ABSTRACT

Research on political representation suggests that legislative activity is influenced by governing parties’ policy emphases in their election campaigns. We argue that populist governments are an exception as they may find it difficult to draft and implement laws on an issue even if it is salient to them. The anti-elitism, people-centrism, and Manichean-discourse nature of populist party platforms significantly alters their ability to legislate on their campaign issues. We test this claim using data on the saliency of governments’ immigration policies in their election campaigns and subsequent legislation on immigration. The empirical analysis is based on 14 democratic states from 1998 to 2013. The results support the theory that populist governments will exhibit a relatively weak relationship between their issue emphases in election campaigns and the number of policies they enact on immigration. This research has important implications for our understanding of populism, political representation, and immigration policy.

Government legislation in democracies tends to respond to public opinion (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2017; Bromley-Trujillo & Poe, Citation2020; Erikson et al., Citation2002; Kang & Powell, Citation2010; Schaffer et al., Citation2022; Soroka & Wlezien, Citation2010). The core mechanism explaining this pattern is that democratic policymakers can be removed more easily from power due to, e.g., regular elections, if they do not meet their constituents’ needs (Dahl, Citation1971). Hence, governing political parties in democracies have incentives to enact policies that satisfy voters’ interests (Anderson et al., Citation2017; see also Breunig et al., Citation2012). A crucial linkage in this translation of citizen preferences into policy is the pledge-fulfillment nexus in which governing parties carry out the promises that they campaigned with during elections. Numerous studies on pledge fulfilment provide a generally positive outlook on this aspect of substantive democratic representation (see, e.g., Adhikari et al., Citation2022; Bara, Citation2005; Böhmelt & Ezrow, Citation2022; Carson et al., Citation2019; Dassonneville et al., Citation2021; Duval & Pétry, Citation2019; Elling, Citation1979; Kennedy et al., Citation2021; Matthieß, Citation2020; Naurin, Citation2009, Citation2011; Naurin et al., Citation2019; Naurin & Thomson, Citation2020; Thomson, Citation1999; Thomson et al., Citation2017; Vodová, Citation2021; Werner, Citation2019). On balance, parties follow through on their campaign promises. This is a positive finding for scholars of representative democracy and advocates of the responsible party model of democracy (e.g., Keman, Citation2002) in that citizens’ voices are represented in elections, and then they influence the design and implementation of policy.

Various constraints may nevertheless work against a strong link between legislative action and what parties have campaigned on before elections (Lutz, Citation2019, Citation2021; see also Böhmelt & Ezrow, Citation2022; Ezrow et al., Citation2020, Citation2023; Kennedy et al., Citation2021). The following research contributes to this debate as we examine whether populist governments, i.e., governing coalitions in which populist parties participate, pursue legislative action on an issue they emphasised during their electoral campaigns. That is, our argument focuses on how salience in governing populist parties’ manifestos influences the number of policies that are subsequently implemented after they form a government. In particular, we explore this process of how campaign emphases translate into legislative activity with respect to immigration policies (see Abou-Chadi, Citation2016; Böhmelt, Citation2021b; Helbling & Kalkum, Citation2018; Money, Citation2010), a core aspect of many populist platforms. Our conclusions hold implications for our understanding of policymaking of well-known populist governments such as those associated with Donald Trump in the United States or Viktor Orbán in Hungary by showing that these governments can face unique difficulties in following through with legislative action on what their campaigns have emphasised.

Our argument is that populist governments might find it challenging to translate their electoral promises into legislative action as populists confront tradeoffs between maintaining their anti-elite postures and effectively addressing national problems. That is, populists in power face unique and essentially irreconcilable tradeoffs between governing effectively, on one hand, and maintaining the anti-elite posture that endears them to their core supporters, on the other hand. These cross-pressures render governing populist parties exceptionally susceptible to electoral reversals: if populists govern conventionally by cooperating with existing elites in the system, they undercut their brand as a disruptive force and, thereby, alienate their core supporters. Yet, if populists refuse to cooperate with cabinet partners and bureaucrats while ignoring expert advice (see also Böhmelt, Citation2021a; Heinisch, Citation2003), they fail to successfully advance their own policy agenda, which incurs retrospective punishment by voters. We offer a comparative analysis across 14 Western democracies across 43 elections from 1998 to 2013 that examines how salience in manifesto pledges translates into legislative action in the context of immigration (see Abou-Chadi, Citation2016; Böhmelt, Citation2021b; Helbling & Kalkum, Citation2018; Money, Citation2010).

Our study has direct implications for policymaking on migration. The movement of people across borders has risen significantly over the last few decades, and migration has become one of the most salient political issues (Böhmelt, Citation2021b). Due to its scale, international migration has become a ‘fundamental driver of social, economic, and political change’ worldwide (Cornelius & Rosenblum, Citation2005, p. 99). Examining whether governing parties that have spent more attention to immigration in their manifestos subsequently pass more immigration-related legislation sheds new light on what we know of the drivers behind migration policies.Footnote1

More generally, we gain new insights into democratic representation and policymaking. In elections, parties present a bundle of policies that citizens may find attractive. Presumably, parties would remain committed to their electoral platforms (see Anderson et al., Citation2017; Kang & Powell, Citation2010; Soroka & Wlezien, Citation2010), but our results stress that populists in government may find this difficult, at least in terms of enacting policies that reflect the relative salience of policies in their election manifestos.

Finally, by demonstrating that populist governments do not engage in as much legislative activity on immigration as predicted by their election platforms, the findings improve our general understanding of populism (e.g., Wuttke et al., Citation2020) and how populist governments do, or do not, function. Adams et al. (Citation2022), for example, have identified a ‘backlash effect’ to populism: populist government policies are rejected by foreign political parties. Put differently, a focal party will distance its policies from governing populists abroad. Our results suggest that the explanation for parties’ policy distancing is due to populists’ inability to govern. In turn, with regards to election outcomes for populist governments, parties should be committed to their electoral platforms once in power. This is driven by an inherent self-interest as, presumably, this is likely to raise the chances to do well in upcoming elections. However, if populists are unable to deliver on their electoral campaigns and, thus, alienate those voters that just brought them into power, populists are unlikely to stay in power in the long run (see also Adams et al., Citation2022; Afonso, Citation2015; Heinisch, Citation2003; Walter, Citation2021).

