ABSTRACT

School closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic have disrupted the education of 91% of students worldwide. As a critical process in supporting young children’s resilience, play is increasingly recognised as a valuable pedagogical strategy within a shifting educational landscape during the pandemic. This study reports on findings from a survey on play in early childhood education of 310 early childhood teachers during primary school closures in Ireland. Eighty-two per cent of teachers recommended play strategies to parents during remote teaching and home schooling and almost all teachers (99%) intended to use play as a pedagogical strategy upon school reopening. Teachers believed play was an especially important pedagogical tool in supporting young children’s social-emotional development, learning and transition back to school. Over a third highlighted uncertainty surrounding capacity to use play upon school reopening given COVID-19 regulations, emphasising the need for greater guidance to support teachers’ commitment to play-based pedagogical strategies.

Introduction

On March 12th 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO Citation2020a) declared a global pandemic as cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) surged throughout the world. This resulted in global measures to control the spread of the COVID-19 virus including social distancing, restriction of movements within and between countries and closure of schools. For many children across the globe their worlds were turned upside down as they were confined to their homes. At its peak on March 31st 2020, UNESCO (Citation2020a) reported school closures across 193 countries impacting a total of 1,598, 017, 253 learners worldwide.

There is an overwhelming body of research emerging as to the adverse impact of COVID-19 on world economies (Baldwin and di Mauro Citation2020; Ivanov Citation2020; Nicola et al. Citation2020), health systems (Li et al. Citation2020; Supady Citation2020; Webster Citation2020), and individual health and wellbeing (Lades et al. Citation2020; Staines et al. Citation2020; Torales et al. Citation2020). Less visible in the pandemic are children (Fore Citation2020; Sinha, Bennett, and Taylor-Robinson Citation2020). Although children do not appear to be at the forefront of this pandemic in terms of acquisition and transmission risk (Centre for Disease Control Citation2020; Gudbjartsson et al. Citation2020; Tagarro et al. Citation2020), it is important that the indirect impact of the virus is not underestimated: children have experienced significant disruptions in their daily routines across home and family life as well as early childhood education and care (Barlett, Griffin, and Thomson Citation2020; OECD Citation2020). We know from previous literature on children’s reactions to crises such as natural disasters and political violence that they may experience adverse effects for months or years and these effects may even be lifelong (Kar Citation2009; Le Brocque et al. Citation2017). This is particularly true for young children who may lack the cognitive and verbal capacity to process such monumental events (Durbin Citation2010).

Play and early childhood development and learning

Play has been described as ‘nature’s way of dealing with stress for children’ (Elkind Citation1981, 197). Many researchers highlight the centrality of play in managing emotions and promoting children’s resilience in the face of adversity (Capurso and Ragni Citation2016; Marcelo and Yates Citation2014; Russ Citation2007). This is especially true for those experiencing conflict and crises (Fearn and Howard Citation2012; Frost Citation2005) whereby, it provides a valuable escape during times of turmoil, offering a sense of normality and routine (UNICEF Citation2018). Play also allows children to process events in an accessible manner, acting as a protective buffer during times of distress (Berson and Baggerly Citation2009; Chatterjee Citation2018). Many researchers also highlight the role of play in facilitating the expression of emotions within a safe context (Landreth and Homeyer Citation1998; Rao and Gibson Citation2019; Rao Citation2020). In this sense, play provides a natural medium that allows children to express emotions, anxieties and fears that they may not be able to verbally articulate (Anderson-McNamee and Bailey Citation2010; Axline Citation1974).

Play may therefore have a pivotal role in supporting children’s development and learning during the global COVID-19 crisis. In a recent interview, Jack Shonkoff at the Centre for the Developing Child (Citation2020) identified play as the most important way in which we can support children during this pandemic, reduce stress and build resilience. Similarly, the role of play in helping children make sense of the unprecedented changes that have occurred in their lives, during the pandemic, and process the associated trauma has been highlighted by David Neale at the Play in Education, Development and Learning Centre (Neale Citation2020). Efforts have also been made at a policy level to advocate for play during the pandemic in the form of national initiatives such as Let’s Play Ireland (DCYA Citation2020) as well as international campaigns (Play Australia Citation2020; Play Scotland Citation2020; WHO Citation2020b).

Play in early childhood education in the context of COVID-19

There are significant concerns regarding the loss of learning for children worldwide as a result of school closures (Bao et al. Citation2020; Dorn et al. Citation2020; OECD Citation2020). School closures are also likely to impact young children’s social and emotional development (Buheji et al. Citation2020; Giannini, Jenkins, and Saavedra Citation2020; UNESCO Citation2020b). Schools are very much at the frontline in offering emotional support to children during times of crisis (Mutch Citation2015; Skovdal and Campbell Citation2015; Peek et al. Citation2018). Emerging research highlights increased levels of social isolation, loneliness and anxiety among children during the pandemic (Loades et al. Citation2020; Orgiles et al. Citation2020; UNESCO Citation2020c) as well as a potentially detrimental impact of the pandemic on the social and emotional wellbeing of children with additional needs (Colizzi et al. Citation2020; Eshraghi et al. Citation2020; Patel Citation2020) who may be more sensitive to its adverse effects (Aishworiya and Kang Citation2020; den Houting Citation2020; Zhang et al. Citation2020). As a result, schools will likely play a fundamental role in supporting all children as countries attempt to tackle the repercussions of this pandemic on children (UNESCO Citation2020d).

