Abstract

Based on an exploratory case study of a community food waste initiative in Gothenburg, Sweden, this article presents a novel analytical approach to studying the role of learning within sustainability transition niches. The article’s theoretical perspective draws from pragmatist educational philosophy, practice theory, and sustainability transition studies. Proceeding from this theoretical perspective, a two-stage empirical analysis is conducted using dramaturgical analysis and practical epistemology analysis, methods from sociology and the educational sciences. Building on this analysis, the article introduces the concept of educative practices, through which it is argued that a role of learning at the niche level within sustainability transitions is to interrupt the reproduction of norms and attitudes within socio-technical systems. The article thus offers original analytical and conceptual tools for investigating sustainability transitions in relation to learning.

Introduction

The field of sustainability transition (ST) studies explores the processes through which societies can transform in response to persistent sustainability challenges (Grin, Rotmans, and Schot Citation2010). A transition can here be understood as ‘a radical, structural change in a socio-technical or societal subsystem of society’ involving ‘long-term processes that change structures, practices and culture that are deeply anchored in a society’, as well as ‘technology, actors, rules, infrastructures, power relations, patterns of thinking, problem definitions and solutions’ (Paredis Citation2013, 2). A recurring theme in ST studies is learning, where transitions are described in terms of ‘learning by doing’ and ‘doing by learning’, implying a conception of learning as both a vehicle and outcome of transitions (Van Poeck, Östman, and Block Citation2018; van Mierlo and Beers Citation2020; van Mierlo et al. Citation2020).

Learning is seen as important within STs due to the complexity and novelty of the challenges involved, which invites new, creative approaches and solutions (Beers, van Mierlo, and Hoes Citation2016). The importance of learning within STs has also been connected to building ‘societal intelligence’ (Brown et al. Citation2003, 313) and better governance (Loeber et al. Citation2007). However, while there are some good examples of empirical studies investigating learning processes in STs (e.g. Beers, van Mierlo, and Hoes Citation2016; Ingram Citation2018), there is often a lack of conceptual clarity and empirical research supporting descriptions of learning within the ST literature, which has been connected to an insufficient use of learning theories (Van Poeck, Östman, and Block Citation2018). In their editorial of a special issue on ‘learning in transitions’, van Mierlo et al. (Citation2020) argue that learning is often assumed to take place in ST literature, but is neither specified nor critically investigated, presenting a need for theoretical and conceptual work which goes beyond a superficial use of learning theories when describing the role of learning within STs.

Responding to this research gap, this article presents a novel analytical approach to studying the role of learning at the niche level within sustainability transitions. To illustrate our approach, we present a case study of a community food waste initiative in Gothenburg, Sweden. The theoretical perspective we adopt in the article is based on practice theory, which views actors and social structures as reciprocally shaped through reflexively monitored social practices, as well as transactional learning theory, which connects learning to a process of inquiry in which actors adapt their behaviour in response to problematic situations presented by their environment. Our theoretical perspective in the article can be connected to recent literature exploring social learning in natural resource management (NRM) and STs from a practice-oriented perspective (Voß and Bornemann Citation2011; Suškevičs et al. Citation2018). For example, a change in practices and underlying norms is one of the three conditions Reed et al. (Citation2014) identify as being necessary for learning to lead to concerted action in NRM, while Puente-Rodriguez et al. (Citation2015) discuss ‘learning practices’ as a key element to be considered within investigations of STs.

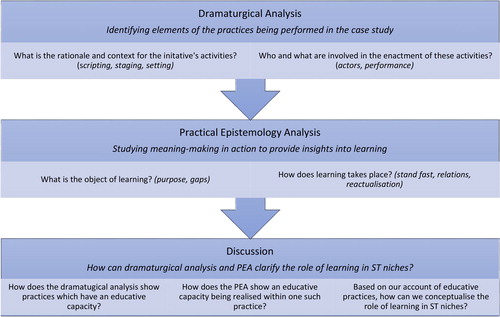

The analytical approach we present in the article consists of two stages. First, dramaturgical analysis, a qualitative method which approaches collective activity in terms of a performance, is conducted to identify elements of practices being performed in the case study, which are treated as potential settings and processes where learning can take shape. Following on from this, practical epistemology analysis (PEA), an analytical method developed alongside the transactional perspective on learning, is employed to investigate whether and how learning takes place within an identified practice. Building upon examples from our analysis, we then develop the concept of ‘educative practices’ in our discussion chapter. Through this conceptual account, we argue that a role of learning in ST niches is to interrupt the reproduction of norms and attitudes within socio-technical systems, challenging and potentially modifying unsustainable regime trends. The research question the article addresses is thus: how can dramaturgical analysis and practical epistemology analysis be used to conceptually and empirically explore the role of learning in ST niches?

Background

Roughly one third of the food produced globally each year, 1.6 billion tonnes, is either lost or wasted, and this figure is projected to increase in the future (Gustavsson et al. Citation2011; Hegnsholt et al. Citation2018). Food waste accounts for eight percent of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, nearly the equivalent of all forms of road transportation combined (FAO Citation2014). Reducing global food waste is therefore seen as an essential pathway to limiting global warming and combating climate change (Hawken Citation2017). While in low-income countries the majority of food waste occurs at the earlier stages of the production cycle, like transportation and storage, waste in high-income countries is primarily attributed to retailers and consumers at the distribution and consumption stages (Hegnsholt et al. Citation2018). Proceeding from a case study in Gothenburg, Sweden, this article’s investigation focuses on the latter context, namely the commercial and domestic drivers of food waste in high-income countries. This context is particularly relevant in Sweden, where the majority of food waste is attributed to households, with an estimated 917,000 tonnes of food waste being generated by Swedish households in 2018 (Naturvårdsverket Citation2020).

It is possible to highlight areas where a reduction in food waste can be seen as contributing towards sustainability in fairly concrete and uncontroversial ways. For example, it is widely accepted that limiting global warming is important to ensure the sustainability of future societies (IPCC Citation2018). We thus take the view that current levels of global food waste are unsustainable due to the quantities of greenhouse gas emissions produced, and the contribution this has to global warming (FAO Citation2014). On this basis, we see reducing food waste as a way of contributing to sustainability. Moreover, with an estimated one in nine people suffering from undernourishment in 2017, reducing food waste can also have an important impact in terms of social sustainability, insofar as more food is made available to those who need it (FAO Citation2018).

Food waste can be described as a ‘wicked problem’: one which evades clear formulations, resists top-down solutions, and is difficult to measure and interpret (Rittel and Webber Citation1973). As well as being enormous in scale, the underlying causes of food waste are manifold and complex, reflecting the many levels from which the problem arises. Supply chains, markets, consumer behaviour and legal frameworks all play an important role, meaning that solutions must be tailored to the specific context and actors involved at various stages (Hegnsholt et al. Citation2018). Moreover, the different stakeholders involved at these stages, i.e. retailers, farmers and consumers, may interpret the problem on the basis of different priorities, making it difficult to build consensus around solutions (Mourad Citation2016). This arguably presents what Maarten Hajer calls an ‘institutional void’, something which arises when established political arrangements fail to produce adequate responses to novel and persistent societal problems (Hajer Citation2003). Hajer argues that such situations invite us to ‘negotiate new institutional rules, develop new norms of appropriate behaviour and devise new conceptions of legitimate political intervention’ (ibid., 176). Drawing from Hajer’s description, this article thus investigates a community food waste initiative as an example of actors responding to an institutional void, and explores the role of learning in the search for novel solutions to wicked sustainability problems.

