ABSTRACT

The emergence of trans-governmental policy regimes in Europe has fundamentally changed the role of National Regulatory Agencies (NRAs). Here we move away from the idea that there is a meaningful divide between the domestic and the European levels of governance and suggest that a different logic has emerged in recent decades, combining multiple chains of delegation and innovative coordination schemes. NRAs have come to occupy a ‘broker’ or intermediary position between domestic and European polities, that is no longer adequately described by the prevailing, mainly dyadic models of bureaucratic autonomy conceived just for national states. In this paper, we build the concept of entangled agencies to make sense of the linkages between NRAs and European Agencies (EAs) and provide some preliminary empirical evidence to show how they effectively articulate various levels of government, presenting empirical findings on the connections that ties NRAs representatives with EAs management boards.

Introduction

The establishment of National Regulatory Agencies (NRAs) at the domestic level by national governments since the 1990s, and the creation of European Agencies (EAs) during the 2000s and 2010s have precipitated changes in the mode of governance of different policy regimes within the EU, often in ways not expected by the treaties. In parallel to the establishment of the Single European Market, NRAs expanded fast over European countries (Gilardi, Citation2002), and soon articulated transnational networks to collaborate among them, but also to have a single voice in EU institutions (Levi-Faur, Citation2011). Later, the launch of EAs opened new opportunities for NRAs to be involved in European-level policy making, but also transformed their role in the domestic environment. With their increasing involvement in EU regulatory policymaking, NRAs have evolved into multi-level actors, gaining new roles as network brokers in a variety of EU and domestic governance constellations (Bach & Newman, Citation2014; Bach et al., Citation2016; Eberlein & Newman, Citation2008; Jordana, Citation2017; Mastenbroek & Martinsen, Citation2018; Newman, Citation2010; Sabel & Zeitlin, Citation2008). What is more, due to the ‘experimentalist’ nature of European and international governance, many policy configurations can be articulated across different levels, and there is not a common model that can account for all cases (Martinsen et al., Citation2021).

In this study, we aim to highlight the special but somehow overlooked role NRAs have come to play in European governance. The focus of students of European governance has rested on the problems of delegation of authority to EU agencies, European Regulatory Networks or to the European Commission (Blauberger & Rittberger, Citation2015; Coen & Thatcher, Citation2008; Dehousse, Citation2008; Eberlein & Newman, Citation2008; Kelemen & Tarrant, Citation2011). In these studies, NRAs are depicted as the building blocks of the regulatory networks rather than as multi-level actors on their own. However, NRAs have evolved and reached a stage where they are able to participate simultaneously at national and European governance levels, without appealing to the traditional treaty-based delegation to supranational organizations. With autonomy from national political principals but strongly embedded in national policy regimes, NRAs have emerged as ideal actors to play a relevant role in European regulatory policy processes, playing different channels than ministerial structures from national state apparatuses. Their delegated powers allow them to directly cooperate with EAs and other supranational institutions, notably the Commission, and regulatory authorities from other member states while maintaining their national angle. In this sense, they have become the ‘domestic drivers of trans-governmental regulatory cooperation’ (Bach & Newman, Citation2014).

In this paper, we first critically evaluate the perspectives on the relationships between regulatory authorities and actors in their environment focusing on a single level (Lodge & Koop, Citation2014; Maggetti & Papadopoulos, Citation2018). Then, we develop further the concept of entangled agency, which is a key capacity of NRAs to be connected to different levels of governance contributing to establish a composite regulatory regime. In the third and final step, we illustrate our argument by presenting empirical findings on one possible entangle mechanism, i.e., the participation of NRAs representatives in management boards of EU agencies.Footnote1 We show how the existence of such involvement allows NRAs to be entangled into EU governance in many policy domains, but also indicate that this is a special configuration related to regulatory governance, not necessarily a general mode of European governance, as delegation mechanisms do not play such relevant role in all cases. Our aim is ultimately to move away from the idea that there is a meaningful divide between the domestic and the European or international levels of governance. We hope to provide a framework for the analysis of multi-level regulatory governance based on the interplay between the concept of entangled agency and multiple delegation structures. Adopting such a view opens a new array of thinking about key issues in regulatory governance and allows us to place multi-level issues at the very center of the analysis.

NRAs in EU governance

Even though NRAs are the building blocks of vastly studied European administrative networks, attention to the evolving role of NRAs themselves in multilevel governance goes somewhat unnoticed. In the literatures on European governance, NRAs are either studied for what they collectively have come to constitute, i.e., transboundary networks (Bach et al., Citation2016; Eberlein & Grande, Citation2005; Mastenbroek & Martinsen, Citation2018), or how NRAs are affected at the domestic level because of the existence of such networks (Bach et al., Citation2015; Danielsen & Yesilkagit, Citation2014). From the few studies that have given systematic attention to NRAs as individual entities in the context of multilevel governance we know that NRAs can take up multiple roles and identities, ‘double hats’, depending on which of the stages in the EU policy process prevail (Barbieri, Citation2006; Egeberg, Citation2006; Egeberg & Trondal, Citation2009; Martens, Citation2006). These studies make clear that NRAs occupy a somewhat different place in the European administrative space alongside the networks, EU agencies and the European Commission (Blauberger & Rittberger, Citation2015; Kelemen & Tarrant, Citation2011).

