ABSTRACT

Using data from more than 7000 children from the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child (MoBa) study, this study explored the role of school readiness and teacher–child closeness in the early child education and care (ECEC) setting for the prospective academic and social development of children with early externalizing problems. Mother, ECEC teachers, and schoolteacher ratings were applied. Latent moderated mediation analyses within a SEM framework were performed. Early externalizing problems at age three were associated with less school readiness at age five, but this association was weaker among children with closer teacher–child relationships. School readiness mediated the link from early externalizing problems to later academic and social adjustment difficulties, but this long-term indirect effect also decreased with increasing levels of teacher–child closeness. With regards to intervention efforts, the study demonstrates the potentially important role of ECEC teachers for the long-term social and academic adjustment of children with early externalizing problems.

Externalizing behaviors in childhood, such as aggression, inattention, and hyperactivity, are the most prevalent mental health problems during the preschool and early school years and are associated with increased risk of long-term individual and societal costs (Moffitt et al. Citation2011; Serbin, et al. Citation2015; Vasileva, et al. Citation2021). Children who display such behaviors often struggle both socially and academically across childhood and adolescence, and particularly in the schooling context (Kouros, Mark Cummings, and Davies Citation2010; Okano et al. Citation2020; Rimm-Kaufman, Pianta, and Cox Citation2000; Gutman,, Joshi, and Schoon Citation2019; Huber, Plötner, and Schmitz Citation2019). Given that social competence and academic achievement represent some of the most fundamental prerequisites for healthy functioning and positive adjustment throughout life (Spengler, Damian, and Roberts Citation2018; Moffitt et al. Citation2011; Kjeldsen et al. Citation2016), it is of crucial importance to gain a better understanding of protective factors and processes in key developmental contexts that may serve to enhance the social and academic competence of children with early externalizing problems.

With the purpose of early intervention efforts in mind, one such context may be the early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings, and particularly the affective quality of the relationship that young children have with their teachers (Mantzicopoulos, Citation2005; Hamre and Pianta Citation2001). Yet, little research has examined the potential influence of positive teacher–child relationships in this setting for the long-term adjustment of children with externalizing problems. Thus, the aim of this study was to explore the moderating effects of teacher–child closeness on the prospective associations between early externalizing behaviors, children’s level of school readiness, and later academic and social adjustment in school. To this end, this study uses longitudinal data from more than 7,000 children followed across the childhood years in the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort study (MoBa).

Early externalizing problems and later adjustment

The period of preschool age (3–6 years) represents a highly important and sensitive time for children’s behavioral, cognitive, socio-emotional, and psychopathological development and functioning (Green and Rechis Citation2006; Huber, Plötner, and Schmitz Citation2019). Dynamic system theories on child development (e.g. Sameroff Citation2009; Masten and Cicchetti Citation2010) advocate that such different developmental domains are likely to reciprocally influence one another (i.e. developmental cascade processes) in which difficulties in one domain may undermine functioning in other domains, which in turn may exacerbate the initial problems or increase the risk for problems in other domains. In this sense, early externalizing problems could set in motion a negative cascade of events (i.e. the adjustment erosion hypothesis; see Masten, Burt, and Coatsworth Citation2006; Moilanen, Shaw, and Maxwell Citation2010) where disruptive behaviors initially operate to inhibit the development of academic and social competence, possibly by interfering with children’s ability to pay attention to and engage in classroom learning and/or their capacity to adequately process social information and bond with adults and peers (Chen, Rubin, and Li Citation1997; Bornstein, Hahn, and Haynes Citation2010; Trentacosta and Shaw Citation2009). Feelings of incompetence and low mastery in academic and social domains could, in turn, further intensify externalizing child behaviors (i.e. the incompetence hypothesis; see Masten et al. Citation2005; Trentacosta and Shaw Citation2009).

There is some evidence for such cascading processes at work in the research literature. With regards to academic performance, findings typically demonstrate that the direction of influence initially flows from early externalizing problems to subsequent academic problems, whereas influence from academic problems to subsequent externalizing problems first seem to emerge at later ages (Okano et al. Citation2020; Moilanen, Shaw, and Maxwell Citation2010; Burt and Roisman Citation2010). With regards to social competence, however, findings concerning the direction of influence are less clear (Bornstein, Hahn, and Suwalsky Citation2013; Burt and Roisman Citation2010; Bornstein, Hahn, and Haynes Citation2010; Hay and Pawlby Citation2003). Notwithstanding, most studies typically report strong and negative within-time associations between externalizing problems and social competence problems across most age groups (Huber, Plötner, and Schmitz Citation2019), and there is also some evidence for the presence of bidirectional associations during the preschool and school years (Burt and Roisman Citation2010). On this background, externalizing problems early in childhood are likely to negatively predict later academic achievement and may also have a negative influence on children’s social competence development over time.

Explanatory factors and intervening processes

Previous research has shown that third factors that exist within the child, such as language problems (Zadeh, Im-Bolter, and Cohen Citation2007) or executive functioning deficits (Barkley and Fischer Citation2011), may precede problems in different developmental domains, including externalizing problems and social and academic difficulties, or explain associations between them (see Hinshaw et al. Citation1992; Kulkarni, Sullivan, and Kim Citation2020). There is also research evidence for a negative link between executive function deficites and lower levels of social and academic maturity (i.e. school readiness) among preschoolers with externalizing problems (Graziano et al. Citation2016). Thus, in the present study, we focus on the role of school readiness as it remains to be known if differences in children’s school readiness may matter in the association between early externalizing problems and later adjustment difficulties in school.

In broad terms, school readiness signifies the mastery of early competencies, including academic and cognitive skills, language abilities, interpersonal competencies, behavioral adjustment, and social-emotional functioning (Blair Citation2002; La Paro and Pianta Citation2000; Janus and Offord Citation2000). These competencies are suggested to be essential for children’s social and academic adjustment because they reflect strengths in skills, including self-regulation, cooperation, self-awareness, and attention, that are likely to aid children to participate in school-related activities and to build positive relationships with others (Denham, Citation2006; Doctoroff, Greer, and Arnold Citation2006; Guhn et al. Citation2016; Nix et al. Citation2013).

