ABSTRACT

Previous studies have emphasised that play can promote children’s learning of mathematics. However, little research has been directed towards understanding how collective imaginary play motivates children's mathematical learning. Informed by the cultural-historical conception of play and motives, this paper examines how Conceptual PlayWorld (CPW) creates conditions for Chinese children's meaningful mathematical learning using the concept of repeating patterns as an example. Video observations of teachers interacting with children (4–5 years) during the CPW implementation (8.54 h), as well as children's interviews (5.75 h), were gathered and analysed. Following the focus child Zeng's motives and intentions but all children's experiences in the CPW, the findings show CPW appears to create mathematical conditions that promote thinking, imagining and play. Zeng's motives for mathematical learning are stimulated by his play motives which are amplified through his active participation and problem-solving in a CPW, and this creates conditions for his personally meaningful learning of mathematics in the Chinese kindergarten context.

Introduction

Research into play-based mathematical education has shown positive effects on children's personal-social, fine motor, language, and gross motor development (Derman, Zeteroğlu, and Birgül Citation2020). While the play-based curriculum reform in China emphasises children's play and active learning (Qi and Melhuish Citation2017; Wang et al. Citation2022), Chinese kindergarten teachers reported difficulties in teaching children mathematics in meaningful ways (Hu et al. Citation2017). Some Chinese teachers tend to adopt the fusion of structured teaching and child-directed learning (Yang and Li Citation2018). For example, a contemporary Chinese mathematical activity in many kindergarten classrooms consists of a teacher introducing a topic, children participating in one to three games or activities on the topic, and children reporting back (Li et al. Citation2018; Li, McFadden, and DeBey Citation2019). Under this situation, researchers indicate that a remarkable amount of teacher-child mathematical interactions were mainly subject-centred and teacher-directed, and did not show children's active participation and meaningful learning (Hu et al. Citation2017). Further, a study undertaken in China with preschool children learning mathematics showed that teachers mostly focused on counting and calculation, which Yang, Luo, and Zeng (Citation2022) reported as being 63.89% of children's mathematical learning. Through engaging in realistic situations, Chinese teachers can situate children's counting and calculation into a meaningful everyday context; however, how children can learn other mathematical concepts meaningfully with the support of teachers is poorly understood (Yang, Luo, and Zeng Citation2022).

According to the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (Citation2012), children need to be exposed to a variety of pattern-related experiences so that they can understand patterns in number, size, shape, colour, and sound in their daily lives. Since Chinese children need support in understanding and learning patterns in meaningful contexts (Weng et al. Citation2022), we designed a study that draws on the repeated pattern, to broaden understandings on if and how CPW creates conditions for developing children's personal and meaningful engagement in mathematics within the Chinese context.

Children's pattern learning in early childhood education

Early pattern learning represents a form of relational reasoning and lays key foundations for young children's mathematical thinking and subsequent mathematical development (Bojorque et al. Citation2021; Miller et al. Citation2016). According to Björklund (Citation2016), a pattern can be regarded as repeated phenomena that follow a predictable order. Particularly, a repeating pattern is a periodic sequence of elements that can be reduced to a ‘unit of repeat’ (Lüken and Sauzet Citation2021). A range of tasks was used to assess and foster young children's repeating pattern learning. To be specific, children's duplicating (or copying) and extending (or fixing, interpolating) of patterns, generalising of patterns (producing the same pattern using different materials or modes), identifying the unit of repeat in a pattern as well as creating patterns have been examined (Lüken and Sauzet Citation2021; Miller et al. Citation2016; Rittle-Johnson, Zippert, and Boice Citation2019).

It is commonly accepted that generalising, finding the unit of repeat and creating patterns are more complex tasks compared to duplicating and extending a pattern (Lüken and Sauzet Citation2021; Rittle-Johnson et al. Citation2015). Through exploring children's strategies when working with repeating patterns, Lüken (Citation2020) found that 5-year-old children focus more on regularity and structure than 3-year-old children. For example, the 5-year-old children mainly used comparison and classification (e.g. looking and comparing with the pattern's beginning), and they focused on sequence (e.g. what is coming next) while working with patterns. However, most of these studies on children's pattern skills and pattern learning were based on the operation of concrete materials and objects, such as arranging blocks and making beaded bracelets (Lüken and Sauzet Citation2021; Tsamir et al. Citation2020). Although play offers a possible way for children to learn how to combine features and follow rules in patterns (Björklund Citation2016), we know little about children's patterning learning in imaginary play (Li and Disney Citation2021), particularly in the Chinese kindergarten context, where more formal practices in mathematical learning are common (Hu et al. Citation2017).

Theoretical framework

The cultural-historical conception of play

While there are different definitions of imaginary play (Lillard et al. Citation2013; Smith Citation2017; Weisberg Citation2015), we adopt a cultural-historical perspective in understanding imaginary play in this paper. The cultural-historical conception of play was first introduced by Vygotsky (Citation1966) as the creation of an imaginary situation, where children change the meaning of things and actions. Along with the imaginary situation and meaning changes, children take on specific roles and follow a set of rules in their play (Bodrova Citation2008). In speaking of play and its role in young children's development, Vygotsky (Citation1966, 6) argued that ‘play is not the predominant form of activity, but is, in a certain sense, the leading source of development in preschool years’. Based on Vygotsky's work, Elkonin (Citation1999) contended that play is the leading activity for young children. However, only with all play elements fully developed and taking mature forms, can play become the leading activity of preschool and kindergarten-aged children (Bodrova Citation2008). There are three characteristics of mature play (Bodrova and Leong Citation2015). First, children use object substitutes to symbolise the objects and use gestures to represent actions. Second, children take on and sustain a specific role by consistently engaging in actions, speech and interactions associated with the pretend scenario. Third, children engage in play scenarios that integrate different themes and a long-time span (several days or even weeks).

