ABSTRACT

This article sets out to discuss physical prerequisites for creativity. Creativity has come to be regarded as one of the most valuable attributes a person can have, at least in today’s Western societies. This article builds on and incorporates material from a Swedish project called Entrepreneurship Liminal space, Creativity, and Understanding. The article covers analysis from interviews and video observations from two different milieus especially planned for creativity. Based on observations and interviews, the article’s goal is to emphasize and discuss the importance of understanding the physical aspects of creativity. Theoretically, the paper highlights the theory of affordances through an underlying theoretical intention is the way of regarding children as agents. Most significantly, this study contributes to the development of knowledge and understanding about how educators in schools, museums, and other educational institutions can create prerequisites for creativity.

Introduction

Creativity has come to be regarded as one of the most valuable attributes a person can have, at least in today’s Western societies (Craft Citation2003; Craft and Jeffrey Citation2008). Young children’s creativity is now being compared to school knowledge and school success, which have primarily been assessed and measured through international studies, national tests, and grades (Beghetto and Kaufman Citation2014). In a changing modern era, a developed creative ability is an important attribute (European Commission Citation2012).

Interest in spatial disparities of creativity and the impact of spatial contexts, spatial settings, and spatial relations on creativity did not evolve until the late twentieth century (Meusburger Citation2009). Many researchers today believe that imagination and creativity should not only be regarded as a personal characteristic that some people possess (Craft Citation2003; Glăveanu Citation2011). It is increasingly argued that creativity actually belongs in ‘communities’, residing in the ‘spaces’ between individual minds, rather than being sited entirely in the individual. The implications of this stance are that creativity is rooted in a democratic practice of sharing and learning and is less a result of individual genius but more of sociallyshared ideas. Glăveanu (Citation2011) argued that the creator does not create in a vacuum but in a physical and social environment, and the creative process is intrinsically linked to this environment.

Beghetto and Kaufman (Citation2014) argued that educators need to understand the physical environment as a component that influences creativity, and it is of great importance to understand how learning environments should be designed and planned to create the conditions for creativity. Even if human creativity is resilient, certain conditions can suppress or expand it.

The article covers analysis from interviews and video observations from two different environments especially planned for creativity. The reason for choosing two non-traditional educational environments was in the interest of being able to crystallize physical aspects of creativity, thereby requiring two environments that are specifically stated to stimulate creativity. On the other hand, the view of the school as an arena for learning is becoming increasingly questioned and problematized. Where learning should take place and with which resources are areas that today are not obviously given (Selander Citation2017). For example, with this change, museums and science centers are more and more being regarded as places for learning.

Furthermore, Hackett, Procter, and Seymour (Citation2015) highlighted the need to study various spatialities in children’s lives to understand their meaning-making processes during childhood. Therefore, one needs to study a diversity of environments that children meet and spend time in during childhood, such as museums and playgrounds.

The aim is to analyze and describe the physical prerequisites of creativity. The research questions are as follows:

What characterize those physical environments specifically planned for creativity?

Which affordances emerge in the interplay between the children and those environments?

Theoretical assumptions

Fundamental in the theoretical framework is to consider human actions as mediated and not separated from the milieu in which they are carried out. Wertsch (Citation1991) emphasizes that human actions are not isolated and do not occur in a vacuum, but are mediated by ‘mediational means’ – that is, cultural tools such as language, concepts, objects, routines, forms of expression and ways of doing things in a cultural context. Mediation is best thought of as a process involving the potential of cultural tools to shape action, on the one hand, and on the other, the unique use of these tools (Wertsch Citation1995). Accordingly, there are a horizon of possibilities in cultural tools but at the same time in the actions there is only one unique specific use of these. This reciprocal doubleness also exists in the theory of affordance since everything could have a variety of affordances but you can define an affordance only in relation to an individual’s actions.

The concept of agent is in this context not only understood as the individual as an agent, that is the person who is doing the acting. Rather the agent is the ‘agent-acting-with-mediational-means’ (Wertsch Citation1998, 24). Wertsch specified that the agent, the mediational means, the action, the scene, and the purpose, should all be considered.

