ABSTRACT

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are part of 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SD) that aim to eradicate poverty, achieve economic prosperity, gender equality, ensure social well-being, promote sustainable management and use of natural resources, and protect the Earth’s natural ecosystems. However, the occurrence of human–wildlife conflict (HWC) may impair SDGs to be achieved in developing regions where people and wildlife cooccur frequently. Surprisingly, there are few studies which have examined how HWC impedes achievement of SDGs. This paucity of information hinders the formulation and implementation of appropriate policy actions to achieve SDGs. We explored how HWC impacts on the livelihoods of rural communities in Bhutan through SD lens. We used a mixed method research approach and interviewed a stratified-random sample of 96 farmers from four different regions of Bhutan. Wildlife impacts are multidimensional and can inhibit achievement of several SDGs. All interviewees suffered crop and livestock depredations with substantial economic losses. These losses were higher for female-headed households and those with low asset holding, compounding their vulnerability. Among the HWC adaptation measures, adopted guarding, vigilant livestock herding, and electric fences were perceived effective but were predominantly applied by households in high asset class. Policy actions should focus on female-headed households and those families with lower asset category to reduce negative impacts of human wildlife interactions.

Introduction

The concept of sustainable development (SD) grew out of the ‘Limits to Growth’ debate of the early 1970s (Pezzey Citation1992) and has evolved into the current suite of sustainable development goals (SDGs). SDGs were set in 2015 as a further call to action for countries to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity (Agarwal Citation2018). The 17 SDGs have 169 targets to be met by 2030 (UN Citation2015), many of which are interlinked (Stafford-Smith et al. Citation2017). Achieving SD is required for societies to achieve prosperity without threatening planetary boundaries (Le Blanc Citation2015; Steffen et al. Citation2015). Though ambitious, SDGs provide a roadmap for helping all countries, including developing ones, transition to SD through the integration of environmental and social impacts into economic development (Yangka et al. Citation2018). However, this may be made more difficult because of the interactions among SD targets which may lead to conflicting outcomes such as human wildlife conflict (HWC), impairing achievement of several SDGs (Anderson et al. Citation2021).

In many biodiversities rich, but economically poor regions of the world, the key to achieving SDGs is through improving the livelihoods and incomes of the rural poor without degrading ecosystems (Mmbaga et al. Citation2017; Killion et al. Citation2021). The pathway to achieving SDGs in many of these regions is, however, made more difficult by the occurrence of HWC. HWC is defined as occurring ‘when the needs and behavior of wildlife impact negatively on the goals of humans (economically, physically, psychologically) or when the goals of humans negatively impact the needs of wildlife’ (Madden Citation2004). HWC is therefore as much of a sustainable human development problem as it is a biodiversity conservation issue (Nyirenda et al. Citation2018; Gross et al. Citation2021).

In Bhutan, sustainable human development and biodiversity conservation are the central strategic policy themes with high priority in the national development plans (Yangka et al. Citation2018). The Bhutanese version of SD is guided by the philosophy of Gross National Happiness (GNH) which emphasizes that development pathways must be socially, economically, environmentally, and culturally sustainable (Martin and Rice Citation2014; Yangka et al. Citation2018). GNH is thus a living development model (Verma Citation2017) and upheld as the alternative model for achieving SD (Brooks Citation2013). This unique approach to development via GNH is being facilitated by Bhutan Government as a tool to balance poverty alleviation, environmental conservation, and SD.

This study is motivated by the contextual nature of the progressive conservation policies and the high dependence on agriculture in Bhutan to investigate the connection between HWC and SDGs. Bhutan has a predominantly agrarian society with 60% of the total population depending entirely on agricultural farming, livestock husbandry, and collection of non-timber forest products (NTFP) as main livelihood sources (NPPC Citation2016). Currently, about 71% of Bhutan’s geographic land area is under forest cover (FRMD Citation2020) and 51.4% of the land area is designated as a protected area (DoFPS Citation2016). The constitution of the Kingdom mandates that the country maintains 60% of its total land under forest cover into perpetuity. According to the legal framework for conservation, the Forest and Nature Conservation Act of Bhutan, all wildlife and wild plants listed in Schedule I are fully protected, while other wildlife, not listed in Schedule I, are also afforded protection and may not be killed, injured, destroyed, captured, or collected. This Act allows people to reside within protected areas with restrictions on traditional resource uses and a ban on hunting. Since these conservation policies were enacted an increase in wildlife populations within protected areas has been perceived (NCD Citation2008) and is hypothesized as a major driver of HWC in Bhutan (Karst and Nepal Citation2019).

Achieving SD in Bhutan, and other regions with high dependence on subsistence and smallholder agriculture requires sufficient knowledge of the underlying factors that drive HWC and how these vary within and between communities and regions. Previous HWC studies in Bhutan (Sangay and Vernes Citation2008; Thinley and Lassoie Citation2013; Katel et al. Citation2014; Tshering and Thinley Citation2017; Wangchuk et al. Citation2018; Jamtsho and Katel Citation2019; Tobgay et al. Citation2019) have not considered the connection between HWC and SDGs and surprisingly, there are only few studies (Digun-Aweto and Van Der Merwe Citation2020; Gross et al. Citation2021) globally which have examined how HWC impinges upon the achievement of SDGs. The purpose of this study therefore is to explore this relationship and fill this knowledge gap.

This study aims to assess the effects of wildlife impacts on subsistence farmers’ livelihoods and to investigate how gender and wealth impact on vulnerability and capacity of subsistence farmers to implement HWC adaptation measures to prevent crop, livestock, and property losses. The following research questions guided this exploration:

What is the impact of wildlife on subsistence farmers’ livelihoods?

How do HWC impacts, and capacity to adopt HWC adaptation measures, vary between different wealth groups?

How do HWC impacts, and capacity to adopt HWC adaptation measures, vary between male and female-headed households?

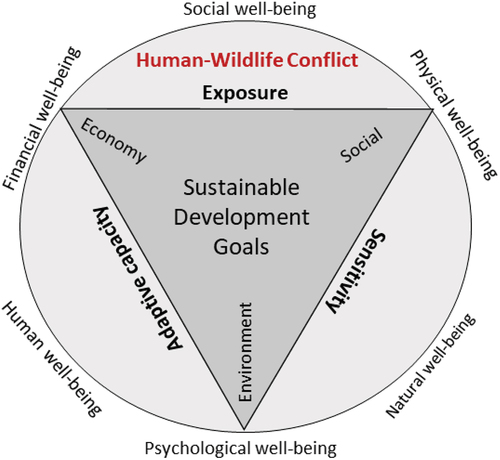

Conceptual framing: HWC and SD

This study draws upon the SD framework with the triple bottom line (TBL) concept of social, economic, and environmental sustainability (Tomislav Citation2018) and vulnerability theory (Zakour and Gillespie Citation2013) with its components of exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity as conceptualized in . Social, economic, and environment are the three pillars of SD. Maintaining the balance between these three pillars is important for achieving SDGs (Tomislav Citation2018). In the context of social livelihoods, sustainability denotes ‘the ability to maintain and improve livelihoods while enhancing the local and global assets and capabilities on which livelihood depends’ (Chambers and Conway Citation1992). SD in the context of subsistence livelihoods may be secured through the ability of subsistence farmers to efficiently protect themselves and their assets (e.g. crop, livestock animals, properties) from wildlife damages. On the other hand, crop farming, livestock husbandry, and collection of NTFPs from the forest as livelihood sources for subsistence farmers should not have any negative impacts on the environment and/or the wildlife in it (Mmbaga et al. Citation2017; Nyirenda et al. Citation2018). A sustainable livelihood is that: ‘which can cope with and recover from stress and shocks, maintain and/or enhance its capabilities and assets, and provide sustainable livelihood opportunities for the next generation; and which contributes net benefits to other livelihoods at the local and global levels and in the short and long term’ (Chambers and Conway Citation1992, p. 6).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of sustainable development (SD) illustrating a situation where subsistence farmers and their assets are exposed to HWC and the vulnerability of subsistence farmers’ livelihoods to HWC impact is influence by their sensitivity and adaptive capacity.

