ABSTRACT

This paper studies frontline workers’ experienced compassion towards clients. The purpose of this study is two-fold. First, it develops a measurement scale for compassion towards clients. Second, it investigates how compassion affects frontline workers and theorizes that compassion may lead to burnout, partly because frontline workers believe that by working overtime to help clients (i.e., coping) adequate services can be provided. Using Structural Equation Modelling (n = 849), this study develops and validates a measurement scale for compassion towards clients with two underlying dimensions: empathic concern and compassionate motivation. These dimensions have opposite effects on a frontline worker’s burnout: while compassionate motivation is negatively related to burnout, empathic concern is positively related to burnout and this effect can be explained because frontline workers work overtime to help clients. The implications for behavioural public policy and administration are discussed.

Introduction

Frontline workers implement public policies while interacting with policy targets (also referred to as clients) (Hill & Hupe, Citation2014; Lipsky, Citation2010). Scholars who take a top-down perspective argue that such face-to-face encounters could be problematic for the accountability of policy outcomes because of the discretion involved. Frontline workers are seen as impersonal actors who act solely on rules and are, in this way, steered towards acting in line with policy outcomes rather than their private interests. Discretion, then, interferes with that impersonal role. However, scholars who take a bottom-up perspective acknowledge that frontline workers cope with stressors, such as limited time, and need discretion to effectively implement policies because they do not match the realities of the citizens they meet (Hill & Hupe, Citation2014; Lipsky, Citation2010; Matland, Citation1995; Thomann et al., Citation2018). In his seminal work, Lipsky (Citation2010) stresses that ‘the reality of the work of [frontline workers] could hardly be farther from the bureaucratic ideal of impersonal detachment in decision making’ (p. 9).

There is a growing body of literature acknowledging and investigating micro-level ‘human factors’ in policy implementation (Moseley & Thomann, Citation2020) by focusing on frontline workers’ emotional responses and associated mechanisms such as emotional labour or emotional intelligence (Edlins, Citation2019; Guy et al., Citation2014; Jensen & Pedersen, Citation2017; Vigoda-Gadot & Meisler, Citation2010). An understudied ‘human factor’ is compassion towards clients. Scholars have rarely pursued compassion as a research end in itself which means little is known about the consequences of experiencing it for policy implementation. Moreover, when compassion is studied, it is often relegated to a supporting role leaving the concept undefined (Eldor, Citation2018). This complicates the generation of cumulative knowledge. This is surprising because scholars have stressed the importance of frontline workers’ compassion towards clients as it contributes to the quality of interactions with clients and policy outcomes (Eldor, Citation2018; Hsieh et al., Citation2012; Strauss et al., Citation2016). Compassion could, for instance, help frontline workers establish a meaningful connection with clients (Cassell, Citation2002). Compassion is even included as a dimension of the widely studied notion of public service motivation (Perry, Citation1996).

This study has two goals. Firstly, this study develops a measurement scale for compassion towards clients. Developing a measurement scale is valuable because robust compassion measures are scarce (Strauss et al., Citation2016) and existing scales measure compassion towards others in general (e.g., Gilbert et al., Citation2017). Frontline workers experience compassion towards specific individuals: their clients. Thus, it remains unclear how frontline workers’ compassion towards clients should be measured. A measurement scale enables future research investigating compassion to build on each other and compare findings more systematically.

We argue that in order to develop this measurement tool, it is needed to conceptually disentangle compassion from a related construct: empathic distress. While compassion is related to the motivation of helping others, empathic distress is related to withdrawal from helping (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011). Notably, a help-oriented relationship (i.e., compassion) between a frontline worker and client is understood to facilitate effective policy implementation (see Pautz & Wamsley, Citation2012). Only some scholars are starting to recognize this conceptual distinction (e.g., Atkins & Parker, Citation2012). However, many do not and confuse their operationalization (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011). Building on insights from psychology and social neuroscience (e.g., Eisenberg, Citation2000; Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011), we show their cognitive, affective and behavioural differences and empirically disentangle the terms by testing their psychometric properties.

Secondly, this study tests the effect of compassion on frontline workers’ when they implement public policies, specifically regarding their burnout. We argue that compassion may result in burnout because the possibility of helping clients is not always present during policy implementation, which can lead to discouragement, frustration, and burnout (Kjeldsen & Jacobsen, Citation2013; Van Loon et al., Citation2015). Moreover, we argue that this effect can be explained because frontline workers believe that, by coping through working overtime, they can provide clients with adequate public services (see Tummers et al., Citation2015). Understanding these effects is important given the high level of burnout among frontline workers (Eldor, Citation2018). Whether or not frontline workers are burned out affects their interactions with clients and, ultimately, whether they can(not) implement policies. Testing the effect of compassion on working overtime to help clients contributes to the understanding of the behavioural consequences of compassion.

