Abstract

Environmental learning occurs through an interconnected web of opportunities. Some arise via organizations with sustainability- or environmental learning-focused missions, while others are facilitated by organizations focused on impacts and outcomes in a range of areas, such as health, social justice, or the arts. To better understand the richness of the community environmental learning landscape, we pursued a social network analysis in one place, the greater San Francisco Bay Area, California, USA. We collected quantitative and qualitative data from 256 organizations, resulting in a network of 950 organizations connected to environmental learning opportunities within the region. Our findings demonstrate that, although self-identified environmental learning providers may comprise the network’s core, the network also includes less-expected providers, primarily around the edges. Those providers often connect with related fields, such as youth development, public safety, or the arts, among others, forming a complex environmental learning landscape. We suggest opportunities to daylight and enhance the efficacy of collaborations among organizations to advance diverse and reinforcing interests. Moreover, we suggest that a network analysis approach is useful for understanding how organizations relate to each other through their connections and collaborations, providing community members with a robust ecosystem of lifelong learning supports.

Introduction

Tackling today’s most challenging socio-environmental issues—such as climate change, resource scarcity, pollution, and habitat loss, among others—requires the active, ongoing engagement of community members to conserve, protect, and restore the environment, now and for the future. Environmental education (EE) provides a key pathway to doing so as it builds people’s knowledge base, skillset and capacity to work individually and collectively at a range of scales to care for the natural world through developing an action orientation (Clark et al. Citation2020). Historically, environmental education has included environmental responsibility at its core (UNESCO Citation1978), emphasizing opportunities for people to learn about the environment, deepen place-based connections, and hone citizenship and environmentally related skills to actively engage over time (Ardoin Citation2006; Braus Citation2020; National Research Council Citation2002; Schild Citation2016).

Organizations operating at a variety of scales—neighborhood, community, regional, national, and international—provide resources, guidance, structure, and opportunities for environmental learning through programming, professional development, interpretive elements (e.g. exhibitions, trails), and other active and passive supports. In addition to those organizations, research in psychology, anthropology, education, and additional interdisciplinary fields increasingly emphasize everyday-life learning, or the interstitial spaces and places where people learn throughout the course of their everyday lives (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2015; Dierking and Falk Citation2016; Gould, Ardoin et al. Citation2019), in real-world settings (Bolger et al. Citation2018).

One manifestation of this growing emphasis on everyday environmental learning is an expansion of environmental learning boundaries to include organizations that focus on community development, food security, public health, transportation, urban planning, and/or youth development, among other related topics (Ardoin, Clark, and Kelsey Citation2013; Gould et al. Citation2016; Krasny and Tidball 2015). In many cases, these organizations address issues that are relevant or central to the lives of people and populations often marginalized in various aspects of society (Aguilar, McCann, and Liddicoat Citation2017; McKenzie et al. Citation2017; Stapleton Citation2020). Although they do not specifically emphasize environmental outcomes, such organizations often provide opportunities for environmental learning. An urban gardening collective, for instance, may enhance food security, personal health, and a sense of community belongingness, perhaps as primary desired outcomes. Yet these outcomes may often intertwine with more obviously ‘environmental’ outcomes that the collective also values, such as increased pollinator activity and pro-environmental behaviors (Teig et al. Citation2009). Instances such as these motivate and align with the increasing intersectionality of environmental education research.

Theoretical underpinnings

Community environmental education

The growing emphasis on community environmental education recognizes that environmental learning involves a broad set of actors who collaborate toward building wellness and resilience within place, often employing a transformative learning frame (Aguilar Citation2018; Krasny et al. Citation2016; NAAEE Citation2017). Leveraging notions of integrated social-ecological systems (SES), social and environmental outcomes are considered parts of an integrated whole (e.g. Berkes, Colding, and Folke Citation2008). It also relates to the notion that community-based conservation requires a ‘constellation of actors’ to meet sustainability goals (Alexander, Andrachuk, and Armitage Citation2016, p. 155). Through this lens, although EE might not be at the forefront of an organization’s goals, that organization may still have an important role in advancing understanding of environmental issues or environmentally favorable outcomes.

This focus on a broader set of community actors involved in environmental learning and action provides an opportunity to advance EE-related goals—including environmental literacy, connection to place, and sustainability-related civic engagement—at a scale larger than the individual. A challenge, however, is to critically consider how such a diverse set of organizational actors can collaborate, intentionally or incidentally, to channel efforts effectively. Debates have arisen among community organizers, public intellectuals, researchers, and others who attempt to develop guidelines and heuristics for structuring and streamlining population-level action among organizations. One such debate involves the concept of collective impact (Kania and Kramer Citation2011). Descriptions of collective impact propose core principles that facilitate population-level coordination; these principles include shared agendas and measurement, mutually reinforcing activities, and support from a backbone organization. Yet while these principles may effectively facilitate coordination that leads to some desired outcomes, goals, and missions for social change, they can also overshadow other approaches—such as those that center on equity, focus on systemic issues, and meaningfully include the voices of marginalized communities—which are, many claim, essential to authentic, enduring social change (Stachowiak and Lynn Citation2018; Wolff Citation2016; Wolff et al. Citation2017).

A central, critical question then becomes: How might we identify, engage, and more effectively channel efforts of existing and potential partners, especially those that may operate outside of networks that are considered traditionally to be ‘environmentally focused’? A crucial step to addressing this question is identifying the full set of organizational actors that comprise the interconnected web supporting community environmental education. Generating a list of organizations that focus on environmental and sustainability education in a particular (geographic) area may be relatively straightforward, as those organizations may include similar language in their missions; be tightly connected through programming and events; share professional organizations or funding sources; and potentially be visible to each other through shared physical proximity (e.g. a science-and-technology park or arts-and-culture district). Yet, similar to the challenge of identifying an appropriate range of stakeholders to engage in natural resource management decision-making processes (Colvin, Witt, and Lacey Citation2016), identifying the broader set of community actors involved in, supportive of, or facilitating environmental learning (i.e. those that do not include environmental education explicitly in their mission) may be more difficult. We set out to address this challenge through depicting the diverse, and potentially diffuse, set of actors influencing and offering environmental learning opportunities in California’s greater San Francisco Bay Area.

Social network theory

Social network theory addresses how interrelated actors—individuals or organizations—are connected and exchange resources of many kinds, including tangible (e.g. funding, programmatic materials) and intangible (e.g. knowledge) resources (Bernard et al. Citation1990; Wasserman and Faust Citation1994; Wellman and Berkowitz 1988). Social network analysis (SNA) is a method that operationalizes network theory to identify a network’s actors (or ‘nodes’) and their characteristics (or ‘attributes’), analyze how those actors engage with one another, and understand how those interactions influence group structure and function (Borgatti et al. Citation2009; Scott Citation2000). Researchers have employed SNA, which has strong theoretical roots in mathematics and computational science, to understand and change practice in many fields (Borgatti et al. Citation2009). Those fields include, but are not limited to, health (e.g. Chambers et al. Citation2012; Jessani et al. Citation2018; Valente et al. Citation2015); business (e.g. Bonchi et al. Citation2011); natural resource management and conservation (e.g. Groce et al. Citation2019; Newig, Gá¹»nther, and Pahl-Wostl Citation2010; Prell, Hubacek, and Reed Citation2009; Tindall and Robinson Citation2017); and education (Carolan Citation2014; Cela, Sicilia, and Sánchez Citation2015; McFarland et al. Citation2014).