Apart from being the building blocks of networks, NRAs have come to tie the loose ends between the supranational and national levels in EU multilevel governance: they articulate demands, ideas and proposals in both directions, also having the necessary policy embeddedness to avoid playing a simple role as messengers. This emerging European mode of regulatory governance results from two basic delegation processes by member states, what has been referred to as a dual delegation (Eberlein & Newman, Citation2008). First, horizontal delegation towards the NRAs in the domestic domain, and second, vertical delegation towards functionally specialized institutions in the European domain, as the Commission and the EAs. In addition, there is some delegation from EU core institutions to EAs, more de facto than de jure, allowing them an extended use of EU soft law (Saurugger & Terpan, Citation2021). Over the years, this complex structure of delegation has produced a new mode of regulatory governance in Europe that articulates policy spaces where national states core actors do not keep a prevalent role anymore. As a result, in a significant number of policy areas, NRAs, European Commission directorates and EU agencies, configure a system of delegated entities, that we characterize as entangled agencies, and together have formed composite regulatory regimes enjoying relevant levels of policy autonomy – although overlooked and shaped by legislatives and executives, both at domestic and European levels.

The emergence of European regulatory regimes has transformed the relationship between NRAs and their national political principals in two manners. On the one side, NRAs have obtained additional support, as the Commission invests NRAs with a strong information position vis-à-vis their parent ministries in their home countries, to support their involvement in such composite regulatory regimes (Egeberg & Trondal, Citation2009). On the other side, their involvement in the policymaking phase at the EU level entrusts NRAs with co-lawmaking powers that is equivalent to the position of national ministries, albeit at a different governance level (Maggetti & Papadopoulos, Citation2018). Such simultaneous access to European and national policymakers deems them policy intermediaries across different levels of governance in Europe and therefore players attractive to the larger regulated industries, which are often themselves multi-level actors (Abbott et al., Citation2017; Jordana, Citation2017; Maggetti & Papadopoulos, Citation2018). In this context, it is not a surprise that many studies bear witness to the growing de facto autonomy of NRAs vis-à-vis the national executive, after their formal establishment in the previous years (Bach et al., Citation2015; Bianculli et al., Citation2015; Danielsen & Yesilkagit, Citation2014; Yesilkagit, Citation2011).

Nevertheless, public administration scholarship has predominantly employed the frame of dyadic models of political control and bureaucratic autonomy to study interactions between NRAs and the actors in their multi-level environment. As we will argue in more detail below, the case we confront is more complex as we face multi-level interactions as well. In European regulatory regimes, we have different structures of delegation operating together, but also a system of policy articulation to keep the regulatory governance integrated, by means of national agencies that are entangled with EU governance in various ways. This multi-level system that integrates delegation and coordination mechanisms simultaneously requires the development of interpretative models and better adjusted theoretical frameworks. Here, we aim to contribute to this need and provide a framework to study the entangled roles and positions of NRAs in European regulatory governance. This is just a first step to the purpose of elaborating an integrated view of how European regulatory regimes operate.

Entangled agencies and dual delegation

The relationships between NRAs and other multilevel actors are somewhat more complex than depicted in the mainstream delegation accounts of EU governance. The boundaries of NRAs are more elusive, and they are not the unitary actors that most studies sketch. NRAs, as we will show in this paper, maintain a more complex relationship, one that we have labeled as entangled, with other actors, most notably EU agencies. With the term ‘entangled’ we refer to an NRA's capacity to participate simultaneously at national and European governance levels, without appealing to the traditional treaty-based delegation to supranational organizations.Footnote2 NRAs, we maintain, are entangled in such ways that the classic principal–agent-based relationships between NRAs and other actors no longer adequately reflect governance constellations in the European administrative space. It may well have been the case that the designers of EU governance did have clear views at the time of delegation regarding the role and authority transferred to EU actors and also of how the actors should be demarcated from each other. In practice, the evolvement of more complex set of relationships in reality, that is the growing vertical entanglement of NRAs, has become a challenge to the principal–agent models that have guided the study of dual delegation in the multilevel context.

In classic applications of Principal-Agency (P-A) theories the discretion or autonomy that an agency enjoys is perceived as a function of the design and governance of the agency, all controlled by the principal (Bawn, Citation1995; McCubbins et al., Citation1987; Weingast, Citation1984; Weingast & Moran, Citation1983). Although P-A models have become much more sophisticated, to include for example, unforeseen outcomes of principal decision-making on agency design, the multi-directional nature of regulatory authorities’ relationships, both at the national and European levels, has not been easily captured by these studies. The failure can be attributed to the fact that ‘PA models fail’ to acknowledge that ‘[A]fter delegation, the “agent” may become an active “player” in domestic politics’ (Maggetti & Papadopoulos, Citation2018, p. 179). It refers to what Yesilkagit (Citation2004) has referred to as ‘habituation’. In informal institution-building processes of habituation, the political principal and the agent develop a post-delegation relationship that cannot be predicted from the act of formal delegation itself.