An integral component of early childhood education (ECE) curricula across many countries including New Zealand (Te Whariki), United Kingdom (Early Years Foundation Stage/Enriched Curriculum), Italy (Reggio Emilia Approach), United States of America (e.g. High/Scope Curriculum) and Ireland (Aistear), play has been recognised as critical in supporting children’s development, wellbeing and learning (Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff Citation2003; Parker and Thomsen Citation2019; Whitebread et al. Citation2012). Some limited studies have begun to focus on planning children’s return to school post COVID-19, yet much of the literature has centred on the impact of transmission and medical implications (Ludvigsson Citation2020; Melnick and Darling-Hammond Citation2020; Viner et al. Citation2020). Whilst it is essential to discuss such aspects as we plan to return to schools, plans also need to be put in place around pedagogical strategies that will support children’s social and emotional development and learning thereby, potentially mitigating the detrimental effects of lockdown and school closures (Graber et al. Citation2020; Masonbrink and Hurley CitationForthcoming). Indeed, during such turmoil it is likely that ‘we need play most of all’ in teaching and caring for young children (Neale Citation2020, 2).

The current study

In light of the increasing recognition of play in ECE and of the potential importance of play in supporting young children’s resilience during the pandemic, this study sought to examine the perspectives of early childhood teachers in Ireland on the role of play in ECE during the COVID-19 crisis. The study aimed to contribute early evidence in an emerging field of research on play in the pandemic by asking teachers about their views of play as a pedagogical support during the COVID-19 crisis. Teachers were asked if they advised parents to use play during school closures and whether play would have a significant role in supporting children’s transition back to the classroom. Delving deeper into the potential role of play in early childhood classrooms, teachers were then asked the extent to which play would be used as a pedagogical strategy when schools reopened, and were invited to expand upon their views through an open-ended question. Data collection was undertaken in June and July 2020, during the very early stages of the pandemic and at the end of a phase of school closures (and prior to planned school re-openings in September 2020).

Materials and methods

Participants

Primary school teachers across the Republic of Ireland (ROI) with experience (past or present) of teaching in ECE classrooms (children aged 4–7 years in primary education) were invited to participate in a survey on play in ECE. The survey was hosted on the online platform, Qualtrics, and was accessed by respondents via a shared link on social media. School principals, whose contact details were publicly available, were also emailed a link to the survey and invited to circulate with staff. Snowball sampling was used to reach as many primary school teachers as possible over a two-week period at the end of the school year (June 26th to July 10th 2020). At the time of the survey, teachers were approaching the end of over three months of school closures during which they had been engaging in remote teaching.

Respondent characteristics were captured as part of the questionnaire (see for sample characteristics) and were used to provide context for thematic reporting of teachers’ views of play in ECE during the pandemic. Three hundred and ten primary school early childhood teachers completed the survey. The overwhelming majority of respondents were women (96.8%). This disproportionate response in terms of gender has been found in similar studies of ECE within the ROI (Gray and Ryan Citation2016) and may also reflect the gender disparity within primary school teaching in the ROI where only 15 percent of teachers are men (Central Statistics Office Citation2020). The sample was also highly educated, with over half of respondents (52.6%) having completed a Master’s degree.

Table 1. Sample demographic and professional characteristics.

Materials

The data reported here were collected as part of a larger 42-item survey study of play in ECE of which 39 items were closed-ended questions or statements to which respondents indicated level of agreement. Four questions on the survey (three of which were closed-ended Likert scale questions) were included as a rapid response to the developing pandemic crisis and were designed to capture early childhood teachers’ views on play in the pandemic. These questions were constructed following in-depth examination of the research literature (Graber et al. Citation2020; Neale Citation2020; Shonkoff Citation2020; UNESCO Citation2020d) to ensure content validity of the questions (i.e. that each question captured an important aspect of how teachers’ viewed play as a pedagogical support during the pandemic). Internal consistency for the three closed-ended questions was moderate (α = .66). As questions addressed separate, though related, aspects of play in education during the pandemic, lower internal consistency was not unexpected. A pilot of the survey was conducted using a convenience sample of five primary school teachers with past or present teaching experience within ECE at the time of data collection. Feedback from this sample of early childhood teachers was given verbally through discussion and through written comments, and contributed to establishing face validity of survey items. The questionnaire was revised based on pilot feedback, which included shortening the survey to reduce length of time for completion and clarifying procedures for teachers currently on leave.

Survey questions on play in the pandemic

Teachers were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the following statements: (1) ‘I am currently encouraging parents to engage in play with children as part of school communication during COVID-19 restrictions’; and (2) ‘Play will have a significant role in supporting children’s transition back to school post COVID-19 restrictions’. Possible responses for each statement ranged on a Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Teachers were also asked to indicate the degree of importance they attributed to play as a pedagogical tool within their classroom upon school reopening, with responses ranging from ‘not important’ and ‘somewhat important’ to ‘important’. Crucially, teachers were invited to elaborate on their response to this statement through an open-ended survey item. Three hundred and one early childhood teachers elaborated on their views of play as a pedagogical support in anticipation of schools reopening in September 2020. Thematic analysis of the 301 responses to the open-ended question constitutes the main focus on this paper.

Ethical approval

The study was subject to ethical review by the Research Ethics Committee at the authors’ institution. Ethical approval was received from the Research Ethics Committee on June 24th 2020.

