?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

An important focus of empirical accounts of representative democracy is the policy-opinion nexus. Drawing from the thermostatic model (Wlezien, 1995), this study examines the dynamic relationship between public opinion and immigration policy, one of the more salient issue domains that have reshaped European democracies since the 1980s. As a counter-factual to social identity accounts of immigration politics, this study argues citizens have policy preferences and when immigration policy changes, the demand responds. The result is a known movement between opinions and policy that we describe as an ‘immigration thermostat’. We rely on dozens of high-quality surveys (more than 500 separate series, corresponding to nearly 2,500 marginals) and a dyadic-ratios algorithm to design comparable immigration opinion measures for 13 countries. We find evidence of both public and policy responsiveness for immigration, although not to the same extent. This suggests an asymmetrical ‘immigration thermostat’ but effective representation in the immigration domain across Western Europe.

Introduction

When we speak of democracy, we usually mean representative democracy. One of the primary concerns of representative democracy, and democratic theory more generally, is the symbiotic relationship between citizens and (the actions of) their representatives (Dahl, Citation1971; Manin, Citation1995; Przeworski et al., Citation1999). An important part of that literature focuses on the idea that public opinion engages in a responsive, so-called ‘thermostatic’, loop with policy-making (Wlezien, Citation1995). It proposes a constant, error corrective process between citizens’ preferences and the corresponding policies. When policy is less than perfect, i.e., different from the preferred levels of policy, citizens send a signal to adjust policy. Policy then changes in correspondence to public demands. The overall interdependence provides crucial insights into the performance and functioning of the political system and effective democracy.

This dynamic model of representation particularly holds in highly salient policy domains (Franklin & Wlezien, Citation1997). Most empirical evidence comes from spending-specific and economic interpretations of the policy-opinion nexus. Despite the complexification and expansion of citizen politics, only few studies examine the thermostatic model in socially or culturally salient dimensions of politics (see e.g., Enns, Citation2014; Jennings et al., Citation2017). A specific domain that remains understudied in this regard is immigration – one of the more politicised and pervasive issues across European democracies since the 1980s. Recent research has begun to address this gap (Ford et al., Citation2015; Jennings, Citation2009; Van Hauwaert & English, Citation2019), but its scope remains limited. Even more, nearly all applications of the thermostat focus exclusively on Anglo-Saxon countries (but, see e.g., Bartle et al., Citation2020; Bølstad, Citation2015; Romero-Vidal, Citation2020).

This study innovates by examining whether we can speak of an ‘immigration thermostat’ in a broader comparative context, namely across a wide range of West European democracies. That is, to what extent do citizens’ immigration opinions respond to policy signals? And, in turn, to what extent do immigration policies actually reflect what citizens want? Together, these questions allow us to explore public and policy responsiveness in an immigration context. Such a large scale comparative analysis of the thermostatic model is, to the best of our knowledge, unprecedented. A time-series cross-sectional design provides empirical support and allows for a first analysis of the immigration thermostat within and across 13 West European democracies since 1980.

The analysis first describes the structure of immigration opinions and policy across Western Europe, showing that immigration opinions entail much more between-country heterogeneity than immigration policy does. Building on this, separate analyses of public responsiveness and policy responsiveness bring forward a number of interesting observations. These analyses reveal that both dynamics are in play across Western Europe, but function asymmetrically. That is, public responsiveness to immigration policy is suggestive and either way less substantial than policy responsiveness, which – in turn – is mostly direct and much less – if at all – indirect. That means the actual policy feedback mechanism is not as strong (or relevant) as many studies have shown in economic domains. This shows a distinct operation of an immigration thermostat. At the same time, there is clear evidence of citizens’ input in a salient domain like immigration.

Immigration across Europe: inflows and trends

Immigration flows towards (and within) Europe are common since World War II, but have steadily increased since the 1960s. Particularly since the 1980s, immigration rates have accelerated both in speed and scale, with a sharp rise in the most recent decades. This includes a sizeable increase in both asylum seekers and economic immigration as part of what has been termed the ‘European migrant crisis’. The overall result is a sizeable immigrant population and a nearly universal and systematic increase in net migration rates across (West) European countries.

Immigration has subsequently become one of the more relevant and salient socio-political issues in European politics (Givens & Luedtke, Citation2004; Hatton, Citation2021). Since the 1980s, it dominates political and societal agendas in Western Europe (Green-Pedersen & Otjes, Citation2019; Morales et al., Citation2015). Particularly as of recent, the sequence of an economic, financial and migration crisis has maintained – and perhaps even strengthened – the status of immigration as one of the defining issues across advanced European democracies (Grande et al., Citation2019; Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2019). Overall, immigration and asylum have become fundamental public concerns and remain key political priorities across an institutionally and demographically diverse continent.

Particularly at election time, recent research indicates that increasing levels and the persistent prominence of immigration-related issues continue to drive political conflict (Grande et al., Citation2019). As a highly politicised issue, immigration thus has equitable polarisation potential for citizens, meaning that ‘reasonable people can take either side’ (Stimson, Citation1991). We understand – what we subsequently term – immigration opinions as a holistic and harmonised estimation that describes the evolution of a set of collective preferences or aggregated opinions towards the levels and impact of immigration for any given population. Such an interpretation is neither time- nor context-specific, which – in turn – allows for both cross-sectional and longitudinal claims (e.g., Claassen & McLaren, Citation2022; Van Hauwaert & English, Citation2019).

The evolution of immigration opinions remains the focus of contradictory research. One strand of literature underlines a general trend towards more restrictive immigration opinions as part of a right turn in European politics, following a cultural backlash or out of economic self-interest (Hainmueller & Hiscox, Citation2010). Opposite to this, other scholars suggest that individuals, on average, become less resistant to immigration (Coenders & Scheepers, Citation2008) or remain largely stable in terms of their anti-foreigner sentiments (Lahav, Citation2004).

Altogether, empirical results are often mixed, as citizens vary widely in their views of immigrants and migration, while not all countries exhibit the same developments at the same time and to the same degree (Heath & Richards, Citation2019). That means a single homogeneous trend across Europe is unlikely to comprehensively describe opinion movement. In part, this results from the continuous but contextually distinct interplay between immigration opinions (demand) and immigration policy (supply). We describe this relationship as an ‘immigration thermostat’ in the following section.

An immigration thermostat

In highly politicised domains, governments and legislators give credence – or pay more attention – to what citizens want, while citizens – in turn – notice and respond to the actions of policy-makers (Erikson et al., Citation1989; Citation1993).Footnote1 Concretely for immigration, this means immigration policy signals citizens to become more or less restrictive in their opinions, which policy-makers then reflect accordingly. Any deviations from the ‘normal’ distance between opinions and policy tend to be corrected over time, resulting in a continuous and equilibrating process of opinion-policy realignment. With that in mind, this study relies on Wlezien's (Citation1995) original thermostatic model and Jennings (Citation2009)’s ingenious application to immigration in Great Britain to comparatively describe how preference adjustment (public responsiveness) and political response (policy responsiveness) come together in the immigration domain. The following sections describe the theoretical model in more detail.

