ABSTRACT

Language ability plays a major role in children’s future development. In the present study, the effect of three interactive reading approaches on children’s language ability was investigated through a pre-posttest design. Participants were N = 73 children (aged 4–6) from three early childhood education classrooms. Classrooms were assigned to one of three reading approaches: (1) traditional interactive reading, (2) interactive reading with focused attention, and (3) interactive reading using a mindmap. The hypothesis was that the effect of the mindmap approach would be greater than the effect of the other two reading approaches. Children’s productive vocabulary, receptive vocabulary, listening comprehension skills, and narrative skills were measured. Results indicated no differences between the effects of the three reading approaches. However, after the intervention period, children’s language ability was significantly improved. This indicates that different interactive reading approaches are beneficial for children’s language ability, even after a short intervention period of four weeks. Future large-scale, longitudinal research should follow-up on the present study in order to indicate whether the use of mindmaps during interactive reading is even more effective than other reading approaches.

Introduction

The development of language ability is one of the main challenges during early childhood and plays a major role in children’s social development. Research has shown, for example, that children with a low level of language ability are more often rejected by their peers (e.g. Van der Wilt et al. Citation2016, Van der Wilt et al. Citation2018). In addition, early language ability is an important predictor of later success in school: Young children with poor language ability learn to read and write in a slower pace than their peers (Conti-Ramsden and Durkin Citation2012). It has been demonstrated that differences in children’s level of language ability often remain visible during their entire school career (Teunissen and Hacquebord Citation2002). The development of language ability should therefore be promoted at a young age, and education might play an important role in this case (Conti-Ramsden and Durkin Citation2012). An effective way to promote various aspects of children’s language ability is reading. In fact, it has been shown that young children who are often read to, have better vocabulary and early literacy skills (such as alphabetic knowledge and phonological sensitivity) than children who are less often read to (for meta-analyses, see Mol and Bus Citation2011; Mol, Bus, and de Jong Citation2009). Building on this body of research, the present exploratory study examined the effects of three interactive reading approaches on children’s language ability in early childhood education.

Language ability is a complex and multifaceted concept. It consists of different, interrelated aspects that enable a child to gain knowledge and communicate with others (Conti-Ramsden and Durkin Citation2012). In the current study, the following aspects of language ability were taken into account: productive vocabulary, receptive vocabulary, listening comprehension skills, and narrative skills. Previous research has demonstrated that all four language aspects are related to reading. First, it has been argued that reading contributes to the development of (both productive and receptive) vocabulary, because it enables children to derive the meaning of new words from the context of the text (Cain, Oakhill, and Elbro Citation2003). Indeed, research has shown that young children who are often read to have better developed vocabulary skills (DeTemple and Snow Citation2003; Mol, Bus, and de Jong Citation2009). Second, it has been demonstrated that reading to young children positively contributes to the development of listening comprehension skills, which, in turn, contributes to later reading skills (Sénéchal and LeFevre Citation2002; Snow Citation2002). Finally, Lever and Sénéchal (Citation2011) investigated the effect of dialogic reading, a shared reading activity that involves elaborative questioning techniques. Besides gains in productive vocabulary, results indicated that the dialogic reading intervention significantly enhanced children’s narrative skills (Lever and Sénéchal Citation2011; see also O’Neill, Pearce, and Pick Citation2004; Snow et al. Citation2007).

The current study was specifically focused on early childhood education. In early childhood education, shared book reading is an important activity (Bus, Van IJzendoorn, and Pellegrini Citation1995; Mol et al. Citation2008). Reading books and stories together can be beneficial from multiple perspectives. It allows children, for example, to learn about the structure of books: Books contain characters and locations, and most of them are about a certain problem. Shared book reading also teaches children how to engage with books and makes them aware of letter-sound relations, which are foundational to learning to read (Lonigan and Whitehurst Citation1998; Sulzby Citation1985; Zucker, Ward, and Justice Citation2009). In addition, it provides children the opportunity to expand their knowledge, as books describe situations, places, people, problems, and feelings that children have not (yet) encountered or experienced themselves (Gosen Citation2012; Hayes and Ahrens Citation1988). Picture books are highly suitable for shared reading, because of their clear story-lines and strong plots. As children in early childhood education do not yet read or write conventionally, pictures are of major importance for the understanding of a story. In fact, combining verbal or written information with pictures might be crucial in acquiring a coherent and complete picture of a text or story (De Koning and van der Schoot Citation2013). This is in line with the dual coding theory, stating that information is better remembered when it is presented both visually and verbally (Paivio Citation1991).