Populist governments and their attention to immigration policy

There is widespread interest in populism across the social sciences (e.g., Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Bos et al., Citation2010; Busby et al., Citation2019; Caramani, Citation2017; Castanho Silva et al., Citation2018; Citation2020; De la Torre, Citation2014; Hameleers et al., Citation2017; Hobolt, Citation2016; Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016; Rooduijn, Citation2019; Rooduijn et al., Citation2016; Van Hauwaert et al., Citation2020; Wuttke et al., Citation2020). Populism influences a wide range of political attitudes and behaviour (Doyle, Citation2011; Huber, Citation2020; Panizza, Citation2000; Roberts, Citation2007; Weyland, Citation2003). For example, populism has been shown to have crucial implications for environmental politics (Böhmelt, Citation2021a), party politics (Adams et al., Citation2022), polarisation (Rooduijn et al., Citation2016), and liberal democracy more generally (Huber & Schimpf, Citation2016). Indeed, the commonly used definition of populism suggests that there will be significant consequences for the way democracy works when populist parties come to power. According to Mudde (Citation2004:, p. 543), populism can be defined ideationally as ‘a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, the people and the corrupt elite, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.’ To this end, populism is thus not exclusively linked to a specific political orientation, e.g., left-wing and right-wing movements (Akkerman et al., Citation2017; Forchtner & Kølvraa, Citation2015; Huber & Ruth, Citation2017; Huber & Schimpf, Citation2017; Otjes & Louwerse, Citation2015; Rooduijn & Akkerman, Citation2017; Taggart, Citation2002).Footnote2 Three main criteria characterise the core of the definition of populism: anti-elitism, people-centrism, and a Manichean discourse that actively proclaims a moral struggle between ‘good people’ and ‘the elite’ (Hawkins, Citation2003; Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018; Mudde, Citation2004; see also Canovan, Citation1981; Huber & Schimpf, Citation2016). Populism therefore claims to pursue a new morale (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2012, p. 8) as it opposes the establishment and ‘corrupt elites’ – the actors generally seen at the centre of political decision-making and power, including the government (Hay & Stoker, Citation2009; Huber, Citation2020). Against this background, populists often argue that representative democracy does not meet their ideological expectations of expressing the will of the people (Mény & Surel, Citation2002) and, as a result, the very definition of populism proposes that populists in power may be less effective at governing because they are opposed to working with policy elites.

Research on representative democracy and public policy also acknowledges difficulties for populist parties when they govern (for an overview, see, e.g., Werner & Geibler, Citation2019). For example, Riera and Pastor (Citation2022) argue that populist governing parties will be electorally punished if they enter the executive as junior coalition partners. Adams et al. (Citation2022) similarly claim that populists’ ideational characteristics make them electorally vulnerable after assuming governmental power, so much so that political parties abroad will distance their policy positions from governing populists. De Sousa et al. (Citation2021) build their theory on the view that populist governments produce more moderate policies than promised in their manifestos, potentially leading to a gap in pledge fulfilment. This echoes Akkerman’s (Citation2012) research on immigration policies or Vercesi’s (Citation2019) study of the Italian populist government under Giuseppe Conte, which was more moderate than their campaign policies suggested.

Regardless of whether parties are policy, office, or vote seeking, the policy emphasis in electoral campaigns should strongly influence policy output (Müller & Strøm, Citation1999; see also Böhmelt et al., Citation2016, Citation2017; Downs, Citation1957). Most importantly, this maximises the chances of staying in power (Anderson et al., Citation2017; Dahl, Citation1971). Karreth et al. (Citation2013) show that when parties moderate their positions by moving away from their core supporters, they lose votes under longer time horizons. Hence, this means that short-term changes in policy are met with long-term reputational and vote losses (see also Alvarez, Citation1998). Correspondingly, while in government, parties that are policy, office, or vote seeking, ceteris paribus, are expected to emphasise the same issues they focused on in their campaign.

As indicated above, there is plenty of empirical evidence for the responsiveness of democratic governments to voters’ demands (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2017; Bromley-Trujillo & Poe, Citation2020; Erikson et al., Citation2002; Ezrow et al., Citation2023; Kang & Powell, Citation2010; Schaffer et al., Citation2022; Soroka & Wlezien, Citation2010); specifically, for the left-right dimension (McDonald & Budge, Citation2005), fiscal policies (Blais et al., Citation1993; Bräuninger, Citation2005), social policies (Hicks & Swank, Citation1992; Huber et al., Citation1993), and the environment (Knill et al., Citation2010; Lundquist, Citation2022; see also Anderson et al., Citation2017; Bakaki et al., Citation2020). With respect to immigration, governments are generally responsive to citizen demands and seek to keep their electoral promises (Böhmelt, Citation2021b; see also Böhmelt & Ezrow, Citation2022).Footnote3 Hence, the considerations raised above about parties’ reputational concerns and incentives for governing parties in democracies to follow through on what they emphasised during electoral campaigns lead us to a general expectation that legislative policy action will reflect governing parties’ policy saliency positions in their manifestos.

We do not question that populist parties have similar incentives and concerns. However, we contend that populist parties will have difficulties governing once they have gained power. This, in turn, likely leads to a gap between the issues on which they legislate and on which they campaigned. Populists’ programmes often promise the opposite of working within government; rather, they aim to disrupt governments and the ‘corrupt’ political elites that inhabit them. This adversarial stance towards elites will make it problematic for populists to enact any policies once in power.

Specifically, populist parties hold an anti-elite worldview that highlights the role of corrupt mainstream parties, government bureaucracies, and experts (Hawkins et al., Citation2019). The campaign policies of populists create problems with respect to working within the government bureaucracy or consulting expert advisors (Bauer & Becker, Citation2020; Lockwood, Citation2018). Akkerman et al. (Citation2016) evaluate the extent to which populist parties in different countries have adapted their policies and structures to look more ‘mainstream’ following electoral gains.Footnote4 But there is nevertheless evidence of considerable difficulty that populists face when working together with their mainstream coalition partners (Afonso, Citation2015; Heinisch, Citation2003). As a result, populists struggle to address important national problems (Böhmelt, Citation2021a) and to realise their policy goals (Akkerman, Citation2012). Furthermore, this also leads to complications for recruiting talented or experienced politicians into their ranks (Heinisch, Citation2003; Kriesi, Citation2014). Related, populists may not yet have embedded themselves in institutions like the civil service, which provides more technical expertise that helps to advance legislation while in government. If populist parties somehow overcome their anti-elitist stance to govern effectively, they will go against their other commitment to oppose the establishment (Krause & Wagner, Citation2019).

In total, clear tensions arise for populist parties when gaining office between their core policy stances and governing effectively, which will lead to a weaker connection between campaigns’ policy issue salience and legislative action. This motivates the following hypothesis:

Governing populist hypothesis

The relationship between the salience in manifestos and the number of policies implemented for immigration policy will be weaker for populist governments.

Research design

To empirically analyze the theoretical mechanisms and identify the postulated avenues of influence, we require three core components: a dependent variable capturing legislative action and, the government’s salience position on a policy issue during the electoral campaign, and an item on a government’s degree of populism. Combining all three elements is not without difficulty as, e.g., certain policies can be implemented by both rightist and leftist executives – the ‘issue-government link’ or match between policy implementation/scope and government preferences would not be clearly identified, making it less straightforward to test our theory.

