?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Whether territorial (intergovernmental) decision rules adversely impact the policy-opinion link is a controversial topic, and unresolved in part due to a lack of empirical evidence. This study leverages the European Union's (EU) codecision reform – introduced to tackle the EU's democratic deficit – to evaluate whether it caused EU policies to better track public opinion (mood).. The analysis links an original dataset of ideologically scaled EU policies with existing datasets on European public opinion (1990–2008) and applies the difference-in-differences (DiD) causal inference design. The study finds that EU policies adopted under codecision more closely track European public opinion shifts. The finding supports the argument that territorial legislative procedures can hurt the democratic legitimacy of public policies. This has significant implications for the reform of the EU and of global governance, and contributes to the broader field of political representation and the debate on territorial representation.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) adopted the codecision reform in order to make the EU more democratic (Hix & Høyland, Citation2013; Rittberger, Citation2012). Has codecision, which weakened intergovernmentalism in EU decision-making, improved the democratic credentials of the EU? In particular: has codecision caused EU policy outputs to better track the policy preferences of European citizens? According to the liberal intergovernmentalist (LI) account, territorial decision-making does not harm responsiveness to European public opinion (Carrubba, Citation2001; Moravcsik & Schimmelfenning, Citation2019). The ‘indirect democratic control’ via national governments is seen as ‘sufficient for responsiveness to European citizens’ (Moravcsik, Citation2002, p. 602).

Others are less optimistic. According to the liberal tradition in democratic theory, territorial representation – by clustering individuals in inflexible, non-voluntary groups – breaches several democratic principles, and notably: the principle of equal respect (i.e., one person-one vote); the principle of individual autonomy; and the principle of affected interests (Christiano, Citation2018; Dahl, Citation1989; Goodin, Citation2007; Held, Citation2006; Mill, Citation1869; Shapiro, Citation1999). Following this argument, democracies should adopt decision-making rules that weigh personal/individual representation more heavily than territorial representation (Rehfeld, Citation2005, Citation2008). This speaks to some EU-specific critiques of intergovernmentalism on representative grounds (Hix, Citation2018; Kleine et al., Citation2022).

To adjudicate between the optimistic LI account and that of territorial representation sceptics, the article examines the causal effect of the 1999 introduction of the codecision reform on the policy-opinion link in EU employment and social policy. This policy area was chosen for its salience, and because of the discontinuity offered by the entry into force of the Amsterdam Treaty, which directly substituted cooperation with codecision in the subset of employment and social policies that were assigned the cooperation legal basis pre-1999. I first scale EU policies on the pro-worker vs. pro-business dimension via crowdsourced text analysis (Benoit et al., Citation2016). I then compare policies' scores with public opinion preferences (using both the Eurobarometer as well as Caughey et al.'s (Citation2019) dataset on European public opinion). I then run a difference-in-differences (DiD) analysis leveraging the 1999 application of codecision to only a subset of EU employment and social policy dossiers – i.e., those that were assigned the cooperation legal basis before 1999. DiD allows to establish causality by comparing pre-post change with treatment-control change (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2008). Cooperation/codecision dossiers will therefore be compared to consultation dossiers pre- and post-1999.

It is important to note that codecision weakens but does not supplant intergovernmental decision-making in the EU: the Council of the EU remains a powerful veto player under this decision-making procedure as well. This notwithstanding, the analysis detects important signals that codecision indeed leads EU policies to more closely track shifts in European public opinion – even under this very conservative test.

The findings suggest that tempering territorial representation can help deliver policies that better track the direction of public preferences (the public opinion mood). This has implications for domestic politics – especially for systems that rely strongly on territorial representation. It also has significant implications for global governance institutions, currently dominated by inter-state bargaining and intergovernmental decision-making (Duina & Lenz, Citation2017; Lenz & Marks, Citation2016) and suffering public backlash as their policy competences have been expanded to include salient, redistributive policy domains (Rittberger & Schroeder, Citation2016; Zürn, Citation2014). Assessing which decision rules can improve the democratic legitimacy of global governance decisions is therefore highly relevant.

Measuring the policy-opinion link is the fundamental test of democracy (Dahl et al., Citation2003; May, Citation1978) – yet, analyses of such a link are in short supply (Powell, Citation2004; Wlezien, Citation2017), particularly so in analyses of global governance institutions (Wratil, Citation2018; Zürn, Citation2014). Examining the EU policy-opinion link addresses significant open questions in EU studies, such as (a) the democratic deficit argument that the EU is incapable of delivering policies that are responsive to the preferences of Europeans (Follesdal & Hix, Citation2006; Hix, Citation2008; Schmitter, Citation2000); (b) whether codecision influences the democratic legitimacy of EU policies (Burns et al., Citation2013). Some studies have evaluated the EU policy-opinion link (Crombez & Hix, Citation2015; Toshkov, Citation2011; Wratil, Citation2018), but they do not directly measure the left-right position of EU policy outputs. A further innovation of this study lies in the application of causal inference to examine the role played by legislative procedures – and, in particular, territorial decision rules – in the deterioration of the policy-opinion link. This contributes to the broader field of political representation as well (Rasmussen et al., Citation2019).

Territorial decision-making and the policy-opinion link

Institutions of territorial representation are common in representative democracies. Whilst territorial representation does not enjoy normative standing as a democratic principle, it is an ingenious solution to information and participation costs, inherited from the pre-modern era (Rehfeld, Citation2005). Territorial representation is thus appropriate insofar as it is aimed at enriching the policy consultation and formulation phases, and/or to allocate policy competences effectively in federal polities (Filippov et al., Citation2004; Rehfeld, Citation2005). Territorial institutions are, in fact, often established for informational, deliberative and participatory purposes, and tend to have weaker law-making powers. By way of example, in most bicameral systems the territorial ‘upper’ chamber typically decides by majority voting (i.e., is ‘weakly territorial’) and is granted only limited legislative powers (Russell, Citation2001).

The territorial principle is expected to introduce democratic deficits when it fundamentally shapes decision-making procedures (Rehfeld, Citation2005). This is because – according to the principle of affected interests – democratic policy-making processes have to guarantee equal influence to everyone that is going to be bound by the policy (Archibugi, Citation2010; Dahl, Citation1989; Rehfeld, Citation2005, Citation2008). According to liberal democratic theory, the simple aggregation of individual interests bestows democratic legitimacy to a decision (Christiano, Citation2018; Dahl, Citation1989; Goodin, Citation2007). Democratic decision-making institutions should, therefore, be designed to be representative of the relevant stakeholder and use simple majority rules – which guarantee equal influence (Dahl et al., Citation2003; Rae & Taylor, Citation1971). Grouping individuals into inflexible, non-voluntary constituencies may only be justified for policy areas where the individual is not the primary affected interest, and/or for issues where territory-based minorities need to be protected (Dahl, Citation1989; Shapiro, Citation1999). Territorial vetoes are less appropriate for policy areas that have direct implications for individual citizens – i.e., redistributive policy areas, such as employment and social policy, which are now increasingly falling under global governance competences (Rittberger & Schroeder, Citation2016).

