ABSTRACT

The ‘regulatory state’ has prevailed in almost every sector of European public policy. The provision of security, however, is still widely viewed as the domain of the ‘positive state’, which rests on political authority and autonomous capacities. Challenging this presumption, we argue that expertise – as foundation of authority – and rules – as policy instruments – also shape the provision of European security by national and, in particular, supranational ‘regulatory security states’, namely the European Union (EU). We lay out a framework for mapping the uneven and contested rise of European regulatory security states; analyzing drivers and constraints of security state reforms; and grasping the implications of the regulatory security state for the effectiveness and democratic legitimacy of European security policy-making. We advance the research program on the regulatory state and contribute to an innovative understanding of who governs security in Europe’s multi-level polity, by what means, and on what legitimatory grounds.

Introduction

Who governs European security, by what means, and on what legitimatory grounds? The conventional wisdom holds that European security is the realm of the ‘positive state’ (Majone, Citation1997), which has a monopoly on the political authority to make collectively binding decisions and hoards the operational capacities required to implement them (Mérand, Citation2008; Hofmann, Citation2013; Paul & Ripsman, Citation2010; Bruin, Citation2020; see Genschel & Zangl, Citation2014). The security state is ‘positive’ in that it bases its authority on political entitlement, while relying on the direct command and control of coercive capacities such as its armed forces (Tilly, Citation1985; Weber, Citation1978). By these standards, the European Union (EU) is not a security state in any meaningful sense, since the authority delegated to it in matters of security is limited and its operational capacities remain scarce (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2014; see Bellanova et al., Citation2022).

This special issue challenges the conventional wisdom at both the theoretical and the empirical level. Contrary to the notion of an unrivaled prevalence of sovereign ‘positive security states’ (PSSs) in Europe, we conceive of both the EU and its member states as emerging ‘regulatory security states’ (RSSs). They rely in various security fields on epistemic authority to govern indirectly by means of rules. While political authority and governing by capacities have not become obsolete, national PSSs are being superseded by a multi-level European RSS. The latter manifests itself across various national and supranational policy-making activities in European security which are hard to understand from a PSS-only perspective.

Take even the response of the EU and European states to Russia’s war against Ukraine in 2022. At first glance, this large-scale territorial invasion seems to point to the resurgence, if not the perennial predominance, of sovereign and positive security states (see Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2023): Coercive state capacities undeniably drove Russia’s attack. European policy-makers, in turn, emphasized their resolve to build up coercive capacities in the wake of the war, and the EU has underlined its aspirations for strategic autonomy. Yet, a closer look reveals how attributes of the RSS have taken root even in military security, i.e., the home-turf of the PSS, shaping the European response to Russia’s invasion. Europe’s coercive policy instruments have combined (direct and indirect) military and economic means to compel Russia’s withdrawal from Ukrainian territory. First, governments turned to nudging private arms contractors into building up new production lines to sustain arms transfers to Ukraine, rather than exclusively drawing on national military capacities such as stockpiles of weapons and ammunition (Der Spiegel, Citation2022). Second, instead of setting up a traditional sanctions regime, economic experts pushed the EU and its member states to ban Russian banks from the SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) code (Council of the European Union, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). They thus sought to coerce Russia by manipulating one of the ‘chokepoints’ of the global financial system (Farrell & Newman, Citation2019), which is a private entity under Belgian law.

Beyond these immediate responses to the war, entrenched RSS characteristics of rules- and expertise-based governance will continue to shape European military policies in the medium and longer-term: due to path-dependencies, it will be much harder for the – traditionally regulatory polity – EU and even resource-strong member states to implement plans of capacity-building and strategic autonomy than it was to devise them. Given that the RSS is – to varying extents – locked in, expertise and rules-based governance persistently shape indirect modes of European security policy-making even in military security, i.e., the alleged core domain of the PSS. For instance, the proliferation of rules promulgated by expert bodies followed the large-scale privatization of military goods and services in various European countries in the 1990s (Kruck, Citation2014, Citation2020; Leander, Citation2013; Weiss & Biermann, Citation2021b). Moreover, the EU has ventured into military security by setting rules that prescribe standards for how member states acquire weaponry (Blauberger & Weiss, Citation2013; Hoeffler, Citation2012; Schilde, Citation2017) or how they may transfer arms (Erickson, Citation2013).

Beyond the traditional realm of military security, regulatory efforts by experts and thus the presence of the RSS loom even larger in newer, non-traditional fields of security. For instance, the protection of Europe’s critical infrastructures, such as energy and telecommunication networks, is also guaranteed by private actors that follow rules set by technical expert agencies in the European countries (Hansen & Nissenbaum, Citation2009; Weiss & Biermann, Citation2021a). Besides relying on their default instrument of regulation, supranational EU actors have drawn on claims to superior expertise in, for instance, cybersecurity to become a force to be reckoned with in the making of European cybersecurity policies (Carrapico & Barrinha, Citation2017; Csernatoni, Citation2022). Thus, the trajectories of both national and supranational security policy-making in the past three decades suggest the emergence and institutionalization of a regulatory security state in Europe’s multi-level polity.

To be clear, as several contributions to this special issue echo, these developments have often involved contested political struggles rather than smooth functional adaptations (Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023; Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; Leander et al. Citation2023; Mügge, Citation2023; Bode & Huelss, Citation2023). They have usually been uneven so that the RSS is more established in some polities and some policy fields than in others. Most notably, the ‘regulatory polity EU’ has systematically been more inclined to rely on rules-based governance than the EU’s resource-strong member states (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2023; Hoeffler, Citation2023; Schilde, Citation2023; Rimkutė & Mazepus, Citation2023). Neither does the growth of regulatory security governance signify a secular, teleological trend: combinations of rules- and capacity-based instruments and even countervailing political ambitions towards the PSS can be observed in issues well beyond recent European responses to Russia’s war in Ukraine (see Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023; Levi-Faur, Citation2023; Hoeffler, Citation2023; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2023). Yet, the RSS is a political reality in many polities and sub-fields of European security that needs to be acknowledged to better understand the recent past of European security policy-making and to chart its future course.

Against this background, our special issue, first of all, maps the uneven and contested emergence as well as the presence of the RSS in Europe. Second, it explains its causes by analyzing the drivers of, and constraints on, the reform of security states. Third, it investigates its consequences for security policy-making in Europe (and beyond). With different emphases, the contributions, therefore, address three sets of questions:

To what extent has a European regulatory security state emerged and taken root in different subfields and polities, including both within the EU as an organization and within its member states?

What drives and what constrains the rise of the European RSS and what shapes the variations in types of security state across security issues and polities?

What are the key implications of the rise of the RSS for the effectiveness and democratic legitimacy of European security policy-making?

To answer these questions, we do not need to reinvent the wheel. Rather, we can draw on one of the most progressive research programs in European public policy: The ‘regulatory state framework’ (Guidi et al., Citation2020; Jordana & Levi-Faur, Citation2004; Koop & Lodge, Citation2017; Levi-Faur, Citation2005; Majone, Citation1994, Citation1997) has traveled to Africa (Klaaren, Citation2021) and Asia’s emerging economies (Lavenex et al., Citation2021) and been applied in virtually all policy fields (Benish & Levi-Faur, Citation2020; Levi-Faur, Citation2011; Mathieu, Citation2016). To date there has been one major exception, which is why we now introduce the ‘regulatory state’ to European security politics.

