ABSTRACT

European integration has led to the proliferation of cross-border mobilities across the member states of the European Union (EU). How do cross-border virtual and physical interactions impact different types of redistributive solidarity? In this article, we test the association between transnationalism and support for foreigners’ access to the domestic welfare state and to general redistributive solidarity to reduce inequality. We draw on original public opinion survey data collected by the ‘Reconciling Economic and Social Europe: The Role of Values, Ideas and Politics’ (REScEU) research project in ten EU countries. We argue that European forms of transnationalism increase mobility-related solidarity because through cross-border social exchange individuals develop feelings of care and responsibility towards ethnic ‘others’. We find that transnationalism has a positive effect on the acceptance of both ‘EU citizens’ and ‘all foreigners’ into the domestic welfare system. By contrast, transnationalism is associated with a decrease in individuals’ preferences for economic redistribution to reduce income inequality in one’s country.

Introduction

European integration contributes to the proliferation of cross-border mobilities across European Union (EU) member states. These mobilities range from forms of permanent settlement in another member state to circular migrations and short-term visits. But EU citizens do not need to physically migrate to lead more transnational lives: they can engage in virtual mobilities, maintain transnational contacts, and acquire intercultural competences (Mau et al., Citation2008). How do such bourgeoning cross-border interactions impact European societies? Thinking about this question goes back to the work of Karl Deutsch and colleagues, who viewed intensifying cross-border transactions as the social basis of supranational integration (Deutsch et al., Citation1957). In later years, a niche literature has developed, linking individual transnationalism to attitudes and behaviours that are conducive to EU polity building (e.g., Recchi & Favell, Citation2019). This includes, among others, support for European integration (Kuhn, Citation2015), increased levels of supranational political engagement (Kyriazi & Visconti, Citation2021) and support for economic risk sharing at the member-state level (Ciornei & Recchi, Citation2017).

Here we focus on the link between transnationalism and redistributive solidarity, which has become an area of utmost concern in both political debates and academic research related to the EU (e.g., Gerhards et al., Citation2019; Lahusen, Citation2020; Lahusen & Grasso, Citation2018). Even though there are many definitions and forms of solidarity, we limit ourselves to examining individual attitudes towards welfare and redistribution at the national level (as opposed to examining redistributive solidarity with respect to the EU, like Ignácz (Citation2021) and Reinl (Citation2022)). We do so by distinguishing between two types of redistributive solidarity: one specifically related to mobility (the degree to which individual transnationalism is associated with support for foreigners’ access to welfare in the receiving state) and one generally related to welfare provision (support for state measures to reduce income inequality domestically). Our aim is to take a snapshot of the way in which the trasnationalization of people’s lives links to systems of loyalty and social sharing historically built on national closure (Ferrera, Citation2009, p. 219). While individual transnationalism, itself the product of opening, could play a crucial role in boosting forms of solidarity that are also boundary-transcending (see Pellegata & Visconti, Citation2021), more traditional forms of redistributive solidarity could be left unaffected by it.

We begin by probing whether individual transnationalism is associated with support for newcomers’ access to the welfare state in the receiving country. We distinguish between two categories, ‘EU citizens’ on the one hand and ‘all foreigners’ on the other hand. A cornerstone of European integration is the right of EU citizens to freely move to and live in any member state. Yet, intra-EU mobility has been met with flares of restrictionism and welfare chauvinism in some countries, mainly those at the receiving end of mobility. Transnationalism, we think, boosts this dimension of mobility-related solidarity: social exchange that spans the borders of the EU’s member states promotes a sense of commonality with people of different backgrounds and reduces perceptions of threat and competition between them. Transnational interactions are conducive, if not to thicker forms of collective identity, to a modicum of fellow feeling that can sustain redistributive solidarity. While we expect a positive association between individual transnationalism and redistributive solidarity towards EU citizens, we leave it as an open question whether it extends to all foreigners legally residing in one’s country.

We then raise a further question: does the effect of individual transnationalism vary by type of solidarity, i.e., between mobility-related forms and general redistributive solidarity? By the latter, we mean support for or opposition to solidarity which does not implicate in obvious ways ethnic diversity. More specifically, we examine the association of individual transnationalism with levels of support for government measures to reduce income inequality at the national level. This benchmarking exercise allows us to clarify whether transnational individuals are simply more solidaristic than others in general or whether other dynamics of boundary drawing are at work.

To answer these questions, we use data obtained from an original public opinion survey collected by the REScEU project in 2019 in 10 EU countries (Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Hungary, Poland, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden) (Donati et al., Citation2021). We find that individual transnationalism does indeed foster mobility-related solidarity: it has a positive effect on the acceptance of foreigners into the domestic welfare system, regardless of whether they are EU citizens or not. On the flip side, we find a negative association between individual transnationalism and general redistributive solidarity. Bearing in mind the limitations of our cross-sectional data, this result suggests that individual transnationalism does not foster any type of solidarity but that it can specifically boost those forms that resonate with the transnational experience.

Drawing the circles of solidarity: literature review and hypotheses

Redistributive solidarity in the era of globalization

Solidarity denotes a set of attitudes and predispositions that lead to actions benefitting others; it can also refer to the institutions that transfer resources from some people to others (van Parijs, Citation2017, p. 421). In the European context, solidarity has been built around the idea of fiscal redistribution (Ciornei & Recchi, Citation2017, p. 469). In this study, we borrow a working definition from Banting and Kymlicka (Citation2017, p. 4) who take redistributive solidarity to mean support for redistribution towards the poor and vulnerable groups, with the aim of reducing social inequality as well as support for full access of people of all backgrounds to social programmes. On this account, redistributive solidarity has at least two prongs, with one being squarely aimed at reducing social inequality and the other being access to the welfare state.Footnote1 The first aspect refers to a specific welfare arrangement typical of social democratic welfare regimes, that is redistribution to reduce income inequality (equality principle). The second aspect of solidarity relates instead to who should be entitled to social security benefits, and here we consider support for foreigners’ ability to access social programmes, be they EU citizens or legal foreign residents.