Immigration opinions and public responsiveness

Existing studies argue that citizens are responsive to changes in their social, economic and political environment through a process of adaptive feedback (Ellis & Faricy, Citation2011; Stevenson, Citation2001). This means citizens recognise and adjust to policy changes. For a rational population, there is a diversity of individual preferences where some want more restrictive immigration policy than others and the median value in the aggregate distribution of immigration opinions represents the ‘ideal’ position. As such, the public as a whole has a preference for either ‘more’ or ‘less’ restrictive immigration policy. This preference is relative because it adjusts in response to policy changes. When immigration policy moves outside the public’s ‘moderate zone of acceptability’, immigration opinions react by demanding a return to more acceptable levels. When the public responds to immigration policy, immigration sentiment actually contains meaningful information.

Following a thermostatic logic, we can then theorise that the public’s relative preferences (R) represent the difference between preferred (or ideal) levels of policy (P*) and actual policy levels (P). The formal expression becomes:

(1)

(1) where subscripted k and t apply to country and time, respectively. Equation (1) shows citizens prefer less restrictive immigration policy when actual policy is more restrictive than ideal policy (Pkt > Pkt). When actual policy is less restrictive than preferred policy (Pkt < Pkt), citizens signal their desire for more restrictive immigration policy. Put differently, this model argues that immigration opinions move opposite to (immigration) policy change.

In practice, it is likely not possible to directly observe P*, making it necessary to rely on instruments (Durr, Citation1993). By implication, the three variables in Equation (1) are not (by default) measured using the same metric. It is, therefore, fundamental to extend equation (1) as follows:

(2)

(2) where β0k and ekt represent the intercept and error term, respectively, and Ukt is a set of exogenous predictors of P*. The policy coefficient β2k forms the crux of the thermostatic model and the foundation of effective accountability and political alternation (Bartle et al., Citation2011). This equation further confirms that measured preferences are not the same as absolute preferences. The degree to which they differ can vary through time and between countries, as indicated by the subscripts of Pkt.

There is ample indication of public responsiveness across the literature, but still primarily related to economic issues in Anglo-Saxon countries (e.g., Bartle et al., Citation2011; Citation2019; Erikson et al., Citation2002; Soroka & Wlezien, Citation2004; Citation2005). Beyond these traditional domains, Jennings et al. (Citation2017) confirm the British public responds to government outputs in the criminal justice domain, while Ford et al. (Citation2015) suggest open immigration policies in Great Britain are associated with restrictive immigration opinions. Even though Hjerm (Citation2007) indicates that xenophobia across Europe moves together with governments’ ambitions to increase immigration levels, more comprehensive and large-scale comparative evidence of public opinion realigning (thermostatically) in direct response to policy movement remains rather limited (but see, Eichenberg & Stoll, Citation2003; Citation2017).

We know that public responsiveness depends on the salience of the policy domain (Franklin & Wlezien, Citation1997). Almost by definition, policy-makers and media outlets spend more time discussing highly salient issues. This eventually results in more (accurate) information being available about the policy domain and citizens paying more attention to policy-making in such domains (Zaller, Citation1992).Footnote2 Differently put, when an issue is salient, citizens are typically more responsive to changes in government behaviour.Footnote3 Since immigration dominates the political space and dictates the public debate, we expect high levels of public responsiveness in the immigration domain across European democracies. Conversely, immigration salience is not necessarily stable. It is even likely to fluctuate through time and in light of exogenous events (Hatton, Citation2021). This further confirms the initial expectation that public responsiveness differs through time and, more notably, between countries.

Policy responsiveness and the dynamic representation of immigration opinions

If there is public responsiveness, the question is whether policy-makers actually notice opinion shifts and if policy decisions eventually also reflect citizen preferences. For immigration specifically, we wonder to what extent shifts in immigration opinions are, on average, followed by corresponding shifts in immigration policy? If policy-makers are truly responsive to the public, policy change (ΔP) will reflect public opinion levels (R) and partisan control of government (G).Footnote4 We anticipate immigration policy changes in the same direction as immigration opinions, meaning policy-makers – by and large – give citizens what they want in anticipation of electoral penalties and rewards (Hellwig & Samuels, Citation2008). This can be formally expressed as follows:

(3)

(3) where γk0 and ekt represent the intercept and error term, respectively.Footnote5 The equation captures the extent to which immigration opinions are both directly and indirectly reflected in policy decisions. This is what Jennings (Citation2009, p. 851) calls ‘the parallel components of political responsiveness to public opinion’. On the one hand, it captures direct responsiveness (γ1k), i.e., the dynamic policy adjustments that reflect opinion shifts, independent of party or government control. On the other hand, γ2k captures indirect responsiveness through electoral representation, as it becomes mediated through responsible parties and governments. Together, they constitute what some refer to as ‘the dynamic representation of public opinion’ (Stimson et al., Citation1995).

Scholars systematically show that – in Anglo-Saxon countries – budgetary expenditure (Brooks & Manza, Citation2006; Page & Shapiro, Citation1992; Soroka & Wlezien, Citation2010), legislative behaviour (Erikson et al., Citation1993; Erikson et al., Citation2002; Stimson et al., Citation1995) and government positioning (Bartle et al., Citation2011; Citation2019) closely track preferences. This is the case for general public opinion, as well as for more policy-specific preferences related to gay rights (Lax & Phillips, Citation2009), abortion (Arceneaux, Citation2002) and punitiveness (Enns, Citation2014). More comparative evidence further confirms that concrete government outputs indeed reflect public opinion, most notably in the fields of redistribution (Brooks & Manza, Citation2008; Ezrow et al., Citation2020), the environment (Anderson et al., Citation2017), defence spending (Eichenberg & Stoll, Citation2003), Muslims (Cinalli & Van Hauwaert, Citation2021) and independence (Romero-Vidal, Citation2020).

So far, the policy responsiveness scholarship has only spent limited attention on immigration. Freeman (Citation1995) suggests there is a ‘policy gap’, arguing that government action is slow to reflect immigration opinions. Research on public attention and agenda-setting in the immigration domain further confirms this (Morales et al., Citation2015). Considering the regulatory nature of immigration, it is likely that policy is (also) shaped by elites, such as interest groups (Rasmussen et al., Citation2014), whose views do not always align with the public. This results in what Statham and Geddes (Citation2006) refer to as ‘top-down’ immigration policy-making. Jennings (Citation2009) and Ford et al. (Citation2015), nonetheless, show that British policy-makers are sensitive to changes in public views about immigration. They argue that policy change is an incremental process that can change pace following direct and indirect responsiveness. The comparative nature of these mechanisms has yet to be comprehensively assessed.

Combining Equations (2) and (3) suggests mutual influence between immigration policy and opinions does not necessarily occur at the same time. Restrictive immigration opinions in year t-1 render immigration policy more restrictive in year t, which – in turn – affects immigration opinions in the opposite direction in year t. That is, when the public responds to immigration policy, policy-makers will - or are likely to - respond in kind. That is the core of the thermostatic model. Yet, that does not mean we expect public and policy responsiveness to apply equally or in perfect synchrony across all countries or at different points in time. Even quite the opposite (compare e.g., Wlezien (Citation1995) in the USA and Soroka and Wlezien (Citation2004) in Canada with Soroka and Wlezien (Citation2005) in the UK). After all, effective democracy – while important – is never perfect. As we already highlighted before, differences in immigration salience and the public and policy incentives play a role in responsiveness dynamics being different within and between countries. How this model performs for immigration, through time and between countries, is something we have to assess empirically.

