ABSTRACT

This article demonstrates how implementing a rights-based research methodology can contribute to the theory and practice of climate change research and education with young children. The argument stems from a child rights-based participatory study that sought to explore young children’s own perspectives of Nature under the education right, Article 29 1 (e) of the UNCRC. The study took place over nine-months in an early childhood setting in Ireland. It illustrated that with the necessary resources (time, flexibility in research agenda and a listening adult) children define their own education and participatory rights. Drawing on these insights, and integrating scholarship from children’s rights, early childhood pedagogy, and education for sustainable development (ESD), this article advocates for a methodological approach to climate research and education that foregrounds children’s agency. I argue that children must be positioned as rights-holders within their educational settings and have their views heard and included in curriculum making. I also argue, in virtue of listening within it, that early childhood (EC) pedagogy mutually reinforces authentic child participation. I offer seven key strategies designed with the participants that could be adopted by practitioners wishing to engage in a child rights-based ESD approach; creating a meaningful listening environment, reconceptualising the term ‘expertise knowledge’, taking time for ongoing reflexivity, maintaining an ‘ethical radar’, understanding each other, ensuring meaningful participation, and balancing power dynamics.

Introduction

Although the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) was ratified to protect and promote the human rights of children, it has been critiqued for its universality and failure to accommodate diverse contexts and experiences. Robson (Citation2016) and Lundy and Martínez Sainz (Citation2018) suggest that a ‘top down’, policy-to-practice approach to implementing children’s rights is restrictive and argue for its reframing to better serve children’s living realities. This article presents research which challenges a ‘top down’ approach to the realisation of children’s rights and provides a detailed account of the complexities of child rights-based research as it relates to education for sustainable development (ESD) in early childhood education and care (ECEC). There are two key arguments presented. Firstly, that ESD in ECEC must be consistent with the CRC and requires a child rights-based participatory approach at local level. Secondly, as an ECEC practitioner myself with over 20 years’ experience, that ECEC pedagogy has many aspects that are mutually reinforcing with authentic child rights-based participatory ESD.

In the following section I discuss sustainability as a concept. I then analyse the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UNDP Citation2015) and explain how ESD in early childhood has evolved both internationally and in Ireland, since 2000. The rest of the article details how rights-based research was implemented in a local context, contributing to the literature gap on how to undertake such research with very young children. I discuss a number of my own researcher strategies, informed by the children and developed to support their involvement with data collection and analysis, that were in keeping with their participatory rights. I also present the methodology to argue that ECEC is a fertile site for promoting a rights-based ESD approach. By engaging with young children and how they chose to enjoy their participatory and education rights, the study showed how children can be empowered to provide their own definitions of their rights. This is especially important given that children did not contribute to the original drafting of the CRC itself.

Sustainability as a multi-faceted concept

Sustainability has been described as an ever-evolving value-laden concept with many different meanings (Pramling Samuelsson and Kaga Citation2008; Croft Citation2017). Siraj-Blatchford et al., (Citation2010) describes interdependent pillars of sustainability: natural, economic, social and cultural and political. This multi-pillar understanding of sustainability is evident in the 2030 Global Agenda which was adopted in 2015 by all United Nations (UN) member states. The agenda saw the establishment of the SDGs (UNDP Citation2015), described by UNESCO as a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all. Yet, despite the commitment to such a multi-faceted understanding, poverty, violence, neglect, mental health illnesses, and unthinkable inequalities remain living childhood realities the world over (Lundy and Martínez Sainz Citation2018). We have been in this position before when world leaders committed to the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (UNMDG) (UNDP Citation2000), including environmental sustainability and universal primary education, in 2000. However, another stronger blueprint had already been in existence since 1989. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) holds state governments legally accountable for these inequalities. Without a full integration of the legally binding nature of children’s rights, Nolan and McGrath (Citation2016) and Nolan (Citation2020), argue the SDGs will not be reached. Waldron et al. (Citation2020) and Moss and Roberts-Holmes (Citation2022) also underline that as long as education policies are economically driven, the suffering that sustainable inequality brings will continue to exist. While education is being positioned as pivotal to combat the climate crisis, this article starts from the premise that how each learner is positioned as a human rights holder within that education is critical.

The role of early education in ESD promotion

The UNESCO report Educating for a sustainable future (Citation1997) underline education as the most effective means to integrate child rights into the SDGs in achieving sustainable development. All forms of education start with early education whose integral position within ESD was advanced firstly in the UNESCO report, The contribution of early childhood education to a sustainable society (Citation2008) and the subsequent OMEP (Organisation Mondiale pour l’Éducation) report, Education for sustainable development in the early years (Citation2010). Both reports discuss the importance of implementing the CRC properly and of positioning the young child as a rights holder within their education spaces. This highlights the need to think seriously about how ESD can be applied in diverse cultural contexts. Davies (Citation2009, Citation2014) also emphasise that translating ESD to early childhood praxis is challenging and requires responsive sensitive pedagogy. They stress that ESD is not just environmental education nor is ESD just a case of bringing young children outdoors to discover the beauty of Nature. Instead, it requires an approach that starts by listening to children’s perspectives and including them in making an ESD curriculum that is authentic and has meaning to their everyday lives.

In recent years, there has been a growing literature examining how ECEC in general can be transformed to ensure it is more child rights-based (Moody and Darbellay Citation2019; Zanatta and Long Citation2021). From a pedagogical perspective, Lyndon et al. (Citation2019) Wall and Robinson (Citation2019), Clark (Citation2022), illustrate how relational, responsive, and slowing down approaches within learning spaces could also support this child rights-based approach. Particular to ESD promotion, Hirst (Citation2019) and Spiteri (Citation2021) argue that the assumed complexities of climate action can be mitigated through intergenerational learning between child, practitioner, and families. Luff (Citation2018), Boyd (Citation2018) and Boardman (Citation2022) connect early education theory with how to make a more democratic learning environment. These authors recommend creating learning opportunities that encompass young children’s own participation and perspectives as a means of embedding democratic values into early childhood spaces. Such perspectives support my second argument that early childhood pedagogy contains elements conducive to promoting effective participatory ESD.

