ABSTRACT

Research about transitions in early childhood education has had an upsurge especially in the last 15 years. Much attention has been directed to what constitutes and builds up positive transitions. Although, as learning is one of the main tasks in educational settings, there is a need for more explicit research discussions in the transition research field about children’s learning in transition. The aims of this article are to discuss and unravel the theoretical concept ‘learning journey’ and to propose a conceptual framework for analyzing children’s learning in early educational transitions. The article gives a review of the concept learning journey and related terms: learning, continuity/discontinuity, change, collaboration and time. A conceptual framework of learning journey is proposed and a model presented. The model is discussed in relation to the PPCT-model of Urie Bronfenbrenner and a final discussion set the proposed conceptual framework of learning journey in the context of application to early childhood education.

Introduction

In the European Early Childhood Education Research Association (EECERA), the Transitions SIG was formed in London at the conference in 2000. Research about transitions in early childhood education has had an upsurge especially in the last 15 years. Educational transition research has been approached from many perspectives, e.g. diversity (Hohepa and McIntosh Citation2017), inclusion (McIntyre et al. Citation2007), collaboration (Lillvist and Wilder Citation2017), children’s perspectives (Einarsdottir Citation2011) and policy (Perry, Dockett, and Petriwskyj Citation2014). It can be said that there is a concordance among researchers in the field about the importance of smooth transitions (Dockett and Perry Citation2007), the importance of collaboration across settings (Perry, Dockett, and Petriwskyj Citation2014) and that children should be seen as active agents in forming their learning and development (Seung Lam and Pollard Citation2006).

In order to capture and understand the multifaceted processes and influences that take place in educational transitions, transition research has particularly applied the bio-ecological systems theory by Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979, Citation1999, Citation2006). The bio-ecological systems theory provides a theoretical model about direct and indirect influences on children’s learning and development by five concurrent surrounding systems: macro-, exo-, meso-, micro-, and chrono- system. This theory can be considered to give a somewhat distal frame (Vogler, Crivello, and Woodhead Citation2008), and some researchers have developed it to better fit the research area of early educational transitions, see e.g. Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta (Citation2000) and Dunlop (Citation2003). In order to investigate relationships between teachers and children and learning the socio-cultural theory of the proximal zone of development, as first proposed by Vygotsky ([Citation1934] Citation1986), has been used to explain and understand the dynamics in the learning process in transitions. A theory that has been used to consider phases in transitions is van Gennep’s theory of rites of passages where the transition is divided into three phases: preliminal/separation, liminal/transition and postliminal/incorporation (van Gennep [Citation1908] Citation1997).

In the effort to reflect upon and understand the links between theory and practice metaphors are commonly used to describe the abstract more concrete (Nilholm Citation2016). A metaphor that has been used in transition research is ‘the bridge’. The bridge metaphor has been used to describe the ambition to overcome the gap between prior-to-school and school settings (Huser, Dockett, and Perry Citation2015); as Huser, Dockett and Perry states: ‘a bridge between preschool and school can promote connections, particularly between the familiar and the unfamiliar; provide support as a passage is navigated and serve as a platform for guiding that passage’ (2). As such, the bridge metaphor has come to set light on collaboration and mutual respect for different professionals’ knowledge. Another metaphor that is often used in transition research, but that has not been as much elaborated on as the bridge metaphor, is ‘learning journey’ (e.g. Peters Citation2010). In learning being one of the main tasks in educational settings, we find it surprising that the metaphor learning journey has been used in the research literature although not defined, elaborated or unraveled much. We see learning journey as a theoretical concept and the aims of this paper is to discuss and unravel the theoretical concept, and to propose a conceptual framework for analyzing children’s learning in early educational transitions by using ‘learning journey’.

Our research about the educational transition from preschool to school for young children with intellectual disability has inspired us to analyze learning processes and development in the field of early educational transitions (see earlier published papers; Lillvist and Wilder Citation2016; Wilder and Lillvist Citation2016; Lillvist and Wilder Citation2017; Wilder and Lillvist Citation2017). In our work, we have found that there is a need for more explicit discussions in the transition research field about children’s learning in transition. Thus, this paper begins with a review of the concept learning journey and related terms: learning, continuity/discontinuity, change, collaboration and time. A conceptual framework of learning journey will be proposed and a model will be presented and discussed. The final discussion will put the proposed conceptual framework of learning journey in the context of application to early childhood education.