This special issue investigates, from a ‘regulatory state’ perspective, traditional military security fields, such as arms production and military innovation (Hoeffler, Citation2023; Schilde, Citation2023), the digital security domains of cybersecurity, digital law enforcement, and military applications of artificial intelligence (Bode & Huelss, Citation2023; Dunn-Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023; Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; Mügge, Citation2023), as well as individual security related to health, safety and fundamental rights (Rimkutė & Mazepus, Citation2023; Leander et al., Citation2023). Collectively, the contributions suggest the pervasiveness of the RSS, but they also point to its uneven strength across security challenges. The RSS is particularly prevalent in the non-traditional fields of digital and individual security. Most significantly, the special issue findings underline that the RSS has been enjoying a comparative advantage in digital security, where state capacities have hardly pre-existed and the only available policy instruments frequently stem from non-state actors. However, it is not limited to them. The RSS has also established itself in the domain of individual security and safety. Notably, it even extends to traditional military security, where it tends to combine regulatory instruments with capacity-based governance. Beyond this mapping, taking the regulatory state framework to the new terrain of European security allows us to make three major contributions.

First, we demonstrate how the framework applies to the analysis of security policy-making, which is normally conceived of as a least likely case of integrating core state powers (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2014, Citation2018; Kuhn & Nicoli, Citation2020). As the regulatory security state is to some extent distinct and unique, we offer comparative insights into the specificities of the regulatory state as it operates in security rather than in other domains. Most significantly, we highlight how regulatory security states often keep striving for new capacities and combine rules-based and capacities-based governance (Hoeffler, Citation2023; Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023) in such a way that one approach supplements or even fosters the other. In other words, the one (i.e., relying on rules) does not necessarily exclude the other (i.e., capacity-building). Above all, the supranational European RSS often seeks to mobilize and draw on member states’ capacities.

Second, our theoretical value-added to the research program on the regulatory state (see Levi-Faur, Citation2023) lies in conceiving of the RSS as a distinct combination of rules-based policy instruments and expertise-based foundations of authority. While previous scholarship focused primarily on regulation, we put the distinction between the political and epistemic foundations of authority center stage. We thus advance the research program from merely acknowledging the importance of expert bodies (Guidi et al., Citation2020; Levi-Faur, Citation2005, Citation2011; Majone, Citation1994, Citation1997; Rittberger & Wonka, Citation2011) toward conceptualizing the role of expertise as tantamount to a constitutive attribute: epistemic authority and proliferating rules co-constitute the RSS. We thus lay the ground for contributions studying the complementarities between epistemic foundations of authority and rules-based instruments (e.g., Bode & Huelss, Citation2023; Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023).

Third, the RSS framework contributes to a better understanding of security politics in Europe, particularly in the EU. Unlike most scholarship that has understood collaborative European security policies as instances of integration, we draw on a state-building perspective (Kelemen & McNamara, Citation2022; see Mérand, Citation2008) to formulate a unified analytical framework that is equally applicable to the EU as a supranational organization and to sovereign states in Europe. Similar to the way in which the EU was (re-)conceptualized as a political system in the 1990s (Hix, Citation1994, Citation1999), we suggest that an understanding of the EU’s set-up and activities as different types of ‘security states’ – i.e., ‘seeing the EU like a state’ (McNamara & Kelemen, Citation2022) in security policy making – will allow for innovative research questions and a new approach to the evolution of European security. However, in contrast to recent debates on whether and under what conditions the EU is building centralized capacities, i.e., developing ‘positive’ statehood, in security (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2022; Freudlsperger & Schimmelfennig, Citation2022; Genschel, Citation2022; Kelemen & McNamara, Citation2022), we shift the focus on regulatory state-building and its implications. While, for example, the European Defence Fund (EDF) can certainly be regarded as an instance of supranational integration (Haroche, Citation2020), our regulatory-state-building perspective sheds new light on the politics of policy instruments and the power-distributive implications that result from it (Hoeffler, Citation2023). We show that the European regulatory polity has expanded into another policy field, with security becoming more similar to other issue-areas where the regulatory state had taken root long ago. Several contributions find supporting evidence for this expectation while also pointing out empirical ambiguities and simultaneous trends toward the PSS (e.g., Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023) as well as normative challenges associated with the RSS (Leander et al., Citation2023).

In the remainder of this introduction, we first conceptualize the RSS by distinguishing it from the PSS and report key findings from the mappings made by the individual contributions. Second, we introduce a theoretical framework, whose interest-, institution- and ideas-based conjectures help explain when and how actors reform security states in response to technological change. Finally, we draw on the relevant special issue contributions to elaborate on how the RSS in Europe impacts on the effectiveness and democratic legitimacy of European security policy-making.

Positive and regulatory security states in Europe

Our notion of security states builds on a relational understanding of authority and statehood (Lake, Citation2010; see Abbott et al., Citation2020). In contrast to formal-legal conceptions, a relational understanding of authority starts out from an exchange relationship: ‘A provides a political order of value to B sufficient to offset the loss of freedom incurred in his subordination to A, and B confers the right on A to exert the restraints on his behavior necessary to provide that order’ (Lake, Citation2010, pp. 595–596). Control is traded against order. The resulting equilibrium is either reproduced or transformed by actors’ interactions. This understanding of (security) states is applicable to both national and supranational polities. The EU can, therefore, be as much a security state as Germany or Sweden. Yet, there is not only variation in who is in charge of security (i.e., member states vs. the EU), but also in why these actors have the recognized authority to make collectively binding decisions and how they govern different security sectors.

We, and the contributions to this special issue, operate with an understanding of security which acknowledges that ‘the international security landscape is far more complex than it has been in a long time’ (Gheciu & Wohlforth, Citation2018, p. 4). There is a proliferation of diverse actors across national, transnational and supranational levels, whose interests converge and diverge with varying intensity (Neumann & Sending, Citation2018). This contested complexity of contemporary security suggests not only studying a diverse set of policy fields across different levels, but also investigating both antagonisms and collusion of interests among actors of European security governance. Hence, this special issue analyzes the politics of policy instruments (e.g., Hoeffler, Citation2023) and of predominant foundations of authority (e.g., Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Rimkutė & Mazepus, Citation2023) regarding various security issues in Europe’s complex multi-level settings.

From this perspective, policy-making in security seeks not only to protect individuals and groups from eminent threats to their physical integrity, but also aims at safeguarding their ability to act as independent and purposive entities. This complex notion of security thus ranges from individuals’ protection against bodily harm (individual security) via guaranteeing individual and collective actors’ ability to act in purposive and self-determined ways in digital spaces (digital security) up to polities’ protection from direct violent threats to their integrity and their collective agency (military security) (Börzel & Zürn, Citation2021, p. 293; Wolfers, Citation1962, pp. 150–151; Bode & Huelss, Citation2018; Farrand & Carrapico, Citation2022). In other words, security involves not only survival, but also the ability to purposefully act of both individuals and collective actors in various settings. Such an encompassing and differentiated understanding of security is imperative for our research objective of mapping the (relative) presence and relevance of RSSs and PSSs across a broad range of security issues in Europe.

