ABSTRACT

Early childhood education and care in Norway have a broad mission and are, among other things, mandated through legislation and frameworks to remedy social injustice and emphasise inclusion. Nevertheless, research illustrates that symbolic power tends to be present in early childhood education and care institutions. In this conceptual paper, it is discussed how the local line leadership and staff in early childhood education and care institutions can analyse and challenge their work with inclusion when partaking in multicultural professional development. A model is presented to function as a tool to help the line leadership and staff in this process. It is argued that to function as learning inclusion arenas, it is necessary that the local line leadership and the staff critically explore how the institution function for all actors and that they visualise and challenge potential symbolic power in the institution.

Introduction

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) are mandated to remedy social injustice and emphasise inclusion (Meld. St. Citation19 Citation2015–Citation2016; Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (UDIR Citation2017; OECD Citation2019). However, both Norwegian and international research illustrates that the majority’s habitus and symbolic capital tend to dominate institutions such as ECEC institutions (Bergsland Citation2018; Solberg Citation2018; Sønsthagen Citation2021; Van Laere and Vandenbroeck Citation2017). Moreover, research illustrates a lack of competence concerning, among other things, multicultural pedagogy in the Norwegian education field, and ECEC institutions' leadership and staff expressed uncertainty when cooperating with families with multicultural backgrounds (Bergsland Citation2018; Gotvassli et al. Citation2012; Kunnskapsdepartement Citation2018). There has not been conducted much research on leadership and multiculturalism in the Norwegian context (Sønsthagen, Citation2021). In my PhD-study (Sønsthagen, Citation2021), I studied the leadership of multicultural professional development and the inclusion of parents with refugee backgrounds in ECEC institutions. I found, among other things, that the leadership seemed to play a significant role in developing multicultural competence amongst the staff, by facilitating and offering space for critical reflections and new understandings in a learning community. Lund (Citation2022) studied, among other things, how pedagogical leaders led, understood, and supported cultural diversity in ECEC institutions. One of her results illustrated that the pedagogical leaders' pedagogical practice and understanding of cultural diversity, played a significant role in safeguarding and recognising cultural diversity.

In this conceptual paper, I will discuss the following research question:

How can the local line leadership and staff in ECIs analyse and challenge their work with inclusion when partaking in multicultural professional development?

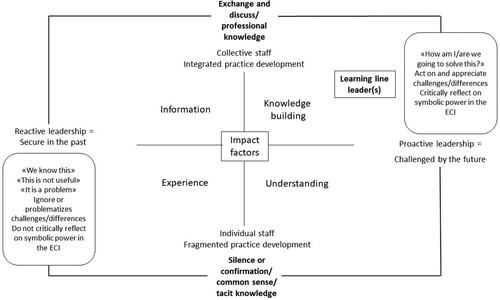

I present and discuss a model illustrating my understanding of learning ECEC institutions as inclusion arenas, aiming to contribute to starting a reflection process amongst leadership and staff participating in multicultural professional development. The model could also help in analysing the ECEC institution's starting point and its development throughout the development work and challenge the institution's pedagogical practice. The model evolves both from the theoretical framework, empirical data, and analysed results from my PhD study (Sønsthagen Citation2021). In this paper, the discussion is further extended by exploring Pedler, Boydell, and Burgoyne's (Citation2019) four stances or shifts of mind in a learning organisation. Finally, I will discuss the model’s implications for learning ECEC institutions working towards being an inclusion arena for all its actors.

Contextual and theoretical background

Before presenting the model, I will discuss relevant contextual factors and theoretical concepts.

The Norwegian context

ECEC institutions are viewed as significant institutions in Norwegian society, and all children aged 1–5 years have the right to attend an ECEC institution with children of the same age (UDIR Citation2018). 93.4% of all children in Norway aged 1–5 years, attended ECEC institutions in 2022 (UDIR Citation2023a). Parents are emphasised as significant stakeholders in the Norwegian Framework Plan for ECEC and the institutions should work in partnership and agreement with the home (UDIR Citation2017). The number of children with a minority-language backgroundFootnote1 has almost doubled in the last ten years, and in 2022, 19% of the children in ECIs had a minority-language background. This accounts for about 87% of all children with minority-language backgrounds living in Norway. The ECEC statistics do not differentiate children with a refugee background, however, 4.5% of the population in Norway has a refugee background (Statistics Norway Citation2022). People who have refugee as the reason for immigration and immigrants reunited with persons with refugee status are defined by Statistics Norway as persons with refugee backgrounds. They are granted asylum or residence under the UN Refugee Convention (Integrerings- og mangfoldsdirektoratet Citation2022) and should become residents in a municipality. The refugee has both a right and a duty to participate in the Introductory scheme for refugees, which should provide fundamental insight into the Norwegian social life, and necessary Norwegian skills, and prepare for participation in work-life (Introduksjonsloven Citation2003). The Introductory scheme is full-time, thus, making parents with refugee backgrounds dependent on ECEC institutions for their children.