Children’s participatory rights within the SDGs

At this point, it is necessary to explore how early childhood participation is currently positioned within the SDGs themselves. From a rights perspective, the SDGs are explicitly grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and international human rights treaties, including the CRC. However, while the SDGs serve as a ‘crucial contemporary impetus’ for child rights discourses and, if implemented effectively, could advance rights, their associated implementation processes pose child rights challenges (Nolan Citation2020, 14). Firstly, the CRC is not integrated into or across the SDGs and, overall, non-enforceable development goals are not legally binding in the sense that rights are. Secondly, Nolan and McGrath (Citation2016) also question the narrowness of the indicators to monitor implementation and ensure accountability, which, they argue, are neither child rights sensitive nor compliant. They call for the addition of qualitative measures. Finally, while child participation is an element of the work of the United Nations High-Level Panel Forum on Sustainable Development (the HLPF), which is charged with reviewing the 2030 Agenda at global level, there are limitations to its meaningful implementation in this context. Notably, the parameters of the body responsible for managing child participation, the United Nations Major Group for Children and Youth (MGCYP), are unclear and problematic under Article 12 (the specific provision concerning the child’s right to participation). Particularly concerning from an early childhood rights perspective is the MCCYP’s scope which applies to people under 30 and not children under 18 – the age cohort covered by the CRC – causing a lack of clarity on the participation of different age levels (Nolan Citation2020).

ESD policy and early childhood in Ireland: tensions and limitations

Ireland ratified the UNCRC in 1992 but is yet to be fully incorporated into domestic law (Forde and Kilkelly Citation2021). As a curriculum entitlement, providing children with an education that supports a respect for Nature is specified in Article 29 1 (e) of the UNCRC as follows,

Article 29

States Parties agree that the education of the child shall be directed to:

The development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential;

The development of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and for the principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations;

The development of respect for the child’s parents, his or her own cultural identity, language and values, for the national values of the country in which the child is living, the country from which he or she may originate, and for civilisations different from his or her own;

The preparation of the child for responsible life in a free society, in the spirit of understanding, peace, tolerance, equality of sexes, and friendship among all peoples, ethnic, national and religious groups and persons of indigenous origin;

The development of respect for the natural environment.

No part of the present article or article 28 shall be construed so as to interfere with the liberty of individuals and bodies to establish and direct educational institutions, subject always to the observance of the principle set forth in paragraph 1 of the present article and to the requirements that the education given in such institutions shall conform to such minimum standards as may be laid down by the State. (UNCRC Citation1989, 9)

However, despite the prominent role early childhood education has to play in climate action, and although the Irish government has considered it ‘our national opportunity’ to be ‘in the forefront’ of promoting ESD in the sector (DES Citation2014, 12), ECEC in Ireland remains underdeveloped and under resourced (CRA Citation2021; ECI Citation2021). A further limitation of Ireland’s approach to ESD is that it has been promoted in primary, secondary and third-level educational settings, but not in ECEC. This is problematic because under Article 2, rights must be observed ‘without discrimination of any kind’ (UNCRC Citation1989, 2). This omission also raises questions under Article 4 which directs state parties to ‘undertake all appropriate legislative, administrative, and other measures for the implementation of rights recognised in the present Convention’ (UNCRC Citation1989, 2).

The Irish government is currently promoting the development of a dialogue strategy as part of a national Climate Action Plan (2021) that ensures ‘all voices will be heard in a fair and equal manner’. The Participation Framework from the department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth (DCEDIY) also commits to ‘listening to children and young people and giving them a voice in decision-making’ (Citation2021, 17). The second national strategy ESD to 2030 published in 2022 also emphasises children’s participatory rights and highlights ‘a need for mechanisms to ensure the voices of children … are heard clearly and consistently’ in furthering the ESD agenda (GOI Citation2022, 16). It acknowledges that the commitment to collaborate with children in the original national ESD strategy did not progress for ‘a number of reasons’ and reaffirms this as an impending action (GOI Citation2022, 18).

These tensions provide a rationale for examining how we can include our youngest contributing rights holders within ESD discourse. The research study found that through collaborating with young children to explore what their own perspectives are of Nature advances an ESD approach that is respectful of children’s education and participatory rights under Article 29 1 (e). This provides evidence for my first argument of the necessity to position children as rightsholders within their educational spaces and of listening to their views to include in curriculum making. How I listened, leads to my second argument that early childhood pedagogy mutually reinforces authentic child participation. I use the rest of the article to describe how I built a participatory child rights-based research methodology with my participants based on these two points.

Building a participatory child rights-based methodology

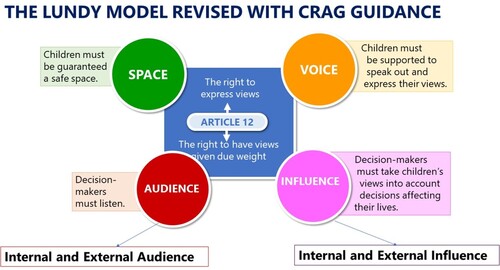

Following a child rights-based research approach, the study took much of its guidance from the Lundy model, a child rights-based model of research participation (Lundy Citation2007). Lundy illustrates four core features: space, voice, audience, and influence as essential for a fuller realisation of participatory rights. It was also used to underpin the principles of participation within The Participation Framework (DCEDIY Citation2021) mentioned above. There are three core principles to this rights-based approach: the study should further advance the realisation of rights; children’s rights standards should guide all research stages, and the capacity of duty bearers to meet their obligations and rights holders to claim their rights, is supported (Lundy and McEvoy Citation2011, Citation2012). This means that research aims and processes must be informed and comply with all CRC standards and be grounded in dignity, profound moral respect, and entitlements of children as bearers of human rights.