Review of ‘learning journey’ and related terms

In her research about educational transitions in early childhood Peters (Citation2010) formulated that children’s learning processes in transitions from preschool to school can be understood in terms of learning journey. Peters (Citation2010, Citation2014) means that children’s learning journey is a key thread within their transition journey, and emphasizes the meaning of bridging between different stages of education to support children’s learning. Peters does not elaborate more on the processes on learning, rather, she discusses how the bridging of different cultures that exist in prior-to-school settings and formal school settings can be made in a ‘borderland’ (Citation2010). In sharing understandings in the borderland Peters means that each educational setting take stands to reach the other by crossing borders (Citation2014, 111). She states that by metaphorically crossing the borders and meeting in a commonly shared borderland, opportunity to reframe the view of learners and learning is made possible.

The terms that we have chosen to include in the conceptual framework of learning journey come from the analyses of trends and findings in educational transition research but also from research about early child development (e. g. Wachs Citation2000). Learning, continuity/discontinuity, change, collaboration and time have all been highlighted in educational transition research, but often separately (see e.g. Griebel and Niesel Citation2009; Ackesjö Citation2014; Lillvist and Wilder Citation2016). The five terms are concepts that indicate process and research in the educational transitions area has not yet grasped the dynamics of key processes for and in early childhood education concretely enough. We propose that a collective view on these five terms can facilitate giving focus on child learning in transition in early childhood education both in research and in practice.

Learning

How can learning be understood in the metaphor learning journey? Vygotskian theory focus on learning as a social process, and that learning as a process results in development (Vygotsky [Citation1934] Citation1986; Vogler, Crivello, and Woodhead Citation2008). Children observe and act, they learn by experiencing the consequences of their own actions and by observing the consequences of others actions (see e. g. Bandura Citation1962). Even further, Rogoff suggests that children learn even when they are seemingly passive as they constantly are engaged in understanding their context (Rogoff Citation2003). This view of learning is close to Dewey’s social-cultural perspective which means that children try to make meaning of and in their actions and experiences. Öhman (Citation2008) states that ‘prior experiences are re-actualized in an event and thus plays a part in the process of meaning-making, as well as contributing to the substance of the meanings made’ (25). Also in line with Dewey’s theory, Elkjaer (Citation2000) suggests, we see learning as an individual as well as a collective phenomenon and that learning involves both action and thinking (86). She also proposes that non-discursive- and language experiences build up a person’s learning over time (Elkjaer Citation2000). Concluding, one can say that children’s learning is determined by their meaning-making of previous experiences and that this also colors the meaning-making of experiences made in new contexts. As such, learning is a socially contextualized process, and, at the same time, learning is bound to the situations of the individual child. Thus, in educational transition, which in itself is a process over an extended time, learning is an always ongoing individual and collaborative process in which children learn actively and passively through their context.

How is learning perceived by children and by their key adult interaction partners in transitions from preschool to school? In her research on early educational transitions Dunlop qualitatively longitudinally studied children’s learning (Citation2003). She found that teachers and children had different perspectives and appraisals about learning. The children she followed in her research had views about their own learning that were situated to their immediate context and achievements, for example, how well they could write letters or how far they could count. Primary school teachers, on the other hand, had a more long-term thinking about learning and, for example, related the children’s learning to the future of what could be achieved. Furthermore, Dunlop found that preschool teachers and primary school teachers had somewhat different views of children as learners (Citation2002). While preschool teachers focused their view of children as learners on children’s curiosity, social abilities and play, primary school teachers’ views of the children as learners were more scholastic (Dunlop Citation2002). Similar findings have been described by Einarsdottir (Citation2011). Einarsdottir studied what Icelandic children felt that they learnt when they started primary school and also in what way what they had learnt in preschool was of use when they started primary school. In taking the children’s perspectives of 40 children through drawings and group interviews she found that the children perceived academic-oriented school subjects as highly valued learning from playschool. The children also found that learning the rules applied in school before beginning primary school as useful. Einarsdottir concludes that these findings are important messages of what children perceive as most valued in primary school. In the same research, Einarsdottir also interviewed primary school teachers about the children’s views and the teachers were somewhat surprised about the children’s focus on school culture and academic learning (Citation2011).