We eventually address this issue by concentrating on one issue area, namely migration, and by employing recently released data on issue saliency in party manifestos (Lehmann & Zobel, Citation2018). We acknowledge the limitations about generalising our results beyond this issue area. Populist parties may make unrealistic pledges, perhaps due to existing international agreements on immigration and human rights, which means that they are unable to enact immigration policies. The pledges may also be more extreme than their coalition partners’ policies, also making them more difficult to sustain. These arguments suggest that policymaking may be less closely linked to the issue salience in manifestos for populist governments than in other issue areas for which they share more similar policy profiles to their mainstream coalition partners (e.g., the economy). While this latter set of arguments supports our central expectation, they also suggest we should be cautious about extrapolating these results to additional policy dimensions. Having said that, we analyze environmental policies (see Lundquist, Citation2022) in the appendix.

Still, on one hand, particularly right-wing populist parties arguably ‘own’ the immigration issue (e.g., Combei & Giannetti, Citation2020; see also Meguid, Citation2005, Citation2008), and if they are successful in gaining office, given the representative connections between citizen preferences and government policy, populist governments should have a strong mandate to implement their policies. A robust basis for their popularity will be their stance on immigration. Thus, our focus on immigration policies arguably constitutes a least-likely case to demonstrate the validity of our argument. We note that the additional analysis provided in the appendix for the environment supports the latter set of arguments – but we acknowledge that there may be issues with generalising these arguments beyond immigration and the environment.Footnote5 On this basis, we proceed.

Our argument emphasises that the anti-elite stance of populist governments will lead them to face difficulties governing effectively – even on immigration. To capture executive populism, we use two different measures: one that is based on the Parties Variety and Organisation (V-Party) project (Lührmann et al., Citation2020), and the other item is from the Global Populism Database (GPD; Hawkins et al., Citation2019). The final data set has the country/cabinet-year as the unit of analysis and comprises up to 14 democratic states across 43 elections in 1998–2013. In the following, we describe the corresponding variables as well as the methodology and control items of our analysis.

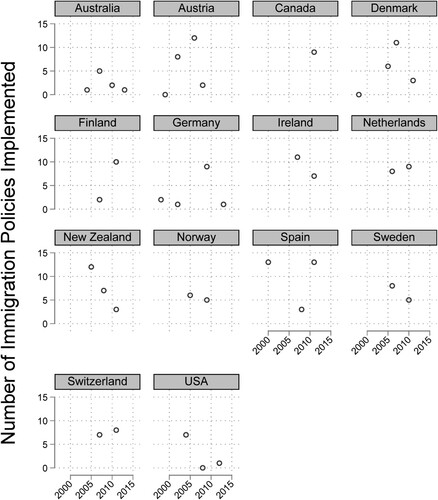

The dependent variable is taken from the Determinants of International Migration (DEMIG) Policy Database (Haas et al., Citation2014).Footnote6 While several data sets on migration policies and their implementation are available, the DEMIG data benefit from a larger spatial and temporal scope. The unit of analysis in the DEMIG data is an individual policy as such, and the data set concentrates on the changes in laws and regulations. To this end, for each entry in the data, DEMIG provides information on the policy area, the tool for implementation, the targeted migrant group, as well as the geographic origin of a targeted group.Footnote7 The outcome variable aggregates this information to reflect the number of immigration policy measures implemented per country/cabinet-year. As our argument applies to migration policies generally, and the empirical measures of party positions do not focus on the direction of policies (e.g., more/less restrictive) but saliency, we have little theoretical reason to distinguish between types of policies, e.g., more/less restrictive regulations or control mechanisms. Hence, for each country/cabinet-year, we sum up all new or changed migration policies enacted. gives an overview of this policy count variable: the dependent variable exhibits variation across countries as well as within countries over time.

In light of this operationalisation of the dependent variable, we estimate parameters of a negative binomial regression model. In particular, the model is suitable for variables for which the variance exceeds the mean, which is the case here. We include country-fixed effects as well as a time trend. The former control for essentially any time-invariant, unobserved characteristics of states that may influence migration policymaking, although any time-invariant substantive predictor at this level of analysis cannot be included in the model. Most importantly, this setup generally mirrors a differences-in-differences approach for time-series cross-section data. In the words of Angrist and Pischke (Citation2009:, p. 227), ‘group-level omitted variables can be captured by group-level fixed effects, an approach that leads to the differences-in-differences (DiD) strategy.’ And indeed, ‘DiD is a version of fixed effects estimation using aggregate data’ (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2009, p. 228). The time trend addresses temporal dependencies, and we consider a temporally lagged dependent variable that controls for within-country temporal dependencies in the appendix. Finally, we cluster the standard errors at the country level to adjust them according to country-specific path dependencies and correlations.

With respect to explanatory variables, the focus is on the interaction between government positions and populism (see Brambor et al., Citation2006; Hainmueller et al., Citation2019). That is, our models comprise a variable on governing parties’ view on migration, an item on their degree of populism, and the product of the two to capture the multiplicative interaction term. This allows us to explore whether populism conditions these effects of governing parties’ attention to migration during their election campaigns on the number of migration policies while in office. We expect that populist governments are less likely to exhibit a strong relationship between the issue salience of immigration in their election campaigns and their subsequent policymaking on this issue. We facilitate interpretation by calculating and presenting substantive quantities of interest (see Brambor et al., Citation2006).

The first component of the interactive specification is then about governing parties’ immigration saliency positions. This variable combines information on political parties’ saliency position on immigration with data on government participation. The former relies on Lehmann and Zobel (Citation2018) whose data have two key advantages. First, the information is derived from manifestos to provide parties’ ‘unified and unfiltered’ immigration positions for countries and time points not covered in expert surveys and media studies. Second, the data are based on crowd coding, which allows for a fast manual coding of political texts. According to Lehmann and Zobel’s (Citation2018) codebook, salience is calculated as the proportion of immigration and integration related quasi-sentences to the total number of quasi-sentences in party manifestos. This item thus varies between 0 and 100 percent for each party. The information on parties in government is based on Döring and Manow (Citation2012), who identified for each country/cabinet-year in our sample the parties that are participating in government. Combining the sources above, the variable Government Immigration Salience captures the government’s view on immigration salience, with saliency scores in Lehmann and Zobel (Citation2018) averaged across all parties in government. Inter-election years are interpolated linearly. Higher values stand for a more salient view on migration. We would expect this item – disregarding the interaction effect – to be positively signed and significant: simply, if migration is salient to the government, it will implement more policies.

