ABSTRACT

Despite rapid growth in young children visiting museums, and an increasing acknowledgement that these visits are important to children’s development as cultural citizens [Mudiappa and Kluczniok 2015. “Visits to Cultural Learning Places in the Early Childhood.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 23 (2): 200–212] there is still relatively little published research on children’s encounters with them [Hackett, Holmes, and Macrae 2020. Working with Young Children in Museums: Weaving Theory and Practice. London: Routledge]. Our practitioner-led ‘playgroup-in-residence’ explored how young children made sense of the museum in dialogue with the objects, spaces, and people within it. Working within an interpretivist framework, we collectedrich multimodal data and used grounded theory to identify significant patterns in children’s responses. One important theme was the way in which children made marks and left traces to both explore and communicate their emerging sense of belonging within the museum. Our findings have implications for understanding how young children enter into dialogue with environments outside the home. This work is important as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, during which children have spent long periods at home. It is vital that we support them to forge relationships with places and spaces within the wider community.

1. Introduction

This paper brings together different perspectives on how young children negotiated a sense of belonging and made meaning during a Playgroup in Residence project at The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. The project was planned and delivered collaboratively by playgroup practitioners and museum educators. All staff members were involved in the data gathering process, with analysis being undertaken by the two museum educators who have written this paper. We used the rich, multimodal and polyvocal data generated during the residency to respond to the question: how do three- and four-year-olds make sense of the museum in dialogue with the people, spaces and objects within it?

1.1. Children as cultural citizens

States Parties shall respect and promote the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life and shall encourage the provision of appropriate and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational and leisure activity. (United Nations Citation1989)

Participation in cultural life necessarily goes beyond the individual. Previous research shows social, emotional, and cognitive benefits for young children of group museum visits (Bowers Citation2012; D. Anderson et al. Citation2002; Akamca, Yildirim, and Ellez Citation2017; Unal and Pinar Citation2017; Andre, Durksen, and Volman Citation2017; Carr et al. Citation2018). But culture is also dependent on a feeling of belonging; it is a way in which we create a group identity (Boldermo Citation2020). Therefore, individuals must communicate with the wider group. In depth examinations of communication between children and their caregivers in museums undertaken previously have focused primarily on verbal interactions (Wolf and Wood Citation2012; Knutson et al. Citation2016; Briseño-Garzón Citation2013; Vandermaas-Peeler, Massey, and Kendall Citation2016; Lee Citation2020; Degotardi et al. Citation2019; To, Tenenbaum, and Wormald Citation2016; Letourneau et al. Citation2017). It is only recently that children’s bodily and material interaction with museum objects and spaces has become a focus for researchers (Hackett, Holmes, and Macrae Citation2020).

1.2. Physical encounters with the museum

Physical interaction is particularly relevant in the public context of an art museum building. The public galleries are social spaces where we contemplate objects resulting from interactions between human and non-human agents. Human beings manipulate and transform materials to navigate their place in the world, to demonstrate their importance, and to communicate, ‘I was here, and I mattered.’ How then do young children, whose experiences and artworks may not be represented on the walls of the museum, understand and express the importance of their presence in such a place? Nutbrown and Clough (Citation2009) argue that children’s sense of belonging is dependent on feeling that they are able to be active participants in a particular context, and that their contributions are valued. How can we find space among these great artworks and historical artefacts, all clamouring to assert their significance to our shared cultural heritage, for children to be able to declare, ‘I was here too, and I also mattered’?

1.3. Mark making and belonging

Being able to make a mark that denotes this sense of being present in a space that welcomes and accepts you is an important way of establishing a relationship with it. It is important to have one’s impact on a place recognised in order to develop a sense of belonging. Leaving a trace represents a way to enter into lasting dialogue with people, places or objects and this builds a sense of belonging:

We build a sense of belonging in the world based on the meanings we give our environment by moving through and engaging with it. (May Citation2011, 371)

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Socio-constructivism

Working within an interpretive paradigm, we recognise that understandings and interpretations are partial and subjective and, therefore, not generalisable. However, funds of knowledge theory (González, Moll, and Amanti Citation2005), reminds us that each individual perspective stems from a place of competence and value. Our research was shaped by a desire to construct new knowledge by facilitating interactions between people with a range of perspectives and expertise. By working co-operatively to combine ideas, researchers and participants create new knowledge together. This is consistent with the socio-constructivist model (Hein Citation1998) in which learning takes place through the interaction between the personal, social and physical context of the museum (Falk and Dierking Citation2018). The position of the more knowledgeable expert, and that of the novice, are interchangeable between adult and child, as all are perceived as experts in their own lives (Clark and Statham Citation2005).