Another factor that may influence the course of development for children with early externalizing problems is the relationship between children and their ECEC teachers. In Norway, 97% of all children attend ECEC (i.e. kindergarten) and children typically enter the ECEC around age one year before school entry at age six (Statistics Norway, Citation2020). The role of the ECEC is to offer full-day care for children, and ECEC teachers perform caregiving functions resembling those of parents, including providing emotional support, teaching coping skills, and regulating children’s social interaction (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2017). Given the amount of time that children spend in this setting, ECEC teachers are likely to have an important socializing function with regards to children’s academic and social competence development, with research particularly emphasizing the quality of the child–teacher relationship as a critical factor for children’s adjustment (Baker, Grant, and Morlock Citation2008; Hamre and Pianta Citation2001; Myers and Pianta Citation2008). Teacher–child relationship quality refers to the affective nature of a child’s relationship and interactions with his or her teacher and is typically described in terms of the level of conflict (e.g. patterns of negative, hostile, and tense interactions) or closeness (e.g. warmth, support, and open communication) within the relationship (Hamre and Pianta Citation2001).

Children who exhibit externalizing problems are more likely to experience less close and more conflictual relationships with their teachers (Henricsson and Rydell Citation2004; Mejia and Hoglund Citation2016). Yet, as research has shown that close and warm teacher–child relationships may not only have positive bearings for adjustment outcomes of children in general (Burchinal et al. Citation2002; Zhang and Nurmi Citation2012), but perhaps especially so for children with behavioral difficulties, such as externalizing problems (Baker, Grant, and Morlock Citation2008; Hamre and Pianta Citation2005), the focus in this study will be on the role of teacher–child closeness

For instance, children identified as at risk for later school failure (i.e. including externalizing problems) in kindergarten are found to show better academic achievement if they experience more instructional, warm, and emotional support from school teachers compared to at-risk children who do not receive such teacher support (Hamre and Pianta Citation2005; Baker, Grant, and Morlock Citation2008). Similarly, closer teacher–child relationship has been found to alleviate the negative link between poor executive functioning and lower school readiness in preschool children characterized with either at-risk or clinically elevated levels of externalizing behavior problems (Graziano et al. Citation2016). Furthermore, longitudinal studies have demonstrated that teacher–child closeness during the ECEC years is associated with less aggression, fewer disruptions, less teacher–child conflicts, and more positive work habits in subsequent grades for children in general (Hamre and Pianta Citation2001; Howes Citation2000).

Thus, teacher–child relationships in the ECEC setting characterized by warmth, closeness, and support are likely to serve a protective function for both the social and academic adjustment of children with externalizing difficulties, and this early influence may also extend into the school years.

The present study

Based on previous research findings, it was expected that higher levels of externalizing behaviors in early childhood would be prospectively associated with poorer school readiness in the ECEC and with less academic and social competence in third grade. Further, school readiness was expected to account for the association from early externalizing problems to later social and academic difficulties. However, it was expected that this negative indirect association would decrease with increasing levels of teacher–child closeness. Moreover, given that externalizing behavior problems and language difficulties often co-occur in preschool children (Wang, Aarø, and Ystrom Citation2018), and that children with preschool language difficulties often exhibit lower school readiness performance (Justice et al. Citation2009; Pentimonti et al. Citation2016), we control for language problems in all analyses. Previous research using the same sample as the current study have also demonstrated gender differences in externalizing problems and school readiness among preschoolers Brandlistuen et al. (Citation2020), as well as showing parental socioeconomic status to be associated with teacher–child relationships quality in ECEC (Alexandersen et al. Citation2021). For this reason, we also control for gender and socioeconomic status in our analyses.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The present study utilizes data from participants in the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study [MoBa] including available ECEC and schoolteacher questionnaires. The MoBa Study is a prospective, population-based, pregnancy cohort conducted by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (Magnus et al. Citation2016). Between 1999 and 2008, women pregnant in their second trimester from all over Norway were recruited for participation in the study. Among these women, 40.6% consented to participate. There were no exclusion criteria. Participants have since been followed up by questionnaires administered during pregnancy and after birth up to child age 16 years. In total, the cohort now includes 114,500 children, 95,200 mothers and 75,200 fathers. Pregnancy and birth records from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN) are also linked to the MoBa database (Irgens Citation2000).

The current study uses mother rated questionnaire data from when the children were three, five and eight years of age. In addition, we include questionnaire data from ECEC teachers and primary school teachers of children born between 2006 and 2009 that were invited to evaluate the children’s functioning and development at an average child age of 5.5 (response rate = 40%) and 8.5 years (response rate = 43%), respectively (N = 7472).

We use the 12th version of the quality-assured dataset, which was released for research in 2019. The research project is approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) (2015/1324). The MoBa cohort is regulated by the Norwegian Health Registry Act. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Externalizing problems. At child age three years, mothers assessed their child’s level of externalizing problems using selected items from the externalizing subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach Citation1992). The subscale includes 9 items rated on a 3-point scale (from 1 = not typical to 3 = very typical), with questions pertaining to inattention, low concentration, aggression, impatience, and over-activity (e.g. ‘Can’t concentrate, can’t sit still for long’, ‘Can’t stand waiting, wants everything now’, and ‘Quickly shifts from one activity to another’). Previous studies have demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties for the externalizing subscale (Wilhelmsen et al. Citation2021; Nakamura et al. Citation2009). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability estimate for the externalizing subscale was .75.