In line with the cultural-historical conception of play, the playworld allows children and adults to dramatise play plots based on stories and enter collective imaginary play, where children use words and actions that were collectively understood (Lindqvist Citation1995). Through extending the work of Lindqvist (Citation1995), Fleer (Citation2021a) developed the ‘Conceptual PlayWorld’ (CPW). As a form of mature play (Fleer Citation2021a) and a pedagogical invention (Fleer Citation2019), the CPW connects imagination and drama to conceptual concepts and allows concepts to be explored in the service of children's play (Fleer Citation2019). Particularly, the CPW creates conditions for children's meaningful learning of mathematics, as demonstrated in the Australian context (Li and Disney Citation2021). However, there is a lack of research on how CPW works in promoting children's meaningful mathematical learning in the Chinese context.

Children's motives development

Children's motive development in practice provides a possible way to maintain children's personally meaningful learning (Li and Disney Citation2021). Hedegaard (Citation2002) theorised motives and identified different kinds of motive orientations: dominating motives, meaning-giving motives and stimulating motives. Dominating motives are associated with the type of activities that are central and important to a person's life (Hedegaard Citation2002). Dominating motive is regarded as children's leading motive; for the preschool child, play motives are the dominating motives (Fleer Citation2014). Dominating motives can be used as stimulating motives to develop other motives and stimulate activities which are not motivating at the beginning (Hedegaard Citation2002). Stimulating motives emerge when teachers create motivating conditions in the PlayWorld for conceptual teaching and learning (Fleer Citation2021b). It could be a problem to be solved in imaginary play, which engages children and motivates them to solve problems using mathematical concepts in a personally meaningful way. Meaning-giving motive dominates a person's self-expression. As argued by Hedegaard (Citation2002), dominant motives are always meaning-giving motives because they guide children in a particular way. Meaning-giving motives are where the relations between a child's motives and the social situations that orient children in particular ways which make sense for the child (Fleer Citation2020). By using Hedegaard’s (Citation2002) theorisation of motives, our study aimed to explore how children's dominating motives of play developed as meaning-giving motives (building adventure narratives) and stimulating motives (solving a play problem using repeating patterns) in the Chinese kindergarten context. Children's stimulating motives further stimulate mathematical learning motives, which create conditions for children's personally meaningful mathematical learning.

Play, motives development and children's meaningful mathematical learning

Framed in a cultural-historical perspective where play and motives are featured, we examined studies that conceptualised how imaginary play creates conditions for children's meaningful mathematical learning. First, Papandreou and Konstantinidou’s (Citation2020) participatory play pedagogy illustrates that children can achieve meaningful mathematical learning when their emerging mathematising in imaginary play is listened to, valued and seriously considered by teachers. Second, mathematics has been framed as a cultural activity. van Oers (Citation2010) developed the concept of ‘meaningful learning in a double sense’, which includes the cultural meaning and personal meaning. Cultural meaningful learning is based on actions, goals, tools and symbols, while personally meaningful learning is related to children's personal values, interests and dispositions given their motives (van Oers Citation2010). In play-based mathematical activities, children not only use mathematical concepts to serve their play activities in a personal sense, but elaborate further on specific mathematical concepts in a cultural sense (Broström Citation2017; Worthington and van Oers Citation2016). When children's play motives (e.g. selling and buying shoes) align with the learning goals (e.g. adding and subtracting), children's personally meaningful mathematical learning emerges in the play. Therefore, children's personally meaningful mathematical learning is related to children's motives development in solving mathematical problems, as well as their personal sense of mathematical concepts in their play (Li and Disney Citation2021; van Oers Citation2010). Third, building on the conceptualisation of van Oers (Citation2010), Li and Disney (Citation2021) further developed the concept of meaningful mathematical learning in an Australian early childhood setting using the mathematical playworld. In their study, children imagined ‘as if’ frogs and dogs, making sense of why two dogs cannot sit together (because the dogs will eat each other's cakes) and using the repeating pattern (dog-frog-dog-frog …) to solve the problem. Through stimulating children's motives on making meaning, the mathematical playworld created opportunities for children to attach their personal values associated with the play problems, which in turn promoted children's meaningful mathematical learning (Li and Disney Citation2021). Our study extends Li and Disney’s (Citation2021) conceptualisation of motive development and children's meaningful learning, and explores how CPW creates conditions for children's meaningful mathematical learning in a Chinese kindergarten context.

Study design

Research contexts

Based on cultural-historical theory, this study was framed as an educational experiment (Hedegaard Citation2012), where the CPW approach was used to promote Chinese children's conceptual learning through play in everyday settings. Ethical approval was obtained from the researchers’ university (Project number 7851). Both the staff and child consent forms were collected before we conducted the study. As the children were young, parents were invited to sign the consent forms on behalf of their children. The research process was explained to the children, and parents were asked to consider their children's opinions before signing the forms. Additionally, teachers’ and children's pseudonyms are used in this study to increase confidentiality.