Theoretically, we adhere to the call to better understand how micro-level processes translate into policy practices (Moseley & Thomann, Citation2020). Thus, this study adopts a behavioural public policy perspective (see Gofen et al., Citationin press). This focus advances our understanding of the ‘human’ side of policy implementation (e.g., Edlins, Citation2019; Eldor, Citation2018; Guy et al., Citation2014; Hsieh et al., Citation2012; Jensen & Pedersen, Citation2017) by studying the implications of a prominent feeling during policy implementation: compassion. Methodologically, a measurement scale is developed by using a large-scale survey (n = 828). We thus contribute to methodological diversity of behavioural public policy and administration studies by moving beyond the almost sole focus on experimental methods (Bhanot & Linos, Citation2020; Gofen et al., Citationin press).

The structure of this study is as follows. First, the conceptual underpinnings of compassion will be discussed together with the potential effect of compassion on frontline workers’ burnout. After that, the methodological considerations will be highlighted, followed by the statistical results. The study concludes with a discussion of its contribution to policy implementation literature and possible future research directions.

Conceptual framework

While many definitions of compassion exist (see Strauss et al., Citation2016 for an overview), there appears to be consensus that compassion involves feeling touched by a person’s suffering and the subsequent motivation to help them (Strauss et al., Citation2016). For example, Lazarus (Citation1991) defines compassion as ‘being moved by another's suffering and wanting to help’ (p. 289). Similarly, using a systematic review Goetz et al. (Citation2010) define compassion as ‘the feeling that arises in witnessing another's suffering and that motivates a subsequent desire to help’ (p. 351). Compassion is thus generally conceived as a set of subprocesses that involve feeling touched by a person’s suffering, an affective state often referred to as empathic concern (Goetz et al., Citation2010; Strauss et al., Citation2016), and the motivation to help.

Compassion vs. empathic distress

Despite the consensus on the meaning of compassion, many authors seem to confuse compassion with empathic distress (Atkins & Parker, Citation2012; Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011). While both describe an individual’s response to anticipated or observed suffering (Goetz et al., Citation2010), psychology and social neuroscience literature point out that they exist out of different cognitive, affective, and behavioural components (e.g., Eisenberg, Citation2000; Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011).

Compassion and empathic distress differ in the perspective that is taken towards another’s suffering and thus involves different cognitive processes. When experiencing empathic distress, one identifies with the sufferer by adopting their emotional state and thus takes on a self-perspective towards suffering (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011). Empathic distress and the lessened self-other distinction are linked to poor emotion regulation as one is not able to regulate the distress of another (Eisenberg et al., Citation1994). When experiencing compassion, an individual is aware that it is the other person who is suffering, and thus involves an ‘other-oriented focus’ (Eisenberg et al., Citation2015). The other-oriented focus of the compassionate response prevents identifying with the sufferer (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011).

The affective components of compassion and empathic distress reflect their difference in emotional states. Empathic distress involves the self-related emotion personal distress and is accompanied by feelings of discomfort, tension, and anxiety as one is overwhelmed by the vicariously induced negative emotions threatening the self (Davis, Citation1980; Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011). Compassion involves the other-related emotion accompanied by feelings of warmth towards another's suffering (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011). This affective state underlying compassion is often referred to as empathic concern (e.g., Goetz et al., Citation2010; Strauss et al., Citation2016). In short, it can be said that empathic distress entails feeling with and compassion entails feeling for the other.

Several studies have pointed out that individuals who experience compassion show more helping behaviour than those who experience empathic distress (e.g., Eisenberg, Citation2000; Lamm et al., Citation2007). When experiencing empathic distress, one will most likely try to reduce the damaging feelings and attempt to withdrawal from the difficult emotional situation – even if that means losing the opportunity to provide help (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011). Compassion, on the other hand, involves feelings of motivation to help the sufferer (Goetz et al., Citation2010). The realization of being different from the suffering person without being indifferent towards him or her enables the development of prosocial behaviour (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011).

Despite their differences, scholars seem to confuse compassion and empathic distress (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011). We will use two examples to illustrate that the confusion of compassion and empathic distress is apparent in the literature and is a problem that occurs across disciplines. The first example is the concept of Public Service Motivation (PSM). Together with the attraction to public policy, commitment to the public, and self-sacrifice, compassion makes up the construct of PSM (Perry, Citation1996). Many authors build on Perry (Citation1996), who views compassion as an emotional response and identification with others that motivates individuals to help others (e.g., Van Loon, Citation2016). However, as argued above, the identification with others belongs to the cognitive component underlying empathic distress. Subsequently, the identification with others will not act as a driver to help others but will lead to a feeling of wanting to withdrawal from helping. Furthermore, the PSM scale developed by Perry (Citation1996) contains the item on compassion ‘It is difficult for me to contain my feelings when I see people in distress’, which may capture empathic distress more than compassion, as compassion is accompanied by a certain distress tolerance.