The mandate of Norwegian ECEC is to offer children below compulsory school age a caring and learning environment, ensuring a holistic practice that emphasises the intrinsic value of childhood. The ECEC institutions should ‘work in partnership and agreement with the home to meet the children’s need for care and play, and they shall promote learning and formative development as a basis for all-round development’ (UDIR Citation2017, 7). Additionally, the ECEC should reduce social injustices and support the child according to their cultural and individual preconditions, viewing diversity and multilingualism as resources, and ensuring that all actors in the ECEC institution feel seen, included and valued (Meld. St. Citation6 Citation2012–Citation2013).

In Norwegian ECEC institutions, the manager is the institution's headteacher, having the day-to-day responsibility for pedagogical practices, pedagogical leaders, staff, and administration (UDIR Citation2017). The pedagogical leaders have the responsibility of a specific department and must ensure that the planning, implementation, documentation, assessment, and development of the pedagogical work comply with legislations and frameworks. The manager has the primary leadership responsibility at an institutional and executive level, whereas the pedagogical leaders have the leadership responsibility at an operationalised level (Børhaug and Lotsberg Citation2014). Together they constitute the local line leadership in the ECI (Sønsthagen Citation2021). Both the manager and the pedagogical leader have a bachelor’s degree as ECEC teachers. There are no requirements to have a master’s degree to become a manager or pedagogical leader, however, there are relevant master's programs and options to further one’s education. The ECEC institutions can be organised differently, but as a minimum, there should be at least one pedagogical leader per seventh child under the age of three, and one per fourteenth child over the age of three (UDIR Citation2023b).

Symbolic power

A society, as well as educational institutions, likely consist of symbolic power. Symbolic power is a concealed form of power that neither the dominant nor the dominated groups in a society reflects upon or resist (Bourdieu Citation1991). The dominant group, e.g. in this context, ECEC leadership, staff, and parents with a Norwegian background, defines the understanding of reality in the ECEC institution, which there is a common consensus connected to, contributing to the reproduction of social order. The dominated groups, e.g. in this context, parents with refugee backgrounds, are most likely subjugated to this symbolic power. Society consists of small, social worlds, or fields (Bourdieu Citation1990), which are shaped by and also shape ‘the overall field of power’ (Thomson Citation2017, 259), such as the political field or governmental field. The educational field is subordinate to the overall field of power, as it produces qualified people who can work at different levels in other fields, as well as reproducing ‘the kinds of knowledge, skills and dispositions already possessed and valued by the social elites and managerial elites in all other fields’ (Thomson Citation2017, 9). Institutions such as the ECEC institutions can be seen as small fields in themselves, connecting both to the general education field and the overall field of power (Sønsthagen Citation2021, 76). For parents with refugee backgrounds, to be fully viable members of the institution, they must both ‘recognize and comply with the demands immanent in the field’ (Bourdieu Citation1990, 58). Thus, they must adjust to the field’s demands.

Symbolic capital and habitus

Symbolic capital, which consists of cultural and social capital, determines the power leadership, staff, parents, and children possess in the ECEC institution, such as what is considered the legitimate language, or linguistic capital, or to what degree they are recognised as significant stakeholders in the institution (Bourdieu Citation1991; Sønsthagen Citation2021). Cultural capital refers to the accumulation of knowledge, skills, and behaviour (Bourdieu Citation1997). In the ECEC context, several elements might constitute the members’ various cultural capitals, such as:

Leadership and staff’s understanding/lack of understanding, of different families’ backgrounds, norms, and values,

parents’ understanding/lack of understanding of the institution's social codes and practices,

shared/different values of all the institution's actors, and

the institution's actors understanding of parental cooperation (Sønsthagen Citation2021, 80).

Social capital consists of social connections, which in turn contributes to the potential of converting social capital into cultural capital (by, for instance, sharing one's experiences and understandings with other field members). In the ECEC context, this can be illustrated as parents’ social network and opportunities to discuss their experiences with, understandings of, and challenges with the ECEC institution with other parents.