Analysis

The full sample of 310 early childhood teachers responded to the three closed-ended questions on play in the pandemic. Descriptive statistics regarding the extent to which teachers’ agreed with each of these statements about play was undertaken using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 25) software. Teachers’ responses to the open-ended question on the importance of play as a pedagogical support in anticipation of the reopening of schools were analysed using thematic coding based on Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) framework. An inductive approach to thematic analysis was employed based on experiential orientation to the data as outlined by Clark and Braun (Citation2015). This approach involved: (1) transcribing all data from the open-ended question, (2) re-reading transcripts to gain familiarity with the dataset as a whole, (3) identifying codes, (4) generating emerging themes, (5) organising and reviewing themes using thematic mapping, and (6) naming and defining themes and supporting with powerful examples from the dataset. The second author screened data and subsequently read the first author’s selected codes and themes to reduce the risk of bias and ensure consistency.

Results

Descriptive analysis indicated strong support for play as a pedagogical strategy during school closures and in anticipation of the reopening of schools. The vast majority of teachers (81.6%) either agreed (42.6%) or strongly agreed (39.0%) with the statement that they had encouraged parents to play with children during school closures. An even greater proportion of teachers (86.7%) either agreed (33.2%) or strongly agreed (53.5%) with the statement that play will have a significant role in supporting children’s return to school. Almost all teachers (98.7%) viewed play as an important pedagogical tool within their classroom upon school reopening, with 80.3% indicating it would be a very important pedagogical strategy.

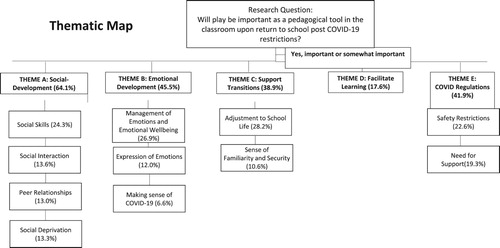

Thematic analysis of the 301 responses to the open-ended question on the importance of play as a pedagogical strategy upon the reopening of schools was conducted to gain a deeper understanding of teachers’ views of play in the pandemic. Responses were organised, coded and subsequently assigned into themes, as indicated in .

Figure 1. Thematic map: the importance of play as a pedagogical tool in the early childhood classroom.

The themes identified in the 301 returned responses were: (1) play as a support for children’s social development; (2) play as a support for children’s emotional development; (3) play as facilitating children’s learning; (4) play as a support for children’s transition back to school; and (5) concerns around implementing play in light of COVID-19 regulations.

Play for children’s social development within early childhood education

Over half (64.1%) of respondents indicated that play would have an important role in their classroom practice upon returning to school specifically in relation to supporting children’s social development. Many respondents referenced particular aspects of social development including improvement of social and communication skills (24.3%) such as turn-taking, sharing and conversation skills whereby play will provide a vital opportunity ‘to communicate with others again’. Respondents also highlighted the role of play in fostering peer relationships (13.0%), providing children the opportunity to ‘reconnect with the other children’ ‘rebuild social bonds’ and ‘re-establish relationships’. Social interaction skills (13.6%) were also referenced as a key aspect of social development and many teachers felt play offered the ‘most natural way for children to do this’. Others referenced the need for interaction:

The difference is that children have had a traumatic few months, they NEED to play with each other again. They need that interaction, for social and emotional wellbeing. (Female Mainstream Class Teacher with 5-10 years’ teaching experience; Rural Mainstream school)

| (2) | Play for children’s emotional development within early childhood education | ||||

Nearly half (45.5%) of respondents indicated that play would have an important role in their classroom practice upon returning to school in supporting children’s emotional development. Respondents made reference to specific aspects of emotional development including management of emotions and emotional wellbeing (26.9%). Many highlighted the role of play as central to supporting the development of resilience in ‘response to trauma’. Much of this centred on increased levels of fear and anxiety as a result of lockdown whereby play ‘will be central to easing and calming fears’ and allow children to ‘process their trauma and anxiety’ as reflected in the following quotations:

Children will need the space and time to work through their anxieties and fears and to share with others. Play can provide safe non-threatening ways to express these emotions. (Female Special Education Teacher with over 15 years’ teaching experience; Urban Mainstream school)

Since we do not know what effect the lockdown has had on children it becomes even more important to use play as a means of developing their social and emotional health. (Female Special Education Teacher with 10-15 years’ teaching experience; Urban Mainstream school)

Not only did respondents highlight the role of play in supporting children’s management of emotions but also regarding the expression of emotions (12.0%) given that play allows children to ‘express themselves most naturally’. Some respondents made specific reference to young children who ‘will have found it difficult to express what they are feeling during lockdown’. A sizeable minority of respondents (6.6%) also mentioned the value of play in helping children make sense of the pandemic and traumatic events of lockdown, with one respondent specifically referencing the role of play in supporting those within marginalised communities (in this instance, pupils from a ‘DEIS school’, part of the ‘Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools’ programme in Ireland):

As we are a DEIS school I feel that some of our children will have struggled greatly during the pandemic and therefore need to engage with play to help make sense of some of these struggles. (Female Mainstream Class Teacher with over 15 years’ teaching experience; Urban DEIS school)

| (3) | Play to support transition back to school | ||||

Over a third (38.9%) of respondents indicated that play would have an important role in supporting children’s transition back to school specifically in supporting their adjustment to school life:

The rise of online learning and impersonal engagement will have altered children's perspectives on school. I hope that by incorporating play into their daily school lives they can transition back to a new normal in a gradual and healthy manner. (Female Mainstream Class Teacher with 10-15 years’ teaching experience; Rural Mainstream school)

