ABSTRACT

Practitioners working with young children in the provision of early childhood education (ECE) are often directed by state governments to mediate specific values through their pedagogical practice. This paper reports the findings from a small scale empirical research study exploring the pedagogy applied by ECE practitioners in this context. I argue that moral pedagogies, where children are positioned as constructors of knowledge about values, have the potential to support ECE practice in ways that respect and uphold children’s rights. Such an approach requires practitioners to adopt a critical stance and consider their epistemic beliefs about how children learn. I suggest that this process may be enhanced by practitioners’ reflecting on the positioning of children within pedagogical relationships through the lens of child rights.

Introduction

Pedagogy within early childhood education (ECE) can be understood as an everyday practice (Emilson and Johansson Citation2009) and an activity situated within the spaces occupied by children and adults. In this way pedagogy influences the ways in which learning takes place and the relationships that structure learning; pedagogy can be understood as a ‘relationship rather than a response or an intervention’ (Farquhar and White Citation2014, 821). This is not a passive or neutral process but requires an ethical and political practice (Moss Citation2019) of those working in ECE as they navigate external political and social discourses within ECE policy in England. In 2015 this policy agenda for ECE took a turn with the introduction of the Counter Terrorism and Security Act 2015 (Great Britain HM Parliament Citation2015). S.26 of this Act (hereafter referred to as the Prevent Duty) required organisations providing publicly funded early years childcare to have due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism. The statutory guidance implementing the Prevent Duty stated that providers receiving early education funding must promote Fundamental British Values as a specific measure to counter terrorism (Great Britain HM Government Citation2015). Fundamental British Values (FBV) are defined by government as democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance for those with different faiths and beliefs. The imposition of specific values, on both children and practitioners, is problematic as such values are not contextualised within sites of ECE (Robson Citation2019). This paper reports the findings from a small scale empirical study conducted in England which aimed to explore pedagogy applied by ECE practitioners as they implemented FBV. I argue that moral pedagogy provides an insight into the tensions operating within the ECE practitioners’ attempts at participatory practice in values education. I suggest that applying the lens of child rights may enhance an understanding of the positioning of children within the pedagogical relationship of values education.

Fundamental British values through the lens of values education and child rights

The implications for practitioners arising from the introduction of FBV as a statutory requirement in education in England have been the focus of critique within the academy. For example, Elton-Chalcraft et al. (Citation2017), writing within the context of initial teacher education in England, argue that the policy of FBV raises question of whether teachers become agents of state counter terrorism policy. Whilst these concerns are also relevant to ECE practitioners there are wide implications arising from FBV for ECE specifically in relation to values education. Values are ‘guiding principles in life’ (Schwartz Citation2012, 17) and values education is a practice through which children learn values as well as the skills reflected in those values (Halstead and Taylor Citation2000). The significance of values education in early childhood has long been argued; UNESCO (Citation2000) claim that the ‘value orientations of children are largely determined by the time they reach the age of formal schooling’ (2). Values education in early childhood can be explicit where it is directed by the state though policy or implicit within the practices of ECE provision (Thornberg Citation2016). This relationship between FBV, values education and pedagogy brings into question the status of young children.

As signatories to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (OHCHR Citation1989) state governments accept responsibilities to implement this framework for rights within legislation, policy and practice. Within the field of ECE policy and practice General Comment No 7 (OHCHR Citation2005) shapes knowledge and understanding of young children’s right to have their views respected in matters that affect her or him (MacNaughton, Hughes, and Smith Citation2007a). I argue that the imposition of FBV as specified set of values is problematic as it presumes young children would share these values and that they are not capable of forming values. Osler (Citation2015) emphasises the centrality of values in developing understandings of citizenship and contributing to a sense of belonging to a community. An approach to policy development and implementation that is consistent with the UNCRC would be to position children as social actors and citizens participating in public life (MacNaughton, Hughes, and Smith Citation2007b). This would require ECE practitioners to position themselves as ‘collaborators with children’ (MacNaughton, Hughes, and Smith Citation2007a, 168) by respecting children’s expertise in their own lives and securing their active participation as citizens. Such an approach would require a robust pedagogy given the implicit assumption within the FBV policy that values education is a process of the ‘transmission of these approved values to children’ (Halstead Citation1996, 9).

