Abstract

It is widely recognized that education plays a key role in addressing current global challenges. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) combines local actions with global thinking. In Virtual School Garden Exchanges (VSGEs) primary and secondary students from the Global South and North interact and communicate digitally about their school gardens. This study focuses on educators’ expectations regarding learning outcomes of VSGEs and possible parallels with ESD and Virtual Exchanges (VEs) in general. A qualitative content analysis of 23 semi-structured interviews with educators engaged in 18 VSGEs was conducted. Even though the VSGEs took different individual approaches, the analysis revealed many commonalities in the respondents’ intentions: amongst other things, educators were aiming to promote knowledge about gardening and food, horticultural and cooperation competencies, and values such as solidarity. Nevertheless, some educators feared that VSGEs might also have some negative effects. The results show parallels with the aims of ESD and VEs.

Introduction

The United Nations (UN) Agenda 2030, adopted in 2015 (UN 2015), aims to fight global challenges (e.g. global poverty and climate change) and redirect the world along a more sustainable path. At the core of Agenda 2030 are 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that address major developmental challenges for humanity. The aim of the SDGs is to secure a sustainable, peaceful, prosperous, and equitable life on earth for everyone, both now and in the future (UNESCO 2017). Agenda 2030 further notes that this will require comprehensive political, economic, and social transformation and that education, particularly Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), must play a key role in this effort (see SDG 4.7) (UN 2015).

In this study, ESD is defined as a holistic, problem-solving, future-, and action-oriented approach that addresses social, ecological, and economic aspects and local and global perspectives on various sustainability issues (Rieckmann 2012, 2018a; Scheunpflug and Asbrand 2006; Schreiber and Siege 2016). ESD responds to global challenges that demand new ways of teaching and learning and makes a significant contribution to the transformation of society (Barth and Rieckmann 2009; Scheunpflug and Asbrand 2006). Partnerships also play an important role in the achievement of the SDGs (see SDG 17). In the ESD context, it is recognized that global partnerships between learners provide enriching learning opportunities (Rieckmann 2018a; Schreiber and Siege 2016). They ‘enable students to learn about real-world challenges and [learn] from the partners’ expertise and experiences. (…) (and) can provide an environment to initiate global dialogues and foster mutual respect and understanding’ (Rieckmann 2018a, 50).

One virtual global school partnership based on the international and sustainable activity of school gardening is Virtual School Garden Exchange (VSGE), which is the focus of the present study. In VSGEs, elementary and secondary school students from around the world engage in exchanges about their school garden experiences and related topics via emails, photos, films, or videoconferences (Lochner 2016). They are a special form of Virtual Exchange (VE), which is defined by Evolve (Citation2018, para.1) as:

A practice (…) that consists of sustained, technology-enabled, people-to-people education programmes or activities in which constructive communication and interaction takes place between individuals or groups who are geographically separated and/or from different cultural backgrounds, with the support of educators or facilitators.

While VEs are a well-established field of research and practice, VSGEs are a more recent development. A systematic literature review by Lochner, Rieckmann, and Robischon (Citation2019) identifies a research gap with regard to VSGEs in the academic literature on school gardening since 1992,Footnote 1 with only one of 158 articles referring directly to VSGEs. In this article, Bowker and Tearle (Citation2007) analyzed views of school gardens among students in three countries who then engaged with each other in a subsequent stage of the project. The authors assumed that after participating in a VSGE, the learners might gain new perspectives on gardening, see their garden in a more complex and global context, and learn practical gardening skills from their peers (Bowker and Tearle Citation2007, 98).

Although at least 18 different VSGEs have been conducted worldwide over the last two decades, or are currently being conducted, research on VSGEs is scarce. These 18 VSGEs constitute the sample considered in this study. VSGEs are a very heterogeneous field, and to date, no network, standardized practices and terms, guidelines or pre-defined learning goals have been established. All of the 18 VSGEs have their own individual approaches and were developed independently. Given that VSGEs are typically extracurricular, their design and implementation are strongly dependent on the participating educators and their intentions and motivation. This study aims to identify common ground between the VSGEs in question.

Due to the lack of literature on VSGEs, the present paper takes two related areas of research – ESD and VEs – as the basis for its approach to this new field of research and focuses on possible parallels with ESD and VEs learning outcomes and learning settings. It is therefore guided by the following research questions:

(1a) What learning outcomes do VSGE educators intend their learners to achieve?

(1b) Do these learning outcomes overlap with the learning outcomes presented in the literature on ESD and VE?

(2a) Which learning settings do VSGE educators choose?

(2b) Do these learning settings overlap with the learning settings described in the literature on ESD and VE?

To explore these research questions, data on the intended learning outcomes and learning settings were collected from 27 educators engaged in 18 VSGEs around the world and compared with ESD and VE learning outcomes and settings. The semi-structured interviews were subjected to abductive analysis in line with Mayring’s (Citation2000) qualitative content analysis model.

The following section describes the context and theoretical foundations of this paper, and goes on to explain the methodology and research design. The empirical results of the interviews are then described and discussed, and the article concludes by highlighting the main patterns in the intended learning outcomes and settings, their connections to ESD, and by pointing toward some outstanding questions that would merit further research.

Context and theoretical foundation

Literature on ESD and VEs informed the theoretical exploration of the relationship between the intended learning outcomes and learning settings for VSGEs and ESD and for VSGEs and VEs.

To provide readers with an ‘advance organizer’, the coding system used in the analysis of the interviews also forms the basis of the following section and is indicated in bold. As is typical with iterative qualitative research processes, the coding system was developed through continuous dialogue between empirical findings and theoretical concepts. The codes that emerged in this study were learning outcomes such as knowledge, competencies, and values, learning settings, differences and similarities as learning opportunities, and risks to learning in VSGEs.

Education for Sustainable Development – learning outcomes and learning settings

ESD is expected to provide learners with the knowledge, competencies, and values needed to contribute to sustainable development (UN Citation2015; UNESCO Citation2017). ESD programs typically deal with certain key areas of knowledge, such as cultural diversity, sustainable production and consumption, climate change, and globalization (Rieckmann Citation2018b; Schreiber and Siege Citation2016). These exhibit many parallels with the SDGs, which can also be seen as a list of topics for ESD (UNESCO Citation2017).