Students with severe profound learning difficulties will re-familiarise themselves with staff and school environment, use of equipment, table top work etc. through play where possible. (Female Special School Teacher with 10-15 years’ teaching experience; Urban Special school)

I feel it will pose as a safe medium for them to transition back into school life and routine. Play is what they do best. It will soothe and comfort them and settle them back in the best way. (Female Mainstream Class Teacher with 5-10 years’ teaching experience; Rural Mainstream school)

| (4) | Play to facilitate learning within early childhood education | ||||

Although teachers primarily discussed the role of play in facilitating social and emotional development and supporting transitions, respondents (17.6%) also acknowledged the role of play in facilitating children’s learning upon returning to school and enabling the achievement of curricular goals and learning objectives:

Play is so important in infants. I integrate it into all aspects of the curriculum. I need play to be able to teach. If children are not allowed to play, I will not be able to effectively teach the class in a way in which they learn best-by doing and experimenting. (Female Mainstream Class Teacher with 10-15 years’ teaching experience; Rural Mainstream school setting)

| (5) | Concerns around play within early childhood education and COVID-19 regulations | ||||

There were, however, several concerns regarding the role of play as a pedagogical strategy upon children’s return to school. Forty-two percent of teachers expressed concerns about using play as a pedagogical tool upon return to school given COVID regulations. This centred on specific aspects such as implementation and reinforcement of safety protocols (22.6%) such as social distancing, sharing of toys and resources as well as hygiene procedures. Teachers demonstrated a sense of uncertainty as to what capacity they will be able to incorporate play into their classroom practice upon school reopening whereby, they had ‘no idea what our classrooms will look like and how we will facilitate play’. Others described it as ‘a guessing game’ and were concerned they may have to revert back to traditional methods such as ‘chalk and talk’.

I’m worried that we won’t be allowed to play with current restrictions and I don’t have the time to be washing all the toys daily. I’m worried I can’t facilitate play as I have in the past because of restrictions. (Female Mainstream Class Teacher with 10-15 years’ teaching experience; Rural Mainstream school setting)

I am unsure as to how play will be carried out when pupils return to school in September. Even if infants aren't required to socially distance, will the teacher be able to get ‘stuck-in’ with the children and to what extent can resources for play be shared? (Female Mainstream Class Teacher with over 15 years’ teaching experience; Rural Mainstream school setting)

The need for clarity and guidance in response to such uncertainty in order to support planning for play was raised. Several teachers called for support whilst some were concerned as to whether they would be able to integrate play at all ‘as guidance is very unclear from DES’ and it ‘may not be recommended by the government’. Many, as a result, called for guidance and reassurance from the Department of Education.

The fear is that the use of play will be impacted depending on government guidelines into the sharing of resources within schools. It’s uncharted territory for us all. And time will tell. (Female Special Education Teacher with over 15 years’ teaching experience; Urban Mainstream school setting)

Discussion

This study addressed an important aspect of early childhood classrooms and teaching in the emerging research on the education of young children in the global COVID-19 crisis, namely attitudes to play and intention to use play pedagogies to support children during the crisis. In surveying a large sample of ECE teachers in Ireland, we identified strong commitment to play in supporting young children’s learning and development during initial school closures and as a pedagogical strategy when schools reopen.

The vast majority of teachers encouraged parents to play with their children during lockdown. This is in keeping with findings from a large study in Ireland on the experiences of primary school leaders during initial school closures (Burke and Majella Dempsey Citation2020) in which the majority of leaders (68.8%) reported the widespread use of play as one of the key methodologies to engage children in online learning during the pandemic. An emphasis on play among parents in Ireland was also reported by Egan and her colleagues (Egan, Chloe Beatty, and Hoyne Citation2020) who found that up to 78% of over 500 parents, of children aged one to ten years, reported an increase in time spent engaging in outdoor play, play with games and toys as well as on-screen activities in comparison to before the pandemic. Cross-cultural findings reported by Samuelsson, Wagner, and Ødegaard (Citation2020) across three ECE centers in Sweden, Norway and the US indicate the incorporation of dramatic play activities as part of remote schooling as well as the provision of activities and resources for parents. However, limited data is currently available on play in the context of educational plans for supporting young children during school closures and when schools reopen.

Eighty-seven per cent of teachers in our study indicated that play would have a significant role in teachers’ approaches to supporting children’s transition to school upon reopening. This is positive in light of the strong international evidence regarding the role of play in supporting children in the aftermath of traumatic events (Fearn and Howard Citation2012; Frost Citation2005; UNICEF Citation2018). Almost all ECE teachers highlighted the importance of play as a pedagogical tool within their classroom practice upon school reopening post COVID-19 restrictions. While several teachers valued the role of play in supporting children’s learning, this was superseded by the importance teachers placed on play as a support for children’s social and emotional wellbeing as well as their transition back to school.