Data and instruments

To examine the immigration thermostat across countries, we need reliable time-series cross-sectional (TSCS) data on immigration opinions and policies. The bounds of both components of the TSCS design are set by the available public opinion data. The analysis ranges from 1980 to 2017, and includes 13 European democracies, namely Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland.

Measuring immigration opinions

One of the principal challenges to accurately measure immigration opinions in their politically effective sense (Converse, Citation1987) is the robust longitudinal study and interpretation of public opinion. Survey questions are often only conducted with limited frequency (e.g., around elections) or repeated for a narrow period (or not at all). This is unfortunate considering the interest of much macro polity research lies in the temporal variations in responses to repeated survey items. Unlike some other issues with more long-standing survey traditions (e.g., social class or democratic satisfaction), [most] cross-national surveys have not always included questions regarding some of the ‘new’ political issues, such as immigration, globalisation or European integration.

While immigration has been highly salient since the early 1980s, repeated survey items still remain limited. There are some instances where immigration is covered well in national surveys, particularly in countries with long-standing histories of immigration, such as France, Germany and Great Britain. This has its advantages for single country studies, but it remains challenging for comparative analyses. For instance, while cross-national surveys are typically quite consistent in their design and question wording, and thereby premised on the equivalence of meanings and scores for the underlying theoretical constructs, this is not always the case for national surveys. They are more pragmatic in their design, often depending on which issues are salient, and resulting in changing question wordings and answer categories. This complicates the design of consistent time-series that are long, dense and broad enough to tap into the broader notion of immigration opinions. The result is typically the use of only a limited range of sources (e.g., Bohman & Hjerm, Citation2016; Ford, Citation2008; Hatton, Citation2021), a snapshot of multiple sources that remain temporally limited (e.g., Semyonov et al., Citation2006) or the use of data from commercial polls but not from high quality cross-national sources (e.g., Ford et al., Citation2015).

From a comparative perspective, we must thus strive towards composite measures as much as possible. With that in mind, we take a more comprehensive approach and use an unprecedented number of survey items collected as part of the Global Public Opinions Project to measure immigration opinions. The selected items concern all questions with reference to positions towards immigration or immigrants, positions towards government policy regarding immigration, positions towards immigrants or other general non-native minorities, economic or cultural implications of immigrants or immigration, xenophobia and prejudice.Footnote6 From this broad selection, we identify those items with at least two observations throughout the time frame under analysis and calculate (weighted) immigration-related marginals.Footnote7 While item frequencies vary widely, some of the more prominent item series ask about marriage with foreigners (Germany, 15 administrations), whether there are too many immigrants (France, 15 administrations), promotion or dismissal of foreigners over natives (Netherlands, 21 administrations) and equal chances between foreigners and natives (Switzerland, 24 administrations).

For each country, we then employ a dyadic ratios algorithm to harmonise the information into an aggregate measure of immigration opinions (Stimson, Citation1991). This technique allows us to estimate an over-time measure of the public’s support (low values) or opposition (high values) to immigration and immigrants, thereby capturing both direction and magnitude. The dyadic ratios algorithm presupposes that, to the extent a particular time series of a single item can be considered a valid indicator of immigration opinions, the change between any two values within that time series (a dyad-ratio) is a relative indicator of immigration opinions over time. Repeated across each point in time for each individual time series, the algorithm then estimates the covariance between the dyadic-ratios of each item. From this covariance, it then calculates validity estimates for the different dyad-ratio series and uses these to estimate the best possible latent measure of immigration opinions. The algorithm then uses these estimates (the dyad-ratio series combined and adjusted according to their covariance) to estimate immigration opinion values at each available user-defined interval (in our case per year). Further exponential smoothing increases the estimation’s accuracy by accounting for potential sampling error and bias. This estimation procedure for immigration opinions is then repeated for each country in the study.Footnote8

The result is 13 country-specific immigration opinion measures that comprise an unprecedented amount of information. provides an overview of the source information for each country. While the actual number of input series varies between countries – from 24 in Austria to 82 in Germany – the combined immigration opinion measures rely on 2,461 survey marginals (an average of nearly 200 per country) to form 518 distinct dyad-ratio series (an average of nearly 40 per country). We additionally find that one unique dimension, which we theorise as immigration opinions, accounts for an average of nearly 60 per cent of the explained variance (Eigen Estimate) across the country-specific measurement models.Footnote9 The proportion of explained variance is robust to the issues used (or dropped) to estimate the overall index. That is, the common variance remains similar regardless of how we estimate the aggregate immigration opinions measure.

Table 1. Source information, by country.

Measuring immigration policy

Finding available measures of immigration policy – at least in terms of outcomes – in any European democracy is challenging for two reasons. First, unlike spending, ‘more’ or ‘less’ immigration policy does not by default relate to specific policy positions. In that regard, some argue that immigration – at least at a very basic level – might be considered a valence issue (Green, Citation2007; Odmalm & Bale, Citation2015). This would imply there is a broad consensus on its policy-ends. In this scenario, citizens agree on an ideal immigration position and judge policy-makers according to their competence in achieving ‘more’ or ‘less’, rather than ‘either-or’ (Stokes, Citation1963). While this is certainly more the case today than it was in the 1980s, an important segment of the citizenry still thinks of immigration in ideologically polarising terms, rather than just quantifying the end result as ‘too much’ or ‘too little’. That means there is little systematic congruence between citizens and elites in terms of immigration policy.

Second, the European democracies under analysis are typically fairly restricted in their policy-making abilities related to immigration because of their participation in the European Single Market.Footnote10 As a consequence, immigration regimes are relatively stable across European democracies. This impedes a policy operationalisation in line with much of the Anglo-Saxon research, namely through appropriations of budget authorities or government expenditure. Even if data on ‘immigration spending’ were consistently available, it does not necessarily or automatically reflect policy positions.

Unfortunately, the current state of annual immigration policy data across Europe is rather poor, particularly compared to the available policy data in the USA. Most available datasets have a limited geographical or temporal scope. Therefore, drawing from Jennings (Citation2009) and similar to Givens and Luedtke (Citation2005), we primarily rely on the OECD’s inflow of asylum seekers and the resulting number of asylum seekers per one thousand heads of the population as a proxy for immigration policy.Footnote11 This relative rate is a direct consequence of the remaining immigration policy freedoms and, given the previously mentioned restrictions, a close indicator of an explicit choice for a restrictive or inclusive immigration policy environment.

