ABSTRACT

This qualitative study explored Norwegian ECEC professionals’ perceptions and reflections concerning the use of the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) Pre-K and Toddler for professional development. Focus group interviews (n = 22), group interviews (n = 4), and in-depth interviews (n = 3) were conducted online. Conventional content analysis was performed using NVivo 12 software. The professionals reported that CLASS contributed to positive structures for professional community and development within which both individual and collective learning occurred. The content analysis yielded four main categories: A shared professional platform, Professionalisation, Quality in practice and Outcomes for children and parents. The CLASS structure improved communication and collaboration between the early childhood education and care (ECEC) centres and support systems. Overall, the findings contribute to new knowledge on how ECEC professionals experience CLASS as a tool for professional development, sense of community, improved collaboration and more thoughtful classroom practice.

Introduction

The global research community in early childhood education and care (ECEC) emphasises the importance of high-quality education in ensuring safe, playful and stimulating learning environments for all young children. Several quality rating systems for ECEC exist, among which the Classroom Environment Scoring System (CLASS) is particularly popular (La Paro, Hamre, and Pianta Citation2012). Norway offers subsidised day care in regulated ECEC centres to all children aged 1–5 years. Norwegian ECEC centres are often considered to be among the best worldwide by virtue of their broad accessibility and their adherence to the Framework Plan (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2017), which focuses on holistic development through care, play and learning. Nonetheless, the varying quality of available ECEC facilities continues to pose a challenge for Norway’s ECEC system (Alvestad et al. Citation2019; Bjørnestad and Os Citation2018; Lekhal, Wang, and Schjølberg Citation2013; Rege et al. Citation2018).

The OECD (Citation2019) encourages ECEC providers to adopt a systematic approach to data collection on process quality to facilitate subsequent quality development in local settings (OECD Citation2019). This entails motivation to search for tools to simultaneously assess interaction quality systematically and give staff an opportunity for tailored guidance and individual development. CLASS has been used to measure process quality and provide staff with adapted guidance in selected Norwegian ECEC centres to ensure children's optimal development. However, the feasibility and appropriateness of using CLASS in Norway has not yet been fully assessed. This study explored Norwegian ECEC professionals’ perceptions of the use of CLASS for professional development.

Despite the large body of quantitative research studying the associations between various aspects of CLASS and the outcomes for children (Burchinal et al. Citation2008; Howes et al. Citation2008; Mashburn et al. Citation2008), qualitative analyses of teachers’ experiences of CLASS as practitioners are lacking. In this paper, we complement the existing literature with data from interviews with teachers and ECEC professionals to document users’ experiences of CLASS with respect to observation, feedback and professional development. In-depth knowledge of teachers’ perspectives is critical to promoting the high-quality effective implementation of CLASS in daily ECEC provision. A qualitative approach can provide knowledge and insights into whether the profession perceives the CLASS system as a meaningful tool to promote professional development, from the perspectives of both the observers and the observed staff who receive guidance based on CLASS scores.

Sociocultural learning theory

This study is underpinned by sociocultural learning theory (Vygotsky Citation1980), which suggests that people develop through interaction with their surrounding environments, in dialogue with one another using sociocultural tools that mediate these interactions (Vygotsky Citation2001). The sociocultural perspective views learning and development as processes that take place through the use of language and participation in social practices (Säljö Citation2001). This sociocultural view of learning permeates the Norwegian ECEC system and its Framework Plan (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2017) and, as such, guided our study design.

ECEC quality

In Norway, 92.8% of children attend an ECEC facility (SSB Citation2021). As part of the welfare state, ECEC is intended to provide a foundation for enhancing life skills and health (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2017). To achieve this goal, however, ECEC staff must engage in high-quality interactions with each child in their settings (Burchinal et al. Citation2008; Cadima et al. Citation2020; Dalli et al. Citation2011; Evertsen et al. Citation2015; Moser et al. Citation2017; Pianta et al. Citation2003). Although the concept of quality in ECEC may be difficult to define and might depend on an individual’s subjective perception (Sheridan Citation2001), the literature shows consensus that high-quality interactions between children and adults pave the way for healthy child development (Shonkoff Citation2010; Siegel Citation2020). We conceptualise high quality in terms of approaches that are beneficial for children’s development and well-being (Engvik et al. Citation2014; Melhuish Citation2011) and that have a substantial positive impact on children’s early learning (Rege et al. Citation2019; Yoshikawa et al. Citation2013) as well as long-term outcomes, such as literacy and numeracy (Melhuish Citation2011).