Theoretical framework

Practice theory and sustainability transitions

A major theoretical approach within ST studies is the multi-level perspective (MLP). This is a framework which studies transition processes by looking at interactions between three conceptual levels: niches, small-scale centres for innovation, regimes, established and stable socio-technical structures, and the landscape, the macro socio-technical context of the regime (Grin, Rotmans, and Schot Citation2010). The MLP explores how dynamic interactions between these levels can influence a regime level transition towards sustainability (Schatzki Citation2011). In view of its more technological orientation, some scholars have argued that the MLP can be complemented using practice theory, which can provide insights into the social dynamics at work within ST processes (McMeekin and Southerton Citation2012; Crivits and Paredis Citation2013; Köhler et al. 2019).

Led by the sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Anthony Giddens, practice theory arose in the 1970s in response to the so-called agency versus structure debate in the social sciences (Corsini et al. Citation2019). This debate concerns whether individual actors or large-scale social phenomena are the primary determinant of human behaviour, and thus the appropriate focus for social analysis (Schatzki Citation2001). Practice theory proposes as an alternative the view that individual actors and social structures are reciprocally shaped at the level of reflexively monitored social practices (Giddens Citation1984). In relation to ST studies, this implies that modifying practices with unsustainable outcomes can establish alternative pathways for action and understanding within socio-technical systems, and potentially influence the structuring rationality of the regime (Schatzki Citation2011). A practice can here be defined as ‘a routinised behaviour that involves interconnected elements of bodily and mental activities, objects or materials and shared competences, knowledge and skills’ (Maller Citation2015, 57).

Andrew McMeekin and Dale Southerton argue that practice theory offers ‘a robust and suitably nuanced set of conceptual tools for advancing understandings of sustainability transitions’ (McMeekin and Southerton Citation2012, 358). Emphasising ‘the recursive relationship between practices as socially ordered entities and as performances’, these authors suggest that when approaching STs using practice theory, we should ‘start by looking at the elements that comprise the practice in question or at the doings that constitute the practice as performance’ (ibid., 357, 358). This dual understanding of practices as both entities and performances draws from Andreas Reckwitz’s influential work on practice theory (Reckwitz Citation2002). Following from McMeekin and Southerton’s recommendation, an approach to studying practices in terms of their constitutive elements and performances is pursued in this article through the methodology of dramaturgical analysis.

Another set of authors, Welch and Yates (Citation2018), describe three forms of social configuration which are relevant to practice theory-based accounts of STs. The first form is bureaucratic organisations whose efficacy and legitimacy is tied to their reproduction of prevailing social practices, implying that a shift in such practices will influence the way these organisations operate. The second form is non-institutional social organisations such as community activist groups, whose shared performances of practices have the potential to generate political influence and legitimacy. The third form the authors describe is uncoordinated networks of actors whose collective participation in practices produce unintended, large-scale outcomes. The authors state that if they become aware of such outcomes, actors within these ‘latent-networks’ can then coordinate to form more deliberately structured groups (ibid.). Proceeding from Welch and Yates’ descriptions, this article’s case study is seen as an example where awareness of the unsustainable outcomes of domestic and commercial food practices has led to an uncoordinated network of actors forming a more deliberately structured group, whose influence and legitimacy is tied to their shared performances of alternative practices.

Transactional learning theory

With his influential book Experience and Education, Dewey (1938a) offered a pioneering contribution on experiential learning which is, we believe, useful for studying ‘learning-by-doing’ and ‘doing-by-learning’ in the context of STs. It has influenced, for example, the experiential learning theory developed by authors such as David Kolb, who presents learning as a process involving ‘concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation’ (Kolb Citation2015, 66). Argyris and Schön (Citation1978) idea of single-loop learning and double-loop learning, often cited in literature on learning in STs, also draws inspiration from Dewey’s work.

Dewey’s account of learning is based on his conception of experience as a transactional process of influence and adaptation, in which individuals act both within and upon an environment (Dewey Citation1928).Footnote1 Learning takes place when individuals reflect on their experiences in order to shape future actions: ‘To ‘learn from experience’ is to make a backward and forward connection between what we do to things and what we enjoy or suffer from things in consequence’ (Dewey Citation2004, 152). Dewey’s pragmatist work gave rise to a transactional learning theory (Östman, Van Poeck, and Öhman Citation2019), which understands learning as being incited by a ‘problematic situation’ in which our habitual ways of acting and coordinating with our surroundings are disturbed.

Transactional learning theory is grounded in the pragmatist assumption that in everyday life we mainly act habitually, without reflecting. Reflection first starts when our environment disturbs our habits. If the disturbance cannot be overcome immediately with the help of existing habits, we cannot just ‘move on’. Overcoming the disturbance requires an ‘inquiry’. Through experimentation we try to solve the problematic situation, which results, if successful, in new knowledge, skills, values, identities, etc. This can result in a substantial transformation of habits or even the formation of new habits (ibid.). Learning can thus be said to have happened if an inquiry enables us to proceed (see further below).

Dewey’s framing of ‘problematic situations’ may seem to prejudge a disruption of habits as something negative. Authors such as Luntley (Citation2016, 9) have therefore suggested that we understand this as ‘a simple sense of disruption’ whose ‘unsettling character is independent of how we respond to it and begin to treat it’. Indeed, our routine ways of acting can be disturbed by a crisis or problem that renders our existing habits untenable but also, as Dewey (Citation1934) argues, by an imaginative experience of possibilities which contrast with actual conditions but might be realised.

Drawing from Dewey, transactional learning theory investigates people’s learning in ‘transaction’ with their surroundings. This aligns well with practice theory, which views individual actors and social structures as being reciprocally shaped. As Dewey (Citation1922, 43) phrases it: ‘To a considerable extent customs, or widespread uniformities of habit, exist because individuals face the same situation and react in like fashion. But to a larger extent customs persist because individuals form their personal habits under conditions set by prior customs’. Hence, a pragmatist perspective on human action emphasises that people, through their actions, constantly try to coordinate with the surrounding world in order to achieve goals or adapt to changes in their environment and, in doing so, also change their environment. A pragmatist transactional approach thus understands learning as a process in which individuals and their environment transform reciprocally and simultaneously through engagement with problematic situations. The interplay – or, in Dewey and Bentley (Citation1949) term, ‘transaction’ – between humans and the surrounding social/physical world is here seen as the engine for learning.

Dewey’s transactional view of learning is closely connected to his ideas of language. For Dewey, communicating through language extends experiential learning to become a collaborative process: language is ‘an active means for the coordination of common behaviour’, facilitating ‘the establishment of cooperation in an activity in which there are partners, and in which the activity of each is modified and regulated by partnership’ (Dewey Citation1929, 179; Dreon Citation2017, 4). Dewey thus sees language as an essential part of the transactional activity which produces learning: individuals are ‘defined by the linguistic and practical behaviour by means of which they respond to the situations they are continuously faced with’ (Dewey Citation1929, 7). In this account, Dewey conceives of linguistic meanings as ‘signifying or evidential powers’ which arise when individuals communicate and coordinate their experiences, and thus understands meaning as being shaped by the social and practical context in which language is used (Dewey Citation1929, Citation1938b, 56).

Similarly to Dewey, the later philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein conceives of linguistic meanings as inseparable from the practical use of language in everyday situations. The different practical contexts in which linguistic meanings are constructed, Wittgenstein terms ‘language-games’ (Wittgenstein Citation1958). In this account, Wittgenstein takes the ‘first-person’ view that individuals’ mental processes are reflected within their linguistic expressions: ‘language is itself the vehicle of thought’ (Wittgenstein Citation1958, §329). Dewey similarly writes that language ‘“expresses” thought as a pipe conducts water’ (Dewey Citation1929, 169). This first person perspective on language is adopted within the transactional perspective on learning, which proposes that studying language use can provide insights into the educative process through which individuals coordinate their experiences in response to a problematic situation presented by their environment (Östman and Öhman Citation2010). As elaborated below, this is an important part of our methodology in practical epistemology analysis (PEA).