Within these and other domain-specific areas, researchers have applied SNA to reveal what inter-organizational connections exist and understand their implications. SNA studies address, for example, information exchange and utilization (Rindfleisch and Moorman Citation2001), knowledge management and learning (Powell, Koput, and Smith-Doerr Citation1996; Uzzi and Lancaster Citation2003), capability development (McEvily and Marcus Citation2005), interfirm collaboration (Ahuja Citation2000; Owen-Smith and Powell Citation2004; Uzzi Citation1997), and broader strategic advantages to interfirm relationships (Gulati, Nohria, and Zaheer Citation2000).

Other researchers have employed SNA findings to support discussion and subsequent action within a geographical, professional, or interest-based community. For example, Vance-Borland and Holley (Citation2011), whose methodological approach heavily influenced the design of our study, applied SNA to map conservation actors (individuals) in a county in the state of Oregon (USA). The researchers then shared those initial findings with current network members. Discussion of the network structure facilitated consideration of potential new relationships that might further enhance the members’ work. Vance-Borland and Holley describe multiple partnerships and initiatives that emerged from those subsequent conversations.

Within all of these studies, two primary types of social network analyses exist: sociocentric and egocentric. In sociocentric, or ‘whole network’, analyses, researchers establish an ex ante boundary, predefining the members of a network and thus including certain actors and excluding others (Perry, Pescosolido, and Borgatti Citation2018). Researchers may draw network boundaries based on any number of characteristics, such as group membership, geography, task-orientation, or shared identity (Carrington, Scott, and Wasserman Citation2005). During the sociocentric network-analysis process, researchers then ask respondents to report on and describe relationships between the actors within the defined group. The goal is to understand additional characteristics of and interactions among those actors as they relate to the whole. Importantly, these analyses also acknowledge ‘historical time, geographical space, and social place’ as factors that ‘shape the opportunities for and constraints on the nature of social interactions’ (Pescosolido and Rubin Citation2000 in Perry, Pescosolido, and Borgatti Citation2018, p. 26).

Alternatively, egocentric, or ‘personal’, network analysis focuses on the relationships that each individual or organization has with actors in its local network. In the egocentric approach, respondents free-list actors and report on the characteristics of those actors, the interactions the respondent has with them, and the interactions among the actors the respondent named (McCarty Citation2002). This approach is useful when the researcher wants to understand attributes of network members (called compositional variables in networks) and an individual actor’s engagement with the local network members (structure of the network) (Kogovšek and Ferligoj Citation2005; Marquez et al. Citation2018; McCarty, Killworth, and Rennell Citation2007; Wasserman and Faust Citation1994). This approach is also desirable when the researcher does not know, or does not wish to limit, the boundaries of network actors ex ante.

Foundational in the field of social network analysis, Wasserman and Faust (Citation1994), Burt (Citation2005), and many of their successors have identified advantages of highly connected sub-groups, including transmitting information and learning together efficiently, facilitating cohesion, fostering trust, and building social capital among actors. These are, in turn, helpful for facilitating shared decision making, resource sharing, and action. Such concepts have been applied to many fields, including but not limited to, conservation and natural resource management (Vance-Borland and Holley Citation2011).

Potential disadvantages also exist with highly connected groups, particularly if groups’ internal activities lead to the exclusion of outsiders. Most notably, groups that fail to access diverse ideas through outside actors can stifle opportunities for innovation (Granovetter Citation1973, Citation1983). In fact, it has been argued that organizations benefit most from engaging with a heterogeneous set of actors, striking a balance between strong intra-group ‘bonding’ connections that facilitate trust and inter-group ‘bridging’ connections that facilitate access to a diversity of knowledge and resources (Bodin, Crona, and Ernstson Citation2006; Newman and Dale Citation2005).

Research questions

Such network-motivated approaches offer insight into relational aspects of communities and provide opportunities to examine connections among ideas and perspectives within a group of actors. Thus, they are well-suited to address the following driving research questions in our study:

Who are the (organizational) actors that provide, or collaborate to support, environmental learning opportunities within the (eco)region known as the greater San Francisco Bay Area?

How are these organizational actors connected to others in the network, and more specifically, do organizations cluster based on shared geography, primary field of work, or other characteristics?

How does the nature of those connections help us understand environmental learning as a lifewide, lifelong process?

How can social network analysis contribute to our understanding of how organizations engage with one another to support environmental learning?

Methods

Study area

We conducted an inter-organizational network analysis study in the greater San Francisco Bay Area of California (hereafter, ‘the Bay Area’), which is a 12-county region designated as the San Francisco-San Jose-Oakland Combined Statistical Area (U.S. Department of Commerce Citation2012) (). Encompassing a range of ecosystems, land uses, and residential types, the region has been connected not only ecologically, but also socio-culturally, economically, and politically, for generations, through native tribal bands living and moving through and around the area (Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area Citation2015). More recently, collaborative planning efforts across various governmental and nongovernmental sectors have connected Bay Area people and places through trajectories including, but not limited to, education, environment, recreation, transportation, food production, and more (e.g. Association of Bay Area Government—https://abag.ca.gov/; Bay Area Council—https://www.bayareacouncil.org/). Coupled with local, regional, and state interests, investments, and policies, the ecoregion’s mosaic of ecosystems—from coastal plains to mountain ridges to redwood forests (Ricketts et al. Citation1999)—have motivated and continue to foster an abundance of environmentally focused organizations. Many of those desire to better understand how their work might advance overall opportunities for environmental learning and related action in the region (Gould et al. Citation2018).

Within that context, this study was part of a multi-stage, mixed-methods research initiative examining how, when, where, why, and with whom people in the ecoregion learn about the environment and what motivates them to act sustainably within a community and regional context. The project is grounded in literature at the nexus of social-ecological systems and sense of place theories (e.g. Stedman Citation2016; Masterson et al. Citation2019), using a systems lens to explore for mechanisms and opportunities that influence environmental learning and action. In particular, the overarching theoretical frame draws on perspectives from Berkes and Folke (Citation1998; see also Colding and Barthel Citation2019), positing that social and ecological systems are intimately intertwined, reflecting dynamic interactions and ongoing feedback loops, contextualized within local institutions (Colding and Folke Citation2001). In this component of the study, we employed a social network analysis to give special consideration to the ‘where’ and institutional ‘who’ question(s), seeking to identify the range of organizations that support environmental learning either directly or through interactions with other organizations.

We pursued this research in parallel with efforts to initiate and incubate a collaborative (eco)regional-scale group working in fields related to environmental education. This network analysis was designed to elicit data to document baseline conditions. Initially called the Environmental Education Collaborative, and later renamed ChangeScale, the initiative was designed using a collective-impact framework (Kania and Kramer Citation2011) with the intention of advancing environmental education in the 12-county greater San Francisco and Monterey Bay Areas (Biggar, Ardoin, and Morris Citation2017).Footnote1 Representatives from the ChangeScale steering committee, which included members of nonprofit organizations, local and regional government agencies, and charitable foundations, provided consistent feedback and insights that helped enhance the relevance of our questions, the practicality of our methods and data-collection processes, and the applicability of our findings. ChangeScale hosts regional convenings multiple times per year; we sought feedback from participants at three of those (once after the initial data collection, once after the final data collection, and once during the final data analysis). As such, this study benefited from consistent feedback and engagement with regional organizational stakeholders.

Data collection and analysis

We were motivated by a desire to understand how the processes and outcomes of environmental education, including environmental learning, literacy, and engagement, might be advanced through considering a broad set of actors, such as those envisioned within a community environmental education frame. Therefore, we undertook an inter-organizational SNA study with the goal of exploring and better understanding the landscape of organizations providing and supporting environmental learning opportunities in the geographical region of the greater Bay Area. We acknowledged at the outset that it would be impossible—and antithetical, given our objective—to create a pre-defined boundary around a designated set of actors, thus suggesting that we should pursue, as described above, a personal or egocentric network approach. Yet, we were concurrently interested in exploring the full set of actors and their relationships in a comprehensive way, which necessitates a whole network approach.

