ABSTRACT

In this article, we contribute to the literature on (post-)exceptionalism by analysing and explaining the development of a specific policy sub-arrangement of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP): its monitoring and evaluation (M&E) arrangement. As M&E have become common in many policy sectors, this arrangement seems an example of common policy being integrated in the CAP, reflecting non-exceptionalism. To answer the question to what extent M&E policy ideas are indeed integrated in the CAP we adopt a policy arrangement approach and analyse the interaction of institutions and ideas found in the broader EU M&E and CAP policy arrangements during two reforms of the CAP. We conclude that general ideas on M&E have been incorporated in the CAP M&E arrangement, but only to a limited extent. Existing institutions (and resulting interests) of the broader CAP arrangement prevent a full integration of these ideas. This leads to the general conclusion that the M&E sub-arrangement in the CAP is characterized by post-exceptionalism.

1. Introduction

Agriculture is a policy domain in which states strongly intervene to achieve important objectives, particularly food security and sufficient farm income. Legitimation for interventionist policies is usually based on the claim that agriculture is different from other economic sectors: farming is a risky enterprise due to uncertain natural impacts as well as volatile market conditions beyond farmers’ control. This exceptionalist status, in which institutions bring together a small set of like-minded actors from national governments and groups representing farmers’ interests, makes change in this policy difficult and incremental (Smith, Citation1992 in Greer, Citation2017).

Over the past decades, however, this exceptionalist status has come under pressure, partly due to the increasing interconnectedness between agriculture and environmental, trade and social policies. To analyse to what extent and how agriculture moves away from its exceptionalist status and what effects this has, Daugbjerg and Feindt (Citation2017) turn to four dimensions of this policy domain: institutions, actors/interests, ideas and policies. These dimensions are related; together, they form a so-called policy arrangement. In an exceptionalist policy arrangement, they argue, ideas that a policy sector is special lead to an institutionally backed restrictive involvement of actors/interest, and policies that will reflect these interests and ideas.

Turning to the different dimensions of agricultural policy arrangements allows us to carefully trace changes in their exceptionalist status. When focussing on the different dimensions of the policy arrangement of the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) we find, for example, that the actors/interests dimension is more open to a diversity of interests, the ideas dimension is characterized by a greater variety of perspectives and that more sweeping changes take place in the policy dimension. At the same time, however, we also find that existing practices continue. Daugbjerg and Feindt (Citation2017) therefore describe the situation of the CAP as a post-exceptionalist one, in which old and new elements combine. Analyses of the 2013 CAP reform (Greer, Citation2017) and of environmental policy integration in the CAP (Alons, Citation2017) support their analysis that the CAP is moving in a post-exceptionalist direction, even though that post-exceptionalism may be minimal. Greer (Citation2017), for this reason, refers to a shallow post-exceptionalism.

In this paper, we further develop the work on the (post-)exceptionalist character of the EU agricultural sector. We do so, in part, by turning to the Policy Arrangement Approach (PAA) developed by Arts et al. (Citation2006), a well-defined theoretical approach that also focuses on the content and organization of a policy domain by turning to different dimensions. While the PAA uses a slightly different categorization of dimensions than Daugbjerg and Feindt (Citation2017), the approaches are comparable in analysing change and stability in policy domains. Below we will draw on several PAA insights to elaborate how changes in policy arrangements can be explained. In doing so, we stick, however, to the dimensions of Daugbjerg and Feindt (Citation2017).

Instead of analysing changes in the exceptionalist status of the CAP as a whole, we zoom in on its monitoring and evaluation (M&E) policy sub-arrangement, which is embedded in the CAP arrangement. M&E frameworks have become common in many sectors that are faced with expectations to assess and increase policy effectiveness (OECD, Citation2020, p. 3). This trend also applies at the EU level, where policy evaluation (and to a lesser extent monitoring) has become common, with a leading role for the European Commission (Stern, Citation2009, p. 71). That institution’s secretariat-general has developed various evaluation guidelines (e.g., European Commission (COM), Citation2015) which have to be followed by the directorates-general (DGs), including DG Agriculture.

The M&E framework which has developed for the CAP therefore appears to be an example in which broader ideas and policies are integrated in the CAP, giving it a less exceptionalist status. To what extent the development of a M&E framework indeed has a ‘normalizing’ effect on various aspects of the CAP is investigated in this paper, by analysing the establishment of the Common Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (CMEF) during the 2013 CAP reform, and its more recent conversion into a Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (PMEF). Specifically, we turn to the (dimensions of the) general EU M&E policy arrangement and the broader CAP policy arrangement in which the CAP M&E framework is embedded. The latter allows us to also draw conclusions about how the broader CAP arrangement limits or enables changes taking place in its sub-arrangements. Specifically, we ask the following two-fold question:

To what extent has the CAP monitoring and evaluation policy sub-arrangement integrated dimensions of the general EU monitoring and evaluation policy arrangement?; and

how can this degree of integration be explained by the embeddedness of the CAP monitoring and evaluation sub-arrangement in the broader CAP arrangement?

This study not only sheds further light on processes of change and stability in exceptionalist policy arrangements such as the CAP, but also contributes to the literature on monitoring and evaluation policy. In the context of the CAP, firstly, little scholarly attention has been given to this in general (but see Bozzini & Hunt, Citation2015) or from the view of exceptionalism, other than to the evaluation of the CAP’s environmental consequences (Alons, Citation2017). By applying the concept of policy arrangements, secondly, we follow the suggestion of Trochim (Citation2009) to apply standard approaches of the policy process – which have been used so far to explain the stability and change of sectoral policies – to account for the development of monitoring and evaluation policies. In the evaluation literature it is increasingly recognized that evaluation policy is ‘contingent on complex societal contexts, such as institutions, norms and power’ (Højlund, Citation2014). The concept of policy arrangements provides a way to consider these contextual factors.

In Section 2 below, we set out the Policy Arrangement Approach and discuss the different dimensions of a policy arrangement. We subsequently develop a general expectation about the interaction between the dimensions of different policy arrangements. We present our research methodology and operationalization in Section 3. We continue by describing the different dimensions of the general EU M&E and broader CAP arrangement in Section 4. Based on this, we translate our general expectation into case-specific hypotheses about the CAP M&E sub-arrangement. In Section 5 we present our analysis of the development of the CAP M&E policy arrangement over time. In Section 6 we answer our research question and reflect on our hypotheses and the broader implications of our research.