Vulnerability has been conceptualized in different ways (Adger Citation2006). When vulnerability is viewed as an ‘end point’, it is to estimate and reduce the cost of hazard events. Vulnerability is also viewed as a ‘starting point’ to characterize individuals, households, communities, or nations into their differential susceptibility to hazards (Bennett et al. Citation2019). In this study, we conceptualized vulnerability as ‘starting point’ and by which we seek to identify and describe the susceptibility of subsistence farmers to losses from wildlife and thus food insecurity. Subsistence farmers, in landscapes where wildlife and people frequently co-occur, are impacted by HWC economically, physically, socially, and psychologically (Barua et al. Citation2013; Khumalo and Yung Citation2015; Seoraj-Pillai and Pillay Citation2016; Yeshey et al. Citation2022), inducing a wide range of social, economic, mental, and physical health-related shocks and stresses. These shocks and stresses are stimulated through both perceived and/or real depredation of crop and livestock and/or destruction of properties and/or attacks on people (Mwangi et al. Citation2016). Negative wildlife impacts are disproportionally distributed between individuals and groups of people within same landscape. Within the same social system, different consequences (i.e. impacts) of the same magnitude of disaster can occur (Zakour and Gillespie Citation2013). The impacts are greater on those people who lack the capabilities to either absorb the impact of losses or to protect themselves and their assets against wildlife (Dickman Citation2010; Khumalo and Yung Citation2015), thereby compounding their vulnerability.

In the subsistence livelihood context, subsistence farmer’s vulnerability can therefore be articulated as a function of (1) exposure, (2) sensitivity, and (3) adaptive capacity to cope with HWC-related risks, shocks, and stresses (Baca et al. Citation2014; Nyirenda et al. Citation2018). In this study, exposure refers to subsistence farmers and their assets encountering wildlife. Sensitivity implies to what extent and how subsistence farmers respond to wildlife impacts. Adaptive capacity (AC) relates to the ability of subsistence farmers to respond to and cope with wildlife impacts where AC is considered as a function of wealth, education, information, skills, and access to resources (Shah et al. Citation2013). More importantly, vulnerability is considered as gendered (Enarson and Morrow Citation1998) as within communities, wildlife impacts were felt more deeply by female-headed households. For instance, in parts of India (Gore and Kahler Citation2012; Doubleday and Adams Citation2020), India (Chowdhury et al. Citation2016), and Namibia (Khumalo and Yung Citation2015) women were found to suffer greater HWC impacts.

Research methodology and the context

Bhutan geography

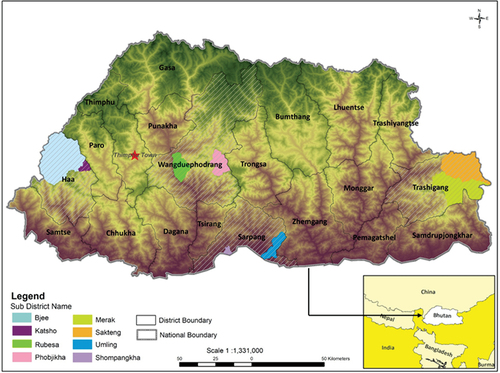

Bhutan (38 394 km2) is located in the eastern Himalayas, between China to the north and India to the east, west, and south (). Elevation ranges from 150 m along the southern border to >7570 m above sea level (m. asl) in the north, within a horizontal distance of 170 km (MoAF Citation2014). Due to the rugged mountainous terrain, agricultural farming occurs on only 2.75% of the total geographic land area (FRMD Citation2017), most of which is in the protected areas and government reserved forests (Tshewang et al. Citation2021) exposing subsistence farmers to wild predators. Bhutan’s agricultural sector is largely comprised of subsistence farmers (Choden et al. Citation2020) who produce ~50% of the country’s food requirement (Ngawang and Lalit Citation2018), and the remaining need being met through food imports. Agriculture sector employs ~60% of the total population and contributes 16% to the gross domestic product (GDP) (NSB Citation2020).

Figure 2. Map of Kingdom of Bhutan and map showing the location of the research sites (the four districts and the eight sub-districts) which represented different parts of the country. The colors purple to green represents an elevation gradient from 150 in the south to 7570 m. asl.

According to the PAR (Citation2017), poverty in Bhutan is a rural phenomenon with ~12% of the rural population being poor, of which 0.8% were classified as extremely poor. Of the total population (681,720) in 2017, 8.2% were poor living below the poverty line of Nu. 2 195.95 (US$30) per person per month (PAR Citation2017). Alleviating poverty is therefore important for achieving SD in Bhutan.

Gender and rural development in Bhutan

The socio-cultural norms about the roles and position of men and women in Bhutanese society are based on a traditional value system that has been practiced for generations. Unlike many neighboring countries, there is no prevailing caste system in Bhutan and every individual is equal under the law of the land. The equal status of women and the elimination of discrimination and violence that can exist against women and girls in Bhutan were ratified in the Constitution of Bhutan (2008). Despite women’s legal status, disparities still exist, especially in decision-making, labor force participation, caregiving, unpaid work, and tertiary education amongst others (Rinzin Citation2020). In 2017, Bhutan ranked 124 from among 144 nations on the Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) which was based on four indicators: political participation, health, education, and economic empowerment to assess gender parity (Schwab et al. Citation2017).

Poverty in Bhutan therefore can be accentuated by gender. Gender equality and empowerment of women and girls is legislated in Bhutan; however, most households headed by females are amongst the poorest in society. These households, in rural areas, have lower education levels and own fewer assets (e.g. livestock and land) (Aryal et al. Citation2019). For instance, Bhutan Living Standards Survey Report (2017) results showed a marked difference in literacy rate between male and female population. About 73% of the male population are literate as compared to 59% of the females. These characteristics lead to many female-headed households having a lower adaptive capacity to environmental change (Choden et al. Citation2020). Further, the outcomes of both 2010 and 2015 GNH Surveys showed men being happier than women, an indication of the existence of gender inequalities (Verma and Ura Citation2022).

Study area and livelihood sources

This study was conducted across four geographically distinct districts (Haa, Sarpang, Trashigang, and Wangdue Phodrang) of Bhutan (). To examine the impacts of wildlife in a diverse circumstance, within each district, two sub-districts were selected: one located inside a protected area and the other outside the protected area. Pastoralism has been and continues to be the primary source of livelihoods for people of Merak and Sakteng in Trashigang. These communities depend entirely on livestock and livestock products and collection of forest products for their livelihoods. Similarly, in Haa, pastoralism is the main livelihood source though it is also supplemented with crop cultivation. Livestock animals reared by the herders in Trashigang and Haa include Yak (Bos grunniens), cattle (B. taurus), sheep (Ovis aries), and horses (Equus caballus). The main livelihood sources of respondents in Sarpang and Wangdue Phodrang are based on crop farming supplemented with livestock rearing and collection of forest products.

Participant selection and data collection

Data for this study were obtained from interviews and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). We adopted a mixed method approach to provide an in-depth analysis with external validity (Creswell and Plano Clark Citation2007) with qualitative data complementing a primarily quantitative analysis and used to help explain and illustrate findings about HWC. Qualitative FGDs were conducted to gain a general understanding of HWC in selected sub-districts and guide participant sampling. Quantitative and qualitative data were generated with the use of semi-structured questionnaire with open and closed questions. In a semi-structured questionnaire, open and closed questions complement each other in deriving qualitative and quantitative responses. The survey was administered at a household level to 96 subsistence farmers spread across four districts (n = 24) in each district. The total number of households in the selected districts is Haa = 2790, Sarpang = 10135, Trashigang = 10435, and Wangdue Phodrang = 8337 (PHCB Citation2017).

The research participants were selected through stratified random sampling. Stratification was done based on wealth category and gender of the household head, as these are related to livelihoods and likely impacted by HWC. With the use of local criteria for wealth classification, the households were categorized into three wealth groups (WG): Rich, Average, and Poor. Local criteria for wealth classification included land and livestock holding size, estimated annual income, type and size of the house, number of household labour, and number of family members in government service. Wealth categorization was done to capture the variability in household livelihoods in the research sites. The total households within each wealth category were further stratified based on the gender of the household head. Then, from each sub-group, two male-headed and two female-headed households were selected randomly following a probability sampling technique (Etikan et al. Citation2016). Four households (two female-headed and two male-headed) from each wealth group totaling to 12 households in each sub-district and 24 households in each district. In total, 96 households took part in the semi-structured interview and each household as a unit of analysis. Then, in each selected household, the head of the household was interviewed. In the absence of the household head, a female in female-headed sample households and a male in male-headed sample households were interviewed.

All the 96 selected households were interviewed for the quantitative data, and half of them (i.e. 48) were interviewed further for qualitative data. These 48 households were selected randomly following a probability sampling technique. The quantitative interview lasted approximately 25–30 minutes, and the qualitative interview took about 45–60 minutes for each respondent and another 15–20 minutes for checking accuracy and completeness of the interviews. Research participants were asked the following key guiding questions: (1) whether they are experiencing HWC in their community or not, (2) why they think HWC is occurring, (3) how does HWC impact on farmer’s lives and livelihoods; (4) perceived crop and livestock losses and properties damaged; (5) HWC prevention measures adopted and their effectiveness; (6) perceived wildlife species conflicting with subsistence farmers; and (7) importance of wildlife conservation to farmers and reasons. In addition, socio-demographic information was gathered for all the respondents. The interview was carried out in the local language by the first author (a native Bhutanese language speaker) at each respondent’s residence. The semi-structured interview guide was pre-tested on 12 Bhutanese people of varying ages, sexes, and backgrounds living in Melbourne. This was done to determine if respondents understand the questions as well as to see if the questions elicit the required data to answer the research questions.