In early childhood education, the promotion of language ability is increasingly becoming an interactive process of meaning making. An important assumption behind interactive language teaching is the idea that language in itself is interaction (Elsäcker et al. Citation2009; see also Rivers Citation1987). Shared book reading is a well-known example of an activity that has become more and more interactive. Nowadays, the most popular shared reading method is called interactive book reading (Ghonem-Woets Citation2008; Milburn et al. Citation2014; Mol, Bus, and de Jong Citation2009). Compared to passive book reading, interactive book reading requires children to adopt a more active role as, for example, the teacher asks children story-related questions and encourages them to respond to the story (Mol, Bus, and de Jong Citation2009; Mol et al. Citation2008). Especially open questions allow children to talk about their own ideas and experiences in relation to the story. It is through challenging conversations that children become inspired to engage in a story. Research has shown that interactive reading is a valuable reading method as it promotes the language development of young children, and the interactions during shared picture book reading are important predictors of children’s further language development (Droop et al. Citation2005; Mol et al. Citation2008; Sulzby and Teale Citation2003).

A relatively recent development in education that builds on the theory about visualization (Paivio Citation1991) is the use of mindmaps. A mindmap can be seen as a particular type of graphic organizer. Graphic organizers are tools that readers can use to organize information in a text in a systematic manner by using lines, arrows, and pictures (Kim et al. Citation2004; see also Ilter Citation2016). Graphic organizers are useful in making meaningful relations between important concepts in a story and in visually presenting the story in a clear manner (Birbili Citation2006; Darch and Eaves Citation1986). By using a mindmap, students are more actively engaged in their own learning process (Edwards and Cooper Citation2010). Besides, Farrand, Hussain, and Hennessy (Citation2002) showed that the use of mindmaps can have a positive effect on learning outcomes: Second and third year medical students who used mindmaps while they learned for their exams knew more about the subject matter than students who did not use mindmaps. In addition, the study of Ilter (Citation2016) indicated that the use of graphic organizers improved fourth-graders’ word recognition. The review of Kim et al. (Citation2004) also showed that graphic organizers in general can have a positive influence on the learning outcomes of students with learning disabilities, because the use of graphic organizers enhanced their reading comprehension. Finally, in research of Carney and Levin (Citation2002) and Vekiri (Citation2002) it was demonstrated that information that was presented in text and pictures was effective with regard to students’ learning from texts and graphics.

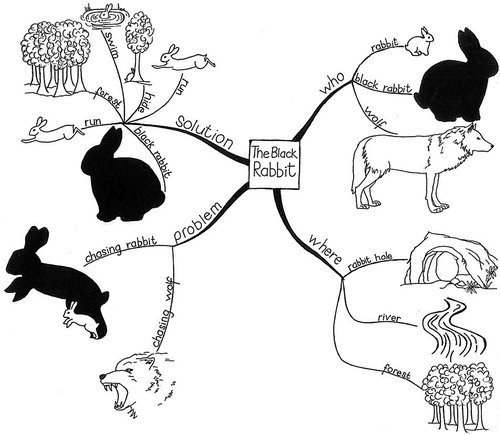

But how can mindmaps be used in the context of (early childhood) education? To this end, Tony Buzan (Citation2003) developed an approach in which mindmaps can be used in order to understand a text. Specifically, the main subject of a text is placed in the centre of a page. From there, lines are drawn to represent an important concept. Each line can be subdivided into smaller lines, representing sub concepts. Based on the work of Buzan, Dutch pre-school teacher Rianne Hofma developed an approach to use mindmaps with children aged 4–6 years (Hofma and van der Veen Citation2015). This approach consists of multiple reading sessions in which four specific questions are asked by the teacher to focus children’s attention on specific aspects of the story. Each session focusses on one question and afterwards one of the branches of the mindmap is constructed. The specific questions are ‘Who is this story about?’ (the ‘who-branch’), ‘Where does this story take place?’ (the ‘where-branch’), ‘What is the main problem in this story?’(the ‘problem-branch’), and ‘What is the solution?’ (‘solution-branch’). The questions are in line with the structure of most stories. That is, stories are often focused on specific characters, one or more locations and a main problem with a related solution (Lever and Sénéchal Citation2011). The questions regarding problems and solutions are likely to be more difficult than the two preceding questions as they require children to interpret and connect different events and make inferences from the story. By asking these four specific questions, children can focus on one aspect of the story and clarify the structure of the story for themselves (Michaels and Cazden Citation1986).

Prior research into the effect of mindmaps focusing on students in higher grades of elementary school, high school, or higher education has shown that the use of mindmaps or graphic organizers in general has a positive effect on children’s comprehension of a text (Kim et al. Citation2004; Merchie and Van Keer Citation2016). However, so far, no studies have examined the effect of using mindmaps on young children’s language ability and story comprehension. In the present study, we explored the possibilities and effectiveness of using mindmaps during interactive reading on children’s language ability in early childhood education. As young children cannot yet read conventional print, a combination of pictures and words was used to enable children to read the mindmap on their own. In order to explore the use and effectiveness of mindmaps on different aspects of language ability, the present study compared the effect of three interactive book reading approaches: (1) traditional interactive reading, (2) interactive reading with focused attention, and (3) interactive reading using a mindmap. Based on the effectiveness of graphic organizers in older children, the hypothesis was that using mindmaps during interactive reading would be more effective in improving children’s language ability than the other two reading approaches.