Research results in line with the findings in the research examples above about the differences in views about learning in preschool and primary school have been found by several other early transition researchers (see e.g. Dockett and Perry Citation2007; and Broström Citation2006). This is something that has been continuously discussed in the field of early educational transition research, the differing view about learning that preschool teachers and primary school teachers may have. Accountable for these differences have been said to be, for example, the different curricula for preschool and school, teacher education and culture of settings. The differences color children’s learning journey and actions have been taken even on macro-level to facilitate children’s smooth transitions. For example, in Sweden, a reform in 1998 introduced preschool class as an interannual year between preschool and primary school. The intentions of the preschool class reform were to promote a fusion of prior-to-school and school education, and to lay the foundation for continued education for children by encouraging learning and development (National Agency for Education Citation2012). Continuity between settings and stakeholders are important, and continuity is a key term in children’s learning journey.

Continuity/discontinuity

John Dewey wrote: ‘what the student has learned in the way of knowledge and skill in one situation becomes an instrument of understanding and dealing effectively with the situations which follow’ ([Citation1938] Citation1963, 44). With this, he points to a crucial aspect of the concept of learning journey, namely: continuity. The concept of continuity is frequently used in research about educational transitions. At first sight, it might seem quite straightforward: continuity- something that is continuing. However, what is continuing in the transition from one educational setting to another can vary and be of varying importance to children. Dewey described continuity as continuity in experiences, as every new experience is linked to past experiences and also modifies future experiences. Thus, from a learning perspective, it is important for teachers to gain knowledge about children’s prior experiences in order to unfold a reconstruction of learning through experiencing.

In more recent research the concept of continuity has been described from different perspectives. Social, or relational continuity refers to maintaining peer-relations intact during transitions and has been studied by Fabian (Citation2007) who also argue for physical continuity by, for example, using the same type of material or furniture in the settings for the transition, and philosophical continuity referring to continuity in values, concepts and methods used in the different settings. For instance, in a preschool setting play is valued highly for its own value but also as means of learning. In compulsory school, a traditional learning paradigm exists with less focus on play. If the gap between the philosophical continuity is too wide between educational settings the learning journeys of children can be filled with discontinuities. On an institutional level continuity has been described by Mayfield (Citation2003) and Broström (Citation2009) as how the settings are organized as well as how the communication between the settings flows.

Continuity can be applied to different dimensions of educational transitions; also discontinuities are embedded in educational transitions. Ackesjö (Citation2014) describes that discontinuities can provide challenges, possibilities and symbolic boundaries that lead to new territories of learning. Children can, for example, look forward to their first homework from school, as this is a proof of the passage to a school context and, along with that a proof of no longer being a preschool child. Thus, educational discontinuities can be understood as identity markers, related to a change in role or position that the transition brings along and that children face with positive anticipation (Ackesjö Citation2014; Lago Citation2016).

From an adult perspective, we understand that in educational transitions some discontinuities are unavoidable and growth and development are symbolized to children by adult organized rites of passages. But, rites of passages and discontinuities can be deceiving. As time and change are natural elements of transitions and development it is easier to go with that natural flow instead of taking charge of the contents of what early educational transitions is. We shall write more about change and time below. Rites of passages can be considered as ways to prepare children for unavoidable discontinuities in transitions. In that way efforts to ensure continuity in transitions, in order to obtain smooth transitions, is not thwarted.

Change

An always present feature of a learning journey is change and transitions as sites for change has been advocated by many researchers (see e.g. Vogler, Crivello, and Woodhead Citation2008; Dunlop Citation2017). Volger et al. capture this very eloquently: ‘Transitions can be understood as key moments within the process of socio-cultural learning whereby children change their behavior according to new insights gained through social interaction with their environment’ (Citation2008, 8). In taking the socio-cultural learning perspective, as previously described, when considering Griebel and Niesel’s proposition of change occurring at three levels in the transition from preschool to school, aspects of children’s learning can be understood in more depth.