Solidaristic attitudes embody the mutual concern and obligation that members of a society have, and therefore typically appeal to some image of a decent society (Banting & Kymlicka, Citation2017, p. 6). It is, then, important to distinguish solidarity from charity: solidarity goes beyond a humanitarian concern with the suffering of others and aims at social justice; as such, it is rooted in an ‘ethic of membership’ (Banting & Kymlicka, Citation2017, p. 6). People’s memberships, in turn, are organized in different ways (e.g., class, ethnicity, religion), but the most consequential of these has been the ‘nation’ (Banting & Kymlicka, Citation2017). Historically, national citizenship represented a ‘quantum leap in the stabilization and generalization of social cooperation’ (Ferrera, Citation2005, p. 24), for national identity came to signify collective responsibility that provided a strong justification for limiting social inequality (Miller, Citation1995). From the twentieth century onwards, the nation-state became entrenched as the primary frame of reference for solidarity (Stjernø, Citation2009). The mode and degree of solidarity have been very much subject to political conflict and debate along the lines of political ideology, but despite these contestations, the national ‘container’ remains the taken-for-granted site of institutionalized solidarity.

Globalization, and its European variant, EU integration, have been gradually shifting the spatial organization of social relations and interactions. The expansion of international markets and the free flow of capital, goods, services, and people sit uneasily with the idea of nationally based solidarity (Stjernø, Citation2009). In this context, a booming literature seeks to assess the emergence, or lack thereof, of solidaristic attitudes in the EU multi-level polity, by distinguishing between different forms of solidarity (fiscal, territorial, welfare, refugee solidarity) (Gerhards et al., Citation2019) or by richly contextualized country case studies (Lahusen & Grasso, Citation2018), among others. In the field of welfare, for quite some time now, scholars have talked about the challenge of reconciling ‘solidarity’ with ‘Europe’ exactly because European integration confronts the established territorial basis of existing (nationally organized) systems of social protection (Ferrera, Citation2005). Indeed, the greatest anxiety about the erosion of national solidarity in the face of diversity arises in the field of redistribution (Banting & Kymlicka, Citation2017, p. 10; see also Crepaz, Citation2008).

Increasing spatial mobility is a key factor that is thought to have ‘weakened the social ties that bind individuals to traditional social strata’, along with the decline of religiosity, and the diversification of the world of work and occupational mobility (Marks et al., Citation2021, p. 174). This transformation has led to the emergence of a historically novel, predominantly cultural divide, pitting ‘those who defend national ways of life from external influence against those who conceive their identities as consistent with international governance and who welcome, rather than oppose, the dense interpenetration of societies’ (Marks et al., Citation2021, p. 176; see also Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018). The new cleavage increasingly shapes political competition (Kriesi et al., Citation2006) and polarizes public opinion, especially on the (often linked) issues of immigration and EU integration (De Vries, Citation2018; De Wilde, Citation2019). The extent to which individuals’ lives extend across national borders is key in structuring this divide: the more one is able and willing to accept the transnationalization of their realm, the more one tends to support EU integration and its various dimensions (Kuhn, Citation2015), including forms of solidarity that also span national borders (Ciornei & Recchi, Citation2017).

Individual transnationalism and types of redistributive solidarity

Early theorists of EU integration posited that increasing transnational transactions would provide the social basis for the emergent EU polity (Deutsch et al., Citation1957). As individuals engage across borders, cognitive stances shift towards more open and tolerant perceptions of people of different backgrounds. Consequently, through increasing interaction/transaction, attitudes become more inclusive, and solidarity is extended to non-national ‘others’ as people to whom protection, equality, and inclusion are owed (Mau et al., Citation2008). In parallel, transnational transactions create and reinforce specific interests, which also work towards supporting the inclusion of foreigners in national welfare systems. Given the social stratification of transnationalism, transnational individuals tend to have higher educational attainment and occupational status (Kuhn, Citation2019), which are both, in turn, associated with a decrease in welfare-chauvinistic attitudes (Ziller & Careja, Citation2022). At the same time, transnational individuals are also more likely than the general population to benefit from welfare arrangements that are, at least in part, detached from national citizenship. This is not only because transnational individuals may have been, or expect to be in the future, on the receiving side of redistributive solidarity in a state other than the state of their origin but also because they are more likely to have people in their households or social networks in such a situation. Thus, both because of inclusive identification and expected benefits, they are likelier to perceive the need for forms of mobility-related solidarity, which makes us anticipate a positive association between individual transnationalism and mobility-related redistributive solidarity.

Is the positive effect of transnationalism on mobility-related solidarity confined only to EU citizens, or does it also extend to all foreigners? On the one hand, it is plausible that individual transnationalism is positively linked to solidarity with EU citizens only but not with foreigners more generally (H1a). Why would we expect this ‘solidarity bias’ towards EU citizens? First, on average intra-EU freedom of movement tends to be more popular among the general public than immigration in EU member states (European Parliament, Citation2016). Second, it is thought that transnationalism gives rise to regionally confined patterns of social interaction: connections are not established on a global scale but rather between one or more national societies, giving shape to (weakly) bound social spaces where allegiances and identifications sediment (Mau et al., Citation2008, p. 3). On the other hand, individual transnationalism could be positively linked to solidarity with both EU citizens and all foreigners (H1b). Going back to classic contact theory (Allport, Citation1954), it is in fact quite plausible that the boundaries of solidarity extend to include all foreigners legally resident in one’s country regardless of their citizenship. The social mechanism that leads to improved intergroup relations, i.e., extensive contact, seems rather independent from people’s formal legal status. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study systematically examines whether people in general and transnational individuals in particular distinguish between EU citizens versus all foreigners as recipients of solidarity, and therefore formulating two competing hypotheses seems to be the most appropriate strategy.