Pedagogies for values education

Pedagogy is a complex and often contested concept in ECE (Murray Citation2015). Here I explore the possibilities for pedagogy that enable both children and adults to navigate the requirement to promote FBV in ECE in ways that are respectful of child rights. Constructs of pedagogy are not without tension; for example, Siraj-Blatchford (Citation1999) proposed three features of early childhood pedagogy that are supportive of learning: instructional techniques, encouraging involvement and fostering engagement. All three place expectations on ECE practitioners to reflect on the positionality of both adults and children in the pedagogical relationship. Murray (Citation2015) argues that this leads to ‘the teacher as the empowered partner in the pedagogic relationship.’(p. 1720); any reflection on power operating in pedagogical relationships between adults and children has the potential to create new understandings of pedagogy. Yet the pre-determined FBVs are problematic in that they presume an instrumental pedagogy and a mandatory policy potentially constrains the emergence of alternative pedagogical paradigms (Farquhar and White Citation2014).

As a pedagogical practice values education engages children in a consideration of moral and political values (Thornberg Citation2016), therefore, moral pedagogies as a theory have the potential to support ECE practitioners in this complex task. Basourakos (Citation1999) proposes a theory that is a binary construct of a conventional moral pedagogy and a contextual moral pedagogy. Within a conventional moral pedagogy values are viewed as absolute and within this position the role of the ECE practitioner is to transmit a specified set of values to children. FBVs are an explicit set of values pre-determined by national policy; as such they assume a conventional moral pedagogy within ECE provision (Robson Citation2019). Alternatively within a contextual moral pedagogy ECE practitioners engage children in constructing their own understanding of moral values and practices. Such a position provides opportunities to further the UNCRC specifically Article 12 (right to express views) and Article 13 (right to freedom of expression) (OCHR 1989). In a study in the Australian context, Brownlee et al. (Citation2015) further explored moral pedagogies; they suggest that there is a relationship between the epistemic beliefs of ECE practitioners about how children learn and pedagogy. They found that practitioners working within a contextual moral pedagogy reflect on their epistemic beliefs and this leads them to position children as learners who construct values. I suggest that a contextual moral pedagogy becomes a participative space for children and practitioners where there is the potential to respect child rights.

Methodology

This small scale study explores the pedagogy operating within ECE as practitioners navigate the duty to promote FBV. By positioning the study within the interpretivist paradigm I aim to reveal the multiple understandings held by children and practitioners (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2005) of pedagogy in this context. Case study was a relevant approach as the phenomena under study, ECE pedagogy, was not separable from the context of the ECE provision (Yin Citation2003). The study was focused by asking this research question: How are FBV situated within the pedagogy in ECE?

Recruiting the research sites for this study was problematic. Inviting ECE provisions from within my existing networks in the field risked both bias but also potentially limited the breadth of perspectives on pedagogy. Six ECE provisions situated within a large and ethnically diverse city in England were invited to participate; this was a convenience approach to sampling (Leedy and Omrod Citation2012). Participants in this study were 18 ECE practitioners (3 from each setting) who had responsibility for leadership of pedagogy and children (aged 2–4) were invited to share documentation emerging from their engagement in the pedagogy.

Ethical considerations

My orientation as researcher places children as social actors, constructing and determining their lives (Dahlberg, Moss, and Pence Citation2013, 52). Following approval from the University’s research ethics committee I approached the ECE providers to negotiate access, recruit participants and seek informed consent. My entry to each research setting revealed the asymmetrical relationship of power that operate in research between the researcher and the participants but also between child and adult participants (Groundwater-Smith, Dockett, and Bottrell Citation2015). The discussion in each setting began with a dialogue with the gatekeeper (the manager of the ECE provision) about their procedures for gaining consent from children and adults to participate in research. For 5 out of the 6 settings the gatekeeper considered parents as the sole gatekeepers to children’s participation in research. This was an ethical dilemma as it precluded any views held by children about their participation in research. In order to minimise the power relations I negotiated that practitioners and parents would be informed by the ECE setting of the research and their consent sought through documentation and meetings with the researcher. Children were verbally informed of the research by both the ECE practitioners and the researcher. They were invited to give their verbal consent to participate in the project and this approach acknowledged that children may dissent (Dockett, Perry, and Kearney Citation2013).