Our ideal-typical distinction between the positive and the regulatory security state is constituted by differences in two dimensions. First, the predominant policy instrument employed by governors can be either state capacities or rules. The RSS draws on rules to steer and nudge non-state security actors indirectly rather than exercising direct control over coercive capacities like the PSS. Second, the prevailing foundation of the security state’s authority may be either political or epistemic. The RSS legitimates its claim to govern by its expertise and performance as opposed to its institutional entitlement and democratic procedures. Consequently, the RSS can be said to be on the rise in Europe when we observe a double shift toward a foundation of epistemic authority and toward rules as the predominant policy instrument.

Policy instrument

Drawing on research on ‘regulatory governance’, we distinguish between two major policy instruments, namely capacity and rules (Abbott et al., Citation2017; Abbott et al., Citation2020; Benish & Levi-Faur, Citation2020; Genschel & Zangl, Citation2014; Guidi et al., Citation2020; Jachtenfuchs, Citation2001; Levi-Faur, Citation2005, Citation2011; Majone, Citation1994, Citation1997).

Governing by capacity implies that the security state commands and controls coercive state capacities in order to produce collective goods directly. The capacities in question are standing action resources that are most clearly manifested in the armed forces, police, and intelligence services of sovereign states, all of which are employed to the use of force (Ripsman & Paul, Citation2010; De Bruin, Citation2020). In this conception, the key means of and prerequisite for governing is the amassment and direct deployment of operational capacities (Genschel & Zangl, Citation2014) that allow the security state to unilaterally provide security on a large scale and at significant cost. While the regulation of third parties may also occur, the making and enforcement of rules remain secondary. Capacity-building and its direct use take precedence.

By contrast, governing by rules implies that the security state draws up regulations that incentivize the provision of collective security-relevant goods by other actors. Its prime activities include legislative, bureaucratic-administrative, and judicial rule-making and rule-implementation in national and transnational settings.Footnote1 The security state protects members against security threats by laying down and enforcing rules that shape the behavior of ‘intermediary’ third parties and the governed (Abbott et al., Citation2017). This presupposes regulatory (rule-setting and rule-implementing) competence on the part of the security state (Abbott et al., Citation2020; Weiss & Jankauskas, Citation2019).

Two sets of rules can be distinguished. On the one hand, general rules, such as directives from the EU or national legislatures, are directed at a broad range of addressees and apply to all in the same way. Given their general scope and applicability, these rules have a widespread impact, but usually provide their addressees with some leeway as to how to implement them. On the other hand, the security state may also regulate by setting specific rules and criteria through contracts, as exemplified in the privatization of state-owned security suppliers (Weiss & Biermann, Citation2021b; Weiss & Heinkelmann-Wild, Citation2020). The specific nature of these rules limits their diffusion, but they exert a more direct influence on the contracting party. Their implementation is usually monitored more tightly. Historically, it has been these specific contractual regulations in particular that have associated privatization schemes with the rise of regulatory security states (Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023).

These two policy instruments may be used to achieve the same goals, for instance to address a specific security threat. Take, for instance, the risk of arms transfers to potential adversaries (Erickson, Citation2018; Horowitz, Citation2010). If a security state draws on its own operational capacities to innovate, it may directly prevent the transfer of any security-relevant products to another state. By contrast, if third parties within a security state’s jurisdiction innovate, the security state may regulate these actors to bring their behavior into line with its security goals. The security state may either set general rules on the transfer of security-relevant goods and services or set specific rules as part of a contract, such as to maintain the intellectual property rights for any military innovation. While the security objective is the same – to deny adversaries military technology – the chosen policy instrument varies.

Foundation of authority

The notion of relational authority (Lake, Citation2010), which puts exchanges and contracts between governor and governed at the center of analysis, serves as the common ground for more specific forms of authority. We distinguish between two types of foundation for authority – political and epistemic – both of which can underlie national as well as supranational security states in Europe (Zürn, Citation2018, pp. 50–53; Weber, Citation1978, pp. 215–226; Haas, Citation1992; Abbott et al., Citation2020). These foundations refer to the prerequisites and legitimating justifications for making collectively binding security decisions.

Political authority rests on the recognition of an actor or an institution as being ‘authorized to make collectively binding decisions in order to promote the common good and to prevent chaos’ (Zürn, Citation2018, p. 51). The source of the governor’s authority is the recognized claim that it is in the rightful institutional position to make collectively binding decisions on how to protect community members from bodily harm. The governed accept this claim to authority to the extent that they accept the need for collectively binding decisions to promote order and to the extent that they recognize the institutional position of the governor as the one who ought to make such decisions (Lake, Citation2010). From this follows that political authority primarily rests on political entitlement and procedural legitimacy (Majone, Citation1997; Scharpf, Citation1999). Those in power can make security-relevant decisions as they have reached this position in accordance with widely accepted procedures (e.g., democratic elections).

By contrast, epistemic authority rests on the governor’s reputation for expertise, i.e., its expert knowledge and skills (Abbott et al., Citation2020; Louis & Maertens, Citation2021; Steffek, Citation2021). The source of its authority is a recognized claim to be most competent to produce a security-relevant good or a standard of behavior and, thus, political order. The governed accept this claim to authority to the extent that they acknowledge the governor’s superior knowledge and skill in establishing political order (Esterling, Citation2004; Zürn, Citation2018, pp. 52–53). These knowledge claims may be informed by political or economic self-interest, they may be contested, and they are often intertwined with unequal material power positions that privilege some knowledge claims at the expense of others (Rimkutė, Citation2020; Slayton & Clark-Ginsberg, Citation2018). Orders based on expertise are neither politically neutral nor necessarily geared towards the common good (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; Bode & Huelss, Citation2023). Whose expertise and knowledge claims count is often part of political contestations and struggles (Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023). Nevertheless, security orders only rest on epistemic authority as long as the key stakeholders overall recognize the governor’s claims to knowledge and competence. Otherwise, it is not an expertise-based order. Epistemic authority, therefore, rests on substantive legitimacy, that is, the perceived effectiveness of policy-making (Majone, Citation1997; Scharpf, Citation1999). Those in power can make security-relevant decisions as their policies are expected to outperform alternative suggestions for serving the common good.

Either of the two foundations of authority may form the basis for a security state making collectively binding decisions. Take, for instance, the protection of critical infrastructures against adversaries. The security state may derive political authority and legitimacy for an intrusive policy from the governing actors’ rightful positions as democratically elected decision-makers. France’s powerful Agence nationale de la sécurité des systèmes d'information (ANSSI) manages the protection of critical infrastructures in the name of the prime minister, to whom it is directly accountable (Weiss & Biermann, Citation2021a). By contrast, a lot of other European states rely on technical experts not only for advice but also for decision-making with regard to the protection of critical digital infrastructures (Hansen & Nissenbaum, Citation2009, pp. 1166–1167). While the policy instruments are similar in these instances, the foundations for their legitimate exercise vary.