A distinctive feature of this approach is the use of a Children’s Research Advisory Group (CRAG) (Lundy, McEvoy, and Byrne Citation2011; Lundy et al. Citation2021; Collins et al. Citation2020). CRAG members are invited to take an advisory role to inform the thinking of the adult researcher through their input on each research stage. Advice may include how to formulate research questions, design suitable research methods or data gathering tools, and analyse and disseminate findings. The participants were invited to take part in each of the stages and comprised two groups:

The Children’s Research Advisory Group (CRAG) (3–5year olds)

Recruitment criteria for this group included their closeness in age (3–5 years) to that of the research participants (2–3 years), the fact that they had already spent a year in the preschool, and their existing knowledge such as insight into the local culture of the setting. That and their own approaches to Nature learning positioned them as experts in an advisory role to support the project. The group was involved in the design of the methodology, data collection and analysis and dissemination.

(2) Young research participant group (2–3year olds)

This group consisted of younger children (2–3 years) who had just started the preschool year for their first time. They were invited to engage in interactive participatory methods during the data collection phase to share their perspectives of Nature. They were also involved with the dissemination of research results.

The study took place over three phases in 2019/2020. Ethical approval was given by the Research Ethics Committee, South East Technological University.

The role of ongoing reflexivity to support meaningful participation

The following section concentrates on the central role of reflexivity that supported me as the adult listener and researcher in my commitment to authentic child participation throughout each of the research stages. I begin by explaining the necessity to create a meaningful listening space and how that was informed by the CRAG. This is continued by a discussion on reconceptualising the term ‘expert knowledge’ which emerged during time spent from self-reflection on my part that I recognised as being a potential barrier for an inclusive research approach. The rest of the section speaks about the actual layers of reflection with which I contented on an ongoing basis. I also present this in a visual form to highlight the complexity of thought that was there. Both the discussion and the visual are offered as a means to name the intricate nature of reflexivity in supporting child participation and as a guide of how to attend to this. This analysis also grounds the main bulk of my second argument, that early childhood pedagogy mutually reinforces authentic and meaningful participation.

Creating a meaningful listening environment

During the first research design workshop, I asked the CRAG, ‘What do you like about Nature?’ When the reply was ‘unicorns’, I was aghast. Other suggestions included spiders, flowers, and puppies but I do remember having a flash of judgement as to how the planet would have any chance of survival when Disney was infiltrating the minds of our children. The participant went on to describe how cute unicorns were and how much they loved them and wanted to hug them all day long. All I could think was ‘they don’t even exist!’. At our next session, I arrived with a car full of loose parts and a commitment to create fabulous unicorns for an open-ended arts-based session exploring what young children would choose to put in outdoor spaces. Unicorns did not make an appearance but flowers, ladybirds, clouds, worms, trees, spaces for cycling and a giant minion did.

Another session, in which the group were invited to consider how they would like to design outdoor spaces, included a suggestion to build a McDonalds – an idea which was met with heartfelt peer agreement. I held my breath. But I was reminded of Parry’s (Citation2015) and Klitgaard Povlsen et al.’s (Citation2021) warning that research methods are not simply a means of ‘getting inside’ children’s heads. Rather they add value as an integrated process of co-constructing knowledge informed by participants’ cultural, social, and creative contexts. As Fane et al. (Citation2018) have argued, the onus was on me to make peace with fictional characters and fast-food chains and to make space for them to be included in the research dialogue to better support the young participants to form their own views. Roa et al. (Citation2018) emphasise that learning how to listen to young children is complex. While we were only at the design stages and deciding on the most salient research tools, I could identify this as guidance coming from the CRAG members as to what kind of listening environment would better support their engagement. It was not simply a case of me just listening to identify areas of learning for sustainability. Instead, I was guided on how I should listen to them full stop.

Reconceptualising ‘expertise’: using ‘unicorn moments’

Working with the CRAG also provided me with a deeper understanding of what it means to consider children as experts in their own lives. I learnt how to respect their expertise without judgement, thereby better ensuring a rights respecting space (Collins et al. Citation2020; Roa et al. Citation2018). As a result I created a new strategy in my head that I called ‘unicorn moments’ which contained my need to tidy this fastpace research space and my adultist rebuke (Ceballos and Susinos Citation2022). Each time that I did not understand or judged a child’s idea, I learned to internally categorise it as a ‘unicorn moment’. Doing this alerted me to another form of knowledge being shared that needed more time to process. The children were sharing knowledge of their own lives that was different from mine and I was learning that I should be taking this seriously. This reflected how the CRAG were again guiding what my adult listening role should be in their world. From a practical perspective, this took the form of storytelling on their part. I made plenty of time to listen to different stories from their lives that they chose to share; (how Granny killed a spider with her slipper, how Daddy got a nail stuck in his foot or how one participant made a butterfly card for Grandad). It was a combination of these two contributions from the CRAG, that ultimately heightened my understanding of the essential role of reflexivity in the research process (Lyndon et al. Citation2019; Johnston Citation2021).

Making time for reflexivity

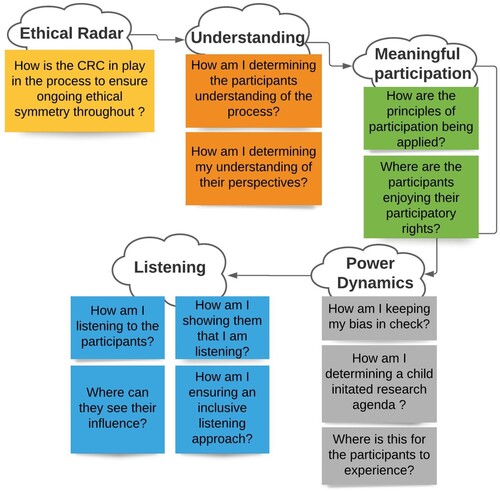

The value of reflective practice is a widely acknowledged principle in early childhood curricula frameworks (NCCA Citation2009, Citation2015). Initially, I was not fully aware of the level of reflexivity required in the research, or the multiple layers I needed to contend with as an ongoing process (Long Citation2021). Indeed, it was the most helpful strategy for developing my own confidence in keeping the research grounded in the participants’ perspectives. offers a tidied-up version of the role of reflexivity in the study. I will now explore these layers individually to demonstrate how I developed a reflective checklist of sorts for ensuring a rights-based approach within everyday early childhood contexts (Alderson Citation2012).