We then perform an additional analysis which seeks to provide further evidence that transnational background, experiences, and competences are conducive to forms of solidarity that also transcend national borders and not redistributive solidarity in general.Footnote2 In order to investigate the relative effect of transnationalism on support for mobility-related solidarity, we contrast our results regarding mobility-related solidarity with a measure of general redistributive solidarity, namely support for ‘state measures to reduce differences in income levels in one’s country’. While income inequality and migration status can, of course, be interrelated, this item does not explicitly tap into migration-related heuristics but evokes the classic left-right divide regarding redistribution. Specifically, we hypothesize that there is no link between individual transnationalism and general redistributive solidarity (H2). Personal background, activities, and cultural competences that cut across national borders all contribute to the formation of values, identifications, and interests that favour the expansion of solidarity beyond the nation but do not affect in obvious ways attitudes about national redistributive solidarity. While we have good reasons to believe that individual transnationalism structures opinions on non-economic or cultural issues, such as migrants’ access to welfare, this shall not be the case for state redistribution, which is a traditional socioeconomic issue. Given that the socioeconomic dimension and the sociocultural dimension in political conflict are thought to be orthogonal and therefore largely independent from each other (De Wilde, Citation2019; Kriesi et al., Citation2006), this would imply that individual transnationalism and general redistributive solidarity are unrelated.

Conversely, we do expect that the different types of solidarities are related. More specifically, we hypothesise a positive relationship between general redistributive solidarity and support for EU citizens’/all foreigners’ access to welfare (H3). We assume a congruence between citizens’ general welfare attitudes and their support for specific policies related to EU citizens/foreigners since both policies ultimately seek to achieve social justice. Studies show that people tend to have a stable set of orientations towards political ideals like equality and autonomy that are translated into more specific attitudes towards political and social issues (Kulin & Svallfors, Citation2013; see also Ciornei & Recchi, Citation2017). Cue-taking theory points to a different plausible mechanism linking attitudes towards national welfare and the EU’s social dimension (for a discussion and application, see Baute et al., Citation2019). In a nutshell, this assumes that because most citizens have limited knowledge of and interest in European policies, they rely on their attitudes towards domestic politics as a proxy to evaluate EU integration. In our case, opinions about national redistribution provide a heuristic with which to evaluate whether EU migrants and/or foreigners should be granted access to welfare. To flesh out this relationship, we model preferences over general redistribution as an antecedent of support for mobility-related solidarities (see below). This way we can simultaneously detect the effect of individual transnationalism on general redistributive solidarity and how the latter feeds into mobility-related solidarities.

Data and methods

Our empirical analyses rely on an original mass survey conducted by the University of Milan, in the framework of the REScEU project fielded in ten EU member states (Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Hungary, Poland, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden) between June and July 2019. This set includes member states from across Europe’s geographic areas, having different welfare state regimes as well as levels of emigration and immigration. The responses were collected using the computer-aided web interviewing (CAWI) method on a sample of 15,149 respondents. The sample was stratified on age, gender, education, and area of residence (see the Online Appendix for more details about the survey).

Dependent variables

We operationalize mobility-related solidarity as acceptance of or opposition to the idea that non-citizen residents should receive the same social security benefits as nationals. We use two items that measure agreement on a 4-point Likert scale on statements distinguishing between the different receivers of solidarity, worded as follows:

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about freedom of movement of citizens and services? EU citizens who reside in (COUNTRY) should receive the same social security benefits as (NATIONALITY); All foreigners legally residents in (COUNTRY) should receive the same social security benefits as (NATIONALITY).

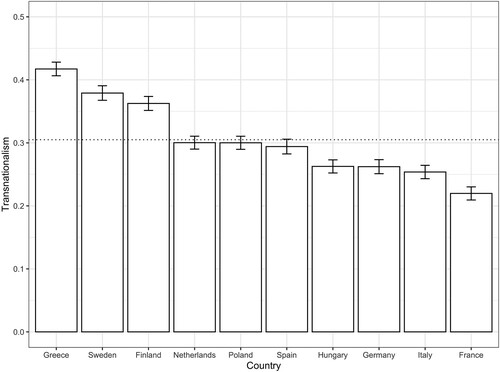

reports the distributions of support for the three solidarity questions for each country in our sample. To ease the visual presentation, all three variables have been recoded into binary variables (see the note below the figure for more details). Across the ten EU member states considered, most respondents are somewhat or strongly in favour of opening the welfare system to both EU citizens and all foreigners. Greater support for mobility-related redistributive solidarity is found in Southern and Eastern European countries compared to Northern ones. In Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden, we find greater support for letting all foreigners access the national welfare system rather than only EU citizens. Conversely, in Greece and Hungary, the opposite is true, which suggests that it is relevant whether a member state is predominantly on the receiving or sending end of intra-EU mobility. In the remaining countries, there is no significant difference (at p < 0.05) between the two response categories. Most respondents also favour redistribution. The highest level of support is observed in Hungary and the lowest in Finland – which is the only country with most respondents against government redistribution to reduce inequality. Comparing general redistributive solidarity to the mobility-related variants, support for the former is higher only in Hungary and Germany.

Figure 1. Support for different types of solidarity in ten EU countries.

Notes: The figure reports the share of respondents agreeing with solidarities with 95% C. I., ordered by support for general redistributive solidarity and computed with post-stratification weights. The variables were recoded into binary variables to ease presentation. Mobility-related solidarities were coded 0 for answers ‘Somewhat disagree’ and ‘Strongly disagree’ and as 1 for ‘Somewhat agree’ and ‘Strongly agree’; redistribution as 0 (Against redistribution/Neutral) if answers ranged between 5 and 10 and as 1 if they ranged between 0 and 4 (In favour). Source: REScEU survey.

