ABSTRACT

This paper offers guidance for remote communication with young children based on an interpretive study of participants engaged in an online Theatre for Early Years (TEY) event, Up and Down. Drawing on practices used for in-person performance, the theatre-makers engaged interactively with children aged 1 and 2 and their accompanying adults through a conference video call. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis was used as an approach to generate themes from observation, and interviews with the parents. Three master themes were generated: Missing Live Performance, Unfiltered Response and Human Connection. The discussion was informed by relational pedagogies and the concept of cultural value. Those engaging with young children through video call software are encouraged to look for ways to create embodied, sensory, and ‘magical’ experiences; collaborate with the adults present; and take a strengths-based approach to the medium.

Introduction

Theatre for Early Years (TEY) is a relatively young art form, defined by the intentional creation and presentation of live performances for audiences of children under school age, including babies and toddlers (Fletcher-Watson Citation2016). The artistic praxis of TEY is multi-disciplinary and multi-modal, united by an interest in young children’s communication and receptivity within an aesthetic context (van de Water Citation2023). This underpins a wide application for TEY scholarship beyond arts-focused spaces. A growing list that includes: pedagogy (Miles and Nicholson Citation2019), support for early relationships (Cowley et al. Citation2020), the realisation of children’s rights (Drury and Ruckert Citation2022), and the professional development of Early Years Practitioners (Starcatchers Citation2016). This paper contributes a digital experience to this conversation, offering new knowledge about how very young children engage with video-call encounters by examining the approach employed by TEY artists in creating an online experience for under 3s and their accompanying adults.

The research for this article took place in Scotland in 2021 when live performances and social gatherings were restricted due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The stimulus event, Up and Down, was an online interactive performance created by theatre makers during the highest level of the UK lockdown. Outside of pandemic conditions, the intentions behind remote communication with very young children include connecting distanced families (Busch Citation2018), and supporting transitions (Oropilla, Ødegaard, and Quinones Citation2022), as well as the sharing of art and culture. Through interrogating the successes and challenges of creating a live performance experience in an online format this paper aims to share insights gained from an unusual time that can usefully be applied to current Early Childhood practice.

Using theories of relational pedagogy (Papatheodorou and Moyles Citation2009) as a framework for discussion it is argued that the responses of the accompanying adults are what enabled engagement and potentially wonder on the part of the child. This is supported by how the artistic offer is planned and presented in a way that is inherently interactive and builds on pre-pandemic work into how relationships with very young children are conducted online (E. McClure and Barr Citation2017) by offering an arts-based perspective. This paper recommends an approach to the video-call medium that imaginatively and practically engages accompanying adults to realise the sharing of embodied experiences.

What is TEY?

Theatre for Early Years (TEY) and Theatre for the Very Young (TVY), are two common umbrella terms used to describe performances created for an intended audience of babies, toddlers and/or pre-school children. Opera, dance, live art, circus, and others are all included, and presentations often blur traditional genre boundaries (SmallSize Citation2023). Shows for children over the age of two or three may be recognisably similar to established children’s theatre, whereas work intended for infants has at times omitted some traditional elements such as character, audience/stage boundaries, or narrative (Fletcher-Watson Citation2013). Levels of interactivity, spontaneity and relationships within the space have been fruitful areas for artistic exploration and practice-based research (Hovik Citation2019; Morley Citation2022; Tse Citation2021). The one consistent aspect of the art form is the presence of very young children and by necessity their accompanying adults. This creates the ‘triangular audience’ (Desfosses Citation2009, 103) of performer, child, and adult, central to this study.

TEY was ‘globally in vogue’ (van de Water Citation2012, 121) at the start of the twentieth century, coinciding with a popular growth of interest in the importance of early childhood experiences e.g. (Gopnik Citation2009; Gerhardt Citation2014). Literature was initially dominated by the perspective of the artist as in the collection of essays edited by Schneider (Citation2009) but there has been a growing interest in applied TEY, evidencing how it can be used within education (Ayles et al. Citation2023)or to support parent–child bonding (Cowley et al. Citation2020). Artistic disciplines blur and overlap within TEY, and other art forms offer complimentary insights into early years arts more broadly, for example, participatory visual arts (Armstrong Citation2021) and gallery visits (Wallis and Noble Citation2022).

How TEY is situated within education and pedagogy

TEY has a nuanced relationship with pedagogy. Fletcher-Watson (Citation2018) found a rejection of educational intent to be a component of artistic integrity for Scottish TEY artists. To an extent this was existential, Fletcher-Watson’s interviewees and the contributors to Schneider’s (Citation2009) book of essays were all carving out a new space in the cultural landscape, it was important to state what one was not. TEY was emerging (and arguably still is) as a distinct form within the established Theatre for Young Audiences sector which has its own, not uncomplicated, relationship with education (Nicholson Citation2014). Reason (Citation2010) in his research on primary-aged audiences observed a split within UK children’s theatre between work being promoted as either entertaining or educational and called for attention to be drawn to work that did not fit easily into either box. The examples of TEY described in Schneider (Citation2009) and more recently van de Water (Citation2023) could be categorised as such; aiming to offer the transporting, high-quality aesthetic experience sought by critics of adult-oriented theatre (Sedgman Citation2018).