Method

Ethical considerations

The present study was part of a larger research project into the effect of several shared reading approaches, including the use of mindmaps, in early childhood education (Boerma et al. Citationin preparation.). For the complete research project, approval was obtained from the Permanent Committee of Science and Ethic of the Faculty of Behavioural and Movement Scienes, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Prior to the study, teachers who agreed to participate were informed about the purpose and the procedures of the research. Active informed consent was asked from children’s parents. For the current exploratory study, all parents gave consent to participate. In addition, participation remained completely voluntary and children could indicate at any moment that they wanted to stop participating in the study (although none of them did). All data sampled during the study were carefully and anonymously processed and saved. Furthermore, data were only used for research purposes and not distributed to others. No names of schools, children, or teachers were used in publications and presentations.

Participants

The total sample consisted of N = 73 children (42 boys and 31 girls) with aged between 3.58 and 6.17 years (M = 5.06, SD = 0.59). Children came from three early childhood education classrooms: Class 1 (n = 28), Class 2 (n = 20), and Class 3 (n = 25). Class 2 was situated at a primary school in an urban part of the Netherlands. The other two classes were from the same primary school in a rural part of the Netherlands. Classes were assigned to one of the three reading approaches: Class 1 to the traditional interactive reading approach, Class 2 to the interactive reading with focused attention approach, and Class 3 to the interactive reading using a mindmap approach. shows the sample characteristics for each reading approach separately.

Table 1. Sample characteristics by reading approach.

Procedure

In each class, the same picture book was read three times (once a week for three weeks). The picture book selected for the present study is called ‘The Black Rabbit’ (Leathers Citation2013). The manner in which this book was read depended on the reading approach to which the class was assigned. The reading approaches were applied by the children’s own teacher who followed the instructions described in the detailed manual as closely as possible. The three reading approaches are shortly described below. shows the activities carried out in each reading approach. Different aspects of language ability were measured before and after the intervention period.

Table 2. Description of activities of the three reading approaches.

Traditional interactive reading. In the traditional interactive reading approach, the emphasis was on asking questions before, during, and after reading the book. The manner in which the book was read was very interactive: Children could interrupt whenever they wanted. The first time the book was read, the focus was on predictions about the story. The second time, the teacher asked children to concentrate on difficult words and encouraged them to ask questions about important concepts. The last time the book was read, the teacher talked with the children about the feelings of the main characters.

Interactive reading with focused attention. In the interactive reading with focused attention approach, each time one specific question was asked before reading the book. The manner in which the book was read was quite strict as the story was interrupted as little as possible. Before reading the book for the first time, the teacher asked children to concentrate on the characters: ‘Who is this book about?’. The second time, children were encouraged to focus on the locations: ‘Where does the story take place?’. The last time, children were asked two specific questions: ‘What are the main problems and how are they solved?’.

Interactive reading using a mindmap. In the interactive reading using a mindmap approach, the teacher asked the same specific questions before reading the book as in the interactive reading with focused attention approach. In addition to these questions, parts of a mindmap were constructed. After reading the book for the first time, the first branch of the mindmap was made: the ‘who-branch’. The second time, the teacher and children created the second branch: the ‘where-branch’. Finally, after reading the book for the third time, the mindmap was completed by adding the ‘problem-branch’ and the ‘solution-branch’. An example of a mindmap that was constructed in this study, is shown in .

Measures

Productive vocabulary. Children’s productive vocabulary was measured using the thematic vocabulary assessment test (TVAT), a self-developed thematic vocabulary test (see Adan-Dirks Citation2012; van der Veen, Dobber, and van Oers Citation2016). This test consisted of fifteen words and expressions selected from the picture book ‘The Black Rabbit’ (Leathers Citation2013). Test administrations were individually conducted by trained test assistants and children were asked to verbally explain the meaning of each word. For example, one item goes as follows: ‘What is loneliness?’ If the child provided a vague or incomplete response, the test assistant encouraged the child to clarify: ‘Have you heard this word before? What do you think it is about?’ The test administration took approximately ten minutes. In scoring the test, children received one point for each correct description. Total scores were calculated by summing the number of correct items, so scores could range from 0 to 15. The reliability of the test was – depending on the measurement occasion – low or acceptable (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.57 for the pretest and Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.70 for the posttest).