Data collection

I reviewed pedagogical documentation as a method to gain insight into children’s participation in pedagogy. Stake (Citation1995) argues that the creators of documents are more expert observers than researchers. Here I position children as experts in pedagogy and creators or co-creators of pedagogical documentation. Pedagogical documentation is ‘trying to see and understand what is going on in the pedagogical work’ (Dahlberg, Moss, and Pence Citation2013, 154). During the fieldwork practitioners and children provided a walking tour of their learning environment. As part of the walking tour children were verbally invited by the researcher to share any document or artefact that showed how they planned and communicated activities from their daily experience in the setting. Pedagogical documentation, as a data collection tool to gain children’s perspectives, should not be used uncritically as the interpretation of documentation is frequently from an adult view point (Waller and Bitou Citation2011). I adopt a critical position knowing that relationships of power exist as I am listening to children through my active engagement with their documentation. In order to elicit ECE practitioners’ perspectives on the pedagogy I planned semi-structured interviews within each of the research settings. A topic guide supported the structure of the interview; this prompted participants to narrate examples of values education and provide their perspective on the pedagogy for each example. Interviews here are conceptualised as a social practice (Brinkman and Kvale Citation2015); they are an interaction between the researcher and participants situated in a specific context with a focus on generating knowledge.

Data analysis

Research conducted within the interpretivist paradigm is concerned with the ethical and respectful representations of participants (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2003). To ensure anonymity and confidentiality I adopted pseudonyms for the ECE providers and the participants. As part of a strategy of respectful engagement with the data I adopted a continuous cycle of revisiting the raw data. This was supported by a strategy of ‘jottings’ (Miles, Huberman, and Saldana Citation2014, 94) where I captured my reflections during the data analysis and made notes on emergent meanings related to values education across all sources of data. I subsequently challenged my emergent understanding of pedagogy underpinning values education by applying theory. Data is presented as a series of vignettes. Here the vignette is a focused description constructed by the researcher from the data (Miles, Huberman, and Saldana Citation2014, 94) of the pedagogical practice in values education.

Findings and discussion

In this Section I present three vignettes of pedagogical practice; each includes the pedagogical documentation and an account of the pedagogy. Subsequently I analyse the vignettes to provide a critical discussion of the pedagogy. Through this process I acknowledge that the process of writing and reading the vignettes reveals a range of learning. The vignettes evidence the participation of children in pedagogies that promote, for example, problem-solving, reflexivity and self-advocacy that are supportive of child rights ().

