ABSTRACT

In this paper, we present research into how leaders in early childhood education and care (ECEC) in England conceptualise and respond to sudden and challenging circumstances at organisational and personal levels. A distinction is made in this paper between critical incidents, such as a fire in the kitchen, and crises whereby leaders need to respond to unexpected, long term and evolving events. Although the impact of Covid-19 pandemic was uppermost in participants’ minds, crises emerging from other issues were also investigated. The data informing this study were collected during the first half of 2021, nearly a year after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, with ECEC leaders experiencing drastic changes which extended existing perceptions of crises. The research employed qualitative methodology using interviews with 16 accountable leaders in 13 different settings, with a further interview of a local authority officer with responsibility for advising and guiding multiple settings.

Introduction and context

This paper presents research into how leaders in early childhood education and care (ECEC) in England conceptualise and respond to sudden and challenging circumstances at organisational and personal level. All ECEC providers (except childminders) must comply with the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS), which is the statutory English curriculum framework (DfE Citation2021a) and are subject to inspection by the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted). EYFS sets the standards all providers must meet in terms of children’s developmental goals, health and safety and Ofsted has the power to close the setting if standards are not met.

Providers are required to have safeguarding policies and procedures to keep children safe and meet EYFS requirements (DfE Citation2021a). Staff will have designated responsibilities and roles in these potential crises and there are practices, training and up-dates to ensure readiness, preparedness, communication and checks on the fitness for the purpose of the policies and arrangements.

A distinction is made in this paper between critical incidents and crises. Critical incidents are considered one-off events, usually of short duration, such as a fire in the kitchen which necessitates evacuation. As an incident the event is disruptive and potentially distressing, but is short in duration with the impact being relatively minimal and localised. Afterwards there is a recovery period and time for reflection/review which may involve internal and external stakeholders and lead to changes in policy and practice, resulting in further recommendations, training and updates. After the incident passes, however, lessons are learnt and the settings and those involved move on, with the event often becoming part of history. Crises, however, are considered differently here as being situations where leaders need to respond to unexpected events which are long-term and evolving. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic an Ofsted inspection which rated the provision as Inadequate, resulting in the setting being placed in Special Measures or being required to close, was considered to be highly stressful and ongoing. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic was dramatic, ever-changing, chronic and highly stressful and thus qualified as a crisis of a different dimension.

Towards an understanding of crises and implications for leadership

The literature examining crisis (e.g. Helsloot et al. Citation2013; Topper and Lagadec Citation2013) tends to use the concept to refer to a situation that brings a period of threat, uncertainty, instability and unpredictability. The concept is often used to describe the aftermaths of naturally caused phenomena (e.g. earthquakes, tsunamis, pandemics and volcanic eruptions), but the concept can be also used to describe crisis caused by humans (e.g. accidents or intentionally caused acts such as arson, terrorism and hate crime). All such events can impact on humans’ psychological wellbeing and affect communities and cultures at different levels.

Although what constitutes a crisis is described across different disciplines, there is no consensus of what the term means. From studies prior to COVID-19 a lack of consensus is evident about defining crisis (Alexander Citation2015; Lalonde and Roux-Dufort Citation2013) with research being ‘fragmented, making it difficult for scholars to understand the literature’s core conclusions, recognise unsolved problems, and navigate paths forward’ (Bundy et al. Citation2017, 1611). It is important, therefore, to position ourselves with a definition of crisis to facilitate our research focus and its conceptualisation.

We acknowledge that crises can be seen by some as critical incidents, identifying them as mini-scale, organisational occurrences which are restricted within the boundaries of a specific working environment. According to Shapira-Litchinsky (Citation2011) critical incidents in educational settings, though undesirable, may not involve a lot of tensions: ‘their classification as critical incidents is based on the significance and the meaning the teachers attribute to them’ (649). To locate the COVID-19 pandemic as crisis, however, the definition that is most relevant comes from the work of Pine’s (Citation2017, 1) descriptive and all-inclusive statement:

A crisis is an extreme situation requiring timely decision-making about the response to real or perceived threats and opportunities, often exceeding available resources, and based on limited or unreliable information, with a risk of accountability and personal consequences. Crises arise from the failure to anticipate, understand, and prepare for threats, manifested in emergencies, disasters, and catastrophes, be they social, economic, political, or environmental.