The second component of the multiplicative interaction is about the government’s degree of populism. As indicated above, we use two different specifications. The first is based on the V-Party database (Lührmann et al., Citation2020). These data rely on expert surveys to assess parties’ populist positions, which focus on anti-elitism and people-centrism (Mudde, Citation2004).Footnote8 Official party documents are used for coding the data, e.g., election manifestos, press releases, official speeches, or interviews. The anti-elitism component is coded by the question ‘how important is anti-elite rhetoric for this party?’ on a scale from 0 to 4, with higher values standing for more anti-elitism. The people-centrism component can also receive values between 0 and 4 (higher values signify more people-centrism) and is based on: ‘[m]any parties and leaders make reference to the ‘people’, but only some party leaders describe the ordinary people specifically as a homogenous group and emphasise/claim that they are part of this group and represent it.’ Our final variable combines the two components in an index and receives values between 0 and 1, with higher values standing for more populist positions of parties. However, we concentrate on the degree of populism for governing parties, to make it consistent with the first variable of the interaction term, i.e., Government Immigration Salience. That is, we average populism scores across governing parties. To this end, the variable Government Populism considers the party of a single-party government or the party the Head of Government belongs to as well as junior partners, i.e., parties the Head of Government does not belong to, but one or more cabinet ministers do. In our sample, the variable ranges between 0 and 0.797, with New Zealand in 1998 (with the participation of the nationalist and populist New Zealand First party) scoring the maximum. Austria with the FPÖ’s participation in a coalition government (2000–2005, e.g., 0.434 in 2000) or the US under the Bush administration (2001–2009, e.g., 2008: 0.374) also score high on the variable Government Populism.

The alternative operationalisation of governmental populism does not focus on parties, but executive heads as such. The GPD (Hawkins et al., Citation2019) codes populist discourse for political leaders using textual analysis of political speeches.Footnote9 For each leader and term in office, quota sampling is used to identify and code four speeches: a campaign speech (usually the closing or announcement speech), a ribbon-cutting speech (marking a commemorative event with a small, domestic audience), an international speech (given before an audience of foreign nationals outside the country), and a famous speech (one widely circulated that represents the leader at his or her best). Our final GPD variable, Leader Populism, is the average populism score for each leader-year, while scores across the years of the same term in office do not vary. The item varies between 0 and 0.363 in our sample, with Spain between 2008 and 2011 under José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero’s government scoring the highest value.

Finally, we have compiled information on several other covariates, which control for alternative mechanisms that influence the implementation of migration policies (see also, e.g., Abou-Chadi, Citation2016; Cornelius & Rosenblum, Citation2005; Howard, Citation2010). First, there is Henisz’s (Citation2002) political constraints data set, which ‘estimates the feasibility of policy change […] it identifies the number of independent branches of government (executive, lower and upper legislative chambers) with veto power over policy change.’ Higher values stand for more political constraints and veto players, arguably making the implementation of new policies more difficult.

Second, we control for the economic circumstances (e.g., Böhmelt & Ezrow, Citation2022; Freeman, Citation1995, p. 886) in a country using data on income and unemployment. Both variables are taken from the World Bank Development Indicators. The log-transformed GDP per capita (in current US Dollars) is used, which is defined as the gross domestic product divided by midyear population. GDP is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. Unemployment is also included, which captures the unemployment in the form of its percent of the total labour force.

Finally, using the World Bank Development Indicators, we control for the log-transformed migrant-and-refugee population per capita. The World Bank defines international migrant and refugees as ‘the number of people born in a country other than that in which they live. It also includes refugees.’ summarises the descriptive statistics of the variables we have discussed in the research design.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Empirical results

Our empirical models are summarised in , which presents four estimations. Models 1–2 are based on the V-Party (Lührmann et al., Citation2020) indicator, Government Immigration Salience. The first model omits the control covariates and only focuses on the multiplicative interaction term. Models 3–4 are based on the populism variable from the GPD (Hawkins et al., Citation2019). Models 1–2 then provide some evidence for the Governing Populist Hypothesis: the variable Government Immigration Salience is positively signed and statistically significant. Setting Government Populism and the interaction term to 0 (i.e., government parties are not populist), executives that place a great deal of importance on migration implement more policies on that issue per year. For each unit increase in Government Immigration Salience, we observe about one additional migration policy per country/cabinet-year across Models 1–2. Again, the coefficient on Government Immigration Salience * Government Populism will provide a direct test of the theory.

Table 2. Immigration policies and immigration salience in governing parties’ election manifestos.

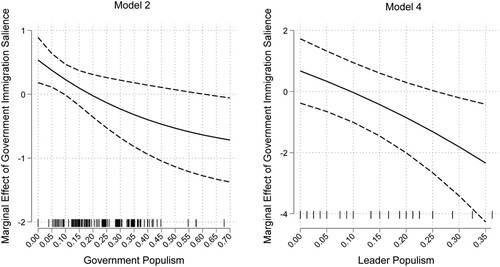

Indeed, Models 1–2 report negative effects on the interaction term, which suggests that more populist governments are likely to implement fewer policies – even if immigration is a salient issue to them. Interpreting the size of the effect of Government Immigration Salience * Government Populism is challenging and, thus, the left panel in presents marginal effects at the mean for Government Immigration Salience when setting Government Populism to specific values. According to this graph, there is a positive and significant marginal effect of Government Immigration Salience when holding the populism variable at a low level, i.e., between 0 and 0.1. Within that range, there is one additional immigration policy enacted by the government for every unit-increase in salience. The overall effect then becomes statistically insignificant until about a value of 0.6 on the V-Party populism variable: for largely populist governments, raising issue salience is actually associated with fewer policies implemented per year. Substantively, the marginal effect at the extreme populist value translates into two policies fewer per one-unit increase in Government Immigration Salience. These findings align with our argument: due to the inherent challenges in translating populist rhetoric to actual governmental action, populist governments will find it more difficult to actually implement what they emphasised during their campaigns, even if it is a policy issue as salient as immigration.

Figure 2. How populism shapes governments’ legislative action.

Notes. Dashed lines pertain to 90 percent confidence intervals; rug plots along horizontal axes show distribution of populism variables.

Models 3–4 further support this assessment. For these models, the estimations are based on the GPD (Hawkins et al., Citation2019) variable. While Government Immigration Salience is statistically insignificant, its interaction term with Leader Populism is again negatively signed and statistically significant at conventional levels. That is, even when using a different data set, which relies on a somewhat broader definition of populism, but is more narrowly defined to the extent that the focus is on leaders (rather than parties), our core finding is robust. The right panel in presents the substantive quantities of interest for Models 3–4 as we plot marginal effects at the mean for Government Immigration Salience when holding Leader Populism constant at certain values. The same negative trend as in the left panel can be observed. The overall effect is insignificant throughout most values of Leader Populism, but becomes statistically important once a threshold of 0.25 on the populism variable has been reached. For leaders scoring higher than that, their governments will also find it more difficult to implement policies for their most salient areas of interest: substantively, we can expect more than 5 fewer policies for each unit increase of Government Immigration Salience when an executive leader is a populist.