Individual and collective learning in ECEC organisations

To achieve high-quality practice in ECEC, staff must participate in a professional development learning community (Roland and Ertesvåg Citation2018). Learning is most fruitful when staff collaborate in continuous learning processes over extended periods and when professional staff develop a shared approach to their daily practice (Fullan Citation2014). It follows that systems may change significantly when learning becomes collective (Flaspohler et al., Citation2008; Senge Citation1999), and when all staff develop and learn new approaches together with the aim of delivering high-quality pedagogical services (Flaspohler et al. Citation2008). Developing knowledge in an organisation is closely linked to sharing and community, which requires a common professional language (Stålsett Citation2006). Human interaction can be understood as taking place in the language, and that common professional language is thus an essential source for the development of a professional community (Skjervheim Citation1996). This typically ensues when staff develop a ‘tribal language’ of common concepts and theories that they actively use in their daily work. To achieve this, centre leaders must initiate change processes in which staff learn together and continuously reflect on their pedagogical approaches (Dufour Citation2016) and that support them in connecting theoretical perspectives with their daily practice (Roland and Ertesvåg Citation2018).

Capacity can be defined as ‘the skills, motivations, knowledge, and attitudes necessary to implement innovations, which exist at the individual, organisation, and community levels’ (Wandersman et al. Citation2008), and it encompasses the power to engage in and sustain change processes for the purpose of enhancing learning for all (Stoll Citation2010). Capacity must be developed both individually and collectively among staff, indicating that all staff acquire new knowledge, gain new resources and seek new motivation (Flaspohler et al. Citation2008; Wandersman et al. Citation2008).

CLASS as a system for individual and collective learning in Norwegian ECEC

The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) (Pianta et al., Citation2008) is a validated observation instrument. Based on the empirical importance of high-quality environments for children, CLASS was developed as an observational instrument, designed to assess classroom processes. The CLASS scales were constructed based on a review of literature on teacher education, quality in ECEC, and observational research focusing on classroom dimensions that relate to child outcomes (La Paro et al. Citation2004). The instrument is based on the theoretical framework of Teaching Through Interactions (TTI) which is anchored in systems theory (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979), closely compatible with sociocultural learning theory where human interaction is the most important component for children's development and growth (Hamre et al. Citation2014; Hamre and Pianta Citation2007).

The main goal of the observational instrument is to assess interaction between children and adults (Pianta et al. Citation2013). CLASS Toddler (18–36 months) consists of eight dimensions organised into two domains (Emotional and Behavioural Support, and Engaged Support for Learning) (La Paro et al. Citation2012). CLASS Pre-K (3–5 years) comprises ten dimensions organised into three domains (Instructional Support, Classroom Organisation, and Emotional Support) (Pianta et al. Citation2013). Observations are scored on a seven-point scale: scores 1 and 2 indicate low quality; 3, 4 and 5 represent medium quality; and 6 and 7 denote high quality. An average score is calculated for each domain based on the scores on the dimensions belonging to the domain.

A Norwegian West Coast municipality used CLASS to gather observations and to give feedback with a view to strengthening their ECEC centre’s quality prior to this study’s commencement. To date, 62 centres have participated, together with the ECEC support services, including the Pedagogical-Psychological Service (PPS), the ECEC Resource Centre (which can be called on for extra support), the Centre for Multilingual Children and the municipality ECEC administration. ECEC staff have participated either by being observed or by observing other practitioners’ using CLASS. The initiative consisted of various training elements, such as lecture days, certification of observers, local guidance and network group discussions. A total of 24 staff from ECEC centres and support services completed the CLASS certification and were thus ready to observe centres. Observation with CLASS provided the basis for a CLASS report, and the centres thus received individual and system-level guidance. This municipality's implementation of CLASS as a system for professional development allowed us to explore the participants’ own perceptions, experiences and reflections regarding CLASS—from the perspectives of both the observers and the staff who were observed and received guidance. Our explorations were guided by the following research question: What are the perceptions and reflections of education professionals regarding CLASS as a system for individual and collective learning in Norwegian ECEC?

Method

Owing to the lack of empirical research on professional educational experiences with CLASS, a qualitative, explorative research design was selected. The COVID-19 pandemic prompted researchers to engage with new data collection methods (Kucirkova et al. Citation2020). For our team, it meant adapting analogue interviews to online interviews. Online focus groups, group interviews and individual interviews were considered appropriate as they can generate a rich understanding of participants’ experiences with new interventions or systems (Krueger and Casey Citation2015; Morgan Citation1993) and because they generate collective understandings of the phenomenon under study (Lune and Berg Citation2017).