Teacher–child closeness. At child age five years, ECEC teachers rated the quality of the relationship with the target child by use of the closeness subscale from the Student Teacher Relationship Scale – Short Form (STRS; Pianta Citation2001). This subscale assess the degree to which teachers characterize their relationship with the student as warm and affectionate (e.g. ‘If upset, this child will seek comfort from me’, ‘It is easy to be in tune with what this child is feeling’) with response options rated on a 5-point scale (from 1 = not true at all to 5 = very true). In the present study, only six of the original eight items of the closeness subscale was used, leaving out items more reflective of the child’s communicative skills. The STRS is previously shown to have satisfactory psychometric properties (Birch and Ladd Citation1997; Hamre and Pianta Citation2001; Howes Citation2000), also in a Norwegian preschool sample (Solheim, Berg-Nielsen, and Wichstrøm Citation2012). The Cronbach’s alpha estimate for the closeness subscale in this study was .72.

School Readiness. At child age five years, ECEC teachers rated the target child’s degree of social and cognitive maturity using the School Readiness Questionnaire developed for the Australian Temperament Project (SRQ; Prior et al. Citation2000). The SRQ is a 13-item scale for teachers to rate the child’s level of social (e.g. cooperation with other children, agreeableness, confidence/sociability, and how well the child is adapting to and settling into the ECEC setting) and cognitive school readiness (e.g. concentration, verbalizing in class work, use of materials, and follow instructions) plus fine motor and physical coordination via five-point Likert scales with responses ranging from 1 = having considerable difficulties to 5 = child is coping very well. In this study, we only included all the items representing social and cognitive maturity to create a total mean score school readiness. Previous studies have shown the SRQ to have good psychometric properties and to predict a range of developmental outcomes in children from 5 to 12 years of age (Prior et al. Citation2000). The Cronbach’s alpha for the school readiness measure was .91.

Academic Performance. At child age eight, schoolteachers assessed children’s academic performance through a composite measure comprising the child’s performance in four courses, including reading, writing, Math and English (1 = low to 4 = high). Mean scores were computed with higher scores indicating higher overall school performance across these four courses.

Social Competence. At child age eight years, schoolteachers also rated the child’s social competence using the social engagement subscale of the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS; Gresham and Elliott Citation2008). The subscale comprises seven questions assessing the child’s competence and ability to engage in social interactions with peers (‘Interacts well with other children’, ‘Joins ongoing activities’, ‘Makes friends easily’) rated via four-point Likert scales with responses ranging from 1 = never to 4 = very often. Previous studies have demonstrated that the SISS has good psychometric properties (Gresham et al. Citation2011). The Cronbach’s alpha for the social engagement subscale was .87.

Covariates. Gender, maternal education, and language difficulties were included as covariates in the analyses. Gender was indexed using birth records of boys (n = 3744, 50.1%) and girls (n = 3723) from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Maternal education was derived from the MoBa 15th weeks of pregnancy questionnaire using the mother’s self-reported level of education with response categories ranging from nine-year secondary school to University/college over four years. Due to the small number of participants in the lowest educational categories, the education variable was combined into three categories scored as; (1) up to high school education (20.4%), (2) higher education college/university up to 4 years (44.5%), and (3) higher education college/university more than 4 years (35.1%). Language Difficulties. Language difficulties were measured by eight items from the checklist of 20 statements about language difficulties (Ottem Citation2009). The checklist is a validated Norwegian instrument used to identify children with semantic, receptive, and expressive language difficulties. Preschool teachers rated statements from 1 = ’Does not fit the child/absolutely wrong’ to 5 = ’Fits well with the child, absolutely right’. Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed by using structural equation modeling in MPlus version 8.2 (Muthen and Muthen Citation2017). Path estimates, indirect effects, and conditional indirect effects were evaluated using bias corrected confidence intervals based on 5000 bootstrap resamples with replacement (Hayes Citation2015). Full information maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) was used to correct test statistics and standard errors for non-normality of the observations and to handle missing data (Lodder et al. Citation2019). Model fit was evaluated by values of Root Mean Square of Approximation (RMSEA) below 0.05, and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) above .95 (Hu and Bentler Citation1999). Prior to all analyses, we standardized the latent variables.

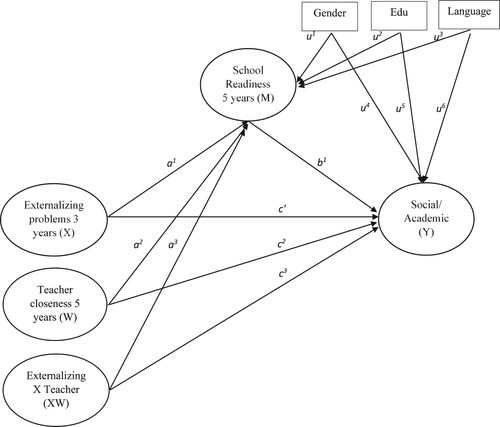

Analyses were carried out in several steps. First, measurement models were estimated through confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) for the externalizing problems, teacher-student closeness, and social skills by constructing one latent factor for each of these measures based on their respective indicators. Second, we examined the direct association between externalizing problems in early childhood and social and academic outcomes in middle childhood (H1) by using path analyses. Third, we examined a mediation model with school readiness as a putative mediator (H2), again applying path analyses. Fourth, we tested whether teacher–child closeness moderated associations of externalizing problems with school readiness (H3) and with academic and social outcomes (H4) by estimating three latent moderation structural equation models (LMS; Klein and Moosbrugger Citation2000), one for each outcome variable, and by simultaneously including childhood externalizing problems, teacher–child closeness, and the product term of these variables as predictors of school readiness and academic and social outcomes. As recommended, we standardized the predictor and moderator variables, following Little (Citation2013) and Hayes and Preacher (Citation2013). Fifth, to test whether teacher–child closeness moderates the indirect prospective path from externalizing problems to academic and social development via children’s school readiness, two moderated mediation analyses were conducted, following Hayes (Citation2015). To this end, we calculated an index of moderated mediation (the a3b index) for each of the models with the academic performance and social competence measures specified as outcomes. The a3b index reflects the change in the indirect effect of the predictor (X) on the outcome (Y) through the mediator (M) for a unit change in the moderator variable (W). The moderated mediation model is represented in its conceptual and statistical form in . Finally, to further probe the conditional indirect effect, we conducted follow-up analyses by estimating the moderated mediation effect at different values of the moderator (i.e. at mean, +/- 1 standard deviations of teacher closeness).

