Abstract

The expert-driven and normative character of sustainability education aims to promote societal transformation and global change. While some authors underline the ethical claims of education, others have criticized that there is a problematic tendency to prescribe certain actions beyond ethical education. The article aims to provide an empirical contribution, including students’ and teachers’ perspectives, and geography textbooks, to the debate. Based on the results of an empirical study with 1001 secondary school students in Austria and Germany, we discuss the “ethical turn” and the moral code in sustainability education. The questionnaires are completed with students’ drawings, qualitative interviews with geography teachers and an analysis of geography textbooks. We argue that most students have a precise idea what sustainability and sustainable behavior means, but they harbor right-wrong binary perceptions of sustainable lifestyles. Many students lack knowledge of the interdependence of consumption and production networks, which impedes the understanding of complex sustainability patterns. Therefore, we recommend pluralistic and interconnected perspectives in sustainability, in the frame of school geography. A more democratic classroom contributes to develop an own moral compass. Additionally, passion and participatory approaches can help students reflect on their affective relationships with consumer goods and consider alternative consumption-production paradigms.

Introduction

In 2010, the Danish filmmaker Frank Poulsen released the documentary ‘Blood in the mobile’, illuminating the interconnection between terrible working conditions in a cassiterite mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo, resultant violent conflicts, and the production of mobile phones. Poulsen argued that mobile phone producers and consumers are co-financing the civil war in the Congo.

While some authors (e.g. Orr Citation1999) have embraced the “ethical turn” in education that has brought documentaries like ‘Blood in the mobile’ into the classroom, others have suggested ‘that the politics of blaming people for outcomes that they are not directly, in any causal sense, responsible for rests on a problematic model of moral agency’ (Young Citation2003; see also Evans, Welch, and Swaffield Citation2017). The debate on how the teaching of values should be approached in sustainability education is an ongoing struggle. As a result, teachers seek to find ways of engaging with value-based questions of consumption, production and sustainability that are neither utopian and universalizing, nor relativist and situated (Lotz-Sisitka and Schudel Citation2007).

This debate requires those involved in sustainability education to consider sustainable behavior from multiple viewpoints and at different scales, to make connections for students without alienating them through questioning behaviors that cannot easily be altered. We seek to question the “ethical turn” and the moral code in sustainability education. While this debate is often conducted on an ideological basis, this article aims to provide an empirical contribution, including students’ and teachers’ perspectives on ethics, and by using geography textbooks. First, we ask to what extent sustainability education conveys the “good cause” and encourages students to develop certain patterns of sustainable behavior. Second, we question how sustainability education impedes critical thinking and fails to provide an adequate context. Given the complexity of production and consumption networks, we investigate how connections between production and consumption are being drawn in geography education. Finally, we investigate opportunities for sustainability education to explore alternative approaches to the teaching of values, helping students to develop their own sustainability ethics. We commence with an introduction to the history and challenges of sustainability education.

Sustainable development and sustainability education

Since the United Nations Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro 1992, the concept of sustainable development (SD) has advanced to a guiding societal model, aided by the commitments of 173 states to SD. The Brundtland report (Brundtland Citation1987) and other documents bear traces of rational morality (Sund and Öhman Citation2014), which according to the philosopher Peter Singer, is a concept that ‘rests on principles, which provide its basis’ (Singer Citation1986, 22). Some of these principles are fundamental, others subsidiary. One fundamental principle is that ‘one’s conduct and one’s judgments should accord with one’s principles’ (ibid, 24). The rational morality of The Earth Charter (Citation2000) suggests that everyone shares responsibility for the present and future well-being of the human family. The Earth Charter initiative was an active partner of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), supporting the Decade of Education for SD (2005–2014) and the subsequent UN Global Action Programme (GAP) on Education for SD (2015–2019). Through these initiatives, the concept of SD was gradually introduced into formal education (Bagoly-Simó Citation2013; Varcher Citation2011), in geography, as well as other school subjects. With the implementation of the concept, questions related to rational morality and sustainability ethics arrived in school education.

Geography, as an academic discipline with a strong focus on human–environment interactions and the fate of the planet and its peoples, has a pedagogical commitment to SD. As a school subject, geography has ‘for at least 30 years more or less adopted the study of “economic development” and “environment” into its mainstream’ (Lambert and Morgan Citation2010, 135). In 2007, The International Geographical Union Commission on Geographical Education (IGU CGE) ratified the Lucerne Declaration on Geographical Education for SD (Haubrich, Reinfried, and Schleicher Citation2007; Bagoly-Simó Citation2013) to confirm its commitment to the SD concept. However, the distinction between weak and strong sustainability (Hertig Citation2011; Neumayer Citation2013) was not considered by curriculum designers, and weak sustainability still dominates the existing curricula in many countries (e.g. Curnier Citation2017). Weak sustainability means that the planet’s natural capital can be substituted with economic (financial) or human capital. The essence of strong sustainability is that it views natural capital as fundamentally non-substitutable (Neumayer Citation2013; Kowasch Citation2018). Neumayer defines strong sustainability as the ‘non-substitutability paradigm’ (ibid Citation2013, 25). In this article, we do not distinguish between weak and strong sustainability, because (geography) curricula, interviewed teachers and students used the two approaches interchangeably. However, we will come back to this problem in the discussion.

According to Rogers, Kazu, and Boyd (Citation2008, 22), sustainability is ‘the term chosen to bridge the gulf between development and environment’. Many scholars (e.g. Felber Citation2015; Wolff et al. Citation2017) are critical of using the term “development” as it indicates an indisputable belief in economic growth and technological progress. Therefore, like Wolff et al. (Citation2017) and other authors, we will use the concepts of “sustainability” and “sustainability education” (SE) in this article, except in situations when we refer to other authors using “SD” or “education for sustainable development” (ESD).

Morality and values in sustainability education

Sustainability education supports forms of practical instruction to help turn ethical obligations into actual conduct and action (Evans et al. Citation2017). Hertig (Citation2011, 19) argues that ESD is an ideological rather than a scientific concept. In this sense, sustainability education can be a form of “ethical education” that embraces universal aspects and concepts (Sund and Öhman Citation2011). The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) includes the concept of SD into its PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) framework and highlights sustainability as a global issue with universal value: ‘Global competence is the capacity to examine global and intercultural issues, to take multiple perspectives under a shared respect for human rights, to engage in open, appropriate and effective interactions with people from different cultures and to act for collective well-being and SD.’ (Mansilla Citation2017, 13). The OECD Global Competences also show that sustainability can be integrated into a broader framework of global education, together with other approaches such as social justice and equity or childhood nature-based education. Sustainability is, hence, one concept among others that students discuss to gain a broader perspective of global challenges.