Institutions of global governance typically make laws via decision rules that give prominence to territorial units. The decision-taker – or stakeholder – is assumed to be the nation state, and as such, global governance institutions adopt unanimity or super-majoritarian voting, in which member states retain significant veto powers. The assumption in such contexts is that such legislative procedures are legitimate because they preserve national sovereignty, and ‘demoicracy’ (Cheneval & Schimmelfenning, Citation2013). Liberal intergovernmentalism (LI), for example, sees international organisations' reliance on territorial decision-making as meeting democratic representation and legitimacy requirements. According to this view, domestic public opinion gets faithfully aggregated by national ministers first, and then subsequently defended during inter-state negotiations (Moravcsik, Citation1993; Moravcsik & Schimmelfenning, Citation2019). Especially when the issue is salient for citizens, national ministers are expected to represent domestic public opinion well (Moravcsik, Citation2002).

Empirical analyses find that expectations from liberal intergovernmentalism hold only conditionally, however. Ministers in the Council of the EU represent domestic public opinion if national elections are imminent (Kleine et al., Citation2022; Schneider, Citation2018), or – as predicted by LI – for salient issues (Hagemann et al., Citation2017; Hobolt & Wratil, Citation2020). Others find that national ministers shirk from domestic public opinion even when the issue is salient (Arregui & Creighton, Citation2018), and that they are often constrained by (a) sectoral lobbies and/or the economic context (Bailer et al., Citation2015); and (b) by their party line on an issue (Thomson, Citation2011). Cross-cutting cleavages may further widen the gap between national executives and public opinion (Hix, Citation2018). Moreover, smaller member states were found to be more successful in EU negotiations – since super-majority requirements make them pivotal (Cross, Citation2013; Thomson, Citation2011). States who care more about an issue are also overly influential, and logrolling is common in inter-state bargaining (Moravcsik, Citation2008; Thomson, Citation2011). The indirect election of national ministers to supranational roles is expected to further weaken their links to public opinion (Follesdal & Hix, Citation2006), and their accountability (Raunio, Citation2009). These constraints often impair ministers' capacity to represent their domestic constituency, let alone the European majority (Hix, Citation2018; Thomson, Citation2011).

On the basis of the above, the article derives and tests the below hypothesis:

H1: The weakening of territorial legislative procedures (i.e., codecision) causes (EU) policies to better track the polity-wide (European) opinion mood.

The core focus of the study is, therefore, responsiveness to polity-wide public opinion, given its normative standing especially as it pertains to policies where individuals are the key stakeholders (as employment & social policy). Nonetheless, the study also looks into responsiveness to territorially weighted public opinion, to put the ‘demoicratic’ legitimacy argument to the test (see Online Appendix, Table A4 – Model 3).

Causal mechanisms: codecision and territorial decision-making in the EU

Codecision was first introduced by the Maastricht Treaty. It was expanded and applied to EU employment and social policies in 1999, via the Amsterdam Treaty. It was further extended to additional policy areas – becoming the EU's ordinary legislative procedure – with the Lisbon Treaty (Craig & De Búrca, Citation2020). Before codecision, consultation and cooperation were the principal decision-making procedures of the EU, particularly as it pertains to the employment and social policy domain.

Under the strongest intergovernmental decision-making procedure – i.e., consultation – the European Parliament (EP) has, at most, power of delay: it can offer an opinion on the dossier in question, which the Council can ignore (Craig & De Búrca, Citation2020). Studies demonstrate that the EP indeed has limited influence under this procedure and is consistently neglected by the Council, who decides by consensus (Kardasheva, Citation2009).

Cooperation gives the EP a second reading, as well as the opportunity to propose amendments. It was introduced with the Single European Act (1986). It was still close to consultation as a procedure, since the Council could disregard any EP decision or amendment. Only if the EP amendments were aligned with the Commission's position they were more difficult to reject (Kreppel, Citation2002a; Tsebelis, Citation1995), making the EP a conditional agenda setter at best (Craig & De Búrca, Citation2020, Chapter 4).

Codecision has three reading stages, where the EP and the Council must approve each other's amendments for the legislation to pass. Codecision introduced two seismic changes in the adoption of EU policies: (1) it makes the EP a full veto player (Tsebelis, Citation1995); (2) it encourages the use of qualified majority voting in the Council, weakening the norm of consensus (Craig & De Búrca, Citation2020).

Most scholars agree that the chief effect of codecision has been to transform the EP – the directly elected, ideological chamber – into a powerful co-legislator, although still somewhat less influential than the Council (Burns et al., Citation2013; Costello & Thomson, Citation2013; Kreppel, Citation2018). Studies show that EU policy outputs adopted by codecision are closer to the EP's position (Thomson, Citation2011), that EP-sponsored amendments now have a higher success rate (Burns et al., Citation2013; Kreppel, Citation2002b, Citation2018), and that the EP position is even influencing and politicising bargaining within the Council by making ministers more involved and accountable (Bailer, Citation2004; Häge & Naurin, Citation2013; Hagemann et al., Citation2017). Codecision has pushed the Council to collaborate with the EP and take the EP majority position into account (Costello, Citation2011; Costello & Thomson, Citation2011). Even in trilogues – used to fast-track adoption, and suspected of giving an advantage to the Council – the EP and Council appear to be equally influential (Broniecki, Citation2020).

The mandate of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) is to represent the Union's citizens (TEU, Citation2012, Art 14.2). The EP prioritises individuals rather than nation states: while the election of MEPs is run via the domestic party system, the EP is internally organised by ideology – via the European Party Groups (EPGs) (McElroy & Benoit, Citation2010). Voting cohesion is high within EPGs but not by nationality (Hix et al., Citation2007; Ringe, Citation2010). Furthermore, the EP votes by a simple or absolute majority of members (Craig & De Búrca, Citation2020): it is a truly polity-wide legislature which is expected to be better able to translate public opinion into policy. The EP has been found to represent European public opinion (Sorace, Citation2018) and ideological (rather than territorial) constituencies well (Costello et al., Citation2012; Dalton, Citation2015; Schmitt & Thomassen, Citation1999; Vasilopoulou & Gattermann, Citation2013; Walczak & Van der Brug, Citation2013).