A feature of children’s theatre, for any age, that reaches beyond distraction or instruction is a deep respect for the audience (Reason Citation2010). Tse (Citation2021), Hovik and Pérez (Citation2020) and Morley (Citation2022) have each researched practice premised on the aesthetic receptivity of babies, and the ethnographic research of Miles and Nicholson (Citation2019) found the young child to be an agentic and capable audience member. None of which sits at odds with the child-centred, strengths-based pedagogy as articulated in Realising the Ambition, Scotland’s national guidance document for Early Years practice (Crichton et al. Citation2020). Another notable way in which TEY and education practitioners have found fruitful collaboration is through play pedagogies (Broadhead and Burt Citation2012). Productions and projects which build on the playful qualities of TEY e.g. (Allan Citation2019; Armstrong Citation2022; Cowley et al. Citation2020; Katsadouros Citation2018) have offered experiential opportunities to young children whilst boosting the confidence and skills of participating adults. However it is framed, TEY, as a world-expanding, absorbing, a social experience where individuals are expected to make their own interpretations and contributions, cannot help but be a learning environment (Chellini, Rosa, and Frabetti Citation2022). Whether or not it is perceived or promoted as such is culturally mediated and this has implications for the adult-led gatekeeping activities of attendance, promotion, and funding.

Impact

Educational or developmental impact has been used as a marker of value that legitimises cultural activity for the very young (Duffy Citation2006). Where the neoliberal climate demands measurable outcomes for access to limited resources (Sims Citation2017) seeking evidence of worth can be deemed helpful, even necessary. In TEY for the youngest (0–3) one valuing lens has been to ask how a child’s development may be impacted (Dunlop et al. Citation2011), a question fraught with methodological difficulty. That children need positive early relationships for optimal development and long-term flourishing is recognised in the Early Years Framework for Scotland (Scottish Government Citation2009) which includes an economic case for investment in Early Years based on future productivity, referring to the work of Heckman (Citation2007). As seen in Cowley et al.’s (Citation2020) study on TEY being used to promote father–child bonding, influencing parent-carer behaviour can make a case for impacting the child. However, any claims around arts impact, framed as a contribution to a rich home learning environment (Stephen Citation2003) must also include an awareness of access. The material and cultural capital of parents mediates early arts engagement, with cultural capital exerting the strongest force (Becker Citation2014; Mudiappa and Kluczniok Citation2015).

The atomisation of society and emphasis on the individual journey is a trap of neoliberalism (Vallelly Citation2021) that negatively impacts cultural access. A rights-based approach (Unicef Citation1989), such as the one taken by Starcatchers, Scotland’s Early Years Arts Organisation (Starcatchers Citation2022), can challenge this. Upholding the right to participation in cultural and artistic life, as stated in Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Unicef Citation1989), supports arts access in the absence of current, or future financial gain. The essential human value of communal arts experiences (Dissanayake Citation2009; Citation2015) is recognised within a rights-based approach, as in Marinopoulos’ report on ‘Cultural Health’ for the French government which contextualises the ‘artistic awakening’ (Marinopoulos Citation2019, 5) of young children within their communities.

Theoretical framework

From this background, the position taken by this research was to focus on relationships. Children, and their parents, were positioned as agentic, whole persons, contributing to, and being influenced by their communities. Considering children as beings or becomings was considered a useful perspectives, always available, and not dichotomous. Relational pedagogy, with a lineage from Froebel, through Vygotsky (Papatheodorou and Moyles Citation2009), and as articulated as an ambition for current practice in The Child’s Curriculum (C. Trevarthen, Delafield-Butt, and Dunlop Citation2018) provided a framework to describe and interpret interaction. The TEY event, as with all live temporal art, is a co-creation, intersubjectively experienced. Colwyn Trevarthen’s theory of Communicative Musicality (Malloch and Trevarthen Citation2010) provides insight into how aesthetic experiences are available to the youngest of children. Agency and the negotiation of needs within a shared space are ever-present qualities of the audience experience (Fletcher-Watson Citation2013), a framework of playful, relational pedagogy supported the exploration of this tension in a TEY context.

Materials and methods

A qualitative, constructivist paradigm underpinned this study which sought ‘first-hand, individual experience of arts and culture’ (Crossick and Kasznska Citation2016, 7). The research was conducted through video observations and in-depth interviews with Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) guiding the approach to analysis. The interpretive epistemology is one of meaning-making, where credibility and rigour are supported by transparency, veracity and authenticity (Braun and Clarke Citation2020). The researcher and interviewer, Charlotte Allan, was also a co-creator and performer of the work used in the study. This embeddedness and prior experience within TEY was explored reflexively and drawn on an asset to interpretation.