Research participants

The data reported in this paper involved one classroom in one public kindergarten located in Changchun city, Jilin province. In this classroom, 34 children (mean age: 4.65 years old) and two teachers participated. Both of the teachers (Ms Li and Ms Han) in this class held a diploma in early childhood education and teaching.

Procedure for data collection

Researchers cooperated with teachers to implement the CPW by providing ongoing support through Zoom meetings before each session. Three cameras were used in the baseline and CPW data collection, capturing teachers’ perspectives, children's perspectives and the whole setting respectively. Zeng, a boy aged four years and six months, is one of the focus children in the digital video observation and his pattern learning was examined in this paper.

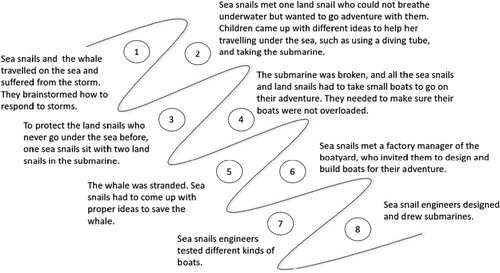

Apart from digital video observation, child interview data were collected to obtain a clear view of children's perspectives. The first author conducted stimulated recall interviews (Lyle Citation2003) twice through Zoom (recorded) as a little fairy in the middle and end of the CPW implementation. During the stimulated recall interview, video clips and pictures were used as prompts when interacting with children, and questions asked were based on the children's experiences. For example, the researcher asked children, ‘What is the role you played today? How did you find your seats in the submarine?’. As shown in , eight CPW sessions were conducted in this class based on The Snail and the Whale (Donaldson Citation2003). Among these, two CPW sessions that focused on mathematics (3rd and 4th CPW, 8.54 h of video observation data) and children's interview data (5.75 h of recorded children's interview data) were analysed in this paper.

Table 1. The data analysis process.

Data analysis

Drawing upon the wholeness child development model (Hedegaard Citation2012), this study adopted Hedegaard’s (Citation2008) three-level data interpretation protocols (see ). The data analysis is an iterative process, which allows a deeper understanding of how CPW created conditions for children's personally meaningful mathematical learning.

Findings

The CPW was based on the storybook The Snail and the Whale, which is about one little sea snail's adventure with a whale in the sea. Children and teachers collaboratively added new plots and characters (e.g. the land snail role was raised by children) to the original story and built up rich play narratives in their CPW imaginary adventures. In this study, we aimed to explore how this CPW created conditions for children's personally meaningful mathematical learning. Using the repeating pattern as an example, our analysis revealed the motivating conditions created by the CPW in supporting the focus child Zeng's personally meaningful learning of patterns. The findings illustrated (1) how Zeng built emotional connections within the collective imaginary situation and developed dominating motives of play, (2) how play narratives promote Zeng's meaning-giving motives of continuing adventure in the submarine, and (3) how Zeng was stimulated to solve a mathematical problem (stimulated motive) related to repeating patterns in play and develop his learning motives.

A dominating motive of play: building emotional connections with the character roles in the collective imaginary situation

This study found Zeng's dominating motive orientation to play appeared to be encouraged in the CPW. The selected vignette that follows was based on children's interests in helping the land snails go on adventures with sea snails in the previous CPW session. In this example, the teachers (Ms Li and Ms Han) played active roles as a submarine captain and a crew member respectively. They invited the children to choose to be either land snails or sea snails and select stickers and objects to represent their character roles. Ms Li told the children:

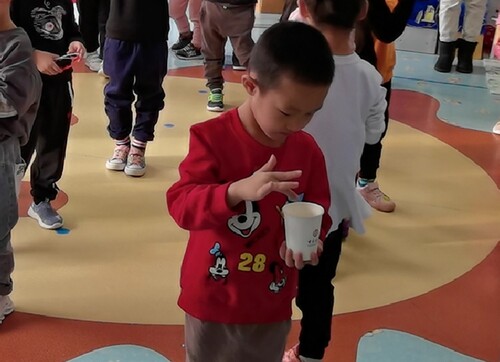

Sea snails love water, so I have prepared water (in paper cups) for sea snails. If sea snails feel dry, they can sprinkle some water onto their bodies. Also, this is the first time for the land snails to travel under the water, so I have prepared goggles for them in case they feel scared.

The CPW created conditions for children's play motives (dominating motives) development by providing all the children with opportunities to build a relationship with their play roles in the collective imaginary situation. Firstly, children got stickers (land snail stickers and sea snail stickers) and objects (goggles and water cups) in representing their roles, which helped them build close connections with the play characters. By selecting the role of a sea snail, Zeng got a sea snail sticker and a cup of water. While waiting for other children, Zeng sprinkled water on his head as if he was a sea snail suffering from body dryness (see ). This shows that Zeng built connections with the role, and behaved as a sea snail. Secondly, teachers’ active roles in the CPW helped create a collective imaginary situation, which promoted children's play development. For example, when Ms Li played the role of submarine captain, she put on her glasses and held a round plate, acting as if she was holding the steering wheel and operating the submarine. Later she invited all snails to enter the submarine (the sleeping room), with the sound ‘Gollum’, which was proposed by the children. This gave the foundation for imagining with more complexity in a mature form of imaginary play by promoting the movement between ‘individual imagining’ and ‘collective imagining’ (Fleer and Hedegaard Citation2010).