The second example is the concept of compassion fatigue. This term is used to describe emotional, physical and social exhaustion overtaking a person and causing a decline in his or her desire and ability to feel and care for others (McHolm, Citation2006). Compassion fatigue is said to occur when one closely identifies with another and absorbs their person’s trauma or pain (McHolm, Citation2006). This indicates that compassion fatigue involves the adoption of another’s emotional state. This is part of the cognitive component underlying empathic distress, and not compassion. While some authors have started to suggest a change in terminology to empathic distress fatigue rather than compassion fatigue (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011; Dowling Citation2018), many authors continue to use the conceptualization of compassion fatigue (e.g., Schott & Ritz, Citation2018).

Damaging effect of compassion on frontline workers

Experiencing compassion could benefit both policy outcomes and frontline workers. Compassion enables frontline workers to feel more connected to the clients they interact with (Cassell, Citation2002) and are, thus, able to help them more effectively (see Moseley & Thomann, Citation2020). Compassion results in feelings of fulfilment when the motivation to alleviate one’s suffering can be achieved, also known as ‘compassion satisfaction’ (Radey & Figley, Citation2007). Compassion is, thus, often linked to improved mental health (e.g., Singer & Klimecki, Citation2014).

Despite the benefits compassion could entail, we argue that the literature overlooks the potential costs of compassion in the specific policy circumstances of frontline workers. The practical reality of many frontline workers is that they rarely have the time, information, or resources to help all clients during policy implementation because of their severe workloads or red tape (Kjeldsen & Jacobsen, Citation2013; Lipsky, Citation2010; Tummers et al., Citation2015). Not being able to know, with any certainty, if you are succeeding to help a client can trigger anxiety, stress, and frustration (Van Loon et al., Citation2015). This especially applies to policy areas that are very client-intensive (see Dörrenbächer, Citation2017) or are characterized by difficulty of measuring indicators of change, difficulty in seeing signs of success or when actual alleviation of suffering is not possible (Hasenfeld, Citation1983). The reality of being motivated to help clients because you experience compassion but failing to see policy results could thus take its toll and lead to burnout among frontline workers. In this way, experiencing compassion by frontline workers can result in negative employee outcomes because it results in burnout.

H1: Frontline workers’ compassion towards clients leads to burnout

Altogether, frontline workers’ compassion but failing to see results, could result in stress. Lipsky (Citation2010) introduced ‘coping’ to understand how frontline workers deal with the stress during policy implementation. Coping during public service delivery is defined as the ‘behavioural efforts frontline workers employ when interacting with clients, in order to master, tolerate or reduce external and internal demands and conflicts they face on an everyday basis’ (Tummers et al., Citation2015, p. 1100). Examples of coping strategies are breaking rules or cynicism towards work. Tummers et al. (Citation2015) identify three ways of coping of which moving towards clients entailed the largest number of coping strategies. Moving towards clients entails that frontline workers ‘pragmatically adjust to the client’s needs, with the ultimate aim to help them’ (Tummers et al., Citation2015, p. 1108).

Moving towards clients corresponds to the notion of compassion because the motivation to engage in the suffering and help to alleviate it also suggests a direction towards clients (see also Moseley & Thomann, Citation2020). An important coping strategy to help clients is using personal resources which entails that frontline workers invest energy beyond their job description to help clients and alleviate their suffering. Working overtime is such a personal resource (Tummers et al., Citation2015). Frontline workers might invest more time in helping clients to provide them with support and see signs of success (see Maslach et al., Citation2001). In this way, working overtime may be positive for the clients of frontline workers but have negative effects on the workers themselves making them less capable of achieving policy outcomes. Going ‘above and beyond’ is a known trigger for burnout (Maslach et al., Citation2001; Van Loon et al., Citation2015). Moreover, when working overtime does not result in the client being helped it may amplify frustration. Hence, working overtime might partly explain the positive relationship between compassion and burnout.

H2: Working overtime to help clients mediates the positive relationship between a frontline worker’s compassion towards clients and burnout

Methods

Research setting

Frontline workers were studied at a large (>7000 employees), Christian non-profit social work organization in The Netherlands. The social workers provide direct care to clients and hold functions such as doctors, youth workers, psychiatrists and nurses. This social work organization is an appropriate context because social workers are classic frontline workers. They implement public policies, have face-to-face contact with clients, and have discretion (Lipsky, Citation2010). Moreover, despite it being a non-profit organization, the social work organization is almost exclusively funded by public funds, and their work resembles the practice of public social workers. A non-profit organization providing a public task like this is common (Zacka, Citation2017) and has been studied as such (e.g., Thomann et al., Citation2018).