Participants

Invitation to participate in the study was distributed through the municipality’s email system, but participants’ consent to participate was submitted directly to the University of Stavanger document control department, so that the municipality’s ECEC management was not privy to the final participant list. All staff who had worked with CLASS for four to five years in the municipality’s ECEC centres and all certified CLASS observers were invited to participate. This resulted in 196 ECEC professionals being invited to attend. Among these, 29 ECEC professionals signed up for the study. This procedure was chosen because, at that time, only this municipality in Norway had the experience of implementing CLASS in all parts of the ECEC system. Considering that the ECEC employees were invited during a situation with many restrictions caused by COVID 19, we invited everyone who met the inclusion criteria and included all those who were willing to participate.

The participants represented PPS, the Resource Centre, the Centre for Multilingual Children, municipality ECEC administration, and teachers and assistants in ECEC centres. All participants were female and came from nine different ECEC centres and four different sectors of the support system. To ensure that the number of participants in the focus group interviews was sufficient to facilitate meaningful analysis (Krueger and Casey Citation2015), all staff who returned the consent forms were invited to participate. Four focus group interviews (n = 22), two smaller group interviews (n = 4), and three individual interviews (n = 3)—all online—were conducted (total n = 29). Initially, we had intended to conduct 4–6 focus group interviews that included all participants. However, owing to some participants’ sick leave requirements and scheduling issues, we set up new group and individual interviews to avoid high attrition rates.

Data collection and procedure

An open-ended, semi-structured interview guide was developed based on pilot interviews. The interview guides were piloted in three rounds, with an ECEC leader, teacher, and assistant. During the pilot interview, some time had been set aside for the informants to give feedback on which questions worked well and which needed improvement, and this feedback informed adjustments to the interview guide. The interview guide varied slightly between those who had used CLASS to observe others and those who had been observed and received feedback through CLASS (see Appendix). The main themes concerned the professionals’ experiences of and reflections on CLASS in the Norwegian ECEC context. Extended focus group interviews were held (Berg et al. Citation2004), which included introducing the interviews’ main topics to participants before the interviews took place. This allowed participants to reflect on their personal opinions before the interview, thus increasing the likelihood that they would express their opinions more fully during the focus group interview (Breen Citation2006). The main author and a moderator assistant conducted the interviews online based on focus group interview guidelines (Krueger and Casey Citation2015). Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 min and was audio-recorded and transcribed by the main author who was leading the interviews.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD), and all ethical recommendations were adhered to throughout. Participants were informed that they could withdraw at any time without giving a reason, and all quotes are anonymized. Practical and ethical reflections on digital data collection in this study are partly presented in Kucirkova et al. (Citation2020). In addition, to study the digital interview process closely, we added questions in the interview guide focusing on participants’ experiences of the digital focus group interviews (Evertsen et al., forthcoming).

Data analysis

The main author initiated the analytical process by closely reading the transcripts several times to compile the first draft of initial themes (Harding Citation2018). The second co-author then refined the themes and their interconnectedness in discussion with the first author. To validate the findings, the third author read through the raw data separately and discussed the final analyses and agreement of key themes with the other two authors.

The analysis was conducted in three stages. The first stage involved the establishment of codes, followed by themes and finally high-level categories that emerged from the data using inductive category development (Mayring Citation2000). A conventional content analysis was performed (Fauskanger and Mosvold Citation2014; Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005) using NVivo 12 software. The focus of the analysis was on the qualitative saturation of meaning rather than the quantification of utterances. On occasions when the findings from the focus groups concurred with each other, the data were categorised within the same dimensions and narrowed down to categories and subcategories (Patton Citation2002). In cases of disagreement, the researchers discussed the findings again, searched for relevant quotes and agreed on the final categories.

All interviews were first analysed individually. All interviews from all groups were then analysed cross-sectionally. After the cross-sectional analyses, two overarching topics emerged: (1) ECEC professionals’ experiences with CLASS as a framework for professional development (presented in this article), and (2) participants’ reflections on the use of CLASS in Norwegian ECEC (will be published elsewhere, Evertsen et al., in process). The researchers also performed a member check (Miles et al. Citation2020) via email, which gave the informants the opportunity to provide feedback on the initial analyses. None of the participants indicated any disagreements or need for change.