Vignette 1: Henna hands

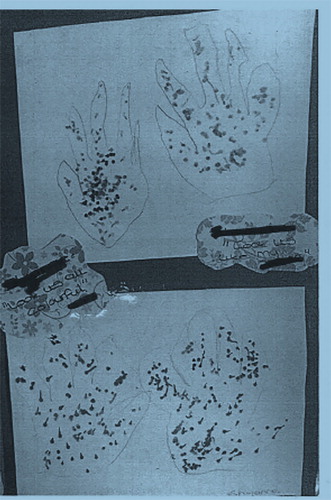

In the Middle House Day Nursery children put forward a large format book where they documented activities valued by them. Farah, the ECE practitioner, introduced this as the ‘Children’s Voice Book’ where children’s learning is documented, children referred to it as ‘Our book’. Children nominated documentation to be included in the book through the regular ‘children’s meeting’ in the nursery. Farah indicated that children can convene a meeting at any time to discuss any topic of interest or concern to them. This large format book is accessible to children at all times; Farah described how children revisit it and then share their interpretations with other children and adults in the nursery. This particular page of ‘Our Book’ included children’s drawings of their hands. Farah explained that children in the nursery had been listening to each other and asking questions about the celebrations for Eid in their families. Some children had henna tattoos on their hands. Farah stated that children experimented by making marks on paper and this was extended by adults to include drawing around hands and making marks on the images. Children engaged in this activity invited children and adults to come and draw hands. Farah suggested that this activity arose from children’s curiosity. From her perspective it provided opportunities for values education; she highlighted that children communicated respect for each other and that it led to shared understandings of different faith practices. Farah’s view was that engagement with the henna drawing was affirmative and inclusive of children from Muslim background who were in a minority in the nursery. Farah said that she had followed the children’s interests and took part in the hand drawing at their invitation. She facilitated children’s conversations about the drawings by asking questions about the henna hands ().

Vignette 2: Children’s planning meetings

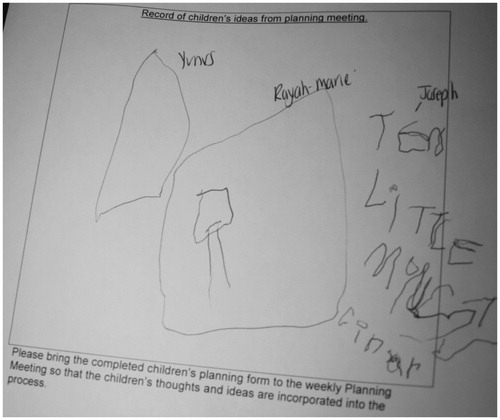

In the Lower Castle Community Nursery children put forward the documentation that recorded their ideas for activities in the forthcoming week. Rosa, the ECE practitioner explained that ‘Children’s Planning Meetings’ take place weekly between children and practitioners in order that children can identify and share their interests with each other and with adults. She stated that children are inducted into a structure for a meeting in order that they can take this forward. The process of induction is led by children. The role of the practitioner is to listen to the children and to act on the completed children’s planning form ensuring that children’s ideas can be incorporated in the weekly plan. In the children’s planning meeting children take the role of chair, minute taker or as a member of the meeting. The record of the meeting is then displayed in the nursery in place where children can refer to it but also alongside the ECE practitioners own weekly planning document. In this particular meeting (attended by 5 children and observed by 2 practitioners) children suggested that they wanted activities centred on the book Ten Little Monsters. Rosa reflected that as an ECE practitioner she found the children’s dialogues inspirational. She observed that children freely shared their knowledge and their ideas. Rosa saw these meetings as places of values education; where children experienced democratic practice and were trusted ().

Vignette 3: No peanuts

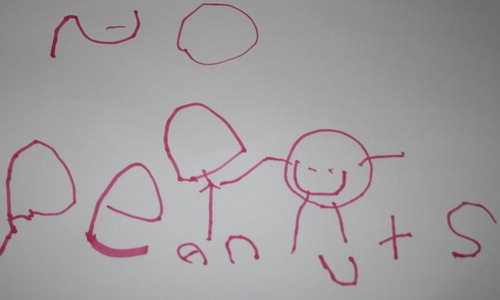

In the Upper Castle Community Nursery children put forward a series of posters; they were displayed prominently in the setting and communicated messages to parents about the policies of the nursery. Angela, the ECE practitioner, explained that children asked questions as to why adults did not respect the boundaries relating to the safety of all people in the nursery. She said that children and practitioners interpreted the policies by working out the practices in place to ensure a safe environment. Angela stated that children were invited by practitioners to suggest ways of communicating to adults; she reflected that this strategy acknowledged publicly that adults and children can work together to resolve a problem. She saw this as an example of children advocating for each other; the children were representing their views and this was an act of solidarity. The outcomes was a series of posters produced by children communicating a range of policies to adults including one reminding adults of the policy relating to peanuts. Angela stated that subsequently children then invited adults to engage with the posters when they came to collect them from the nursery. She felt that this activity had contributed to the nursery’s work on values education particularly in relation to care for the members of the nursery community.