We therefore pursued an integrated SNA approach, which involved soliciting personal networks and combining those to approximate a whole network to identify and better understand the relationships among organizations. This approach has been used to take advantage of both network approaches in cases where overall group membership is not well defined in advance, yet estimating structural characteristics of the whole network is valuable (Yang and Leskovec Citation2014; Wojcik Citation2011). In taking this approach, we sought to: 1) test this method as a means to identify a more expansive network of actors in the environmental learning landscape than might have been explicitly included otherwise; and 2) better understand the members and connections within a dynamic network at one point in time. The resultant network included organizations that directly or explicitly provide environmental learning opportunities, as well as those that do not directly or explicitly focus on the environment, conservation, stewardship, sustainability, or other synonymous areas.

With the goal of identifying as many organizations comprising the environmental learning landscape as possible, we collected inter-organizational network data in multiple, iterative ways in 2012–2013 (). We first conducted a web-based field scan to identify organizations providing some form of environmental learning opportunity to people in each of the 12 counties in our study area. Not intending to create a definitive or comprehensive list, our objective was to identify a list that represented the range of organizations in each county, from ‘heavy hitters’ (e.g. large museums and aquaria) to somewhat hidden, perhaps surprising entities that might not self-identify as environmental education providers (e.g. biking groups, virtual parenting communities). This initial list of organizations served as a starting place for the iterative network data collection efforts that followed, which we designed to garner a more comprehensive overall dataset. For each organization, we sought contact information for the person most directly involved with education or outreach. When possible, this was the person responsible for environmental education programming; alternatively, we identified the outreach or communication director. When an organization had neither dedicated education nor outreach staff, we contacted the executive director.

Table 1. Summary of data collection methods.

Next, we developed, piloted (with Environmental Education Collaborative members), revised, and distributed findings from Round 1 of the network survey. We sent this survey instrument to the 385 organizational representatives identified through the field scan. We included a request to forward the survey to the person at the organization best suited to answer questions about environmental learning-based activities and collaborations. In this egocentric network survey, we asked each organization about the organization itself (e.g. geography, primary fields of work); the 6 (required minimum) to 12 organizations with which the respondent organization worked most frequently to accomplish its mission; and the inter-organizational relationships between the respondent organization and their named collaborators as well as the relationships among the collaborators themselves.

After receiving the egocentric network data from respondent organizations in Round 1 of the survey, we combined these data into one comprehensive dataset. To do this, we compiled all of the relationship data about each organization (both organizations that responded and those that were listed by other organizations). This resulted in one comprehensive network dataset, which we analyzed using sociometric network analysis techniques within the UCINET software package (Borgatti, Everett, and Freeman Citation2002).

Once we integrated, analyzed, and visualized this combined network dataset, we used these outputs to ground-truth our initial network findings, elicit additional inter-organizational relationship data, and better understand the relationships that emerged. To accomplish this, we presented the results of our Round 1 network analysis at an Environmental Education Collaborative public meeting. We provided an individualized worksheet to representatives from each of the 71 pre-registered organizations that had either responded to the survey or been named by a responding organization (or both). Each individualized worksheet included a network diagram specific to that organization, illustrating the inter-organizational relationships discovered through the Round 1 survey. We invited each organization to reflect on their diagram and indicate additional organizations and relationships they believed were instrumental to accomplishing their EE-related missions, as well as to provide qualitative responses describing their relationships with other organizations. We also used this opportunity to follow up with organizational representatives and collect qualitative data for context-building and interpretation of observed results.

We collected our final data in Round 2 of the SNA survey. The SNA survey instrument remained the same between Rounds 1 and 2, while the potential respondents differed. In Round 2, we requested responses from any organizations that had been named by Round 1 survey respondents or had been named on the Environmental Education Collaborative meeting worksheets. We used the same process to combine all of the egocentric data collected in Rounds 1 and 2 and then analyzed the resulting whole-network dataset.

We analyzed the sum total of network data using R scripts designed to conduct sociometric network analyses. We used a fast-greedy community detection algorithm to identify sub-groups, or ‘communities’, within the sociometric network. We selected this hierarchical approach because of its focus on bottom-up rather than top-down network structures and its emphasis on finding community structures within networks (Clauset, Newman, and Moore Citation2004). Fast-greedy also tends to underestimate the number of internal communities identified compared with other algorithms that may overestimate and identify a larger number of sub-groups (Yang, Algesheimer, and Tessone Citation2016); this aligned with our research approach exploring larger sub-groups that might not be detected through other means. After the algorithm statistically identified sub-groups, we then conducted a qualitative analysis to identify common topics or emergent themes among sub-group members.

Results

In total, we received 256 network survey responses (32% response rate) (). Combined with in-person feedback at an Environmental Education Collaborative meeting, those responses collectively identified 950 organizations whose work, according to respondents, directly engaged in or supported environmental learning efforts in the Bay Area.

Table 2. Responses to network survey.

Fast-greedy sub-groups and whole-network plots

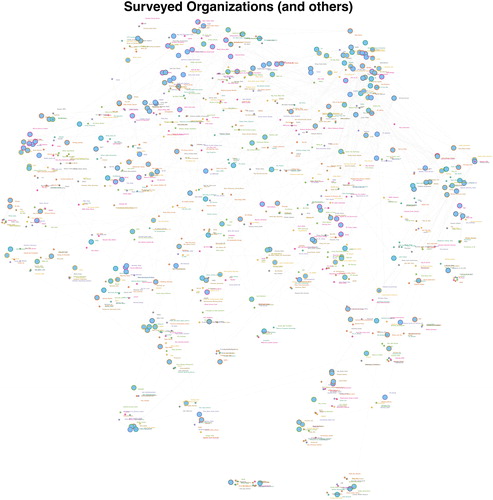

The fast-greedy algorithm identified 30 sub-groups within the combined whole network. Each sub-group comprises a subset of organizations that is statistically more similar within the group than between groups. To help illustrate the relationships among organizations identified by the fast-greedy algorithm, we generated several whole-network plots with the nodes on the network graph representing organizations that were surveyed or identified by survey respondents. Those two-dimensional network plots represent three-dimensional groupings based on the results of the algorithm, with organizations pictured near one another statistically more closely associated than organizations located farther apart on the plot. We used the same layout for each to facilitate comparison among plots.

An initial observation of the whole-network plotFootnote2 (), in which large nodes represent respondents and small nodes represent named non-respondents, indicated that the combined whole network is composed of many more organizations than were initially identified and surveyed. This suggests that many of the organizations named in this study were not identified in the initial web-based field scan or included in the initial list of environmental learning providers, even broadly defined. Thus, this expanded network study approach identified many new organizations supporting a broader ecosystem of environmental learning that might not otherwise have been recognized or documented.

Primary fields of work

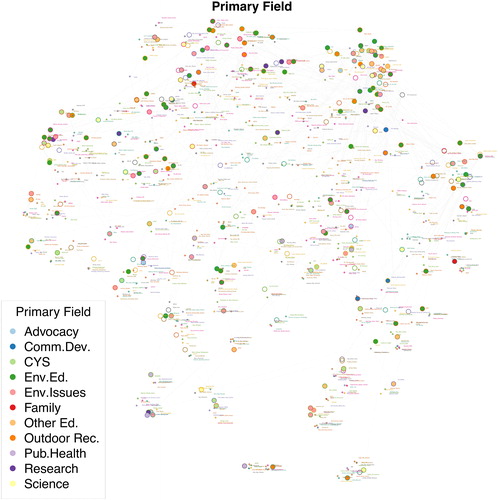

Initially, we analyzed the characteristics of survey respondents. We noted that respondent organizations reported highly variable primary fields of work. Although roughly two-thirds of responding organizations indicated that environmental education was one of their top four fields of work, fewer than half indicated environmental education as one of their top two priorities and fewer than one-quarter indicated that environmental education was their number-one priority ().