Maintaining an ‘ethical radar’

Merely following standard research ethical principles is not enough when researching with young children. Instead, researchers need to have an ‘ethical radar’ (Skånfors Citation2009) on high alert throughout the process to capture possible ethical issues arising from everyday complexities (Wall and Robinson Citation2022). That might include how a child understands or engages with a particular idea or it may relate to an emotional response, such as becoming upset or afraid, which may not be possible for the researcher to pre-empt. demonstrates how I considered such events with my own form of ‘ethical radar’. This was on full alert while I was both on site working alongside the children and later when I was considering by myself what took place during the workshops. A prime consideration in this regard was monitoring how the children and I were understanding one another.

The role of understanding

This study recognises that multiple realities and understandings exist as to how young children engage with Nature. Bruner (Citation1996) argues that how any one of us understands anything can only really be understood by ourselves. He describes the existence of an intersubjective space between individuals in which they negotiate new meaning. Engaging in this space to establish what is being understood by everyone is pivotal for supporting both learning and capacity building (Huser, Dockett, and Perry Citation2022). Mayne, Howitt, and Rennie (Citation2017) ‘Early Childhood Rights-Based Research Reinforcing Cycle’ proved particularly useful in monitoring what was being understood by me and the young participants. The value of this cyclical model is that it represents how the quality of overall child participation stems from the quality of the strategies used to establish how understanding has been achieved.

Taking the time for meaningful participation

The quality of participation also stems from the quality of informing the child. This means keeping the child fully informed in an authentic manner of what is happening or what is intended throughout the stages. It is an ongoing process that facilitates the young child’s evolving capacity to form views when they are provided with meaningful information. For example, on one occasion, the children took part in an insect hunt as part of a data collection activity. Time was needed to discuss and inform the children how to use the magnifying glasses and that the intention was to look for insects. Many participants chose to use them in other ways but the principle of informing them was there to empower them to participate while supporting their sense of agency. Such is the true essence of the CRC principles. This time invested to inform cannot be underestimated. It requires consistent reflection from the researcher to monitor how the information is being received by the children (Murray Citation2022). To support a researcher to establish what is being understood, Mayne et al (Citation2017) offer three simple questions to consider,

Can the child’s understanding be applied in other situations?

What actions is the child taking from their understanding?

How confident are they in responding to the information?

The third question proved helpful because confidence levels are an indication of good understanding (the high level of engagement in the insect hunt or designing a waste management system for the setting are examples of this confidence). Confidence pays dividends in the quality of participation and in supporting children’s capacities to express their views.

Listening to balance power dynamics

Aside from dedicating time between sessions for reflexivity, I got into the habit of repeating back to the participants their exact words as I heard them. This was a purposeful reflexive strategy. Firstly, it allowed me to fulfil my listening role as their audience under Article 12; secondly, I was able to actively demonstrate to them what I had understood and to check if that was correct; and thirdly it provided an opportunity for the participants to reflect on their ideas as they heard them back. Such practice is common among ECEC practitioners and resonates comfortably with relational listening pedagogies (Lyndon et al. Citation2019; Clark Citation2020). As with reflective pedagogy, it was this practice and the participants’ response to hearing back their ideas that further highlighted the overlap between ECEC practitioners’ skillset and child rights-based participatory methodology (Barnardos Citation2021). Pedagogy and listening are closely linked. Through a process of slowing down to listen, or as Clark (Citation2020) describes it, ‘slow pedagogy’, I could incorporate alternative forms of knowledge from the young participants.

It was an ongoing process of assessing the understanding on both sides that fed into the quality of participation in keeping it meaningful and from the children’s own perspectives (Collins et al. Citation2020). This type of finely grained listening that the CRAG enjoyed also reflected my engagement with elements of the Lundy model, particularly ‘audience’ and ‘influence’ which will be untangled in the following sections (Lundy Citation2007). First, I will highlight a few key definitions contributed by the CRAG pertinent to the design of this rights-based methodology. For example, there was their own process of negotiating consent/dissent throughout, which can be best described as an extension of the existing culture, both gentle and non-invasive in its approach. This was valuable to the informed consent process, which is now explored.

Informed ongoing consent/dissent process

Cocks (Citation2006) in Mayne and Howitt (Citation2022) describes three components necessary for meaningful informed consent: information provided by the researcher, the children’s understanding of the research and what it means to be involved, and the child’s response to the information provided. Child friendly research information materials and events were used to establish informed consent from families and the children. This was consolidated through a cyclical ongoing process to assess what was being understood by participants. Therefore, it was not until I met with each individual participant’s response to the research information at any given moment that I could really understand their participatory rights and stand by a consent process I considered rights-based (Huser, Dockett, and Perry Citation2022). The free-flowing culture of the local context, where children moved as they pleased within and between indoor and outdoor spaces, supported their own decision making whether to take part or not. We started each session with the children exploring the research tools before any participatory decisions were made. This was a messy approach, and my organisational skills were tested with the influx of questions and switches in participant numbers. However, as an ECEC practitioner, I am used to mess and with the support of the site’s own practitioners, we were able to facilitate a relational consent negotiation process that was respectful of the participants’ own culture and autonomous, self-determined choice. The following section explores how the children’s input adapted the ‘audience’ and ‘influence’ elements of the Lundy model (Lundy Citation2007).