Through the implementation of sustainability into curricula, national governments have aimed to provide information and ‘hopefully influence public opinion’ on environmental responsibility (Lambert and Morgan Citation2010, 134; see also Borg et al. Citation2014). The Austrian curriculum for the new high school exam in geography and economics, for example, stipulates that students should learn how to engage responsibly with the environment (BMB Citation2016). The German Educational Standards for the Intermediate School Certificate (DGfG Citation2014) in geography foster education for a more sustainable lifestyle and behavior. Students are to be familiarized ‘with environmentally and socially acceptable lifestyles, economic activities and products as well as solutions (e.g. use of public transport, renewable energy sources)’ (ibid Citation2014, 25).

In his book ‘Change everything: creating an economy for the common good’, Felber (Citation2015) pleads for a transition to an economic system based on universal values, set down in constitutions across the globe. These values include dignity, social justice, sustainability, and democracy, and do not include market domination and profit maximization. Hill (Citation2013) notes that global factors such as transnational capitalism, internet anarchy and addiction to daily news besiege the “common good”. He highlights that those who seek to revive the common good should prioritize two projects: ‘negotiating a richer value consensus in communities, and developing guidelines for the education of values’ (ibid Citation2013, 35).

While there is agreement that education and values matter, there are problems with a universal ethical project. First, according to Sund and Öhman (Citation2014), it raises a problem of democracy and whether the state should promote certain desirable values through compulsory schooling. Second, it brings to the forefront ethical concerns regarding reliance on external universalist values. Sund and Öhman (Citation2014, 650) caution against the uncritical presentation of universal values such as sustainability, because it ‘obscures the power relations that are built into them’.

Echoing the colonial past, Western interventions in the Global South today sometimes take the form of ‘educating’ people in the ways of sustainability, ecological transition and ‘green economy’ (Standish Citation2009). González-Gaudiano (Citation2006) notes that in international conferences where sustainability emerges as a theme, the representatives are predominantly from industrialized countries, with various minority cultural groups often sidelined (Stevenson Citation2007). Therefore, such interventions in terms of SD establish new divisions between a morally superior West and the supposedly not environmental-friendly South and ignore indigenous and localized knowledge of the environment and sustainability. In response to the hierarchy that comes from the perspective of Western environmental knowledge, Brazil’s Federal Institute of Pará, Rural Campus of Marabá (IFPA-CRMB) is an example of educational activism (Meek Citation2015) that acts as a ‘counterpoint to the neoliberal model that generates inequality and social exclusion’ (IFPA-CRMB Citation2010, 5).

The expert-driven and homogenizing concept of sustainability, as presented by UNESCO, fails to challenge the status quo and supports economic primacy, allowing a neoliberal agenda to dominate education policy (Curnier Citation2017; McKenzie Citation2012). Jickling and Wals (Citation2008) argue that ESD turns education into a political tool that promotes this dominant ideology. Sustainability education can, therefore, be ‘a way of letting market forces guide education’ (Sund and Lysgaard Citation2013, 1604). An empirical study in Lower Saxony (Germany), for example, has shown that the paradigm of economic growth still dominates geography textbooks (Kowasch Citation2017).

Sund and Öhman (Citation2014) critique inclusive morality that uses instrumental methods to sustain the future world. One of the crucial aspects of their perspective is to avoid turning sustainability education into a teaching of moral distinctions between good and evil and thus to ‘moralise the political’ (Citation2014, 650). Lambert and Morgan (Citation2010, 133–134) highlight that ‘teaching is not about what is right or wrong, but learning how to make worthwhile distinctions’, including the rejection of racist or sexist views, for example. A simplified right-wrong binary in teaching, however, doesn’t help students to understand why such behavior or views is ‘wrong’. Certain behaviors and viewpoints need to openly be discussed. Or, by using the words of Lovat (Citation2005, 11), values education is about ‘the teacher’s capacity to make a difference by engaging students in the sophisticated and life-shaping learning of personal moral development’. Indoctrination doesn’t help students to develop a ‘moral compass’ (Standish Citation2009, 40). Thus, the normativity problematized in this article is the tendency to use sustainability education as a platform for prescribing how to apply content, knowledge and ethics taught in SE beyond the learning context (Sund and Lysgaard Citation2013).

ESD 1 and ESD 2

We acknowledge that all education is normative in the sense that it has a purpose (see also McKeown and Hopkins Citation2003). Sauvé, Berryman, and Brunelle (Citation2007) and other authors (e.g. Kopnina Citation2016) do recognize the need to legitimize learning for sustainability to ensure that sustainability education achieves its purpose. This instrumental approach has been defined as ESD 1 by Vare and Scott (Citation2007). ESD 1 promotes changes in sustainable behavior and can be characterized as learning “for” SD. ESD 2, on the other hand, represents an emancipatory approach. Students explore contradictions inherent in sustainable living and should learn to think critically about what experts say. Thus, ESD 2 is learning “as” SD (Vare and Scott Citation2007; Kowasch Citation2017). While Vare and Scott (Citation2007) consider the two approaches as complementary, other authors (e.g. Biesta Citation2014; Jickling and Wals Citation2008; Öhman Citation2008) argue that instrumentalist approaches are incompatible with emancipation and critical thinking. The emancipatory approach relates to the view that “good education” should also include scope for students’ subjectivities (Andersson Citation2018). The process of subjectification possesses a degree of independence and self-oriented learning. According to Rancière (Citation1999), subjectification involves ‘dis-identification’ with the existing order. Therefore, it can guide students to challenge the most prevalent existing moral and economic paradigms, which in most western countries revolves around different variants of economic growth.

Geography, taught in schools in Austria and Germany, hardly distinguishes between the two approaches. Depending on the teaching methods and media used, school education orients toward either ESD 1 or ESD 2, or even combines them. In the following, we use ESD and SE to describe both approaches implemented in school geography.

Sustainable consumption and individualized responsibilities

Moral distinctions toward sustainability underlie individualized responsibilities for social change (Evans et al. Citation2017; Shove Citation2010). Shove’s influential diagnosis of climate policy is instructive for the debate on moral issues in geography teaching concerning sustainability. Based on what she terms the ABC framework (A for ‘attitude’, B for ‘behavior’ and C for ’choice’), she notes that ‘responsibility for responding to climate change is a thought to lie with individuals whose behavioral choices will make the difference’ (Shove Citation2010, 1274). In response, Whitmarsh, O’Neill, and Lorenzoni (Citation2011) have acknowledged Shove’s concerns about individualizing responsibilities, but cautioned not to ‘move too far in the other direction’ (ibid Citation2010, 259), toward structural political economy responses and away from individuals. A headline in the German weekly newspaper Der Spiegel in April 2015, ‘Buying to save the world’, (Der Spiegel Citation2015) emphasized the arrival of the ongoing debate on responsibility and consumption behavior in Germany. Attitudes and behaviors are components of the affective domain—in contrast to the cognitive domain (Berglund, Gericke, and Chang Rundgren Citation2014)—and relate to emotions (Kollmuss and Agyeman Citation2002).