All contributions to this special issue map to what extent we find empirical manifestations of the regulatory or the positive state in European security. ‘Pure’ RSSs and PSSs are best understood as ideal-types; real-world security states usually combine different (i.e., political and epistemic) sources of authority and different policy instruments (i.e., capacities and rules) (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2023; Levi-Faur, Citation2023; Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023; Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Hoeffler, Citation2023). Still, we can fruitfully explore: Which type of security state is prevailing at a particular point in time, within a specific polity, and in a particular sector of European security? Which type of authority and policy instrument is predominant at a given point in time? Is the relative importance of one type of authority or policy instrument increasing relative to the other? How does the predominant type of European security state vary across different fields of security?Footnote2

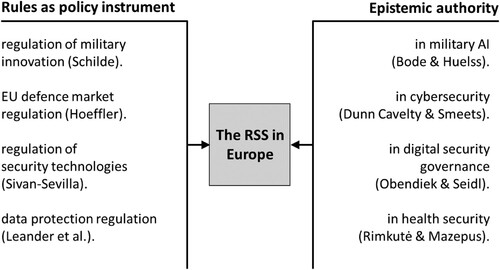

maps some of the special issue’s findings along the two dimensions of security states. Taken together, they highlight that, in many sectors, the characteristics of an RSS are displayed not only by member states, but, in particular, by the EU as an organization.

Collectively, the contributions to this special issue underline that the RSS is not tied to particular narrow types of security problems. Rather, it is a pervasive phenomenon that can be found across European responses to diverse sets of security challenges, suggesting a broad scope of the RSS in Europe. However, albeit wide-ranging, the European RSS reflects an uneven and often contested dynamic. The RSS enters first and foremost those domains of security that have historically depended on extensive collaboration with private actors. The more public goods are provided by markets, the more rules are required (Vogel, Citation1996) and the more intrusive those rules are likely to be. Accordingly, the expansion of rules-based security provision is highly apparent in the development and production of weaponry. Schilde (Citation2023) demonstrates the EU’s role as a rule-maker to trace firms’ behavior as rule-takers. She shows how regulatory means provide incentives for arms production in Europe. Hoeffler’s contribution underlines the resilience of the EU’s rules-based generation of military force. Even though the European Commission attempted to move beyond regulation and cultivate its own capacities via the EDF, it largely failed and had to settle for a position as rule-maker (Hoeffler, Citation2023), rather than exercising command and control over its own coercive capacities.

The RSS also flourishes in domains that have historically been governed by rules and expertise, but which, until recently, were not even regarded as security issues (Mügge, Citation2023). Health security (Rimkutė & Mazepus, Citation2023) as well as the protection of fundamental rights in digital spaces (Leander et al., Citation2023) are prominent instances where ‘normal’ regulatory politics have been superseded by a security logic. The RSS is particularly well established in digital security domains, which are at the center of technological change (Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023). The novelty of, for instance, artificial intelligence (Bode & Huelss, Citation2023; Mügge, Citation2023) or cloud computing (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023) suggests not only a prominent role for expertise of private companies and new public agencies (e.g., European Union Agency for Cybersecurity/ENISA) (Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023), but also an indirect political approach via rules in, for instance, law enforcement (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023). The special issue shows that the RSS has gained the strongest foothold in these digital security domains.

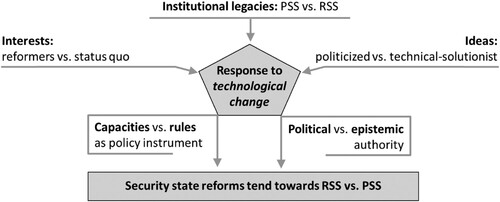

Drivers of and constraints on security state reforms

While the individual contributions to this special issue point to numerous specific drivers and constraints of the RSS in their respective case studies, this section outlines a broad framework of preliminary theoretical conjectures that help the individual contributions to explain the reforms to which security states have been subject in general, and the emergence of RSSs in particular. We consider technological change an important driver of transformations in prevailing foundations of authority and policy instruments. However, public and private actors in Europe’s multi-level politics may interpret, (re)construct and politically channel this technology-driven demand for security state reform in different ways. To capture this variation, we highlight three generic explanations that have been productively applied in numerous analyses of great political transformations: interests, institutions, and ideas (Hall, Citation1997; Hay, Citation2004; Majone, Citation1997; Thatcher & Stone Sweet, Citation2002). We translate each of these broad categories into more specific conjectures with regard to the conditions that have enabled or constrained the rise of the RSS in Europe, and we report key findings on each theoretical conjecture.

Technological change has historically challenged existing patterns of how to provide security (Bode & Huelss, Citation2018; Horowitz, Citation2010; Kelemen & McNamara, Citation2022; Weiss, Citation2018). It creates a demand for security state reform. Ceteris paribus, technological innovation increases the relevance of epistemic authority in policy-making. For example, the advance of information technologies has created an enhanced demand for technical expertise in European security states (Dunn Cavelty & Wenger, Citation2019; Weiss & Jankauskas, Citation2019). When national or supranational political actors are responsible for, but hardly capable of, mitigating threats arising from technological innovation, they will empower more competent experts (Abbott et al., Citation2020), as several contributions underline (e.g., Bode & Huelss, Citation2023; Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023). They may build expertise inside the security state (Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023), or enlist expertise and skills from outside the bureaucratic apparatus (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023).

However, which understandings and narratives regarding technological change prevail, who counts as competent, and which policy instruments are regarded as adequate for managing technological innovation is not exclusively imposed by material pressures. For instance, digitalization clearly poses new challenges to EU security actors, but it is far from clear what exactly these challenges are and which actors and instruments are best suited – and legitimated – to address them (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023). The more specific political response depends on actors’ interests, the legacies of existing institutions, as well as dominant ideas and practices (Mügge, Citation2023; Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Bode & Huelss, Citation2023; see Thatcher & Stone Sweet, Citation2002).

First, the interests of the actors involved and thus the distributive struggles that result from them directly shape the supply process in security state reform (Moe, Citation2019; Weiss, Citation2019). As different types of security state entail different winners and losers, we expect these actors to fight for the realization of their varying preferences regarding the foundations of the security state’s authority and the policy instruments it uses. Reformers who expect to profit will push for changes in line with their interests. Yet they may face resistance from defenders of the status quo, who seek to constrain or redirect change (Schilde, Citation2017). All existing security states will have generated vested interests in the status quo (Lake, Citation2010, p. 593), and different groups of actors will push for different designs of the security state that are conducive to their respective economic or political interests (Hoeffler, Citation2012). Distributive power bargaining between reformers and those with vested interests will shape the evolving nature of the security state. The framework’s interest-based conjecture argues that reform towards the establishment of an RSS (PSS) will materialize, if the bargaining power of prospective RSS (PSS) winners is superior to the bargaining power of prospective RSS (PSS) losers.