2.2. Post-humanism

Hackett, Holmes, and Macrae (Citation2020) argue that previous research on learning in museums has over emphasised the verbal aspects of interaction and dialogue and failed to account for other types of communication and exchange which take place such as material and bodily entanglements. These are of particular relevance in settings such as museums, where sensory stimulation and physical experience may overshadow verbal communication and for young children who might be unfamiliar with such places, and at an early stage of language development. Consequently, our theoretical framework also draws on elements of post-human theories (Mustola Citation2018; Macrae et al. Citation2018) in which encounters and exchanges with non-human agents: museum objects, display cases, art materials and gallery spaces, are considered as meaning making practices.

3. Methodology

3.1. Our role as practitioner researchers and arts educators

As experienced museum educators, we are uniquely positioned not only to explore young children’s meaning making, but also to transfer knowledge gained straight back into practice (Pascal and Bertram Citation2012). Our identity as practitioner-researchers acknowledges the role of embodied, tacit knowledge as part of the research process (Pringle Citation2020). We draw on multiple strategies to help young children to feel confident, and to encourage, support and attend to their responses.

Our positionality meant that our methodology was shaped by our pedagogical approach and values (Wall Citation2018). In line with our participatory ethos, the project was built on key shared understandings which were negotiated by museum and playgroup staff at the earliest stages of planning. The localised experience and professional expertise of the museum and playgroup staff was valued as a trustworthy base from which to plan (Pascal and Bertram Citation2012). This was in part due to our commitment to a democratic and equitable distribution of roles, responsibilities, and input into the project, but also to build ‘pedagogic appropriateness’ (Wall: 11) into the research design. Wall suggests that enquiries closely aligned with existing practice are more likely to be effective in developing it further.

3.2. Museum as forum

Participatory arts practice seeks to counter traditional hierarchies of power by bringing to the fore voices and perspectives that have been ignored or suppressed (Pringle and DeWitt Citation2014; Burnham Citation2011; Freire Citation1970). The museum is understood as a site of multimodal dialogue and interaction to which everyone can contribute, rather than as a treasure trove of knowledge, accessible only to the initiated few (Cameron Citation1971; Mai and Gibson Citation2011). We concur with Carr et al.’s (Citation2018) understanding of the museum as a ‘forum’ for debate and a ‘broker’ of creativity and critique’ rather than a ‘temple’. (558).

3.3. Multimodal data

The gathering of rich data is necessary for developing situated knowledge in a case study approach (Stake Citation1995) and is critically important for a multi-perspectival view of the museum (Flyvbjerg Citation2011). Previous work (Elwick et al. Citation2019; Mcleod et al. Citation2017; Piscitelli and Penfold Citation2015) has shown that children respond to the multisensory environment of the museum multimodally. It was therefore important to capture the variety of ways that the children used to communicate: verbal and non-verbal discourses including physical movement, sound, drawing & mark making, construction, and imaginative play.

We recognise that small scale interpretivist research makes our findings context-specific and not generalisable. We are also mindful of external accountability within practitioner research and acknowledge that our position makes it difficult to identify long-standing, ingrained bias. As a counter to this, we sought an openness to new perspectives, to help to shift our focus from what we expected to see, based on what we have seen before. Positioning all participants in the research project as contributors with unique insights enabled us to challenge assumptions and learn together. A commitment to building knowledge through shared data gathering based on interactions between children, the adults and the environment was thus seen as a way of increasing the scope and depth of our understanding, rather than providing confirmation of our assumptions by triangulation. Additionally, generating the data together was part of our commitment to rebalancing power as it allowed for varied and shifting reflections from all those involved in the research (Tracy Citation2010).

3.4. Ethical considerations

The EECERA Ethical Code for Early Childhood Researchers (Bertram et al. Citation2015) guided our approach: aware of our responsibilities towards the participants in the project, but also the wider residents of the city. We viewed each relational encounter, whether between institutions, individuals, opinions, or physical materials as a site of ethical responsibility and commitment (Beausoleil Citation2015).

As part of our aspiration to bring the benefits of museum visiting to the widest possible range of people, we identified a city playgroup serving a catchment that is currently underrepresented among museum visitors, to partner with us. In a pre-project questionnaire, one parent said that she had not visited with the museum before because she felt it was, ‘too posh for us’. By working with the group over an extended period, we hoped to build new, positive relationships between the museum and the local community. Playgroup staff made a purposeful sample of ten children to take part in the project.