Discussion of pedagogy

Pedagogy rich in values education

Each vignette provides an account that is rich in values education arising from children’s engagement in learning. Analysis of the vignettes revealed a range of values including for example empathy, solidarity, justice, respect and hope, In communicating the message of ‘No Peanuts’ children demonstrated values of care, justice and solidarity by taking action on behalf of all children in the ECE provision. By sharing ‘Henna Hands’ children demonstrated joy and respect for cultural mores within the diversity of families in their community. Values developed through the learning extended beyond the four FBVs imposed by government policy and in this sense they were unconstrained by the national political agenda of values education as an instrument of counter terrorism strategy in England (Robson Citation2019). This leads me to question how ECE practitioners adopt a pedagogy that enabled them to resist a powerful government discourse.

In this context, values education is implicit in pedagogy and practices of the ECE provisions (Thornberg Citation2016); values education is inseparable from the everyday pedagogical practice within the setting and it enables ECE practitioners to navigate the tensions arising from the prescription of four FBV and the assumption within national policy that values can be transmitted to children through pedagogy. The pedagogy adopted by ECE practitioners allowed for values to be situated and constructed within the context of children’s lives; this positioned values education as a practice though which children learn values as well as the skills reflected in those values (Halstead and Taylor Citation2000). In this way pedagogy was informed by the tacit knowledge and understanding held by ECE practitioners of children’s right to have their views taken into account in the ways in which national policy was implemented (MacNaughton, Hughes, and Smith Citation2007a).

Pedagogical documentation as an adult intervention

The pedagogy of values education made visible in this study positioned children as active participants in their learning; relationships between children and between adults and children were central to the pedagogy. In the vignette ‘Henna Hands’ such relationships enabled the development a shared knowledge and appreciation of cultural mores in families. This respects children’s agency and allows them opportunities to develop a sense of belonging in their community; this echoes Osler’s (Citation2015) findings that values are central to developing an understanding of citizenship. However, relationships between adult and children are not without tension and as Murray (Citation2015) suggests adults are the ‘empowered partner in the pedagogical relationship’ (p. 1720). In the vignette ‘Henna Hands’ this is reflected in the pedagogical documentation that arose from the relationship between adults and children. Farah’s intervention led to the children moving from mark making to drawing around hands. The children moved from a collective activity where they were working together creating marks to an individual activity where they made marks on outlines of their own hands. This brings into question whether the interventions by adults in the pedagogical documentation influenced children’s interpretations and communication of their ideas of Henna Tattoos. So although ECE practitioners respected children’s agency by following their interests they may have limited children’ agency and children’s rights specifically Article 13, the right to freedom of expression (OHCR 1989). The practice of adult intervention in the pedagogical documentation was a persistent theme arising in the analysis of data in this study. A further example is Vignette 2 the practice of Children’s Planning Meeting, where children made contributions to the planning of the curriculum in the coming week. Children led the meetings and sought children’s views and preferences. This activity was rich in values education; children demonstrated values of empathy, democracy, respect and care. Similarly, ECE practitioners respected children’s right to a voice about matters of concern to them (Article 12, UNCRC). However, the meetings were scheduled by adults to take place at a specific point in the week and children were required to record their decisions on a template designed by the ECE practitioners in the setting. My analysis raises questions about the extent to which ECE practitioners had the opportunity to engage in reflection about how the practice of pedagogical documentation could be developed to further children’s participation in values education. Within the pedagogical relationship ECE practitioners positioned themselves as ‘collaborators with children’ (MacNaughton, Hughes, and Smith Citation2007a, 168), however, reflection on their attempts to engage children as citizens in the pedagogical relationship may reveal how children’s agency is restricted.