Prior to the individual household interviews, an FGD was carried out in each selected sub-district to contextualize HWC at sub-district level. FGD is a technique for gathering qualitative data in which participants can explore one another’s responses on a topic (Lederman Citation1990). The topics covered in FGDs triangulated and complemented the quantitative and qualitative interview questions. In total, eight FGDs were carried out, one in each selected sub-district with five to eight research participants. Participants who judged to have longer farming experiences and having good knowledge of HWC were purposively selected in consultation with the head of the sub-district. Farming experience was measured based on years in farming and duration of residency in the sub-district. In total 63 participants (30 women and 33 men) participated in the FGDs and in most cases each FGD lasted between 3 and 4 hours.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed parallelly using both quantitative and qualitative analytical techniques. The results were integrated in a coherent and meaningful way to yield a strong meta-inference where qualitative data complemented the quantitative data (Onwuegbuzie and Combs Citation2011).

Qualitative analysis

Both qualitative and FGD records were transcribed. Responses to questions about HWC and impacts were categorized into themes to help in locating representative narrative text for specific survey questions. The two data sets were interpreted in tandem, employing qualitative interview data to help explain quantitative results of the survey analysis and to provide more breadth and depth of the interlinked issues.

Quantitative analysis

The wealth ranking conducted at the sub-district level was context dependent. To account for any bias in relative wealth versus actual wealth, we used principal component analysis (PCA) and a non-hierarchical clustering method, K-means clustering, to identify groups of participants with similar socioeconomic characteristics. These groups could be expected to respond differently to HWC as socioeconomic status can be an important determinant of the magnitude of HWC on a person’s/family’s livelihood. R (version 4.0.5, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used to perform the PCA and SPSS Statistics (version 27) for the clustered analysis. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure was used to verify the sampling adequacy of the data, with a value of 0.5 used as a threshold for acceptability (Williams et al. Citation2017). The Bartlett test of sphericity was used to check if the data were suitable for use in a PCA. Once socioeconomic variables have been assembled into components via the PCA procedure, we used the cluster analysis to identify asset clusters. We labelled the clusters as cluster 1: high asset cluster, cluster 2: average asset cluster; and, cluster 3: low asset cluster. Differences of household size, land and livestock holding, and annual income between clusters were tested for significance using independent-sample t-tests.

A logistic regression analysis was used to investigate if there were relationships between the overall economic loss caused by wildlife and socio-demographic factors such as gender and asset clusters. The response variable that is the overall HWC economic loss caused by wildlife was tested a priori to verify that there was no violation of the assumption of the linearity of the logit. Since there were more than two levels in the asset cluster, we dummy coded the high asset cluster and average asset cluster with 0 and 1 and used the low asset cluster as a reference. This was conducted to understand how changes in the predictor variables are associated with the total HWC economic loss values. To test for difference in HWC economic losses in proportion to their annual income between the asset clusters, we performed One-Way ANOVA. Since the sample sizes in each asset cluster were different, we assumed that the variances were not equal and used Games-Howell and Welch tests (Qassemian et al. Citation2019).

Results

Identifying asset clusters

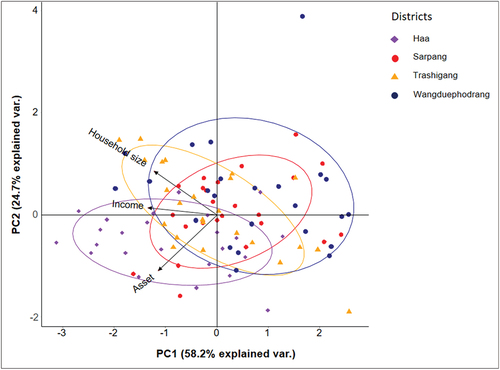

From the PCA analysis, two principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted that accounted for 83% of the total variance in the dataset (see ). An eigenvalue >1 indicated that the components had sufficient explanatory power to represent the information contained in the original variables (Zou and Yoshino Citation2017). Factor loadings for indicators with an absolute value greater than 0.3 were considered (de Campos et al. Citation2020). The value obtained from the sample adequacy measure of Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) was 0.616. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), indicating that our analysis was robust. The relationship between socioeconomic indicators as a function of PC1 and PC2 and the distribution of households from the study is illustrated in .

Figure 3. Scatterplot of household’s distribution along PC1(X axis) and PC2 (Y axis). Component one explained 58.2% of the variance in the dataset. Lesser household members, fewer asset and lower income (sum) characterized this component. The relationships among these three indicators suggest that households with fewer household members tend to have fewer assets and lower income. Component two explained 24.7% of the variance and was represented by household size and income. There were higher loadings on household size and income, indicating households that had larger household size and higher annual income but with fewer assets.

From the cluster analysis, a three-cluster solution was chosen, as it retained an adequate number of households in each cluster. The results showed that cluster one was centered on interviewees with more household members, larger land and livestock holdings, and higher annual income. The second cluster centered on interviewees that had an average number of household members, medium livestock and land holdings, and average annual income. The third cluster was characterized by interviewees with fewer household members, less livestock and land holdings, and lower income ().

Table 1. Socioeconomic characteristics of the three clusters and number of households in each cluster. Letter superscripts indicate significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) within clusters.

The proportion of interviewees from each district in each cluster is summarized in Supplementary figure A1a. Cluster 1 is dominated by respondents from Haa, Trashigang, and Sarpang. Cluster 2 members are mostly from Wangdue Phodrang and Sarpang. Cluster 3 is dominated by respondents from Wangdue Phodrang. By gender, cluster 3 is dominated by female-headed households (see Supplementary figure A1b). There were significant differences between clusters in all metrics (). The only non-significant difference detected was between the amount of land owned between households in the high asset and average asset clusters.

Exposure and sensitivity

All respondents (100%, n = 96) experienced wildlife impacts and suffered substantial economic losses through crop and/or livestock depredation and/or property destructions, and they perceived an increase in their exposure to such impacts. This suggests that some degree of vulnerability to wildlife impacts exists irrespective of geographic location, land tenure, and livelihood activity. However, respondents in asset cluster three suffered higher economic losses. The wealthier respondents in terms of large family size, high annual income, large land and livestock holdings were in a better position to absorb the impacts of the losses and protect their crops and livestock animals from wildlife damage. Of the total respondents, ~73% (n = 70) suffered crop losses and ~60% (n = 58) incurred economic losses through livestock depredation. Destruction of property was reported by 8.3% (n = 8) of interviewees and was restricted to the Sarpang district. Human casualties were not reported to have occurred to the respondents’ families; however, both human injury and deaths were reported to have occurred to others in Sarpang district. Elephant (Elephas maximus) was the species identified as causing both property destruction and human injuries and death.

Vulnerability to wildlife impacts and asset clusters

The absolute economic loss suffered by households in high asset cluster was significantly greater (p ≤ 0.01) than those households in average and low asset clusters (). There was no significant difference in the overall economic loss between average and low asset clusters. There was a significant negative association between asset cluster and total economic loss (rs = −0.32, p ≤ 0.002). The odds of a household suffering an overall HWC economic loss was 2.94 times greater for households in high asset cluster than for households in the low asset cluster (0.58, p = 0.118). The odds of a household in the average asset cluster suffering economic loss were 0.48 times greater than households in the low asset cluster; however, the odds ratio was only weakly significant (p = 0.06). In relation to relative income, the economic losses were significantly greater for the households in the low asset cluster compared to households in the high asset cluster (p ≤ 0.034) and average asset clusters (p ≤ 0.041). This is further supported by respondent (#23) who stated:

Last year my neighbours have fenced their vegetable fields with green net. It is very expensive, and I could not afford to purchase green net to protect my vegetables from rabbits and all my beans and chilli are eaten by rabbits. I could not sell any beans or chilli. It is just enough for our consumption. No good fence, no vegetables. Only those who can afford good fence can grow vegetables these days.