Audience and influence at local level

Although continuous reflection helped to ensure that participation was authentic rather than tokenistic, just listening to the participants’ ideas was not enough (Shier Citation2016, Citation2019; Tisdall Citation2015). It was rather what weight I gave to them which would determine any real substance to the realisation of the children’s own participatory rights under Article 12 (UNCRC Citation2008; Ceballos and Susinos Citation2022). MacNaughton, Smith, and Davis ( Citation2013) state that in practical terms all formal research involving children requires some level of adult direction. While children’s research participatory rights must be supported, Tisdall (Citation2016) highlights that there is still a necessity to explore how it is being done. Wall et al. (Citation2019) puts forward an ‘intergenerational approach’. They argue that the adult researcher should not be afraid to shape the research agenda but must do so in a way that is responsive, sensitive and in accordance with how the children expressed their participation preferences. I reflected at length as to how I could bring to life the specific aspects of ‘audience’ and ‘influence’ for the participants to enjoy first-hand by their own rights definitions.

At this stage, I had still not found a suitable external identified listener. Establishing an ‘identified listener’ early in the research stage is something that Lundy and colleagues recommend in committing that participants’ contributions will be given due weight by a person directly involved in decision making. One of the main objectives to the study was to contribute to the development of a rights-based ESD approach for the early education sector. I initially approached the local Department of Education inspector but did not receive a response. This caused me to question their suitability and, as I began to build a rapport with the CRAG, I did not consider a decision maker that far removed from the children’s own lives to be that meaningful for them. In the meantime, the children themselves created their own form of ‘audience’ by sharing their participation with the setting’s practitioners, family relations and other adults that came to collect them, at the end of the research sessions. To that end, I created an online research blog with photographs, stories and resources for the children and their families to further this form of audience in an authentic manner.

The scouting exercise to better find the type of listening they did enjoy, also involved reviewing political candidates’ profiles, discussions of their suitability with my supervisor and attending local meetings at which they spoke. However, I did not find a suitable identified listener for the context but rather informed me of what would not be suitable and what could potentially expose the children to tokenistic listening (Lundy Citation2018). I understood it was important that the children could see the influence of their research participation up close. Like Mayne, Howitt, and Rennie (Citation2018), I began to move the focus on them directly experiencing influence making in the research space rather than influencing policy makers at a macro level. Cassidy et al. (Citation2022) contend that for young children’s voices to have influence there must be someone listening in the space where the voices are being shared. From working with this group, I learned that by providing enough time and space to form, express and see their ideas in action, it was me and the children’s more familiar adults who were most suited to the role as ‘identified listener’. shows how this contribution was applied to the Lundy model to reflect a rights-based approach in a local context.

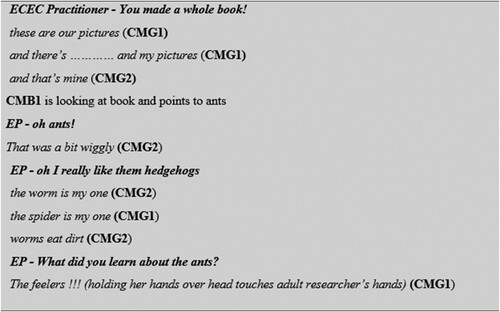

While I have described above a change in my own understanding and listening role, the CRAG also provided insight as to how the other adults in the process could support a listening strategy meaningful to them under their participatory rights. The following extract () is from a workshop where they were engaging with data analysis and involves a discussion about a book they were making, The Children’s Nature Book, with one of their practitioners:

As the children shared their ideas, the response of the listening adult brought to light the significance of relational support with a familiar person in scaffolding young children’s capacity to form and express their own views (Lundy, McEvoy, and Byrne Citation2011, Citation2012). This prompted me to think about how I had originally conceptualised the adult role. I had planned to interview consenting practitioners and family members about the children’s learning, but it just did not fit with the methodology we were designing. Rather the way the CRAG recounted the research activities with their familiar adult demonstrated elements of space, voice, and audience from the Lundy model (Citation2007) that were more respectful of the local context.

In the above, the children were not asked pre-set questions but were given positive responses and admiration for their work. This offered a platform for more individual participation and exploration of children’s own perspectives and what was of particular interest for each child involved (Murray Citation2022). I concluded that to interview any adults to gain ‘second hand’ insight into the children’s perspectives was not aligned with the study’s ethos. Instead, I provided resources to take home (seeds, bird feeding materials, insect charts, magnifying glasses and a copy of The Children’s Nature Book) as tools to better support the children to share their research participation and have it responded to, through a listening means that they could influence (Ceballos and Susinos Citation2022).

External audience and influence

While the process had now been redesigned to provide audience opportunities for the participants’ views and influence over decision making meaningful to their research participation, how I would extend this externally has yet to be fully decided. As the study had identified pedagogical crossovers between early childhood theory, rights-based theory and ESD theory, I have shared parts of the project with ECEC students in the university where I am based. This provided an opportunity to highlight links between theory and practice and bridge the gap between the expertise of practitioners and that of children. I consider this to be an effective external ‘audience’ and ‘influence’ as it was an accessible means to connect the participants and early childhood practitioners. I had struggled with my own understanding of the practicalities of embedding rights-based theory into practice and this teaching offered a real opportunity to provide practitioner-based learning in furthering rights-based pedagogy. The audience has now also extended to the larger community of early childhood professionals, including practitioners, academics and early education advocates at national and international research events, sector publications and visiting lectures. I also intend to further contribute to a shift in child rights-based education through the creation of a module for ESD in early childhood under Article 29 1 (e). Going forward any external audience strategies will continue to be reflected upon and scrutinised from a child rights-based perspective using the participants’ own rights definitions.

Limitations to the children’s audience

In keeping with the type of audience the children enjoyed, there were plans to organise an outdoor book launch party for the children’s own publication, The Children’s Nature Book and a participatory dissemination event. The intention was to invite the children’s families, the settings owner and ECEC practitioners and other people the children wanted to include. However due to the outbreak of the Covid 19 pandemic, this was not possible and limited an important analysis for an effective realisation of participatory rights for the study.