Data collection

Data were collected through a large-scale survey. Together with the HR-manager, social workers with direct contact with clients were identified (N = 4128). A survey was distributed in May 2020 via e-mail and a reminder was sent after a week. In the introduction, the study purpose was stated and voluntary and anonymity were stressed. The response rate was 26.6% (n = 1099). 17 respondents did not give consent for participation and a total of 233 respondents were excluded from analysis because they filled in less than 50% of the questionnaire. The total sample was 849 respondents.

Sample

Online Appendix 1 gives an overview of the characteristics of the sample and of the total population. This shows that, for gender and age, the sample is representative. No data was available for the population's education level, number of years as a social worker, or number of hours of client contact in a week, making it impossible for checking representability. This should be taken into account when interpreting the findings.

Measures

Before distributing the survey, key measures for variables were tested using cognitive interviews among five social workers. This led to minor adjustments. All items were measured on a 1–5 Likert scale and can be found in Online Appendix 2.

Compassion. Compassion was measured by combining two scales. The first scale selected is of Gilbert et al. (Citation2017) and focuses on the motivational aspect of compassion and includes ten items. As empathic concern is treated as the other subprocess underlying compassion (Strauss et al., Citation2016), the scale of Davis (Citation1980) on empathic concern was included. The second scale selected is of Davis (Citation1980) and measures empathic concern. Important to note is that both scales focus on compassion/concern to others in general, while this study focuses on frontline worker’s compassion towards clients. All items were adjusted by changing ‘others’ to ‘clients’.

Empathic distress. Empathic distress was measured using Davis (Citation1980) personal distress scale. Using seven items, this scale focuses on feelings of anxiety and wanting to withdrawal from helping when confronted with the suffering.

Burnout. Burnout was measured by using the emotional exhaustion dimension of the Maslach Burnout Inventory scale (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981). Emotional exhaustion refers to feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one's work (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981) and is a wide-spread measure of burnout (e.g., Van Loon et al., Citation2015).

Working overtime to help clients. Working overtime to help clients was measured by asking how many hours respondents, during an average workweek, work overtime to help clients.

Control variables. Gender, age, level of education, years of experience, and the number of client contact hours in a week were added as control variables. They were added because research shows that social workers with more client contact and more years of experience have a higher risk of burnout (Yu et al., Citation2016).

Common source bias

Online Appendix 3 shows the design and post hoc statistical remedies used which indicate that common source bias did not substantially impact our findings (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Analysis

The statistical program R was used. The data slightly diverges from multivariate normality. Therefore, the Satorra-Bentler correction for the maximum likelihood estimation was used to calculate parameters (Satorra & Bentler, Citation1994).

Results

Factor analyses

To test the difference between compassion and empathic distress, the psychometric properties of the scales were tested using factor analysis. The factor structure was tested using (1) Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and (2) Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Following Osborne and Fitzpatrick (Citation2012), internal replication was used to ensure robust findings. Therefore, the sample was randomly split in half with the first half used for EFA (1n = 427) and the second half for CFA (2n = 422).

First, for the EFA, oblique rotation was used, and factors were thus allowed to correlate. Based on the scree plot and theoretical interpretations of factors, a three-factor model was identified. Seven items were omitted because they had factor loadings below 0.3 (Field, Citation2013). shows the full wording of each item.

Table 1. Explorative factor analyses (1n = 427)

The first factor identified contains items addressing one’s motivation to engage with a client’s suffering and to alleviate this suffering. This factor grasps the behavioural component underlying compassion of the motivation to help (Goetz et al., Citation2010). Therefore, this factor was labelled ‘compassionate motivation’. The second factor contains items regarding feelings of being emotionally moved by and concerned for clients’ suffering. This factor grasps the affective component underlying compassion of feeling emotionally touched by a person’s suffering (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011). As this affective state is often referred to as empathic concern (e.g., Strauss et al., Citation2016), this factor was labelled as such. The third factor identified contains items regarding stress resulting from being confronted with clients’ suffering and the feeling of wanting to withdrawal from helping when confronted with clients’ suffering. This factor grasps the affective and behavioural processes underlying empathic distress (Klimecki & Singer, Citation2011), and was labelled accordingly.

In sum, the three factors identified are (1) compassionate motivation, (2) empathic concern, and (3) empathic distress. The first and second factors grasp two subprocesses underlying compassion as described in the literature: feeling touched by a person’s suffering (part of the factor of empathic concern) and the motivation to help (part of the factor compassionate motivation) (Strauss et al., Citation2016). For this reason, these factors are treated as two underlying dimensions underlying compassion.

Second, the model fit of the CFA was assessed using the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The model fit (χ2 = 239.642, df = 116) is good with CFI = 0.938, TLI = 0.927, RMSEA = 0.047, and SRMR = 0.062. All items loaded significantly on the latent variables (p <.001) with standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.424 and 0.755.