In the stimulated recall interview, when children were asked if the activities in CPW are the same as their regular group (mathematical) activities, the focus child Zeng said, ‘it is different, this (the CPW) is play, our regular activity is learning’. Chinese children distinguish play from non-play, where play is self-initiated, motivated and enjoyable (Wong, Wang, and Cheng Citation2011). By creating a collective imaginary situation and encouraging children to play character roles, the CPW aligns with children's dominating motives of play in the Chinese kindergarten context.

A meaning-giving motive of continuing adventure in the sea: building meaningful play narratives

The CPW play narratives were built by children and teachers (see ). In the previous CPW sessions (see , session ①②), children were prompted to find out that the land snail needs help under the sea and feels safe when staying with sea snails. Children as sea snails brainstormed how to help the land snail go on an adventure under the sea, such as taking a submarine. In this CPW (see , session ③), children received a message from a fairy, saying they can find a submarine on the beach. The teacher set up the problem in the situation that more land snails want to go on an adventure under the sea based on the ABB pattern. Building on children's understanding of the habitats of sea snails and land snails, as well as the emotional connection with the characters, Ms Li suggested one sea snail sitting with two land snails to protect the sea snails in their ocean adventure:

You all know that sea snails went into the water many times, but this is the first-time land snails go into the water. The land snails might feel nervous, so when you find a seat you should be mindful that one sea snail should stay with two land snails. In addition, the sea snail should sit in the first place, followed by two land snails.

Based on their previous experiences in helping the land snails and the new play narratives in this CPW, the sea snails developed sympathy for the land snails who have never gone underwater; in contrast, the land snails had a clear awareness that they needed to sit following a sea snail because they would be nervous during their first trip under the sea. Through exploring children's creative imagination in playworlds, Hakkarainen and Ferholt (Citation2013) argue that play is a sense-making activity. Since the play narrative was built based on children's ideas and interests and guided children in their play, the meaning-giving motives of continuing adventure in the sea and building play narratives made sense for them. For example, building on their previous understanding of the differences between land snails and sea snails, children built connections with their play roles and developed a personal sense of why one sea snail needs to sit with two land snails. As argued by Björklund and Pramling Samuelsson (Citation2013), the use of narrative means that the learning content was giving meaning within an interesting and familiar context. In this CPW, play narratives in which children were highly involved provided meaningful contexts for children to structure mathematical ideas. For example, when children as sea snails saw the land snail struggling underwater in the previous session, they tried to help and protect the land snail with different methods. The play problem (protecting land snails while having the adventure in the submarine) continued in this CPW session as a part of play narratives, where sitting following ‘one sea snail and two land snails’ is the solution.

A stimulating motive for solving dramatic problems: children's exploration of repeating patterns in play

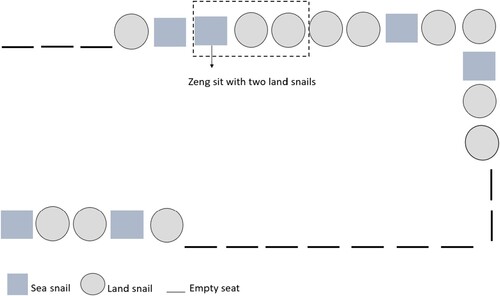

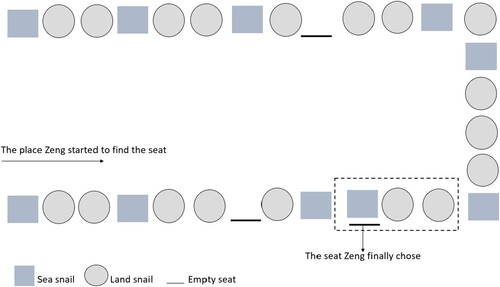

Chinese children do not have many opportunities to experience dramatic tensions in mathematical learning (Li, McFadden, and DeBey Citation2019). However, in this study, Ms Li raised a dramatic mathematical problem based on the narratives that children are highly involved. This was a play problem that required problem-solving based on the repeating pattern, finding seats following the ‘one sea snail and two land snails’ pattern. According to Lindqvist (Citation2003), adults need to dramatise the action to provide play with meaning. This dramatic problem provided a possible way to promote children's meaningful learning in repeating patterns. In this study, the focus child Zeng as a sea snail found two land snails, and then he held their hands to three empty seats and sat with them (see ). However, these two land snails went away with another sea snail. Therefore, Zeng had to search through the submarine, trying to find another seat. While walking, he met the captain who asked him, ‘did you find your two land snails?’. Zeng shook his head and said ‘no’. At this time, one sea snail reminded Zeng, ‘The submarine was about to start’. Since few seats were left at that time, Zeng had to search through the seats from the beginning (see ). He passed by the first empty seat, noticing that there was an empty seat before two land snails, so he quickly sat down (see ). When Ms Li (the captain) came to check if all the snails sit following the ‘one sea snail and two land snails’ pattern, Zeng said to her, ‘look, I am a sea snail, and these (on the right side) are two land snails who follow me’. Ms Li responded to Zeng, ‘great job, sea snail! You are in the right seat’. Ms Li then checked the seating pattern with all the children, they together said ‘one sea snail and two land snails’, ‘one sea snail and two land snails’ …