Sustainable consumption and consumption-related behaviors are a political project that materialized at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 (Evans et al. Citation2017). According to Resenberger (Citation2017), both environmental conscience and non-sustainable consumption behavior have increased for some years. In parallel to an increasing consumerism, a critical movement on the moralization of consumption acts has emerged (Fridrich Citation2017; Kowasch et al. Citation2018). This movement deals with the question to which extent consumers are responsible for the production conditions and networks of the purchased goods (Ermann Citation2006). Massey (Citation2004), for example, notes that these forms of moralization overestimate the capacity of individuals to affect global changes.

Consumers often do not question the production network of the goods they acquire, making a disconnection between the raw materials, crops and animals that are at the beginning of production chains. Recognizing their interdependence can refresh jaded debates about sustainability by reframing discussions about environment, globalization and development (Lambert and Morgan Citation2010). The concept of interdependence is key to the kinds of relational understandings underpinning what Jackson (Citation2006) calls ‘thinking geographically’. Consequently, we discuss consumption patterns of students and question their thoughts on sustainable behavior and production networks. Before doing so we will first explain the framework of our empirical study and present the results.

Methods

Based on an extensive literature review, we investigate the extent of moralization in sustainability education and its effects by analyzing data obtained from a large-scale empirical study with secondary school students in Austria and Germany, supplemented with qualitative interviews held with geography teachers, an analysis of geography textbooks and students’ drawings. Our research focuses on Styria (Austria), Bremen and Lower Saxony (both Germany), because of classroom experience in each of the three case studies.

We carried out questionnaires in each area throughout 2017 and 2018. In total 1001 students between 11 and 18 years from 25 different schools responded. Three of the participating schools are located in Bremen (152 students), four in Lower Saxony (329 students) and 18 in Styria (520 students). We had personal contacts with all the participating schools in both countries. While all states in Austria follow the same school curriculum, Germany’s 16 federal states each have their own ministry of education responsible for their curriculum, making it necessary to differentiate between Lower Saxony and Bremen.

Austria and Bremen have a K-12 educational system. Lower Saxony reverted to a K-13 system, which means that students have 13 years of schooling from primary school to high school graduation (called “Abitur” in Germany and “Matura” in Austria) (Bruckner and Kowasch Citation2018). The questionnaire used closed, half-closed and open questions to investigate the students’ relationship with the concept of sustainability and was divided into three parts. In the first part, we asked students to define sustainability. The second part focused on the way students have encountered the concepts of sustainability and consumption in school and investigated their knowledge about natural resources. The third part addressed student relationships with sustainability and consumption patterns outside the school context. The questionnaires occurred during regular lessons, required student consent and a teacher was present at all times. We informed students they did not have to respond to the whole questionnaire. For this article, we chose to analyze questions on values education, moralization, teaching methods and sustainable behavior, using descriptive statistics with MS Excel and SPSS.

There is always a gap between what interviewed people say and what they do (e.g. Engartner and Heiduk Citation2015; Heidbrink, Schmidt, and Ahaus Citation2011) and that there are limitations to empirical studies in the classroom. Questionnaires can simply elicit what young people think teachers (or researchers) expect from them. Observing the respondents while they are purchasing consumer goods in a supermarket, for example, would be a useful way to control responses, but could not account for online shopping behaviors. Qualitative interviews based on lead questions with students on ethics and values in SE could give deeper insights into student perceptions. But the mixed method used in this study, including questionnaires, drawings, interviews with teachers and textbook analyses, can provide an extensive information base and open the floor for further discussion and research.

Qualitative interviews with geography teachers took place in either the school or at our university offices, guaranteeing a professional setting. The eight, recorded interviews (four in Lower Saxony, three in Styria and one in Bremen) followed an interview guide and lasted between 20 and 30 minutes. The interviews centered on sustainability content knowledge, critical thinking, and moralization, and were analyzed qualitatively through content analysis (Mayring Citation2015). Data gained from the questionnaires and interviews was further supplemented by two to three students from each class participating in the survey, selected by the responsible teacher, who were asked to draw their personal understanding of sustainability. We categorized the drawings according to the content and to the (non-) normative character of sustainability. The content categories included agriculture and food, timber industry, energy, transport/mobility, waste, electronic devices and a combination of different contents. The categories for the (non-) normative character of the drawings included right/wrong approach, (non-) moralizing conversation, labels and positive/negative visions of the future.

Finally, we examined three different upper secondary school geography textbooks from Austria and Germany. Following Mayring’s content analysis (Mayring Citation2015) we used a technique of structuration to analyze the sample of textbooks. We investigated the textbooks, which dedicated at least one page to either coltan extraction and/or mobile phones, as an example for consumer goods relevant to most teenage students. We analyzed if there are interconnections between production and consumption patterns and if students are encouraged to critically analyze resource conflicts.

Findings: moral directions in sustainability education

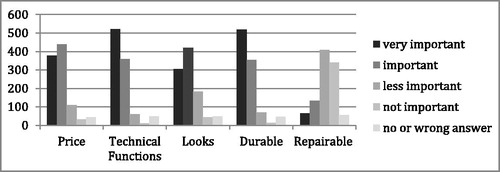

Students bring their own moral principles and ideas about consumption behavior to school. Conversely, the way consumption patterns are discussed in school influences or even moralizes students’ consumption behavior outside of school. The questionnaires showed that 89% of the respondents replied that distinctions between “good” and “bad” shopping have been made in class. By considering these prevalent moral distinctions, we asked what criteria students consider as important when buying a mobile phone and other electronic devices. The results indicate that the students consider the reparability of a phone as less important than other criteria. They care most about the durability and the technical functions of the phone ().

Figure 1. Importance of different criteria when students buy a mobile phone (sample: 1001 students). Source Authors 2017–2018.

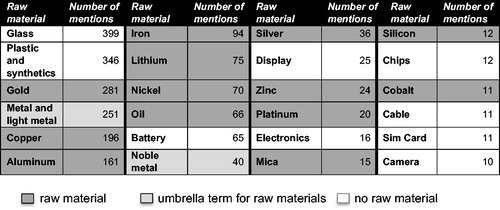

According to Garlake (Citation2007, 114), we live in a world today ‘where everything is literally connected to everything else’. Educators can plan lessons that illuminate this kind of thinking. The production of jeans is an example demonstrating how consumer choices affect producers in another country. This also applies to mobile phones. To investigate the extent to which students understand this connection, we asked for a list of raw materials that are part of a phone. In total, students came up with 110 different materials. shows the materials that have been named at least 10 times.