Results

presents descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for all study variables. There were significant relationships between childhood externalizing behaviors at age three years and all study variables, with negative associations found with teacher closeness, school readiness, academic performance, and social competence, and positive associations found with language difficulties.

Table 1. Intercorrelations, means and standard deviations of study variables.

Results from path regression analyses revealed that externalizing problems at age three was directly and significantly related to academic performance and social competence at age eight (paths c’ in and ). Externalizing problems at age three were also significantly associated with the mediator school readiness at age five (path a in and ), and school readiness at age five was significantly associated with both academic performance and social competence at age eight (paths b in and ) controlling for externalizing problems at age three. Results from the indirect path analyses showed school readiness to significantly mediate the path from externalizing problems to academic performance and social competence (paths ab in ), although externalizing problems remained a significant predictor in both the indirect effects models even after the inclusion of the mediator school readiness.

Table 2. Regression coefficients and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for direct, mediated, and moderated mediation models including externalizing problems at age 3, school readiness and teacher closeness at age 5, and academic performance and social skills at age 8.

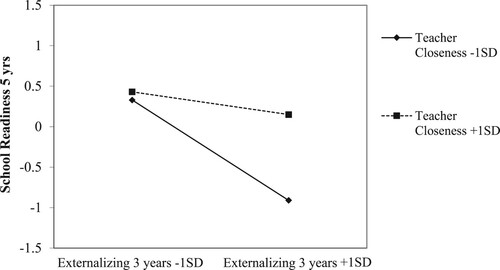

Results from the latent moderation analyses showed that the externalizing problems * teacher–child closeness interaction effect was significant for school readiness at age five (path a3 in and ). The positive coefficient of the interaction term indicated that the negative association between externalizing problems and school readiness becomes less negative as teacher–child closeness increases. illustrates the graphical plot of this interaction effect, demonstrating that when teacher–child closeness increases by one unit, the association between externalizing problems and school readiness becomes less negative, decreasing by .10 standard deviations. Results from the follow-up analyses at different levels of the moderator further showed that the strength of the negative association decreased with increasing levels of teacher–child closeness. No interaction effects of teacher–child closeness at age five were found for the associations between early externalizing problems and the social and academic adjustment outcomes at age eight.

Figure 2. Interaction of child externalizing problems at age three years and teacher-child closeness at age five years predicting children’s school readiness at age five years, reported in standard deviations.

In a final step, we tested whether the strength of the indirect effects observed in the previous step could be conditional on the value of teacher closeness. We estimated two moderated mediation models with academic performance and social competence specified as outcome variables in one model each, and by computing a moderated mediation index (a3b1) for each model. The a3b1 index was computed by multiplying the regression coefficients corresponding to the a3 and b1 paths in . In this respect, the a3b1 index reflects the change in the indirect effect for a unit change in the moderator. The index is significant if the 95% CI’s do not include zero, which indicates that the indirect effect depends on conditional values of the moderator.

Results showed that teacher–child closeness at child age five years significantly moderated the indirect effect from externalizing problems at age three years to both academic performance and social competence at age eight years through school readiness at age five (paths a3b1 in ). More specifically, the indirect (negative) effect of externalizing problems at age three years on lower academic performance and social competence at age eight through lower school readiness at age five decreased with increasing teacher closeness, as the slope of the moderated mediation index is positive.

Results from the follow-up analyses further showed that the indirect path toward lower academic performance was significant only when teachers reported average or lower closeness with the child (i.e. at the mean value or 1 standard deviations below the mean,) but that the indirect effect was no longer significant when teachers reported higher levels of closeness with the child (i.e. 1 SD above the mean). In other words, the mediation/indirect effect depended on average to lower levels of teacher–child closeness. A similar pattern occurred for the model with social competence as the outcome variable, in which the indirect effect systematically decreased at increasingly higher values of teacher–child closeness, yet never becoming fully non-significant.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the longitudinal associations between early externalizing problems, school readiness, and later social and academic adjustment in school, and to explore the influence of closeness with ECEC teachers for these direct and indirect associations. First, results showed that early externalizing behaviors at age three years negatively predicted children’s school readiness at age five. However, a positive teacher–child relationship was found to serve as a buffer in that the association between externalizing problems and lower school readiness was weaker among children with closer teacher–child relationships. Second, school readiness significantly mediated the prospective association between early externalizing problems and later social and academic adjustment difficulties at school. However, once again, early teacher–child closeness had a long-term positive influence on this negative indirect pathway as well, as the indirect effect was found to be weaker among children with closer teacher relations compared to children with less close teacher relationships. The implications of these findings are further elaborated below.

In line with previous research findings (Rimm-Kaufman, Pianta, and Cox Citation2000; Bierman et al. Citation2013; Huber, Plötner, and Schmitz Citation2019; Graziano et al. Citation2016), the present study found early externalizing problems to be associated with lower levels of school readiness in the ECEC setting as well as with lower levels of social competence and academic performance in school. A common explanation for such negative associations is that children with externalizing problems may be less well-equipped in terms of social and cognitive maturity, that, in turn, may interfere with their ability to pay attention to school-related tasks as well as responding and acting appropriately in social situations (Metcalfe, Harvey, and Laws Citation2013; Graziano et al. Citation2016). The findings of this present study are consistent with such notions, but also extend previous work by being among the first studies to show longitudinally that the link between early externalizing problems and later social and academic difficulties in school may be due to these children’s (lack of) school readiness. In this sense, the findings are suggestive of a developmental pathway characterized by a sequence of cascading processes whereby problems in the domain of externalizing behaviors early in childhood may initially serve to influence or co-develop with deficits and difficulties in social and cognitive domains, which ultimately may manifest as poor academic achievement and lower social competence in the primary school years. Most importantly, our robust findings across the combination of both mother, ECEC teacher, and primary school teacher ratings indicate that these results are not just the product of a shared reporter bias.