Receptive vocabulary. Children’s receptive vocabulary was measured with the Dutch version of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – III (Schlichting Citation2005). The test consists of a picture book with 204 items (17 sets of 12 items), each containing four black-and-white drawings. The so-called starting set depends on the participant’s age and the final set is the set in which the participant makes nine or more errors. In the present study, children were individually tested by a trained test assistant. Each time, the test assistant read a word aloud and asked the child to point to one of the four pictures that suited the word best. For example, one item goes as follows: ‘Could you point to the picture of a person who is laughing?’ In this case, participants could choose among pictures of a person who is crying, who is drinking tea, who is looking shocked, and who is laughing. The total administration of the test took approximately ten minutes. A raw score was calculated by subtracting the total number of errors from the last completed item number. A standardized score, the Word Comprehension Quotient (WCQ), was obtained based on this raw score using a table providing age-corrected normative scores. Previous research into the reliability of the test has indicated that its internal consistency is good (average Guttman’s Lambda-2 coefficient of .93 for children aged 4–7 years; Schlichting Citation2005).

Listening comprehension skills. The subscale Critical Listening of the Cito Language for Preschoolers was used to assess children’s listening comprehension skills (Lansink Citation2009). The Cito Language for preschoolers is a standardized test for language assessment in early childhood education and contains several subscales (Lansink Citation2009). The complete test consists of two versions: a test with 48 items for 4-to-5-year-olds and a test with 60 items for 5-to-6-year-olds. In the current study, eight items of each version of the subscale Critical Listening were randomly selected. One set was used as a pretest and the other set was used as a posttest. The test was plenary administered by the children’s own teacher. Each time, the teacher read a sentence aloud and children were required to draw a line under the corresponding picture on their answer sheet. For example: ‘Loes sits on the back of dad’s bicycle. Draw a line under that picture’. Children’s answers were dichotomously scored (1 point for a correct answer, 0 points for an incorrect answer). Total scores were calculated by summing the number of correct items. Therefore, scores could range from 0 to 8. Previous research indicated that the test is reliable (Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.87; Driessen Citation2016). However, in the current study a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.37 was found for the prestest and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.35 was found for the posttest. This might be explained by the small number of selected items that was used in this study.

Narrative skills. Narrative skills were assessed using the subscale Narrative Task of the Cito Language Test for All Children. This subscale measures the verbal abilities of children aged 4–9 and has two versions (Verhoeven and Vermeer Citation2006). In the present study, one version was used as a pretest and the other version was used as a posttest. The test was individually administered by a testassistent. During the test administrations, children were asked to tell a story based on a series of pictures that was led in front of them. They were first allowed to look carefully at the pictures and were subsequently asked to tell the corresponding story in such a way that someone who could not see the pictures could still understand it. Children’s stories were recorded using a voice recorder and were analyzed afterwards by scoring 16 items, each describing an aspect of the story (e.g. ‘The balloon flies away’). Each item was scored with a 0 or a 1, depending on whether the answer was correct or not. This allowed the scores to range between 0 and 16. The test has been found to be reliable with a Cronbach’s Alfa of 0.90 (Verhoeven and Vermeer Citation2006), although a lower Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.67 was found in the current study.

Analyses

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS), version 24. With regard to the pre-tests, 10.7% of the values were missing. In addition, 13.4% of the data on the posttests were missing. Missing data were imputed for both pre- and posttests after finding no statistically reliable deviation from randomness (Little’s MCAR test, X2(40) = 48.10, p = .178 and Little’s MCAR test, X2(137) = 116.63, p = .896, respectively). The imputed dataset was used in subsequent analyses. Normality assumptions were checked. Although Shapiro Wilks Normality tests indicated most variables (both on the pre- and posttest) significantly deviated from a normal distribution, visual inspection of Q-Q plots indicated that our data followed a normal distribution. Nonetheless, outcomes of our analyses should be carefully interpreted.

In order to investigate whether the different aspects of language ability were interrelated and whether age was related to these aspects, Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficients (r) were calculated. In addition, in order to examine whether the three reading approaches differed in their effect on the different aspects of language ability, mixed between-within analyses of variance were conducted. Given the relatively small sample size and significant results from the Shapiro Wilks Normality tests, analyses were also performed using non-parametric tests (i.e. Spearman Rank Order Correlations). As these analyses yielded the same results, they are not reported here.

Results

Preliminary analyses

In , the means and standard deviations of pre- and posttest scores for each main variable are displayed.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables divided by reading approach.

Outcomes of Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients indicated that most of the aspects of language ability were intercorrelated (). However, on both pre- and posttest, no correlation was found between receptive vocabulary and narrative skills. In addition, no relation was found between listening comprehension skills and narrative skills on the posttest. On pre- and posttests, age was positively related to productive vocabulary and narrative skills: Older children scored higher on these skills than younger children. However, no relationship was found between age and receptive vocabulary and between age and listening skills. The fact that both aspects were measured with an age sensitive test could explain the absence of a relationship between these variables.