Conclusion

I have argued that education to combat the climate crisis must start by being rights-based and therefore respectful and authentic to the learner’s lived reality. There are multiple realities and understandings that impacts a person’s own meaning making and therefore knowledge (Mertens Citation2007). When we commit to explore and represent the true perspectives of another, we need to examine how their realities are constructed (Murray Citation2022). That would include unravelling how people’s perspectives are shaped by political, economic, and cultural systems (O’Toole Citation2020). For young children an adult/child power dynamic exists because of their age. Children are regarded as deficient because they are not seen to have expertise. This gives the adults in their lives an unearned expert privilege (Gillet-Swan and Sargent Citation2018, Citation2019; Kucharczyk and Hanna Citation2020). From a child’s rights perspective, such a discrepancy requires careful consideration and action. We must advocate for authentic participation and true representation of children’s views on matters that affect them in their lives, in this case their education for climate change. How we position our children, as ‘beings’, ‘becomings’, ‘contributing social actors’ with their own expertise and knowledge and what respect we give to that, will ultimately determine how ethical and child rights compliant our approach is to ESD (Urbina-Garcia et al. Citation2021).

This paper gives an account of the ethical considerations in how the study was conceptualised and how I applied them. Three points of particular relevance in supporting a rights-based approach was listening to the learners’ perspectives, developing an understanding of the local context culture and making time for reflexivity in keeping the rights, dignity and moral respect for each child fore frontal throughout the process. I also discussed how the local context adapted elements of Lundy’s model as it relates to ‘audience’ and ‘influence’ so that the study’s impact was more authentic to the participants as rights holders (Ceballos and Susinos Citation2022). My two key arguments were, firstly, that education for climate change in ECEC requires a child rights-based participatory approach at the local level and, second, that ECEC pedagogy has many aspects that overlap to support this. Creating a rights-based education approach for ESD means taking seriously the social and cultural pillar of sustainability (Pramling Samuelsson and Kaga Citation2008). This entails building a child rights respecting culture at local level and, from there, empowering children to contribute to sustainability learning starting points under both their education and participatory rights. The research strategies to support meaningful child participation described in the methodology could be considered as practical tips for application; for practitioners, researchers within the field of ECEC, and policymakers. What is key in accordance with the young participants, is to concentrate first on what a rights-based methodology means for an individual learning setting and to take it from there to make an ESD curriculum together.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alderson, Priscilla. 2012. “Rights-Respecting Research: A Commentary on the Right to be Properly Researched: Research with Children in a Messy, Real World, Children’s Geographies, 2009, 7, 4, Children’s Geographies, 2009, 10, 4.” Children’s Geographies 10 (2): 233–239. doi:10.1080/14733285.2012.661603.

- Boardman, Karen. 2022. “Where are the Children’s Voices and Choices in Educational Settings’ Early Reading Policies? A Reflection on Early Reading Provision for Under-Threes.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (1): 131–146. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2022.2026437.

- Boyd, Diane. 2018. “Early Childhood Education for Sustainability and the Legacies of Two Pioneering Giants.” Early Years 38 (2): 227–239. doi:10.1080/09575146.2018.1442422.

- Bruner, J. S. 1996. The Culture of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cassidy, Claire, Kate Wall, Carol Robinson, Lorna Arnott, Mhairi Beaton, and Elaine Hall. 2022. “Bridging the Theory and Practice of Eliciting the Voices of Young Children: Findings from the Look Who’s Talking Project.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (1): 32–47. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2022.2026431.

- Ceballos, Noelia, and Teresa Susinos. 2022. “Do My Words Convey What Children are Saying? Researching School Life with Very Young Children: Dilemmas for ‘Authentic Listening.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (1): 81–95. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2022.2026435.

- Clark, Alison. 2020. “Towards a Listening ECEC System.” In Transforming Early Childhood in England: Towards a Democratic Education, edited by Claire Cameron, and Peter Moss, 134–150. London: UCL Press.

- Cocks, A. J. 2006. “The Ethical Maze.” Childhood 13 (2): 247–266. doi:10.1177/0907568206062942.

- Collins, Tara M., Lucy Jamieson, Laura H.V. Wright, Irene Rizzini, Amanda Mayhew, Javita Narang, E. Kay M. Tisdall, and Mónica Ruiz-Casares. 2020. “Involving Child and Youth Advisors in Academic Research About Child Participation: The Child and Youth Advisory Committees of the International and Canadian Child Rights Partnership.” Children and Youth Services Review 109: 104569. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104569.

- CRA (Child Rights Alliance). 2021. Report Card 2021 – Is Government Keeping its Promises to Children? Dublin: Child Rights Alliance.

- Croft, Anita. 2017. “Leading the Change Toward Education for Sustainability in Early Childhood Education.” He Kupu 5 (1): 53–60.

- Davies, Julie. 2014. “Examining Early Childhood Education Through the Lens of Education for Sustainability: Revisioning Rights.” In Research in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: International Perspectives and Provocations, edited by Julie Davis, and Sue Elliott, 21–37. Milton Park: Routledge.

- Davis, Julie. 2009. “Revealing the Research ‘Hole’ of Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: A Preliminary Survey of the Literature.” Environmental Education Research 15 (2): 227–241. doi:10.1080/13504620802710607.

- DCEDIY (Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth). 2021. Participation Framework: National Framework for Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making. Dublin: The Stationary Office.

- DES (Department of Education and Skills). 2014. Education for Sustainability: The National Strategy on Education for Sustainable Development in Ireland, 2014-2020. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

- ECI (Early Childhood Ireland). 2021. Early Childhood Ireland Annual Report 2021. Dublin: Early Childhood Ireland.