Griebel and Niesel (Citation2009) propose that the transition from preschool to school comes with changes on, individual level, relational level and organizational level. At an individual level, the transitions may bring about change in identity, roles and relations in the child’s and parents’ lives. Apart from more scholastic demands, starting school demands that the child be more autonomous, have more self-control and emotional regulation. At a relational level of change, the schoolchild may first lose some relationships i.e. with the preschool teacher and preschool friends. Although with time, the child will make new relationships and also form new affiliations. For parents, the situation is similar in that some relationships will be lost and new ones will be made. The difficult part for both children and parents is in losing relationships of trust, warmth and security. Preschool staff are often seen as a very important and helpful source of support for parents (Pianta et al. Citation2001). The third level of change in educational transitions identified by Griebel and Niesel (Citation2009) is the contextual level. The contextual level signifies changes in the learning environment of children and the actual place and setting of the new school. The learning environment contains both the physical location and artifacts of the new school, and also the school curriculum which frames and guides the activities in the new learning environment. Challenges for young children at this level multiply as almost everything is new to them. Children may be expected to cope with a lot of these changes as developmental tasks together with their peers.

Following Bateson’s view of change as brought about by information, Warner, Hull, and Laughlin (Citation2015) suggest that change is relational. They see the world as relationally organized and state that collaboration between parents, teachers and children is the basis for change. We propose that the amount and quality of relationships and exchanges of information determine change in learning during a child’s learning journey made in educational transitions.

Collaboration

In early educational transitions collaboration is a rather concrete need and quest from and of many stakeholders, for example, parents, preschool teachers, primary school teachers and principals. In order for a child to gain a smooth transition professionals and parents collaborate, collaboration can be motivated by several things, of course by the best intentions for a child’s wellbeing, but, also the worry for a child can be a motivation for collaboration. Another motivation can be a teacher’s hope of time savings in their teacher profession. Educational transitions involve bridging knowledge through collaboration.

Parents often depend on teachers and principals to provide information and initiate transition activities (Bailey Citation2011), and approaches of stakeholders in collaborating educational settings color what actual collaborative activities are performed and how they are performed (Danermark and Germundsson Citation2011). In collaborative educational transition processes, there is a risk of power imbalance (Petriwskyj Citation2014). Keen (Citation2007) described the ‘relationship power’ that can prevail in these partnerships. Relationship power concerns the ability to influence others, and the official nature of professional work can, for example, sometimes discourage parent participation in decision-making. Promoting teachers’ self-conscious awareness of power in transition processes, combined with efforts to balance power, can be strategies to facilitate the range of different stakeholders’ perspectives being considered in collaboration (Petriwskyj Citation2014). Hanson (Citation2005) highlights that communication and effective collaboration is more likely to be achieved through parental and professional partnerships. Optimal partnerships are those which build on family strengths and foster empowerment or enablement of family members to accomplish their goals and demonstrate competence (Hanson Citation2005).

Time

Conclusively, the theoretical concept learning journey also entails a temporal dimension. A journey can in one sense involve a process of leaving one place in order to arrive at another, in another sense a journey can be seen as never-ending. As the learning journey take place throughout the educational life of an individual it can be understood as a lifelong journey. Transitions between educational settings are where the learning journey is situated as in between, and among, two settings, and thus can be viewed as critical incidents, depending on the outcome of the continuities and discontinuities of the transition. The learning journey exceeds specific educational transitions, and is made up of several educational transitions and the time and experiences between transitions.

When do educational transitions start? It can be argued that the time encompassing educational transitions from a formal or physical point of view, has a clear point of start and ending. One day formally enrolled in preschool and at a given time the enrollment ends in favor for school. Likewise, the physical transition of arriving to a building can easily be marked as ‘checked’. However, within that specific building or institution social codes, traditions, and roles give identity to the persons sharing that institution, for example of how to be a pupil. These social codes and traditions are often unspoken and time of adjustment to these new roles will vary among individuals and their families. Perry, Dockett, and Petriwskyj (Citation2014) describe the general outcome of positive transitions as a sense of belonging. Prior to the sense of belonging the process of educational transitions as a journey of crossing borders (Peters Citation2014) can be understood in terms of liminality as described by van Gennep (Citation1960) and later by Turner (Citation1969). Liminality is the state of being in, what Turner refers to, betwixt and between. It is the ambiguous transitional state where the sense of belonging is yet to come. van Gennep divided liminality into three different stages; preliminal; which is set during the separation process, the liminal; referring to the transition and the postliminal; which encompasses the time of adjustment after the transition. We argue that collaboration and continuity/discontinuity as discussed earlier in this paper can have a positive effect on the state of liminality by facilitating a base for sense of belonging.