Table 4. Pearson correlations between different aspects of language ability and age.

Differences between interactive reading approaches in their effect on language ability

Mixed between-within subjects analyses of variance were conducted to investigate the difference in effect between three reading approaches on different aspects of language ability. A 2 × 3 design was defined with pre- and posttest as within-factor and the three reading approaches as between-factor (). For all language aspects, the interaction effect between the within and the between factor was not significant. This indicates that the effect of the three reading approaches on language ability did not differ. The between subject effects were also non-significant. This indicates that the scores on the posttest of language ability did not differ between the three reading approaches. There was a significant effect of the within subject on productive vocabulary, receptive vocabulary, and on listening comprehension skills: children scored significantly higher on these posttests than on these pretests. The within subject effect on narrative skills was not significant: children did not score higher on this posttest than on the pretest.

Table 5. Interaction effects, within-, and between subjects effects for main variables.

Discussion

In this exploratory study, the effect of three reading approaches on several aspects of language ability of young children was investigated. Outcomes indicated that there was no difference between the three reading approaches in their effect on language ability. This outcome is not in line with our expectation that interactive reading using a mindmap would be more effective than the other two reading approaches.

Despite the fact that the three reading conditions did not differ in their effect on language ability, some interesting outcomes were found with regard to the effect of these reading approaches. Specifically, three out of four aspects of language ability, measured in the present study, were significantly improved: Children obtained higher scores on the posttests compared to the pretests. This was the case for productive vocabulary, receptive vocabulary, and narrative skills. With regard to productive vocabulary, the thematic vocabulary test consisted of fifteen words that were chosen from the picture book ‘The Black Rabbit’ (Leathers Citation2013), the book that was read during the intervention period. The improvement on this test can be explained by the specific approach regarding vocabulary teaching: The words of the picture book were consistently and frequently presented and discussed during the book reading activities. This shows that semantizing (clarifying meanings) and consolidating (repeating) words are important strategies for vocabulary teaching. This is consistent with research into vocabulary teaching methods (e.g. Henderson, Weighall, and Gaskell Citation2013; Verhallen Citation2010). For example, research has shown that a specific approach with attention to the meaning of words is important (Verhallen Citation2010). It is important that children understand the meaning of words and can use words in a meaningful context. If words are meaningful for children, they will remember them better (see also Van Oers and Duijkers Citation2013).

Besides productive vocabulary, receptive vocabulary improved as well. Although research has shown that young children who are read to, know a larger amount of words and learn how to derive the meaning of words based on the story context (i.e. Cain, Oakhill, and Elbro Citation2003; Mol, Bus, and de Jong Citation2009), it is rather surprising that this could be achieved in such a short-term intervention. This is especially surprising because the words that were assessed by the test to measure receptive vocabulary were completely unrelated to the content of the intervention. Finally, listening comprehension skills were significantly improved over time. This is in line with research demonstrating that shared reading has positive effects on listening skills (e.g. Freed Citation2017; Isbell Citation2004). Research of Freed (Citation2017) showed that asking questions before, during, or after reading results in improvements in listening comprehension skills. Especially asking questions during reading seems to be effective in the case of young children (Freed Citation2017). In all three reading approaches, story-related questions were asked about the story. For example, in the interactive reading with focused attention approach and interactive reading using a mindmap approach, children’s attention was focused on a specific part of the story by asking questions before reading the book. In addition, in the traditional interactive reading approach, children were asked questions about the story as well. Interestingly, the listening comprehension test that was used did not resemble the different reading approaches; Children significantly improved on this test independent of reading approach. This might suggest that children were able to apply what they had learned during the intervention in a new situation (i.e., the test).

In contrast to the aforementioned aspects of language ability, narrative skills were not significantly improved after the intervention period. An explanation might be that the test was too different from what had happened during the intervention period. During the test administration of narrative skills, children were required to tell a story based on a series of pictures. These pictures were not at all related to the picture book ‘The Black Rabbit’. In addition, the ability to tell a story based on pictures was not practiced during the intervention period. This might explain why these scores did not increase. In fact, research has shown that in order to assess the development in language ability, it is important to stay as close as possible to the regular situation in which the child uses language (Adan-Dirks Citation2012).