Table 3. Primary fields of work among respondent organizations.

Organizations reported the following as common fields of focus: environmental issues, outdoor recreation, science, and non-EE education. Organizations also described focal areas that emphasized more social, less environmental dimensions of community, such as community development (named by approximately one-fourth of the respondents), child and youth services (CYS), and public health.

To examine the work of organizations that did not list environmental education as one of their four primary fields (about one-third of respondents), we categorized responses with the intention of analyzing qualitative data about the reported organizational services. Policy work and professional development were the top services and areas of focus identified among organizations that did not list environmental education as one of their four primary fields. Other areas of focus mentioned included administrative services, such as facilities, infrastructure, and funding.

A plot illustrating organizations’ primary fields () reinforces the observation that primary fields vary widely among organizations in this study, and those variations exist within statistically clustered groups. In nearly all cases, nodes of many colors, each indicating a similar range of primary fields, are found close to one another. The heterogeneity of organizational fields of work, which spans across all of the identified sub-groups, underscores the diversity of actors that support environmental learning in some way.

Geography

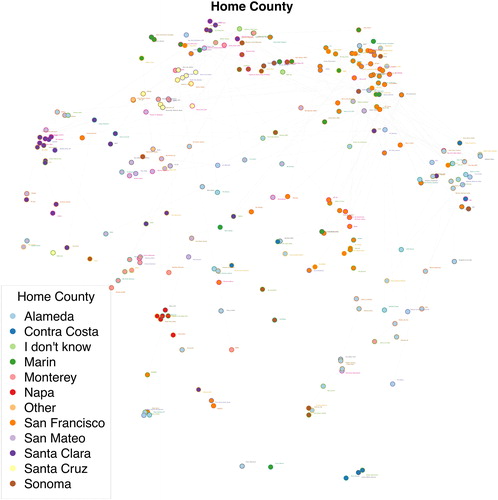

Although there is considerable heterogeneity among organizational relationships with respect to their primary field of work, similarities exist with regard to geographical proximity, as measured by respondent organizations’ home counties. Of the 30 sub-groups identified by the fast-greedy algorithm, more than half of the groups shared a geographic focus in their work. In the whole-network plot, organizations based in the same county, indicated by node color, tended to cluster ().

Figure 4. Geographic location (Bay Area County where organization’s home/main office is located), as indicated by node color. Only surveyed organizations were asked this information and are represented.

During our qualitative follow-up, several organizational representatives mentioned the importance of in-kind resource sharing, noting that this is facilitated when organizations are geographically proximal and can therefore access services or resources more easily. One organization, for example, described using another organization’s space for conducting educational activities. Organizations also discussed the importance of accessing shared facilities (e.g. labs), personnel (e.g. experts), and equipment.

Within groups sharing geographic proximity, organizations described undertaking a range of activities to support environmental learning. One such grouping included a social justice-focused elementary school, a grassroots activist watchdog group focused on pollution, a district’s neighborhood center, a youth development group, a local-scale newspaper, a food bank, two universities, and two community gardening initiatives.

Organization size

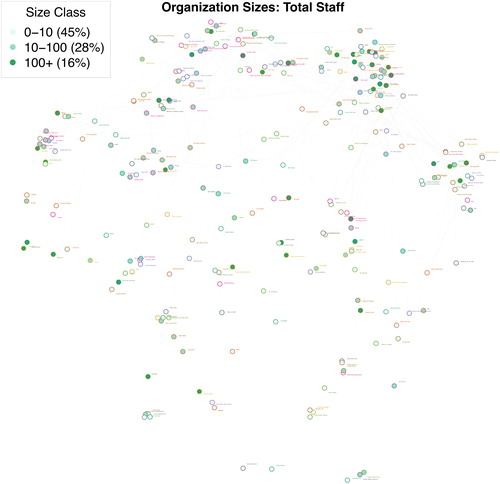

One organizational attribute of note was organizational size. We were particularly interested in potential homophily or heterogeneity among organizations of similar sizes within identified groups. Of the 226 organizations that indicated their number of employees, 45% were small (0–10 staff members); 28% had 10–100 staff members, and 16% were large (100 or more staff members). Close to half (44%) of the large organizations were located in San Francisco County ().

Figure 5. Organization size (total number of staff members), as indicated by node shading. Only surveyed organizations wereasked this information and are represented.

All sub-groups with three or more organizations, as identified by the fast-greedy algorithm, had a higher proportion of small- to medium-sized organizations than large ones. Our qualitative data bore this out, as some large organizations cited their desire to share expertise and resources with smaller organizations, while small- to medium-sized organizations spoke about the advantages associated with their affiliations with larger organizations.

One example of such a grouping of organizations of various sizes and types working together draws from multiple counties. This includes a small rural farm offering educational programs, an urban-based sustainable food organization, a regional governmental farm agency, a state-level farmer advocacy organization, and a large international conservation NGO.

Topic or theme

After our initial analysis, we dove deeper into the responses among fast-greedy sub-group members and discovered that several were organized around a particular theme or set of topics. The largest group identified, for example, had 131 organizations from across the Bay Area; the consistent emergent theme within this sub-group was a focus on conservation. Another sub-group focused on water. This diverse subset included two city governments, a gardening store, an organization that provides eco-friendly pest management services, a regional pollution-prevention organization, and three state departments (two related to water, one to public health). Additional examples of sub-group themes included: recycling; food, equity, and education; outdoor recreation; boating and coastal expeditions; youth development and religious organizations; and BIPOC, organizing, and justice.

We also found clusters that included both a geographic focus and a thematic overlap within a sub-group. One example was composed of organizations located in adjacent counties with large urban centers and focused on related themes around biking, air quality, and asthma.

Discussion

Motivated by a desire to better understand some of the complexities inherent in an ecosystem of environmental learning opportunities, we set out to explore the landscape of providers in California’s greater San Francisco Bay Area, a region well known for its abundance of environmental and science-focused organizations. We left open the possibility that the landscape might include unexpected providers and collaborators by using an inter-organizational network approach that combined egocentric data collection with sociometric analysis. This approach, informed by a community environmental education lens, allowed us to identify a broader set of organizational actors and expand our understanding of the environmental learning enterprise. Applying SNA methods helped make explicit the relationships and opportunities that environmentally focused organizations have to broaden their networks to include non-traditional actors.

In our analysis, this possibility flourished: the environmental learning landscape we identified includes hundreds of organizations with foci other than environmental education. Our findings bring evidence to bear on what many in the EE field understand: the applicability of ‘environmental education’ reaches, and is informed by, fields, content areas, and interests well beyond those directly labeled as ‘environmental education’. Some organizations provide rich opportunities for learning about and motivating action related to the environment, especially within an everyday-life context. Although others may have missions focused on different topics, they, too, play integral roles in the landscape as facilitators and supporters of environmental learning, as identified and described by fellow organizations. Those ‘unusual suspects’, or organizations not typically recognized as EE providers, interact with each other and with more-traditional EE organizations, through providing rich opportunities either for partnerships or for engaging in environmental learning via alternative pathways and lenses. Together, the diverse group of nearly 1,000 organizations identified in this network contributes to an overall sense of community and continuity between everyday-life experiences and environmental learning.