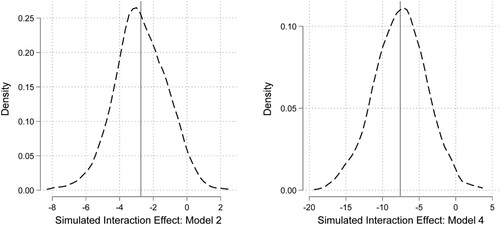

To assess the validity of this finding, we also simulate the coefficient of the interaction term either for Government Populism or Leader Populism 1,000 times using the method in King et al. (Citation2000). summarises the results: in the left panel, we simulate the interaction term of Model 2, the right panel is based on the estimation of Model 4. The mean value of the simulated number of policies in Model 2 is −2.812, i.e., about 2 fewer policies for every unit increase in Government Immigration Salience when setting Government Populism to 1. Moreover, out of these 1,000 simulations, only about 4 percent of simulations have a coefficient estimate of greater than or equal to 0. Coming to the right panel of , only about 1.5 percent of the 1,000 simulations are estimated to have an interaction term that is positively signed. The simulated average number of policies in Model 4 is at around 7 fewer policies when raising Government Immigration Salience by one unit, but holding Leader Populism constant at 1. Hence, there is robust evidence emphasising that the relationship between governments’ views on migration salience and their policymaking in this area is, in fact, negative and statistically significant when executives are more populist.

Figure 3. Simulated interaction effects.

Notes. Graph displays distribution of simulated interaction effects (N = 1,000 simulations); solid line stands for mean value of interaction effect.

In the appendix, we provide a series of additional models. First, we consider the inclusion of a temporally lagged dependent variable, a three-year moving average of legislative activity on migration, and three-year moving sum of migration policies.Footnote10 Second, we change the operationalisation of Government Immigration Salience in order to put a stronger emphasis on immigration (rather than integration) related quasi-sentences. Third, we control for economic globalisation – another economic indicator, which – unlike the ones used above – is located at the international/global level. Fourth, we estimate zero-inflated negative binomial regression models, which account for the non-random assignment of countries into migration policies more thoroughly. Fifth, the appendix includes models that control for the type of government, i.e., single-party versus coalition governing arrangements (i.e., governments with more than one political party), which addresses the possibility that our results are influenced by populist parties entering government as junior coalition partners. Sixth, we evaluate different configurations of populism populist government, by using different operationalizations of populist governments based on the minimum party populism score (within coalition); the maximum score; and a third measure that is based on the range of scores within coalition. Finally, using data from Lundquist (Citation2022), we explore populist governments’ manifesto salience and legislative action in the context of environmental politics. All these additional tests support our main finding and the corresponding empirical results discussed here: the salience of an issue in populist governing parties’ election campaigns is less likely to influence their policymaking on this issue.

Briefly discussing the control variables, the only consistent pattern across Models 1–4 is given for GDP per capita (log): we estimate a positive and significant effect. Countries with a higher income tend to implement more immigration policies per year. The underlying mechanism is probably related to state capacity, which is commonly proxied by income. That is, in order to implement policies, governments need a functioning state apparatus. An effective bureaucracy can take care of policy implementation and compliance monitoring, while these become more challenging if state capacity is not sufficiently developed. All other control variables are either insignificant or display inconsistent results in .

Conclusion

The spread of populism has received considerable attention from academics and the media (see, e.g., Kishishita & Yamagishi, Citation2021; Norris & Inglehart, Citation2019; Rooduijn et al., Citation2014; Vachudova, Citation2021). The contribution of this study is to show that when populists are successful in elections and take office, they are unable to match their level of policymaking with their campaign emphasis on certain policy issues. Empirically, we focus on immigration policies, a least-likely scenario for the validity of our theory as many populist parties claim to own the migration issue (e.g., Combei & Giannetti, Citation2020; see also Meguid, Citation2005, Citation2008). On one hand, seen through the lens of the pro-immigration perspective, our results may be viewed positively because they suggest that these governments are unsuccessful at enacting their restrictive migration policy stances. On the other hand, mandate theories of democracy suggest that parties should legislate what they campaigned on into policy. With respect to populist governments and migration policy, these governments have been unsuccessful.

Our work raises several interesting questions for future research. Our sample of democracies is limited in that we examine only established democracies. Newer democracies may not exhibit similar patterns. There are also questions that arise about what happens to populist governments after they take office. Do populists face difficulties because they quickly lose popular support after taking office due to compromise (Akkerman et al., Citation2016), or do these governments face strong backlash anti-populist responses (Moffitt, Citation2018)? One way forward to address these research questions would be to exploit more fine-grained polling data (see, e.g., Jennings & Wlezien, Citation2018).

There is also an issue that the difficulties populist governments face in governing will influence future voter turnout rates: when governments do not produce legislation in the areas that they campaign on, do citizens abstain in the next election? And what are the electoral consequences for populist governments that do not produce policies that would follow from their election campaigns? A preliminary expectation is that these governments will lose more votes, on average, than non-populist governments. Furthermore, there are several additional conditional effects worth exploring. Is the relationship we explore conditioned by the economy (Ezrow et al., Citation2020), federalism (Peters, Citation2016), bicameralism (Ezrow et al., Citation2023), or by a number of other institutional environments such as polarised contexts (e.g., McCarty et al., Citation2006)? Future research will examine additional conditions that influence the level of policymaking in a specific issue domain, based on the salience of that issue are during a government’s election campaign. Having said that, at least with regards to immigration policies, new data collection efforts are necessary as even the most comprehensive data sets available, including the DEMIG Policy Database (Haas et al., Citation2014) we rely on, are increasingly somewhat limited in their over-time coverage.Footnote11

The future studies described above notwithstanding, this research develops insights relating to populism, policymaking, and immigration policy. In particular, we analyze policymaking for populist governments on the issue of immigration, and our contribution is to show that these governments, compared to non-populist governments, implement fewer policies in this area than their election campaigns would suggest.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (96.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the journal’s editors, Jeremy Richardson and Berthold Rittberger, and the anonymous reviewers for the constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tobias Böhmelt

Tobias Böhmelt is Professor of Government at the University of Essex, Colchester, UK.

Lawrence Ezrow

Lawrence Ezrow is Professor of Government at the University of Essex, Colchester, UK.

Notes

1 In the appendix, we also explore this relationship for environmental policies (see Lundquist, Citation2022).

2 Our theoretical argument and empirical findings apply to right-wing and left-wing populists alike.

3 However, note Lutz (Citation2019, Citation2021) who concludes that governments do not implement their manifesto policies on immigration. He argues that the governing activity that might be directed to this representation ‘gap’ (between governing policy and election manifestos) is instead funnelled towards policy activity for domestic integration policies for immigrants on which they have more leeway to govern. The implication for our work is that if all governing parties have difficulty enacting policy on immigration, then governing populists must perform even worse on this measure of representation, i.e., it will be a conservative empirical test of our theory.

4 We note that it is plausible that if populist governments remain in power for several terms that they would then become more mainstream. There are too few observations in the data set to thoroughly evaluate this possibility.