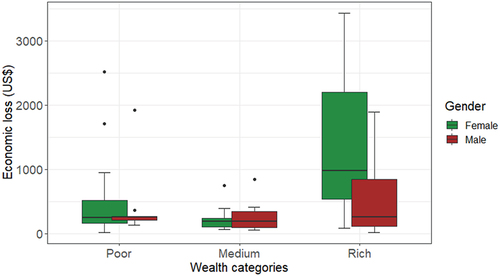

Vulnerability to wildlife impacts and gender

Of the total respondents, 41.7% (n = 40) were male and 58.3% (56) were female. The loss reported by female-headed households was significantly higher than the losses reported by male-headed households (n ≤ 0.02) (). The results of the regression analysis found that the odds of the loss being from a female-headed household increased by 2.14 times [(B) = 2.14, 95% CI (1.07, 4.27)] for every US$ increase in overall economic loss due to HWC. Female headed households therefore experienced a greater impact from HWC. They are activity burdened as they have to attend to added labor demands associated with HWC, in addition to their regular household chores and childcare role. Being the head of the family, they are also the primary earner and provider for the family.

Female-headed households can be the most vulnerable to food insecurity. Because of social norms and personal safety reasons not only from wildlife but also from humans, females do not perform night crop guarding, while most wildlife activities are nocturnal, and damages are high, compounding their vulnerability. One of the many reasons why women reported not doing night crop guarding is because of the practice of PchiruShelni, where ‘pchiru’ relates to night and ‘shelni’ implies to wander around, meaning men wandering at night in search of women, popularly known as ‘night hunting’. It is therefore important not only to describe but also to explain gender differences in HWC impacts and their prevention, as these gendered differences shape farmers’ attitudes and willingness to coexist with wildlife.

More importantly, our data revealed that even children in female-headed households and those in poor families are more vulnerable to HWC impacts in terms of their education. This vulnerability exists because female-headed households and poor families employ school-going children in day crop guarding and livestock herding to ease the added labour demand associated with HWC. As a result of crop loss to wildlife, while most children miss school attendance frequently, few are made to stop going to school altogether to earn and help feed the siblings by babysitting for office working families.

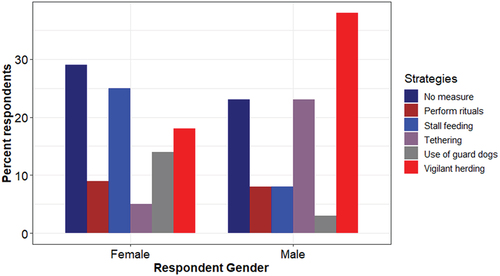

Adapting to HWC

Respondents reported to use a wide range of HWC adaptation measures, however they are largely represented by traditional and low-cost adaptation measures, which were less effective in reducing crop and livestock losses. Of the total respondents, 27% had adopted at least one measure, 26% implemented two types of measures, and 44% adopted 3 measures. There was no difference in the number of HWC adaptation measures adopted between asset clusters and gender, although the types of measures adopted differ. Guarding, use of barriers (e.g. wooden fence, stone wall, bamboo fence, and bush fence), use of deterrence (scare crow, beating empty tins, hanging pieces of cloth on fencing poles, using fire), clearing vegetation around fields, and leaving fields fallow were the commonly used HWC adaptation measures for crop protection. Where farmers practiced mixed cropping and were exposed to a diversity of wildlife species, they reported to use multiple techniques in combination. Some respondents adapted their cultivation and planted less palatable crops for wild animals such as cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) instead of rice (Oryza sativa) and maize (Zea mays) though both rice and maize are important staple foods of Bhutanese people.

Guarding was the most dominant preventive measure adopted by 59.4% of respondents. Of this, 52.6% were from high asset cluster, 17.5% from average asset cluster, and 29.8% from the low asset cluster. Crop guarding as a HWC adaptation measure is therefore more common among high asset cluster. Crop guarding was a 24-hour activity where farmers need to guard crops both day and night. Most tend to use day crop guarding as night crop guarding requires farmer to endure indescribable hardships as they need to spend sleepless nights out in the field watching over their crops. Among the households in high asset cluster, crop guarding was mostly carried out by men; however, in the low asset cluster, guarding was the responsibility of every household member including school going children (see Supplementary figure A2a). There was a significant difference in the amount of guarding between male and female-headed households (p < 0.001) with ~61.4% of male-headed households and 39% female-headed households utilizing guarding. Female-headed households mostly tend to use day guarding, although most wild animal activity was reported as being nocturnal (see Supplementary figure A2d).

Electric fence (EF) was perceived as the second most effective HWC adaptation measure. Approximately 40% of the total respondents reported to have installed EF to protect their crops from wildlife damage. There were no differences in number of male- and female-headed households that installed EF. Amongst asset clusters, the percentage of respondents that reported to have installed EF were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.002), with 58% of respondents in high asset cluster having installed EF compared to 29% in average asset cluster and 13% in the low asset cluster. Most respondents (84.2%) reported that EF was an effective preventive measure which was consistent with our regression analysis which found that the odds of the loss for households without EF increased by 0.283 (95% CI (0.105–0.765), p ≤ 0.013) for every US$ increase in HWC economic loss.

Livestock protection measures included vigilant herding, stall-feeding, use of guard dogs, performing rituals, and tethering in pastures (). There was no difference in the type of measures adopted amongst asset clusters, although households in higher asset cluster reported to perform more rituals. Among gender, most of the male-headed households practiced vigilant herding, while stall feeding and the use of guard dogs were common among female-headed households. As with night crop guarding, yak herding was considered as a physically demanding activity which only few females do; most female-headed households reported to either freely graze their yaks or place them with other herders, thus increasing predation losses.

HWC impacts interact with existing vulnerabilities and affects quality of life

Subsistence farmers reported facing a myriad of socio-economic challenges associated with HWC. In the following section, we present some insights into the ways in which respondents experienced HWC impacts on their lives and livelihoods. Food insecurity and added labour demand were narrated as the most prominent challenge associated with HWC, in both qualitative interviews and FGDs. Some respondents, with their livelihoods at stake, are more vulnerable to wildlife impacts. For instance, yaks are fundamental to the survival of yak herders as they depend entirely on yaks for food, clothing, housing (their tents are made of yak hair) and earning cash (see Supplementary figure A3). Losing a yak to wildlife affects every aspect of herder’s life and livelihoods. Additionally, the inaccessible locations and marginal existence make these herders’ livelihoods difficult to diversify, making them more vulnerable to shocks and livelihood insecurity, thereby increasing their hostility toward wildlife. For instance, respondent (#7) stated:

We should be allowed to control Asiatic wild dog population. There is no peace in our life with these animals around like today. This park turned our pasture to forest and our yaks to food of these animals. I wish some miracles happen to wipe out these animals (wild dogs).

Further, the added labour demand has forced many subsistence farmers to abandon distant fields due to their inability to protect crops from wildlife damage. About 3.1% of the total land holding (116 Ha) of the interviewees spread over 3 districts were left fallow due to unbearable losses caused by wildlife. These abandoned fields are owned by ~12% of the respondents and most are female headed households. On the other hand, most pastoralists have stopped sheep farming, while few others indicated a desire to give up yak herding. While a lack of pasture and decline in pasture quality and production are contributing factors encouraging pastoralists to discontinue sheep and yak farming, increasing predation and shortage of labour to look after sheep were the main reasons reported. Sheep require vigilant herding as they are easy to kill by any wildlife species. Respondent (#3) stated:

Sheep is very easy to kill. Even dogs can kill sheep. Someone must look after them vigilantly and we cannot afford to do that, and I lost most of our sheep to wildlife.

Similar stories narrated by respondent (#1), ‘Sheep farming is disappearing now. Many farmers have lost sheep to wild animals. Yak herding may follow this trend in future’. Sheep is an important livestock species primarily kept for wool which is used for making dress and blanket. The disappearance of sheep farming led most interviewees in Merak and Sakteng to worry about the disappearance of their traditional costume, especially that of men’s attire, which is made entirely from sheep’s wool.

HWC causes a chain of impacts on the lives and livelihoods of subsistence farmers. Rural urban migration is one such impact. Some subsistence farmers resorted to migrate to urban centers in search of alternative livelihood sources. As abled farm labors emigrate, most rural homes are faced with labor shortages resulting in abandonment of fields and feminization of agricultural farming, further contributing to HWC losses. For instance, respondent (#39) narrated:

It is discouraging to do farming these days. We can hardly harvest any crop without wildlife damage. These days animals eat everything that we grow. Whatever is left is not even enough to compensate for what we have paid for the hire labors. People migrate to urban centers because of this. Many rural homes are left to age-old parents.

The connection between HWC and SDGs

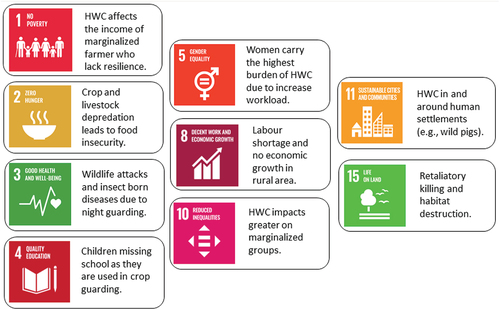

Sustainable development in landscapes where human and wildlife cooccur frequently can be challenging. Our results showed that HWC has a considerable negative impact on most of the SDGs ().