Findings

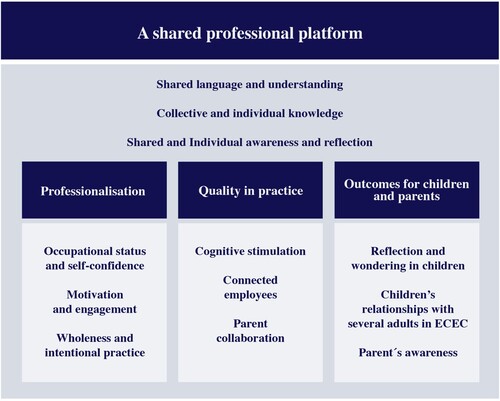

The content analysis yielded four main high-level categories: A shared professional platform, Professionalisation, Quality in practice and Outcomes for children and parents. Each main category includes three subcategories (themes). The category A shared professional platform was deemed to constitute a foundation for the other three categories and was therefore chosen as the dominant category.

visualises the findings to provide an at-a-glance overview of the main categories (Miles et al. Citation2020). To strengthen the findings’ trustworthiness, all quotes from the interviews have been translated so as to reflect the original Norwegian content as accurately as possible (Helmich et al. Citation2017). To preserve participants’ anonymity, numbers are used to represent the interview to which each respective participant belongs.

Discussion

This study’s main aim was to explore education professionals’ perceptions and reflections concerning CLASS as a system for individual and collective learning in Norwegian ECEC. The overall findings suggest that the ECEC professionals interviewed believed that CLASS contributes to positive structures that support professional community and development.

A shared professional platform

Participants perceived CLASS as a system that provided them with a professional development community. This category is interpreted as a foundation for the other categories, since the CLASS structure provided staff with a shared professional platform that included a common language and collective knowledge, which, in turn, led to professionalisation in terms of a shared community both within centres and between centres and the support system, improved quality in practice and positive outcomes for parents and children. Participant 1.4 expressed her experiences as ‘ … a common knowledge for all (…) we all go in the same direction’.

The results suggest that the introduction of CLASS stimulated a common pedagogical language and understanding. Participant 5.1 said, ‘What I believe works best (…) is that we get a common language, that we have the same concepts in ECEC centres and as support systems.’ This resembles what Dufour (Citation2016) refers to as a ‘tribal language’ of common concepts and theories that staff actively use in their daily work. The findings further suggest that the new knowledge and the common professional language raised awareness of and prompted reflection on pedagogical actions among participants. When collective learning occurs in ECEC organisations, staff develop a shared understanding (intersubjectivity) in their daily practice (Roland and Ertesvåg Citation2018). The tribal language (Dufour Citation2016) affords the opportunity to develop a common focus and awareness and can be understood as part of the precondition for learning that extends from the individual to the collective. Individual learning can instigate change, but significant system-level changes occur when learning becomes collective (Fullan Citation2014). As Participant 5.7 said,

What I think is very positive about using CLASS is that all kindergartens in the municipalities (…) work with the same thing and have a shared platform … it is not the case that every centre sits alone and does its own thing but that we have found something that we know is good for children's development. Using CLASS as a foundation is a strength. And it’s good for me from the support system who guides and gives courses in centres and can link what I’m talking about to CLASS, because then the ECEC staff know what I'm talking about.

Participant 1.2 reflected, ‘I believe that common language is the key (…) to getting everyone involved.’ It was clear from the participants’ reflections that developing capacity was about gaining new knowledge and seeking fresh motivation, which, in turn, contributed to greater professional commitment. Research suggests that in such situations, staff can experience positive change in an upward spiral, both individually and collectively (Flaspohler et al., Citation2008; Meyers et al., Citation2012; Wandersman et al., Citation2008).

Professionalisation

This category captured participants’ responses that were characterised by motivation, commitment and the experience of an improved and holistic collaboration between ECEC and its support system. Several ECEC teachers remarked that CLASS had elevated their status as staff in ECEC. As Participant 4.2 observed, ‘I absolutely think it helps to improve the quality of kindergartens and that this raises our profession … In a way, it helps to get rid of the attitude that anyone can work in ECEC. The extent of our work, I think CLASS is helping to bring out.’ Participant 1.4 confirmed the importance of professional competence in ECEC: ‘ECEC is not the same now as it was many years ago. There is much more quality in the work than some might think. So, it raises the quality, and does something with the status of the ECEC.’ Participant 1.1 observed, ‘Because our profession is a low-status profession, and we are constantly fighting to show the world all the good things we do … and I think this has helped us … Because it’s getting more professional.’

The introduction of CLASS offered participants the opportunity to communicate with the outside world within which they practice pedagogy and education in ECEC centres in a way that is similar to yet different from how teachers in schools practice. Participant 9.1 remarked, ‘We are teachers like them (ref to teachers in school), except that we have a different approach.’