Parents were given information to help them make an informed decision about giving consent for their children to take part. This included details on the use, storage and sharing of photographs. Parents gave their consent for photographs to be included in publications on the understanding that the children’s real names would not be used.

In order to ensure our sample was not biased by exclusionary selection procedures, participant information and consent forms were carefully evaluated and discussed by the project Advisory Group. Playgroup staff supported non-literate families to access the information in order to increase the likelihood of participation for those who had not visited the museum before. It was emphasised that participation was voluntary, and would not impact any future visit opportunities.

In advance of the project, the museum educators visited the children at playgroup and used photographs to introduce the museum. The children also had opportunities to discuss the project with their keyworkers and were asked before each visit if they would like to go to or to stay at playgroup. Both parental consent and children’s assent were seen as ongoing processes, and so parents were kept informed through regular updates from the playgroup. All staff were attentive to the comfort and wellbeing of the children, ensuring that they felt confident to choose how to participate (or not) in the activities.

4. Research procedure

Ten children (aged between three and four years) from a local playgroup visited the Fitzwilliam Museum five times over the course of the Spring term 2020. This was subsequently revised to four visits only due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the temporary closure of the museum and the playgroup.

4.1. Data generation

We used a systematic approach to capturing film (10-minute clips taken at 30 min intervals during the visits) and collected pre and post visit surveys. Other data was generated spontaneously when children and adults felt that they wished to record something. The disadvantage of this approach is that data reflects the interests, experience, and biases of those involved with the project and so certain moments and perspectives will have been missed. However, the films provided an additional layer of detail that was not always captured in notes ().

Table 1. Data gathered at different points during the research.

This broad range of data types was a challenge to analyse, however, it meant that the same moment or theme could be examined from a number of different perspectives and we were able to capture verbal and non-verbal meaning making practices (Mukherji and Albon Citation2010). This approach recognises that meanings are interpreted and changeable rather than representing a single truth, in line with our interpretivist paradigm.

4.2. Data analysis

The analysis of the data was carried out by the museum-based practitioner researchers. We worked independently and then came together to compare and agree on our key themes. We then met with the playgroup Head Teacher to discuss our findings. We used a grounded approach to data analysis (Charmaz Citation2006) to develop a situated understanding of the specific context of our study, rather than try to apply more general, pre-existing theories. In addition, by choosing not to identify possible themes in advance, we hoped to avoid the tendency to see what we had hoped for in the data.

We used Altheide and Schneider (Citation2013)’s description of systematic qualitative content analysis to analyse our data. We worked to familiarise ourselves with the data, re-reading our notes and re-viewing videos. Certain motifs, patterns, and topics were identified across the range of data through an iterative process of comparing the different data types. At this stage, it became clear that having the museum and playgroup educators recording their fieldnotes separately, rather than through a shared discussion was advantageous, because when the same issue or event appeared repeatedly, this was a good indication of its significance. We then worked together to synthesise patterns into four main themes. Finally, we returned to the data, to test the suitability of our themes.

5. Findings

One of the key themes which emerged was children’s interest in leaving and exploring physical, verbal, and graphic traces over the course of the residency. We found evidence of this across many different modes of engagement as children imagined and created imprints of themselves and others in the places they had been. The following descriptions focus on ways in which the children made and responded to footprints, traces and marks both individually and as part of a group.