Another important question addressed in this study was whether the quality of the teacher–child relationship in the ECEC setting could alleviate the negative direct and indirect paths described above. Our results partially supported our hypotheses, as we found significant interactions between children’s externalizing problems and teacher–child closeness in the prediction of school readiness in ECEC, but no such effects for the direct association between early externalizing problems and later social and academic adjustment outcomes at age eight. A possible reason for this could be due to the rather extensive time interval between the measurement points. Yet, it is interesting to note that a closer teacher–child relationship not only appeared to buffer the negative direct pathway from early externalizing problems at age three to poor school readiness at age five, but that the benefits of close teacher relationships in ECEC also extended into the school years in terms of alleviating the negative indirect effect from early externalizing problems to social and academic adjustment difficulties in school through poor school readiness in ECEC. These results support previous research findings concerning the benefits of teacher–child closeness for positive adjustment among children with disruptive behaviors (Hamre and Pianta Citation2005; Baker, Grant, and Morlock Citation2008), and extend such knowledge by showing that early positive teacher–child relationships in ECEC could have a lasting influence over time in terms of interrupting the otherwise increased risk that these children may have for negative adjustment (Gutman, Joshi, and Schoon Citation2019; Okano et al. Citation2020; Huber, Plötner, and Schmitz Citation2019).

An important implication of these findings is that the relationship between a child with externalizing problems and her or his ECEC teachers may be a valuable focus for intervention. Several studies on the efficiency of interventions to increase teachers’ closeness with children suggest that training in social-emotional competence may be especially beneficial for children with disruptive behaviors (Baroody et al. Citation2014; Sabol and Pianta Citation2012). For instance, in a study by Spilt et al. (Citation2012), results showed that about half of the ECEC-teachers who received a relationship-focused intervention, including discussions of teachers’ emotional experiences with the children, reported increased closeness to children with externalizing behaviors after the intervention. Accordingly, intervention efforts should be directed towards the aim of increasing warmth and closeness in the teacher–child relationship, as well as towards increasing teachers’ competence and knowledge about disruptive child behaviors and the needs of children with such problems.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

The present study adds to the growing body of research demonstrating that positive teacher–child relationships may serve a protective role for the long-term social and academic adjustment of children with early externalizing problems, even as early as during the ECEC period. A considerable strength of this study is the ability to demonstrate such interaction effects over a five-year period from ages three to eight years, and with sufficient power to detect such effects using latent SEM analyses with bootstrapping that adjust for error variance in the measures, and a large sample size. By using both mother and teacher ratings, we also largely omitted shared method bias.

Despite these advantages, this study also has limitations. First, although the use of longitudinal data strengthens the validity of our findings, the research design was correlational in nature and thereby precludes us from drawing conclusions about causality. Particularly, despite finding interaction effects, we are not able to determine the direction of such effects. Yet, previous research findings are suggestive of a child-driven model in which higher levels of child externalizing problems contribute to less positive teacher–child relationship quality at subsequent measurement points above and beyond stability and concurrent path estimates, but not vice versa (Mejia and Hoglund Citation2016). Second, although we controlled for the potential influence of gender, language difficulties, and socioeconomic status, it is possible that other child or teacher characteristics not included in this study may have contributed to the quality of the teacher–child relationship or to the children’s course of adjustment and development (see Hamre et al. Citation2008). Third, despite the strengths of using a population-based cohort study such as the MoBa, the sample is limited by selection, attrition, and non-response bias. As with most longitudinal studies, this means that our analyses suffered from different numbers of observations for each measurement point as well as from lower response rates in the follow up questionnaires. Furthermore, there is a possibility of self-selection bias as MoBa participants have better health and socioeconomic status compared to Norwegian mothers in general (Nilsen et al. Citation2009). Simulation studies have shown that such self-selection biases could influence predictor-outcome estimates (Biele et al. Citation2019). However, others have concluded that even large selection bias and attrition may have little effect on the estimates of associations between variables in longitudinal cohort studies (Wolke et al. Citation2009; Gustavson, Røysamb, and Borren Citation2019). Due to the overrepresentation of children from high-functioning families in the MoBa sample (Nilsen et al. Citation2009), it is likely that the estimates of associations between the variables in this study are underestimated rather than overestimated. Finally, as our investigation involved Norwegian children, additional research is needed to ascertain the generalizability of the findings among children from other countries and cultural backgrounds.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates the potentially important and positive influence of ECEC teachers for the long-term social and academic adjustment of children with early signs of externalizing behavior problems. The finding that close teacher–child relations in ECEC might interrupt the likelihood that these children continue along a negative developmental pathway is important because they extend knowledge about which factors in the ECEC context that may promote positive social and academic development for children with early behavioral difficulties. Such knowledge is of value for successful implementation of intervention efforts aimed at improving the adjustment and well-being of children as well as enhancing ECEC teachers’ competence about the specific challenges and behaviors that are characteristic of children with different behavioral profiles.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to all the participating families in Norway who take part in this on-going cohort study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data are available for researchers upon request and through application to the MoBa Study. Data codes and syntax are available upon request to the researchers of this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achenbach, T. M. 1992. Manual for the Child Behaviour Checklist/2-3 and 1992 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

- Alexandersen, Nina, Henrik Daae Zachrisson, Tiril Wilhelmsen, Mari Vaage Wang, and Ragnhild Eek Brandlistuen. 2021. “Predicting Selection Into ECEC of Higher Quality in a Universal Context: The Role of Parental Education and Income.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 55: 336–348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.01.001.

- Baker, Jean A., Sycarah Grant, and Larissa Morlock. 2008. “The Teacher-Student Relationship as a Developmental Context for Children with Internalizing or Externalizing Behavior Problems.” School Psychology Quarterly 23 (1): 3–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.3.