The educational field, like other fields in society, depends on agents equipped with the necessary habitus (Bourdieu Citation1990). Habitus is embodied sets of dispositions, such as learned actions, culture, and language telling us how to act and react in certain situations, as well as our essential norms and values (Bourdieu Citation1991). Habitus is context-dependent, meaning that, e.g. parents with refugee backgrounds are likely to have a different habitus than parents, leadership, and staff with a Norwegian, dominant background. Habitus contributes to forming established ways of thinking and is difficult to challenge. The primary habitus, acquired through upbringing, tends to protect itself from being criticised and is resistant to change (Bourdieu Citation1991, Citation1990). When people experience situations or practices that lack congruence with their habitus, they might struggle with knowing how to act and are likely to dismiss or exclude them (Bourdieu Citation1990). The secondary habitus is formed through education and life and is more dynamic than the primary habitus (Thomson Citation2017). The educational field tends to favour and reproduce the symbolic capital and habitus of the dominant group in society (Bourdieu Citation1997), contributing to a reproduction of inequalities rather than remedying such inequalities. Thus, the theory of symbolic power is relevant for educational institutions such as the ECEC institutions and closely connects to inclusion and exclusion processes in the educational field.

Inclusion in ECEC institutions

All social contexts have processes of inclusion and exclusion (Bundgaard and Gulløv Citation2008). Inclusion concerns the functioning of communities, involving all the actors of a community, such as the ECEC institution, not just minority groups (Gundara Citation2000). When emphasising the minority children’s or parents’ socialisation with the majority group, the education field fails to change the social structure or pedagogical content and thus risks excluding the minority groups in the institution by reproducing the majority’s symbolic capital and habitus (Bourdieu Citation1991; Gundara Citation2000). Inclusion is a dialectic process where equity is emphasised and the relationship between actors is based on people’s uniqueness. All members of society or an institution should have the opportunity to participate in and affect the community, regardless of background (Sønsthagen Citation2021, 8).

The ECEC institution as an inclusion arena entails that the leadership and staff critically explore processes of inclusion and exclusion in the institution and how it function for all actors. The leadership and staff establish and develops equitable cooperation with all parents, and the pedagogical content consists of an equity pedagogy, an empowering ECEC culture, and critical reflexivity amongst staff. Potential inequalities and power relations in the institution are reflected upon and challenged (Sønsthagen Citation2021, 128).

Multicultural professional development

Multicultural professional development is in this context understood as learning activities contributing to, among other things, ECEC leadership and staff’s critical reflections (Fitzgerald and Theilheimer Citation2013) concerning their cultural attitudes, their understanding of other worldviews, and their development of culturally appropriate interpersonal skills (Mio, Barker, and Tumambing Citation2012, 266). It also refers to their ability to reflect critically upon their responsibilities and tasks in a multicultural institution, their ability to shift perspectives by using various cultural frames, how they ‘understand and integrate challenges’ to their beliefs and identity and whether they appreciate and embrace differences in interactions with the different actors in the institution (Mascadri et al. Citation2016, 220).

The leadership of the learning ECEC institution

An ecology of leadership

Senge’s (Citation2006) notion of an ecology of leadership relates to how different levels of leadership in a milieu affect and depend on each other. He suggests three leadership descriptions that coincide, partially overlap, or represent something different than formal leadership positions: local line leaders, network leaders, and executive leaders. In the Norwegian ECEC context, the local line leaders constitute the basic unit in the institution, such as the manager and pedagogical leader. They play a fundamental role when partaking in professional development. At the same time as they need to follow instructions from the state and owner, they also need enough autonomy to adjust such instructions to the local conditions in the institution. Thus, they need insight into both the ECEC institution’s developmental needs, the staff's current competence, and their need and desire for competence development. The local line leadership must both support their staff and participate actively when partaking in professional development and connect the staff’s learning abilities to the institution’s results (Sønsthagen Citation2021).

The network leaders (Senge Citation2006) work closely with the local line leadership and are important to the sharing of new ideas and practices from one working group to another and between institutions. They are also essential for connecting different local line leaders. The executive leaders are responsible for creating the general environment for innovation and change, by formulating overall aims and setting professional, financial, and organisational requirements, at the same time as providing support and obtaining resources. An ecology of leadership points out the interaction and dynamics between different leaders, and without interaction, information, and mutual understanding in the line of the organisation, learning and development will be hampered.