Several ECEC staff expressed that being observed and receiving feedback renewed their awareness of pedagogical practices, leading to enhanced motivation and commitment and increased self-confidence. Participant 1.3 said, ‘It is motivating to receive feedback, and then you usually get a lot of positive feedback. Then you also get feedback that will make you develop, and that gives motivation … so there is a lot here that is motivating for the individual and the team.’ The participants noted that CLASS and its common language raised the quality of their collaboration. Coaching and guidance tend to be of higher quality when all involved use the same language and understand one another as a single community. Participant 8.1 noted, ‘I can use it both for guidance in the ECEC group and for writing reports … . can use some of the words in CLASS and then people know what I mean.’

A shared experience reported by participants was that as part of their increased sense of professionalisation, they planned their educational activities more thoughtfully and intentionally. The activities were constructed to provide learning opportunities, although they continued to focus on the children’s learning process. Here, the intention or purpose of their profession was essential: ‘We have become very intentional in our pedagogical approach. What is the purpose? What do we want children to experience and learn?’ (Participant 4.1).

Quality in practice

Participants reported that with the use of CLASS, the quality of their pedagogical approaches has improved: ‘ … the staff focus on how they work. And that is what develops the quality, I think … ’ (Participant 1.3).

In line with one of the main domains in CLASS—instructional support—ECEC staff focus on stimulating children’s cognitive development during play and daily activities. Participant 4.5 observed, ‘ … It's about giving the children a chance to talk, both to speak and think for themselves.’ The participants experienced improvements in their stimulation of children’s language and reflective conversations and in the quality of interaction between each staff and child. As Participant 4.4 put it, ‘Actually, start asking those (reflective) questions when they are young, so that they get used to that way of thinking’ The practitioners wanted to stimulate children’s sense of wonder, and in the interviews, they reflected on CLASS’s contribution to this professional intention: ‘CLASS has certainly helped to … raise that understanding … In the past, when we have had circle time, we have preferred to just teach, and the children became passive … Now there is more focus on interactive sessions.’ (Participant 9.1); ‘CLASS has helped with this. You become more aware that you are not at home; you are at work. You must use words; you must use language.’ (Participant 3.2).

Participants reported that to ensure high-quality interactions, they had become more aware of children’s signals and needs. Participant 9.1 revealed, ‘It's quite clear. There are so many who have become professional, solid, and safe staff … ’ Responsive teaching of this nature is in line with what the literature describes as foundational for child development and well-being (Shonkoff Citation2010; Siegel Citation2020). ECEC centre staff reported that they provided more guidance to parents than before, attributing this to a new sense of security in their roles, achieved through new knowledge, motivation and self-confidence as part of a professional ECEC community. Participant 1.4 reflected on how they had chosen to communicate the CLASS dimensions to parents: ‘ … we have chosen to inform the parents about which dimension we focus on. Information about what the dimension contains, and how we work, may also help the parents … So, it is to raise awareness among parents too … There has been a lot of positive feedback from parents.’ Our findings further indicated that the individual and collective learning achieved through CLASS has, from the participants’ subjective perspectives, enabled them to deliver high-quality pedagogy to children and to engage in a richer and more meaningful dialogue with parents.

Outcomes for children and parents

Participants in this study reported that CLASS has contributed to changes in their practice. Participant 2.1 said, ‘The children are more involved in everyday life than they were before. The staff are better at engaging children. They ask in a different way. They are more present.’ The participants reported that the children reflected at a higher level than before after the CLASS system was introduced. In Participant 2.1’s experience, children were very responsive and engaged during a visit from a storyteller: ‘Then I thought: Oh yes, it works in real life too, it's not just the staff who change, but we see it in the kids too!’ This may relate to the previous categories, which revealed the professionals’ enhanced awareness of children’s language stimulation and cognitive expansion through adult–child conversation. The participants also reported that several children sought different adults for security, comfort and confirmation. Participant 2.1 noted, ‘ … now the children approach all the adults in the group’. This reflects the influence of a shared community among adults on the children in their classes.

A central dimension in CLASS is emotional support; thus, CLASS guides teachers towards sensitive and supportive practices. Results indicate that children related to more adults as their safe caregivers and that the staff also observed improved parent collaboration. Teachers were more confident than before both in their pedagogical roles and in guiding parents. Parents listened more attentively to their professional advice, which could potentially further enhance child development. Participant 1.4 said, ‘They (parents) get examples of things they can also use and do at home … It raises parental awareness a bit too. And that's what they say themselves, that they become a little more conscious themselves as well.’