Reliability and validity

The internal consistency reliability of a measurement scale concerns the homogeneity of items (DeVellis, Citation2016). The fit indices pass the recommended thresholds. Moreover, McDonald’s omegaFootnote1 was high for compassionate motivation (ω = 0.87) and empathic distress (ω = 0.84), and acceptable for empathic concern (ω = 0.66). Hence, the fit indices and McDonald’s omega indicate good internal consistency reliability.

Regarding validity, it is expected that compassionate motivation, empathic concern, and empathic distress significantly correlate because they measure related dimensions of compassion or a related construct. Online Appendix 4 confirms that all variables correlate significantly. First, empathic concern and compassionate motivation are positively correlated (r = 0.146, p = 0.003). This confirms that they are underlying dimensions of compassion. A frontline worker’s compassion towards clients is thus made up of the way s/he varies along these two dimensions.

Second, empathic distress and compassionate motivation are negatively correlated (r = −0.297, p = 0.000). This indicates that the more empathic distress a social worker experiences in reaction to suffering, the less compassionate motivation s/he experiences, and vice versa. This is in line with theory because empathic distress is expected to be accompanied by feelings of wanting to withdrawal from helping, and not in the motivation to help. In addition, it is expected that those with more compassionate motivation have a certain degree of distress tolerance that protects them from experiencing empathic distress (Gilbert et al., Citation2017).

Third, empathic concern and empathic distress are positively correlated (r = 0.241, p = 0.000). This means that the more empathic concern a social worker experiences towards a client, the more empathic distress s/he will experience, and vice versa. Empathic concern is thus positively related to both compassionate motivation and empathic distress. This is surprising, as it was expected that empathic concern would be positively related to feelings of motivation to help (i.e., compassion) and not to feelings of anxiety and wanting to withdrawal from helping (i.e., empathic distress). The findings thus show that the dimensions of compassion have opposite relationships with empathic distress; compassionate motivation is negatively related and empathic concern is positively related to empathic distress.

Structural Equation Modelling

SEM (n = 828Footnote2) was used to test how compassion impacts social workers’ burnout. SEM was used because of the latent nature of the dependent and independent variables and the multiple regressions hypothesized. Online Appendix 5 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations. It is noteworthy that the social workers score higher on compassionate motivation (M = 4.257, SE = 0.401) and empathic concern (M = 3.136, SE = 0.552) than on empathic distress (M = 1.880, SE = 0.492). Only control variables that correlate significantly with both independent and dependent variables were included in the model to ensure that only control variables that explain covariation were included.

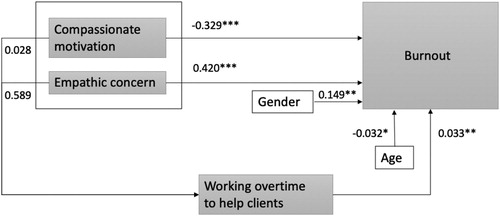

Regarding the SEM analyses, the initial model (χ2 = 764.666, df = 224, p = 0.000) had no acceptable fit (CFI = 0.898, TLI = 0.886, RSMEA = 0.053, and SRMR = 0.56). Its modification indices were used to identify ways to increase the model fit. This approach is recommended and suitable within the boundaries of relevant theory (Kline, Citation2013). Six covariances between residuals of burnout were added as these items all represent experienced burnout.Footnote3 The similarity on the items is also shown by the high omega (ω = 0.9) which indicates items are redundant (Streiner, Citation2003). In addition, two covariances between residuals of compassionate motivation were added, as they represent motivation to alleviate a client’s suffering.Footnote4 The model fit (χ2 = 536.319, df = 216.000, p = 0.000) improved, with CFI = 0.941, TLI = 0.932, RSMEA = 0.041, and SRMR = 0.052. and show the results of SEM analysis.

Table 2. Results of Structural Equation Modelling (n = 828).

Hypothesis 1 predicted that frontline workers’ compassion towards clients leads to burnout. When testing the psychometric properties of the compassion and empathic distress scales, it was found that compassionate motivation and empathic concern are distinct dimensions of compassion. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was tested twice; once for compassionate motivation and once for empathic concern. Empathic concern is positively related to burnout (z = 4.752, st.B = 0.420, st.SE = 0.073, p = 0.000). This means that when a frontline worker experiences more empathic concern, they also experience more burnout. Hypothesis 1 is accepted for the empathic concern dimension of compassion. However, compassionate motivation is negatively related to burnout (z = −4.779, st.B = −0.329, st.SE = 0.069, p = 0.000) meaning: the greater compassionate motivation, the less burnout social workers experience. Hypothesis 1 is rejected for the compassionate motivation dimension of compassion.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that working overtime would mediate the positive relationship between frontline workers’ compassion towards clients and burnout. This hypothesis was also tested for both compassion dimensions. Empathic concern is not significantly related to working overtime (z = 2.985, st.B = 0.589, st.SE = 0.341, p = 0.084). Working overtime is positively related to burnout (z = 2.985, st.B = 0.033, st.SE = 0.011, p = 0.003) and the total indirect effect of working overtime is significant (z = 2.419, st.B = 0.019, st.SE = 0.008, p = 0.015). This shows that the positive relationship between empathic concern and burnout can be partly explained by working overtime. Hypothesis 2 is confirmed for the empathic concern dimension. However, compassionate motivation is not related to working overtime (z = 0.072, st.B = 0.028, st.SE = 0.390, p = 0.943). Working overtime is positively related to burnout (z = 2.985, st.B = 0.033, st.SE = 0.011, p = 0.003), but the total indirect effect of working overtime is not significant (z = 0.071, st.B = 0.001, st.SE = 0.013, p = 0.944). Working overtime thus does not help explain the effect of compassionate motivation on burnout. Hypothesis 2 is rejected for the compassionate motivation dimension.