The ECEC institution as a learning organisation

The ECEC institution as a learning organisation can be understood as a well-managed organisation (Moilanen Citation1999) facilitating learning for all its members and consciously transforming itself and its context (Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell Citation1996, 3). It consists of a hybrid leadership (Gronn Citation2009), which helps explain the balance between distributed leadership and the more formal responsibility of the local line leaders. The local line leaders shift between different leadership styles and balance formal and informal work, facilitating individual and collective learning (Sønsthagen Citation2021). In that way, they address the holistic side of the organisation, reducing potential structural and personal barriers that might prevent learning (Moilanen Citation1999). By emphasising collective knowledge building (Wells Citation2008), the line leadership helps staff learn how to learn together (Senge Citation2006). Furthermore, the leadership continuously develops their capacity to create desired results and nurture new, expanded patterns of thinking, together with the staff. Organisational learning is the necessary basis for the day-to-day operation of the ECEC institution and for its values, visions, and goals (Moilanen Citation1999). The leadership is active in the way that they act upon a specific challenge and makes it relevant for the ECEC institution. The responsibility for solving the challenge is distributed in the institution, and parents are included as significant stakeholders (Sønsthagen Citation2021, 96–97).

Definitions of learning organisations always depict an ideal form of organisation. Different ECEC institutions might fulfil different elements in the definition to varying degrees. Nevertheless, most ECEC institutions probably contain learning elements, and can thus achieve both individual and collective learning, even if they do not achieve every element in this definition.

Four stances or shifts of mind in a learning organisation are also relevant when discussing the learning ECEC institution as an inclusion arena (Pedler, Boydell, and Burgoyne Citation2019; Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell Citation1996). The four stances are not hierarchical but are included with each other.

Stance 1 refers to learning to survive, doing things well, and doing it good enough to satisfy the organisation's main goals, which are determined by the dominant stakeholders (Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell Citation1996). Such stakeholders are, for example, the executive leaders, the owner, or politicians. Employees at different levels in the organisation have little say in this context, and power is distributed hierarchically, from top to bottom. In the context of ECEC, this can be explained as, for example, satisfying the goals and requirements set by national or local authorities. Stance 2 is about adaptation and doing things better. Competition with other organisations is more visible, even though the organisation still mainly focuses on itself. One wants to do things better than before and better than the competitors. There is still a leadership hierarchy in the organisation and the focus is more on the individual than on collaboration. This attitude may not be so visible in Norwegian ECEC institutions, however, there might be more competition between ECEC institutions than before, after full ECEC coverage was realised. Some ECEC institutions might also experience competition between departments within the institution.

Stance 3 concerns doing better things – together (Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell Citation1996). The organisation moves from being competitive to being cooperative, and one collaborates with multiple contributors and assesses the effect one's actions have on others. There is more focus on various forms of sharing power, leadership, involvement, and commitment. There is a need to move from the more hierarchical, top-down leadership, where one person or a role holds the leadership responsibility, to look at leadership as something that everyone exercises, regardless of position. It is also necessary to move from holding on to the past to engaging in the future. I see this perspective as particularly relevant for ECEC, as it can be linked to distributed leadership (Gronn Citation2009). At the same time, there will be a need for someone, most likely someone with a formal leadership role, to facilitate the conditions for distributed leadership to work. This may show the need for formal leaders in the ECEC institution who exercise a more hybrid leadership (Gronn Citation2009), where consideration is given both to the individual and relational aspects and collective and pedagogical development (Sønsthagen Citation2021).

When discussing the future of learning organisations and how organisations must adapt to present challenges, stance 4 becomes relevant (Pedler, Boydell, and Burgoyne Citation2019). Stance 4 is about doing things that matter – to the world, and similar methods as in stance 3 are relevant. The question researchers within learning organisations and actors from the practical field must ask themselves is whether a new approach to learning organisations can arise, where one focuses on how organisations influence society, how they should influence society and how one can influence society positively, rather than focusing on neoliberal capitalism, profit and a free market. Earlier theories about learning organisations have been criticised by, among others, Flood (Citation1998) for not addressing issues of knowledge power or social transformation to remove inequalities and change behaviour patterns. Pedler, Boydell, and Burgoyne (Citation2019) say that this criticism must be addressed. There is a need for better arrangements to handle issues of power and politics that contribute to maintaining differences, and one needs room to learn from this.

Learning ECEC institutions as inclusion arenas

The results from my study (Sønsthagen Citation2021) illustrated different leadership approaches, structures, and results of multicultural professional development in two ECEC institutions. The model presented in this paper provides an understanding of essential leadership roles when improving the institution as a learning organisation that also ensures the inclusion of its actors. For the ECEC institution to function as an inclusion arena, I argue that it is necessary that both the local line leadership and the staff critically explore how the institution works for all actors and that they visualise and challenge possible power imbalances in the institution. I suggest that the model Learning early childhood education and care institutions as inclusion arenas, illustrated in , can contribute to reflection processes amongst the local line leadership and staff concerning the ECEC institutions starting point and development when working with, e.g. multicultural professional development. Such reflections can further be used to analyse what steps are necessary to take to develop the institution towards a more learning, inclusive practice. The model stems from both theoretical foundations and empirical data and is a further development of other models developed in my PhD (Sønsthagen and Bøyum Citation2021, 181; Sønsthagen and Glosvik Citation2020, 23; Sønsthagen Citation2021, 109, 111). extends these models and adds an emphasis on symbolic power and inclusion.