- Fane, Jennifer, Colin MacDougall, Jessie Jovanovic, Gerry Redmond, and Lisa Gibbs. 2018. “Exploring the Use of Emoji as a Visual Research Method for Eliciting Young Children’s Voices in Childhood Research.” Early Child Development and Care 188 (3): 359–374. doi:10.1080/03004430.2016.1219730.

- Forde, Louise, and Ursula Kilkelly. 2021. “Incorporating the CRC in Ireland.” In Incorporating the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child into National Law, edited by Ursula Kilkelly, Laura Lundy, and Bronagh Byrne, 177–202, Intersentia. doi:10.1017/9781839701764.008.

- Gillett-Swan, Jenna K., and Jonathon Sargeant. 2018. “Unintentional Power Plays: Interpersonal Contextual Impacts in Child-Centred Participatory Research.” Educational Research 60 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/00131881.2017.1410068.

- Gillett-Swan, Jenna K., and Jonathon Sargeant. 2019. “Perils of Perspective: Identifying Adult Confidence in the Child’s Capacity, Autonomy, Power and Agency (CAPA) in Readiness for Voice-Inclusive Practice.” Journal of Educational Change 20 (3): 399–421. doi:10.1007/s10833-019-09344-4.

- Government of Ireland (GOI). 2022. ESD to 2030: Second National Strategy on Education for Sustainable Development. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

- Hirst, Nicola. 2019. “Education for Sustainability Within Early Childhood Studies: Collaboration and Inquiry Through Projects with Children.” Education 3-13 47 (2): 233–246. doi:10.1080/03004279.2018.1430843.

- Huser, Carmen, Sue Dockett, and Bob Perry. 2022. “Young Children’s Assent and Dissent in Research: Agency, Privacy and Relationships Within Ethical Research Spaces.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (1): 48–62. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2022.2026432.

- Ireland Barnados.. 2021. “Children’s Participation.” In Childlinks. Vol. 2. Dublin: Barnardos.

- Johnston, Kelly. 2022. “Creating Space for Equity in Early Childhood Educator’s Participation in Documentation, Assessment and Evaluation.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (3): 360–371. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2021.2019291.

- Klitgaard Povlsen, Karen, S. Strom Krogager Gunder, J. Leer, and S. Hojjlund Pedersen. 2021. “Children, Food and Digital Media: Questions, Challenges and Methodologies.” In Childhood Cultures in Transformation: 30 Years of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child in Action Towards Sustainability, edited by Ødegaard Elin Eriksen, and Jorunn Spord, 162–177. Leiden: Brill Sense.

- Kucharczyk, Stefan, and Helen Hanna. 2020. “Balancing Teacher Power and Children’s Rights: Rethinking the Use of Picturebooks in Multicultural Primary Schools in England.” Human Rights Education Review 3 (1): 49–68. doi:10.7577/hrer.3726.

- Long, Sheila. 2021. “Participation: Some Considerations for Early Childhood Education Programmes.” In Children’s Participation Childlinks, vol. 2, edited by Barnardos Ireland, 25–32. Dublin: Barnardos.

- Luff, Paulette. 2018. “Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: Origins and Inspirations in the Work of John Dewey.” Education 3-13 46 (4): 447–455. doi:10.1080/03004279.2018.1445484.

- Lundy, Laura. 2007. “‘Voice’ is not Enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.” British Educational Research Journal 33 (6): 927–942. doi:10.1080/01411920701657033.

- Lundy, Laura. 2018. “In Defence of Tokenism? Implementing Children’s Right to Participate in Collective Decision-Making.” Childhood 25 (3): 340–354. doi:10.1177/0907568218777292.

- Lundy, Laura, and Lesley McEvoy. 2012. “Children’s Rights and Research Processes: Assisting Children to (In)formed Views.” Childhood 19 (1): 129–144. doi:10.1177/0907568211409078.

- Lundy, Laura, Lesley McEvoy, and Bronagh Byrne. 2011. “Working With Young Children as Co-Researchers: An Approach Informed by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.” Early Education & Development 22 (5): 714–736. doi:10.1080/10409289.2011.596463.

- Lundy, Laura, and Gabriela Martínez Sainz. 2018. “The Role of Law and Legal Knowledge for a Transformative Human Rights Education: Addressing Violations of Children’s Rights in Formal Education.” Human Rights Education Review 1 (2): 4–24. doi:10.7577/hrer.2560.

- Lundy, L., Byrne, B., Lloyd, K., Templeton, M., Brando, N., Corr, M-L., Heard, E., Holland, L., MacDonald, M., Marshall, G., McAlister, S., McNamee, C., Orr, K., Schubotz, D., Symington, E., Walsh, C., Hope, K., Singh, P., Neill, G., & Wright, L. H. V. 2021. “Life Under Coronavirus: Children’s Views on their Experiences of their Human Rights.” International Journal of Children's Rights, 29 (2): 261–285. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-29020015

- Lyndon, Helen, Tony Bertram, Zeta Brown, and Chris Pascal. 2019. “Pedagogically Mediated Listening Practices; the Development of Pedagogy Through the Development of Trust.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 27 (3): 360–370. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2019.1600806.

- MacNaughton, Glenda, Kylie Smith, and Karina Davis. 2013. “Researching with Children: The Challenges and Possibilities for Building ‘Child Friendly’ Research.” In Early Childhood Qualitative Research, edited by Hatch, J. Amos, 167–184. doi:10.4324/9780203943502.

- Mayne, Fiona, and Christine Howitt. 2022. The Narrative Approach to Informed Consent: Empowering Young Children’s Rights and Meaningful Participation. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mayne, Fiona, Christine Howitt, and Léonie Rennie. 2016. “Meaningful Informed Consent with Young Children: Looking Forward Through an Interactive Narrative Approach.” Early Child Development and Care 186 (5): 673–687. doi:10.1080/03004430.2015.1051975.