Children demonstrated different competencies in their problem-solving process, which was consistent with what the teacher aimed to achieve with children's pattern learning. In this process, Zeng appeared to actively solve this problem because his stimulating motive is to find two land snails and protect them during their adventure. According to , Zeng kept trying to sit before two land snails during the CPW session. Especially when he heard from another sea snail that the submarine was going to start up, his motive of protecting the land snails was further stimulated. This stimulates his motive orientation in solving the problem using the concept of repeating patterns before the submarine starts. We represent the moment in where Zeng chose one seat before two land snails, which was an illustration of Zeng's generalising of the unit of repeat. Zeng's pattern learning is meaningful because he attached personal senses to the rules and actions and demonstrated high involvement. For instance, Zeng tried hard to protect the two land snails and sit before them, and actively searched through the seats in the submarine during the whole session. Zeng's meaningful learning of repeating patterns was also shown in the child interview, where Zeng and his peers explained to the researcher ‘the land snail cannot live in the water … we sit in the submarine according to the one sea snail and two land snails.

Discussion

We found there is an interdependence between play motives and learning motives in the CPW, which promotes children's meaningful mathematical learning in the Chinese kindergarten context. Firstly, CPW provides motivating conditions for children's play motives development. For instance, Zeng was encouraged to role-play, build up narratives and make sense of play. Secondly, the stimulating motives of wanting to solve the play problem in this CPW supported Zeng's learning motives because he solved dramatic play problems using the concept of the repeating pattern, which allowed personally meaningful learning of mathematics.

Motivating conditions for mature play: developing children's play motives in a meaningful way

Since many teaching sessions in Chinese kindergartens frequently consist of teacher-directed play-oriented activities where teachers either lead play or organise activities in a playful manner, and many children do not have a lot of opportunities to develop their play motives in group teaching (Wu Citation2019). Therefore, there is a need to promote Chinese children's role in play and shared control in mathematical learning. In the CPW, children are given some degree of freedom to role-play, co-construct and follow imaginary rules within the imaginary situation (Ma et al. Citation2022). For example, acting ‘as if’ a sea snail, Zeng was given the freedom to follow and co-construct the rules in the imaginary play. This is shown when Zeng was involved in play as a sea snail sprinkling water on his head and trying to sit with land snails and protect them. In this way, the dominating motive of play developed, as the focus child Zeng played the role of a sea snail and interacted with other characters within the collective imaginary play.

As argued by van Oers (Citation2012a), the process of personal meaning-making starts with children's involvement in cultural practices which make personal sense to them, and in which they want to participate. By providing collective imaginary situations and meaningful narratives, the CPW engaged children and developed their meaning-giving motives, such as going on an adventure and finding a seat in the submarine. This corresponds to Fleer’s (Citation2012) argument that children are more likely to develop play motives when the activity is motivating and connected to their interests and experiences. In this way, children's dominating motive of play could be regarded as a meaning-giving motive because they were able to build play narratives which make sense to them.

Involved in the collective imaginary play, children were stimulated to find seats in the submarine because the land snail would feel unsafe underwater. Therefore, children have a clear consciousness that one sea snail should sit with two land snails and protect them in their ocean adventure. When Zeng tried to find a seat following the play rules, the stimulating motive motivated his problem-solving using the ABB repeating pattern (see ), which further promoted the meaningful learning of patterns for him. Although children thought they were playing in the submarine, they were involved in fixing the pattern with a conscious awareness of the unit of repeat (Lüken and Sauzet Citation2021). When Zeng told the teacher ‘these are two land snails following me’, he appeared to develop an understanding of the unit of repeat (one sea snail and two land snails). In summary, CPW appears to promote children's play motives development as shown in Zeng's experiences, which includes role-playing as snails (dominating motive), building play narratives (meaning-giving motive) and finding seats as snails following the pattern (stimulating motive). This helps explain, as Li and Disney (Citation2021) originally identified, how character roles helped children build emotional connections, dramatise the problem and develop stimulating motives. In this study, we go one step further by exploring how children's dominating, meaning-giving and stimulating motives development create conditions for children's learning motives in a personally meaningful way within the Chinese kindergarten context.

Stimulating children's learning motives: promoting children's personally meaningful mathematical learning

From a cultural-historical perspective, learning is not a linear process, but a spiral process of thinking and problem-solving (Li and Disney Citation2021). When children are stimulated to solve a dramatic mathematical problem in play, their learning was motivated by their play motives. To be specific, the dramatic play inquiries helped children explore repeating patterns in a personally meaningful way, which can be seen from the focus child Zeng fixing the pattern and developing learning motives in the imaginary play. This allows children to pay attention to the surface features as well as the overall structure of the pattern as the problem emphasises the unit of repeat (Wijns et al. Citation2019). The most fundamental problem of mathematics education in China is that activities do not make sense to children (Hu et al. Citation2017). In this CPW, the problem dramatisation was based on play narratives (travelling by submarine under the sea) that children find fascinating, which is why they can comprehend what has occurred (Lindqvist Citation2003). In acting out the characters in the storybook (as if they were land snails and sea snails), children were motivated to solve conceptual problems following the repeating pattern, which promotes their learning based on their play motives. Therefore, children are able to achieve personally meaningful mathematical learning.