5.1. ‘I’ll lead us all the way’ – tracing footprints together

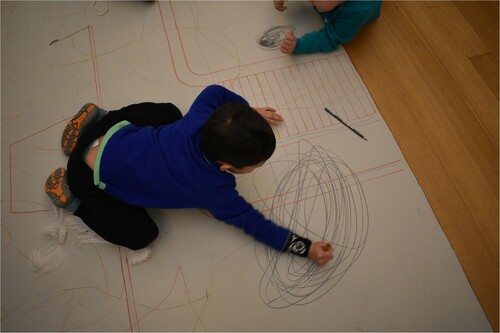

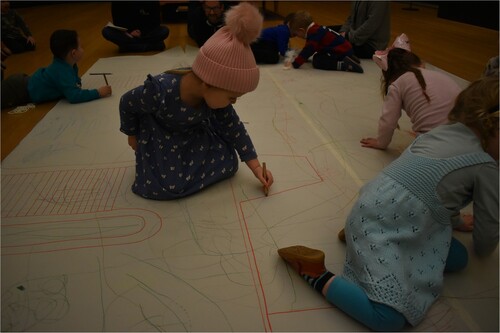

The children’s interest in footprints became apparent during the first two visits, and in response, the museum educators created a large floor plan for the children to draw on during the third visit. shows this taped to the floor of Gallery 3: a large room displaying British art from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The floor plan contained features of the museum spaces with lined grids to show the stairs and squares to represent the position of large free-standing radiators in room. The gallery space is depicted by lines around the outside of the plan showing the walls and marking the entrances. Children are offered coloured pencils to draw on the plan.

In , Susie (wearing a headband, pictured in the top centre) puts a dot on each of the lines representing a step. Lee places himself inside the drawing, sitting on his knees to Susie’s left. He says, ‘I’ll lead us all the way … ’ and draws a line from one edge as far as he can towards the other side extending his body and his arm until he collides with Andrew’s drawing which is taking shape in the middle of the paper (Andrew is shown in the centre of the paper in ). Lee then starts another line and says, ‘all the way!’ again and then moves across the paper to draw a long line to the edge of the plan saying, ‘And then all the way back home.’ Andrew narrates as he draws: ‘he’s gone all the way out there now.’ He traces the lines drawn by the adults to represent the gallery features.

Lee and Sonia are very active, crawling across the paper as they draw: the marks they make appear and remain as visible traces of their presence and movement. In Lee uses his body to occupy space on the plan while quickly drawing large circles to fill up a previously unused space. In , by contrast, Sonia waits until the other children have moved away before slowly adding her own marks to the lines already there, carefully connecting and enclosing lines and shapes made by the museum educators and other children.

In this example, we see how fleeting and momentary forms of meaning making (Hackett Citation2012; Citation2015) are transformed into something more tangible and long-lasting through the drawing of marks and paths. Creative activities such as this provide opportunities to record share and negotiate, as material marks, their embodied experiences. The marks they make are not exact replications of their movements but are lived and enacted happenings and conversations in their own right. Drawing is a physical and full body experience: capturing the material encounter between child, pencil, paper, and gallery space (Matthews Citation2003; Dardanou Citation2019). The footprints and pathways that the children (re)create, depict, extend and continue the dialogue with the museum space, even as they are documenting it. Making a trace is seen as a powerful, creative and active event.

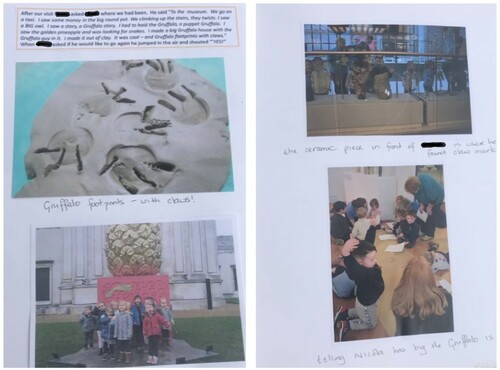

5.2. ‘Come and see this! Look!’ – connecting with and through the marks left by others

We also found examples of children using traces as a way to connect with museum objects by interacting with the marks made by others. On the first visit, the children read the picture book The Gruffalo (Donaldson Citation1999) during the museum session. On the way through the galleries to read the story, Joseph noticed Ceramic Vessel by Sarah Radstone, and excitedly told the group that he could see Gruffalo claw marks on the pot. On each subsequent visit, the group, usually led by Joseph, would pause at this object to look for the Gruffalo prints and scratches. This repeated behaviour marked the transition from the art studio into the galleries on each subsequent visit. Footprints, trails, and claw marks, in particular those of the Gruffalo, featured regularly in Joseph’s sketchbook. shows a collage in his sketchbook including a picture of his clay model of the Gruffalo claw marks alongside a photograph of him and the group looking at the ceramic vessel. The playgroup staff record his description of this visit:

I saw a story, a Gruffalo story. I had to hold the Gruffalo, a puppet Gruffalo. I saw the golden pineapple and was looking for snakes. I made a big Gruffalo house with the Gruffalo guy in it. I make it out of clay. It was cool – and Gruffalo footprints and claws.