- Mayne, Fiona, Christine Howitt, and Léonie J. Rennie. 2017. “Using Interactive Nonfiction Narrative to Enhance Competence in the Informed Consent Process with 3-Year-Old Children.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (3): 299–315. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1260833.

- Mayne, Fiona, Christine Howitt, and Léonie J. Rennie. 2018. “A Hierarchical Model of Children’s Research Participation Rights Based on Information, Understanding, Voice, and Influence.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 26 (5): 644–656. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2018.1522480.

- Mertens, Donna M. 2007. “Transformative Paradigm.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1 (3): 212–225. doi:10.1177/1558689807302811.

- Moody, Zoe, and Frédéric Darbellay. 2019. “Studying Childhood, Children, and Their Rights: The Challenge of Interdisciplinarity.” Childhood 26 (1): 8–21. doi:10.1177/0907568218798016.

- Moss, Peter, and Guy Roberts-Holmes. 2022. “Now Is the Time! Confronting Neo-Liberalism in Early Childhood.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 23 (1): 96–99. doi:10.1177/1463949121995917.

- Murray, Jane. 2022. “Any Questions? Young Children Questioning in Their Early Childhood Education Settings.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (1): 108–130. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2022.2026436.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 2009. Aistear: the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework Principles and Themes. Stationery Office.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 2015. Aistear Siolta practice guide, [online]. http://aistearsiolta.ie/en/.

- Nolan, Aoife. 2020. “Poverty and Child Rights.” In The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Rights Law, edited by Jonathan Todres, and Shani M. King, 405–425. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nolan, Aoife, and McGrath, Simon. 2016. “SDG 4 and the Child’s Right to Education”. In Education, Training and Agenda 2030: What Progress one Year on?, edited by Norrag. Dublin: Barnardos. https://www.norrag.org/education-training-and-agenda-2030-what-progress-one-year-on/

- O’Toole, Leah. 2020. “Participant Action Research (PAR) for Early Childhood and Primary Education: The Example of the THRIECE Project.” Problemy Wczesnej Edukacji 49 (2): 31–44. doi:10.26881/pwe.2020.49.03.

- Parry, Becky. 2015. “Arts-Based Approaches to Research with Children: Living with Mess.” In Visual Methods with Children and Young People: Academics and Visual Industries in Dialogue, edited by Eve Stirling, 89–98. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pramling Samuelsson, I. and Kaga. Y. 2008. UNESCO Report: The Contribution of Early Childhood Education to a Sustainable Society. Paris: UNESCO.

- Roa, D., Whitebread, D and Guzmán, B. 2018. “Methodological issues in representing children’s perspectives in transition research.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, [online], 26 (5): 760–779, available: https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1522764

- Robson, Jenny. 2016. “Early Years Teachers and Young Children’s Rights: The Need for Critical Dialogue.” doi:10.15123/PUB.5091.

- Shier, Harry. 2016. Children’s Rights in School: The Perception of Children in Nicaragua. Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast.

- Shier, Harry. 2019. “An Analytical Tool to Help Researchers Develop Partnerships with Children and Adolescents.” In Participatory Methodologies to Elevate Children’s Voice and Agency, edited by Ilene R. Berson, Michael J. Berson, and Colette Gray, 295–316. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

- Siraj-Blatchford, J., Smith, K.C. and Pramling Samuelsson, I. 2010. OMEP Report: Education for Sustainable Development in the Early Years. OMEP.

- Skånfors, L. 2009. “Ethics in Child Research: Children's Agency and Researchers' 'Ethical Radar'.” Childhoods Today 3 (1).

- Spiteri, Jane. 2021. “Why Is It Important to Protect the Environment? Reasons Presented by Young Children.” Environmental Education Research 27 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1829560.

- Tisdall, E., and M. Kay. 2015. “Children’s Rights and Children’s Wellbeing: Equivalent Policy Concepts?” Journal of Social Policy 44 (4): 807–823. doi:10.1017/S0047279415000306.

- Tisdall, E. Kay M. 2016. “Participation, Rights and ‘Participatory’ Methods.” In The Sage Handbook of Early Childhood Research, edited by Ann Farrell, Sharon Lynn Kagan, and E. Kay M Tisdall, 73–88. Los Angeles, DC: Sage.

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). 2008. General Comment No 7(2005). Implementing Children’s Rights in Early Childhood. Geneva: UN General Assembly.

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Geneva: UN General Assembly.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, (UNESCO). 1997. Educating for a Sustainable Future. Geneva: UN General Assembly.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2000. United Nations Millennium Declaration. Geneva: UN General Assembly.

- United Nations Development Programme, (UNDP). 2015. Sustainable Development Goals 2030. Geneva: UN General Assembly.

- Urbina-Garcia, Angel, Divya Jindal-Snape, Angela Lindsay, Lauren Boath, Elizabeth F. S. Hannah, Alexia Barrable, and Anna K. Touloumakos. 2022. “Voices of Young Children Aged 3–7 Years in Educational Research: An International Systematic Literature Review.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (1): 8–31. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2021.1992466.

- Waldron, Fionnuala, Benjamin Mallon, Maria Barry, and Gabriela Martínez Sainz. 2020. “Climate Change Education in Ireland: Emerging Practice in a Context of Resistance.” In Ireland and the Climate Crisis, edited by David Robbins, 231–248. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wall, K., C. Cassidy, C. Robinson, E. Hall, M. Beaton, M. Kanyal, and D. Mitra. 2019. “Look Who’s Talking: Factors for Considering the Facilitation of Very Young Children’s Voices.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 17 (4): 263–278. doi:10.1177/1476718X19875767.

- Wall, Kate, and Carol Robinson. 2022. “Look Who’s Talking: Eliciting the Voice of Children from Birth to Seven.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2022.2026276.

- Zanatta, Francesa, and Sheila Long. 2021. “Rights to the Front Child Rights-Based Pedagogies in Early Childhood Degree.” Journal of Early Childhood Education Research 10 (1): 139–165.