Departing from these criticisms, we suggest that the process of NRAs’ ‘habituation’ has evolved also towards the European level, expanding their political-administrative space, in a way that it was not expected by their principals when these agencies were created. This has been characterized also as a ‘double-hatted’ dynamic, where NRAs are connected to their domestic administrative systems as well as to the emerging EU administration (Egeberg & Trondal, Citation2009). The limits of the principal–agent logic in the setting of these trans-governmental regulatory regimes are captured by the notion of dual delegation (Newman, Citation2010). Dual delegation denotes the fact that in increasingly globalized environments, national states may delegate policy mandates to domestic agencies as well as to international organizations (IOs), who then in turn establish working relationships with each other on the basis of the delegated powers they have received from states (Roger Citation2020). This applies also to the EU, who can be considered an international organization, and NRAs as domestic agencies enjoying delegation. So, this represents a case of multiple delegation (to the EU and NRAs), by multiple principals (member states), that even create EAs where delegated entities (EU institutions) and principals (states) meet again.

National states’ dual delegation, when it occurs, facilitates a mode of governance that triggers multilevel regulatory regimes, where interests, preferences and policy proposals circulate across channels and where political involvement remains more distant than in conventional bureaucratic autonomy models. Such a trans-governmental perspective transcends the classic neo-realist perspective on delegation whereby national states delegate authority to international organizations and then police patrol the IO through national state representatives positioned within committees with oversight powers. In this sense, the very fact of establishing EAs as an expansion of the EU institutional framework in recent decades, expanding the delegation chain and connecting the dots with NRAs – that already enjoyed delegation – can be seen as a culmination of the composite regulatory regimes at the European level.

NRAs, then, have grown out of their comfort zones. The autonomy of NRAs, becoming active players within their national environments, allows the emergence of regulatory spaces to directly interact with the EU institutions (particularly DGs in the Commission and EAs). This does not mean that NRAs do not remain sensible to their domestic environment. As a matter of fact, they remain within the orbits of the interests of political and bureaucratic actors in the country where often their parent ministries play the most relevant role. Obviously, these configurations can vary largely depending on the nature of each sector and the character and strength of the administrative state in each member state (Barbieri, Citation2006; Martens, Citation2006). Their autonomy allows NRA preferences to align with those of EU institutions, seeking additive capacities to implement European policies, while serving different central governmental departments that are directly under the political control of the political executive (Bach & Newman, Citation2014; Eberlein & Newman, Citation2008). In neither case are they any longer the simple intermediaries or transmission chains in between the EU and Member States. Their domestic embeddedness allows them to behave as autonomous institutions regarding preference formation in many cases.

The neglected side of the story concerns the ties between NRAs and EAs, that are more complex than depicted. They include networking activities, multiple bilateral exchanges and participation in EAs bodies, among other mechanisms. Our expectation is that these ties are important because they provide stable connections and policy involvement between the two levels, configuring NRAs as entangled agencies to the EU governance. The various roles that NRAs play because of this condition define a different nature of the regulatory game than the one dominating in conventional national arenas. Here we argue that participation of NRAs at the European level is reinforced by their involvement in the management board of European agencies, that facilitates the NRAs’ entanglement with EAs.

Emerging research on boards of EAs focusing on career paths of board members shows that the mixed representation of political, stakeholder and business representatives is a function of the preferences and interests of the appointing bodies to exert control over the decisions of the agencies (Arras & Braun, Citation2018; Pérez-Durán, Citation2019). Another strand of literature on EAs’ management boards has focused on the question whether they are intergovernmental mechanisms and operate as an extension of the member states realist politics within the management of EU policy, or whether they are representative of supranational tendencies according to which member state representatives within EU agencies boards attune to more integration and are autonomous from the member states (Buess, Citation2015). In our perspective, domestic embeddedness of NRAs and their entanglement to EAs by mechanisms like the participation of NRAs representatives in EAs boards introduces a different approach, that allows to identify how composite regulatory regimes in Europe work. Actually, these regimes can vary according to the intensity of preference embeddedness to domestic interests by NRAs, as well as the strength of the ties that entangle them to EAs.