2. Analytical framework

Daugbjerg and Feindt (Citation2017) use four dimensions to describe a policy arrangement: policy, ideas, interests and institutions. The first part of this section discusses these dimensions; the second part elaborates on the interactions between them. We use the M&E literature to provide illustrations for how the different dimensions may manifest themselves in the case of M&E. These illustrations thereby also highlight several aspects that will come back in the analysis in Sections 4 and 5. The third part of this section explains the relationship between different arrangements and closes with a general expectation about the conditions under which (the dimensions of) an arrangement is likely to affect another arrangement.

2.1. Dimensions

The first dimension, policy, refers to specific measures or instruments that guide actors to reach particular goals. In the case of M&E, these measures guide organization’s actions when conducting evaluations (cf. Trochim, Citation2009). The typical actions of M&E (Eckhard & Jankauskas, Citation2019) relate to (i) initiating M&E; (ii) the narrowing down of the questions, criteria and methodology; and (iii) presenting the findings. With respect to the questions and criteria, different M&E models can be specified in an evaluation policy (Hansen, Citation2005).

The second dimension of a policy arrangement, ideas, provides a foundation to think about how situations can and should be dealt with. Ideas consist of beliefs about what is going on and what is appropriate. These beliefs may be about what role ‘evaluative information’ can and should play in policy-making. In the evaluation literature we find two such beliefs. A first belief is that governments require systematic and continuous evidence about the working of their policies. According to this functionalist ‘evidence-based policy’ belief, evaluative information about how policies work can and should produce the evidence to improve a policy’s performance (Fitzpatrick, Citation2012, p. 479; Sanderson, Citation2002; Vedung, Citation1997, p. 109). A second belief is that policy-makers should be accountable and that evaluative information can contribute to this. In relation to spending policies, such as the CAP, it is often considered important ‘that funds are actually expended for stipulated purposes (and) that programmes are carried out as intended … ’ (Stephenson, Citation2015).

The third dimension of a policy arrangement is actors/interests. The M&E literature recognizes that monitoring and evaluations can be strategic tools that can strengthen or weaken the positions of actors involved in policy-making processes (Schwartz, Citation1998; Vedung, Citation1997). The evaluation literature specifies different stakeholders and the (evaluation-related) interests they have. An important group to consider are the beneficiaries of existing policies. Evaluations used for resource redistribution decisions (like the CAP) will particularly trigger resistance from vested interests (Wergin, Citation1976, p. 76). Another interest group are policy-makers, for whom evaluations introduce the risk of undermining hard-fought legislative compromises and reopening dossiers. At the same time, policy-makers also have an interest in having effective and widely supported policies, which strengthens the need to evaluate (Bovens et al., Citation2008, p. 323; Weiss, Citation1993). Another group of actors, finally, are those responsible for delivering policies. Such implementing actors may, for example, fear that evaluations lead to demands to roll back their competences or put them under closer supervision (Vedung, Citation1997, pp. 102–108) or lead to additional workload (Beijen et al., Citation2014).

The final dimension is institutions: rules and norms that allocate responsibilities and duties to certain actors in the policy making process. Depending on these institutions, actors have an opportunity to be involved in the development of evaluation policies and may control evaluations’ questions, criteria, indicators, data, budget and/or time constraints (LSE GV314 GROUP, Citation2014).

2.2. Arrangements

The dimensions of a policy arrangement are interrelated. When actors, for example, hold the idea that evaluation should lead to learning, process models – which focus on the input and policy implementation process – are likely to be part of the evaluation policy (Hansen, Citation2005). When vested interests play an important role in an arrangement, to give another example, it can be expected that actors will try to reduce or limit policies on the initiation of evaluations to maintain the status quo. Those in favour of changes in the distribution of public spending, on the other hand, may push for policy provisions on initiating evaluation or monitoring. There can also be an interest in limiting monitoring and evaluation costs, which may impact the policy on indicators or data used for monitoring and evaluation. Likely, this interest would lead to calls to reduce the administrative burden, in particular when certain actors do not clearly feel the need to evaluate.

Based on the configuration of the four dimensions, different types of policy arrangements can be described and compared. Liefferink (Citation2006), for example, focusing on the relationship between state, market and civil society in general, refers to étatist, liberal-pluralist, and neo-corporatist policy arrangements. In these ideal types, the different dimensions are largely internally congruent. In practice, however, this is not always the case: there can be an incongruence between different dimensions, in particular between the policy dimension and the other dimensions. Several authors have pointed out, for example, that in practice, ideas are often used rhetorically (Hart, Citation2015); ideas and policies are incongruent in that case. Daugbjerg and Feindt (Citation2017, p. 1579) explain a similar incongruence for the CAP by turning to the existing institutions and interests and describe the result of this as a tense post-exceptional policy arrangement; in this case ‘old and new ideational, institutional, interest group and policy components co-exist in an unbalanced way’. This unbalance can lead to tensions and criticism.

2.3. Explaining stability and change

The interrelatedness of dimensions means that changes in one dimension can lead to sequential changes in other dimensions (Daugbjerg & Feindt, Citation2017; Liefferink, Citation2006). A change in institutions, for example, will often lead to a change in actors/interests. Changes, however, may also be set in motion by alterations in the broader social, political, economic or physical environment, or result from the interaction with other policy arrangements. Policy arrangements often overlap or are nested and their dimensions may transcend or set the conditions for other arrangements (Liefferink, Citation2006).

The Policy Arrangement Approach (PAA) does not formulate precise expectations about when dimensions of arrangements affect others. Based on the literature on multi-level governance and implementation (e.g., Moulton & Sandfort, Citation2017; Ostrom et al., Citation2014), however, some general expectations can be formulated about the interrelations between ideas and institutions: their impact will depend, largely, on their so-called density, i.e., their authority and specificity (Moulton & Sandfort, Citation2017).

The density of the institutions and ideas dimension is shaped foremostly by their authority. Authority refers to the legitimacy of a dimension, which can be based on (and measured by) different sources. In the case of institutions, authority is often based on tangible formal (sanctioned) rules or well-established norms. In the case of ideas, authority is typically based on the general acceptance or taken-for-grantedness of particular beliefs (Sandfort & Moulton, Citation2015). When authority is low, density is also low. When authority is high, we also need to consider the specificity of the dimensions to more precisely establish their density. Specificity refers to the room for manoeuvre that is provided by the dimensions. Formal rules often provide discretion. The same goes for norms and ideas; these may be varied or need to be interpreted or translated. below summarizes this logic.