Figure 6. Illustration of how HWC hinders the achievement of sustainable development goals in subsistence livelihood context in landscapes impacted by HWC.

As described above, economic loss incurred through crop and livestock depredation compounds marginalisation and vulnerability of subsistence farmers, thereby impairing achievement of SDGs 1 and 2. The disproportionate distribution of wildlife impacts between individuals and within socioeconomic groups can inhibit attainment of SDGs 5 and 10. Employment of schooling children for crop guarding and livestock herding can impede accomplishment of SDG 4. The negative health implications arising from insect-borne disease (e.g. malaria from mosquito bite) and injury cause by wildlife attack during night crop guarding can hinder achievement of SDG 3. Due to sleepless nights, many farmers spoke of feeling of drowsiness and tiredness during the following day, negatively impacting the work performance. HWC induced abandonment of farms even when farmers are not able to produce enough food and rural out migration can impair realization of SDG 8. As most distant fields are being left fallow, most respondents reported wildlife (e.g. wild pig, elephant) coming closer to human settlement, causing damages to kitchen gardens, fruit orchards, houses, cow sheds, and water tanks in addition to foraging on crops. Poor families dwelling in huts spoke of risks from marauding elephants, especially at night. Respondent (#16) stated:

My family live in a very old hut and it is not safe. Elephants can destroy it easily. Often at night when elephant come to eat banana or sugarcane nearby our home, we have to grab our children and run to neighbor’s place. It is scary as sun goes down, they frequently come for banana.

This can impede the achievement of SGD 11. On the other hand, high economic loss caused by wildlife has negatively influenced farmer’s attitude towards wildlife. For example, because of the high economic loss caused by Asiatic wild dog (Cuon alpinus) through depredation of yaks, currently there is a very low Asiatic wild dog tolerance amongst yak herders. As such negative attitudes come to dominate, it may lead to increase dissonance and a general lack of compassion towards wildlife, translating into retaliation. This could inhibit achievement of SDG 15. These findings demonstrate that HWC is an issue for social and economic development as much as it is for biodiversity conservation. This means that if SDGs are to be achieved in subsistence livelihood context, HWC must be adequately understood and effectively mitigated. More importantly, HWC should be included in SDG implementation plans as well as the Convention on Biodiversity.

Discussion

The SDGs are aimed at providing an inclusive framework for ending poverty worldwide by 2030. However, HWC may inhibit the successful achievement of several SDGs in Bhutan and in regions impacted by negative human wildlife interactions.

Exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity to HWC in achieving SDGs

In Bhutan, both agricultural farming and livestock husbandry are critical for achieving food security and economic growth. However, the occurrence of HWC has made it difficult to achieve both food security and economic growth. The results of this study showed that all (100%, n = 96) respondents reported being impacted by wildlife mainly through crop and livestock depredation and/or destruction of properties. On an average, a household lost ~65% of their annual income to wildlife damage, which is very high in a subsistence livelihood context with per capita income of US$ 3129.86 (NSB Citation2020). These losses may not seem significant at the national level; however, in subsistence livelihood context, it is a high cost as most of these affected households are amongst the least privileged people in the world. These losses significantly undermine household food security, thereby impairing achievement of SDG 1 and 2. Depredation of crop and livestock is the most common form of HWC in most parts of the world (Nyhus Citation2016) with substantial economic losses to subsistence farmers who pursue their livelihoods in a context of high and endangered biodiversity (Seoraj-Pillai and Pillay Citation2016). These losses generally result in increasing income and food insecurity (Salerno et al. Citation2016; Gemeda and Meles Citation2018) particularly to those living in poverty and lacking adaptive capacity (Gross et al. Citation2021).

We found that wildlife impacts are not uniformly distributed across different socio-economic groups and between individuals, with some individuals and groups shown to be more vulnerable than others. As Reed et al. (Citation2014) stated, the difference in intensity of impacts of natural disasters on people is a function of their gender and wealth. Our results showed that female-headed households and those families in the low asset cluster experienced a disproportionate burden of HWC. The higher relative economic loss suffered by these households highlights a greater vulnerability to achieving SDG 1, 2, 5 and 10 in subsistence livelihood context. These results are in congruent with the findings of others (see Dickman Citation2010; Khumalo and Yung Citation2015; Doubleday and Adams Citation2020). Female-headed households and those families in the low asset cluster lack both financial and human resources, while economic well-being is identified as a social resilience and risk reducing factor (Daramola et al. Citation2016). Reducing poverty will reduce food insecurity, however this may be made more difficult as HWC reinforces income inequalities (Dickman Citation2010; Doubleday and Adams Citation2020).

Wealth helps subsistence farmers to minimize impacts of HWC by having access to adequate financial and human resources. For example, we found that larger land and livestock holdings were characteristic of households in the high asset cluster, which resulted in higher absolute economic losses; however, this was not reflected in increased vulnerability as they were able to reduce wildlife-induced losses through applying the best preventive measures and exhibited a higher adaptive capacity. EF, for example, was more common among households in high asset cluster as high initial labor investment for installation and their sustained maintenance disadvantage the uptake of EF by female-headed households and those in low asset cluster. Further, female-headed households do not use night crop guarding due to various reasons. Adaptive capacity is associated with the ability to take proactive measures in anticipation of a disaster event (Fernández-Giménez et al. Citation2015) which is beyond the capacity of female-headed households and those families in low asset cluster. Wealth and gender perspectives are therefore important in understanding not only the differential impacts of HWC but also the divergent responses to HWC created by inequalities (Khumalo and Yung Citation2015; Doubleday and Adams Citation2020). Wealth enables higher adaptive capacity thereby lessening vulnerability to wildlife impacts (Dickman Citation2010; Margulies and Karanth Citation2018; Doubleday and Adams Citation2020). As with climate change, where the poor are hit the hardest (Angus Citation2017), such is the case with HWC where the poorer sections of society are typically the ones most impacted (Barua et al. Citation2013; Khumalo and Yung Citation2015).

The uneven distribution of wildlife impacts, both locally and globally (Kansky and Knight Citation0000; Barua et al. Citation2013), impedes achievement of several SDGs. For instance, the use of school-going children for crop guarding and livestock herding by female-headed households and those families in low asset cluster hinders the achievement of SDG 4. Such practice can create lifelong inequalities in education, reduce human capital building and may increase the likelihood of transferring poverty to the next generation among these families. Our results are in congruent with the findings of Mackenzie and Ahabyona (Citation2012) in Uganda; Mwangi et al. (Citation2016) in Kenya and Ango et al. (Citation2017) in Ethiopia who found children from villages impacted by HWC tended to have poorer scholastic achievement due to their engagement in crop guarding and livestock herding. While day crop guarding impairs children’s education, the night crop guarding can have negative health implications. Farmers are exposed to insect-borne diseases such as malaria from mosquito bites in addition to the risks of being bitten by poisonous snakes or attack by wildlife. This can impair the ability for SDG 3 to be achieved in subsistence livelihood context. This mirrors the concerns reported by Ogra (Citation2008) in Uttaranchal, India, Khumalo and Yung (Citation2015) in Namibia, and Muyoma (Citation2016) in Zambia.

An unexpected result was that when they are already experiencing food scarcity, most female-headed households and those families in low asset cluster resorted to abandoning fields located far from settlement due to wildlife damages. This may have unforeseen ripple effects on achievement of several SDGs and overall economic development in rural Bhutan. Keeping farmland fallow reduces food production and thus local food security (Tong et al. Citation2016). Farmland abandonment caused by HWC has also been reported in China (Hua et al. Citation2016). Faced with similar human and financial resource constraints, many herders stopped sheep farming. Sadly, the unavailability of occupational work and lack of access to financial capital prevents many of these herders from diversifying their livelihoods. Irrespective of livelihood activity, this locks households in low asset cluster and female-headed into a circle of poverty, thus impairing the ability for SDG 8 to be achieved in rural Bhutan. Farmers/herders with more diverse livelihoods have a higher adaptive capacity in Bhutan (Choden et al. Citation2020).