Diverse approaches have been taken to defining the competencies targeted in ESD (e.g. Brundiers et al. Citation2021; De Haan Citation2006, Citation2010; Glasser and Hirsh Citation2016; Rieckmann Citation2012; Wiek, Withycombe, and Redman Citation2011). Shephard, Rieckmann, and Barth (Citation2019) point out that ESD and related terminologies such as competencies stem from different parts of the world and from different languages. They are therefore sometimes confusing and can lead to misunderstandings.

This study uses UNESCO’s concept of eight key sustainability competencies: anticipatory, normative, strategic, critical thinking, self-awareness, integrated problem-solving, systems thinking and collaboration competencies (UNESCO Citation2017). Apart from these, basic competencies such as linguistic competency also make an essential contribution to sustainable development (Rieckmann Citation2018a).

The development of values is considered central to ESD, as values help to address global and local challenges today and in the future (UNESCO Citation2014). The concept of transformative learning addresses the question of how a change in learners’ values can take place within the framework of ESD (Balsiger et al. Citation2017; Sterling Citation2011). However, very few documents list specific values to be promoted; they are often linked to competencies such as empathy and collaboration. Nevertheless, a UNESCO position paper on ESD (2019) addresses the necessity of ‘values which could provide an alternative to consumer societies, such as sufficiency, fairness and solidarity’ (UNESCO Citation2019, 5). Similarly, Scheunpflug and Asbrand (Citation2006) highlight that ‘solidarity, tolerance, empathy, (and) a holistic world view’ are central to ESD approaches based on action theory (Scheunpflug and Asbrand Citation2006, 35).

The ESD literature also emphasizes particular learning settings, such as ‘interactive, learner-centred, participatory and action-oriented learning settings’ oriented toward a sustainable future (UNESCO Citation2017, 7). Likewise, learning in a complex setting that links the local with the global is part of ESD (Rieckmann Citation2018a; Scheunpflug and Asbrand Citation2006). Global school partnerships are one form of learning settings for ESD. VSGEs are an example of global school partnerships and provide an opportunity to embed the global perspective of ESD within school gardens (Lochner, Rieckmann, and Robischon Citation2019; Wolsey and Lapp Citation2014). Barth and Rieckmann (Citation2009) claim that ‘settings in which learners can deal with global sustainability topics and can communicate and collaborate with people from other countries’ (Barth and Rieckmann Citation2009, 27) are essential elements of ESD. However, learning about global issues and in global contexts is also challenging and risky (Andreotti and de Souza Citation2008; Hicks and Bord Citation2001): ‘Most educators only make things worse’ (Hicks and Bord Citation2001, 314), as they are often not prepared to facilitate such processes. Andreotti and de Souza (Citation2008) point out the danger of ‘uncritical reinforcement of notions of supremacy and universality of ‘our’ (Western) ways of seeing and knowing, which can undervalue other knowledge systems and reinforce unequal relations of dialog and power’ (Andreotti and de Souza Citation2008, 23).

In summary, the literature demonstrates that on the one hand ESD aims to foster knowledge, competencies, and values that align with sustainable development and to create appropriate learning settings. On the other, ESD is complex and challenging and therefore brings with it a number of risks; learning might develop in the opposite direction from that which was intended (Jickling and Sterling Citation2017).

Virtual Exchanges – learning outcomes and learning settings

The literature on VEs provides relevant insights for VSGE learning outcomes and settings.

VE (…) is seen as a reflective, experiential approach to education, which aims to encourage participants to engage with difference, to assess and interrogate information and perspectives, and to explore and negotiate identities, their own as well as those of others, through online, intercultural interactions with distant peers. (Helm Citation2018, 6)

Research on VEs primarily focuses on VEs in higher education and language learning (Peiser Citation2015; Turula, Kurek, and Lewis Citation2019). It is seldom linked to ESD or sustainable development (Abrahamse et al. Citation2015; Barth and Rieckmann Citation2009). VEs are conducted with a wide range of age groups. However, there are few studies on VEs in primary and secondary schools that identify additional objectives for such encounters (see Krutka and Carano Citation2016; McCormick et al. Citation2005; Peiser Citation2015).

Interactions between students in VEs provide opportunities to gain knowledge about schooling, extracurricular activities, and traditions (e.g. school uniforms) in other countries (Peiser Citation2015). Through VEs, students can learn about other countries’ culture, geography, and history (Krutka and Carano Citation2016; Peiser Citation2015). In addition, their environmental knowledge can be expanded (Krutka and Carano Citation2016; McCormick et al. Citation2005).

VEs primarily aim to develop linguistic competencies (Krutka and Carano Citation2016; McCormick et al. Citation2005; Peiser Citation2015), but they can also foster problem-solving and collaboration competencies (Krutka and Carano Citation2016). The use of digital media enables learners to practice their digital competencies (Krutka and Carano Citation2016; McCormick et al. Citation2005). They can also train their critical thinking skills, ‘dispel stereotypical images of partners’ (Peiser Citation2015, 372), or even lead learners to experience a ‘positive and drastic shift in their perceptions of their international peers’ (Krutka and Carano Citation2016, 121f.).

Participation in VEs offers learners the opportunity to develop values such as empathy, respect, openness, solidarity, and interest (Krutka and Carano Citation2016; McCormick et al. Citation2005; Peiser Citation2015). To achieve these learning outcomes, VEs must be embedded in a learner-focused, sustained, and authentic learning setting (McCormick et al. Citation2005; Peiser Citation2015).

In VEs, differences and similarities between the participating groups of students can provide many learning opportunities (Helm Citation2018). Students can ‘learn about cultural similarities and differences in products, practices, processes (…) and to some extent, beliefs’ (Peiser Citation2015, 369). Both Peiser (Citation2015) and Krutka and Carano (Citation2016) emphasize learning about similarities. However, alongside these potential learning outcomes, both groups of authors also see certain risks associated with learning in VEs. Rather than leading to deeper understanding and solidarity, VEs might exacerbate feelings of difference, stereotypes, and cultural misunderstandings (Krutka and Carano Citation2016; Peiser Citation2015), ‘especially when contentious social, political and historical issues are discussed’ (Peiser Citation2015, 365). These potential risks are also supported by the literature on school linking (mostly virtual), school partnerships (including visits) and sponsorships between schools and learners in the Global North and Global South (see Krogull and Scheunpflug Citation2013; Leonard Citation2014; Martin Citation2005; Pickering Citation2008; Wagener Citation2018).