The research was guided by the following questions:

How do adults, bringing a child to TEY, make sense of the experience in the context of their relationship?

What was gained and what was lost in the adoption of digital communication tools?

TEY performance event: up and down

In May 2020 Ipdip Theatre received a commission from Starcatchers to develop a new performance idea for young children in response to the ongoing lockdown. The first iteration of Up and Down was made to specifically connect young children with relatives, usually grandparents, whom they could not currently see in person through shared experiences not reliant on conversation. Ipdip Theatre had previously taken a playful, multi-sensory approach when creating work and the collaborative artists Charlotte Allan and EmmaClaire Brightlyn sought to apply this in a new, online context.

The performers and stage managers were isolated from one another as well as their audience and the world of Up and Down was created as one where a pair of friends invited the audience to join their daily get-together to share stories, songs, and snacks. Mira and Troggle lived in the sky and underground respectively and were able to pass physical objects to one another, and their new friends, ‘through’ the screens. The stage manager supported interactions and the flow of the performance, using functions such as the spotlight feature to control the audience's view. Audience members when signing up were provided with log-in details, and instructions to prepare a yellow object, a snack, and to have a wee scrunched-up piece of tinfoil handy but hidden.

The main points of interaction were as follows:

When Troggle unearths yellow items she then asks the audience to help her dig. They ‘find’ their own yellow objects and show them to her and each other. Mira improvises a song incorporating individual names and their objects.

Audience members are invited to share their snacks with Hoppity the (puppet) rabbit. Troggle reaches outside of the frame to ‘take’ the food which she then feeds to Hoppity.

Everyone can share in a hug on cue, either hugging someone they are with or themselves

Mira drops pieces of silver, from the lining of her clouds, that fall (via an adult audience member) into the outstretched hands of the children.

Materials

presents a summary of the data by source and type.

Table 1. Materials.

Video and audio of the performance event, and follow-up interviews, were recorded through the Zoom software. During the performance adult participants recorded audio using their own mobile devices to capture sound ‘behind the mute button’ during the show. This additional audio was then uploaded to a secure server and for each case, the sound was layered onto a copy of the video for observations of the combined audio and visual to be taken.

Observations on the video recordings merged with home-recorded audio, were made using a table format with columns for the categories of vocalisations, gestures/movements, and emotions. Categorisation was informed by methods used to observe play engagement (Laevers Citation2000) and TEY audiences (Dunlop et al. Citation2011) though no scale was used or quantitative analysis applied. Observations were made at a level of units of action, for example, a movement in response to the speech, and micro-analysis of video was not conducted. This enabled moments of shared attention and emotion to be highlighted, with time stamps aiding contextualisation.

The two-week interval before follow-up interviews was given to allow time for children to respond to the performance through play or other means in their daily lives, and to support the parents’ reflection and interpretations. The interviews were ranging and conversational, stimulated by a schedule which covered the following three areas for discussion:

Remembering the performance to pick out what was considered most important, surprising, or impactful

Imagining how the experience felt for the child, what they might have related to and why

Valuing of the experience for both adult and child in the context of other experiences had together, artistic or otherwise

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Strathclyde School of Education Ethics Committee. Many of the ethical implications, including privacy issues from home recording and monitoring for ongoing assent of young participants (Rutanen et al. Citation2018) were mitigated by the positioning of the parent participants as agentic contributors to the research. This was enacted through building trust and a non-judgmental atmosphere, particularly when it came to discussion on parenting choices and the parent–child relationship. As well as an ethical approach, the positioning of parents as valuable experts in their own experiences and perceptions of their child added veracity to the layered interpretation brought to the analysis. Participant names have been pseudonymized.

Participants

Selection criteria for participation were a parent–child dyad where the child was between 12 and 36 months of age. Only one parent and child were invited for clarity in the observation of interaction. The age range was based on an understanding of early childhood development where children from around 12 months tend to be able to engage in shared observations with adults, secondary intersubjectivity (C. Trevarthen Citation1978), and children over 36 months are likely to have a level of independence that would change the dynamic of the parental presence.

Participants self-selected through responding to a call-out on social media and three dyads were able to take part in the project. On the day this became two dyads and one solo adult as one child was sleeping. All parents were mothers. All three adult participants had experience attending TEY before 2020, two of them with siblings of the study participants and one in a professional capacity. This context informed their online experience, with all interviews including comparisons to in-person events attended in the past. It also contributed to an acute and personal sense of what the children in the study, living under lockdown conditions, were missing.

Process of analysis

Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) belongs to the Thematic Analysis (TA) family, where TA is considered an umbrella term as posited by Braun and Clarke (Citation2020). It originated in the field of psychology and is an iterative approach which makes space for the voice of the researcher, encouraging hermeneutic circling and non-linear engagement with the data (Wagstaff et al. Citation2014). Analysis began during data collection with ongoing notetaking and reflections, valuable for tracking patterns and staying alive to where expectations or assumptions on the part of the researcher are revealed.

