ABSTRACT

This study analyses interactions between pairs of children (aged 4–5) together with their teacher during digital storytelling activities in preschool to explore how children express and negotiate their agency and how teachers respond to it. Theoretically, agency is understood as relational and situated meaning that it stems from, and it is shaped by participation in interactions in specific sociocultural settings. Data include 140 h of video recordings in which participants (10 children and 2 teachers) recreate a familiar story using the application Book Creator. The findings show that, even in these activities that were designed by the researcher and the teachers and had a preliminary framework, children expressed their agency by altering the story plot, negotiating the meaning of their drawings with peers, and exploring the design characteristics of the digital tablets. The teachers and digital tables (including the application) mediated the dynamic process of children’s agency. The study concludes by emphasizing a responsive teaching approach that opens up for and encourages children’s agency.

Introduction

The significance of supporting children’s agency in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) is inextricably linked to children’s rights to be heard and taken seriously in decisions affecting them, as outlined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations Citation1989). Agency entails viewing children as ‘independent social actors’ with rights (James and James Citation2012) rather than viewing them as passive individuals. Children’s agency is also apparent in contemporary ECEC research where children use digital technologies as authors and creators (Palaiologou and Tsampra Citation2018; Rowe and Miller Citation2016; Skantz Åberg, Lantz-Andersson, and Pramling Citation2014; Undheim and Jernes Citation2020; Yelland Citation2018). However, limited research focuses on and analyses children’s agency when digital technologies are used in ECEC settings (Scollan and Farini Citation2020). Additionally, research is needed to investigate interactions within a social setting when children use digital technologies (Miller et al. Citation2017). Thus, this study utilizes Interaction Analysis (IA) to investigate how children express and negotiate agency with peers and teachers during adult-designed digital storytelling activities in preschool. It also aims to expand the notion of responsivity in relation to children’s agency as considered in a contemporary theory of teaching in ECEC, Play-Responsive Early Childhood Education and Care (PRECEC), where agency per se is not initially emphasized (Pramling et al. Citation2019).

Adopting a socio-cultural approach (Vygotsky Citation1998), children’s agency is viewed as a continuous and dynamic process, where children co-construct, contest, and negotiate agency in dialogic interactions with others and the sociocultural context (Edwards Citation2007; Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998; Rainio Citation2008). The study’s context involves adult-designed activities, developed by teachers and the researcher, differing from children-initiated activities. Two points are raised regarding these activities: adult-designed activities have received less attention in research than free play situations (Sairanen, Kumpulainen, and Kajamaa Citation2022) and research frequently investigates agency in situations with minimal adult presence or intervention in children’s interactions (Esser Citation2016). Teachers’ pedagogical practices can either promote or constrain agency based on responses to children’s initiatives (accepting, rejecting, ignoring) that are perceived as essential components of agency during activities (Sairanen, Kumpulainen, and Kajamaa Citation2022). Teachers’ ‘I wonder … ’ formulations are argued as pedagogical strategies encouraging children’s participation and agency (Houen et al. Citation2016). Therefore, this study investigates how children’s agency is expressed and negotiated in adult-designed activities, addressing the research questions: (a) How does children’s agency come to the fore during digital storytelling activities, and (b) How do the teachers’ responses open up for and lead to negotiations of children’s agency?

Previous research

In prior studies on digital storytelling in ECEC, children’s expression of agency is evident as they are positioned as creators of their own stories (Eisazadeh and Rajendram Citation2020; Kervin and Mantei Citation2017; O’Byrne et al. Citation2018). More precisely, using open-ended apps, children negotiated, co-constructed and shared stories, about their identity and activities (Fantozzi, Johnson, and Scherfen Citation2018). When teachers designed digital storytelling activities that allow children to contribute or change the story content, it enhanced motivation and commitment (Merjovaara et al. Citation2020). Even when teachers planned most of the creating process, children suggested including sound in their creations, reflecting their agency (Undheim Citation2020). However, few of these studies, and the studies that generally investigate children’s engagement with digital technologies in ECEC settings, analyze and discuss agency in their data.

When investigating children’s agency with digital tablets, the tablet’s perceived affordances – portability, pictorial modes in applications, and the touch screen that enables content control using fingers (rather than a mouse), facilitated children’s agency (Petersen Citation2015). Observing children’s interactions while using a software designed to develop phonics and literacy skills, Scollan and Farini (Citation2020) contend that children demonstrated agency by co-constructing narratives that integrated both digital and non-digital experiences, because the narratives were driven by their personal choices. Yet, the teacher’s role in relation to children’s agency expressions during participation in activities with digital technologies remains underexplored.

Drawing from developmental psychology and educational practice, Baker, Le Courtois, and Eberhart (Citation2023) argued that playful approaches to learning allow children to express agency in their learning, granting them control, active participation, and enthusiastic engagement in the activity. Pretense as a form of agency has been discussed because children ‘by creating imaginary roles and events … created their own situations, rules and internal logic’ (Wood Citation2014, 14). In a study in China, the Conceptual PlayWorld approach during science activities promoted children’s agency, evidenced by their initiatives, and their responsible and intentional membership (Ma et al. Citation2022). Overall, previous studies emphasize the positive impact of play on children’s agency. Therefore, this study, by implementing digital storytelling activities, considered play-formatted activities (van Oers Citation2014), aims to analyze how children express agency, and explore teachers’ role during these activities.