Table 1. Density of institutions and ideas (the boldness of the type of density reappears in the and below).

The more dense specific dimensions are, the more likely they will set the conditions for the dimensions of another arrangement (cf. Liefferink, Citation2006, p. 65). So, when a policy arrangement (A) is connected to other arrangements (B and C) the more dense dimensions among B and C will likely have a greater effect on these dimensions of arrangement A. In order to translate this general expectation into more case-specific hypotheses about the integration of the general M&E arrangement into the CAP, it is necessary to first analyse the density of these dimensions for the general EU M&E and the broader CAP arrangements. We do this in Section 4, after explaining the research methodology we applied.

3. Method

In this article, we analyse the development of the CAP M&E arrangement with a specific focus on two moments of change. The analysis of the two changes is based on an interpretation of qualitative data. This data includes official publications on the EU and CAP evaluation policy (including legislative proposals and impact assessments by the European Commission, legislative amendments by the Council and European Parliament, as well as communications and position papers of all legislative actors about the CAP); minutes and agendas of the so-called (agriculture) monitoring and evaluation expert group, which was set up to discuss and develop the CAP M&E framework, and which includes officials of all member states; different opinion papers, reports and blogpost by stakeholders and observers (e.g., www.arc2020.eu and www.capreform.eu); and available secondary literature. Documents were purposefully selected by the authors based on their relevance. In addition, backward snowballing was used; in documents we found, we checked the references for finding other relevant documents (Badampudi et al., Citation2015).

In addition, nine interviews were held with eight involved actors, including two Commission officials working for DG AGRI (in May 2015 and May 2019 with one official and in August 2019 with another), two NGO-representatives (in January 2019 and November 2020), a close academic observer of the CAP (June 2020) and three Dutch policy officials involved with practical and technical discussions on M&E of the CAP (June 2020). The selection of three officials from the same member state was based on practical grounds. As the information provided by them was largely of a technical nature, this selection does not create bias. The interviews were primarily used to check our interpretation of the written sources and to ask detailed questions about the interrelation between the dimensions of the policy arrangements. The interview guides were semi-structured and attuned to the different roles and position of the respondents. All interviews were recorded.

The four dimensions of a policy arrangement formed the basis for our semi-structured interview protocols and document analysis. We operationalized policy as specific measures or instruments that prescribe how to meet certain goals. These are typically described in detail in policy or legislative documents. Ideas were understood as shared understandings about the usefulness and appropriateness of policy goals and instruments. These understandings shape and justify the choice for certain policy instruments.

Interests were operationalized as stakeholder’s specific material or political concerns. Data on these two dimensions were retrieved from answers to interview question about the rationale behind certain policies, as well as from explanatory memoranda found in legislative proposals or policy communications. Institutions, finally, were operationalized as norms or rules that provide actors certain responsibilities to act. Data on institutions was initially retrieved from interviews to find out which rules and norms operated as such in practice. Document analysis was used to specify information on this dimension. In analysing the different dimensions of the M&E arrangements we further focused on the different facets of these dimensions that were discussed in Section 2. This operationalization is summarized in .

Table 2. Measurement of the dimensions of a policy arrangement.

To formulate hypotheses about the impact of the broader CAP and EU M&E arrangements, we specifically focussed on the density of the institutions and ideas dimensions of these arrangements, which consist of the authority and specificity of institutions and ideas. To measure the authority of institutions we turned to their embedding in formal law and established norms. To measure the authority of ideas we turned to their general acceptance among actors in the arrangement. In case of formalization or taken for grantedness we interpreted this as high authority. To measure the specificity of institutions and ideas we analysed the room for manoeuvre these dimensions provide to follow them. This is summarized in .

Table 3. Measurement of the density of institutions and ideas.

4. Case-specific hypotheses

Before turning to the analysis of the changes in the CAP M&E arrangement, we will first render our general expectations about the impact of the ideas and institutions dimension into case-specific hypotheses. We do so based on a preliminary analysis of the density of the institution and ideas dimensions of the broader CAP and the general EU M&E arrangements.

4.1. EU monitoring and evaluation arrangement

Ideas about the importance of evaluation are well-established within the general EU M&E policy arrangement. Most ideas are promoted by the Commission, which links evaluation in functional terms to processes of learning and better regulation (Højlund, Citation2014), but also to reducing administrative burdens (COM, Citation2015, p. 254). The multifacetedness of these policy ideas allows member states room for manoeuvre in aligning their policy ideas with the Commission’s. These ideas also hold authority: they find general support by member state governments in the Council, and in the EP (European Parliament et al., Citation2016, article 1 and 13–20). Ideas on monitoring are less well developed or accepted. Monitoring is generally seen as a way to provide data for carrying out (ex post) evaluations (COM, Citation2015, p. 246), but this idea has not led to specific guidelines (Voorst et al., Citationin press). Based on the above, the density of the idea dimension in the general M&E arrangement can be considered moderately high.

When it comes to institutions, the general EU M&E arrangement grants most formal power to develop M&E policies to the European Commission. Within the Commission, powers to develop these policies are further attributed to individual evaluation units inside the different DGs. These units are networked together and coordinated by the Commission’s Secretariat General (COM, Citation2015, p. 257; Stern, Citation2009, p. 71). The authority of these institutions can be considered high given the formalization of this policy. This decentralized structure, at the same time, leaves discretion to the different DGs to decide whom to involve in (developing) evaluation (policies) or to delegate (parts of) the evaluation and monitoring of policies to the member states. The specificity of these institutions can therefore be considered low. As a result, the density of this dimension is defined as low.

4.2. CAP arrangement

Within the broader CAP, we find several ideas related to M&E. The need to simplify the CAP in particular is an idea that has gained authority over the last two decades (Alons & Zwaan, Citationin press). These ideas could be absorbed in the CAP M&E framework: monitoring and evaluation can provide input for simplification. Another idea that has general support is the need to increase the credibility of the CAP: M&E could increase transparency, but also the performance of the CAP (Zwaan & Alons, Citation2015). At the same time, member states seem to have a strong view that there should be only limited room for M&E in the policy making processes. In a discussion on a comprehensive evaluation of the CAP, member states explicitly stressed that decisions on the CAP are the results of ‘highly detailed compromises’ reached ‘by means of rather complex agreements’ (REFIT Platform, Citation2016). This idea seems to have a high authority and can be considered specific, giving it a great density. The other ideas related to M&E, however, are moderately dense: while they have authority, they lack specificity.