Materials shaded in dark gray are the raw materials found in a phone, and materials shaded in light gray are umbrella terms for different types of metal and materials. The unshaded cannot be classified as raw materials. The materials that students named most often were glass, plastics and synthetics (in white). Raw materials used in the production of mobile phones (in dark grey) and listed frequently were gold, copper and aluminum (but not, for example, coltan). One challenge concerns what we expect students to do with information on the environmental and economic impacts of global production networks. Doerr et al. (Citation2007, 296) quoted a teacher who notes that ‘it doesn’t matter what I say. It matters what sense students make of what I say’.

The students’ drawings give insights into how they interpret the concept of sustainability and how they reflect on their own behavior. Of the 43 drawings, 20 showed a ‘right-wrong’ opposition of sustainability and 15 combined several issues (energy, agriculture, etc.). Eight drawings primarily or partially focused on mobile phones. While mainly concerned with the phone’s durability, no students depicted the production process or the exploitation of resources involved in its manufacture. , for example, shows the difference between “non-sustainable people” who buy a new iPhone every six months and “sustainable people” who keep the same phone iPhone over the same time span.

Another drawing presents a student who thinks that food (a yoghurt in this case) is not bad despite the expiry date has already passed ().

The moral code of sustainability education is present in many drawings and is highlighted by the teachers interviewed. Almost all teachers agreed that values are part of sustainability education but they want students to be critical and make conscious decisions:

‘(…) So I’m trying to leave moralization out, because I do not want to stand here and say ‘yes, all those who eat meat will be demonized’ (Interview in Lower Saxony, 1/9/2017). Another teacher from a high school in Lower Saxony argued that ‘we should educate the adolescents to be self-critical people. And that does not work if I impose a doctrine and say ‘you have to act in a way I think it right’ (Interview, 1/9/2017).

Our interview results support the questionnaire data. shows different methods and media that are used to teach the concept of sustainability, according to the students surveyed. It is obvious that textbooks are the most common medium of instruction dealing with sustainability in school (33.8% of given answers), followed by film/video and worksheets. Fieldtrips related to sustainability topics were only mentioned 19 times out of 1227 answers (1.5%). Only two of the interviewed geography teachers organized fieldtrips to explore sustainability. A teacher from Hanover in Lower Saxony explained that she visited a factory making utility vehicles with her class (Interview, 31/8/2017). Another geography teacher, also from Hanover, took students to a recycling center (Interview, 1/9/2017).

Table 1. Methods and media used in geography teaching in the frame of sustainability education, according to the interviewed students (several answers possible). Source Authors 2017–2018.

Examined geography textbooks also moralized sustainability issues. For example, the textbook “Vernetzungen” (Interconnections) (Derflinger et al. Citation2016) used in grade 9 in Austria, talks about coltan extraction in a chapter about developing countries. The center of the page features an extract from an online article titled ‘What do our phones have to do with the Congo?’ ‘Coltan’, it is stated, ‘is a treasure for some and a curse for others. […] The ones who cannot work anymore due to exhaustion from working in the humid heat, are beheaded or shot.’ (ibid Citation2016).

A positive example of a multi-perspective approach to the topic can be found in “Fundamente” (fundaments) (Korby, Kreus, and von der Ruhren Citation2014), a textbook for upper secondary schools in Lower Saxony, on a double page that is meant for training and evaluating student competency. The assignment is a mystery task that states ‘because Karl had to buy a new phone, Phil Webster in Australia was dismissed from his job’ [in the Wodgina mine, which was closed because coltan was sourced at lower costs from DR Congo]. Students are encouraged to explain the relationship between Karl and Phil by using 18 mystery cards. Mysteries are suited to sustainability teaching because they contribute to understanding the complexity of conflicts and the interdependence of globalized production networks. However, the cards must provide a variety of perspectives that include critical voices, and students need to engage in a de-brief in order to discuss solutions. If not, they risk becoming moralizing, as demonstrated in the textbook “Terra” (Werner Citation2017) in the German state of Berlin-Brandenburg. The mystery titled ‘The blood in the mobile’ mainly focuses on the poor working and living conditions in Congo, and on environmental impacts of coltan mining. None of the 22 cards gives information on companies or organizations, which ignores the interdependence of the actors involved in the production of mobile phones.

Discussion: ethical education and moralization in sustainability education

There are five key issues at stake regarding moralization, values and consumption in sustainability education that emerge from our empirical study. The consumer is a well-established figure in contemporary politics and commerce, and tends to be perceived as a self-evident category (Evans et al. Citation2017). There are increasing appeals to politicians, companies and consumers to advocate for more ethics in production and consumption of food and other consumer goods (Engartner and Heiduk Citation2015). According to the students interviewed, consumption patterns are widely discussed in school education. The results of the study (e.g. ) in Austrian and German secondary schools are in line with the findings of Resenberger (Citation2017) who notices that the consumption behavior of individuals is increasingly paradoxical and “hybrid”. Combinations of different behavioral patterns are the contemporary norm, for instance the drinking of fair-trade coffee from plastic cups, or the purchase of the latest smartphone while concurrently shopping for regional food from an organic market. Protection of nature and sustainability are balanced against other purchasing arguments and do often not represent the most important variable in purchasing decisions.

In October 2017, the German weekly newspaper Die Zeit (Citation2017) asked if ethical consumption is at all possible, considering the overwhelming number of product labels. The complexity of production networks, animal welfare, child labor and transport modes make it difficult for consumers to make decisions. Referring to the ABC (attitude, behavior, choice) framework developed by Shove (Citation2010), various aspects influence the choice of consumers. Classic advertising in different media, social media, friends, parents, the financial background and school education shape young people and influence their criteria when purchasing consumption goods such as mobile phones (). Returning to Massey (Citation2004), we have to ask if the responsibility placed on the consumer overestimates the individual’s capacity to affect sustainability patterns and global changes.

There is a disconnection between production and consumption in school geography—a discipline able to illustrate these connections. The contextualization of production networks contributes to an understanding of the global dimension of responsibilities and helps to ground these in the daily life of students. But often, SE focuses on consumption and neglects the raw materials that are part of the production process, or focuses on resource extraction without considering consumer goods. The interdependence of production networks and consumption patterns is lacking in school geography. This was apparent in a study of 13 German geography textbooks by Kowasch (Citation2017), and was also apparent in this study. It results in a general lack of knowledge on raw materials as highlighted by the students questioned about raw materials used to produce a smartphone ().