Theoretical framework

A socio-cultural perspective is adopted that defines children’s agency as relational, contextually and historically situated, shaped by available cultural artifacts (Edwards Citation2007; Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998; Fisher Citation2010; Rainio Citation2008). Agency is viewed as a continuous and dynamic process formed and negotiated during participation in social interactions with peers and/or adults within a specific sociocultural context. From this theoretical standpoint, mediation (Vygotsky Citation1998) is critical because cultural artifacts (e.g. language, signs, digital technologies) along with interactions with other individuals, serve as key factors in shaping human thinking and acting, thereby affecting one’s agency. Alternatively, using Alderson and Yoshida’s metaphor (Citation2016), agency can be seen as a river ‘which reshapes the land (structures) around it, but the land also shapes the course and speed of the river’ (78). Hence, from this perspective children’s agency cannot be explored in a vacuum (Varpanen Citation2019), viewed as an innate ability inherent in all children. It can only exist and unfold in relation to social and material environments where children negotiate their actions, thoughts, and initiatives, and build on the contributions of their peers or/and adults.

It is important to note that different theoretical traditions have employed different interpretations of agency. For example, in childhood studies, children are portrayed as agentic beings actively participating in society’s construction (cf. Corsaro Citation1997; James, Jenks, and Prout Citation1998). From such a perspective, agency is understood as a capacity that all children possess (Varpanen Citation2019). However, current reconceptualization of agency in that field argues for a relational approach to agency based on relational social theories (Esser et al. Citation2016).

In this study, PRECEC theory provides the theoretical foundation for understanding and studying teaching and play in ECEC. Instead of simply providing materials and supervising children, PRECEC conceptualizes teaching in ECEC as responsive to children’s play, understanding, interests, and needs. Teachers who participate in and are responsive to children’s play can promote and facilitate it. According to this approach, teaching is therefore conceptualized as a collaborative activity that is co-constructed by both teachers and children, with all participants being equally important in the teaching process (Pramling et al. Citation2019). Aligning with sociocultural theory on learning (Vygotsky Citation1998), PRECEC offers a theorization of teaching, and more precisely teaching in ECEC that is responsive to play (as if it were). Play is here understood as activities play-formatted (van Oers Citation2014) rather than as separate and particular kinds of activities. Theorized as a triad relationship incorporating teacher, child(ren) and a mutual third, how agency is facilitated through a responsive teaching approach is analyzed in this study. For an elaborate explanation of PRECEC and how it relates to and adds to sociocultural theory, see Pramling et al. (Citation2019). The definition of agency, as clarified above, in PRECEC is taken over from sociocultural theory.

Imagination is a key component for both play and teaching. During play (see also Vygotsky’s [Citation1933] Citation1966 notion of imaginary play), children move between acting and thinking in an ‘as if’ and an ‘as is’ mode (Pramling et al. Citation2019). As if corresponds to an engagement with an imaginary reality, how things could be, whereas as is corresponds to an engagement with the reality as it conventionally is understood. Teaching that is responsive to children’s play and meaning-making requires teachers to shift between as if and as is modes. In play-responsive teaching activities, participants can also engage in what if thinking, which involves anticipating consequences or responses to actions, and considering how changing something might affect the outcome. This type of thinking is more prospective, rather than reflective, as it involves considering what will happen in the future if something is changed (Pramling et al. Citation2019). By encouraging this type of thinking, teachers can help children develop their problem-solving skills and prepare them for future challenges.

Intersubjectivity and alterity are dynamic concepts for analyzing communication, for example in teaching activities. Intersubjectivity is understood as a process of establishing a mutual ground between participants engaging in an activity (here digital storytelling) so that they can coordinate their actions with each other and understand each other. Alterity is understood as displays of diverging viewpoints, voices and perspectives that can drive the activity in a new direction (Pramling et al. Citation2019).

Data and methods

This study is situated within a broader research project focusing on (a) ECEC teaching in bi-/multilingual settings involving digital technologies and (b) advancing PRECEC theory by studying activities in situ. Thus, data are generated from video recordings of ECEC digital storytelling activities. Following the framework of Derry et al. (Citation2010), a deductive approach guided the selection of six 20-minute video recordings which aligned with the research questions and PRECEC theory, to explore children’s agency during teacher-children’s interactions involving digital technologies. To minimize distractions during video recordings and the researcher’s impact, the researcher was not present in the room where the activities were held (cf. Brauner, Boos and Kolbe Citation2018). However, she was responsible for setting up the camera on a tripod in front of the table where participants were seated and started the recording.

Since the study is grounded in PRECEC theory, play-formatted activities (van Oers Citation2014) were designed and implemented using only the open-ended application Book Creator. The researcher selected Book Creator due to its open-ended nature, which aligns with the research’s objectives and introduced it to the teachers and children who were unfamiliar with it. Its features allow users to create diverse content by choosing fonts, colors, layouts, and backgrounds, without strict procedures. Additionally, it supports the integration of multimedia elements like images, video, and voice recordings, facilitating the creation of varied stories and books.