Education for Sustainable Development and Virtual Exchanges

ESD and VEs have different foci: ESD focuses primarily on sustainability-related learning outcomes, while VE focuses on interculturality and languages. Nevertheless, a review of the literature on the two topics reveals parallels regarding learning outcomes and learning settings. Both ESD and VEs aim to foster knowledge about globalization, geography, and cultures, and collaboration and systems thinking competencies, as well as values such as solidarity and empathy. Furthermore, both aim to create learning settings that are complex, learner-focused and future-oriented.

VSGEs are a special type of VE and their particular focus on the sustainable activity of school gardening and the integration of a global perspective point to possible parallels with ESD. However, it remains an open question whether the concepts and intended learning outcomes developed by VSGE educators are aligned with the intended learning outcomes of ESD and VEs.

Data and methods

The sample

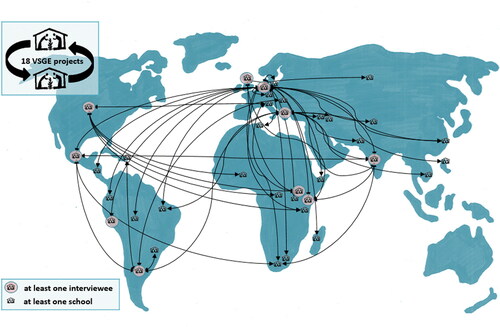

Data for this study was collected through 23 semi-structured interviews with 27 educators who are currently, or have previously been, engaged in 18 VSGEs (see and ). These exchanges were identified by applying a snowball sampling system, as described by Schnell, Hill, and Esser (Citation2013), using internet research, VE platforms, different national and international school garden newsletters, contacts arising from conferences, and the results of the systematic literature review (Lochner, Rieckmann, and Robischon Citation2019). Building upon previous studies (Lochner Citation2016, Citation2019), the sample grew over three years from eight to 18 exchanges. Sampling ended when no new VSGEs or new educators could be identified, suggesting that substantial coverage had been achieved. It is likely that more VSGEs exist but could not be identified due to the lack of common terminologyFootnote 2 (Lochner Citation2019), language limitations or other limitations mentioned in the introduction.

Figure 1. Participating countries and location of interviewees; only the exchange with the 27 countries is not fully represented (just one of the 18 European countries is shown).

Table 1. Overview of interviewees and VSGEs.

Among the 18 VSGEs, three different forms of organization could be distinguished: programs to which schools from different countries could apply (4 of 18), projects with a fixed number of schools from particular countries (7 of 18), and individual bilateral school exchanges (7 of 18). Furthermore, the exchanges differed with regard to characteristics such as target group age, exchange medium, duration and language (see ). However, all schools involved were primary or secondary schools. Most of the VSGEs were bilateral exchanges, always with one school from the Global North and one from the Global South. Five exchanges involved participation by schools from three to 27 countries; some also involved North-North or South-South exchanges (see ). The earliest VSGE project included in the sample started in 2001 and is still ongoing. However, this is an exception. Eleven of the 18 VSGEs were planned and implemented as one-or-two-year-projects (see ).

Interviewees were primarily (15 of 27) based in Europe (England, Germany, and Greece), with four based in Africa (Kenya and Uganda), five in the Americas (Argentina, Peru, Mexico, and the US), and three in Asia (India) (see ). Ten interviewees were male and 17 female. Most of them worked directly with learners, delivering VSGEs as teachers or external educators. Other interviewees worked as national or international VSGE coordinators, with responsibility for promoting and sustaining VSGEs nationally or internationally (see ).

Study procedure

Semi-structured interviews allow researchers to address the personal perspectives, backgrounds, and structures that are relevant to interviewees (Flick Citation2006; Schnell, Hill, and Esser Citation2013). In four cases, two educators were interviewed together, as they had worked very closely in the same VSGE. For six VSGEs, educators from two different countries were interviewed (separately) (see ).

All interviewees were anonymized and pseudonyms were used. Pseudonyms reflected the interviewees’ gender and location, with pseudonyms for interviewees from the Global North beginning with N and those from the Global South with S. The interviews averaged 60 min in length and were audio-recorded with the respondents’ permission. Most interviews were conducted via Skype in English, German, or Spanish.

The interview guides consisted of pre-formulated open questions (Schnell, Hill, and Esser Citation2013). The narrative process began with the primary question ‘What did/do you want to achieve with the VSGE?’ When participants’ answers did not relate to the question, supporting questions were asked to guide the interviewees, such as ‘Why did/do you want your learners to participate in the VSGE?’ or ‘What did you intend learners to learn in the VSGE?’ The interview guides were revised, proofread, and tested in all three languages.

Data analysis

The underlying data consisted of the anonymized interview transcripts. Pauses, tone of voice, and other nonverbal elements were omitted from the transcriptions (Flick Citation2006). The transcriptions and analyses were conducted using MAXQDA software and analysis in accordance with Mayring’s (Citation2000) qualitative content analysis model. In an abductive manner, a coding system was developed, revised, expanded, and modified iteratively in continuous dialogue between data and literature (Mayring Citation2000). This process identified the codes of knowledge, competencies, and values, all classified as learning outcomes, and 20 subcodes. The learning setting code had 9 subcodes. Furthermore, two cross-sectional codes, exploring differences and similarities and risks to learning, were used in the analysis (see ). During the coding process, further codes were discussed, such as codes related to the location of the interviewee (Global North and Global South) or their role with regard to charity (Charity-giver, Charity-receiver and Non-charity). Ultimately, these codes did not prove fruitful and are therefore not discussed in the results. The codes and subcodes presented each appeared in at least three different interviews, as the aim of the study was to find common patterns. To ensure the reliability and validity of the coding system, the codes were regularly discussed and validated with other researchers. Subsequently, the coded segments were paraphrased to facilitate the detection of similarities and contradictions, before being analyzed and interpreted (Mayring Citation2000).

Table 2. Coding system.

Findings

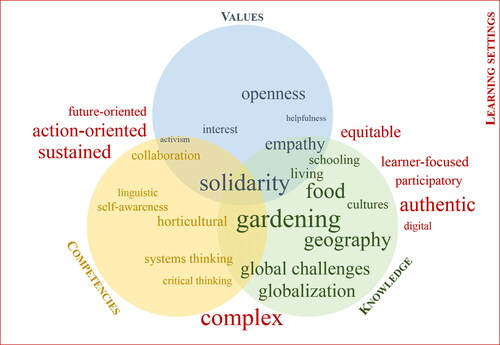

This section first provides an overview of the findings with regard to learning outcomes and learning settings. The number of interviews containing any given subcode ranged from three (e.g. activism or helpfulness) to 19 (gardening). The frequency of each code is reflected in by the font size. Codes given particular emphasis were gardening, the value of solidarity and the complex learning setting. The intention of strengthening learners’ competencies was less pronounced. Secondly, the findings regarding the two cross-sectional codes exploring differences and similarities and risks to learning will be presented.