The student drawings ( and ) and questionnaires show that students have a precise idea what sustainable behavior means, at least in their context in Western Europe. Bengtsson (Citation2016) seeks to demonstrate that SE policies are not hegemonic prescriptions, because they leave room for contestation, dissension and various interpretations (see also Hertig Citation2011; Varcher Citation2011). Sustainability education policies are adapted in different contexts and they do not necessarily oppose the subjects’ agency through individual action. Bengtsson’s arguments position SE as a strategy for ‘environmental protection’ and they have been disputed (Berryman and Sauvé Citation2016, 79). Even though there is ‘some room for debate about values and resources, and their sustainability, the cards are already anthropocentrically loaded’ (ibid Citation2016, 106). This argument can be observed in the student drawings that place humans in the forefront ( and ). Weston (Citation1992) also noted that environmental ethics are ‘profoundly shaped by and indebted to the anthropocentrism that they officially oppose’. Therefore, we think that a more democratic classroom can contribute to discussing different viewpoints on sustainability and sustainable lifestyles. The appropriate metaphor here is ‘discussion’ in which ideas concerning sustainability can be put forward by students and teachers. Habermas (Citation1990) defines it as ‘communication knowledge’: the knowledge that results from engagement and interrelationship with others. It should include ‘self-confrontation’, which demands that students confront how they ascribe meaning to their ideas, knowledge, values and interests (Wals Citation2010, 144).

The discussion should also include the distinction between weak and strong sustainability (Neumayer Citation2013), which is helpful to understand different definitions of SD and sustainability. Weak sustainability evokes the concept of business as usual, which maintains the idea that economic growth is essential to prosperity. It also means the challenges of sustainability require only small changes in lifestyle (toward a “green economy”) (Macy and Johnstone Citation2012). Strong sustainability refers to approaches such as the transition movement or solidarity economy (Brand and Wissen Citation2017). School environments should discuss the different approaches and concepts to give space for alternative paths of development and for contextual differences. Of course, this plea for pluralism might lead to a kind of relativism in which any perspective or position on sustainability is as good as another (ibid Citation2010). In contrast to such a ‘crude relativism’ (Baggini and Fosl Citation2003), a ‘heuristic relativism’ (Meggill Citation1995, 35) allows people to ‘travel some distance beyond their own position in order to see reality from another point of view’.

Many student drawings focused on the binary of good and bad consumption and demonstrated that SE conveys the “good cause”. The students seemed to be encouraged to develop certain patterns of sustainable behavior. As the SD Goals highlight, certain behavior linked to sustainability (organic farming, zero waste, consume less, etc.) has universal value (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2018). When international organizations and national curricula suggest that certain universal values are desirable in education, there is ‘a risk that we fail to see the limits of educational thought’ (Sund and Öhman Citation2014, 650). According to Sauvé et al. (Citation2007), the need for action discourages reflexivity and critical thinking. There is little space for students to generate own ideas. As Standish (Citation2009, 183) highlights: ‘Instructing students in how they should live their lives and the values to which they should conform is tantamount to denying them the possibility to shape their own future.’ The national liberal model of education seeks to create moral citizens, but instead the cosmopolitan approach undermines the moral itself (Standish Citation2009). The student drawings mainly highlight universal values linked to sustainability, but nevertheless, they provide some interesting ideas, for example concerning the best-before date for food ().

The empirical study in Austrian and German schools shows that fieldtrips are uncommon (). According to Bruckner and Kowasch (Citation2018), there are several challenges that often hamper direct environmental experiences. First, geography curricula (and also those of other subjects) stipulate few or no field trips and other embodied approaches. Second, teachers explained that the organization of direct environmental experiences necessitates time and engagement (booking transport, etc.). Third, timetables and internal school programs have to be adjusted.

However, a more actively engaged and participatory experience can support free opinion-making and enhance students’ competencies to act (e.g. Huckle Citation1999; Vare and Scott Citation2007). Participatory approaches are part of a communication turn and involve diverse interest groups. They are in line with pluralistic approaches to sustainability education (Wals Citation2010) and with embodied, situated and direct environmental experiences (Payne Citation1997; Bruckner and Kowasch Citation2018). Referring to Wals (Citation2010, 144), pluralistic approaches depend on the creation of respect and openness, ‘for being sensitive to values and norms that differ from one’s own’. Embodied approaches have been highlighted as important by academic geographers writing on emotion and affect (Hayes-Conroy and Hayes-Conroy Citation2013; Bruckner and Kowasch Citation2018). They can promote a relational understanding of sustainable consumption and development. Nature immersion (Weston Citation1992), or school gardens (Kopnina Citation2018) allow students to develop intrinsic values toward plants and animals. Intrinsic value is ‘the value of a thing for its own sake, above and beyond any value it may provide to others or its instrumental values’ (Batavia and Nelson Citation2017; Kopnina Citation2018). Therefore, students can learn about moral consideration of nonhumans and discover post-materialist values. The inclusion of alternative educational approaches such as direct environmental experiences, gardening and fieldtrips prompt students to reflect on their affective relationships with consumer goods. An immersion in nature—common in the teaching of physical geography—leads to a trans-human experience. Such environmental experiences support what Weston (Citation1992, 335) calls ‘nonanthropocentrism’. Alternative educational approaches like these can also help ‘students and teachers move past the judgment and moralizing that otherwise stall an engagement with ESD’ (Bruckner and Kowasch Citation2018, 16). Practice opens space for interaction and exploration.

Including practice valorizes and draws upon students’ life experiences as pedagogical elements. Like the aforementioned Federal Institute of Pará (Brazil), the aim is not simply to reproduce the social-economic reality into which it is inserted (Meek Citation2015), but to train students to ‘organize their territories according to the reproduction of their existence, contributing to family subsistence, community life, and the larger sustainability of southeastern Pará’ (IFPA-CRMB Citation2010, 21; Meek Citation2015, 420). Such hybridized knowledge can thus contribute to alternative approaches to sustainability education and provide the development of a critical citizenry.

Conclusion

Sustainability is an idea that should be addressed in schools, and particularly in the teaching of geography. But there is a paradox here (Wals Citation2010). On the one hand, there is a deep concern about the state of the planet and a sense of urgency that requires a break with unsustainable lifestyles, behavior and economic systems and requires action. On the other hand is the belief that it is wrong to indoctrinate and persuade people toward a more sustainable thinking and acting (ibid, 150). Thus, the universal values promoted by the likes of the OECD and UNESCO can lead to indoctrination and moralization. Students should have the ‘possibility to shape their own future’ (Standish Citation2009, 183) and become citizens that make ‘worthwhile distinctions’ (Lambert and Morgan Citation2010, 136). These calls for self-determination are in a state of tension with claims for education “for” SD and behavior modification.