With more distant fields being abandoned, frequent occurrence of wildlife damage within human settlements was reported. This could be the result of increasing wildlife populations because of current conservation policies (NCD Citation2008; Karst and Nepal Citation2019) and Buddhist beliefs of non-violence and compassion towards animals (Rinzin et al. Citation2009). In other regions, habitat loss and fragmentation has forced wildlife into human dominated landscapes, which leads to HWC at the urban interface (Bhatia et al. Citation2013; Billah et al. Citation2021). This can potentially impede the achievement of SDG 11. In Bhutan, Rinzin et al. (Citation2009) showed that ~3% of rural–urban migration is attributed to HWC which is consistent with our findings. Sadly, rural out migration has resulted in weakening of social cohesion, and old age destitution. Many elder farmers who were orphaned by rural out migration spoke of feeling a sense of loss of connections and support within their community and expressed concerns about bleak future not being far for their communities.

We found that the respondents that lacked resources for diversifying their livelihoods were less willing to coexist with wildlife. For example, the herders of Merak and Sakteng who depend entirely on yak and yak products for food and income are more antagonistic towards wildlife. The inaccessibility of where they live and the lack of alternative livelihood options made these herders’ livelihood more vulnerable. Consequently, there is currently a very low tolerance for Asiatic wild dogs, and an increased likelihood of retaliation, which can impair the ability for SDG 15 to be achieved in Bhutan. Similar intolerance resulted in farmers exterminating Asiatic wild dog populations in many parts of Bhutan during the 1980s (Thinley and Lassoie Citation2013). Generally, perceived or real, threats to livestock have been the main driving force behind retaliatory killing of large carnivores (McNutt et al. Citation2017; Gebresenbet et al. Citation2018; Bhattarai et al. Citation2019). The survival of apex predators depends on successful HWC management (Inskip and Zimmermann Citation2009) that improves food security, alleviates poverty, and promotes a sustainable balance between society and nature. HWC epitomizes a double-edged sword, imparting harm to both people and wildlife alike.

In Bhutan, compensation has been paid for livestock killed by tigers (Panthera tigris), snow leopards (Panthera uncia), leopards (Panthera pardus), and Himalayan black bears (Ursus thibetanus) (MoAF Citation2016). No compensation is paid for crops that are damaged and livestock killed by other wildlife species (Rinzin et al. Citation2009). Lack of compensation to crop damages forced farmers to use fatal techniques against wildlife, often leading to killing of wildlife in some African countries (Yaw and Silvia Citation2019). Policy actions may need to consider extension of compensations to economic losses caused through crop depredation by wildlife and investment in targeted protection measures such as deterrents and barriers to prevent damage, and awareness campaigns to increase people’s tolerance towards wildlife. Although there are mixed messages about the effectiveness of compensation as a tool for mitigation of HWC, it is a widely used program in many parts of the world (Ravenelle and Nyhus Citation2017). To improve the effectiveness and efficacy of compensation schemes, the most common recommendation was making payment conditional on adaptation of HWC preventive activities (Boitani et al. Citation2010; Yaw and Silvia Citation2019), an approach widely practiced in Europe (Marino et al. Citation2016).

In Bhutan, past HWC prevention and adaptation policy actions have not factored in the indirect impacts of HWC on the psychological well-being of wildlife impacted farmers (Yeshey et al. Citation2022) and the differentiated impacts of HWC. Small family size, lack of male members, and low income are major constraints in adoption of available or existing adaptation strategies (e.g. electric fence or vigilant livestock herding). In parts of India, studies have shown that poor farmers were unable to invest in HWC mitigation measures and were less likely to use HWC prevention and mitigation (Karanth and Kudalkar Citation2017). To be effective, future policy formulation must pay special attention to these constraints and also take into account not only the direct costs and/or material loss (amount of crop and number of livestock loss) caused by wildlife but also the indirect impacts of HWC on the psychological well-being of the HWC affected farmers. Subsistence farmers are impacted by wildlife not only economically and physically but also psychologically (Yeshey et al. Citation2022), and such impacts often spark retaliatory action (Barua et al. Citation2013; Frank and Glikman Citation2019). Identifying vulnerable households supported by deploying effective adaptation strategies will build tolerance where it is most needed.

Ecotourism and homestay programs have brought economic benefits to local communities and encouraged wildlife guardianship behaviour in communities in parts of India (Bhalla et al. Citation2016; Maheshwari and Sathyakumar Citation2019). However, as Van Eeden et al. (Citation2018) state that strategies to manage HWC must be context-specific, the success of any HWC adaptation measures is influenced by social, economic, cultural, ecological, demographic, and political factors, as has been seen in this research. The ability to develop any HWC adaptation measures relies therefore heavily on understanding the conflict scenario (Dickman Citation2010; Redpath et al. Citation2015). Contextualizing HWC to provide a concise view of the conflict pattern will help decision makers to prioritize areas and concentrate HWC prevention towards individual and communities that require immediate attention.

Conclusions

HWC is widespread, and subsistence farmers are experiencing increasing negative interactions with wildlife with substantial economic losses. Impacts of the losses are disproportionally distributed between individuals and within socioeconomic groups. Gender and wealth are important determinants of HWC impacts, shaping the ability to absorb the impacts of the losses and adopt HWC adaptation measures to maintain food and income security. Households with high asset holdings can afford and implement the most effective measures for reducing HWC impacts, while households with low asset holdings cannot, exacerbating the impacts of HWC over time. Households with low asset holdings have a lower adaptive capacity thereby increasing their overall vulnerability, their exposure to wildlife impacts, and thus their food insecurity.

Importantly, our findings highlight that the influence of HWC is multidimensional and highly likely to impair the achievement of several SDGs in landscapes impacted by HWC. Dealing with HWC-induced challenges requires an in-depth understanding of gender and wealth dimensions of HWC. Without government intervention, HWC will continue to intensify and change the livelihoods of rural communities through increased rural–urban migration which in turn may exacerbate social and economic sustainability in rural Bhutan. Management strategies should focus on increasing the ability of female-headed households and those with low asset holdings to prevent and cope with negative wildlife interactions. Such management actions should help alleviate poverty, facilitate greater equity through empowering women to attain economic equality, and allow children to aspire to the highest education they deem fit. Breaking the poverty cycle created by HWC in Bhutan will help the country achieve a higher GNH while achieving the SDGs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (911.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Melbourne Research Scholarship program granted by the University of Melbourne for providing funding support to the first author. We are grateful to all the participants involved in the household survey. Our heartfelt gratitude to the Renewable Natural Resource staff of the four districts and eight sub-districts for facilitating the field work. We are also grateful to our reviewers for their insightful suggestions and comments.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2023.2167242.

References

- Adger WN. 2006. Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change. 16(3):268–281. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.006.

- Agarwal B 2018. Gender equality, food security and the sustainable development goals. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 34: 26–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.07.002

- Anderson CC, Denich M, Warchold A, Kropp JP, Pradhan P. 2021. A systems model of SDG target influence on the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Sustainability Sci. 17:1–14. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-01040-8.

- Ango T, Börjeson L, Senbeta F. 2017. Crop raiding by wild mammals in Ethiopia: impacts on the livelihoods of smallholders in an agriculture–forest mosaic landscape. Oryx. 51(3):527–537. doi:10.1017/S0030605316000028.

- Angus I. 2017. Heatwaves hit poor nations hardest. Green Left Weekly. (1131):13. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.733839383792884

- Aryal JP, Mottaleb KA, Rahut DB. 2019. Untangling gender differentiated food security gaps in Bhutan: an application of exogenous switching treatment regression. Rev Dev Econ. 232:782–802. doi:10.1111/rode.12566.

- Baca M, Läderach P, Haggar J, Schroth G, Ovalle O. 2014. An integrated framework for assessing vulnerability to climate change and developing adaptation strategies for coffee growing families in mesoamerica. PLoS one. 9(2):e88463. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088463.

- Barua M, Bhagwat SA, Jadhav S. 2013. The hidden dimensions of human–wildlife conflict: health impacts, opportunity and transaction costs. Biol Conserv. 157:309–316. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.014.

- Bennet NJ, Blythe J, Tyler S, Ban NC. 2019. Communities and change in the anthropocene: understanding social-ecological vulnerability and planning adaptations to multiple interacting exposures. Regional environmental change, 16(4):907–926. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0839-5

- Bhalla P, Coghlan A, Bhattacharya P. 2016. Homestays’ contribution to community-based ecotourism in the Himalayan region of India. Tour Recreat Res. 41(2):213–228. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2016.1178474.

- Bhatia S, Athreya V, Grenyer R, Macdonald DW. 2013. Understanding the role of representations of human-leopard conflict in Mumbai through media-content analysis. Conserv Biol. 27(3):588–594. doi:10.1111/cobi.12037.

- Bhattarai BR, Wright W, Morgan D, Cook S, Baral HS. 2019. Managing human-tiger conflict: lessons from Bardia and Chitwan National Parks, Nepal. Eur J Wildl Res. 65(3):1–12. doi:10.1007/s10344-019-1270-x.