A collaborative process with the teachers was established by recognizing the constraints of their demanding workloads, following their schedule, and aligning activities based on their availability. This approach, in line with Cole and Knowles (Citation1993), focused on respecting teachers’ time constraints and negotiating the nature of their participation accordingly, without requiring equal involvement from all parties. Teachers had autonomy in choosing which story to recreate with children, determine the method of introduction, form children’s partnership, and guide interactions during these play-formatted activities.

Participants and settings

This study took part in an international preschool (ECEC for children whose families are in Sweden for a short time), here called Kidspace (pseudonym), in a large Swedish city. Two preschool teachers, Bella, and Laura, and 10 children between the ages of 4 and 5 (2 girls, 8 boys) are the participants. The criteria for research participation included the preschool’s linguistic diversity, aligning with broader research objectives, and participants’ informed consent, signifying their willingness to participate. For ethical reasons, all participants’ and the preschool’s names are pseudonyms. Kidspace follows the Swedish preschool curriculum, and its pedagogical approach emphasizes that teachers encourage children’s initiatives, decision making and problem-solving. So, while the term ‘agency’ is not explicitly stated in their pedagogical approach, one can say that their approach is intended to promote a process that facilitates what theoretically can be referred to as agency.

For the digital storytelling activities with the children, the main teacher chose to recreate the story ‘Room on the Broom’ using a tablet and the application Book Creator. The story revolves around a kind witch and her cat who, while flying on her broomstick, invite three animals (a dog, a bird, and a frog) to join them. During circle time, the teacher introduced to children some finger puppets (a witch and a cat) representing the book’s characters. She used these finger puppets to remind the children of the story so that they could recreate it since the book had (allegedly) been lost. The book was in the preschool’s library and the children were familiar with the story since they had heard it before. Following this introduction, the teacher led pairs of children into a separate room to participate in the digital storytelling activity, in which they could retell and recreate the story using the application. Despite the activity’s specific framing, the children’s finished books told very different stories than the original one, which is interesting from an agency point of view.

Analysis and ethics

The six video recordings were transcribed, viewed during data-sessions with the researcher’s supervisors (Derry et al. Citation2010), and analyzed using IA, which highlights that the meaning of a conversation emerges from the interaction between participants rather than being predetermined by one of the participants (Jordan and Henderson Citation1995). The utterances and actions of participants are analyzed sequentially to investigate how they respond to and build on the utterances of others, and how they collaboratively engage in the mutual activity. By examining these aspects of interaction, it is possible to gain an understanding of how participants make sense of each other’s contributions and how they work together to create the story. Situatedness is essential for IA, thus information about the specific context in which interactions develop is provided. More precisely, the preschool’s pedagogical approach is briefly introduced (above), and each excerpt is accompanied by a short description to situate the interactions. To facilitate readability, the transcripts use literate conventions.

The excerpts presented in this study have been chosen to illuminate the intricate ways in which children’s agency is manifested within the context of digital storytelling activities. At the same time, they highlight the facilitative role of teachers’ responses in relation to children’s expressions of agency. These selected excerpts are indicative of the overarching six activities under investigation in the sense that all activities end with the creation of a story that deviates from the original, and that the teachers’ participation and how they respond to children’s agency is consistent across all six activities.

The study adheres to the Swedish Research Council’s (Citation2017) guidelines for good research practices and has been granted ethical approval by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (case number 2021-03687). Teachers and children’s parents were provided with an informed consent form that contained comprehensive information about the research process. Children were informed about the research process prior to implementing the activities, including an introduction to the camera and an explanation of its functions to minimize its impact (Flewitt and Ang Citation2020). Participation was entirely voluntary, allowing children the right to discontinue their involvement at any point, as was the case with one participant.

Findings

The following excerpts shed light on findings about how children’s agency comes to the fore during digital storytelling activities that are adult-designed and how teachers’ responses open up for and lead to children’s agency. Three themes (Clarke and Braun Citation2021) are identified from the analysis: children’s agency is exercised and negotiated by (1) introducing new characters and altering the story’s plot, (2) negotiating the meaning of their drawings, and (3) exploring the design characteristics of the digital tablets. How teachers open up for and respond to children’s agency is discussed in the analyses of all of the themes.

Excerpt 1 is situated towards the end of the activity, where teacher Bella together with Leo and Max recreate the familiar story. Both children have introduced new characters (a baby, a pig, a fish, and a dragon) that have altered the plot of the original story.

(1) Children introduce new characters and alter the story.

Excerpt 1

197. BELLA: What do you think about the end of our story? How our story should finish? Max said something about fish and dragon. What do you think?

198. Leo: eeemmmmm

199. BELLA: Until now we have a witch, we have a baby and a pig. So, how are these characters … what can they do at the end of the book?

200. Leo: mmm I want to say the dragon hold the fish up and it was hungry, so it jumped, and he ate water on Max head hahahah (demonstrating the story using his hands).

201. BELLA: So, Max you can colour a little bit about that. You can choose a pen and maybe a colour now (shows again the tools to him). What are you drawing?