- Barkley, Russell A., and Mariellen Fischer. 2011. “Predicting Impairment in Major Life Activities and Occupational Functioning in Hyperactive Children as Adults: Self-Reported Executive Function (EF) Deficits Versus EF Tests.” Developmental Neuropsychology 36 (2): 137–161. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2010.549877.

- Baroody, Alison E., Sara E. Rimm-Kaufman, Ross A. Larsen, and Timothy W. Curby. 2014. “The Link Between Responsive Classroom Training and Student–Teacher Relationship Quality in the Fifth Grade: A Study of Fidelity of Implementation.” School Psychology Review 43 (1): 69–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2014.12087455.

- Biele, Guido, Kristin Gustavson, Nikolai Olavi Czajkowski, Roy Miodini Nilsen, Ted Reichborn-Kjennerud, Per Minor Magnus, Camilla Stoltenberg, and Heidi Aase. 2019. “Bias from Self Selection and Loss to Follow-up in Prospective Cohort Studies.” European Journal of Epidemiology 34 (10): 927–938. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00550-1.

- Bierman, Karen L., John Coie, Kenneth Dodge, Mark Greenberg, John Lochman, Robert McMohan, Ellen Pinderhughes, and Group Conduct Problems Prevention Research. 2013. “School Outcomes of Aggressive-Disruptive Children: Prediction from Kindergarten Risk Factors and Impact of the Fast Track Prevention Program.” Aggressive Behavior 39 (2):114-130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21467.

- Birch, Sondra H., and Gary W. Ladd. 1997. “The Teacher-Child Relationship and Children's Early School Adjustment.” Journal of School Psychology 35 (1): 61–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(96)00029-5.

- Blair, C. 2002. “School Readiness: Integrating Cognition and Emotion in a Neurobiological Conceptualization of Children's Functioning at School Entry.” American Psychologist 57 (2): 111–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.2.111.

- Bornstein, M. H., Chun-Shin Hahn, and O. Maurice Haynes. 2010. “Social Competence, Externalizing, and Internalizing Behavioral Adjustment from Early Childhood Through Early Adolescence: Developmental Cascades.” Development and Psychopathology 22 (4): 717–735. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000416.

- Bornstein, M. H., Chun-Shin Hahn, and Joan T. D. Suwalsky. 2013. “Developmental Pathways among Adaptive Functioning and Externalizing and Internalizing Behavioral Problems: Cascades from Childhood Into Adolescence.” Applied Developmental Science 17 (2): 76–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2013.774875.

- Brandlistuen, Ragnhild E., Martin Flatø, Camilla Stoltenberg, Siri S. Helland, and Mari V. Wang. 2020. “Gender Gaps in Preschool Age: A Study of Behavior, Neurodevelopment and Pre-academic Skills.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494820944740.

- Burchinal, Margaret R., Ellen Peisner-Feinberg, R. C. Pianta, and Carollee Howes. 2002. “Development of Academic Skills from Preschool Through Second Grade: Family and Classroom Predictors of Developmental Trajectories.” Journal of School Psychology 40 (5): 415–436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(02)00107-3.

- Burt, Keith B., and Glenn I. Roisman. 2010. “Competence and Psychopathology: Cascade Effects in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development.” Development and Psychopathology 22 (3): 557–567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000271.

- Chen, X., K. H. Rubin, and D. Li. 1997. “Relation Between Academic Achievement and Social Adjustment: Evidence from Chinese Children.” Developmental Psychology 33 (3): 518. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.3.518.

- Denham, Susanne A. 2006. “Social-emotional Competence as Support for School Readiness: What is it and how do we Assess it?” Early Education and Development 17 (1): 57–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1701_4.

- Doctoroff, Greta L., Joseph A. Greer, and David H. Arnold. 2006. “The Relationship Between Social Behavior and Emergent Literacy among Preschool Boys and Girls.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 27 (1): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2005.12.003.

- Graziano, Paulo A., Leanna R. Garb, Rosmary Ros, Katie Hart, and Alexis Garcia. 2016. “Executive Functioning and School Readiness among Preschoolers with Externalizing Problems: The Moderating Role of the Student–Teacher Relationship.” Early Education and Development 27 (5): 573–589. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1102019.

- Green, V. A., and R. Rechis. 2006. “Children's Cooperative and Competitive Interactions in Limited Resource Situations: A Literature Review.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 27 (1): 42–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2005.12.002.

- Gresham, F. M., and S. N. Elliott. 2008. Social Skills Improvement System: Rating Scales Manual.” NCS Pearson.

- Gresham, Frank M., Stephen N. Elliott, Michael J. Vance, and Clayton R. Cook. 2011. “Comparability of the Social Skills Rating System to the Social Skills Improvement System: Content and Psychometric Comparisons Across Elementary and Secondary Age Levels.” School Psychology Quarterly 26 (1): 27–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022662.

- Guhn, Martin, Anne M. Gadermann, Alisa Almas, Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, and Clyde Hertzman. 2016. “Associations of Teacher-Rated Social, Emotional, and Cognitive Development in Kindergarten to Self-Reported Wellbeing, Peer Relations, and Academic Test Scores in Middle Childhood.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 35: 76–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.12.027.

- Gustavson, Kristin, Espen Røysamb, and Ingrid Borren. 2019. “Preventing Bias from Selective non-Response in Population-Based Survey Studies: Findings from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 19 (1): 120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0757-1.

- Gutman, Leslie Morrison, Heather Joshi, and Ingrid Schoon. 2019. “Developmental Trajectories of Conduct Problems and Cumulative Risk from Early Childhood to Adolescence.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 48 (2): 181–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0971-x.

- Hamre, B. K., and R. C. Pianta. 2001. “Early Teacher–Child Relationships and the Trajectory of Children's School Outcomes Through Eighth Grade.” Child Devevlopment 72 (2): 625–638. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00301.

- Hamre, B. K., and R. C. Pianta. 2005. “Can Instructional and Emotional Support in the First-Grade Classroom Make a Difference for Children at Risk of School Failure?” Child Development 76 (5): 949–967. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x.