Position of children in pedagogical relationships

ECE practitioners’ adopted a complex pedagogy that supported them in mediating the FBV in their practice; they recognised the ways in which children engaged in moral and political values in their daily lives. In the vignette ‘No Peanuts’ children’s attempts to engage adults to take action to make the ECE provision safer can be interpreted as a political act where children challenged the practices of adults. Such an approach is consistent with the UNCRC as it positions children as social actors actively participating in decision making and advocacy for the self and others. Practice can be viewed through the lens of a contextual moral pedagogy (Basourakos Citation1999) where children were positioned as constructors and co-constructors of values and values education is conceptualised as a situated practice. I argue that a contextual moral pedagogy support an understanding of how ECE practitioners provide opportunities for children to participate in the formation of values and are open to the perspectives of children that emerge from this process. Furthermore, it requires practitioners to reflect on their epistemic beliefs about how children learn (Brownlee et al. Citation2015); in this way practitioners positioned children as experts in their own lives and capable of theorising values. Similarly, I suggest that the contextual moral pedagogy applied by practitioners was critical as it enabled children to apply values in ways that affected their lives and the learning of all children in the setting.

Conclusion

Where ECE becomes subject to the dominant policy agenda of government, and in this case counter-terrorism policy, I found that ECE practitioners deployed a robust pedagogy that was both participatory and critical in order to sustain ECE as a forum for values education. By adopting a critical orientation ECE practitioners ‘seek to incorporate the silenced voices and perspectives’ of children (Christensen and Aldridge Citation2013, 20) within the pedagogy of values education. Viewed through the lens of a contextual moral pedagogy I suggest that ECE practitioners understood learning as a situated activity where children are positioned as competent. They recognised children’s agency and the ways in which children engage in projects of social and political significance in their lives. Central to this pedagogy is practitioners’ reflection on their epistemic beliefs about how children learn and a resistance to imposed values that assume the practitioners’ role is to transmit values. In this way pedagogy becomes a tool to support practitioners in navigating the implementation of government policy in ways that respect children’s agency and their right to have a view about matters of concern to them. This knowledge has implications for the initial training of ECE practitioners in England where a focus on developing reflective skills may support a critical consideration of government policy as part of the process of implementation. Reflections of ECE practitioners may generate a wider and critical debate about the role of the state in values education in early childhood.

I argue that a consideration of relationships is central to pedagogy in values education and this is supported by earlier work by Formosinho and Formosinho (Citation2016) exploring participatory pedagogy in ECE. Whilst practitioners respected children’s right to formulate values relevant to their lives I suggest that the process of pedagogical documentation was an area where practitioners intervened in ways that diminished children’s agency. Further research into pedagogical documentation that is respectful of children’s agency may lead to new knowledge in this area. This is highly relevant to ECE given the significance of values education at this time in England with the imposition of a specific set of values in ECE as part of the government’s counter terrorism strategy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Basourakos, J. 1999. “Moral Voices and Moral Choices: Canadian Drama and Moral Pedagogy.” Journal of Moral Education 28 (4): 473–489. doi: 10.1080/030572499103025

- Brinkman, S., and S. Kvale. 2015. Interviews. Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. London: Sage Publications.

- Brownlee, J. L., E. Johansson, C. Cobb-Moore, G. Boulton-Lewis, S. Walker, and J. Ailwood. 2015. “Epistemic Beliefs and Beliefs About Teaching Practices for Moral Learning in the Early Years of School: Relationships and Complexities.” Education 3-13 43 (2): 164–183. doi:10.1080/03004279.2013.790458.

- Christensen, L. M., and J. Aldridge. 2013. Critical Pedagogy for Early Childhood and Elementary Education. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Dahlberg, G., P. Moss, and A. Pence. 2013. Beyond Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 2003. “Introduction: The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research.” In The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues, edited by N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln, 1–14. London: Sage.

- Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln, eds. 2005. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- Dockett, S., B. Perry, and E. Kearney. 2013. “Promoting Children’s Informed Assent in Research Participation.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (7): 802–828. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2012.666289

- Elton-Chalcraft, S., V. Lander, L. Revell, D. Warner, and L. Whitworth. 2017. “To Promote, or Not to Promote Fundamental British Values? Teachers’ Standards, Diversity and Teacher Education.” British Educational Research Journal 43 (1): 29–48. doi: 10.1002/berj.3253

- Emilson, A., and E. Johansson. 2009. “Communicated Values in Teacher and Toddler Interactions in Preschool.” In Participatory Learning and the Early Years, edited by D. Berthelsen, J. Brownlee, and E. Johansson, 61–77. New York: Routledge and Taylor & Francis Group.