Our findings are supported, and undergirded, by the concept of social-ecological systems (SES), a framework for contextualizing environmental issues. SES theory derives from the central premise that humans are part of one constantly interacting, dynamic system (Berkes and Folke Citation1998). This approach describes much empirical work more accurately than do reductionist, or compartmentalized, conceptions of ‘humans’ and (or versus) ‘nature’ (Binder et al. Citation2013). A core implication of an SES approach is that diverse societal institutions—not only those with obvious links to ecosystems—are relevant to management of ecological phenomena (Ostrom Citation2009; Berkes and Folke Citation1998; Colding and Folke Citation2001). That is, the social aspects, or human dimensions, of environment and sustainability issues involve not only those organizations and agencies that address issues such as pollution, energy regulation, and resource management, but also those focused on cultural norms, values, governance structures, individual and collective behavioral choices, and scores of other social phenomena, including issues of power and diversity (Fabinyi, Evans, and Foale Citation2014).

The environmental education field has long embraced a systems approach (Smyth Citation2006; Krasny and Tidball Citation2009). Aligned with SES concepts, EE-focused organizations often engage with a variety of other groups to facilitate interconnectedness and consideration of biophysical as well as human dimensions of environmental systems. The organizations identified in our network illustrate this breadth and integration. They include park-management services and pollution-management agencies, as well as those that seem, on the surface, to be removed from ‘the environment’, such as private for-profit businesses, religious groups, arts programs, and school districts, among others. Thus, this network may begin to present a more complete picture of the social-ecological system of which EE is a part.

Moreover, although the environment is moving up on the list of policy concerns among the U.S. public (Pew Research Center Citation2020), even nearing the level of concern for the economy at the top of this list (64% versus 67%, respectively as of early 2020), it is unclear how the dramatic, wide-ranging economic and public-health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic may shift those priorities. Environmental concerns may—in the short, medium, and long term—fall dramatically in priority as governments and communities focus on the economy, education, inequality, and health. Shifts in these societal priorities may be reflected in shifts in funding opportunities and mechanisms, which may profoundly impact how environmental organizations strategically pursue their work, including the potential for enhanced attention on new partnerships with non-environmentally focused organizations. Further, as climate change impacts are increasingly felt in other aspects of society (e.g. public health, housing security), it is likely that organizations primarily focused on non-environmental topics may also pursue enhanced connections with environmental organizations. Social-ecological systems theory emphasizes intersections among these elements, and thus conceives of environmental concerns as indistinguishable from human life in general. ‘Environmental’ concerns intertwine with health, equity and justice, employment, education, transportation, security, and other perceived primary concerns, so ‘environmental education’ that aligns with a social-ecological systems perspective involves what are currently seen as cross-sector relationships. Our network analysis identifies hundreds of these types of relationships.

Intersecting with SES approaches, sense-of-place concepts—as emphasized by scholars in fields such as geography, sociology, psychology, and anthropology, among others (Lewicka Citation2011)—are evident in our findings. Theoretical perspectives as well as empirical studies support the intertwining of concepts linked to sense of place and SES, particularly as SES changes can impact individuals’ sense of place and can be important motivators for environmental stewardship (Masterson et al. Citation2019). The sense of place literature identifies the multi-faceted, multidimensional nature of place relationships; it emphasizes that ‘place’ has, for instance, biophysical, socio-cultural, political-economic, and internal dimensions (Ardoin, Schuh, and Gould Citation2012). This is highly consistent with our findings, where the wide range of organizations and relationships within the network we uncovered offers opportunities for this diversity (Ardoin, Schuh, and Gould Citation2012; Ardoin et al. Citation2019) and reinforces the importance of offering varied resources and supports for learning about and interacting with the environment, because the ‘environment’ involves such a broad array of aspects of life (Ardoin Citation2006; Kudryavtsev, Stedman, and Krasny Citation2012).

Linking to this sense of place perspective, we found shared geography to be a key variable defining many of the sub-groups within our network, with home county in particular being a driver for connection. Relationships among geographically proximal organizations are likely influenced not only by convenience and ease of resource sharing, but also by a shared sense of purpose and connection to a particular place. This interconnectedness among organizations sharing SES features, whether sociocultural, political-economic, or biophysical, can be a powerful driver for sustained collaboration and mutual support. Environmental education organizations, therefore, should consider pursuing geographically based coalition-building activities that reinforce the inherent interconnectedness among organizations and opportunities in a shared place. This coordination is likely to yield both programmatic and fiduciary benefits, enabling all collaborators to leverage a wider variety of funding opportunities in a highly competitive environment.

In our study, respondent organizations clearly benefit from their relationships with each other. The connections described speak specifically to organizations’ ability to accomplish their missions, which is made possible through creative and sustained partnerships. This is particularly true of organizations’ closest connections, which are often facilitated or reinforced by geographic proximity or shared interests, although not necessarily their primary field of work. The range of organizations that we identified suggest that environmental education organizations should continue to actively seek connections to organizations beyond what might have once been considered ‘typical’ in EE, thus expanding access to new information and ideas and, in turn, opening greater opportunities for innovation. Finding new solutions is critical in this time of immense challenge; this study’s results suggest how engaging an increasingly broader set of actors in the environmental learning landscape can benefit our organizations, communities, and the environment.

Limitations

This study has limitations, as do all. First, networks are dynamic (cf, Matous and Todo Citation2015); therefore, the structure we describe depicts this network at one point in time. Our intention was not to present a definitive set of network actors and connections, but to be as inclusive as possible in data collection and to demonstrate the implications of applying a more expansive—and participatory—approach to identifying network actors in support of environmental learning. Second, due to the nature of the data-collection instrument, our interpretation represents the perceptions of one or perhaps a few individuals from each organization. Within any organization, differing perspectives most certainly exist about which external relationships are most influential, how those relationships function, and how these relationships may shape an organization’s work. Third, due to resource constraints and limitations that mirror those in most survey studies, we were not able to obtain network analysis data directly from all 950 organizations in the comprehensive whole network we identified. Our multi-stage design did, however, enable us to engage a robust subset of network actors (710 organizations contacted, 256 respondents), which allowed us to better understand the broader landscape of inter-organizational relationships and draw the conclusions presented here. Finally, while structural characteristics of the resultant whole network are interesting and provide some insights, a statistical understanding of network structure was neither anticipated nor sought. The design of this study, which we began with a certain list of organizations obtained in the Web-based field scan, means that those organizations are more likely to appear as central within the network.

Our research design effectively met the goal of our study, namely, to identify and explore the broad environmental learning ecosystem, including perhaps previously unidentified members of the landscape. We thus present a snapshot of the organizations and relationships in this network, while recognizing that no single network representation can illustrate a comprehensive picture of all relationships across time.

Conclusion

Applying an SNA approach, we were able to investigate and make explicit the breadth of organizations at work in the environmental learning landscape and identify patterns in how those organizations work together. Our findings emphasize that people learn about the environment not only through scientific investigations, or solely through a focus on natural history or time in nature, but rather, environmental learning is the domain of an expanding landscape that permeates everyday life. Although organizations with environmental education as their core mission play an important and often anchoring role in the environmental learning network that we studied—and likely in other networks and geographies as well—our results suggest that the efforts of those core groups are, and must be, bolstered and extended through connections with other organizations that focus on a range of everyday-life aspects. Those dynamic organizational ecosystems foster interconnected environmental learning networks, which in turn support a rich, complex sense of place that has the potential to benefit environmental literacy and action. Examples of other bolstering organizations include those that support socio-cultural dimensions (e.g. a public art incubator); political-economic dimensions (e.g. community-development organizations, a job retraining agency); and/or psychological dimensions (e.g. a family wellness center).