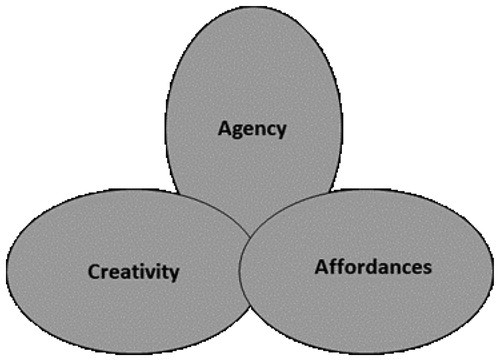

The concepts of creativity, affordances, and agency will now be outlined. Later in the result section, these concepts will be further elaborated. gives a picture of the fact that these concepts belong to each other and also how they presuppose each other.

Places and creativity

Stein (Citation1953) claimed that an interaction exists between the individual and the environment in creative processes. However, it was not until the late 1980s that mainstream research on creativity turned to the fact that situations and environments have an impact on creativity (Meusburger, Funke, and Wunder Citation2009). It is noteworthy that even if there were an understanding of the interactions between the individual and the environment, most authors have written about organizational, cultural, or socioeconomic factors, not about the spatiality of creativity. Mounting evidence shows the creative process does not take place ‘in the mind’ of a person, according to his or her intentions and plans, but it is actually played out in interactions with a physical and social world (Meusburger, Funke, and Wunder Citation2009). When it comes to places for creativity, it could be said that they is a milieu that is a possibility or potentiality not an actuality. Those possibilities must be activated by human interaction or communication. Mcleod et al. (Citation2017) name materials and spaces that stimulate creativity as open ended, which indicates that there is a wide variety of affordances.

Vygotsky (Citation1995) described human actions as either reproductive or creative and combinatorial. The act of recreation involves the repetition of past creative patterns of action and revival of past traces or experiences. Actions of a more creative kind are based on combinatorial actions that combine and create new ones based on past experiences.

Whether or not the actions occur individually or in the interaction, creativity is considered discovering and creating something new based on past experiences. Nelson (Citation2007) described children’s negotiations with physical material for transformations, which, he believed, nurtures children’s imagination and creativity.

Cremin et al. (Citation2015) revealed that when children are afforded opportunities to individually or communally generate ideas and strategies, it stimulates their creative capacities. This takes place in playful and exploratory contexts where children can engage with resources, ask questions, collaborate, and often also be supported by a teacher. According to Meusburger, Funke, and Wunder (Citation2009), a creative environment represents a certain potentiality that must be activated through human interaction. This interactional standpoint is what makes the theory of affordance meaningful in this study, which will be described in the coming section.

The environment as a set of affordances

According to Gibson (Citation1986), an affordance is in one way objective, physical, and real, and also something psychological and more elusive, because it is also found in the observer. The constituents of affordance originate both from the environment and from behavior (Gibson Citation1986). Affordance is also dependent on the relation between the individual and the observer in the environment itself. This conceptualization is emphasized as a complementarity, a holistic nondualistic worldview. The affordance supports and limits human actions in the surrounding environment and is relative to the individual. Nevertheless, the ‘affordance is neither an objective property nor a subjective property; or it is both’ (Gibson Citation1986, 129). It is both related to the environment and the behavior of an individual, including being both physical and psychical.

Furthermore, the concept of affordance is related to the ability of the observer to perceive the surrounding environment (Rietveld and Kiverstein Citation2014). Greeno (Citation1994) emphasized that affordances relate attributes of things in the surrounding environment, to the activities of agents with various abilities. An ability relates attributes of agents to an activity ‘with something in the environment that has some affordance’ (Greeno Citation1994, 338). He claims the inseparable relationship between affordances and abilities which can be understood as affordances and abilities co-define each other.