Figure 1. Learning early childhood education and care institutions as inclusion arenas (Sønsthagen Citation2021, 134).

One of the basic dimensions is Individual staff – Collective staff. The individual refers to the individual staff member in the ECEC institution, whereas the collective refers to the staff group as a community (Sønsthagen Citation2021). When learning takes place in the institution, I argue that both the line leadership and the staff participate in joint meaning-making that can strengthen both individual and collective understanding. By focusing on both individual and collective values, shared mental models (Senge Citation2006) can contribute to creating a holistic picture of the organisation for the individual. The dimension emphasises whether the knowledge is individual or collective. The model further illustrates four elements inspired by Wells’s (Citation2008) Spiral of knowing; understanding, experience, information, and knowledge building. In , understanding and experience connect to the individual, whereas information and knowledge building connects to the collective. All individuals in the ECEC institution have personal understandings and experiences, e.g. understanding of and learning of different cultures and experiences in collaboration with families with refugee backgrounds. If these understandings and experiences are not talked about or reflected upon, they stay private. Information and knowledge building connects to the collective in this model. Information can refer to e.g. shared information about multicultural competence, inclusion, and relevant framework. Knowledge building means that through dialogue, the staff and line leadership can be better able to understand and evaluate new information and relate this to existing knowledge. Thereafter, they can, as a collective, critically discuss alternative interpretations and implications.

As an example, when facing a challenge in communication with for instance a parent with a refugee background, does the individual staff member ignore or problematise this challenge or forward it to a leader, or explain the challenge based on common sense? Or do they act on the challenge, try to solve it, and discuss it in the professional community, contributing to visualising tacit knowledge and developing professional knowledge in the institution? If individual understandings and experiences are exchanged and discussed collectively, one can make them professional. Common sense is in this context understood as what we believe is the correct attitude or perception, without necessarily linking it to real experience (Mukerji Citation2014). Tacit knowledge means that we can know more than we can tell (Polanyi Citation1983). It is unexpressed knowledge in action that functions as an invisible foundation for action or learning and it is difficult to express what one’s tacit knowledge is (Mukerji Citation2014).

Another basic dimension in the model is Reactive – Proactive leadership which refers, among other things, to passive and active thinking and action (Moilanen Citation1999). Proactive leadership considers the ECEC institution holistically, and both the line leadership and the staff are active in both thinking and action regarding various learning activities (Sønsthagen Citation2021). The line leadership is challenged by the future and integrates the work with professional development into existing work. Hence, they ensure integrated practice development. At the same time, the line leadership distributes the responsibility for the professional development work among the staff, and they are, together with the staff, ready to handle both current and future challenges. A more reactive leadership can lead to more passive thinking and action, and less critical reflection about the ECEC institution’s practices, values, and basic expectations. The line leadership and staff are more preoccupied with holding on to current practice rather than developing it, and the work with professional development comes in addition to the daily operations, and thus the practice development becomes fragmented.

As an example, reactive leadership is likely safely anchored in the past, together with staff who do not see the point in challenging their ideas, thoughts and perceptions about inclusion or multiculturalism. ‘We had a couple of kids from Afghanistan here for a while, that went well so we already know this’, can be one attitude. Then the line leadership can be satisfied with that, or they can proactively challenge such attitudes through questions such as: ‘How do we know it went well?’ ‘For whom did it go well? The children, the parents, or us?’ ‘Who talked to the parents of these children?’ Or: ‘What did we learn from it that can be useful in the future when children with different cultural backgrounds come to the institution?’ Such questions can lead to a form of mapping of attitudes and can also help in visualising potential symbolic power in the institution, at the same time as the same attitudes are challenged through questions that can lead to deeper recognition and reflections.

At the centre of the model, factors that directly or indirectly affect the ECEC institution are placed. These impact factors are dynamic and will vary and thus create different contexts for the individual manager. It is necessary to have systemic thinking (Senge Citation2006) where, among other things, the line leadership directs attention to the connection between various factors that influence the institution's pedagogical practice. Such impact factors can be framework and legislation, the politicians’ and owners’ emphasis, the surrounding society, the leadership and staff’s competence and backgrounds, or the families’ backgrounds and interests (Sønsthagen Citation2021).