- Hamre, B. K., R. C. Pianta, J. T. Downer, and A. J. Mashburn. 2008. “Teachers’ Perceptions of Conflict with Young Students: Looking Beyond Problem Behaviors.” Social Development 17 (1): 115–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00418.x.

- Hay, D. F., and S. J. Pawlby. 2003. “Prosocial Development in Relation to Children's and Mothers’ Psychological Problems.” Child Development 74 (5): 1314–1327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00609.

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2015. “An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 50 (1): 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683.

- Hayes, A. F., and K. J. Preacher. 2013. “Conditional Process Modeling: Using Structural Equation Modeling to Examine Contingent Causal Processes.” In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course. Vol. 2, edited by G. R. Hancock and R. O. Mueller, 217–264. Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

- Henricsson, Lisbeth, and Ann-Margret Rydell. 2004. “Elementary School Children with Behavior Problems: Teacher-Child Relations and Self-Perception. A Prospective Study.” Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 50 (2): 111–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2004.0012.

- Hinshaw, S. P., S. S. Han, D. Erhardt, and A. Huber. 1992. “Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems in Preschool Children: Correspondence among Parent and Teacher Ratings and Behavior Observations.” Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 21 (2): 143–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2102_6.

- Howes, Carollee. 2000. “Social-emotional Classroom Climate in Child Care, Child-Teacher Relationships and Children’s Second Grade Peer Relations.” Social Development 9 (2): 191–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00119.

- Hu, Li‐tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6 (1): 1–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Huber, L., M. Plötner, and J. Schmitz. 2019. “Social Competence and Psychopathology in Early Childhood: a Systematic Review.” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 28 (4): 443–459. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1152-x.

- Irgens, L. M. 2000. “The Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Epidemiological Research and Surveillance Throughout 30 Years.” Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 79 (6): 435–439.

- Janus, Magdalena, and Dan Offord. 2000. “Readiness to Learn at School.” Canadian Journal of Policy Research 1 (2): 71–75.

- Justice, Laura M., Ryan P. Bowles, Khara L. Pence Turnbull, and Lori E. Skibbe. 2009. “School Readiness among Children with Varying Histories of Language Difficulties.” Developmental Psychology 45 (2): 460–476. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014324.

- Kjeldsen, A., W. Nilsen, K. Gustavson, A. Skipstein, O. Melkevik, and E. B. Karevold. 2016. “Predicting Well-Being and Internalizing Symptoms in Late Adolescence from Trajectories of Externalizing Behavior Starting in Infancy.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 26 (4): 991–1008. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12252.

- Klein, Andreas, and Helfried Moosbrugger. 2000. “Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Latent Interaction Effects with the LMS Method.” Psychometrika 65 (4): 457–474. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296338.

- Kouros, Chrystyna D., E. Mark Cummings, and Patrick T. Davies. 2010. “Early Trajectories of Interparental Conflict and Externalizing Problems as Predictors of Social Competence in Preadolescence.” Development and Psychopathology 22 (3): 527–537. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000258.

- Kulkarni, T., A. Sullivan, and J. Kim. 2020. “Externalizing Behavior and Academic Achievement: Do Causal Relations Exist?” PsyArXiv. doi:https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xrv8y.

- La Paro, Karen M., and R. C. Pianta. 2000. “Predicting Children's Competence in the Early School Years: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Review of Educational Research 70 (4): 443–484. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070004443.

- Little, Todd D. 2013. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling. London: The Guilford Press.

- Lodder, Paul, Johan Denollet, Wilco H. M. Emons, Giesje Nefs, Frans Pouwer, Jane Speight, and Jelte M. Wicherts. 2019. “Modeling Interactions Between Latent Variables in Research on Type D Personality: A Monte Carlo Simulation and Clinical Study of Depression and Anxiety.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 54 (5): 637–665. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2018.1562863.

- Magnus, Per, Charlotte Birke, Kristine Vejrup, Anita Haugan, Elin Alsaker, Anne Kjersti Daltveit, Marte Handal, et al. 2016. “Cohort Profile Update: The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa).” International Journal of Epidemiology 45 (2): 382–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw029.

- Mantzicopoulos, Panayota. 2005. “Conflictual Relationships Between Kindergarten Children and Their Teachers: Associations with Child and Classroom Context Variables.” Journal of School Psychology 43 (5): 425–442. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.09.004.

- Masten, A. S., K. B. Burt, and J. D. Coatsworth. 2006. “Competence and Psychopathology in Development.” In Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation, edited by D. Cicchetti and D. J. Cohen, Vol. 3, 2nd ed., 696–738. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Masten, A. S., and D. Cicchetti. 2010. “Developmental Cascades.” Development and Psychopathology 22 (3): 491–495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000222.

- Masten, A. S., G. I. Roisman, J. D. Long, K. B. Burt, J. Obradović, J. R. Riley, K. Boelcke-Stennes, and A. Tellegen. 2005. “Developmental Cascades: Linking Academic Achievement and Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms Over 20 Years.” Developmental Psychology 41 (5): 733–746. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733.

- Mejia, Teresa M., and Wendy L. G. Hoglund. 2016. “Do Children's Adjustment Problems Contribute to Teacher–Child Relationship Quality? Support for a Child-Driven Model.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 34: 13–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.08.003.

- Metcalfe, Lindsay A., Elizabeth A. Harvey, and Holly B. Laws. 2013. “The Longitudinal Relation Between Academic/Cognitive Skills and Externalizing Behavior Problems in Preschool Children.” Journal of Educational Psychology 105 (3): 881–894. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032624.

- Moffitt, T. E., L. Arseneault, D. W. Belsky, N. Dickson, R. J. Hancox, H. L. Harrington, R. M. Houts, et al. 2011. “A Gradient of Childhood Self-Control Predicts Health, Wealth, and Public Safety.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (7): 2693–2698. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010076108.

- Moilanen, Kristin L., Daniel S. Shaw, and Kari L. Maxwell. 2010. “Developmental Cascades: Externalizing, Internalizing, and Academic Competence from Middle Childhood to Early Adolescence.” Development and Psychopathology 22 (3): 635–653. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000337.