Previous studies showed that when environments or materials are static and have a high degree of predetermined planned offers, children discover a narrower variety of affordances (Eriksson Bergström Citation2013). When they played in role play rooms, they played how they were expected to play there (i.e. they discovered the offers they were expected to discover). These games were more varied in natural and unplanned environments, because the children discovered a wider variety of affordances in these environments. When children were playing in these more neutral environments, they also talked to each other more (Eriksson Bergström Citation2013). Neutral material such as sticks has a broad variety of affordances that encouraged the children to talk and negotiate with each other. The play then became more collective.

How the environment around us is planned creates different spaces and constitutes what they can offer. The appearance or design of the environment can offer different functional possibilities. People discover and take in the information that characterizes a place, and that information identifies the place as being suitable for certain activities and less suitable for others. In this study, the theory of affordance is used to understand people’s interplay with physical environments on a specific and individual level. Some environments have affordances that are easy to collectively discover, whereas other environments are more difficult to interact with, which means that different actions can take place. Some affordances can be perceived more easily and directly than others. Meusburger (Citation2009) stated that these affordances ‘convey a great deal of information without elaborate processing by higher brain centers’ (Citation2009, 135). The individual can perceive the affordance with little or no complex interpretation. Other types of affordances send more ambiguous or polyvalent messages, which means that an individual must use and trust his or her knowledge base, memory, and ability to recognize and interpret patterns, as well as the social-psychological group dynamics.

Places, spaces, and agency

James (Citation2009) pointed out that the origin of the understanding of children’s agency can be traced back to the 1970s. Up till then, the view of childhood, as a preparatory period for adulthood, had been permanently unchanged and children were seen as dependent receivers of adults’ actions. Today there is a new paradigm, where children are understood as being social actors who both create and are created by the circumstances they encounter (Qvortrop Citation2005; James et al Citation1998). According to Corsaro (Citation2011), a big change in childhood sociology is that children are seen as active and participatory in shaping and changing the reproduction of the childhood of which they are participants. This is a change that makes the relations between the concepts of production and reproduction visible, the difference between being a producer respective to a reproducer (Vygotsky Citation1995).

There is a discrepancy between the concepts of place and space, which belongs to whether or how much children are allowed to interact with the physical environment. According to Fog Olwig and Gullœv (Citation2003), spaces that are designated for children are considered to be child friendly (i.e. they are said to meet children’s needs and interests). However, these spaces only represent the adults’ view of the kinds of places that they think are suitable for children, which most often are safe, protected places that are separated from other spaces and often controlled by adults. Children themselves find these spaces too restricting, preferring to create their places on their own terms. In relation to the extent of children’s participation in the design and function, that place is often limited.

Places are places where children interact more with themselves and create themselves. Schools are a sort of institutional space intended for the schooling of children, and places are to be seen as places used by children for play. Another way to express it is with the concept of environments of children, which are leftover kinds of spaces that children appreciate and use for their own. Environments for children are conversely specifically designed and planned with pedagogical and fostering intentions for the children’s best interests. The difference between them deals with the concept of agency.

Methodology

The result section contains data from interviews and observations from a Swedish project called Entrepreneurship Liminal space, Creativity, and Understanding. This project took place at a science center and a creative recycling center, inspired by Reggio Remida Center (see Parnell, Downs, and Cullen Citation2017). Both are semi-institutional educational places that teachers can use during the day and both places were chosen because of their clearly purpose of being planned and designed to stimulate creativity. All of the groups were observed with a handheld video camera that followed the children’s activities. The recorded sequences are of different length which has to do with the children’s willingness to be filmed, if they in any way seemed to reject or seemed uncomfortable with the presence of the camera the researcher paused the filming. The observations were supplemented with two semi-structural interviews with educators working in these environments. Both interviews were about one-hour long, and recorded with a video camera while walking through the different rooms and places in these two milieus.

In the Creative Recycle Center two different child groups were observed, each group at three occasions. Group A consisted of four children aged 3–4 years, and group B of three children 4–5 years old ().

Table 1. Data from the Creative Recycle Center.