It is a complicated leadership responsibility to ensure that symbolic power and inequalities are visualised and challenged. The notion of learning line leaders can help illustrate different steps the leadership can take to improve the ECEC institution as a learning, inclusive arena. By executing hybrid leadership (Gronn Citation2009), the line leadership considers both people (the staff) and production (multicultural professional development) (Blake and Mouton Citation1985) and becomes a learning line leader in a learning organisation (Sønsthagen Citation2021). A learning line leadership stands out as necessary and as a driving force to create stability and predictability for staff in their daily work, while at the same time facilitating critical reflection and practice development.

The model illustrates that understanding and experiences with inclusion and multicultural encounters are something you build as an individual. Line leadership can encourage staff to try out and reflect upon different approaches to pedagogical/didactic problem-solving towards the children, but also to a large extent the parents. Encouraging and supporting staff, e.g. in collaboration with parents with a refugee background can increase the level of knowledge at an individual level. Such knowledge must nevertheless be shared for collective knowledge building and professional knowledge to be developed, and the leadership must build arenas for such sharing. It is not enough that staff members sit in the same room and share their experiences. A learning line leadership can try to build collective knowledge by extracting general knowledge from one individual staff to another, concretising the knowledge, positively challenging the staff, and evolving knowledge to collective action. By working in such a way, understanding can also become a collective element. When the staff act on behalf of the ECEC institution, they know that the other staff members are collective support in their daily actions and challenges they might meet concerning e.g. inclusion. To understand oneself as a professional practitioner in the face of new challenges, requires competence, confidence, and critical reflection. Seeing one own symbolic power is not simple; it requires that one learns to see oneself in the bigger picture. Those who have such an image of themselves and the institution, work, I argue, in a learning, inclusive ECEC institution.

Implications and concluding remarks

The initial aim discussed in this paper was to investigate how the local line leadership and staff in ECEC institutions could analyse and challenge their work with inclusion when partaking in multicultural professional development. Throughout the paper, I have argued that it is necessary to critically explore how the institution works for all actors and to visualise and challenge possible symbolic power in the institution, to function as a learning, inclusive ECEC institution. I presented a model that could contribute to reflection processes amongst the line leadership and staff concerning their starting point and development when partaking in multicultural professional development. It is not easy to see one's symbolic power. One way to achieve this could be that the local line leaders support their staff in establishing and developing equal cooperation with all parents and at the same time reflect critically on the institution’s previous traditions, procedures, and social codes. When doing this consciously, one can discuss challenges in the light of professional knowledge rather than solely basing it on common sense. In this way, the individual and collective expressed and tacit knowledge can be challenged and evolved.

The societal mandate for ECEC in Norway is to, in partnership and agreement with the home, offer children under school age a caring and learning environment, with a healthy pedagogical practice, reduce social inequalities, support the child concerning their cultural and individual prerequisites and promote democracy, participation, and resilient societies (UDIR Citation2017). This shows the great responsibility given to the ECEC institutions, illustrating the need to mainly focus on stances 3 and 4 (Pedler, Boydell, and Burgoyne Citation2019) when working to develop the learning ECEC institution as an inclusion arena. It becomes necessary to critically challenge potential symbolic power in the institution and reflect upon how the institution influence its actors and society, how they should do this and how they can influence its actors and society as inclusive and sustainable as possible.

When studying multicultural professional development in Norwegian ECEC and the inclusion of parents with refugee backgrounds (Sønsthagen Citation2021), I experienced both resistance and ignoring of issues from some staff. One can question whether some topics are more challenging than others when working with professional development. And whether some topics make it particularly challenging for the line leaders to develop the ECEC institution as a learning organisation. Symbolic power and inclusion can be described as political topics and challenging one’s practice and critically reflecting upon one’s attitudes towards political topics can lead to strong discomfort (Biesta Citation2014). However, people must also endure what is different and foreign. This can be challenging, regardless of how much one has learnt about being tolerant and respectful. Political existence (Biesta Citation2014, 114), which can be understood as existing together in plurality and dealing with what is foreign, is not something that can be put off when it is not practical for us, especially when working in the educational field. Educational staff have both a democratic responsibility to teach children to cope with such situations and to be able to adapt to the various situations they encounter, and they have a responsibility not to show resistance to learning themselves, where one avoids what can be experienced as unpleasant.