Figure 2. Intended learning outcomes and learning settings. The font sizes of the words reflect the number of interviews referring to the codes (e.g. gardening in 19 of 23 interviews and helpfulness in 3 of 23 interviews).

Learning outcomes

Knowledge

The heart and basis of VSGEs are school gardens and the commonality of gardening. Educators thus expressed the hope that students would ‘learn that gardening is a global thing’ (Simon). Becoming aware of the universality of gardens may motivate students, lead to reflection about their own gardening, and help them see the importance of gardening activities. The diversity of crops grown in different school gardens was also mentioned as a major object of learning: ‘which crops do you grow, why do you grow them’ (Samson) and ‘where do they actually come from’ (Nanett*Footnote 3 ).

Several educators wanted their students to learn how different gardening activities, such as sowing, pest control, watering, fertilization, ridging, and cultivation, were conducted in other countries. It was also hoped that students would develop an awareness of the factors that impact on gardening, such as climate (change), soil, the availability of water, and/or gardens’ geographic location. Interviewees described school gardens as ‘window(s) on the world’ (Nellie) and as ‘vehicle(s)’ (Nick) for addressing other topics.

Local conditions in different gardens were also taken as examples of learning about global challenges, such as global agricultural systems, climate change, water as a limited resource, and sustainability. ‘(Learners) are supposed to discuss global issues that have to do with sustainability on Planet Earth’ (Nathan*). Educators also wanted their learners to experience globalization and learn about the common needs of humankind, global mobility and how societies and economies are globally connected: ‘Making the students understand the global (…) aspect of food, seeds and so on’ (Shivam/Saransh).

In order to understand these complex global topics, a basic geographical understanding is necessary. Learners therefore needed to learn to locate the partner country on the globe or get a feeling of distance by calculating the flight time: ‘The kids should understand that they are part of Europe, that Europe is part of the world, and that other continents exist and other humans live on these continents - kids who might live in a similar or maybe a different way’ (Nils/Nele*). Climate, seasons, and weather were mentioned as further intended areas of learning. The aim was for learners to gain knowledge about the partner country and be able to situate specific information about the partner school in a broader framework (cf. authentic setting).

In addition, educators wanted students to be exposed to, get to know and appreciate new cultures. The broad term ‘culture’ was further broken down by interviewees, who gave examples of different food-related traditions, such as the use of crops, recipes, and ways of life. Educators also mentioned that they were keen for students to learn about the importance of their own local cultures: ‘to know and to save our products, local products, to believe in our foods, to save the traditional food and to save our culture’ (Naira).

Food was closely linked to culture and gardening and seen as a broad learning area. Gardens were described as ideal starting points for ‘talk[ing] about what they grow and then how they cook it, what their favorite foods are’ (Nellie). Learners could exchange information about something they all had in common: ‘growing and eating’ (Nancy/Naomie). They might learn about their peers’ favorite dishes, exchange recipes, or cook a dish from their partner country.

Also very closely connected to the learners’ reality is the fact that all participants in VSGEs attend school. VSGEs could thus provide opportunities ‘to understand how education works in other places of the world’ (Saray). Students should learn how schools are structured, whether student groups are divided into different grades or all are taught in a single classroom, what classrooms look like, what kinds of equipment partner schools have, what and how kids learn, and whether they wear school uniforms. Some educators also identified an opportunity for learners to reflect on their own school through VSGEs.

Other educators pointed out that the aim was for their students to learn how people live elsewhere and ‘understand what people are doing on the other side of the world’ (Samweli). This might encompass learning about what others’ homes look like, what clothes they wear, whether children have to help at home or with agriculture, how their daily lives are structured, and in what social and economic settings they live.

Competencies

In nearly all interviews, the desire to foster knowledge of gardening was mentioned. However, educators only expressed the intention that their students should develop or gain new horticultural competencies in eight interviews. For example, learners could ‘get to know new forms of crop cultivation (…) and recreate them’ in their own gardens’ (Sebastián**Footnote 4 ). The aim was to become familiar with and adopt new pest control methods or gardening practices. Educators wanted learners ‘to copy up, to learn’ (Samweli) from their peers. Others said VSGEs should lead to ‘more collaborative interactions across cultures’ (Samson), with learners developing an understanding of others’ needs, perspectives, and actions via personal interactions, by building relations with others and by gaining sensitivity.

Educators also aimed to foster their students’ ability to recognize and understand global interconnectedness and relationships, which are part of the systems thinking competency: ‘Our lifestyle has concrete effects on other regions of the world’ (Nina*). Interviewees wanted their students to see global connections between, for example, gardens and the environment, hunger and migration, the German pharmaceutical industry and farmers in rural India, and summer in the southern and winter in the northern hemisphere.

Furthermore, educators wanted to foster learners’ critical thinking competency through VSGEs. They aimed for students to learn to reflect on their perceptions of the world and others, including prejudices and stereotypes. They also wanted students to reflect on themselves and become aware of their role in the local and/or global community. Moreover, educators saw VSGEs as opportunities for learners to practice a second language in a real-life setting, develop an interest in languages, and come into contact with new and previously unknown languages.

Values

Educators saw school gardens and plants as something unifying: ‘as a common language’ (Nick) that should foster solidarity among learners. They sought to connect learners globally, awaken in them a feeling of global citizenship as well as a sensibility for others and the common good. Learners were expected to see, understand, or know that they are ‘global citizens’ (Supriya, Nancy/Naomie, Nathan), ‘global students’ (Samson), or ‘siblings’ (Sebastián**). For the interviewees, VSGEs were also about fostering empathy, such as understanding and sharing others’ feelings and the ability to change perspectives. Furthermore, educators wanted ‘to open the minds of my children’ (Naira, Sofía). Specifically, this meant openness towards the world, new experiences, and people in foreign countries. Learners were expected to open up to new perspectives and retreat from fixed ideas. Educators also wanted to stimulate learners’ interest and curiosity. They aimed for learners to ‘have the interest, have the love for their fellow students’ (Samson), and to be curious about gardens, plants, geography, and languages.