Methodology

In order to investigate the role of learning within ST niches, a qualitative case study method was chosen to provide a broad empirical perspective on a contemporary phenomenon through the combination of multiple data sources (Yin Citation1984). A practical consideration when selecting a case was that there was enough activity and openness among the individuals involved to provide sufficient data for analysis. The Solidarity Fridge (Solidariskt Kylskåp), or Solikyl, an ST niche initiative which we describe in the following section, appeared as an appropriate candidate in view of these criteria. Based on the time and resources available, the empirical boundary for the case was limited to the internal activity of Solikyl, and did not extend to the restaurants and supermarkets with which they collaborate. While a more extensive empirical exploration of the role of learning in ST niches would benefit from a larger case study involving a longitudinal analysis and a broader range of stakeholders, we nonetheless feel that as an exploratory study our case provides a sufficient basis for presenting the application of our analytical approach.

One unstructured and two semi-structured interviews were conducted with Solikyl members with a total recorded length of two hours and forty-one minutes. Interviewees were selected based on their level of activity within the initiative. Two interviewees were members of the Solikyl board, who had been highly active within the initiative from its outset. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with these persons with the intention of highlighting the overarching goals of the Solikyl initiative and the thought processes behind its activities and organisational structure. The third interview was with a Solikyl volunteer who was also highly active within the initiative, but less directly involved with its management and organisation. An unstructured interview format was used here to provide a more conversational atmosphere in which to learn about this person’s involvement with the initiative. All interviews were recorded digitally and manually transcribed into text documents. Consent forms detailing conditions for participation and data use policies were signed by all interviewees.

Additionally, three participant observations took place across two different Solikyl fridge venues, each lasting for their opening duration of two hours. These involved helping with the operation of the fridges by sorting and storing food items, as well as interacting in brief verbal exchanges with visitors and volunteers. The intention here was to develop a practical understanding of how the fridges are operated, and how the volunteers carry out their roles within the organisation. Direct observation was subsequently conducted during a Solikyl board meeting, which was again digitally recorded, manually transcribed and translated from Swedish into English. Consent was granted by all participants at the meeting with an understanding that they would remain anonymous in all published materials. Supplementary document analysis was also applied to physical and digital materials published by Solikyl such as pamphlets, blog posts, and forum discussions.

In order to identify the elements which comprise the practices being performed within the Solikyl case study, and the potential settings and processes where learning can take shape, we applied dramaturgical analysis to the collected case data. Dramaturgical analysis is a method which seeks to understand collective activity in terms of a performance, and concerns itself with how the performative elements of an organised activity provide insights into the meaning it is given by participants (Feldman Citation1995). In line with pragmatism and practice theory, dramaturgical analysis thus operates on the idea that ‘meaning is produced in action’ (ibid., 41). The operational concepts used in this article’s dramaturgical analysis were scripting, staging, setting, actors and performance. The analytical procedure used was to apply these operational concepts as guides to extract relevant data from our case study and represent this within an interpretative model, from which we could identify elements of practices and potential settings for learning.

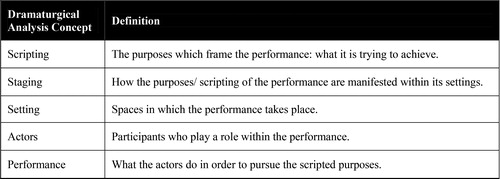

In dramaturgical analysis, ‘scripting’ describes the framing of a performance in terms of purposes: what it is that the performance seeks to achieve. ‘Staging’ then refers to the way these purposes are manifested in the setting of the performance, where setting refers to the spaces in which performance takes place. ‘Actors’ are described in terms of their roles and motivations for performance, and finally, ‘performance’ is described in terms of what these actors do across various settings to pursue the scripted purposes of the collective activity (ibid.). A summary of these operational concepts is included in the table below ().

For an in-depth analysis of learning processes within the studied initiative, we employed practical epistemology analysis (PEA), an analytical method which proceeds from a first-person perspective on language as representing experience and meaning (Wickman and Östman Citation2002). This is a method for in situ analysis aimed at opening-up the black-box of how meaning is made ‘in action’Footnote2. PEA aligns with the above elaborated transactional learning theory, as it explores learning as a process whereby individuals collectively form responses to a problematic situation they are facing. In this sense, something ‘is learnt when the activity moves on, that is when there is evidence that the participants can proceed towards a purpose’ (Ligozat, Wickman, and Hamza Citation2011). While the object of PEA can vary (Maivorsdotter and Wickman Citation2011; Maivorsdotter and Quennerstedt Citation2012, Citation2019; Andersson Citation2019), verbal exchanges taking place in real-life situations are the most common empirical focus (Wickman and Östman Citation2001). In this article, PEA was thus applied to a discussion taking place during a Solikyl board meeting.

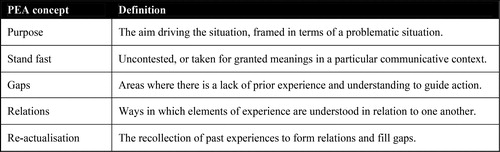

Five operational concepts are used in PEA: purpose, stand-fast, gaps, relations, and re-actualisation (). Purpose describes the overall aim which is driving the situation, framed in terms of a problematic situation which the participants are trying to overcome (Wickman Citation2012). ‘Stand fast’ refers to meanings which are uncontested, or taken for granted within a particular communicative context (Wickman and Östman Citation2001). It is not assumed that what stands fast is necessarily unambiguous, but rather that, based on their shared experience, there is enough common understanding among participants that such things do not require further explanation. ‘Gaps’ refer to areas where there is a lack of prior experience and understanding to guide action in response to the problematic situation. Gaps become visible in the form of, for example, hesitations, questions or disagreement, and reflect what does not stand fast within a verbal exchange and therefore requires further knowledge and meaning-making (ibid.). Gaps are closely related to the purpose of learning, as it is by filling gaps that participants form new experiences and understanding in response to a problematic situation (Maivorsdotter and Quennerstedt Citation2019).

‘Relations’ in PEA refer to the way in which elements of experience are understood in reference to one another (Wickman and Östman Citation2001). Something stands fast in a discussion when there are sufficient relations across participants’ shared experience to establish a common understanding, and conversely, gaps appear when participants’ existing experience is insufficient to establish such understanding. One way in which participants form new relations is through a process termed ‘re-actualisation’, in which past experiences are recalled in order to fill gaps and establish meaningful pathways for action (Rudsberg, Öhman, and Östman Citation2013).

Participants in a learning process thus create relations between what stands fast for them (earlier acquired knowledge, skills, values, etc.) and the new situation they are encountering in order to establish new ways of understanding and interacting with the environment. A crucial outcome of PEA is therefore identifying the relations construed by participants to resolve gaps and respond to the problematic situation. By identifying gaps that become visible and analysing whether and how these gaps are filled, PEA offers an empirical account of whether, how and what people are learning (Wickman and Östman Citation2001).

Below is a schema illustrating the stages of our analysis, clarifying what is being analysed at each stage, which operational concepts are being used, and how this informs the questions we explore in our discussion ().

Results and analysis

The Solidarity Fridge (Solidariskt Kylskåp), or Solikyl, is a community food waste initiative in Gothenburg, Sweden which has been active since May 2016 (personal communication A February 17, 2019). The initiative, which is a registered non-profit organisation, currently has 121 active members registered on its online platform (personal communication September 8, 2020, Karrot Citation2020). Solikyl coordinates a network of volunteers carrying out regular pick-ups of unwanted food items from partners across the city, primarily restaurants and supermarkets, of which there are currently seventeen (personal communication September 8, 2020). The food is then transported to one of nine fridges across different areas of Gothenburg which are open to the public at regular hours, several times a week, during which people can either collect or donate food (Solikyl Citation2020).