These findings suggest astute understanding among teachers of the significance of focusing on children’s social and emotional development following months of unprecedented change, an understanding reflected in international policy recommendations for supporting children through this crisis (Giannini, Jenkins, and Saavedra Citation2020; UNESCO Citation2020d). These results also appear to align with those emerging within the UK. For example, in a survey of 1,653 primary teachers prior to school reopening, Moss and colleagues (2020) found that most teachers planned to prioritise the psychological wellbeing of pupils. This suggests that ECE teachers are moving beyond play for learning within traditional curricular models and demonstrate widespread confidence and belief in its potential as a valuable tool to support children’s social and emotional wellbeing following this worldwide crisis. Such beliefs strongly reflect best practice recommendations throughout the literature (Capurso and Ragni Citation2016; Marcelo and Yates Citation2014; Russ Citation2007; UNICEF Citation2018). However, only a small number of teachers (three in total) made reference to the role of play in supporting the wellbeing of children with additional needs. This was surprising given that seventy-two respondents were working within special education, and that emerging research highlights the need to support children with additional needs during the pandemic who may be more sensitive to its adverse effects (Aishworiya and Kang Citation2020; den Houting Citation2020; Zhang et al. Citation2020). Our findings support other studies which emphasise a need for rigorous research on play as an educational strategy for children with additional needs (Lifter et al. Citation2011; Macintyre Citation2010) and highlight a need for research on play opportunities in the education of young children with additional needs during the pandemic.

The high value which teachers placed on play as a pedagogical strategy to support children’s return to school was accompanied, however, by a degree of uncertainty among 42 per cent of teachers in this study. Several teachers expressed reservations that there would be limited capacity for play in the classroom due to COVID-19 regulations including safety protocols such as social distancing, sharing of materials and hygiene procedures with some voicing concern over the impact of such measures on their capacity to ‘return to play as normal’ and ‘the way it was taking place in the classroom’ pre-pandemic restrictions. Such concerns were further compounded by a reported lack of support and guidance which may further impact teachers’ capacity to incorporate play into classroom practice. This sense of apprehension is reflected throughout national and international research literature, in which teachers have expressed significant concerns regarding a lack of clarity and guidance in planning their return to the classroom following school closures (Dempsey and Burke Citation2020; Eivers, Worth, and Ghosh Citation2020; Samuelsson, Wagner, and Ødegaard Citation2020).

This study provides evidence of a shared vision of prioritising young children’s wellbeing and smooth transition back to school in light of severe educational disruption. While it is clear that schools have significant potential to help children following traumatic experiences (Mutch Citation2015; Skovdal and Campbell Citation2015; Peek et al. Citation2018), it is important that they are supported in this process (Global Education Cluster Citation2020; Le Brocque et al. Citation2017) through clear guidance on the implementation of effective educational strategies that support children’s wellbeing and learning while taking on board health regulations and guidelines in the classroom (Lewin Citation2020; UNESCO Citation2020e). This study contributes important evidence from ECE teachers about the ways in which play is intended to be used as a strategy to support children, and the supports which teachers, in turn, require to ensure these strategies are implementable.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the questions on the use of play during the COVID-19 crisis were included as part of a wider survey designed to capture teachers’ views on play for inclusive ECE. Thus, only four items of the wider survey specifically addressed ECE teaching with regard to play during the pandemic. However, the inclusion of an open-ended question on the importance of play as a pedagogical strategy upon return to classroom teaching allowed for the collection of rich data from 301 participating teachers which have been reported here. Secondly, while this is a relatively large survey of early childhood teachers in Ireland, male teachers are under-represented in the survey sample. Finally, as respondents self-selected into the study, it is also likely that teachers who chose to complete the survey were already very interested in play in ECE. Thus, the responses to the questions on play in the pandemic reflect the views of a predominantly female sample of teachers who may be strongly invested in play-based pedagogies. Future surveys in Ireland and internationally should adopt a purposive and stratified sampling approach to ensure views are representative of both male and female teachers at all stages of their career.

To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the only study to capture ECE teachers’ views on the potential of play to support teaching and learning during and after school closures due to the COVID-19 crisis. In doing so, the findings highlight an important aspect of policy for early childhood education in primary schools during the pandemic, and especially underline the need to provide clear guidance on play in ECE classrooms in the context of health and safety guidelines due to COVID-19. The findings also emphasise the impending urgency for policy makers across the globe to ‘plan for play’ in the reopening of ECE classrooms to ensure that young children are not hidden victims of this pandemic and receive the pedagogical supports they are likely to need following extensive disruption to education.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the teachers who participated in this study and who were so generous of their time in providing insight into the role of play as part of their schooling during the pandemic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aishworiya, Ramkumar, and Ying Qi Kang. 2020. “Including Children with Developmental Disabilities in the Equation During This COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–4. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04670-6.

- Anderson-McNamee, Jona K., and Sandra J. Bailey. 2010. “The Importance of Play in Early Childhood Development.” Montana State University Extention, 1–4. http://lanefacs.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/65563699/Importance%20of%20Play.pdf.

- Axline, Virginia Mae. 1974. Play Therapy. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Baldwin, Richard, and Beatrice W. di Mauro. 2020. Economies in the Time of COVID-19. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://cepr.org/sites/default/files/news/COVID-19.pdf.

- Bao, Xue, Hang Qu, Ruixiong Zhang, and Tiffany P. Hogan. 2020. “Literacy Loss in Kindergarten Children During COVID-19 School Closures.” SocArXiv. May 13. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/nbv79.

- Barlett, J. D., Jessica Griffin, and Dana Thomson. 2020. “Resources for Supporting Children’s Emotional Well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/resources-for-supporting-childrens-emotional-well-being-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.

- Berson, Ilene R., and Jennifer Baggerly. 2009. “Building Resilience to Trauma: Creating a Safe and Supportive Early Childhood Classroom.” Childhood Education 85 (6): 375–379. doi:10.1080/00094056.2009.10521404.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Buheji, Mohamed, Ashwaq Hassani, Ahmed Ebrahim, Katiane da Costa Cunha, Haitham Jahrami, Mohamed Baloshi, and Suad Hubail. 2020. “Children and Coping During COVID-19: A Scoping Review of Bio-Psycho-Social Factors.” International Journal of Applied Psychology 10 (1): 8–15. doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20201001.02.