Practical implications

The participants in this study expressed positive perceptions of CLASS in the Norwegian ECEC context. The shared professional structure contributed to professionalisation and quality in their daily practice, which positively influenced children’s development and collaboration with parents. A common language (Dufour Citation2016) and continuous learning processes over an extended period of time (Fullan Citation2014) at the system level (Senge Citation1999) might provide opportunities for significant collective learning in ECEC organisations. Although this small-scale study’s findings should not be generalised to other contexts, we cannot disregard the possibility that the application of CLASS as an evaluation and feedback system in other contexts may have similar effects. Despite the fact that this is a small-scale study the findings may contribute to a more nuanced debate regarding the use of ECEC quality assessment tools as CLASS. In a ECEC field dominated by qualitative research methods (Alvestad et al. Citation2009) some might have feared that quantitative assessment tools such as CLASS fail to capture the complexity of quality. Findings from the present study indicate that CLASS may have many strengths when it is applied to a sociocultural context e.g. by using it for more than just a grading system. Findings support an idea of CLASS as a facilitator of professional learning communities which is actually in line with the sociocultural learning perspective, where learning for ECEC professionals occurs during interaction and dialogue with colleagues and other ECEC organisations. Quality assessment tools are currently mainly used to verify quality in ECEC in Norway but should also be considered used for professional learning and development.

Study limitations

Given the study design, we cannot know whether the unique CLASS structure contributed to the positive results or whether similar perceptions might have been reported with other quality measurement systems. The participants may also have reflected positively on CLASS’s use as part of an overall implementation of change processes in their practice. Such change processes are often characterised by positive attitudes towards the pursuit of new goals (Fixsen et al. Citation2005; Greenberg et al. Citation2005). As a consequence of the sampling process in this study, self-selection bias may have occurred. Participants who volunteered to this study may be professionally committed and positive to the use of CLASS in the municipality. It is also important to acknowledge that the participants were interviewed at the beginning of the global COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced their experiences and sense of need for a shared community and platform.

Summary and future research

The present study expands on existing research with its investigation of the qualitative aspects of CLASS and contributes to current research by highlighting ECEC professionals’ perceptions regarding the use of CLASS. Results indicate that the CLASS system functions as a structure for learning on the collective and individual levels, for practitioners, children and their parents in Norwegian ECEC services. Future research would benefit from a broader approach to the study of CLASS in ECEC, for example, by asking the children themselves about their everyday experiences in relation to the domains and dimensions of CLASS. Since CLASS is applied so widely in ECEC contexts worldwide, it is important to understand its application as well as its benefits and possible limitations for children.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alvestad, M., L. Gjems, E. Myrvang, B. J. Storli, E. I. B. Tungland, L. K. Velde, Kjersti Lønning, and E. Bjørnestad. 2019. Kvalitet i barnehagen. Rapporter fra Universitetet i Stavanger; 85, Issue.

- Alvestad, M., J.-E. Johansson, T. Moser, and F. Søbstad. 2009. “Status og Utfordringer i Norsk Barnehageforskning.” Nordisk Barnehageforskning 2 (1).

- Berg, B. L., H. Lune, and H. Lune. 2004. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences (Vol. 5). Pearson Boston, MA.

- Bjørnestad, E., and E. Os. 2018. “Quality in Norwegian Childcare for Toddlers Using ITERS-R.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 26 (1): 111–127.

- Breen, R. L. 2006. “A Practical Guide to Focus-Group Research.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 30 (3): 463–475.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard University Press.

- Burchinal, M., C. Howes, R. Pianta, D. Bryant, D. Early, R. Clifford, and O. Barbarin. 2008. “Predicting Child Outcomes at the end of Kindergarten from the Quality of pre-Kindergarten Teacher–Child Interactions and Instruction.” Applied Developmental Science 12 (3): 140–153.

- Cadima, J., G. Nata, S. Barros, V. Coelho, and C. Barata. 2020. Literature review on early childhood education and care for children under the age of 3. doi:10.1787/a9cef727-en.

- Dalli, C., E. J. White, J. Rockel, I. Duhn, E. Buchanan, S. Davidson, S. Ganly, L. Kus, and B. Wang. 2011. Quality early childhood education for under-two-year-olds: What should it look like? A literature review. Report to the Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education: New Zealand.

- Dufour, R. 2016. Håndbog i Professionelle Læringsfællesskaber. Dafolo A/S.

- Engvik, M., L. Evensen, K. Gustavson, F. Jin, R. Johansen, R. Lekhal, S. Schjølberg, M. V. Wang, and H. Aase. 2014. Sammenhenger Mellom Barnehagekvalitet og Barns Fungering ved 5 år. Resultater fra Den Norske mor og Barn-Undersøkelsen. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet.