In these ways, community organizations nurture boundary spaces that demonstrate, in practice, the myriad ways that ‘environment’ is not solely the purview of science or nature centers, but rather is infused throughout daily life. The environment is everywhere, spanning multiple dimensions and, thus, requires representation by and support from an interconnected landscape of organizations. Importantly, this aligns with conclusions that environmental justice scholars and activists have emphasized for decades: that the environment is far more than distant landscapes in need of preservation. It is the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat (Pezzullo and Sandler Citation2007; Taylor Citation2000). In 1996, the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council described the core of environmental justice as ‘a transformative public discourse over what are truly healthy, sustainable and vital communities’ (p. 17). Our results suggest than in the Bay Area, environmental education is at least partly manifesting this holistic community focus.

Documenting the network of organizations, all supporting environmental learning in some way, relates to an identified need to highlight the relevance of such opportunities to and in people’s everyday lives. Our data provide evidence that this embeddedness and relevance are already happening, at least in the greater San Francisco Bay Area ecoregion. The outcomes of this study further suggest that environmental organizations could benefit from taking a deliberate and systematic SNA-informed approach to identifying current and potential collaborators among organizations that share geographies or thematic interests but not necessarily primary fields of work.

The next environmental learning frontier may be to more deliberately facilitate collaborations among a range of likely, or typical, and unlikely, or less-typical, partners, thus working toward fulfilling in more holistic ways the missions and goals of the range of organizations, concurrent with those of EE. To support and expand these efforts, we suggest further environmental education research into what conditions and structures facilitate successful environmental learning-supporting collaborations among diverse organizations, enhanced by existing related scholarship from other fields. Further, we suggest that future research could also investigate whether these collaborations are, in fact, helping the organizations involved to tackle the most pressing social-environmental issues.

Responding to the complex and integrated challenges around climate change, public health, and education, the next decade may bring an age where we no longer see some partners as likely and others as unlikely but, rather, recognize that the principles and practices of quality environmental learning opportunities enrich and deepen community-building and sustainability efforts of many types. Through such a process, we succeed at demonstrating that environmental learning is integrated and supported by many and varied aspects of life in a complex, interconnected network of opportunities for engagement.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the leadership and members of ChangeScale, as well as the many organizations and individuals who contributed network data and thoughtful feedback throughout this study. We also thank Timothy Podkul, Tony Vashevko, Kathayoon Khalil, Noelle Wyman Roth, and Alison Bowers for their research and editorial assistance; Nikki Nolan for creating the regional map in Figure 1; and Marika Jaeger for designing the graphical abstract.

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Deborah J. Wojcik

Deborah J. Wojcik is the Managing Director of Graduate Programs and Services and an adjunct assistant professor at the Pratt School of Engineering at Duke University. Formerly, Dr. Wojcik was a postdoctoral scholar who helped launch Dr. Nicole Ardoin’s Environmental Learning in the Bay Area project.

Nicole M. Ardoin

Nicole M. Ardoin, Emmett Family Faculty Scholar, is an associate professor with a joint appointment in the Graduate School of Education and the Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford University. She is the Sykes Family E-IPER Director of the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources (E-IPER) in the School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Sciences.

Rachelle K. Gould

Rachelle K. Gould is Assistant Professor in the Environmental Studies program and the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Vermont. Formerly, Dr. Gould was a postdoctoral scholar who worked on Dr. Nicole Ardoin’s Environmental Learning in the Bay Area project.

Notes

1 ChangeScale is a consortium of more than 50 environmental learning-related organizations, research, and philanthropic partners that work in the San Francisco and Monterey Bay Areas. ChangeScale was founded in 2011; its mission is to increase the scale and quality of collaborative program delivery, working toward a desired ultimate impact of “every generation inspired with the environmental know-how to create healthy communities and a healthy planet” (http://www.changescale.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/TOC-2.pdf). Two authors of this manuscript were part of the original steering committee.

2 For all whole-network plots, we intentionally obscured organizational names to respect confidentiality as well as protect existing and potential relationships.

References

- Aguilar, O. M. 2018. “Examining the Literature to Reveal the Nature of Community EE/ESD Programs and Research.” Environmental Education Research 24 (1): 26–49. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1244658.

- Aguilar, O. M., E. P. McCann, and K. Liddicoat. 2017. “Inclusive Education.” In Urban Environmental Education Review, edited by A. Russ and M.E. Krasny, 194–201. Ithaca, NY: Comstock Publishing.

- Ahuja, Gautam. 2000. “Collaboration Networks, Structural Holes, and Innovation: A Longitudinal Study.” Administrative Science Quarterly 45 (3): 425–455. doi:10.2307/2667105.

- Alexander, S. M., M. Andrachuk, and D. Armitage. 2016. “Navigating Governance Networks for Community-Based Conservation.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14 (3): 155–164. doi:10.1002/fee.1251.

- Ardoin, N. M. 2006. “Toward an Interdisciplinary Understanding of Place: Lessons for Environmental Education.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 11 (1): 112–126. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/508.

- Ardoin, N. M., C. Clark, and E. Kelsey. 2013. “An Exploration of Future Trends in Environmental Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 19 (4): 499–520. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.709823.

- Ardoin, N. M., R. K. Gould, H. Lukacs, C. C. Sponarski, and J. S. Schuh. 2019. “Scale and Sense of Place among Urban Dwellers.” Ecosphere 10 (9): e02871. https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ecs2.2871. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2871.

- Ardoin, N. M., and J. E. Heimlich. 2015.The Importance of the Incidental: Environmental Learning in Everyday Life. Keynote address. 12th Annual Research Symposium, North American Association for Environmental Education.n Diego, CA..

- Ardoin, N. M., J. S. Schuh, and R. K. Gould. 2012. “Exploring the Dimensions of Place: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Data from Three Ecoregional Sites.” Environmental Education Research 18 (5): 583–607. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.640930.

- Berkes, F., and C. Folke (Eds.). 1998. Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Berkes, F., J. Colding, and C. Folke (Eds.). 2008. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bernard, H. R., E. C. Johnsen, P. D. Killworth, C. McCarty, G. A. Shelley, and S. Robinson. 1990. “Comparing Four Different Methods for Measuring Personal Social Networks.” Social Networks 12 (3): 179–215. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(90)90005-T.

- Biggar, M., N. M. Ardoin, and J. Morris. 2017. Collective Impact on the Ground. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact_on_the_ground.

- Binder, C. R., J. Hinkel, P. W. G. Bots, and C. Pahl-Wostl. 2013. “Comparison of Frameworks for Analyzing Social-Ecological Systems.” Ecology and Society 18 (4): 26. doi:10.5751/ES-05551-180426.

- Bodin, Ö., B. Crona, and H. Ernstson. 2006. “Social Networks in Natural Resource Management: What Is There to Learn from a Structural Perspective?” Ecology and Society 11 (2): r2. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss2/resp2. doi:10.5751/ES-01808-1102r02.

- Bolger, D., K. Bieluch, F. Krivak-Tetley, G. Maggs-Kölling, and J. Tjitekulu. 2018. “Designing a Real-World Course for Environmental Studies Students: Entering a Social-Ecological System.” Sustainability 10 (7): 2546. doi:10.3390/su10072546.

- Bonchi, F., C. Castillo, A. Gionis, and A. Jaimes. 2011. “Social Network Analysis and Mining for Business Applications.” ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2 (3): 1–37. doi:10.1145/1961189.1961194.