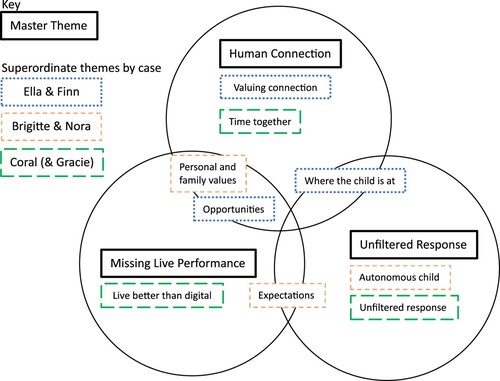

Unlike other TA (Braun and Clarke Citation2013) the cases, i.e. data from the different dyads, were worked on separately and case-level ‘superordinate’ codes were generated, ahead of master themes drawn from the full dataset, as laid out in . Process of Analysis. This was consistent with the IPA approach (Smith Citation2009) and supported coherence when drawing on the different forms of data, as well as keeping the authenticity of the participant's voice at the heart. The case-level superordinate themes are contained within the master themes in a networked fashion, as visually represented in the Venn diagram of .

Table 2. Process of analysis.

Results

Three interconnected master themes were identified in the data, Missing Live Performance, Unfiltered Response, and Human Connection. In Missing Live Performance, elements of what made an art experience with a young child valuable were offered. These elements connected to the other themes, the desire for authentic engagement in Unfiltered Response and the social, moral, and spiritual necessity of Human Connection.

Missing live performance

I think it's always just been a massive part of, our relationship I suppose has been going to the theatre. (Ella, on Finn’s older brother. tp.14)

Live, in-person performances were recollected as transporting, magical experiences, engendering strong emotion and whole-body, hard-to-describe feelings. Up and Down was a different kind of offer. The feeling of liveness was achieved through direct performer to audience interactivity. Realness was supported by performers drawing connections to objects and people through touch and other senses. Reaching into the tangible reality of participants’ homes enabled, in comparison to watching a recorded video, a more embodied experience.

Unfiltered response

Because who am I to say what part of the performance she’s to pay attention to? Why am I deciding what is worthy of the, what’s the part of, the aspect of this experience that ought to have attention paid to it? (Brigitte on Nora 29 m/o tp.37)

That Brigitte could converse freely with Nora meant she was able to acknowledge her child’s curiosity whilst keeping her in time with the rhythm of the performance. Nora’s questions and speculations about the puppet rabbit Hoppity were answered, whilst Brigitte skilfully retained her attention such that she didn’t miss the upcoming ‘magical’ gift from Mira. Similarly, Ella enabled Finn’s engagement by physically responding to his whole body and gestural movements, bringing him back to the screen at times and joyfully acknowledging his pointing, change of gaze, or dancing.

There was a lack of alignment between the researcher’s observations and the mothers’ self-questioning and criticism. In contrast to the observable, positive engagement described above, both Brigitte and Ella expressed concern that they interfered with their child’s authentic engagement by anticipating reactions or directing focus. Observations from the video however showed effective scaffolding on the part of the parents which enabled the children to engage. Had Brigitte not gently redirected Nora’s attention to Mira, she may have missed the magical delivery of the gift which she went on to enthusiastically show her father after the performance. Parental direction also framed the novel experience as safe for the children.

Both Nora and Finn incorporated elements of the performance into their play afterwards. When Finn picked up a pinecone for Ella she engaged with it in the way Troggle had, building on his play through referring to their shared experience. Nora took on ‘dig-dig-dig’ as ‘her new thing’ (Brigitte tp. 47), something which could not have been predicted from the video observation alone as she did not visibly respond to Troggle’s invitation to join in at that moment.

Human connection

And it’s awe, and it’s a wonder, and it's a joy … that sense of wow. It’s really important for all of us, isn’t it? (Ella tp.17)

The intimate nature of home spectatorship provided close one-on-one time, parents noting how this was appreciated by the children who were younger siblings. Love was expressed and returned with bodies close, a child often on the lap. Empathy was both discussed and enacted, parents imagined their children’s perspectives and found joy in the experience of seeing ‘through’ their eyes. This form of looking was enhanced by the ‘self-view’ of the video chat format. When looking at the screen a reflection of themselves was included in the picture. This enabled parents to observe their child’s facial reaction in real-time, a perspective unavailable from a similar sitting position in a live audience.

Care was experienced by the parent of the sleeping child in the form of being seen. Coral expressed in the interview a sense of gratitude that she had not been expected to wake Gracie, and that both their needs were understood and respected.