In sum, the findings suggest that the two dimensions of compassion have opposite effects on burnout. Empathic concern is positively related to burnout and mediated by working overtime. Compassionate motivation, on the other hand, is negatively related to burnout and working overtime does not mediate this relationship. Hypothesis 1 and 2 are confirmed only for the empathic concern-component of compassion.

Conclusion and discussion

The purpose of this study was two-fold, namely (1) develop a measurement scale for compassion towards clients and; (2) test the effect of compassion on frontline workers’ burnout. The findings contribute to the literature in four ways.

First, this study developed a measurement scale for frontline workers’ compassion towards clients. This measurement scale allows scholars to systematically compare the effects of- and on compassion towards clients. Public administration and public policy scholars are increasingly creating high-quality measurement scales (e.g., de Boer, Citation2019). However, behavioural public policy has not caught up. The state of the art has been criticized for its methodological singularity (Bhanot & Linos, Citation2020). Compassion towards clients is, however, a perceptual measure making surveys a suitable method. This study shows that using surveys is appropriate to study behavioural topics. Future research focusing on frontline workers’ perceptions would benefit from using methods beyond experiments because they can facilitate our understanding of micro-level variations during policy implementation.

Second, this study contributes to understanding the emotional side of policy implementation (e.g., Edlins, Citation2019; Eldor, Citation2018; Guy et al., Citation2014; Jensen & Pedersen, Citation2017; Moseley & Thomann, Citation2020) by showing that compassion is distinct from empathic distress. Future research on compassion would benefit from clearly differentiating between the two because it could explain why some scholars find that compassion leads to positive wellbeing outcomes for frontline workers (e.g., Singer & Klimecki, Citation2014) and others to negative ones (e.g., Radey & Figley, Citation2007). More importantly, this study revealed that compassion is multi-dimensional and consists of empathic concern and compassionate motivation. While compassion scholars treat both these dimensions as part of compassion (e.g., Gilbert et al., Citation2017; Goetz et al., Citation2010; Strauss et al., Citation2016), existing compassion scales do not differentiate between them. In addition, scholars measuring compassion seem to use items related more to empathic concern (Van Loon, Citation2016) or compassionate motivation (Gilbert et al., Citation2017), and, this way, do not fully capture compassion.

In this line of reasoning, the third contribution of this study concerns the importance of differentiating between the dimensions of compassion as the findings indicate that they have opposite effects on frontline workers’ burnout. Frontline workers’ empathic concern increases burnout because a rise in concern for clients’ suffering (i.e., empathic concern) results in working overtime which, in turn, increases burnout risk. However, compassionate motivation decreases burnout. These opposing effects have important implications for policy implementation because it indicates that compassion can both harm and help effective policy implementation by affecting frontline workers’ wellbeing. Future research could also explore the effects of compassion on frontline workers’ perceptions of clients (e.g., Jilke & Tummers, Citation2018) or feelings of connection (e.g., Cassell, Citation2002).

A potential explanation for the opposing effects can be found in the literature on compassion satisfaction (Radey & Figley, Citation2007). Compassion satisfaction entails the fulfilment one experiences when feeling successful in doing their job (Radey & Figley, Citation2007). It could be that the concern-component of compassion is what social workers experience as an emotional ‘burden’ for themselves. The motivation-component of compassion, however, could be what gives social workers gratification and job satisfaction. This implies that the context of the social work organization in which frontline workers are studied contributed to the possibilities for helping clients more than was anticipated. Empirical evidence suggests that compassionate satisfaction can work as a buffer to burnout (Samios, Citation2018). This implies that boosting frontline workers’ compassionate motivation can buffer against burnout.