When we focus on the institutions dimension of the broader CAP arrangement, we find great authority, at least when it comes to the rules for developing the main legislation on M&E. Based on formal law, the Council and the European Parliament (EP) have co-decision powers over the CAP ‘s main legislation. Existing norms on the other hand, make that the Council typically takes the lead, as a result of its former role as main decision maker on the CAP and the fact that the implementation of the CAP depend on its expertise (Knops & Swinnen, Citation2014). These institutions are specific in affecting who can decide on the general contours of M&E framework – and can therefore be seen as dense – but they also condition which specific institutions will be created to further implement the main legislation on M&E: it can be expected that these, to a large extent, will mirror the norms/rules found in the general CAP arrangement.

4.3. Hypotheses

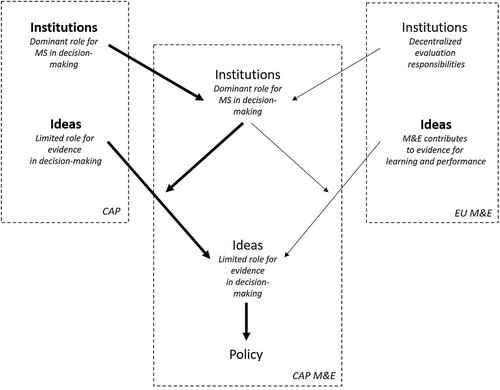

When we consider the density of the institutions of the general M&E arrangement and the broader CAP arrangement, we find that the latter has a greater density. For the ideas related to M&E found in the general M&E and CAP arrangements it become more difficult to tell which one has greater density. When we look at the general M&E arrangement, there is general support for carrying out and using evaluations and monitoring, in particular in relation to reducing administrative burdens. This idea aligns with ideas found in the broader CAP arrangement on simplification. In the broader CAP arrangement, on the other hand, there is also a dense idea that M&E should not play too great a role in policy-making. Based on the above we formulate the following hypotheses ():

The greater density (authority and specificity) of the institutions of the broader CAP arrangement will grant a key role to member states and thereby to their idea that M&E should play a limited role in CAP policy making.

As a result,

The ideas dimension of the broader EU M&E arrangement, consisting of common (functional) ideas about M&E, will be only loosely integrated in the CAP M&E arrangement. This will lead to a CAP M&E policy that will not be fully (or rather merely rhetorically) in line with common ideas about M&E.

5. Analysis

Below, two change episodes are presented: the process of designing the Common (2013) and the Performance (2021) Monitoring & Evaluation Framework. After presenting each episode, an analysis of the (dimensions of the) CAP M&E policy sub-arrangement follows, with a focus on the impact of the institutions and ideas dimensions of the broader CAP and M&E policy arrangements on this sub-arrangement.

5.1. Common monitoring and evaluation framework (2013)

5.1.1. Policy

The Horizontal Regulation on the Financing, Management and Monitoring of the CAP, which was adopted during the 2013 reform, introduced a common monitoring and evaluation framework (CMEF) for measuring the CAP’s performance. The existing system of monitoring and evaluation for the CAP’s rural development policy thereby became applicable to the CAP as a whole, including the market management and direct payments instruments that cover the bulk of the CAP’s spending. The Horizontal Regulation introduced a specific legal basis for monitoring and evaluating these CAP instruments, evaluations of which had prior been based largely on the Financial Regulation (Interview, May 2019), with a particular focus on financial accountability (Fitzpatrick, Citation2012). Additionally, evaluations were carried out based on specific needs of DG AGRI, evaluation clauses or requests by the European Parliament (Interview, May 2019; COM, Citation2018a). The CMEF also required the Commission to measure and assess the combined performance of the CAP in relation to three common objectives: viable food production; sustainable management of natural resources and climate action; and balanced territorial development. For each objective, different types of indicators were defined, including context-, output-, results-, target- and impact-indicators (COM, Citation2017) . Data for the indicators are largely obtained from the member states, submitted before specific deadlines.

5.1.2. Institutions and ideas

The ‘spill-over’ of the CMEF from its rural policy to the CAP as a whole was initiated by DG Budget and the Commission’s Secretariat-General, which play a role (institution) in coordinating evaluation activities inside the Commission. Since 2010, DG Budget, together with the Secretariat-General, has started to stress the need to assess the CAP’s contribution to the objectives of the so-called Europe2020 strategy (Council, Citation2012a; Interview, May 2019). This required a more comprehensive and systematic evaluation of CAP measures. In addition, they stressed the idea that simplification constituted a necessary approach to drive Europe2020 forward (COM, Citation2012a; Interview, May 2019). Evaluative information could provide the evidence for this.

DG AGRI was receptive to these ideas found in the broader EU M&E policy arrangement. The shift from price support to direct payments to farmers, which was made under the 1992 reform of the CAP, had made agricultural spending more visible, but also led to criticism about lacking public support (Zwaan & Alons, Citation2015). DG AGRI viewed a more comprehensive evaluation framework as a way to increase the accountability of the CAP (COM, Citation2012b, Citation2017).

A fully developed CMEF covering the CAP in its entirety, would also allow for better policy steering (COM, Citation2012b, Citation2017; Interview, May 2019). M&E results were seen by DG AGRI as a key instruments to inform evidence-based decisions, in particular regarding simplifying future policies (COM, Citation2017). The improvement of its policies and simplification had been important interests for both DG Agriculture and the member states. More generally, a comprehensive approach was perceived by DG AGRI as a way to develop a systematic evaluation regime in which the intervention logic of the different instruments of the CAP would play an important role. This was considered important, partly because of existing criticism on the effectiveness and efficiency of individual CAP measures (e.g., by the Court of Auditors) (Interview, May 2019).