We rely on the annual inflow rather than measuring the total number of asylum seekers, as the latter stock measure reflects a longer policy track-record and we are more interested in the immediate regulatory effects. Drawing from a social identity framework, there is clear evidence that immigrant and asylum groups are treated and perceived differently, as they have different origins and provoke distinct reactions with the native publics (Ford, Citation2011; Kessler & Freeman, Citation2005; Lahav, Citation2004; Sniderman et al., Citation2004). This not only alludes to the conceptually distinct character of both groups, but also to the subsequent operational singularity of the proposed policy indicator.Footnote12

We recognise this kind of proxy measure is not your standard immigration policy indicator. With that in mind, we also set out to cross-validate our findings using more traditional indicators. On the one hand, we use the general Immigration Policy Index (AvgS ImmPol) from the Immigration Policies in Comparison (IMPIC) project. On the other hand, we rely on the Low-Skill Immigration Policy Dataset (IMMIPOL variable). Both of these data sets present comprehensive instruments. That being said, we do not use these indicators as our primary variables because both data sets provide insights into public policy understood as the policy regime, i.e., the country-specific regulations on immigration, whereas we are more interested in actual policy outcomes, such as the stock indicators we propose above. Additionally, both data sets are slightly outdated (1980-2010) and they draw on expert opinions rather than actual policy.

The structure of immigration opinions and policy

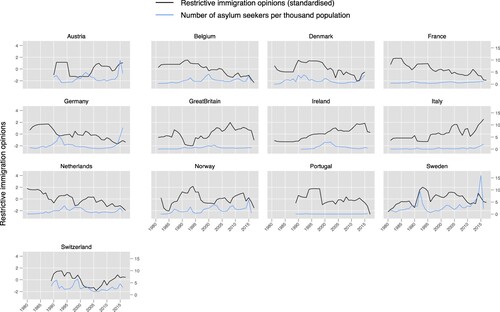

We know that immigration opinions have some context-specific patterns (Ford et al., Citation2015; Jennings, Citation2009; Van Hauwaert & English, Citation2019), but we know little about its larger-scale comparative idiosyncrasies. To examine this, plots immigration opinion measures for 13 European democracies. Even though the results from the dyadic-ratios algorithm are in and of themselves relative opinion measures, the absolute values of each measure are dependent on a country’s individual series so we standardise the measures using country-means. The same Figure includes the policy indicator on the right Y-axis.

Figure 1. Restrictive immigration opinions and asylum rates, by country (1980-2017).

Note: Immigration opinions have been standardised within each country. Higher values indicate more restrictive opinions.

accentuates there is no clear homogeneous evolution of immigration opinions across advanced European democracies. The defining feature of the opinion measures is cross-country variability. Citizens in Belgium, Denmark and Germany are almost systematically becoming less restrictive towards immigration. In other countries, such as Ireland, Italy and – to some extent – Great Britain, we see a broader anti-immigrant trend, or Verrechtsing. In most countries, however, immigration opinions appear cyclical in nature, meaning periods of restrictive opinions follow more permissive trends and vice versa. By and large, this is what we anticipated from the public opinion literature and the public responsiveness equations. At first sight, cyclical dynamics appear to be unrelated to elections and crises.

further illustrates this. While the average levels of the original immigration opinion scale have a limited range across countries (between 42 and 52 on a 100-point scale), the standard deviations indicate country-specific patterns of variance. Overall, the cross-national variability is relatively low, particularly compared to the average levels, suggesting movement is not erratic per se. Yet, some countries, like Norway (std. dev. = 7.35) and Switzerland (std. dev. = 8.09), show more variation in immigration opinions than others, like France (std. dev. = 3.70) and the Netherlands (std. dev. = 4.15).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics across years, per country.

More importantly, however, is that immigration opinions covary – although not perfectly – over time and a trend in one country tends to translate to other countries. The average inter-item correlation of 0.87 further indicates that immigration opinions do not move in perfect sync and some of their movement is independent.Footnote13 The factor analysis in confirms there is indeed underlying movement across most countries that accounts for about half of the cross-country variance (EV = 6.75).Footnote14 This suggests a certain degree of parallelism, or mood (Romero-Vidal & Van Hauwaert, Citation2022; Stimson, Citation1991). There is shared movement that might (collectively) drive politicians’ behaviour in various countries, or what we could refer to as the ‘immigration climate’.Footnote15 Yet, at the same time, the covariation is not of the magnitude where we can speak of a singular global immigration mood.

Table 3. Summarised factor results of immigration opinions.

There is clear within-country movement of immigration opinions as well. Based on the uniqueness estimates in , an average of about 12 percent of the variance remains ideosyncratic (ranging from 3 percent in Austria to 30 percent in Portugal). This independent movement suggests that, at least to a certain degree, thermostatic dynamics likely vary across countries, as per the above theorisation. It highlights that we are warranted in thinking of these opinion measures as distinct from each other, yet with shared features – much like overlapping Venn diagrams.

The asylum rates in advance a relatively homogeneous trend, namely a gradual increase for most countries, particularly in the last decade or so. This surely goes hand in hand with the European migrant crisis, as the average asylum rate nearly doubled before and after 2010. This gradual trend is primarily propelled by frequent and sudden upward surges towards more openness. In the long term this contributes to incremental change, much like the fall-out of terrorist events or economic crisis, because even in the short-term policy never completely returns to its original levels. The average asylum rates in highlight that Austria, Sweden and Switzerland systematically have the highest asylum rates of the countries under analysis.Footnote16 The low standard deviations of South European countries (France, Italy, Portugal, Spain) and Great Britain suggest these countries maintain a fairly stable (and low) asylum rate through time.

Empirical results: public responsiveness

The public responsiveness equation indicates that levels of immigration opinions (R) are the difference between preferred levels of immigration policy (P*) and policy itself (P). highlights a heterogeneous pattern of covariance between immigration opinions and immigration policy, with an average correlation of 0.26. While we, thus, have measures of both available, we do not have direct measures of P*. In line with the literature, we therefore rely on instruments for P*.

We know that public opinion and economic conditions closely track one another, to the extent that Stevenson (Citation2001, p. 620) refers to this connection as a ‘fundamental dynamic of democratic politics’. Related to immigration opinions, extant literature also describes how anti-immigrant sentiments, often expressed as support for anti-immigrant policies (Arzheimer, Citation2009), increase when (short-term) economic performance stagnates (Hatton, Citation2016). This stems from the belief that expanding economies reduce competition for economic or financial resources and make them less scarce, which – in turn – reduces hostilities towards immigrants. With that in mind, and in line with much of the responsiveness literature, we use an economic indicator as a proxy of P*. Reflecting the TSCS structure of the data, our proxy indicator must provide comparative and standardised measures through time and across countries. Therefore, we rely on a GDP per capita measure and the unemployment rate. Drawing from the literature, we also control for each country’s immigration rate, as the public is responsive to societal inputs as well – most notably when they directly relate to the preferences at hand.Footnote17

We subsequently examine whether immigration opinions respond to changes in immigration policy and economic conditions. We design a time-series cross-sectional regression model, where change in immigration opinions at time t is estimated as a function of change in the predictors in the previous year t-1. We model the first differences because a set of augmented Dickey-Fuller tests of the different variables, most notably immigration opinion measures, do not reject the null hypothesis of the presence of a unit root throughout the time period under analysis, and this in all countries.Footnote18 The model is fitted with the Prais-Winsten method to control for panel-specific serial autocorrelation of the residuals, estimated as a first-order autoregressive process.Footnote19

The first four models in summarise the results of different TSCS models. The last two models further cross-validate these findings and provide reassurance that the previously modelled and observed relationships are not artefacts of spurious relationships in the aggregate data, potentially due to the estimation of the dependent variable or data availability. Model 5 excludes data from all country-year immigration opinions that were interpolated by the dyadic-ratios algorithm, engaging in an analysis with observed data only. Model 6 re-estimates immigration opinion measures in more data rich environments, i.e., starting only in the 1990s, while simultaneously excluding Austria and Italy.