Finally, Moseley & Thomann (Citation2020) argued that – as opposed to its sister discipline public administration – the policy implementation literature has not paid enough attention to frontline workers’ (perceived) behaviour during policy implementation. Moseley & Thomann (Citation2020) stress that one important explanation for understanding frontline workers are individual attributes, such as their feelings. Our study, indeed, empirically shows that frontline workers’ compassion towards clients is important to understand for policy implementation scholars. If frontline workers feel burned out because of their compassion towards clients this could result in less effective interactions with policy targets and, ultimately, not achieving policy outcomes. Future research needs to continue dissecting the effects of frontline workers’ individual attributes such as compassion to fully understand the consequences for policy implementation. In addition, this study set a first step in understanding the effect of compassion on frontline workers’ behaviour: working overtime. Further research focusing on frontline workers’ behaviour such as productivity or exercise of discretion may be particularly fruitful.

This study, like any other, has limitations. First, we studied solely the negative effects for burnout of compassion towards clients. Hereby we aimed to provide a more nuanced view of the consequences of compassion and, next to its benefits, pay attention to its potential harming effect it can have for frontline workers. We tested the potential harming effect of compassion in the policy context of social work, whose core purpose is to provide care to those in need (Radey & Figley, Citation2007). Social workers may, therefore, feel that they are unable to help clients sooner than other types of frontline workers. It could be that in other, policy contexts compassion towards clients may have positive effects and reduce burnout. Future research could further investigate positive effects of compassion on frontline workers’ burnout. The immigration policy context may be especially relevant to start with since frontline workers have considerable discretion potentially amplifying their abilities to help their clients (see Dörrenbächer, Citation2017).

Third, as mentioned in the introduction, we took a behavioural and, thus, micro-level perspective in our study. However, both frontline workers’ compassion towards clients and burnout may also be prone to structural factors. Future research could delve into structural factors such as support from supervisors and peers (e.g., Eldor, Citation2018) or social constructions of clients which could ‘trigger’ compassion (see Jensen & Pedersen, Citation2017; Jilke & Tummers, Citation2018). Fourth, this study is cross-sectional in nature. Cross-sectional designs cannot establish causality or identify long-term effects. Future research looking to establish causal effects of compassion towards clients could use experimental methods. Finally, data was collected during the Covid-19 crisis. When interpreting the results, one should keep in mind that the pandemic potentially affected respondents. Social work could be more emotionally demanding because one, for example, worries about clients getting ill or about their own and their family's health.

Despite these limitations, this study is a first step in measuring and understanding frontline workers’ compassion towards clients and its effects on their wellbeing. As such it encourages other scholars to continue to gain more understanding of compassion, and, while doing so, paying attention to its essential role in the process of policy implementation.

Supplemental Material

Download Rich Text Format File (221.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. Lars Tummers for his helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article as well as the anonymous reviewers and editors for their helpful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emma Ropes

Emma Ropes is PhD Candidate at the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR).

Noortje de Boer

Dr. Noortje de Boer is Assistant Professor Public Management at School of Governance at Utrecht University.

Notes

1 McDonald’s omega is reported because Cronbach’s alpha has been critiqued for over- and underestimation (Sijtsma, Citation2009).

2 Because the Santorra Bentler correction was used for the maximum likelihood estimation to calculate parameters, the analysis could only run on complete data. Therefore, all missing data were excluded from the analysis, which results in an n of 828.

3 Allowed covariances were EE4-EE8, EE1-EE2, EE5-EE9, EE2-EE9, EE2-EE3, and EE6-EE7.

4 Allowed covariances were CA1-CA3 and CA2-CA3.

References

- Atkins, P. W., & Parker, S. K. (2012). Understanding individual compassion in organizations: The role of appraisals and psychological flexibility. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 524–546. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0490

- Bhanot, S. P., & Linos, E. (2020). Behavioral public administration: Past, present, and future. Public Administration Review, 80(1), 168–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13129

- Cassell, E. J. (2002). Compassion. In C. R. Synder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 434–445). Oxford University Press.

- Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology.

- de Boer, N. (2019). Street-level enforcement style: A multidimensional measurement instrument. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(5), 380–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2018.1465954

- DeVellis, R. F. (2016). Scale development: Theory and applications (Vol. 26). Sage.

- Dörrenbächer, N. (2017). Europe at the frontline: Analysing street-level motivations for the use of European Union migration law. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(9), 1328–1347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1314535

- Dowling, T. (2018). Compassion does not fatigue. The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 59(7), 749.

- Edlins, M. (2019). Developing a model of empathy for public administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2019.1700459

- Eisenberg, N. (2000). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 665–697. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.665

- Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Murphy, B., Karbon, M., Maszk, P., Smith, M., O'Boyle, C., & Suh, K. (1994). The relations of emotionality and regulation to dispositional and situational empathy-related responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(4), Article 776. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.4.776

- Eisenberg, N., Van Schyndel, S. K., & Hofer, C. (2015). The association of maternal socialization in childhood and adolescence with adult offsprings’ sympathy/caring. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038137

- Eldor, L. (2018). Public service sector: The compassionate workplace—The effect of compassion and stress on employee engagement, burnout, and performance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(1), 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mux028

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage.