To coordinate their activities, Solikyl make use of an open source online platform called Karrot. This platform was designed to facilitate community sustainability initiatives, giving them full control over their rules and procedures as well as access to a large network of similar groups on the platform (Foodsaving Worldwide Citation2016). As part of an international network of similar foodsharing initiatives, Solikyl also represents a wider movement which is collectively challenging unsustainable food system trends at a much larger scale (Collective Green Citation2020). The Solikyl case thus provides the empirical basis for this article’s exploration of the role of learning in ST niches. In first part of the analysis that follows, attention is paid to how dramaturgical elements represent the practices being performed in the Solikyl case study, and how this highlights potential settings and processes where learning can take shape. Following from this, we use PEA to further investigate one such setting and process, and explore how meaning making and learning are formed in response to a problematic situation.

Dramaturgical analysis

Scripting

The scripting of Solikyl’s performance has been interpreted from interviews with the organisations’ active members, as well as online materials such as blog posts. From these sources, two main motivations appear as scripts for Solikyl’s performance as an organisation. As stated on their website, Solikyl’s primary goal is to reduce domestic and commercial food waste in Gothenburg, by targeting the waste of households, restaurants and supermarkets (Solikyl Citation2018). The practical steps for achieving this are to ‘spread solidarity fridges across the city’ and ‘to get more food shops to cooperate’ (Foodsaving-Today Citation2017b). The first script for Solikyl’s performance is thus to reduce food waste in Gothenburg by changing domestic and commercial behaviour, and by expanding their operations.

The second script for Solikyl’s performance is the broader and more ideological goal of providing a model for self-organising community initiatives which respond to sustainability problems. This aspect of Solikyl’s scripting was conveyed during an interview with a Solikyl member:

it’s about showing a way for people to organise in community projects: self-organising… People should empower themselves and take the lead. Organise on a more horizontal basis… it’s the only task worth pursuing to solve some really big problems of the way we live which is unsustainable. (personal communication A February 17, 2019)

As well as the model pioneered by the German website foodsharing.de (Rombach and Bitsch Citation2015), the community organising aspect of Solikyl is influenced by Elinor Ostrom (personal communication A February 17, 2019), the Nobel-prize winning economist who developed principles for governing common pool resources (CPR) without centralized authority or privatisation (Ostrom Citation1990). Ostrom’s principles, for example that ‘when CPR appropriators design their own operational rules… using graduated sanctions… the commitment and monitoring problem are solved in an interrelated manner’ (Ostrom Citation1990, 99) can thus be traced within Solikyl’s scripting: ‘You should have a community… and you should also have penalties and sanctions which are proportional’ (personal communication A February 17, 2019).

Another influence on Solikyl’s community-organising scripting is the perception that institutional responses to food waste have been inadequate. One member suggested that institutions were inefficient in their responses due to bureaucratic constraints:

government, schools, the private sector, non-profits are already trying to do the same thing basically. They have the resources, they have the knowledge. But we don’t want to use the old models… the bureaucracy around it is so enormous … you start thinking do I want to contribute to this system or do I want to be part of this new way of solving problems? (personal communication B February 17, 2019)

A similar aversion to institutional bureaucracy was expressed by another Solikyl member, who while discussing the prospect of a partnership with an educational non-profit expressed concern that the Solikyl initiative would ‘stop existing when nobody continues because it’s built around these structures’ (personal communication C February 16, 2019).

This component of Solikyl’s community-organising scripting is mirrored by their goal of highlighting the potential for organising outside of traditional institutional structures:

projects of community organising, I think they are more effective because they are closer to the ground, closer to people, and people stop becoming passive consumers and they become active agents of change, of problem solving (personal communication A February 17, 2019).

A related benefit of community organising which was introduced is that this creates fewer barriers for participation:

you have a lot of other groups of people who don’t find it so easy to enter into this association or group of people. And we think this way of doing it, the decentralized, non-bureaucratic, more open way, can invite those other groups (personal communication B February 17, 2019).

Solikyl is thus scripted as having an organisational structure which is less hierarchical and more accessible than established institutional models, and this is seen as an important part of the initiative’s ability to mobilise community members as ‘active agents of change, of problem solving’.

Setting & staging

The main physical setting for Solikyl’s performance is the organisation’s nine fridge venues. Fridges are located across a range of locations covering different neighbourhoods in Gothenburg. The venues for fridges are generally public facilities, for example two are based in community-run bicycle workshops and one is in a community centre, while previous venues have included a public library (Foodsaving-Today Citation2017a, Solikyl Citation2020).

The staging of the fridge venues in relation to the organisation’s scripting is conveyed on the Solikyl website:

An open fridge or pantry is a point of redistribution, where food from individuals or a grocery store can be stored… These redistribution points are open to the public, to anyone who wants to either leave or take food from it, with no money or reciprocity required. (Solikyl Citation2018)

As well as facilitating the storage and distribution of food, the fridges are thus also staged to reflect Solikyl’s scripting as open, non-hierarchical and self-organising:

There is no need for constant supervision of the fridge by any kind of formal organisation… There is no need either for a boss, whether from a company or from a non-profit, to organise or dictate how these interactions are going to take place. (Foodsaving-Today Citation2017b)

Another important setting for Solikyl’s performance is its board meetings, which generally take place at one of the fridge venues. As spaces for deliberating on the operations and goals of the organisation, these settings are staged to reflect the script of promoting active engagement and self-organisation within the project: ‘so that you’re also making decisions about it together with the other people’ (personal communication A February 17, 2019). The more informal setting of weekly ‘hangouts’, where meals are prepared with leftover food from the fridges, are then staged ‘To create relationships. To create some social capital.’, reflecting the script of being community driven (ibid.).

The digital platforms of Karrot and the Solikyl Forum provide a different kind of setting in which Solikyl’s performance takes place. The way these settings are staged in relation to the scripting of the organisation is indicated in a blog post:

I’ve always been very enthusiastic about the level and scale of organisation that networks, with no formal hierarchies, can achieve by using digital platforms. It is especially important that this can happen without a for-profit company controlling the platform and setting the framework of how people can interact (Foodsaving-Today Citation2017c).

Thus, the staging of Solikyl’s digital settings as deliberately outside of mainstream web-platforms connects with the script of engaging people more directly and promoting their sense of agency, by avoiding the hierarchies and biases associated with institutional structures.

Actors

Across its various settings, a number of actors are involved in Solikyl’s performance as an organisation. One set of actors are the fridge’s recipients, a group which during participant observation was made up of local residents, who were diverse in terms of their age, gender and ethnicity. A Solikyl pamphlet mentions the diversity among its fridges’ users, which includes students, pensioners and immigrants (Solikyl 2019a). The next set of actors are the volunteers, or ‘foodsavers’, who are responsible for collecting food from Solikyl’s partners and transporting it to the fridges (Solikyl 2019b). An important practical aspect of the foodsaver’s role is ensuring that all collected food passes a quality inspection and can be deemed safe for distribution and consumption (Solikyl 2019b). An interviewee suggested that these actors may have personal concerns about the issue of food waste, as well as broader environmental or altruistic motivations for their participation (personal communication A February 17, 2019).

Another set of actors are the Solikyl ambassadors, who play a more strategic role within the organisation (Solikyl 2019b). The ambassador’s role is to gain new partnerships and venues for fridges in order to expand the operations of the organisation. As public representatives, the ambassadors are also tasked with building a positive reputation for Solikyl within the city. In the ‘Guide for new ambassadors’ provided by Solikyl, requirements for becoming an ambassador are set out, for example that you must attend a board meeting, register on the online forum, and complete an eligibility test, including questions on organisational routines, food security policies, and the legal obligations of partners (Solikyl Citation2019c).