- Evertsen, C., K. Tveitereid, H. Plischewski, C. Hancock, and I. Størksen. 2015. På Leit Etter Læringsmiljøet i Barnehagen. En Synteserapport fra Læringsmiljøsenteret ved Universitetet i Stavanger. Stavanger: Læringsmiljøsenteret.

- Fauskanger, J., and R. Mosvold. 2014. “Innholdsanalysens Muligheter i Utdanningsforskning.” Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift 98 (02): 127–139.

- Fixsen, D. L., S. F. Naoom, K. A. Blase, R. M. Friedman, F. Wallace, B. Burns, W. Carter, R. Paulson, S. Schoenwald, and M. Barwick. 2005. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature.

- Flaspohler, P., J. Duffy, A. Wandersman, L. Stillman, and M. A. Maras. 2008. “Unpacking Prevention Capacity: An Intersection of Research-to-Practice Models and Community-Centered Models.” American Journal of Community Psychology 41 (3): 182–196.

- Fullan, M. 2014. Teacher Development and Educational Change. Routledge.

- Greenberg, M. T., C. E. Domitrovich, P. A. Graczyk, and J. Zins. 2005. “The Study of Implementation in School-Based Preventive Interventions: Theory, Research, and Practice.” Promotion of Mental Health and Prevention of Mental and Behavioral Disorders 3: 1–62.

- Hamre, K. B. 2014. “Teachers Daily Interactions with Children: An Essential Ingredient in Effective Early Childhood Programs.” Child Development Perspectives 8 (4): 223–230.

- Hamre, B. K., and R. C. Pianta. 2007. “Learning Opportunities in Pre-School and Early Elementary Classrooms.” In School Readiness and the Transition to School, edited by R. C. Pianta, M.J. Cox, and S. J. Snow, Vol. 1, pp. 49–84. B rookes.

- Harding, J. 2018. Qualitative Data Analysis: From Start to Finish (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Limited.

- Helmich, E., S. Cristancho, L. Diachun, and L. Lingard. 2017. “How would you call this in English?” Perspectives on Medical Education 6 (2): 127–132.

- Howes, C., M. Burchinal, R. Pianta, D. Bryant, D. Early, R. Clifford, and O. Barbarin. 2008. “Ready to Learn? Children's pre-Academic Achievement in pre-Kindergarten Programs.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 23 (1): 27–50.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288.

- Krueger, R. A., and M. A. Casey. 2015. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research (5th ed.). Sage publications.

- Kucirkova, N., C. Evertsen-Stanghelle, I. Studsrød, I. B. Jensen, and I. Størksen. 2020. “Lessons for Child–Computer Interaction Studies Following the Research Challenges During the Covid-19 Pandemic.” International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction 26: 100203.

- La Paro, K. M., B. K. Hamre, and R. C. Pianta. 2012. Classroom Assessment Scoring System. Manual, Toddler. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- La Paro, K. M., R. C. Pianta, and M. Stuhlman. 2004. “The Classroom Assessment Scoring System: Findings from the Prekindergarten Year.” The Elementary School Journal 104 (5): 409–426.

- Lekhal, R., M. V. Wang, and S. Schjølberg. 2013. Sammenhengen mellom barns deltakelse i norske barnehager og utviklingen av språk og atferd i tidlig barndom. Resultater fra Den norske mor- og barnundersøkelsen. [The link between children’s participation in Norwegian ECEC and the development of language and behaviour in early childhood. Results from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study]. (Utdanning, Issue).

- Lune, H., and B. L. Berg. 2017. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences (9th ed.). Pearson.

- Mashburn, A. J., R. C. Pianta, B. K. Hamre, J. T. Downer, O. A. Barbarin, D. Bryant, M. Burchinal, D. M. Early, and C. Howes. 2008. “Measures of Classroom Quality in Prekindergarten and Children’s Development of Academic, Language, and Social Skills.” Child Development 79 (3): 732–749.

- Mayring, P. 2000. Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/2-00/02-00mayring-e.htm.

- Melhuish, E. C. 2011. “Preschool Matters.” Science 333 (6040): 299–300.

- Meyers, D. C., J. A. Durlak, and A. Wandersman. 2012. “The Quality Implementation Framework: A Synthesis of Critical Steps in the Implementation Process.” American Journal of Community Psychology 50 (3-4): 462–480.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2020. Qualitative Data Analysis. A Methods Sourcebook (4. ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Ministry of Education and Research. 2017. Framework Plan for the Content and Tasks of Kindergartens. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf.

- Morgan, D. L. 1993. “Qualitative Content Analysis: A Guide to Paths not Taken.” Qualitative Health Research 3 (1): 112–121.