Data and method

The empirical analysis provided in this paper aims to demonstrate the entangled nature of NRAs in European governance. The central mechanism through which NRA entanglement is facilitated is the participation of NRA board and staff members in the boards of EU agencies. Although our main focus rests with the entangled relationships of NRA, the data allow us to show how much more NRAs are involved in multilevel governance than other EU actors. For this purpose, we examine the profiles of the management board members of EAs, aiming to examine how strong the interlinkages are between NRAs and EAs – and in this way, using it as a proxy to confirm our expectations about the relevance of NRAs entanglement in EU regulatory governance. We expect that EAs with active regulatory tasks will experience strong NRAs entanglement, meaning that national agencies will be really involved as key actors in the composite regulatory regime when this is relevant for multilevel governance.

The data for the analysis in this paper are drawn from a biographical database of management board members of 30 EU agencies (Jordana et al., Citation2020). The full list of EU agencies is provided in the Appendix (see ). The dataset identifies 1073 unique individuals who were members of EU agencies management boards in 2017. Data were collected at the level of individual board member as well as at the level of the EU agencies themselves. The data collected for individual board members include their personal (gender, nationality), educational, professional, career backgrounds and the position they occupied at the time of our survey. The most important data for our analysis, i.e., concerning the participation of NRAs representatives, concerns the data on their career backgrounds. Under career background are coded, first, the positions that individual management board members hold in addition to their appointment within the board of the EU agency; secondly, there is also data on the positions that management board members have held before the position they were holding at the time of their presence in an EU agency management board. It is important to note here, again, that appointments at an EU agency management board are the individuals’ additional positions to their primary job as board members or staff members of NRAs.

At the level of EU agencies, we collected data regarding the function and powers of EU agencies. As regards function, we coded a dummy variable for distinguishing between EU agencies with a regulatory and a non-regulatory function. To classify EU agencies according to their function, we used the classification of Christensen and Nielsen (Citation2010) and cross-checked those with the classification employed by Busuioc (Citation2013). Next to their functions, agencies are delegated a variety of tasks. The tasks range from the collection, provision and dissemination of information, network coordination, policy advice and authoritative decision-making. Following Christensen and Nielsen, we conceive of these tasks as increasing degrees of authority, with EU agencies having decision-making powers as having the highest degree of authority.Footnote3 Finally, also coded is the identity of the appointing authorities. The EU agencies’ founding legal documents specify the identity of the entities that have the authority to appoint members to the management boards. We analyzed these data using descriptive and correlational analysis. In a first step, we present the data on the career and positional backgrounds of individual management board members. Then, in a second stage, we control these data for the functions and tasks of the EU agencies. In the Appendix, we offer an overview of our data per EU agency (see ).

Findings

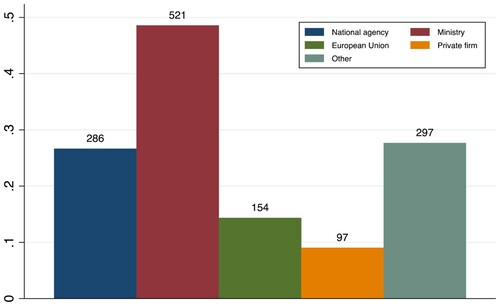

As a first step, we offer descriptive data concerning the career backgrounds of EU management board members. shows the positions that individual board members held before their appointment to the board of an EU agency.Footnote4 The graph shows that in EU management boards, 286 individuals were appointed with accumulated experience with the EU at a national or regional agency in one of the member states. Another 521 individuals did so with previous positions within ministries. If we control for persons who held multiple positions, we find that 213 individuals did hold a position in an agency but not in a ministry; 448 in a ministry but not in an agency; and 73 persons in both.Footnote5 Important to note is that despite overlaps between career paths, the various paths seem to exclude each other. offers the correlation coefficients between the four designated career paths. Individuals who held positions within national agencies are less likely to have held positions within ministries and, to some lesser extent, at EU institutions. We see an interesting positive correlation between agency careers and careers in private firms. Although we do not have longitudinal data that exactly stipulate when agency and private positions have been held, the data hints at revolving doors between national agencies and private firms. Interesting is also the observation that those who held positions within national ministries less likely held positions within an EU institution or a private firm. The relationship between positions held in an EU institution and private firms, finally, is almost non-existent.

Table 1. Correlation coefficients board member backgrounds (N = 1073).

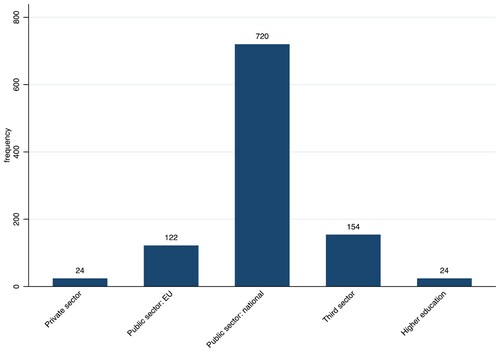

presents the sectors in which current EU agencies’ management board members have their primary position. Two-thirds of the individuals held a position in the national public sectors at the same time as they were members of EU agency boards. In , we present the current status of the board members. Of the current board members, 838 individuals (78 per cent of the total number of individuals in the dataset) can be classified as civil servants. Of these 838 persons, 85 per cent work as civil servants in the national public sector at the time of data collection. This group comprises a variety of civil servants at ministries, (semi-)independent agencies as well as at other types of non-departmental public sector bodies. Focusing on agency board members, the dataset contains 34 per cent (n = 362) individuals who worked at a national or regional agency at the time of data collection. As indicates, almost all of them (333) were currently working in a NRAs at the same time they were participating in the EU agencies’ management board. Only few of them, having worked before in a NRA, were at that moment working in EU bodies (21) or other positions (7).