5.1.3. Institutions and interests

The ideas to develop a more comprehensive M&E framework overlapped with the ideas and interests of the member states. The Council of Ministers supported the development, as it shared the interest to ensure credibility of the CAP and believed that M&E could contribute to this. At the same time, the Council made clear that administrative burdens should be avoided and that the role of the Commission in implementing/developing the framework should be limited (COM, Citation2012b; Council of the European Union, Citation2012b). Similar views were expressed in the EP Committee on Agriculture (European Parliament, Citation2013). To ‘discuss and assess the overall framework for monitoring and evaluating the CAP … ’ (COM, Citation2012b), an expert group, composed of representatives from each EU country, was established. This became a requirement after the Council amended the Commission’s proposal to develop the CMEF via implementing acts (Council, Citation2012b). One of the expert group’s tasks was to develop a list of indicators. Also, in the expert groups member states expressed concerns about increasing administrative burdens (COM, Citation2012b).

The Commission, in response, emphasized that it would pay attention to the issues of proportionality, simplification and reduction of administrative burdens. Therefore, amongst others changes, it reduced the number of main indicators (COM, Citation2017, Citation2018b) and defined indicators so that the data collection would be based on existing sources, like Eurostat (ibid.; Council, Citation2012b).

5.1.4. Analysis of the M&E arrangement

The episode described above shows that the institutional position of the member states, particular in the expert group, allowed them to translate their ideas and interest to limit administrative burdens to the (policy) design of the monitoring framework. While the broader M&E ideas were generally supported by the Commission and Council and were absorbed in the CAP M&E arrangement, they were compromised when developing the CAP M&E policy. The broader CAP arrangement played an important role here. The institutional dimension of the arrangement, which grants a dominant status to the member states, was, as expected, mirrored, due to its density, in the CAP M&E sub-arrangement. This prevented a further integration and translation of the ideas of the general M&E arrangement in the CAP M&E sub-arrangement.

As a result, there is an incongruence between different dimensions of the M&E sub-arrangement, in particular between the ideas about the need for M&E and the actual CAP M&E policy. This incongruence, as expected, led to various forms of disapproval. The Commission was critical about the implementation and functioning of the CMEF: in its first report on M&E, published in 2018, it noted for example, that there are too many indicators. Also, in the implementation of the framework this incongruence came to the fore with indicators not being available on a yearly basis and/or with delay (COM, Citation2018c). Academics also criticized the indicators of the CMEF (cf. Pe’er et al., Citation2017 on the indicators used for direct payments). The European Court of Auditors (Citation2016), moreover, argued that the CAP’s objectives are difficult to quantify or to set a specific target for , which makes monitoring difficult . Based on a series of special reports, the Court of Auditors (Citation2018) also criticized the reliability of the data used in the M&E framework.

5.2. Performance monitoring and evaluation framework

5.2.1. Policy

In its proposals for a CAP post-2020, the Commission envisioned several modernizations. In particular, it called for a new balance between the responsibilities of the EU and its member states (COM, Citation2017). A new delivery approach would grant more flexibility to member states. In national strategic plans, member states would specify results and targets (which would need approval by the Commission), based on nine common objectives, and make a selection from common interventions (COM, Citation2018e).

Under this model, the CAP would be monitored and evaluated based on the performance of member states’ national plans. This shift would lead to a significant reduction of administrative burdens for CAP beneficiaries (mostly farmers): detailed rules on compliance with specific conditions, checks and penalties would be reduced. Instead, so-called annual performance reports would be reviewed by the Commission. In these reports, output indicators would be used for financial clearance; result indicators would be used to monitor the progress towards the targets set in the national plans (COM, Citation2018d, Citation2018e). In case of a bad performance – i.e. a shortfall of more than 25 per cent of the targets set for the result indicators – the Commission could request the member states to draw up an action plan and possibly withhold payments; in the case of good performance in the field of environment and climate change, by contrast, member states may receive a ‘bonus’ of 5 per cent of their allocated rural development funds for 2027 (Lovec et al., Citation2020). The overall performance of the CAP at the EU level would be evaluated multi-annually (in part also based on impact indicators) (COM, Citation2018e).

The existing CMEF had to be altered in multiple respects to meet this task. While several indicators could be carried over, new indicators were introduced to cover the new objectives of the CAP. In doing so, the Commission also took its experience with and critique about the CMEF into account. An important change was that the existing set of common result indicators was streamlined and reduced (COM, Citation2018b, Citation2018d) based on what was needed to ensure a good management of the national strategic plans (COM, Citation2018d, Citation2018e). To address the experienced problems with (timely) data availability in the previous programming period, indicators would be even more based on pre-existing data (COM, Citation2018e; Interview, 31 January 2020; 4 March 2020). The common indicators were included in the proposal of the so-called Horizontal Regulation on strategic plans. In this proposal, the Commission was given delegated powers to change and add new indicators and further specify the content of the performance framework (COM, Citation2018a).

5.2.2. Interests and ideas

After some initial hesitation, the member states welcomed the new delivery model. The Council underlined the need for simplification and reduction of administrative burdens. Regarding the PMEF it further stressed that indicators should be simple, realistic, easily quantifiable, controllable and applicable to local realities (Council, Citation2018). Similarly, farmers organization Copa-Cogeca (Citation2018) called for reliable and workable indicators. In the expert group, national delegates raised practical concerns about linking indicators with objectives and interventions (COM, Citation2018d; Interview, 31 January 2020), but also about the ability of the proposed result indicators to really measure the CAP's performance, as they do not directly assess the progress against objectives (COM, Citation2018d; see also below). Concerns about the regulatory burden were also addressed ‘politically’ in the Council Working Party (Interview, 4 March 2020). Individual member states in the Council were more vocal, this time, in raising their objections. Especially for states with a decentralized agricultural administration (e.g., France, Spain), a performance review based on many different indicators required much coordination (Interviews, 31 January 2020; 4 March 2020).

Therefore, in January 2020, France, together with Austria, Germany, Ireland and Spain, presented an (informal) alternative list of indicators to be included in the PMEF. Instead of using 38 result indicators as proposed by COM, it proposed to use 27 (also partly alternative) result indicators, of which only 10 core result indicators would be used for the actual performance review. Environmental and climate objectives were hit in particular with a reduction from 21 indicators to 3 core indicators (Council, Citation2020a).

These concerns are partly technical, but are hard to isolate from specific political interests. The type of result indicators used to measure performance affects what interventions will be included in the national strategic plans. The more limited set of result indicators would also make it easier to meet certain targets, by selecting simpler (but less effective) measures to be monitored (Metta, Citation2020). The scope for losing funds, as explicitly stated by the Council Presidency, would thereby be narrowed (Croatian Presidency, Citation2020).