… causes individuals to question all that they think they know about the world, everything that they value, all their actions and priorities to date and for the future and, in doing so, creates an existential crisis in which they have to cope with a sudden vacuum of meaning. (Lacovou Citation2009, 267)

Such drastic measures require leadership as a core condition for these activities to become effective in their implementation and implies, as previously described by Gilpin and Murphy (Citation2008), a level of control and collective administration to coordinate them in crises. We conclude that crisis management requires a quite different approach than incident management, though some procedures may be similar. Pearson and Clair (Citation1998) mention the need for a ‘systemic approach’ when studying and/or managing a crisis; thus, a multi-layered approach is recommended.

Commonly, standard procedures for crises in ECEC settings are embedded within a wider support network in England comprising local authorities and regulatory and funding bodies, with designated officials available for short-term support. Similarly, there are those with expertise in particular aspects of crisis management, such as public health officers, police, fire and social services who can offer support for providers in the event of critical incidents. The most common exception is the crisis precipitated by a poor Ofsted inspection. That is seen as more than a critical incident, is often longer-term and its impact can lead to closure of the setting. For example, if a provider is rated as Inadequate it can be put in Special Measures or be required to close. In that situation the stress is ongoing, with high stakes for the staff and parents involved as the stakeholders’ reaction plays an important part in the possible final outcome.

Some contributors (e.g. Gurr and Drysdale Citation2020) have explored educational leadership appropriate for times of crisis and proposed a model with a central focus on student outcomes (academic, extra- or co-curricular and personal outcomes). Surrounding this model are leadership domains that evolve around setting directions, developing people and the organisation and improving teaching and learning. Such domains reflect the research seen in education into learner-centred leadership (e.g. Leithwood and Sun Citation2012; Leithwood, Harris, and Hopkins Citation2020; Palaiologou and Male Citation2019). In ECEC, however, there is limited research examining the role of leadership in times of crises. In this paper, therefore, we seek to examine the impact of crises and the role of leadership in ECEC settings in England, particularly (but not exclusively) in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The impact of Covid-19

The first cases of Corona Virus emerging from China in early 2020 were not initially recognised by central government or ECEC settings in England as a crisis. It took a few weeks for the realisation of the nature of the virus and its significance to filter through the various agencies. It seems the first real understanding was the national lockdown, which started on 26th March 2020.

By this time many private organisations, companies and higher education institutions in England had already required employees to work from home. Consequently, many parents kept their children at home as participation in ECEC is not mandatory. Some ECEC settings remained open, however, mainly for the children of Key Workers (e.g. doctors, nurses and cleaning staff). During the first lockdown (March to June 2020) only some settings (about 36 percent) remained open with fewer number of children (DfE Citation2021b). The country re-opened briefly at the beginning of June 2020, although local lockdowns remained in place where there were high infection rates. With the infection rate rising steadily through the autumn the country again went into a national lockdown from the 20th of December 2020, although it was announced that children would return to education in January 2021. As lockdowns continued throughout 2021 the picture changed with more providers remaining open, but it never reached 100 percent (Sibieta and Cottell Citation2021), with attendance rates continuing to remain low even when the lockdowns were easing (DfE Citation2021b). The national lockdown ended on 19th July 2021.

One study on the impact of the pandemic concluded that staff were affected at many levels, with consequences on the quality of ECEC for all children (Bonetti and Cottell Citation2021). Other studies showed there to be damaging effects to families and children (e.g. Baker and Bakopoulou Citation2021). The disruption of the everyday life, social isolation and the discontinuation of children’s education increased levels of stress and anxiety impacting on young children’s mental health (YoungMinds Citation2021). Moreover, social and educational inequalities increased (Blundell et al. Citation2020), leading to impact on children’s long-term physical, social, emotional and cognitive development (EPI Citation2020). To conclude, the sector was affected dramatically by COVID-19 and presented great challenges to ECEC leaders.

Theoretical conceptualisation

Building on our previous contributions to the field (Male and Palaiologou Citation2015; Citation2017; Palaiologou et al. Citation2022; Palaiologou and Male Citation2019) we argued that leadership in ECEC settings should be conceptualised as praxis that brings an equilibrium between functions (administrative, management and educational) and structures (styles of leadership, prerequisites of a leader and challenges). We proposed that leadership needed to go beyond the learning and teaching that takes place in ECEC to embrace the community and dimensions that are internal (e.g. values, culture, customs) and external (e.g. global economy, policies, national curricula). For this to be achieved:

… leadership [should be] rooted in its specific context and pay attention to its own environment. (Palaiologou and Male Citation2019, 31)

Physical level: how do we manage our physical space safely?