Discussion

I think the fact that there were actual interactive elements in the performance made it different because that's not something that usually happens when you watch something, and that definitely I think was the most exciting thing for her. (Brigitte on Nora 29 m/o tp.3)

An embodied, sensory experience

Taking a multi-sensory approach increased the extent to which Up and Down felt ‘real’. Often seen in TEY work (Drury and Fletcher-Watson Citation2017) the attempt to meet an audience multi-modally connects to the pedagogy of Reggio Emilia and the ‘hundred languages of children’ (Edwards et al. Citation2011). As well as the usual five senses, including stimulation of bodily senses such as proprioception and balance is part of a whole body approach. In a study with adults, feeling immersed in a shared virtual space enhanced the experience of togetherness, of co-presence (Bulu Citation2012). Immersion for very young children is not an imaginative leap but a whole-body, real-time experience (van de Water Citation2023). Online interactions require thoughtful planning as to what kind of explorations will be made available. The medium privileges two-dimensional images and verbal conversation where adults often have an established level of comfort and proficiency, for other ‘languages’ to be included they must be given additional attention.

TEY is an arena of discovery, not only for the children but artists who explore new ways of engaging audiences (N. A. Tse Citation2021) and parents who learn new things about themselves and their children (Cowley et al. Citation2020). During Up and Down parents were open to how their children responded, taking the opportunity to speculate on their perception and experience. Through both cognitive (Breyer Citation2020) and embodied (De Jaegher Citation2015) empathy, the parent’s view of the child as an interesting, agentic human being was consolidated. This is a key area for future research on the influence of TEY on parent–child bonding and how the voice of the very young child is valued and understood (Drury and Ruckert Citation2022).

Collaborating in the creation of magic

In this context the word magic is used to describe phenomena that do not abide by natural laws, Mira’s silver foil for example travelling through time and space to appear in Nora and Finn’s hands. It is not within the scope of this paper to delve deeply into belief and its suspension, an element of theatre not always found at TEY (Fabretti Citation2009; van de Water Citation2023), what mattered to participants was the element of fun and potential wonder offered. Online TEY may struggle to offer the full aesthetic experience of shared awe cited as a bonding experience by Branner, but the empathetic ‘seeing through [their] eyes’ (Branner and Poblete Citation2019, 87) was still very much present. Parents can support the inclusion of magic and surprise by being recruited as collaborators, in Up and Down this took the form of a request to prepare some objects via an e-mail, other projects could see more longitudinal, personalised, or expanded relationships.

Instructions given to parents to prepare and deploy special effects should be differentiated from the invitations to engage made during the performance. Fletcher-Watson asked if participation at TEY could sometimes take the form of ‘tyranny’ (Fletcher-Watson Citation2015), and it is certainly important to notice where power lies within a performance space. A good question to ask when constructing offers is whether audience members are given permission, either overtly or subtly, to say ‘no’. Refusal tests the principle, for example, Gracie being allowed to sleep or Nora not being coerced into joining in immediately with ‘dig-dig-dig’. Participation freely given respects the voice of the child and supports the creation of conditions where imagination and creativity can flourish (Fumoto et al. Citation2012; C. Trevarthen, Delafield-Butt, and Dunlop Citation2018).

High-quality listening on the part of the performers, and the giving of space for play-based communication and response, commonly found in TEY (Ayles et al. Citation2023; Hovik Citation2014; Nagel and Hovik Citation2016) was restricted by the medium of Up and Down. As the only people bodily present with the child, the parents became vital collaborators in the performers’ efforts to communicate in an attuned way. Parents reported enjoyment in their role as collaborators and described the associated play they engaged in with their children after the event. Though the performer-child relationship (Hovik Citation2019) was a ‘loss’ encountered in digital TEY, there remains the potential in this form of engagement to support parents in their relationships with their children, one area being their confidence and skills in play.

A strengths-based approach

In-person theatre is inherently intersubjective, even in forms without direct interaction the sharing of space forms a relationship between performers and audience. Many children’s theatre practitioners approached the challenge of ‘going digital’ by extending the performance, ahead or beyond the delivery of recorded content, with additional communication (Schoenenberger Citation2021). What emerged in this study as a strength of the technology when working with very young children was the possibility for contingent interaction. Up and Down did not utilise for example green screen technology, animation, or the presentation of pre-recorded video. The elements valued were points where the present, humanness of all those participating was made evident. This aligns with (pre-pandemic) research into video-call use with young children where it was the contingent nature of interaction that set it apart from other screen activity such as television. This was seen in how families viewed the technology (E. R. McClure et al. Citation2015) and in its use as a medium for language learning (Roseberry, Hirsh-Pasek, and Golinkoff Citation2014). Children as young as 12 weeks old have been shown to prefer an in-time, contingent video conversation to a pre-recorded one (Murray and Trevarthen Citation1986; Nadel et al. Citation1999). The children in this study undertook actions such as holding objects up to the screen to show the performers that demonstrated an understanding of video-call functionality. Real connection involves a sense of being seen (Trevarthen Citation1978), and this is made possible in unreal spaces by creating space for the voice of the child (Drury and Ruckert Citation2022).