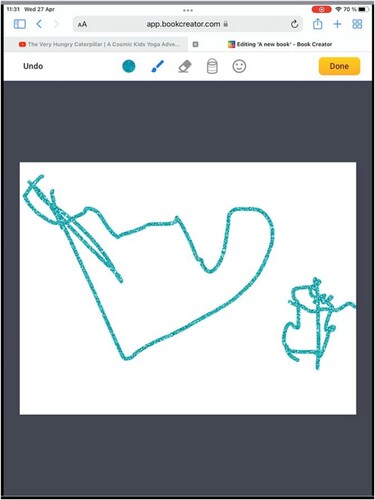

202. Max: heart

203. BELLA: But you said we have a dragon and a fish. What are you drawing now?

204. Max: A motorcycle

205. BELLA: Do we have new stuff in our story?

206. Max: Yes, yeah, I am making new stuff

By using an opinion-seeking questions like ‘what do you think about the end of our story?’, the teacher encourages Leo to suggest an ending to the story, which can be interpreted as an attempt to encourage him to exercise agency (197). Leo responds with a filled pause answer ‘eemmm’ (198), suggesting that he is thinking about his response. The teacher then offers a summary of the previous ideas by stating, ‘until now we have a witch, we have a baby and a pig’ possibly intending to assist Leo in his narration (199). Leo accepts the new characters (the fish and the dragon) that Max has introduced earlier by including them in his narration (200). He alters the story plot and playfully narrates it, acting as if he is the hungry dragon who tried to eat the fish but ended up eating water on Max’s head because the fish jumped (200). The teacher asks Max what he is drawing on the application Book Creator (201), and he responds by adding a new item to the story, a heart () (202). This can be seen as an example of alterity where the child with his drawing suggests a novel direction for the story. Tension between intersubjectivity and alterity is evident when the teacher reminds Max of his previously suggested characters (the dragon and the fish) and asks him ‘what are you drawing now?’ (203). Max responds by altering the story again, including a motorcycle (204). The teacher does not reject his contributions (alterity), but she wonders ‘do we have new stuff in our story?’ since the story evolved and took unexpected turns (205). Max confirms that ‘yeah, I am making new stuff’ (206). Excerpt 1 illustrates how children’s agency is exercised by altering the plot of the original story, ‘making new stuff’, and by playfully acting out the new events that they narrate. The teacher opens up for and is responsive to the children’s manifestation of agency, both by using opinion-seeking questions to encourage their authorship and by supporting alterity when she reminds them of the new story line that they co-create.

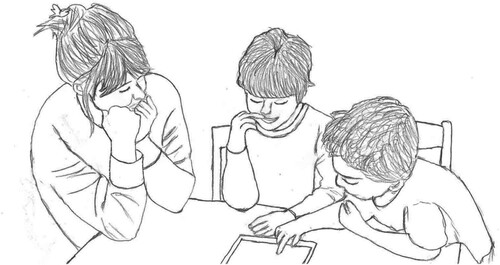

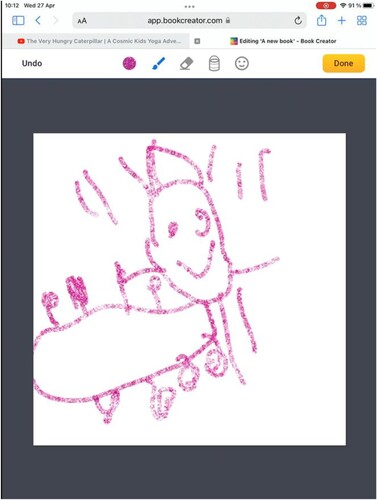

Excerpt 2 (early stage of the activity) shows teacher Laura engaging in digital storytelling with Michael and Steven (), who expressed their agency from the start by suggesting creating a superhero’s book instead of recreating the ‘Room on the Broom’ story. Their suggestion was accepted by the teacher.

(2) Children negotiate the meaning of their drawings.

Excerpt 2

20. LAURA: who is drinking that Coca Cola?

21. Michael: (keeps drawing) Spiderman

22. LAURA: yeah

23. Steven: it doesn’t very look like Spiderman

24. LAURA: it doesn’t very look like him mmm!

25. Michael: Shhhhhhh (playfully moves his face closer to Steven’s face)

26. LAURA: Maybe Michael’s Spiderman looks like that

27. Michael: let him drink (draws)

28. Steven: he says is small (smiles)

29. (Both teacher and Michael laugh)

The teacher tries to make sense of Michael’s drawing by asking ‘who is drinking that, Coca Cola?’ (20). Michael, while drawing, responds that Spiderman is the one who drinks the Coca Cola () (21). Even though the teacher accepts Michael’s character ‘yeah’ (22), Steven expresses his opinion by stating that the drawing does not resemble Spiderman (23). Michael defends his choice in a playful manner, saying ‘shhh’ while moving closer to Steven’s face and saying, ‘let him drink’, as if Spiderman could drink (27). At the same time, the teacher is supportive by justifying Michael’s choice and encouraging his as if thinking ‘maybe Michael’s Spiderman looks like that’ (26). Steven teases his friend once more, this time by adopting his ‘as if’ mode and informing him that Spiderman says that the Coca-Cola is small (28). Both Michael and the teacher laugh as a response to his comment (29). This example illustrates how children negotiate their agency by discussing the meaning of their drawing, and they manage to establish temporarily sufficient intersubjectivity so that they can move on with their story. The teacher is responsive to children’s manifestations of agency by supporting and justifying their own interpretations of the meaning of their drawings.