Social level: despite the distancing how do we relate to others?

Personal level: how do we develop a self-care plan?

Spiritual level: what should be the values we adhere?

Under crisis, leaders must plan strategically, obtain needed resources and coordinate team’s actions. With COVID-19 there was an additional need for leaders to respond to psychological dimensions. Thus, we extended the definition of crisis and proposed that leadership as praxis enables the interplay of contextual and psychological factors that are responsive to the ecology of the community, where the locus of control is internal to the community and responds to the spheres of any given situation.

Our research

We employed qualitative research, carrying out online semi-structured interviews in the first half of 2021 via Zoom. Each interview used the following key prompts:

How crisis can be defined in ECEC

ECEC leaders’ perceptions of crises and/or critical incidents

leaders’ responses to crisis

how contextual changes and constraints affected leading effectively

whether leaders changed their leadership style and/or modified their skills to meet new challenges and adapt to new circumstances

how education stakeholders [teachers and parents] responded to crisis challenge

lessons learnt

This was a convenience sample established through our links with ECEC providers. All participants held various leadership roles, as shown in :

Table 1. Participants.

Our sample of consisted of 16 accountable leaders in 13 different settings, with all settings being in different places and representative of urban and rural areas. An additional interview was undertaken with a local authority officer with responsibility for advising and guiding multiple settings. Consequently, the investigation offers opinions from geodemographically contexts across England.

Most of our participants were women which can be a limitation, but in England ECEC is a female-dominated workforce. Most had more than four years’ experience in the role (except one who started the leadership role during the pandemic) which offers strength to the data as they had experienced leadership prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The project was approved by UCL Institute of Education Ethics Committee (Z6364106) and all participants have been anonymised. We provided all participants with recordings and transcripts for approval, validation and accuracy of our understanding of their perceptions.

Findings and discussion

Definitions of crisis

Like definitions identified in the literature, the participants defined crisis as an incident that ‘upsets’ everyday life:

unforeseen events that create an immediate impact (P 6)

when something happens that will change the way people used to live or do things (P4)

the urgency of the moment takes importance and needs to be dealt outside of the norms of the routine (P7a)

anything that fundamentally changes the lives of children (P8)

The data showed all participants clearly distinguished crisis from critical incidents and ongoing challenges. One participant (P11) mentioned, for example, an ongoing crisis due to the outcome of an Ofsted inspection where she was given notice to close the school, meaning she had to deal with many issues:

… the school was given notice for closure so that was a crisis now none of us had seen coming [which] was very hard on the staff that had already been through a lot and threw us into a situation where we had no idea how to handle something like that. (P 11)

I was working in a setting when a terrorist attack took place. The building went to a lockdown, the police were around, we could not leave the building, the parents could not enter the building and so the children and us were there until very late. (P 3)

I got a text on a Saturday morning that a pig was loose in the school’s playground and I had to attend. The pig just standing behind the school gates, looking up. So how do you deal with this? (P 9)

Responses to Covid-19 crisis

All participants considered the COVID-19 crisis brought chronic uncertainty which made it more complicated in terms of constant changing of policies, extensions to lockdowns and regulations at short notice. The crisis redefined their relationships with parents, children and staff, an outcome for which one key term was ‘challenging’.

In England during the lockdowns where the ECEC setting stayed open, they adopted the Bubble System where staff and the children stayed within their group and were not interacting with other groups. The leaders had their own bubble which isolated them from children and staff. It is interesting that the interview with P7 had three leaders from the same setting who came to the Zoom interview from different rooms.

Despite the drastic changes and challenges that this crisis brought all participants stated many lessons were learned that strengthened their leadership skills, as exemplified by the following statement:

Despite somehow that the world, our world, came apart, I feel in a strange way we all came together, stopped ‘bickering’ as before Covid and overcame difficulties as a team. We became more attentive and understanding. (P 7a)

Contextual challenges affecting organisational processes

Parental relationships, where communication was a major issue: At the start of the lockdowns parents indicated communication was decreased. As it became obvious the crisis would last longer than anticipated, leaders started to develop methods to stay in touch. Phone calls, online platforms and emails were major mechanisms employed which led to increased contact, allowing parents to ‘control their anxiety’ (P10). As communication increased, mutual trust and understanding were enhanced, as exemplified by P13: ‘we learnt to trust the parents and parents learnt to trust us’. Finally, and unexpectedly, all participants mentioned that transitions had changed. In the past the parents were invited into classrooms and stayed as long as needed. With the Bubble System, however, on arrival parents were leaving their children at the main entrance of the ECEC setting. Participants noticed that children were not crying during the separation from their parents or, if they did, it did not last long. Consequently, this made all but two of the participants reflect on transitions’ process for the future and retain the process of separation of parents from children at the main entrance.