- Billah MM, Rahman M, Abedin J, Akter H. 2021. Land cover change and its impact on human–elephant conflict: a case from Fashiakhali forest reserve in Bangladesh. SN Appl Sci. 3(6):1–17. doi:10.1007/s42452-021-04625-1.

- Boitani L, Ciucci P, Raganella-Pelliccioni E. 2010. Ex-post compensation payments for wolf predation on livestock in Italy: a tool for conservation? Wildl Res. 37.722–730. doi:10.1071/WR10029.

- Brooks JS. 2013. Avoiding the limits to growth: gross National Happiness in Bhutan as a model for sustainable development. Sustainability. 5(9):3640–3664. doi:10.3390/su5093640.

- Chambers R, Conway G. 1992. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. (UK): Institute of development studies.

- Choden K, Keenan RJ, Nitschke CR. 2020. An approach for assessing adaptive capacity to climate change in resource dependent communities in the nikachu watershed, Bhutan. Ecol Indic. 114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106293

- Chowdhury AN, Brahma A, Mondal R, Biswas MK. 2016. Stigma of tiger attack. Study of tiger-widows from Sundarban Delta, India. Indian J Psychiatry. 58(1):12. http://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.174355

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. 2007. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. los angeles: Sage publications inc.

- Daramola AY, Oni OT, Ogundele O, Adesanya A. 2016. Adaptive capacity and coping response strategies to natural disasters: a study in nigeria. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 15:132–147. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.01.007.

- de Campos CI, Pitombo CS, Delhomme P, Quintanilha JA. 2020. Comparative analysis of data reduction techniques for questionnaire validation using self-reported driver behaviors. J Safety Res. 73:133–142. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2020.02.004.

- Dickman AJ. 2010. Complexities of conflict: the importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human-wildlife conflict. null. 135:458–466. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00368.x.

- Digun-Aweto O, Van Der Merwe P. 2020. Coping strategies for human–wildlife conflicts: a case study of adjacent communities to Nigeria’s Cross River National Park. J Int Wildl Law Policy. 23(2):109–126. doi:10.1080/13880292.2020.1808391.

- DoFPS. 2016. State of the parks. Department of forests and park services. Thimphu, Bhutan: Ministry of Aagriculture and Forests.

- Doubleday KF, Adams PC. 2020. Women’s risk and well-being at the intersection of dowry, patriarchy, and conservation: the gendering of human–wildlife conflict. Environ Plan E Nat Space. 3(4):976–998. doi:10.1177/2514848619875664.

- Enarson E, Morrow BH. 1998. Why gender? Why women? An introduction to women and disaster. In:Enarson E, Morrow BH editors. The Gendered Terrain of Disaster. Westpost, CT: Praeger; pp. 1–8.

- Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS. 2016. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics. 5(10):1–4. http://doi.org/10.11648/j/ajtas.20160501.11

- Fernández-Giménez ME, Batkhishig B, Batbuyan B, Ulambayar T 2015. Lessons from the dzud: community-based rangeland management increases the adaptive capacity of Mongolian herders to winter disasters. World Development, 68: 48–65.doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.11.015

- Frank B, Glikman JA. 2019. Human-wildlife conflicts and the need to include coexistence. In:Frank B, Glikman JA, Marchini S, editors. Hum-Wildl Interact: Turning Conflict into Coexistence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; pp. 1–19.

- FRMD. 2017. Land use and land cover of Bhutan 2016, maps and statistics. Thimphu, Bhutan: Royal Government of Bhutan.

- FRMD. 2020. Forest facts and figures-2019. Forest resource management division. Thimphu, bhutan: Department of Forest and Park Services.

- Gebresenbet F, Bauer H, Vadjunec JM, Papeş M 2018. Beyond the numbers: human attitudes and conflict with lions (Panthera leo) in and around Gambella National Park, Ethiopia. PLoS One, 139: 1–17.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204320

- Gemeda DO, Meles SK. 2018. Impacts of human-wildlife conflict in developing countries. J Appl SCI Environ Manag. 22(8):1233–1238. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jasem.

- Gore ML, Kahler JS. 2012. Gendered risk perceptions associated with human-wildlife conflict: implications for participatory conservation. PLoS one. 7(3):e32901. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032901.

- Gross E, Jayasinghe N, Brooks A, Polet G, Wadhwa R, Hilderink-Koopmans F. 2021. A future for All: the need for human-wildlife coexistence. Vol. 3. Gland, Switzerland: WWF.

- Hua X, Yan J, Li H, He W, Li X. 2016. Wildlife damage and cultivated land abandonment: findings from the mountainous areas of Chongqing, China. Crop Prot. 84:141–149. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2016.03.005.

- Inskip C, Zimmermann A 2009. Human-felid conflict: a review of patterns and priorities worldwide. Oryx, 431: 18–34.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S003060530899030X

- Jamtsho Y, Katel O. 2019. Livestock depredation by snow leopard and Tibetan wolf: implications for herders’ livelihoods in Wangchuck Centennial National Park, Bhutan. Pastoralism. 9(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s13570-018-0136-2.

- Kansky R, Knight AT 201. Key factors driving attitudes towards large mammals in conflict with humans. Biological Conservation, 179: 93–105.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.008

- Karanth KK, Kudalkar S. 2017. History, location, and species matter: insights for human–wildlife conflict mitigation from India. Hum Dimens Wildl. 22(4):331–346. doi:10.1080/10871209.2017.1334106.

- Karst HE, Nepal SK. 2019. Conservation, development and stakeholder relations in Bhutanese protected area management. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol. 26(4):290–301. doi:10.1080/13504509.2019.1580628.

- Katel ON, Pradhan S, Schmidt-Vogt D. 2014. A survey of livestock losses caused by Asiatic wild dogs, leopards and tigers, and of the impact of predation on the livelihood of farmers in Bhutan. Wildl Res. 41(4):300–310. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/WR14013.

- Khumalo KE, Yung LA. 2015. Women, human-wildlife conflict, and CBNRM: hidden impacts and Vulnerabilities in Kwandu Conservancy, Namibia. Conserv Soc. 13(3):232–243. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26393202.

- Killion AK, Ramirez JM, Carter NH. 2021. Human adaptation strategies are key to cobenefits in human–wildlife systems. Conserv Lett. 14(2):e12769. doi:10.1111/conl.12769.

- Le Blanc D 2015. Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Sustainable Development. 233: 176–187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/sd.1582

- Lederman LC. 1990. Assessing educational effectiveness: The focus group interview as a technique for data collection. Communication edication. 39(2):117–127.

- Mackenzie AC, Ahabyona P 2012. Elephants in the garden: financial and social costs of crop raiding. Ecological Economics. 75:72–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.12.018

- Madden F. 2004. Creating coexistence between humans and wildlife: global perspectives on local efforts to address human–wildlife conflict. Hum Dimens Wildl. 9(4):247–257. doi:10.1080/10871200490505675.

- Maheshwari A, Sathyakumar S. 2019. Snow leopard stewardship in mitigating human–wildlife conflict in Hemis National Park, Ladakh, India. Hum Dimens Wildl. 24(4):395–399. doi:10.1080/10871209.2019.1610815.

- Margulies JD, Karanth KK 2018. The production of human-wildlife conflict: a political animal geography of encounter. Geoforum, 95: 153–164.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.06.011

- Marino A, Braschi C, Ricci S, Salvatori V, Ciucci P. 2016. Ex post and insurance-based compensation fail to increase tolerance for wolves in semi-agricultural landscapes of central Italy. Eur J Wildl Res. 62:227–240. doi:10.1007/s10344-016-1001-5.

- Martin N, Rice J. 2014. Sustainable development pathways: determining socially constructed visions for cities. Sustain Dev. 22(6):391–403. doi:10.1002/sd.1565.

- McNutt JW, Stein AB, McNutt LB, Jordan NR. 2017. Living on the edge: characteristics of human–wildlife conflict in a traditional livestock community in Botswana. Wildl Res. 44(7):546–557. doi:10.1071/WR16160.

- Mmbaga NE, Munishi LK, Treydte AC. 2017. Balancing African elephant conservation with human well-being in rombo area, Tanzania. Adv Ecol. 2017:1–9. doi:10.1155/2017/4184261.

- MoAF. 2014. Biodiversity action plan for Bhutan. Thimphu: Ministry of Agriculture and Forests.

- MoAF. 2016. Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. The endowment fund for crop and livestock conservation in Bhutan.

- Muyoma PJ 2016. The hidden costs of Human-Wildlife conflict in Mukungule Game Management Area, Mpika District, Zambia (Doctoral dissertation, University of Zambia).