5 Note that Adams et al. (Citation2022) find that political parties distancing their policies from governing populists extends across a whole range of issues, also including European integration, the economy, culture, and the broad left-right dimension. Our study corroborates these findings by suggesting that populist governments have difficulties enacting policies in the issue areas on which they campaign, and the studies taken together suggest that the findings extend to additional issue areas.

6 The codebook is available at: https://www.imi-n.org/files/data/demig-policy-codebook.pdf.

7 The policy area codes border and land control, legal entry and stay, exit, and integration policies. The policy-tool variable comprises the instrument used to implement a policy measure and has in total 28 codes, e.g., surveillance technology or work permits. The migrant-target variable identifies the migrant group targeted (e.g., low-skilled workers), whereas the geographical-origin variable includes the origin of the targeted migrant category (e.g., EU citizens).

8 According to the V-Party codebook (Lührmann et al., Citation2020, p. 24), elites are defined as ‘relatively small groups that have a greater say in society than others, for instance due to their political power, wealth or societal standing. The specific groups considered to be the elite may vary by country and even from party to party within the same country as do the terms used to describe them. In some cases, ‘elites’ can also refer to an international elite.’

9 The project, according to its codebook, ‘applies a technique known as holistic grading which was designed by educational psychologists to measure diffuse, latent aspects of texts such as tone, style, and quality of argument. The technique […] has coders apply an integer grade scale and a rubric to identify rough attributes of texts at each grade.’ Furthermore, ‘texts are initially assigned one of three scores: (2) A speech in this category is extremely populist and comes very close to the ideal populist discourse. Specifically, the speech expresses all or nearly all of the elements of ideal populist discourse and has few elements that would be considered non-populist; (1) a speech in this category includes strong, clearly populist elements but either does not use them consistently or tempers them by including non-populist elements. Thus, the discourse may have a romanticised notion of the people and the idea of a unified popular will (indeed, it must in order to be considered populist), but it avoids bellicose language or references to cosmic proportions or any particular enemy; and (0) a speech in this category uses few if any populist elements. Note that even if a speech expresses a Manichean worldview, it is not considered populist if it lacks some notion of a popular will.’

10 These analyses address the concern that previous governments may have already passed legislation on migration to pre-empt potential electoral gains for populist parties in future elections (see Akkerman, Citation2015; Lutz, Citation2019). There is evidence that previous legislative activity leads to fewer policies in the current year. The results also do not change the central substantive finding that we report.

11 The lack of data for the post-2013 period in our case is unlikely to be a concern, though. Considering cases such as Austria or Italy, where populist parties were part of the government post-2013 and found it indeed challenging to follow-up on their campaigns, we have little reason to believe different forces are at work.

References

- Abou-Chadi, T. (2016). Political and institutional determinants of immigration policies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(13), 2087–2110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1166938

- Adams, J., Böhmelt, T., Ezrow, L., & Schleiter, P. (2022). Backlash policy diffusion to populists in power. PLoS ONE, 17(9), e0273951.

- Adhikari, P., Mariam, S., & Thomson, R. (2022). The fulfilment of election pledges in India. Journal of Contemporary Asia, Forthcoming.

- Afonso, A. (2015). Choosing whom to betray: Populist right-wing parties, welfare state reforms, and the trade-off between office and votes. European Political Science Review, 7(2), 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773914000125

- Akkerman, T. (2012). Comparing radical right parties in government: Immigration and integration policies in nine countries (1996-2010). West European Politics, 35(3), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665738

- Akkerman, T. (2015). Immigration policy and electoral competition in Western Europe: A fine-grained analysis of party positions over the past Two decades. Party Politics, 21(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812462928

- Akkerman, T., de Lange, S., & Rooduijn, M. (2016). Radical right-wing populist parties in Western Europe: Into the mainstream? Routledge.

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populists are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

- Akkerman, A., Zaslove, A., & Spruyt, B. (2017). ‘We the people’ or ‘We the peoples’? A comparison of support for the populist radical right and populist radical left in The Netherlands. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 377–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12275

- Alvarez, R. M. (1998). Information and elections. University of Michigan Press.

- Anderson, B., Böhmelt, T., & Ward, H. (2017). Public opinion and environmental policy output: A cross-national analysis of energy policies in Europe. Environmental Research Letters, 12(11), 114011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8f80

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press.

- Bakaki, Z., Böhmelt, T., & Ward, H. (2020). The triangular relationship between public concern for environmental issues, policy output, and media attention. Environmental Politics, 29(7), 1157–1177. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1655188

- Bara, J. (2005). A question of trust: Implementing party manifestos. Parliamentary Affairs, 58(3), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsi053

- Bauer, M. W., & Becker, S. (2020). Democratic backsliding, populism, and public administration. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 3(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvz026

- Blais, A., Blake, D., & Dion, S. (1993). Do parties make a difference? Parties and the size of government in liberal democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 40–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111523

- Böhmelt, T. (2021a). Populism and environmental performance. Global Environmental Politics, 21(3), 97–123. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00606

- Böhmelt, T. (2021b). How public opinion steers national immigration policies. Migration Studies, 9(3), 1461–1479. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnz039

- Böhmelt, T., & Ezrow, L. (2022). How party platforms on immigration become policy. Journal of Public Policy, 42(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X20000331

- Böhmelt, T., Ezrow, L., Lehrer, R., Schleiter, P., & Ward, H. (2017). Why dominant governing parties are cross-nationally influential. International Studies Quarterly, 61(4), 749–759. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx067

- Böhmelt, T., Ezrow, L., Lehrer, R., & Ward, H. (2016). Party policy diffusion. American Political Science Review, 110(2), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000162

- Bos, L., Van der Brug, W., & De Vreese, C. (2010). Media coverage of right-wing populist leaders. Communications, 35(2), 141–163.

- Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpi014

- Bräuninger, T. (2005). A partisan model of government expenditure. Public Choice, 125(3-4), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-005-3055-x

- Breunig, C., Cao, X., & Luedtke, A. (2012). Global migration and political regime type: A democratic disadvantage. British Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 825–854. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000051

- Bromley-Trujillo, R., & Poe, J. (2020). The importance of salience: Public opinion and state policy action on climate change. Journal of Public Policy, 40(2), 280–304. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X18000375

- Busby, E. C., Gubler, J. R., & Hawkins, K. A. (2019). Framing and blame attribution in populist rhetoric. Journal of Politics, 81(2), 616–630. https://doi.org/10.1086/701832

- Canovan, M. (1981). Populism. Junction Books.

- Caramani, D. (2017). Will vs. Reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government. American Political Science Review, 111(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000538

- Carson, A., Gibbons, A., & Martin, A. (2019). Did the minority Gillard government keep Its promises? A study of promissory representation in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science, 54(2), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2019.1588956

- Castanho Silva, B., Andreadis, I., Anduiza, E., Blanusa, N., Corti, Y. M., Delfino, G., Rico, G., Ruth, S., Spruyt, B., Steenbergen, M. R., & Littvay, L. (2018). Public opinion surveys: A New scale. In K. A. Hawkins, R. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. R. Kaltwasser (Eds.), The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis (pp. 150–178). Routledge.