Summary

Although there can be no doubt that, ‘live theatre can never be fully experienced through a screen’ (van de Water Citation2023, 55), an engaging, interactive experience with value to participants is possible. Up and Down emerged from a specific set of circumstances, a global pandemic where many people, including young children, found themselves having online video interactions for the first time. As the complexity and ubiquity of digital technology continue to increase, its use by and impact on our youngest children is a vital area for ongoing research. This paper argues that a video call with young children and their parents can be enhanced by creatively engaging with interaction that increases a felt sense of shared experience. TEY, in any of its forms, can offer parents a window into the world of their child and a fresh comprehension of their aesthetic capacities. As active participants, but not instigators, in the delivery of wonder, the parents at Up and Down were able to take a double position of watcher and player. Meaningful connection was enabled through space being made for the authentic voice of the child, achieved through adherence to the principle of invitation and not instruction.

The author would like to acknowledge the support given by her academic supervisors and the access provided by Ipdip Theatre, Starcatchers and OneRen, which enabled the inclusion of live performance. Most of all she would like to thank the participants for the generosity and openness of their contributions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allan, Charlotte. 2019. “Calvinball Report: Sharing the Play.” https://www.ipdiptheatre.co.uk/media/documents/Report_on_Calvinball_19.pd.

- Armstrong, Vicky. 2021. “Art Therapy in a Range of Gallery-Based Arts Interventions for the Wellbeing of Parents and Infants.”

- Armstrong, Heather. 2022. “Wee People Big Feelings: Report on Creative Play and Emotional Literacy Project.” https://starcatchers.org.uk/ wp-content/uploads/2023/04/WPBF-Report-1-compressed.pdf.

- Ayles, Robyn, Heather Fitzsimmons Frey, and Jamie Leach. 2023. “Creative Process and Co-Research with the Early Years through Flight.” Performance Matters 9 (1-2): 278–315. http://dx.doi.org/10.7202/1102399ar.

- Becker, Birgit. 2014. “How Often Do You Play with Your Child? The Influence of Parents’ Cultural Capital on the Frequency of Familial Activities from Age Three to Six.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 22 (1): 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2013.865355.

- Branner, Mark, and Mike Poblete. 2019. “Getting Serious about Playful Play: Identifying Characteristics of Successful Theatre for Very Young Audiences.” Arts Praxis 6 (1): 87.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research : A Practical Guide for Beginners. London : SAGE.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2020. “One Size Fits all? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Breyer, Thiemo. 2020. “Empathy, Sympathy and Compassion.” In The Routledge Handbook of Phenomenology of Emotion, edited by Thomas Santo and Hilge Landweer, 429–440. New York: Routledge.

- Broadhead, Pat, and Andy Burt. 2012. Understanding Young Children's Learning Through Play: Building Playful Pedagogies. London: Routledge.

- Bulu, Saniye Tugba. 2012. “Place Presence, Social Presence, Co-Presence, and Satisfaction in Virtual Worlds.” Computers & Education 58 (1): 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.024.

- Busch, Gillian. 2018. “How Families Use Video Communication Technologies During Intergenerational Skype Sessions.” In Digital Childhoods, edited by S Danby, M Fleer, C Davidson, and M Hatzigianni, 17–32. Singapore: Springer.

- Chellini, Claudia, Alessia Rosa, and Roberto Frabetti. 2022. “Grow Up at the Theatre and Through the Theatre.” Giornale Italiano Di Educazione Alla Salute, Sport e Didattica Inclusiva 6 (3). https://doi.org/10.32043/gsd.v6i3.699.

- Cowley, Brenda, Anusha Lachman, Elvin Williams, and Astrid Berg. 2020. “‘I Know That It’s Something That’s Creating a Bond’: Fathers’ Experiences of Participating in Baby Theater with Their Infants in South Africa.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11: 1176.

- Crichton, Vicky, Jean Carwood-Edwards, Janine Ryan, James McTaggart, Janice Collins, Mary Pat MacConnell, Lesley Wallace, et al. 2020. “Realising the Ambition-Being Me: National Practice Guidance for Early Years in Scotland.”

- Crossick, Geoffrey, and Patrycja Kasznska. 2016. “Understanding the Value of Arts and Culture: The AHRC Cultural Value Project.” Arts and Humanities Research Council. https://apo.org.au/node/199546.

- De Jaegher, Hanne. 2015. “How We Affect Each Other: Michel Henry’s’ Pathos-With’and the Enactive Approach to Intersubjectivity.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 22 (1–2): 112–132.

- Desfosses, Agnès. 2009. “Little Ones and Adults, Alive and Aware. Theatre Brings Together.” In Theatre for Early Years: Research in Performing Arts for Children from Birth to Three, edited by Wolfgang Schneider, 99–104. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften.

- Dissanayake, Ellen. 2009. “Root, Leaf, Blossom or Bole: Concerning the Origin and Adaptive Function of Music.” In Communicative Musicality, edited by Stephen Malloch and Colwyn Trevarthen, 17–30. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dissanayake, Ellen. 2015. Art and Intimacy: How the Arts Began. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

- Drury, Rachel C., and Ben Fletcher-Watson. 2017. “The Infant Audience: The Impact and Implications of Child Development Research on Performing Arts Practice for the Very Young.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 15 (3): 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X15614041.