Several contributions find some evidence for this conjecture. Bode and Huelss (Citation2023) demonstrate that the interests of powerful business actors, who are viewed as indispensable experts in military applications of AI, both benefit from and further entrench the RSS in this domain. Their expertise and privileged access to European political decision-makers have allowed them to shape the terms of the EU’s regulation of military AI (see also Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023). In her analysis of the EDF’s policy instruments, Hoeffler (Citation2023) puts the struggles between member states and the Commission center stage, with the European Commission having pushed for EU ownership of military capabilities, in other words a reform toward a PSS. Member states, though, employed their superior bargaining power and resisted granting supranational competencies for military capacity-building at the EU level. As also evidenced by Dunn Cavelty & Smeets’s analysis of ENISA (Citation2023), the reform of security states typically reflects a struggle between different actors with varying interests and power endowments.

Second, the legacies of existing institutions shape the supply process of security state reform more indirectly. Different rules of the game create institutional complementarities to different security state reforms and stack the deck in favor of either reformers or status quo interests (Scharpf, Citation1997; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010; Rixen & Viola, Citation2015; Busemeyer & Thelen, Citation2020). Reforms are contingent on the security state’s prior authority foundations and capacity endowments (Abbott et al., Citation2020; Kruck, Citation2020). Ceteris paribus, politically legitimated security states with strong capacities are likely to build further capacities to address new security challenges under the leadership of politically accountable actors. By contrast, polities that have evolved as regulatory states (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2014, Citation2018; Majone, Citation1997) can be expected to be predisposed toward (more) rules as their default policy instruments and expertise as the foundation of their decision-making authority. The framework’s institutions-based conjecture therefore argues that reform towards the establishment of an RSS (PSS) will materialize, if deep-rooted institutional legacies within the security state are complementary to the authority foundations and policy instruments of the RSS (PSS).

Several contributions underline the plausibility of this conjecture. The different mixes of policy instruments in different fields of technology-driven security governance, which Sivan-Sevilla (Citation2023) investigates, reflect different institutional legacies. Even within the EU as a regulatory polity, the institutional legacies of different treaty provisions and EU agencies vary, creating more or less favorable conditions for the RSS or PSS. Similarly, Dunn Cavelty and Smeets (Citation2023) suggest that reliance on rules and epistemic authority is a longstanding, entrenched feature of the EU’s approach to cybersecurity. Nevertheless, capacities-based instruments and political authority-building have gradually been layered upon ENISA’s regulatory approach. This pattern of institutional legacies constraining radical shifts but still allowing for gradual reform via layering is evident in several contributions (e.g., Hoeffler, Citation2023; Schilde, Citation2023).

Third, knowledge politics and the constitution of meanings through discourses and practices shape the supply process of how to reform security states in indirect ways. The political response to technological change results from competing knowledge claims and normative contestations about who ought to govern security, on what legitimatory grounds, and by what means (Egloff & Dunn Cavelty, Citation2021). Different actors struggle over the proper definition of threats as well as adequate policy responses. When political actors manage to politicize issues, they constrain the stealthy and ‘quiet politics’ of expert technocracy by putting alternative political options on the public agenda (Culpepper, Citation2011; Morgan & Ibsen, Citation2021; Steffek, Citation2021). By contrast, where experts establish a technical-solutionist discourse, security decisions are depoliticized and suggest one sole – technical and often regulatory – policy response (Hansen & Nissenbaum, Citation2009, pp. 1166–67; Caramani, Citation2017). When the authority of non-state experts is accepted and these actors define proper responses to security challenges (Leander, Citation2005), they will, ceteris paribus, be more likely to promote indirect rules-based policy instruments. These, in turn, entrench the authoritative position of experts because, in indirect rules-based governance, expertise trumps political entitlement. By contrast, large-scale capacity-building requires mass support and political authority. The framework’s ideas-based conjecture argues that reform directed toward an RSS (PSS) will materialize if reformers manage to construct, through their discourses and practices, particular technical-solutionist (politicized) understandings of security which lend themselves to management through expert (political) rule and indirect rules-based (direct capacities-based) instruments.

Several contributions provide supporting evidence. For example, Obendiek and Seidl (Citation2023) argue that technical-solutionist ideas have promoted the epistemic authority of private tech businesses in law enforcement and the protection of critical digital infrastructures. These companies discursively (co-)create the foundations of their own empowerment by influencing how public actors perceive digital security problems and the competence of private experts to resolve them. Similarly, Bode and Huelss (Citation2023) show how the epistemic authority allocated to corporate expert actors entails a preference for indirect regulation as a policy instrument, while also shaping the substance of rule-making. The depoliticized discourses and practices of military AI as articulated and performed by technical actors promote both epistemic foundations of authority and rules-based instruments (see also Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023). Finally, Hoeffler’s contribution (Citation2023) attributes some of the EDF’s design characteristics to the Commission’s ideational move towards market interventionism, which encouraged it to pursue the adoption of positive state instruments.

In sum, the contributions to this special issue strongly suggest that technology-driven reforms of the security state are contingent on the interest constellation, the institutional legacies as well as the ideas, meanings, and practices of the actors involved. Most contributions highlight that interests, ideas, and institutions interact in various ways in shaping the reforms (Hoeffler, Citation2023; Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; see ).

Implications for the effectiveness and democratic legitimacy of European security policy-making

This special issue also studies the implications of the RSS for security policy-making. European rules may serve as regulatory ‘weapons’ to project power abroad (Mügge, Citation2023; Farrell & Newman, Citation2019), and they are also prone to generate unintended consequences extending beyond Europe (Leander et al., Citation2023). We therefore ask what the effects of the RSS are in Europe, and how the European RSS affects other countries and people around the world. How does the rise of the European RSS impact on the effectiveness and democratic legitimacy of security policy-making in Europe and beyond?

All contributions essentially agree on the political winners and losers in the RSS. Epistemic authority and rules-based instruments empower public and private experts as well as non-majoritarian institutions that are adept at regulating (Rimkutė & Mazepus, Citation2023; Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023; Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023; Hoeffler, Citation2023; see Majone, Citation1997; Rimkutė, Citation2020). Moreover, indirect security governance frequently grants material and ideational power to corporate interests (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; Bode & Huelss, Citation2023; see Abbott et al., Citation2020; Leander, Citation2005; Weiss & Heinkelmann-Wild, Citation2020). Elected actors and institutions, which base their authority on political entitlement and procedural legitimacy, lose power relative to experts and corporate interests.

Less straightforward is what follows from these power-distributional implications for the effectiveness and democratic legitimacy of security policy-making in Europe and beyond. In our conception, effectiveness refers to the achievement of security goals and the mitigation of security problems, i.e., the performance of the security state. Democratic legitimacy means the perceived appropriateness of policy-making processes, i.e., the acceptance of the security state institutions (polity legitimacy) and of their specific outputs (policy legitimacy), in the eyes of stakeholders and citizens inside and outside of Europe. Performance can promote acceptance; but in our terminology effectiveness and democratic legitimacy are conceptually distinct and they do not necessarily go hand in hand empirically. Overall, the record of the RSS regarding the effectiveness and democratic legitimacy of security policy-making appears mixed at best. In contrast to early analyses of the regulatory state in other issue areas (Majone, Citation1994, Citation1997), the regulatory security state does not emerge as a panacea to improve the effectiveness and democratic legitimacy of European security policy-making. Its effectiveness varies considerably; several articles even point out negative effects on the democratic legitimacy of security politics.