- Castanho Silva, B., Jungkunz, S., Helbling, M., & Littvay, L. (2020). An empirical investigation of seven populist attitude scales. Political Research Quarterly, 73(2), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912919833176

- Combei, C. R., & Giannetti, D. (2020). The immigration issue on twitter political communication: Italy 2018-2019. Communicazione Politica, 21(2), 231–263.

- Cornelius, W., & Rosenblum, M. R. (2005). Immigration and politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 8(1), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.8.082103.104854

- Dahl, R. A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition. Yale University Press.

- Dassonneville, R., Feitosa, F., Hooghe, M., & Oser, J. (2021). Policy responsiveness to all citizens or only to voters? A longitudinal analysis of policy responsiveness in OECD countries. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 583–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12417

- De la Torre, C. ed. (2014). The promise and perils of populism: Global perspectives. University Press of Kentucky.

- De Sousa, L., Fernandes, D., & Weiler, F. (2021). Is populism Bad for business? Assessing the reputational effect of populist incumbents. Swiss Political Science Review, 27(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12411

- Döring, H., & Manow, P. (2012). Parliament and government composition database (ParlGov): An infrastructure for empirical information on parties, elections, and governments in modern democracies. Available online at: http://parlgov.org/.

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Addison Wesley.

- Doyle, D. (2011). The legitimacy of political institutions: Explaining contemporary populism in Latin America. Comparative Political Studies, 44(11), 1447–1473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011407469

- Duval, D., & Pétry, F. (2019). Time and the fulfillment of election pledges. Political Studies, 67(1), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321718762882

- Elling, R. C. (1979). State party platforms and state legislative performance: A comparative analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 23(2), 383–405. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111008

- Erikson, R., MacKuen, M., & Stimson, J. (2002). The macro polity. Cambridge University Press.

- Ezrow, L., Fenzl, M., & Hellwig, T. (2023). Bicameralism and policy responsiveness to public opinion. American Journal of Political Science, Forthcoming.

- Ezrow, L., Hellwig, T., & Fenzl, M. (2020). Responsiveness, If You Can afford It: Policy responsiveness in good and Bad economic times. The Journal of Politics, 82(3), 1166–1170. https://doi.org/10.1086/707524

- Forchtner, B., & Kølvraa, C. (2015). The nature of nationalism: Populist radical right parties on countryside and climate. Nature and Culture, 10(2), 199–224. https://doi.org/10.3167/nc.2015.100204

- Freeman, G. (1995). Modes of immigration policies in liberal democratic states. International Migration Review, 29(4), 881–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839502900401

- Haas, H. d., Natter, K., & Vezzoli, S. (2014). Compiling and coding migration policies: Insights from the DEMIG POLICY database. Oxford Department of International Development.

- Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J., & Xu, Y. (2019). How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Political Analysis, 27(2), 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.46

- Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & de Vreese, C. (2017). The appeal of media populism: The media preferences of citizens with populist attitudes. Mass Communication and Society, 20(4), 481–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2017.1291817

- Hawkins, K. A. (2003). Populism in Venezuela: The rise of Chavismo. Third World Quarterly, 24(6), 1137–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590310001630107

- Hawkins, K. A., Carlin, R., Littvay, L., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2019). The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis. Routledge.

- Hawkins, K. A., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2018). Introduction – concept, theory, and method. In K. A. Hawkins, R. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. R. Kaltwasser (Eds.), The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis (pp. 1–24). Routledge.

- Hay, C., & Stoker, G. (2009). Revitalising politics: Have we lost the plot? Representation, 45(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344890903129681

- Heinisch, R. (2003). Success in opposition – failure in government: Explaining the performance of right-wing populist parties in public office. West European Politics, 26(3), 91–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380312331280608

- Helbling, M., & Kalkum, D. (2018). Migration policy trends in OECD countries. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(12), 1779–1797. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1361466

- Henisz, W. J. (2002). The institutional environment for infrastructure investment. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(2), 355–389. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/11.2.355

- Hicks, A. M., & Swank, D. H. (1992). Politics, institutions, and welfare spending In industrialized democracies, 1960-82. American Political Science Review, 86(3), 658–674. https://doi.org/10.2307/1964129

- Hobolt, S. (2016). The brexit vote: A divided nation, A divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

- Howard, M. (2010). The impact of the Far right on citizenship policy in Europe: Explaining continuity and change. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(5), 735–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691831003763922

- Huber, R. A. (2020). The role of populist attitudes in explaining climate change skepticism and support for environmental protection. Environmental Politics, 29(6), 959–982. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1708186

- Huber, E., Rueschemeyer, D., & Stephens, J. (1993). The impact of economic development on democracy. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(3), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.7.3.71

- Huber, R. A., & Ruth, S. P. (2017). Mind the Gap! populism, participation, and representation in Europe. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 462–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12280

- Huber, R., & Schimpf, C. H. (2016). Friend or Foe? Testing the influence of populism on democratic quality in Latin America. Political Studies, 64(4), 872–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12219

- Huber, R. A., & Schimpf, C. H. (2017). On the distinct effects of left-wing and right-wing populism on democratic quality. Politics and Governance, 5(4), 146–165. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v5i4.919

- Jennings, W., & Wlezien, C. (2018). Election polling errors across time and space. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0315-6

- Kang, S.-G., & Powell, B. (2010). Representation and policy responsiveness: The median voter, election rules, and redistributive welfare spending. The Journal of Politics, 72(4), 1014–1028. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000502

- Karreth, J., Polk, J. T., & Allen, C. S. (2013). Catchall or catch and release? The electoral consequences of social democratic parties’ march to the middle in Western Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 46(7), 791–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012463885

- Keman, H. ed. (2002). Comparative democratic politics: A guide to contemporary theory and research. Sage.

- Kennedy, J., Alcantara, C., & Armstrong, D. (2021). Do governments keep their promises? An analysis of speeches from the throne. Governance, 34(1), 917–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12548

- King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.2307/2669316

- Kishishita, D., & Yamagishi, A. (2021). Contagion of populist extremism. Journal of Public Economics, 193, 104324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104324

- Knill, C., Debus, M., & Heichel, S. (2010). Do parties matter in internationalised policy areas? The impact of political parties on environmental policy outputs in 18 OECD countries, 1970-2000. European Journal of Political Research, 49(3), 301–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01903.x

- Krause, W., & Wagner, A. (2019). Becoming part of the gang? Established and non-established populist parties and the role of external efficacy. Party Politics, 27(1), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819839210

- Kriesi, H. (2014). The populist challenge. West European Politics, 37(2), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887879

- Lehmann, P., & Zobel, M. (2018). Positions and saliency of immigration in party manifestos: A novel dataset using crowd coding. European Journal of Political Research, 57(4), 1056–1083. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12266

- Lockwood, M. (2018). Right-Wing populism and the climate change agenda: Exploring the linkages. Environmental Politics, 27(4), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411

- Lührmann, A., Düpont, N., Higashijima, M., Kavasoglu, Y. B., Marquardt, K. L., Bernhard, M., Döring, H., Hicken, A., Laebens, M., Lindberg, S. I., & Medzihorsky, J. (2020). Codebook varieties of party identity and organisation (V-party) V1. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

- Lundquist, S. (2022). Do parties matter for environmental policy stringency? Exploring the program-to-policy link for environmental issues in 28 countries 1990-2015. Political Studies, Forthcoming.