Explanatory variable

Our main independent variable is an index of individual transnationalism, based on a set of dichotomous variables. We define transnationalism drawing on Mau et al. (Citation2008, p. 2) as ‘the extent to which individuals are involved in cross-border interaction and mobility’. We used 14 items included in our survey to construct the composite index (see also Delhey et al., Citation2015; Kuhn, Citation2015; Kyriazi & Visconti, Citation2021 for similar strategies). As summarized in , we distinguish between four different dimensions. Transnational background refers to the respondents’ citizenship if multiple and/or different from the country of interview. This dimension also includes having close relatives (partner or parent) born in another EU member state. We also include the experience of physical mobility as well as having transnational social contacts. Finally, we measure intercultural competence, which comprises patterns of cultural consumption. Given that a prerequisite for most forms of transnational practice is knowledge of a foreign language, we also include foreign language competence in this category.

Table 1. Operationalization of individual transnationalism in EU10 countries.

We specifically examine an EU variant of transnationalism because we are interested in solidarity-building within a given sociopolitical unit rather than anywhere in the world. The transnationalism index captures very different forms of mobilities, virtual and physical, short versus long term (Salamońska & Recchi, Citation2016 provide a useful survey of patterns and intersections). We appreciate that different components may have different effects, but this falls outside the scope of the present examination.

To make up our transnationalism index, we ran a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the 14 items listed in . The results of the CFA (see the Online Appendix Table F) show that a unidimensional model of transnationalism is adequate to capture citizens’ cross-border experiences. This configuration returned significant coefficients for all items in each country. Thus, to measure citizens’ transnationalism, we predicted respondents’ position on the latent construct. The factor score was rescaled from 0 to 1, with low (high) scores indicating low (high) transnationalism.

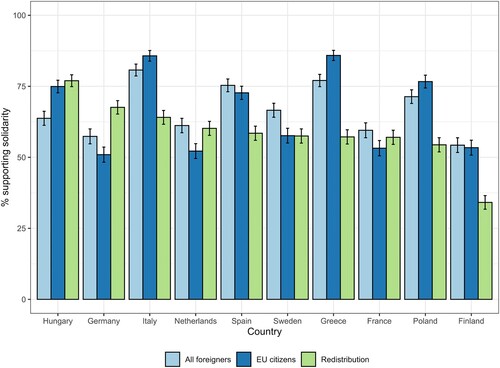

displays the average transnationalism level for each country included in the survey, rescaled to vary between 0 and 1. It is lowest in France and Italy and highest in Greece, Sweden, and Finland.

Control variables

We controlled for the impact of transnationalism on the various forms of solidarity by including alternative explanatory factors in the empirical models.Footnote3 As redistributive solidarity generally finds strong support among the political left, while welfare-chauvinistic attitudes are more dominant on the right, we control for political ideology using respondents’ self-placement on the left-right axis. Our model also includes a conventional measure of general EU support: the preference for more (or less) EU integration. Next, we control for self-identification given that the degree to which one identifies as (also) European has been linked to positive attitudes towards various dimensions of EU integration, including EU solidarity, while strongly identifying with one’s own country is highly predictive of welfare-chauvinistic attitudes (Ciornei & Recchi, Citation2017; Lahusen & Grasso, Citation2018; van der Waal et al., Citation2010; Verhaegen, Citation2018).

Studies also find that experiencing economic hardship mitigates European identity and support for solidarity (Verhaegen, Citation2018), so one’s material circumstances have also to be taken into consideration. Accordingly, we control for education, occupation, and subjective material deprivation. The latter is conceptualized with a standard item asking respondents about the extent to which they find it (very) difficult to cope on household (HH) income. As usual, we control for age, given that older people tend to rely more on national welfare as well as have more conservative social attitudes relating to migration (Schotte & Winkler, Citation2018), both of which lead us to expect support for redistributive solidarity but reduced support for mobility-related solidarity among them. Furthermore, we include a standard control on gender, expecting variations based on both situational factors and value orientations though not necessarily in a clear-cut way (Blekesaune & Quadagno, Citation2003). We also incorporate a variable that captures individuals’ general predisposition about a just society since it may influence support for (or opposition to) solidarity. A further item controls for threat perceptions, based on respondents’ evaluations of whether the number of immigrants living in their area has increased or not.

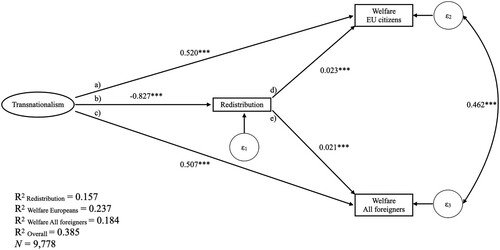

We test our hypotheses by means of structural equation modelling. The model fitted, whose simplified structure excluding controls is reported in , allows for evaluating the direct (and indirect) effects of transnationalism on support for welfare benefits for EU citizens and all foreign legal residents while simultaneously gauging the direct effect of preferences over the equality principle on the two mobility-related dependent variables. The same sociostructural controls described above are included as antecedents of both redistribution and mobility solidarities.

Moreover, given that responses are clustered at the country level, the model includes country dummies (Germany being the reference). This allows controlling for context-specific factors, such as policy regimes, party systems, and prevailing political discourses and identities, which may also influence support for solidarity (Banting & Kymlicka, Citation2017). With this model specification, it is not feasible to draw meaningful conclusions on national welfare states (or other country-level factors) due to the small number of country samples and lack of variation. Given that our items are not normally distributed, we conduct the analysis using the maximum likelihood estimation so that standard errors are estimated without assuming normality. The model presented allows for the correlation between the residuals of our mobility-related solidarities. Analyses are performed on the original survey items using the Stata 17 software and are robust to different specifications (see the Online Appendix for results obtained using weights, excluding political orientations, country-specific models, and fitting both the measurement and structural components simultaneously).