‘Lost Childhood’ effects: The main effect on children mentioned by all participants was on their development. One participant (P 12, the participant overseeing 31 nurseries) told us, for example, that some children, especially the ones who were living in flats where physical opportunities were limited during lockdowns, stayed for long periods of time when they arrived in the setting staring at the room and ‘not knowing how to act in open spaces’. She continued: ‘we also showed more referrals for speech and language delays and autism’. Another (P 6) mentioned that the toilet habits of children were difficult to manage when they came back, even with children who were in the setting before COVID-19. Finally, nine participants mentioned the listening skills of the children and observed that when children returned they were ignoring instructions, were not paying attention to the rules and were not being patient in waiting whilst someone finished what she or he was saying. All participants also raised similar concerns for language development and delays in assessing children for special needs. An interesting finding was children had difficulties in demonstrating skills that are needed in play, especially in social playChildren stayed in parallel play much longer than was expected. (P 7c)We saw children engaging more in parallel play. They did not know how to wait for their turns, or share, were disturbed with noise and easily distracted, demanding attention from the adults as at they had been at home for long period of time and had their parents’ attention and fighting more frequently. (P 10)They were not asking, they were grabbing whatever they wanted from other children and running away without asking as at home they did not have to wait to play with a toy. It was like a regression in front of our eyes as they moved and behaved ‘like babies’, more toddler behaviour that you expect from three- and four-year olds, even children that attended the nursery prior to COVID-19, came back so different. (P 11)

There are babies that have been born and they have not seen other children, there are children that have not played with other children for more than a year, they could not go to parks or playgrounds, museums or do activities that they were available before. (P 2)

Relationships with and among staff: The key challenges were anxieties, fear of getting ill, not being able to work as they were classified as vulnerable groups, staff getting ill from COVID-19 and isolation as they had to be in their own bubble, so the social element of being in a workplace was lost. The participants mentioned that sustain balanced and effective relationships became:Hard work [as} constantly I had to empower my staff, always validate their work, relying on middle leaders, although they took more responsibilities that normally they would not, try to work on the same goal, and listening to their needs. Having said that it left me exhausted and I was feeling very tired, especially as going home, I could not escape, see friends or go out for a meal. (P 7b)

Maintaining relationship with the community and other services: Traditionally, in ECEC, relationships with the community are important, with visits to local parks, fire stations, swimming pools and other local facilities. Also, it was common for people from the community¸ (e.g. fire services and police force) to come to the setting, but due to the physical distancing rules this was lost. There was consensus that the relationships with the community were important, but the nature of these relations was not the same and, in some cases, became non-existent. Relationships with other services (e.g. educational psychologists, social workers) also became difficult. Consequently, there were delays in diagnostic assessment of children or in addressing serious social related issues (e.g. abuse).

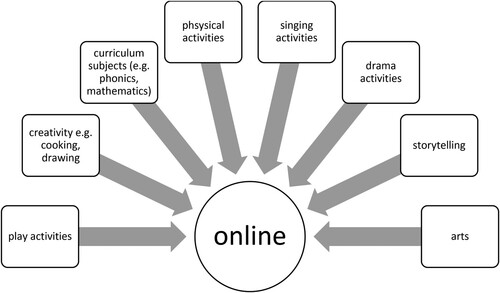

Changed learning and teaching practices: Traditionally in England the use of technologies in ECEC settings has been limited to digital cameras and tablets, with many not being connected to the internet for safety. During the pandemic, however, the need to rely on online platforms to stay connected with the children and their families became essential. It was a consensus that ‘without technology we could not have been able to keep the school moving’ (P8). Consequently, several practices were developed as shown in .

Four setting leaders highlighted, however, that the digital gap sometimes widened due to the gaps in inequality between families and settings, leaving them with the considerable challenge of finding ways to bridge this gap and provide accessibility to the families for the resources. For example, some working parents wanted the children to be at ECEC settings so that they could work from home, but others kept their children at home, with the families taking responsibility for the teaching role and being able to create rich learning environments and opportunities. The settings started preparing resources and sending them to the families. These included story sacks, resources boxes with activities and suggestions on what they can do at home or preparing and delivering online activities.