When new adults joined the group in later visits, Joseph introduced them to the ‘Gruffalo Pot’ as shown in the photograph in the top right of . ‘Come and see this! Look – this is the Gruffalo claws,’ he said to our visitor when we went up the stairs and into the galleries at the start of Visit Three. On Visit Four, Joseph used a similar approach to welcome another visitor into our group, saying ‘I love the Gruffalo claws … I could show him the Gruffalo claws. I know a way! I’ll go first!’ Arriving at the case, Joseph pointed to the ceramic vessel. Elizabeth pushed both her hands flat against the case containing the ‘Gruffalo Pot’ and turned to make eye contact with her playgroup teacher and the newly arrived visitor, inviting them to look in as well. In this example, we see the importance of marks made by others in helping the group negotiate their sense of ownership and belonging within the museum. Joseph uses the pot as a way of introducing newcomers to the museum experience.

6. Analysis and discussion

6.1. Mark making as active participation

The examples above show children individually and collectively making sense of their experience of being in the museum through mark making. Sometimes this was in the form of a record or reimagining of their experience, and sometimes as a way of responding to the marks left by others whether fictional characters or real artists. Waller, Hallborg, and Benedetti (Citation2018) discuss the use of traces as a way for young children to see their impact on a place, and we found this to be important aspect of how the children made meaning during the residency. Museums can seem inaccessible and overwhelming and so providing invitations to the group to leaving their own marks and traces in a variety of different ways offered an opportunity to transform their relationship with and movement within the museum.

Crucially, as well as an interaction with place, trace leaving is a way of sharing, comparing and interacting with other people’s experiences. In Section 5.1, the children respond to the marks and movements left by others as they make their own marks. To be a cultural citizen means to enter into dialogue with, and be shaped by the ideas of others, and the opportunity to engage in collective or collaborative mark making could be a useful way for young children to experience this (Knight Citation2008).

6.2. The power of drawing

Drawing tracks and trails as in the floor plan example above is a dynamic process (Deguara and Nutbrown Citation2018; Pahl Citation1999)in which children reimagine, recreate and communicate their experience of the museum. The motif of being able to travel ‘all the way’ on the drawn gallery plan, and the children’s interest in extending the drawing right to its edges of the paper show an understanding of the imaginative and communicative possibilities of drawing within the museum space. The children did not walk right up to the real gallery walls, understanding that they needed to remain a safe distance from the artworks, however, drawing gave them the opportunity to get closer. Pencil and paper can take us to places that we might not be able to reach in real life. Children use the drawn version of the gallery to make visible and describe their relationship with the space. The way that their move their bodies and pencils during the activity reveals an understanding of the space and their relationship to it– how the staircases, walls, furniture, and paintings fit together, and how this is interlinked with their own routes and journeys around the gallery. The accompanying narration: ‘I’ll lead the way,’ and ‘all the way home’ demonstrates the level of confidence and ownership that the children had gained by this stage of the residency. The gallery has become a place that they know well enough to find their way around independently, and to communicate this to others through their drawing.

6.3. From visitor to citizen

Being able to create a material response to experience, that is to say, being an artist, is particularly relevant in the context of an art museum. In the example above, the ceramic vessel was significant for Joseph as a meeting point for connecting marks he made himself with those he observed in the museum. Its liminal location at the top of the staircase between the art studio and the museum galleries marked a transition point between the children’s own art making and that of others, and a threshold between the more familiar classroom-like feel of the studio and the less familiar gallery spaces.

Over the course of the residency, Joseph gained confidence as he became more accustomed to the museum environment (Dewitt et al. Citation2018), but in addition, his view of himself changed too. From being someone who listens to stories, and who notices the marks that others have made, he has grown into someone who can use the museum to tell his own stories to create marks of his own that show that this is a place he belongs. This is cultural citizenship: ‘the ability to co-author the cultural context in which one lives’ (Boele van Hensbroek Citation2010: 317). With this citizenship comes responsibility, which we see Joseph embracing in the example above as he takes on the role of expert, scaffolding a new experience for the visiting adult as a way of inducting him into the group.

7. Conclusion and implications

Our research investigated how three – and four-year-olds make sense of the museum in dialogue with the people, spaces and objects within it. The rich data we gathered during our extended ‘playgroup in residence’ project demonstrated that children engaged with the museum through an exploration of the traces of their presence such as mark making, trails and footprints. Providing creative and open-ended opportunities for young children enabled them to communicate and negotiate ownership and familiarity to a new environment as autonomous, complex individuals rather than simply component parts of a family or a class group (Kirk Citation2013). Identifying ways to evidence their presence and experience through art activities focusing on traces and trails enables children to declare that they were here, that they belonged here, and that they mattered, in the same way that artworks and objects on display in the museum tell the story of their makers and people.