A possible explanation for the fact that no differences were found between the three reading approaches in their effect on language ability might be found in the instruction manuals. Teachers were asked to follow these manuals carefully, but when we take a closer look at these manuals, one could question whether the manuals of the three different reading approaches differed sufficiently from one another. For example, in both the interactive reading with focused attention approach as well as in the interactive reading using a mindmap approach, the same specific questions were asked before reading the picture book. In addition, as the interactive book reading approach encouraged interaction between teacher and children, it is possible that similar questions were asked in the interactive reading approach as well. Furthermore, each reading approach paid a lot of attention to the pictures in the picture book. The similarities between the reading approaches might explain why the approaches did not differ in their effect on language ability.

The current study had several limitations that need to be addressed. One limitation concerns the sample size. Participating classes were assigned to three reading approaches, but each reading approach consisted of only one class. In addition, the number of schools was limited as only two schools participated. The sample was, therefore, insufficiently diverse and our study underpowered. Future research should, therefore, contain a larger, randomly selected, and more heterogeneous sample. A second limitation is the low reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) of some of the tests that were used in the present study and the possibility of test-retest effects. Future studies are encouraged to consider more reliable tests and include different versions of tests to avoid a possible learning effect. A third limitation regards the duration of the intervention period: A four-week-period might be too short to detect meaningful differences between reading approaches in their effect on children’s language ability. Slavin (Citation2008), for example, argues that interventions with a short duration are generally low in external validity. Furthermore, teachers are generally not familiar with interactive reading using mindmaps and need a sufficient amount of time to adopt this new approach. Therefore, future studies could adopt a longitudinal design to indicate whether the use of mindmaps adds to the effectiveness of interactive book reading, with enough time (both in span of time and hours spend on profession development) for teachers’ professional development (Van Veen, Zwart, and Meirink Citation2012). Given the exploratory nature of the current study and the aforementioned limitations, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. However, this study does provide some interesting insights that are useful for designing future studies and are informative for early childhood teachers that want to make their book reading activities more interactive.

To conclude, the present study indicated that three different reading approaches were effective in improving several aspects of language ability, namely productive vocabulary, receptive vocabulary, and listening comprehension skills. This indicates the importance of interactive reading in early childhood education and supports teachers that adopt shared book reading in their classroom. Future research, including a longer intervention period and a larger sample, can investigate whether the use of mindmaps (and/or or book reading with focused attention) adds to the effectiveness of interactive book reading on language ability. Such outcomes can improve recent developments in early childhood education that focus on interactive and meaningful education. Finally, the different interactive reading approaches used in the current study can be adopted by early childhood teachers in order to make their book reading activities more dialogic, interactive, diversified, and challenging.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adan-Dirks, R. 2012. “Assessing Vocabulary Development.” In Developmental Education for Young Children: Concept Practice and Implementation, edited by B. van Oers, 87–104. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

- Birbili, M. 2006. “Mapping Knowledge: Concept Maps in Early Childhood Education.” Early Childhood Research and Practice 8 (2). http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v8n2/birbili.html.

- Boerma, I., F. van der Wilt, R. Bouwer, M. van der Schoot, and C. van der Veen. in preparation. “Mind mapping during interactive book reading in early childhood classrooms: Does it support young children’s language abilities?”

- Bus, A. G., M. H. Van IJzendoorn, and A. D. Pellegrini. 1995. “Joint Book Reading Makes for Success in Learning to Read: A Meta-Analysis on Intergenerational Transmission of Literacy.” Review of Educational Research 65 (1): 1–21.

- Buzan, T. 2003. Mind Maps for Kids: An Introduction. New York, NY: Harpercollins Publishers.

- Cain, K., J. V. Oakhill, and C. Elbro. 2003. “The Ability to Learn New Word Meanings from Context by School-age Children with and Without Language Comprehension Difficulties.” Journal of Child Language 30 (3): 681–694.

- Carney, R. N., and J. R. Levin. 2002. “Pictorial Illustrations Still Improve Students’ Learning from Text.” Educational Psychology Review 14 (1): 5–26.

- Conti-Ramsden, G., and K. Durkin. 2012. “Language Development and Assessment in the Preschool Period.” Neuropsychology Review 22 (4): 384–401. doi:10.1007/s11065-012-9208-z.

- Darch, C., and R. C. Eaves. 1986. “Visual Displays to Increase Comprehension of High School Learning-Disabled Students.” The Journal of Special Education 20 (3): 309–318.

- De Koning, B. B., and M. van der Schoot. 2013. “Becoming Part of the Story! Refueling the Interest in Visualization Strategies for Reading Comprehension.” Educational Psychology Review 25 (2): 261–287. doi:10.1007/s10648-013-9222-6.

- DeTemple, J., and C. E. Snow. 2003. “Learning Words from Books.” In On Reading Books to Children: Parents and Teachers, edited by A. van Kleeck, S. A. Stahl, and E. B. Bauer, 16–36. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Driessen, G. 2016. “Zoals de Ouden Zongen, Piepen de Jongen? De Taal van Ouders en Taal en Taalvaardigheid van hun Kinderen [The Language of Parents and Language Profiency of Their Children].” Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics 5 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1075/dujal.5.2.03dri.