Excerpt 3 (early stage of the activity) shows Ellen, who previously drew the witch character, drawing lollipops. Earlier, Mark had altered the original story by drawing a guy climbing a fence. Teacher Laura asks questions about their story.

Excerpt 3

66. Ellen: And another lollipop, and another lollipop and she ate all of them at the same time.

67. LAURA: She ate all of them at the same time?

68. Ellen: Yeah (nodding)

69. LAURA: What do you think happened to her, Mark?

70. Mark: She is going to pop

71. LAURA: She is going to pop (smiling surprised)

72. Ellen: No

73. LAURA: What do you think is going to happen to her?

74. Ellen: And then the rain is going to her head (starts drawing the rain)

Ellen draws lollipops that the witch consumed (66), prompting the teacher to ask a clarifying question ‘she ate all of them at the same time?’ (67). After Ellen’s positive response ‘yeah’, the teacher invites Mark to participate by asking him an opinion-seeking question, that encourages him to be a co-author of the story ‘what do think happened to her Mark?’ (69). This action can be interpreted as teacher’s attempt to encourage Mark’s agency. Mark offers his idea that the witch will pop (70), which the teacher repeats with a surprised smile (71). However, Ellen rejects his idea, indicating that she wants to have a say in the direction of the story (72). The teacher responds to Ellen’s rejection by using another opinion-seeking question, ‘what do you think is going to happen to her?’, indicating a willingness to value her perspective and encourage her agency (73). Ellen’s agency is expressed by drawing rain that falls on the witch’s head () (74) rather than accepting Mark’s idea that the witch will pop. This excerpt, along with Excerpt 2, demonstrates the relational aspect of children’s agency, the negotiations that occur when children express their ideas during digital storytelling, and the responses of the other participants. The teacher’s use of opinion-seeking questions creates space for the children’s agency because she allows them to claim authorship of the story they recreate. Also, Excerpt 3 illustrates an attempt by the participants to establish temporarily sufficient intersubjectivity, agreeing on what will happen to the witch after consuming the lollipops, to move forward with their story.

Excerpt 4 (middle stage of the activity) shows teacher Bella, Leo and Max discussing ways of drawing their story using the application Book Creator.

(3) Children explore the design characteristics of the digital tablets.

Excerpt 4

148. Max: Maybe we can draw together?

149. BELLA: That is the plan we want to draw together. Max now Leo can start the drawing (moves the tablet close to him)

150. Max: Or two people can draw

151. BELLA: I do not know if we can do that. Let’s try. Let’s see what Leo will choose for a pen. Do you want to choose a colour too?

152. (Waiting for Leo to choose the pen)

153. BELLA: Do you want to see if two people can draw? I do not think two people can draw.

154. Leo: No, I do not think so.

155. Max: Maybe, we can try

156. Both: yes

157. (Both kids are trying to draw at the same time on the tablet)

158. BELLA: Yeah see, now Leo is not drawing. Is one person. So, let’s see what Leo will do and then Max you can continue. What are you drawing now?

Here, Max suggests testing the design characteristics of the digital tablet and see if two people can draw (simultaneously) together (148). The teacher initially misunderstands Max’s suggestion, as she focuses on the nature of the activity, which is collaborative and requires the children to work/draw together (149). Max clarifies what he means ‘or two people can draw’ (150). Although the teacher is sceptical ‘I don’t know if we can do that’ (151), ‘I don’t think two people can draw’ (153), she is responsive to Max’s suggestion by not rejecting it. Instead, she invites the children to try it out by saying ‘let’s try’ (151), ‘do you want to see if two people can draw?’ (153). Leo and Max engage in negotiations since Leo seems to have doubts about the attempt ‘no I don’t think so’ (154) but Max tries to persuade him ‘maybe, we can try’ (155). Both teacher and Leo agree to give it a try (156). After the children’s attempts to draw simultaneously, they discover that only one person can draw at a time (158). This constraint could be seen as limiting children’s agency because digital tablets with their design characteristics mediate the interaction. However, it can also provide an opportunity for children to learn from the limitations of technology by exploring and trying out different ways/possibilities to achieve their goals. Overall, the teacher’s responses are significant because they show how her language choices open up for the manifestation and development of children’s agency. Also, children’s agency is exercised by being curious and exploring the design characteristics of the digital tablet, and by negotiating if they will test Max’s suggestion.

In Excerpt 5 (towards the end of the activity), teacher Laura and Steven continue creating a superhero’s story without Michael who decided to leave the activity because he wanted a snack.

Excerpt 5

274. Steven: where is white?

275. LAURA: I think this one is very close to white, or this is white as well (points on the screen)

276. Steven: no this is yellow

277. LAURA: mm I think then this one is white (points on the screen). Do you think you will be able to see the white if you draw with white?

278. Steven: (starts drawing with white) I am going first to do that. I couldn’t see anything (moves his face very close to the screen). I will just do (chooses another colour and keeps drawing). He is too big.

Steven wants to draw with white color on the white screen (274). The teacher is responsive to his suggestion by assisting him find the white color (275). However, she also challenges Steven with a question that encourages his ‘what if’ thinking ‘do you think you will be able to see the white if you draw with white?’ (277). Steven starts drawing and testing the white color, but he realizes that he cannot see anything (278). This realization prompts him to change the color and explore other possibilities for his drawing. Excerpt 5 demonstrates how children’s agency is manifested during interactions that are mediated by digital tablets but also constrained by the technical limitations of the application. The teacher’s responsive approach of the child’s manifestation of agency is shown by assisting when Steven needs it while also challenging his ‘what if’ thinking to consider the perceived affordances and constraints of the digital tablet critically and creatively.