The final set of actors within Solikyl are the board members, who are responsible for managing the strategic direction of the organisation and facilitating the creation of new local groups in different areas of Gothenburg. The board members are also tasked with ensuring that volunteers are properly equipped to fulfil their roles, as well as intervening in any disputes that may arise (Forum-Solikyl Citation2019). A variety of perspectives are represented among these actors, which means that another part of the board members’ role is to deliberate with one another, as well as the other volunteers, in order to build consensus around decisions which are taken within the organisation (personal communication A February 17, 2019).

Performance

Solikyl’s performance is the practical sum of what these actors do across various settings to realise the scripting of the organisation, and represents the practices which are performed within the initiative. Central to Solikyl’s performance is the activity of ‘foodsaving’, which involves partners making food available for collection, volunteers collecting, transporting and storing the food, and making sure that it is safe for consumption, and recipients finally collecting and consuming the food. Foodsaving thereby realises the scripted motivations of reducing food waste in Gothenburg, as well as that of utilising an independent digital platform. Another aspect of Solikyl’s performance is ambassadors gaining new partnerships, which corresponds to the script of changing commercial and domestic behaviour in Gothenburg and allowing greater quantities of food to be saved (Solikyl 2019b). A further part of Solikyl’s performance is the board meetings and forum discussions, where strategies for the organisation are deliberated upon and problems are addressed, as well as the weekly hangouts, which allow new members to get to know the group and provide a forum to share and discuss ideas about the organisation (personal communication A February 17, 2019). These aspects of Solikyl’s performance reflect its scripting as being community-driven and built around active participation and engagement among its members.

This analysis can now guide a more in-depth investigation into the role of learning within Solikyl’s activities as a ST niche initiative. While the scripting-analysis sheds light on the purposes in relation to which learning processes can be investigated, the staging-analysis reveals the settings where learning processes can potentially take shape. The identification of actors then shows who can be involved in such learning processes, and finally the performance-analysis reveals the specific activities, or practices, in which learning can be investigated.

Practical epistemology analysis

Through PEA we now provide an situ analysis of how learning takes shape in one of the activities identified in the performance-analysis of the previous section. This subsequently allows us to illustrate our conceptual account of educative practices in relation to a role of learning within ST niches. The empirical object of our PEA is a discussion taking place during a Solikyl board meeting, the focus of which is whether the organisation should continue to structure itself as an association (a more detailed version of this analysis, including the conversation line by line, is included in table form in Supplementary material Appendix A). In the context of the discussion, the term ‘association’, translated from the Swedish ‘förening’, can be read as referring to a formalised decision making structure, here represented by the Solikyl board, and official designations for who is considered a ‘member’ of the organisation and can thus claim to represent and act on behalf of it. An alternative to the association in this context might be a deregulated network where participants are free to act on behalf of Solikyl without any formal restrictions or requirements.

The discussion reveals uncertainty and a lack of consensus as to whether an association structure should be continued within the organisation. Some insight as to why this issue was being discussed was provided during interviews. In particular, there had been a recent incident in which some volunteers acted in violation of the organisation’s guidelines, creating difficulties for other members of the group:

things really started not working… they were really failing to do their jobs… and not bringing the food to the fridge, they were collecting a lot for themselves on the spot. (personal communication A February 17, 2019)

Another interviewee brought up the same incident, describing the questions it raised with regards to the rules for participation and membership in the organisation:

We’re discussing it. I think most of us do have the opinion that we want to have it as open as possible, but maybe some see that we have to have some rules. (personal communication C February 16, 2019)

This incident can be seen as having disturbed Solikyl’s habitual ways of dealing with organisational structures and rules, giving rise to an inquiry. During the board meeting discussion, several gaps: instances where there is a lack of experience and knowledge to guide action, are revealed with regards to the situation. The first gap which emerges in the discussion (Supplementary material Appendix A, line 1) concerns how membership is defined within the organisation, and whether this should be a requirement for participation:

A: - I thought it would be great if we could discuss a little bit…, if we want ‘members’… I am thinking more whether it should be a requirement…

As the participants are unable to come up with clear answers through construing relations with what already stands fast for them (lines 2-7), we can say that this gap lingers and requires further inquiry. Participant E further specifies this initial gap (line 8) and reformulates the question in terms of whether Solikyl should continue to structure itself as an association:

E: - I think the question is whether or not we choose to be an association. Should we continue with that form or not? … do we want this structure and why? Is there, is there any reason left to have this organisational structure?

Participant E here relates the discussion about the lingering gap to something that is uncontested and thus appears to stand fast for the participants: what is meant by ‘an association’ and ‘Solikyl’s project’. This establishes the purpose within the discussion of responding to the uncertainty and lack of consensus on Solikyl’s organisational structure.

Over the course of the discussion, participants form relations in order to respond to the uncertainty surrounding the association structure. A number of these relations connect the association with instrumental benefits such as more easily gaining new partnerships. One such relation is introduced by Participant A early on in the discussion (line 1):

A: - if we can be considered more as an association, it might be easier to present ourselves to other organisations or secure funding. They want to see that it has worked, that it has participating members and so on.

Participant E restates this relation when discussing Solikyl’s original motives for forming an association, again connecting this to their ability to gain collaborations (line 8): ‘we were forced to have the organisational structure to formalise, professionalise and be able to get to a lot of collaborations’. For Participant E, this relation thus appears to involve the reactualised experience of an external pressure on Solikyl to organise themselves in a certain way. Participant B also forms this relation, again citing external institutional factors (line 9): ‘we have used this form as needed because we live in a world where things need to be formalised’. The relation between Solikyl’s association structure and its ability to more easily operate in its institutional surroundings thus appears to stand fast for the participants.

Another relation which is construed in the discussion, is between the association structure and Solikyl’s capacity to authoritatively resolve internal conflicts and allow members to voice their concerns:

B: - The organisation must be formalised, and then we can take this opportunity when there is, as might be, a conflict, or someone must have some sort of authority that must make a decision formally. And then there is a forum there, which is where you can gather and can have a voice.

Participant B thus relates the association with the cohesion and management of the organisation (line 9), responding to the gap as to whether this structure is beneficial (line 8).

Another set of relations concern the drawbacks of having a formalised association structure. Underpinning these is a stand fast relation between the organisation’s continuation and the work of members who are driven and motivated. Participant E introduces this by saying that ‘there must be people who drive the association on’ (line 10), and Participant B similarly states that ‘for an association to have any meaning you need some members who are very, very driven’ (line 13). Subsequent relations dealing with the drawbacks of the association structure thus connect back to the importance of having engaged members to drive the organisation forward.

Early on in the discussion, addressing the gap as to whether membership should be a requirement for participating in the initiative, Participant C suggests that this may deter people from becoming involved, citing experiences with prospective volunteers (line 2): ‘I have gotten the impression that there were quite a few who do not want to be registered, who want it to be a bit different.’ Later, Participant E then relates the bureaucracy of a formalised association structure with a loss of momentum within the project, which is conveyed through a stark metaphor (line 10): ‘should you drag the whole corpse along with you all the time? Or should you let the corpse die out?… Do you kill the corpse or let it kill you?’. These participants thus relate the formalised and bureaucratic elements of the association with a loss of enthusiasm and momentum within the project, which threatens the engaged participation it depends upon.

Over the course of the discussion, two examples appear which show how relations allow participants to form practical responses to the problematic situation at hand. The first such relation is formed by Participant E, and connects the digital platform, Karrot, with the managerial role that the association currently fulfils (line 12):

E: - the way I see it, using Karrot as an organisational hub may be able to fill all these functions, so you no longer have a need for an association, or it can have a smaller role.