- Farquhar, S., and E. J. White, 2014. “Philosophy and Pedagogy of Early Childhood.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 46 (8): 821–832. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2013.783964

- Formosinho, J., and J. Formosinho. 2016. “Pedagogy-in-Participation, the Search for Holistic Practice.” In Assessment and Evaluation for Transformation in Early Childhood, edited by J. Formosinho, and C. Pascall, 26–57. London: Routledge.

- Great Britain HM Government (HMG). 2015. Prevent Duty Guidance: For England and Wales. Accessed May 7, 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/445977/3799_Revised_Prevent_Duty_Guidance__England_Wales_V2-Interactive.pdf.

- Great Britain HM Parliament. 2015. Counter Terrorism and Security Act. Accessed May 7, 2017. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/6/section/26/enacted.

- Groundwater-Smith, S., S. Dockett, and D. Bottrell. 2015. Participatory Research with Children and Young People. London: Sage Publications.

- Halstead, J. M. 1996. “Values and Values Education in Schools.” In Values in Education and Education in Values, edited by J. M. Halstead, and M. J. Taylor, 3–14. London: Falmer Press.

- Halstead, J. M., and M. J. Taylor. 2000. “Learning and Teaching about Values: A Review of Recent Research.” Cambridge Journal of Education 30 (2): 169–202. doi:10.1080/713657146.

- Leedy, P., and J. Omrod. 2012. Practical Research. New Jersey: Pearson.

- MacNaughton, G., P. Hughes, and K. Smith. 2007a. “Early Childhood Professionals and Children’s Rights: Tensions and Possibilities around the United Nations General Comment No 7 on Children’s Rights.” International Journal of Early Years Education 15 (2): 161–170. doi: 10.1080/09669760701288716

- MacNaughton, G., P. Hughes, and K. Smith. 2007b. “Young Children’s Rights and Public Policy: Practices and Possibilities for Citizenship in the Early Years.” Children & Society 21 (6): 458–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2007.00096.x

- Miles, M. B., M. A. Huberman, and J. Saldana. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Moss, P. 2019. Alternative Narratives in Early Childhood: An Introduction for Students and Practitioners. London: Routledge.

- Murray, J. 2015. “Early Childhood Pedagogies: Spaces for Young Children to Flourish.” Early Child Development and Care 185 (11–12): 1715–1732. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2015.1029245

- OHCHR. 1989. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Geneva: OHCHR.

- OHCHR. 2005. General Comment No. 7. Implementing Child Rights in Early Childhood. Geneva: OHCHR.

- Osler, A. 2015. “Human Rights Education, Postcolonial Scholarship, and Action for Social Justice.” Theory & Research in Social Education 43 (2): 244–274. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2015.1034393

- Robson, J. van Krieken. 2019. “How Do Practitioners in Early Years Provision Promote Fundamental British Values?” International Journal of Early Years Education 27 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1080/09669760.2018.1507904.

- Schwartz, S. H. 2012. “An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values.” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2 (1). doi:10.9707/2307-0919.1116. Accessed May 7, 2017. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1116&context=orpc.

- Siraj-Blatchford, I. 1999. “Early Childhood Pedagogy: Practice, Principles and Research.” In Understanding Pedagogy and its Impact on Learning, edited by P. Mortimer, 20–45. London: Chapman.

- Stake, R. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. London: Sage Publications.

- Thornberg, R. 2016. “Values Education in Nordic Preschools: A Commentary.” International Journal of Early Childhood 48 (2): 241–257. doi: 10.1007/s13158-016-0167-z

- UNESCO. 2000. Framework for Action on Values Education. Paris: UNESCO.

- Waller, T., and A. Bitou. 2011. “Research with Children: Three Challenges for Participatory Research in Early Childhood.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 19 (1): 5–20. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2011.548964

- Yin, R. K. 2003. Applications of Case Study Research. London: Sage Publications.