Different from previous studies which explored children's repeating patterns through asking children to operate materials (Lüken and Sauzet Citation2021; Tsamir et al. Citation2020), this study discussed Zeng's repeating pattern learning in a collective imaginary situation. In contrast to traditional Chinese mathematical learning where repeated exercises were emphasised (Dai and Cheung Citation2015), this study emphasised Zeng's active problem-solving process and personally meaningful learning in repeating patterns. When Zeng showed Ms Li that he was sitting with two land snails, it could be seen that he had successfully solved the problem with the unit of repeat in mind. Therefore, when the problem scenario was introduced with drama, imagination, and meaningful narratives, it became possible for Chinese children to engage with mathematical concepts for expanding their play. Through analysing Zeng's experience in this CPW, we found that the stimulating motives of solving the play problem can motivate children's learning motives, which created conditions for Chinese children's personally meaningful mathematical learning. In summary, the CPW also provided a possible solution to the problem raised by Hu et al. (Citation2017) when they argued mathematical lessons in Chinese kindergartens lack critical moments in children's meaning-making.

Conclusion

While the call for high-quality experiences in early childhood mathematics is not new, this study provides motivating conditions through an educational experiment for Chinese children's meaningful mathematical learning in the repeating pattern. From a cultural-historical perspective, mathematics should be embedded in meaningful contexts (Dijk, van Oers, and Terwel Citation2004). However, it is widely known that schools tend to focus on the transmission of codified cultural meanings (disciplinary knowledge) while ignoring the personal sense such knowledge may have for the students (van Oers Citation2012b). Especially in the Chinese context where content knowledge and teacher authority have been emphasised for a long period (Faas, Wu, and Geiger Citation2017). A possible solution to this phenomenon is that children and teachers go in and out of play, imagining ‘as if’ in the imaginary situation and reflecting on the real world, while teachers in their elaborations conceptually develop the mutual play frame (Pramling et al. Citation2019). The CPW model provided a creative solution to promote Chinese children's meaningful learning of mathematics through intervolving mathematical problem-solving into children's play. By illustrating children's meaningful repeating pattern problem-solving in play, this study offered a possible way for children's meaningful mathematical learning in areas other than calculation and counting in the Chinese kindergarten context. In addition, this study contributed to expanding what is known about meaningful mathematical learning.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Special thanks to the participating teachers and children as well as the kindergarten where this study was conducted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Björklund, C. 2016. “Playing with Patterns: Conclusions from a Learning Study with Toddlers.” In Mathematics Education in the Early Years, edited by T. Meaney, O. Helenius, M. L. Johansson, T. Lange, and A. Wernberg, 269–287. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Björklund, C., and I. Pramling Samuelsson. 2013. “Challenges of Teaching Mathematics Within the Frame of a Story - a Case Study.” Early Child Development and Care 183 (9): 1339–1354. doi:10.1080/03004430.2012.728593.

- Bodrova, E. 2008. “Make-Believe Play Versus Academic Skills: A Vygotskian Approach to Today’s Dilemma of Early Childhood Education.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 16 (3): 357–369. doi:10.1080/13502930802291777.

- Bodrova, E., and D. J. Leong. 2015. “Adult Influences on Play: The Vygotskian Approach.” In Play from Birth to Twelve, edited by Doris Pronin Fromberg, and D. Bergen, 187–194. New York: Routledge.

- Bojorque, G., N. Gonzales, N. Wijns, L. Verschaffel, and J. Torbeyns. 2021. “Ecuadorian Children’s Repeating Patterning Abilities and Its Association with Early Mathematical Abilities.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 36 (4): 945–964. doi:10.1007/s10212-020-00510-4.

- Broström, S. 2017. “A Dynamic Learning Concept in Early Years’ Education: A Possible Way to Prevent Schoolification.” International Journal of Early Years Education 25 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1080/09669760.2016.1270196

- Dai, Q., and K. L. Cheung. 2015. “The Wisdom of Traditional Mathematical Teaching in China.” In How Chinese Teach Mathematics: Perspectives from Insiders, edited by L. Fan, N.-Y. Wong, J. Cai, and S. Li, 3–42. Singapore: World Scientific.

- Derman, T. M., Ş. E. Zeteroğlu, and E. A. Birgül. 2020. “The Effect of Play-Based Math Activities on Different Areas of Development in Children 48 to 60 Months of Age.” SAGE Open 10 (2), 215824402091953. doi:10.1177/2158244020919531.

- Dijk, E. F., B. van Oers, and J. Terwel. 2004. “Schematising in Early Childhood Mathematics Education: Why, When and How?” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 12 (1): 71–83. doi:10.1080/13502930485209321.

- Donaldson, J. 2003. The Snail and the Whale. London: Macmillan.

- Elkonin, D. B. 1999. “Toward the Problem of Stages in the Mental Development of Children.” Journal of Russian and East European Psychology 37 (6): 11–30. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405370611.