MEPs are directly elected to serve in the EU legislative branch, via proportional electoral formulae. Furthermore, they are not linked to either EU or national executives (Craig & De Búrca, Citation2020), making the EP a separation of powers legislature (Sorace, Citation2021a). These institutional characteristics should give MEPs more leeway to act as sincere representatives of their voters' policy preferences (Golder & Stramski, Citation2010; Hobolt & Klemmensen, Citation2008; Rasmussen et al., Citation2019; Wlezien & Soroka, Citation2012). The EP furthermore scores highly on accountability and transparency (Duina & Lenz, Citation2017). The assumption that EP elections are second-order has been challenged, since the peculiar electoral behaviour patterns in EP elections have been found to be related to EU-specific political contestation (Carrubba & Timpone, Citation2005; Hobolt et al., Citation2009; Kousser, Citation2004; Weber, Citation2011). But even if EP elections are too weak of an accountability mechanism – being run by national party systems and dominated by ‘second-order’ behaviour (Hix & Marsh, Citation2010; Reif & Schmitt, Citation1980) – the electoral link of the Council is even weaker (Follesdal & Hix, Citation2006), since domestic elections are rarely about Europe, while EU-issues actually shape voting behaviour in EP elections (De Vries & Tillman, Citation2011; Hobolt & Spoon, Citation2012; Hobolt et al., Citation2009; Sorace, Citation2021b).

In sum, policies decided by codecision are less likely to be subject to national vetoes in the Council and are more likely to be shaped by the EP, an institution of individual representation. These changes are expected to improve responsiveness to public opinion.

Method: difference-in-differences

In the context of EU employment and social policy, the entry into force of the Amsterdam Treaty meant that dossiers that were assigned the cooperation legal basis before 1999 are, after May 1999, automatically assignedFootnote1 codecision as their legal basis. I leverage this discontinuity in a DiD design. EU policy dossiers are pre-assigned to a legal basis by Treaty, according to their topic. Employment and social policy dossiers decided by cooperation and then codecision broadly deal with: (a) health and safety; (b) regulation of working conditions; (c) information & consultation of workers; (d) vocational training. Dossiers typically assigned to consultation in this policy domain deal with: (a) social security/social protection; (b) employment contracts and termination/dismissals; (c) conditions of employment for third-country nationals; (d) job creation/labour law; (e) equal treatment; (f) pension rights. The topic composition of the cooperation/codecision and of the consultation groups is stable across time. Legal bases are predetermined and although they can sometimes be challenged, this is a very rare occurrence and is usually triggered by domestic in-fighting in a specific member state (Barnard, Citation2012).

To identify the causal effect of the codecision reform on the policy-opinion link, the study applies a difference-in-differences (DiD) design. This quasi-experimental design ensures that the exchangeability assumption of causal inference is met by exploiting time and group-level fixed effects. The treated group outcome is compared to its outcome pre-treatment and to a control group – the counterfactual scenario (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2008). This covers against causal inference threats due to treatment and control groups not being equivalent on various observables (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2008; O'Grady, Citation2020). The formula below summarises the DiD design:

(1)

(1) where

is a dummy variable indicating whether the unit is in the treatment (in this case: legislation decided by cooperation or codecision) or in the control group (in this case: legislation decided by consultation). This automatically protects from inference threats due to group-variant characteristics, such as, for example, legislative dossiers' differential topic salience.

is a dummy variable indicating whether the unit is in the pre- or post-treatment administration period, i.e., before codecision was introduced (prior to 1999-Semester 2, coded as 0) or after (from May 1999 onwards, coded as 1). The pre-post comparison protects from maturation effects, i.e., the impact on the policy-opinion link of changes impacting both groups such as, for example: EU enlargement, changes in the economic context, or changes in the politicisation of the EU.

The DiD estimate is given by the interaction effect representing the difference between the control group's difference in outcomes in periods 1 and 2, and the treatment group's difference in outcomes in periods 1 and 2. Table summarises the DiD design of the study. The number of EU directives in the sample is stable across the two time periods within each group (13 and 10 for the intergovernmental group, 28 and 28 for the supranational group).

Table 1. DiD design – EU employment & social policy.

The analysis only covers employment policies from 1990 until 2008. Prior to 1990 not much legislation on social and employment policy was produced at the EU level (Geyer, Citation2013). Moving beyond 2008 would have introduced inference threats – due to the further expansion of codecision with the Lisbon Treaty (2009) to many more policy topics – which would have differentially impacted the treatment and control groups – as well as due to potential group differential effects of the 2008 financial crisis aftermath (Barbier, Citation2012; De la Porte & Heins, Citation2016; Lammers et al., Citation2018; Zeitlin & Vanhercke, Citation2018).

Measuring the policy-opinion link: comparing crowdsourced policy scores and public opinion data

The outcome of interest here – i.e., the policy-opinion link – requires comparing legislative acts with public opinion policy positions. Measuring the exact match between policies and opinions is intractable due to scale non-equivalence (Wlezien, Citation2017). Typically, the policy-opinion link is measured by regressing public opinion preferences on measures of policies' placements in an ideological dimension. Simply comparing the regression coefficient of public opinion on EU policy for the four treatment groups in this analysis, however, would entail a triple interaction and a difference-in-differences-in-differences design (DDD) which would be seriously under-powered given the sample size (N = 79). I, therefore, opted for standardisation to bring policies and public opinion on the same scale.

The dependent variable is the absolute difference between the z-score of the specific EU directive's position in the pro-worker vs. pro-business dimension, with the z-score of European public opinion preferences in the semester of adoption. Each respective z-score measures whether the EU policy or public opinion was to the right or to the left of its respective mean (calculated across the whole 1990–2008 period). This means that the final measure of responsiveness is metric-free and cannot indicate whether responsiveness goes to the left or to the right. The measure does not capture ideological congruence between EU policies and public opinion: it captures instead whether moves from the mean (the ‘anchor’, or period reference point) in public opinion are reflected in equal moves from the mean (the ‘anchor’, or period reference point) in EU legislation, proxying the concept of policy-opinion ‘mood’ responsiveness (Erikson et al., Citation2002; Wlezien, Citation1995). Higher values, therefore, indicate that EU directives and EU-wide public opinion are out of sync, as they move in different ways from their respective anchors, while a score of zero means that EU policies and public opinion are moving away from their respective means in the exact same direction and with the exact same magnitude.

For robustness, I also use the ‘raw’ crowdsourced ideological scores of EU directives as the dependent variable, and test whether codecision moved EU policies towards the pro-business or the pro-worker direction. A parallel analysis of public opinion trends then reveals whether public opinion moved to the right or to the left after 1999. This alternative analysis is discussed in more detail below.