- Drury, Rachel, and Claire Ruckert. 2022. “Where Is the Voice of Scotland’s Babies? Towards an Arts-Based Methodology for Participation with Pre- and Non-Verbal Children (Birth-3).” Norton Park, Edinburgh, September 1.

- Duffy, Bernadette. 2006. Supporting Creativity and Imagination in the Early Years. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Dunlop, Aline-Wendy, Marie Jeanne McNaughton, Deirdre Grogan, Joan Martlew, and Jane Thomson. 2011. “Live Arts/Arts Alive: Starcatchers Research Report 2011.” https://starcatchers.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Starcatchers_Summary.pdf.

- Edwards, Carolyn, Lella Gandini, George Forman, and S. R. L. Reggio Children. 2011. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation. Westport: ABC-CLIO, LLC.

- Fabretti, Roberto. 2009. “Does Theatre for Children Exist?” In Theatre for Early Years: Research into Performing Arts, edited by Wolfgang Schneider, 135–145. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften.

- Fletcher-Watson, Ben. 2013. “Child’s Play: A Postdramatic Theatre of Paidia for the Very Young.” Platform 7 (2): 14–31.

- Fletcher-Watson, Ben. 2015. “Seen and Not Heard: Participation as Tyranny in Theatre for Early Years.” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 20 (1): 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2014.953470.

- Fletcher-Watson, Ben. 2016. “‘More Like a Poem Than a Play’: Towards a Dramaturgy of Performing Arts for Early Years.” PhD Thesis. The University of St Andrews.

- Fletcher-Watson, Ben. 2018. “Toward a Grounded Dramaturgy, Part 2: Equality and Artistic Integrity in Theatre for Early Years.” Youth Theatre Journal 32 (1): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/08929092.2017.1402839.

- Fumoto, Hiroko, Sue Robson, Sue Greenfield, and David J Hargreaves. 2012. Young Children′ s Creative Thinking. London: Sage.

- Gerhardt, Sue. 2014. Why Love Matters: How Affection Shapes a Baby's Brain. 2nd. Routledge.

- Gopnik, Alison. 2009. The Philosophical Baby: What Children's Minds tell us about Truth, Love & the Meaning of Life. London: The Bodley Head.

- Heckman, James J. 2007. “Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children.” Science 312 (5782 (2006)): 1900–1902.

- Hovik, Lise. 2014. The Red Shoes Project. Artistic Research Autumn Forum. Dokkhuset, Trondheim.

- Hovik, Lise. 2019. “Becoming Small: Concepts and Methods of Interdisciplinary Practice in Theatre for Early Years.” Youth Theatre Journal 33 (1): 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/08929092.2019.1580647.

- Hovik, Lise, and Elena Pérez. 2020. “Baby Becomings.” Nordic Theatre Studies 32 (1): 99–120. https://doi.org/10.7146/nts.v32i1.120410.

- Katsadouros, Maria. 2018. The Power of Play: Creating A Theatre for the Very Young Experience. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. University of Central Florida. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6271.

- Laevers, Ferre. 2000. “Forward to Basics! Deep-Level-Learning and the Experiential Approach.” Early Years 20 (2): 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/0957514000200203.

- Malloch, Stephen, and Colwyn Trevarthen. 2010. Communicative Musicality : Exploring the Basis of Human Companionship. Oxford; Oxford University Press.

- Marinopoulos, Sophie. 2019. “A National Strategy for Cultural Health.” French Ministry of Culture.

- McClure, Elisabeth, and Rachel Barr. 2017. “Building Family Relationships from a Distance: Supporting Connections with Babies and Toddlers Using Video and Video Chat.” In Media Exposure During Infancy and Early Childhood, edited by D. N. Linebarger, 227–248. New York: Springer.

- McClure, Elisabeth R, Yulia E Chentsova-Dutton, Rachel F Barr, Steven J Holochwost, and W. Gerrod Parrott. 2015. “‘Facetime Doesn’t Count’: Video Chat as an Exception to Media Restrictions for Infants and Toddlers.” International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction 6: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2016.02.002.

- Miles, Emma, and Helen Nicholson. 2019. “Theatres as Sites of Learning: Theatre for Early Years Audiences.” Education and Theatres 27: 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22223-9_18.

- Morley, Katherine. 2022. “Spectatorship in Theatre for Early Years Audiences: Towards a Working Taxonomy of Stillness.” PhD Thesis. University of Manchester.

- Mudiappa, Michael, and Katharina Kluczniok. 2015. “Visits to Cultural Learning Places in the Early Childhood.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 23 (2): 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2015.1016805.

- Murray, Lynne, and Colwyn Trevarthen. 1986. “The Infant’s Role in Mother–Infant Communications.” Journal of Child Language 13 (1): 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000900000271.