This relation thus addresses the gap as to whether there are preferable alternatives to the existing association structure, and in doing so offers a pathway for acting in response to the problematic situation.

The second relation which introduces a new practical response is formed by Participant A, and connects the idea of a more open association structure with the engaged participation seen as necessary for maintaining the organisation’s momentum (line 14):

A: - one can imagine a larger board where one finds some volunteers. So that then maybe even people who are not so active, maybe I, can become part of the board also if they are interested… If some of the ordinary members at the meetings are not active anymore, then another person can inherit their right to vote.

This relation thus responds to the gap as to whether the association could be structured differently, and links back to earlier relations in the discussion: ‘there must be people who drive the association on’; ‘there were quite a few… who want it to be a bit different’. In proposing to give volunteers the opportunity to have a more active role in the association, and relating this to the need for engaged participation, Participant A thus establishes a new practical response to the problematic situation at hand.

This analysis can now be connected back to the elements of Solikyl’s performance identified in the dramaturgical analysis, allowing us to illustrate our conceptual account of a role of learning within ST niches in terms of educative practices.

Discussion

From our analysis, three examples form the basis for our concept of educative practices. These are the practices (or constellations of practices) of foodsaving, ambassadors gaining partnerships, and deliberation in the context of community organising. While the dramaturgical analysis allows us to identify the elements which constitute these practices and their educative capacities, conceived as a potential for learning to take place, the PEA provides us with an empirical example of how an educative capacity is realised within an identified practice. Thus, by describing the educative capacity of Solikyl’s practices, and illustrating how this is manifested within an empirical example, we elaborate our conceptual account of a role of learning in ST niches.

The educative practice we describe can be seen as alternatives to the ‘regime practices’ which constitute the status quo within Gothenburg’s food system, such as consumers taking a passive role in the food supply chain, and retailers disposing of food which is deemed commercially inviable (Crivits and Paredis Citation2013). In practice theory terms, the prevailing attitudes and norms of the regime can be said to normalise such practices, while their performance in turn reproduces the structuring rationality of the regime. Through our conceptual account, we argue that a role of learning in ST niches is to interrupt this reproduction of norms and attitudes, establishing new pathways for action and understanding, and reflexively challenging the structuring rationality of the regime. As examples of ‘learning by doing’, educative practices thereby enable niche-actors within STs to ‘negotiate new institutional rules, develop new norms of appropriate behaviour and devise new conceptions of legitimate political intervention’ (Hajer Citation2003, 176). In pragmatist terms, this can be said to reflect an engagement with a problematic situation which is produced by habitual ways of thinking and acting, instigating the learning process of modifying and potentially replacing these habits.

The first example of a practice which has an educative capacity we draw from the Solikyl case study is foodsaving. The actors involved in this practice are foodsavers, partners and fridge recipients, while the routinised activities which constitute this practice are partners making food waste available, volunteers coordinating the collection of the food and ensuring it is safe for consumption, and recipients finally collecting and consuming the food. This practice is thus performed by multiple actors across different settings, and may be viewed as a constellation of practices insofar as each actor carries out a different activity within its performance. Foodsaving can be seen as contrasting with established regime practices such as commercial actors disposing of food considered commercially inviable, and consumers limiting the food they consume to what is commercially available to them.

An educative capacity for the practice of foodsaving is suggested in the scripting section of the dramaturgical analysis. For instance, the scripted motivation to change commercial and domestic behaviours around food waste can be seen as having the potential to interrupt habitual ways of thinking and acting represented in the aforementioned regime practices. Through its performance, foodsaving thus highlights an alternative way of thinking and acting towards food waste, which departs from established norms and behaviours in the pursuit of more sustainable outcomes. This break with commercial and institutional norms is conveyed in the staging of the fridge venues, where there is ‘no money or reciprocity required’, and no need for ‘constant supervision of the fridge by any kind of formal organisation’. The educative capacity of foodsaving also relates to showing the potential of independent digital platforms in facilitating such activities: ‘without a for profit company controlling the platform and setting the framework of how people can interact.’ Thus, it is in drawing attention to new models of action and understanding for responding to sustainability problems that we can see an educative capacity in the practice of foodsaving.

The second example of a practice which has an educative capacity we draw from the case study is ambassadors attempting to gain new partnerships. This practice forms part of another constellation of practices which may collectively be described as strategic-communication (and also encompasses practices such as distributing information through pamphlets and blog posts). The actors involved here are the ambassadors and the potential collaborators they are interacting with, while the activities involved in the practice are communicative: ‘communicating, arguing or even nagging and being stubborn when necessary’. The outcomes which are pursued in ambassadors attempting to gain partnerships correspond with the scripted motivation to ‘spread solidarity fridges across the city’ and ‘get more food shops to cooperate’. Here, the equivalent regime practices may again be seen as consumers assuming a passive role in the food supply chain, and retailers disposing of food deemed commercially inviable, but more significant in this example is the direction of influence between consumers and retailers which is normalised within such practices.

Conceived as an interruption which has the potential to modify habitual ways of thinking and acting, the educative capacity we see in ambassadors gaining partnerships is twofold. In the first instance, this can be related to the scripted purpose of changing community members’ perception of themselves, from ‘passive consumers’ to ‘active agents of change’. The second aspect of this practice’s educative capacity is demonstrating to potential partners the possibility of an alternative way of dealing with food waste, which departs from commercial norms but may contribute to more sustainable outcomes. Thus, in community actors pursuing a more active role in determining how food systems operate, and commercial actors potentially modifying the way they handle food waste, we see a challenge towards and a potential to modify unsustainable regime practices within Gothenburg’s food system.

The final example of a practice with an educative capacity we draw from the Solikyl case study is deliberation, which belongs to a larger constellation of practices making up Solikyl’s community organising activities. While board meetings and the Solikyl forum provide the setting in which the practice of deliberation takes place, the performance-analysis reveals the activities and outcomes of this practice, such as making strategic decisions and addressing concerns within the organisation. The educative capacity of deliberation, and of community organising more broadly, can be connected to the script of inviting community members to ‘empower themselves and take the lead’. As with previous practices, an important aspect of this educative capacity is demonstrating that communities have the power to generate responses to sustainability problems where institutional actors have fallen short: to ‘be part of this new way of solving problems’. This can also be related to broadening the scope of community members who see themselves as being able to participate in such activities, showing that it is not only those ‘who already have a job, are already well educated’ who can contribute. Within the practice of deliberation, by demonstrating that community actors can generate their own models for responding to sustainability problems, we thus see an educative capacity to interrupt norms and attitudes surrounding institutional responses to such problems.

The PEA provides us with an empirical example of how the educative capacity of deliberation is realised within a specific learning process. In the board meeting discussion, we see actors coordinating their experiences of their institutional surroundings and the organisational structures they have created for themselves, using language to open up pathways for responding to a problematic situation in this environment. The PEA thus empirically clarifies how, through an educative practice, structural norms, i.e. the institutional demands placed on community organisations to be seen as legitimate, can be reflexively engaged with to devise new models for responding to sustainability problems. We find support here for our view that educative practices at the niche level have the capacity to generate new ways of thinking and acting in response to sustainability problems. The PEA thus reinforces our conception of a role of learning in ST niches as being to interrupt the reproduction of norms and attitudes within socio-technical systems, challenging and potentially modifying the structuring rationality of the regime.