Table 4. Public responsiveness for immigration.

From Equation (2), we expect immigration policy to thermostatically feed back into immigration opinions. That means immigration opinions should become more restrictive as immigration policies become more permissive. indeed shows the inflow of asylum seekers systematically has the expected positive sign across the different models, thereby suggesting immigration opinions and policy move opposite one another. As immigration policy becomes more permissive (restrictive), restrictive immigration opinions increase (decrease). A rough approximation of the coefficient sizes indicates that an additional 10 asylum seekers per year per 1,000 population would shift public opinion with only one percent. Considering our sample has a cross-country average of 1.2 asylum seekers per 1,000 population, this remains rather symbolic and substantively unimpactful. It is also worth highlighting that the policy coefficients do not reach conventional levels of significance in any of the model specifications. Even though the signal remains obscure and could be argued to hide cross-national patterns of variance within Europe, the policy coefficients nonetheless suggest thermostatic politics in the immigration domain and, thereby, effective accountability and political alternation.

At the same time, the immigration rate coefficient is also positive across all models. It surpasses conventional levels of significance in the more complete models, which means the public effectively reacts to the country’s immigration rate and non-asylum inflows (perhaps even more so than asylum inflows). That is, citizens become more restrictive in their immigration opinions when immigration rates increase and the number of foreigners actually increases (Van Hauwaert & English, Citation2019; Claassen & McLaren, Citation2022).

Together, these inflow variables suggest that while immigration opinions are shaped by exogenous societal dynamics and policy outcomes, the public primarily responds to changes in outcomes that are beyond the national government’s control. As our measure for immigration opinions reflects what citizens think about immigration more generally, this should also not be that surprising. It furthermore shows the public is able to distinguish between governmental policy and other causes of immigration flow, which further reinforces our perception of a ‘rational’ and sufficiently informed public.

Across the different models we also find consistent results for the economic indicators. Results confirm that higher levels of unemployment and decreasing levels of GDP per capita contribute to more restrictive immigration opinions. That essentially means both indicators have pro-cyclical effects on immigration opinions and anti-immigrant opinions increase when (short-term) economic performance stagnates (Arzheimer, Citation2009; Hatton, Citation2016; Semyonov et al., Citation2006). An economy under pressure experiences increased competition, thereby making economic and financial resources scarcer, which – in turn – increases hostility towards outsiders like immigrants. The increased risk exposure that stems from economic hardship will relate to more restrictive immigration opinions. While this finding aligns with an extensive ‘group threat’ and ‘relative deprivation’ scholarship, it also supports a long-standing literature that argues for a positive relationship between prosperity and more progressive values and the more specific claims that higher levels of economic prosperity stimulate more emancipative processes, such as more openness and less restrictive immigrant opinions (Welzel, Citation2013).

Empirical results: policy responsiveness

In light of immigration opinions changing in response to environmental stimuli, the question remains if we also find evidence of policy outcomes, in turn, responding to citizens’ immigration opinions. After all, the thermostatic model posits that elected representatives should adjust immigration policies to offer reassurance to citizens wanting more permissive or restrictive policies. The actual outcomes of these responses can be multifaceted and are contingent on power positions, institutional arrangements and the political system, on the one hand, and public opinion, on the other. With that in mind, we harmonise models of direct and indirect policy change to examine both aspects of representation simultaneously.

Following equation (3), we use the first difference of the immigration policy indicator as the dependent variable. This is, in part, due to the integrated nature of the policy indicator, but also because we are interested in policy change, not levels.Footnote20 We expect that changes in immigration policy for year t follow immigration opinion levels in year t-1, i.e., the year when the actual policy decisions for fiscal year t are made. Also following equation (3), we expect governments to affect policy change. We use the cabinet composition variable (Schmidt-Index) from the Comparative Political Data Set (Armingeon et al., Citation2018) as an indicator of the partisan control of government. This variable ranges from ‘one’ to ‘five’, with ‘one’ indicating hegemony of right-wing parties and ‘five’ indicating hegemony of left-wing parties in government.Footnote21 We additionally control for two baseline variables, namely GDP per capita and unemployment, drawing from earlier accounts that the available policy space is directly dependant on economic conditions (Bartle et al., Citation2019).Footnote22 Finally, we add a dummy for the asylum crisis to make sure the latter years of our time-series do not skew our overall findings.

Prais-Winsten regressions subsequently control for serial auto-correlation of the residuals, estimated as the first-order autoregressive process.Footnote23 shows the results of different policy change models. In the first two models, we include public opinion and government party as separate indicators of direct and indirect responsiveness, respectively. In the third model, we also control for economic conditions. Much like in , models four and five provide additional cross-validation by providing models using non-interpolated public opinion data only (model 4) and public opinion data since the 1990s, while excluding Austria and Italy (model 5). Results are consistent between different models.

Table 5. Policy responsiveness for immigration.

As expected, the negative coefficient of immigration opinions indicates that the inflow of asylum seekers decreases when the public becomes more anti-immigrant. That is, citizens essentially get what they want. The policy space moves in the direction citizens want it to move. While this is in line with general expectations regarding policy responsiveness (Wlezien, Citation2017) and its application to the immigration domain more specifically (Jennings, Citation2009), its consistent observation across Western Europe confirms the application of core democratic principles in one of Europe’s most salient policy domains. Particularly in a time where the issue of immigration has become more apolitical (and perhaps moral), this can serve as reassurance for the state of representative democracy.

also returns the expected positive sign for indirect responsiveness, suggesting that left-wing governments tend to be more permissive and allow more asylum seekers than right-wing governments. This strokes with the literature arguing that governments are partisan vessels and execute the mandates that have been given to them by citizens. Differently put, left-wing governments represent left-wing interests, while right-wing governments promote more right-wing policies (Allan & Scruggs, Citation2004). This is not only true in prominent socio-economic domains, like redistribution (Brooks & Manza, Citation2008), but also in more socio-cultural ones, like immigration (Ford et al., Citation2015; Jennings, Citation2009).

At the same time, recent scholarship tends to find reduced relevance of such partisan effects or even null-findings in this regard (Loftis & Mortensen, Citation2017). The absence of conventional levels of statistical significance in might, thus, serve as confirmation of such an (at best) uncertain effect. It may very well be that the power of organised interests, specific barriers to government or external pressures from supranational organisations (like the EU) constrain the policy freedom of national governments and limit the corresponding budgetary resources, thereby leaving only limited margins for policy manoeuvring. While this observation might, of course, hide cross-national variation within Europe, it appears to reject the notion of ‘top-down’ immigration policy-making, as argued by Statham and Geddes (Citation2006), at least in the most general sense. We are, therefore, careful drawing decisive conclusions regarding indirect policy responsiveness in the immigration domain.