- Droop, M., S. Peters, C. Aarnoutse, and L. Verhoeven. 2005. “Effecten van Stimulering van Beginnende Geletterdheid in Groep 2 [Effects of Early Language Teaching in Preschool].” Pedagogische Studien 82 (2): 160–180.

- Edwards, S., and N. Cooper. 2010. “Mind Mapping as a Teaching Resource.” The Clinical Teacher 7 (4): 236–239.

- Elsäcker, W., A. van der Beek, J. Hillen, and S. Peters. 2009. De taallijn: Interactief taalonderwijs in groep 1 en 2 [Interactive Language Teaching in Preschools]. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Expertisecentrum Nederlands.

- Farrand, P., F. Hussain, and E. Hennessy. 2002. “The Efficacy of the Mind Map Study Technique.” Medical Education 36 (5): 426–431. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01205.x.

- Freed, J. 2017. “Assessing School-Aged Children’s Inference-Making: The Effect of Story Test Format in Listening Comprehension.” International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 52 (1): 95–105. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12260.

- Ghonem-Woets, K. 2008. Elke dag boekendag! Verslag van een onderzoek naar het voorlezen van prentenboeken in groep 1 en 2. [Research Report of Book Reading in Preschools]. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Stichting Lezen.

- Gosen, M. 2012. “Tracing Learning in Interaction. An Analysis of Shared Reading of Picture Books at Kindergarten.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, the Netherlands.

- Hayes, D. P., and M. G. Ahrens. 1988. “Vocabulary Simplification for Children: A Special Case of ‘Motherese’?” Journal of Child Language 15 (02): 395–410.

- Henderson, L., A. Weighall, and G. Gaskell. 2013. “Learning New Vocabulary During Childhood: Effects of Semantic Training on Lexical Consolidation and Integration.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 116 (3): 572–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2013.07.004

- Hofma, R., and C. van der Veen. 2015. “Mindmappen met Kleuters. Je Kunt er Niet Vroeg Genoeg mee Beginnen! [Mind Mapping with Preschoolers. You can’t Start Early Enough].” MeerTaal 2 (2): 19–21.

- Ilter, I. 2016. “The Power of Graphic Organizers: Effects on Students’ Word-Learning and Achievement Emotions in Social Studies.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 41 (1): 42–64. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2016v41n1.3

- Isbell, R. 2004. “The Effects of Storytelling and Story Reading on the Oral Language Complexity and Story Comprehension of Young Children.” Early Childhood Education Journal 32 (3): 157–163. doi: 10.1023/B:ECEJ.0000048967.94189.a3

- Kim, A.-H., S. Vaughn, J. Wanzek, and S. Wei. 2004. “Graphic Organizers and Their Effects on the Reading Comprehension of Students with LD.” Journal of Learning Disabilities 37 (2): 105–118. doi:10.1177/00222194040370020201.

- Lansink, N. 2009. LOVS Taal voor kleuters groep 1 en 2 [Student Monitoring System Language for Preschoolers]. Arnhem, the Netherlands: Cito.

- Leathers, P. 2013. The Black Rabbit. Sommerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

- Lever, R., and M. Sénéchal. 2011. “Discussing Stories: On How a Dialogic Reading Intervention Improves Kindergartners’ Oral Narrative Construction.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 108 (1): 1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.07.002

- Lonigan, C. J., and G. J. Whitehurst. 1998. “Relative Efficacy of Parent and Teacher Involvement in a Shared-Reading Intervention for Preschool Children from Low-Income Backgrounds.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 13 (2): 263–290. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(99)80038-6

- Merchie, E., and H. Van Keer. 2016. “Mind Mapping as a Meta-Learning Strategy: Stimulating pre-Adolescents’ Text-Learning Strategies and Performance?” Contemporary Educational Psychology 46: 128–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.05.005

- Michaels, S., and C. B. Cazden. 1986. “Teacher/Child Collaboration as Oral Preparation for Literacy.” In The Acquisition of Literacy Ethnographic Perspectives, edited by B. B. Schieffelin, and P. Gilmore, 132–154. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Milburn, T. F., L. Girolametto, E. Weitzman, and J. Greenberg. 2014. “Enhancing Preschool Educators’ Ability to Facilitate Conversations During Shared Book Reading.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 14 (1): 105–140. doi: 10.1177/1468798413478261

- Mol, S. E., and A. G. Bus. 2011. “To Read or not to Read: A Meta-Analysis of Print Exposure from Infancy to Early Adulthood.” Psychological Bulletin 137 (2): 267–296. doi: 10.1037/a0021890