Instead of showing clear resistance to discomfort, one can also experience people who ‘park’ the problem (Argyris and Schön Citation1996). When the line leadership experience such attitudes from staff, it is necessary to ask how they deal with staff who avoids discomfort or ‘park’ the problem. Does the line leadership allow ignoring of challenges and differences, or problematisation of such, leading to no critical reflection of potential symbolic power in the institution? Or do they confront the staff with potential discomfort and avoidance? Some actions, some ways to ask questions, discuss, and interpret, are arguably more productive than others to achieve organisational learning. Does the line leadership ask the staff ‘How and why?’, ‘Why not?’, ‘What hinders?’, ‘in what ways?’, and ‘How does one know that one has succeeded?’ (Moilanen Citation2005, 75) For instance, does the line leadership and staff asks how am I or we going to solve this? How can we visualise and critically reflect upon potential symbolic power in our institution? Does the line leadership facilitate room and space for its staff to discuss their challenges, experiences, and reflections? And does the line leadership together with staff act upon and appreciate challenges and differences? I suggest that these are questions and practices the learning line leaders can use to develop the learning ECEC institution as an inclusion arena.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Children in Norwegian ECEC institutions are defined as minority language speakers if both the child and the child’s parents speak a language other than Norwegian, Sami, Danish, Swedish or English as their first language (UDIR Citation2023a).

References

- Argyris, Chris, and Donald A. Schön. 1996. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice. Addison-Wesley Series on Organizational Development. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Bergsland, Mirjam Dahl. 2018. “Barnehagens møte med minoritetsforeldre: en kritisk studie av anerkjennelsens og miskjennelsens tilblivelser og virkninger” [The early childcare institution’s meeting with minority parents: A critical study of the genesis and effects of acknowledgement and disacknowledgement.] PhD, NTNU.

- Biesta, Gert J. J. 2014. The Beautiful Risk of Education, Interventions. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publ.

- Blake, Robert R., and Jane S. Mouton. 1985. The Managerial Grid III: The Key to Leadership Excellence. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Co.

- Børhaug, Kjetil, and Dag Øyvind Lotsberg. 2014. “Fra kollegafellesskap til ledelseshierarki? De pedagogiske lederne i barnehagens ledelsesprosess” [From a community of colleagues to management hierarchy? The educational leaders in the early childcare institution's management process]. Nordisk Barnehageforskning 7 (13): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.628.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Le sens pratique. Oxford: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Translated by G. Raymond and M. Adamson, Ce que parler veut dire l'économie des échanges linguistiques. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1997. “The Forms of Capital.” In Education: Culture, Economy and Society, edited by A. H. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown, and A. S. Wells, 46–59. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bundgaard, Helle, and Eva Gulløv. 2008. Forskel og fællesskab: minoritetsbørn i daginstitution. [Difference and community: Minority children in day-care institutions]. Socialpædagogisk bibliotek. København: Hans Reitzel.

- Fitzgerald, Meghan, and Rachel Theilheimer. 2013. “Moving toward Teamwork Through Professional Development Activities.” Early Childhood Education Journal 41 (2): 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0515-z.

- Flood, Robert L. 1998. “‘Fifth Discipline’: Review and Discussion.” Systemic Practice and Action Research 11 (3): 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022948013380.

- Gotvassli, Kjell-Åge, Anne Sigrid Haugset, Birgitte Johansen, Gunnar Nossum, and Håkon Sivertsen. 2012. Kompetansebehov i barnehagen: en kartlegging av eiere, styrere og ansattes vurderinger i forhold til kompetanseheving [Competence needs in kindergarten: A survey of owners, managers and employees’ assessments in relation to raising competence]. Steinkjer: Trøndelag forskning og utvikling. https://tfou.no/publikasjoner/kompetansebehov-i-barnehagen/.

- Gronn, Peter. 2009. “Leadership Configurations.” Leadership 5 (3): 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715009337770.

- Gundara, Jagdish S. 2000. Interculturalism, Education and Inclusion. London: Paul Chapman Publ.

- Integrerings- og mangfoldsdirektoratet. 2022. “Ord og begreper” [Words and concepts]. Accessed 8 March. https://www.imdi.no/om-integrering-i-norge/ord-og-begreper/.

- Introduksjonsloven. 2003. “Lov om introduksjonsordning og norskopplæring for nyankomne innvandrere (LOV-2003-07-04-80)” [Act on the introduction scheme and Norwegian training for newly arrived immigrants]. In: Lovdata.

- Kunnskapsdepartement. 2018. Barnehagelærerrollen i et profesjonsperspektiv: et kunnskapsgrunnlag [The kindergarten teacher’s role in a professional perspective: A knowledge base]. Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet.

- Lund, Hilde Birgitte. 2022. “Ulikhet, likhet og mangfold. Pedagogisk ledelse og foreldreskap i kulturelt mangfoldige barnehager. [Inequality, equality and diversity. Pedagogical leadership and parenting in culturally diverse kindergartens].” PhD, Høgskulen på Vestlandet.