Nonetheless, we find evidence of (primarily, direct) policy responsiveness across Europe in the immigration domain, while the previous section reported suggestive evidence of public responsiveness. Combining these two observations, this would suggest we can confirm our theoretical expectations of an immigration thermostat across Europe. Considering the clear significance of the direct policy responsiveness coefficient and a public responsiveness coefficient that does not reach conventional significance levels, we might draw the additional conclusion that the policy signal is more relevant than the public signal. That is to say, policy outcomes in the domain of immigration clearly reflect what citizens want, whereas the policy signal itself is to a lesser extent accounted for or visible to citizens formulating their immigration opinions. It is entirely possible – perhaps even likely – that the public seeks its information about immigration, not from the government directly, but elsewhere. Altogether, this suggests that democratic functioning is rather asymmetrical in the field of immigration.

Discussion and implications

An extensive body of research provides empirical insights into the functioning of the thermostat. This, amongst others, highlights patterns of variance across countries and domains, as well as a certain asymmetry between public and policy responsiveness dynamics. Yet, so far, at least three caveats remain.

First, nearly all studies focus on the Anglo-Saxon countries, thereby leaving broader comparative insights largely unexplored. Second, much empirical evidence relies on spending preferences and actual spending. This provides valuable insights into distinct aspects of the policy-opinion nexus but inhibits a more comprehensive understanding of its intricacies. Third, and unsurprisingly, most empirical applications target economic interpretations of politics. After all, early research indicates that issue salience plays an important role and politics is largely about ‘who gets what’. Yet, only a disproportionate number of studies explore the thermostat in socially and culturally salient issue dimensions – something that since the 1980s is a vital part of politics. With these considerations in mind, we explore the idea of an immigration thermostat in a comparative European context.

This study examines public and policy responsiveness separately, which leads to some noteworthy initial findings. First, we find evidence that the public adjusts its relative immigration opinions in response to the corresponding immigration policies. We find negative policy feedback in the immigration domain across Western Europe. Opposite to economic interpretations of the thermostat, however, we are also able to identify increasing anti-immigration opinions over time in reponse to increasing levels of unemployment and decreasing levels of GDP per capita. This confirms the differences between relative and absolute preferences, even in the immigration domain.

We also observe that immigration policies follow changes in immigration opinions over time. This, by and large, confirms that citizens tend to get what they want. In other words, there is clear evidence of policy responsiveness in the immigration domain across Europe. This policy signal primarily comes directly from citizens and to a much lesser extent through elections and policy-makers in place. While this provides some reassurance of democratic functioning in an important policy domain, it is to a certain extent surprising, as an increasing scholarship highlights the democratic schism between the public and their elites and a so-called 'democratic deficit' at the heart of contemporary politics.

Combined, the systematic interplay between demand and supply provides insights into the effective democratic character of a political system and highlights that democratic principles are in effect, at least at a very general level, in the immigration domain across Europe. Moreover, we can speak of an immigration thermostat across Europe, meaning citizens send their immigration signals to policy-makers, who subsequently incorporate these in their policy decisions. In turn, these immigration policies serve as input signals for citizens upon the formation of their immigration opinions. This signal takes the form of thermostatic feedback, meaning more restrictive (permissive) policies tend to impede (stimulate) anti-immigrant sentiment. Yet, we must note that interplay between public and policy is not perfect, as policy is more responsive than the public. Such asymmetry is normal and highlight the (normal) imperfections of effective democracy.

Obviously, this analysis is but a first step into a more profound understanding of how the immigration thermostat might function and affect democratic functioning across European democracies. As we know from previous literature on the thermostat, it can show country-variation in terms of both public and policy responsiveness. This, for example, is already clear from the variation between domains and countries in the relatively homogeneous set of Anglo-Saxon countries explored by Soroka and Wlezien (Citation2010). Therefore, a necessary next step in this analysis is the disaggregation of the cross-national findings to further explore patterns of variance within Europe. This would provide insights into how certain institutional and political dynamics relate to the policy-opinion nexus. Additionally, for some of these countries, it might also be possible to explore different policy indicators that can provide more profound and comprehensive insights into immigration outputs and its related dynamics.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (203.6 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and journal editors for their detailed comments and feedback, as well as their patience with my request for additional time. Their support and flexibility have been an integral part of this paper’s quality. I would like to express my explicit gratitude to Ryan Carlin, Will Jennings, Xavier Romero-Vidal and Chris Wlezien for their valuable input on various iterations of this manuscript. Previous versions of this paper have been presented at the 2018 ECPR General Conference in Hamburg and the 2019 Elections, Public Opinion and Parties Conference at the University of Strathclyde. I thank all panel participants for their questions and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Steven M. Van Hauwaert

Steven M. Van Hauwaert is currently an Excellence Fellow at Radboud University and an Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at Forward College, as well as the principal investigator of the Global Public Opinions Project and a team leader for Team Populism.

Notes

1 In the absence of this reciprocity, there is little to no incentive for policy-makers to give any weight to what citizens want. Not only would there be no point, but there would be no actual cost of not doing so. As Soroka and Wlezien (Citation2004, pp. 533–534) argue, ‘There not only would be a limited basis for holding politicians accountable; expressed preferences would be of little use even to those politicians motivated to represent the public for other reasons’.

2 Soroka and Wlezien (Citation2010) show the thermostat does not work in all domains, however. When salience is low, there might not be public responsiveness or a thermostatic relationship.

3 This is not always the case. Much depends on complementary societal conditions, none of which are more important than the salience of other – competing – issues.

4 Earlier research indicates that policy hardly ever matches opinion shifts perfectly and government control – indirectly – plays a considerable role. In some cases, this might even outweigh direct responsiveness (e.g., Bartle et al., Citation2019).

5 Notice that policy change in year t is a function of public opinion (and partisan control of government) in year t-1. This reflects the reality of budget decision-making, which typically occurs in the previous fiscal year. Even in a ‘perfect’ democracy, there must be a lag between a political or public signal and its actual consequences.

6 We exclude items that inquire about racism, Muslims, refugees, asylum seekers and illegals. For more details regarding the individual items we included, the question wording, the years of measurement and the degree of repetition, we refer to Section A of the supplementary materials. includes an overview of the total number of questions (often across different surveys) and administrations in every country.

7 These refer to the percentage of respondents selecting a ‘left’ or ‘right’ option, ‘supporting’ or ‘opposing’ immigrants and immigration, ‘agreeing’ or ‘disagreeing’ with immigration-related statements.

8 Please consult Stimson (Citation1991; Citation2018) for a more extensive and in-depth discussion of the formal estimation procedure. Alternative estimation tools produce similar results and are available upon request (e.g., unsmoothed series). We also cross-validate our measures in various way, including (a) an estimation with an IRT algorithm (McGann, Citation2014) instead of the dyadic ratios algorithm, (b) tracking long item series as proxies for the estimated measures, and (c) excluding these longest item series and compared the estimated measures with and without them.