The learning journey connects the past and the future, but the focus is mainly on the present. Looking into a child’s situation at a specific time, be it before-, direct in- or after a transition point, gives a cross-sectional perspective on a child’s learning journey.

In summary, learning, continuity/discontinuity, change and collaboration are the important aspects around which a child’s learning journey evolve. All these four aspects influence and color learning journeys and make them individual. Depending on aspects of learning, continuity/discontinuity, change and collaboration, the learning journey can take different turns, breaks or cumulative development facilitating children’s learning over time. This is something that we illustrate in the framework that we will present next. The framework is described in a model in which we further explain how these four aspects interact and interplay, also in the perspective of time.

Framework of the theoretical concept learning journey

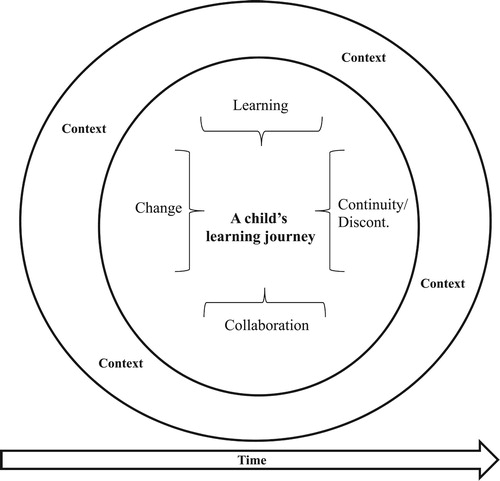

depicts a model of the conceptual framework for the theoretical concept learning journey. The model is presented as a cylinder seen from above with two concentric circles. The outer circle is the contexts in which the child has direct experiences, for example, the home environment and the preschool environment. But it can also be other contexts in which the child regularly participates, for example, the playground area that is visited every day after preschool, or every Thursday evening when grandmother babysits. Contexts on this level have the same direct influence on children as Bronfenbrenner describes on the micro level in the bio-ecological model. Inside the heart of the cylinder is the four conceptual aspects that build up a child’s learning journey which we have described previously in the paper: learning, continuity/discontinuity, change and collaboration. Dynamics of the four aspects influence the child’s learning journey. Metaphorically the cylinder is colored in different ways depending on the interplay and interactions between the four aspects and within a child’s learning journey.

Figure 1. Model of a conceptual framework for the theoretical concept learning journey in educational transitions.

In the model, there is an arrow below the concentric circles/the cylinder, this arrow indicates the time. The arrow points forward as an indication for time and development. The cylinder roles in the direction of time; much like the chrono-system is always present in the socio-bio-ecological developmental model by Bronfenbrenner and Morris (Citation2006). Although time is linear the circular turn of the cylinder represent how learning and development within the learning journey is cumulative.

Our model of a conceptual framework for the theoretical concept learning journey is undoubtedly inspired by Bronfenbrenner’s process-person-context-time model (Bronfenbrenner Citation2005). The outer concentric circle in our model depicts the same contexts that are found at the micro level of the PPCT-model. The differences are that our model draws the attention directly to the proximal level and focuses on the dynamics of the interchanges between key factors important for children’s learning. We also consider the proposed model appropriate to early childhood education research and practice as it challenges aspects of stake holder responsibilities in educational transitions of children.

Final discussion

First and foremost, children’s learning journeys are colored by key persons in their lives. Together with key persons children interact and participate, and learn, within their contexts (Wachs Citation2000; Seung Lam and Pollard Citation2006). Key persons for children are the person’s children spend a lot of time with and have long relationships with, and these persons have a great impact on children’s orientation and transitions (Vogler, Crivello, and Woodhead Citation2008). As has been described in this paper learning comes from passive and active dynamic processes that children have within and among their contexts. Professionals need to consider the combination of learning, key persons and contexts, and what processes that takes place over time.

The proposed conceptual framework of the theoretical concept learning journey can be used to make visible common processes for learning that take place across educational settings. By focusing on aspects of a child’s learning journey certain influential practices can be illuminated. Change, collaboration, learning and continuity/discontinuity can be zoomed in at any time in educational transitions, these aspects can be investigated. The framework and theoretical concept have a direct application to early childhood education in the following way.