At the science Center there were four different groups of children that were observed. At two occasions two different groups of children from two preschools were observed, called preschool 1 and preschool 2. (see ). Two groups of children aged 6–8 years old were also observed in activities after school. Activities that were led by one pedagogue from the Science Center. Those two groups were observed each at two occasions.

Table 2. Data from the Science Center.

Analysis

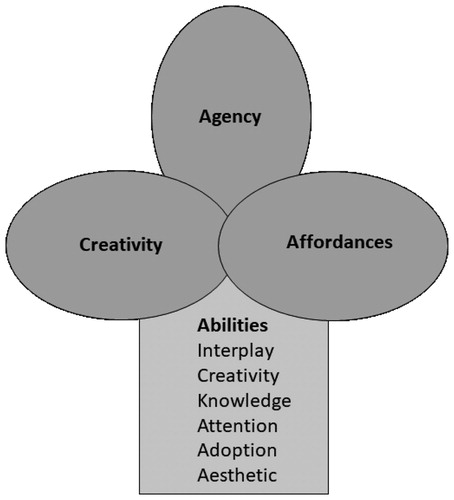

The data were analyzed by a thematic analysis. An abductive method was used in the thematic analysis, which means a pragmatic approach that allows reasoning to move back and forth between theories and empirical evidence (Peirce Citation1990). The understanding was gradually allowed to emerge through a movement between theory and empiricism. In the first phase, initial codes were generated in the interview respective observation data. By markers of different colors both the interviews and observations were coded. A next subphase was to take the theoretical concepts of affordance, agency, and creativity into consideration with the codes. In the second phase, themes were identified by patterns, similarities, or variety among the codes. When the codes appeared several times in the data, in different places; both in the interview like observation data, a theme was established. Of importance is to relate the emerging themes to the research question (Gray Citation2018). Thus, by asking what characterize physical places specifically planned for creativity and by asking which affordances that emerge in the interplay between the children and the environments, the themes of different abilities were developed and various abilities to perceive affordances became visible. Finally, six different themes were defined which were named as abilities: knowledge-ability, adoption-ability, attention-ability, esthetic-ability, interplay-ability, and creativity-ability. Those themes are substantiated of both the pedagogue’s expressions, but not at least the children’s acts.

Ethical issues

The project followed the Swedish Research Council’s guidelines (Citation2011) for good research practice and the Lean research framework. The different principles on which the Lean framework is based, such as accuracy in all research steps and methods, respect for all individuals involved in the project, relevance, and meaningfulness for all involved, and properly proportionate balance between costs and project design, were taken into account in the project’s implementation and data collection. In particular, it has been taken into account to try to interpret and get into the children’s perspective. If they expressed unwillingness to be filmed, filming was canceled. The researcher has put a lot of effort into trying to interpret different expressions of the children’s possible resistance to being filmed. The Research Council’s (Citation2011) ethical research principles; the information requirement, the consent requirement, the confidentiality requirement, and the use requirement have been adapted in a special document showing how an individual’s protection can be satisfied in a particular video use (HSFR Citation1996). Concerning the consent requirement (i.e. that the participants have the right to decide on their participation), the custodians approved in writing the participation of their children in the study. Regarding the confidentiality requirement, information was provided stating that materials, such as notes and recordings, were securely stored.

Results

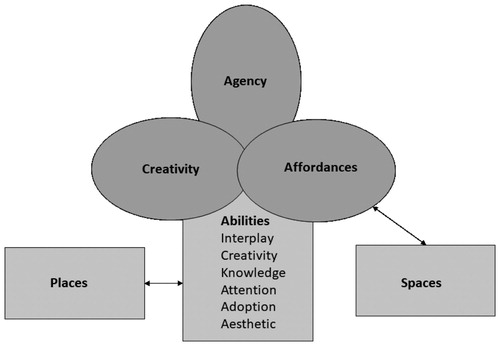

As shown in , six abilities have emerged through the abductive analyses between the theoretical concepts and the empirical data. In , those six themes are placed in the middle; in the intersection between the three concepts of agency, affordances, and creativity.