Any reform of security states will come with promises of a more effective provision of security. The contributions find ample evidence that proponents of the European RSS justify expertise-based regulation on the basis of its superior performance. This is particularly pronounced in fields marked by technological innovation, where experts and businesses emphasize their unique knowledge and skills that enable them to find advanced technical solutions to security problems, while political actors seem prone to buy into this narrative of expert governance improving policy performance (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; Bode & Huelss, Citation2023; Dunn Cavelty & Smeets, Citation2023). As scholarship on the privatization of security has demonstrated, however, promises of superior effectiveness often fail to materialize or are contingent on demanding conditions in international security (Carr, Citation2016; Kruck, Citation2018; Leander, Citation2013; Weiss & Jankauskas, Citation2019).

Extensive involvement of tech companies has, for instance, constrained more effective regulation of military AI applications by the EU. The companies in question fear stringent AI regulation might harm their future business activities (Bode & Huelss, Citation2023). They have also succeeded in casting themselves as competent problem-solvers in law enforcement and the build-up of digital clouds, while their actual performance has often not lived up to the hype (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023). The more entrenched experts and the ideational power of firms become, the more the RSS responds to performance deficits by revising rules rather than moving toward positive capacity-building. As a result, failures paradoxically tend to further entrench private authority and the rules-based co-provision of security rather than leading to their repudiation (Leander et al., Citation2023; Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; see Kruck, Citation2016, Citation2020; Moe, Citation2019). In other words, the empowerment of experts and corporate actors frequently goes along with political actors’ buying into the ‘meaning-generating techno-solutionist agenda dominated by constituted experts’ (Bode & Huelss, Citation2023): they are passively deferring to experts’ judgment rather than actively regulating and controlling them.

As Genschel and Jachtenfuchs (Citation2023) point out, it seems that the effectiveness of regulation depends on public actors’ possession of some residual capacity, if only to ‘incentivize compliance and/or to sanction non-compliance’ with their rules. ‘The regulatory state cannot “steer” without a minimum capacity to “row”’ (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2023, p. 1450). By contrast, Schilde’s analysis of how EU regulations successfully shaped the risk calculus of defence firms (Schilde, Citation2023) suggests a more positive role for the RSS. The European RSS has managed to decrease defence firms’ perceptions of future market risk and thus incentivized them to spend more of their internal resources on R&D. The European RSS thereby contributes to more efficient technological innovation in the defence industry while spending less public money on military R&D. The record of the RSS’s effectiveness is thus mixed.

Second, the RSS also has implications for the democratic legitimacy of security policy-making. There is a long-standing debate on whether effective regulatory policies based on expertise can guarantee the legitimacy of European policy-making or whether the empowerment of experts at the expense of political accountability erodes it (Keohane et al., Citation2009; Scharpf, Citation1999). Rimkutė & Mazepus (Citation2023) study how non-majoritarian institutions, in this instance the European Medicines Agency (EMA), are legitimized. They find that the EMA is regarded as a highly legitimate agency and that disapproval by national-level politicians and citizens does not undermine its epistemic authority in the eyes of local decision-makers. This suggests that, at least in the field of vaccines safety, expertise is a robust source of legitimacy for European policy-making. Things look less bright for the EU’s democratic legitimacy in regulating military applications of AI (see Bode & Huelss, Citation2023), as the influential epistemic authority of corporate actors has shaped and constrained EU regulation in ways that threaten to undermine its democratic legitimacy in this field.

EU regulatory governance schemes that rely on self- and co-regulation by tech companies can have detrimental implications for the enforcement of rule-of-law standards in European societies (Obendiek & Seidl, Citation2023; Sivan-Sevilla, Citation2023) and beyond. Leander et al. (Citation2023) show that the ‘ripples’ of European rules imposed on platform companies also lead to unintended consequences for digital democratic processes in the Global South. European rules and the powerful position of online services providers, such as Facebook, have had detrimental effects for the human security of individuals and the democratic process in Brazil (Leander et al., Citation2023). These effects reverberated back to the EU, as they ran counter to its own ambitions of promoting digital democracy.

These findings highlight that the European RSS is consequential: Far from being a marginal development at the fringes of European security policy-making, the RSS profoundly matters for the content, effectiveness and democratic legitimacy of policies in various key fields of security. European rules produce effects globally (Mügge, Citation2023). However, these effects are not always the desired or desirable ones; there may be unintended and negative consequences of these rules even beyond the addressees in Europe (Leander et al., Citation2023). Our empirical claim that for the past decades the European RSS has been on the rise and has taken root in many fields of European security should not be equated with a normative assessment that this is necessarily an effective and legitimate way of providing security. We do not advocate for the RSS here. The struggles of member states and the EU to muster the capacities for a strong response to the Russian aggression in Ukraine speak volumes of the contingencies and liabilities that follow from a heavy reliance on RSS macro-institutions in European approaches to governing security in the twenty-first century. Accounts of how ill prepared Europe has been, as of 2022, in military and defence issues, are incomplete if they ignore the legacies of decades of European RSS-building, which have entailed a neglect for capacity-building and the political legitimation of European security. Thus, precisely because its implications are consequential but ambivalent, the RSS warrants further analytical scrutiny. In the face of current aspirations to move towards more capacity-building, and thus a PSS, on national or even supranational levels in Europe, the European RSS will likely change but it will not simply wane. Rather, if the analyses of this special issue are correct, the RSS will mobilize its many vested supporters and shape the politics and trajectories of European security state reforms in the future (Moe, Citation2019; Weiss, Citation2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank, first of all, Berthold Rittberger, Jeremy Richardson, all the contributors to this special issue, as well as three anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments on earlier versions of this introduction. In addition, we are highly grateful to Felix Biermann, Michael Blauberger, Tim Heinkelmann-Wild, Hugo Meijer, Katharina Meissner, Chiara Ruffa, Andrea Schneiker, Bernhard Zangl, Eva Ziegler, the participants of panels at the Academic Convention of the German Political Science Association (DVPW, online, 2021), the 11th Biennial Conference of the SGEU in the ECPR (Rome, 2022), the Annual Conference of the European Initiative for Security Studies (Berlin, 2022), the Convention of the Political Economy Section of the DVPW (Berlin, 2022), the colloquium of the DVPW’s Foreign and Security Policy Group (online, 2021) as well as research colloquia in Munich, Salzburg and Odense for their great feedback. Kathrin Will, Aliaa Aly, Maya von Ahnen and Simon Zemp provided excellent research assistance. We gratefully acknowledge generous workshop funding from the Fritz Thyssen Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andreas Kruck

Andreas Kruck is a senior lecturer in Global Governance and Public Policy at the LMU Munich.

Moritz Weiss

Moritz Weiss is a senior lecturer in International Relations at the LMU Munich.

Notes

1 Some scholars of regulatory governance adopt a narrower understanding of rules as confined to ‘bureaucratic and administrative rulemaking’ (Levi-Faur, Citation2011, p. 6; Koop & Lodge, Citation2017).

2 We may ask whether a particular polity in toto is predominantly an RSS or a PSS. Yet, more frequently, contributors study whether a polity is an RSS or a PSS with regard to a specific sector of security. A sovereign state or the EU can be an RSS in one policy field, but a PSS in another.