Some interviewees hoped that participation in VSGEs would promote the value of activism among learners. They wanted to ‘encourage children to play a really active role in making the world a better place’ (Nancy/Naomie). In all cases, activism was mentioned in relation to a positive future scenario.

The value of helpfulness appeared in three interviews, solely among educators from the Global North. These educators wanted their students to help their partner school in the Global South by collecting money for their gardens or sending seeds or tools. In return, ‘a child from the Global South can help a child from the Global North with speaking or writing English’ (Nina*).

Learning settings

These diverse intended learning outcomes were often linked in the interviews with explanations of how educators designed their VSGEs to achieve the aforementioned knowledge, competencies, and values, which will be described here under learning settings.

School gardening serves as common ground and therefore provides an equitable learning setting for all learners. The activities in all school gardens were ‘pretty much the same: digging, (…) planting, (…) watering, (…) weeding and (…) harvesting, (…), so maybe it is a good vehicle for an equitable partnership’ (Nick). In the encounters, the aim was for learners to interact ‘on an equal footing’ (Nathan*). In addition, some interviewees aimed to encourage equal contributions from all partners. This reflects concerns on the part of interviewees – exclusively from the Global North – about a potential imbalance or hierarchy (see Risks to learning).

The choice of rooting exchanges in the concrete action of gardening was highlighted in nearly half of the interviews: ‘I wanted to involve (…) my pupils in tasks with [their] hands’ (Naira). Some educators sought to establish other joint initiatives with, or influenced by, the partner school, such as ‘common project days’ (Nathan*) or ‘paint(ing) your sheds or your watering cans with some symbols of your partner overseas’ (Nick).

The aim was for VSGEs to bring more complexity, new perspectives from different disciplines and especially a global perspective to the gardens: Learners were ‘communicating in a globalized space’ (Norbert*). Mostly educators from the Global North intended the global perspective to be authentic, in the sense of ‘not constructed’ (Nina) or ‘not anonymous’ (Naira). The aim was to provide a learning setting that was different from reading books or watching films about others’ realities. Moreover, the aim was to achieve sustained exchanges, based on regular communication, and for exchanges to continue even when an external organization was no longer involved. The educators intended to build relationships between teachers and schools and friendships between learners. They felt that physical exchanges involving teachers and learners could help to sustain relationships.

Students from primary through to upper secondary school age participated in the VSGEs (see ). There was therefore no uniformity among learners. However, independently of the age group educators worked with, they agreed that VSGEs needed to be adapted to ‘learners’ developmental stages’ (Natascha*), their previous experiences, language competences, and ability to cope with complexity. In addition, the communication tools needed to be appropriate to learners’ capabilities. For example, learners might feel inhibited in face-to-face situations such as videoconferences. Furthermore, it was important to provide them with topics on which it was easy to start a conversation. Several interviewees saw school gardening as a wonderful low-threshold topic because there was always something to talk about. Sufficient scope for student participation was also essential for the success of VSGEs and their learning processes. This could be influenced through the choice of communication tools and technical equipment, for example, by using ‘huge screens (during videoconferences) so that all can participate’ (Sofía**). The combination of analog and digital settings opened up new perspectives for school gardens.

Exploring differences and similarities

They may be growing different vegetables in their garden and making different recipes, but they are still growing and eating. (Nancy/Naomie)

A general result that was linked to many of the aforementioned findings was that all educators saw VSGEs as presenting an opportunity to explore differences and/or similarities between learners from different countries. Some educators highlighted similarities; for example, they wanted to show that there were more similarities than differences or wanted to focus on more than just differences. School gardens were seen as common starting points that could help people connect. Many stressed the coexistence of similarities and differences. Even though all participating learners will be involved in gardening, they will be working in different climates and/or different cultural contexts. This was seen as holding great potential for learning.

In some interviews, the intention of promoting learning about differences was motivated by the desire to encourage comparison and self-reflection. For example, interviewees from the Global North wanted students to learn about living conditions in other parts of the world, to understand: ‘how lucky we are here. (…) How different it can be in another school’ (Nils/Nele*). Sofía hoped that the VSGE might show her learners that ‘with effort they could also improve their situation’ (Sofía**).

Risks to learning

So far, the findings have covered intended positive learning outcomes. It is logical that the educators interviewed would intend their VSGEs to have positive learning outcomes. However, in half of the interviews, educators, primarily from the Global North, also expressed fears about the potential negative effects of VSGEs.

It’s the slight uncertainty or the question (…) of whether you can cause damage (with a VSGE) or if it is always something positive? (Noreen*)

Nick assumed that (post-)colonialism and ‘colonial mindset(s)’ might influence relationships between partner schools. Educators also discussed various difficulties when the Global North provides funding to the Global South, worrying that this might influence the design of the VSGE and/or the relationships between schools and learners. They were also concerned that groups might have different expectations of the VSGE. For instance, one group might want to exchange information, while the other was hoping for funding. Nathan assumed that very unequal resources might cause jealousy. Another risk identified was that VSGEs could reinforce stereotypes and emphasize differences instead of doing the opposite. Limited time to devote to the exchange, learners’ age, and/or a desire not to overwhelm them might lead to a simplified representation of the partner school and country: ‘There is a high theoretical demand, but you have to break it down to (…) the elementary level, and a lot is lost’ (Natascha*). This could lead to simplification instead of diversification, resulting in learning settings that were authentic but not complex. In addition, there was a concern that learners’ prior knowledge could impede their learning during the VSGE. Their peers might present new and contrary information, and they might not be equipped to handle these contradictions. Moreover, educators feared that learners might behave in an indiscreet manner and offend their partners. Natascha pointed out that contact with the ‘foreign’ ideally leads to openness, but could also cause anxiety instead, and learners might close themselves off.

Discussion

The data presented here indicate that although the 18 VSGEs were mostly developed independently and very differently from each other, there was an overlap between educators’ intentions concerning learning outcomes and settings. Nearly all interviewees were aiming to strengthen knowledge, competencies, and values, and to create specific learning settings through their VSGEs. The key elements were the intention of fostering knowledge about gardening and the value of solidarity (see ). In addition, nearly all of them sought to enable learning in a complex setting and use differences and similarities between groups of learners as an opportunity for learning. In contrast to the intended positive learning outcomes, some educators also feared that VSGEs could potentially have negative effects on learners.

The overlap between the findings and VE and ESD literature (see ) is a logical consequence of this study’s abductive approach, as the coding system was developed in a continuous dialog between data and literature. Nevertheless, it is particularly interesting to see where they overlap and where they do not.