Learning

Knowledge about children’s learning needs to be transmitted both from the delivering setting and the receiving setting when an educational transition takes place. Key persons in children’s contexts need to be aware of what the child’s learning consists of, and of the child’s future potentials in their learning. A child’s learning consists of what it has learned, but in particular, the child’s learning consists of what the child will be able to learn together with others. In this socio-cultural perspective, it becomes important to utilize knowledge and reflections that a delivering educational setting, such as preschool, has about the child; knowledge of the child now but also about the child’s learning potentials. How does the child learn? What experiences does the delivering contexts have on how to learn with the child? It is also important that the receiving side in a transition consciously understands its own view of children’s learning and of a specific child’s learning. In addition to this professionals understanding of children’s learning can further be deepened if they also are responsive to what parents tell about their child’s learning at home. Getting a shared understanding of a specific child’s learning, ie consolidating the knowledge and experience of delivering settings and the receiving setting’s readiness for the child’s learning, promotes positive transitions.

Continuity/discontinuity

In addition to children’s learning, continuity ans discontinuity in learning journeys can be investigated by asking questions about relational, physical, philosophical and institutional continuity. Relational and physical continuity are rather easy to see and easy to have opinions about. As a first step, the delivering and receiving parts can come to a consensus about how to ease relational and physical continuity. A probably more complicated consensus to reach is how to communally approach philosophical and institutional continuity. Philosophical continuity refers to values, concepts and methods used in the different settings. These have to do with traditional and cultural ways of ‘doing’ school and preschool. Institutional continuity refers to organization which is often governed on municipal and/or national level. Often prerequisites for this continuity are argued not be in the hands of teachers or parents. Questions to illuminate continuity are for example: What are the specific child’s opinions about relational continuity? How is continuity in received support assured? In what way can principals facilitate institutional continuity? By asking questions about continuity discontinuities are exposed.

Change

Change always comes together with continuity and discontinuity. It is sometimes hard to separate continuity and change. Change may have a negative connotation in early childhood education, but it is through change that children develop and learn. Change is thus embedded in learning. And learning as such is a result of changes in cognitive structures. In order to catch the good features of change key persons in children’s lives should have control of what changes and to what avail. To gain knowledge about aspects of change questions as the following can be put: What changes on the individual, relational and contextual level does the transition entail? What amount and quality of relationships and exchanges of information are there in the transition? Taking a child perspective, what can be continued?

Collaboration

The final aspect of children’s learning journeys is collaboration. Collaborative processes are colored by an organization’s policies and rules but are carried out by representatives of the organization, such as teachers. In this way, it is through teachers’ approaches that collaboration is conducted. In collaboration, all parties need to be respected, and one needs to work towards jointly formulated goals. In a child’s transition between school forms, it is essential that parents, apart from teachers, are involved in the collaboration in children’s learning journeys. How is the involvement of key persons from a child’s all-important contexts made possible in collaboration? How does the receiving part in educational transitions take responsibility for collaboration?

At any time and context in a child’s life, the general questions above can be asked, and answers can be discussed between practitioners and parents, and, in research.

Conclusively, the aims of this paper have been to elaborate the theoretical concept learning journey and to propose a framework for analyzing children’s learning in early educational transitions. Learning journey is a theoretical concept about children’s learning over time across transitions between educational settings. With our proposed framework researchers in the field can focus more directly on investigating children’s learning in educational transitions. Furthermore, by using the model practitioners in the field can evaluate and improve their own work concerning children’s learning in transitions.

We think that defining children’s contexts and actual activities in children’s learning journeys when it comes to change, collaboration, learning and continuity/discontinuity can facilitate a clear application to early childhood education and care policy and practice. In order to proceed building optimal learning conditions for children in smooth transitions individual learning journeys must be acknowledged and seen. The conceptual framework and suggested way to use it in practice can be a means to achieve visualization of each child’s learning journey in educational transitions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackesjö, H. 2014. “Barns Övergångar till och från Förskoleklass: Gränser, Identiteter och (Dis-) kontinuiteter.” [Children’s Transitions to and from Preschool Class: Borders, Identities and (Dis-) continuities.] Doctoral thesis, Linnaeus University, Kalmar, Sweden.

- Bailey, H. N. 2011. “Transitions in Early Childhood: A Look at Parents’ Perspectives.” Doctoral thesis, Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, North Carolina, USA.