To date, there has been little focus on how young children communicate a sense of belonging in cultural settings such as art museums despite it being an important aspect of young children’s social and cultural development (Over Citation2016). Although Arts Council England identified Developing Ownership and Belonging as a key principle in their Quality Principles framework (Sharp Citation2015), there is relatively little agreement as to what this might look like in a cultural setting. These examples demonstrate how children can enter into dialogue with an environment through a series of visits and experiences. Recording traces they and others made during these visits supported children to communicate their sense of place. The museum was constructed as a place where they belong, and where their presence has an impact, however small or transient this might be.

Our focus on traces and footprints to support children to communicate, explore and develop their relationship with the museum invites future research on how museum educators, early years practitioners, and parents of young children might use this concept to help frame and shape visits. As we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, museums need to understand how to create programmes and resources that support young children not simply to enter into museum spaces, but to enter into dialogue with them. This is particularly important at a time when the pandemic and its aftermath have highlighted and widened existing inequalities, including those around participation in the arts. If children do not feel that museums are places where they can belong and participate actively, negative stereotypes and feelings of alienation could be reinforced and strengthened (Archer et al. Citation2016). Alternatively, offering opportunities to have one’s experiences recognised and recorded in museums could be an important strategy in healing some of these divisions (Wright Citation2020). Attending to the ways in which children seek to leave evidence of their presence demonstrates that museums are not just a record of the past; that they are also dynamic and responsive places that recognise, value and celebrate the myriad daily interactions between the objects and people that take place within their walls every day.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank Dr David Whitebread, Dr Ros McLellan, Dr Jo Vine, Gemma Spence, Susan Lister & Margaret Winchcomb for their expertise and guidance as part of our Project Advisory Group. We also thank the Fitzwilliam Museum, especially Education Assistants Alison Ayres and Nathan Huxtable and Head of Learning Miranda Stearn, and the staff, children and families of Playlanders playgroup for their support and participation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akamca, Güzin Özyilmaz, R. Gunseli Yildirim, and A. Murat Ellez. 2017. “An Alternative Educational Method in Early Childhood: Museum Education.” Educational Research and Reviews 12 (14): 688–694. https://ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1149758&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Altheide, D., and C. Schneider. 2013. “Ethnographic Content Analysis.” In Qualitative Media Analysis, 2nd ed. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications, Ltd. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452270043.n2.

- Anderson, David, Barbara Piscitelli, Katrina Weier, Michele Everett, and Collette Tayler. 2002. “Children’s Museum Experiences: Identifying Powerful Mediators of Learning.” Curator: The Museum Journal 45 (3): 213–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2002.tb00057.x.

- Andre, L., T. Durksen, and M. Volman. 2017. “Museums as Avenues of Learning for Children: A Decade of Research.” Learning Environments Research 20 (1): 47–76.

- Anning, Angela, and Kathy Ring. 2004. Making Sense of Children’s Drawings. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Archer, Louise, Emily Dawson, Amy Seakins, and Billy Wong. 2016. “Disorientating, Fun or Meaningful? Disadvantaged Families’ Experiences of a Science Museum Visit.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 11: 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-015-9667-7.

- Beausoleil, E. 2015. “Embodying an Ethics of Response-Ability.” Borderlands 14 (2): 1–25.

- Bertram, T., J. Formosinho, C. Gray, C. Pascal, and M. Whalley. 2015. “EECERA Ethical Code for Early Childhood Researchers.”

- Boele van Hensbroek, Pieter. 2010. “Cultural Citizenship as a Normative Notion for Activist Practices.” Citizenship Studies 14: 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13621021003731880.

- Boldermo, Sidsel. 2020. “Fleeting Moments: Young Children’s Negotiations of Belonging and Togetherness.” International Journal of Early Years Education 28 (2): 136–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2020.1765089.

- Bowers, Betsy. 2012. “A Look at Early Childhood Programming in Museums.” Journal of Museum Education 37 (1): 39–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2012.11510716.

- Briseño-Garzón, Adriana. 2013. “More than Science: Family Learning in a Mexican Science Museum.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 8 (2): 307–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-012-9477-0.

- Burnham, Rika. 2011. Teaching in the Art Museum: Interpretation as Experience. Edited by Elliott Kai-Kee. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Cameron, D. 1971. “A Museum, Temple or Forum.” In Reinventing the Museum: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on the Paradigm Shift, edited by G. Anderson, 11–24. Oxford: AltaMira Press.