On 21 October 2020, the Council formulated a common position about the proposals, including several amendments regarding the PMEF. As in the case of the CMEF, it limited the delegating powers of the Commission to further develop the PMEF. Moreover, it made several amendments to reduce the number of indicators. A comparison between the Council position and the alternative list of indicators by France shows that most of the suggestions to reduce the number of indicators for the performance reviews were accepted (Council, Citation2020b). The Council further proposed to only have biennial (instead of annual) reviews by the Commission of the country reports and to loosen the shortfall norms related to the action plans (Council, Citation2021). The EP made similar suggestions. Next to that, it also proposed to leave more room to justify shortfalls and execute an action plan before any withholding of payments (Council, Citation2021; European Parliament, Citation2020). During the trilogues, the possible financial sanction for bad performance was dropped altogether (Council, Citation2021).

5.2.3. Analysis of the M&E arrangement

The watering down of the performance review and indicators was widely criticized by NGOs and academics (e.g., Metta et al., Citation2020). A main point of critique concerned the use of result-indicators to measure performance, as most of these indicators only indicate the uptake of certain schemes (Nyssens, Citation2020; Pe’er et al., Citation2019; Interviews, 31 January 2020; 4 March 2020). More generally, the Court of Auditors (Citation2018) stressed that the objectives must be more clearly linked to outputs, results and impacts. Related to this, scientists criticized that the Commission proposal lacked quantifiable objectives or results (e.g., Maréchal et al., Citation2018). The lack of targets at the EU level, according to the Court of Auditors (Citation2018), means that achievement of EU objectives cannot be measured and creates uncertainty about how the Commission will assess the targets set in the strategic plans.

The critique on the monitoring framework, again, exposes the internal incongruence of the CAP M&E sub-arrangement. Similar to the CMEF, there is a clear tension between a core idea behind the PMEF (increasing the CAP’s performance based on information about its factual results) and the actual policy design of the monitoring framework (in which performance is only assessed in a limited way). Also in this case, the institutional position of the Council as co-legislator made it possible to water down the CAP M&E policy because of ideas and interests of the member states to limit administrative burdens and remain in control over the content of national plans.

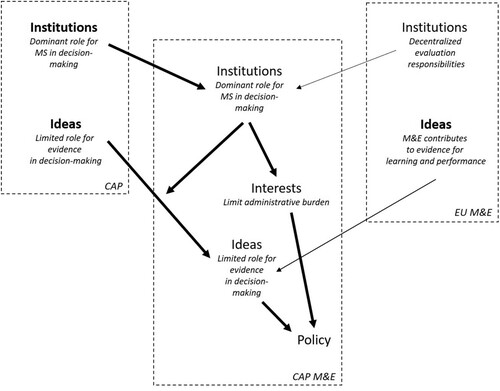

5.3. Analysing changes in the CAP M&E arrangement over time

An analysis of the two changes in the CAP M&E arrangement shows that several ideas about the usefulness of monitoring and evaluation found in the general EU M&E arrangement were integrated in the CAP M&E sub-arrangement. Moreover, these ideas led to a change in policy instruments. In part, this change can be explained by the fact that the general M&E ideas dovetailed with the interest of DG AGRI and most member states to improve the credibility of the CAP and to reduce administrative burdens. Another dimension of the broader existing CAP arrangement, however, prevented a full translation of these ideas into policy. While the institutional position of the Commission as initiator of legislation made it possible to introduce a CMEF in 2013 and a PMEF in 2021, institutions also granted a prominent role to the Council / member states in the decision-making process. In the design of the M&E policies, member states had a considerable direct influence as co-legislator and by being represented in an expert group. This allowed them to affect choices for specific indicators and data to monitor and evaluate the CAP.

Member states’ choices were affected by technical concerns, but also by an interests to limit additional burdens for administrations and farmers. This played a clear role during the design of both the CMEF and the PMEF. During the design of the PMEF, concerns about losing funding when certain results would not be achieved also played a role. The linking of penalties and rewards to performance increased the political stakes of the design of the monitoring framework. This led to a situation in which the ideas about monitoring and evaluation (in terms of evidence-based policy making and accountability) were not fully translated in a CAP M&E policy framework. These findings are summarized in below.

6. Discussion and conclusion

This study has shed light on the development of the M&E framework of the Common Agricultural Policy during its last two major reforms. Specifically, we asked the question to what extent the CAP M&E policy sub-arrangement has integrated dimensions of the ‘general’ EU M&E policy arrangement and how this degree of integration can be explained by its embeddedness in the broader CAP policy arrangement.

Based on our analysis we can conclude that while the general EU M&E arrangement has influenced the CAP M&E sub-arrangement, its influence has been limited: whereas some of its ideas have been incorporated, and policy changes took place, the translation of these ideas into policies was incomplete. Both the institutions and ideas dimensions of the general CAP arrangement turned out to have high density. In line with other analyses of the CAP, we see that especially the existing institutions of the broader CAP arrangement ‘reinforced the existing policy subsystem rather than opening it up to new influences and ideas’ (Greer, Citation2017).

Eventually, this granted room for member states (and their ideas and interests) to make several substantial adjustment to the CAP M&E framework. The limitation of indicators, the reduced frequency of reviews by the Commission, as well as the removal of possible sanctions and incentives make it less likely that the Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Framework will contribute to the performance of the CAP as originally planned and as espoused in the policy ideas.

While the CAP M&E arrangement introduces some new elements, it does so in a minimal way. Based on that we can speak of shallow post-exceptionalism in the case of this sub-arrangement. Given the incongruence of the policy and ideas dimension, the sub-arrangement can also be described as tense arrangement. Our study already showed that this has led to criticism during the developments of the M&E frameworks. Given the expected more limited contribution of the PMEF to the CAP’s performance, it is likely that this criticism will continue.

Further research is needed to tell if the density of the general CAP arrangement is also greater than that of other policy arrangements that possible affect other CAP sub-arrangements (e.g., for Research and Development or Rural Development).

Applying a policy arrangement approach can be useful for this further research, allowing for analysing different dimensions of policies and the interaction between them. Applying the approach allows for a detailed as well as dynamic understanding and explanation of stability and change in policies.