Results: drawing the circles of solidarity

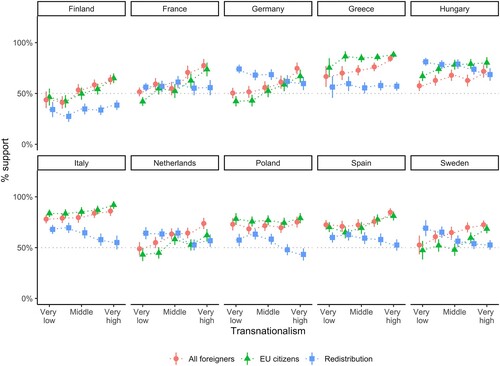

We begin by discussing , which reports respondents’ support for the different types of solidarities by levels of transnationalism in each country.Footnote4 We expected transnationalism to be positively associated with mobility-related redistributive solidarity, and we left to the empirical investigation to evaluate two competing sub-hypotheses: whether transnationalism draws a boundary on solidarity, defining those who deserve to access welfare benefits as EU citizens, or whether its effect spills over to all people ‘on the move’ regardless of their country of origin. The figure depicts the share of respondents agreeing with the inclusion of EU citizens (green triangles), of all foreigners (red circles) legally resident in their domestic welfare system, and the share in favour of redistribution (blue squares). At the aggregate level, we find that as transnationalism increases, so does support for foreigners’ access to welfare. This trend is common to all countries but Italy and Poland, where there is less variation between respondents without transnational background, experiences, and competencies and those with them. What is more, there is generally no significant difference in the share of respondents supporting the access to the national welfare system of EU citizens or of all foreigners legally resident.

Figure 3. Support for solidarity across levels of transnationalism.

Notes: The figure reports average weighted percentages (markers) with 95% confidence intervals (lines). See the note in for details regarding the dichotomization of the three variables.

As for preferences towards redistribution, to reduce inequality we notice that there is not a clear upward trend as transnationalism increases. In most countries included in our analysis, the tendency seems to go in the opposite direction; that is, as transnationalism increases, citizens tend to be slightly more sceptical about redistributive policies. Finland emerges as the only country with a seemingly positive association between transnationalism and general redistribution.

and and summarize more robust tests of our hypotheses, including controls. shows full model coefficients of direct effects (Table H in the Appendix shows standardized coefficients of total and indirect effects), while shows instead the direct, indirect, and total standardized effects of our main explanatory variable, transnationalism, on the three endogenous variables.Footnote5 reports the structure of the recursive path analysis model fitted along with the standardized coefficients for the direct effects as well as the correlation of the error terms of mobility-related solidarities. To ease presentation, controls are not reported, but they are included as independent variables in all three models explaining the three types of solidarities. We report the R2 for each endogenous variable and the sample size. The model explains about 16 per cent of the variance of redistribution, 23.7 per cent of the variance of support for EU citizens’ access to welfare, and slightly more than 18 per cent of all legally resident foreigners.

Figure 4. Standardized estimates for transnationalism and support for redistribution and mobility-related solidarities with correlated errors.

Note: Standardized coefficients from models in and Table H of the Online Appendix.

Table 2. Standardized coefficients of direct effects from the structural equation model.

Table 3. Standardized effects of transnationalism and redistribution on mobility solidarities with correlated residuals.

Looking at the coefficient of arrow a) in , we find a positive and statistically significant association between individual transnationalism and support for the inclusion of EU citizens into domestic welfare systems. Going from no to full transnationalism increases the probability of being in favour of the acceptance of EU citizens to access national social benefits, even after controlling for the structural background of respondents and their attitudes. Arrow c) of reports the standardized coefficient of transnationalism on support for granting access to the same social security benefits for all foreigners legally resident in a country. Reading this result in combination with the one seen previously, we can say that European forms of transnationalism exert a positive influence on the inclusion of migrants into domestic welfare systems regardless of citizenship status. As a matter of fact, the coefficient of arrow a) is comparable in terms of direction and magnitude to the one of arrow c). Overall, we can say that transnationalism is positively associated with mobility-related redistributive solidarity, and the strength of the association is indistinguishable between intra-EU mobile citizens in specific, and foreigners more broadly, thus lending support to H1b.

What is more, the model suggests that redistribution preferences to reduce inequality are positively associated with support for extending welfare benefits to EU citizens or all foreigners, thus confirming H3. Both standardized coefficients of arrows d) and e) are indeed positive and statistically significant as well as similar in magnitude. This result indicates that people more in favour of equality tend also to favour the inclusion of EU citizens/foreigners in welfare systems. This contrasts the findings of Baute et al. (Citation2019) on Belgium, who find that support for the national welfare state is positively related to Social Europe except when it comes to EU social citizenship (i.e., mobile citizens’ access to the welfare state of the receiving country). The authors explain this result by arguing that respondents perceive the latter as intruding too deeply in nationally organized solidarity spaces. However, the authors also find a positive effect between support for the national welfare state and support for a European social security system, which according to their conceptualization, would represent an even more profound reshuffling of national and EU involvement in social policy than EU migrants’ access to national welfare. To us, this suggests that the results of Baute et al. (Citation2019) on EU social citizenship could be driven by opinions regarding intra-EU migration as a highly politicized cultural issue rather than the degree of intrusiveness in national welfare systems. Differences in country cases or timing may also explain the diverging result. First, we are conducting our analyses on a different set of countries that do not include Belgium. Second, our data was collected five years after the data used by Baute et al. when immigration was not as salient as after the 2015–2016 Schengen crisis. Moreover, at the time of the 2019 survey, the issues of EU integration and solidarity had increased in salience and politicization (Pagano & Regazzoni, Citation2019).

To evaluate our second hypothesis, we look at the coefficients of arrow b) in . We argued that cross-border practices and experiences across the EU are associated only with a form of solidarity that implicates mobility but that is unrelated to general redistributive solidarity. This, we argued, taps the socioeconomic dimension of political conflict. The model shows that individual-level transnationalism is negatively associated with a more generic version of solidarity, which entails the redistribution of income to reduce inequalities in one’s country. Since individual transnationalism is associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in egalitarian preferences, we cannot confirm our H2.