- Carr, Margaret, Rebecca Thomas, Andrea Tinning, and Maiangi Waitai. 2018. “Fostering the Artistic and Imaginative Capacities of Young Children: Case Study Report from a Visit to a Museum.” International Journal of Early Childhood 50 (1): 33–46. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1999867722/.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: SAGE.

- Clark, A., and J. Statham. 2005. “Listening to Young Children: Experts in Their Own Lives.” Adoption and Fostering 29 (1): 45–56.

- Dardanou, M. 2019. “From Foot to Pencil, from Pencil to Finger: Children as Digital Wayfarers.” Global Studies of Childhood 9 (4): 348–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610619885388.

- Degotardi, Sheila, Kelly Johnston, Helen Little, Yeshe Colliver, and Fay Hadley. 2019. ““This is a Learning Opportunity”: How Parent–Child Interactions and Exhibit Design Foster the Museum Learning of Prior-to-School Aged Children.” Visitor Studies 22 (2): 171–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2019.1664849.

- Deguara, J., and C. Nutbrown. 2018. “Signs, Symbols and Schemas: Understanding Meaning in a Child’s Drawings.” International Journal of Early Years Education 26 (1): 4–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2017.1369398.

- Dewitt, Jennifer, Heather King, Denise Wright, and Kate Measures. 2018. “The Potential of Extended Cultural Residencies for Young Children.” Museum Management and Curatorship 33 (2): 158–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2018.1442241.

- Donaldson, J. 1999. The Gruffalo. New York: Dial Books for Young Readers.

- Elwick, A., P. Burnard, L. Huhtinen-Hildén, J. Osgood, and J. Pitt. 2019. “Young Children’s Experiences of Music and Soundings in Museum Spaces: Lessons, Trends and Turns from the Literature.” Journal of Early Childhood Research, doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X19888717.

- Falk, J., and L. Dierking. 2018. Learning from Museums. 2nd ed. London: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2011. “Case Study.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln, 301–316. London: SAGE.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Books.

- González, N., L. Moll, and C. Amanti, eds. 2005. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities and Classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hackett, A. 2012. “Running and Learning in the Museum: A Study of Young Children’s Behaviour in the Museum, and Their Parents’ Discursive Positioning of That Behaviour.” Childhoods Today 6 (1): 1–21.

- Hackett, A. 2015. “Children’s Embodied Entanglement and Production of Space in a Museum.” In Children’s Spatialities, edited by A. Hackett, L. Procter, and J. Seymour. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137464989_5.

- Hackett, A., R. Holmes, and C. Macrae, eds. 2020. Working with Young Children in Museums: Weaving Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Hein, George E. 1998. Learning in the Museum. London: Routledge.

- Kirk, Elee. 2013. “Gaining Young Children’s Perspectives on Natural History Collections.” Journal of Natural Science Collections 1: 38–43. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/35880608/Journal_of_Natural_Science_Collections_2013_Kirk.pdf?1418120589=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DGaining_young_childrens_perspectives_on.pdf&Expires=1593439697&Signature=UmMUCLe3L1PLzYeasWxy.

- Knight, Linda. 2008. “Communication and Transformation Through Collaboration: Rethinking Drawing Activities in Early Childhood.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 9 (4), doi:https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2008.9.4.306.

- Knutson, Karen, Mandela Lyon, Kevin Crowley, and Lauren Giarratani. 2016. “Flexible Interventions to Increase Family Engagement at Natural History Museum Dioramas.” Curator: The Museum Journal 59 (4), doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12176.

- Lee, Tiffany Shuang-Ching. 2020. “Curriculum Based Interactive Exhibition Design and Family’s Learning Experiences: A Case Study of the Children’s Art Museum in Taipei.” Curator: The Museum Journal 63 (1): 83–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12341.

- Letourneau, Susan M., Robin Meisner, Jessica L. Neuwirth, and David M. Sobel. 2017. “What Do Caregivers Notice and Value About How Children Learn Through Play In a Children’s Museum?” Journal of Museum Education 42: 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2016.1260436.

- Macrae, Christina, Abigail Hackett, Rachel Holmes, and Liz Jones. 2018. “Vibrancy, Repetition and Movement: Posthuman Theories for Reconceptualising Young Children in Museums.” Children’s Geographies 16 (5): 503–515. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2017.1409884.