To place the 79 directives in the pro-worker vs. pro-business dimension, I adopted crowdsourced text analysis.Footnote2 The full list of legislative acts is in the Online Appendix (Table A1). The list is exhaustive of key legislation on the topic between 1999 and 2008.Footnote3 The Directives were assigned ideological scores ranging from −1 (extreme pro-worker) to +1 (extreme pro-business) by online crowds, appropriately trained by a valid and reliable codebook (see Section 2 of the Online Appendix for details). These ‘raw’ scores were then standardised across the 1990–2008 period. The standardised scores (plotted in Figure 3 of the Online Appendix) match experts' assessment of key directives, and of their relation to the EU policy status quo. The expansion of workers' protection at the beginning of the 1990s, and the subsequent move to the ‘flexicurity era’ on the cusp between the 1990s and the 2000s (Barnard & Hervey, Citation2001; Geyer, Citation2013) were clearly captured by the measure adopted here. Directives identified by experts as mixing adaptability concerns with quality of work concerns (e.g., 1997/0081 and 1999/0070) were scored as more centrist than policies recognised by experts as more ambitious than the status quo in terms of equality and worker's protection (e.g., 1994/0033 and 1992/0085) (Barnard & Hervey, Citation2001; Geyer, Citation2013).

European public opinion is captured first via the Eurobarometer (EB) left-right item, and then via Caughey et al. (Citation2019) absolute economic conservatism scores. Because the left-right scale conflates too many dimensions of political competition (Benoit & Laver, Citation2006; Treier & Hillygus, Citation2009), it was necessary to complement the EB analysis with data that captured economic domain-specific policy preferences. The EB data covers all EU member states at granular, 6-months intervals. Unfortunately, Caughey et al. (Citation2019) data are averaged across biennia and do not cover Luxembourg, Malta, Romania and Slovakia. Triangulating findings using both datasets were, therefore, necessary. European public opinion consists in the weighted average of respondents in the relevant semester/biennium. The weights used are the European Union-wide post-stratification weights in the EB. Caughey et al. (Citation2019) already weighted and aggregated economic conservatism scores at the country level. To come up with the EU-wide economic conservatism for each relevant biennium, the data points were re-weighted using the population size of the country for that biennium (taken from the WorldBank). The public opinion scores, like the crowdsourced policy scores, were then standardised across the 1990–2008 period.

Policies and public opinion are compared in the semester (or biennium, in the case of the Caughey et al., Citation2019 dataset) when the EU directive was passed (contemporaneous responsiveness). This works particularly well in the case of the Eurobarometer data, since the directives in the sample are promulgated at the end of each respective semester, i.e., months 6 – for semester 1 – or months 10–11 – for semester 2; while Eurobarometer survey data are typically fielded around the months of March (month 3) and September (month 9), respectively. This is an additional reason why the EB analysis proves particularly valuable, despite the generic left-right ideological score used. Since legislative negotiations might extend for longer periods of time, I have also re-run the analysis by looking at lagged public opinion as well (see Table A4, Model 4 in the Online Appendix). The results hold under this alternative specification.

Results

Model 1 in Tables and report the results from the basic DiD analyses, which show that the application of codecision reduced the discrepancy between EU policy and public opinion moods. The reduction is of roughly 1 standard deviation, meaning that – in a scenario where public opinion is fixed – EU legislation moved towards European citizens' preferences by its standard deviation. When using the raw pro-business/pro-worker scale, this would be a move of roughly 0.3 of a unit in the −1/+1 dimension. Put more simply, codecision dossiers are more likely to track public opinion shifts by moving in the same left-right direction: as European public opinion shifts in one direction from its mean it is more likely, under codecision, that EU policies also shift in the same direction from their mean. These findings hold when using Caughey et al.'s (Citation2019) public opinion measure on economic conservatism.

Table 2. DID models using the eurobarometer data.

Table 3. DID models using the Caughey et al. (Citation2019) data.

Tables and also present robustness models that take into account the potential auto-correlation of the errors (Bertrand et al., Citation2004), via (a) bootstrapped standard errors (Model 2); (b) jack-knife standard errors (Model 3); and (c) semester or biennium fixed effects (Model 4).Footnote4 The findings are broadly robust to such alternative model specifications.

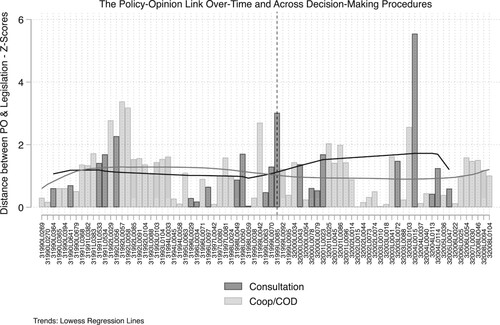

Figure visually describes the result from the DiD analysis, by plotting the policy-opinion (mood) distance over time and by treatment group. The image shows that post-1999 legislation decided by consultation (the intergovernmental procedure) is increasingly unresponsive, and is farthest from public opinion than legislation adopted under codecision. This means that EU legislation in employment policy tended to further deviate from the public mood after 1999. Had codecision not been introduced, we would have therefore seen an overall increase in policy-opinion mood mismatches in this policy area post-1999 (the complicating effect of enlargement on the Council-led aggregation of European public opinion might be a reason for the post-1999 trend towards unresponsiveness). Legislation decided by codecision also appears to better track the public mood than that decided by cooperation (pre-treatment). The graph further highlights that Directive 2004/0015 – from the control group – is an outlying observation. To check whether this outlier is driving the results, I have run additional robustness models that omit Directive 2004/0015 from the DiD analyses (see Table A4, Model 1 in the Online Appendix). The DiD results are weakened when the outlying directive is omitted, but significant reductions in unresponsiveness in the expected direction are still detectable (although narrowly missing the 0.05 statistical significance level, p-value: 0.09).

Figure 1. Absolute policy-opinion difference by treatment group.

Notes: Public opinion measured with Eurobarometer data. Black line: smoothed average of consultation dossiers; grey line: smoothed average of cooperation/codecision dossiers

I have furthermore run an analysis (see Table A5, Model 1 in the Online Appendix), where the dependent variable is simply the ‘raw’, unstandardised crowdsourced score on the pro-business/pro-worker dimension of each EU directive. This was combined with a parallel analysis of public opinion changes over time (Table A5 in the Online Appendix). The findings point at codecision causing EU employment and social policy legislation to move to the pro-worker end of the scale, by 0.46 of a unit in the −1/+1 scale. Public opinion also moved to the left over time, specifically post-1999 and in the economic dimension (p-value : .06, notable with an N = 12 from the Caughey et al. (Citation2019) data). The analysis thus further highlights that codecision did help EU legislation to better track moves in public opinion overall. All in all the signal that codecision improves EU's policies' tracking of public opinion trends appears robust.