9 Section A.3 of the supplementary materials provide a more detailed account of the item loadings and descriptive variable information for all countries. The algorithm also calculates the proportion of variance explained by the dimension it extracts (two by default). Even though there are traces of a second, more composite dimension, the EV of 0.12 indicates it explains a far smaller proportion of the common movement and matters relatively little.

10 The European Single Market guarantees the free movement of goods, capital, services and labour within the EU. This has been extended, beyond the EU member states, to Iceland and Norway through the Agreement on the European Economic Area and to Switzerland through bilateral treaties.

11 Find the data here: https://www.oecd.org/els/mig/keystat.htm

12 Overall, the correlation coefficients between the number of immigrants (foreigners) and asylum seekers are – at best – moderate. This substantiates the conceptual independence between both groups.

13 The average inter-item correlation decreases only minimally when we exclude the three countries that have a reverse trend compared to the others, namely Great Britain, Ireland and Italy. For more detailed information about the alpha test scales and inter-item covariance of the public opinion series, we refer to Tables A.4 and A.5 in the supplementary materials, respectively.

14 The factor analysis returns additional factors as well, most notably two with Eigenvalue larger than one. This not only confirms there is more national movement than a single cross-national trend, but it might suggest certain regional patterns are worth exploring. Results remain consistent if we exclude the three countries with a reverse overall trend in immigration opinions (Great Britain, Ireland and Italy).

15 With the exception of Austria, all countries load alongside that first dimension with sizeable factor loading scores. This observation might very well be the results of data scarcity, rather than of Austria being an exceptional case escaping the European immigration climate.

16 After 24 November 2015, asylum regulations in Sweden become much more restricted. As a result, the inflow of asylum seekers more than doubled compared to the previous year. Yet, as we exclude 2015 from the mean calculation, Sweden remains the country with the highest average asylum rate (mean = 2.85; std. dev. = 1.88).

17 The GDP measure represents GDP per head of population (in thousands of USD, constant prices, 2010 PPPs). The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the labour force. The immigration rate is the inflow of foreigners per one thousand heads of the population. All variables are collected from the OECD, at https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx.

18 We include country-specific Augmented Dickey-Fuller tests and more detailed analyses of autocorrelation in sections C and D of the supplementary materials.

19 Section E in the supplementary materials includes regressions with lagged dependent variables to capture potential autocorrelation between the residuals and account for other omitted variables (Beck & Katz, Citation2011), as well as the time-series cross-section variant of a single-equation error correction model (Beck, Citation2001). We also include models with the IMPIC policy indicator.

20 We include country-specific Augmented Dickey-Fuller tests of the main immigration policy indicator in section D of the supplementary materials.

21 The data set includes values until 2015, which we complete for 2016 and 2017.

22 We use various specifications of the baseline variables, including inflation and the misery index. Substantive results remain largely unchanged.

23 Section F in the supplementary materials includes alternative models similar to the public responsiveness analysis, namely models using a lagged dependent variable, a cross-sectional ECM estimation and a model using the IMPIC policy index as the dependent variable.

References

- Allan, J. P., & Scruggs, L. (2004). Political partisanship and welfare state reform in advanced industrial societies. American Journal of Political Science, 48(3), 496–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00083.x

- Anderson, B., Bo ̈hmelt, T., & Ward, H. (2017). Public opinion and environmental policy output: A cross-national analysis of energy policies in Europe. Environmental Research Letters, 12(11), 114011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8f80

- Arceneaux, K. (2002). Direct democracy and the link between public opinion and state abortion policy. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 2(4), 372–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/153244000200200403

- Armingeon, K., Wenger, V., Wiedemeier, F., Isler, C., Kno ̈pfel, L., David, W., & Engler, S. (2018). Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2016.

- Arzheimer, K. (2009). Contextual factors and the extreme right vote in Western Europe, 1980-2002. American Journal of Political Science, 53(2), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00369.x

- Bartle, J., Bosch, A., & Oriolls, L. (2020). The policy mood in Spain: The thermostat in a warm climate, 19782017. European Political Science Review, 12(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577392000003X

- Bartle, J., Dellepiane-Avellaneda, S., & McGann, A. (2019). Policy accommodation versus electoral turnover: Policy representation in britain, 19452015. Journal of Public Policy, 39(3), 235–265. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X18000090

- Bartle, J., Dellepiane-Avellaneda, S., & Stimson, J. A. (2011). The moving centre: Preferences for government activity in britain, 19502005. British Journal of Political Science, 41(2), 259–285. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123410000463

- Beck, N. (2001). Time-series–cross-sectiondata: What have we learned in the past few years? Annual Review of Political Science, 4(1), 271–293. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.271

- Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (2011). Modeling dynamics in time-SeriesCross-section political economy data. Annual Review of Political Science, 14(1), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-071510-103222

- Bohman, A., & Hjerm, M. (2016). In the wake of radical right electoral success: A cross-country comparative study of anti-immigration attitudes over time. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(11), 1729–1747. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1131607

- Bølstad, J. (2015). Dynamics of European integration: Public opinion in the core and periphery. European Union Politics, 16(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116514551303

- Brooks, C., & Manza, J. (2006). Why do welfare states persist? The Journal of Politics, 68(4), 816–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00472.x

- Brooks, C., & Manza, J. (2008). Why welfare states persist: The importance of public opinion in democracies. University of Chicago Press.

- Cinalli, M., & Van Hauwaert, S. M. (2021). Contentious politics and congruence across policy and public spheres: The case of muslims in France. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(14), 2532–2550. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1831567

- Claassen, C., & McLaren, L. (2022). Does immigration produce a public backlash or public acceptance? Time-series, cross-sectional evidence from 30 European democ- racies. British Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 1013–1031.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000260

- Coenders, M., & Scheepers, P. (2008). Changes in resistance to the social integration of foreigners in Germany 1980–2000: Individual and contextual determinants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830701708809

- Converse, P. E. (1987). Changing conceptions of public opinion in the political process. Public Opinion Quarterly, 51(Part 2: Supplement: 50th Anniversary Issue), S12–S24. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/51.4_PART_2.S12

- Dahl, R. A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition. Yale University Press.

- Durr, R. H. (1993). What moves policy sentiment? American Political Science Review, 87(1), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938963

- Eichenberg, R. C., & Stoll, R. (2003). Representing defense. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 47(4), 399–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002703254477

- Eichenberg, R. C., & Stoll, R. J. (2017). The acceptability of war and support for defense spending. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(4), 788–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715600760

- Ellis, C., & Faricy, C. (2011). Social policy and public opinion: How the ideological direction of spending influences public mood. The Journal of Politics, 73(4), 1095–1110. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381611000806

- Enns, P. K. (2014). The public’s increasing punitiveness and Its influence on mass incarceration in the United States. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 857–872. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12098

- Erikson, R. S., MacKuen, M. B., & Stimson, J. A. (2002). The macro polity. Cambridge University Press.

- Erikson, R. S., Wright, G. C., & McIver, J. P. (1989). Political parties, public opinion, and state policy in the United States. American Political Science Review, 83(3), 729. https://doi.org/10.2307/1962058

- Erikson, R. S., Wright, G. C., & McIver, J. P. (1993). Statehouse Democracy: Public Opinion and Policy in the American States. Cambridge University Press.