Table 3. Overlap between the literature and interviews.

Comparison of the intended learning outcomes of VSGEs with those of VEs supports the notion that VSGEs are a special type of VE (see ). Nevertheless, VSGEs are unique in their focus on gardens and related competencies and themes. At first glance, the majority of subcodes relating to the knowledge, competencies, and values that educators intended to foster seem to have no direct relationship with gardening. Nevertheless, upon deeper perusal, there are many links between the subcodes and school gardening.

The findings also exhibit parallels with ESD (see ). Common to both is the intention of fostering knowledge about sustainability-related themes. Competence development, which is central to ESD, was addressed in only few interviews (see ). Interviewees mentioned their intention of fostering a total of six competencies, four of which correspond to the key sustainability competencies (Rieckmann Citation2018a; UNESCO Citation2017): collaboration, systems thinking, self-awareness, and critical thinking. Integrated problem-solving, another key sustainability competency, is addressed in the VE literature (Krutka and Carano Citation2016), although it was not mentioned in the interviews (see ). This might mean that VSGEs could also have the potential to foster integrated problem-solving.

Analyzing the interviewees’ responses regarding the four key sustainability competencies in more detail, it is striking that the educators refer to only one out of several abilities grouped into a single competency by UNESCO (Citation2017). For example, in the case of critical thinking, they describe (only) the ability to reflect on one’s own perception. There are various possible explanations for the particular emphasis placed by VSGE educators on this aspect. On the one hand, they might see this aspect as having the greatest potential, although they are aware of all aspects. On the other hand, educators might not be aware of all aspects, particularly since as Shephard, Rieckmann, and Barth (Citation2019) notes, concepts of competency in the field of ESD are diverse and can lead to misunderstandings.

Most interviews and the literature on VEs and ESD share a common view of the potential and desire to foster solidarity (Krutka and Carano 2016; McCormick et al. 2005; Peiser 2015; Scheunpflug and Asbrand 2006; UNESCO 2019). For other values, there was less alignment with the literature (see ). For example, helpfulness, as a value to be fostered, was not found in literature on ESD or VEs. Solidarity and helpfulness in fact stand in contrast to each other and have to be dealt with cautiously, as they can sometimes be confused. In the interviews, helpfulness was only mentioned by educators from the Global North, mainly with regard to donations to partners in the Global South. Research into sponsorship as an educational tool has shown that it places students in the roles of charity-giver and charity-taker, creating a problematic asymmetry (Wagener 2018). From this, parallels can be drawn with the fear of VSGE educators that they might create imbalance and hierarchy instead of an equitable learning setting. Further risks identified by educators were of a similar nature and will be discussed later.

In addition, it is also important to highlight the VSGE educators’ intention of establishing an authentic learning setting; this accords with the VE literature (McCormick et al. 2005; Peiser 2015), but did not appear in the ESD literature analyzed. One intention was for learners to establish real relations with peers from abroad. Achieving this and enabling learners to deal with the resulting complexity takes time, which was addressed by educators’ wish to create sustained learning settings. Nevertheless, most of the VSGEs analyzed did not last longer than one or two years (see ). To achieve more sustained learning, exchanges would need to be of longer duration.

This also causes risks to learning. Even though exchanges might be authentic and the information exchanged by learners might be personal and concrete, if this information is not situated in its broader context, it could lead to oversimplification. The same is true of learning about differences and similarities. All interviewees and most of the literature agree that these represent potential areas for learning (Helm 2018; Krutka and Carano 2016; Peiser 2015; Rieckmann 2018a). Gardening activities are seen as productive common ground, while differences are seen as impetuses for learning. In this regard, however, educators’ positive intentions might lead to negative outcomes. Some interviewees from the Global North wanted their learners to reflect on differences between them and their partner schools and feel gratitude for their own circumstances. Although this was meant as something positive, it could easily tip into a feeling of superiority. Rather than initiating reflection about systemic inequities, the risk is that it will result in oversimplification and lead to problematic asymmetry between groups of learners. Some risks were identified by the educators themselves and align with the negative outcomes identified by Krutka and Carano (2016) and Peiser (2015). For example, instead of dispelling stereotypes, VEs, including VSGEs, might actually strengthen them. Indeed, the literature on school linking, school partnerships and sponsorships between schools describes such encounters and interactions between learners in the Global North and Global South as controversial, encompassing a variety of potential negative outcomes (e.g. Krogull and Scheunpflug 2013; Leonard 2014; Martin 2005; Pickering 2008; Wagener 2018). As already indicated, the interviewees’ aims for their learners were well-intentioned, but in some cases there could be a risk that the actual learning outcomes might not be positive. Fostering helpfulness is just one example of problematic learning situations that might be established. This is also in line with previous findings (Andreotti and de Souza 2008; Hicks and Bord 2001; Wagener 2018). Hicks and Bord (2001) claim that learning about global issues is very complex, and different domains of learning have to be addressed to enable fruitful learning. The context of VSGEs, such as the history of school gardens in the Global North and Global South, the influence of (post-)colonialism, systemic inequities, or existing narratives and stereotypes relating to the others is complex and has not been adequately addressed by VSGE educators. If VSGE educators are not prepared for and aware of these issues, even though they might have good intentions, they might ‘make things worse’ (Hicks and Bord 2001, 314) and reinforce ‘unequal relations of dialog and power’ (Andreotti and de Souza 2008, 23).

To conclude, I want to answer the question of whether VSGEs are designed to facilitate the achievement of ESD learning objectives. There is a strong connection between learning in school gardens and sustainability. Likewise, VSGEs aim to address local and global perspectives on themes relating to school gardens and the lives of others, exhibiting congruency with ESD. The study’s results indicate that VSGE educators intend to foster ESD-related knowledge, competencies, and values among learners and aim to establish learning settings that are partially aligned with ESD. However, although the objectives of VSGE and ESD are partly congruent, VSGEs ‘only’ aim to address half of the eight key sustainability competencies. Nevertheless, good ESD practice does not always aim to address all eight key sustainability competencies to the same extent. Fostering these four competencies might be a particular strength of VSGEs. Moreover, the diversity of opinions and foci of the VSGE educators must be taken into consideration. This study was able to identify certain patterns. However, while nearly all educators agree on some key elements, such as gardening or solidarity, other codes were mentioned in only few interviews (see ).