Discussion

By studying the social interaction in triads with teacher and children during digital storytelling activities, the study sheds light on how children’s agency comes to the fore and how teachers’ responses open up for and lead to negotiations of agency.

Firstly, the findings show that there is room for children’s agency expressions even in adult-designed activities that incorporate digital technologies and have a preliminary structure/framework introduced to children. Children exercised agency by becoming authors and declaring the authenticity ‘of a personal way of seeing and making sense of reality’ or in this case, a story (Anderson and Macleroy Citation2016, 1). It is noteworthy that they did not merely recreate the familiar story following the initial activity structure; instead, as seen in this study, they engaged in social interactions with peers and the teacher, and their ideas altered the story plot by taking it in whichever direction they imagine, by ‘making new stuff’. The new narratives emerged as a result of the interactions where children accepted (Excerpt 1) or negotiated each other’s contributions (Excerpts 2 and 3). Similarly, in Undheim’s (Citation2020) study, children expressed a desire to include sound in their e-book and movie, and even though teachers did not plan for that, they incorporated their suggestion in the activity.

Secondly, in accordance with the sociocultural perspective (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998) the findings demonstrate children’s agency as a dynamic process emerging and evolving during interactions with teachers and peers in a specific cultural context (an international preschool in Sweden) utilizing cultural tools (tablets and the Book Creator application). The study challenges the notion of agency as an innate ability inherent in all children, because such a view overlooks sociocultural factors and the need for scaffolding and guidance in agency development. Drieschner and Smidt (Citation2023) stress the dual image of the child as both an active participant and a ‘developing, vulnerable child in need of education, whose environment must be responsibly shaped pedagogically’ (32). Thus, the teacher involvement, as observed in this study, is pivotal in fostering and mediating the emergence and growth of children’s agency. Therefore, employing a responsive teaching approach (Pramling et al. Citation2019) towards children’s meaning-making, understanding, initiatives, and play contributions is critical for scaffolding agency development.

Thirdly, the findings illustrate what PRECEC’s notion of responsivity means when it comes to children’s expressions of agency in ECEC teaching that incorporates digital technologies. More precisely, the teachers responded to children’s actions by asking opinion-seeking questions which open up for their contributions during narrative construction and promoted their authorship/agency (Excerpts 1 and 3). They were responsive to children’s alterity – which is understood as expression of agency (Pramling et al. Citation2019) – by meta-communicating what children had previously suggested and reminding them of the storyline that they created (Excerpt 1). They also supported children’s initiatives by accepting their own, different, interpretations of their drawings (Excerpt 2), inviting them to test their suggestions (Excerpt 4), and assisting them regarding the app’s tools (Excerpt 5). Responding to children’s agency can also entail challenging them by asking questions that encourage their ‘what if’ thinking and enrich the activity (Excerpt 5). These findings align with previous research showing that teachers’ pedagogical strategies can enable or prevent children’s agency (Houen et al. Citation2016; Sairanen, Kumpulainen, and Kajamaa Citation2022; Simpson and Walsh Citation2014). Overall, such a responsive teaching approach (Pramling et al. Citation2019) can help foster a sense of ownership and autonomy, as children can be creative, playful and shape their own learning experiences.

Fourthly, the open-ended design of the application Book Creator encouraged expressions of agency because it positioned children as authors and creators. It allowed them to engage in creative meaning-making, by exploring and experimenting with multiple tools and features (Excerpts 4 and 5) with the goal of constructing and developing their own characters and story plots. These findings resonate with earlier research supporting the use of open-ended apps (Flewitt, Messer, and Kucirkova Citation2015; McGlynn-Stewart et al. Citation2017; McGlynn-Stewart, Maguire, and Mogyorodi Citation2020; Palmér Citation2015). However, Excerpts 4 and 5 demonstrate that even though the open-ended design facilitated children’s agency, some design characteristics of the application or the digital tablet limited their initiatives (such as two children drawing simultaneously). Also, teachers’ pedagogical practices may diminish the potential advantages of open-ended applications for agency. This could have happened if the teachers in Excerpts 1, 2, and 3 had not supported the changes introduced by the children (i.e. alterity) and instead insisted on a close recreation of the original story. Digital tablets and applications do not act as independent forces capable of determining children’s agency, an approach known as technological determinism (Stephen and Edwards Citation2018). As seen in this study, they act as mediators alongside teachers or peers during interactions where children’s agency is constantly negotiated.

This study has limitations as it focuses on one preschool and involves a small number of participants. It’s crucial to acknowledge that the context of the setting, notably the encouraging preschool pedagogy regarding developing children’s agency and teachers’ responsive approach towards children’s agency, potentially is significant for the study’s outcome. This realization deserves careful attention when interpreting the study’s findings. The study also underlines the need for caution, drawing upon prior research that highlights instances where teaching strategies prevent children’s agency. Despite the limitations, the study provides valuable insights that contribute to the discourse on how teaching in ECEC can responsively support children’s development of agency when digital technologies are intergraded.