Conclusion

In order to explore the role of learning in ST niches, this article presented a novel analytical approach combining dramaturgical analysis and PEA, which was applied to a qualitative case study of the Solikyl initiative. In the discussion, examples were drawn from this analysis to illustrate the concept of educative practices, and argue that a role of learning in ST niches is to challenge and potentially modify unsustainable regime trends within socio-technical systems. The article thus demonstrated how dramaturgical analysis and practical epistemology analysis can be applied to conceptually and empirically explore the role of learning in ST niches. By using dramaturgical analysis to identify elements of practices and their performances within a qualitative case study, and applying PEA to provide an in-situ analysis of learning within an identified practice, the article offers an original analytical approach to the growing body of literature investigating STs in relation to learning. Through its combined theoretical perspective, which draws attention to areas of compatibility between pragmatism and practice theory, the article also highlights the potential for a constructive dialogue between these traditions, which future research could develop further.

Nonetheless, there are a number of limitations to consider surrounding this article’s exploration of the role of learning in ST niches. For one, the empirical scope of the case study is narrow in that it represents only one type of stakeholder within Gothenburg’s food system. As mentioned previously, food systems involve a wide-range of stakeholders, meaning that significant change requires a shift in actors across a range of sectors. Thus, by focusing only on the members of Solikyl, and not investigating fridge recipients, collaborating partners, municipal employees etc., our account of educative practices becomes specific to a certain type of actor, namely community activists. It may well be the case that ‘learning by doing’ takes on a different shape within different organisational and institutional contexts. Thus, a larger sample size which enabled a comparison between stakeholders could clarify the extent to which our account is specific to a certain type of actor within STs. It is also worth noting that Solikyl represents only one among many diverse examples of ST niche initiatives, as well as a limited socio-cultural context. Another way in which our exploration of the role of learning in STs could be developed would therefore be to study the influence of contextual factors, such as political, cultural and economic conditions upon the development of ST niche practices.

Another limitation to consider is the temporal scope of our study, which reflects only one point in time within the studied initiative. In our discussion of educative practices we have thus only described a potential to modify habitual ways of thinking and acting, and further empirical analyses would be needed to establish whether these capacities are in fact realised. Similarly, the learning events we describe through PEA mark the starting point of an inquiry which is not fully realised until participants pursue the courses of action they establish, and observe whether these do in fact resolve the problems they are responding to. In this sense, our study reflects just one stage in the process of experiential learning. Insight into whether/how the organisational routines of the Solikyl initiative evolved in response to the disturbance described in the PEA could thus have strengthened our account of educative practices, as could additional in-situ analyses of learning events across different practices. In future studies adopting a similar methodological strategy, the use of a longitudinal study design allowing for a follow up on learning outcomes, as well as a broader empirical scope including in-situ analyses of a range of practices, could thus provide more substantive empirical insights into the role of learning within ST niches.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For an in-depth discussion of ‘Deweyan Transactionalism in Education’, we refer to Garrison et al. 2021 (forthcoming).

2 As such, PEA differs strongly from research methods based on, for example, a pre-test to assess people’s prior knowledge and a post-test to determine what they have learned. Instead, as will become clear below, what was already known and what has been learned is integrally part of the methodology itself, which takes into account what ‘stands fast’ and analyses whether or not gaps are bridged so that the participants can proceed.

References

- Andersson, P. 2019. Transaktionella Analyser av Undervisning Och lärande - SMED-Studier 2006–2018 [Transactional Analyses of Teaching and Learning – SMED-Studies 2006–2018]. Rapporter i Pedagogik 22. Örebro: Örebro University.

- Argyris, C., and D. A. Schön. 1978. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Beers, P. J., B. van Mierlo, and A. C. Hoes. 2016. “Toward an Integrative Perspective on Social Learning in System Innovation Initiatives.” Ecology and Society 21 (1): 33. doi:10.5751/ES-08148-210133.

- Brown, H. S., P. Vergragt, K. Green, and L. Berchicci. 2003. “Learning for Sustainability Transition through Bounded Socio-Technical Experiments in Personal Mobility.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 15 (3): 291–315. doi:10.1080/09537320310001601496.

- Collective Green. 2020. “Foodsharing and Foodsaving Worldwide – A Global and Distributed Grassroots Movement against Food Waste.” https://www.collectivegreen.de/foodsharing-and-foodsaving-worldwide/

- Corsini, F., R. Laurenti, F. Meinherz, F. P. Appio, and L. Mora. 2019. “The Advent of Practice Theories in Research on Sustainable Consumption: Past, Current and Future Directions of the Field.” Sustainability 11 (2): 341. doi:10.3390/su11020341.

- Crivits, M., and E. Paredis. 2013. “Designing an Explanatory Practice Framework: Local Food Systems as a Case.” Journal of Consumer Culture 13 (3): 306–336. doi:10.1177/1469540513484321.

- Dewey, J. 1922. Human Nature and Conduct: An Introduction to Social Psychology. New York: The Modern Library.

- Dewey, J. 1928. “Body and Mind: (Delivered before the New York Academy of Medicine, November 17, 1927).” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine IV (I): 3–19.

- Dewey, J. 1929. Experience and Nature. London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd.

- Dewey, J. 1934. Art as Experience. New York: Perigee Books.

- Dewey, J. 1938a. Experience and Education. New York: Touchstone.

- Dewey, J. 1938b. Logic. New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

- Dewey, J., and A. Bentley. 1949. Knowing and the Known. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Dewey, J. 2004. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education (1915). Delhi: Aakar Books.

- Dreon, R. 2017. “Dewey on Language: Elements for a Non-Dualistic Approach.” European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy VI (2): 0–16.

- FAO. 2014. “Food Wastage Footprint & Climate Change.” http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/nr/sustainability_pathways/docs/FWF_and_climate_change.pdf

- FAO. 2018. “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. http://www.fao.org/3/i9553en/i9553en.pdf

- Feldman, M. S. 1995. “Dramaturgical Analysis.” In: Strategies for Interpreting Qualitative Data. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Foodsaving-Today. 2017a. “Foodsharing Gothenburg – Part One.” https://foodsaving.today/en/blog/2017/04/13/foodsharing-gothenburg-part1?fbclid=IwAR2XGCZjmetPen8egpgM0cEUWK5LjE12k8nV3Pvi3dhfUe5SIBIBGTrKNfc

- Foodsaving-Today. 2017b. “Foodsharing Gothenburg - Part Four.” https://foodsaving.today/en/blog/2017/06/27/foodsharing-gothenburg-part4?fbclid=IwAR3PK2SM8_Q7DU-lt7aiurw3331MuVSmr3su1nspwPG8ZtWi_JDMRG6nVs0

- Foodsaving-Today. 2017c. “Foodsharing Gothenburg - Part Three.” https://foodsaving.today/en/blog/2017/04/27/foodsharing-gothenburg-part3?fbclid=IwAR2bCNjsAs4k_s5kKUlizVpXwTOKA_jcYgLSBdQEA-lpjMss8lnnR50SHHE

- Foodsaving Worldwide. 2016. “Karrot: The Foodsaving Tool.” https://foodsaving.world/karrot

- Forum-Solikyl. 2019. “Organisatorisk struktur.” https://forum.solikyl.se/t/organisatorisk-struktur/159

- Garrison, J., L. Östman, and J. Öhman, eds. 2021, forthcoming. Deweyan Transactionalism in Education: Beyond Self-Action and Inter-Action. London: Bloomsbury.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Grin, J., J. Rotmans, and J. Schot. 2010. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change. New York: Routledge.

- Gustavsson, J., C. Cederberg, U. Sonesson, R. van Otterdijk, and A. Meybeck. 2011. Global Food Losses and Food Waste – Extent, Causes and Prevention. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Hajer, M. 2003. “Policy without Polity? Policy Analysis and the Institutional Void.” Policy Sciences 36 (2): 175–195. doi:10.1023/A:1024834510939.

- Hawken, P. 2017. Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming. London: Penguin.