- Bandura, A. 1962. “Social Learning Through Imitation.” In Nebraska Symposium of Motivation, edited by M. R. Jones, 211–269. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Design and Nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1999. “Environments in Developmental Perspective: Theoretical and Operational Models.” In Measuring Environment Across The Life Span: Emerging Methods and Concepts, edited by S. L. Friedman, and T. D. Wachs, 3–28. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 2005. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and P. A. Morris. 2006. “The Bioecological Model of Human Development.” In Theoretical Models of Human Development. Volume 1 of Handbook of Child Psychology (6th Version), edited by R. M. Learner, 793–828. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Broström, S. 2006. “Children’s Perspectives on Their Childhood Experiences.” In Nordic Childhood and Early Education: Philosophy, Research, Policy and Practice in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, edited by J. Einarsdottir, and J. T. Wagner, 223–256. Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

- Broström, S. 2009. “Tilpasning, frigoring og demokrati.” [Adaptation, Liberation and Democracy.] Forste Steg 2: 24–28.

- Danermark, B., and P. Germundsson. 2011. “Social Representations and Power”.” In Education, Professionalization and Social Representations: On the Transformation of Social Knowledge, edited by M. Chaib, B. Danermark, and S. Selander, 33–44. New York: Routledge.

- Dewey, J. (1938) 1963. Experience and Education. New York: Collier Books.

- Dockett, S., and B. Perry. 2007. Transitions to School. Perceptions, Expectations, Experiences. Sydney: UNSW Press.

- Dunlop, A.-W. 2002. “Perspectives on Children as Learners in the Transition to School.” In Transitions in the Early Years. Debating Continuity and Progression for Children in Early Education, edited by H. Fabian, and A.-W. Dunlop, 98–110. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Dunlop, A.-W. 2003. “Bridging Early Educational Transitions in Learning Through Children’s Agency.” European Early Childhood Educational Research Journal 11:sup1: 67–86. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2003.12016706.

- Dunlop, A.-W. 2017. “Transition as a Tool for Change.” In Pedagogies of Educational Transitions. European and Antipodean Research, edited by N. Ballam, B. Perry, and A. Garpelin, 257–274. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Einarsdottir, J. 2011. “Icelandic Children’s Early Education Transition Experiences.” Early Education and Development 22: 737–756. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2011.597027

- Elkjaer, B. 2000. “The Continuity of Action and Thinking in Learning: Re-Visiting John Dewey.” Outlines: Critical Practice Studies 2 (1): 85–101.

- Fabian, H. 2007. “Informing Transitions.” In Informing Transitions in The Early Years, edited by A.-W. Dunlop, and H. Fabian, 3–19. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Griebel, W., and R. Niesel. 2009. “A Developmental Psychology Perspective in Germany: Co-Construction of Transitions Between Family and Education System by the Child, Parents and Pedagogues.” Early Years 29 (1): 59–68. doi: 10.1080/09575140802652230

- Hanson, M. J. 2005. “Ensuring Effective Transitions in Early Intervention.” In The Developmental Systems Approach to Early Intervention, edited by M. J. Guralnick, 373–398. Baltimore: Paul H Brooks Publishing.

- Hohepa, M., and L. McIntosh. 2017. “Transition to School for Indigenous Children.” In Pedagogies of Educational Transitions. European and Antipodean Research, edited by N. Ballam, B. Perry, and A. Garpelin, 77–93. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Huser, C., S. Dockett, and B. Perry. 2015. “Transition to School: Revisiting the Bridge Metaphor.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 24 (3): 439–449. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2015.1102414

- Keen, D. 2007. “Parents, Families, and Partnerships: Issues and Considerations.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 54 (3): 339–349. doi: 10.1080/10349120701488855

- Lago, L. 2016. “Different Transitions: Timetable Failures in the Transition to School.” Children & Society 31: 243–252. doi: 10.1111/chso.12176

- Lillvist, A., and J. Wilder. 2016. “Same Same But Different? Educational Transitions of Young Children with Intellectual Disabilities.” In Children and Young People in School and in Society, edited by A. Sandberg, and A. Garpelin, 135–154. New York: Nova Publishers.