- Mai, Lea, and Robyn Gibson. 2011. “The Rights of the Putti: A Review of the Literature on Children as Cultural Citizens in Art Museums.” Museum Management and Curatorship, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2011.603930.

- Matthews, J. 2003. Drawing and Painting: Children and Visual Representation. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

- May, V. 2011. “Self, Belonging and Social Change.” Sociology 45 (3): 363–378.

- Mcleod, Naomi, Denise Wright, Katy Mccall, and Michiko Fujii. 2017. “Visual Rhythms: Facilitating Young Children’s Creative Engagement at Tate Liverpool.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (6): 930–944.

- Mudiappa, Michael, and Katharina Kluczniok. 2015. “Visits to Cultural Learning Places in the Early Childhood.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 23 (2): 200–212. https://ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bri&AN=102274219&authtype=shib&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Mukherji, P., and D. Albon. 2010. Research Methods in Early Childhood. London: SAGE.

- Mustola, M. 2018. “Children’s Play and Art Practices with Agentic Objects.” In Communities of Practice: Art, Play, and Aesthetics in Early Childhood, edited by C. Schulte, and C. Thompson, 117–132. New York: Springer.

- Nutbrown, Cathy, and Peter Clough. 2009. “Citizenship and Inclusion in the Early Years: Understanding and Responding to Children’s Perspectives on ‘Belonging’.” International Journal of Early Years Education 17 (3). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760903424523.

- Over, H. 2016. “The Origins of Belonging: Social Motivation in Infants and Young Children.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371 (1686): 1–8.

- Pahl, K. 1999. Transformations: Children’s Meaning Making in a Nursery. Stoke on Trent: Trentham.

- Pascal, Chris, and Tony Bertram. 2012. “Praxis, Ethics and Power: Developing Praxeology as a Participatory Paradigm for Early Childhood Research.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 20 (4): 477–492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2012.737236.

- Piscitelli, B., and L. Penfold. 2015. “Child-Centred Practice in Museums: Experiential Learning Through Creative Play at the Ipswich Art Gallery.” Curator: The Museum Journal 58 (3): 1–18.

- Pringle, E. 2020. Rethinking Research in the Art Museum. London: Routledge.

- Pringle, E., and J. DeWitt. 2014. “Perceptions, Processes and Practices Around Learning in an Art Gallery.” Tate Papers 22.

- Sedgwick, D., and F. Sedgwick. 1993. Drawing to Learn. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Sharp, Caroline. 2015. Using Quality Principles in Work for, by and with Children and Young People: Results of a Pilot Study / Caroline Sharp, NFER, Ben Lee, Shared Intelligence. Edited by Ben Lee and issuing body National Foundation for Educational Research in England and Wales. Slough, Berkshire: National Foundation for Educational Research, October 2015.

- Stake, R. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- To, Cheryl, Harriet R. Tenenbaum, and Daniel Wormald. 2016. “What Do Parents and Children Talk About at a Natural History Museum?” Curator: The Museum Journal 59 (4): 369–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12174.

- Tracy, Sarah J. 2010. “Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 16 (10): 837–851. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121.

- Unal, Fatma, and Yunus Pinar. 2017. “The Crucial Role of Museum-Experience in Early Childhood Education.” Idil Sanat ve Dil Dergisi 6 (38): 2899–2917. https://doaj.org/article/a6893d5b5c814894b213e83da916854c.

- United Nations. 1989. “The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.”

- Vandermaas-Peeler, Maureen, Katelyn Massey, and Alyssa Kendall. 2016. “Parent Guidance of Young Children’s Scientific and Mathematical Reasoning in a Science Museum.” Early Childhood Education Journal 44 (3): 217–224.

- Wall, Kate. 2018. “Building a Bridge between Pedagogy and Methodology: Emergent Thinking on Notions of Quality in Practitioner Enquiry.”

- Waller, T., M. Hallborg, and P. Benedetti. 2018. “Young Children, Public Spaces and Democracy – Reconstructing Early Childhood Education.” 28th EECERA Annual Conference: Early Childhood Education, Families and Communities, Budapest.

- Wolf, Barbara, and Elizabeth Wood. 2012. “Integrating Scaffolding Experiences for the Youngest Visitors in Museums.” Journal of Museum Education 37 (1): 29–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2012.11510715.

- Wright, Denise. 2020. “Engaging Young Children and Families in Gallery Education at Tate Liverpool.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 39 (4), doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12322.