- Mascadri, Julia, Jo Lunn Brownlee, Susan Walker, and Jennifer Alford. 2016. “Exploring Intercultural Competence Through the Lens of Self-Authorship.” Early Years 37 (2): 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2016.1174930.

- Meld. St. 19. 2015–2016. Tid for lek og læring: Bedre innhold i barnehagen [Time for play and learning: Better content in the early childcare institution] Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet.

- Meld. St. 6. 2012–2013. En helhetlig integreringspolitikk: Mangfold og fellesskap [A comprehensive integration policy: Diversity and community]: Barne-, likestillings-, og inkluderingsdepartementet.

- Mio, Jeffery Scott, Lori Barker-Hackett, and Jaydee Turmambing. 2012. Multicultural Psychology: Understanding our Diverse Communities, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press.

- Moilanen, Raili. 1999. “Finnish Learning Organizations: Structure and Styles.” The Entrepreneurial Executive 4:1–39.

- Moilanen, Raili. 2005. “Diagnosing and Measuring Learning Organizations.” The Learning Organization 12 (1): 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470510574278.

- Mukerji, Chandra. 2014. “The Cultural Power of Tacit Knowledge: Inarticulacy and Bourdieu’s Habitus.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 2 (3): 348–375. https://doi.org/10.1057/ajcs.2014.8.

- OECD. 2019. Providing Quality Early Childhood Education and Care. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/providing-quality-early-childhood-education-and-care_301005d1-en; OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/301005d1-en.

- Pedler, Mike, Tom Boydell, and John Burgoyne. 2019. “Learning Company: The Learning Orgnization According to Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Learning Organization, edited by Anders Örtenblad, 87–103. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pedler, Mike, John Burgoyne, and Tom Boydell. 1996. The Learning Company: A Strategy for Sustainable Development. 2nd ed. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill.

- Polanyi, Michael. 1983. The Tacit Dimension. Glouchester: Peter Smith.

- Senge, Peter. 2006. The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization. Rev. and updated ed. New York: Random House Business Books.

- Solberg, Janne. 2018. “Kindergarten Practice: The Situated Socialization of Minority Parents.” Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) 2 (1): 39–54. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2238.

- Sønsthagen, Anne Grethe. 2021. “Leadership and Responsibility: A Study of Early Childcare Institutions as Inclusion Arenas for Parents with Refugee Backgrounds.” PhD, University of South-Eastern Norway.

- Sønsthagen, Anne Grethe, and Øyvind Glosvik. 2020. “‘Learning by Talking?’ – The Role of Local Line Leadership in Organisational Learning.” Forskning og forandring 3 (1): 6–27. https://doi.org/10.23865/fof.v3.2124.

- Sønsthagen, Anne, Sigrid Grethe. 2021. “Interkulturell kompetanseutvikling – ein studie om leiing av barnehagepersonalet som lærer å lære om foreldresamarbeid. [Intercultural professional development – a study about leadership of ECEC staff who learns to learn about parental cooperation].” In Barnehagelærerrollen: Mangfold, mestring og likeverd, edited by Sigrid Bøyum and Hilde Hofslundsengen, 168–186. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Statistics Norway. 2022. “Persons with Refugee Background.” Accessed 8 December. https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/innvandrere/statistikk/personer-med-flyktningbakgrunn.

- Thomson, Pat. 2017. Educational Leadership and Pierre Bourdieu. Edited by Pat Thomson, Helen M. Gunter, and Jill Blackmore. Critical Studies in Educational Leadership, Management and Administration. London: Routledge.

- UDIR. 2017. Framework Plan for Kindergartens: Contents and Tasks. Edited by Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

- UDIR. 2018. Barnehageloven og forskrifter: med forarbeider og tolkninger [The Kindergarten Act and regulations: With preparatory work and interpretations]. Edited by Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. Oslo: Pedlex.

- UDIR. 2023a. The Norwegian Education Mirror 2022. Accessed 23 May. https://www.udir.no/in-english/the-education-mirror-2022/.

- UDIR.. 2023b. Bemanningskalkulator – barnehage [Staffing calculator - ECEC]. Accessed 22.08. https://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/statistikk/statistikk-barnehage/bemanningskalkulator-barnehage/.

- Van Laere, Katrien, and Michel Vandenbroeck. 2017. “Early Learning in Preschool: Meaningful and Inclusive for all? Exploring Perspectives of Migrant Parents and Staff.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (2): 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1288017.

- Wells, Gordon. 2008. “Dialogue, Inquiry, and the Construction of Learning Communities.” In Transforming Learning in Schools and Communities, edited by B. Lingard, J. Nixon, and S. Ranson, 236–256. London: Continuum.