Why is individual transnationalism positively associated with economic liberalism but at the same time positively associated with social justice with regard to foreigners? The underlying mechanism is unclear, but it is possible that the affinity of transnationalism with post-material values makes people less receptive to economic (as opposed to non-economic) facets of social inequality (Teney & Helbling, Citation2017; see also Iversen & Soskice, Citation2019). Alternatively, transnationalism could nurture preferences for liberal policies not only when it comes to cross-border social interactions but also in the realm of welfare state principles. Liberal welfare regimes typically do not include forms of redistribution to reduce income inequality (Jaeger, Citation2009), and thus transnational individuals could find themselves opposing (or being neutral to) this form of redistributive solidarity. The negative association is also reminiscent of a scholarly debate conducted mainly in relation to cosmopolitanism, which proposes that international mobility is ultimately an individualizing experience, which not only leads to the disengagement of people from traditional national communities but also fails to supplant these with ‘higher-order’ solidarities (see Ciornei & Recchi, Citation2017, p. 469; drawing on Calhoun, Citation2003, among others).Footnote6 However, as we have already demonstrated, individual transnationalism is actually a straightforward foundation for solidarity when this relates to cross-border mobility.

The third column of reports the indirect standardized effects of transnationalism, mediated by the general redistribution preferences, on the two mobility-related solidarities. In both cases, the effect is very small (about 3 per cent of the direct effect) but statistically significant and negative. Given that it is lower in magnitude than the direct positive effect of transnationalism on the two measures of mobility solidarities, the total effect of cross-border European practices and experiences remains positive.

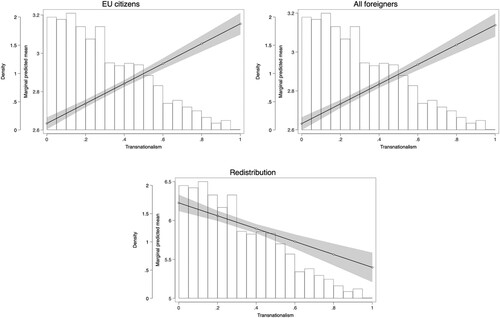

Because of the non-linear nature of the models, to appreciate the strength and the significance level of the association between transnationalism and the three dependent variables, we computed the predicted probabilities that respondents would express solidarity attitudes at changing values of the transnationalism index. Results are reported in . Moving from zero to full transnationalism increases the marginal predicted mean of allowing EU citizens access to national welfare benefits from 2.63 to 3.15 and similarly for all foreigners from 2.63 to 3.14 (recall that in both cases answers were given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4). Instead, the marginal predicted mean of redistribution preferences decreases along transnationalism levels from 6.22 to 5.40 (on a scale from 0 to 10).

Figure 5. Change in the predicted probability of solidarities across levels of transnationalism.

Note: Predicted probabilities computed from models in and Table H of the Online Appendix with an underlying distribution of transnationalism.

Country-specific models largely support pooled sample findings but with some variation. Table V in the Online Appendix summarizes the direct, indirect, and total effects of transnationalism and redistribution for each country separately. The standardized coefficients of transnationalism on the two mobility-related forms of solidarity are positive and statistically significant in eight countries: Germany, Italy, Finland, France, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Sweden. For Greek respondents, it is instead associated only with offering the same welfare benefits to all foreigners legally resident, while in Hungary it is only associated with EU citizens. The direct effect of transnationalism on redistribution is statistically significant and negative in six countries: Germany, Italy, Hungary, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden. Egalitarian preferences over redistribution return a non-statistically significant association with both mobility-related solidarities in the Netherlands and Spain, while in the other countries surveyed, it is positively associated with at least one of the two variables (in Finland and Poland, only with extending welfare benefits to EU citizens; in Sweden and Hungary, with support for all foreigners) or both (in Greece, Germany, Italy, and France). The small number of countries available does not allow us to draw conclusions on possible sources of this variation, but future research should try to address whether country-level factors play a role (for example, type of welfare arrangements in place or number of immigrants).

Regarding sociodemographic control variables (see and Online Appendix Table H), when it comes to preferences over equality (general redistribution), we found both structural conditions and orientations to be associated with it. Women, employers, and the self-employed tend to oppose redistribution more compared to their respective reference category (men and the unemployed). Instead, older people are more pro-redistribution compared to younger generations and so are those reporting situations of material deprivation in their household. Finally, people prioritizing help for those in need as well as left-wingers and those who are pro-EU integration tend to favour more redistribution compared to their counterparts. In this case, exclusive national identity does not play a role.

Conversely, attitudes towards mobility-related redistributive solidarity are associated mainly with other attitudes rather than sociodemographic factors or perceptions of increased immigration in one’s area of residence. No significant difference around occupation emerges when looking at the two forms of mobility-related solidarity, while economic deprivation reduces support for including all foreigners in the domestic welfare system. A strong predictor of general and mobility-related redistributive solidarity is the predisposition towards helping others in need. Political orientations, captured by support for EU integration and ideology, are indeed the strongest predictors of allowing access to social security benefits to both EU citizens and all foreigners. Note that in this case, the measure capturing the transnational divide explains a larger part of the variance than the left-right ideology. Exclusive national identity, as expected, has a statistically significant negative effect on mobility-related solidarity, though the magnitude of the effect is rather small. Overall, our results confirm that the two types of redistributive solidarity, mobility-related and general, tap different political cleavages.

Conclusion

This article departs from the observation that ‘whereas the nation-state has been the sole and uncontested pivot of identity, belonging, political loyalty and accountability during its golden age, the proliferation of transnational interaction is broadening people’s cognitive and normative horizons’ (Mau et al., Citation2008, p. 16). The EU in particular is a unique project of regional integration beyond the nation-state, and the interactions of EU citizens across borders are thought to constitute the social basis for a supranational polity. It is therefore paramount to understand if and how individual transnationalism may be contributing to shifts in people’s attitudes and frames of mind.