- Borgatti, S. P., M. G. Everett, and L. C. Freeman. 2002. Ucinet 6 for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis (Version 6.357). Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

- Borgatti, S. P., A. Mehra, D. J. Brass, and G. Labianca. 2009. “Network Analysis in the Social Sciences.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 323 (5916): 892–895. doi:10.1126/science.1165821.

- Braus, J. 2020. “Civic and Environmental Education: Protecting the Planet and Our Democracy.” In Democracy Unchained: How to Build Government for the People, eds. D. Orr, A. Gumbel, B. Kitwana, and W. Becker, 183–195. New York: The New Press.

- Burt, R. S. 2005. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Carolan, B. V. 2014. Social Network Analysis and Education: Theory, Methods & Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Carrington, P. J., J. Scott, and S. Wasserman. 2005. Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Cela, K. L., M. Á. Sicilia, and S. Sánchez. 2015. “Social Network Analysis in E-Learning Environments: A Preliminary Systematic Review.” Educational Psychology Review 27 (1): 219–246. doi:10.1007/s10648-014-9276-0.

- Chambers, D., P. Wilson, C. Thompson, and M. Harden. 2012. “Social Network Analysis in Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Scoping Review.” PLoS One 7 (8): e41911. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0041911. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041911.

- Clark, C. R., J. E. Heimlich, N. M. Ardoin, and J. Braus. 2020. “Using a Delphi Study to Clarify the Landscape and Core Outcomes in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 26 (3): 381–399. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1727859.

- Clauset, A., M. E. J. Newman, and C. Moore. 2004. “Finding Community Structure in Very Large Networks.” Physics Review E 70 (6): 066111. https://arxiv.org/pdf/cond-mat/0408187.pdf.

- Colding, J., and S. Barthel. 2019. “Exploring the Social-Ecological Systems Discourse 20 Years Later.” Ecology and Society 24 (1): 2. doi:10.5751/ES-10598-240102.

- Colding, J., and C. Folke. 2001. “Social Taboos: “Invisible” Systems of Local Resource Management and Biodiversity Conservation.” Ecological Applications 11 (2): 584–600. doi:10.2307/3060911.

- Colvin, R. M., G. B. Witt, and J. Lacey. 2016. “Approaches to Identifying Stakeholders in Environmental Management: Insights from Practitioners to Go beyond the ‘Usual Suspects’.” Land Use Policy 52 (March): 266–276. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.12.032.

- Dierking, L. D., and J. H. Falk. 2016. “2020 Vision: Envisioning a New Generation of STEM Learning Research.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 11 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s11422-015-9713-5.

- Fabinyi, M., L. Evans, and S. J. Foale. 2014. “Social-Ecological Systems, Social Diversity, and Power: Insights from Anthropology and Political Ecology.” Ecology and Society 19 (4): 28. doi:10.5751/ES-07029-190428.

- Gould, R. K., N. M. Ardoin, M. Biggar, A. E. Cravens, and D. Wojcik. 2016. “Environmental Behavior’s Dirty Secret: The Prevalence of Waste Management in Discussions of Environmental Concern and Action.” Environmental Management 58 (2): 268–282. doi:10.1007/s00267-016-0710-6.

- Gould, R. K., N. M. Ardoin, J. M. Thomsen, and N. Wyman Roth. 2019. “Exploring Connections between Environmental Learning and Behavior through Four Everyday-Life Case Studies.” Environmental Education Research 25 (3): 314–327. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1510903.

- Gould, R. K., I. Phukan, M. E. Mendoza, N. M. Ardoin, and B. Panikkar. 2018. “Seizing Opportunities to Diversify Conservation.” Conservation Letters 11 (4): e12431. doi:10.1111/conl.12431.

- Granovetter, M. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2776392. doi:10.1086/225469.

- Granovetter, M. 1983. “The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited.” Sociological Theory 1: 201–233. http://jstor.com/stable/202051. doi:10.2307/202051.

- Groce, J. E., M. A. Farrelly, B. S. Jorgensen, and C. N. Cook. 2019. “Using Social-Network Research to Improve Outcomes in Natural Resource Management.” Conservation Biology 33 (1): 53–65. doi:10.1111/cobi.13127.

- Gulati, R., N. Nohria, and A. Zaheer. 2000. “Strategic Networks.” Strategic Management Journal 21 (3): 203–215. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200003)21:3<203::AID-SMJ102>3.0.CO;2-K.

- Jessani, N. S., C. Babcock, S. Siddiqi, M. Davey-Rothwell, S. Ho, and D. R. Holtgrave. 2018. “Relationships between Public Health Faculty and Decision Makers at Four Governmental Levels: A Social Network Analysis.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 14 (3): 499–522. doi:10.1332/174426418X15230282334424.

- Kania, J., and M. Kramer. 2011. “Collective Impact.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 9 (1): 36–41. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact#.

- Kogovšek, T., and A. Ferligoj. 2005. “Effects on Reliability and Validity of Egocentered Network Measurements.” Social Networks 27 (3): 205–229. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2005.01.001.

- Krasny, M. E., M. Mukute, O. Aguilar, M. P. Masilela, and L. Olvitt. 2016. “Community Environmental Education.” In Essays in Urban Environmental Education, edited by A. Russ and M. E. Krasny, 18–26. Ithaca, NY; Washington, DC: Cornell University Civic Ecology Lab and NAAEE.

- Krasny, M. E., and K. G. Tidball. 2009. “Applying a Resilience Framework to Urban Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 15 (4): 465–482. doi:10.1080/13504620903003290.

- Krasny, M. E., and K. G. Tidball. 2015. Civic Ecology: Adaptation and Transformation from the Ground Up. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kudryavtsev, A., R. C. Stedman, and M. E. Krasny. 2012. “Sense of Place in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 18 (2): 229–250. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.609615.

- Lewicka, M. 2011. “Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (3): 207–230. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001.

- Marquez, B., G. Norman, J. Fowler, K. Gans, and B. Marcus. 2018. “Egocentric Networks and Physical Activity Outcomes in Latinas.” Plos One 13 (6): e0199139. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0199139. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0199139.

- Masterson, V. A., J. P. Enqvist, R. C. Stedman, and M. Tengö. 2019. “Sense of Place in Social–Ecological Systems: From Theory to Empirics.” Sustainability Science 14 (3): 555–564. doi:10.1007/s11625-019-00695-8.

- Matous, P., and Y. Todo. 2015. “Exploring Dynamic Mechanisms of Learning Networks for Resource Conservation.” Ecology and Society 20 (2): 36. doi:10.5751/ES-07602-200236.

- McCarty, C. 2002. “Structure in Personal Networks.” Journal of Social Structure 3 (1): 20. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.90.8899&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- McCarty, C., P. D. Killworth, and J. Rennell. 2007. “Impact of Methods for Reducing Respondent Burden on Personal Network Structural Measures.” Social Networks 29 (2): 300–315. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2006.12.005.

- McEvily, B., and A. Marcus. 2005. “Embedded Ties and the Acquisition of Competitive Capabilities.” Strategic Management Journal 26 (11): 1033–1055. doi:10.1002/smj.484.

- McFarland, D. A., J. Moody, D. Diehl, J. A. Smith, and R. J. Thomas. 2014. “Network Ecology and Adolescent Social Structure.” American Sociological Review 79 (6): 1088–1121. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0003122414554001. doi:10.1177/0003122414554001.

- McKenzie, M., J. R. Koushik, R. Haluza-Delay, B. Chin, and J. Corwin. 2017. “Environmental Justice.” In Urban Environmental Education Review, edited by A. Russ and M.E. Krasny, 59–67. Ithaca, NY: Comstock Publishing.

- Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area. 2015. Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area: A Brief Historical Overview of a Previously Federally Recognized Trible. http://www.muwekma.org/tribalhistory/historicaloverview.html.

- National Environmental Justice Advisory Council Subcommittee on Waste and Facility Siting. 1996. Environmental Justice, Urban Revitalization, and Brownfields: The Search for Authentic Signs of Hope. Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

- National Research Council. 2002. New Tools for Environmental Protection: Education, Information, and Voluntary Measures. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/10401.

- Newig, J., D.Günther, and C. Pahl-Wostl. 2010. “Synapses in the Network: Learning in Governance Networks in the Context of Environmental Management.” Ecology and Society 15 (4): 24. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art24. doi:10.5751/ES-03713-150424.

- Newman, L. L., and A. Dale. 2005. “Network Structure, Diversity, and Proactive Resilience Building: A Response to Tompkins and Adger.” Ecology and Society 10 (1): r2. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol10/iss1/resp2. doi:10.5751/ES-01396-1001r02.

- North American Association for Environmental Education. 2017. Guidelines for Excellence: Community Engagement. Washington, DC: North American Association for Environmental Education.

- Ostrom, E. 2009. “A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 325 (5939): 419–422. doi:10.1126/science.1172133.

- Owen-Smith, J., and W. W. Powell. 2004. “Knowledge Networks as Channels and Conduits: The Effects of Spillovers in the Boston Biotechnology Community.” Organization Science 15 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1287/orsc.1030.0054.

- Perry, B. L., B. A. Pescosolido, and S. P. Borgatti. 2018. Egocentric Network Analysis: Foundations, Methods, and Models. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Pescosolido, B. A., and B. A. Rubin. 2000. “The Web of Group Affiliations Revisited: Social Life, Postmodernism, and Sociology.” American Sociological Review 65 (1): 52–76. www.jstor.org/stable/2657289. doi:10.2307/2657289.

- Pew Research Center. 2020. As Economic Concerns Recede, Environmental Protection Rises on the Public’s Policy Agenda. February. https://www.people-press.org/2020/02/13/as-economic-concerns-recede-environmental-protection-rises-on-the-publics-policy-agenda.

- Pezzullo, P. C., and R. Sandler. 2007. “Introduction: Revisiting the Environmental Justice Challenge to Environmentalism.” In Environmental Justice and Environmentalism: The Social Justice Challenge to the Environmental Movement, edited by R. Sandler and P. C. Pezzullo, 1–25. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Powell, W. W., K. W. Koput, and L. Smith-Doerr. 1996. “Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology.” Administrative Science Quarterly 41 (1): 116–145. doi:10.2307/2393988.

- Prell, C., K. Hubacek, and M. Reed. 2009. “Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in Natural Resource Management.” Society & Natural Resources 22 (6): 501–518. doi:10.1080/08941920802199202.

- Ricketts, T. H., E. Dinerstein, D. M. Olson, W. Eichbaum, C. J. Loucks, P. Hedao, P. Hurley, et al. 1999. Terrestrial Ecoregions of North America: A Conservation Assessment. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Rindfleisch, A., and C. Moorman. 2001. “The Acquisition and Utilization of Information in New Product Alliances: A Strength-of-Ties Perspective.” Journal of Marketing 65 (2): 1–18. doi:10.1509/jmkg.65.2.1.18253.

- Schild, R. 2016. “Environmental Citizenship: What Can Political Theory Contribute to Environmental Education Practice?” The Journal of Environmental Education 47 (1): 19–34. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1092417.

- Scott, J. 2000. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Smyth, J. C. 2006. “Environment and Education: A View of a Changing Scene.” Environmental Education Research 12 (3–4): 247–264. https://doi.10.1080/13504620600942642. doi:10.1080/13504620600942642.

- Stachowiak, S., and J. Lynn. 2018. When Collective Impact Has an Impact: A Cross-Site Study of 25 Collective Impact Initiatives. ORS Impact of Seattle, WA, and Spark Policy Institute of Denver, CO.

- Stapleton, S. R. 2020. “Toward Critical Environmental Education: A Standpoint Analysis of Race in the American Environmental Context.” Environmental Education Research 26 (2): 155–170. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1648768.

- Stedman, R. C. 2016. “Subjectivity and Social-Ecological Systems: A Rigidity Trap (and Sense of Place as a Way out).” Sustainability Science 11 (6): 891–901. doi:10.1007/s11625-016-0388-y.

- Taylor, D. E. 2000. “The Rise of the Environmental Justice Paradigm: Injustice Framing and the Social Construction of Environmental Discourses.” American Behavioral Scientist 43 (4): 508–580. doi:10.1177/0002764200043004003.

- Teig, E., J. Amulya, L. Bardwell, M. Buchenau, J. A. Marshall, and J. S. Litt. 2009. “Collective Efficacy in Denver, Colorado: Strengthening Neighborhoods and Health through Community Gardens.” Health & Place 15 (4): 1115–1122. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.06.003.

- Tindall, D. B., and J. L. Robinson. 2017. “Collective Action to Save the Ancient Temperate Rainforest: Social Networks and Environmental Activism in Clayoquot Sound.” Ecology and Society 22 (1): 40. doi:10.5751/ES-09042-220140.

- U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland Combined Statistical Area. www2.census.gov/geo/maps/econ/ec2012/csa/EC2012_330M200US488M.pdf.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 1978. Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education, Tbilisi, USSR, 14–26 October 1977: Final Report. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000032763.

- Uzzi, B. 1997. “Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness.” Administrative Science Quarterly 42 (1): 35–67. doi:10.2307/2393808.

- Uzzi, B., and R. Lancaster. 2003. “Relational Embeddedness and Learning: The Case of Bank Loan Managers and Their Clients.” Management Science 49 (4): 383–399. doi:10.1287/mnsc.49.4.383.14427.

- Valente, T. W., L. A. Palinkas, S. Czaja, K. H. Chu, and C. H. Brown. 2015. “Social Network Analysis for Program Implementation.” Plos One 10 (6): e0131712. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131712.

- Vance-Borland, K., and J. Holley. 2011. “Conservation Stakeholder Network Mapping, Analysis, and Weaving.” Conservation Letters 4 (4): 278–288. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00176.x.

- Wasserman, S., and K. Faust. 1994. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wellman, B., and S. D. Berkowitz. 1988. Social Structures: A Network Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wojcik, D. J. 2011. “Communication, Social Networks, and Perceptions of Water and Wildlife in the Okavango Delta, Botswana.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Florida. http://etd.fcla.edu/UF/UFE0043715/WOJCIK_D.pdf.

- Wolff, T. 2016. “Ten Places Where Collective Impact Gets It Wrong.” Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice 7 (1): 1–11. http://www.gjcpp.org.

- Wolff, T., M. Minkler, S. M. Wolfe, B. Berkowitz, L. Bowen, F. D. Butterfoss, B. D. Christens, V. T. Francisco, A. T. Himmelman, and K. S. Lee. 2017. Collaborating for Equity and Justice: Moving beyond Collective Impact. Nonprofit Quarterly. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/collaborating-equity-justice-moving-beyond-collective-impact.

- Yang, Z., R. Algesheimer, and C. A. Tessone. 2016. “Comparative Analysis of Community Detection Algorithms on Artificial Networks.” Scientific Reports 6: 30750. doi:10.1038/srep30750.

- Yang, J., and J. Leskovec. 2014. “Overlapping Communities Explain Core–Periphery Organization of Networks.” Proceedings of the IEEE 102 (12): 1892–1902. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2014.2364018.