Our findings, though limited to two countries, suggest some worthwhile modifications to sustainability education. We call for a discussion on the different definitions of sustainability in policy documents and school curricula. Today, there are many competing paradigms, which lead to ‘confusion by those who interpret it differently either by fault or intention’ (Aikens, McKenzie, and Vaughter Citation2016; Smyth Citation1995). Sustainability education cannot reinforce an existing neoliberal status quo, which results in continuing ‘business as usual’ as highlighted by Swyngedouw (Citation2007). Mass consumption forms our daily reality and sustainability criteria (local production, reparability, etc.) compete with other arguments when purchasing consumption goods.

We recommend more pluralistic and interconnected perspectives in sustainability education. The connections between different locations, noted one of Gersmehl’s (Citation2005) four foundational ideas for geography teaching, should be explained so that students obtain a better understanding of complex systems. Today, economic activities connect numerous localities that otherwise have no obvious relationship. The lack of knowledge on raw materials in mobile phones () leads us to question the concept of interdependence’s visibility within sustainability education and seek its enhancement.

We support a more democratic classroom. From our data, we have found that students are strongly oriented toward behavior modification rather than values education. We advocate a sustainability frame of mind, which does not promote certain ‘answers’, but an effective democratic participation in classroom discussions and societal development. Referring to Standish (Citation2009, 184), the ‘loss of faith in the individual moral selves of students parallels a more widespread loss of faith in social progress’. Faith in social progress could be achieved through the reorientation of teaching culture from giving moralizing prescriptions toward a faith in students’ capacity to act and participate in decision-making. Nevertheless, the classroom should remain a place where students can try and propose new ideas, and where they are not responsible for ‘real decisions’. This leads to the problem of normative evaluation: how can students develop new ways and solutions if they are under pressure from grading? This question requires further research.

Sustainability education should promote an inner curiosity and passion ‘about the reasons and causes for the world’s being as it is’ (Kronman Citation2007, 216). Alternative approaches to SE such as direct environmental or embodied experiences can encourage students to learn with all senses and to develop critical thinking by questioning how marketing, labels and taste/feeling are interconnected. Through field trips—a teaching method that is still not used very often ()—to a farm or a minerals processing plant, students can gain new perspectives of how consumer goods are produced, including working conditions, animal welfare or waste disposal. Moreover, re-investing in another (consumption/production) logic ‘cannot be done without affect or passion’ (Andersson Citation2018, 651).

Restructured schools have the power to promulgate alternative approaches and conceptions of environmental knowledge (Meek Citation2015) and sustainability education. They can incorporate analyses of regional political economy and ecology into sustainability in order to promote a hybridized knowledge and critical citizenry. In doing so, they should introduce other concepts such as social justice and equity, subsistence farming or solidarity-based economy in addition to sustainability.

We recommend values education and training in sustainability education to become a part of teacher qualifications, in which sustainability opens the horizon to multiple values and perspectives, as well as the development of intrinsic values toward nature. Wolff et al. (Citation2017) identified the need for sustainability [among other concepts] to ‘become a canon in teacher education in Finland and elsewhere’ (Wolff et al. Citation2017, 32). In addition, we see the responsibility that universities and teacher colleges are at the forefront of pluralistic approaches to sustainability in education. Promoting awareness about moralization in SE and encouraging future teachers to reflect on it would allow the integration of a multitude of perspectives and a more complex teaching of subject matters. Self-reflexivity and taking pluralistic approaches toward diverse interests, ideas and values can contribute to developing moral compasses, while avoiding moral impasses.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the young people and teachers who participated in this study and their schools for letting us visit them. We are particularly grateful to Simon Batterbury (Lancaster University) and Philippe Hertig (HEP Vaud) for fruitful input, comments and discussions, and to Alexander Cullen (University of Melbourne), Scott Robertson (Australian National University), Jan Florin (University of Vienna) and Noah Johnston (Montclair State University) for proof reading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Matthias Kowasch

Matthias Kowasch is currently an Assistant Professor at department of Geography and Regional Science, University of Graz (Austria). His research focuses on education for SD (ESD), geographical education, political ecology, mining governance, resources, consumption and indigenous people. Starting in October 2018, he will be a Professor at University College of Teacher Education Styria (Austria).

Daniela Franziska Lippe

Daniela Franziska Lippe is pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Geography and a Master’s degree to teach Geography and English at secondary schools. Her main research interests include sustainability and education for SD.

References

- Aikens, K., M. McKenzie, and P. Vaughter. 2016. “Environmental and Sustainability Policy Research: A Systematic Review of Methodological and Thematic Trends.” Environmental Education Research 22 (3):333–359. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1135418.

- Andersson, P. 2018. “Business as Un-usual Through Dislocatory Moments—Change for Sustainability and Scope for Subjectivity in Classroom Practice.” Environmental Education Research 24 (5):648–662. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1320704.

- Baggini, J., and P. S. Fosl. 2003. The Philosopher’s Toolkit: A Compendium of Philosophical Concepts and Metjods. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Bagoly-Simó, P. 2013. “Tracing Sustainability: An International Comparison of ESD Implementation into Lower Secondary Education.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 7 (1):95–112. doi:10.1177/0973408213495610.

- Batavia, C. and M.P. Nelson. 2017. “For Goodness Sake! What Is Intrinsic Value and Why Should We Care?” Biological Conservation 209: 366–376, doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.03.003.

- Bengtsson, S. 2016. “Hegemony and the Politics of Policy-making for Education for Sustainable Development: A Case Study in Vietnam.” The Journal of Environmental Education 47 (2):77–90. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1021291.

- Berglund, T., N. Gericke, and S.-N. Chang Rundgren. 2014. “The Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development in Sweden: Investigating the Sustainability Consciousness Among Upper Secondary Students.” Research in Science & Technological Education 32 (3):318–339. doi:10.1080/02635143.2014.944493.

- Berryman, T., and L. Sauvé. 2016. “Ruling Relationships in Sustainable Development and Education for Sustainable Development.” The Journal of Environmental Education 47 (2):104–117. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1092934.

- Biesta, G. 2014. The Beautiful Risk of Education. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

- BMB (Bundesministerium für Bildung). 2016. Lehrplan AHS Oberstufe NEU. Retrieved from: https://www.bmb.gv.at/schulen/unterricht/lp/lp_ahs_oberstufe.html. Accessed November 4, 2017.

- Borg, C., N. Gericke, H.-O. Höglund, and E. Bergman. 2014. “Subject- and Experience-bound Differences in Teachers’ Conceptual Understanding of Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 20 (4):526–551. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.833584.

- Brand, U., and M. Wissen. 2017. Imperiale Lebensweise. München: Oekom Verlag.

- Bruckner, H., and M. Kowasch. 2018. “Moralizing Meat Consumption: Bringing Food and Feeling into Education for Sustainable Development.” Policy Futures in Education 1–20. doi:10.1177/1478210318776173.