We have found that individuals whose interactions, cultural competences, and backgrounds span national borders are more likely to endorse the inclusion of all foreigners, not only EU citizens, into domestic welfare arrangements. This result echoes previous findings in the Italian context (Pellegata & Visconti, Citation2021) and those of group contact theory according to which reduced prejudice against one outgroup may generalize to other outgroups (Binder et al., Citation2009; Pettigrew et al., Citation2011). Individuals whose lives cut across national borders not only tend to exhibit above-average levels of support for EU integration, as established by prior research, but also solidaristic attitudes towards people ‘on the move’. Individual transnationalism, therefore, is an important source of solidarity with migrants, who are often the targets of exclusionary attitudes and practices, especially when it comes to their access to welfare (Careja & Harris, Citation2022). However, we have found a negative association between transnationalism and general pro-redistribution attitudes for the respondents of the ten sample countries included in our survey. This leads us to conclude that personal backgrounds, practices, and competences that cut across national borders are not linked to a type of unbounded solidarity but rather configure social boundaries differently, boosting a form of solidarity that resonates with the experiences and needs of transnational individuals.

The unexpected negative association of individual transnationalism with general redistributive solidarity is more puzzling. It recalls a scholarly debate that links cosmopolitanism to a ‘thin’ conception of social life and belonging, which neglects the role of solidarity as a social resource while reifying an individualistic ethos (Calhoun, Citation2003). Put less starkly, even as transnationalization contributes to the development of feelings of care and responsibility towards non-national outsiders, at the same time it may ‘weaken’ traditional bonds (Mau et al., Citation2008, p. 5). Our findings could be an indication for this pattern, though the underlying mechanism is obscure and at odds with existing studies that find that transnational allegiances are layered or nested into national ones rather than replacing them (Medrano & Gutiérrez, Citation2001; Teney & Helbling, Citation2017). At the same time, it is also clear that individual transnationalism is not uniformly associated with any form of solidarity even when looking only at variants that span national borders: according to Ciornei and Recchi (Citation2017), it is positively associated with solidarity among EU member states but not among needy EU citizens. Taken together with our results, this suggests that, at minimum, the reconfiguration of solidarities ‘in an era of loosening social moorings’ (Marks et al., Citation2021, p. 175) is an uneven and volatile process.

We cannot exclude the possibility that respondents who score high on the transnationalism scale are more prone to provide socially desirable answers when it comes to the highly politicized issue of migrants’ access to welfare. As we have included a heterogenous set of countries in our survey sample, this lends confidence to the generalisability of our findings in other member states as well, though idiosyncratic differences are always possible. We shall, however, stress that since the number of countries is too small to conduct a multilevel analysis, we cannot evaluate the role played by different welfare systems but can only appreciate country-level aggregate differences. Finally, the reconfiguration of a system of allegiances and identifications assumed by Deutsch and others would unfold in the long term and cannot be captured by a cross-sectional snapshot and correlational findings. These limitations point to the need for future research that builds on our findings.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (808 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers, for their precious comments and suggestions on previous versions of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Francesco Visconti

Francesco Visconti is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Social and Political Sciences of the University of Milan. Previously he has worked as a Research Fellow at the University of Leicester. He holds a PhD in Comparative and European Studies from the University of Siena.

Anna Kyriazi

Anna Kyriazi is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Social and Political Sciences of the University of Milan. Previously she was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow Juan de la Cierva-Formaciòn at the Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internationals. She holds a PhD in Political and Social Sciences from the European University Institute.

Notes

1 Banting and Kymlicka add a third prong to redistributive solidarity, namely support for programmes that recognize and accommodate the distinctive needs and identities of different ethnocultural groups. They also distinguish redistributive solidarity from two other dimensions: democratic solidarity and civic solidarity.

2 This research design is fairly uncommon in the existing literature. An exception is Ignácz (Citation2021), who takes a similar approach to ours by explicitly assessing analogies between European and national solidarity.

3 A detailed description of the questions can be found in the Online Appendix.

4 Five levels of transnationalism are defined: ‘Very low’ for those with a transnationalism score between 0 and the 20th percentile; ‘Low’ for scores between the 20th and the 40th percentiles; ‘Middle’ for scores between the 40th and the 60th percentiles; ‘High’ for scores between the 60th and the 80th percentiles; and ‘Very high’ for scores higher than the 80th percentile.

5 The significance levels are based on the unstandardized solutions.

6 Cosmopolitanism and transnationalism are distinct but nonetheless closely related phenomena, which also explains why the terms are also used sometimes interchangeably in the literature. Transnationalism refers to social practices and relationships that foster cosmopolitan attitudes and values, which entail the recognition of the increasing interconnectedness of political communities around the world, an understanding of overlapping fortunes requiring common solutions, and the celebration of cultural diversity (Mau et al., Citation2008, p. 5).

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- Banting, K., & Kymlicka, W. (2017). The strains of commitment: The political sources of solidarity in diverse societies. Oxford University Press.

- Baute, S., Meuleman, B., & Abts, K. (2019). Welfare state attitudes and support for social Europe: Spillover or obstacle? Journal of Social Policy, 48(1), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279418000314

- Binder, J., Zagefka, H., Brown, R., Funke, F., Kessler, T., Mummendey, A., Leyens, J. P., Demoulin, S., & Leyens, J.-P. (2009). Does contact reduce prejudice or does prejudice reduce contact? A longitudinal test of the contact hypothesis among majority and minority groups in three European countries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 843–856. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013470

- Blekesaune, M., & Quadagno, J. (2003). Public attitudes toward welfare state policies: A comparative analysis of 24 nations. European Sociological Review, 19(5), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/19.5.415. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3559532

- Calhoun, C. (2003). ‘Belonging’ in the cosmopolitan imaginary. Ethnicities, 3(4), 531–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796803003004005

- Careja, R., & Harris, E. (2022). Thirty years of welfare chauvinism research: Findings and challenges. Journal of European Social Policy, 32(2), 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/09589287211068796

- Ciornei, I., & Recchi, E. (2017). At the source of European solidarity: Assessing the effects of cross-border practices and political attitudes. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(3), 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12507

- Crepaz, M. M. (2008). Trust beyond borders: Immigration, the welfare state, and identity in modern societies. University of Michigan Press.