- Ezrow, L., Hellwig, T., & Fenzl, M. (2020). Responsiveness, if you can afford It: Policy responsiveness in good and bad economic times. The Journal of Politics, 82(3), 1166–1170. https://doi.org/10.1086/707524

- Ford, R. (2008). Is racial prejudice declining in britain? The British Journal of Sociology, 59(4), 609–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.00212.x

- Ford, R. (2011). Acceptable and unacceptable immigrants: How opposition to immigration in Britain is affected by migrants' region of origin. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(7), 1017–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.572423

- Ford, R., Jennings, W., & Somerville, W. (2015). Public opinion, responsiveness and constraint: Britain’s three immigration policy regimes. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(9), 1391–1411. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1021585

- Franklin, M. N., & Wlezien, C. (1997). The responsive public: issue salience, policy change, and preferences for European unification. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 9(3), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692897009003005

- Freeman, G. P. (1995). Modes of immigration politics in liberal democratic states. International Migration Review, 29(4), 881–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839502900401

- Givens, T., & Luedtke, A. (2004). The politics of European union immigration policy: Institutions, salience, and harmonization. Policy Studies Journal, 32(1), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0190-292X.2004.00057.x

- Givens, T., & Luedtke, A. (2005). European immigration policies in comparative perspective: Issue salience, partisanship and immigrant rights. Comparative European Politics, 3(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110051

- Grande, E., Schwarzbözl, T., & Fatke, M. (2019). Politicizing immigration in Western Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(10), 1444–1463. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1531909

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Otjes, S. (2019). A hot topic? Immigration on the agenda in Western Europe. Party Politics, 25(3), 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817728211

- Green, J. (2007). When voters and parties agree: Valence issues and party competition. Political Studies, 55(3), 629–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00671.x

- Hainmueller, J., & Hiscox, M. J. (2010). Attitudes toward highly skilled and Low-skilled immigration: Evidence from a survey experiment. American Political Science Review, 104(01), 61–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990372

- Hatton, T. J. (2016). Immigration, public opinion and the recession in Europe. Economic Policy, 31(86), 205–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiw004

- Hatton, T. J. (2021). Public opinion on immigration in Europe: Preference and salience. European Journal of Political Economy, 66, 101969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2020.101969

- Heath, A. F., & Richards, L. (2019). Contested boundaries: Consensus and dissensus in European attitudes to immigration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(3), 489–511.https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550146

- Hellwig, T., & Samuels, D. (2008). Electoral accountability and the variety of democratic regimes. British Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 65–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000045

- Hjerm, M. (2007). Do numbers really count? Group threat theory revisited. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(8), 1253–1275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830701614056

- Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (2019). Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 996–1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619801

- Jennings, W. (2009). The public thermostat, political responsiveness and error-correction: Border control and asylum in britain, 1994–2007. British Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 847–870. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712340900074X

- Jennings, W., Farrall, S., Gray, E., & Hay, C. (2017). Penal populism and the public thermostat: Crime, public punitiveness, and public policy. Governance, 30(3), 463–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12214

- Kessler, A. E., & Freeman, G. P. (2005). Public opinion in the EU on immigration from outside the community. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 43(4), 825–850. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2005.00598.x

- Lahav, G. (2004). Public opinion toward immigration in the European union Comparative Political Studies, 37(10), 1151–1183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414004269826

- Lax, J. R., & Phillips, J. H. (2009). Gay rights in the states: Public opinion and policy responsiveness. American Political Science Review, 103(03), 367–386. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990050

- Loftis, M. W., & Mortensen, P. B. (2017). A new approach to the study of partisan effects on social policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(6), 890–911.

- Manin, B. (1995). Principes du gouvernement représentatif. Calmann-Levy.

- McGann, A. J. (2014). Estimating the political center from aggregate data: An item response theory alternative to the stimson dyad ratios algorithm. Political Analysis, 22(1), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt022

- Morales, L., Pilet, J.-B., & Ruedin, D. (2015). The Gap between public preferences and policies on immigration: A comparative examination of the effect of politicisation on policy congruence. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(9), 1495–1516. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1021598

- Odmalm, P., & Bale, T. (2015). Immigration into the mainstream: Conflicting ideological streams, strategic reasoning and party competition. Acta Politica, 50(4), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.28

- Page, B. I., & Shapiro, R. Y. (1992). The rational public: Fifty years of trends in Americans’ policy preferences. University of Chicago Press.

- Przeworski, A., Stokes, S. C., & Manin, B. (1999). Democracy, accountability, and representation. Cambridge University Press.

- Rasmussen, A., Carroll, B. J., & Lowery, D. (2014). Representatives of the public? Public opinion and interest group activity. European Journal of Political Research, 53(2), 250–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12036

- Romero-Vidal, X., & Van Hauwaert, S. M. (2022). Polarisation between the rich and the poor? The dynamics and structure of redistributive preferences in a comparative perspective. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 34(1), 1–19.https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edab015

- RomeroVidal, X. (2020). Two temperatures for one thermostat: The evolution of policy attitudes and support for independence in catalonia (19912018). Nations and Nationalism, 26(4), 960–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12559

- Semyonov, M., Raijman, R., & Gorodzeisky, A. (2006). The rise of anti-foreigner sentiment in European societies, 1988-2000. American Sociological Review, 71(3), 426–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100304

- Sniderman, P. M., Hagendoorn, L., & Prior, M. (2004). Predisposing factors and situational triggers: Exclusionary reactions to immigrant minorities. American Political Science Review, 98(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305540400098X

- Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2004). Opinion representation and policy feedback: Canada in comparative perspective. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 37(3), 531–559. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423904030860

- Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2005). Opinionpolicy dynamics: Public preferences and public expenditure in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Political Science, 35(04), 665–689. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123405000347

- Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2010). Degrees of democracy: Politics, public opinion, and policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Statham, P., & Geddes, A. (2006). Elites and the ‘organised public’: Who drives British immigration politics and in which direction? West European Politics, 29(2), 248–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380500512601

- Stevenson, R. T. (2001). The economy and policy mood: A fundamental dynamic of democratic politics? American Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 620–633. https://doi.org/10.2307/2669242

- Stimson, J. A. (1991). Public opinion in America: Moods, cycles, and swings. Westview Press.

- Stimson, J. A. (2018). The dyad ratios algorithm for estimating latent public opinion. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, 137-138(1), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0759106318761614

- Stimson, J. A., MacKuen, M. B., & Erikson, R. S. (1995). Dynamic representation. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 543–565. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082973

- Stokes, D. (1963). Spatial models of party competition. American Political Science Review, 57(2), 368–377. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952828

- Van Hauwaert, S. M., & English, P. (2019). Responsiveness and the macro-origins of immigration opinions: Evidence from Belgium, France and the UK. Comparative European Politics, 17(6), 832–859. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-018-0130-5

- Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising: Human empowerment and the quest for emancipation. Cambridge University Press.

- Wlezien, C. (1995). The public as thermostat: Dynamics of preferences for spending. American Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 981–1000. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111666

- Wlezien, C. (2017). Public opinion and policy representation: On conceptualization, measurement, and interpretation. Policy Studies Journal, 45(4), 561–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12190

- Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge University Press.