The themes are named knowledge-ability, creativity-ability, interplay-ability, attention-ability, adoption-ability, and esthetic-ability.

In this article, I have chosen to highlight three of them; knowledge-ability, interplay-ability, and creativity-ability. Shortly, adoption-ability is understood and derived from the perspective of a child’s agenda. The exhibition planner expressed this by saying ‘kids like this’ or ‘children need this’. Attention-ability are affordances that aim to be a moment of surprise to catch the attention of children with aspects like novelty and excitement. There are also esthetic affordances, according to the exhibition planner the exhibition should also be esthetically appealing. For example, they added stars inside a cave to make it cosier and more beautiful.

Knowledge-ability

When it comes to Knowledge-ability, this theme is very closely connected to a learning object: the object of knowledge. The educator from the Science center gave examples of the exhibition planned to convey facts and understanding about for example different types of rocks. In the exhibition, there is, for example, a possibility for visitors to call a geologist, which can be understood as something that creates a red line for the intended learning object. One part of the exhibition area at the Science Center is inspired by a Swedish children’s book, Alfons Åberg. In that area there are, besides the story, affordances of different mathematical tasks for the children. In Alfons bedroom, there is a picture with a game where a snail hangs in a string and you are supposed to move it over the different numbers. In the picture, there are written instructions how to play the game. Two girls, Elsa and Freja, 5 years old, enter the room.

They both stand in Alfon's bed to reach the picture.

Elsa – now I'll check the Snail. //She grabs the snail that hangs in a string on the picture with numbers. //

Elsa counts – One, two, three four. //Freja observes.//

Nils, touches the old man at the picture who is going to point at different numbers.

/ … /The teacher comes, bending down to their height. She reads on the sign: Ask a question to the mathematician. You can choose plus, or minus or multiplication.

Nils – multiplications. / he touches the arrows and the man on the board. Martin and the teacher are watching.

Martin – and now he (the old man) points to ten. / he shows with his hand.

Nils changes the arrow.

The teacher – and now?

Martin – Twenty.

Interplay-ability

The teacher from the reuse studio said that the room is planned to create opportunities for children to explore, experiment, and transform the material and the room. The room is planned primarily on the basis that the children will be offered opportunities to negotiate with the room.

Although the teacher at the reuse studio expressed that the environment is well planned and structured, there is also a space that reflects a permissive and waiting attitude that is intended to give children room to change and work with the environment. For example, she said that ‘from the beginning it is mostly about just being in here’ and she thinks that one has to let the children have such a period before they start working in the room. She spoke about the fact that one consciously decorates the room with a large amount of unplanned and loose material to give the children freedom. She said, ‘Working with the loose material can also be a freedom; that is what I think it is … a freedom, freedom to change.’

The view that the child’s agency should be given space in the room thus becomes clear. When we discussed how the overhead machine, which is in the room, is used by the children, she expressed that it has great value because it stimulates and arouses so much wonder in the children. She believed that in the construction around the apparatus, it becomes very obvious to the children that they are the ones who influence as they follow what happens in the exposure on the wall of what they are building. She said, ‘It’s great when they get to test and try for themselves and when they find out its themselves who does that.’

This interplay-ability is not in the same way visible in the exhibition planners’ statements. She spoke about how children can crawl in the huts and put their hands in holes and feel things, but the affordances are not about children affecting the exhibition in some way through interaction. When the learning objects are expressed very clear, like in the exhibition, the abilities of interplay and creativity do not become as visible, it seems to reduce the parts of agency and creativity. The environment becomes a space that is planned for the children.

However, interplay-ability exists in the Imagination Playground area at the Science center, where Alva has built a staircase of pillows. In that area there are a learningobject that presupposes the children to interact and produce. Alva lifted one of the pillows and put it on top of the other. She tried to balance them exactly so that the upper cushion should not tip over. She got it right and then lifted a third pillow and put it in place on the other pillow, then started climbing the steps she created to sit on the top pillow.