- Mol, S. E., A. G. Bus, and M. T. de Jong. 2009. “Interactive Book Reading in Early Education: A Tool to Stimulate Print Knowledge as Well as Oral Language.” Review of Educational Research 79 (2): 979–1007. doi: 10.3102/0034654309332561

- Mol, S. E., A. G. Bus, M. T. de Jong, and D. J. Smeets. 2008. “Added Value of Dialogic Parent–Child Book Readings: A Meta-Analysis.” Early Education and Development 19 (1): 7–26. doi: 10.1080/10409280701838603

- O’Neill, D. K., M. J. Pearce, and J. L. Pick. 2004. “Preschool Children’s Narratives and Performance on the Peabody Individualized Achievement Test – Revised: Evidence of a Relation between Early Narrative and Later Mathematical Ability.” First Language 24: 149–183. doi: 10.1177/0142723704043529

- Paivio, A. 1991. “Dual Coding Theory: Retrospect and Current Status.” Canadian Journal of Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie 45 (3): 255–287. doi: 10.1037/h0084295

- Rivers, W. M. 1987. Interactive Language Teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Schlichting, L. 2005. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III NL. Handleiding. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Harcourt Test Publishers.

- Sénéchal, M., and J. A. LeFevre. 2002. “Parental Involvement in the Development of Children’s Reading Skill: A Five-Year Longitudinal Study.” Child Development 73 (2): 445–460. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00417

- Slavin, R. E. 2008. “Perspectives on Evidence-Based Research in Education—What Works? Issues in Synthesizing Educational Program Evaluations.” Educational Researcher 37 (1): 5–14. doi: 10.3102/0013189X08314117

- Snow, C. 2002. Reading for Understanding: Toward an R&D Program in Reading Comprehension. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

- Snow, C. E., M. V. Porche, P. O. Tabors, and S. R. Harris. 2007. Is Literacy Enough? Pathways to Academic Success. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Sulzby, E. 1985. “Children’s Emergent Reading of Favorite Storybooks: A Developmental Study.” Reading Research Quarterly 20 (4): 458–481. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.20.4.4

- Sulzby, E., and W. H. Teale. 2003. “The Development of the Young Child and the Emergence of Literacy.” In Handbook of Research on Teaching the English Language Arts, edited by J. Flood, D. Lapp, J. Squire, and J. Jensen, 300–313. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Teunissen, J. M. F. B. G., and H. I. Hacquebord. 2002. Onderwijs met taalkwaliteit: kwaliteitskenmerken voor effectief taalonderwijs binnen onderwijskansenbeleid. [Quality Criteria for Effective Language Teaching]. ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands: KPC Groep.

- van der Veen, C., M. Dobber, and B. van Oers. 2016. “Implementing Dynamic Assessment of Vocabulary Development as a Trialogical Learning Process: A Practice of Teacher Support in Primary Education Schools.” Language Assessment Quarterly 13 (4): 329–340. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2016.1235577

- Van der Wilt, F., C. van Kruistum, C. van der Veen, and B. van Oers. 2016. “Gender Differences in the Relationship between Oral Communicative Competence and Peer Rejection: An Exploratory Study in Early Childhood Education.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (2): 807–817. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2015.1073507

- Van der Wilt, F., C. van der Veen, C. van Kruistum, and B. van Oers. 2018. “Why can’t I join? Peer Rejection in Early Childhood Education and the Role of Oral Communicative Competence.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 54: 247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.06.007

- Van Oers, B., and D. Duijkers. 2013. “Teaching in a Play-Based Curriculum: Theory, Practice and Evidence of Developmental Education for Young Children.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 45 (4): 511–534. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2011.637182

- Van Veen, K., R. Zwart, and J. Meirink. 2012. “What Makes Teacher Professional Development Effective? A Literature Review.” In Teacher Learning That Matters: International Perspectives, edited by M. Kooy, and K. van Veen, 23–41. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Vekiri, I. 2002. “What is the Value of Graphical Displays in Learning?” Educational Psychology Review 14 (3): 261–312. doi: 10.1023/A:1016064429161

- Verhallen, M. 2010. “Low-Income Immigrant Pupils Learning Vocabulary Through Digital Picture Storybooks.” Journal of Educational Psychology 102 (1): 54–61. doi: 10.1037/a0017133

- Verhoeven, L., and A. Vermeer. 2006. Verantwoording Taaltoets Alle Kinderen (TAK) [Justification Language Test for All Children]. Arnhem, the Netherlands: Centraal Instituut voor Toetsontwikkeling.

- Zucker, T., A. Ward, and L. Justice. 2009. “Print Referencing during Read-Alouds: A Technique for Increasing Emergent Readers’ Print Knowledge.” The Reading Teacher 63 (1): 62–72. doi: 10.1598/RT.63.1.6