- Burke, Jolanta, and M. Majella Dempsey. 2020. COVID-19 Practice in Primary Schools in Ireland Report. Maynooth: Maynooth University.

- Capurso, Michele, and Benedetta Ragni. 2016. “Bridge Over Troubled Water: Perspective Connections Between Coping and Play in Children.” Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1953. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01953.

- Central Statistics Office. 2020. Teacher Statistics. Cork: CSO. https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Statistics/teacher-statistics/.

- Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Children. April 10th. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6914e4.htm.

- Chatterjee, Sudeshna. 2018. “Children's Coping, Adaptation and Resilience Through Play in Situations of Crisis.” Children, Youth and Environments 28 (2): 119–145. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.28.2.0119.

- Clark, Virginia, and And Victoria Braun. 2015. “Thematic Analysis.” In Qualitative Psychological Research: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, edited by John Smith, 222–248. London: Sage.

- Colizzi, Marco, Elena Sironi, Federico Antonini, Marco Luigi Ciceri, Chiara Bovo, and Leonardo Zoccante. 2020. “Psychosocial and Behavioral Impact of COVID-19 in Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Online Parent Survey.” Brain Sciences 10 (6): 341.

- Dempsey, Majella, and Jolanta Burke. 2020. COVID-19 Practice in Primary Schools in Ireland Report: A Two-Month Follow-Up. Maynooth: Maynooth University.

- den Houting, Jac. 2020. “Stepping out of Isolation: Autistic People and COVID-19.” Autism in Adulthood 2 (2): 103–105.

- Department of Children and Youth Affairs. 2020. Let’s Play Ireland. April 22nd. https://www.gov.ie/en/campaigns/lets-play-ireland/.

- Dorn, Emma, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg. 2020. COVID-19 and Student Learning in the United States: The Hurt Could Last a Lifetime. New York: McKinsey & Company. https://fresnostate.edu/kremen/about/centers-projects/weltycenter/documents/COVID-19-and-student-learning-in-the-United-States-FINAL.pdf.

- Durbin, C. Emily. 2010. “Validity of Young Children's Self-Reports of Their Emotion in Response to Structured Laboratory Tasks.” Emotion 10 (4): 519–535. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0019008.

- Egan, Suzanne, M. Chloe Beatty, and Clara Hoyne. 2020. Play-Impact of COVID-19 Restrictions on Young Children’s Play Learning and Development: Key findings from the Play and Learning in the Early Years (PLEY) Survey. July 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342701227_Play_-_Impact_of_COVID19_Restrictions_on_Young_Children%27s_Play_Learning_and_Development_Key_Findings_from_the_Play_and_Learning_in_the_Early_Years_PLEY_Survey_-_Play.

- Eivers, Eemer, Jack Worth, and Anusha Ghosh. 2020. Home Learning during COVID-19: Findings from the Understanding Society Longitudinal Study. Slough: National Foundation for Educational Research. https://www.nfer.ac.uk/home-learning-during-covid-19-findings-from-the-understanding-society-longitudinal-study/.

- Elkind, David. 1981. The Hurried Child. Growing up Too Fast Too Soon. Boston, MA: De Capo.

- Eshraghi, Adrien A., Crystal Li, Michael Alessandri, Daniel S. Messinger, Rebecca S. Eshraghi, Rahul Mittal, and F. Daniel Armstrong. 2020. “COVID-19: Overcoming the Challenges Faced by Individuals with Autism and Their Families.” The Lancet Psychiatry 7 (6): 481–483.

- Fearn, Maggie, and Justine Howard. 2012. “Play as a Resource for Children Facing Adversity: An Exploration of Indicative Case Studies.” Children & Society 26 (6): 456–468. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00357.x.

- Fore, H. 2020. Don’t Let Children be the Hidden Victims of COVID-19 Pandemic. April 9th. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/dont-let-children-be-hidden-victims-covid-19-pandemic.

- Frost, Joe L. 2005. “Lessons from Disasters: Play, Work, and the Creative Arts.” Childhood Education 82 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1080/00094056.2005.10521332.

- Giannini, Stefania, Robert Jenkins, and Jaime Saavedra. 2020. “Reopening schools: When, where and how?” UNESCO, May 13th. https://en.unesco.org/news/reopening-schools-when-where-and-how.

- Global Education Cluster. 2020. “Safe Back to School: A Practitioner’s Guide.” Global Education Cluster. May 14th. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/safe-back-school-practitioners-guide.

- Graber, Kelsey, Elizabeth M. Byrne, Emily J. Goodacre, Natalie Kirby, Krishna Kulkarni, Christine O’Farrelly, and Paul G. Ramchandani. 2020. “A Rapid Review of the Impact of Quarantine and Restricted Environments on Children’s Play and Health Outcomes.” PsyArXiv. May 26. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/p6qxt.

- Gray, Colette, and Anna Ryan. 2016. “Aistear vis-à-vis the Primary Curriculum: The Experiences of Early Years Teachers in Ireland.” International Journal of Early Years Education 24 (2): 188–205. doi:10.1080/09669760.2016.1155973.

- Gudbjartsson, Daniel F., Agnar Helgason, Hakon Jonsson, Olafur T. Magnusson, Pall Melsted, Gudmundur L. Norddahl, Jona Saemundsdottir, et al. 2020. “Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic Population.” New England Journal of Medicine 382: 2302–2315. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2006100.