It was evident the adaptation of teaching and learning practices was a ‘steep learning curve for staff in being able to create and share resources, but also became more creative with treasure hunts, using Facebook, reading stories online and using social media to communicate and provide support for families’ (P 8).

The effects on leaders: It became evident that leaders themselves were affected. Firstly, they all agreed that the workload was high and as a result they felt tired and exhausted, going to the setting energised them as they could not imagine how life would have been if working from home. It was for them emotionally difficult as well and often overwhelming and stressful. There was a consensus, however, that what kept them going was their duty to provide for the children. As support mechanisms they all had their networks to discuss issues, share challenges and solutions, but it was clear that this crisis all felt challenged and stretched their abilities to the maximum.

Lessons learnt and ways forward to the future

Participants concluded the COVID-19 pandemic forced them to reflect on their leadership style, with all indicating they had become more empathetic with their staff. Leaders had learnt that even though they worried for the unknown, they had to be patient and support or even ‘teach people’ (P14) to cope with the unknown and unpredictable in the search for solutions.

All participants commented on the emotional load they experienced during COVID-19 having to cope with the daily crisis in their settings which gave them very little space to ‘breathe, rest and distance [themselves] between school and family life’ (P5). The key emergent message was to ‘distance emotions’ (P14) and ‘keep going’ (P1). There was consensus, as evidenced by the following contributions, that the changes ‘made [us] think of new ways of working with people’ and they had to exercise ‘brave leadership’ to respond to the continuous crisis by ‘taking risks and pray for the best’ (P7a).

Conclusions

From the findings, it was evident that although our participants felt prepared to deal with critical incidents, they were not expecting such a worldwide scale crisis as the COVID-19 pandemic which was ongoing and rapidly changing. This had multiple effects on both the way they managed their setting and their leadership style, leading them to make fundamental changes to the organisation of children’s learning and relationships with other key stakeholders, many of which they aim to sustain in a post-pandemic era. The Covid-19 pandemic induced unparalleled pressures on our participants, but to which they responded admirably. The outcomes we witnessed lead us to pay tribute to their resilience and determination, seemingly driven by the moral desire to provide the best learning environment for the children of the community they serve, summed up as follows:

We need to focus on children and their education, wellbeing and not about producing endless paperwork. At the end of the day, I think this crisis made me think that leadership style will be no more about what the real job is, but about developing curriculum and looking at the way you want to take your school on and what you actually want for your community [original emphasis] long term. (P 8)

In that sense, the psychological dimensions of leadership should not be ignored. Leadership as praxis is about acting consistently with ethical decision making, sensitivity, empathy and courage being exhibited when situations, such as crises, require instant actions. The closest approaches to human-centred leadership are Authentic or Compassionate leadership (e.g. Avolio, Gardner, and Walumbwa Citation2005; Beddoes-Jones and Swailes Citation2015) which seek to develop a synergy between psychological self and philosophical self (Novicevic et al. Citation2006).

To conclude, we argue that leadership is praxis when the psychological and the contextual dimensions are an interplay that is responsive to the ecology of the community. Our findings demonstrated this definition can be extended even further. Thus, we propose that leadership as praxis enables the interplay of contextual and psychological factors that are human-centred and responsive to the ecology of the community, where the locus of control is internal to the community and responds to the impact of any given situation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alexander, D. 2015. Disaster and Emergency Planning for Preparedness, Response, and Recovery. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.12.

- Avolio, B. J., W. Gardner, and F. O. Walumbwa. 2005. “Preface.” In Authentic Leadership Theory and Practice: Origins, Effects and Development, edited by W. Gardner, B. J. Avolio, and F. O. Walumbwa, 11–19. San Francisco: Elsevier.

- Baker, W., and I. Bakopoulou. 2021. “Examining the Impact of COVID-19 on Children’s Centres in Bristol.” British Educational Research Association, Report Series: Education and COVID-19.

- Beddoes-Jones, F., and S. Swailes. 2015. “Authentic Leadership: Development of a New Three Pillar Model.” Strategic HR Review 14 (3): 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-04-2015-0032

- Blundell, R., M. Costa Dias, R. Joyce, and X. Xu. 2020. “COVID-19 and Inequalities.” Fiscal Studies 41 (2): 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12232

- Boin, A., S. Kuipers, and W. Overdijk. 2013. “Leadership in Times of Crisis: A Framework for Assessment.” International Review of Public Administration 18 (1): 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2013.10805241

- Bonetti, S., and J. Cottell. 2021. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Early Years Settings and Their Staffing Decisions.” British Educational Research Association, Report Series: Education and COVID-19.