Table 2. Current working status controlled by current sector (percentages in brackets).

Examining more in detail those 362 individuals working in NRAs while sitting in EU agencies management boards, we observe that only 10 individuals are board members of NRAs, while a large majority (293) are directors or managers of NRAs, and the rest are staff members with a technical profile (36) or other categories. Before turning to the distribution of national agency administrators over the various types of EU agencies, we present a first indication for the dual role national representatives play in European administrative networks. reports the identity of the bodies with the powers to appoint the members of European agencies’ management boards and the type of representatives these bodies appoint to EU agencies management boards. From this table, it follows that the majority of the appointments to EU agency boards are made by the member states. The overwhelming majority, 720 board members (69 per cent), are employed by their national public sectors, followed by individuals working in the third sector (154, 14 per cent) and the institutions of the EU (122, 11 per cent).

Table 3. Background of EU agencies board members by appointing authorities in 2015.

The boards of EU agencies are hence predominantly occupied by individuals working within national public sectors. The member states have been responsible for about two-thirds of all appointments to EU agencies’ boards. Moreover, 91 per cent of the board members appointed by member states worked within the national public sectors of the member states. The EU Council follows the member states by appointing individuals with a background in the national public sectors, although the number of appointments by the Council accounts for less than one-tenth of all appointments of board members with backgrounds in national public sectors. Secondly, the majority of board members who already were holding positions at the EU level were appointed by the Commission and other European agencies. Finally, and as expected, stakeholders have been responsible for the bulk of board members from the third sector. All in all, the table confirms the existence of interlocking directorates of national civil servants working either in national ministries or national agencies.

Now we turn to the findings of how many and which interlocking directorates exist between NRAs and EAs. More precisely, we are interested in the question of what type of EAs NRA representatives are appointed. Are there, for example, differences between ministries and agencies as to whether either one is more or less represented in EU agencies with regulatory, respectively, non-regulatory functions? And, are there differences between the presence of agency or ministerial staff in EU agencies more or less powers? This question is of importance to our study as we are interested to understand the quality of the entanglement of NRA representatives. As compared to national ministries and other types of organizations, are NRAs more represented in the more powerful regulatory regimes in the European administrative space? As is common in the EU agencies literature, we distinguish between EU agencies with a regulatory and non-regulatory function. Although EU agencies lack decision-making or sanctioning powers, except for example ESMA and EBA, the agencies with regulatory functions hold more substantial positions within the European administrative space as a growing number of them obtain relevant responsibilities to shape policies, norms, or standards, on the basis of soft law instruments.

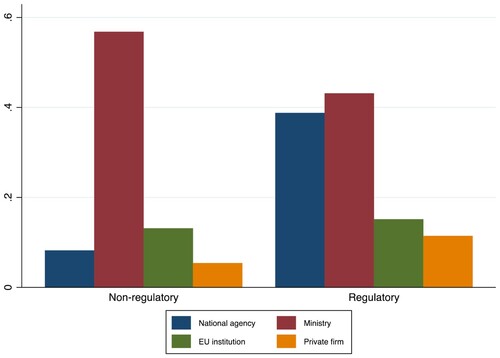

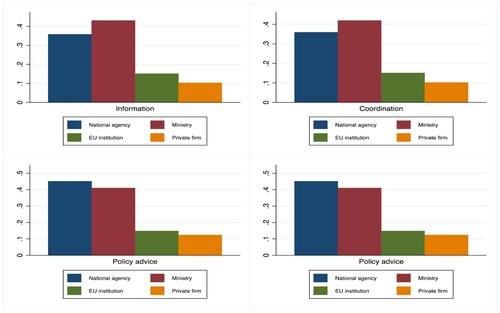

In , we compare the mean values (shares) of the previously held positions of individual board members in regulatory and non-regulatory EU agencies. We find persons with current or previously held positions in NRAs are overwhelmingly more represented in management boards than persons with priors at national ministries. Overall, the graph shows that national agency and ministry representatives outweigh the presence of private firm and EU representatives in EU agency boards. Some EU agencies, regulatory as well as non-regulatory in nature, enjoy more powers than others. The powers EU agencies possess may vary from the collection and provision of information, the coordination of transboundary supervisory networks, the delivery of policy advice to the European Commission (or other EU institutions), the development of regulations for some technical areas, and even some agencies have been delegated powers to make authoritative decisions in individual cases. only employs data for EU agencies with regulatory functions. We find that the more authority an EU agency possesses, the more of its board members are or have been (former) national agency representatives. Whereas individuals with appointments in a ministry outnumber individuals with agency backgrounds in EU agencies with mainly information and coordination tasks, in EU agencies with additional policy advisory and decision-making powers, it is individuals with a position in a national agency that outnumber those with a ministerial background.