- Hirsh-Pasek, Kathy, and Roberta Golinkoff. 2003. Einstein Never Used Flashcards: How our Children Really Learn and Why They Need to Play More and Memorize Less. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press.

- Ivanov, Dmitry. 2020. “Predicting the Impacts of Epidemic Outbreaks on Global Supply Chains: A Simulation-Based Analysis on the Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) Case.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 136: 101922. doi:10.1016/j.tre.2020.101922.

- Kar, Nilamadhab. 2009. “Psychological Impact of Disasters on Children: Review of Assessment and Interventions.” World Journal of Pediatrics 5 (1): 5–11. doi:10.1007/s12519-009-0001-x.

- Lades, L. K., Kate Laffan, Michael Daly, and Liam Delaney. 2020. “Daily Emotional Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” British Journal of Health Psychology, doi:10.1111/bjhp.12450.

- Landreth, Gary L., and Linda Homeyer. 1998. “Play as the Language of Children’s Feelings.” In Play from Birth to Twelve and Beyond: Contexts, Perspectives and Meanings, edited by D. P. Fromberg and D. Bergen, 193–198. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Le Brocque, Robyne, Alexandra De Young, Gillian Montague, Steven Pocock, Sonja March, Nikki Triggell, Claire Rabaa, and Justin Kenardy. 2017. “Schools and Natural Disaster Recovery: The Unique and Vital Role That Teachers and Education Professionals Play in Ensuring the Mental Health of Students Following Natural Disasters.” Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools 27 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1017/jgc.2016.17.

- Lewin, Keith M. 2020. “Contingent Reflections on Coronavirus and Priorities for Educational Planning and Development.” Prospects, 1–8. doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09480-3.

- Li, Wen, Yuan Yang, Zi-Han Liu, Yan-Jie Zhao, Qinge Zhang, Ling Zhang, Teris Cheung, and Yu-Tao Xiang. 2020. “Progression of Mental Health Services During the COVID-19 Outbreak in China.” International Journal of Biological Sciences 16 (10): 1732. doi:10.7150%2Fijbs.45120.

- Lifter, Karin, Suzanne Foster-Sanda, Caley Arzamarski, Jacquelyn Briesch, and Ellen McClure. 2011. “Overview of Play: Its Uses and Importance in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education.” Infants & Young Children 24 (3): 225–245.

- Loades, Maria Elizabeth, Eleanor Chatburn, Nina Higson-Sweeney, Shirley Reynolds, Roz Shafran, Amberly Brigden, Catherine Linney, Megan Niamh McManus, Catherine Borwick, and Esther Crawley. 2020. “Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.jbs.elsevierhealth.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/jaac/aip.pdf.

- Ludvigsson, Jonas F. 2020. “Children are Unlikely to be the Main Drivers of the COVID-19 Pandemic–a Systematic Review.” Acta Paediatrica 109: 1525–1530. doi:10.1111/apa.15371.

- Macintyre, Christine. 2010. Play for Children with Special Needs: Supporting Children with Learning Differences, 3-9. Oxon: Routledge.

- Marcelo, Ana K., and Tuppett M. Yates. 2014. “Prospective Relations among Preschoolers’ Play, Coping, and Adjustment as Moderated by Stressful Events.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 35 (3): 223–233. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2014.01.001.

- Masonbrink, Abbey R, and Emily Hurley. Forthcoming. “Advocating for Children During the COVID-19 School Closures.” Paediatrics, doi:10.1542/peds.2020-1440.

- Melnick, Hannah, and Linda Darling-Hammond. 2020. Reopening Schools in the Context of COVID-19: Health and Safety Guidelines from Other Countries. Washington, DC: Learning Policy Institute. http://www.nordcountryschool.org/uploads/5/2/3/3/5233925/1reopening_schools_covid-19_brief.pdf.

- Mutch, Carol. 2015. “The Role of Schools in Disaster Settings: Learning from the 2010–2011 New Zealand Earthquakes.” International Journal of Educational Development 41: 283–291. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.06.008.

- Neale, David. 2020. W: Why we all need Play in a Crisis. Cambridge University: PEDAL. https://www.pedalhub.org.uk/play-piece/w-why-we-all-need-play-crisis.

- Nicola, Maria, Zaid Alsafi, Catrin Sohrabi, Ahmed Kerwan, Ahmed Al-Jabir, Christos Iosifidis, Maliha Agha, and Riaz Agha. 2020. “The Socio-Economic Implications of the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19): A Review.” International Journal of Surgery (London, England) 78: 185–193. doi:10.1016%2Fj.ijsu.2020.04.018.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2020. Combatting COVID-19 Effect on Children. Paris: OECD, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/combatting-covid-19-s-effect-on-children-2e1f3b2f/.

- Orgiles, Mireia, Alexandra Morales, Elisa Delveccio, Claudia Mazzeschi, and P. Espada Jose. 2020. “Immediate Psychological Effects of COVID-19 Quarantine in Youth from Italy and Spain.” PsyArXiv, April 24th. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5bpfz.

- Parker, Rachel, and Bo Stjerne Thomsen. 2019. Learning through Play at School. A Study of Playful Integrated Pedagogies that foster Children’s Holistic Skills Development in the Primary School Classroom. White Paper. Billund: The Lego Foundation. https://www.legofoundation.com/media/1740/learning-through-play-school.pdf.