Creativity-ability

The fact that the children should be allowed to negotiate and transform the material appears to be a strong motive behind how the room at the reuse studio is planned. The pedagogue attached great importance that the material should encourage the children to find solutions to the unfinished material.

The only time she mentioned the children’s negotiations between each other was when she emphasized that children have different abilities to fantasize and transform and that they complement each other. She said that some children have ‘a lot of construction games in themselves’, whereas others have more ability to transform and fantasize more freely. The children’s actions with each other were also highlighted when she spoke about a context where some children wanted to build a ‘prisoners at the fort’ environment: ‘Then they started to stack up here and there bits and pieces of stuff … and they picked up threads in here so they tied threads and then they gave keys and so there.’ She stated the adults at the time could only be passive and not do anything, because the kids ‘just owned the whole environment, so then all these different environments interacted, because they took the material they needed, it was fantastic’. It is if their agency in the interplay with openness of affordances gives rise to the creativity, and also encourages them to negotiate an agreed goal or aim with the activity. Both in the reuse space and the rooms at the Science center, there are a lot of material, so that one can test ideas and change plans and still the material is enough. The materials are also varied, from paper to wood and plastic materials in various sizes, shapes, and colours.

When children discover affordances in the physical environment, it is sometimes characterized by pure imagination and association; a kind of ‘as if’ affordance. Certain affordances seem to be more easy to perceive and the agency then drives the perception of alternative affordances and the creative productive acts are visible. One example was when Alva attached a long ball pillow between two other pillows and told the adult that it was a flagpole. The game went on and suddenly Nils lifted her flagpole up and was about to use it for something else. Alva grew upset and erupted.

‘No! No! Just the one I used to the flag, it was the flagpole that Nils removed.’

‘Ah, but Nils didn’t know that. Could you show him how you did it?’

‘It was this one.’ [She retrieves another roll.] ‘And it sat here in the middle and it was the flagpole.’ [She now retrieves the ball roll that Nils put aside.]

‘But show Nils how you did.’

Alva shows and says, ‘Like this, and it has to stay this way.’

‘Ah, oh, it was a flagpole. And we thought it was such a roll you could roll.’ [She looks at Nils, who is quiet.]

Discussion

Glăveanu (Citation2011) and Craft and Jeffrey (Citation2008) argued that creativity is not an intrapersonal process but more a social interpersonal phenomenon. Within the theme of interplay-ability, children could clearly transform ideas into action in the building constructions they undertook. One example of this is from an excerpt above, when Alva and Nils were building a flagpole and need to communicate about the affordances of the building pillows they are using. They communicated and collaborated more clearly in this interplay-ability than in the environments that were more planned to convey facts or knowledge. Those transformations, visible as children’s negotiations with the material, and their collaboration also stimulates children’s imagination and creativity (Cremin et al. Citation2015; Nelson Citation2007). When learning objects are preplanned not to involve productive acts they seem not to appeal the agency. According to Eriksson Bergström (Citation2013, Citation2017), children talk more to each other when playing in environments with a high degree of neutral materials. Neutral material such as sticks has a broad variety of affordances that encourage children to talk and negotiate with each other. This study complements those findings by adding that those interactions also belong to creativity.

A big change in childhood sociology is that children are seen as active and participatory in shaping and changing the reproduction of the childhood of which they are participants. The difference between being a producer and a reproducer becomes visible. The parts of those environments that encourage the children to produce instead of reproduce are more often used by the children. As Meusburger, Funke, and Wunder (Citation2009) argued, a creative environment represents a certain potentiality that must be activated through human interaction. Theoretically this can be expressed like this ‘activation’ needs its agents. When considering Wertsch (Citation1998) definition of agents, which emphasize the interplay between person – place – mediational means, it becomes clearer that the environment itself can’t be a creative place. This study gives examples of how this possibility space can be filled with affordances that are perceived through interplay-ability and creativity-ability, which underlines that productive acts demand or can be stimulated in those types of environments.