Conclusion

Overall, the contribution of this study lies in exploring how teachers engage with and respond to children’s expressions of agency in the context of digital technologies (here tablets and the Book Creator application), a rarely examined aspect in ECEC research. This research fills a critical gap by empirically clarifying what a responsive teaching approach to children’s agency can entail, aligning with PRECEC’s notion of responsivity. The findings further offer a nuanced approach applicable for ECEC institutions and practice, emphasizing a responsive teaching approach that challenges conventional views of agency as an innate ability inherent in all children. Instead, agency is highlighted as a dynamic, relational process in which the teacher plays a pivotal role in fostering and facilitating its expressions.

Shengjergji_Manuscript (2).docx

Download MS Word (794.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alderson, P., and T. Yoshida. 2016. “Meanings of Children’s Agency: When and Where Does Agency Begin and End?” In Reconceptualising Agency and Childhood: New Perspectives in Childhood Studies, edited by F. Esser, M. S. Baader, T. Betz, and B. Hungerland, 75–88. Routledge.

- Anderson, J., and V. Macleroy. 2016. Multilingual Digital Storytelling: Engaging Creatively and Critically with Literacy. Routledge.

- Baker, S. T., S. Le Courtois, and J. Eberhart. 2023. “Making Space for Children’s Agency with Playful Learning.” International Journal of Early Years Education 31 (2): 372–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2021.1997726.

- Brauner, E., M. Boos, and M. Kolbe. 2018. The Cambridge Handbook of Group Interaction Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Clarke, V., and V. Braun. 2021. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Sage.

- Cole, A. L., and J. G. Knowles. 1993. “Teacher Development Partnership Research: A Focus on Methods and Issues.” American Educational Research Journal 30 (3): 473–495. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163298.

- Corsaro, W. A. 1997. The Sociology of Childhood. Pine Forge Press/Sage Publications Co.

- Derry, S. J., R. D. Pea, B. Barron, R. A. Engle, F. Erickson, R. Goldman, Rogers Hall, et al. 2010. “Conducting Video Research in the Learning Sciences: Guidance on Selection, Analysis, Technology, and Ethics.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 19 (1): 3–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508400903452884.

- Drieschner, E., and W. Smidt. 2023. “Agency and Participation: A Critique of the Epistemological, Psychological, Pedagogical, and Ethical Premises.” In Institutions and Organizations as Learning Environments for Participation and Democracy: Opportunities, Challenges, Obstacles, edited by R. Spannring, W. Smidt, and C. Unterrainer, 17–37. Springer.

- Edwards, A. 2007. “Relational Agency in Professional Practice: A CHAT Analysis.” Actio: An International Journal of Human Activity Theory 1 (3): 1–17.

- Eisazadeh, N., and S. Rajendram. 2020. “Supporting Young Learners Through a Multimodal Digital Storytelling Activity.” Journal of Early Childhood Education Research 9 (1): 76–98.

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103 (4): 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294.

- Esser, F. 2016. “Neither “Thick” nor “Thin”: Reconceptualising Agency and Childhood.” In Reconceptualising Agency and Childhood: New Perspectives in Childhood Studies, edited by F. Esser, M. S. Baader, T. Betz, and B. Hungerland, 48–60. Routledge.

- Esser, F., M. S. Baader, T. Betz, and B. Hungerland, eds. 2016. Reconceptualising Agency and Childhood: New Perspectives in Childhood Studies. Routledge.

- Fantozzi, V. B., C. Johnson, and A. Scherfen. 2018. “One Classroom, One iPad, Many Stories.” The Reading Teacher 71 (6): 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1651.

- Fisher, R. 2010. “Young Writers’ Construction of Agency.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 10 (4): 410–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798410382407.

- Flewitt, R., and L. Ang. 2020. Research Methods for Early Childhood Education. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Flewitt, R., D. Messer, and N. Kucirkova. 2015. “New Directions for Early Literacy in a Digital Age: The iPad.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 15 (3): 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798414533560.

- Houen, S., S. Danby, A. Farrell, and K. Thorpe. 2016. “Creating Spaces for Children’s Agency: ‘I Wonder … ’ Formulations in Teacher–Child Interactions.” International Journal of Early Childhood 48 (3): 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-016-0170-4.

- James, A., and A. James. 2012. Key Concepts in Childhood Studies. Sage.

- James, A., C. Jenks, and A. Prout. 1998. Theorizing Childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Jordan, B., and A. Henderson. 1995. “Interaction Analysis: Foundations and Practice.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 4 (1): 39–103. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0401_2.

- Kervin, L., and J. Mantei. 2017. “Children Creating Multimodal Stories About a Familiar Environment.” The Reading Teacher 70 (6): 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1556.

- Ma, Y., Y. Wang, M. Fleer, and L. Li. 2022. “Promoting Chinese Children's Agency in Science Learning: Conceptual PlayWorld as a New Play Practice.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 33: 100614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2022.100614.

- McGlynn-Stewart, M., T. MacKay, B. Gouweleeuw, L. Hobman, N. Maguire, E. Mogyorodi, and V. Ni. 2017. “Toys or Tools? Educators’ Use of Tablet Applications to Empower Young Students Through Open-Ended Literacy Learning.” In Empowering Learners with Open-Access Learning Initiatives, edited by M. Mills, and D. Wake, 101–123. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2122-8.ch006.