- Hegnsholt, E., S. Unnikrishnan, M. Pollmann-Larsen, B. Askelsdottir, and M. Gerard. 2018. “Tackling the 1.6-Billion-Ton Food Loss and Waste Crisis.” The Boston Consulting Group. https://image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-Tackling-the-1.6-Billion-Ton-Food-Waste-Crisis-Aug-2018%20%281%29_tcm38-200324.pdf

- Ingram, J. 2018. “Agricultural Transition: Niche and Regime Knowledge Systems’ Boundary Dynamics.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 26: 117–135. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2017.05.001.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2018. Summary for Policymakers SPM. Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_SPM_version_report_LR.pdf

- Karrot. 2020. “Solikyl Göteborg.” https://karrot.world/#/groupPreview/10 (private access)

- Kolb, D. A. 2015. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Hoboken, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Köhler, J., F. W. Geels, F. Kern, J. Markard, E. Onsongo, A. Wieczorek, F. Alkemade, et al. 2019. “An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 1–32. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

- Ligozat, F., P. O. Wickman, and K. M. Hamza. 2011. “Using Practical Epistemology Analysis to Study the Teacher and Students’ Joint Actions in the Mathematics Classroom.” Proceedings of the 7th Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education, University of Rzeszow, Poland, 2472–2481.

- Loeber, A., B. Van Mierlo, J. Grin, and C. Leeuwis. 2007. The practical value of theory: Conceptualising learning in the pursuit of a sustainable development. In Social Learning Towards A Sustainable World, edited by A.E.J. Wals. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Luntley, M. 2016. “What’s the Problem with Dewey?” European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy VIII (1): 1–21. doi:10.4000/ejpap.444.

- Maivorsdotter, N., and M. Quennerstedt. 2012. “The Act of Running: A Practical Epistemology Analysis of Aesthetic Experience in Sport.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 4 (3): 362–381. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2012.693528.

- Maivorsdotter, N., and M. Quennerstedt. 2019. “Exploring Gender Habits: A Practical Epistemology Analysis of Exergaming in School.” European Physical Education Review 25 (4): 1176. doi:10.1177/1356336X18810023.

- Maivorsdotter, N., and P. O. Wickman. 2011. “Skating in a Life Context: Examining the Significance of Aesthetic Experience in Sport Using Practical Epistemology Analysis.” Sport, Education and Society 16 (5): 613–628. doi:10.1080/13573322.2011.601141.

- Maller, C. J. 2015. “Understanding Health through Social Practices: Performance and Materiality in Everyday Life.” Sociology of Health & Illness 37 (1): 52–66. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12178.

- McMeekin, A., and D. Southerton. 2012. “Sustainability Transitions and Final Consumption: Practices and Socio-Technical Systems.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 24 (4): 345–361. doi:10.1080/09537325.2012.663960.

- Mourad, M. 2016. “Recycling, Recovering and Preventing “Food Waste”: Competing Solutions for Food Systems Sustainability in the United States and France.” Journal of Cleaner Production 126: 461–477. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.084.

- Naturvårdsverket. 2020. “Matavfall i Sverige: Uppkomst och behandling 2018.” https://www.naturvardsverket.se/Documents/publ-filer/8800/978-91-620-8861-3.pdf?pid=26710

- Östman, L., and J. Öhman. 2010. A Transactional Approach to Learning. Paper Presented at John Dewey Society, AERA Annual Meeting in Denver, CO, April 30–May 4, 2010, 1–27.

- Östman, L., K. Van Poeck, and J. Öhman. 2019. “A Transactional Theory on Sustainability Learning.” In Sustainable Development Teaching: Ethical and Political Challenges, edited by K. Van Poeck, L. Östman, and J. Öhman, 127–139. New York: Routledge.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Paredis, E. 2013. “Transition Management, Policy Change and the Search for Sustainable Development.” Doctoral thes., Ghent University. https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/4100031/file/4336518.pdf.

- Puente-Rodriguez, D., J. A. A. Swart, M. Middag, and H. J. Van der Windt. 2015. “Identities, Communities, and Practices in the Transition towards Sustainable Mussel Fishery in the Dutch Wadden Sea.” Human Ecology 43 (1): 93–104.

- Reckwitz, A. 2002. “Toward a Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing.” European Journal of Social Theory 5 (2): 243–263. doi:10.1177/13684310222225432.

- Reed, M. S., M. Godmaire, P. Abernethy, and M.-A. Guertin. 2014. “Building a Community of Practice for Sustainability: Strengthening Learning and Collective Action of Canadian Biosphere Reserves through a National Partnership.” Journal of Environmental Management 145: 230–239. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.06.030.

- Rittel, H. W. J., and M. M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4 (2): 155–169. doi:10.1007/BF01405730.

- Rombach, M., and V. Bitsch. 2015. “Food Movements in Germany: Slow Food, Food Sharing, and Dumpster Diving.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 18 (3): 1–24.

- Rudsberg, K., J. Öhman, and L. Östman. 2013. “Analyzing Students’ Learning in Classroom Discussions about Socioscientific Issues.” Science Education 97 (4): 594–620. doi:10.1002/sce.21065.

- Schatzki, T. R. 2001. “Introduction: Practice Theory.” In The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory, edited by T. R. Schatzki, K. K. Cetina, and E. von Savigny. London: Routledge.

- Schatzki, T. R. 2011. “Where the Action Is (On Large Social Phenomena Such as Sociotechnical Regimes).” Sustainable Practices Research Group, Working Paper 1 (November), 1–31.

- Solikyl. 2018. “About.” https://solikyl.se/about/.

- Solikyl. 2019a. Solikyl Partner Pamphlet. Self-published.

- Solikyl. 2019b. Solikyl Volunteer Pamphlet. Self-published.

- Solikyl. 2019c. Guide för nya ambassadörer. Self-published.

- Solikyl. 2020. “Where.” https://solikyl.se/var-nar/.

- Suškevičs, M., T. Hahn, R. Rodela, B. Macura, and C. Pahl-Wostl. 2018. “Learning for Social-Ecological Change: A Qualitative Review of Outcomes across Empirical Literature in Natural Resource Management.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 61 (7): 1085–1112. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1339594.

- van Mierlo, B., and P. J. Beers. 2020. “Understanding and Governing Learning in Sustainability Transitions: A Review.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 34: 255–269. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2018.08.002.

- van Mierlo, B., J. Halbe, P. J. Beers, G. Scholz, and J. Vinke-de Kruijf. 2020. “Learning about Learning in Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 34: 251–254. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.11.001.

- Van Poeck, K., L. Östman, and T. Block. 2018. “Opening up the Black Box of Learning-by-Doing in Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 34, 298–310.doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2018.12.006.

- Voß, J., and B. Bornemann. 2011. “The Politics of Reflexive Governance: Challenges for Designing Adaptive Management and Transition Management.” Ecology and Society 16 (2): 9. doi:10.5751/ES-04051-160209.

- Welch, D., and L. Yates. 2018. “The Practices of Collective Action: Practice Theory, Sustainability Transitions and Social Change.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 48 (3): 288–305. doi:10.1111/jtsb.12168.

- Wickman, P.-O. 2012. “A Comparison between Practical Epistemology Analysis and Some Schools in French Didactics.” Éducation et Didactique 6 (2): 145–159. doi:10.4000/educationdidactique.1456.

- Wickman, P. O., and L. Östman. 2001. “University Students during Practical Work: Can We Make the Learning Process Intelligible?” In Research in Science Education - Past, Present, and Future, edited by H. Behrendt, et al. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Wickman, P. O., and L. Östman. 2002. “Learning as Discourse Change: A Sociocultural Mechanism.” Science Education 86 (5): 601–623. doi:10.1002/sce.10036.

- Wittgenstein, L. 1958. Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Yin, R. K. 1984. Case Study Design and Methods. Los Angeles: Sage.