- Brundtland, G. H. 1987. Our Common Future. The World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Curnier, D. 2017. “Quel rôle pour l’école dans la transition écologique? Esquisse d’une sociologie politique, environnementale et prospective du curriculum prescrit.” Doctoral thesis, Faculty of Geosciences and Environment, University of Lausanne.

- Derflinger, M., G. Menschik, P. Atzmanstofer, J. White, and R. Huber. 2016. Vernetzungen. Linz: Trauner Verlag.

- DGfG (German Geographical Society). 2014. Educational Standards in Geography for the Intermediate School Certificate. Bonn: DGfG.

- Der Spiegel. 2015. Kaufen um die welt zu retten. Der Spiegel, no. 16, 11 April 2015, Hamburg: Spiegel.

- Die Zeit. 2017. “Wie ich als Verbraucher beinahe den Verstand verlor.” Die Zeit 42/2017. Retrieved from: https://www.zeit.de/2017/42/konsum-verbraucher-verantwortungsbewusstsein-waren. Accessed March 20, 2018.

- Doerr, A., M. Ruffus, F. Chambers, and M. Keefer. 2007. “The Changing Role of Knowledge in Education.” Education, Knowledge and Economy 1 (3):279–300. doi:10.1080/17496890701615055.

- Engartner, T., and N. Heiduk. 2015. “Reflektierter Konsum. Leitlinien Einer an Ethischen Prinzipien Orientierten Sozialwissenschaftlichen Konsumbildung.” GWP – Gesellschaft. Wirtschaft. Politik 64 (3):335–344. doi:10.3224/gwp.v64i3.20753.

- Ermann, U. 2006. “Geographien Des Moralischen Konsums: Konstruierte Konsumenten Zwischen Schnäppchenjagd Und Fairem Handeln.” Berichte Zur Deutschen Landeskunde 80 (2):197–220.

- Evans, D., D. Welch, and J. Swaffield. 2017. “Constructing and Mobilizing ‘the Consumer’: Responsibility, Consumption and the Politics of Sustainability.” Environment and Planning A 49 (6):1396–1412. doi:10.1177/0308518X17694030.

- Felber, C. 2015. Change Everything: Creating an Economy for the Common Good. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- Fridrich, C. 2017. “Verbraucherbildung im Rahmen einer umfassenden sozioökonomischen Bildung. Plädoyer für einen kritischen Zugang und für ein erweitertes Verständnis.” In Abschied vom eindimensionalen verbraucher, edited by C. Fridrich, R. Hübner, K. Kollmann, M. Piorkowsky and N. Tröger,113–160. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Garlake, T. 2007. “Interdependence.” In Teaching the Global Dimension: Key Principles and Effective Practice, edited by D. Hicks and C. Holden. London: Routledge.

- Gersmehl, P. 2005. Teaching Geography. New York: Guilford Press.

- González-Gaudiano, E. J. 2006. “Schooling and Environment in Latin America in the Third Millenium.” Environmental Education Research 13 (2):155–169.

- Habermas, J. 1990. Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action, translated by C. Lenhardt and S. Nicholson. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

- Haubrich, H., S. Reinfried, and Y. Schleicher. 2007. “Lucerne Declaration on Geographical Education for Sustainable Development.” In Geographical Views on Education for Sustainable Development, edited by S. Reinfried, Y. Schleicher, and A. Rempfler, Proceedings of the Lucerne-Symposium, Switzerland, Lucerne: IGU, July 2007. Geographiedidaktische Forschungen 42: 243–250.

- Hayes-Conroy, J., and A. Hayes-Conroy. 2013. “Veggies and Visceralities: A Political Ecology of Food and Feeling.” Emotion Space and Society 6:81–90. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2011.11.003.

- Heidbrink, L., I. Schmidt, and B. Ahaus. 2011. “Einleitung – Der Konsument zwischen Markt und Moral.” In Die Verantwortung des Konsumenten. Über das Verhältnis von Markt, Moral und Konsum, edited by L. Heidbrink, I. Schmidt, and B. Ahaus,9–24. New York: Frankfurt am Main.

- Hertig, P. 2011. “Le Développement Durable: un Projet Multidimensionnel, un Concept Discuté.” Formation et Pratiques D’enseignement en Questions 13:19–38.

- Hill, B. V. 2013. “Do Values Depend On Religion? Would It Be Best If They Didn’t?” In The Routledge International Handbook of Education, Religion and Values, edited by J. Arthur and T. Lovat,28–41. London: Routledge.

- Huckle, J. 1999. “Locating Environmental Education between Modern Capitalism and Postmodern Socialism: A Reply to Luce Sauvé.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 4 (1):36–45.

- IFPA-CRMB (Federal Institute of Pará-Rural Campus of Marabá) P. 2010. Rojeto político pedagógico. Marabá: Ministério da Educação.

- Jackson, P. 2006. “Thinking Geographically.” Geography 91 (3):199–204.

- Jickling, B., and A. E. J. Wals. 2008. “Globalization and Environmental Education: Looking Beyond Sustainable Development.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 40 (1):1–21. doi:10.1080/00220270701684667.

- Kollmuss, A., and J. Agyeman. 2002. “Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-environmental Behavior?” Environmental Education Research 8 (3):239–260. doi:10.1080/13504620220145401.

- Kopnina, H. 2016. “Metaphors of Nature and Development: Reflection on Critical Course of Sustainable Business.” Environmental Education Research 22 (4):571–589. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1007338.

- Kopnina, H. 2018. “Plastic Flowers and Mowed Lawns: The Exploration of Everyday Unsustainability.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability. 1–25. doi: 10.1080/17549175.2018.1527780

- Korby, W., A. Kreus, and N. von der Ruhren. 2014. Fundamente. Geographie Oberstufe. Stuttgart: Ernst Klett Verlag.

- Kowasch, M. 2017. “Resource Exploitation and Consumption in the Frame of Education for Sustainable Development in German Geography Textbooks.” RIGEO 7 (1):48–79.

- Kowasch, M. 2018. “Nickel Mining in Northern New Caledonia—A Path to Sustainable Development?” Journal of Geochemical Exploration 194:280–290. doi:10.1016/j.gexplo.2018.09.006.

- Kowasch, M., C. Fridrich, A. Oberrauch, C. Oesterreicher, L. Pichler, and M. Schwendtner. 2018. “Dekonstruktion Des Klassischen Konsumansatzes – ein Unterrichtsvorschlag.” GW-Unterricht 150 (2):34–50. doi:10.1553/gw-unterricht150s34.