Conclusions

As mentioned above, there is a discrepancy between the concepts of place and space that belongs to whether or how much children are allowed to interact with the physical environment. The concept of space and place is situated in the lower parts of .

Spaces represent the adult view of what they think is suitable for children (Fog Olwig and Gullœv Citation2003), this study brings that reproductive acts are more suitable in those environments. Places are the environments where children can interact, negotiate, and kind of owning the environment. Thereby more productive acts are visible in places.

When it comes to knowledge-ability, it becomes clear that the pedagogues sometimes strived to get the children to perceive specific learning objects, with an ambition that children should perceive and reproduce facts. However, as mentioned, the children also did act upon the knowledge-abilities the best they could. Sometimes they were too short to perceive the affordance by sight, or other times they needed to be readers, which most of the preschoolers weren’t. The concept of agency becomes important in the differences between the themes. It is in line with Wertsch (Citation1998) definition of agency, where the agency consists of a person interplaying with the environment. Of particularly interest is that this also sheds light upon the differences in producing and reproducing actions. Creativity belongs to actions of production; actions of a more creative kind are based on combinatorial actions that combine and create something new (Vygotsky Citation1995). Agency belongs to a subject who is a producer, and a producer can be creative. Moreover, according to this study, this chain must be situated in a context that is characterized by interplay-abilities and creativity-abilities. However, this also indicates that there are no physical aspects that in themselves can stimulate creativity; it must arise in the interplay between agency and affordances, between the individual and the environment. Accordingly, if an environment should enable to stimulate creativity you cannot just plan for a didactic learning object that does not include the agency, it then becomes learning spaces at the right side in , that not involves the agency and neither creativity.

Even if one cannot forecast what effects a creative environment will have on creative processes, this study contributes to the development of knowledge and understanding about how teachers and educators in schools, museums, and science centers can create places of creativity in relation to a formulated learning object. Carvalho and Yeoman (Citation2018) mean that many educators are struggling to align their teaching with the learning environment. They argue that analytical tools capable of increasing and facilitate the interplay between pedagogy, place and people and theory, design, and practice would be useful.

When learning environments are planned and designed in more traditional educational environments, such as schools and preschools, didactic learning objects are often central to what the environments will look like. This study contributes to the understanding of schools and other educational institutions’ challenge to balance clearly formulated learning objects with children’s agency, with their creative ability to perceive affordances that stimulate productive acts although there is a clear learning object.

Knowledge-ability needs to be considered in relation to the other five abilities. As a teacher you can plan for a didactic mathematical corner in the classroom but you also need to be aware of that there exist a dynamic between distinct and clearly formulated learning objects and the fact that the agency of children also need to take place and to be allowed or planned for. This article starts with a statement that young children’s creativity more and more is being compared to school knowledge and school success and European Commission (Citation2012) states that a creative ability nowadays is an important attribute. The implications from this study bring that agency, affordances, and creativity together can illuminate six different themes that point out physical prerequisites for creativity.

If learning environments are to be able to meet the demands and expectations of the becoming creative generation, they need to be planned with awareness of how to balance the roles of being a producer and a reproducer with environments that need to be planned, but equally need to be planned for the unplanned.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Beghetto, R. A., and J. C. Kaufman. 2014. “Classroom Contexts for Creativity.” High Ability Studies 25 (1): 53–69. doi:10.1080/13598139.2014.905247.

- Carvalho, L., and P. Yeoman. 2018. “Framing Learning Entanglement in Innovative Learning Spaces: Connecting Theory, Design and Practice.” British Educational Research Journal 44 (86): 1120–1137.

- Corsaro, W. A. 2011. The Sociology of Childhood. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

- Craft, A. 2003. “Creative Thinking in the Early Years of Education.” Early Years 23 (2): 143–154.

- Craft, A., and B. Jeffrey. 2008. “Creativity and Performativity in Teaching and Learning; Tensions, Dilemmas, Constraints, Accommodations and Synthesis.” British Educational Research Journal 34 (5): 577–584.