In analysing the (post-) exceptionalism of the CAP it seems important to not only focus on policies, but also consider their implementation. In this article we very briefly touched upon the implementation of the CMEF, showing that little priority is sometimes being given to the actual collection and delivery of data. We believe that tensions between ideas and policy (found in tense post-exceptionalist arrangements) are very likely to come to the fore as well in the implementation stage. Turning to this stage in further research can therefore be helpful in broadening our understanding of (post-)exceptionalism..

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pieter Zwaan

Dr Pieter Zwaan is assistant professor at the department of Public Administration at Radboud University. His research focusses on (EU) policy implementation and evaluation (usage) in multi-level settings.

Gerry Alons

Dr Gerry Alons is associate professor at the department of Political Science at Radboud University. Her research focuses on global food and agricultural policies from a political economy and public policy perspective.

Stijn van Voorst

Dr Stijn van Voorst is assistant professor at the department of Public Administration at Radboud University. His research focusses on the evaluation of EU policies.

References

- Alons, G. (2017). Environmental policy integration in the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy: Greening or greenwashing? Journal of European Public Policy, 24(11), 1604–1622. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1334085

- Alons, G., & Zwaan, P. (in press). The common agricultural policy: Still the elephant in the room? In S. Faure & C. Lequesne (Eds.), Elgar Companion to the European Union. Elgar.

- Arts, B., Leroy, P., & Van Tatenhove, J. (2006). Political modernisation and policy arrangements: A framework for understanding environmental policy change. Public Organization Review, 6(2), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-006-0001-4

- Badampudi, D., Wohlin, C., & Petersen, K. (2015). Experiences from using snowballing and database searches in systematic literature studies. In Proceedings of the 19th international conference on evaluation and assessment in software engineering (pp. 1–10). https://doi.org/10.1145/2745802.2745818

- Beijen, B. A., Van Rijswick, H., & Anker, H. (2014). The importance of monitoring for the effectiveness of environmental directives: A comparison of monitoring obligations in European environmental directives. Utrecht Law Review, 10(2).

- Bovens, M., ‘t Hart, P., & Kuipers, S. (2008). The politics of policy evaluation. In R. E. Goodin, M. Rein, & M. Moran (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy (pp. 320–335). Oxford University Press.

- Bozzini, E., & Hunt, J. (2015). Bringing evaluation into the policy cycle CAP cross compliance and the defining and re-defining of objectives and indicators. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 6(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1867299X00004281

- COM (European Commission). (2012a). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A simplification agenda for the MFF 2014-2020. COM/2012/042 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52012DC0042

- COM (European Commission). (2012b). Report of the first meeting of the expert group on ‘monitoring and evaluating the cap’ – 14 June 2012 In Brussels.

- COM (European Commission). (2015). Better regulation toolbox [complement to SWD(2015)111]. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/better-regulation-toolbox-2015_0.pdf

- COM (European Commission). (2017). Technical handbook on the CMEF of the CAP 2014–20.

- COM (European Commission). (2018a). Staff working document impact assessment. SWD/2018/301 final – 2018/0216 (COD). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=SWD%3A2018%3A301%3AFIN

- COM (European Commission). (2018b). Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing rules on support for strategic plans to be drawn up by Member States under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and repealing Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council COM/2018/392 final - 2018/0216 (COD), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2018%3A392%3AFIN

- COM (European Commission). (2018c). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the implementation of the Common Monitoring and Evaluation Framework and first results on the performance of the Common Agricultural Policy. COM(2018)790 final. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/fe3c8f74-f894-11e8-9982-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-search

- COM (European Commission). (2018d). Minutes of the 13th meeting of the expert group for monitoring and evaluating the CAP – 12 March 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/expert-groups-register/screen/meetings/consult?lang=en&meetingId=2042&fromExpertGroups=true

- COM (European Commission). (2018e). Minutes of the 14th meeting of the expert group for monitoring and evaluating the CAP – 19 September 2018 https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/expert-groups-register/screen/meetings/consult?lang=en&meetingId=4759&fromExpertGroups=true

- Copa-Cogeca. (2018). Copa and Cogeca position on the CAP post 2020. https://www.copa-cogeca.eu/Download.ashx?ID=1900725&fmt=pdf

- Council of the European Union. (2012a). Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the financing, management and monitoring of the Common Agricultural Policy – working document from the Commission services.

- Council of the European Union. (2012b). Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the financing, management and monitoring of the Common Agricultural Policy (the horizontal regulation) – Presidency consolidated revised text.

- Council of the European Union. (2018). Communication on ‘the future of food and farming’ – presidency conclusions https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7324-2018-INIT/en/pdf_

- Council of the European Union. (2020a). Proposal for a regulation on CAP strategic plans (Annex I) – Drafting suggestions from five delegations. (Internal document).

- Council of the European Union. (2020b). Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing rules on support for strategic plans to be drawn up by Member States under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP strategic plans) and financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and repealing regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council and regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council – general approach. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-12148-2020-ADD-1/en/pdf

- Council of the European Union. (2021). Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing rules on support for strategic plans to be drawn up by Member States under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and repealing regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council and regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council – four column document. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-6129-2021-INIT/en/pdf

- Court of Auditors. (2016). Special report is the Commission’s system for performance measurement in relation to farmers’ incomes well designed and based on sound data? https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR16_01/SR_FARMERS_EN.pdf

- Court of Auditors. (2018). Opinion No 7/2018 (pursuant to Article 322(1)(a) TFEU) concerning Commission proposals for regulations relating to the Common Agricultural Policy for the post-2020 period (COM(2018) 392, 393 and 394 final) (2019/C 41/01). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018AA0007&rid=1

- Croatian Presidency. (2020). Untitled memo. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/44646/hr-pres-progress-report-final-16-06-20.pdf

- Daugbjerg, C., & Feindt, P. H. (2017). Post-exceptionalism in public policy: Transforming food and agricultural policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(11), 1565–1584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1334081

- Eckhard, S., & Jankauskas, V. (2019). The politics of evaluation in international organizations: A comparative study of stakeholder influence potential. Evaluation, 25(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389018803967

- European Parliament. (2013). Report on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the financing, management and monitoring of the Common Agricultural Policy (COM(2011)0628 – C7-0341/2011 – COM(2012)0551 – C7-0312/2012 – 2011/0288(COD)).