A further analysis (Table A4, Model 3 in the Online Appendix) tests whether codecision worsens the representation of territorially-weighted public opinion, as might be argued by defenders of inter-state bargaining. I re-calculated the dependent variable by aggregating public opinion at the national level (using national post-stratification weights in the Eurobarometer, instead of the European ones) and then weighting each member state equally, to come to the territorially weighted average European opinion. Codecision still reduces the mismatch between EU policies' and public opinion's moods, even when public opinion is aggregated by member states. That purely intergovernmental decision-making is necessary for the adequate representation of domestic constituencies is thus not supported by the data.

Inference threats diagnostics

DiD automatically controls for any time-invariant or group invariant confounder, as, for example, maturation effects: both groups would be exposed to any temporal changes in, say, elite awareness of public opinion, or in public opinion awareness of EU matters, or in economic conditions. Time-invariant between-group differences are also automatically controlled for: e.g., features such as topic salience or whether the legislation is of vital national interest. This is because each group's discrepancy with public opinion in the pre-treatment period is compared to its own discrepancy with public opinion in the post-treatment period.

Potential confounders posing a causal inference threat are factors that vary with the time threshold but affect by one group only, like the 1999 EP elections. These elections returned a more centre-right Parliament than the 1989 and 1994 elections (period 1). The 2004 election also returned a centre-right balance of power. Both pre-1999 and post-1999 periods had two EP elections which, however, resulted in similar levels of grand-coalition strength: the EPP and the S&D took 2/3 of the seats between themselves. The only thing that really changes over time and which affects one group only is the ideological balance of power in the EP which shifts to the centre-right in period 2. There is no theoretical reason to suspect that the centre-right would necessarily be less attuned to public opinion than the centre-left, since all parties face similar incentives to pay attention to public opinion. If anything, a centre-right EP may make it more difficult to cater to an increasingly leftist public opinion (see Table A5 in the Online Appendix) and work against finding an effect.

Another factor that varies over time and may affect the two groups differently is the composition of the Council, or the ideology of the Commissioner responsible for the legislative dossier. As each legislative act may be passed at different points in the year, it might have been decided by different Council configurations. Furthermore, it might have been drafted by different DGs, and thus Commissioners with different ideological leanings. Data on Council configurations in each semester from 1990 until 2008 were taken from Rauh (Citation2020), which are based on ParlGov's data (Döring, Citation2013). Data on the political parties of the Commissioner responsible for the relevant legislative proposal were collected via EurLex and the Commission's official website (Former College of Commissioners section). The Commissioner was then placed either on the right (1) or on the left (0) depending on his/her party family. The Council and Commission measures were regressed on the DiD interaction: in the case of the Council, there is no statistically significant correlation between the DiD design and the Council ideology, whereas in the case of the Commission it appears that policies decided by the treatment group post-codecision were proposed by more right-wing Commissioners (at the 0.1 significance level). Given that public opinion moved to the left post-treatment (see Table A5 in the Online Appendix), this confounder runs counter to the hypothesis and therefore makes the DiD test more conservative, so it is unlikely to explain the codecision effect found (Table ).

Table 4. Council and Commission's ideology.

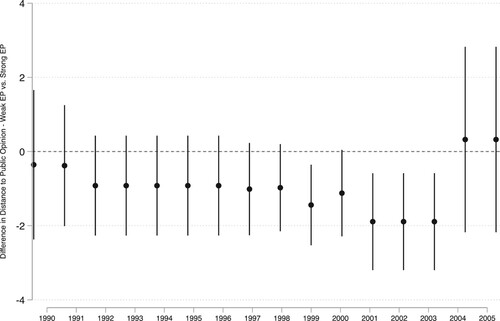

To test more formally that there are no time and group varying confounders, I check the parallel trends assumption. The key identifying assumption of the DiD design is that the trends in the outcome variable would be the same in the consultation and in the cooperation/codecision legal basis groups in the absence of treatment (i.e., before 2 Semester 1999). A formal test of the parallel trends assumption consists in carrying out a series of placebo tests (O'Grady, Citation2020, Chapter 9). This involves running the same model specification but by changing the time dummy so that it captures different time thresholds. If the parallel trends assumption holds, we should not see statistically significant interactions between the treatment groups and the time dummy for time thresholds before the 1999-Semester 2 treatment threshold. Figure shows that the parallel trends assumption was not violated here, since all interaction coefficients before the critical threshold (1999-Semester 2) were not statistically significantly different from zero. This strengthens the confidence that the effect is due to the introduction of codecision and not some other time- and group-variant factor.

Figure 2. Placebo Tests. Differences in policy-opinion distances by treatment group using different time thresholds. The year represents the time threshold imposed on the DiD design. Sequentially, the dummy was modified from the original critical threshold of 1999-Semester 2 to final semesters from all other years.

Conclusion

The European Union (EU) adopted the codecision reform to tackle its democratic deficit. Has the introduction of codecision, which weakened intergovernmentalism in EU policy-making, improved its democratic credentials? This study, by linking an original dataset of ideologically scaled EU employment policies with established datasets on European public opinion (1990–2008), and by exploiting the difference-in-differences design, indicates that codecision caused EU policies to better track movements in citizens' left-right preferences and economic conservatism. There is evidence that codecision, even if only imperfectly addressing the intergovernmental nature of EU decision-making, has improved the EU's democratic legitimacy (measured as the policy-opinion link). These findings lend credence to the expectation from democratic theory that territorially weighted decision rules can hurt the democratic legitimacy of policy outputs.

Much was working against the hypothesis here: most notably, while codecision has indisputably weakened intergovernmental decision-making (Burns et al., Citation2013), it still grants the territorial Council full legislative powers, and the possibility to use unanimity. The treatment is therefore a weak one. Secondly, the low number of observations (79 directives in total), as well as the partisanship of the EP and of Commissioners being at odds with public opinion in the treatment group post-1999 were also factors running against finding an effect. And yet, the causal effect of codecision on the responsiveness of EU policy to public opinion was broadly robust to several model specifications (i.e., adding semester/biennium fixed effects, using bootstrapped/jackknife standard errors, removing outlying observations, adding non-technical regulations in the sample, using ‘raw’ policy scores as the dependent variable, using lagged public opinion, and even using territorially-weighted public opinion).