- Lutz, P. (2019). Variation in policy success: Radical right populism and migration policy. West European Politics, 42(3), 517–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1504509

- Lutz, P. (2021). Reassessing the gap-hypothesis: Tough talk and weak action in migration policy? Party Politics, 27(1), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819840776

- Matthieß, T. (2020). Retrospective pledge voting: A comparative study of the electoral consequences of government parties’ pledge fulfilment. European Journal of Political Research, 59(4), 774–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12377

- McCarty, N., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2006). Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. MIT Press.

- McDonald, M., & Budge, I. (2005). Elections, parties, democracy: Conferring the median mandate. Oxford University Press.

- Meguid, B. M. (2005). Competition between unequals: The role of mainstream party strategy in niche party success. American Political Science Review, 99(3), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051701

- Meguid, B. (2008). Party competition between unequals. Strategies and electoral fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Mény, Y., & Surel, Y. (2002). Democracies and the populist challenge. Palgrave.

- Moffitt, B. (2018). The populism/anti-populism divide in Western Europe. Democratic Theory, 5(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3167/dt.2018.050202

- Money, J. (2010). Comparative immigration policy. In R. Denemark (Ed.), The International studies encyclopedia. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government & Opposition, 39(3), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2012). Populism and (liberal) democracy: A framework for analysis. In C. Mudde, & C. R. Kaltwasser (Eds.), Populism in Europe and the Americas (pp. 1–26). Cambridge University Press.

- Müller, W. C., & Strøm, K. (1999). Policy, office, or votes? How political parties in Western Europe make hard decisions. Cambridge University Press.

- Naurin, E. (2009). Promising democracy. Parties, citizens, and election promises. Department of Political Science: Statsvetenskapliga institutionen.

- Naurin, E. (2011). Election promises, party behavior, and voter perceptions. Springer.

- Naurin, E., Royed, T. J., & Thomson, R. (2019). Party mandates and democracy: Making, breaking, and keeping election pledges in twelve countries. University of Michigan Press.

- Naurin, E., & Thomson, R. (2020). The fulfillment of election pledges. In M. Cotta, & F. Russo (Eds.), Research handbook on political representation (pp. 289–300). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash. Cambridge University Press.

- Oliver, J. E., & Rahn, W. M. (2016). Rise of the trumpenvolk: Populism and the 2016 election. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216662639

- Otjes, S., & Louwerse, T. (2015). Populists in parliament: Comparing left-wing and right-wing populism in The Netherlands. Political Studies, 63(1), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12089

- Panizza, F. (2000). New wine in Old bottles? Old and New populism in Latin America. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 19(2), 145–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9856.2000.tb00095.x

- Peters, Y. (2016, September 20–21). The politics of representation. Paper prepared for presentation at the “Stein Rokkan’s Heritage” Workshop, Bergen, Norway.

- Riera, P., & Pastor, M. (2022). Cordons sanitaires or tainted coalitions? The electoral consequences of populist participation in government. Party Politics, 28(5), 889–902.

- Roberts, K. (2007). Latin America’s populist revival. The SAIS Review of International Affairs, 27(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2007.0018

- Rooduijn, M. (2019). State of the field: How to study populism and adjacent topics? A pleas for both more and less focus. European Journal of Political Research, 58(1), 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12314

- Rooduijn, M., & Akkerman, T. (2017). Flank attacks: Populism and left-right radicalism in Western Europe. Party Politics, 23(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815596514

- Rooduijn, M., De Lange, S. L., & Van der Brug, W. (2014). A populist zeitgeist? Programmatic contagion by populist parties in Western Europe. Party Politics, 20(4), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068811436065

- Rooduijn, M., Van der Brug, W., & De Lange, S. L. (2016). Expressing or fuelling discontent? The relationship between populist voting and political discontent. Electoral Studies, 43, 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.006

- Schaffer, L. M., Oehl, B., & Bernauer, T. (2022). Are policymakers responsive to public demand in climate politics? Journal of Public Policy, 42(1), 136–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X21000088

- Soroka, S., & Wlezien, C. (2010). Degrees of democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Taggart, P. (2002). Populism and the pathology of representative politics. In Y. Mény, & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 62–80). Palgrave.

- Thomson, R. (1999). The party mandate: Election pledges and government actions in the Netherlands, 1985-1998 [PhD Dissertation]. University of Groningen.

- Thomson, R., Royed, T., Naurin, E., Artés, J., Costello, R., Ennser-Jedenastik, L., Ferguson, M., Kostadinova, P., Moury, C., Pétry, F., & Praprotnik, K. (2017). The fulfillment of parties’ election pledges: A comparative study on the impact of power sharing. American Journal of Political Science, 61(3), 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12313

- Vachudova, M. (2021). Populism, democracy, and party system change in Europe. Annual Review of Political Science, 24(1), 471–498. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102711

- Van Hauwaert, S., Schimpf, C., & Azevedo, F. (2020). The measurement of populist attitudes: Testing cross-national scales using item response theory. Politics, 40(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395719859306

- Vercesi, M. (2019). Do populists govern differently? The management of the Italian M5S-league coalition in comparative perspective. Perspectivas – Journal of Political Science, 21, 9–24. https://doi.org/10.21814/perspectivas.2557

- Vodová, P. (2021). What makes a good minister of a political party? Impact of party- and field-related experience on party pledge fulfilment. Party Politics, Forthcoming.

- Walter, S. (2021). The backlash against globalization. Annual Review of Political Science, 24(1), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102405

- Werner, A. (2019). Voters’ preferences for party representation: Promise-keeping, responsiveness to public opinion, or enacting the common good. International Political Science Review, 40(4), 486–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512118787430

- Werner, A., & Geibler, H. (2019). Do populists represent? Theoretical considerations on How populist parties (might) enact their representative function. Representation, 55(4), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2019.1643776

- Weyland, K. (2003). Economic voting reconsidered: Crisis and charisma in the election of hugo chavez. Comparative Political Studies, 36(7), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414003255106

- Wuttke, A., Schimpf, C., & Schoen, H. (2020). When the whole is greater than the Sum of its parts: On the conceptualization and measurement of populist attitudes and other multidimensional constructs. American Political Science Review, 114(2), 356–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000807