- McGlynn-Stewart, M., N. Maguire, and E. Mogyorodi. 2020. “Taking It Outside: Engaging in Active, Creative, Outdoor Play with Digital Technology.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 23 (2): 31–45.

- Merjovaara, O., T. Nousiainen, L. Turja, and S. Isotalo. 2020. “Digital Stories with Children: Examining Digital Storytelling as a Pedagogical Process in ECEC.” Journal of Early Childhood Education Research 9 (1): 99–123. https://journal.fi/jecer/article/view/114125.

- Miller, J. L., K. A. Paciga, S. Danby, L. Beaudoin-Ryan, and T. Kaldor. 2017. “Looking Beyond Swiping and Tapping: Review of Design and Methodologies for Researching Young Children’s use of Digital Technologies.” Cyberpsychology 11 (3). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2017-3-6.

- O’Byrne, W. I., K. Houser, R. Stone, and M. White. 2018. “Digital Storytelling in Early Childhood: Student Illustrations Shaping Social Interactions.” Frontiers in Psychology 9 (1800) https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01800.

- Palaiologou, C., and E. Tsampra. 2018. “Artistic Action and Stop Motion Animation for Preschool Children in the Particular Context of the Summer Camps Organized by the Athens Open Schools Institution: A Case Study.” International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 17 (9): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.17.9.1.

- Palmér, H. 2015. “Using Tablet Computers in Preschool: How Does the Design of Applications Influence Participation, Interaction and Dialogues?” International Journal of Early Years Education 23 (4): 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2015.1074553.

- Petersen, P. 2015. “«– That’s How much I Can Do!» – Children’s Agency in Digital Tablet Activities in a Swedish Preschool Environment.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 10 (3): 145–169. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2015-03-03.

- Pramling, N., C. Wallerstedt, P. Lagerlöf, C. Björklund, A. Kultti, H. Palmér, M. Magnusson, S. Thulin, A. Jonsson, and I. Pramling Samuelsson. 2019. Play-Responsive Teaching in Early Childhood Education. Dordrecht: Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-030-15958-0.

- Rainio, A. P. 2008. “From Resistance to Involvement: Examining Agency and Control in a Playworld Activity.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 15 (2): 115–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749030801970494.

- Rowe, D. W., and M. E. Miller. 2016. “Designing for Diverse Classrooms: Using IPads and Digital Cameras to Compose EBooks with Emergent Bilingual/Biliterate Four-Year-Olds.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 16 (4): 425–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798415593622.

- Sairanen, H., K. Kumpulainen, and A. Kajamaa. 2022. “An Investigation into Children’s Agency: Children’s Initiatives and Practitioners’ Responses in Finnish Early Childhood Education.” Early Child Development and Care 192 (1): 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1739030.

- Scollan, A., and F. Farini. 2020. “In, Out and Through Digital Worlds. Hybrid-Transitions as a Space for Children’s Agency.” International Journal of Early Years Education 28 (1): 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2019.1695586.

- Simpson, A., and M. Walsh. 2014. “Pedagogic Conceptualisations for Touch Pad Technologies.” The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy 37 (2): 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03651940.

- Skantz Åberg, E., A. Lantz-Andersson, and N. Pramling. 2014. “‘Once Upon a Time There was a Mouse’: Children’s Technology-Mediated Storytelling in Preschool Class.” Early Child Development and Care 184 (11): 1583–1598. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.867342.

- Stephen, C., and S. Edwards. 2018. Young Children Playing and Learning in a Digital Age: A Cultural and Critical Perspective. London: Routledge.

- Swedish Research Council. 2017. Good Research Practice. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet. https://www.vr.se/download/18.5639980c162791bbfe697882/1529480529472/Good-Research-Practice_VR_2017.pdf.

- Undheim, M. 2020. ““We Need Sound Too!” Children and Teachers Creating Multimodal Digital Stories Together.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 15 (3): 165–177. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-943x-2020-03-03.

- Undheim, M., and M. Jernes. 2020. “Teachers’ Pedagogical Strategies When Creating Digital Stories with Young Children.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (2): 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1735743.

- United Nations. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Geneva: UN Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx.

- van Oers, B. 2014. “Cultural-Historical Perspectives on Play: Central Ideas.” In The Sage Handbook of Play and Learning in Early Childhood, edited by L. Brooker, M. Blaise, and S. Edwards, 56–66. London: Sage.

- Varpanen, J. 2019. “What is Children’s Agency? A Review of Conceptualizations Used in Early Childhood Education Research.” Educational Research Review 28, 100288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100288.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1933) 1966. “Play and its Role in the Mental Development of the Child.” Voprosy psikhologii 12 (6): 62–76.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1998. The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky, Volume 5: Child psychology. Edited by R. W. Rieber and translated by M. J. Hall. New York: Plenum.

- Wood, E. A. 2014. “Free Choice and Free Play in Early Childhood Education: Troubling the Discourse.” International Journal of Early Years Education 22 (1): 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2013.830562.

- Yelland, N. J. 2018. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Young Children and Multimodal Learning with Tablets.” British Journal of Educational Technology 49 (5): 847–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12635.