References

- Abbott, K. W., Genschel, P., Snidal, D., & Zangl, B. (Eds.). (2020). The governor's dilemma: Indirect governance beyond principals and agents. Oxford University Press.

- Abbott, K. W., Levi-Faur, D., & Snidal, D. (2017). Theorizing regulatory intermediaries: The RIT model. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 670(1), 14–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216688272

- Bellanova, R., Carrapico, H., & Duez, D. (2022). Digital/sovereignty and European security integration: An introduction. European Security, 31(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2022.2101887

- Benish, A., & Levi-Faur, D. (2020). The expansion of regulation in welfare governance. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 691(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220949230

- Blauberger, M., & Weiss, M. (2013). ‘If you can't beat me, join me!’: How the commission pushed and pulled member states into legislating defence procurement. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(8), 1120–1138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.781783

- Bode, I., & Huelss, H. (2018). Autonomous weapons systems and changing norms in international relations. Review of International Studies, 44(3), 393–413. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210517000614

- Bode, I., & Huelss, H. (2023). Constructing expertise: The front- and back-door regulation of AI’s military applications in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1230–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174169

- Börzel, T. A., & Zürn, M. (2021). Contestations of the liberal international order: From liberal multilateralism to postnational liberalism. International Organization, 75(2), 282–305. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000570

- Bruin, E. de. (2020). Mapping coercive institutions: The State Security Forces dataset, 1960–2010. Journal of Peace Research, 58(2), 315–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320913089

- Busemeyer, M., & Thelen, K. (2020). Institutional sources of business power. World Politics, 72(3), 448–480. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004388712000009X

- Caramani, D. (2017). Will vs. Reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government. American Political Science Review, 111(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000538

- Carr, M. (2016). Public-private partnerships in national cyber-security strategies. International Affairs, 92(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12504

- Carrapico, H., & Barrinha, A. (2017). The EU as a coherent (cyber)security actor? Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(6), 1254–1272. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12575

- Council of the European Union. (2022a). Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/338. Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri = uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2022.060.01.0001.01.ENG&toc = OJ%3AL%3A2022%3A060%3ATOC.

- Council of the European Union. (2022b). Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/339. Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri = uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2022.061.01.0001.01.ENG&toc = OJ%3AL%3A2022%3A061%3ATOC.

- Csernatoni, R. (2022). The EU’s hegemonic imaginaries: From European strategic autonomy in defence to technological sovereignty. European Security, 31(3), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2022.2103370

- Culpepper, P. (2011). Quiet politics and business power: Corporate control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- Der Spiegel. (2022). Rheinmetall baut Munitionsfabriken in Deutschland aus. Spiegel Online, 15 December 2022, https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/rheinmetall-baut-munitionsfabriken-in-deutschland-aus-a-cdc0abb0-6160-4d5a-a478-865b38b7e7be.

- Dunn Cavelty, M., & Smeets, M. (2023). Regulatory cybersecurity governance in the making: The formation of ENISA and its struggle for epistemic authority. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1330–1352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2173274

- Dunn Cavelty, M., & Wenger, A. (2019). Cyber security meets security politics: Complex technology, fragmented politics, and networked science. Contemporary Security Policy, 41(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1678855

- Egloff, F. J., & Dunn Cavelty, M. (2021). Attribution and knowledge creation assemblages in cybersecurity politics. Journal of Cybersecurity, 7(1), https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyab002

- Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, M. (2022). The anachronism of bellicist state-building. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(12), 1901–1915. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141825

- Erickson, J. (2013). Market imperative meets normative power: Human rights and European arms transfer policy. European Journal of International Relations, 19(2), 209–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066111415883

- Erickson, J. (2018). Dangerous trade: Arms exports, human rights, and international reputation. Columbia University Press.

- Esterling, K. (2004). The political economy of expertise. University of Michigan Press.

- Farrand, B., & Carrapico, H. (2022). Digital sovereignty and taking back control: From regulatory capitalism to regulatory mercantilism in EU cybersecurity. European Security, 31(3), 435–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2022.2102896

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2019). Weaponized interdependence: How global economic networks shape state coercion. International Security, 44(1), 42–79. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00351

- Freudlsperger, C., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2022). Transboundary crises and political development: Why war is not necessary for European state-building. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(12), 1871–1884. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141822

- Genschel, P. (2022). Bellicist integration? The war in Ukraine, the European Union and core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(12), 1885–1900. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141823

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (Eds.). (2014). Beyond the regulatory polity? The European integration of core state powers. Oxford University Press.

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2018). From market integration to core state powers: The Eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis, and integration theory. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(1), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12654

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2023). The security state in Europe: Regulatory or positive? Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1447–1457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174580

- Genschel, P., & Zangl, B. (2014). State transformations in OECD countries. Annual Review of Political Science, 17(1), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-061312-113943

- Gheciu, A., & Wohlforth, W. C. (2018). The future of security studies. In A. Gheciu & W. C. Wohlforth (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of international security (pp. 3–13). Oxford University Press.

- Guidi, M., Guardiancich, I., & Levi-Faur, D. (2020). Modes of regulatory governance: A political economy perspective. Governance, 33(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12479

- Haas, P. (1992). Introduction: Epistemic communities and international policy coordination. International Organization, 46(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300001442

- Hall, P. (1997). Institutions, interests and ideas in the comparative political economy of the industrialized nations. In M. Lichbach, & A. Zuckerman (Eds.), Comparative politics: Rationality, culture and structure (pp. 174–207). Cambridge University Press.

- Hansen, L., & Nissenbaum, H. (2009). Digital disaster, cyber security, and the Copenhagen School. International Studies Quarterly, 53(4), 1155–1175. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27735139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00572.x

- Haroche, P. (2020). Supranationalism strikes back: A neofunctionalist account of the European Defence Fund. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(6), 853–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1609570

- Hay, C. (2004). Ideas, interests and institutions in the comparative political economy of great transformations. Review of International Political Economy, 11(1), 204–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969229042000179811

- Hix, S. (1994). The study of the European Community: The challenge to comparative politics. West European Politics, 17(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389408424999

- Hix, S. (1999). The political system of the European Union. Palgrave.

- Hoeffler, C. (2012). European armament co-operation and the renewal of industrial policy motives. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(3), 435–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.640803

- Hoeffler, C. (2023). Beyond the regulatory state? The European Defence Fund and national military capacities. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1281–1304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174581

- Hofmann, S. C. (2013). European security in NATO’s shadow: Party ideologies and institution building. Cambridge University Press.

- Horowitz, M. (2010). The diffusion of military power: Causes and consequences for international politics. Princeton University Press.

- Jachtenfuchs, M. (2001). The governance approach to European integration. Journal of Common Market Studies, 39(2), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00287

- Jordana, J., & Levi-Faur, D. (2004). The politics of regulation: Examining regulatory institutions and instruments in the age of governance. Edward Elgar.