Graph 4. Board members with various previous positions across regulatory EU agencies with various tasks.

The findings in the graph are supported by correlation analysis. presents the correlation coefficients between positions held by management board members and the powers that EU agencies possess. The first finding is that EU agency board members with positions (held) in NRAs are more likely to be found in EU agencies with regulatory functions than board members with positions held within ministries. The second finding is that management board members with positions within national agencies are more likely to be appointed at EU agencies with policy advisory and decision-making powers than individual board members that have (held) positions in any of the other three domains. The relationship between board members with positions in national agencies and EU agencies with policy advisory and decision-making powers is positive and strongly significant. Representatives of national agencies are hence more involved in EU agencies with hard powers than in EU agencies with soft powers. When the analysis is repeated for regulatory EU agencies only, the results remain the same for ministry, EU and private firm, but the correlation between having held a position within a national agency and being appointed at EU agencies with information and network coordination tasks becomes negative and strongly significant (−0.177 and −0.137, respectively), supporting the earlier observation that having had an agency background at the national level is highly positively correlated with appointments at stronger regulatory EU agencies.

Table 4. Correlation coefficients board member background and EU agency tasks (N = 1073).

Discussion

In the context of the EU governance, the empowerment of NRAs has meant a substantial overhaul of the community method approach to policymaking and implementation to an advanced, albeit often designated as experimentalist, forms of governance through regulatory networks (Bach et al., Citation2016; Dehousse, Citation1997; Egeberg, Citation2006; Jordana, Citation2017; Levi-Faur, Citation2011; Mastenbroek & Martinsen, Citation2018; Sabel & Zeitlin, Citation2008). Consequently, NRAs have come to ‘fill the gap’ inherent in the more traditional open method of coordination or comitology (Mastenbroek & Martinsen, Citation2018), contributing to the implementation of soft law in multiple policy areas in which the community method was not possible to be fully expanded (Terpan, Citation2015).

The top-down expansion of EAs with some additional delegation from member states in the European administrative space, has contributed to a complex dynamic of establishing an European executive power, where the Commission delegates to semi-autonomous agencies non-core activities (Christensen & Nielsen, Citation2010; Dehousse, Citation2008; Levi-Faur, Citation2011). However, the rapid spread of the agency model at the EU level benefited in many cases from existing networks of NRAs, initially driven by the need perceived by NRAs to solve problems of coordination that were not addressed by neither the Commission nor the member states (Coen & Thatcher, Citation2008). Accompanied by intense inter-institutional disputes and bargaining between the Commission, European Parliament and the Member States, the establishment of EAs strengthened the evolution of multi-level governance models beyond conventional designs and allowed NRAs to find a more formal place with European administrative space, being different options possible.

The results obtained in this paper provide support for our views and suggest a multidirectional understanding of agency autonomy. The data offer clear evidence regarding the connections between national and supranational regulators in Europe. This is revealed by mapping and tracing individual officials active in the EU governance space. We find representatives of NRAs, in particularly the agencies’ managing layers, have obtained multiple positions with the European administrative space. We can speak of the emerging of European transnational policy arena characterized by the occupation of multiple decision-making and advisory positions within key administrative bodies in the EU. Moreover, our findings in this study show a clear pattern in articulating this development, as the empirical results obtained confirm the relevance of these connections for those EU agencies having more regulatory activity. This is not a new mode of governance diffused to all policy areas in Europe. It remains quite limited to some areas of regulatory governance having significant powers delegated to Europe (i.e., single market act, ECB, pharmaceutical). However, these are very dynamic sectors, and the experimentalist governance logic, overcoming intergovernmental and supranational approaches, is very relevant.

Conclusion

The European administrative space has been one of the fastest transforming political and administrative domains in the world. Within less than a couple of decades, there has been a fundamental change of roles, positions and processes through which national and supranational governance actors have come to interact with each other and constitute new types of policy regimes across the EU. A fundamental driver of this transformation lies primarily with the NRAs of the member states. Established by member states’ governments and endowed with substantial amounts of autonomy, NRAs have been claiming their ground in and forged close ties with each other, resulting into trans-governmental networks. In this paper, we have argued that the evolution of the role and position of NRAs has been further advanced, up to the point where there is a meaningful distinction between levels of governance ceases to exist and we need to think of new concepts to study the further evolving of the European multilevel governance, claiming for new theoretical approaches beyond the dyadic autonomy model.