- Nadel, Jacqueline, Isabelle Carchon, Claude Kervella, Daniel Marcelli, and Denis Réserbat-Plantey. 1999. “Expectancies for Social Contingency in 2-Month-Olds.” Developmental Science 2 (2): 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7687.00065.

- Nagel, Lisa, and Lise Hovik. 2016. “The SceSam Project—Interactive Dramaturgies in Performing Arts for Children.” Youth Theatre Journal 30 (2): 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/08929092.2016.1225611.

- Nicholson, Helen. 2014. Applied Drama: The Gift of Theatre. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Oropilla, Czarecah Tuppil, Elin Eriksen Ødegaard, and Gloria Quinones. 2022. “Kindergarten Practitioners’ Perspectives on Intergenerational Programs in Norwegian Kindergartens During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring Transitions and Transformations in Institutional Practices.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (6): 883–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2022.2073380.

- Papatheodorou, Theodora, and Janet Moyles. 2009. Exploring Relational Pedagogy. New York: Routledge

- Reason, Matthew. 2010. The Young Audience: Exploring and Enhancing Children’s Experiences of Theatre. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books Ltd.

- Roseberry, Sarah, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, and Roberta M Golinkoff. 2014. “Skype Me! Socially Contingent Interactions Help Toddlers Learn Language.” Child Development 85 (3): 956–970. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12166.

- Rutanen, Niina, Kátia de Souza Amorim, Helen Marwick, and Jayne White. 2018. “Tensions and Challenges Concerning Ethics on Video Research with Young Children – Experiences from an International Collaboration among Seven Countries.” Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy 3 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40990-017-0013-8.

- Schneider, Wolfgang. 2009. Theatre for Early Years: Research in Performing Arts for Children from Birth to Three. Vol. 13. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften.

- Schoenenberger, Heidi. 2021. “Stay at Home, Engage at Home: Extended Performance Engagement in the Time of COVID-19.” Youth Theatre Journal 35 (1-2): 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/08929092.2021.1891166.

- Scottish Government. 2009. “The Early Years Framework.” https://www.gov.scot/publications/early-years-framework/pages/4/.

- Sedgman, Kirsty. 2018. The Reasonable Audience. Cham: Palgrave Pivot.

- Sims, Margaret. 2017. “Neoliberalism and Early Childhood.” Cogent Education 4 (1): 1365411. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1365411.

- Smallsize. 2023. “Smallsize Brochure 2023.” https://smallsize-virtualhouse.assitejonline.org/hall/.

- Smith, Jonathan A. 2009. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis : Theory, Method and Research. Los Angeles; SAGE.

- Starcatchers. 2016. “Summary Report: Creative Skills Programme 2015–16.” https://starcatchers.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Creative-Skills-Report-15%EF%80%A216-small.pdf.

- Starcatchers. 2022. “Annual Report 2021-2022.” https://starcatchers.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/starcatchers-report-2021-22-FINAL-2.pdf.

- Stephen, Christine. 2003. Meeting the Needs of Children from Birth to Three : Research Evidence and Implications for out-of-Home Provision. Edinburgh: Research, Economic and Corporate Strategy Unit, Scottish Executive Education Department.

- Trevarthen, Colwyn. 1978. “Secondary Intersubjectivity: Confidence, Confiding and Acts of Meaning in the First Year.” Action, Gesture, and Symbol: The Emergence of Language 1: 183–229.

- Trevarthen, Colwyn, Jonathan Delafield-Butt, and Aline-Wendy Dunlop. 2018. The Child’s Curriculum: Working with the Natural Voices of Young Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198747109.001.0001.

- Tse, Natalie Alexandra. 2021. “Creating a Sonic Experience for Babies.” In Visions of Sustainability for Arts Education, edited by B. Bolden and N. Jeanneret, 169–174. Singapore: Springer.

- Unicef. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- Vallelly, Neil. 2021. Futilitarianism: Neoliberalism and the Production of Uselessness. London: Goldsmiths.

- van de Water, Manon. 2012. Theatre, Youth, and Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- van de Water, Manon, Jackie tun Ju Chang, Young-Al Chol, Bruno Frabetti, Roberto Frabetti, Yvette Hardie, Yoona Kang, Katherine Morley, and Klaas Verolancke. 2023. Mapping Research: A Map on the Aesthetics of Performing Arts for Early Years. Bologna: Edizioni Pendragon

- Wagstaff, Chris, Hyeseung Jeong, Maeve Nolan, Tony Wilson, Julie Tweedlie, Elly Phillips, Halia Senu, and Fiona G Holland. 2014. “‘The Accordian and the Deep Bowl of Spaghetti: Eight Researchers’ Experiences of Using IPA as a Methodology.” The Qualitative Report 1–15 (19 (24)): 1–15.

- Wallis, Nicola, and Kate Noble. 2022. “Leave Only Footprints: How Children Communicate a Sense of Ownership and Belonging in an Art Gallery.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30: 1–16.