- Kelemen, R. D., & McNamara, K. R. (2022). State-building and the European Union: Markets, war, and Europe’s uneven political development. Comparative Political Studies, 55(6), 963–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140211047393

- Keohane, R. O., Macedo, S., & Moravcsik, A. (2009). Democracy-enhancing multilateralism. International Organization, 63(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818309090018

- Klaaren, J. (2021). The emergence of regulatory capitalism in Africa. Economy and Society, 50(1), 100–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2021.1841934

- Koop, C., & Lodge, M. (2017). What is regulation? An interdisciplinary concept analysis. Regulation and Governance, 11(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12094

- Kruck, A. (2014). Theorising the use of private military and security companies: A synthetic perspective. Journal of International Relations and Development, 17(1), 112–141. https://doi.org/10.1057/jird.2013.4

- Kruck, A. (2016). Resilient blunderers: Credit rating fiascos and rating agencies’ institutionalized status as private authorities. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(5), 753–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1127274

- Kruck, A. (2018). Private governance failures and their consequences. In A. Kruck, K. Oppermann, & A. Spencer (Eds.), Political mistakes and policy failures in international relations (pp. 123–144). Springer.

- Kruck, A. (2020). Governing private security companies: Politics, dependence, and control. In K. W. Abbott, B. Zangl, D. Snidal, & P. Genschel (Eds.), The governor's dilemma: Indirect governance beyond principals and agents (pp. 137–156). Oxford University Press.

- Kuhn, T., & Nicoli, F. (2020). Collective identities and integration of core state powers. Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12985

- Lake, D. A. (2010). Rightful rules: Authority, order, and the foundations of global governance. International Studies Quarterly, 54(3), 587–613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00601.x

- Lavenex, S., Serrano, O., & Büthe, T. (2021). Power transitions and the rise of the regulatory state: Global market governance in flux. Regulation and Governance, 15(3), 445–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12400

- Leander, A. (2005). The power to construct international security: On the significance of private military companies. Journal of International Studies, 33(3), 803–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298050330030601

- Leander, A. (ed.). (2013). Commercialising security in Europe: Political consequences for peace operations. Routledge.

- Leander, A., Gonzales, C., Lobato, L., & dos Santos Maia, P. (2023). Ripples and their returns: Tracing the regulatory security state from the EU to Brazil, back and beyond. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1379–1405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174583

- Levi-Faur, D. (2005). The global diffusion of regulatory capitalism. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 598(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716204272371

- Levi-Faur, D. (2011). Regulatory networks and regulatory agencification: Towards a single European regulatory space. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(6), 810–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.593309

- Levi-Faur, D. (2023). The regulatory security state as a risk state. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1458–1471. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174170

- Louis, M., & Maertens, L. (2021). Why international organizations hate politics: Depoliticizing the world. Routledge.

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (2010). A gradual theory of institutional change. In J. Mahoney & K. Thelen (Eds.), Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and power (pp. 1–37). Cambridge University Press.

- Majone, G. (1994). The rise of the regulatory state in Europe. West European Politics, 17(3), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389408425031

- Majone, G. (1997). From the positive to the regulatory state: Causes and consequences of changes in the mode of governance. Journal of Public Policy, 17(2), 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00003524

- Mathieu, E. (2016). Regulatory delegation in the European Union: Networks, committees and agencies. Routledge.

- McNamara, K. R., & Kelemen, R. D. (2022). Seeing Europe like a state. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(12), 1916–1927. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141826

- Mérand, F. (2008). European defence policy: Beyond the nation state. Oxford University Press.

- Moe, T. M. (2019). The politics of institutional reform: Katrina, education, and the second face of power. Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan, G., & Ibsen, C. (2021). Quiet politics and the power of business: New perspectives in an era of noisy politics. Politics & Society, 49(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329220985749

- Mügge, D. (2023). The securitization of the EU’s digital tech regulation. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1431–1446. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2171090

- Neumann, I. B., & Sending, O. J. (2018). Expertise and practice: The evolving relationship between the study and practice of security. In A. Gheciu, & W. C. Wohlforth (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of international security (pp. 29–40). Oxford University Press.

- Obendiek, A., & Seidl, T. (2023). The (False) promise of solutionism: Ideational business power and the construction of epistemic authority in digital security governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1305–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2172060

- Paul, T. V., & Ripsman, N. (2010). Globalization and the national security state. Oxford University Press.

- Rimkutė, D. (2020). Building organizational reputation in the European regulatory state. Governance, 33(2), 385–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12438

- Rimkutė, D., & Mazepus, H. (2023). A widening authority–legitimacy gap in EU regulatory governance? An experimental study of the European Medicines Agency’s legitimacy in health security regulation. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1406–1430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2171091

- Ripsman, N., & Paul, T. V. (2010). Globalization and the national security state. Oxford University Press.

- Rittberger, B., & Wonka, A. (2011). Introduction: Agency governance in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(6), 780–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.593356

- Rixen, T., & Viola, L. A. (2015). Putting path dependence in its place: Toward a taxonomy of institutional change. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 27(2), 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951629814531667

- Scharpf, F. W. (1997). Games real actors play: Actor-centered institutionalism in policy research. Westview Press.

- Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Regieren in Europa: Effektiv und demokratisch? Campus.

- Schilde, K. (2017). The political economy of European security. Cambridge University Press.

- Schilde, K. (2023). Weaponising Europe? Rule-makers and rule-takers in in the EU security state. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1255–1280. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2174582

- Sivan-Sevilla, I. (2023). Supranational security states for national security problems: Governing by rules and capacities in technology-driven European security spaces. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(7), 1353–1378. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2172063

- Slayton, R., & Clark-Ginsberg, A. (2018). Beyond regulatory capture: Coproducing expertise for critical infrastructure protection. Regulation and Governance, 12(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12168

- Steffek, J. (2021). International organization as technocratic utopia. Oxford University Press.

- Thatcher, M., & Stone Sweet, A. (2002). Theory and practice of delegation to non-majoritarian institutions. West European Politics, 25(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/713601583

- Tilly, C. (1985). War making and state making as organized crime. In P. B. Evans, D. Rueschemeyer, & T. Skocpol (Eds.), Bringing the state back in (pp. 169–191). Cambridge University Press.

- Vogel, S. K. (1996). Freer markets, more rules: Regulatory reform in advanced industrial countries. Cornell University Press.

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society. University of California Press.

- Weiss, M. (2018). How to become a first mover? Mechanisms of military innovation and the development of drones. European Journal of International Security, 3(2), 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2017.15

- Weiss, M. (2019). From wealth to power? The failure of layered reforms in India’s defense sector. Journal of Global Security Studies, 4(4), 560–578. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz036

- Weiss, M., & Biermann, F. (2021a). Cyberspace and the protection of critical national infrastructure. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 1–18. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2021.1905530

- Weiss, M., & Biermann, F. (2021b). Networked politics and the supply of European defence integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 29, 910–931. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1916057

- Weiss, M., & Heinkelmann-Wild, T. (2020). Disarmed principals: Institutional resilience and the non-enforcement of delegation. European Political Science Review, 12(4), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000181

- Weiss, M., & Jankauskas, V. (2019). Securing cyberspace: How states design governance arrangements. Governance, 32(2), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12368

- Wolfers, A. (1962). Discord and collaboration: Essays on international politics. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Zürn, M. (2018). A theory of global governance: Authority, legitimacy, and contestation. Oxford University Press.