- Patel, Khushboo. 2020. “Mental Health Implications of COVID-19 on Children with Disabilities.” Asian Journal of Psychiatry 54: 102273. doi:10.1016%2Fj.ajp.2020.102273.

- Peek, Lori, David M. Abramson, Robin S. Cox, Alice Fothergill, and Jennifer Tobin. 2018. “Children and Disasters.” In Handbook of Disaster Research, edited by H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, and J.E. Trainor, 243–262. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Play Australia. 2020. “Let’s Play Today.” Accessed July 13th 2020 https://www.playaustralia.org.au/play-today-covid19.

- Play Scotland. 2020. “#101WaystoPlayCampaign.” Accessed July 13th 2020 https://www.playscotland.org/101waystoplay-campaign/.

- Rao, Zhen. 2020. P: Pretend Play: Promoting Positive Emotions in Children. Cambridge University: PEDAL. https://www.pedalhub.org.uk/play-piece/p-pretend-play-promoting-positive-emotions-children.

- Rao, Zhao, and Jenny Gibson. 2019. “The Role of Pretend Play in Supporting Young Children’s Emotional Development.” In The SAGE Handbook of Developmental Psychology and Early Childhood Education, edited by D. Whitebread et al., 63–79. London: Sage.

- Russ, Sandra W. 2007. “Pretend Play: A Resource for Children who are Coping with Stress and Managing Anxiety.” NYS Psychologist XIX (5): 13–17.

- Samuelsson, Ingrid Pramling, Judith T. Wagner, and Elin Eriksen Ødegaard. 2020. “The Coronavirus Pandemic and Lessons Learned in Preschools in Norway, Sweden and the United States: OMEP Policy Forum.” International Journal of Early Childhood, 1–16. doi:10.1007/s13158-020-00267-3.

- Shonkoff, Jack P. 2020. “The Brain Architects Podcast.” Discussion 1. COVID-19 Special Edition: A Different World. Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/the-brain-architects-podcast-covid-19-special-edition-a-different-world/.

- Sinha, Ian, Davara Bennett, and David C. Taylor-Robinson. 2020. “Children are Being Sidelined by Covid-19.” British Medical Journal 369), doi:10.1136/bmj.m2061.

- Skovdal, Morten, and Catherine Campbell. 2015. “Beyond Education: What Role Can Schools Play in the Support and Protection of Children in Extreme Settings?” International Journal of Educational Development 41: 175–183. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.02.005.

- Staines, Anthony, René Amalberti, Donald M. Berwick, Jeffrey Braithwaite, Peter Lachman, and Charles A. Vincent. 2020. “COVID-19: Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Skills to Deploy During the Surge.” International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1–3. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzaa050.

- Supady, Alexander. 2020. “Consequences of the Coronavirus Pandemic for Global Health Research and Practice.” Journal of Global Health 10 (1), doi:10.7189%2Fjogh.10.010366.

- Tagarro, Alfredo, Cristina Epalza, Mar Santos, Francisco José Sanz-Santaeufemia, Enrique Otheo, Cinta Moraleda, and Cristina Calvo. 2020. “Screening and Severity of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Children in Madrid, Spain.” JAMA Paediatrics, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2764394.

- Torales, Julio, Marcelo O’Higgins, João Mauricio Castaldelli-Maia, and Antonio Ventriglio. 2020. “The Outbreak of COVID-19 Coronavirus and its Impact on Global Mental Health.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 66 (4): 317–320. doi:10.1177%2F0020764020915212.

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation). 2020a. COVID-19 Impact on Education. Paris: UNESCO https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse.

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation). 2020b. Nurturing the Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Children and Young People During Crises. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373271.

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation). 2020c. School Reopening: Ensuring Learning Continuity. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373610.

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation). 2020d. School Reopening. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373275.

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation). 2020e. International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030. Paris: UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/FIELD/Beirut/video/TF.pdf.

- UNICEF (United Nations Children Fund). 2018. Learning Through Play. Strengthening Learning Through Play in Early Childhood Programs. New York: UNICEF.

- Viner, Russell M., Simon J. Russell, Helen Croker, Jessica Packer, Joseph Ward, Claire Stansfield, Oliver Mytton, Chris Bonell, and Robert Booy. 2020. “School Closure and Management Practices During Coronavirus Outbreaks Including COVID-19: A Rapid Systematic Review.” The Lancet 45 (5): 397–404. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X.

- Webster, Paul. 2020. “Virtual Health Care in the Era of COVID-19.” The Lancet 395 (10231): 1180–1181. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7.

- Whitebread, David, Marisol Basilio, Martina Kuvalja, and Mohini Verma. 2012. The Importance of Play. Brussels: Toy Industries of Europe. http://www.csap.cam.ac.uk/media/uploads/files/1/david-whitebread—importance-of-play-report.pdf.

- World Health Organisation. 2020a. WHO Director General’s Opening Remarks at the Mission Briefing on COVID-19. World Health Organisation: March 12th March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-mission-briefing-on-covid-19—12-march-2020.

- World Health Organisation. 2020b. Helping Children Cope with Stress During the 2019-NCoV Outbreak. Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/helping-children-cope-with-stress-print.pdf?ua=1.

- Zhang, Han, Paula Nurius, Yasaman Sefidgar, Margaret Morris, Sreenithi Balasubramanian, Jennifer Brown, Anind K. Dey, et al. 2020. “How Does COVID-19 impact Students with Disabilities/Health Concerns?.” arXiv. September 1. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.05438.