It is clear that there are parallels between VSGE educators’ intended learning outcomes and the concept of ESD. Nevertheless, further studies on actual learning outcomes are needed to identify whether VSGEs are designed and implemented in a way that really achieves ESD learning objectives. These learning outcomes will likely be influenced by several factors. First, the participating educators and their intentions will have an impact on learning processes during VSGEs. However, the delivery of VSGEs and thus also their learning outcomes are influenced by other factors such as schools’ academic calendars, level of commitment, and the age of learners (cf. Lochner 2016).

This article represents merely a first step in exploring the new field of VSGEs. Further research is needed to achieve a better understanding. In order to build upon this study, its limitations have to be taken into account. The diversity and heterogeneity of the field proved challenging for the identification of samples, particularly given the lack of web presence, common terminology or a VSGE network. It can thus be assumed that some VSGEs were not included in this sample. In terms of the geographical distribution of interviewees, the Global North, and Germany in particular, were predominant. This was an inherent problem as the snowball sampling began in Germany. In addition, many VSGE educators proved difficult if not impossible to contact because their exchanges were no longer active and their contact information was outdated. Some of the educators interviewed worked together in a single VSGE in the same or different countries. It would have been interesting to compare the perspectives of partners from different countries. The educators who were interviewed together may have influenced each other’s responses. However, the joint interview technique might also have generated a fuller picture of the VSGEs in question.

A broader sample with more voices from the Global South might have changed some findings, as it would have included more perspectives and perhaps changed some of the foci. In addition, a larger sample would have allowed for comparisons between groups and would have enriched the study by providing more information on factors such as educators’ location (Global South or Global North), the role of charity in exchanges, the use of different digital media, students’ age groups and urban vs. rural backgrounds, etc.

Encouraging, supporting, and conducting more studies in this underexplored area of research will improve the understanding of different contexts, and the general drivers of and barriers to the implementation of VSGEs. By way of follow-up to this study, a comparative analysis of intended and actual learning outcomes would answer the question of whether VSGEs are actually able to achieve what they intend. Furthermore, comparing VSGEs with VEs with other sustainability foci would provide additional insights into the role of school gardens in VSGEs. Another future area of research arising from this study would be the roles, perspectives and personal learning processes of the educators themselves.

Conclusion

VSGE is a recent and largely unexplored field of research and practice with many unanswered questions. This study seeks to start filling this research gap by focusing on intended learning outcomes and learning settings among educators implementing VSGEs worldwide and locating them in the broader field of ESD and VEs.

A qualitative content analysis of 23 semi-structured interviews with educators involved in 18 different VSGEs yielded several clusters of common intentions. For example, educators hoped that by participating in a VSGE, their learners would gain knowledge about gardening and food, horticultural and collaboration competencies, and values such as solidarity. Furthermore, educators intended to create learning settings that reflected global complexity and enabled learners to explore differences and similarities with their peers. Some educators expressed the fear that these intended learning outcomes might not be so easy and linear to achieve, but rather a complex process. For example, rather than creating the intended feeling of global citizenship, the process might reinforce stereotypes. It thus remains unclear what participating learners actually learn and take away from VSGEs. However, it is remarkable that so many educators, primarily working independently of one another, exhibited so much agreement about their aims.

The intended learning outcomes of VSGE also correspond to a high degree with those of ESD. Nevertheless, further studies on actual learning outcomes are needed to identify whether VSGEs do in practice contribute to ESD learning objectives. As a special type of VE, VSGEs have many parallels with other VEs with regard to their intended learning outcomes and learning settings. However, VSGEs are unique in their focus on gardens and related competencies and themes.

Building upon this study, future research may wish to focus on the actual learning outcomes of VSGEs and to explore the different contexts for, general drivers of and barriers to the implementation of VSGEs. Possible questions to address might include: What learning outcomes do students achieve? Do these learning outcomes match educators’ intentions? What influence does the focus on gardening have on learning, and would a VE based on another subject yield different results? And last but not least: How can VSGEs be structurally anchored so as to enable them to be extended beyond 1–2 year projects?

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewers and my two supervisors Prof. Marcel Robischon and Prof. Marco Rieckmann for their support and constructive feedback; the interviewees for sharing with me their experiences as well as for their time and openness; Nora Lege, Christine Körner and Katharina Niedling for their inspiring perspectives on my data and Isabell Köhler for her help with the transcriptions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Funding

This work was supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Educational Research at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Johanna Lochner

Johanna Lochner is PhD student at the Albrecht Daniel Thaer-Institute of Agricultural and Horticultural Sciences at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her research interests focus on the integration of the global perspective of Education for Sustainable Development into gardening.

Notes

1 In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) was held in Rio de Janeiro. This conference marked the beginning of the official promotion of ESD.

2 School garden partnership, global garden exchange program, school garden linking, and VSGE are all terms used in the field.

3 * translated from German.

4 ** translated from Spanish.

References

- Abrahamse, A. , M. Johnson , N. Levinson , L. Medsker , J. M. Pearce , C. Quiroga , and R. Scipione . 2015. “A Virtual Educational Exchange: A North–South Virtually Shared Class on Sustainable Development.” Journal of Studies in International Education 19 (2): 140–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315314540474.

- Andreotti, V. , and L. M. T. M. de Souza . 2008. “Translating Theory into Practice and Walking Minefields: Lessons from the Project ‘Through Other Eyes’.” International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning 1 (1): 23–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.18546/IJDEGL.01.1.03.

- Balsiger, J. , R. Förster , C. Mader , U. Nagel , H. Sironi , S. Wilhelm , and A. B. Zimmermann . 2017. “Transformative Learning and Education for Sustainable Development.” GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 26 (4): 357–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.26.4.15.

- Barth, M. , and M. Rieckmann . 2009. “Experiencing the Global Dimension of Sustainability: Student Dialogue in a European-Latin American Virtual Seminar.” International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning 1 (3): 23–38.

- Bowker, R. , and P. Tearle . 2007. “Gardening as a Learning Environment: A Study of Children’s Perceptions and Understanding of School Gardens as Part of an International Project.” Learning Environments Research 10 (2): 83–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-007-9025-0.

- Brundiers, K. , M. Barth , G. Cebrián , M. Cohen , L. Diaz , S. Doucette-Remington , W. Dripps , et al. 2021. “Key Competencies in Sustainability in Higher Education – Toward an Agreed-upon Reference Framework.” Sustainability Science 16 (1): 13–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00838-2.

- De Haan, G. 2006. “The BLK ‘21’ Programme in Germany: A ‘Gestaltungskompetenz’‐Based Model for Education for Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 12 (1): 19–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620500526362.