- Kronman, A. 2007. Education’s End: Why Our Colleges and Universities Have Given up on the Meaning of Life. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Lambert, D., and J. Morgan. 2010. Teaching Geography 11-18—A Conceptual Approach. New York: Open University Press.

- Lovat, T. 2005. “Values education and teachers’ work: a quality teaching perspective.” Keynote address at the national values education forum, Australian Government Department of Education Science and Training. Canberra: National Museum.

- Lotz-Sisitka, H., and I. Schudel. 2007. “Exploring the Practical Adequacy of the Normative Framework Guiding South Africa’s National Curriculum Statement.” Environmental Education Research 13 (2):245–263. doi:10.1080/13504620701284860.

- Macy, J., and C. Johnstone. 2012. Active Hope. How to Face the Mess We’re in Without Going Crazy. Novato: New World Library.

- Mansilla, V. B. 2017. “Educating for Global Competence.” Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education, OECD NAEC Seminar. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/naec/Education_for_Global_Competence_BOIX_MANSILLA.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2018.

- Massey, D. 2004. “Geographies of Responsibility.” Geografiska Annaler 86B (1):5–18. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00150.x.

- Mayring, P. 2015. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. Weinheim/Basel: Beltz.

- McKenzie, M. 2012. “Education for Y’all: Global Neoliberalism and the Case of a Politics of Scale in Sustainability Education Policy.” Policy Futures in Education 10 (2):165–177. doi:10.2304/pfie.2012.10.2.165.

- McKeown, R., and C. Hopkins. 2003. “EE ≠ ESD: Defusing the Worry.” Environmental Education Research 9 (1):117–128. doi:10.1080/13504620303469.

- Meggill, A. 1995. “Relativism, or the Different Senses of Objectivity.” Academic Questions 8 (3):33–39.

- Meek, D. 2015. “Taking Research with Its Roots: Restructuring Schools in the Brazilian Landless Workers' Movement upon the Principles of a Political Ecology of Education.” Journal of Political Ecology 22 (1):410–428. doi:10.2458/v22i1.21116.

- Neumayer, E. 2013. Weak Versus Strong Sustainability. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Öhman, J. 2008. “Environmental Ethics and Democratic Responsibility.” In Values and Democracy in Education for Sustainable Development: Contributions from Swedish Research, edited by J. Öhman,17–32. Malmö: Liber.

- Orr, D. 1999. “Education for Globalisation.” The Ecologist 29 (2):166–168.

- Payne, P. 1997. “Embodiment and Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 3 (2):133–153. doi:10.1080/1350462970030203.

- Rancière, J. 1999. Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Resenberger, C. 2017. “Was Heißt Hier Nachhaltig Konsumieren?” Praxis Geographie 1:21–28.

- Rogers, P., J. Kazu, and J. Boyd. 2008. An Introduction to Sustainable Development. London: Earthscan.

- Sauvé, L., T. Berryman, and R. Brunelle. 2007. “Three Decades of International Guidelines for Environmental-related Education: A Critical Hermeneutic of the United Nations Discourse.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 12:33–54.

- Singer, M. G. 1986. “The Ideal of a Rational Morality.” Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association 60 (1):15–38. doi:10.2307/3131619.

- Shove, E. 2010. “Beyond the ABC: Climate Change Policy and Theories of Social Change.” Environment and Planning A 42 (6):1273–1285. doi:10.1068/a42282.

- Smyth, J. C. 1995. “Environment and Education: A View of a Changing Scene.” Environmental Education Research 1 (1):3–120. doi:10.1080/1350462950010101.

- Standish, A. 2009. Global Perspectives in the Geography Curriculum: Reviewing the Moral Case for Geography. London: Routledge.

- Stevenson, R. B. 2007. “Schooling and Environmental Education: Contradictions in Purpose and Practice.” Environmental Education Research 13 (2):139–153. doi:10.1080/13504620701295726.

- Sund, L., and J. G. Lysgaard. 2013. “Reclaim “Education” in Environmental and Sustainability Education Research.” Sustainability 5 (4):1598–1616. doi:10.3390/su5041598.

- Sund, L., and J. Öhman. 2011. “Cosmopolitan Perspectives on Education and Sustainable Development—Between Universal Ideals and Particular Values.” Utbildning Och Demokrati 20 (1):13–14.

- Sund, L., and J. Öhman. 2014. “On the Need to Repoliticise Environmental and Sustainability Education: Rethinking the Postpolitical Consensus.” Environmental Education Research 20 (5):639–659. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.833585.

- Swyngedouw, E. 2007. “Impossible ‘Sustainability’ and the Postpolitical Condition.” In The Sustainable Development Paradox: Urban Political Economy in the United States and Europe, edited by R. Krueger and D. Gibbs. London: Guilford Press.

- The Earth Charter. 2000. “Earth Charter Commission.” Retrieved from: http://www.earthcharterinaction.org/content/pages/Read-the-Charter.html. Accessed March 15, 2018.

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2018. “Sustainable Development Goals.” Retrieved from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300. Accessed March 15, 2018.

- Varcher, P. 2011. “L’éducation en vue du développement durable: une filiation à assumer, des défis à affronter.” In L’éducation en vue du développement durable: Sciences sociales et élèves en débats, edited by F. Audigier, N. Fink, N. Freudiger, and Ph. Haeberli,25–46. Cahiers de la Section des sciences de l’éducation no 130. Genève: Université de Genève.

- Vare, P., and W. Scott. 2007. “Learning for a Change: Exploring the Relationship between Education and Sustainable Development.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 1 (2):191–198. doi:10.1177/097340820700100209.

- Wals, A. E. J. 2010. “Between Knowing What Is Right and Knowing That Is It Wrong to Tell Others What Is Right: On Relativism, Uncertainty and Democracy in Environmental and Sustainability Education.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1):143–151. doi:10.1080/13504620903504099.

- Werner, S. (ed). 2017. “TERRA Geographie 7/8.” Berlin/Brandenburg. Stuttgart: Ernst Klett Verlag.

- Weston, A. 1992. “Before Environmental Ethics.” Environmental Ethics 14 (4):321–338. doi:10.5840/enviroethics19921444.

- Whitmarsh, L., S. O’Neill, and I. Lorenzoni. 2011. “Climate Change or Social Change? Debate Within, Amongst, and Beyond Disciplines.” Environment and Planning A 43 (2):258–261. doi:10.1068/a43359.

- Wolff, L.-A., P. Sjöblom, M. Hofman-Bergholm, and I. Palmberg. 2017. “High Performance Education Fails in Sustainability? The Case of Finnish Teacher Education.” Education Sciences 7 (32):1–23. doi:10.3390/educsci7010032.

- Young, I. 2003. “From Guilt to Solidarity: Sweatshops and Political Responsibility.” Dissent 50 (2):39–44.