, delegates, and gyroscopes in the study of political representation and democracy. American Political Science Review, 103(2), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409090261

- Rehfeld, A. (2011). The concepts of representation. American Political Science Review, 105(3), 631–630. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055411000190

- Ripoll Servent, A. (2015). Institutional and policy change in the European Parliament: Deciding on freedom, security and justice. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Ripoll Servent, A. (2018). The European Parliament. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Rittberger, B., & Goetz, K. (2018). Secrecy in Europe. West European Politics, 41(4), 825–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1423456

- Roederer-Rynning, C., & Greenwood, J. (2015). The culture of trilogues. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(8), 1148–1165. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.992934

- Roederer-Rynning, C., & Greenwood, J. (2017). The European Parliament as a developing legislature: Coming of age in trilogues? Journal of European Public Policy, 24(5), 735–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1184297

- Shackleton, M. (2000). The politics of codecision. Journal of Common Market Studies, 38(2), 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00222

- Shackleton, M., & Raunio, T. (2003). Codecision since Amsterdam: A laboratory for institutional innovation and change. Journal of European Public Policy, 10(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176032000058982

- Tallberg, J. (2003). The agenda-shaping powers of the EU Council Presidency. Journal of European Public Policy, 10(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176032000046903

- Warntjen, A. (2010). Between bargaining and deliberation: Decision-making in the Council of the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(5), 665–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501761003748641

Interviews

- Interview 1 with a Permanent Representation of a large member state, 25 September 2017.

- Interview 3 with a Permanent Representation of a medium-sized member state, 25 September 2017.

- Interview 4 with a Permanent Representation of a medium-sized member state, 26 September 2017.

- Interview 5 with a Permanent Representation of a medium-sized member state, 28 September 2017.

- Interview 7 with a Permanent Representation of a medium-sized member state, 28 September 2017.

- Interview 9 with a Permanent Representation of a medium-sized member state, 12 October 2017.

- Interview 10 with a Permanent Representation of a small member state, 26 September 2017.

- Interview 12 with a Permanent Representation of a small member state, 10 January 2019.

- Interview 87 with a Permanent Representation of a large member state, 20 January 2019.

- Interview 88 with a Permanent Representation of a large member state, 23 January 2019.

- Interview 89 with a Permanent Representation of a medium-sized member state, 10 January 2019.

- Interview 90 with a Permanent Representation of a medium-sized member state, 11 January 2019.

- Interview 91with a Permanent Representation of a small member state, 20 January 2019.

- Interview 92 with a Permanent Representation of a medium-sized member state, 23 January 2019.

- Interview 93 with a Permanent Representation of a small member state, 10 January 2019.

- Interview 94 with a Permanent Representation of a small member state, 21 January 2019.

- Interview 95 with a Permanent Representation of a small member state, 22 January 2019.

- Interview 97 with a group of Council Secretariat officials, 9 January 2019.

- Interview 98 with a Council Secretariat official, 22 January 2019.

- Interview 99 with a Council Secretariat official, 22 January 2019.