- Mwangi DK, Akinyi M, Maloba F, Ngotho M, Kagira J, Ndeereh D, Kivai S 2016. Socioeconomic and health implications of human-wildlife interactions in Nthongoni, Eastern Kenya. African Journal of Wildlife Research, 462: 87–102.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3957/056.046.0087

- NCD. 2008. Bhutan national human wildlife conflict management strategy, nature conservation division. Thimphu, Bhutan: Department of Forests, Ministry of Agriculture.

- Ngawang C, Lalit K 2018. Climate change and potential impacts on agriculture in Bhutan: a discussion of pertinent issues. Agriculture & Food Security, 71: 1–13.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0229-6

- NPPC and WWF-Bhutan. 2016. Human wildlife conflict strategy: Nine Gewogs of Bhutan. Thimphu, Bhutan and WWF Bhutan, Thimphu: National Plant Protection centre (NPPC).

- NSB. 2020. Bhutan statistical yearbook 2020. National Statistics Bureau, Royal Government of Bhutan; https://www.Nsb.Gov.Bt/publications/statistical-yearbook/.

- Nyhus PJ. 2016. Human–wildlife conflict and coexistence. Annual review of environment and resources. 41.143–171. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085634.

- Nyirenda VR, Nkhata BA, Tembo O, Siamundele S. 2018. Elephant crop damage: subsistence farmers’ social vulnerability, livelihood sustainability and elephant conservation. Sustainability. 10(10):3572. doi:10.3390/su10103572.

- Ogra MV. 2008. Human-wildlife conflict and gender in the protected area borderlands: a case study of costs, perceptions, and vulnerability from Uttarakhand (Uttaranchal), India. Geoforum. 39(3):1408–1422.

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Combs JP. 2011. Data analysis in mixed research: a primer. Int J Educ. 3(1):E13. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11875/2950.

- PAR. 2017. Bhutan poverty analysis report, national statistics bureau, royal government of Bhutan, Post box no 338, Thimphu, Bhutan.

- Pezzey J. 1992. Sustainable development concepts : an economic analysis. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Population and Housing Census of Bhutan. 2017. National Report. National Statistics Bureau of Bhutan.

- Qassemian A, Koushkie Jahromi M, Salesi M, Namavar Jahromi B 2019. Swimming modifies the effect of noise stress on the hpg axis of male rats. Hormones: International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 184: 417.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s42000-019-00129-1

- Ravenelle J, Nyhus PJ. 2017. Global patterns and trends in human–wildlife conflict compensation. Conserv Biol. 31(6):1247–1256. doi:10.1111/cobi.12948.

- Redpath SM, Bhatia S, Young J. 2015. Tilting at wildlife: reconsidering human–wildlife conflict. Oryx. 49(2):222–225. doi:10.1017/S0030605314000799.

- Reed MG, Scott A, Natcher D, Johnston M. 2014. Linking gender, climate change, adaptive capacity, and forest-based communities in Canada. Can J for Res. 44(9):995–1004. doi:10.1139/cjfr-2014-0174.

- Rinzin P. 2020. Bridging gender gap in Bhutan: cSOs’ response to gender disparity. In: Momen Md N Baikady R, Li CS, Basavaraj M, editors. Building Sustainable Communities. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan; pp. 701–716.

- Rinzin C, Vermeulen WJV, Wassen MJ, Glasbergen P. 2009. Nature conservation and human well-being in Bhutan: an assessment of local community perceptions. J Environ Dev. 18(2):177–202. doi:10.1177/1070496509334294.

- Salerno J, Borgerhoff Mulder M, Grote MN, Ghiselli M, Packer C 2016. Household livelihoods and conflict with wildlife in community-based conservation areas across Northern Tanzania. Oryx, 504: 702–712.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0030605315000393

- Sangay T, Vernes K. 2008. Human–wildlife conflict in the Kingdom of Bhutan: patterns of livestock predation by large mammalian carnivores. Biol Conserv. 141(5):1272–1282. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.02.027.

- Schwab K, Samans R, Zahidi S, Leopold TA, Ratcheva V, Hausmann R, Tyson LD 2017. The global gender gap report 2017. World Economic Forum.

- Seoraj-Pillai N, Pillay N 2016 A meta-analysis of human–wildlife conflict: south African and global perspectives. Sustainability. 9(1):34. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su9010034

- Shah KU, Dulal HB, Johnson C, Baptiste A. 2013. Understanding livelihood vulnerability to climate change: applying the livelihood vulnerability index in Trinidad and Tobago. Geoforum. 47:125–137. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.04.004.

- Stafford-Smith M, Griggs D, Gaffney O, Ullah F, Reyers B, Kanie N, Stigson B, Shrivastava P, Leach M, O’Connel D. 2017. Integration: the key to implementing the sustainable development goals. Sustainability science. 126:911–919. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0383-3

- Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockstrom J, Cornell SE, Fetzer I, Bennett EM, Biggs R, Carpenter SR, de Vries W, de Wit CA, et al. 2015. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science. 3476223. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855.

- Thinley P, Lassoie JP. 2013. Human-wildlife conflicts in Bhutan: promoting biodiversity conservation and rural livelihoods in Bhutan. Conservation Bridge. Case Study No. 02. Retrieved from http://www.conservationbridge.org/casestudy/human-wildlife-conflicts-in-bhutan/Herring J (Producer). (2007). Human-Wildlife Conflicts in Bhutan, Video No. 02.Conservation Brodge.

- Tobgay S, Wangyel S, Dorji K, Wangdi T. 2019. Impacts of crop raiding by wildlife on communities in buffer zone of sakteng wildlife sanctuary, Bhutan. Int j sci res manag. 7(4):129–135. doi:10.18535/ijsrm/v7i4.fe01.

- Tomislav K. 2018. The concept of sustainable development: from its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb int rev econ bus. 21(1):67–94. doi:10.2478/zireb-2018-0005.

- Tong Y, Niu H, Fan L. 2016. Willingness of farmers to transform vacant rural residential land into cultivated land in a major grain-producing area of central China. Sustainability. 8(11):1192.doi. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su8111192.

- Tshering K, Thinley P. 2017. Assessing livestock herding practices of agro-pastoralists in western Bhutan: livestock vulnerability to predation and implications for livestock management policy. Pastoralism. 7(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s13570-017-0077-1.

- Tshewang U, Tobias M, Morrison J. 2021. Non-Violent Techniques for Human-Wildlife Conflict Resolution. In: Tshewang U, Tobias MC, Morrison JG, editors. Bhutan: conservation and environmental protection in the Himalayas. Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Gewerbestrasse 11,6330 Cham, Switzerland; pp. 71–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57824-4

- UN. 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations.

- Van Eeden LM, Crowther MS, Dickman CR, Macdonald DW, Ripple WJ, Ritchie EG, Newsome TM. 2018. Managing conflict between large carnivores and livestock. Conserv Biol. 32(1):26–34. doi:10.1111/cobi.12959.

- Verma R. 2017. Sdgs: value-added for GNH? Challenges and innovations of a development alternative from a socio-cultural lens. Druk J. 3(1):36–47.

- Verma R, Ura K 2022. Gender differences in gross national happiness: analysis of the first nationwide wellbeing survey in Bhutan. World Development, 150, 105714.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105714

- Wangchuk N, Pipatwattanakul D, Onprom S, Chimchome V. 2018. Pattern and economic losses of human-wildlife conflict in the buffer zone of Jigme khesar Strict nature Reserve (JKSNR), haa, Bhutan. J Trop for Res. 2(1):30–48.

- Williams S, Trewartha G, Cross MJ, Kemp S, Stokes KA. 2017. Monitoring what matters: a systematic process for selecting training-load measures. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 12:S2.101–2.106. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2016-0337.

- Yangka D, Newman P, Rauland V, Devereux P 2018. Sustainability in an emerging nation: the Bhutan case study. Sustainability, 10(5), 1622.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su10051622

- Yaw BA, Silvia B. 2019. Farmers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of strategies for managing wildlife crop depredation in Ghana. Int J Biodivers Conserv. 11(6):165–174. doi:10.5897/IJBC2019.1284.

- Yeshey F, M R, Keenan RJ, Nitschke CR. 2022. Subsistence farmers’ understanding of the effects of indirect impacts of human wildlife conflict on their psychosocial well-being in Bhutan. Sustain(Switzerland) (Switzerland). 1421:14050. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su142114050.

- Zakour MJ, Gillespie DF. 2013. Vulnerability theory. In: Zakour MJ, Gillespie DF, editors. Community disaster vulnerability, Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Springer; pp. 17–35.

- Zou T, Yoshino K. 2017. Environmental vulnerability evaluation using a spatial principal components approach in the Daxing’anling region, China. Ecol Indic. 78:405–415. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.03.039.