- Faas, S., S. Wu, and S. Geiger. 2017. “The Importance of Play in Early Childhood Education: A Critical Perspective on Current Policies and Practices in Germany and Hong Kong.” Global Education Review 4 (2): 75–91. https://ger.mercy.edu/index.php/ger/article/view/348.

- Fleer, M. 2012. “The Development of Motives in Children’s Play.” In Motives in Children’s Development: Cultural-Historical Approaches, edited by M. Hedegaard, A. Edwards, and M. Fleer, 79–96. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Fleer, M. 2014. “The Demands and Motives Afforded Through Digital Play in Early Childhood Activity Settings.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 3 (3): 202–209. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.02.012.

- Fleer, M. 2019. “Conceptual Playworlds as a Pedagogical Intervention: Supporting the Learning and Development of the Preschool Child in Play-Based Setting.” Obutchénie: Revista De Didática E Psicologia Pedagógica 3 (3): 1–22. doi:10.14393/OBv3n3.a2019-51704.

- Fleer, M. 2020. “Studying the Relations Between Motives and Motivation – How Young Children Develop a Motive Orientation for Collective Engineering Play.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 24, 100355. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100355.

- Fleer, M. 2021a. “Conceptual Playworlds: The Role of Imagination in Play and Learning.” Early Years 41 (4): 353–364. doi:10.1080/09575146.2018.1549024.

- Fleer, M. 2021b. “How an Educational Experiment Creates Motivating Conditions for Children to Role-Play a Child-Initiated Playworld.” Oxford Review of Education 48 (3): 1–16. doi:10.1080/03054985.2021.1988911.

- Fleer, M., and M. Hedegaard. 2010. Early Learning and Development Cultural-Historical Concepts in Play. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hakkarainen, P., and B. Ferholt. 2013. “Creative Imagination in Play-Worlds: Wonder-Full Early Childhood Education in Finland and the United States.” In Wonder-Full Education, edited by K. Egan, A. Cant, and G. Judson, 211–226. Routledge.

- Hedegaard, M. 2002. Learning and Child Development: A Cultural-Historical Study. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press.

- Hedegaard, M. 2008. “Principles for Interpreting Research Protocols.” In Studying Children: A Cultural-Historical Approach, edited by M. Hedegaard, M. Fleer, J. Bang, and P. Hviid, 46–64. New York: Open University Press.

- Hedegaard, M. 2012. “Analyzing Children's Learning and Development in Everyday Settings from a Cultural-Historical Wholeness Approach.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 19 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1080/10749039.2012.665560.

- Hu, B. Y., S. Quebec Fuentes, J. Ma, F. Ye, and S. K. Roberts. 2017. “An Examination of the Implementation of Mathematics Lessons in a Chinese Kindergarten Classroom in the Setting of Standards Reform.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 31 (1): 53–70. doi:10.1080/02568543.2016.1244581.

- Li, L., and L. Disney. 2021. “Young Children’s Mathematical Problem Solving and Thinking in a Playworld.” Mathematics Education Research Journal, 35 (1), 23–44. doi:10.1007/s13394-021-00373-y.

- Li, X., S. Liu, M. DeBey, K. McFadden, and Y.-J. Pan. 2018. “Investigating Chinese Preschool Teachers’ Beliefs in Mathematics Teaching from a Cross-Cultural Perspective.” Early Years 38 (1): 86–101. doi:10.1080/09575146.2016.1228615.

- Li, X., K. McFadden, and M. DeBey. 2019. “Is It Dap? American Preschool Teachers’ Views on the Developmental Appropriateness of a Preschool Math Lesson from China.” Early Education and Development 30 (6): 765–787. doi:10.1080/10409289.2019.1599094.

- Lillard, A. S., M. D. Lerner, E. J. Hopkins, R. A. Dore, E. D. Smith, and C. M. Palmquist. 2013. “The Impact of Pretend Play on Children's Development: A Review of the Evidence.” Psychological Bulletin 139 (1): 1. doi:10.1037/a0029321.

- Lindqvist, G. 1995. “The Aesthetics of Play: A Didactic Study of Play and Culture in Preschools." Doctoral thesis, Uppsala University.

- Lindqvist, G. 2003. “The Dramatic and Narrative Patterns of Play.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 11 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1080/13502930385209071.

- Lüken, M. M. 2020. “Patterning as a Mathematical Activity: An Analysis of Young Children’s Strategies When Working with Repeating Patterns.” In Mathematics Education in the Early Years, edited by Martin Carlsen, Ingvald Erfjord, and P. S. Hundeland, 79–92. Cham: Springer.

- Lüken, M. M., and O. Sauzet. 2021. “Patterning Strategies in Early Childhood: A Mixed Methods Study Examining 3-to 5-Year-Old Children’s Patterning Competencies.” Mathematical Thinking and Learning 23 (1): 28–48. doi:10.1080/10986065.2020.1719452.

- Lyle, J. 2003. “Stimulated Recall: A Report on Its Use in Naturalistic Research.” British Educational Research Journal 29 (6): 861–878. doi:10.1080/0141192032000137349.

- Ma, Y., Y. Wang, M. Fleer, and L. Li. 2022. “Promoting Chinese Children's Agency in Science Learning: Conceptual Playworld as a New Play Practice.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 33: 100614. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2022.100614.