The causal inference design led, by necessity, to an overly narrow focus on the EU case and on the policy issue of employment/labour law. Future studies should consider extending this research agenda to different contexts and to different policy areas. Nonetheless, employment and social policy is an important case to investigate. Setting standards in working conditions, health and safety and social investment are crucial dimensions of social protection and employment policy, and create tensions between workers and businesses. The EU's work in this area has been ambitious enough that a ‘European Social Model’ is developing (Barnard, Citation2014; Trubek & Mosher, Citation2003). It is therefore crucial that a redistributive policy domain of such salience is responsive to public opinion, and to assess whether supranational institutions can adequately deal with winner-loser policies of this magnitude. Equally, the EU is an important case to evaluate, since many institutions of international governance are moulding their institutional frameworks after it (Rittberger & Schroeder, Citation2016).

The study has important academic implications. Despite being a core measure of the quality of representative democracy, the policy-opinion link is still under-studied (Powell, Citation2004; Wlezien, Citation2017), particularly so in the study of transnational political systems (Wratil, Citation2018; Zürn, Citation2014). Examining the policy-opinion link, furthermore, helped to address significant open questions in EU studies: (a) the democratic deficit argument that the EU is incapable of delivering policies that are responsive to the preferences of Europeans (Follesdal & Hix, Citation2006; Hix, Citation2008; Schmitter, Citation2000); (b) whether codecision has had an impact on EU policies, and specifically, on their democratic legitimacy (Burns et al., Citation2013). This study finds that the EU can indeed be responsive to European public opinion and that codecision has improved the democratic legitimacy of the EU. This article also contributes to the broader field of political representation, in its evaluation of the institutional determinants of responsiveness, and in tackling the debate on territorial representation (Rasmussen et al., Citation2019; Rehfeld, Citation2008).

The study has significant implications for international organisations, and speaks to some important EU reform proposals that are currently animating the Conference on the Future of Europe. The backlash against globalisation is, according to some, partly due to IOs having a democratic deficit (Nye, Citation2001). If IOs are serious about tackling their democratic deficits as they acquire salient, redistributive policy competences, moving away from territorial, inter-state bargaining should be prioritised.

Supplemental and replication materials

Supporting data and materials for this article can be accessed on the Taylor & Francis website, doi: .

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (451.3 KB)Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to the JEPP editor and referees for their precious comments and feedback on the manuscript. I am indebted to Dr Diane Bolet, Dr Philip Dreyer, Ms Lena Hillmeyer, Mr Edoardo Mancini, Mr Nikolaos Theodosiadis and Mr Luìs Cavada Serralheiro for their superb research assistance . I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable feedback on earlier versions of the analysis and manuscript by Dr Tom O'Grady, Prof. Simon Hix, Prof. Christopher J. Anderson, Prof. Fabio Franchino, Dr Florian Foos, Dr Ruth Dassonneville, Prof. Robert Thomson, Prof. Ed Morgan Jones and Dr Ben Seyd. I would like to thank Dr Christian Rauh for his help in sourcing the Council configuration data by semester. Furthermore, I would like to thank all the panel participants at EPSA 2020 and APSA 2020 for their helpful comments on the study. Last but not least, I would also like to acknowledge the organisers of UCD's Connected Politics Lab seminar series Dr Stefan Müller, Dr James Cross, and Dr Martijn Schoonvelde, as well as the organiser of the 2020 ECR Seminar Series, Dr Stuart Turnbull Dugarte, for their helpful feedback, and for providing the opportunity to gather further invaluable comments on the analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Miriam Sorace

Miriam Sorace is Assistant Professor in Quantitative Politics at the University of Kent and Visiting Fellow in European Politics at the London School of Economics & Political Science.

Notes

1 Codecision was applied in the employment and social policy domain only after May 1999, in direct substitution of cooperation (see https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/treaty/epchange_en.htm).

2 To protect from causal inference threats, non-legislative acts as well as regulations are excluded. This avoids confounding due to differential trending of the different acts by treatment group and time period, and due to different procedural and content characteristics. Regulations differ from directives in two crucial respects: (a) they are directly applicable in the Member States' legal systems, thus leaving no implementation discretion; (b) content-wise, they tend to deal with very simple and easy policy changes, to be more ‘regulatory’, thus containing less substantive, ‘direction of travel’ provisions than directives (Craig & De Búrca, Citation2020). This is supported by the crowdsourced text analysis (see Figure 1 in the Online Appendix). The choice to focus on directives is appropriate since the main body of EU employment and social policy is in the form of directives anyhow (Barnard, Citation2012): by way of example, only 30 employment and social policy Regulations were in the 1990–2008 sample. Nevertheless, to address the sample size concern, I have added a robustness test which includes (the less technical) regulations, and the results below hold when increasing the sample size by adding Regulations (see Table A4 in the Online Appendix, Model 2).

3 See https://eur-lex.europa.eu/summary/chapter/employment_and_social_policy.html?root_default=SUM_1_CODED=17 and https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/PERI/2017/600416/IPOL_PERI(2017)600416_EN.pdf – last accessed 18 January 2022.

4 The data are cross-sectional time series, with each item of legislation as a unit of observation. Public opinion is collected and measured every six months (in the EB case) or at biennium intervals (when using Caughey et al.'s dataset), therefore, each legislation is clustered by semester/biennium.

References

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist's companion. Princeton University Press.

- Archibugi, D. (2010). The architecture of cosmopolitan democracy. In G. W. Brown & D. Held (Eds.), The cosmopolitanism reader (pp. 312–334). Polity Press.

- Arregui, J., & M. J. Creighton (2018). Public opinion and the shaping of immigration policy in the European council of ministers. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(6), 1323–1344. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12745

- Bailer, S. (2004). Bargaining success in the European Union. European Union Politics, 5(1), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116504040447

- Bailer, S., Mattila, M., & Schneider, G. (2015). Money makes the EU go round: The objective foundations of conflict in the council of ministers. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(3), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12194

- Barbier, J. (2012). Tracing the fate of EU ‘social policy’: Changes in political discourse from the ‘Lisbon Strategy’ to ‘Europe 2020’. International Labour Review, 151(4), 377–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.2012.151.issue-4

- Barnard, C. (2012). EU employment law. OUP.

- Barnard, C. (2014). EU employment law and the European social model: The past, the present and the future. Current Legal Problems, 67(1), 199–237. https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/cuu015

- Barnard, C., & Hervey, T. (2001). European Union employment and social policy 1999–2000. Yearbook of European Law, 20(1), 297–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/yel/20.1.297

- Benoit, K., Conway, D., Lauderdale, B. E., Laver, M., & Mikhaylov, S. (2016). Crowd-sourced text analysis: Reproducible and agile production of political data. American Political Science Review, 110(2), 278–295. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000058

- Benoit, K., & Laver, M. (2006). Party policy in modern democracies. Taylor & Francis.

- Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355304772839588

- Broniecki, P. (2020). Power and transparency in political negotiations. European Union Politics, 21(1), 109–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116519870870

- Burns, C., Rasmussen, A., & Reh, C. (2013). Legislative codecision and its impact on the political system of the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(7), 941–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.795366

- Carrubba, C. J. (2001). The electoral connection in European Union politics. The Journal of Politics, 63(1), 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00062

- Carrubba, C., & Timpone, R. J. (2005). Explaining vote switching across first-and second-order elections: Evidence from Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 38(3), 260–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414004272693

- Caughey, D., O'Grady, T., & Warshaw, C. (2019). Policy ideology in European mass publics, 1981–2016. American Political Science Review, 113(3), 674–693. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000157

- Cheneval, F., & Schimmelfenning, F. (2013). The case for demoicracy in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 51(2), 334–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.2013.51.issue-2

- Christiano, T. (2018). The rule of the many: Fundamental issues in democratic theory. Routledge.

- Costello, R. (2011). Does bicameralism promote stability? Inter-institutional relations and coalition formation in the European Parliament. West European Politics, 34(1), 122–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.523548

- Costello, R., Thomassen, J., & Rosema, M. (2012). European parliament elections and political representation: Policy congruence between voters and parties. West European Politics, 35(6), 1226–1248. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.713744

- Costello, R., & Thomson, R. (2011). The nexus of bicameralism: Rapporteurs' impact on decision outcomes in the European Union. European Union Politics, 12(3), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116511410087

- Costello, R., & Thomson, R. (2013). The distribution of power among EU institutions: Who wins under codecision and why? Journal of European Public Policy, 20(7), 1025–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.795393

- Craig, P., & De Búrca, G. (2020). EU law: Text, cases, and materials. Oxford University Press.

- Crombez, C., & Hix, S. (2015). Legislative activity and gridlock in the European Union. British Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000380

- Cross, J. P. (2013). Everyone'e a winner (almost): Bargaining success in the Council of Ministers of the European Union. European Union Politics, 14(1), 70–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512462643

- Dahl, R. A. (1989). Democracy and its critics. Yale University Press.

- Dahl, R. A., Shapiro, I., & Cheibub, J. A. (2003). The democracy sourcebook. Mit Press.

- Dalton, R. J. (2015). Party representation across multiple issue dimensions. Party Politics, 23(6), 609–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815614515

- De la Porte, C., & Heins, E. (2016). A new era of European integration? Governance of labour market and social policy since the sovereign debt crisis. In E. Heins & C. de la Porte (Eds.), The sovereign debt crisis, the EU and welfare state reform (pp. 15–41). Springer.

- De Vries, C. E., & Tillman, E. R. (2011). European Union issue voting in East and West Europe: The role of political context. Comparative European Politics, 9(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2009.7

- Döring, H. (2013). The collective action of data collection: A data infrastructure on parties, elections and cabinets. European Union Politics, 14(1), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512461189

- Duina, F., & Lenz, T. (2017). Democratic legitimacy in regional economic organizations: The European Union in comparative perspective. Economy and Society, 46(3–4), 398–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2017.1377946

- Erikson, R. S., MacKuen, M. B., & Stimson, J. A. (2002). The macro polity. Cambridge University Press.

- Filippov, M., Ordeshook, P. C., & Shvetsova, O. (2004). Designing federalism: A theory of self-sustainable federal institutions. Cambridge University Press.

- Follesdal, A., & Hix, S. (2006). Why there is a democratic deficit in the EU: A response to Majone and Moravcsik. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(3), 533–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.2006.44.issue-3

- Geyer, R. R. (2013). Exploring European social policy. John Wiley & Sons.

- Golder, M., & Stramski, J. (2010). Ideological congruence and electoral institutions. American Journal of Political Science, 54(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.2010.54.issue-1

- Goodin, R. E. (2007). Enfranchising all affected interests, and its alternatives. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 35(1), 40–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/papa.2007.35.issue-1

- Häge, F. M., & Naurin, D. (2013). The effect of codecision on Council decision-making: Informalization, politicization and power. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(7), 953–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.795372

- Hagemann, S., Hobolt, S. B., & Wratil, C. (2017). Government responsiveness in the European Union: Evidence from council voting. Comparative Political Studies, 50(6), 850–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015621077

- Held, D. (2006). Models of democracy. Stanford University Press.

- Hix, S. (2008). What's wrong with the EU and how to fix it. Polity Press.

- Hix, S. (2018). When optimism fails: Liberal intergovernmentalism and citizen representation. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(7), 1595–1613. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12785

- Hix, S., & Høyland, B. (2013). Empowerment of the European Parliament. Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1146/polisci.2013.16.issue-1

- Hix, S., & Marsh, M. (2010). Second-order effects plus pan-European political swings: An analysis of European parliament elections across time. Electoral Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2010.09.017

- Hix, S., Noury, A. G., & Roland, G. (2007). Democratic politics in the European parliament. Cambridge University Press.

- Hobolt, S. B., & Klemmensen, R. (2008). Government responsiveness and political competition in comparative perspective. Comparative Political Studies, 41(3), 309–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006297169

- Hobolt, S. B., & Spoon, J.-J. (2012). Motivating the European Voter: Parties, issues and campaigns in European Parliament elections. European Journal of Political Research, 51(6), 701–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejpr.2012.51.issue-6

- Hobolt, S. B., Spoon, J.-J., & Tilley, J. (2009). A vote against Europe? Explaining defection at the 1999 and 2004 European parliament elections. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000422

- Hobolt, S. B., & Wratil, C. (2020). Contestation and responsiveness in EU Council deliberations. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 362–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1712454

- Kardasheva, R. (2009). The power to delay: The European Parliament's influence in the consultation procedure. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 47(2), 385–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2009.00809.x

- Kleine, M., Arregui, J., & Thomson, R. (2022). The impact of national democratic representation on decision-making in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(1), 1–11.

- Kousser, T. (2004). Retrospective voting and strategic behavior in European Parliament elections. Electoral Studies, 23(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(02)00030-6

- Kreppel, A. (2002a). Moving beyond procedure: An empirical analysis of European Parliament legislative influence. Comparative Political Studies, 35(7), 784–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414002035007002

- Kreppel, A. (2002b). The European Parliament and supranational party system. A study in institutional development. Cambridge University Press.