- De Haan, G. 2010. “The Development of ESD-Related Competencies in Supportive Institutional Frameworks.” International Review of Education 56 (2-3): 315–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9157-9.

- Evolve. 2018. “What Is Virtual Exchange?” https://evolve-erasmus.eu/about-evolve/what-is-virtual-exchange/

- Flick, U. 2006. An Introduction to Qualitative Research . 3rd ed. London: SAGE. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0658/2005927681-d.html

- Glasser, H. , and J. Hirsh . 2016. “Toward the Development of Robust Learning for Sustainability Core Competencies.” Sustainability: The Journal of Record 9 (3): 121–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/SUS.2016.29054.hg.

- Helm, F. 2018. Emerging Identities in Virtual Exchange . Voillans: Research-publishing.net.

- Hicks, D. , and A. Bord . 2001. “Learning about Global Issues: Why Most Educators Only Make Things Worse.” Environmental Education Research 7 (4): 413–425. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620120081287.

- Jickling, B. , and Sterling, S. , eds. 2017. Post-Sustainability and Environmental Education . Springer International Publishing, Cham.

- Krogull, S. , and A. Scheunpflug . 2013. “Citizenship-Education Durch Internationale Begegnungen im Nord-Süd-Kontext?: Empirische Befunde aus einem DFG-Projekt zu Begegnungsreisen in Deutschland, Ruanda und Bolivien.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation 33 (3): 231–248.

- Krutka, D. G. , and K. T. Carano . 2016. “Videoconferencing for Global Citizenship Education: Wise Practices for Social Studies Educators.” Journal of Social Studies Education Research 7 (2): 109–136.

- Leonard, A. E. 2014. School Linking: Southern Perspectives on the South/North Educational Linking Process: From Ghana, Uganda and Tanzania. PhD, University of London, London.

- Lochner, J. 2016. “Globales Lernen in Lokalen Schulgärten Durch Virtuellen Schulgartenaustausch: Erfahrungen. Herausforderungen und Lösungsansätze.” (Master of Public Policy). Frankfurt Oder: Europa-Universität Viadrina.

- Lochner, J. 2019. “Virtual School Garden Exchange – Thinking Globally, Gardening Locally.” In Telecollaboration and Virtual Exchange across Disciplines: In Service of Social Inclusion and Global Citizenship , edited by A. Turula , M. Kurek , and T. Lewis , 41–47. Voillans: Research-publishing.net.

- Lochner, J. , M. Rieckmann , and M. Robischon . 2019. “Any Sign of Virtual School Garden Exchanges? Education for Sustainable Development in School Gardens since 1992.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 13 (2): 168–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408219872070.

- Martin, F. 2005. “School Linking: A Controversial Issue (Conference presentation).” WST Global Teacher Conference, London. https://www.academia.edu/1095449/North-South_School_Linking_as_a_controversial_issue

- Mayring, P. 2000. “Qualitative Content Analysis.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 1 (2): Art. 20; 28 paragraphs.

- McCormick, K. , E. Mühlhäuser , B. Nordén , L. Hansson , C. Foung , P. Arnfalk , M. Karlsson , and D. Pigretti . 2005. “Education for Sustainable Development and the Young Masters Program.” Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (10-11): 1107–1112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.12.007.

- Peiser, G. 2015. “Overcoming Barriers: Engaging Younger Students in an Online Intercultural Exchange.” Intercultural Education 26 (5): 361–376. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2015.1091238.

- Pickering, S. 2008. “What Do Children Really Learn? A Discussion to Investigate the Effect That School Partnerships Have on Children’s Understanding, Sense of Values and Perceptions of a Distant Place.” Geography Education: Research and Practice 2 (1): 1–10. https://www.geography.org.uk/write/mediauploads/research%20library/ga_geogedvol2i1a3.pdf

- Rieckmann, M. 2012. “Future-Oriented Higher Education: Which Key Competencies Should Be Fostered through University Teaching and Learning?” Futures 44 (2): 127–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2011.09.005.

- Rieckmann, M. 2018a. “Chapter 2 – Learning to Transform the World: Key Competencies in ESD.” In Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development , edited by A. Leicht , J. Heiss , and W. J. Byun , 39–59. Paris: UNESCO.

- Rieckmann, M. 2018b. “Chapter 3 – Key Themes in Education for Sustainable Development.” In Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development , edited by A. Leicht , J. Heiss , and W. J. Byun , 61–84. Paris: UNESCO.

- Scheunpflug, A. , and B. Asbrand . 2006. “Global Education and Education for Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 12 (1): 33–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620500526446.

- Schnell, R. , P. B. Hill , and E. Esser . 2013. Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung . 10th ed. München: Oldenbourg.

- Schreiber, J.‑R. , and Siege, H. , eds. 2016. “Curriculum Framework: Education for Sustainable Development.” On behalf of: Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK), German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), Engagement Global gGmbH (2nd updated and extended edition). Berlin/Bonn: Cornelsen.

- Shephard, K. , M. Rieckmann , and M. Barth . 2019. “Seeking Sustainability Competence and Capability in the ESD and HESD Literature: An International Philosophical Hermeneutic Analysis.” Environmental Education Research 25 (4): 532–547. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1490947.

- Sterling, S. 2011. “Transformative Learning and Sustainability: Sketching the Conceptual Ground.” Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 5: 17–33.

- Turula, A. , M. Kurek , and T. Lewis , eds. 2019. Telecollaboration and Virtual Exchange across Disciplines: In Service of Social Inclusion and Global Citizenship . Voillans: Research-publishing.net.

- UN (United Nations) . 2015. “Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” https://www.un.org/Depts/german/gv-70/band1/ar70001.pdf

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), ed . 2014. Aichi-Nagoya Declaration on Education for Sustainable Development.

- UNESCO . 2017. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. Paris: UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002474/247444e.pdf

- UNESCO . 2019. SDG 4 – Education 2030. Education for Sustainable Development beyond 2019 . Paris: UNESCO.

- Wagener, M. 2018. Globale Sozialität als Lernherausforderung: Eine rekonstruktive Studie zu Orientierungen von Jugendlichen in Kinderpatenschaften . Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Wiek, A. , L. Withycombe , and C. L. Redman . 2011. “Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development.” Sustainability Science 6 (2): 203–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6.

- Wolsey, T. D. , and D. Lapp . 2014. “School Gardens: Situating Students within a Global Context.” Journal of Education 194 (3): 53–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741419400306.