- Delhey, J., Deutschmann, E., & Cirlanaru, K. (2015). Between ‘class project’ and individualization: The stratification of Europeans’ transnational activities. International Sociology, 30(3), 269–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580915578744

- Deutsch, K. W., Burrell, S. A., Kann, R. A., & Lee, M. (1957). Political community and the north Atlantic area. Greenwood Press.

- De Vries, C. E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the future of European integration. Oxford University Press.

- De Wilde, P. (2019). Mapping policy and polity contestation about globalization: Issue linkage in the news. In P. De Wilde, R. Koopmans, W. Merkel, O. Stribijs, & M. Zürn (Eds.), The struggle over borders (pp. 89–115). Cambridge University Press.

- Donati, N., Pellegata, A., & Visconti, F. (2021). European solidarity at a crossroads. Citizen views on the future of the European Union (REScEU Working Paper). http://www.euvisions.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/mass_survey_report_2019-1.pdf

- European Parliament. (2016). Major changes in European public opinion regarding the European Union. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2016/major-changes-in-european-public-opinion-2016/report/en-report-exploratory-study-201611.pdf

- Ferrera, M. (2005). The boundaries of welfare: European integration and the new spatial politics of social protection. Oxford University Press.

- Ferrera, M. (2009). The JCMS annual lecture: National welfare states and European integration: In search of a ‘virtuous nesting’. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 47(2), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2009.00802.x

- Gerhards, J., Lengfeld, H., Ignácz, Z. S., Kley, F. K., & Priem, M. (2019). European solidarity in times of crisis: Insights from a thirteen-country survey. Routledge.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Ignácz, Z. S. (2021). Similarities between European and national solidarity. Sozialpolitik, 1, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.18753/2297-8224-172

- Iversen, T., & Soskice, S. (2019). Democracy and prosperity: Reinventing capitalism through a turbulent century. Princeton University Press.

- Jaeger, M. M. (2009). United but divided: Welfare regimes and the level and variance in public support for redistribution. European Sociological Review, 25(6), 723–737. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn079

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2006). Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research, 45(6), 921–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x

- Kuhn, T. (2015). Experiencing European integration. Transnational lives and European identity. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199688913.001.0001

- Kuhn, T. (2019). Grand theories of European integration revisited: Does identity politics shape the course of European integration? Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1213–1230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1622588

- Kulin, J., & Svallfors, S. (2013). Class, values, and attitudes towards redistribution: A European comparison. European Sociological Review, 29(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr046. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24479960

- Kyriazi, A., & Visconti, F. (2021). The Europeanisation of political involvement: Examining the role of individual transnationalism. Electoral Studies, 73, Article 102383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102383

- Lahusen, C. (2020). Citizens’ solidarity in Europe: Civic engagement and public discourse in times of crises. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lahusen, C., & Grasso, M. T. (2018). Solidarity in Europe: Citizens’ responses in times of crisis. Springer Nature.

- Marks, G., Attewell, D., Rovny, J., & Hooghe, L. (2021). Cleavage theory. In M. Riddervold, J. Trondal, & A. Newsom (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of EU crises (pp. 173–193). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mau, S., Mewes, J., & Zimmermann, A. (2008). Cosmopolitan attitudes through transnational social practices? Global Networks, 8(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2008.00183.x

- Medrano, J. D., & Gutiérrez, P. (2001). Nested identities: National and European identity in Spain. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 24(5), 753–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870120063963

- Miller, D. (1995). On nationality. Clarendon Press.

- Pagano, G., & Regazzoni, P. (2019). The social dimension in the electoral programs of the European political groups. EuVisions. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from http://www.euvisions.eu/the-social-dimension-in-the-electoral-programs-of-the-european-political-groups/?pdf=2070

- Pellegata, A., & Visconti, F. (2021). Transnationalism and welfare chauvinism in Italy: Evidence from the 2018 election campaign. South European Society and Politics, 26(1), 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2020.1834214

- Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

- Recchi, E., & Favell, A. (2019). Everyday Europe: Social transnationalism in an unsettled continent. Policy Press.

- Reinl, A. K. (2022). Transnational solidarity within the EU: Public support for risk-sharing and redistribution. Social Indicators Research, 163(3), 1373–1397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02937-2

- Salamońska, J., & Recchi, E. (2016). Europe between mobility and sedentarism: Patterns of cross-border practices and their consequences for European identification (Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Paper No. RSCAS, 50).

- Schotte, S., & Winkler, H. (2018). Why are the elderly more averse to immigration when they are more likely to benefit? Evidence across countries. International Migration Review, 52(4), 1250–1282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318767927

- Stjernø, S. (2009). Solidarity in Europe: The history of an idea. Cambridge University Press.

- Teney, C., & Helbling, M. (2017). Solidarity between the elites and the masses in Germany. In K. Banting & W. Kymlicka (Eds.), The strains of commitment: The political sources of solidarity in diverse societies (pp. 127–151). Oxford University Press.

- van der Waal, J., Achterberg, P., Houtman, D., De Koster, W., & Manevska, K. (2010). ‘Some are more equal than others’: Economic egalitarianism and welfare chauvinism in the Netherlands. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(4), 350–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928710374376

- van Parijs, P. (2017). Concluding reflections. In W. Kymlicka & K. G. Banting (Eds.), The strains of commitment: The political sources of solidarity in diverse societies (pp. 420–426). Oxford University Press.

- Verhaegen, S. (2018). What to expect from European identity? Explaining support for solidarity in times of crisis. Comparative European Politics, 16(5), 871–904. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-017-0106-x

- Ziller, C., & Careja, R. (2022). Personal and contextual foundations of welfare chauvinism in Western Europe. In M. M. L. Crepaz (Ed.), Handbook on migration and welfare (pp. 175–194). Edward Elgar.