The concept of entangled agencies is very relevant to understand preference formation by NRAs in multi-level settings. They are national entities, that keep rooted at the domestic level, but interact and intermediate in the European administrative space as key actors within the composite regulatory regime. Despite the fact that the entanglements we found are sector-specific, meaning that with NRA representatives seated only in the boards within their own policy domain, the kind of entanglement this paper described empirically could also be understood as one where EA board members are rooted in national administrations, which is a potential counterforce to the development of a detached ‘regulatory elite’ at EU level.Footnote6 Enjoying delegated responsibilities allows them to show some separated preferences from governmental priorities and to articulate different strategies in European settings, more sector-centered in most cases, but without disconnecting from their national contexts. More often the in previous decades, NRAs tend to be involved in multilevel governance settings (national, European, inter-regional, global), establishing complex articulations by means of trans-governmental networks, or other forms of governance institutions, that also become reinforced by mechanisms that eventually allow agencies to be entangled across levels, as we have illustrated with the interlocking directories in the EU case. Some of these transformations of governance are more relevant than others for any particular case and sector, but new interpretative frameworks able to better explain complex interactions of delegation attributes, entanglement and multi-level connections are much needed to understand the current challenges and opportunities of NRAs in the age of global governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kutsal Yesilkagit

Kutsal Yesilkagit is a Professor of Public Administration at Leiden University. His main research interests is the relationship between politics and bureaucracy and how this relationship is influenced by internationalisation, regulatory governance, and populism.

Jacint Jordana

Jacint Jordana is Professor of Political Science and Administration at Pompeu Fabra University. He currently runs the Institut Barcelona d'Estudis Internacionals (IBEI). His main area of research focuses on the analysis of comparative public policies from a multilevel perspective, with special attention to regulatory policies and their specialised institutions.

Notes

1 Management boards provide strategic goals, appoint directors and supervise activities of EU agencies. They are a key element of EU agencies governance, and integrate diverse stakeholders in a single body, making decision-making of the agency more effective (European Parliament, Citation2021; see also European Court of Auditors, Citation2020). Although management boards in EU agencies are quite diverse regarding composition, procedures and working methods, as they follow different founding regulations, almost 80 per cent of them have large boards with more than 25 members (see ).

2 We thank on of our anonymous reviewers for sharing her/his thoughts on this point with us.

3 Busuioc follows a task-based classification of EU agencies, as she codes the primary objectives and tasks of EU agencies as they are described in the agencies’ founding legislation. Although both classifications are ordinal, we employed the Christensen and Nielsen classification as this one was constructed with the direct aim of distinguishing between degrees of agency autonomy.

4 The total number of positions reported (n = 1355) exceeds the total number of individuals in the dataset, as a number of these members have held multiple positions at the time of coding.

5 The ‘other’ category, if we limit it to previously held positions in the national public sector, contains a mix of non-ministerial agencies within the national judicial and police bodies.

6 We thank one of our anonymous reviewers for this observation.

References

- Abbott, K. W., Levi-Faur, D., & Snidal, D. (2017). Theorizing regulatory intermediaries: The RIT model. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 670(1), 14–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216688272

- Arras, S., & Braun, C. (2018). Stakeholders wanted! Why and how European Union agencies involve non-state stakeholders. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(9), 1257–1275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1307438

- Bach, T., De Francesco, F., Maggetti, M., & Ruffing E. (2016). Transnational bureaucratic politics: An institutional rivalry perspective on EU network governance. Public Administration, 94(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12252

- Bach, D., & Newman, A. (2014). Domestic drivers of transgovernmental regulatory cooperation. Regulation & Governance, 8(4), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12047

- Bach, T., Ruffing, E., & Yesilkagit, K. (2015). The differential empowering effects of Europeanization on the autonomy of national agencies. Governance, 28(3), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12087

- Barbieri, D. (2006). Transnational networks meet national hierarchies: The cases of the Italian competition and environment agencies. In M. Egeberg (Ed.), Multilevel union administration: The transformation of executive politics in Europe (pp. 180–193). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Bawn, K. (1995). Political control versus expertise: Congressional choices about administrative procedures. The American Political Science Review, 89(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2083075

- Bianculli, A. C., Jordana, J., & Juanatey, A. G. (2015). International networks as drivers of agency independence: The case of the Spanish nuclear safety council. Administration & Society, 49(9), 1246–1271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399715581034

- Blauberger, M., & Rittberger, B. (2015). Conceptualizing and theorizing EU regulatory networks. Regulation & Governance, 9(4), 367–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12064

- Buess, M. (2015). Accountable and under control: Explaining governments’ selection of management board representatives. Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(3), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12200

- Busuioc, M. (2013). EU agencies: Law and practices of accountability. Oxford University Press.