- Moser, T., P. Leseman, M. Broekhuizen, and P. Slot. 2017. European Framework of Quality and Wellbeing Indicators: CARE: Curriculum & Quality Analysis and Impact Review of European Early Childhood Education and Care. (613318).

- OECD. 2019. Providing Quality Early Childhood Education and Care.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. “Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective.” Qualitative Social Work 1 (3): 261–283.

- Pianta, R. C., B. Hamre, and M. Stuhlman. 2003. “Relationships Between Teachers and Children.” Handbook of Psychology, 199–234.

- Pianta, R. C., K. M. La Paro, and B. K. Hamre. 2008. Classroom Assessment Scoring System™: Manual K-3. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Pianta, R. C., K. M. La Paro, and B. K. Hamre. 2013. Classroom Assessment Scoring System. Manual Pre-K. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Rege, M., I. F. Solli, I. Størksen, and M. Votruba. 2018. “Variation in Center Quality in a Universal Publicly Subsidized and Regulated Childcare System.” Labour Economics 55: 230–240. doi:.

- Rege, M., I. Størksen, I. C. F. Solli, A. Kalil, M. M. McClelland, D. Ten Braak, R. Lenes, et al. 2019. Promoting Child Development in a Universal Preschool System: A Field Experiment. Cesifo Working Papers, 7775-2019.

- Roland, P., and K. S. Ertesvåg. 2018. Implementering av Endringsarbeid i Barnehagen. Gyldendal.

- Säljö, R. 2001. Læring i Praksis: Et Sosiokulturelt Perspektiv. Cappelen akademisk.

- Senge, P. 1999. The Fifth Discipline: The art and Practice of the Learning Organization. London: Random House Business Books.

- Sheridan, S. 2001. Pedagogical quality in preschool: An issue of perspectives.

- Shonkoff, J. P. 2010. “Building a new Biodevelopmental Framework to Guide the Future of Early Childhood Policy.” Child Development 81 (1): 357–367.

- Siegel, D. J. 2020. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape who we are. Guilford Press.

- Skjervheim, H. 1996. Deltakar og Tilskodar. I Deltakar og Tilskodar og Andre Essays (s. 71− 87). Oslo: Aschehoug. Kontaktperson: Lis Tenold tlf, 55(58), 33.

- Stålsett, U. E. 2006. Veiledning i en Lærende Organisasjon. Universitetsforl.

- Stoll, L. 2010. “Connecting Learning Communities: Capacity Building for Systemic Change.” In Second International Handbook of Educational Change, 469–484. Springer.

- SSB. 2021. Statistics Norway. https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/barnehager/statestikk/barnehager.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1980. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard university press.

- Vygotsky, L. 2001. Tenkning og Tale (Bielenberg og Roster Overset.). Oslo: Gyldendal Akademiske. (eng. utg. 1986).

- Wandersman, A., J. Duffy, P. Flaspohler, R. Noonan, K. Lubell, L. Stillman, M. Blachman, R. Dunville, and J. Saul. 2008. “Bridging the gap Between Prevention Research and Practice: The Interactive Systems Framework for Dissemination and Implementation.” American Journal of Community Psychology 41 (3-4): 171–181.

- Yoshikawa, H., C. Weiland, J. Brooks-Gunn, M. R. Burchinal, L. M. Espinosa, W. T. Gormley, J. Ludwig, K. A. Magnuson, D. Phillips, and M. J. Zaslow. 2013. Investing in our future: The evidence base on preschool education.

Appendix

Interview guide with CLASS observers

What do you think about CLASS’s use as a quality measuring instrument? What do you think about CLASS as a tool for feedback and development?

CLASS has three domains: emotional support, classroom organisation and instructional support. Do you experience the domains as useful in terms of development work and quality goals in ECEC centres?

Are there aspects of CLASS that you consider to fit well or less well with the Norwegian context or with the Norwegian Framework Plan?

What advantages and disadvantages do you perceive in the use of systematic tools to observe the care and learning environment provided by kindergartens?

Is there a need for adjustments in CLASS or the Norwegian kindergarten context with respect to promoting children’s emotional and cognitive development?

Interview guide with ECEC staff who have been observed and who receive guidance through CLASS

What is your opinion about CLASS as a tool for feedback and development?

Are there aspects of CLASS that you consider to fit well or less well with the Norwegian context or with the Norwegian Framework Plan?

What advantages and disadvantages do you see in using systematic tools to observe the care and learning environment in ECEC centres?

How does it feel to be systematically observed and to receive guidance based on the CLASS observers’ observations?