- Kreppel, A. (2018). Bicameralism and the balance of power in EU legislative politics. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 24(1), 11–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2018.1444623

- Lammers, I., van Gerven-Haanpää, M. M. L., & Treib, O. (2018). Efficiency or compensation? The global economic crisis and the development of the European Union's social policy. Global Social Policy, 18(3), 304–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018118790957

- Lenz, T., & Marks, G. (2016). Regional institutional design. In T. A. Börzel and T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism (pp. 512–538).

- May, J. D. (1978). Defining democracy: A bid for coherence and consensus. Political Studies, 26(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1978.tb01516.x

- McElroy, G., & Benoit, K. (2010). Party policy and group affiliation in the European Parliament. British Journal of Political Science, 40(2), 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123409990469

- Mill, J. S. (1869). On liberty. Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

- Moravcsik, A. (1993). Preferences and power in the European Community: A liberal intergovernmentalist approach. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 31(4), 473–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.1993.tb00477.x

- Moravcsik, A. (2002). Reassessing legitimacy in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(4), 603–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00390

- Moravcsik, A. (2008). The European constitutional settlement. World Economy, 31(1), 158–183.

- Moravcsik, A., & Schimmelfenning, F. (2019). Liberal intergovernmentalism. In A. Weiner, T. Börzel, & T. Risse (Eds.), European integration theory (pp. 64–87). Oxford University Press.

- Nye Jr., J. S. (2001). Globalization's democratic defecit: How to make international institutions more accountable. Foreign Affairs, 80(4), 2–6. https://doi.org/10.2307/20050221

- O'Grady, T. (2020). Causal inference for undergraduates. https://github.com/tomogradyucl/Causal-Inference-for-Beginning-Undergraduates

- Powell, G. B. (2004). Political representation in comparative politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 7(1), 273–296. https://doi.org/10.1146/polisci.2004.7.issue-1

- Rae, D., & Taylor, M. (1971). Decision rules and policy outcomes. British Journal of Political Science, 1(1), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400008954

- Rasmussen, A., Reher, S., & Toshkov, D. (2019). The opinion–policy nexus in Europe and the role of political institutions. European Journal of Political Research, 58(2), 412–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejpr.2019.58.issue-2

- Rauh, C. (2020). Data & resources. https://sites.google.com/site/christianrauh/data-and-resources

- Raunio, T. (2009). National Parliaments and European Integration: What we know and agenda for future research. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 15(4), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330903302430

- Rehfeld, A. (2005). The concept of constituency: Political representation, democratic legitimacy, and institutional design. Cambridge University Press.

- Rehfeld, A. (2008). Extremism in the defense of moderation: A response to my critics. Polity, 40(2), 254–271. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.polity.2300097

- Reif, K., & Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second-order national elections: A conceptual framework for the analysis of European elections results. European Journal of Political Research, 8(1), 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejpr.1980.8.issue-1

- Ringe, N. (2010). Who decides, and how? Preferences, uncertainty, and policy choice in the European Parliament. Oxford University Press.

- Rittberger, B. (2012). Institutionalizing representative democracy in the European Union: The case of the European Parliament. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 50(S1), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.2012.50.issue-s1

- Rittberger, B., & Schroeder, P. (2016). The legitimacy of regional institutions. In T. A. Börzel & Thomas Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism (pp. 579–599).

- Russell, M. (2001). The territorial role of second chambers. Journal of Legislative Studies, 7(1), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/714003852

- Schmitt, H., & Thomassen, J. J. A. (1999). Political representation and legitimacy in the European Union. Oxford University Press.

- Schmitter, P. C. (2000). How to democratize the EU and why bother. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Schneider, C. J. (2018). The responsive union: National elections and European governance. Cambridge University Press.

- Shapiro, I. (1999). Democratic justice. Yale University Press.

- Sorace, M. (2018). The European Union democratic deficit: Substantive representation in the European Parliament at the input stage. European Union Politics, 19(1), 0–0. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517741562

- Sorace, M. (2021a). Debating in a legislature with competing incentives. In H. Bäck, M. Debus, & J. M. Fernandes (Eds.), The politics of legislative debates (pp. 304–328). Oxford University Press.

- Sorace, M. (2021b). Productivity-based retrospective voting: Legislative productivity and voting in the 2019 European Parliament elections. Politics, 41(4), 504–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395721991403Forthcomin.

- TEU. (2012). Consolidated version of the treaty on European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:2bf140bf-a3f8-4ab2-b506-fd71826e6da6.0023.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

- Thomson, R. (2011). Resolving controversy in the European Union: Inputs, processes and outputs in legislative decision-making before and after enlargement. Cambridge University Press.

- Toshkov, D. (2011). Public opinion and policy output in the European Union: A lost relationship. European Union Politics, 12(2), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116510395043

- Treier, S., & Hillygus, D. S. (2009). The nature of political ideology in the contemporary electorate. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(4), 679–703. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfp067

- Trubek, D. M., & Mosher, J. S. (2003). New governance, employment policy and the European social model. In J. Zeitlin, & D. M. Trubek (Eds.), Governing work and welfare in a new economy: European and American experiments (pp. 33–58). Oxford University Press.

- Tsebelis, G. (1995). Decision making in political systems: Veto players in presidentialism, parliamentarism, multicameralism and multipartyism. British Journal of Political Science, 25(3), 289–325. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400007225

- Vasilopoulou, S., & Gattermann, K. (2013). Matching policy preferences: The linkage between voters and MEPs. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(4), 606–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.718892

- Walczak, A., & Van der Brug, W. (2013). Representation in the European Parliament: Factors affecting the attitude congruence of voters and candidates in the EP elections. European Union Politics, 14(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512456089

- Weber, T. (2011). Exit, voice, and cyclicality: A micrologic of midterm effects in European Parliament elections. American Journal of Political Science, 55(4), 907–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.2011.55.issue-4

- Wlezien, C. (1995). The public as thermostat: Dynamic preferences for spending. American Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 981–1000. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111666

- Wlezien, C. (2017). Public opinion and policy representation: On conceptualization, measurement, and interpretation. Policy Studies Journal, 45(4), 561–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.v45.4

- Wlezien, C., & Soroka, S. N. (2012). Political institutions and the opinion–policy link. West European Politics, 35(6), 1407–1432. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.713752

- Wratil, C. (2018). Evidence from the European Union. American Journal of Political Science Online Fir. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12403.

- Zeitlin, J., & Vanhercke, B. (2018). Socializing the European Semester: EU social and economic policy co-ordination in crisis and beyond. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363269

- Zürn, M. (2014). The politicization of world politics and its effects: Eight propositions. European Political Science Review, 6(1), 47–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773912000276