- Cremin, T., E. Glauert, A. Craft, A. Compton, and F. Stylianidou. 2015. “Creative Little Scientists: Exploring Pedagogical Synergies Between Inquiry-Based and Creative Approaches in Early Years Science, Education.” International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education 3 (13): 404–419.

- Eriksson Bergström, S. 2013. “Rum, barn och pedagoger: om möjligheter och begränsningar i förskolans fysiska miljö.” Diss., Umeå universitet, Umeå.

- Eriksson Bergström, S. 2017. Rum, barn och pedagoger: om möjligheter och begränsningar för lek, kreativitet och förhandlingar. (1. uppl.). Stockholm: Liber.

- European Commission. 2012. Rethinking Education Strategy. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-12-1233_en.htm.

- Fog Olwig, K., and E. Gullœv. 2003. “Towards an Anthropology of Children and Place.” In Children’s Places. Cross-Cultural Perspectives, edited by K. Fog Olwin and E. Gullov, 1–19. New York: Routledge.

- Gibson, J. J. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Glăveanu, V. P. 2011. “Children and Creativity: A Most (un)Likely Pair?” Thinking Skills and Creativity 6: 22–131.

- Gray, D. 2018. Doing research in the real world (Fourth ed.). London: SAGE.

- Greeno, J. 1994. “Gibson's Affordances.” Psychological Review 101 (2): 336–342.

- Hackett, A., L. Procter, and J. Seymour, eds. 2015. Childrens Spatialities: Embodiment, Emotion and Agency. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- HSFR. 1996. God praxis vid forskning med video. Stockholm: Humanistisk samhällsvetenskapliga forskningsrådet.

- James, A. 2009. “Agency.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies, edited by J. Qvortrup, W. A. Corsaro, and M.-S. Honig, 34–45. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- James, A., C. Jenks, and A. Prout. 1998. Theorizing Childhood. Cornwall: Polity Press.

- Mcleod, N., D. Wright, K. Mccall, and M. Fujii. 2017. “Visual Rhythms: Facilitating Young Children's Creative Engagement at Tate Liverpool.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (6): 930–944.

- Meusburger, P. 2009. “Milieus of Creativity: The Role of Places, Environments, and Spatial Contexts.” In Milieus of Creativity, edited by P. J. Meusburger, J. Funke, and E. Wunder, 97-153. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Meusburger, P., J. Funke, and E. Wunder, eds. 2009. Milieus of Creativity: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Spatiality of Creativity. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Nelson, A. 2007. Meningserbjudanden kring genus i barns leksaker – om lek som medierad handling. In Barns lek – makt och möjlighet. Centrum för barnkulturforskning. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet.

- Parnell, W., C. Downs, and J. Cullen. 2017. “Fostering Intelligent Moderation in the Next Generation: Insights from Remida-Inspired Reuse Materials Education.” The New Educator: Nature and Environmental Education in Early Childhood 13 (3): 234–250.

- Peirce, C. S. 1990. Pragmatism och kosmologi. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Qvortrup, J. 2005. “Varieties of Childhood.” In Studies in Modern Childhood, edited by J. Qvortrup, 1–20. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rietveld, E., and J. Kiverstein. 2014. “A Rich Landscape of Affordances.” Ecological Psychology 26 (4): 325–352.

- Selander, S. 2017. Didaktiken efter Vygotsky. Stockholm: Liber.

- Stein, M. 1953. “Creativity and Culture.” Journal of Psychology 36: 311–322.

- Swedish Research council. 2011. Forskningsetiska principer inom humanistisk-samhällsvetenskaplig forskning [Elektronisk resurs]. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1995. Fantasi och kreativitet i barndomen. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Wertsch, J. V. 1991. “A Sociocultural Approach to Socially Shared Cognition.” In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition, edited by L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, and S. D. Teasley, 85-100. American Psychological Association.

- Wertsch, J. 1995. Sociocultural Studies of Mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wertsch, J. 1998. Mind as Action. New York: Oxford University Press.