- Muthen, L., and B. Muthen. 2017. MPlus User's Guide. Eight Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen and Muthen.

- Myers, Sonya S., and R. C. Pianta. 2008. “Developmental Commentary: Individual and Contextual Influences on Student–Teacher Relationships and Children's Early Problem Behaviors.” Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 37 (3): 600–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802148160.

- Nakamura, Brad J., Chad Ebesutani, Adam Bernstein, and Bruce F. Chorpita. 2009. “A Psychometric Analysis of the Child Behavior Checklist DSM-Oriented Scales.” Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 31 (3): 178–189. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-008-9119-8.

- Nilsen, R. M., S. E. Vollset, H. K. Gjessing, R. Skjaerven, K. K. Melve, and P. Schreuder. 2009. “Self-selection and Bias in a Large Prospective Pregnancy Cohort in Norway.” Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 23 (6): 597–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01062.x.

- Nix, Robert L., Karen L. Bierman, Celene E. Domitrovich, and Sukhdeep Gill. 2013. “Promoting Children's Social-Emotional Skills in Preschool Can Enhance Academic and Behavioral Functioning in Kindergarten: Findings from Head Start REDI.” Early Education and Development 24 (7): 1000–1019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2013.825565.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2017. “The Framework Plan for Kindergartens.” Norway.

- Okano, L., L. Jeon, A. Crandall, T. Powell, and A. Riley. 2020. “The Cascading Effects of Externalizing Behaviors and Academic Achievement Across Developmental Transitions: Implications for Prevention and Intervention.” Prevention Science 21 (2): 211–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-01055-9.

- Ottem, E. 2009. “Spørsmål om Språkferdigheter: En Analyse av Sammenhengen Mellom Observasjonsdata og Testdata.” Skolepsykologi 1: 11–27.

- Pentimonti, Jill M., Kimberly A. Murphy, Laura M. Justice, Jessica A. R. Logan, and Joan N. Kaderavek. 2016. “School Readiness of Children with Language Impairment: Predicting Literacy Skills from pre-Literacy and Social–Behavioural Dimensions.” International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 51 (2): 148–161. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12193.

- Pianta, R. C. 2001. Student-Teacher Relationship Scale: Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

- Prior, M., A. Sanson, D. Smart, and F. Oberklaid. 2000. Pathways from Infancy to Adolecence: Australian Temperament Project, 1983–2000.

- Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., R. C. Pianta, and M. J. Cox. 2000. “Teachers’ Judgments of Problems in the Transition to Kindergarten.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 15 (2): 147–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(00)00049-1.

- Sabol, T. J., and R. C. Pianta. 2012. “Recent Trends in Research on Teacher–Child Relationships.” Attachment & Human Development 14 (3): 213–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.672262.

- Sameroff, A. J. 2009. The Transactional Model of Development: How Children and Contexts Shape Each Other. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Serbin, Lisa A., Danielle Kingdon, Paula L. Ruttle, and Dale M. Stack. 2015. “The Impact of Children's Internalizing and Externalizing Problems on Parenting: Transactional Processes and Reciprocal Change Over Time.” Development and Psychopathology 27 (4pt1): 969–986. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579415000632.

- Solheim, Elisabet, Turid Suzanne Berg-Nielsen, and Lars Wichstrøm. 2012. “The Three Dimensions of the Student–Teacher Relationship Scale.” Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 30 (3): 250–263. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282911423356.

- Spengler, M., R. I. Damian, and B. W. Roberts. 2018. “How you Behave in School Predicts Life Success Above and Beyond Family Background, Broad Traits, and Cognitive Ability.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 114 (4): 620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000185.

- Spilt, Jantine L., Helma M. Y. Koomen, Jochem T. Thijs, and Aryan van der Leij. 2012. “Supporting Teachers’ Relationships with Disruptive Children: the Potential of Relationship-Focused Reflection.” Attachment & Human Development 14 (3): 305–318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.672286.

- Statistics Norway. 2020. “Kindergartens.” Accessed February 8, 2020. https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/statistikker/barnehager.

- Trentacosta, Christopher J., and Daniel S. Shaw. 2009. “Emotional Self-Regulation, Peer Rejection, and Antisocial Behavior: Developmental Associations from Early Childhood to Early Adolescence.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 30 (3): 356–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.016.

- Vasileva, Mira, Ramona K. Graf, Tilman Reinelt, Ulrike Petermann, and Franz Petermann. 2021. “Research Review: A Meta-Analysis of the International Prevalence and Comorbidity of Mental Disorders in Children Between 1 and 7 Years.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 372–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13261.

- Wang, Mari Vaage, Leif Edvard Aarø, and Eivind Ystrom. 2018. “Language Delay and Externalizing Problems in Preschool age: A Prospective Cohort Study.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 46 (5): 923–933. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0391-5.

- Wilhelmsen, Tiril, Ratib Lekhal, Nina Alexandersen, Ragnhild E. Brandlistuen, and Mari V. Wang. 2021. “Children’s Temperament Moderates the Long-Term Effects of Pedagogical Practices in ECEC on Children’s Externalising Problems.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29 (2): 206–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.1895273.

- Wolke, Dieter, Andrea Waylen, Muthanna Samara, Colin Steer, Robert Goodman, Tamsin Ford, and Koen Lamberts. 2009. “Selective Drop-out in Longitudinal Studies and non-Biased Prediction of Behaviour Disorders.” British Journal of Psychiatry 195 (3): 249–256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053751.

- Zadeh, Zohreh Yaghoub, Nancie Im-Bolter, and Nancy J. Cohen. 2007. “Social Cognition and Externalizing Psychopathology: An Investigation of the Mediating Role of Language.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 35 (2): 141–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9052-9.

- Zhang, Xiao, and Jari-Erik Nurmi. 2012. “Teacher–Child Relationships and Social Competence: A two-Year Longitudinal Study of Chinese Preschoolers.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 33 (3): 125–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2012.03.001.