- Christensen, J. G., & Nielsen, V. L. (2010). Administrative capacity, structural choice and the creation of EU agencies. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(2), 176–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760903561757

- Coen, D., & Thatcher, M. (2008). Network governance and multi-level delegation: European networks of regulatory agencies. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X08000779

- Danielsen, O. A., & Yesilkagit, K. (2014). The effects of European regulatory networks on the bureaucratic autonomy of national regulatory authorities. Public Organization Review, 14(3), 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-013-0220-4

- Dehousse, R. (1997). Regulation by networks in the European community: The role of European agencies. Journal of European Public Policy, 4(2), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501769709696341

- Dehousse, R. (2008). Delegation of powers in the European Union: The need for a multi-principals model. West European Politics, 31(4), 789–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380801906072

- Eberlein, B., & Grande, E. (2005). Beyond delegation: Transnational regulatory regimes and the EU regulatory state. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(1), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176042000311925

- Eberlein, B., & Newman, A. L. (2008). Escaping the international governance dilemma? Incorporated transgovernmental networks in the European Union. Governance, 21(1), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00384.x

- Egeberg, M. (2006). Multilevel union administration. The transformation of executive politics in Europe. Palgrave studies in European Union studies. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Egeberg, M., & Trondal, J. (2009). National agencies in the European administrative space: Government driven, commission driven or networked? Public Administration, 87(4), 779–790. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01779.x

- European Court of Auditors. (2020). Future of EU agencies – potential for more flexibility and cooperation (Special report 22).

- European Parliament. (2021). The management boards of decentralized agencies. Policy Department for Budgetary Affairs.

- Gilardi, F. (2002). Policy credibility and delegation to independent regulatory authorities: A comparative empirical analysis. Journal of European Public Policy, 9, 873–893.

- Jordana, J. (2017). Transgovernmental networks as regulatory intermediaries: Horizontal collaboration and the realities of soft power. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 670(1), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716217694591

- Jordana, J., Pérez-Durán, I., & Triviño-Salazar, J. C. (2020). Drivers of integration? EU agency board members on transboundary crises. Comparative European Politics, 19, 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-020-00221-6

- Kelemen, R. D., & Tarrant, A. D. (2011). The political foundations of the Eurocracy. West European Politics, 34(5), 922–947. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.591076

- Levi-Faur, D. (2011). Regulatory networks and regulatory agencification: Towards a single European regulatory space. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(6), 810–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.593309

- Lodge, M., & Koop, C. (2014). Exploring the co-ordination of economic regulation. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(9), 1311–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.923023

- Maggetti, M., & Papadopoulos, Y. (2018). The principal–agent framework and independent regulatory agencies. Political Studies Review, 16(3), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929916664359

- Martens, M. (2006). National regulators between union and governments: A study of the EU’s environmental policy network IMPEL. In M. Egeberg (Ed.), Multilevel union administration: The transformation of executive politics in Europe (pp. 124–142). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Martinsen, D. S., Schrama, R., & Mastenbroek, E. (2021). Experimenting European healthcare forward. Do institutional differences condition networked governance? Journal of European Public Policy, 28(11), 1849–1870. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1804436

- Mastenbroek, E., & Martinsen, D. S. (2018). Filling the gap in the European administrative space: The role of administrative networks in EU implementation and enforcement. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(3), 422–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1298147

- McCubbins, M. D., Noll, R. D., & Weingast, B. R. (1987). Administrative procedures as instruments of political control. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 3, 243–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jleo.a036930

- Newman, A. L. (2010). International organization control under conditions of dual delegation: A transgovernmental politics approach. In D. D. Avant & M. Finnemore (Eds.), Who governs the globe? (pp. 131–152). Cambridge University Press.

- Pérez-Durán, I. (2019). Political and stakeholder’s ties in European Union agencies. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1375545

- Roger, C. B. (2020). The origins of informality: Why the legal foundations of global governance are shifting, and why it matters. Oxford University Press.

- Sabel, C. F., & Zeitlin, J. (2008). Learning from difference: The new architecture of experimentalist governance in the EU. European Law Journal, 14(3), 271–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2008.00415.x

- Saurugger, S., & Terpan, F. (2021). Normative transformations in the European Union: On hardening and softening law. West European Politics, 44(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1762440.

- Terpan, F. (2015). Soft law in the European Union – The changing nature of EU law. European Law Journal, 21(1), 68–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12090

- Weingast, B. R. (1984). The congressional-bureaucratic system: A principal-agent perspective (with applications to the SEC). Public Choice, 44(1), 147–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00124821

- Weingast, B. R., & Moran, M. J. (1983). Bureaucratic discretion or congressional control? Regulatory policymaking by the Federal Trade Commission. Journal of Political Economy, 14, 167–194. https://doi.org/10.1086/261181

- Yesilkagit, K. (2004). Bureaucratic autonomy, organizational culture, and habituation: Politicians and independent administrative bodies in the Netherlands. Administration & Society, 36(5), 528–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399704268501

- Yesilkagit, K. (2011). Institutional compliance. European networks of regulation and the bureaucratic autonomy of national regulatory authorities. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(7), 962–969. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.599965

Appendix

Table A1. Previous positions held by agency board members per EU agency.

Table A2. Tasks of regulatory and non-regulatory agencies.