- European Parliament. (2020). Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 23 October 2020 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the financing, management and monitoring of the Common Agricultural Policy and repealing regulation (EU) No 1306/2013 (COM(2018)0393 - C8-0247/2018 – 2018/0217(COD))(2). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0288_EN.html

- European Parliament, Council & Commission. (2016). Interinstitutional agreement on better law-making. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016Q0512%2801%29

- Fitzpatrick, T. (2012). Evaluating legislation: An alternative approach for evaluating EU internal market and services law. Evaluation, 18(4), 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012460439

- Greer, A. (2017). Post-exceptional politics in agriculture: an examination of the 2013 CAP reform. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(11), 1585–1603.

- Hansen, H. F. (2005). Choosing evaluation models: A discussion on evaluation design. Evaluation, 11(4), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389005060265

- Hart, K. (2015). The fate of green direct payments in the CAP reform negotiations. In J. Swinnen (Ed.), The political economy of the 2014-2020 reforms of the common agricultural policy: An imperfect Storm, Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies/Rowman and Littlefield International (pp. 245–276).

- Højlund, S. (2014). Evaluation use in evaluation systems – the case of the European commission. Evaluation, 20(4), 428–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389014550562

- Knops, L., & Swinnen, J. (2014). The first CAP reform under the ordinary legislative procedure: A political economy perspective. Study commissioned by the European Parliament, Directorate General for internal policies, Policy department B, Structural and cohesion policies.

- Liefferink, D. (2006). The dynamics of policy arrangements: Turning round the tetrahedron. In B. J. M. Arts & P. Leroy (Eds.), Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance (pp. 45–68). Springer.

- Lovec, M., Šumrada, T., & Erjavec, E. (2020). New CAP delivery model, Old issues. Intereconomics, 55(2), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-020-0880-6

- Maréchal, A., Baldock, D., Erjavec, E., Juvančič, L., Rac, I., Dwyer, J., & Hart, K. (2018). Towards a step change for enhanced delivery of environmental and social benefits from EU farming and forestry. EuroChoices, 17(3), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692X.12185

- Metta, M. (2020, November 17). CAP performance monitoring and evaluation framework – EP position. https://www.arc2020.eu/cap-performance-monitoring-and-evaluation-framework-ep-position

- Metta, M., Wetzel, H., & Armijo Campos, R. M. (2020). CAP strategic plans project CAP reform post 2020: Lost in Ambition? (Report). ARC2020. https://www.arc2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/ARC_Strategic_Plans_2020_web_version_compressed_final.pdf

- Moulton, S., & Sandfort, J. R. (2017). The strategic action field framework for policy implementation research. Policy Studies Journal, 45(1), 144–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12147

- Nyssens, C. (2020, July 9). The European Commission must not greenwash the Common Agricultural Policy. https://capreform.eu/the-european-commission-must-not-greenwash-the-common-agricultural-policy/

- OECD. (2020). How Can Governments Leverage Policy Evaluation to Improve Evidence Informed Policy Making? Highlights from an OECD Comparative Study.

- Ostrom, E., Cox, M., & Schlager, E. (2014). An assessment of the institutional analysis and development framework and introduction of the social-ecological systems framework. In P. A. Sabatier & C. Weible (Eds.), Theories of the policy process (pp. 267–306). Westview Press.

- LSE GV314 Group & Page, E. C. (2014). Evaluation under contract: Government pressure and the production of policy research. Public Administration, 92(1), 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12055

- Pe’er, G., Lakner, S., Müller, R., Passoni, G., Bontzorlos, V., Clough, D., Moreira, F., Azam, C., Berger, J., Bezak, P., Bonn, A., Hansjürgens, B., Hartmann, L., Kleemann, J., Lomba, A., Sahrbacher, A., Schindler, S., Schleyer, C., Schmidt, J., … Zinngrebe, Y. (2017). Is the CAP fit for Purpose? An evidence-based fitness check assessment. German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research.

- Pe’er, G., Zinngrebe, Y., Moreira, F., Sirami, C., Schindler, S., Müller, R., Bontzorlos, V., Clough, D., Bezák, P., Bonn, A., Jürgens, B. H., Lomba, A., Möckel, S., Passoni, G., Schleyer, C., Schmidt, J., & Lakner, S. (2019). A greener path for the EU Common Agricultural Policy. Science, 365(6452), 449–451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax3146

- REFIT platform. (2016). Opinion on the submission by the European Environmental Bureau on Effectiveness and Efficiency of the Common Agricultural Policy. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/opinion_agriculture_i_4a_final.pdf

- Sanderson, I. (2002). Evaluation, policy learning and evidence-based policy making. Public Administration, 80(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00292

- Sandfort, J., & Moulton, S. (2015). Effective Implementation in Practice: Integrating Public Policy and Management. John Wiley & Sons.

- Schwartz, R. (1998). The politics of evaluation reconsidered: A comparative study of Israeli programs. Evaluation, 4(3), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/13563899822208617

- Smith, M. (1992). The agricultural policy network: Maintaining a closed relationship. In R. Rhodes & D. Marsh (Eds.), Policy Networks in British Government (pp. 27–55). Clarendon Press.

- Stephenson, P. (2015). Reconciling audit and evaluation?: The shift to performance and effectiveness at the European Court of Auditors. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 6(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1867299X0000430X

- Stern, E. (2009). Evaluation policy in the European Union and its institutions. In W. M. K. Trochim, M. M. Mark, & L. J. Cooksy (Eds.), Evaluation Policy and Evaluation Practice: New Directions for Evaluation (pp. 67–85). Jossey-Bass.

- Trochim, W. M. K. (2009). Evaluation policy and evaluation practice. In W. M. K. Trochim, M. M. Mark, & L. J. Cooksy (Eds.), Evaluation policy and evaluation practice: New directions for evaluation (pp. 13–32). Jossey-Bass.

- Vedung, E. (1997). Public policy and program evaluation. Transaction.

- Voorst, S., Zwaan, P., & Schoenefeld, J. (in press). Policy evaluation: An evolving and expanding feature of EU governance. In P. R. Graziano & J. Tosun (Eds.), Elgar encyclopedia of European Union public policy.

- Weiss, C. H. (1993). Where politics and evaluation research meet. Evaluation Practice, 14(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/109821409301400119

- Wergin, J. F. (1976). The evaluation of organizational policy making: A political model. Review of Educational Research, 46(1), 75–115. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543046001075

- Zwaan, P., & Alons, G. (2015). Legitimating the CAP: The European commission’s discursive strategies for regaining support for direct payments. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 11(2).