- Lillvist, A., and J. Wilder. 2017. “Valued and Performed or Not? Teachers’ Ratings of Transition Activities for Young Children with Learning Disability.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 32 (3): 422–436. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2017.1295637

- Mayfield, M. I. 2003. “Teaching Strategies: Continuity among Early Childhood Programs.” Childhood Education 79: 239–241. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2003.10521201

- McIntyre, L. L., T. L. Eckert, B. H. Fiese, F. D. DiGennaro, and L. K. Wildenger. 2007. “Transition to Kindergarten: Family Experiences and Involvement.” Early Childhood Education Journal 35 (1): 83–88. doi: 10.1007/s10643-007-0175-6

- National Agency of Education. 2012. Förskoleklassen Är Till för Ditt Barn. En Broschyr Om Förskoleklassen [The Preschool Class Is for Your Child. A Brochure about the Preschool Class]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Nilholm, C. 2016. Teori i Examensarbeten – En Vägledning för Lärarstudenter [Theory in Essays – A Guide for Teacher Students]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Perry, B., S. Dockett, and A. Petriwskyj. 2014. Transitions to School: International Research, Policy and Practice. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Peters, S. 2010. “Shifting the Lens: Re-Framing the View of Learners and Learning During the Transition From Early Childhood Education to School in New Zealand.” In Educational Transitions: Moving Stories From Around the World, edited by D. Jindal-Snape, 68–84. New York: Routledge.

- Peters, S. 2014. “Chasms, Bridges and Borderlands: A Transitions Research ‘Across The Border’ From Early Childhood Education to School in New Zealand.” In Transitions to School: International Research, Policy and Practice, edited by B. Perry, S. Dockett, and A. Petriwskij, 105–116. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Petriwskyj, A. 2014. “Critical Theory and Inclusive Transitions to School.” In Transitions to School: International Research, Policy and Practice, edited by B. Perry, S. Dockett, and A. Petriwskij, 201–215. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Pianta, R. C., M. Kraft-Sayre, S. Rimm-Kaufman, N. Gercke, and T. Higgins. 2001. “Collaboration in Building Partnerships Between Families and Schools: The National Center for Early Development and Learning’s Kindergarten Transition Intervention.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 16 (1): 117–132. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(01)00089-8

- Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., and R. C. Pianta. 2000. “An Ecological Perspective on Children’s Transition to Kindergarten: A Theoretical Framework to Guide Empirical Research.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 21 (5): 491–511. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(00)00051-4

- Rogoff, B. 2003. The Cultural Nature of Human Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Seung Lam, M., and A. Pollard. 2006. “A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Children as Agents in the Transition From Home to Kindergarten.” Early Years 26 (2): 123–141. doi: 10.1080/09575140600759906

- Turner, V. 1969. Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Stage in Rites of Passage. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- van Gennep, A. (1908) 1997. Rites of Passage (M.B. Vizedom, and G.L. Caffee, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- van Gennep, A. 1960. The Rites of Passage. (B. V. Minika and G. L. Caffee, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Vogler, P., G. Crivello, and M. Woodhead. 2008. Early Childhood Transitions Research: A Review of Concepts, Theory, and Practice. Working Paper No. 48. The Hague, The Netherlands: Bernard van Leer Foundation.

- Vygotsky, L. (1934) 1986. Thought and Language (A. Kozulin, Trans. And Ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Wachs, T. D. 2000. Necessary but Not Sufficient: The Respective Roles of Single and Multiple Influences on Individual Development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Warner, K., K. Hull, and M. Laughlin. 2015. “The Role of Community in Special Education: A Relational Approach.” Interdisciplinary Connections To Special Education: Important Aspects To Consider 30 (A): 151–166. doi: 10.1108/S0270-40132015000030A008

- Wilder, J., and A. Lillvist. 2016. “Collaboration in Transitions From Preschool: Young Children with Intellectual Disabilities.” In Pedagogies of Educational Transitions, edited by N. Ballam, B. Perry, and A. Garpelin, 59–74. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Wilder, J., and A. Lillvist. 2017. “Hope, Despair and Everything in Between–Parental Expectations of Educational Transition for Young Children with Intellectual Disability.” In Families and Transition to School, edited by S. Dockett, W. Griebel, and B. Perry, 51–66. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Öhman, J. 2008. “Erfarenheter och Meningsskapande.” [Experiences and Meaning-Making.] Utbildning & Demokrati 17 (3): 25–46.