- Miller, M. R., B. Rittle-Johnson, A. M. Loehr, and E. R. Fyfe. 2016. “The Influence of Relational Knowledge and Executive Function on Preschoolers’ Repeating Pattern Knowledge.” Journal of Cognition and Development 17 (1): 85–104. doi:10.1080/15248372.2015.1023307.

- Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. 2012. 3-6岁儿童学习与发展指南[Early Learning and Development Guidelines for Children Aged 3-6]. People's Republic of China.

- Papandreou, M., and Z. Konstantinidou. 2020. “‘We Make Stories One Meter Long’: Children’s Participation and Meaningful Mathematical Learning in Early Childhood Education.” Review of Science, Mathematics and ICT Education 14 (2): 43–64. doi:10.26220/rev.3511.

- Pramling, N., C. Wallerstedt, P. Lagerlöf, C. Björklund, A. Kultti, H. Palmér, M. Magnusson, S. Thulin, A. Jonsson, and I. Pramling Samuelsson. 2019. Play-Responsive Teaching in Early Childhood Education. Cham: Springer.

- Qi, X., and E. C. Melhuish. 2017. “Early Childhood Education and Care in China: History, Current Trends and Challenges.” Early Years (London, England) 37 (3): 268–284. doi:10.1080/09575146.2016.1236780.

- Rittle-Johnson, B., E. R. Fyfe, A. M. Loehr, and M. R. Miller. 2015. “Beyond Numeracy in Preschool: Adding Patterns to the Equation.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 31: 101–112. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.01.005.

- Rittle-Johnson, B., E. L. Zippert, and K. L. Boice. 2019. “The Roles of Patterning and Spatial Skills in Early Mathematics Development.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 46: 166–178. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.03.006.

- Smith, P. K. 2017. “Pretend Play and Children’s Cognitive and Literacy Development: Sources of Evidence and Some Lessons from the Past.” In Play and Literacy in Early Childhood Research from Multiple Perspectives, edited by K. A. Roskos and J. F. Christie, 3–20. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Tsamir, P., D. Tirosh, R. Barkai, and E. Levenson. 2020. “Copying and Comparing Repeating Patterns: Children’s Strategies and Descriptions.” In Mathematics Education in the Early Years, edited by Martin Carlsen, I. Erfjord, and P. S. Hundeland, 63–78. Cham: Springer.

- van Oers, B. 2010. “Emergent Mathematical Thinking in the Context of Play.” Educational Studies in Mathematics 74 (1): 23–37. doi:10.1007/s10649-009-9225-x.

- van Oers, B. 2012a. “Developmental Education: Foundations of a Play-Based Curriculum.” In Developmental Education for Young Children: Concept, Practice and Implementation, edited by B. van Oers, 13–25. Dordrecht: Springer.

- van Oers, B. 2012b. “Meaningful Cultural Learning by Imitative Participation: The Case of Abstract Thinking in Primary School.” Human Development 55 (3): 136–158. doi:10.1159/000339293.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1966. “Play and Its Role in the Mental Development of the Child.” Voprosy Psikhologii 12 (6): 62–76. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-040505036.

- Wang, Y., K. Qin, C. Luo, T. Yang, and T. Xin. 2022. “Profiles of Chinese Mathematics Teachers’ Teaching Beliefs and Their Effects on Students’ Achievement.” ZDM–Mathematics Education, 54, 1–12. doi:10.1007/s11858-022-01353-7.

- Weisberg, D. S. 2015. “Pretend Play.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 6 (3): 249–261. doi:10.1002/wcs.1341.

- Weng, J., H. He, Y. Xue, M. Guo, and C. Wu. 2022. “Chinese Preschoolers’ Pattern Creation: Performance and Predictors.” Early Education and Development, 1–21. doi:10.1080/10409289.2022.2148320.

- Wijns, N., J. Torbeyns, B. De Smedt, and L. Verschaffel. 2019. “Young Children’s Patterning Competencies and Mathematical Development: A Review.” In Mathematical Learning and Cognition in Early Childhood: Integrating Interdisciplinary Research Into Practice, edited by K. M. Robinson, H. P. Osana, and D. Kotsopoulos, 139–161. Cham: Springer.

- Wong, S.-m., Z. Wang, and D. Cheng. 2011. “A Play-Based Curriculum: Hong Kong Children's Perception of Play and Non-Play.” International Journal of Learning 17 (10), 165–180. doi:10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v17i10/47298.

- Worthington, M., and B. van Oers. 2016. “Pretend Play and the Cultural Foundations of Mathematics.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 24 (1): 51–66. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2015.1120520.

- Wu, S. C. 2019. “Teachers’ Involvement in Their Designed Play Activities in a Chinese Context.” In Globalization, Transformation, and Cultures in Early Childhood Education and Care, edited by S. Faas, D. Kasüschke, E. Nitecki, M. Urban, and H. Wasmuth, 221–234. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Yang, W., and H. Li. 2018. “A School-Based Fusion of East and West: A Case Study of Modern Curriculum Innovations in a Chinese Kindergarten.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 50 (1): 17–37. doi:10.1080/00220272.2017.1294710.

- Yang, W., H. Luo, and Y. Zeng. 2022. “A Video-Based Approach to Investigating Intentional Teaching of Mathematics in Chinese Kindergartens.” Teaching and Teacher Education 114: 103716. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2022.103716.