- BSI. 2011. Crisis Management. Guidance and Good Practice. London: British Standards Institution.

- Bundy, J., M. Pfarrer, C. Short, and T. Coombs. 2017. “Crises and Crisis Management: Integration, Interpretation, and Research Development.” Journal of Management 43 (6): 1661–1692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316680030

- Department for Education [DfE]. 2021a. Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) Statutory Framework. Accessed 05 January, 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-foundation-stage-framework–2.

- Department for Education [DfE]. 2021b. Attendance in Education and Early Years Settings During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak. Accessed 09 January, 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/attendance-in-education-and-early-years-settings-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak.

- Education Policy Institute [EPI]. 2020. Preventing the Disadvantage Gap from Increasing During and After the Covid-19 Pandemic: Proposals from the Education Policy Institute. Accessed 9 January, 2024. https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/disadvantage-gap-covid-19/.

- Gilpin, D., and P. Murphy. 2008. Crisis Management in a Complex World. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gurr, D., and L. Drysdale. 2020. “Leadership for Challenging Times.” International Studies in Educational Administration 48 (1): 24–30.

- Helsloot, I., A. Boin, B. Jacobs, and L. Comfort, eds. 2013. Mega-crises: Understanding the Prospects, Nature, Characteristics and Effects of Cataclysmic Events. Springfield: Charles Thomas Publications.

- Lacovou, S. 2009. “Are Well-being, Health and Happiness Appropriate Goals for Existential Therapists?” Existential Analysis 20 (2): 262–275.

- Lalonde, C., and C. Roux-Dufort. 2013. “Challenges in Teaching Crisis Management: Connecting Theories, Skills, and Reflexivity.” Journal of Management Education 37 (1): 21–50.

- Leithwood, K., A. Harris, and D. Hopkins. 2020. “Seven Strong Claims About Successful School Leadership Revisited.” School Leadership and Management 40 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

- Leithwood, K., and J. Sun. 2012. “The Nature and Effects of Transformational School Leadership: A Meta-analytic Review of Unpublished Research.” Educational Administration Quarterly 48 (3): 387–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X11436268

- Male, T., and I. Palaiologou. 2015. “Pedagogical Leadership in the 21st Century: Evidence from the Field.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 43 (2): 214–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213494889

- Male, T., and I. Palaiologou. 2017. “Pedagogical Leadership in Action: Two Case Studies.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 20 (6): 733–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2016.1174310

- Novicevic, M., M. Harvey, M. Ronald, and J. Brown-Radford. 2006. “Authentic Leadership: A Historical Perspective.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 13 (1): 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/10717919070130010901

- Palaiologou, I., E. Argyropoulou, M. Styf, C. Arvidsson, A. Ince, and T. Male. 2022. “Pedagogical Leadership: ‘Comparing Approaches and Practices in England, Greece and Sweden’.” In Pedagogical Leadership in Early Childhood Education: Conversations Across the World, edited by M. Sakr and J. O’Sullivan, 69–78. London: Bloomsbury.

- Palaiologou, I., and T. Male. 2019. “Leadership in Early Childhood Education: The Case for Pedagogical Praxis.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 20 (1): 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949118819100

- Pearson, C., and J. Clair. 1998. “Reframing Crisis Management.” Academy of Management Review 23 (1): 59–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/259099

- Pine, T. 2017. Preparation for the Novel Crisis: A Curriculum and Pedagogy for Emergent Crisis Leadership. University of Hertfordshire. Doctorate Dissertation. https://doi.org/10.18745/th.20539

- Shapira-Litchinsky, O. 2011. “Teachers’ Critical Incidents: Ethical Dilemmas in Teaching Practice.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (3): 648–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.11.003

- Sibieta, Luke, and Josh Cottell. 2021. Education Reopening and Catch-up Support Across the UK. London: Education Policy Institute.

- Topper, B., and P. Lagadec. 2013. “Fractal Crises: A New Path for Crisis Theory and Management.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 21 (1): 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12008

- YoungMinds. 2021. Coronavirus: Impact on Young People with Mental Health Needs. Accessed 9 January, 2024. https://www.youngminds.org.uk/about-us/reports-and-impact/coronavirus-impact-on-young-people-with-mental-health-needs/.