- Gilbert, P., Catarino, F., Duarte, C., Matos, M., Kolts, R., Stubbs, J., Ceresatto, L., Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Basran, J. (2017). The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(1), 4.

- Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018807

- Gofen, A., Moseley, A., Thomann, E., & Weaver, R. K. (in press). Behavioural governance in the policy process: Comparative multi-level perspectives. Special Issue Journal of European Public Policy.

- Guy, M. E., Newman, M. A., & Mastracci, S. H. (2014). Emotional labor: Putting the service in public service. Routledge.

- Hasenfeld, Y. (1983). Human service organizations. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Hill, M., & Hupe, P. (2014). Implementing public policy. Sage.

- Hsieh, C. W., Yang, K., & Fu, K. J. (2012). Motivational bases and emotional labor: Assessing the impact of public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 72(2), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02499.x

- Jensen, D. C., & Pedersen, L. B. (2017). The impact of empathy—explaining diversity in street-level decision-making. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 27(3), 433–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muw070

- Jilke, S., & Tummers, L. (2018). Which clients are deserving of help? A theoretical model and experimental test. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(2), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy002

- Kjeldsen, A. M., & Jacobsen, C. B. (2013). Public service motivation and employment sector: Attraction or socialization? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(4), 899–926. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mus039

- Klimecki, O., & Singer, T. (2011). Empathic distress fatigue rather than compassion fatigue? Integrating findings from empathy research in psychology and social neuroscience. In B. Oakley, A. Knafo, G. Madhavan, & D. S. Wilson (Eds.), Pathological altruism (pp. 368–383). Oxford University Press.

- Kline, R. B. (2013). Assessing statistical aspects of test fairness with structural equation modelling. Educational Research and Evaluation, 19(2–3), 204–222.

- Lamm, C., Batson, C. D., & Decety, J. (2007). The neural substrate of human empathy: Effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisal. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.1.42

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46(8), Article 819. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

- Matland, R. E. (1995). Synthesizing the implementation literature: The ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 5(2), 145–174.

- McHolm, F. (2006). Rx for compassion fatigue. Journal of Christian Nursing, 23(4), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005217-200611000-00003

- Moseley, A., & Thomann, E. (2020). A behavioural model of heuristics and biases in frontline policy implementation. Policy & Politics, 49(1). https://doi.org/10.1332/030557320X15967973532891

- Osborne, J. W., & Fitzpatrick, D. C. (2012). Replication analysis in exploratory factor analysis: What it is and why it makes your analysis better. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 17(1), 15.

- Pautz, M. C., & Wamsley, C. S. (2012). Pursuing trust in environmental regulatory interactions: The significance of inspectors’ interactions with the regulated community. Administration & Society, 44(7), 853–884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399711429108

- Perry, J. L. (1996). Measuring public service motivation: An assessment of construct reliability and validity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 6(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024303

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), Article 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Radey, M., & Figley, C. R. (2007). The social psychology of compassion. Clinical Social Work Journal, 35(3), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-007-0087-3

- Samios, C. (2018). Burnout and psychological adjustment in mental health workers in rural Australia: The roles of mindfulness and compassion satisfaction. Mindfulness, 9(4), 1088–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0844-5

- Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In A. von Eye & C. C. Clogg (Eds.), Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research (pp. 399–419). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Schott, C., & Ritz, A. (2018). The dark sides of public service motivation: A multi-level theoretical framework. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 1(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvx011

- Sijtsma, K. (2009). On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika, 74(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0

- Singer, T., & Klimecki, O. M. (2014). Empathy and compassion. Current Biology, 24(18), R875–R878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.054

- Strauss, C., Taylor, B. L., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F., & Cavanagh, K. (2016). What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004

- Streiner, D. L. (2003). Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80(1), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18

- Thomann, E., Hupe, P., & Sager, F. (2018). Serving many masters: Public accountability in private policy implementation. Governance, 31(2), 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12297

- Tummers, L. L., Bekkers, V., Vink, E., & Musheno, M. (2015). Coping during public service delivery: A conceptualization and systematic review of the literature. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(4), 1099–1126. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu056

- Van Loon, N. M. (2016). Is public service motivation related to overall and dimensional work-unit performance as indicated by supervisors? International Public Management Journal, 19(1), 78–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2015.1064839

- Van Loon, N. M., Vandenabeele, W., & Leisink, P. (2015). On the bright and dark side of public service motivation: The relationship between PSM and employee wellbeing. Public Money & Management, 35(5), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2015.1061171

- Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Meisler, G. (2010). Emotions in management and the management of emotions: The impact of emotional intelligence and organizational politics on public sector employees. Public Administration Review, 70(1), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02112.x

- Yu, H., Jiang, A., & Shen, J. (2016). Prevalence and predictors of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among oncology nurses: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 57, 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.01.012

- Zacka, B. (2017). When the State Meets the Street. Harvard University Press.